- 1Center for Brain and Mental Well-Being, Department of Psychology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Neurology, Tongji Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 3Peng Cheng Laboratory, Shenzhen, China

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), a non-invasive brain stimulation technique, has been considered as a potentially effective treatment for the cognitive impairment in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). However, the effectiveness of this therapy is still under debate due to the variety of rTMS parameters and individual differences including distinctive stages of AD in the previous studies. The current meta-analysis is aiming to assess the cognitive enhancement of rTMS treatment on patients of MCI and early AD. Three datasets (PubMed, Web of Science and CKNI) were searched with relative terms and finally twelve studies with 438 participants (231 in the rTMS group and 207 in the control group) in thirteen randomized, double-blind and controlled trials were included. Random effects analysis revealed that rTMS stimulation significantly introduced cognitive benefits in patients of MCI and early AD compared with the control group (mean effect size, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.76 - 1.57). Most settings of rTMS parameters (frequency, session number, stimulation site number) significantly enhanced global cognitive function, and the results revealed that protocols with 10 Hz repetition frequency and DLPFC as the stimulation site for 20 sessions can already be able to produce cognitive improvement. The cognitive enhancement of rTMS could last for one month after the end of treatment and patients with MCI were likely to benefit more from the rTMS stimulation. Our meta-analysis added important evidence to the cognitive enhancement of rTMS in patients with MCI and early AD and discussed potential underlying mechanisms about the effect induced by rTMS.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurogenerative disorders, and is typically characterized by decline in cognition, behavior and activities of daily living. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a prodromal stage of dementia, characterized by subjective cognitive deficits and objective memory impairment without impairment in daily activity (Petersen et al., 1999; Breton et al., 2019). The detrimental impact of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment on cognitive function in older adults has caused suffering of patients and burden on society. However, by now, clinical trials fail to develop drugs that would slow the dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, the exploration of effective nonpharmacological intervention is critical to extend the current treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Recently, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has received increasing attention for its prominence effect on the intervention for cognitive function in AD and MCI (Birba et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2019; Chou et al., 2020). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is a non-invasive method of brain stimulation in which a train of magnetic pulses is delivered to a specific target location of the brain. rTMS could facilitate neural coactivation and change the synaptic strength, and thus, rTMS is able to modulate the activity in cortical areas or connectivity in related networks and influence the synaptic neuronal activities including long-term potentiation, which is related to the learning and memory processes (Tegenthoff et al., 2005; Luber and Lisanby, 2014). rTMS involves trains of TMS pulse with various frequencies and intensities. It has been reported that high frequencies (higher than 5 Hz) would increase cortical excitability and low frequencies (lower than 1 Hz) would suppress cortical excitability (Maeda et al., 2000).

A series of literature has suggested the positive effects of rTMS on AD patients and with the growing body of the rTMS studies in MCI and AD recently, several meta-analyses have investigated the effects of rTMS in older adults with MCI or AD and demonstrated a beneficial effect of rTMS on the cognitive function of patients (Lin et al., 2019; Chou et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). However, most of them included patients within different stages of AD and resulted in large variety of pretreatment cognitive capability (Lin et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Few studies have focused on the patients with MCI (Jiang et al., 2021). Previous studies have declared that the synaptic plasticity and cortical excitability, which play important roles in the rTMS-underlying mechanism, might be impaired in the early course of AD, even in MCI (Nardone et al., 2014; Koch et al., 2020). Given this, putting subjects with different stage of AD together may result in imprecise evaluation of the cognitive benefit of rTMS in specific stage of AD, especially in the early AD and MCI. Ruthurford et al. has reported the more marked cognitive benefits in early AD after rTMS stimulation and emphasized the importance of applying rTMS on early stage of AD (Rutherford et al., 2015). Thus, studying the effect of rTMS on the critical transitional stage, the MCI and early stage of AD, would extend our understanding in how to prevent the progression to dementia. Meanwhile, the condition of patients before receiving the rTMS has been reported to contribute to the variability of the rTMS-induced cognitive improvement (Anderkova et al., 2015) but such effect was barely investigated by previous meta-analyses. Besides, Some of the meta-analyses included studies without a randomized, controlled design, which cannot provide strong confidence about effect the of rTMS on the cognitive function in patients (Lin et al., 2019). Furthermore, some analyses included studies with less than 5 rTMS sessions, which could not provide enough stimulation for a complete rTMS protocol which can be applied for therapy (Chou et al., 2020). Previous rTMS studies mainly utilized high-frequency stimulation in AD patients to induce cortical excitability, and the most common frequency is 10 Hz and 20 Hz. DLPFC has been used as the typical stimulation site, and some studies applied rTMS over DLPFC only while some studies combined DLPFC with multiple sites over parietal and temporal cortex. The treatment duration was also distinctive in different studies, and most clinical trials utilized 20 to 48 sessions with 5 sessions per week. The therapeutic schedule and parameter design, such as target site and treatment course, and also the post-treatment effect of the intervention still require further investigation to develop more efficient intervention protocol. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to provide up-to-date evidence on the effects of rTMS treatment on cognitive function in patients with MCI and early stage of AD based on a series of randomized, double-blind and controlled studies.

Method

Search Strategies

Databases of peer-reviewed literature were systematically searched on PubMed, Web of Science and CNKI for manuscripts about studies of the effect of rTMS on MCI or early AD, published online before March, 29, 2021. The English keywords used for the database searches were “mild cognitive impairment”, “MCI”, “Alzheimer’s Disease”, “AD”, “transcranial magnetic stimulation”, “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation”, “TMS”, “rTMS”. The Chinese keywords were “Qingdurenzhisunhai” (轻度认知损害), “Qingdurenzhizhangai” (轻度认知障碍), “Aerzihaimozheng” (阿尔兹海默症), “Aerzihaimobing” (阿尔兹海默病), “Qingdurenzhigongnengzhangai” (轻度认知功能障碍), “Chongfujingluciciji” (重复经颅磁刺激), “Jingluciciji” (经颅磁刺激). The reference lists of identified articles were checked for other potential studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for the primary relevant published studies were: (1) human search; (2) randomized controlled studies investigating the effects of rTMS treatment of the cognitive function of patients with MCI or early AD (mean score of ADAS-Cog < 25 or of MMSE/MoCA > 19); cognitive impairment was caused by AD; (3) rTMS was used as the sole treatment measure or in combination with other treatments, and compared with sham-rTMS, pharmacological treatments or cognitive training; (4) continuously stimulate for at least 20 sessions; (5) sufficient original data was provided. The exclusion criteria were: (1) cognitive impairment caused by other disease; (2) duplicate publications; (3) articles published in non-English and non-Chinese languages; (4) articles published in the form of case report, comment, letter, review, abstract or patent.

Data Extraction

Two researchers (YX, LN, and WZ) participated in extracting data from each included study, comparing their results and discussing to reach a consensus if there were disagreements. Extracted data included basic study information (author, year, and study design), sample size, sample characteristics (age, gender, education, disease type, disease duration), rTMS protocol (number of sessions, frequency, stimulation site), statistical data of the score of cognitive performance, the timing of outcome measurements, dropout rate and adverse effects. Authors of the original article were contacted if the information was unclear or insufficient.

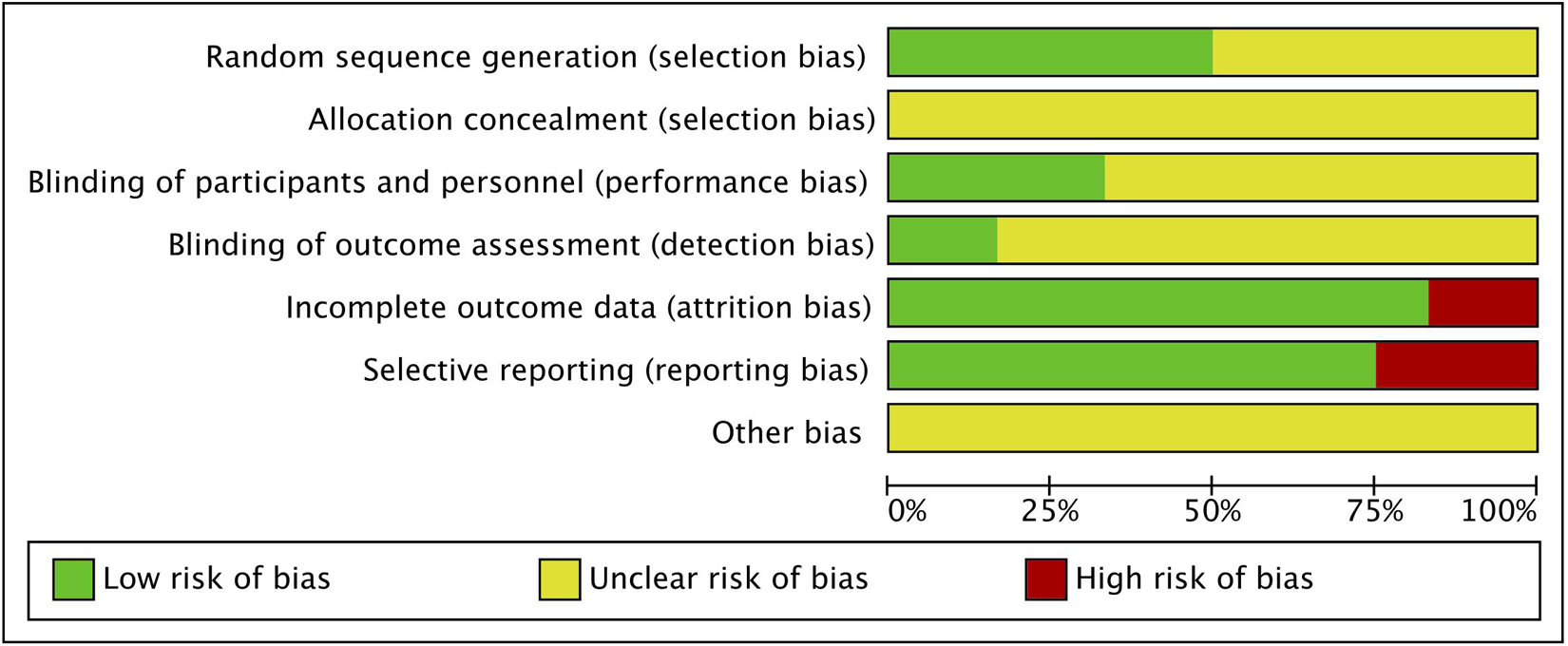

Evaluation of Risk of Bias

The risk of bias was assessed using the method recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration in Rev-man. The following characteristics were evaluated: (a) adequacy of sequence generation; (b) allocation concealment; (c) use of blinding; (d) how incomplete outcome data (dropouts) were addressed; (e) evidence of selective outcome data reporting; and (f) other potential risks that may harm the validity of the study. The risk of bias for each domain was graded as low, high, or unclear.

Data Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted with meta package in R (Balduzzi et al., 2019). We used standardized mean difference (SMD, also known as Hedges’ g given the small sample of the included studies) to express the effect size of rTMS on cognitive functions. The effect size and 95% confident interval (CI) were calculated according to the differences between poststimulation evaluations or changes relative to the baseline. With the studies which provided the outcome of pre- and post-stimulation and also the p-value or t-value of the paired sample t-test for each group, we calculated the change relative to the baseline for the group with the formulas below:

Mchange is the change score and SDchange is the standard deviation of change score. t is the t-value of paired sample t-test, and n is the sample size of the group.

The heterogeneity across effect sizes was assessed with Q-statistics and the I2 index, which is useful for assessing consistency between studies. When heterogeneity was found by Q-statistics or when I2 > 50%, a random effects model was applied. If not, a fixed effects model was used. If the effect size were reported from different subgroups of patients with different severity of AD within a single study, the data were included as independent units in the meta-analysis.

To address the possibility of publication bias, Egger’s test was conducted and a p-value < 0.05 indicated a publication bias. Due to the heterogeneity of cognitive measures included in each study, sensitivity analysis was also conducted to test whether our results would have differed if we omitted the included studies one by one. Subgroup analyses were performed separately according to cognitive domains, stimulus site, stimulus frequency, treatment course, disease duration and time points.

Results

Search and Selection of Studies

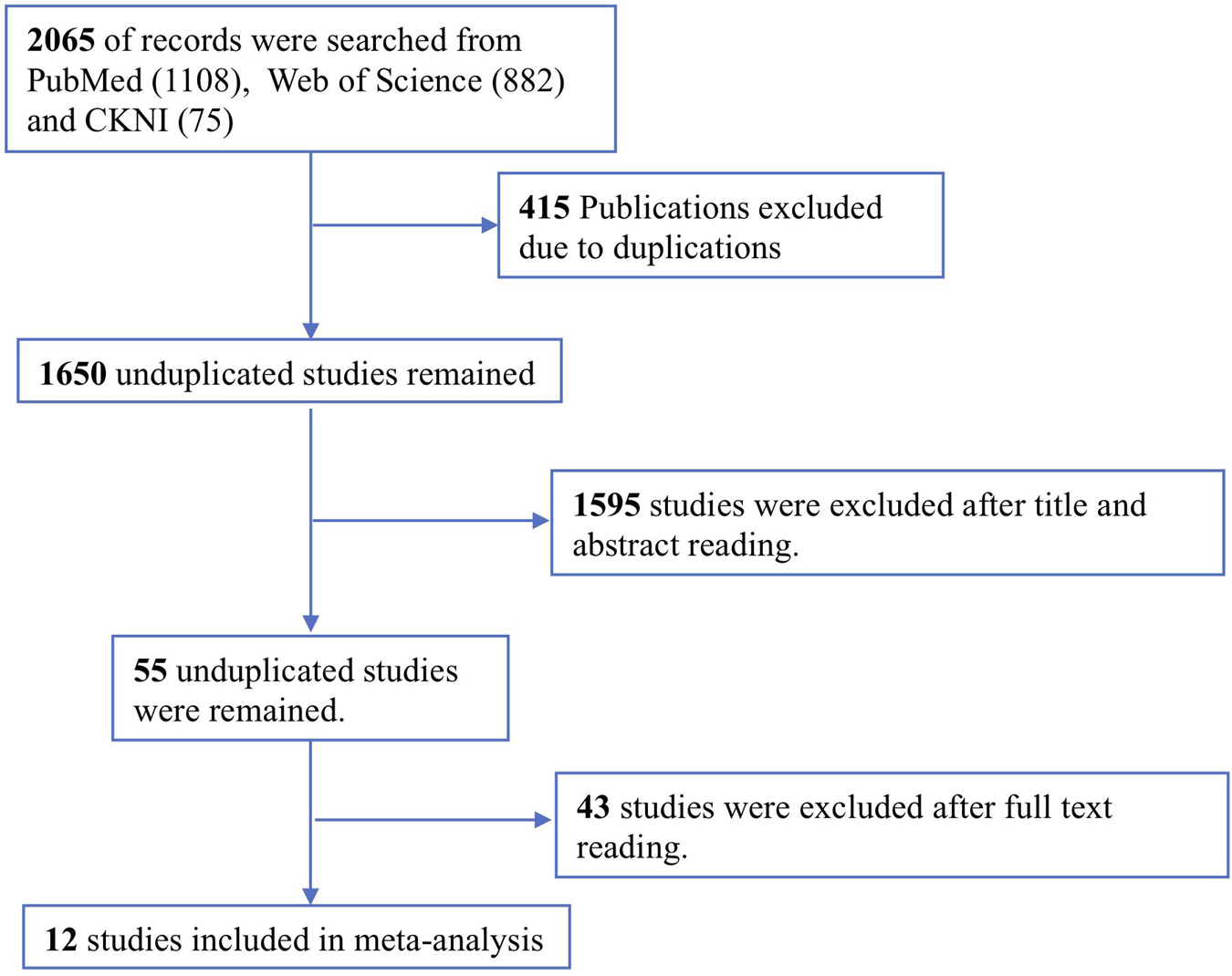

The study selection process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 2065 potentially relevant studies were identified from two English and one Chinese database using relevant search strategies. Of this relevant studies, 415 duplicates were removed. During the title and abstract screening phase of the remaining 1650 studies, an additional 1595 studies were removed. Finally, after reading the full texts of the remaining 55 articles, 43 articles were excluded, thus twelve studies were included in this meta-analysis.

Characteristics of the Induced Studies

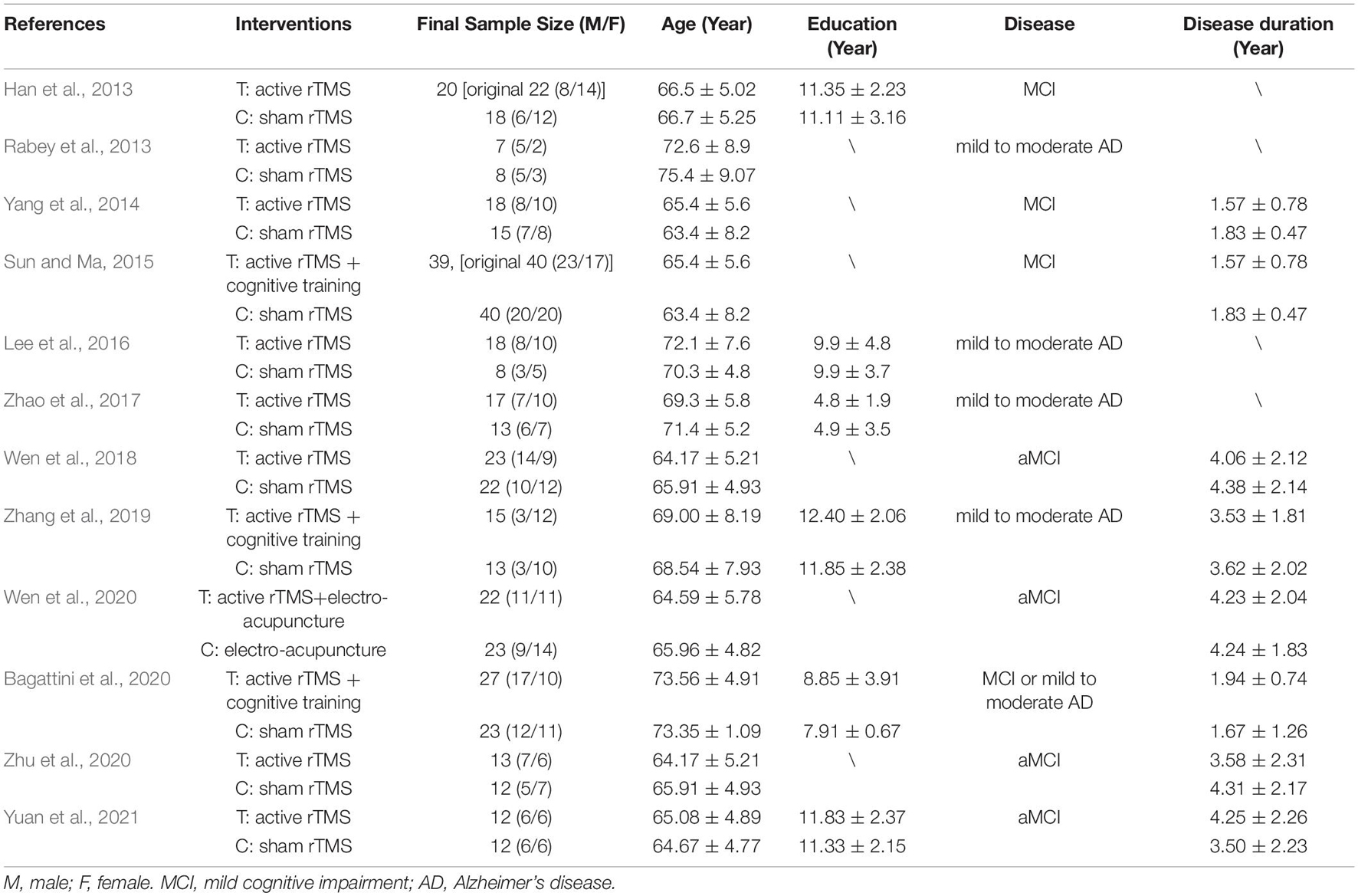

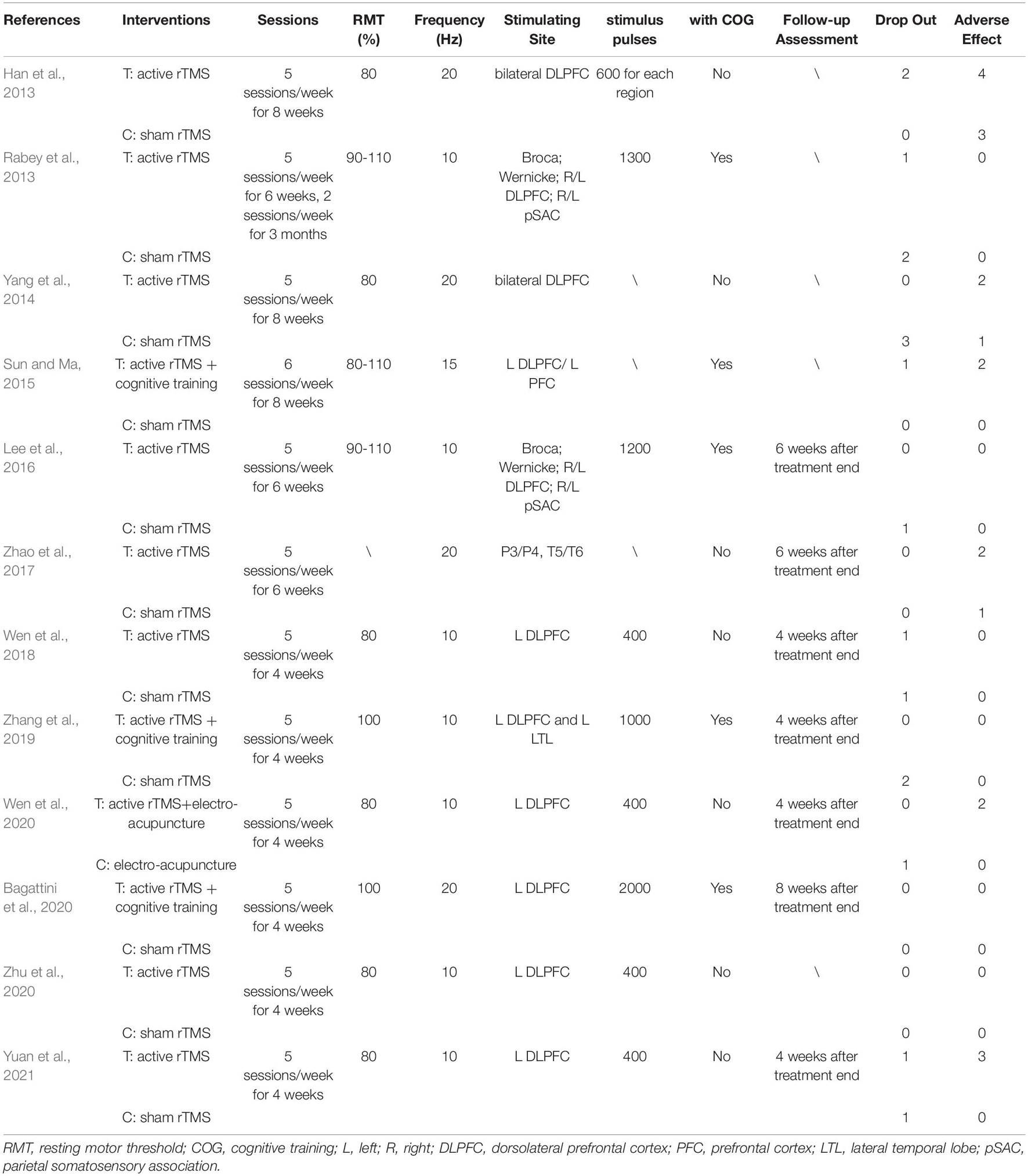

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the twelve studies included in this meta-analysis, comprising a total of 438 participants (231 in the rTMS group and 207 in the control group) (Han et al., 2013; Rabey et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Sun and Ma, 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019; Bagattini et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021). Six studies were in English (Rabey et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Bagattini et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021), and the remaining trials were in Chinese. Participants in seven studies were diagnosed as MCI (Han et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Sun and Ma, 2015; Wen et al., 2018, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021), while the participants in the rest five studies were diagnosed as mild to moderate AD. Among these five studies, two studies reported the behavioral outcomes for mild AD and moderate AD, respectively (Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). However, in the moderate subgroup of Lee et al., the score of ADAS-Cog was > 25 and the score of MMSE < 19, thus, only the mild subgroup of Lee et al. was included in the meta-analysis. Table 2 shows the characteristics of rTMS intervention in the included studies. Seven studies applied rTMS stimulation on unilateral/bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) only (Han et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2018, 2020; Bagattini et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021), and the rest of the studies applied rTMS stimulation on multiple sites, including (a) parietal lobule and temporal lobule (Zhao et al., 2017), (b) left DLPFC and prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Sun and Ma, 2015), (c) left DLPFC and left lateral temporal lobe (LTL) (Zhang et al., 2019) and (d) Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area, bilateral DLPFC and bilateral parietal somatosensory association (pSAC) (Rabey et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016). Seven studies utilized a frequency of 10 Hz (Rabey et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2018, 2020; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021), one studies used a frequency of 15 Hz (Sun and Ma, 2015) and four studies used a frequency of 20 Hz (Han et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017; Bagattini et al., 2020). The number of intervention sessions ranged from 20 to 48, and the timing for post-treatment assessment ranged from one to two month after treatment end. One study combined rTMS with electroacupuncture (Wen et al., 2020) and five studies combined rTMS with cognitive training (Rabey et al., 2013; Sun and Ma, 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019; Bagattini et al., 2020).

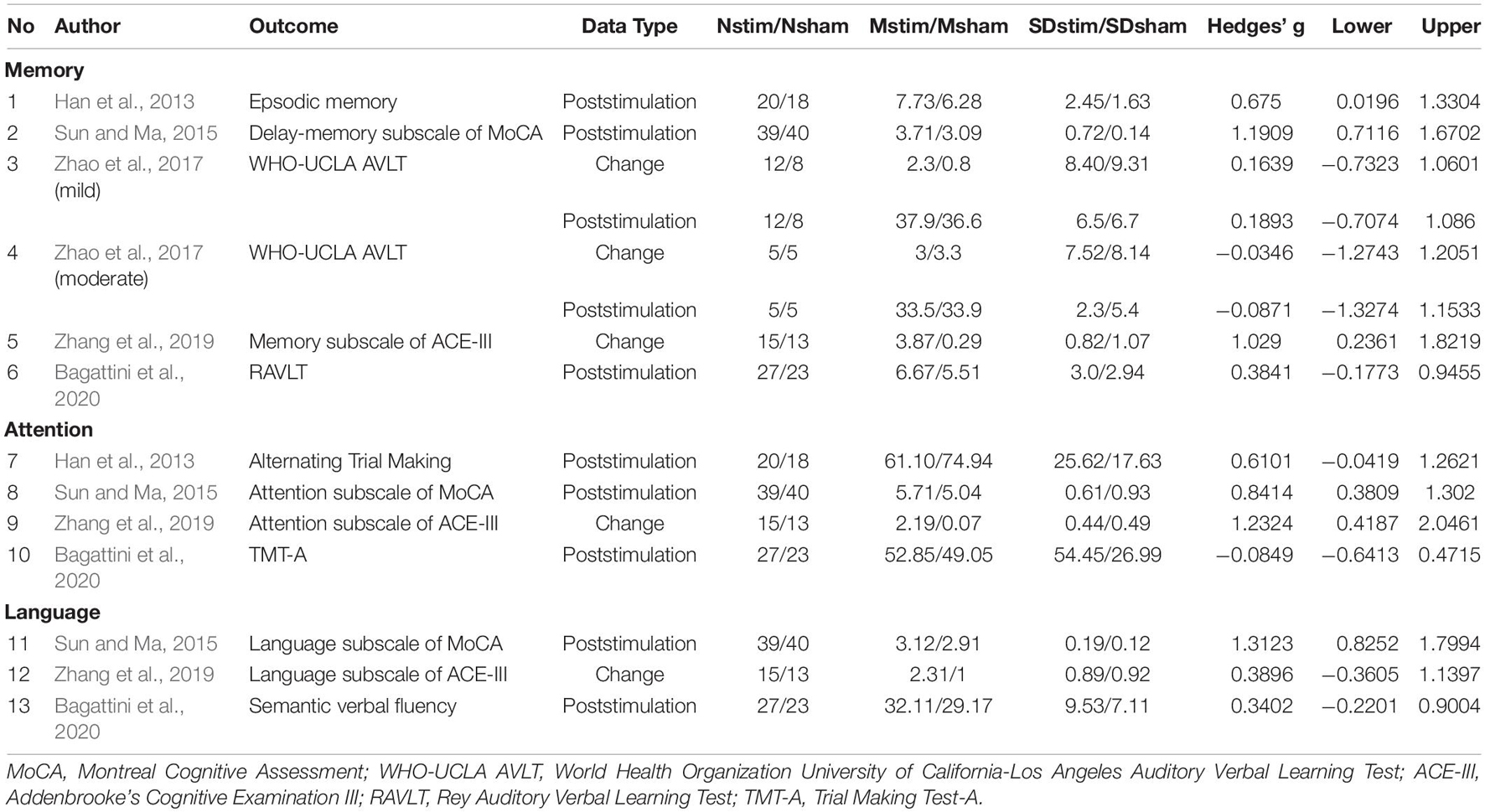

For the outcome measures, different cognitive assessments were used to assessed same cognitive domain within a study or among studies. Measures for global cognitive function included Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Yang et al., 2014; Bagattini et al., 2020), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Han et al., 2013; Sun and Ma, 2015; Wen et al., 2018, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021) and AD Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) (Rabey et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). For the memory domain, the assessment included Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) (Bagattini et al., 2020), episodic memory (Han et al., 2013), World Health Organization University of California-Los Angeles (Zhao et al., 2017), Auditory Verbal Learning Test (WHO-UCLA AVLT) (Bagattini et al., 2020), the delay memory subscale of MoCA (Sun and Ma, 2015) and the memory sub-domain of Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III) (Zhang et al., 2019). Trial Making Test-A (TMT-A) (Bagattini et al., 2020), alternating trial making (Han et al., 2013), attention subscale of MoCA (Sun and Ma, 2015) and attention sub-domain of ACE-III (Zhang et al., 2019) were used to assess the executive function and attention domain. Semantic verbal fluency (Bagattini et al., 2020), language subscale of MoCA (Sun and Ma, 2015), language sub-domain of ACE-III (Zhang et al., 2019) were used for the measurement of language ability.

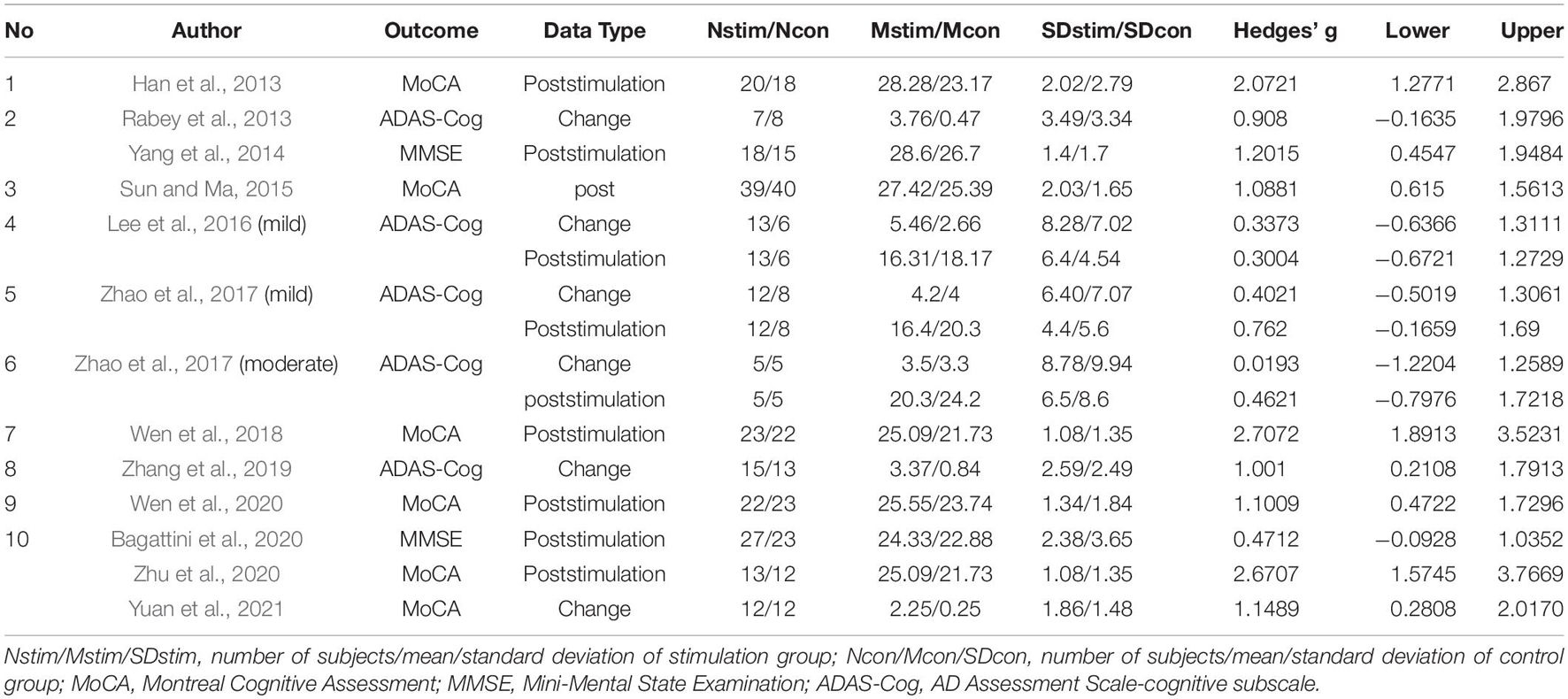

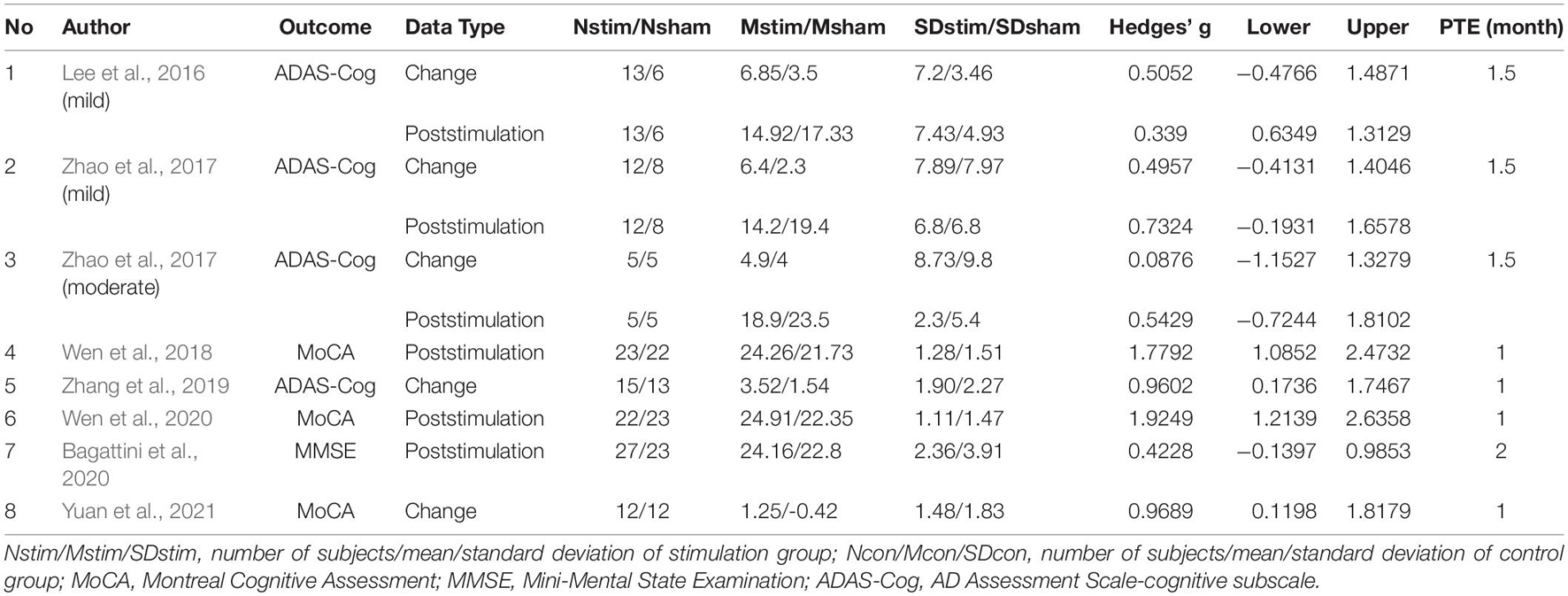

Summary of effect sizes for global cognitive function and different cognitive domains assessed immediately after the treatment end were presented by Tables 3, 4. Effect sizes of three studies were calculated according to the provided change relative to the baseline (Rabey et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2021). Effect sizes of seven studies were calculated according to the poststimulation evaluations (Han et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Sun and Ma, 2015; Wen et al., 2018, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020; Bagattini et al., 2020). Two studies provided the pre- and post-stimulation outcomes and statistical results of paired sample t-test for each group, thus the change relative to the baseline was calculated and two set of effect size were calculated with change relative to the baseline and poststimulation evaluation, respectively (Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). The effect sizes for global cognitive function assessed sometime after the treatment end were also calculated for the analysis to test the post-treatment effect of rTMS on cognitive function and the summary of the effect sizes was presented by Table 5.

Table 5. Summary of the effect sizes for global cognitive function of the post-treatment assessments.

Research Quality

The summary of the risk of bias of the included studies is shown in Figure 2. All studies declared random allocation, but only six Studies described the method used to generate the random sequence in detail and were rated as “low risk.” All studies declared double-blind, but only four studies mentioned the participants and researchers were double-blinded, thus performance bias was rated as “low risk.” The risk of attrition bias was rated as “high risk” because the research data were incomplete (due to drop-out) without enough details for two studies. The reporting bias of three studies were rated as “high risk” due to reporting their results selectively. Studies with unclear information were rated as “unclear risk”.

Meta-Analysis of Treatment Effect

Global Cognitive Function

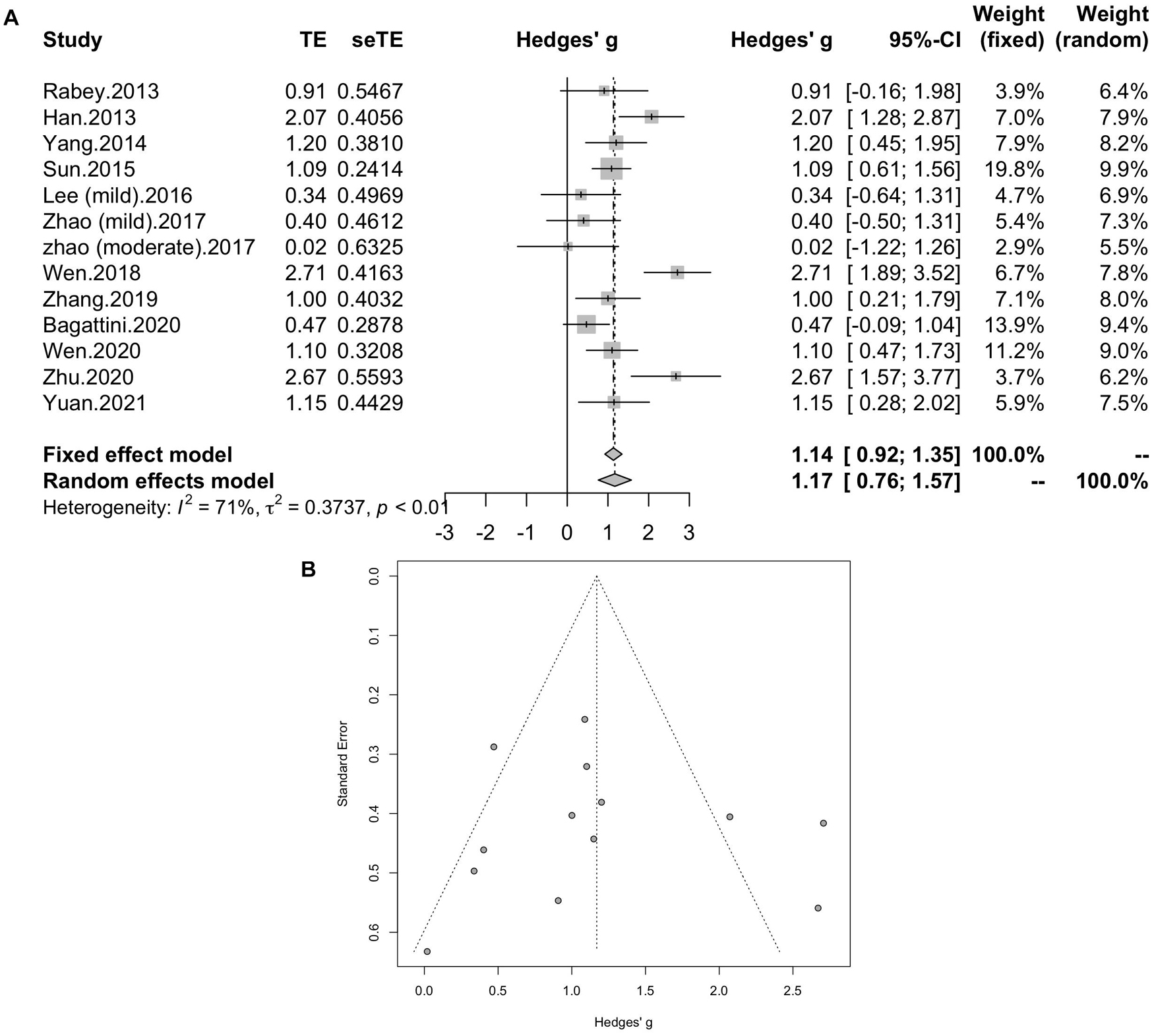

All of the twelve studies, thirteen trials assessed the effects of rTMS on global cognitive ability. The heterogeneity of the included studies was high (I2 = 70.8%, p < 0.0001), so a random-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results demonstrated that rTMS treatment significantly improved the global cognitive function in the active rTMS group with a statistically significant mean effect size of 1.17 (95% CI, 0.76 - 1.57, p < 0.0001, Figure 3A) when compared to the control group. Egger’s test was used to test the publication bias and revealed an unsignificant asymmetry (p = 0.77, funnel plot in Figure 3B). Because of the high heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was conducted and omitting the studies one by one didn’t alter the significance of effect size. Such results still remained significant by replacing the effect size of study Zhao et al. and study Lee et al. which is calculated with poststimulation evaluations (mean effect size 1.22, 95% CI: 0.83 – 1.61, p < 0.0001, Supplementary Figure 1).

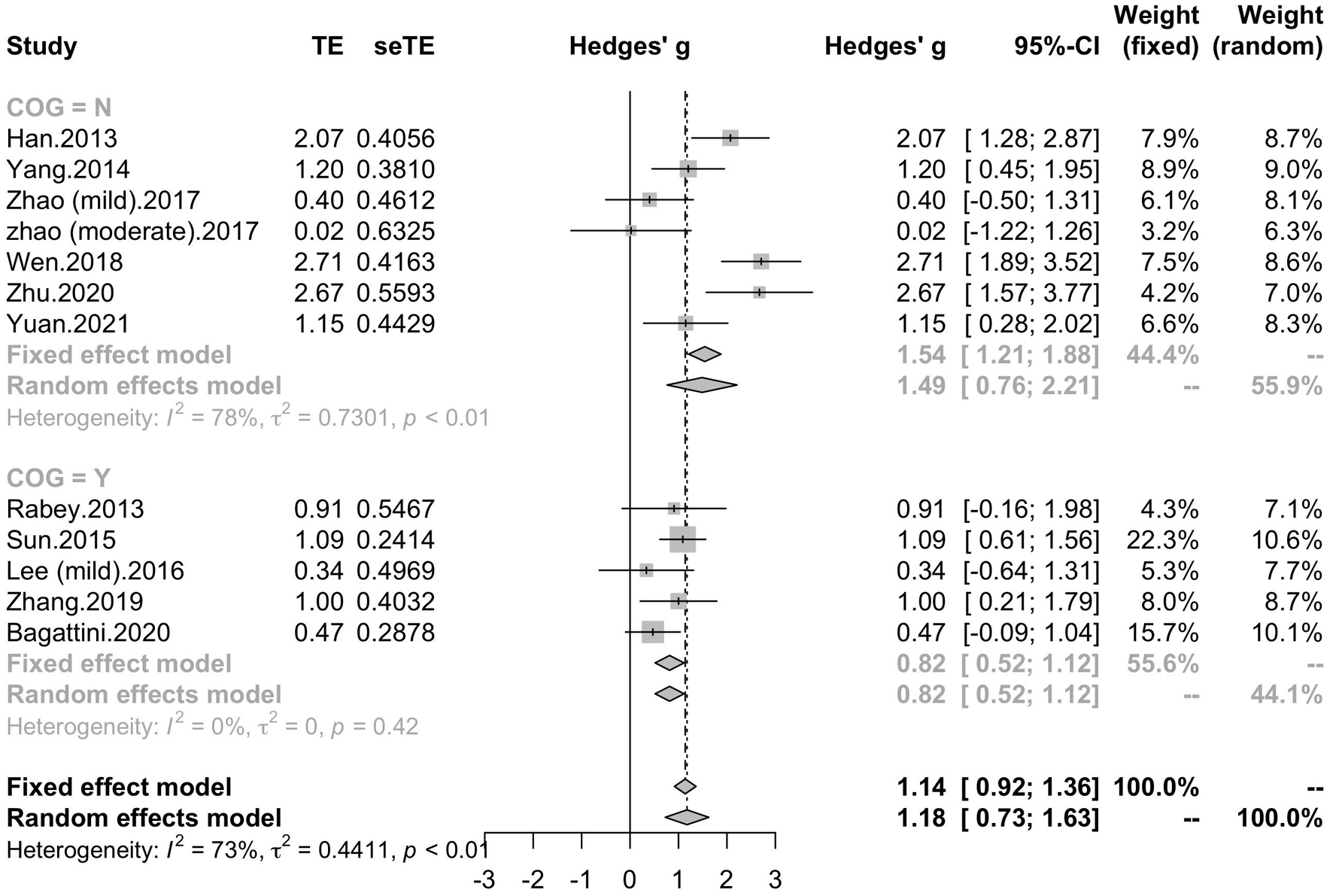

Figure 3. (A) Forest plot: mean differences in effect of rTMS on different cognitive domain in patients with MCI or early AD with 95% CI. (B) Funnel plot for the publication bias of global cognitive function.

Subgroup Analyses of Global Cognitive Function

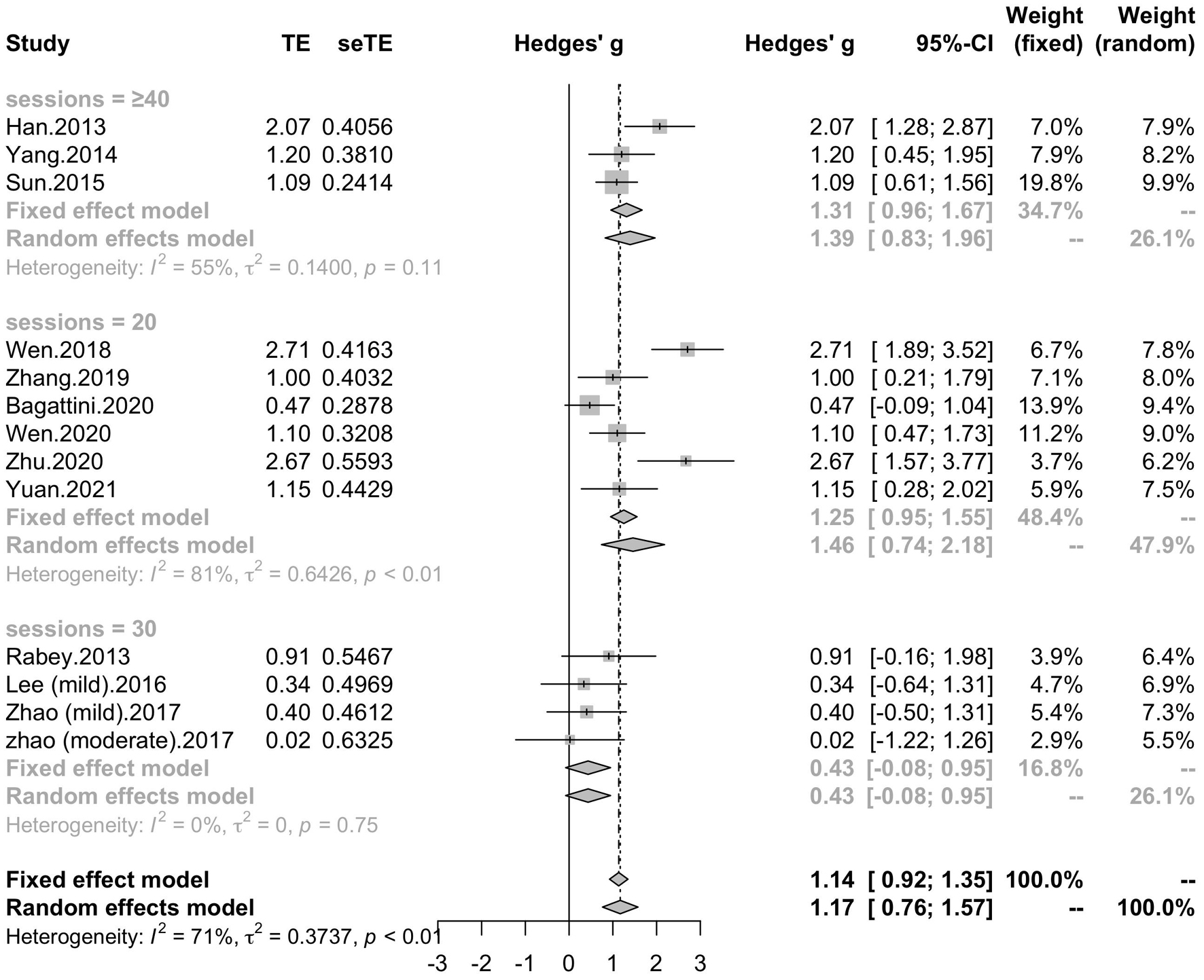

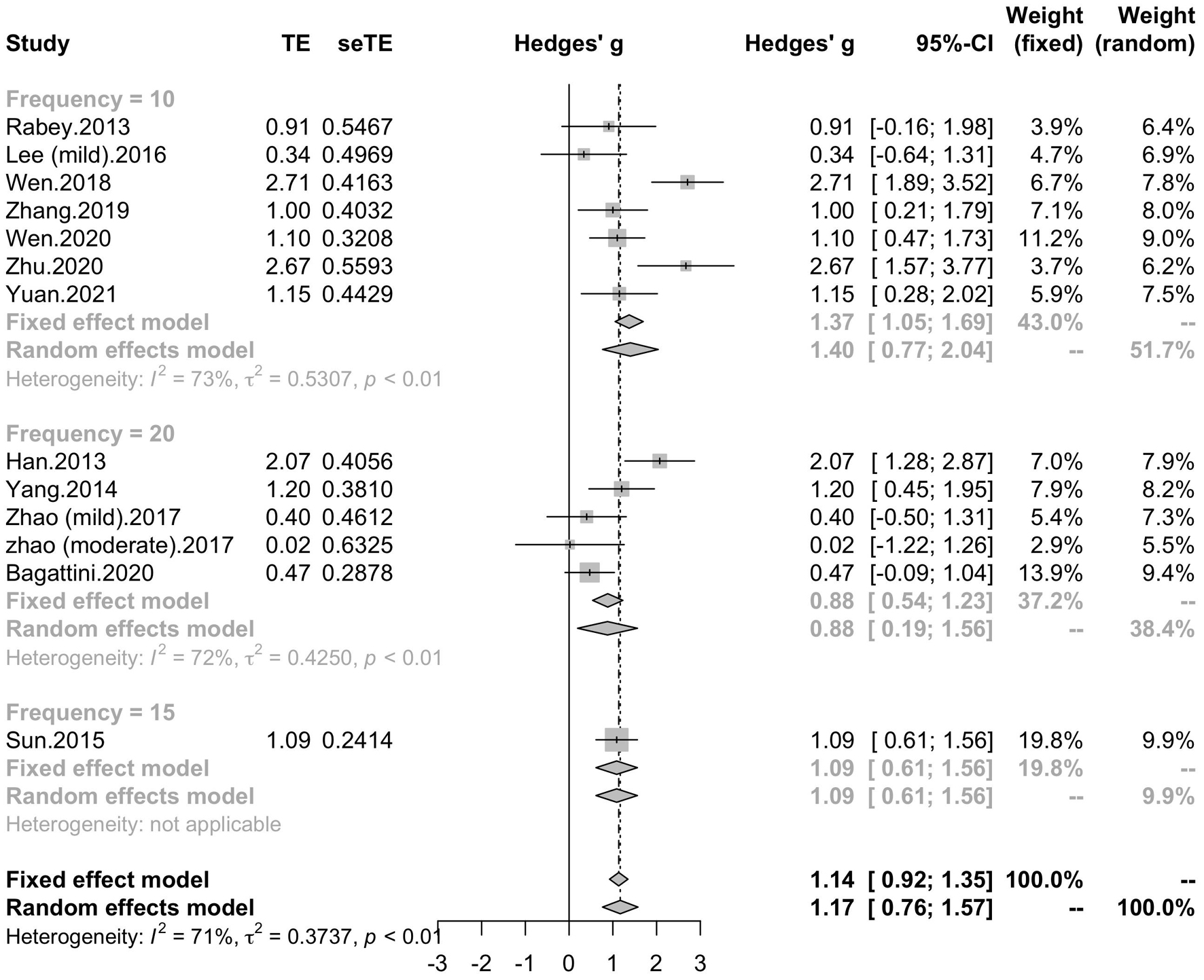

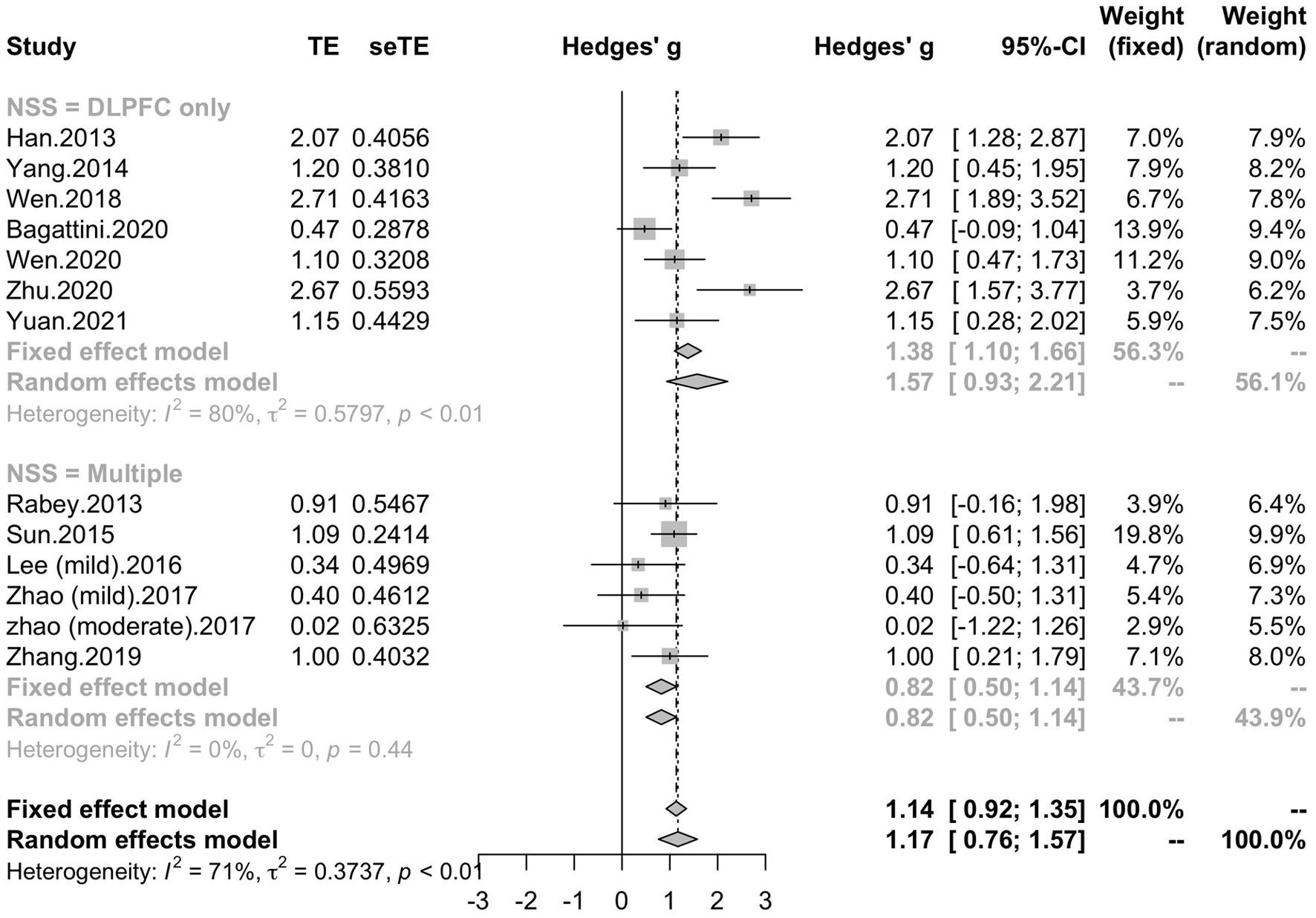

To determine variables that may influence the cognitive outcomes, several subgroups were conducted. The subgroup analysis for session number of the stimulation (“20”, “30”, “≥ 40”) revealed a mean effect size of 1.46 (95% CI, 0.74 - 2.18) for trials with 20 sessions, a mean effect size of 0.43 (95% CI, -0.08 - 0.95) for trials with 30 sessions and a mean effect size of 1.39 (95% CI, 0.83 – 1.96) for the trials with ≥ 40 sessions (Figure 4). The effect size of subgroups of session number exhibited significant between-group difference (p = 0.0175). Analysis for frequency of the stimulation (“10 Hz”, “15 Hz”, “20 Hz”) revealed a mean effect size of 1.40 (95% CI, 0.77 – 2.04) for trials with frequency of 10 Hz, a mean effect size of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.61 – 1.56) for trials with frequency of 15 Hz and a mean effect size of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.19 - 1.56) for trials with frequency of 20 Hz (Figure 5). The subgroup analysis for the stimulation site pattern (“DLPFC only” vs “multiple site”) revealed a mean effect size of 1.57 (95% CI, 0.93 - 2.21) for trials with DLPFC as single site, and a mean effect size of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.50 - 1.14) for trials with multiple sites (Figure 6). The effect size of subgroups of stimulation site exhibited significant between-group difference (p = 0.0393). The subgroup analysis for combination with cognitive training (“Yes” vs “No”) revealed a mean effect size of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.52-1.12) for trials combining rTMS with cognitive training and a mean effect size of 1.49 (95% CI, 0.76-2.21) for trials not combining rTMS with cognitive training (Figure 7). The effect size of study Zhao et al. and study Lee et al. calculated with poststimulation evaluations didn’t change the results a lot. Only the mean effect size for trials with 30 sessions (0.61, 95% CI: 0.10 – 1.13) became significant and the difference between subgroups of session number became marginally significant (p = 0.069, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 6. Forest plot: mean differences in stimulation site pattern subgroups with 95% CI. NSS, number of session site.

Figure 7. Forest plot: mean differences in cognitive training subgroups with 95% CI. COG, cognitive training.

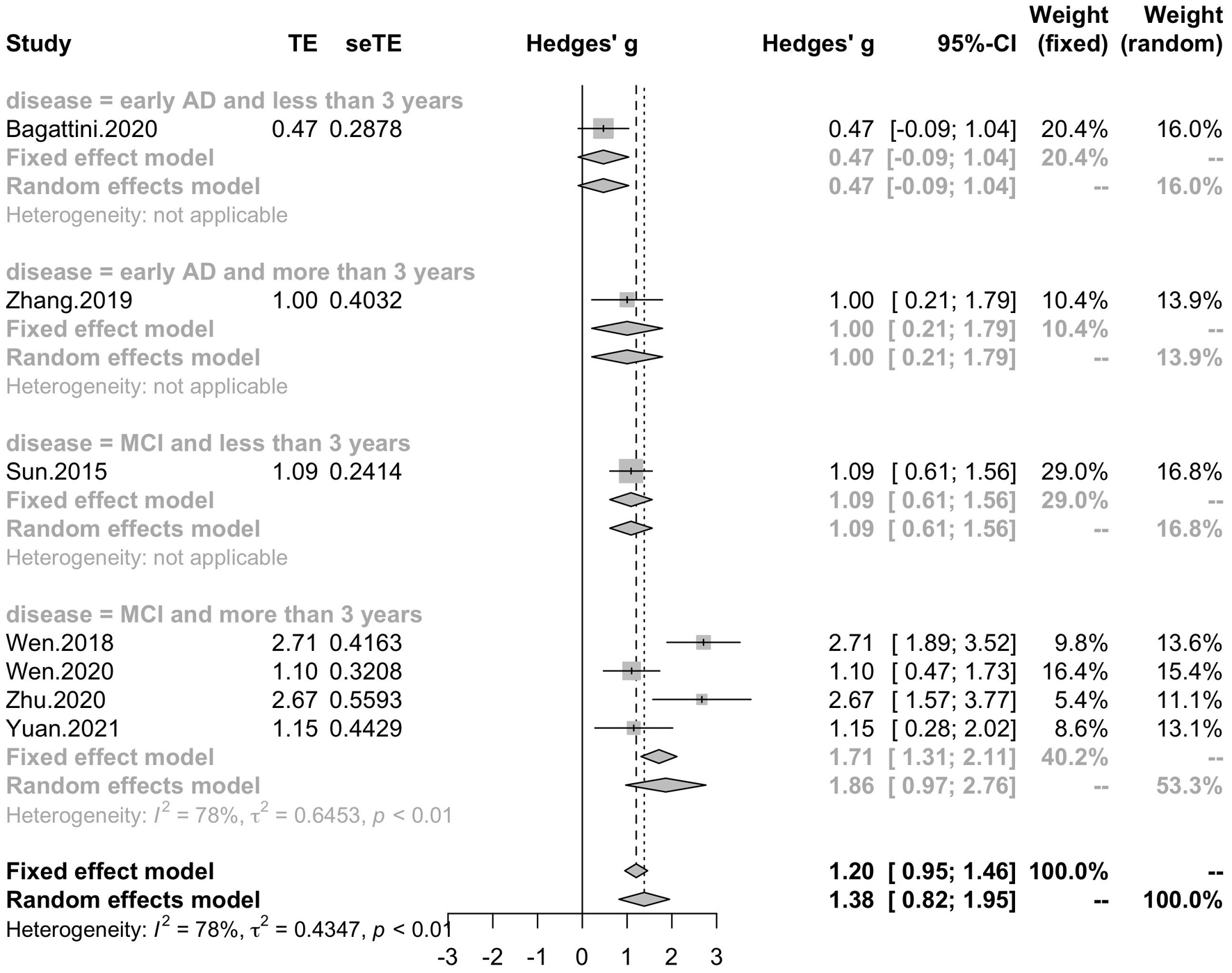

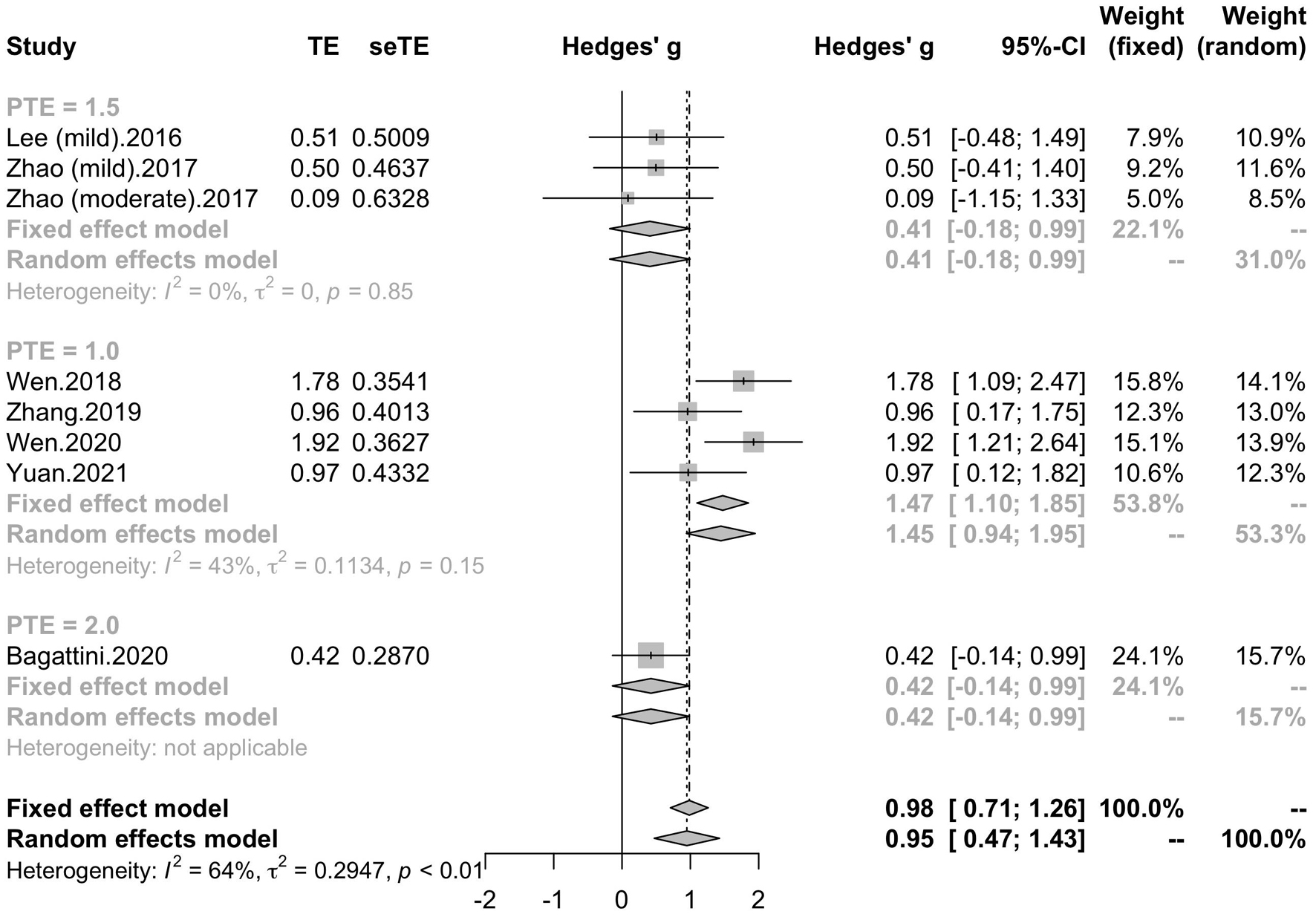

Seven studies reported the disease duration of participants. The subgroup analysis for the mean disease duration of the participants (“MCI and less than 3 years,” “MCI and more than 3 years,” “early AD and less than 3 years,” “early AD and more than 3 years) revealed a mean effect size of 1.86 (95% CI, 0.97 – 2.76) for trials with MCI patients whose disease durations were more than 3 years, a mean effect size of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.61 – 1.56) for trials with MCI patients whose disease durations were less than 3 years, a mean effect size of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.21 – 1.79) for trials with early AD patients whose disease duration were more than 3 years and a mean effect size of 0.47 (95% CI, -0.09 – 1.04) for trials with early AD patients whose disease duration were less than 3 years (Figure 8). Seven studies included eight trials reported post-treatment effect at different time points after the end of the treatment. The subgroup analysis for the post-treatment effect (“one month” vs “one and a half month” vs “two months”) revealed a mean effect size of 1.45 (95% CI, 0.94 – 1.95) for trials in which the post-treatment effect was assessed one month after the end of the treatment, a mean effect size of 0.41 (95% CI, -0.18 – 0.99) for trials in which the post-treatment effect was assessed one and a half months after the end of treatment and a mean effect size of 0.42 (95% CI, -0.14 – 0.99) for trials in which the post-treatment effect was assessed two months after the end of treatment (Figure 9). The effect size of subgroups of post-treatment effect exhibited significant between-group difference (p = 0.0075). With the effect size of study Zhao et al. and study Lee et al. calculated with poststimulation evaluations, the mean effect size for trials in which the post-treatment effect was assessed one and a half months after the treatment end (0.39, 95% CI: 0.09 – 0.70) became significant (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 9. Forest plot: mean differences in post-treatment effect subgroup with 95% CI. PTE, post-treatment effect.

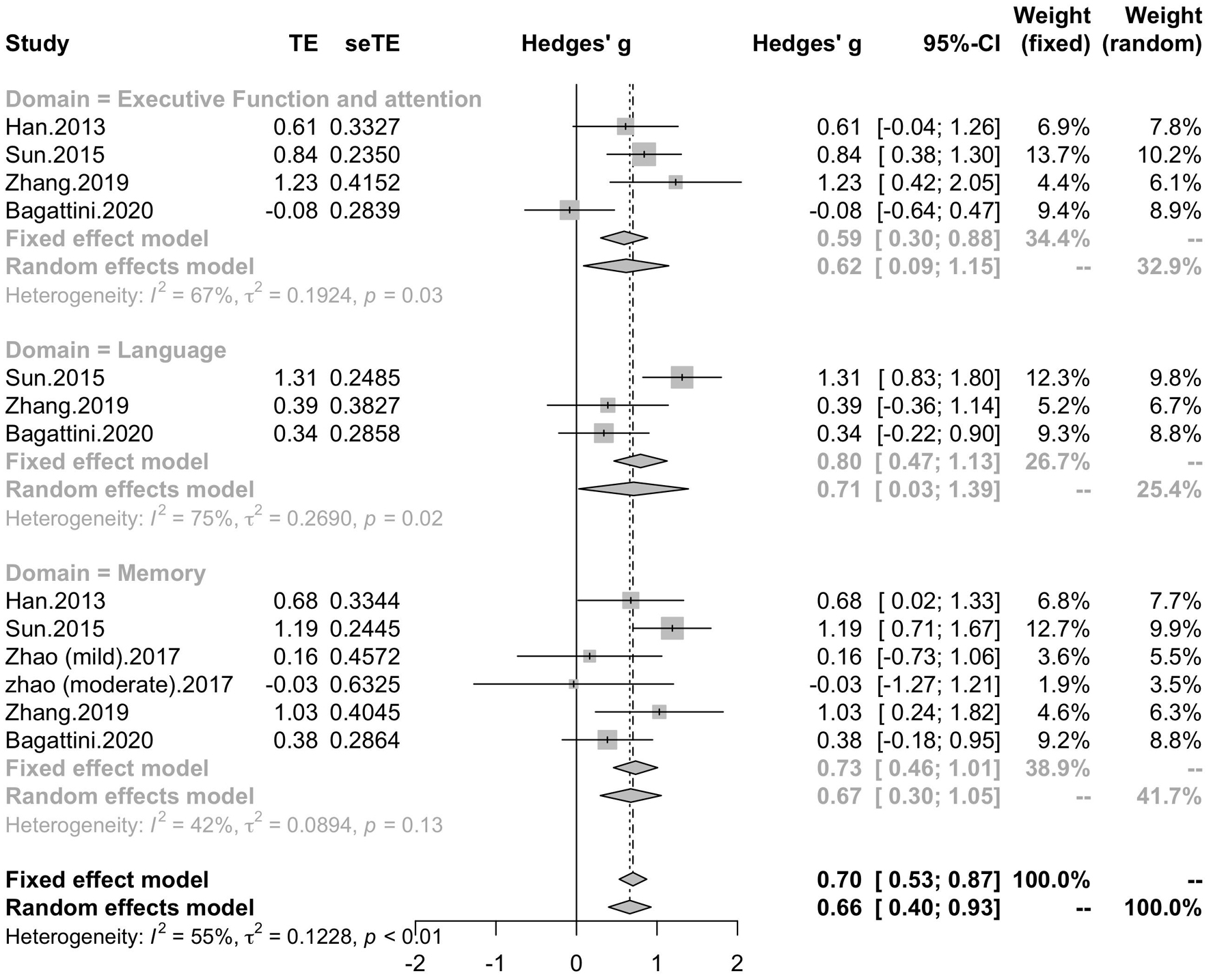

Memory, Executive Function and Attention, Language

Five studies included six trials reported the effect of rTMS on memory, while four studies reported the effect of rTMS on executive function and attention, and three studies reported the effect of rTMS on language. Subgroup analysis was conducted to test the effect of rTMS on these different domains, and a mean effect size of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.30 – 1.05) for trails of memory domains, a mean effect size of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.09 – 1.15) for trials of executive function and attention domains and a mean effect size of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.03 – 1.39) for trials of language (Figure 10). The effect size of study Zhao et al. and study Lee et al. calculated with poststimulation evaluations didn’t change the significance of effect size (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 10. Forest plot: mean difference in effect of rTMS on different cognitive domain in patients with MCI or early AD with 95% CI.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis included thirteen studies with randomized, double-blind and controlled trials. These results added strong evidence for the efficacy of rTMS on cognitive improvement in patients with MCI and mild to moderate AD, not only in global cognitive function, but also in memory, language and executive function and attention. According to the subgroup analyses conducted to explore the proper stimulation patterns, most settings of rTMS parameters enhanced the global cognitive function, and the results revealed that rTMS protocols with stimulating frequency in 10 Hz and DLPFC as the stimulating site for 20 sessions would be able to produce benefit for the cognitive function. Besides, the post-treatment of rTMS has also be tested, and the result suggested a post-treatment effect on cognitive function for about one month and patients with MCI were likely to benefit more from the rTMS stimulation.

Consistent with the previous studies, the current results supported the benefit of rTMS on cognitive function in patients with MCI and AD, not only in the global cognitive outcomes, but also in the performance of memory, executive function and attention, and language. The impairments of memory, language and attention were cognitive manifestations of AD (Bracco et al., 2009; Jahn, 2013; Mueller et al., 2018; Malhotra, 2019). Recently, researchers have tested the effect of rTMS treatment on these cognitive domains and reported the cognitive benefit of rTMS on global cognitive function and sub-domains, like memory, language and executive function (Cotelli et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2018; Padala et al., 2018; Cui et al., 2020). It has been proposed that rTMS can modulate the cortical coactivation in the cognitive function-related brain areas (Cotelli et al., 2011). Previous studies demonstrated that rTMS of high frequency would facilitate cortical excitability and induce long-term potentiation (LTP) which has been implicated to be related to learning and memory (Motta et al., 2018; Di Lorenzo et al., 2019, 2020). The activation of the stimulation site would facilitate the connected larger-scale network and thus induce cognitive improvement in the multiple cognitive domains revealed by the current results.

Recent rTMS protocols have proposed the combination of rTMS and cognitive training, and our results also provide evidence to the improvement effect of the combination of rTMS and cognitive training on the cognitive performance (Bentwich et al., 2011; Das et al., 2019; Chu et al., 2020). It has been proposed that rTMS trials with cognitive training would combine the “exogenous” and “endogenous” stimulation to enhance neuroplasticity, in which the rTMS may be capable of pre-activating the initial state of neural system and the subsequent cognitive training would interact with the ongoing brain activation to potentiate or generalize the related neural impact (Miniussi and Rossini, 2011; Miniussi and Vallar, 2011; Bagattini et al., 2020). Thus, the cognitive training might be able to modulate the effect of rTMS, and might explain why the rTMS studies with cognitive training seemed to be more consistent than those studies without cognitive training. Besides, our current subgroup analysis of session number revealed that rTMS with more than 20 sessions might be able to produce cognitive enhancement in patients with MCI or early AD, which is consistent with previous studies (Lin et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). However, the effect size of trials with 30 sessions seemed to be smaller than the effect size of trials with 20 session and with 40 sessions. The characteristics of trials have been checked and one alterative explanation was that the trials with 30 sessions had small sample sizes (most of them had less than 10 subjects for each group) and thus would limit the statistical power and resulted in lack of actual effects. Thus, trials with larger sample are in expectation to better test the effect of different rTMS parameters.

Different stimulation sites were used in the included studies of the current meta-analysis and subgroup analysis was conducted to test if rTMS treatment supported the cognitive improvement with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) used as the only stimulation brain area. Seven studies utilized left DLPFC or bilateral DLPFC as stimulation sites and other five studies utilized multiple brain regions. The results showed that those trials which stimulated DLPFC only (unilateral or bilateral) can improve the cognitive outcomes in patients with MCI and AD with an effect size significantly higher than those trials with multiple sites. DLPFC has been demonstrated as an important brain area subserving higher-level cognition and the its pathological change has been considered as a hallmark feature of AD from its early stage (Braak and Braak, 1991; Kumar et al., 2017). Besides, DLPFC has been considered as a key region playing important role in several large-scale brain networks, such as fronto-parietal network (FPN) and central executive network (CEN) (Agosta et al., 2012; Opitz et al., 2016). Considering its pivotal association with the cognitive impairment of AD, DLPFC has been used as stimulation site commonly in trials aiming to improving cognitive function in patients with AD. One study reported that rTMS at 5 Hz over left DLPFC would achieve similar cognitive improvement in AD patients compared to stimulation over multiple sites (Alcala-Lozano et al., 2018). The researchers proposed that left DLPFC connected with a variety of brain structures potentially involved in the pathophysiological progression in AD and thus the stimulation of DLPFC would also stimulate the areas engaged in the multi-site approach and produce equally positive outcomes (Alcala-Lozano and Garza-Villarreal, 2018). Although the results should be considered with caution due to its lack of a neuronavigator for the rTMS therapy, it still indicated the important role of DLPFC for rTMS stimulation. Besides, the efficacy of stimulation over unilateral or bilateral DLPFC is still under debate. A meta-analysis reported higher efficacy of right or bilateral DLPFC rTMS on cognitive outcomes over left DLPFC rTMS (Liao et al., 2015), and another study reported rTMS with a stimulation sequence of left DLPFC then right DLPFC was effective for cognitive outcomes (Ahmed et al., 2012). While the high-frequency rTMS over left/bilateral DLPFC has been reported to be effective on cognitive function, it has been reported that low-frequency rTMS of right DLPFC enhanced recognition memory in eight subjects with MCI (Turriziani et al., 2012). It has been proposed that the inhibition of the right DLPFC might modulated the activity of the dysfunctional network and thus restoring an adaptive equilibrium in MCI. Thus, further studies with DLPFC as stimulation site combining with multiple-modality data are needed to explore the efficacy of rTMS stimulation over DLPFC and its underlying mechanism.

How long would the cognitive benefit of rTMS in patients of MCI and AD prolong is another important issue that people care about. The current meta-analysis showed a significant effect size for the trials which tested the lasting effect one month after the treatment end. It has been reported that rTMS is able to induce long-lasting changes of cortical excitability (Nardone et al., 2014), and whether these changes would last after stopping the rTMS is still under exploration. Several studies utilized multi-timepoint assessments to test the lasting effect of rTMS (Lee et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017; Bagattini et al., 2020). Cotelli et al. has reported that with a 2-week rTMS stimulation over left parietal cortex, aMCI patients improved their accuracy in an association memory task and such improvement remained significant 24 weeks after stimulation began (Cotelli et al., 2012). However, there are limitations that some studies lacked of data in the control group and cannot provide a better evaluation for the effect of rTMS. The current results suggested that the alteration of brain mechanism induced by rTMS might still support the improvement of global cognitive function for about one month even without the rTMS treatment when compared to the control group. Considering the small number of trials included in each subgroup, particularly for post-treatment effect assessed two months after the treatment end, the current results should be interpreted with caution and more studies still in need to provide evidence for the long-lasting effect of rTMS.

Except the post-treatment effect of rTMS, we also tested whether pre-treatment condition of patients would influence the effect of rTMS on the global cognitive function. Our results revealed that patients with lighter clinical manifestation and longer disease duration seemed to benefit more from rTMS treatment. It might suggest that patients with less cognitive impairment, or degenerating slower (have maintained in such stage for a longer time), might reflect a better pre-treatment brain mechanism compared to the patients whose symptoms worsened to a similar level in shorter duration, and thus would enable rTMS to be more efficient. Previous studies have reported the difference of LTP introduced by rTMS among different stage of AD, while the induced LTP has been regarded as the pivotal mechanism in which the rTMS treatment can support the cognitive benefit in AD patients (Maeda et al., 2000; Tegenthoff et al., 2005; Di Lorenzo et al., 2019, 2020). rTMS intervention has also be reported to be more marked cognitive benefit in patients at an early state of AD (Rutherford et al., 2015). It has also been reported that the variability of rTMS induced cognitive after-effects would be influenced by gray mater atrophy of AD-related brain regions (Anderkova et al., 2015). Current results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of trials, however, it still called attention to applying intervention earlier and emphasized the importance to explore the biomarkers of pre-treatment brain mechanism for rTMS in developing better and individual-specific intervention protocol.

Limitation

A few limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of the current study. First, with constrained inclusion criteria, the number of trials included in the meta-analysis is limited, and although Hedges’ g was used as SMD, the sample sizes of the included studies were small, which might limit the statistical power to detect the effects of rTMS on cognitive function in patients with MCI or early AD. Second, we can’t assess the change of treatment relative to the baseline for all the studies, and according to the effect sizes of the two studies (Lee et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017), we found that there is a little difference between effect sizes calculated with change relative to the baseline and those calculated with poststimulation outcomes, and thus induced a small shift of the effect size in some subgroup analyses. The evaluation of the rTMS cognitive effect would be more reliable with the effect size calculated by the change relative to the baseline, but the practical analysis was limited by the difficulty to assess the data. Third, optimal rTMS parameters remained unclear because of the relatively high heterogeneity of the included studies in the subgroup analyses of stimulation parameters (frequency, session number, stimulation site). Further randomized, double-blinded and controlled rTMS studies focusing on MCI or early AD are in expectation to be more sophisticated designed and better result-reporting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our meta-analysis provided evidence that rTMS therapy in patients with MCI or early AD can significantly improve not only global cognitive ability, but also memory, executive function and language when compared to the control group. Most settings of rTMS parameter can significantly improve the global cognitive function and the results showed that rTMS protocol with frequency of 10 Hz and DLPFC as stimulation site for continuous 20 sessions would be capable to produce cognitive benefit. The cognitive benefit of rTMS treatment can last for about one month after the end of treatment. Patients with earlier course of AD would be more likely to benefit more from rTMS treatment. Current study provided critical information for optimal parameters of rTMS therapy and indicate the importance to consider the pre-treatment physiological condition of patients when evaluated the effect of rTMS therapy in patients with MCI and early AD. Further researches with larger sample sizes and better experiment design were crucially needed to identify the optimal parameters of rTMS intervention on cognition of AD patients.

Author Contributions

YK conceived and supervised the study. YX, LN, and WZ screened literature and data extraction. YX and ZK performed statistical analyses. YX, ZK, and YK wrote the manuscript. YL edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 32171082 and 81671307), the National Social Science Foundation of China (17ZDA323), the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (19ZR1416700), the Database Project of Tongji Hospital of Tongji University (Grant No. TJ(DB)2102), and the Hundred Top Talents Program at Sun Yat-sen University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.734046/full#supplementary-material

References

Agosta, F., Pievani, M., Geroldi, C., Copetti, M., Frisoni, G. B., and Filippi, M. (2012). Resting state fMRI in Alzheimer’s disease: beyond the default mode network. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1564–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.007

Ahmed, M. A., Darwish, E. S., Khedr, E. M., El Serogy, Y. M., and Ali, A. M. (2012). Effects of low versus high frequencies of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive function and cortical excitability in Alzheimer’s dementia. J. Neurol. 259, 83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6128-4

Alcala-Lozano, R., and Garza-Villarreal, E. A. (2018). Overlap of large-scale brain networks may explain the similar cognitive improvement of single-site vs multi-site rTMS in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Stimul. 11, 942–944. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.03.016

Alcala-Lozano, R., Morelos-Santana, E., Cortes-Sotres, J. F., Garza-Villarreal, E. A., Sosa-Ortiz, A. L., and Gonzalez-Olvera, J. J. (2018). Similar clinical improvement and maintenance after rTMS at 5 Hz using a simple vs. complex protocol in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Stimul. 11, 625–627. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.12.011

Anderkova, L., Eliasova, I., Marecek, R., Janousova, E., and Rektorova, I. (2015). Distinct pattern of gray matter atrophy in mild Alzheimer’s disease impacts on cognitive outcomes of noninvasive brain stimulation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 48, 251–260. doi: 10.3233/jad-150067

Bagattini, C., Zanni, M., Barocco, F., Caffarra, P., Brignani, D., Miniussi, C., et al. (2020). Enhancing cognitive training effects in Alzheimer’s disease: rTMS as an add-on treatment. Brain Stimul. 13, 1655–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.09.010

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., and Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 22, 153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

Bentwich, J., Dobronevsky, E., Aichenbaum, S., Shorer, R., Peretz, R., Khaigrekht, M., et al. (2011). Beneficial effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a proof of concept study. J. Neural Transm. 118, 463–471. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0578-1

Birba, A., Ibanez, A., Sedeno, L., Ferrari, J., Garcia, A. M., and Zimerman, M. (2017). Non-invasive brain stimulation: a new strategy in mild cognitive impairment? Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:16.

Braak, H., and Braak, E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259. doi: 10.1007/bf00308809

Bracco, L., Giovannelli, F., Bessi, V., Borgheresi, A., Di Tullio, A., Sorbi, S., et al. (2009). Mild cognitive impairment: loss of linguistic task-induced changes in motor cortex excitability. Neurology 72, 928–934. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344153.68679.37

Breton, A., Casey, D., and Arnaoutoglou, N. A. (2019). Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 34, 233–242. doi: 10.1002/gps.5016

Chang, C.-H., Lane, H.-Y., and Lin, C.-H. (2018). Brain stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Psychiatry 9:201.

Chou, Y.-H., Viet Ton, T., and Sundman, M. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of rTMS effects on cognitive enhancement in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 86, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.08.020

Chu, C.-S., Li, C.-T., Brunoni, A. R., Yang, F.-C., Tseng, P.-T., Tu, Y.-K., et al. (2020). Cognitive effects and acceptability of non-invasive brain stimulation on Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a component network meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92, 195–203. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323870

Cotelli, M., Calabria, M., Manenti, R., Rosini, S., Maioli, C., Zanetti, O., et al. (2012). Brain stimulation improves associative memory in an individual with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurocase 18, 217–223. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2011.588176

Cotelli, M., Calabria, M., Manenti, R., Rosini, S., Zanetti, O., Cappa, S. F., et al. (2011). Improved language performance in Alzheimer disease following brain stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 794–797. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.197848

Cui, X., Ren, W., Zheng, Z., and Li, J. (2020). repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improved source memory and modulated recollection-based retrieval in healthy older adults. Front. Psychol. 11:1137.

Das, N., Spence, J. S., Aslan, S., Vanneste, S., Mudar, R., Rackley, A., et al. (2019). Cognitive training and transcranial direct current stimulation in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized pilot trial. Front. Neurosci. 13:307.

Di Lorenzo, F., Motta, C., Bonnì, S., Mercuri, N. B., Caltagirone, C., Martorana, A., et al. (2019). LTP-like cortical plasticity is associated with verbal memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Brain Stimul. 12, 148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.10.009

Di Lorenzo, F., Motta, C., Casula, E. P., Bonnì, S., Assogna, M., Caltagirone, C., et al. (2020). LTP-like cortical plasticity predicts conversion to dementia in patients with memory impairment. Brain Stimul. 13, 1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.05.013

Han, K., Yu, L., Wang, L., Li, N., Liu, K., Xu, S., et al. (2013). The case-control study of the effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on elderly mild cognitive impairment patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 23, 156–159, (in Chinese).

Jiang, L., Cui, H., Zhang, C., Cao, X., Gu, N., Zhu, Y., et al. (2021). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for improving cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12:593000.

Koch, G., Bonni, S., Pellicciari, M. C., Casula, E. P., Mancini, M., Esposito, R., et al. (2018). Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the precuneus enhances memory and neural activity in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 169, 302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.048

Koch, G., Martorana, A., and Caltagirone, C. (2020). Transcranial magnetic stimulation: emerging biomarkers and novel therapeutics in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 719:134355. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134355

Kumar, S., Zomorrodi, R., Ghazala, Z., Goodman, M. S., Blumberger, D. M., Cheam, A., et al. (2017). Extent of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plasticity and its association with working memory in patients with alzheimer disease. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3292

Lee, J., Choi, B. H., Oh, E., Sohn, E. H., and Lee, A. Y. (2016). Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Neurol. 12, 57–64. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.1.57

Liao, X., Li, G., Wang, A., Liu, T., Feng, S., Guo, Z., et al. (2015). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an alternative therapy for cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 48, 463–472. doi: 10.3233/jad-150346

Lin, Y., Jiang, W.-J., Shan, P.-Y., Lu, M., Wang, T., Li, R.-H., et al. (2019). The role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 398, 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.038

Luber, B., and Lisanby, S. H. (2014). Enhancement of human cognitive performance using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Neuroimage 85(Pt 3), 961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.007

Maeda, F., Keenan, J. P., Tormos, J. M., Topka, H., and Pascual-Leone, A. (2000). Interindividual variability of the modulatory effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical excitability. Exp. Brain Res. 133, 425–430. doi: 10.1007/s002210000432

Malhotra, P. A. (2019). Impairments of attention in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 29, 41–48.

Miniussi, C., and Rossini, P. M. (2011). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in cognitive rehabilitation. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 21, 579–601. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.562689

Miniussi, C., and Vallar, G. (2011). Brain stimulation and behavioural cognitive rehabilitation: a new tool for neurorehabilitation? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 21, 553–559. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.622435

Motta, C., Di Lorenzo, F., Ponzo, V., Pellicciari, M. C., Bonnì, S., Picazio, S., et al. (2018). Transcranial magnetic stimulation predicts cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 89, 1237–1242. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317879

Mueller, K. D., Hermann, B., Mecollari, J., and Turkstra, L. S. (2018). Connected speech and language in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a review of picture description tasks. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 40, 917–939. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2018.1446513

Nardone, R., Tezzon, F., Hoeller, Y., Golaszewski, S., Trinka, E., and Brigo, F. (2014). Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)/repetitive TMS in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 129, 351–366. doi: 10.1111/ane.12223

Nguyen, J.-P., Suarez, A., Kemoun, G., Meignier, M., Le Saout, E., Damier, P., et al. (2017). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurophysiol. Clin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 47, 47–53.

Opitz, A., Fox, M. D., Craddock, R. C., Colcombe, S., and Milham, M. P. (2016). An integrated framework for targeting functional networks via transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage 127, 86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.040

Padala, P. R., Padala, K. P., Lensing, S. Y., Jackson, A. N., Hunter, C. R., Parkes, C. M., et al. (2018). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for apathy in mild cognitive impairment: a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled, cross-over pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 261, 312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.063

Petersen, R. C., Smith, G. E., Waring, S. C., Ivnik, R. J., Tangalos, E. G., and Kokmen, E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 56, 303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303

Rabey, J. M., Dobronevsky, E., Aichenbaum, S., Gonen, O., Marton, R. G., and Khaigrekht, M. (2013). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training is a safe and effective modality for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind study. J. Neural Transm. 120, 813–819. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0902-z

Rutherford, G., Lithgow, B., and Moussavi, Z. (2015). Short and long-term effects of rTMS treatment on Alzheimer’s disease at different stages: a pilot study. J. Exp. Neurosci. 9, 43–51.

Sun, R., and Ma, Y. (2015). Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training on mild cognitive impairment. Chin. J. Rehabil. 30, 355–357, (in Chinese).

Tegenthoff, M., Ragert, P., Pleger, B., Schwenkreis, P., Forster, A. F., Nicolas, V., et al. (2005). Improvement of tactile discrimination performance and enlargement of cortical somatosensory maps after 5 Hz rTMS. PLoS Biol. 3:e362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030362

Turriziani, P., Smirni, D., Zappala, G., Mangano, G. R., Oliveri, M., and Cipolotti, L. (2012). Enhancing memory performance with rTMS in healthy subjects and individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: the role of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:62.

Wang, X., Mao, Z., Ling, Z., and Yu, X. (2020). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neurol. 267, 791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09644-y

Wen, X., Cao, X., Qiu, G., Dou, Z., and Chen, S. (2018). Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Chin. J. Gerontol. 38, 1662–1663, (in Chinese).

Wen, X., Xie, M., Chen, S., and Dou, Z. (2020). Effect of combined rTMS with electroacupuncture on amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 40, 1192–1195, (in Chinese).

Yang, L., Han, K., Wang, X., An, C., Xu, S., Song, M., et al. (2014). Preliminary study of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Chin. J. Psychiatry 47, 227–231, (in Chinese).

Yuan, L. Q., Zeng, Q., Wang, D., Wen, X. Y., Shi, Y., Zhu, F., et al. (2021). Neuroimaging mechanisms of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a double-blind randomized sham-controlled trial. Neural Regen. Res. 16, 707–713. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.295345

Zhang, F., Qin, Y., Xie, L., Zheng, C., Huang, X., and Zhang, M. (2019). High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training improves cognitive function and cortical metabolic ratios in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 126, 1081–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-02022-y

Zhao, J., Li, Z., Cong, Y., Zhang, J., Tan, M., Zhang, H., et al. (2017). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improves cognitive function of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Oncotarget 8, 33864–33871.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive function, meta-analysis

Citation: Xie Y, Li Y, Nie L, Zhang W, Ke Z and Ku Y (2021) Cognitive Enhancement of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment and Early Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:734046. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.734046

Received: 30 June 2021; Accepted: 23 August 2021;

Published: 10 September 2021.

Edited by:

Chencheng Zhang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaochen Zhang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaDandan Zhang, Shenzhen University, China

Copyright © 2021 Xie, Li, Nie, Zhang, Ke and Ku. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunxia Li, ZG9jdG9ybGl5dW54aWFAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Yixuan Ku, a3V5aXh1YW5AbWFpbC5zeXN1LmVkdS5jbg==

Ye Xie

Ye Xie Yunxia Li

Yunxia Li Lu Nie

Lu Nie Wanting Zhang

Wanting Zhang Zijun Ke

Zijun Ke Yixuan Ku

Yixuan Ku