95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell Dev. Biol. , 21 December 2021

Sec. Stem Cell Research

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.723804

This article is part of the Research Topic Hematopoiesis: Learning from in vitro and in vivo Models View all 10 articles

Rongtao Xue1

Rongtao Xue1 Ying Wang2

Ying Wang2 Tienan Wang3

Tienan Wang3 Mei Lyu4

Mei Lyu4 Guiling Mo5

Guiling Mo5 Xijie Fan5

Xijie Fan5 Jianchao Li6

Jianchao Li6 Kuangyu Yen2*

Kuangyu Yen2* Shihui Yu5*

Shihui Yu5* Qifa Liu1*

Qifa Liu1* Jin Xu4*

Jin Xu4*ELMO1 (Engulfment and Cell Motility1) is a gene involved in regulating cell motility through the ELMO1-DOCK2-RAC complex. Contrary to DOCK2 (Dedicator of Cytokinesis 2) deficiency, which has been reported to be associated with immunodeficiency diseases, variants of ELMO1 have been associated with autoimmune diseases, such as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). To explore the function of ELMO1 in immune cells and to verify the functions of novel ELMO1 variants in vivo, we established a zebrafish elmo1 mutant model. Live imaging revealed that, similar to mammals, the motility of neutrophils and T-cells was largely attenuated in zebrafish mutants. Consequently, the response of neutrophils to injury or bacterial infection was significantly reduced in the mutants. Furthermore, the reduced mobility of neutrophils could be rescued by the expression of constitutively activated Rac proteins, suggesting that zebrafish elmo1 mutant functions via a conserved mechanism. With this mutant, three novel human ELMO1 variants were transiently and specifically expressed in zebrafish neutrophils. Two variants, p.E90K (c.268G>A) and p.D194G (c.581A>G), could efficiently recover the motility defect of neutrophils in the elmo1 mutant; however, the p.R354X (c.1060C>T) variant failed to rescue the mutant. Based on those results, we identified that zebrafish elmo1 plays conserved roles in cell motility, similar to higher vertebrates. Using the transient-expression assay, zebrafish elmo1 mutants could serve as an effective model for human variant verification in vivo.

The ELMO1 protein is known to interact with DOCK2 and participates in the regulation of cell motility by regulating the activity of the Rac proteins (Chang et al., 2020; Federici and Soddu, 2020). DOCK2 deficiency has been reported to be associated with immunodeficiency diseases (Dobbs et al., 2015). Conversely, analyses of genetic polymorphisms in different human populations around the world found that ELMO1 was associated with autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and nephropathy, but not immunodeficiency diseases (Hironori Katoh, 2006; Arandjelovic et al., 2019; Bayoumy et al., 2020). In addition to DOCK2, ELMO1 also interacts with DOCK180 to regulate cell migration (Grimsley et al., 2004). Through the interaction with DOCK proteins or RhoG and subsequent activation of the small GTPase such as RACs, ELMO1 involves in regulating lymphocyte migration or promoting cancer cells invasion (Katoh et al., 2003; Jiang et al., 2011; Capala et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Gong et al., 2018; Park et al., 2020). Studies in mice and cell cultures have revealed reduced cell migration speeds due to Elmo1 deficiency. In Elmo1-deficient mice, the number of neutrophils at chronic inflammation sites was significantly lower than that in wild-type mice. This neutrophil chemotaxis defect leads to reduced inflammation and the relief of autoimmune diseases in mice (Arandjelovic et al., 2019). Recently, ELMO1 protein has also been found to negatively regulate thrombus formation in mice (Akruti Patel et al., 2019). Moreover, Elmo1 has been reported to regulate the vascular morphogenesis, the peripheral neuronal numbers and myelination, and the structure formation of kidney during zebrafish development (Epting et al., 2010; Epting et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2016; Mikdache et al., 2020).

In a study of inflammatory bowel disease caused by Salmonella infection, bacterial internalization by macrophages was weakened in Elmo1-deficient mice, and led to a decrease in the bacterial load in mice intestines and reduced the level of intestinal inflammation (Das et al., 2015). Thus, studies on Elmo1 in mouse models indicated that altered Elmo1 functions changed the function of immune cells and regulated the progression of autoimmune diseases (Hathaway et al., 2016).

Previous studies of clinical samples indicated that ELMO1 affected the progression of disease by affecting the chemotaxis of immune cells to sites of inflammation (Janardhan et al., 2004; Das et al., 2015; Hathaway et al., 2016). In some studies, neutrophils were directly isolated from patients who carried ELMO1 variants, and their migration abilities were evaluated in vitro (Arandjelovic et al., 2019). However, direct functional verification of ELMO1 variants in vivo has not been performed. Additional ELMO1 variants are routinely identified by high-throughput genome sequencing of human genomes. However, whether such ELMO1 variants over-activate or reduce the function of immune cells remains unknown. Therefore, it is necessary to generate a convenient animal model to directly test the functions of ELMO1 variants in vivo.

Recently, zebrafish have been established as an excellent model for the verification of variants of heart and hematopoietic diseases due to their short reproduction cycle, transparent larvae, and relatively low maintenance/drug management costs (Dooley and Zon, 2000). In those studies, target genes containing variants of interest were expressed in zebrafish, and functional analyses were performed in vivo to assess the susceptibility of such variants to cardiac and hemostatic diseases (Hu et al., 2017; Hayashi et al., 2020). For elmo1, previous studies focused on its functions in the development of peripheral neurons, vessel, and kidney (Epting et al., 2010; Epting et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2016; Mikdache et al., 2020). On the other hand, previous study showed that elmo1 knocked-down macrophages present defective engulfment of apoptotic cells and abnormal morphology (Van Ham et al., 2012). Therefore, with the elmo1 mutation zebrafish, more functions of zebrafish elmo1 in immune cells need to be further explored.

In our work, we generated zebrafish elmo1 mutants. Using time-lapse live imaging to directly record the dynamic immune cells, we found that the zebrafish elmo1 gene was involved in regulating the motility of neutrophils and T-cells, suggesting a conserved role for elmo1 from fish to humans. Using the elmo1 mutant model, we evaluated three novel ELMO1 variants found in the GuangZhou KingMed Center For Clinical Laboratory Co., Ltd genetics database: p.E90K (c.268G>A), p.D194G (c.581A>G), and p.R354X (c.1060C>T). While p.E90K and p.D194G rescued the motility defect of neutrophils in elmo1 mutants, the p.R354X variant did not.

In summary, we generated a zebrafish model to study the elmo1 gene and verified the functions of three novel human ELMO1 variants in vivo.

The zebrafish AB and SR strains, elmo1 heterozygous fish, and transgenic fish lines were raised and maintained at 28.5°C in E2 media (Dahm, 2002) and staged as previously reported (Kimmel et al., 1995). Transgenic lines, including Tg(globin:DsRedx), which is short for Tg(globin:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP) (Tian et al., 2017), Tg(lyz:DsRed) (Li et al., 2012), Tg(lck:DsRedx), which is short for Tg(lck:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP) (Tian et al., 2017), and Tg(mpeg1:DsRedx), which is short for Tg(mpeg1:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP) (Lin et al., 2019), were used for fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry analyses. elmo1szy103 mutant was generated by TALEN technology in the ABSR background. The primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplementary Table S1. DdeI digestion was performed following PCR, and while the wild-type allele could be digested, the mutant allele could not. Zebrafish embryos were acquired by natural spawning.

In experiments of whole embryos, TRIzol reagent (15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to extract total RNA from the wild-type, elmo1+/− and elmo1−/− from the offspring of the heterozygous intercrosses. Reverse transcription was performed with M-MLV (M1701; Promega) to obtain the cDNA library. qRT-PCR was used to detect elmo1 gene expression using the SYBR Green master mix (04707516001; Roche). In experiments with the cells of a specific lineage, we used 3 days post fertilization (dpf) Tg(globulin: DsRedx), Tg(lyz:DsRed) and Tg(mepg1:DsRedx), and 5 dpf Tg(lck:DsRedx) to label erythrocytes, neutrophils, macrophages and T-cells, respectively. The cells labeled with DsRed were sorted by flow cytometry, and collected into TRIzol reagent for total RNA extraction. Glycogen (R0551; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added during RNA precipitation to improve efficiency. The SuperScript™ IV (18091200; Invitrogen) kit was used to obtain the cDNA library. In this process, all of the obtained RNA was added to the reverse transcription PCR. SYBR Green master mix (11198ES03; Yeasen) was used for qRT-PCR and the expressions of elf and elmo1 were determined. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) assays with zebrafish embryos were conducted as previously described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008) using probes against elmo1, cmyb, lyz, mpeg1 and rag1. Antisense elmo1 RNA probes were synthesized using the full length elmo1 CDS (NM_213091.1) cloned into the PCS2 vector.

Immunofluorescence staining assays with zebrafish larvae were conducted as previously described (Barresi Mj and Devoto, 2000; Jin et al., 2006). In brief, 3 dpf larvae were fixed in 4%PFA for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the larvae were incubated in primary antibody against ELMO1 (ab155775; Abcam) 1:50 diluted and primary antibody against GFP (ab6658; Abcam) 1:400 diluted in 5%FBS/1xPBS at 4°C overnight. After washing, the larvae were incubated in secondary antibody of Alexa Fluor 555-anti-rabbit (A31572; Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 488-anti-goat (A11055; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Images were taken under Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope.

Blood samples were collected from patients, and genomic DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After enrichment and purification, the DNA libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 sequencer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, United States). All reads were aligned to the reference human genome (UCSC hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (v.0.5.9-r16) (Li and Durbin, 2010). After data annotation using the PriVar toolkit (Zhang et al., 2013), the clinical significance of the variants was identified (Yang et al., 2013).

To express the constitutively active form of zebrafish Racs, we cloned the zebrafish p.G12V mutation (Nishida et al., 1999) of the rac1a/1b/2 CDS after the coro1a promoter region, and linked it to DsRed protein using P2A. The resulting construct, coro1a:rac1a/1b/2 CA-P2A-DsRed (40 ng/μL) and transposase mRNA (50 ng/μL) were injected into the single cell stage of elmo1−/− and sibling embryos. The lyz:GFP was injected into the above-mentioned embryos as the control plasmid. The final volume injected was 1 nL and the embryos were raised to the desired stage for analysis.

In order to analyse the FRET ratio change specific in wild type and elmo1−/− neutrophil, we firstly cloned the RacFRET biosensor from pRaichu-Rac1 (Itoh et al., 2002) and inserted it after the lyz promoter. The resulting plasmid lyz:Rac1-FRET was co-injected with the transposase mRNA into zebrafish embryos at one cell stage. The final concentration of lyz:Rac1-FRET and transposase mRNA were 40 and 50 ng/μL, respectively. After microinjection, we raised the embryos to 3 dpf and took the raw images of the CFP (Ex 458nm; Em 454–534 nm), YFP (Ex 514; Em 535–590 nm) and FRET (Ex 458; Em 535–590 nm) by Zeiss LSM880 with an opened pinhole. A 20x objective was used for photograph. The FRET to CFP ratio image was produced from the raw images in a series of processing steps using ImageJ software (Bosch and Kardash, 2019). When the final FRET ratio image was generated, we then analysed the histogram and exported for data performance.

To express the zebrafish elmo1 in neutrophils, we expressed zebrafish elmo1 (NM_213,091.1) under the control of the lyz promoter and used the P2A self-cleaving peptide to link the zebrafish Elmo1 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Kitaguchi et al., 2009). To express the zebrafish elmo1 in T-cells, Elmo1 was directly linked with GFP and its expression was controlled by the lck promoter (Langenau et al., 2004). For experiments involving the expression of human ELMO1 variants in neutrophils for in vivo functional verification, the wild-type form of the human ELMO1 (NM_014800.11) CDS and its variants CDS were directly linked to GFP following the lyz promoter. The resulting vectors: lyz:elmo1ze-P2A-GFP (lyz:elmo1ze), lck:elmo1ze-GFP (lck:elmo1ze), lyz:ELMO1hu-GFP (hu-WT), lyz:E90K-GFP (E90K), lyz:D194G-GFP (D194G), and lyz:R354X-GFP (R354X), (40 ng/μL), as well as transposase mRNA (50 ng/μL) were injected into the one cell stage of elmo1−/− and sibling embryos. lyz:GFP and lck:DsRedx were injected into the above-mentioned embryos as the control plasmids. The final volume of the microinjection was 1 nL. Following injection, embryos were raised to the desired stage for analysis.

Time-lapse imaging was performed according to a previous report (Xu et al., 2016). In brief, 3 dpf larvae were anesthetized in 0.01% tricaine (A5040; Sigma-Aldrich), mounted in 1% low melting agarose and imaged on a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope with a 28°C thermal chamber. A 10× objective was used for neutrophil tracking, while a 20× objective was used for T-cell tracking in time-lapse images. The Z-step size was set to 3 µm and 15–20 planes were typically taken in the z-stack at <3 min intervals. The images were processed using ImageJ software, and cell tracking analysis was performed using the MTrackJ plugin. The tracking path of individual cells was extracted from the exported tracking results, and merged using Photoshop software.

Tail fin injury was performed as previously described (Li et al., 2012). Briefly, lesions were induced in the tail fin of embryos anesthetized with 0.01% tricaine (A5040; Sigma-Aldrich) using a blade.

E.coli infection was performed as previously described (Nguyen-Chi et al., 2014). In brief, single colony of E.coli which expressing GFP (Olson et al., 2014) were incubated in LB Broth Miller (MKCL4658; Sigma-Aldrich) containing the antibiotic ampicillin (A100339; Sangon Biotech) at 37°C on orbital shaker for at least 24 h before experimentation. After washing cells in 1×PBS and centrifuging at 500 g for 5 min, the E.coli were resuspended and diluted to the desired concentration in 1×PBS. E.coli were injected into the otic vesicle of zebrafish larvae and observed at the desired developmental stage.

Statistical parameters (mean ± SD) and statistical significance are shown in the figures and described in the Figure Legends. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7. Unpaired Student’s t-tests were used to calculate the p-value of pairwise comparisons. For multiple comparisons, significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. For survival curves, significance was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier curve. Two-tailed p-values were calculated for all t-tests.

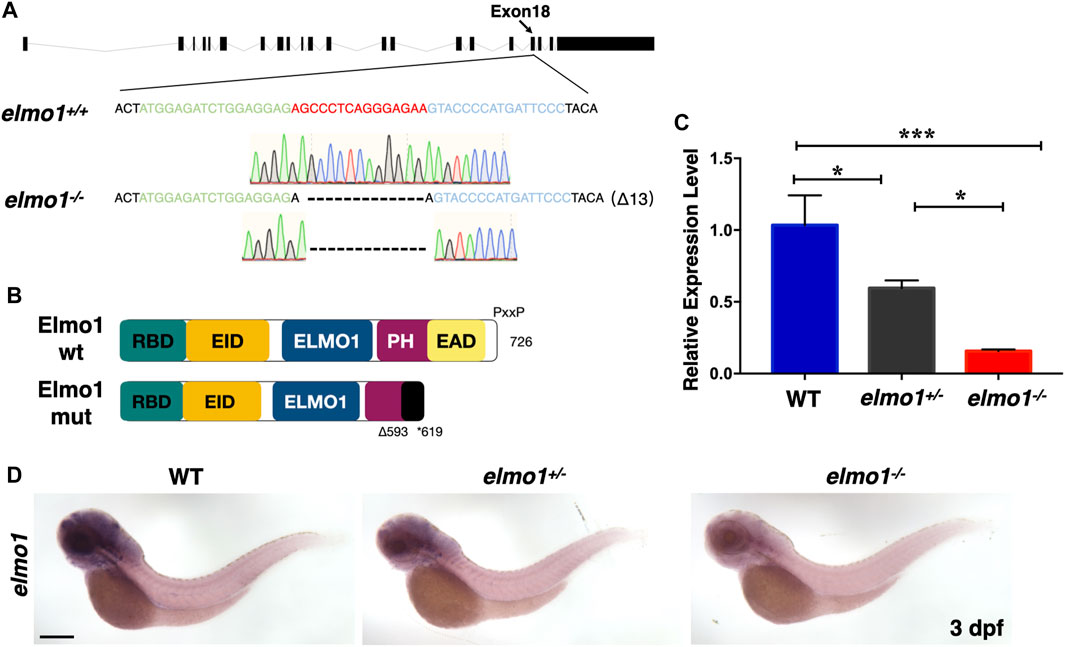

We carried out WISH to examine the expression pattern of elmo1 in zebrafish. We found that elmo1 was expressed in vessels at the 20-somites stage. From 22 h post fertilisation (hpf), elmo1 began to accumulate in the CNS, as was also observed in a prior study (Epting et al., 2010) (Supplementary Figure S1A). qRT-PCR revealed that elmo1 accumulated in leukocytes (Supplementary Figure S1B). To establish a zebrafish model to study human variants of elmo1, we used TALEN technology (Moore et al., 2012) and targeted exon 18 to disrupt the elmo1 gene (NC_007130.7) (Figure 1A). A frame shift mutation was caused by a 13 bp deletion and resulted in a premature stop codon, which lead to the loss of the PH domain (Figure 1B). We named this mutant elmo1szy103 and use elmo1−/− for short hereafter. Using qRT-PCR and WISH, the expression level of elmo1 in the offspring of mutant heterozygote intercrosses was evaluated. A gradient level of expression was observed in the wild-type (WT), elmo1+/−, and elmo1−/− larvae at 3 dpf (Figures 1C,D); thus, indicating that the mutant form of the elmo1 mRNA might be unstable. Furthermore, we directly examined Elmo1 protein in the elmo1−/− larvae. We found that Elmo1 protein was readily detected in the siblings by immunofluorescence staining while it was hardly detected in the elmo1−/−, suggesting a reduced Elmo1 level in mutants (Supplementary Figure S1D).

FIGURE 1. The establishment of the zebrafish elmo1 mutant. (A) Schematic representation of the elmo1 genomic locus (NC_007130.7). The extended region on exon 18 represents the sequence targeted by the TALEN system. Green: left TALEN arm binding site. Blue: right TALEN arm binding site. Red: spacer site. elmo1+/+ corresponds to the wild-type allele while elmo1−/− represents the loss of function allele in this study. Dashes represent the 13 base pair deletion. (B) Schematic view of the wild-type Elmo1 protein (Elmo1 wt) and the mutated Elmo1 protein (Elmo1 mut). The 726 amino acid (aa) Elmo1 wt contains five conserved domains (NP_998,256), while the Elmo1 mut resulting in a truncated protein end up at 619 aa. RBD: RhoG-binding domain; EID: ELMO inhibitory domain; ELMO1: ELMO1 domain; PH: pleckstrin homology; EAD: ELMO auto-regulatory domain. (C) The qRT-PCR result showed the relative expression level of the elmo1 gene in the offsprings of heterozygous intercross at 3 dpf. Three independent experiments were performed. One-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005. (D) elmo1 expression pattern detected by WISH in the offsprings of heterozygous intercross at 3 dpf. Scale bar: 200 μm.

The elmo1−/− larvae survived to adulthood and adult mutants remained healthy throughout the first year compared with their siblings. However, the death rate of adult mutants increased rapidly after 1 year (Supplementary Figure S1C). As Elmo1 has been reported to regulate leukocyte motility in mice, we hypothesized that mutation of elmo1 might lead to immune dysfunction (Sarkar et al., 2017; Arandjelovic et al., 2019).

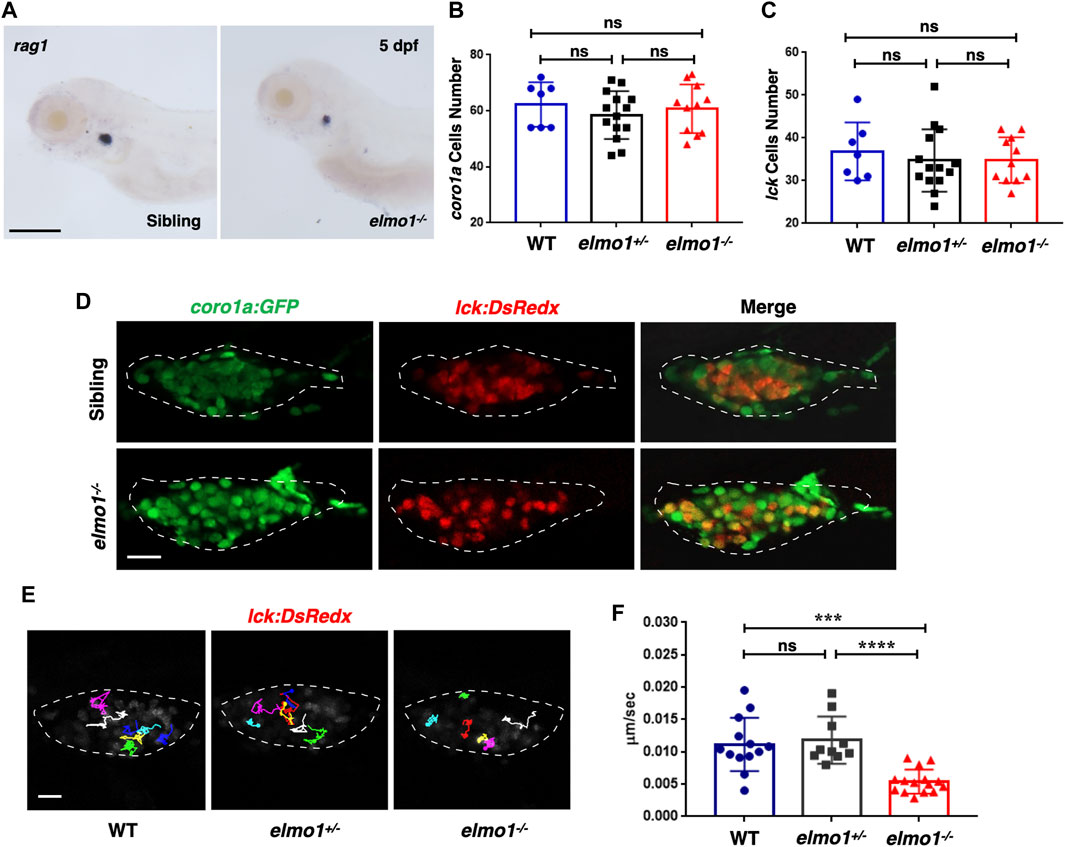

We first preformed WISH to examine the development of hematopoietic lineages in the elmo1−/− larvae. cmyb, lyz, and mpeg1 were used as markers in hematopoietic progenitor and stem cell (HSPCs), neutrophils, and macrophages, respectively. The WISH results revealed no significant differences in those markers between WT and elmo1−/− larvae at 3 dpf (Supplementary Figures S2A–C). Only rag1, which represents T-cells, was slightly decreased in elmo1−/− larvae at 5 dpf in the thymus (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the number of Tg(coro1a:GFP)-expressing leukocytes and that of Tg(lck:DsRedx)-expressing T-cells in the thymus were similar between homozygous elmo1−/− and heterozygous or wild-type siblings (Figures 2B–D). Thus, the reduction of rag1 in mutants might suggest immature T-cell development instead of cellular loss. Similar to the findings at the larval stage, T-cell number in adulthood was not significantly different between elmo1−/− and siblings in the kidney, peripheral blood (PB) and spleen (Supplementary Figures S3A–G), as determined by flow cytometry.

FIGURE 2. T-cell motility in the thymus was reduced at the larval stage of the elmo1 mutant. (A) rag1 WISH data indicate a T-cell defect in the elmo1−/− larvae at 5 dpf. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B, C) Quantification of coro1a:GFP positive cells (B) represents whole leukocytes and lck:DsRedx positive (C) cells represent T-cells within the thymus in the wild-type (WT), elmo1+/−, elmo1−/− larvae respectively. There was no significance between them. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance. (D) Fluorescence images show that coro1a:GFP represent whole leukocytes and lck:DsRedx represent T-cells show no significance between the siblings and elmo1−/− larvae in the thymus at 5 dpf. The white dotted region indicates the thymus in the image. Scale bar: 10 μm. (E) Track path of lck:DsRedx labeled T-cells of the WT, elmo1+/− and elmo1−/− larvae recorded by live imaging at 5 dpf. The white dotted region indicates the thymus. Each line represents the migration path of one T-cell. Scale bar: 10 μm. (F) Quantification of T-cells migration speed in live imaging of the WT (13 cells of 4 larvae), elmo1+/− (10 cells of 4 larvae) and elmo1−/− (15 cells of 5 larvae) larvae in the thymus at 5 dpf. The migration speed of T-cells dramatically decreased in the elmo1−/− larvae. Each dot represents the average speed of one T-cell. Three independent experiments were performed. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

We next examined whether T-cell motility was affected in the mutant, as suggested in a previous study in which ELMO1 and DOCK2 worked in concert to regulate T-cell motility in peripheral lymphoid organs (PLOs), including spleen and lymphoid nodes (Stevenson et al., 2014). We carried out live imaging to trace individual T-cells in the thymus of Tg (lck:DsRedx) larvae. The results showed that the speed of T-cell migration was drastically decreased in elmo1−/− larvae, suggesting impaired mobility of elmo1 deficient T-cells (Figures 2E,F).

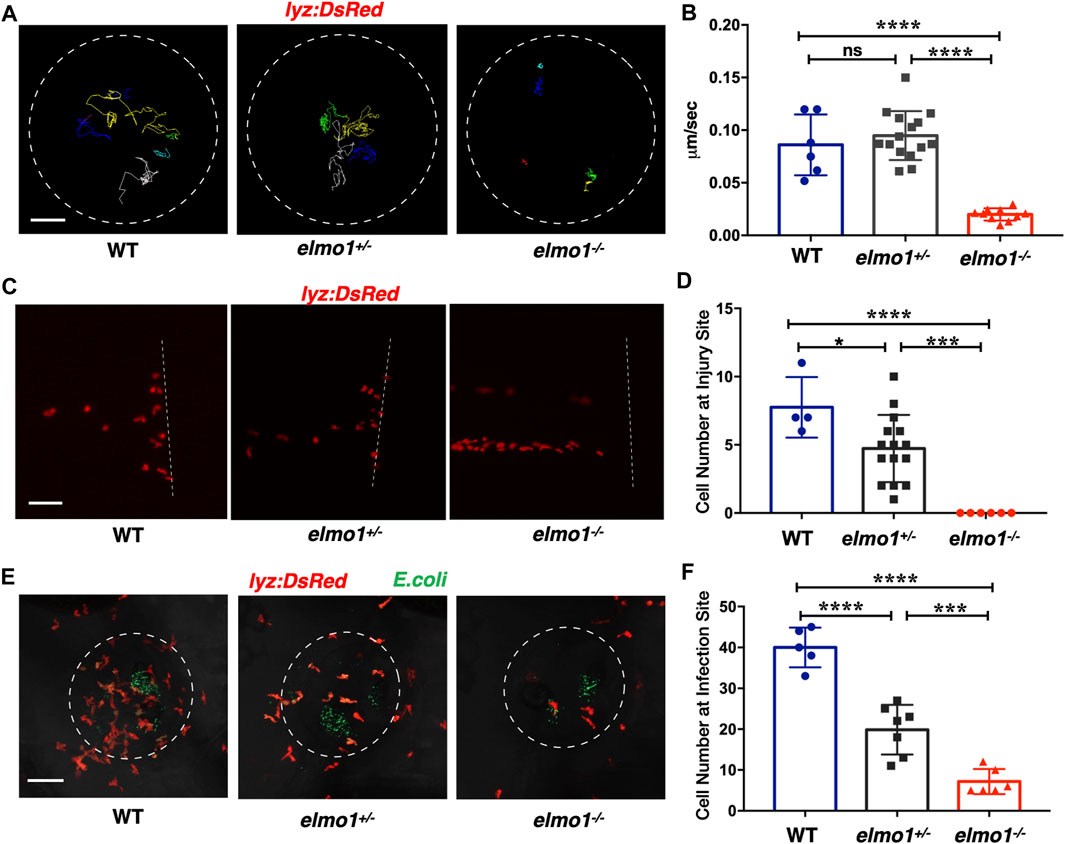

Previous studies showed that fewer neutrophils responded to inflammation in Elmo1-deficient mice (Arandjelovic et al., 2019). Thus, we asked whether defects of neutrophils could be observed in zebrafish elmo1 mutants. Our WISH data revealed a normal number of neutrophils in elmo1−/− larvae (Supplementary Figure S2B), and thus, we first examined the motility of neutrophils on the yolk sac using live imaging of Tg (lyz:DsRed) larvae at 3 dpf. We found that neutrophils failed to elongate their pseudopodia (Supplementary Figure S4A) and exhibited clumsy amoeboid movement in the elmo1−/− larvae compared with their siblings (Supplementary Video S1). Consequently, the speed of neutrophil movement decreased from 0.08 μm/s in siblings to 0.01 μm/s in elmo1−/− larvae (Figures 3A,B). In addition, we further examined the motility of macrophage on the yolk sac at 3 dpf. On the contrary to neutrophil, the basal movement of macrophage showed no difference between elmo1−/− and siblings suggesting that elmo1 is not essential for macrophage motility (Supplementary Figures S4C,D).

FIGURE 3. Neutrophils showed attenuated motility and impaired chemotaxis to injury/infection in the elmo1 mutant. (A) Track path of lyz:DsRed labeled neutrophils of the WT, elmo1+/− and elmo1−/− larvae on the yolk sac recorded by live imaging at 3 dpf. The white dotted circle indicates the imaging region of the yolk sac. Each line represents the migration path of individual cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of neutrophils migration speed of the WT (6 cells of 3 larvae), elmo1+/− (15 cells of 5 larvae), and elmo1−/− (10 cells of 5 larvae). The elmo1−/− showed dramatically decreased speed compared with the WT and elmo1+/−. (C) Fluorescent image of tail fin transection of the WT, elmo1+/− and elmo1−/− larvae at 3 dpf. The larvae tail region was imaged and the white dotted line represents the transection site. lyz:DsRed represents neutrophils failed to accumulate to the injury site in the elmo1−/− compared with the WT and elmo1+/−. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Quantification of neutrophils accumulated at the tail fin transection site. Neutrophils of the elmo1−/− larvae failed to respond to injury compared with the WT and elmo1+/−. (E) Fluorescent image of bacterial infection in the otic vesicle of WT, elmo1+/− and elmo1−/− larvae at 3 dpf. The white dotted circle represents the infection region. Bacteria of E.coli were labeled by GFP. lyz:DsRed labeled neutrophils showed a decreasing number at the infection region in the elmo1−/− compared with the WT and elmo1+/−. Scale bar: 50 μm. (F) Quantification of lyz:DsRed labeled neutrophils accumulated at the infection region. Neutrophils of the elmo1−/− larvae failed to respond to infection compared with the WT and elmo1+/−. In quantification results, each dot represents the neutrophil number in the infected region in individual larvae. Three independent experiments were performed. Here presents one result of three experiments. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001. (B, C, F).

To test whether the attenuated motility would affect an immune response, we performed tail fin transection in 3 dpf Tg(lyz:DsRed) larvae. As previously reported, wild-type neutrophils first arrived at the site of injury within 30 min of tail fin transection. Their number peaked at around 6 h post-transection (hpt) and returned to the basal level at 24 hpt (Li et al., 2012). In contrast, the neutrophil number was greatly reduced at the site of injury in elmo1−/− larvae from 30 min to 6 hpt after tail fin transection (Figures 3C,D; Supplementary Figure S4B).

We next examined the chemotaxis of neutrophils under infection conditions. We injected fluorescent E.coli into the otic vesicle of 3 dpf Tg(lyz:DsRed) larvae so that neutrophil chemotaxis toward bacteria could be observed directly. Since neutrophil count peaked at 3 h post-injection (hpi) (Harvie and Huttenlocher, 2015), we calculated the number of neutrophils in the region of the otic vesicle between 2-4 hpi. We found that neutrophil number was largely reduced in the otic vesicle in elmo1−/− larvae, suggesting the elmo1 deficiency caused defects in the neutrophil response to bacterial infection (Figures 3E,F).

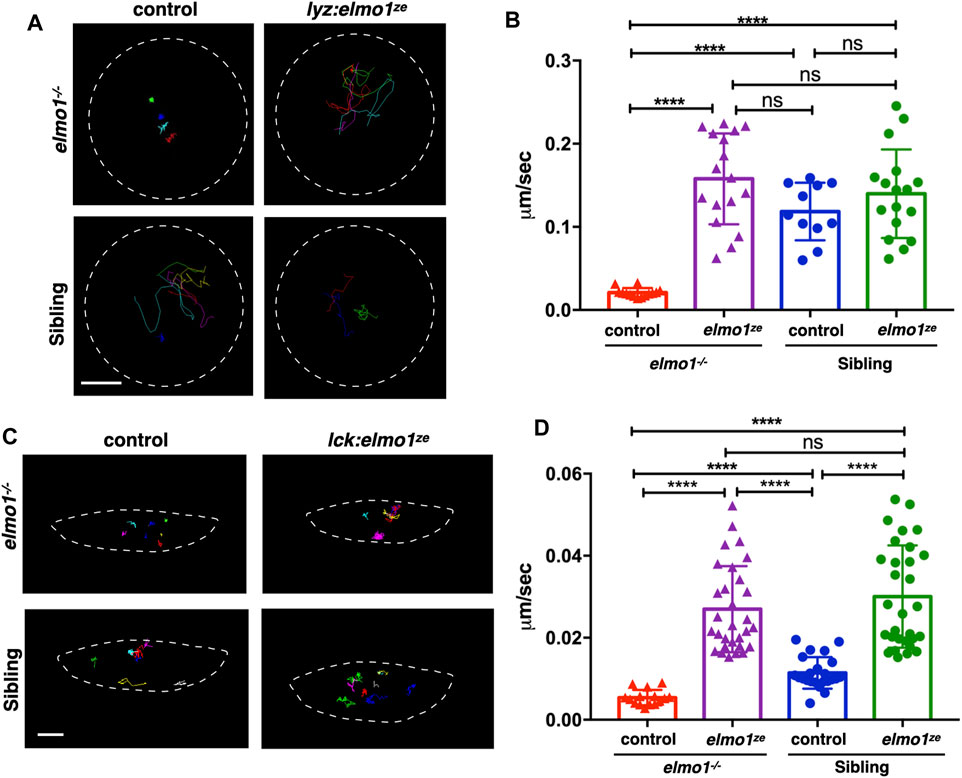

We next investigated whether the impaired motility of leukocytes in the elmo1−/− mutant was due to cell-autonomous or non-cell-autonomous effects. We utilized the neutrophil-specific promoter, lyz, to transiently express the WT form of zebrafish elmo1 (elmo1ze) in neutrophils of elmo1−/− mutants and their siblings. Neutrophils expressing WT elmo1 were visualized by GFP-linked Elmo1 (lyz:elmo1ze). The migration of such neutrophils on the yolk sac was recorded by live imaging and their migration speeds were calculated. We found that the speed of neutrophils largely recovered after neutrophil-specific elmo1ze expression (Figures 4A,B; Supplementary Video S2). We also examined the function of elmo1 in T-cells using a similar approach. The elmo1ze was transiently expressed from the lck promoter (lck:elmo1ze) in T-cells and the results indicated that the speed of T-cells in elmo1−/− larvae was elevated (Figures 4C,D). Collectively, our results suggested that elmo1 was cell-autonomously required for the motility of neutrophils and T-cells in zebrafish larvae.

FIGURE 4. The elmo1 was cell-autonomously required for the motility of leukocytes in zebrafish larvae. (A) Track path of neutrophils expressing lyz:GFP (control) or lyz:elmo1ze-GFP (lyz:elmo1ze) on the yolk sac in the elmo1−/− and sibling larvae recorded by live imaging at 3 dpf. Each line represents the migration path of a single cell recorded by live imaging. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the neutrophils migration speed of the control and elmo1ze group in elmo1−/− (14 cells of 4 larvae, 17 cells of 6 larvae) and sibling (11 cells of 4 larvae, 17 cells of 6 larvae) larvae. Compared with the control group, the migration speed of neutrophils expressing lyz:elmo1ze was significantly increased in the elmo1−/− larvae. Each dot represents the average speed of one individual cell. Three independent experiments were performed. Here present the summarized results of three experiments. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, ****p < 0.001. (C) Track path of T-cells expressing lck:DsRedx (control) or lck:elmo1ze-GFP (lck:elmo1ze) within the thymus in elmo1−/− and sibling larvae recorded by live imaging at 5 dpf. Each line represents the migration path of a single cell recorded by live imaging. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Quantification of the T-cells migration speed of control and elmo1ze group in elmo1−/− (15 cells of 4 larvae, 30 cells of 9 larvae) and sibling (22 cells of 4 larvae, 31 cells of 9 larvae) larvae. Compared with the control group, the migration speed of T-cells expressing lck:elmo1ze was significantly increased in the elmo1−/− larvae. Each dot represents the average speed of one individual cell. Three independent experiments were performed. Here present the summarized results of three experiments. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, ****p < 0.001.

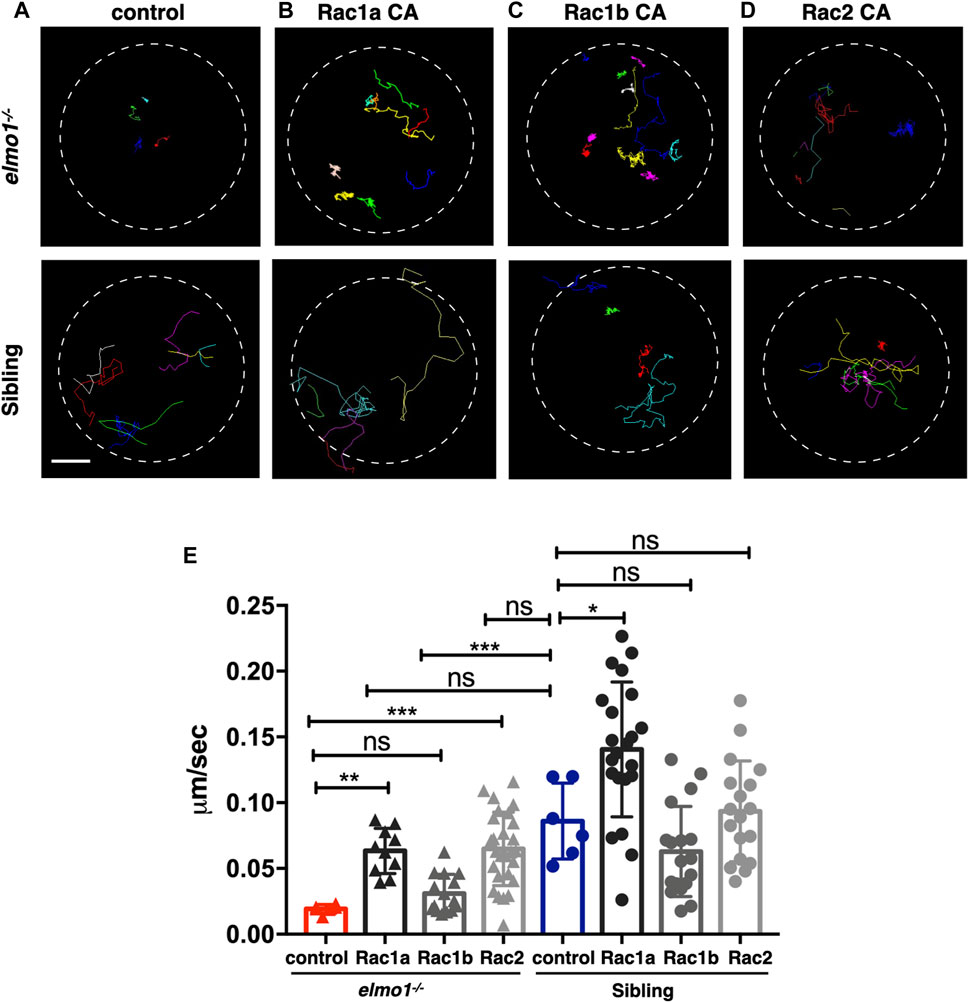

Previous studies demonstrated that ELMO1 regulated cell migration by activating RAC proteins (Grimsley et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2018). There are three RAC genes, including RAC1, RAC2, and RAC3 in vertebrate. RAC1 is ubiquitously expressed, while RAC2 is specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells (Mulloy et al., 2010), and RAC3 is primarily found in the neurons (Wang and Zheng, 2007). In zebrafish, RAC1 and RAC3 have two orthologue: rac1a/b and rac3a/b, whereas RAC2 only has one orthologue: rac2. From the single-cell transcriptome atlas of zebrafish, rac1a/b and rac2, but not rac3a/b, are expressed in leukocytes (Farnsworth et al., 2020). We employed RacFRET biosensor to examine whether the Rac activation was affected due to Elmo1 deficiency. We cloned the RacFRET biosensor from the Raichu-Rac1 plasmid (Itoh et al., 2002) and constructed it after the lyz promoter so that the FRET biosensor can be specifically expressed in neutrophils. As described in previous studies, CFP and YFP was used as the donor and the acceptor, respectively (Itoh et al., 2002). We measure the FRET to CFP change ratio to represent the GTP-bound Rac activity (Aoki and Matsuda, 2009; Bosch and Kardash, 2019), and found that the mean ratio of FRET decreased in elmo1−/− neutrophils (Supplementary Figures S5A–C). These results indicated that the Elmo1 deficiency resulted in reduced Rac binding to GTP. Next, to investigate whether the cell motility defects of the elmo1−/− larvae were caused by reduced Rac activation, we transiently expressed constitutively active rac1a/b and rac2 under the control of the leukocyte-specific coro1a promoter in the elmo1 mutant. We linked DsRed to Racs using the P2A self-cleaving peptide to visualize neutrophils expressing constitutively active Rac protein (p.G12V). Their movement was recorded by live imaging and their speed was calculated. Compared with the control (Figure 5A), we found that constitutively active Rac1a (Figures 5B,E) and Rac2 (Figures 5D,E), but not Rac1b (Figures 5C,E), could significantly rescue the defective motility of neutrophils in elmo1−/− larvae (Supplementary Video S3).

FIGURE 5. Constitutively activated Rac rescued the neutrophil motility deficiency of the elmo1 mutant. (A) Track path of neutrophils expressing lyz:GFP in the elmo1−/− and sibling larvae recorded by live imaging at 3 dpf. (B–D) Track path of neutrophils expressing constitutively activated Racs (Racs CA) in the elmo1−/− and sibling larvae recorded by live imaging at 3 dpf. (B) Rac1a CA, (C) Rac1b CA, (D) Rac2 CA. Each line represents the migration path of individual cells. (A–D) Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Quantification of the migration speed of control and neutrophils expressing constitutively activated Racs in the elmo1−/− (6 cells of 3 larvae, 10 cells of 6 larvae, 13 cells of 6 larvae, 25 cells of 6 larvae) and sibling (6 cells of 3 larvae, 22 cells of 6 larvae, 18 cells of 6 larvae, 18 cells of 6 larvae) larvae. Compared with the control group, the migration speed of neutrophils expressing Rac1a CA (Rac1a) and Rac2 CA (Rac2) were significantly increased. Neutrophils expressing Rac1a CA (Rac1a) also show an increased the migration speed in sibling. Each dot represents the speed of individual cells. Three independent experiments were performed. Here present the summarized results of three experiments. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

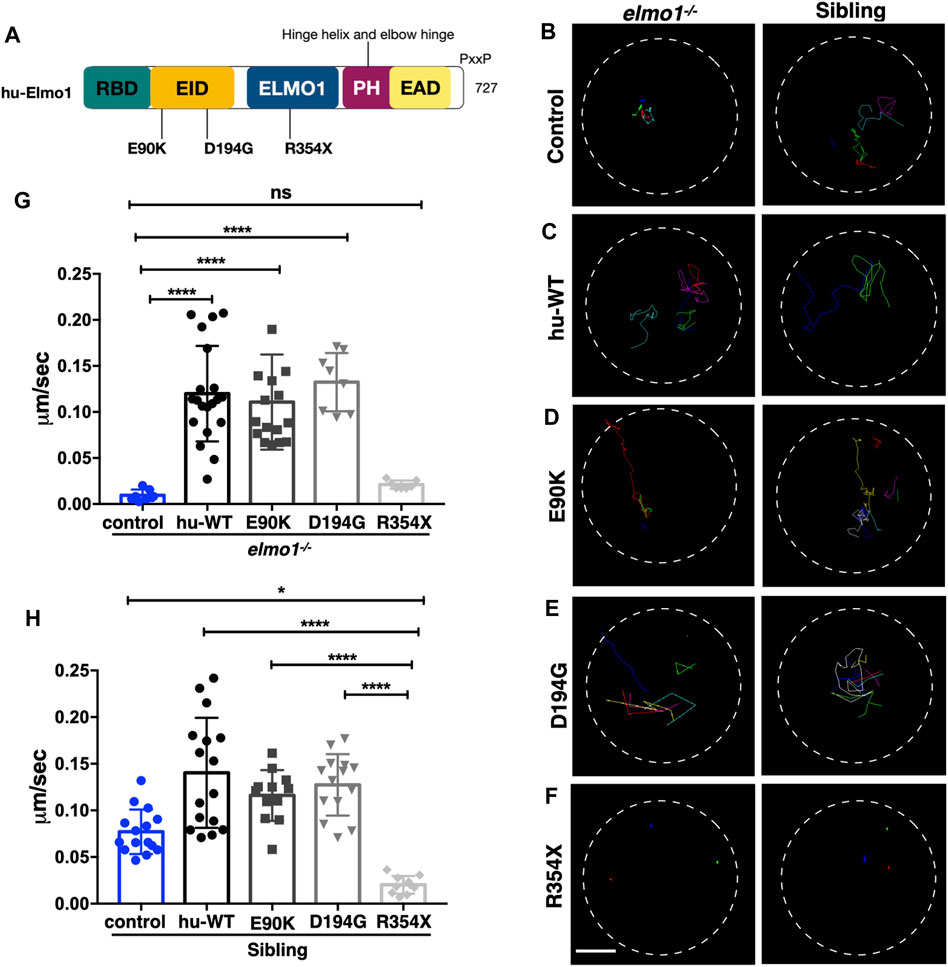

Zebrafish Elmo1 (NP_998256) shares 89.41% identity with human ELMO1 (NP_055615) (Epting et al., 2010). Our data also indicated that zebrafish Elmo1 was similar to higher vertebrates in that it regulated the motility of neutrophils through the Rac proteins. Therefore, we believe that elmo1 mutant zebrafish can serve as a valuable tool for the in vivo functional verification of human ELMO1 variants. We first verified whether human ELMO1 could rescue the reduced neutrophil motility in zebrafish elmo1 mutant by transiently expressing the human ELMO1-GFP fusion protein. The migration of neutrophils expressing human ELMO1 was recorded using time-lapse live imaging. As expected, the expression of wild-type human ELMO1 (hu-WT) effectively rescued the impaired motility of elmo1 mutant neutrophils, indicating the conservative role of human ELMO1 in zebrafish (Figures 6B,C,G; Supplementary Video S4). Therefore, elmo1 mutant zebrafish could be used to verify human variants.

FIGURE 6. The zebrafish elmo1 mutant can serve as an in vivo model to verify the functions of human variants. (A) Schematic view of human ELMO1 protein conserved domains. Position of tested variants: p.E90K (E90K), p.D194G (D194G), and p.R354X (R354X) are indicated. (B–F) Track path of neutrophils expressing lyz:GFP control (B) or human ELMO1 (C–F) in the elmo1−/− and siblings recorded by live imaging at 3 dpf. Human wild-type (hu-WT) form (C), E90K (D), D194G (E), R354X (F). (G, H) Quantification of the migration speed of the control group and neutrophils expressing human ELMO1 variants in the elmo1−/− (7 cells of 3 larvae, 20 cells of 6 larvae, 16 cells of 6 larvae, 8 cells of 6 larvae, 7 cells of 3 larvae) (G) and sibling (15 cells of 3 larvae, 16 cells of 7 larvae, 12 cells of 8 larvae, 14 cells of 7 larvae, 10 cells of 5 larvae). (H). hu-WT, E90K, and D194G could efficiently rescue the migration speed in the elmo1 mutant compared with control. R354X failed to rescue the defects in elmo1−/− and even show a decreased migration speed in siblings. One-way ANOVA, ns: no significance, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.001. Scale bar: 50 μm (B–F).

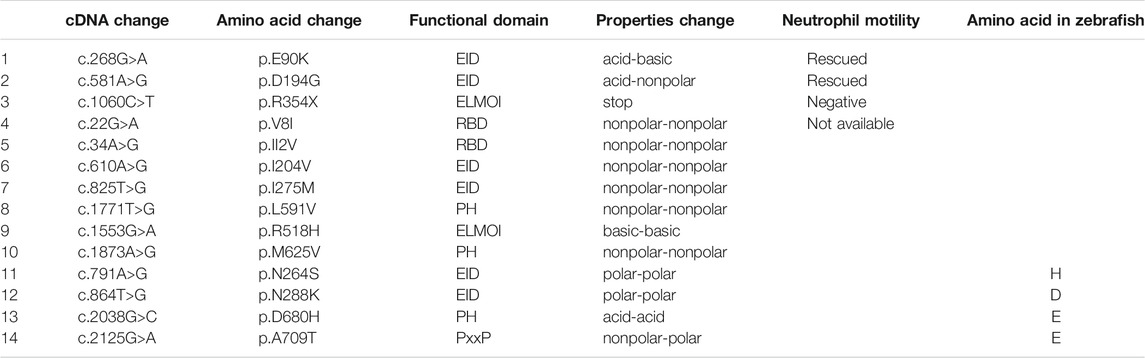

We next identified fourteen novel non-synonymous variants in the coding region of the human ELMO1 gene from the GuangZhou KingMed Center For Clinical Laboratory Co., Ltd genetics database (Table 1). Based on the conservation of amino acids, we excluded four variants in which the amino acids differed between human and zebrafish. Furthermore, eight variants were excluded because their amino acid properties were not significantly changed. Of the remaining three variants, p.E90K (c.268G>A) and p.D194G (c.581A>G) changed the amino acid properties, whereas p.R354X (c.1060C>T) resulted in a premature stop codon prior to the PH domain, which interacts with the DOCK protein (Figure 6A). To verify the functional changes of p.E90K, p.D194G, and p.R354X in vivo, we transiently expressed human ELMO1 carrying these variants in neutrophils. The ELMO1-positive neutrophils were visualized using GFP, which was directly fused to ELMO1. The migration paths of neutrophils were recorded using live imaging and the migration speeds were calculated. Compared with the control group (Figures 6B,G), p.E90K and p.D194G (Figures 6D,E,G; Supplementary Video S4) could effectively restore the migration speed of elmo1−/− larvae, while p.R354X (Figures 6F,G) failed to do so. Interestingly, the transient expression of p.R354X also significantly reduced the migration speed of neutrophils in siblings (Figures 6F,H; Supplementary Video S5).

TABLE 1. Informations of the human ELMO1 variants. Here list the identified fourteen novel non-synonymous variants in the coding region of the human ELMO1 gene found from the KingMed Diagnostics Group genetics database. (1–10) List the variants in which amino acids are conserved between human and zebrafish. (1–3) p.E90K (c.268G>A) and p.D194G (c.581A>G) changed the amino acid properties, whereas p.R354X (c.1060C>T) resulted in a premature stop codon prior to the pH domain, which interacts with the DOCK protein. (11–14) List the variants in which amino acids are conserved between human and zebrafish.

As a member of the ELMO1-DOCK2 protein complex, it is known that DOCK2 deficiency can lead to inherent immunodeficiency diseases in the human population, whereas genetic polymorphism studies have shown that ELMO1 variants are associated with autoimmune diseases. In mice arthritis model induced by K/BxN serum or collagen, Elmo1 deficiency can relieve the inflammatory response and cause a better outcome of the disease by reducing the accumulation of neutrophils (Arandjelovic et al., 2019). This study gave us a hint that elmo1 gene function on regulating the chemotaxis of neutrophils and even other immune cells. So far, most of the works have been done under pathological conditions such as diabetes, bowl inflammation, and RA in the mice model (Arandjelovic et al., 2019; Das et al., 2015; Hathaway et al., 2016). These results indicate that ELMO1 affects the motility of immune cells. In our study, we used the zebrafish model to directly observe the behavior of immune cells affected by Elmo1 through in vivo live imaging under physiological conditions. Consistent with previous studies about the ELMO1 participated in regulating cell migration in mice and cell culture (Gumienny et al., 2001; Grimsley et al., 2004; Arandjelovic et al., 2019), we found that the random ameboid migration of neutrophils and T-cells were significantly reduced in elmo1−/− larvae, and the chemotaxis of neutrophils was also reduced after injury or infection in elmo1−/− larvae by in vivo live imaging (Figure 2, Figure3). Consistent with Mikdache’s report in which macrophage activity in the elmo1 mutant was found normal in the Posterior Lateral Line ganglion, we also found that the motility of macrophage showed no differences between sibling and elmo1−/− larvae at 3 dpf (Mikdache et al., 2020). Although, in elmo1 morphant, macrophages showed abnormal morphology in the brain at 48 hpf and failed to engulf apoptotic cells in elmo1 knock-down embryos (van Ham et al., 2012), we have observed that macrophages showed normal morphology in elmo1 mutant embryos on the yolk. The inconsistency between the morphants and mutants is possibly due to the nonspecific effects of morpholino. Alternatively, a genetic compensation response could be provoked in mutant macrophages (Rossi et al., 2015). It warrants further study to distinguish which possibility is true. However, no patients carried ELMO1 bi-allele mutation have been reported yet. Whether ELMO1 mutation could lead to immunodeficiency in human warrants further study.

Racs have been reported works as the downstream of DOCK-ELMO1 complex in regulating cell motility (Brugnera et al., 2002; Epting et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2020; Mutsuko Kukimoto-Niino et al., 2021). It is known that, in the case of ELMO1-DOCK2-RAC1, RAC1 directly bind to the DHR2 domain of the DOCK2 protein (Chang et al., 2020). Interestingly, Mutsuko Kukimoto-Niino et al. reported that RAC1 could also interacted with the PH domain on the ELMO1, by which, the PH domain of ELMO1 stabilizes the transition state of the DOCK5 (DHR-2)–Rac1 complex, providing the structural basis for ELMO1-mediated enhancement of the catalytic activity of DOCK5 (Mutsuko Kukimoto-Niino et al., 2021). As expected, the Rac activity was disrupted in elmo1−/− larvae. (Supplementary Figures S5A–C). Whether the Racs activity in neutrophils is regulated via Dock proteins or directly by Elmo1 remains to be clarified. We found that in addition to constitutively activated Rac1a, constitutively activated Rac2 could also effectively rescued the motility defects of neutrophils in elmo1 mutants; thus, suggesting that Racs functioned downstream of Elmo1 in zebrafish. More importantly, human ELMO1 could also rescue the defective motility phenotype of mutant neutrophils in zebrafish. These results indicated that elmo1 acted through a conserved mechanism in zebrafish (Stevenson et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2020); thus, supporting the use of zebrafish as a suitable animal model for identifying functional changes in human ELMO1 variants.

We performed live imaging on transparent zebrafish larvae to verify the function of the human ELMO1 variant of neutrophil motility. This assay also provided us a unique opportunity to directly observe the function of ELMO1 variants in vivo. For the three ELMO1 variants chosen for analysis, p.E90K and p.D194G variants were located in the conserved ELMO inhibitory domain (EID). However, they were not on the ELMO1-DOCK2 interface or the interface with any other known partner of ELMO1, such as RhoG1 or BAI1 (Katoh and Negishi, 2003; Park et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that these two variants may not substantially interfere with the function of ELMO1. Indeed, these two variants successfully rescued the abnormal neutrophil motility of elmo1 mutant zebrafish. The remaining variant, p.R354X (c.1060C>T), resulted in a stop codon prior to the PH domain, which interacted with the DOCK or RAC, suggesting that it would fail to regulate downstream effecter activities. As expected, the p.R354X variant could not recover the migration speed of neutrophils in the elmo1 mutant. Interestingly, this variant also impaired the migration of neutrophils in siblings. We hypothesized that the transiently expressed p.R354X variant may outcompete wild-type ELMO1 for its N-terminal binding partners, including RhoG and BAI1, under over-expression condition. Consequently, the function of wild-type ELMO1 was attenuated in such zebrafish.

Although zebrafish provide a quick and convenient model for testing ELMO1 variants in vivo, we also observed that the transient expression of variants in zebrafish had limitations. For example, we expressed ELMO1 variants under the control of the lyz promoter, which may lead to higher concentrations of ELMO1 variant proteins in neutrophils than physiological conditions. This may, in turn, cause excessive activation or inhibition of ELMO1. To overcome this challenge, we may use the endogenous elmo1 promoter instead of the lyz promoter to drive the expression of ELMO1 variants. Large-scale clinical analyses with in vivo functional studies of ELMO1 variants should also be combined to better understand the physiological or pathological roles of such variants.

In summary, we found that zebrafish elmo1 gene functioned in a conserved way in neutrophils. With the zebrafish elmo1 mutant, we have established a convenient in vivo model for the effective analysis of human ELMO1 variants. This model could facilitate the characterization of ELMO1 variants and provide valuable suggestions for clinical decision-making. Similar methods could also be applied in zebrafish to in vivo evaluations of genetic variants of other genes.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI [accession: SRR16351675, SRR16351676, SRR16351677].

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of GuangZhou KingMed Center For Clinical Laboratory CO.,Ltd. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Ethical review and approval was not required for the animal study because we use the zebrafish as the animal model.

Conceptualization: RX and JX; Data curation: RX and GM; Formal Analysis, RX, and YW; Funding Acquisition, QL, JX, and SY; Investigation: RX, YW, TW, ML, and JL; Resources, RX, GM, XF, and JX; Visualization, RX and JX; Writing-original draft: RX; Writing-review and editing: JX and QL; Supervision, JX, QL, KY, and SY.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771594; 31970763; 81770190), the National Key Research and Development Programs (2018YFA0800200; 2017YFA105500; 2017YFA105504), the Guangdong Science and Technology Plan projects (2019A030317001), and the Program for Entrepreneurial and Innovative Leading Talents of Guangzhou, China (CXLJTD- 201603).

TW was employed by the Beigene Ltd. and GM, XF, and SY were employed by the company GuangZhou KingMed Center For Clinical Laboratory Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Zilong WEN (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China) for sharing the GFP positive E.coli, Tg(globin:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP), Tg(lck:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP), and Tg(mpeg1:LoxP-DsRedx-LoxP-GFP). We thank M.D. Michiyuki Matsuda (Laboratory of Bioimaging and Cell Signaling, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Janpa) for the kindly sharing the Raichu-Rac1 plasmid.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.723804/full#supplementary-material

Aoki, K., and Matsuda, M. (2009). Visualization of Small GTPase Activity with Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Biosensors. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1623–1631. doi:10.1038/nprot.2009.175

Arandjelovic, S., Perry, J. S. A., Lucas, C. D., Penberthy, K. K., Kim, T.-H., Zhou, M., et al. (2019). A Noncanonical Role for the Engulfment Gene ELMO1 in Neutrophils that Promotes Inflammatory Arthritis. Nat. Immunol. 20, 141–151. doi:10.1038/s41590-018-0293-x

Barresi, M. J., Stickney, H. L., and Devoto, S. H. (2000). The Zebrafish Slow-Muscle-Omitted Gene Product Is Required for Hedgehog Signal Transduction and the Development of Slow Muscle Identity. Development 127, 2189–2199. doi:10.1242/dev.127.10.2189

Bayoumy, N. M. K., El-Shabrawi, M. M., Leheta, O. F., Abo El-Ela, A. E. M., and Omar, H. H. (2020). Association of ELMO1 Gene Polymorphism and Diabetic Nephropathy Among Egyptian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 36, e3299. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3299

Bosch, M., and Kardash, E. (2019). In Vivo Quantification of Intramolecular FRET Using RacFRET Biosensors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2040, 275–297. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-9686-5_13

Brugnera, E., Haney, L., Grimsley, C., Lu, M., Walk, S. F., Tosello-Trampont, A.-C., et al. (2002). Unconventional Rac-GEF Activity Is Mediated through the Dock180-ELMO Complex. Nat. Cel Biol 4, 574–582. doi:10.1038/ncb824

Capala, M. E., Vellenga, E., and Schuringa, J. J. (2014). ELMO1 is Upregulated in AML CD34+ Stem/Progenitor Cells, Mediates Chemotaxis and Predicts Poor Prognosis in Normal Karyotype AML. PLoS One 9, e111568.

Chang, L., Yang, J., Jo, C. H., Boland, A., Zhang, Z., Mclaughlin, S. H., et al. (2020). Structure of the DOCK2−ELMO1 Complex Provides Insights into Regulation of the Auto-Inhibited State. Nat. Commun. 11, 3464. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17271-9

Das, S., Sarkar, A., Choudhury, S. S., Owen, K. A., Derr-Castillo, V. L., Fox, S., et al. (2015). Engulfment and Cell Motility Protein 1 (ELMO1) Has an Essential Role in the Internalization of Salmonella Typhimurium into Enteric Macrophages that Impact Disease Outcome. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1, 311–324. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.02.003

Dobbs, K., Domínguez Conde, C., Zhang, S.-Y., Parolini, S., Audry, M., Chou, J., et al. (2015). Inherited DOCK2 Deficiency in Patients with Early-Onset Invasive Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2409–2422. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1413462

Dooley, K., and Zon, L. I. (2000). Zebrafish: a Model System for the Study of Human Disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 252–256. doi:10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00074-5

Epting, D., Slanchev, K., Boehlke, C., Hoff, S., Loges, N. T., Yasunaga, T., et al. (2015). The Rac1 Regulator ELMO Controls Basal Body Migration and Docking in Multiciliated Cells through Interaction with Ezrin. Development 142, 1553. doi:10.1242/dev.124214

Epting, D., Wendik, B., Bennewitz, K., Dietz, C. T., Driever, W., and Kroll, J. (2010). The Rac1 Regulator ELMO1 Controls Vascular Morphogenesis in Zebrafish. Circ. Res. 107, 45–55. doi:10.1161/circresaha.109.213983

Farnsworth, D. R., Saunders, L. M., and Miller, A. C. (2020). A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas for Zebrafish Development. Dev. Biol. 459, 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.11.008

Federici, G., and Soddu, S. (2020). Variants of Uncertain Significance in the Era of High-Throughput Genome Sequencing: a Lesson from Breast and Ovary Cancers. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39, 46. doi:10.1186/s13046-020-01554-6

Gong, P., Chen, S., Zhang, L., Hu, Y., Gu, A., Zhang, J., et al. (2018). RhoG-ELMO1-RAC1 Is Involved in Phagocytosis Suppressed by Mono-Butyl Phthalate in TM4 Cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 35440–35450. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3503-z

Grimsley, C. M., Kinchen, J. M., Tosello-Trampont, A.-C., Brugnera, E., Haney, L. B., Lu, M., et al. (2004). Dock180 and ELMO1 Proteins Cooperate to Promote Evolutionarily Conserved Rac-dependent Cell Migration. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6087–6097. doi:10.1074/jbc.m307087200

Gumienny, T. L., Brugnera, E., Tosello-Trampont, A. C., Kinchen, J. M., Haney, L. B., Nishiwaki, K., et al. (2001). CED-12/ELMO, a Novel Member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac Pathway, is Required for Phagocytosis and Cell Migration. Cell 107, 27–41.

Harvie, E. A., and Huttenlocher, A. (2015). Neutrophils in Host Defense: New Insights from Zebrafish. J. Leukoc. Biol. 98, 523–537. doi:10.1189/jlb.4mr1114-524r

Hathaway, C. K., Chang, A. S., Grant, R., Kim, H.-S., Madden, V. J., Bagnell, C. R., et al. (2016). High Elmo1 Expression Aggravates and Low Elmo1 Expression Prevents Diabetic Nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2218–2222. doi:10.1073/pnas.1600511113

Hayashi, K., Teramoto, R., Nomura, A., Asano, Y., Beerens, M., Kurata, Y., et al. (2020). Impact of Functional Studies on Exome Sequence Variant Interpretation in Early-Onset Cardiac Conduction System Diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 2116–2130. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa010

Hu, Z., Liu, Y., Huarng, M. C., Menegatti, M., Reyon, D., Rost, M. S., et al. (2017). Genome Editing of Factor X in Zebrafish Reveals Unexpected Tolerance of Severe Defects in the Common Pathway. Blood 130, 666–676. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-02-765206

Itoh, R. E., Kurokawa, K., Ohba, Y., Yoshizaki, H., Mochizuki, N., and Matsuda, M. (2002). Activation of Rac and Cdc42 Video Imaged by Fluorescent Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Single-Molecule Probes in the Membrane of Living Cells. Mol. Cel Biol 22, 6582–6591. doi:10.1128/mcb.22.18.6582-6591.2002

Janardhan, A., Swigut, T., Hill, B., Myers, M. P., and Skowronski, J. (2004). HIV-1 Nef Binds the DOCK2-ELMO1 Complex to Activate Rac and Inhibit Lymphocyte Chemotaxis. Plos Biol. 2, E6. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020006

Jiang, J., Liu, G., Miao, X., Hua, S., and Zhong, D. (2011). Overexpression of Engulfment and Cell Motility 1 Promotes Cell Invasion and Migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2, 505–511.

Jin, H., Xu, J., Qian, F., Du, L., Tan, C. Y., Lin, Z., et al. (2006). The 5′ Zebrafishscl Promoter Targets Transcription to the Brain, Spinal Cord, and Hematopoietic and Endothelial Progenitors. Dev. Dyn. 235, 60–67. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20613

Katoh, H., Fujimoto, S., Ishida, C., Ishikawa, Y., and Negishi, M. (2006). Differential Distribution of ELMO1 and ELMO2 mRNAs in the Developing Mouse brainGenetic Variations in the Gene Encoding ELMO1 Are Associated with Susceptibility to Diabetic Nephropathy. BRAIN RESEARCH 1073-1074, 103–108. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.085

Katoh, H., and Negishi, M. (2003). RhoG Activates Rac1 by Direct Interaction with the Dock180-Binding Protein Elmo. Nature 424, 461–464. doi:10.1038/nature01817

Kimmel, C. B., Kimmel, W. W. B., Ballard, W. W., Kimmel, S. R., and Schilling, T. F. (1995). Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310. doi:10.1002/aja.1002030302

Kitaguchi, T., Kawakami, K., and Kawahara, A. (2009). Transcriptional Regulation of a Myeloid-Lineage Specific Gene Lysozyme C during Zebrafish Myelopoiesis. Mech. Dev. 126, 314–323. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2009.02.007

Langenau, D. M., Ferrando, A. A., Traver, D., Kutok, J. L., Hezel, J.-P. D., Kanki, J. P., et al. (2004). In Vivo tracking of T Cell Development, Ablation, and Engraftment in Transgenic Zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 7369–7374. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402248101

Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2010). Fast and Accurate Long-Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698

Li, L., Yan, B., Shi, Y.-Q., Zhang, W.-Q., and Wen, Z.-L. (2012). Live Imaging Reveals Differing Roles of Macrophages and Neutrophils during Zebrafish Tail Fin Regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25353–25360. doi:10.1074/jbc.m112.349126

Lin, X., Zhou, Q., Zhao, C., Lin, G., Xu, J., and Wen, Z. (2019). An Ectoderm-Derived Myeloid-like Cell Population Functions as Antigen Transporters for Langerhans Cells in Zebrafish Epidermis. Dev. Cel 49, 605–617. e605. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2019.03.028

Mikdache, A., Fontenas, L., Albadri, S., Revenu, C., Loisel-Duwattez, J., Lesport, E., et al. (2020). Elmo1 Function, Linked to Rac1 Activity, Regulates Peripheral Neuronal Numbers and Myelination in Zebrafish. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 77, 161–177. doi:10.1007/s00018-019-03167-5

Moore, F. E., Moore, D. R., Sander, R. D., Martinez, Sarah. A., Blackburn, Jessica. S., Cyd, K., et al. (2012). Improved Somatic Mutagenesis in Zebrafish Using Transcription Activator-like Effector Nucleases (TALENs). PLoS One 7, e37877. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037877

Mulloy, J. C., Cancelas, J. A., Filippi, M.-D., Kalfa, T. A., Guo, F., and Zheng, Y. (2010). Rho GTPases in Hematopoiesis and Hemopathies. Blood 115, 936–947. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-09-198127

Mutsuko Kukimoto-Niino, K. K., Kaushik, Rahul., Ehara, Haruhiko., Yokoyama, Takeshi., Uchikubo-Kamo, Tomomi., Nakagawa, Reiko., et al. (2021). Cryo-EM Structure of the Human ELMO1-DOCK5-Rac1 Complex. SCIENCE ADVANCES 7, eabg3147. doi:10.2210/pdb7dpa/pdb

Nguyen-Chi, M., Phan, Q. T., Gonzalez, C., Dubremetz, J.-F., Levraud, J.-P., and Lutfalla, G. (2014). Transient Infection of the Zebrafish Notochord with E. coli Induces Chronic Inflammation. Dis. Model. Mech. 7, 871–882. doi:10.1242/dmm.014498

Nishida, K., Kaziro, Y., and Satoh, T. (1999). Anti-apoptotic Function of Rac in Hematopoietic Cells. Oncogene 18, 407–415. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202301

Olson, E. J., Hartsough, L. A., Landry, B. P., Shroff, R., and Tabor, J. J. (2014). Characterizing Bacterial Gene Circuit Dynamics with Optically Programmed Gene Expression Signals. Nat. Methods 11, 449–455. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2884

Park, D., Tosello-Trampont, A.-C., Elliott, M. R., Lu, M., Haney, L. B., Ma, Z., et al. (2007). Bai1 Is an Engulfment Receptor for Apoptotic Cells Upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac Module. Nature 450, 430–434. doi:10.1038/nature06329

Park, Y. L., Choi, J. H., Park, S. Y., Oh, H. H., Kim, D. H., Seo, Y. L., et al. (2020). Engulfment and Cell Motility 1 Promotes Tumor Progression Via the Modulation of Tumor Cell Survival in Gastric Cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 12, 7797–7811.

Patel, A., Kostyak, J., Dangelmaier, C., Badolia, R., Bhavanasi, D., Aslan, J. E., et al. (2019). ELMO1 Deficiency Enhances Platelet Function. Blood Adv. 3, 575–587. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018016444

Rossi, A., Kontarakis, Z., Gerri, C., Nolte, H., Hölper, S., Krüger, M., et al. (2015). Genetic Compensation Induced by Deleterious Mutations but Not Gene Knockdowns. Nature 524, 230–233. doi:10.1038/nature14580

Sarkar, A., Tindle, C., Pranadinata, R. F., Reed, S., Eckmann, L., Stappenbeck, T. S., et al. (2017). ELMO1 Regulates Autophagy Induction and Bacterial Clearance during Enteric Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 216, 1655–1666. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix528

Sharma, K. R., Heckler, K., Stoll, S. J., Hillebrands, J.-L., Kynast, K., Herpel, E., et al. (2016). ELMO1 Protects Renal Structure and Ultrafiltration in Kidney Development and under Diabetic Conditions. Sci. Rep. 6, 37172. doi:10.1038/srep37172

Stevenson, C., De La Rosa, G., Anderson, C. S., Murphy, P. S., Capece, T., Kim, M., et al. (2014). Essential Role of Elmo1 in Dock2-dependent Lymphocyte Migration. J.I. 192, 6062–6070. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1303348

Thisse, C., and Thisse, B. (2008). High-resolution In Situ Hybridization to Whole-Mount Zebrafish Embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59–69. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.514

Tian, Y., Xu, J., Feng, S., He, S., Zhao, S., Zhu, L., et al. (2017). The First Wave of T Lymphopoiesis in Zebrafish Arises from Aorta Endothelium Independent of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3347–3360. doi:10.1084/jem.20170488

Van Ham, T. J., Kokel, D., and Peterson, R. T. (2012). Apoptotic Cells Are Cleared by Directional Migration and Elmo1- Dependent Macrophage Engulfment. Curr. Biol. 22, 830–836. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.027

Wang, L., and Zheng, Y. (2007). Cell Type-specific Functions of Rho GTPases Revealed by Gene Targeting in Mice. Trends Cel Biol. 17, 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.009

Xu, J., Wang, T., Wu, Y., Jin, W., and Wen, Z. (2016). Microglia Colonization of Developing Zebrafish Midbrain Is Promoted by Apoptotic Neuron and Lysophosphatidylcholine. Dev. Cel 38, 214–222. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.018

Yang, Y., Muzny, D. M., Reid, J. G., Bainbridge, M. N., Willis, A., Ward, P. A., et al. (2013). Clinical Whole-Exome Sequencing for the Diagnosis of Mendelian Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1502–1511. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1306555

Keywords: ELMO1, neutrophil, variants, cell motility, zebrafish

Citation: Xue R, Wang Y, Wang T, Lyu M, Mo G, Fan X, Li J, Yen K, Yu S, Liu Q and Xu J (2021) Functional Verification of Novel ELMO1 Variants by Live Imaging in Zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:723804. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.723804

Received: 11 June 2021; Accepted: 17 November 2021;

Published: 21 December 2021.

Edited by:

Anskar Y.H. Leung, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Zhihao Jia, Purdue University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Xue, Wang, Wang, Lyu, Mo, Fan, Li, Yen, Yu, Liu and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kuangyu Yen, a3Vhbmd5dXllbkBzbXUuZWR1LmNu; Shihui Yu, emIteXVzaGlodWlAa2luZ21lZC5jb20uY24=; Qifa Liu, bGl1cWlmYTYyOEAxNjMuY29t; Jin Xu, eHVqaW5Ac2N1dC5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.