- 1Department of Human Anatomy and Histoembryology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 2Institutes of Brain Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Medical Imaging Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention of Shanghai, Shanghai, China

Patients with monoallelic bromodomain and PHD finger-containing protein 1 (BRPF1) mutations showed intellectual disability. The hippocampus has essential roles in learning and memory. Our previous work indicated that Brpf1 was specifically and strongly expressed in the hippocampus from the perinatal period to adulthood. We hypothesized that mouse Brpf1 plays critical roles in the morphology and function of hippocampal neurons, and its deficiency leads to learning and memory deficits. To test this, we performed immunofluorescence, whole-cell patch clamp, and mRNA-Seq on shBrpf1-infected primary cultured hippocampal neurons to study the effect of Brpf1 knockdown on neuronal morphology, electrophysiological characteristics, and gene regulation. In addition, we performed stereotactic injection into adult mouse hippocampus to knock down Brpf1 in vivo and examined the learning and memory ability by Morris water maze. We found that mild knockdown of Brpf1 reduced mEPSC frequency of cultured hippocampal neurons, before any significant changes of dendritic morphology showed. We also found that Brpf1 mild knockdown in the hippocampus showed a decreasing trend on the spatial learning and memory ability of mice. Finally, mRNA-Seq analyses showed that genes related to learning, memory, and synaptic transmission (such as C1ql1, Gpr17, Htr1d, Glra1, Cxcl10, and Grin2a) were dysregulated upon Brpf1 knockdown. Our results showed that Brpf1 mild knockdown attenuated hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission and reduced spatial learning and memory ability, which helps explain the symptoms of patients with BRPF1 mutations.

Introduction

Intellectual disability is a prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 1–2% of children or young adults. Over 1,396 genes have been implicated in intellectual disability (Ilyas et al., 2020). Bromodomain and PHD finger-containing protein 1 (BRPF1) is an important candidate gene with its monoallelic mutations resulting in intellectual disability (Mattioli et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017; Demeulenaere et al., 2019; Pode-Shakked et al., 2019), but the exact underlying mechanism remains unclear.

BRPF1 is a chromatin regulator with multiple modules, including double PHD fingers (recognizing the N-terminal tail of histone H3) (Poplawski et al., 2014; Klein et al., 2016), a bromodomain (with acetyl-lysine-binding ability) (Lubula et al., 2014b), and a PWWP domain (forming a specific pocket for trimethylated histone H3) (Vezzoli et al., 2010). BRPF1 acts as a scaffold to promote the binding of transcription factors to the acetyltransferase MOZ/MORF and activate acetylation of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Lubula et al., 2014a). The cumulative number of patients with BRPF1 mutations has reached 40, and patients were often accompanied with symptoms such as epilepsy, hypotonia, developmental delay, language dysfunction, ptosis, and cerebellar and facial deformities (Mattioli et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017, 2020; Demeulenaere et al., 2019; Pode-Shakked et al., 2019). The expression level of BRPF1 was positively correlated with the volume of hippocampal CA2, CA3, and dentate gyrus (Zhao et al., 2019). Our previous studies indicated that mouse Brpf1 is strongly and specifically expressed in the hippocampus during fetal, neonatal, and adult stages (You et al., 2014, 2015a). Similarly, in human, BRPF1 is also stably expressed in the hippocampus from development to adulthood by BrainSpan Atlas, a transcriptional resource of the developing human brain (Zhao et al., 2019).

Our previous studies showed that homozygous deletion of Brpf1 led to embryonic lethality, and one of the defects was in neural tube closure (You et al., 2014, 2015a). Forebrain-specific deletion of mouse Brpf1 resulted in early postnatal lethality with neocortical abnormalities and partial agenesis of the hippocampus and corpus callosum (You et al., 2015b,c). Another group showed that forebrain-specific heterozygous deletion of Brpf1 exhibited decreased the ability of learning and memory and reduced the dendritic complexity and density of spinous processes (Su et al., 2019).

The hippocampus has essential roles in learning and memory. CA1 pyramidal neurons play an important role in long-term memory and spatial-related tasks (Ferguson et al., 2004). Our previous study showed that Brpf1 was specifically and strongly expressed in the hippocampus, especially CA1 and dentate gyrus (You et al., 2015b). We hypothesized that Brpf1 regulates the morphology and function of hippocampal neurons, and dysfunction of Brpf1 eventually leads to impaired learning and memory. In this study, we examined the effect of Brpf1 knockdown on neuronal morphology, electrophysiological characteristics, and gene regulation by immunofluorescence, whole-cell patch clamp, and mRNA-Seq, respectively, using shRNA-infected primary cultured hippocampal neurons. In addition, we evaluated the impact of Brpf1 deficiency on learning and memory ability by Morris water maze using shRNA stereotactic injection into adult mouse hippocampus. Our findings indicated that Brpf1 mild knockdown attenuated hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission and reduced spatial learning and memory ability, which helps explain the symptoms of patients with BRPF1 mutations.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All mice used were of C57BL/6 background purchased from Jiesijie lab (Shanghai, China). Animals were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. The day when vaginal plug is detected was considered to be embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). All animal experiments were approved by the local committees of the guidelines of the laboratory animals at Fudan University (Shanghai, China).

Hippocampal Primary Neuronal Cultures and Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Infection

Primary hippocampal neurons were generated from E17.5 to E18.5 mouse embryos as described previously (Beaudoin et al., 2012). Briefly, hippocampi from E17.5 to E18.5 embryos were dissected in HBSS and dissociated in 0.25% of trypsin. The dissociated cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated 24-well plates with neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 supplement (17504044, Gibco, New York, NY, United States). Media were changed twice a week. To knock down Brpf1, cultured neurons at days in vitro (DIV) 3 were infected with either AAV2-scramble-green fluorescent protein (GFP) or AAV2-shBrpf1-GFP purchased from BrainVTA (Wuhan, China). The sense sequence of shBrpf1 is GGCTTACCGCTACTTGAACTT. Media were replaced after 12 h. Experiments using primary cultured neurons were performed at DIV 14–15. Neurons were grown at 37∘C and with 5% CO2.

Stereotactic Viral Vector Delivery

4-week-old mice were fixed on a stereotactic device and anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation during the surgery. AAV2-scramble-GFP and AAV2-shBrpf1-GFP were injected into the left and right hippocampal CA1 through a glass micropipette at a rate of 0.02 μl/min, respectively. The total volume of AAVs injected into each hemisphere was 0.2 μl. The glass microelectrode was kept in the CA1 for 5 min to allow the AAVs to spread. The stereotactic coordinates of CA1 are anterior–posterior to bregma: –1.8 mm, middle-lateral to middle line: ± 1.2 mm, dorsal-ventral to cerebral dura mater: ± 1.2 mm. The mice then underwent behavioral or molecular experiments 4 weeks after operation.

Morris Water Maze

Mice after stereotactic operation were introduced into a circular water-filled tank 120 cm in diameter with visual cues that were present on the tank walls as spatial references. The temperature of water was maintained at 22.0°C, and white non-toxic paint was used to make the water turbid and opaque. The tank was divided into northwest (NW), northeast (NE), southwest (SW), and southeast (SE) quadrants by lines. A round platform with 10 cm of diameter was submerged 1 cm deep in the tank. On day 1, mice were put in a room for at least 30 min to be familiar with the environment before training. Each mouse was put gently into the water with the head faced to the wall of the tank during training, given 60 s to find the platform, and allowed to stay on the platform for 15 s when the mouse reached the platform. The experimenter guided it to the platform and let it stay on the platform for 15 s if the mouse could not find the platform within 60 s. Each mouse received four trials daily from four different quadrants. On day 8, the mice were subject to a single 60-s probe trial without a platform to test memory retention. EthoVision (Noldus, Wageningen, Netherlands) was used to track the mice and analyze the data.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Analysis of Dendritic Morphology

Neurons on coverslips were fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, blocked with 5% of goat serum and 0.1% of Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h, incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-MAP2 (67015-1-ig, 1:2,000, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and rabbit anti-GFP (Proteintech, 50430-2-AP, 1:500), and then incubated with Alexa fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit 488 and goat anti-mouse 594) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the neurons were counterstained with DAPI (2 μg/ml) for 5 min and mounted with fluorescence mounting medium. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Leica SP8) and analyzed by ImageJ Fiji. Sholl analysis was applied to calculate the branches and the total length of dendrites (O’Neill et al., 2015).

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured hippocampal neurons or hippocampal CA1 tissue by the TRIzol method. 500 ng of RNA of each sample was used for reverse transcription with Evo M-MLV RT Kit with gDNA Clean (Accurate Biotechnology, Hunan, China, AG11705). The resulting cDNA was used as a template for RT-qPCR using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Shiga, Japan, rr420a). GAPDH was used as the internal control, and the relative expression of the gene was calculated by the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The primer list is summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA Sequencing and Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from three pairs of primary cultured hippocampal neurons and three pairs of stereotactic injected CA1 tissues with RIN values of more than 9. The samples were subject to high-throughput mRNA sequencing through paired-end mode with the Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform. For data analysis, the preprocessing sequence was compared with the mouse genome (release-98) by STAR software after removing the linker and low-quality fragments. StringTie software was used to count the original sequence counts of known genes, and the expression of known genes was calculated using fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM). The DESeq2 software was applied to screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different groups [log2 (fold change) ≥ 1 or ≤ –1 and p-value < 0.05 was used]. The function of DEGs was analyzed by the David platform (Huang Da et al., 2009a,b), including gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). The raw and processed data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database with GEO# GSE174600.

Electrophysiology Recording and Analysis

For whole-cell patch-clamp recording, neurons were infected with a reduced titer of AAV2-scramble-GFP or AAV2-shBrpf1-GFP at DIV3 to achieve sparse labeling, and the recordings were performed at DIV15. Whole-cell recordings were conducted with a conventional patch-clamp technique with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA, United States). Patch pipettes were pulled by a Sutter P-97 pipette puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, United States). The bath solution (pH = 7.3) contained 128 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 30 mM glucose, and 2 mM CaCl2. Recording pipettes were filled with an internal solution (pH = 7.2–7.3) containing 125 mM potassium gluconate, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Tris–phosphocreatine, 4 mM MgATP, and 0.5 mM Na2GTP. All the recordings were performed at room temperature. Data acquisition and analysis were performed with pClamp 10.2 software (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA, United States).

Statistics

For two-group comparisons, two-tailed and unpaired Student’s t-tests were performed. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 7 software (GraphPad). The value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Results

Fifty Percent Knockdown of Brpf1 Did Not Significantly Change the Dendritic Length and Number of Intersections in vitro

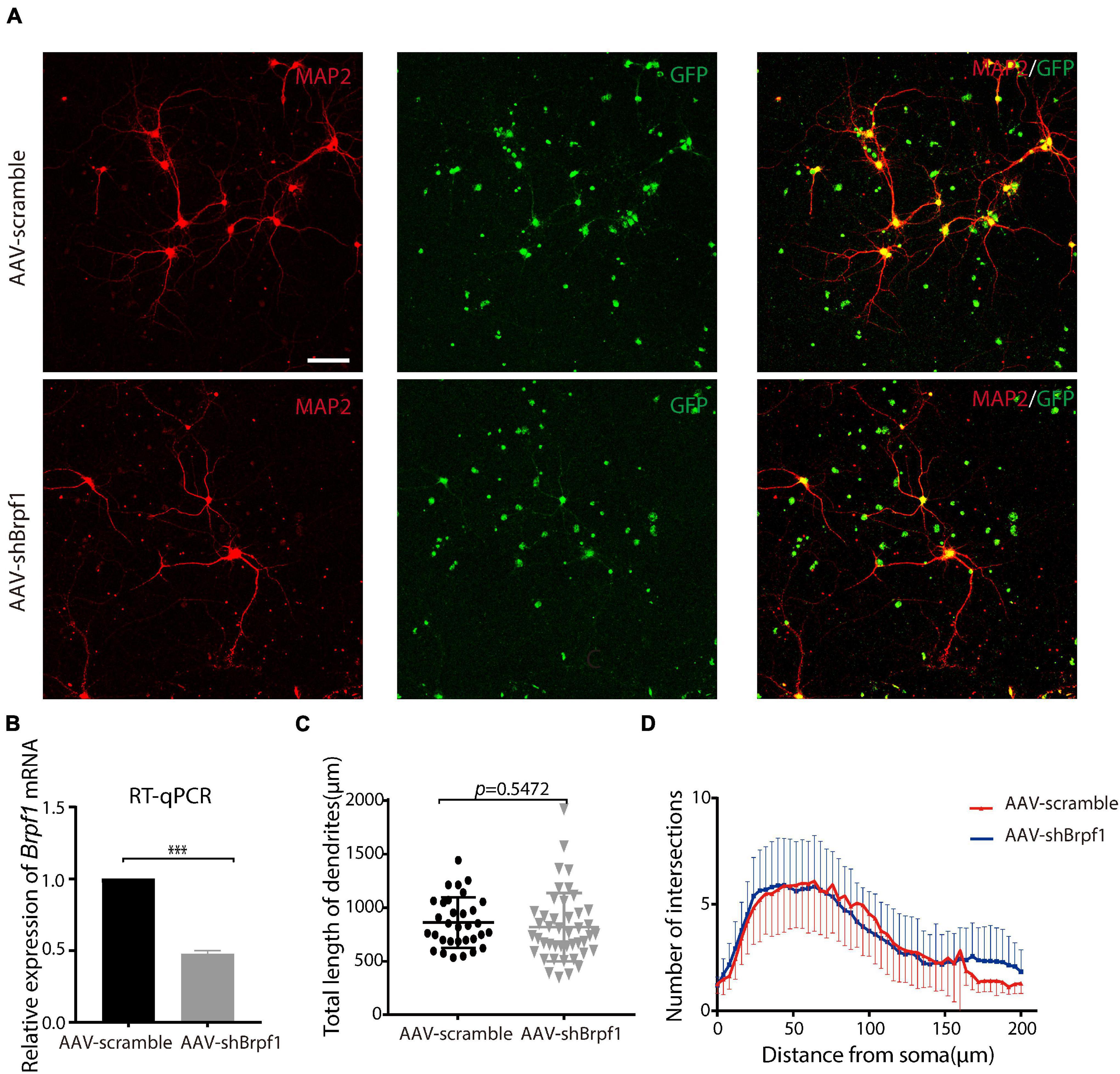

Neurons have unique dendritic-like structures, which play an important role in signal transmission. To study the effect of Brpf1 knockdown on the dendritic morphology of hippocampal neurons, we dissociated E17.5–E18.5 hippocampi and infected primary cultured neurons with AAV2-scramble-GFP or AAV2-shBrpf1-GFP at DIV3. Immunostaining was performed at DIV 14–15 with anti-MAP2 antibody (a specific marker for dendrites), and the quantification of dendritic morphology was calculated from three independent experiments using Sholl analysis (O’Neill et al., 2015); totally 32 and 44 neurons in the scramble and shBrpf1 groups were analyzed, respectively (Figure 1A). We confirmed a knockdown efficiency of approximately 50% by RT-qPCR (Figure 1B). The results showed that the average total dendritic length and number of intersections of primary cultured hippocampal neurons did not change significantly upon half reduction of Brpf1 expression (Figures 1C,D).

Figure 1. Mild knockdown of Brpf1 did not significantly change the total dendritic length and number of intersections. (A) Representative fluorescent images of cultured primary hippocampal neurons at DIV15 immunostained with anti-Map2 antibody, scale bar = 75 μm. (B) Quantitative mRNA analysis of Brpf1 knockdown efficiency (n = 4 batches for AAV-scramble and AAV-shBrpf1 groups, respectively, p < 0.001). (C) Quantification of total dendritic length of AAV-scramble or AAV-shBrpf1 group using “Simple Neurite Tracer” of ImageJ (n = 32 or 44 neurons from three independent batches for AAV-scramble or AAV-shBrpf1 group, respectively, p = 0.5472). (D) Sholl analysis of the number of intersections of the dendrites (n = 32 or 44 neurons from three independent batches for AAV-scramble or AAV-shBrpf1 group, respectively). ***p < 0.001.

Fifty Percent Knockdown of Brpf1 Led to Decreased mEPSC Frequency in vitro

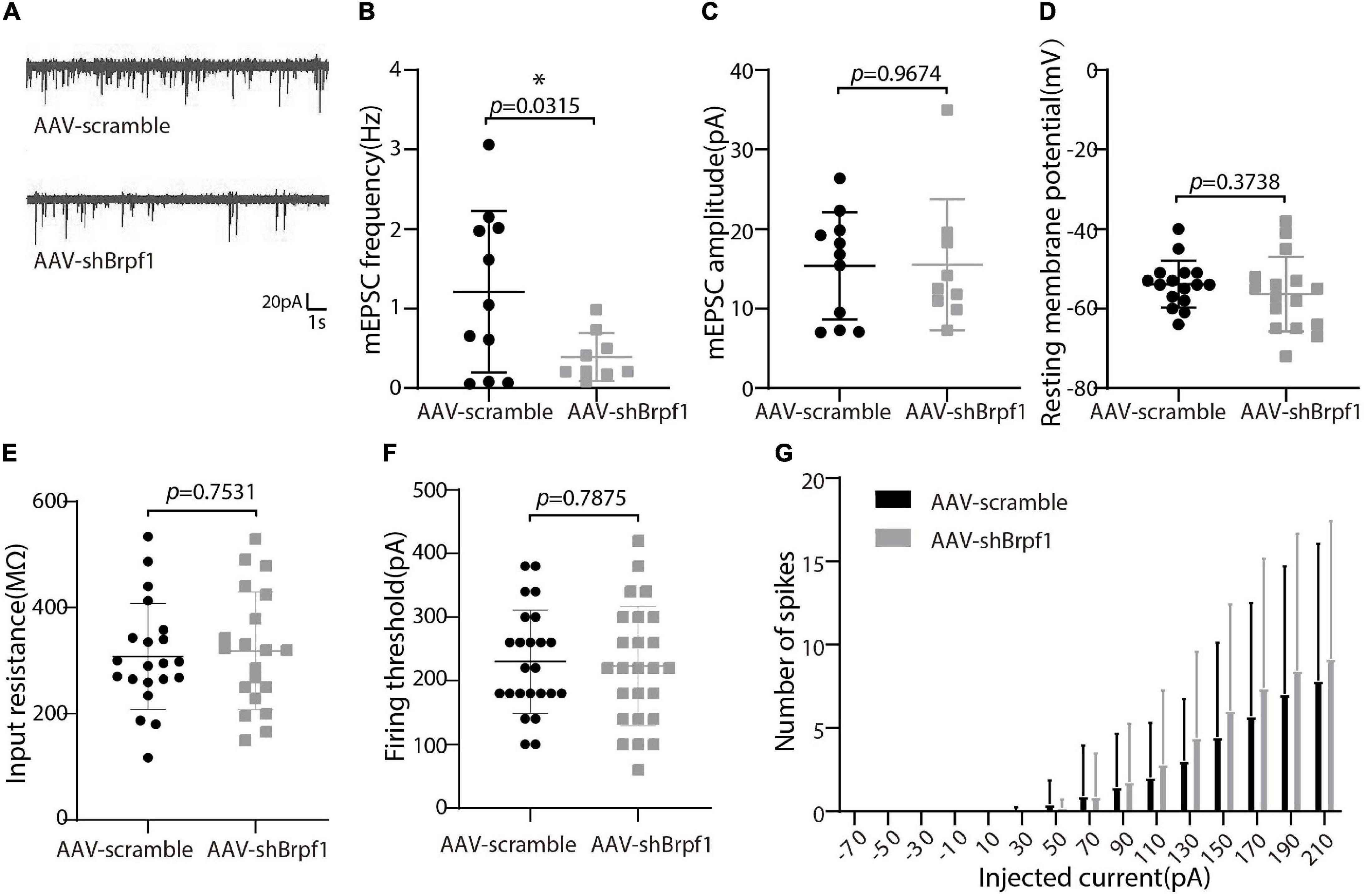

Alterations in learning and memory are closely associated with synaptic dysfunction (Volk et al., 2015). To study the synaptic transmission of hippocampal neurons upon Brpf1 knockdown, we performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings on cultured hippocampal neurons at DIV 15 after scramble or shBrpf1 infection at DIV3 (Figure 2). Because most hippocampal neurons are excitatory neurons, we recorded miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs). We recorded 6 min and selected the last 3 min for analysis because signals from the first 3 min were less stable. The results showed that the mEPSC frequency but not amplitude significantly decreased upon Brpf1 knockdown (Figures 2A–C), suggesting reduced excitatory synaptic transmission. For cell membrane characteristics, we measured resting membrane potential (RMP) and evoked action potentials (APs). The RMP, input resistance, firing threshold, and evoked APs did not show significant changes (Figures 2D–G), indicating few changes of cell excitability. Collectively, these results suggested that 50% knockdown of Brpf1 already led to reduced synaptic transmission before any obvious morphological changes.

Figure 2. Mild knockdown of Brpf1 led to decreased mEPSC frequency. (A) Representative traces of mEPSCs recorded in cultured primary hippocampal neurons of AAV-scramble or AAV-shBrpf1 group, scale bar, 20 pA and 1 s. (B) Statistical comparison of mEPSC frequency between AAV-scramble and AAV-shBrpf1 groups (AAV-scramble, n = 11 neurons; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 9 neurons; p = 0.0315). (C) Statistical comparison of mEPSC amplitude using the same dataset as (B) (p = 0.9674). (D) Comparison of RMP between the two groups (AAV-scramble, n = 16 neurons; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 16 neurons; p = 0.3738). (E) Comparison of input resistance (AAV-scramble, n = 21 neurons; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 20 neurons; p = 0.7531). (F) Comparison of firing threshold (AAV-scramble, n = 25 neurons; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 24 neurons; p = 0.7875). (G) The number of spikes displayed against depolarizing current steps of increasing amplitude with injected currents ranging from –70 to 210 pA at 20-pA intervals (AAV-scramble, n = 25 neurons; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 24 neurons). *p < 0.05.

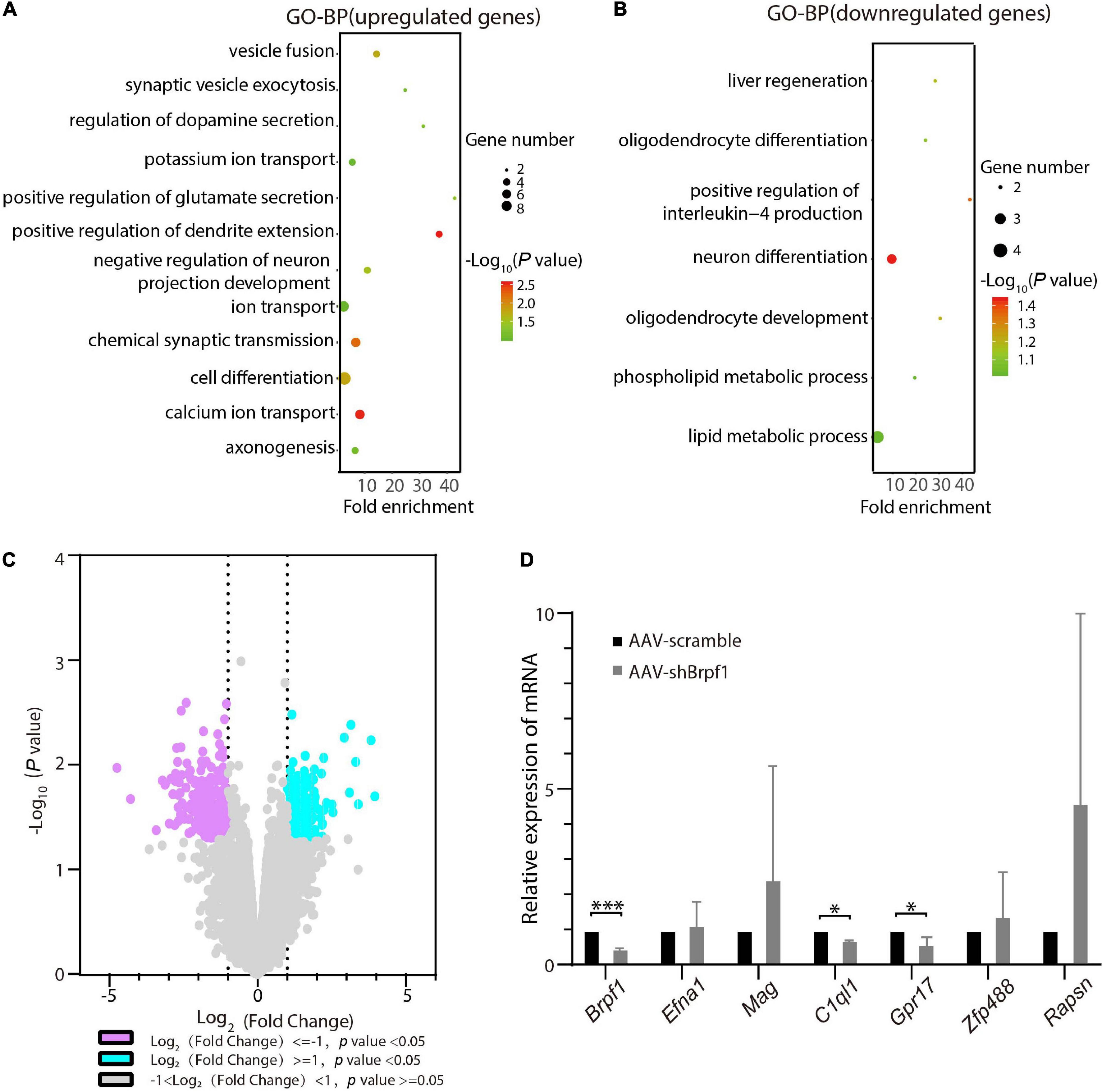

Brpf1 Mild Knockdown Led to Downregulation of C1ql1 and Gpr17 in vitro

To figure out the molecular mechanism of how Brpf1 regulates the electrophysiological activity of hippocampal neurons, three batches of RNA from scramble and shBrpf1 groups were extracted for mRNA-Seq analysis. DESeq2 software was used to screen differentially expressed genes (DEGs). 218 and 402 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, upon Brpf1 knockdown (Supplementary Table 2). GO-biological process (BP) analysis revealed that upregulated genes were mainly involved in ion transport, chemical synaptic transmission, and other biological processes, while downregulated genes were mainly involved in neuronal differentiation, oligodendrocyte differentiation, and development (Figures 3A,B and Supplementary Table 3). We then selected mainly neuron-related genes for verification by RT-qPCR (Figures 3C,D). Complement C1q-like 1 (C1ql1) and G protein-coupled receptor 17 (Gpr17) were downregulated in both mRNA-Seq analysis and RT-qPCR verification upon Brpf1 knockdown. C1ql1 is highly expressed in the brain (Berube et al., 1999). Interestingly, C1q tagging of synapses plays a critical role in synaptic elimination by microglia and is seen throughout the developing brain (Stevens et al., 2007; Li and Barres, 2018). Gpr17 plays a role in improving learning and memory in rats (Marschallinger et al., 2015). This suggested that the decreased frequency of mEPSCs caused by Brpf1 mild knockdown may be associated with dysregulated synaptic elimination.

Figure 3. Brpf1 knockdown led to downregulation of C1ql1 and Gpr17. (A,B) Bubble plots represented GO-BP of upregulated genes [log2(fold change) ≥ 1 and p < 0.05] and downregulated genes [log2(fold change) ≤ –1 and p < 0.05] derived from mRNA-Seq analysis of three pairs of cultured primary hippocampal neurons, respectively. Dot size reflected gene number; color indicated –log10P. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs from mRNA-Seq similar to (A,B). (D) Selected DEGs were validated by RT-qPCR (AAV-scramble group, n = 3 batches; AAV-shBrpf1 group, n = 3 batches). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

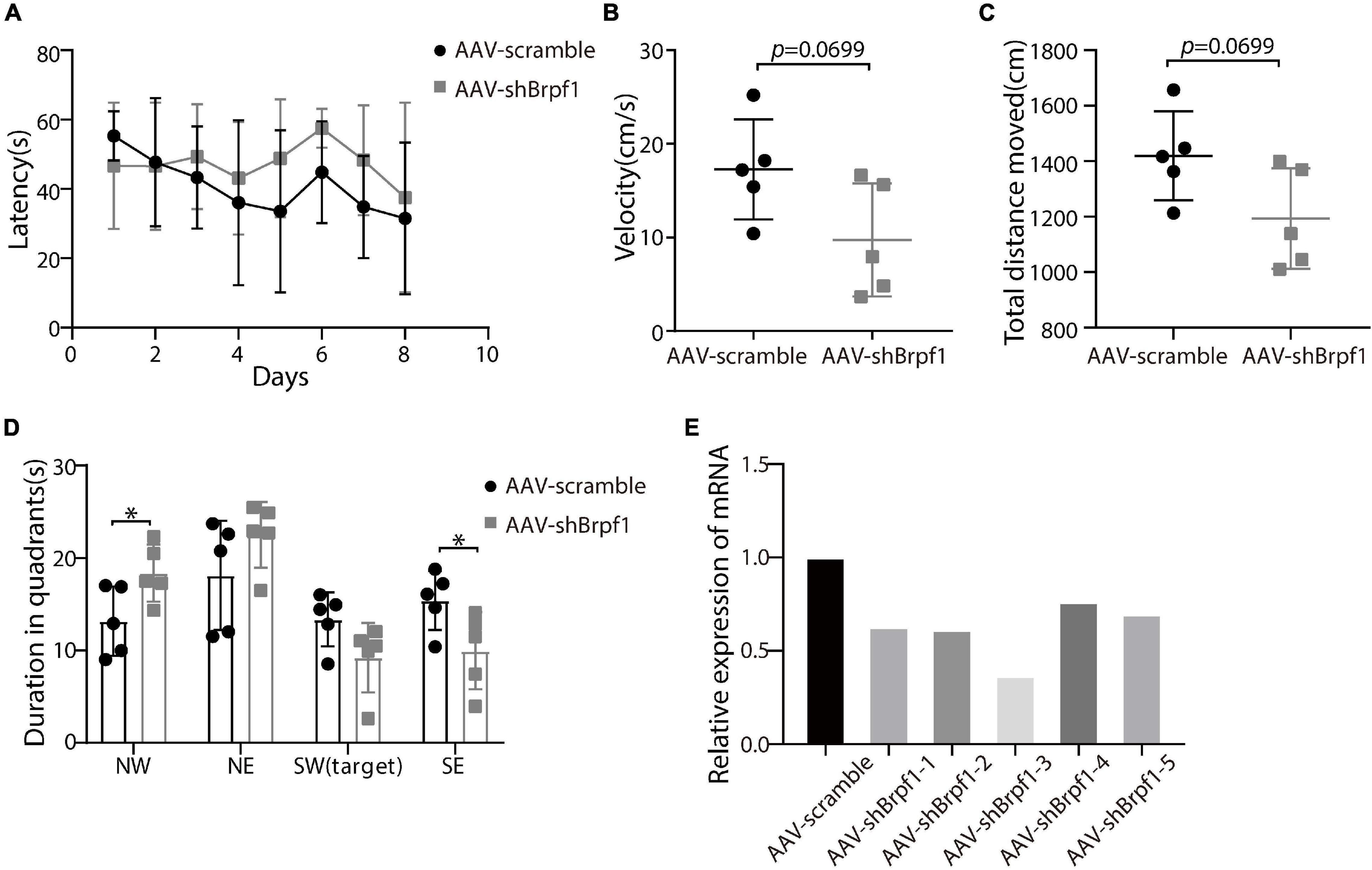

Brpf1 Mild Knockdown Showed a Tendency of Reduction on Spatial Learning and Memory Ability in vivo

To study whether Brpf1 knockdown in the hippocampus affects the learning and memory ability of mice, we injected AAV2-scramble-GFP or AAV2-shBrpf1-GFP into 4-week-old mouse hippocampi by stereotactic operation. Four weeks after surgery, we performed the Morris water maze test to assess the spatial learning and memory ability of those mice. Although the latency of mice to reach the platform was almost the same (Figure 4A), a mild decreasing trend of the swimming speed and the total distance moved in the probe trail were found upon Brpf1 knockdown (Figures 4B,C). Moreover, there was a significant difference of their stay time in the northwest (NW) and southeast (SE) quadrants, indicating a decreasing tendency of the space exploration ability, although no significant difference in the target quadrant (SW) was found (Figure 4D). This behavioral change was caused by a mild knockdown of Brpf1, with the knockdown efficiency varying from 40 to 70% in five mice tested (Figure 4E). These results indicated that Brpf1 mild knockdown in the hippocampus led to a tendency of reduction on the spatial learning and memory ability.

Figure 4. Mild knockdown of Brpf1 showed a decreasing trend on the learning and memory ability of mice. (A) Statistical comparison of the latency of the mice to reach the platform during the 8-day training period (AAV-scramble, n = 5 mice; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 5 mice). (B) Statistical comparison of the average swimming speed of mice on day 8 in the target quadrant (AAV-scramble, n = 5 mice; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 5 mice; p = 0.0699). (C) Statistical comparison of the total moving distance of mice in the target quadrant (AAV-scramble, n = 5 mice; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 5 mice; p = 0.0699). (D) Statistical comparison of the time spent in different quadrants on day 8 (AAV-scramble, n = 5 mice; AAV-shBrpf1, n = 5 mice; ∗p < 0.05). (E) Relative expression of Brpf1 mRNA in the hippocampus of each mouse compared to the scramble group.

Brpf1 Mild Knockdown in the Hippocampus Led to Dysregulated Gene Expression Related to Synaptic Function in vivo

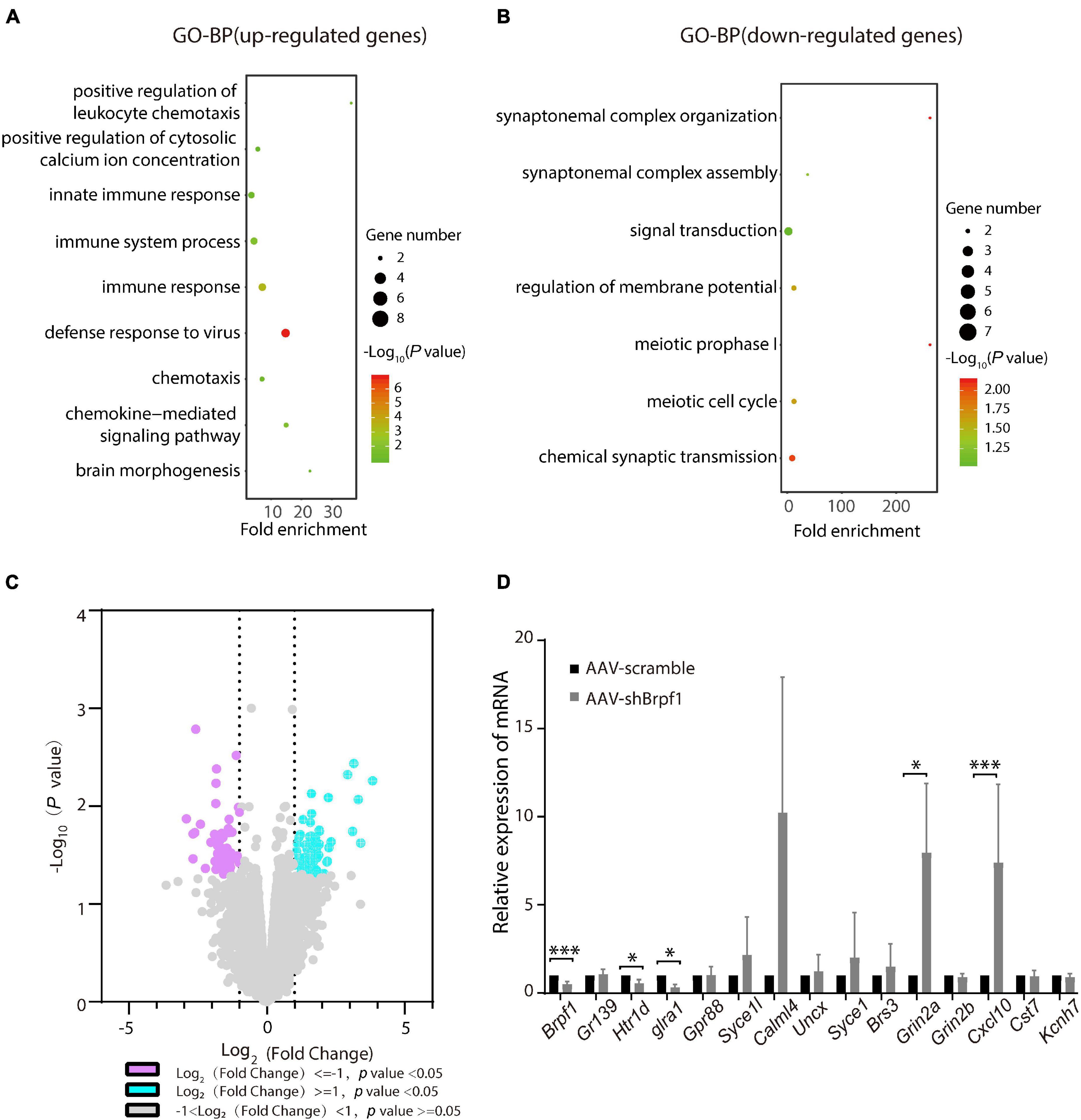

To study the molecular mechanism of Brpf1 knockdown leading to a decreasing trend in learning and memory ability, three pairs of RNA from scramble and shBrpf1 stereotactically injected CA1 tissues were extracted for mRNA-Seq analysis. 99 upregulated and 74 downregulated genes were subject to GO-BP analysis (Supplementary Table 4). We found that upregulated genes were mainly involved in immune response, brain morphogenesis, and other processes, while downregulated genes were mainly involved in signal transduction, regulation of membrane potential, and chemical synaptic transmission (Figures 5A,B and Supplementary Table 5). We then selected genes related to learning and memory from DEGs and verified them by RT-qPCR (Figures 5C,D). The results showed that glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA-type subunit 2A (Grin2a) and C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 (Cxcl10) were significantly upregulated, while 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1D (Htr1d) and glycine receptor alpha 1 (Glra1) were significantly downregulated. Grin2a-encoded protein is a subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, the activation of which results in a calcium influx into postsynaptic cells (Franchini et al., 2020). Cxcl10 could modulate neuronal activity and plasticity in the hippocampus (Kodangattil et al., 2012). Upregulation of Cxcl10 could occur in response to synaptic degeneration (Fuchtbauer et al., 2011). Htr1d regulates the release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), one of the main neurotransmitters in the brain, and thereby affects neural activity (Weinshank et al., 1992). Glra1 mediates postsynaptic inhibition in the spinal cord and other areas of the central nervous system (Nakahata et al., 2017). Collectively, Brpf1 mild knockdown in the hippocampus led to dysregulated gene expression related to synaptic function.

Figure 5. Hippocampus-specific knockdown of Brpf1 regulated the expression of genes related to synaptic function. (A,B) Bubble plots represented GO-BP of upregulated genes [log2(fold change) ≥ 1 and p < 0.05] and downregulated genes [log2(fold change) ≤ –1 and p < 0.05] derived from mRNA-Seq analysis of three pairs of stereotactic injected CA1 tissue, respectively. Dot size reflected gene number; color indicated –log10P. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs from mRNA-Seq similar to (A,B). (D) Selected DEGs were validated by RT-qPCR (AAV-scramble group, n = 3 mice; AAV-shBrpf1 group, n = 3 mice). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

Accumulating clinical studies have reported totally 40 cases of patients with BRPF1 monoallelic mutations, with symptoms such as intellectual disability, developmental delay, and epilepsy (Mattioli et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017, 2020; Baker et al., 2019; Pode-Shakked et al., 2019). In this study, we found that 50% knockdown of mouse Brpf1 reduced mEPSC frequency of primary cultured hippocampal neurons in vitro (Figure 2), before any significant effect showed on the neuronal dendritic morphology (Figure 1). In addition, Brpf1 mild knockdown showed a decreasing trend on the learning and memory ability of mice (Figure 4). The underlying molecular mechanism may involve dysregulated genes related to learning, memory, and synaptic transmission (Figures 3, 5).

The imbalance of excitatory/inhibitory neural circuits is closely related to diseases with learning and memory deficits. In this study, we found that Brpf1 mild knockdown reduced the frequency but not the amplitude of mEPSCs in cultured hippocampal neurons. Similarly, another group showed that forebrain-specific heterozygous knockout of Brpf1 caused a significant decrease in the frequency and less significant decrease in the amplitude of hippocampal mEPSCs using acute brain slices at P30 (Su et al., 2019). The discrepancy of the effect of Brpf1 on the amplitude of mEPSCs may be due to different models (primary cultured hippocampal neurons vs. acute hippocampal slices) and ages (E17.5–E18.5 vs. P30). It could be possible that the effect of Brpf1 haploinsufficiency (50% knockdown) on the amplitude of mEPSCs in hippocampal neurons gradually becomes obvious as mice grow, but the effect on the frequency of mEPSCs is already significant as early as E17.5–E18.5. In addition, Brd1+/− (also known as Brpf2) pyramidal neurons showed decreased frequency of spontaneous IPSCs and mIPSCs (Qvist et al., 2017a). Interestingly, Brd1 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Severinsen et al., 2006; Fryland et al., 2016; Qvist et al., 2017a). Besides BRPF1, related histone acetyltransferases MOZ and MORF were also found mutated in patients with abnormal neurodevelopment and intellectual disability (Gannon et al., 2015; Tham et al., 2015; Kennedy et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020); however, no studies of their effect on the electrophysiology of neurons have been reported.

The mild knockdown of Brpf1 led to significant changes in electrophysiological properties before any major influence showed in dendritic morphology. Thus, we performed mRNA-Seq analysis to mainly explain the change in electrophysiology. The analysis revealed that C1ql1 and Gpr17 were significantly downregulated. C1ql1 plays an important role in the formation and maintenance of synapses in the central nervous system (Yuzaki, 2017). Relatedly, C1q tagging of synapses is pivotal in synaptic pruning and prevalent in the developing brain (Stevens et al., 2007; Li and Barres, 2018). Montelukast (targets leukotriene receptors GPR17 and CysLTR1) could improve learning and memory in old rats (Marschallinger et al., 2015). In addition, Gpr17 is a functional receptor that involves the generation of outward K+ currents in the signal transduction pathway and can reduce neuronal overexcitement in the brain (Pugliese et al., 2009). The association of the decreased frequency of mEPSCs in primary hippocampal neurons caused by Brpf1 mild knockdown and possible dysregulated synaptic elimination by C1q is an inspiring finding that merits further investigations.

A change in mEPSC frequency often indicates presynaptic release in probability alternations, whereas a change in mEPSC amplitude often indicates postsynaptic receptor function or/and number alternations. As revealed by the enrichment analysis of the DEGs from shBrpf1 vs. scramble infected primary hippocampal neurons (Supplementary Table 3), upregulated genes Cck and Syt4 were involved in “positive regulation of glutamate secretion”. Cck regulates gastric acid secretion and food intake (Miyasaka et al., 2005), while Syt4 serves as Ca2+ sensors in the process of vesicular trafficking and is thought to function as an inhibitor of neurotransmitter release (Littleton et al., 1999). Both do not act directly in glutamate secretion. Also, five upregulated genes, namely, Pnoc, Fgf14, Cacnb2, Sv2b, and Htr2c, were involved in “chemical synaptic transmission”. Pnoc is crucially in the neurobiological regulation of stress-coping behavior and fear (Koster et al., 1999); Fgf14 is involved in the regulation of Purkinje cell firing by altering the expression of Nav1.6 channels (Shakkottai et al., 2009); Cacnb2 variation is associated with functional connectivity in the hippocampus in bipolar disorder (Liu et al., 2019); and Sv2b deficiency did not affect glutamatergic or GABAergic transmission (Venkatesan et al., 2012). They also do not have significant roles in glutamate secretion. How Brpf1 deficiency affects presynaptic alternations will need more investigations.

Interestingly, decreased frequency of mEPSCs caused by Brpf1 mild knockdown was associated with a tendency of reduction on learning and memory ability in young adult mice. Patients with BRPF1 monoallelic mutations would only have half expression of BRPF1 throughout development and into the postnatal life. Our finding was derived from acute knockdown conditions, and the effect was mild and limited. This is consistent with previous studies showing that both Brpf2 heterozygotes and Brpf1 forebrain-specific heterozygous knockout mice exhibited learning, memory, and cognitive dysfunction (Qvist et al., 2017b; Su et al., 2019). Our findings further supported that only half reduction of the Brpf1 dose could affect excitatory synaptic transmission and further impair learning and memory ability.

At the molecular level, the expression of Cxcl10 and Grin2a increased significantly upon Brpf1 mild knockdown. Grin2a is a subunit of the NMDA receptor, which is permeable to Na+, K+, and Ca2+, thereby regulating signal transduction pathways (Sanders et al., 2018). NMDA receptors are involved in long-term potentiation and activation of those receptors results in a calcium influx into postsynaptic cells (Franchini et al., 2020). Patients with GRIN2A mutations began to develop neurological abnormalities 1 year after birth and were often accompanied with epilepsy (Pierson et al., 2014). Cxcl10 could induce apoptosis and death of hippocampal neurons (Sui et al., 2006; van Weering et al., 2011). Acute exposure to Cxcl10 altered neuronal signaling properties and reduced long-term potentiation in mouse adult hippocampal slices. It also altered spontaneous synaptic network activity, spike firing, and intracellular Ca2+ levels in cultured hippocampal neurons (Nelson and Gruol, 2004; Vlkolinsky et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2009). In addition, Glra1 and Htr1d were significantly downregulated upon Brpf1 mild knockdown (Figure 5D). Glra1 homozygous mutant mice showed complex motor dysfunction (Kling et al., 1997), and there was no glycine-induced current and IPSC in all bipolar cells of Glra1-deficient mice (Ivanova et al., 2006). Htr1d regulates the release of 5-HT, one of the main neurotransmitters in the brain, and thereby affects neural activity (Weinshank et al., 1992). Its mutations often led to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Li et al., 2006). Collectively, Brpf1 mild knockdown in the hippocampus in vivo led to dysregulated gene expression related to synaptic function. A more direct link between these genes and Brpf1 merits further investigations.

In summary, our results indicated that Brpf1 plays an important role in mouse hippocampal neurons, including attenuation of electrophysiological activity, impairment of learning and memory, and changes in gene regulation, which might partially explain the mechanism of BRPF1 mutations causing intellectual disability in children.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: Gene expression data are available at GEO with the accession number: GSE174600 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE174600).

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by local committees of the guidelines of the laboratory animals at Fudan University (Shanghai, China).

Author Contributions

WX initiated and performed most of the experiments. JC finished the project. XY performed the stereotactic injections and helped analyze the data. WX, JC, and XY designed the experiments and analyzed the data. GW, QJ, and HZ helped collect and analyze the data. WX, JC, and LY co-wrote the manuscript. GZ and LY conceived the idea and supervised the study. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771228) to LY, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571238) to GZ, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971110) to XY.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank members from LY’s lab for their support and help during the experiments.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.711792/full#supplementary-material

References

Baker, S. W., Murrell, J. R., Nesbitt, A. I., Pechter, K. B., Balciuniene, J., Zhao, X., et al. (2019). Automated clinical exome reanalysis reveals novel diagnoses. J. Mol. Diag. 21, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.07.008

Beaudoin, G. M. J., Lee, S. H., Singh, D., Yuan, Y., Ng, Y. G., Reichardt, L. F., et al. (2012). Culturing pyramidal neurons from the early postnatal mouse hippocampus and cortex. Nat. Protocols 7, 1741–1754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.099

Berube, N. G., Swanson, X. H., Bertram, M. J., Kittle, J. D., Didenko, V., Baskin, D. S., et al. (1999). Cloning and characterization of CRF, a novel C1q-related factor, expressed in areas of the brain involved in motor function. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 63, 233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00278-2

Cho, J., Nelson, T. E., Bajova, H., and Gruol, D. L. (2009). Chronic CXCL10 alters neuronal properties in rat hippocampal culture. J. Neuroimmunol. 207, 92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.007

Demeulenaere, S., Beysen, D., De Veuster, I., Reyniers, E., Kooy, F., and Meuwissen, M. (2019). Novel BRPF1 mutation in a boy with intellectual disability, coloboma, facial nerve palsy and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 103691–103691. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.103691

Ferguson, G. D., Wang, H., Herschman, H. R., and Storm, D. R. (2004). Altered hippocampal short-term plasticity and associative memory in synaptotagmin IV (-/-) mice. Hippocampus 14, 964–974. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20013

Franchini, L., Carrano, N., Di Luca, M., and Gardoni, F. (2020). Synaptic GluN2A-Containing NMDA receptors: from physiology to pathological synaptic plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1538. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041538

Fryland, T., Christensen, J. H., Pallesen, J., Mattheisen, M., Palmfeldt, J., Bak, M., et al. (2016). Identification of the BRD1 interaction network and its impact on mental disorder risk. Genome Med. 8:53. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0308-x

Fuchtbauer, L., Groth-Rasmussen, M., Holm, T. H., Lobner, M., Toft-Hansen, H., Khorooshi, R., et al. (2011). Angiotensin II Type 1 receptor (AT1) signaling in astrocytes regulates synaptic degeneration-induced leukocyte entry to the central nervous system. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.015

Gannon, T., Perveen, R., Schlecht, H., Ramsden, S., Anderson, B., Kerr, B., et al. (2015). Further delineation of the KAT6B molecular and phenotypic spectrum. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.248

Huang Da, W., Sherman, B. T., and Lempicki, R. A. (2009a). Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923

Huang Da, W., Sherman, B. T., and Lempicki, R. A. (2009b). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211

Ilyas, M., Mir, A., Efthymiou, S., and Houlden, H. (2020). The genetics of intellectual disability: advancing technology and gene editing. F1000Res 9:F1000 Faculty Rev-22. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16315.1

Ivanova, E., Muller, U., and Wassle, H. (2006). Characterization of the glycinergic input to bipolar cells of the mouse retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 350–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04557.x

Kennedy, J., Goudie, D., Blair, E., Chandler, K., Joss, S., Mckay, V., et al. (2019). KAT6A Syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlation in 76 patients with pathogenic KAT6A variants. Genet. Med. 21, 850–860. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0259-2

Klein, B. J., Muthurajan, U. M., Lalonde, M. E., Gibson, M. D., Andrews, F. H., Hepler, M., et al. (2016). Bivalent interaction of the PZP domain of BRPF1 with the nucleosome impacts chromatin dynamics and acetylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 472–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1321

Kling, C., Koch, M., Saul, B., and Becker, C. M. (1997). The frameshift mutation oscillator (Glra1(spd-ot)) produces a complete loss of glycine receptor alpha1-polypeptide in mouse central nervous system. Neuroscience 78, 411–417. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00567-2

Kodangattil, J. N., Möddel, G., Müller, M., Weber, W., and Gorji, A. (2012). The inflammatory chemokine CXCL10 modulates synaptic plasticity and neuronal activity in the hippocampus. Eur. J. Inflamm. 10, 311–328. doi: 10.1177/1721727x1201000307

Koster, A., Montkowski, A., Schulz, S., Stube, E. M., Knaudt, K., Jenck, F., et al. (1999). Targeted disruption of the orphanin FQ/nociceptin gene increases stress susceptibility and impairs stress adaptation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 96, 10444–10449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10444

Li, J., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Zhou, R., Zhang, H., Yang, L., et al. (2006). The serotonin 5-HT1D receptor gene and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Chinese Han subjects. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 141B, 874–876. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30364

Li, Q., and Barres, B. A. (2018). Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 225–242. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.125

Littleton, J. T., Serano, T. L., Rubin, G. M., Ganetzky, B., and Chapman, E. R. (1999). Synaptic function modulated by changes in the ratio of synaptotagmin I and IV. Nature 400, 757–760. doi: 10.1038/23462

Liu, F., Gong, X., Yao, X., Cui, L., Yin, Z., Li, C., et al. (2019). Variation in the CACNB2 gene is associated with functional connectivity of the Hippocampus in bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry 19:62. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2040-8

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lubula, M. Y., Eckenroth, B. E., Carlson, S., Poplawski, A., Chruszcz, M., and Glass, K. C. (2014a). Structural insights into recognition of acetylated histone ligands by the BRPF1 bromodomain. FEBS Lett. 588, 3844–3854. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.028

Lubula, M. Y., Poplawaski, A., and Glass, K. C. (2014b). Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the BRPF1 bromodomain in complex with its H2AK5ac and H4K12ac histone-peptide ligands. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 1389–1393. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X14018433

Marschallinger, J., Schaffner, I., Klein, B., Gelfert, R., Rivera, F. J., Illes, S., et al. (2015). Structural and functional rejuvenation of the aged brain by an approved anti-asthmatic drug. Nat. Commun. 6:8466. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9466

Mattioli, F., Schaefer, E., Magee, A., Mark, P., Mancini, G. M., Dieterich, K., et al. (2017). Mutations in histone acetylase modifier BRPF1 cause an autosomal-dominant form of intellectual disability with associated ptosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.010

Miyasaka, K., Kanai, S., Ohta, M., Hosoya, H., Takano, S., Sekime, A., et al. (2005). Overeating after restraint stress in cholecystokinin-a receptor-deficient mice. Jpn. J. Physiol. 55, 285–291. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.R2117

Nakahata, Y., Eto, K., Murakoshi, H., Watanabe, M., Kuriu, T., Hirata, H., et al. (2017). Activation-Dependent rapid postsynaptic clustering of glycine receptors in mature spinal cord neurons. eNeuro 4:ENEURO.0194-16.2017. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0194-16.2017

Nelson, T. E., and Gruol, D. L. (2004). The chemokine CXCL10 modulates excitatory activity and intracellular calcium signaling in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neuroimmunol. 156, 74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.07.009

O’Neill, K. M., Akum, B. F., Dhawan, S. T., Kwon, M., Langhammer, C. G., and Firestein, B. L. (2015). Assessing effects on dendritic arborization using novel Sholl analyses. Front. Cell Neurosci. 9:285. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00285

Pierson, T. M., Yuan, H., Marsh, E. D., Fuentes-Fajardo, K., Adams, D. R., Markello, T., et al. (2014). GRIN2A mutation and early-onset epileptic encephalopathy: personalized therapy with memantine. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 1, 190–198. doi: 10.1002/acn3.39

Pode-Shakked, N., Barel, O., Pode-Shakked, B., Eliyahu, A., Singer, A., Nayshool, O., et al. (2019). BRPF1-associated intellectual disability, ptosis, and facial dysmorphism in a multiplex family. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7:e665. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.665

Poplawski, A., Hu, K., Lee, W., Natesan, S., Peng, D., Carlson, S., et al. (2014). Molecular insights into the recognition of N-terminal histone modifications by the BRPF1 bromodomain. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 1661–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.007

Pugliese, A. M., Trincavelli, M. L., Lecca, D., Coppi, E., Fumagalli, M., Ferrario, S., et al. (2009). Functional characterization of two isoforms of the P2Y-like receptor GPR17: [35S]GTPgammaS binding and electrophysiological studies in 1321N1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C1028–C1040. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00658.2008

Qvist, P., Christensen, J. H., Vardya, I., Rajkumar, A. P., Mørk, A., Paternoster, V., et al. (2017a). The schizophrenia-associated BRD1 gene regulates behavior, neurotransmission, and expression of schizophrenia risk enriched gene sets in mice. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.037

Qvist, P., Rajkumar, A. P., Redrobe, J. P., Nyegaard, M., Christensen, J. H., Mors, O., et al. (2017b). Mice heterozygous for an inactivated allele of the schizophrenia associated Brd1 gene display selective cognitive deficits with translational relevance to schizophrenia. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 141, 44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.03.009

Sanders, E. M., Nyarko-Odoom, A. O., Zhao, K., Nguyen, M., Liao, H. H., Keith, M., et al. (2018). Separate functional properties of NMDARs regulate distinct aspects of spatial cognition. Learn. Mem. 25, 264–272. doi: 10.1101/lm.047290.118

Severinsen, J. E., Bjarkam, C. R., Kiaer-Larsen, S., Olsen, I. M., Nielsen, M. M., Blechingberg, J., et al. (2006). Evidence implicating BRD1 with brain development and susceptibility to both schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 11, 1126–1138. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001885

Shakkottai, V. G., Xiao, M., Xu, L., Wong, M., Nerbonne, J. M., Ornitz, D. M., et al. (2009). FGF14 regulates the intrinsic excitability of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 33, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.019

Stevens, B., Allen, N. J., Vazquez, L. E., Howell, G. R., Christopherson, K. S., Nouri, N., et al. (2007). The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell 131, 1164–1178.

Su, Y., Liu, J., Yu, B., Ba, R., and Zhao, C. (2019). Brpf1 haploinsufficiency impairs dendritic arborization and spine formation, leading to cognitive deficits. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13:249. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00249

Sui, Y., Stehno-Bittel, L., Li, S., Loganathan, R., Dhillon, N. K., Pinson, D., et al. (2006). CXCL10-induced cell death in neurons: role of calcium dysregulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 957–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04631.x

Tham, E., Lindstrand, A., Santani, A., Malmgren, H., Nesbitt, A., Dubbs, H. A., et al. (2015). Dominant mutations in KAT6A cause intellectual disability with recognizable syndromic features. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96, 507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.016

van Weering, H. R., Boddeke, H. W., Vinet, J., Brouwer, N., De Haas, A. H., Van Rooijen, N., et al. (2011). CXCL10/CXCR3 signaling in glia cells differentially affects NMDA-induced cell death in CA and DG neurons of the mouse hippocampus. Hippocampus 21, 220–232. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20742

Venkatesan, K., Alix, P., Marquet, A., Doupagne, M., Niespodziany, I., Rogister, B., et al. (2012). Altered balance between excitatory and inhibitory inputs onto CA1 pyramidal neurons from SV2A-deficient but not SV2B-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 90, 2317–2327. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23111

Vezzoli, A., Bonadies, N., Allen, M. D., Freund, S. M., Santiveri, C. M., Kvinlaug, B. T., et al. (2010). Molecular basis of histone H3K36me3 recognition by the PWWP domain of Brpf1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 617–619. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1797

Vlkolinsky, R., Siggins, G. R., Campbell, I. L., and Krucker, T. (2004). Acute exposure to CXC chemokine ligand 10, but not its chronic astroglial production, alters synaptic plasticity in mouse hippocampal slices. J. Neuroimmunol. 150, 37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.01.011

Volk, L., Chiu, S. L., Sharma, K., and Huganir, R. L. (2015). Glutamate synapses in human cognitive disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 127–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-033821

Weinshank, R. L., Zgombick, J. M., Macchi, M. J., Branchek, T. A., and Hartig, P. R. (1992). Human serotonin 1D receptor is encoded by a subfamily of two distinct genes: 5-HT1D alpha and 5-HT1D beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 89, 3630–3634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3630

Yan, K., Rousseau, J., Littlejohn, R. O., Kiss, C., Lehman, A., Rosenfeld, J. A., et al. (2017). Mutations in the chromatin regulator gene BRPF1 cause syndromic intellectual disability and deficient histone acetylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.011

Yan, K., Rousseau, J., Machol, K., Cross, L. A., Agre, K. E., Gibson, C. F., et al. (2020). Deficient histone H3 propionylation by BRPF1-KAT6 complexes in neurodevelopmental disorders and cancer. Sci. Adv. 6:eaax0021. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0021

You, L., Chen, L., Penney, J., Miao, D., and Yang, X. J. (2014). Expression atlas of the multivalent epigenetic regulator Brpf1 and its requirement for survival of mouse embryos. Epigenetics 9, 860–872. doi: 10.4161/epi.28530

You, L., Yan, K., Zou, J., Zhao, H., Bertos, N. R., Park, M., et al. (2015a). The chromatin regulator Brpf1 regulates embryo development and cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11349–11364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.643189

You, L., Yan, K., Zou, J., Zhao, H., Bertos, N. R., Park, M., et al. (2015b). The lysine acetyltransferase activator Brpf1 governs dentate gyrus development through neural stem cells and progenitors. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005034

You, L., Zou, J., Zhao, H., Bertos, N. R., Park, M., Wang, E., et al. (2015c). Deficiency of the chromatin regulator Brpf1 causes abnormal brain development. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 7114–7129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635250

Yuzaki, M. (2017). The C1q complement family of synaptic organizers: not just complementary. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 45, 9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.02.002

Zhang, L. X., Lemire, G., Gonzaga-Jauregui, C., Molidperee, S., Galaz-Montoya, C., Liu, D. S., et al. (2020). Further delineation of the clinical spectrum of KAT6B disorders and allelic series of pathogenic variants. Genet. Med. 22, 1338–1347. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0811-8

Keywords: intellectual disability, BRPF1, primary cultured hippocampal neurons, dendritic morphology, electrophysiology, stereotactic hippocampal injection, Morris water maze, mRNA-seq

Citation: Xian W, Cao J, Yuan X, Wang G, Jin Q, Zhang H, Zhou G and You L (2021) Deficiency of Intellectual Disability-Related Gene Brpf1 Attenuated Hippocampal Excitatory Synaptic Transmission and Impaired Spatial Learning and Memory Ability. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:711792. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.711792

Received: 19 May 2021; Accepted: 22 July 2021;

Published: 17 August 2021.

Edited by:

Adelaide Fernandes, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Li-Ming Chen, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaJames Alan Marrs, Indiana University, Purdue University Indianapolis, United States

Copyright © 2021 Xian, Cao, Yuan, Wang, Jin, Zhang, Zhou and You. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guomin Zhou, Z216aG91QHNobXUuZWR1LmNu; Linya You, bHl5b3VAZnVkYW4uZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Weiwei Xian

Weiwei Xian Jingli Cao

Jingli Cao Xiangshan Yuan

Xiangshan Yuan Guoxiang Wang

Guoxiang Wang Qiuyan Jin

Qiuyan Jin Hang Zhang

Hang Zhang Guomin Zhou

Guomin Zhou Linya You

Linya You