- 1Guangxi Key Laboratory for Aquatic Genetic Breeding and Healthy Aquaculture, Guangxi Academy of Fishery Sciences, Nanning, China

- 2Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 3College of Animal Science and Technology, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

Precise regulation of angiogenesis is required for organ development, wound repair, and tumor progression. Here, we identified a novel gene, nxhl (New XingHuo light), that is conserved in vertebrates and that plays a crucial role in vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Bioinformatic analysis uncovered its essential roles in development based on co-expression with several key developmental genes. Knockdown of nxhl in zebrafish causes global and pericardial edema, loss of blood circulation, and vascular defects characterized by both reduced vascularization in intersegmental vessels and decreased sprouting in the caudal vein plexus. The nxhl gene also affects human endothelial cell behavior in vitro. We found that nxhl functions in part by targeting VE-PTP through interaction with NCL (nucleolin). Loss of ptprb (a VE-PTP ortholo) in zebrafish resulted in defects similar to nxhl knockdown. Moreover, nxhl deficiency attenuates tumor invasion and proteins (including VE-PTP and NCL) associated with angiogenesis and EMT. These findings illustrate that nxhl can regulate angiogenesis via a novel nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP axis, providing a new therapeutic target for modulating vascular formation and function, especially for cancer treatment.

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the process of new blood vessel formation, is orchestrated by various angiogenic factors. Angiogenesis plays critical roles in reproduction, organ development, and wound repair. Angiogenesis is closely related to various diseases, including a range of tumors and nonneoplastic diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (Handa et al., 2019), diabetic macular edema (Wells et al., 2015), rheumatoid arthritis (Smolen et al., 2020), and atherosclerosis (Souilhol et al., 2020). Judah Folkman has suggested that angiogenesis should be considered an “organizing principle” in biology (Folkman, 2007). This conceptualization shifts the focus of therapeutic strategies from tumor cell-centered to anti-angiogenesis centered (Grothey and Galanis, 2009). In the past several decades, anti-angiogenic therapeutics have focused on the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGFR signaling axis. Various inhibitors of this axis have been approved for solid cancers by the US Food and Drug Administration (Wilke et al., 2014). Over 3000 anti-angiogenic drugs have been registered in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer and ocular neovascular diseases (Ferrara and Adamis, 2016). However, in the clinical setting, simply blocking the existing VEGF signaling pathway or other angiogenic pathways appears to be less effective for advanced cases and often causes treatment resistance (Giantonio et al., 2007). New drugs targeting novel angiogenic pathways are clinically necessary and highly desirable.

We are particularly interested in the vascular endothelial protein tyrosine phosphatase (VE-PTP, known as PTPRB in zebrafish), which is indispensable during mouse blood vessel development (Baumer et al., 2006; Dominguez et al., 2007; Hayashi et al., 2013) owing to overactivation of Tie2 and increased vessel enlargement (Baumer et al., 2006; Dominguez et al., 2007; Winderlich et al., 2009). Evidence suggests that VE-PTP plays a crucial role in angiogenesis, integrity of endothelial cell (EC) adherens junctions, and vascular homeostasis (Nawroth et al., 2002; Baumer et al., 2006; Nottebaum et al., 2008; Monaghan-Benson and Burridge, 2013; Vestweber, 2015). VE-PTP binds to Tie2 and negatively controls Tie2-induced vascular remodeling and angiogenesis by dephosphorylation (Winderlich et al., 2009). Suppressing VE-PTP, either by genetic deletion or specific VE-PTP inhibitors, results in activation of the ability of Tie2 to regulate angiogenesis (Shen et al., 2014; Souma et al., 2018). Nucleolin (NCL) is a highly conserved gene that is broadly expressed in ECs (Christian et al., 2003; Fogal et al., 2009) and is enhanced on the surface of activated angiogenic ECs and many different types of cancer cells. Plasma membrane NCL (Christian et al., 2003; Hubing et al., 2007) and cell surface NCL regulate angiogenesis and tumorigenesis via interactions with various ligands such as VEGF (Christian et al., 2003), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Farin et al., 2011), endostatin (Koutsioumpa and Papadimitriou, 2014), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2; ErbB2 (Wolfson et al., 2016). Inhibition of cell surface NCL in ECs significantly suppresses EC migration and prevents capillary tubule formation (Huang et al., 2006). A variety of aptamers or antibodies targeting NCL are promising therapeutic agents and are under clinical investigation for cancer treatment (Romano et al., 2019). Both VE-PTP and NCL potentially function similarly in angiogenesis. Targeting the upstream genes that directly or indirectly interact with VE-PTP or NCL may be a promising strategy to overcome the limitations of current anti-VEGF agents.

We thus asked whether both VE-PTP and NCL are closely associated and how they are regulated in angiogenesis. We aimed to investigate this in a zebrafish model, as the zebrafish is an ideal model system for the study of vertebrate gene function, especially angiogenesis regulation, due to its vascular network formation and expression patterns of key genes being highly similar to those of humans and other vertebrates (Danninger and Gimona, 2000; Song et al., 2004). The virtually transparent embryos of this species, external development of the embryo, and the ability to produce various transgenic germ line fish as well as the ability to accelerate genetic studies by gene knockdown or overexpression make investigation of vertebrate gene function and vasculature manipulation in zebrafish feasible and cost-effective (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). Its conserved angiogenic signaling pathways make the zebrafish an ideal system for angiogenesis research and anti-angiogenic or anti-cancer drug screening (Lyons et al., 1998; Tran et al., 2007). In addition, knockdown of gene function by MOs (Morpholino Oligonucleotides) is the most familiar genetic approach employed to study genes of interest in zebrafish (Sugano and Neuhauss, 2013). By interfering with the mRNA transcripts, MOs are not affected by the genetic compensation response that occurs with the genome editing techniques such as TALENs or CRISPR-Cas9 (Rossi et al., 2015; El-Brolosy et al., 2019). Previous research has shown that genetic compensation is induced by deleterious mutations but not by gene MO knockdown (Rossi et al., 2015).

Herein we identified a novel gene, nxhl (New XingHuo light), that is conserved in vertebrates and is co-expressed with keystone genes for embryonic development. We employed a zebrafish model and the MO knockdown technique to investigate the function of nxhl. We found that loss of nxhl in zebrafish caused global and pericardial edema, loss of blood circulation, and vascular defects. The results indicated that nxhl functions in part by targeting VE-PTP through interaction with nucleolin (NCL). Loss of ptprb (a VE-PTP ortholog) in zebrafish phenocopies nxhl deficiency. Moreover, nxhl deficiency attenuates tumor invasion and proteins associated with angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). These findings illustrate that nxhl can regulate angiogenesis via the novel nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP axis, and thus the results provide a new therapeutic target for modulation of angiogenesis, especially for cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

RNAs Preparation and Sequencing (Golden Pompano Embryos)

For pooled transcriptome data, RNAs were extracted from the intestines, middle kidney, head kidney, muscle, heart, and eggs using an RNeasy Plus Mini kit (DP441, QIAGEN, China). The RNAs were pooled for library construction. For transcriptome analyses of embryo development, samples of the whole embryo at different development stages (from OSP to YAPS) were collected. The RNAs of each stage were also extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (DP441, QIAGEN, China). The development stages were accurately identified through continuous observation during fertilized egg development using a microscope. A photo of each stage was simultaneously taken during sample collection based on the shape of each embryo stage. The mRNA was enriched by Oligo (dT) and fragmented with fragmentation buffer. Only 200–700 bp fragments were selected for PCR amplification and sequencing in the fragment size selection step. The RNA-Seq libraries for all samples were prepared using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit (RS-122-2103) (Illumina, United States) following the manufacturer’s instructions and then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeqTM sequencing platform.

Gene Expression Quantification

Reads with more than 20% low-quality bases (quality < 20) were filtered out after removing the adapter and primer sequences. The clean reads were mapped to the golden pompano reference genome by TopHat v2.0.13 (Trapnell et al., 2012). The gene expression levels were calculated by Cufflinks v2.2. (Trapnell et al., 2012) using default parameters. Gene expression levels were normalized by reads per million per kilobase (FPKM). The genes that had expression values greater than 0.1 FPKM were considered as expressed genes. The genes were regarded as differentially expressed genes (DGEs) if the fold change (FC) was greater than 2 or smaller than 0.5 and the FDR was < 0.05. Furthermore, the genes were examined for enrichment of KEGG and GO terms using Fisher’s exact test.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

The WGCNA R package (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008) was used to analyze the co-expression gene network of the transcriptomic dataset of 19 embryonic stages with the parameters soft-power = 6 and minimum module size = 30. Genes expressed > 0.5 TPM in > 1% of the 57 samples (14,327 genes) were used as input. Genes with standard deviation/mean > 0.5 were removed, and a total of 10,998 genes were used to build the co-expression modules. The function hclust was used to produce a hierarchical clustering tree of genes with the parameter method = “average.” A soft power threshold of 6 was used to fit a scale-free topology. Adjacency and TOM (topological overlap measure) similarity matrices were generated based on the soft power threshold. Ten modules were identified through the cluster detection function cutreeDynamic in hierarchical clustering of the genes based on the TOM dissimilarity measure, and the minimum module size was set to 30. Function mergeCloseModules was used to merge highly correlated modules with similar expression profiles. Function signedKME was used to calculate the relationships between modules using the signed eigengene-based connectivity. Function corPvalueStudent was used to calculate the significance between the gene expression modules and trait via the Pearson method.

Zebrafish Care and Maintenance

Adult wild-type AB strain zebrafish were maintained at 28.5°C with a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle (Westerfield, 1993). Five to six pairs of zebrafish were set up for natural mating. On average, 200–300 embryos were generated. Embryos were maintained at 28.5°C in fish water (0.2% Instant Ocean Salt in deionized water). The embryos were washed and staged according to published references (Kimmel et al., 1995). The establishment and characterization of the (fli1a:EGFP) transgenic lines have been described elsewhere (Nasevicius and Ekker, 2000; Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). The zebrafish facility at SMOC (Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc.) is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International.

Zebrafish Microinjections

Gene Tools, LLC1 designed the morpholino (MO). Antisense MOs (GeneTools) were microinjected into fertilized one-cell stage embryos according to standard protocols (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). Translation-blocking (ATG-MO) and splice-blocking morpholinos of nxhl (zgc:113227, NM_001014319.2) and ptprb (NM_001316727.1), respectively, were designed. The standard control morpholino was used as a control MO (Gene Tools). The amounts of the MOs used for injection were as follows: control MO, ATG-MO, and splice-blocking-MO, 4 ng per embryo. The effectiveness of nxhl and ptprb knockdown was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). The morpholinos and primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Zebrafish Angiogenesis Studies and Image Acquisition

To evaluate angiogenesis development in zebrafish, fertilized one-cell fli1a-EGFP transgenic line embryos were injected with 4 ng nxhl-e1i1-MO, nxhl-ATG-MO, or control-MO, and ptprb-e4i4-MO, ptprb-ATG-MO, or control-MO. At 2 dpf (days post fertilization) the embryos were dechorionated and anesthetized with 0.016% MS-222 (tricaine methane sulfonate, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Zebrafish were then oriented on the lateral side (anterior, left; posterior, right; dorsal, top), and mounted with 3% methylcellulose in a depression slide for observation by fluorescence microscopy. The phenotypes of complete intersegmental vessels (ISVs), parachordal vessels (PAV), and caudal vein plexus (CVP) were analyzed. Embryos and larvae were analyzed with a Nikon SMZ 1500 Fluorescence microscope and subsequently photographed with digital cameras. A subset of images was adjusted for levels of brightness, contrast, hue, and saturation with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Adobe, San Jose, California) to optimize the visualization of the expression patterns. Quantitative image analyses were performed using image-based morphometric analysis (NIS-Elements D3.1, Japan) and ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States).2 Inverted fluorescent images were used for processing. Positive signals were defined by particle number using ImageJ. Ten animals for each treatment were quantified, and the total signal per animal was averaged.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 30 to 50 embryos per group in Trizol reagent (Cat. No. 11667157001, Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Cat. No. RR047A, Takara). Quantification of gene expression was performed in triplicate using Bio-rad iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Cat. No. 1708880, Bio-rad) with detection on the Realplex system (Eppendorf). Relative gene expression quantification was based on the comparative threshold cycle method (2–ΔΔCt) using ef1α or β-actin as an endogenous control gene. qPCR on HUVECs was performed using similar procedures. All of the primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA-Seq (Zebrafish Embryos)

Control MO-injected embryos and embryos injected with nxhl MO at 3 dpf were frozen for RNA-seq analysis. Three biological replicates of 30 embryos each were analyzed in each group. RNA was purified using an RNAqueous Total RNA isolation kit (Cat. No. AM1912, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries were prepared with a TruSeq RNA Library Prep kit v2 (Cat. No. RS-122-2001, Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were sequenced at the CCHMC Core Facility using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 device (Illumina) to generate 75 bp paired-end reads. The quality of the RNA-Seq reads was checked using Fastqc.3 All of the low-quality reads were trimmed using trimmomatic.4 The trimmed RNA-Seq reads were mapped and quantified to the latest zebrafish genome assembly GRCz10 for each sample at default thresholds using RSEM.5 The mRNA levels were identified using TopHat v2.0.9 and Cufflinks and normalized by the Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads (FPKM). Differential expression was analyzed by using CSBB.6 Criteria of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 and fold change < 0.5 or > 2.0 (<−1 or > 1 log2 ratio value, p-value < 0.05) were used to identify differentially expressed genes. Gene Ontology (GO) annotation, domain annotation, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation and enrichment were performed using ToppGene.7

Transwell Migration and Invasion Assays

To examine the function of nxhl (the homolog of Harbi1), siRNA targeting human Harbi1 gene (NM_173811.4) was designed and synthesized (see Supplementary Table 1). HUVEC cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, United States) were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Hyclone, United States) with 10% FBS (Gibco BRL. Co., Ltd.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sangon Biotech, China.) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Three experimental groups, untreated controls, Ctrl-siRNA, and nxhl-siRNA were set up, and 30 pmol nxhl-siRNA per well in the 24-well plates (Corning-costa, United States) was transferred using 9 μl Lipofectamine RNAi MAX Reagent (Cat. No. 13778-075, Invitrogen, United States). The cell migration and invasion capacity of nxhl in HUVECs cells were determined by transwell insert chambers (Corning, NY, United States) covered with or without 50 μl of Matrigel (1:3 dilution, BD, NJ, United States). Cells were then harvested and dissociated into a single-cell suspension. Then, 5 × 104 cells in serum-free medium were added to the upper chamber, and 600 μl of 20% FBS-containing medium was added to the lower chamber. The chambers were then incubated for 72 h (5% CO2, 37°C). Cells in the upper chamber were discarded, while cells in the lower chamber were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min. Cells that underwent migration or invasion were counted in triplicate in microscopic fields. The migration of nucleolin (NCL,NM_005381.3) was also examined by a similar protocol. All cancer cell lines used in this study, including HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC), A549 (non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC), and HCT116 (colon carcinoma, Colo) were kept in our labs and identified by the short tandem repeat (STR) method. The siRNA for NCL is listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Cell Proliferation Assay

The MTT assay was used to determine the proliferation of HCC cells. HCC cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were counted using Trypan blue and a hemocytometer. Approximately 1 × 105 HCC cells/well were seeded into 96-well plates. Three groups were set up in triplicate, an nxhl-siRNA group, a Ctrl-siRNA group, and an untreated control group. All cells were incubated for 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, and 48 h after being seeded with 50 μL MTT (Sigma Chemicals, MO) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, all cells were treated with MTT solvent for 20 min at room temperate. The supernatants were removed from the cells, and DMSO was added. The cell proliferation was recorded by measuring the optical density (OD) at 570 nm.

Colony Formation Assay

For this assay, 1 × 106cells/well were planted and cultured in 6-well plates. nxhl-siRNA, Ctrl-siRNA and untreated control groups were set up in triplicate. The cells were cultured for 2 weeks, and the culture medium was refreshed every 3 days. The colonies were fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 15 min. Colonies in each well were counted independently and photographed under a microscope.

Tube Formation Assay

The HUVECs’ culture conditions and experimental setup were identical to those of the transwell migration and invasion assays. Thirty picomoles of nxhl-siRNA or NCL-siRNA per well of 24-well plates (Corning Costa, United States) were transferred by using 9 μl Lipofectamine RNAi MAX Reagent (Cat. No. 13778-075, Invitrogen, United States). Matrigel (250 μl per well, BD Biosciences, United States) was added to the plates and cultured at 37°C for 30 min. Then, a suspension containing 5 × 104 HUVECs was added to each well and cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. A final concentration of 50 μM Calcein-AM (Cat. No. C8950, Solarbio, China) per well was added to the plates and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Six hours later, the tube formation was observed under a fluorescence microscope. The number of formed tubes represented the tube forming capability of HUVECs.

Comprehensive Identification of RNA-Binding Proteins by Mass Spectrometry

Zebrafish embryos (3 dpf) were collected, and a total of 2 × 107 cells were prepared and re-suspended in precooled PBS buffer followed by crosslinking with 3% formaldehyde for 30 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by incubation with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. After centrifugation at 1,000 RCF for 3 min, the pre-binding probes (100 pmol per 2 × 107 cells; for probes see Supplementary Table 1) were incubated with streptavidin beads for 30 min. The unbound probes were removed by washing three times. The beads with probes were incubated with the cell lysate and hybridized at 37°C with shaking overnight. All of the beads were washed three times with pre-warmed wash buffer for 5 min. A small aliquot (1/20 of the beads) of post-ChIRP beads was reserved for RNA extraction and qPCR analysis. Then, 100 μL of elution buffer (12.5 mM biotin, 7.5 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM EDTA, 0.15% SDS, 0.075% sarkosyl, 0.02% Na-Deoxycholate, and 20 U benzonase) was added, and the protein was eluted at 37°C for 1 h. The eluent was transferred to a fresh low-binding tube, and the beads were eluted again with 100 μL of elution buffer. The two eluents were combined, and reverse-crosslinking was performed at 95°C for 30 min. The proteins were precipitated with 0.1% SDC and 10% TCA by centrifugation at 4°C for 2 h. The pellets were then washed with precooled 80% acetone three times before the proteins were used for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Then, 5 μL peptides of each sample were collected and separated by a nano-UPLC liquid phase system (easy-nLC1200) before they were detected using an on-line mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive) at a resolution of 70,000. All of the original MS data were queried against the zebrafish protein database (UNIPROT_zebrafish_2016_09). Only those proteins with an FDR < 0.01 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. The identified proteins were then further examined using bioinformatics, including GO and KEGG pathway annotations.

Nxhl Protein Expression and Antibody Preparation

Briefly, the nxhl gene (zgc:113227, NM_001014319.2) was synthesized, and the expression plasmid pET-B2m-nxhl-His was constructed using seamless cloning technology. The plasmid was transferred into the Escherichia coli strain B21 (DH3) for protein expression, and the resulting protein was purified using an Ni-NTA chromatography column. The purified nxhl protein was used to immunize Japanese big-eared rabbits to produce the polyclonal antibody. The specificity of the polyclonal antibody was detected by anti-His Western blotting, and its immune action was verified by ELISA. We purified 6 mg of fusion protein (62.0 kDa) with 85% purity. After immunization in rabbits, an nxhl polyclonal antibody with a titer of 1:256,000 was obtained. The concentration of the nxhl antibody purified by Protein G affinity chromatography column was 10 mg/mL, and the purity was 90%. The obtained nxhl antibody was used to perform Western blotting assays.

Western Blotting Assays

Zebrafish tissues from the knockdown and control groups were treated with 1 mL of tissue lysate (50 mmol/L Tris, 0.1% SDS,150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 5 μg/mL aprotinin and 2 mmoL/L PMSF followed by lysis with protein lysate at 4°C for 30 min). All of the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 r/min at 4°C for 20 min, and the supernatant was removed to detect the protein concentration using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (CWBIO. Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE using a NuPAGE 4–12% gel (Life Technologies). Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose filter (BioRad, Hercules, CA, United States) and sealed at 4°C overnight with 5% dried skim milk. The membranes were incubated with diluted primary rabbit polyclonal ptprb (PA5-68309, Invitrogen, United States) (1:1,000), Nucleolin (ab50279, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1,000), Nucleolin phosphor T76 (ab168363, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1000), nxhl (Lab made, 1:1000) and ptprb (Lab made, 1:1,000), Slug (ab27568, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:500), N-cadherin (ab245117, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1,000), E-cadherin (20874-1-AP, Proteintech, China) (1:5,000), vimentin (10366-1-AP, Proteintech, China) (1:2,000), GAPDH (ab181602, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1,000) and β-actin (ab8226, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1,000) antibodies separately overnight at 4°C followed by washing with PBS at room temperature. The membranes were treated with goat-anti-rabbit, rabbit-anti-goat, or goat-anti-mouse IgG-HRP secondary antibody (1: 2,000, CWBiotech., Ltd., Beijing, China) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After washing with PBS, the membrane was soaked in enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (CW Biotech., Ltd., Beijing, China) to visualize the signals of protein bands according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The β-actin protein levels were used as an internal control.

RNA Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIP)

To examine the interactions of the nucleolin protein with nxhl mRNA and VE-PTP mRNA, RIP was conducted as follows: the constructed nxhl-pcDNA3.1 (pcDNA3.1 vector V79020, Invitrogen, United States) was transferred into 293T cells, and its overexpression was verified by qPCR. Then, 1 × 107 293T cells were suspended and lysed for 20 min with 1 ml RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) containing 1 μl of protease inhibitor (Beyotime, China). Twenty microliters of cell lysates were used as input. Magnetic beads were pretreated for RIP with an anti-rabbit IgG (Beyotime, China; negative control) isotype control and anti-nucleolin (ab50279, Abcam, United Kingdom) for 1 h at room temperature, and cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with the beads-antibody complexes at 4°C overnight. The retrieved RNA was isolated and purified by using the phenol-chloroform method and subjected to real-time qPCR and general reverse-transcription PCR for nxhl and VE-PTP analyses. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA Pull-Down Assay

To detect the interactions between VE-PTP mRNA and nucleolin protein in 293T cells and between ptprb mRNA and nucleolin protein in zebrafish tissues, probes for VE-PTP (human) and ptprb (zebrafish) were designed and synthesized. The probes are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Probes were labeled with 3 μg biotin and then heated at 95°C for 2 min followed by standing at room temperature for 30 min. Magnetic beads were washed and resuspended in 50 μl RIP buffer, and the biotinylated and denatured probes were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The nucleolin protein was extracted with 1 ml RIP buffer, sonicated, centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant (nucleolin protein) was retained. A magnetic separator was used to remove the liquid, and the protein solution was rinsed three times using RIP buffer. The protein solution was added to the magnetic bead-probe mixture, and RNase inhibitor was added to the lysate. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h and washed five times with 1 ml RIP buffer. Then, 2 × SDS loading buffer was added to the mixture, denatured at 95°C for 10 min, and used for subsequent Western blotting. The Western blotting was performed as described above. The antibody Nucleolin (ab50279, Abcam, United Kingdom) (1:1,000) was used in the detection of VE-PTP (human) and ptprb (zebrafish) in 293T cells and zebrafish tissue.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis and graphical representation of the data were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical evaluation was performed by using Student’s t-tests, ANOVA, or χ2 tests as appropriate. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical significance is indicated by ∗ or by p-value. An asterisk (∗) represents p < 0.05; ∗∗ indicates p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗ indicates p < 0.0001. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Results

Evolutionary Conservation of Nxhl in Vertebrates

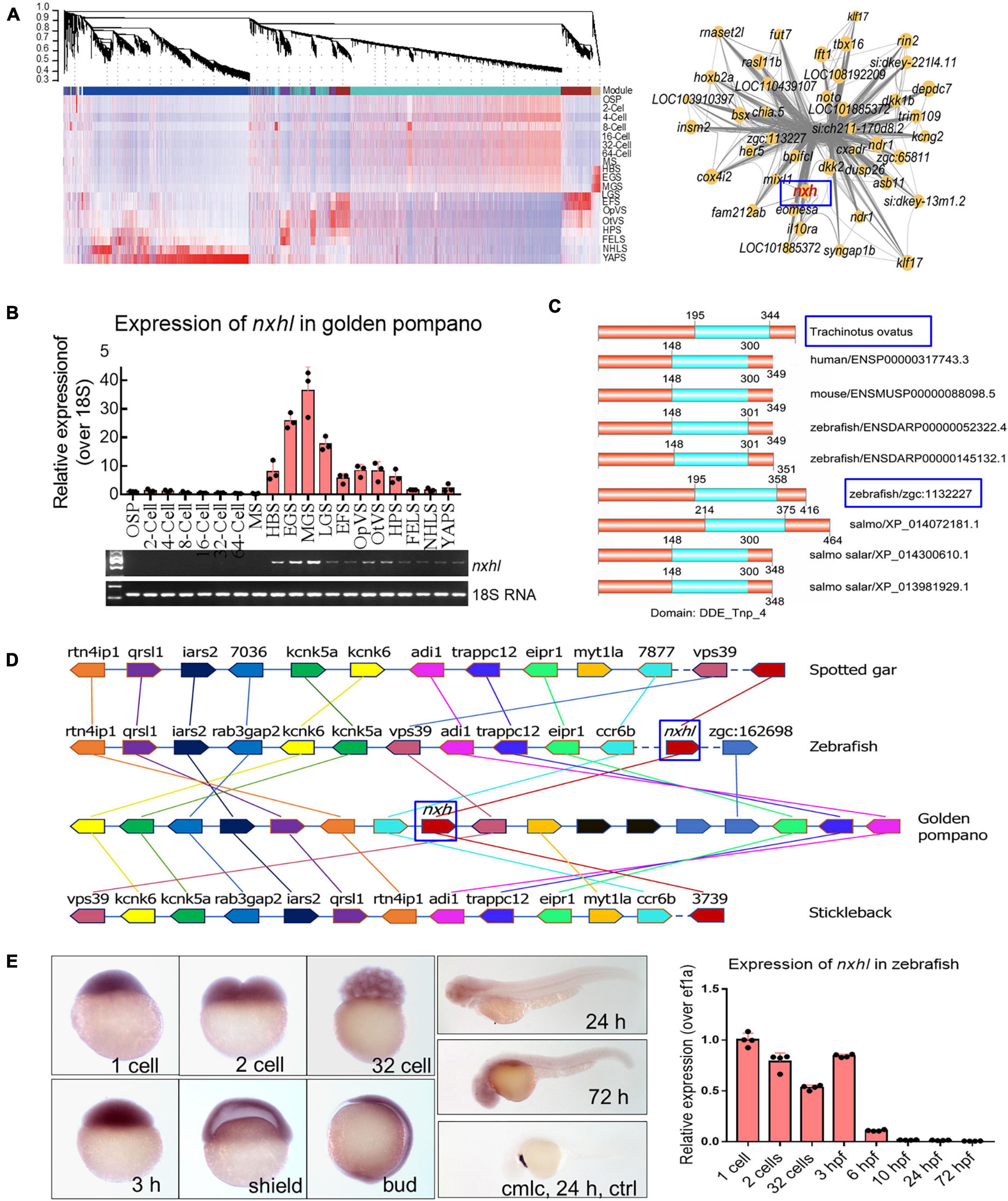

We analyzed the gene expression pattern in teleost golden pompano embryos based on the transcriptome data (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Tables 2–7) and found that all 57 samples covering 19 developmental stages were separated into two components (Supplementary Figure 1). The first 33 samples (from OSP to MGS) clustered into a clade, and the residual 24 samples (from LGS to YAPS) clustered into another clade. The genes in the first clade were non-redundant reserved hub genes and were clearly “silenced” compared with those in the second clade in which the gene levels showed an explosive increase. We also noticed that before LGS, a group of genes in three stages, HBS, EGS, and MGS, were highly expressed in the first clade (Supplementary Figure 1). We clustered these genes using the WGCNA R package (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and found that most of these clustered into the purple_module and were co-expressed in a close network, indicating regulatory roles of these genes (Figure 1A). EVM0008813 (designated New XingHuo light, nxhl; Figure 1B) was dominantly expressed in the HBS, EGS, and MGS stages; it was closely co-expressed with several key genes (Figure 1A) such as eomesa, dkk2, and mixl1 that play essential roles in embryonic development (Hart et al., 2002; Du et al., 2012; McGraw et al., 2014). We therefore propose that nxhl could be a crucial controller that regulates key steps in embryonic development. We found that nxhl contained two exons with two introns, and its expression (qPCR) in EGS, MGS, and LGS was highly matched to our sequencing data (FPKM, Figure 1B). We aligned the nxhl protein sequence with human, mouse, zebrafish, and salmon and found that this gene is conserved in vertebrate evolution (Figure 1C). We also found that only one gene, zgc:113227 (zebrafish nxhl), shared 54.7% similarity to nxhl at the amino acid level in zebrafish. Both nxhl and zebrafish nxhl have the same functional domain DDE_Tnp_4 as the other seven genes in different species (Figure 1C), suggesting that they are conserved and may have similar biological functions. We subsequently confirmed that nxhl is the only homolog gene in zebrafish by collinear analysis, indicating that the function of nxhl could be investigated by using its homolog in a zebrafish model (Figure 1D). We then checked the distribution of nxhl in zebrafish embryos by the whole-mount embryo in situ hybridization (WISH) method, and the results showed that nxhl was mainly distributed in 1-cell, 2-cell, 32-cell, and 3 hpf stages; very little was detected in other stages, suggesting that it is a typical maternal gene (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Evolutionary conservation of nxhl in vertebrate. (A) WGCNA analysis of embryonic development stages revealed gene-network modules enriched. HBS, EGS and MGS are classified into one group. OSP, oosperm; MS, morula stage; HBS, high blastula stage; EGS, early gastrula stage; MGS, middle gastrula stage; LGS, late gastrula stage; EFS, embryo formed stage; OpVS, optic vesicle stage; OtVS, otocyst vesicle stage; HPS, heart pulsation stage; FELS, formation of eye lens; NHLS, newly hatched larvae; YAPS, yolk absorption period. (B) Validation of expression level for nxhl by qPCR technology. 18s RNA was considered as internal marker. Gene structure of nxhl was showed at upper region. (C) Domains of nxhl and other homologous protein. The domain DDE_Tnp_4 was identified in SMART database (http://smart.embl.de/). (D) Micro-synteny analysis of nxh locus among spotted gar, zebrafish, gold pompano and stickleback. Two inversions and one insertion occurred in nxh locus region of golden pompano genomes. (E) The distribution of nxhl in zebrafish embryo by using whole-mount embryo in situ hybridization (WISH) and qPCR. Cmlc was used as positive control. Nxhl is mainly distributed in maternal developmental stages in zebrafish embryo.

Nxhl Affects Angiogenic Phenotypes in vivo

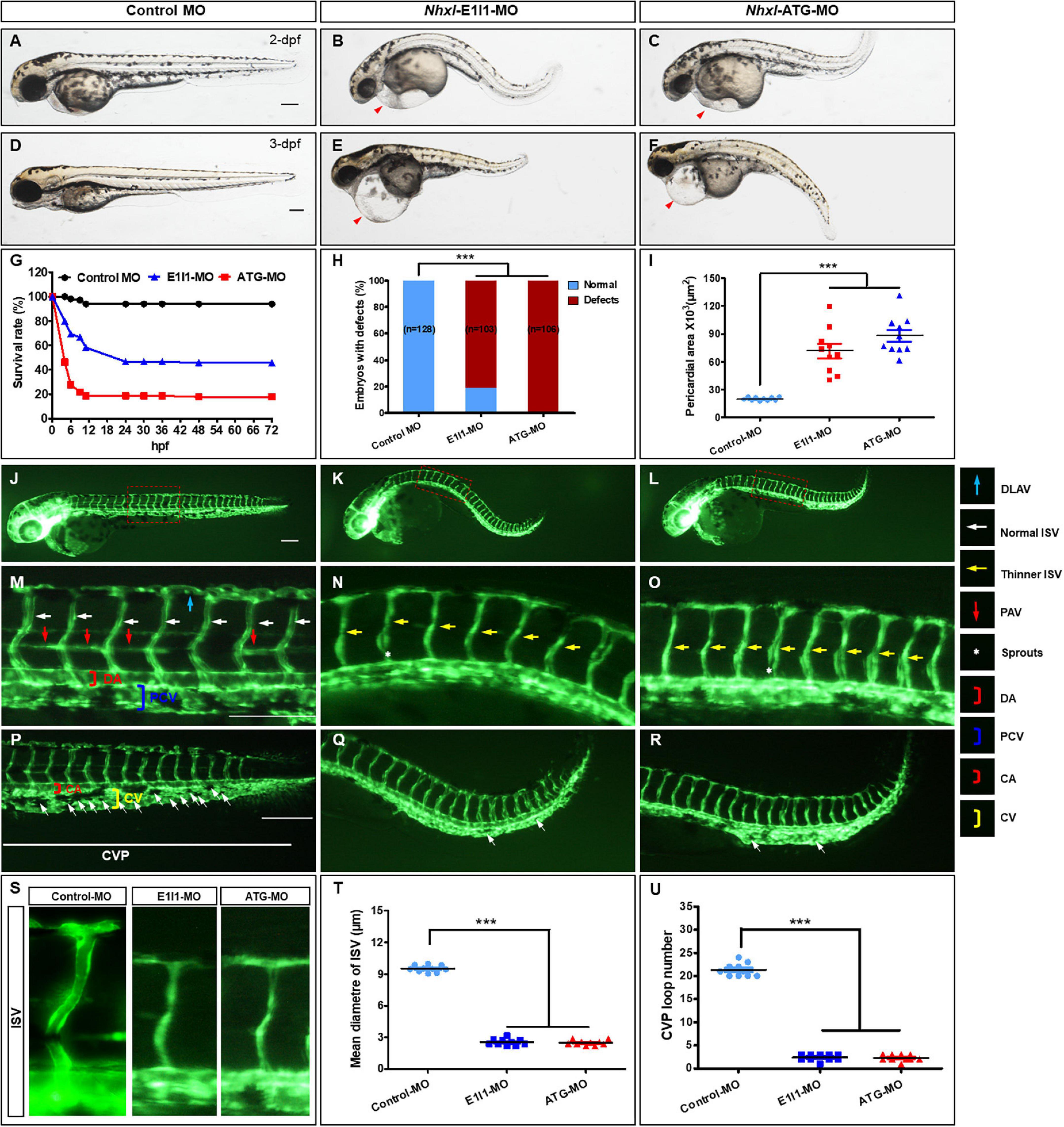

We next investigated the roles of nxhl. Firstly, we investigated whether loss of nxhl affected morphological development in zebrafish. The zebrafish nxhl gene was targeted in a specific morpholino antisense strategy to prevent the splicing of exon 1 (E1I1-MO). ATG-MO was used as a positive control. As designed, cleanly skipping exon 1 should frameshift the downstream sequence, leading to a premature termination codon in-frame that may trigger nonsense-mediated decay of the nxhl transcript (Supplementary Figure 2). We found that both the nxhl e1i1 and nxhl ATG morphants resulted in nearly identical phenotypes of pericardial edema, body axis bending, and circulation and caudal fin defects (Figures 2A–F and Supplementary Figures 2, 3 and Supplementary Videos 1, 2) with significantly lower survival rates (45.78%, n = 225 embryos in nxhl e1i1 MO; 17.68%, n = 198 embryos in nxhlATG MO) compared with controls (n = 218 embryos) (Figures 2G,H). The pericardial area of embryos at 3 days post fertilization compared with control fish is shown in Figure 2I. Both nxhl e1i1 and nxhl ATG morphants dramatically disrupted normal splicing of nxhl (Figures 2A–F), indicating high efficiency and specificity of the morpholino knockdown of nxhl together with the fact that the gel band in nxhl-MO was weaker than in the control MO (Supplementary Figure 2), confirming that the phenotype of nxhl knockdown was nxhl-specific rather than an off-target effect (Figures 2A–F). Consistent with this, nxhl morphants resulted in a high percentage of embryos with defects (81.55%, n = 103 embryos in nxhl e1i1 MO and 100%, n = 106 embryos in nxhl ATG MO) at 3-dpf (Figure 2H and Supplementary Figure 2). This confirmed that loss of nxhl caused the pericardial edema and circulation and caudal fin defects in the zebrafish. We then used the transgenic fluorescent Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 zebrafish as a model to investigate connections between the vascular system and these phenotypes. Compared with control MO, embryos injected with nxhl-MO presented a low number of incomplete ISVs and thinner ISVs (Figures 2N,O, yellow arrows) and ectopic sprouts (asterisk) of the dorsal aorta, and knockdown of nxhl prevented the formation of the parachordal vessels (PAV) compared with control embryos. Moreover, in control embryos the caudal vein plexus (CVP) formed honeycomb-like structures at the tail around 2 dpf (Figure 2P, white arrows), while nxhl knockdown resulted in specific defects in CVP formation (Figures 2J–S). Quantification of the mean diameter of ISVs and loop formation at the CVP showed significant decreases in nxhl e1i1 morphants (n = 10 embryos) at 2 dpf (Figures 2T,U). Our data indicate that nxhl plays a critical role in controlling PAV, ISV, and CVP formation and vascular integrity during angiogenesis; this is highly consistent with the observed heart and caudal fin phenotypes.

Figure 2. Nxhl regulates vascular development in vivo. (A–F) Gross morphology at 2-dpf and 3-dpf. Compared with control zebrafish, nxhl knock-down causes pericardial oedema (B,C,E,F, red arrowheads) and circulation defects. Heart beat and circulation in caudal vein (CV) is visible in the control fish, but is abnormal in nxhl morphants (Supplementary Videos 1, 2). (G) A time-course plot of percent survival in control vs. nxhl morphants for 3 days. (H) Shows the percentage of embryos with development defects. (I) Quantification of the pericardial area of embryos. Error bars, mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.0001 (n = 10; ANOVA). (J–R) Representative fluorescent images of Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 embryos at 2-dpf. (J,M) Image of trunk regions taken at 2-dpf, with the vascular structures visualized by eGFP fluorescence and labeled ISV and DLAV showed regular development in the embryo injected with control MO. The boxed regions are shown at higher magnification in the bottom panels. (K,L,N,O) Compared with control MO, embryos injected with nxhl-MO present a lower number of incomplete ISVs and thinner ISVs (N,O, yellow arrows) and ectopic sprouts (asterisk) of dorsal aorta. In control embryos, the parachordal vessels (PAV) form normally (M, red arrows). Compared with control, MO knock down nxhl prevents the parachordal vessels (PAV) formation, the precursor to the lymphatic system. In control embryos, caudal vein plexus (CVP) were formed honeycomb-like structures at the tail around 2-dpf (P, white arrows). In contrast, nxhl knock down resulted in specific defects in caudal vein plexus (CVP) formation (Q,R). (S–U) Quantification of the mean diameter ISVs (S,T) and loop formation at CVP (U) shows significantly decrease in nxhl morphants. Columns, mean; SEM (n = 10; ANOVA) ***p < 0.0001. DLAV, dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels; ISV, intersegmental vessel; DA, dorsal aorta; PCV, posterior cardinal vein; CVP, caudal vein plexus; CA, caudal artery; CV, caudal vein; dpf, days post fertilization. Scale bar, 100 μm.

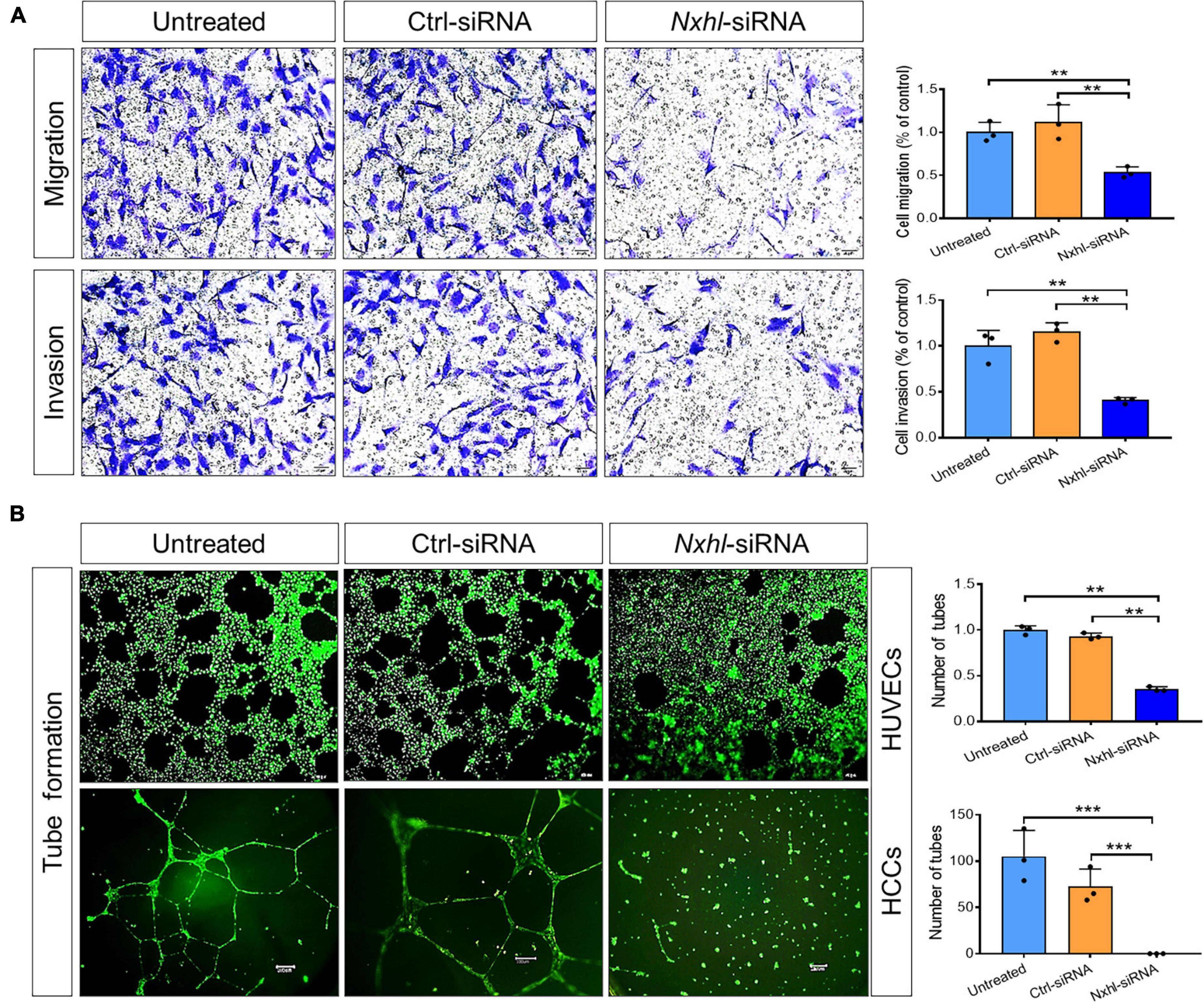

Nxhl Affects Angiogenic Phenotypes in vitro

Next, we examined the angiogenic functions of nxhl in vitro to find out whether the human homolog of nxhl plays a role in angiogenesis. As ECs line the inner lumen of vessels and are the elements upon which blood vessels are formed, we speculated that nxhl may affect angiogenesis via ECs. This was supported by significant enrichment of the genes involved in blood vessel morphogenesis upon nxhl depletion (Supplementary Table 2). To examine whether nxhl may function via ECs, we next silenced nxhl in HUVECs using a small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting nxhl. Silence of nxhl (about 70% knockdown efficiency, Supplementary Figure 4) significantly inhibited tube formation and cell migration in comparison with controls. Furthermore, the invasion abilities in nxhl–defective cells were significantly inhibited compared with controls (Figure 3). This highlights the anti-angiogenesis function of nxhl. We considered that nxhl likely mediates angiogenic behavior via ECs.

Figure 3. Nxhl affects angiogenic phenotypes in vitro. (A) Silence of nxhl (homolog of Harbi1) gene suppresses HUVEC cell migration and invasion. Representative images of migrated and invasive cells stained with crystal violet and inhibition of migration in nxhl-siRNA treated HUVEC cells. The migration and invasive potential of HUVECs treated with nxhl-siRNA was determined using transwell chambers as described in the “Materials and methods” section. (B) Silence of nxhl gene suppresses HUVEC and HCC cell tube formation abilities. Representative images of tube formation in nxhl-siRNA treated HUVEC cells and inhibition of tube formation in vitro (up row). Images were taken 6 h after addition of the supernatant. Tube networks were quantified using the Image J software and expressed as branches. Scale bars, 50 μm (middle row). Representative images of tube formation in nxhl-siRNA treated HCC cells (down row). Scale bars, 100 μm. Images were taken 24 h after addition of the supernatant. Tube networks were quantified using the Image J software and expressed as branches. The data represent as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001 represents statistically significant.

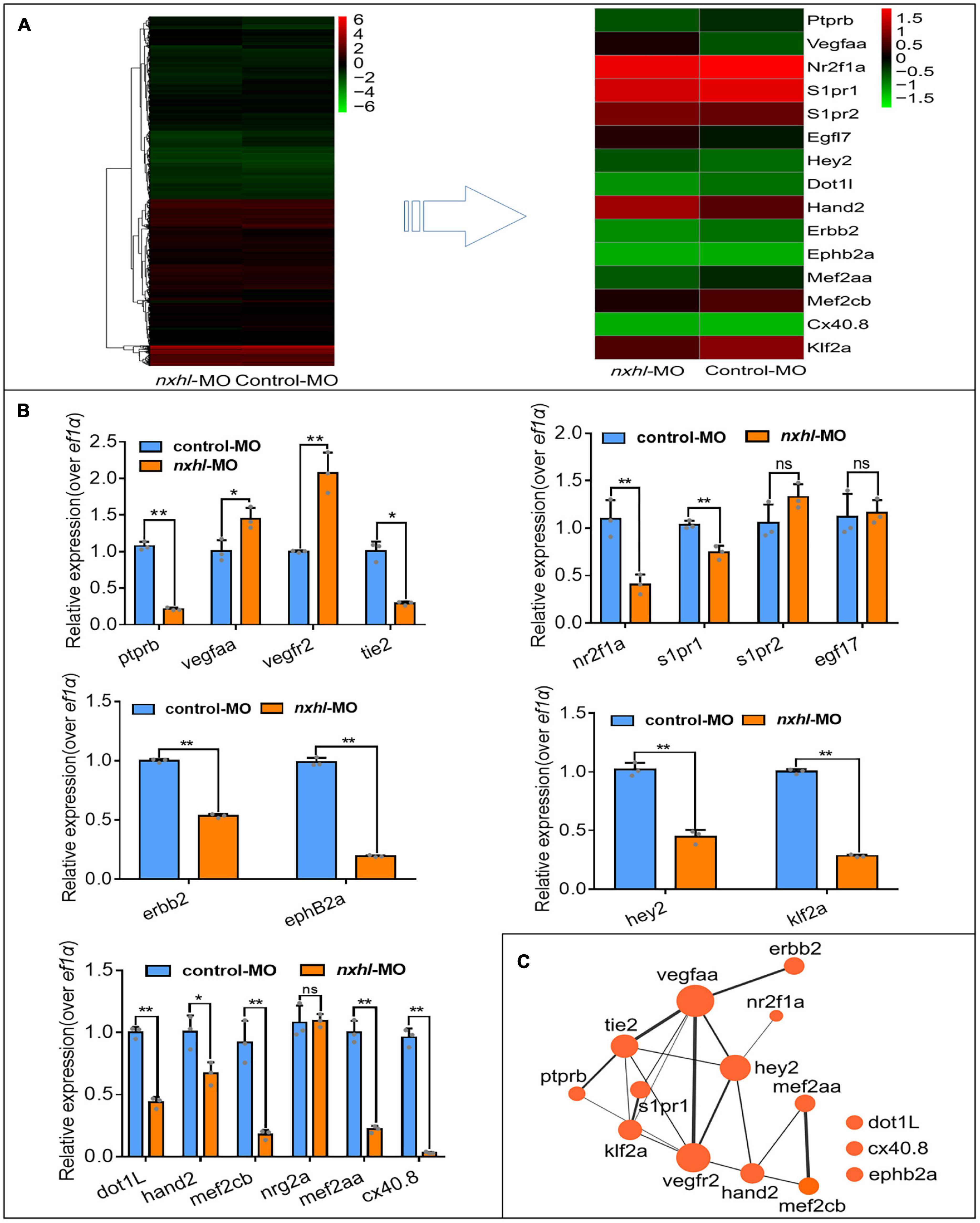

Nxhl Regulates Ptprb Expression and Angiogenic Networks

To investigate how nxhl mediates angiogenesis, we first examined transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) data from MO zebrafish. We found that loss of nxhl greatly altered the transcriptome, with 1955 downregulated and 698 upregulated genes (Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 2). The KEGG pathways associated with angiogenesis were significantly enriched in the nxhl-silenced group (Supplementary Figure 6 and Supplementary Tables 2–8). We speculated that expression levels of genes linked to angiogenesis may also be significantly altered. We then screened and examined the expression of 18 genes previously documented to be closely related to heart defects and/or angiogenesis (Carra et al., 2012; Hinits et al., 2012; Ruiz-Herguido et al., 2012; Boselli et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2016). Consistent with the RNA-seq data, we found that expression levels of 13 of these genes (ptprb, tie2, nr2f1a, s1pr1, hey2, dot1L, hand2, erbb2, klf2a, mef2cb, mef2aa, ephB2a, and cx40.8) were significantly decreased, whereas two genes (vegfaa and vegfr2) were sharply increased. S1pr2, egfl7, and nrg2a remained unchanged (Figures 4A,B). The arterial marker ephB2a and venous marker erbb2 were decreased in nxhl morphants compared with the wild-type (Figure 4B). Normally, the increases of vegfaa and vegfr2 are linked to enhancement of the vascular system (Koenig et al., 2016; Toselli et al., 2019). However, in our study the expression levels of both genes were increased, while others were decreased when nxhl was silenced. We speculated that this was a consequence of negative feedback regulation to avoid an excessive decrease in the vascular system. As previously reported, ptprb, tie2, nr2f1a, s1pr1, vegfaa, and vegfr2 normally contribute to vascular development, and deletion of each leads to defects in the vascular system during embryonic development (Winderlich et al., 2009; Mendelson et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Koenig et al., 2016; Toselli et al., 2019); loss of dot1L, hand2, erbb2, mef2cb, mef2aa, ephB2a, or cx40.8 always results in defects in angiogenesis or heart development (Gerhart et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Lazic and Scott, 2011; Nguyen et al., 2011; Hinits et al., 2012; Gemel et al., 2014; Schindler et al., 2014; Medrano and Naya, 2017). Hey2 and klf2a have been implicated in the regulation of both angiogenesis and heart development (Vermot et al., 2009; Gibb et al., 2018). Based on these results, we built a schematic diagram of the network, as shown in Figure 4C. This network demonstrates that silencing of nxhl does downregulate the key genes that are essential for heart and/or vascular development. The expression profiles of these genes can explain the nxhl deficiency-induced phenotypes. Notably, we found that ptprb, which plays essential roles in angiogenesis, was the most downregulated gene upon nxhl silencing (blue box in Figure 4B), indicating that it might be the target of nxhl regulation. Thus, we investigated whether ptprb has angiogenic regulatory functions similar to those of nxhl.

Figure 4. Nxhl modulates ptprb expression and angiogenic networks. (A) Heatmap of the 15 selected genes from zebrafishes after injection of 4 ng nxhle1i1 MO at 3-dpf examined by RNA-seq. (B) Expression of genes associated with angiogenesis and/or heart development post injection of nxhle1i1 MO 3-dpf using qPCR. The data above represent as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Ns, non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 represents statistically significant. (C) Networks of the genes previously reported to be associated with angiogenesis and heart development. Cytoscope V3.6.1 was used to build this network.

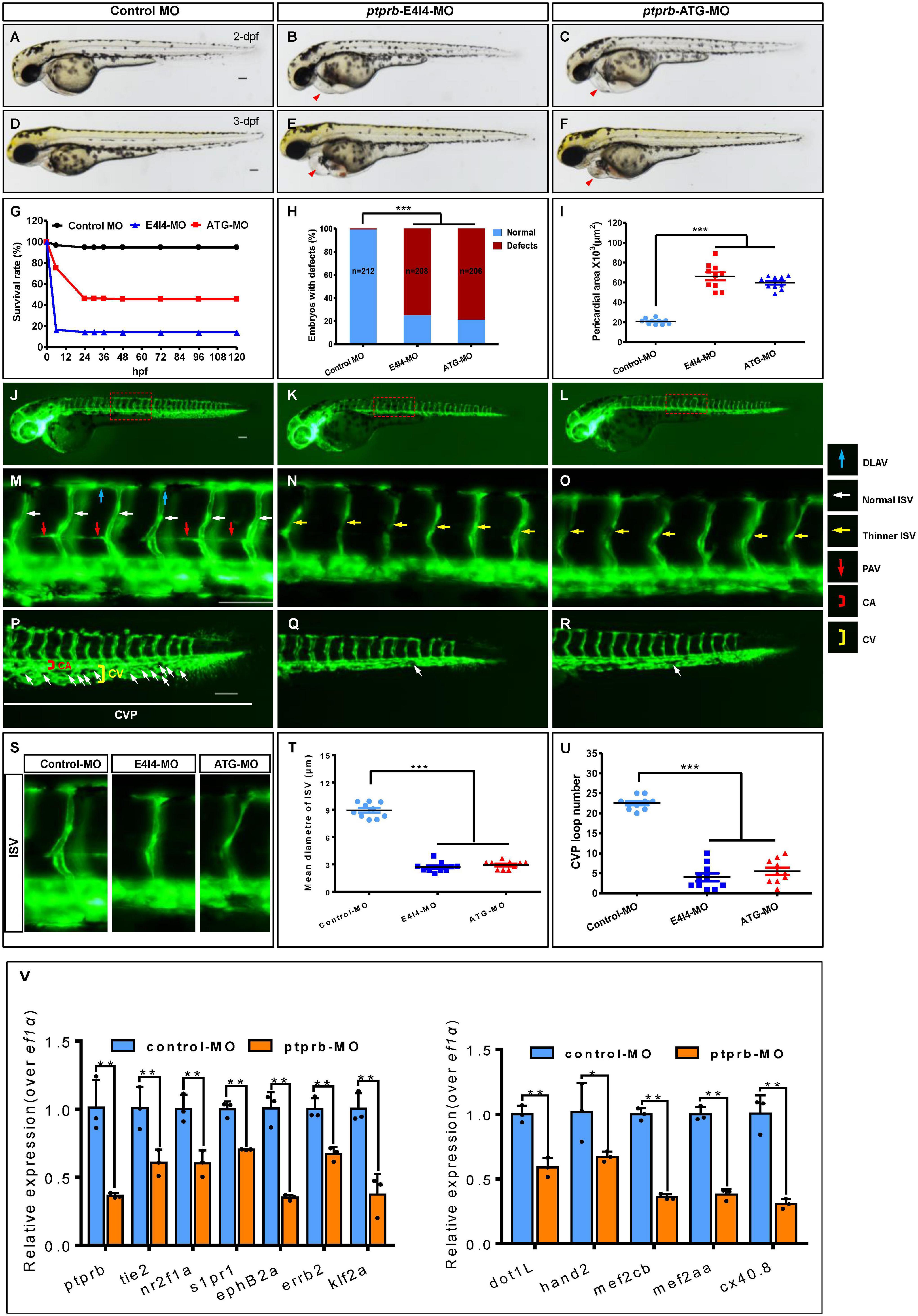

Loss of Ptprb Phenocopies Nxhl Deficiency

As described above, we noted that ptprb was the most downregulated gene and was closely linked to both vascular integrity and angiogenesis (Dominguez et al., 2007; Dejana et al., 2009; Mellberg et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2013; Braun et al., 2019; Juettner et al., 2019). To test whether there was a positive connection between nxhl and ptprb, we silenced ptprb in zebrafish (Supplementary Figure 7 and Supplementary Table 1). The zebrafish ptprb gene was targeted using a specific morpholino antisense strategy to prevent the splicing of exon 4 (E4I4-MO). ATG-MO was used as the positive control. Cleanly skipping exon 4 should frameshift the downstream sequence, leading to a premature termination codon in-frame and triggering nonsense-mediated decay of the ptprb transcript (Supplementary Figure 7A). We found that both ptprb e4i4 and ptprbATG morphants resulted in slight pericardial edema, shortened body axis, and circulation and caudal fin defects (Figures 5A–F and Supplementary Figure 7) with significantly lower survival rate (Figures 5G,H) and smaller pericardial area of embryos (Figure 5I) at 3 dpf compared with control fish. Both ptprb morphants dramatically disrupted normal splicing of ptprb (Figures 5A–F) and decreased the survival rate but did not change nxhl expression, indicating high efficiency and specificity of the morpholino knockdown of ptprb, together with the fact that the gel band in ptprb-MO was obscure and degraded compared with the control MO. This confirmed that the phenotype of the ptprb knockdown was nxhl-specific rather than an off-target effect (Figures 5A–F and Supplementary Figure 7A). Consistent with this, Ptprb morphants also resulted in a high percentage of embryos with defects at 3 dpf (75.48%, n = 208 embryos in the ptprb MO and 0.94%, n = 212 embryos in controls) (Figure 5H). Moreover, heartbeat and circulation in the CV were visible in the control fish (Supplementary Videos 3, 4) but were abnormal in ptprb-MO-injected fish (Supplementary Videos 5–8). This confirmed that loss of ptprb caused the pericardial edema and circulation and caudal fin defects in the zebrafish. Compared with control MO, embryos injected with ptprb-MO presented thinner ISVs (Figures 5N,O, yellow arrows), and knockdown of ptprb prevented formation of the parachordal vessels (PAV) compared with control embryos. Furthermore, in control embryos the caudal vein plexus (CVP) formed honeycomb-like structures at the tail around 2 dpf (Figure 5P, white arrows), while ptprb knockdown resulted in specific defects in caudal vein plexus (CVP) formation (Figures 5J–R). Quantification of the mean diameter of ISVs (Figures 5S–T) and loop formation at CVP (Figure 5U) showed a significant decrease in ptprb morphants at 2 dpf (Figures 5T,U). These data are consistent with previous reports (Carra et al., 2012) and strongly suggest that loss of ptprb phenocopies nxhl deficiency. Moreover, we found that most of the 15 genes in the ptprb-knockdown experiment presented an expression profile similar to that caused by nxhl knockdown, except for vegfaa and vegfr2 (Figure 5V). To this end, we logically concluded that ptprb and nxhl act in the same signaling pathway.

Figure 5. Loss of ptprb phenocopies nxhl deficiency. (A–F) Gross morphology at 2- and 3-dpf. Compared with control zebrafish, ptprb knock-down causes pericardial oedema (B,C,E,F, red arrowheads) and circulation defects. Heart beat and circulation in caudal vein (CV) is visible in the control fish, but is abnormal in ptprb morphants (Supplementary Videos 3–8). (G) A time-course plot of percent survival in control vs. ptprb morphants for 3 days. (H) shows the percentage of embryos with development defects. (I) Quantification of the pericardial area of embryos. Error bars, mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.0001 (n = 10; ANOVA). (J–R) Representative fluorescent images of Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 embryos at 2-dpf. (J,M) Image of trunk regions taken at 2-dpf, with the vascular structures visualized by eGFP fluorescence and labeled ISV and DLAV showed regular development in the embryo injected with control MO. The boxed regions are shown at higher magnification in the bottom panels. (K,L,N,O) Compared with control MO, embryos injected with ptprb-MO present thinner ISVs (N,O, yellow arrows). In control embryos, the parachordal vessels (PAV) form normally (M, red arrows). Compared with control, MO knock down ptprb prevents the parachordal vessels (PAV) formation, the precursor to the lymphatic system. In control embryos, caudal vein plexus (CVP) were formed honeycomb-like structures at the tail around 2-dpf (P, white arrows). In contrast, ptprb knock down resulted in specific defects in caudal vein plexus (CVP) formation (Q,R). (S–U) Quantification of the mean diameter ISVs (S,T) and loop formation at CVP (U) shows significantly decrease in ptprb morphants. Columns, mean; SEM (n = 10; ANOVA) ***p < 0.0001. DLAV, dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels; ISV, intersegmental vessel; CVP, caudal vein plexus; CA, caudal artery; CV, caudal vein; dpf, days post fertilization. Scale bar, 100 μm. (V) Expression of genes associated with angiogenesis (left) and heart development (right) post injection of ptprb MO 2-dpf using qPCR. The data represent as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 represents statistically significant.

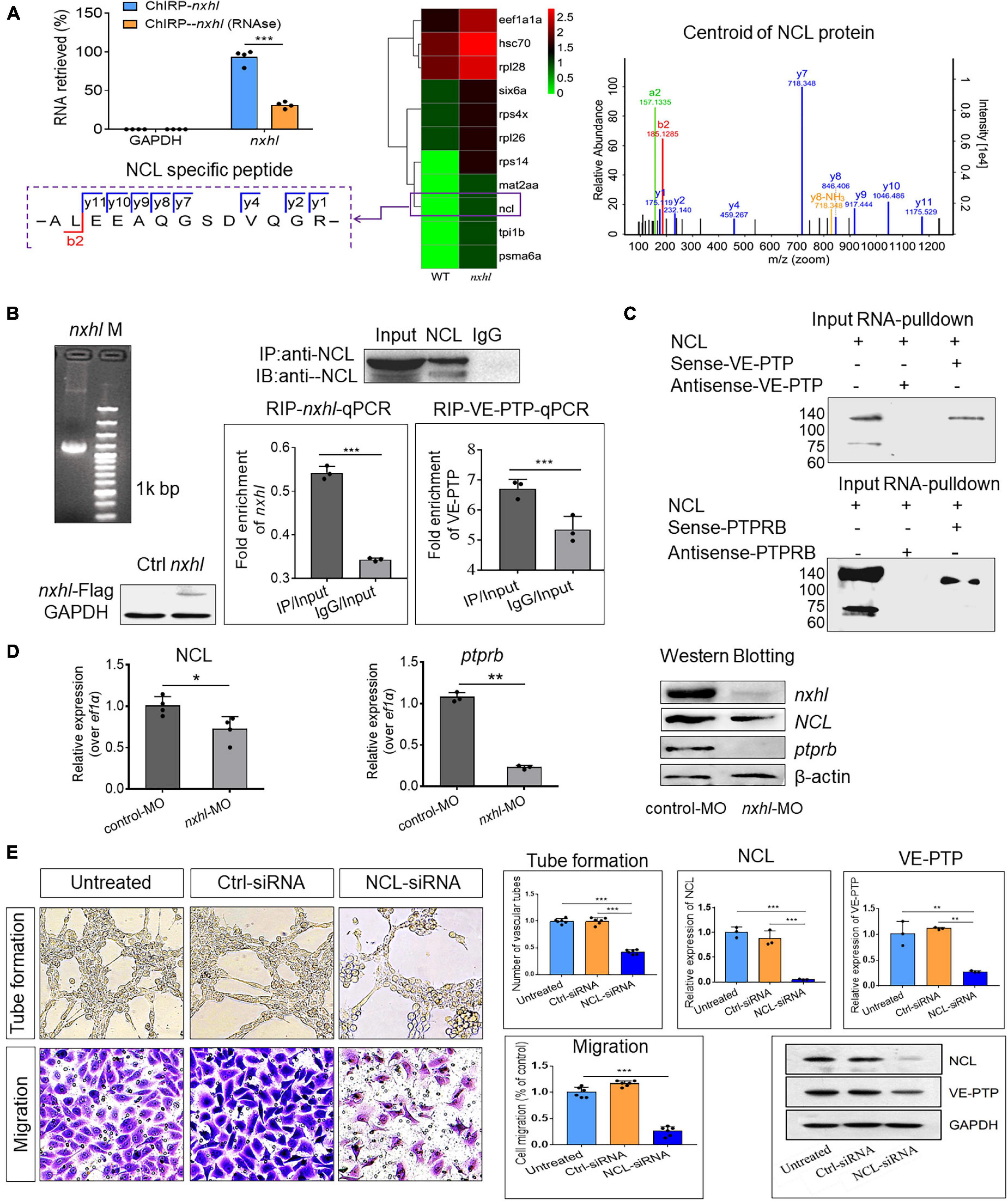

Nxhl Regulates Ptprb Through Interactions With Nucleolin

As shown in Figure 4, expression levels of 15 genes in the network were significantly altered in nxhl morphants. We supposed that these genes may be part of a regulatory network. This network presents connections between most of these genes, suggesting a cooperative regulation mechanism in heart and vascular development. Considering that ptprb was sharply downregulated by nxhl depletion and that loss of ptprb phenocopies nxhl deficiency, we next examined whether nxhl directly interacted with ptprb. Thus, we designed nxhl probes and conducted a chromatin isolation by RNA purification-mass spectrometer (ChIRP-MS) experiment in zebrafish to identify proteins binding to nxhl. Eleven proteins with a greater than twofold change were discovered (Figure 6A). Unexpectedly, ptprb was not found among these proteins (Figure 6A). This suggests that proteins other than ptprb may interact with nxhl. We next focused on proteins that were associated with the vascular system. NCL (Figure 6A) aroused our interest because of its molecular conservation and important functions in angiogenesis (Huang et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2017). Previous research has shown that loss of NCL in zebrafish causes edema and body axis bending (Monte et al., 2013) as well as suppression of adhesion, proliferation, and migration of HUVECs (Birmpas et al., 2012). These phenotypes are identical to the phenotypes caused by nxhl depletion, suggesting that NCL may be associated with nxhl. To ascertain whether nxhl interacts with NCL, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) using NCL as the bait protein in 293T cells (Supplementary Figures 8–10) and then detected the nxhl RNA using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). We found that nxhl RNA was significantly higher than that in an IgG control in the RNA pulled down by the NCL protein (Figure 6B), which was confirmed to be nxhl messenger RNA (mRNA) on reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification and RNA-seq. This indicates that the NCL protein reversely interacts with nxhl RNA. Therefore, these experiments indicated that nxhl RNA and NCL protein interact physically. However, no evidence was found regarding the interaction between nxhl and ptprb. We considered whether NCL might interact with ptprb, thus bridging nxhl and ptprb. Such a scenario has never been previously proposed or documented. However, one report showed that VEGF interacts with NCL (Watanabe et al., 2010). As nxhl acts similarly to VEGF in angiogenesis, we then supposed that NCL might also interact with ptprb or its human homolog VE-PTP. To test this hypothesis, we detected VE-PTP mRNA using the same RNA pulled down by the NCL protein, and we found that VE-PTP mRNA was significantly higher than that in the IgG control. The pulled-down RNA was amplified, and RNA-seq confirmed that it was VE-PTP mRNA. This confirmed that the NCL protein could also physically interact with VE-PTP mRNA (Figure 6B). We next verified this interaction in 293T cells using the VE-PTP RNA pull-down experiment in reverse; the results of Western blotting against the NCL protein supported the existence of an interaction between VE-PTP and NCL (Figure 6C). However, whether this interaction occurred between NCL and ptprb in zebrafish remained unclear. Therefore, we next designed a zebrafish ptprb gene-specific probe to pull down the proteins that interacted with ptprb in zebrafish. We found that the NCL protein binds strongly with ptprb (Figure 6C). This result indicates that the NCL protein interacts not only with VEP-PTP in 293T cells but also with ptprb in zebrafish.

Figure 6. Nxhl regulates VE-PTP (ptprb) through interactions with NCL. (A) ChIRP-MS identification of nxhl RNA binding proteins using zebrafish tissues. qPCR identification of nxhl RNA in the eluted RNAs. Graph shows more than 90% nxhl RNA was retrieved, and no GAPDH was detected. Heat map shows major proteins are enriched and significantly (change fold > 2 and p < 0.05) retrieved by nxhl and control probes, analyzed by LC/MS-MS. NCL protein (purple boxed) was selected as candidate for follow-up study. The Centroid of NCL protein shows that NCL protein is pulled down and identified by LC/MS-MS. The specific peptide identifies NCL protein. (B) The interaction between nxhl, VE-PTP mRNA and NCL protein by RIP-qPCR assay. The mRNA expression of nxhl was determined by qPCR and Western blotting against Flag antibody and used to identify the successful expression of pcDNA3.1- Flag-nxhl plasmid in 293T cells. Bars show the interaction between nxhl mRNA and NCL protein. The interaction between VE-PTP mRNA and NCL protein is shown too, and qPCR shows the detection for VE-PTP mRNA expression in the NCL-pulled down RNA. (C) The interaction between nxhl, VE-PTP mRNA and NCL protein by pull down assay. Gels show the interaction between VE-PTP mRNA and NCL protein. Western blotting was performed to detect NCL protein in the VE-PTP-biotin probe -pulled down proteins in 293T cells. The interaction between ptprb mRNA and NCL protein is shown too. (D) Loss of nxhl affects the expression of NCL at both mRNA and protein levels. The mRNA expression of NCL and ptprb were determined by qPCR. The total NCL protein, total nxhl and ptprb protein in zebrafish tissues from knock-down group and control were detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies (details see Materials and methods). β-actin was used as internal control. (E) Silence of NCL inhibits angiogenesis and expression of VE-PTP. The tube formation and cell migration potential of HUVECs treated with NCL-siRNA was determined by using transwell chambers as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Scale bars, 20 μm. Representative images of cells stained in NCL-siRNA treated HUVEC cells. The expression of NCL and VE-PTP was quantified by qPCR. Protein levels of NCL and VE-PTP were examined by using Western blotting post silence of NCL. GAPDH antibody was used as internal control. The data represent as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001 represents statistically significant.

Up to this point, we had validated that nxhl and NCL, and NCL and VEP-PTP (ptprb) interact physically. We also found that NCL was significantly downregulated at both mRNA and protein levels. We then investigated the expression of the downstream gene ptprb and found that loss of nxhl also decreased ptprb at both mRNA and protein levels (Figure 6D). Next, we investigated whether NCL regulates ptprb (VE-PTP). We thus examined the functions of NCL in angiogenesis and expression of VE-PTP by silencing of NCL in HUVECs. As shown in Figure 6E, silencing NCL significantly inhibited not only tube formation but also the cell migration of HUVECs in comparison with the controls. Notably, silencing of NCL greatly decreased the expression of VE-PTP at both mRNA and protein levels, suggesting that NCL not only interacts with VE-PTP but also regulates its expression. This highlights a regulatory role of NCL in VE-PTP expression and shows that a nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb) signaling pathway is logical and reasonable in angiogenesis. These results suggest that silencing of nxhl leads to angiogenesis defects owing to the downregulation of both NCL and ptprb via the interactions of nxhl–NCL and NCL–ptprb, which consequently mediate the angiogenesis-linked landmark gene network.

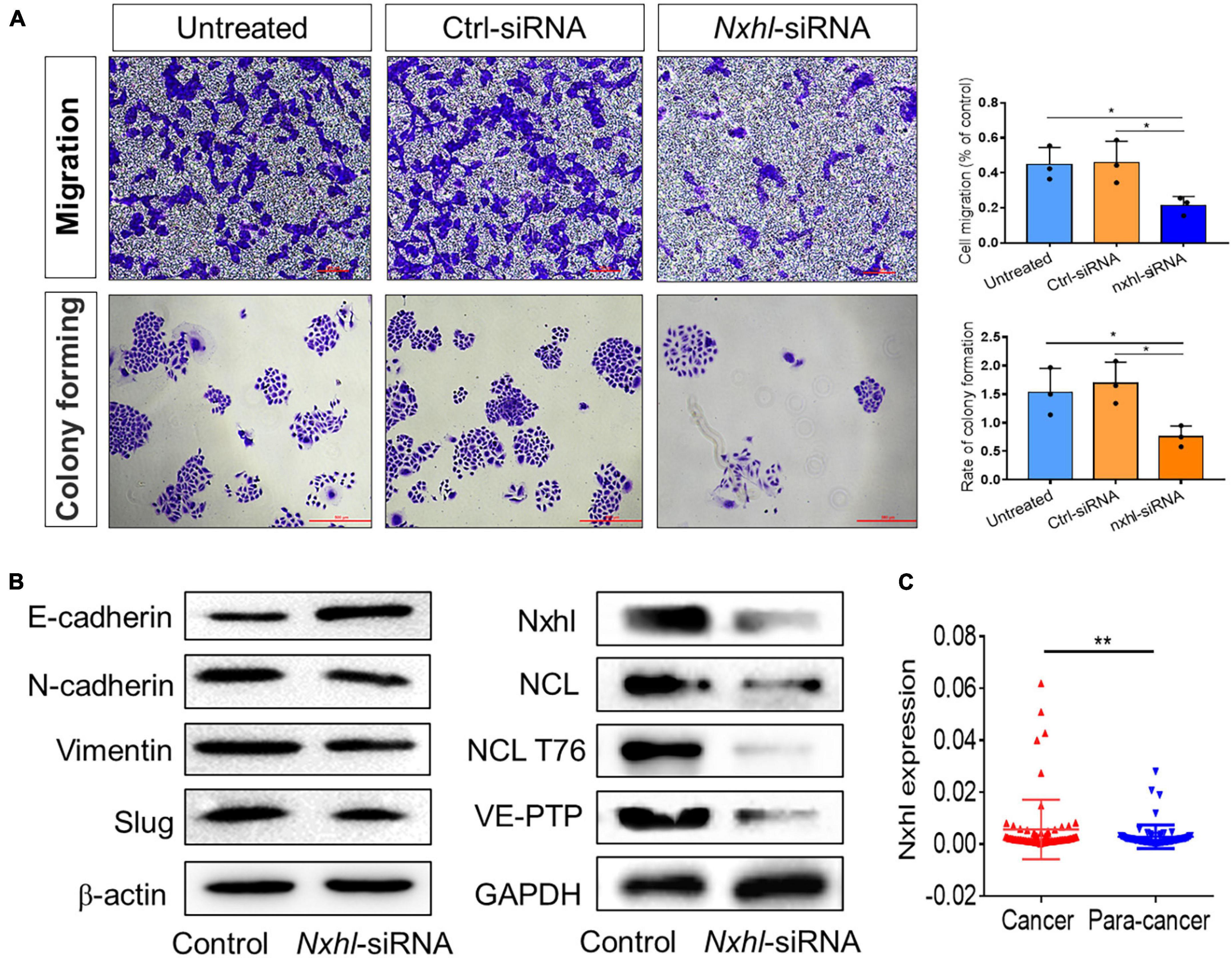

Nxhl Attenuates Tumor Invasion and Proteins Associated With Angiogenesis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

Because targeting angiogenesis has great potential in anti-tumor or anti-cancer therapy (Castet et al., 2019; Qin et al., 2019), we next investigated whether this anti-angiogenesis function affects the angiogenesis of cancer cells. HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC), A549 (non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC), and HCT116 (colon carcinoma, Colo) cells were transferred with nxhl-siRNA, and their supernatants were subsequently incubated with HUVECs. We observed that the abilities of tube formation in all cancer cells were significantly inhibited compared with controls (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figures 11B,C), suggesting that silencing of nxhl suppresses angiogenesis in cancer cells. We further silenced nxhl in HepG2 cell lines and found that loss of nxhl not only significantly inhibited the proliferation, migration, and colony formation of HCC cells but also suppressed the expression of EMT marker genes, suggesting that silencing of nxhl inhibits the EMT process of cancer cells (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure 11C). Moreover, silence of nxhl also inhibited NCL, NCL T76, and VE-PTP (ptprb) in cancer cells, identical to the signaling pathway induced by its homolog nxhl (Figure 7B). We then predicted whether nxhl is linked to HCC progression based on data in the cancer genome atlas (TCGA). We found that expression of nxhl in HCC tissues was significantly higher than that in normal tissues (Supplementary Figure 11D). We next tested this in tissue samples from 72 patients with HCC using qRT-PCR and found that the clinical test results were consistent with the TCGA predictions (Figure 7C and Supplementary Figure 11D). This function of nxhl has never been reported in cancer studies (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2004; Sinzelle et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2012). Our data indicate that nxhl has a role in the angiogenesis process via ECs and is a potential anti-cancer therapeutic target.

Figure 7. Nxhl attenuates tumor invasion and proteins associated with angiogenesis and EMT. (A) Silence of nxhl (homolog of Harbi1) inhibits migration and EMT of HCC cells. Representative images of migrated cells stained with crystal violet and inhibition of migration in nxhl-siRNA treated HepG2 cell (up row). Representative images of colony formation cells stained with crystal violet and inhibition of colony forming in nxhl-siRNA treated HepG2 cell (down row). (B) Silence of nxhl inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HepG2 cells. Four EMT marker proteins, NCL, NCL T76 and VE-PTP were detected using Western blotting method in control and siRNA-treated HepG2 cells. (C) nxhl (Harbi1) expression in 72 HCC tissues and para-cancer tissues. qPCR was used to determine the human homolog of nxhl (Harbi1) expression levels. The data above represent as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 represents statistically significant.

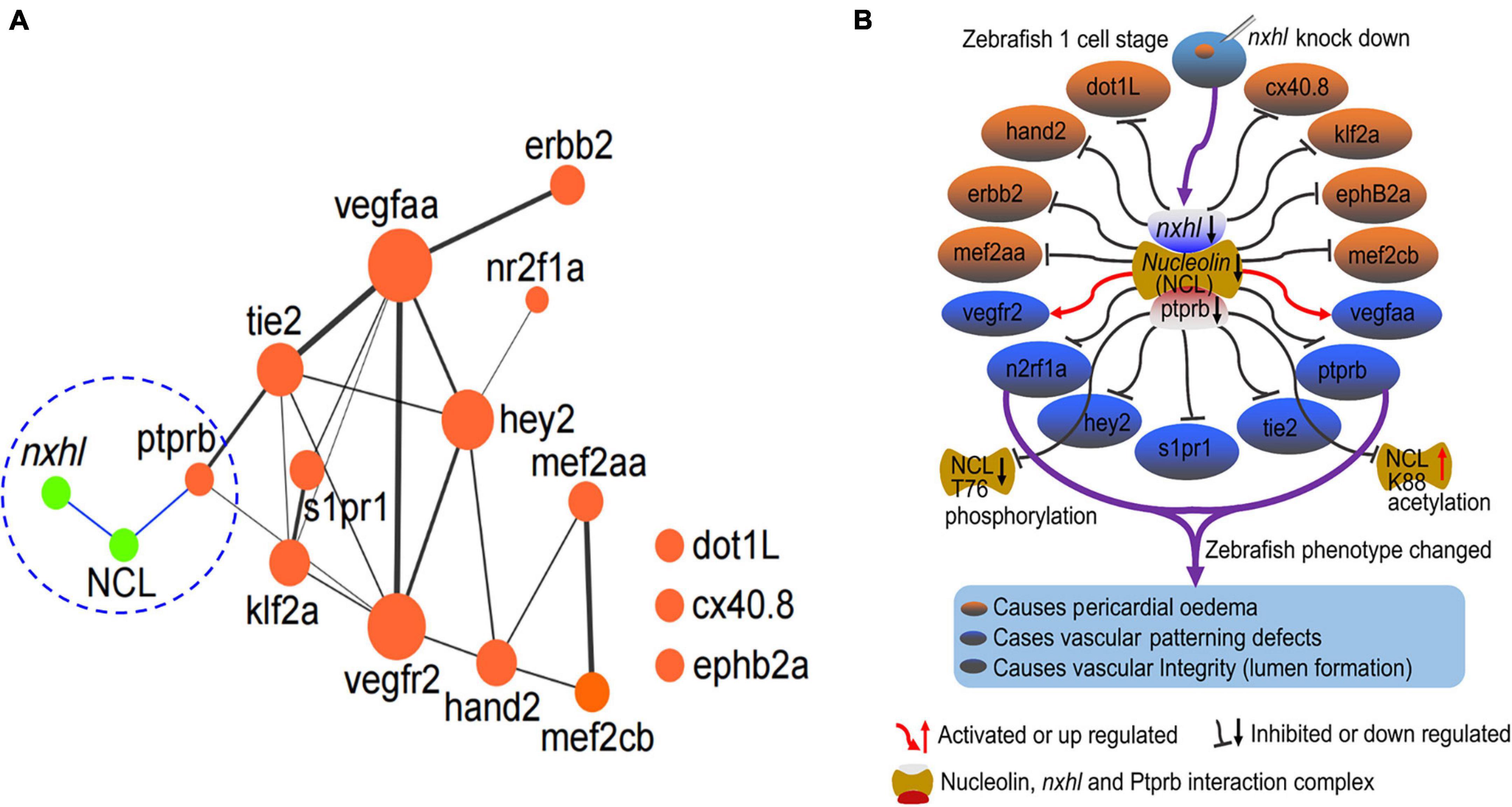

Nxhl Controls Angiogenesis by Targeting Vascular Endothelial Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase (ptprb) and Linking Angiogenesis Regulatory Genes

Based on above results, we concluded that nxhl controls angiogenesis through nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb)-linked angiogenesis regulatory genes. These findings are the first to uncover the existence of upstream regulatory genes of VE-PTP (ptprb). We then built a new schematic diagram based on the network in Figure 4C that shows the novel nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb) signaling links to the keystone angiogenesis genes (Figure 8A vs. Figure 4C). We also created a schematic diagram to describe the possible mechanism underlying nxhl-induced phenotypes (Figure 8B). Knockdown of nxhl significantly and broadly downregulated angiogenesis-associated landmark genes, including dot1L, hand2, erbb2, mef2aa, n2rf1a, hey2, s1pr1, tie2, ptprb, meff2cb, ephB2a, klf2a, and cx40.8, through the nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb) pathway, and vegfr2 and vegfaa negative feedback control this downregulation. Moreover, loss of nxhl increased the phosphorylation of NCL (T76), indicating that nxhl may control angiogenesis by impacting NCL posttranslational modification to regulate downstream VE-PTP signaling pathways. This highlights the crucial role of nxhl in angiogenesis via a hitherto unreported nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb) pathway that extends the upstream regulatory members of the keystone gene VE-PTP (ptprb). We conclude that nxhl controls angiogenesis by targeting VE-PTP (ptprb) through interaction with NCL and by linking vascular keystone regulatory genes. Given the extreme importance of angiogenesis and the broad connections with landmark genes, we believe that the identification of this novel signaling pathway to be of considerable importance for the study of angiogenesis development and treatment of cancers.

Figure 8. Nxhl controls angiogenesis by targeting VE-PTP (ptprb)-related angiogenic genes. (A) Schematic model illustrating the mechanism of nxhl in zebrafish angiogenesis and heart development. The interactions between nxhl mRNA and NCL protein, NCL protein and ptprb mRNA are new-found interactions in this study. It connects with the keystone network of angiogenesis and heart development. (B) Possible mechanism of nxhl in zebrafish angiogenesis and heart development. Knockdown of nxhl may downregulate the nxhl-NCL-ptprb complex, subsequently regulate the proteins associated with angiogenesis and heart development, and finally result in heart pericardial edema, vascular patterning and integrity defects.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that VE-PTP is a key player in the regulation of angiogenesis and the EC adherens junctions (Baumer et al., 2006; Winderlich et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2013; Monaghan-Benson and Burridge, 2013) as well as a potential therapeutic target for angiogenesis-dependent diseases (Wilke et al., 2014; Ferrara and Adamis, 2016). VE-PTP binds to several proteins, including Tie2, VEGFR2, VE-cadherin, and FGD5, that mediate angiogenic signaling pathways (Christian et al., 2003; Fogal et al., 2009; Koutsioumpa and Papadimitriou, 2014; Campochiaro et al., 2015; Vestweber, 2015). In the present study, we identified a novel zebrafish gene, nxhl, that controls angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro by targeting VE-PTP through interaction with NCL. We showed that nxhl physically binds to NCL, a protein that interacts with VE-PTP and thereby controls angiogenesis. Moreover, nxhl exhibits promising potential for the treatment of cancers. We described a novel nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP signaling pathway for angiogenesis regulation.

Anti-angiogenic drugs have been a focus of study, and many inhibitors of angiogenesis are currently used as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or cytokine treatment (Ebos and Kerbel, 2011). Previous studies have highlighted the value of VE-PTP in anti-angiogenic agents (Huang et al., 2006; Destouches et al., 2012; Gilles et al., 2016; Quiroz-Mercado et al., 2016). However, the upstream regulation mechanisms of VE-PTP are unknown. In this study, we identified nxhl as a novel powerful upstream regulator of VE-PTP based on the finding that nxhl not only sharply decreases expression of VE-PTP and other key angiogenic genes but also that its deletion causes angiogenesis phenotypes that resemble VE-PTP deficiency. Moreover, nxhl controls angiogenesis via EC migration and tube formation, consistent with the angiogenic characteristics of VE-PTP in EC adhesion and integrity (Nawroth et al., 2002; Nottebaum et al., 2008; Vestweber, 2015), confirming that its angiogenesis controlling function acts via ECs. This was also strongly supported by our finding that silencing of the highly conserved human homolog of nxhl not only inhibits HUVEC migration and tube formation but also suppresses the migration and invasion of cancer cell lines by inhibiting ECs. All these data suggest that nxhl is a powerful upstream angiogenesis controller targeting VE-PTP.

The effects of nxhl controlling angiogenesis depend on its binding with NCL, which simultaneously bridges nxhl and VE-PTP. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of the interactions between nxhl and NCL, and NCL and VE-PTP, uncovering a novel angiogenesis signaling complex upstream of VE-PTP. NCL is expressed broadly in all cells in a proliferation-dependent manner (Roussel and Hernandez-Verdun, 1994) and in nearly all cell compartments. Like VEP-TP, NCL is also associated with cancer and other angiogenic diseases. However, this function is more likely related to the cell surface NCL rather than those in other compartments. The cell surface NCL is clustered and highly expressed in ECs of angiogenic blood vessels during angiogenesis (Hovanessian et al., 2000; Christian et al., 2003; Fogal et al., 2009), suggesting that NCL functions as an angiogenic gene. Previous studies have defined NCL as both a prognostic marker and a therapeutic target (Srivastava et al., 1995; Schwab and Dreyer, 1997; Yelon et al., 2000; Di Segni et al., 2008; Wolfson et al., 2018), highlighting its potential value in the development of anti-angiogenic drugs (Huang et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2017). In this study, we identified the direct interactions between nxhl and NCL, and NCL and VE-PTP (ptprb) in both zebrafish and 293T cells, although we have not yet determined which subset of NCL (surface, nucleolar, or cytoplasmic NCL) participates in this interaction. Importantly, we demonstrated that silencing of NCL inhibits angiogenesis of HUVECs and expression of VE-PTP at both mRNA and protein levels. This further supports the hypothesis that NCL plays a key role in angiogenesis by directly controlling downstream VE-PTP. Moreover, deletion of nxhl caused a significant decrease in NCL, suggesting that nxhl significantly affects and regulates NCL. Previous studies have suggested that NCL phosphorylation status heavily affects its cellular compartmentalization (Schwab and Dreyer, 1997). This promotes EGFR phosphorylation, dimerization, and cell growth (Di Segni et al., 2008; Farin et al., 2011) and also promotes HER2 (namely, Erbb2) phosphorylation and subsequent MAPK/ERK pathway activation (Wolfson et al., 2016). Clinically, combination treatment with NCL and HER2 inhibitors exhibits superior efficacy compared with single treatment in the invasion capacity of breast cancer cells (Wolfson et al., 2018). Because EGFR and HER2 are closely associated with angiogenesis, we consider that nxhl may control angiogenesis by affecting NCL phosphorylation, thereby regulating downstream EGFR and HER2 signaling pathways. Notably, in our study the expression of Erbb2 was significantly affected by nxhl knockdown, partially supporting this point of view. However, this question needs to be investigated in future work. Taken together, our data enable us to conclude that nxhl regulates angiogenesis via the nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP (ptprb) pathway.

The strong effect of nxhl in controlling angiogenesis also relies on the effects of several other crucial downstream angiogenic genes (Tie2, VEGFaa, VEGFR2, S1pr1, and Hey2) that are broadly associated with VE-PTP signaling (Figures 4, 7). What must be stressed is that the expression of these genes can explain the phenotypes induced by nxhl deficiency. These genes all play irreplaceable roles in multiple aspects of angiogenesis during development. For example, Hand2 is vital in heart development in the zebrafish and mice (Srivastava et al., 1995; Yelon et al., 2000). It has been identified as a specifier of outflow tract cells in the mouse (de Soysa et al., 2019). Hey2 mediates the dynamics of cardiac progenitor cells in addition to the zebrafish heart (Gibb et al., 2018). It has been identified as a component of the NKX2-5 cardiac transcriptional network regulating the early stages of human heart development (Anderson et al., 2018). Dot1L (Nguyen et al., 2011), Mef2aa (Medrano and Naya, 2017), Mef2cb (Lazic and Scott, 2011), Erbb2 (Liu et al., 2010), Klf2a (Vermot et al., 2009), and EphB2a (Gerety and Anderson, 2002) also play key roles in the growth of the chamber, cardiomyocyte differentiation, valvulogenesis, and myocardial trabeculation during heart development. Importantly, heart and vascular development are always linked. Previous studies have shown that silencing of zebrafish S1pr1 not only leads to global and pericardial edema, a lack of blood circulation, and reduced vascularization in ISVs and CVPs (Mendelson et al., 2013) but also regulates endothelial barrier integrity via the S1pr1/VE–cadherin/EphB4a pathway (Tobia et al., 2012). Similar phenotypes can be induced by the knockdown of Nr2fla in zebrafish (Wu et al., 2014). Moreover, mutation of Nr2f1a results in smaller atria owing to a specific reduction in the atrial cardiomyocyte number and an increase in the rate of atrial cardiomyocyte differentiation (Duong et al., 2018). Another key gene, Tie2, is essentially required for ISV growth, sprouting, migration, and proliferation of tip cells and acts in coordination with VEGF signaling (Li et al., 2014). Loss of Tie2 leads to death at E10.5 owing to vessel remodeling defects and lack of trabeculation (Sato et al., 1995). Notably, the Ang-Tie2 system is indispensable for vascular and lymphatic development (Eklund et al., 2017). The anti-angiogenic effects of the VE-PTP inhibitor AKB-9778 likely rely on the Ang-Tie2 pathway (Nottebaum et al., 2008). In our study, nxhl deletion led to a significant decrease in Tie2, suggesting that it regulates not only VE-PTP but also the Ang-Tie2 system, which cross-talks with VE-PTP. From this point of view, nxhl is a multifunctional regulator of the angiogenesis process. This explains our findings that the phenotypes induced by nxhl knockdown mostly resemble the phenotypes caused by deletion of the genes associated with VE-PTP. Given the extreme importance of these genes in angiogenesis during development, we consider the phenotypes caused by nxhl morphants to be direct or indirect consequences of the downregulation of VE-PTP and these key genes. We believe that the present novel nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP signaling pathway is crucial in vertebrate angiogenesis regulation and anti-angiogenic diseases. This is supported by our findings that silencing of nxhl not only inhibits the proliferation, invasion, migration, and colony formation of HCC cells but also suppresses the EMT process as well as NCL, NCL T76, and VE-PTP (ptprb) in cancer cells. This again indicates that nxhl plays a significant role in regulation of angiogenesis, implying its value in anti-angiogenic drug exploration.

In this study, we demonstrated that a novel gene, nxhl, controls angiogenesis by targeting VE-PTP through interaction with NCL. Furthermore, we have elucidated some of the crucial downstream pathways that may be implicated in regulation of angiogenesis. This study is the first to reveal a new nxhl–NCL–VE-PTP signaling pathway governing vertebrate angiogenesis and its potential as a therapeutic target for cancer treatment.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data reported in this study are fully and freely available from the date of publication. RNA-Seq data of the embryo are available under BioProject PRJNA574895. Transcriptome (Illumina) data of nxhl silence are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with accession numbers SRR10199007 and SRR10199008 under BioProject PRJNA573544.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the SRCMO IACUC (No. 2018-0019).

Author Contributions

HLL and XHC designed the scientific objectives and oversaw the project. HLL, XHC, YDZ, YFD, and YL discussed the primary ideas of the manuscript. YDZ, YL, LQL, ZAS, YLY, and PFF collected samples for sequencing DNA and RNA. HLL and YDZ performed RNA-seq analysis and performed functional assay of zebrafish nxhl gene. YDZ, HLL, and YFD prepared the Supplementary Data and Method. XHC, YFD, and HLL prepared the draft manuscript with input from all other authors. HLL, XHC, YFD, and YL discussed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Guangxi science and technology major project (GuiKeAA18242031, GuiKeAA 18242031-2, GuiKeAA17204080, and GuiKeAA17204080-3) and the Guangxi Key Laboratory for Aquatic Genetic Breeding and Healthy Aquaculture, Guangxi Institute of Fishery Sciences (17-A-01-02 and 19-A-01-05).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhuanbin Wu for zebrafish analysis advices and technical consults.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.728821/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Expression profile of introns in Golden Pompano embryo development. (A) 19 embryo development stages were collected and transcriptome-sequenced. The FPKM of introns were used to draw the heatmap. A boundary lines between OSP-MGS and LGS-YAPS stages. (B) GO cluster of the differentially expressed genes. (C) KEGG cluster of the differentially expressed genes. Numbers of 1–57 below the heatmap represent embryo samples. Every three numbers represent one embryo stage. For example, number 1–3 represents stage OSP, number 55–57 represents stage YAPS.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Confirmation of nxhl gene knockdown. (A) Schematic map of nxhl gene and the MO design and micro-injection strategy. 4 ng morphants per fish embryo was injected. (B) The gel electrophoresis of PCR products of nxhl gene in control and nxhl-MO groups. Compared with control MO, nxhl MO shows quite weak expression of nxhl gene. (C) Expression profile of nxhl at 6 and 3 dpf in zebrafish embryo. hpf, hours post fertilization; dpf, days post fertilization.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Phenotypes of nxhl zebrafish morphants. 4 ng morphants per fish embryo was injected. (A) Gross morphology at 3-dpf. Compared with control MO, knock down nxhl present pericardial edema (red arrow) and caudal fin defects (blue arrow). (B) Representative bright field and fluorescent images of Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 embryos at 2-dpf after injection of nxhl morphants.

Supplementary Figure 4 | Knockdown efficiency of the siRNAs. Trails for the choose of siRNAs before the formal experiments were performed. Three siRNAs targeting the nxhl gene were designed and tested for the knockdown efficiency. The siRNA-2 with the highest knockdown efficiency (about 70%) was chosen to perform the subsequent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Gene expression profile post knockdown of nxhl comparing with control. Scatter of the differential expressed genes after injection of nxhl morphants.

Supplementary Figure 6 | KEGG enrichment of genes differentially expressed after knockdown of nxhl gene comparing with control.

Supplementary Figure 7 | Phenotypes of ptprb zebrafish morphants. 4 ng morphants per fish embryo was injected. (A) Effectiveness of ptprb knockdown was confirmed by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing. The zebrafish ptprb gene was targeted by specific morpholino antisense to prevent proper splicing of exon 4 (E4I4-MO). Primers 3F and 5R interrogate the presence of wild type (non-mutant) transcripts or those in which exon 4 has been skipped. Below the diagram is a schematic depiction of the exon 4-skipped transcript in the E4I4-MO–injected embryos (124 bp) as compared with control embryos (388 bp). RT-PCR of ptprb transcript from control and E4I4-MO morpholino- injected embryos 3 days after fertilization, demonstrating skipping of exon 4. Sanger sequencing of both the wild type band and the exon 4-skipped band validating the wild type sequence and the exon 4-skipped sequence. (B) Gross morphology at 2-dpf. Compared with control MO, knock down ptprb present pericardial oedema (red arrow). (C) Representative bright field and fluorescent images of Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 embryos at 2-dpf after injection of ptprb morphants.

Supplementary Figure 8 | Identification of pcDNA3.1-nxhl expression plasmid. (A) PCR amplification of nxhl gene (1,267 bp, including enzyme cutting sites NheI and KpnI, and protective bases). (B) Four monoclones were selected by PCR and used for sequencing identification. (C) Sequencing result of nxhl gene. The green underline is the fragment inserted into the vector, the vector sequence is on both sides. The red underline is the sequencing result of enzyme cutting site, which shows that the target sequence has been correctly constructed into the vector.

Supplementary Figure 9 | Identification of pcDNA3.1-nxhl-Flag expression plasmid. (A) PCR amplification of nxhl-Flag gene (1,306 bp, including enzyme cutting sites NheI and KpnI, and protective bases) based on pcDNA3.1-nxhl constructs. (B) Sequencing result of nxhl-Flag fragment. The green underline is the fragment inserted into the vector, which shows that the target sequence has been correctly constructed into the vector.

Supplementary Figure 10 | SDS-PAGE electrophoresis of ptprb and nxhl protein. Ptprb and nxhl protein was expressed in pet-b2m Rosetta expression system with kanamycin resistance, respectively. Ptprb (33 kDa) and Nxhl (62 kDa) was successfully expressed and the purity of the recombinant protein was 85%. The purified protein was used to immunize rabbits to produce antibody, respectively. M, protein marker. 1, whole bacterial protein. 2, pet-b2m-Nxhl protein induced by IPTG. 3 and 4 pet-b2m-ptprb protein induced by IPTG.