- 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Department of Pathology, USC/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 3Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

The two homologous estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ exert distinct effects on their cognate tissues. Previous work from our laboratory identified an ERβ-specific phosphotyrosine residue that regulates ERβ transcriptional activity and antitumor function in breast cancer cells. To determine the physiological role of the ERβ phosphotyrosine residue in normal tissue development and function, we investigated a mutant mouse model (Y55F) whereby this particular tyrosine residue in endogenous mouse ERβ is mutated to phenylalanine. While grossly indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates, mutant female mice displayed reduced fertility, decreased ovarian follicular cell proliferation, and lower progesterone levels. Moreover, mutant ERβ from female mice during superovulation is defective in activating promoters of its target genes in ovarian tissues. Thus, our findings provide compelling genetic and molecular evidence for a role of isotype-specific ERβ phosphorylation in mouse ovarian development and function.

Introduction

The steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone play vital roles in female reproduction, with the ovary serving as the primary tissue of their synthesis and one of the target sites (Emmen et al., 2005). The physiological actions of estrogen are mediated by two estrogen receptors: ERα and ERβ. Despite considerable sequence homology between these two ER isotypes, there is emerging evidence for their distinct and even opposite effects on their cognate cell and tissue types. In the ovary, ERα is the predominant ER isotype in theca and interstitial cells (Schomberg et al., 1999), ERα null females exhibit large, hemorrhagic and cystic follicles and infertility (Couse and Korach, 1999; Couse et al., 2003; Emmen and Korach, 2003). On the other hand, ERβ is predominantly localized in ovarian granulosa cells, which are the major source for ovarian steroid production and a major site of expression of luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor (Sar and Welsch, 1999; Pelletier et al., 2000). ERβ-mediated estrogen synthesis is important for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-induced granulosa cell differentiation. Inactivation of ERβ in female mice leads to follicular maturation defect and subfertility (Krege et al., 1998; Dupont et al., 2000; Couse et al., 2005; Antal et al., 2008; Maneix et al., 2015).

The selective biological effects of ERα and ERβ partly result from their intrinsic differences in protein structure and transcriptional activity through recruitment of different transcription coactivators (O’Lone et al., 2004). Although the two ER subtypes share a high sequence homology in the central DNA binding domain and in carboxyl-terminal ligand-binding domain in the activation function domain 2, the more divergent sequence (∼15% sequence homology) in activation function domain 1 domain at the N-termini of the ER isotypes has been linked to subtype-specific activity (Madak-Erdogan et al., 2013). Both ERα and ERβ can directly bind to estrogen response elements (EREs) on DNA. In addition, they can exert transcriptional regulation by tethering to other transcription factors such as AP-1 and Sp1 on DNA (Saville et al., 2000; Cheung et al., 2005; Stender et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010). It is noteworthy that while 5% of ERβ-binding genomic regions contain ERE only, ∼60% of them include both ERE and AP-1 sites (Vivar et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010), suggesting that both ERE-binding and AP1-tethering mechanisms are involved in ERβ-dependent transcriptional activation. This may explain why earlier efforts to delete the DNA-binding domain of ERβ did not result in complete abolishment of ERβ function. Using a new ERβ knockout (KO) mouse line with deletion of all 10 exons of ERβ gene, a recent study found that ERβ regulates growth and differentiation of ventral prostate and mammary gland (Warner et al., 2020).

Despite considerable efforts to understand the role of ERβ posttranslational modifications (PTMs), the complexity of these modifications and their functions at the molecular, cellular, and organismal levels, are poorly understood (Tharun et al., 2015). So far, several phosphorylation residues, including Y36, S60, S75, S87, and S105, have been identified in human ERβ (Tremblay et al., 1999; Cheng et al., 2000; Tremblay and Giguere, 2001; St-Laurent et al., 2005; Picard et al., 2008; Lam et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2014). In particular, our published work identified a subtype-specific phosphotyrosine residue in human ERβ Y36 that regulates its tumor-intrinsic (Yuan et al., 2014, 2016) and -extrinsic (Yuan et al., 2021) antitumor activity, which underscores an ER subtype-specific regulatory mechanism via tyrosine phosphorylation.

In this study, we used a mutant mouse strain carrying the equivalent of the human Y36 mutation in ERβ (Esr2Y55F/Y55F) to investigate the role of this phosphorylation residue in ERβ function in mouse ovaries. Mutant ovaries were smaller and showed diffusely luteinized stroma, compared to their WT counterparts. In addition, the reduced fertility phenotype of female KI mice was accompanied with lower circulating progesterone levels. Lastly, we provide molecular evidence for a role of this ERβ phosphotyrosine switch in regulation of steroidogenic transcription.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Genomic mutation of Y55F was introduced into the Esr2 allele of mouse embryonic stem cells as described. WT and homozygous (Esr2Y55F/Y55F) mutant knock-in (KI) female littermates in the pure C57BL/6 background were generated by intercrossing of heterozygous Esr2+/Y55F mice. Mice were housed and maintained according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Unless otherwise stated, mice were super-ovulated by intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG, HOR-272, ProSpec), followed in 48 h with 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, CG5, Millipore Sigma) for in vivo studies (Hong et al., 2010). An IACUC approved animal protocol was followed for all animal experiments.

Western Blot Analysis

Ten isolated mouse ovaries at 8-week old were homogenized in Tissue Cell Lysis Buffer (GoldBio) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration of cell lysates was determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kits (#23225, Pierce). Primary antibodies against ERα (MC-20, Santa Cruz), ERβ (CWK-F12, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank and PPZ0506, Thermo Fisher), c-Abl (24-11, Santa Cruz), EYA2 (11314-1-AP, Proteintech), and β-actin (A5316, Sigma-Aldrich) and appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for protein detection. Immunoblotting signals were visualized with ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher).

Subcellular Fractionation Assay

293T cells in 6 cm plates were transfected with 2 μg expression plasmids of either FLAG ERβ (WT) or ERβ (Y55F). Cells were harvested 24 h post transfection. NE-PERTM Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to obtain nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions following manufacturer’s instructions. Subcellular fractionations were analyzed by Western blotting with α-Flag (F1804, Millipore Sigma) antibody to detect Flag-ERβ, and with α- H3 (Histone 3; # 9715, Cell Signaling), α-GAPDH (# 2118, Cell Signaling) antibodies as markers of the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation

For evaluation of commercially available ERβ antibodies, immunoprecipitation (IP) was set up with 293T/Flag-mERβ cells using 4 μg each of anti-ERβ antibody, mouse and rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories), anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads (Millipore Sigma). The following ERβ antibodies were used in this assay: MC10, 51-7700 and PAI-311 (Thermo Fisher), CWK-F12 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), clone 9.88 and 68-4 (Millipore Sigma), H-150 (Santa Cruz), and EPR3777 (Novus).

Immunohistochemistry

The anti-pY36 antibody, which was raised against the ERβ pY36-containing peptide SIYIPSS(pY)VDSHHE in rabbit (Yuan et al., 2014), and anti-Ki67 antibody (#12202, CST) were used. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described (Yuan et al., 2014). Briefly, 5 μm paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated, and processed for antigen retrieval with 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Thermo Fisher). Tissue sections were subsequently incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase, and non-specific binding was blocked by incubation with normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Sections were then immunostained with anti-ERβ pY36 (1:50) and Ki67 (1:500) antibodies in PBS overnight at 4∘C. After washing, sections were incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200 dilution, Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) was subsequently used for visualization according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The number of Ki67-positive granulosa cells from each ovary was recorded, and more than 1,500 cells from 7 individual animals were surveyed.

Serum Hormone Analysis

For collection of mouse serum, mice were injected i.p. with 5 IU PMSG, followed by 5 IU hCG injection 48 h later. Mouse blood samples were collected 16 h after hCG injection. Serum hormone measurement was performed by the University of Texas Health San Antonio Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory. Approximately 0.5 ml of blood was collected from each mouse, kept at 4∘C for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 6,000 g for 20 min. Serum samples were stored at −80∘C until processed for estradiol and progesterone measurements. For LC–MS/MS analyses, serum (100 μl made up to 200 μl with PBS), along with calibration standards (200 μl), and quality control samples (200 μl) were transferred into clean glass tubes and extracted with 1 mL of hexane:ethyl acetate (3:2 ratio) containing deuterated steroids as internal standards. Extracted samples were then left to allow phase separation at 4∘C for 1 h before placing them in a -80∘C freezer for 30 min to freeze the lower aqueous layer. The upper organic layer containing extracted target steroids was decanted into a clean glass tube and evaporated overnight at 37∘C. The dried samples were reconstituted in 1.2 mL of 20% methanol in PBS. After thorough mixing samples were transferred into 1.5 mL auto sampler vials and 1 mL was injected onto a C8 column for analysis. Steroid levels were calculated as amount per volume assayed for serum.

Fertility Test

Fertility tests of female WT (n = 10) and KI (n = 10) mice were performed using continuous mating with male WT mice (Krege et al., 1998). Mating started when the mice were 8-week old and lasted for 6 months. The number of litters were counted and pups were recorded on postnatal day 1 (P1).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Female mice were injected i.p. with 5 IU PMSG, followed by 5 IU hCG injection 48 h later. Ovarian samples were collected 16 h after hCG injection. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the ImProm-IITM Reverse Transcription System (Promega). qPCR reactions were conducted in the ABI PRISM 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System using Luminaris Color HiGreen qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) and 0.25 μM of each primer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers for each gene are as follows:

Cyp11a1 (F: 5′-AGGTCCTTCAATGAGATCCCTT-3′ and R: 5′-TCCCTGTAAATGGGGCCATAC-3′)

Cyp19a1 (F: 5′-ATGTTCTTGGAAATGCTGAACCC-3′ and R: 5′-AGGACCTGGTATTGAAGACGAG-3′)

PgR (F: 5′-GGGGTGGAGGTCGTACAAG-3′ and R: 5′-GCGAGTAGAATGACAGCTCCTT-3′)

Inhba (F: 5′-TCACCATCCGTCTATTTCAGCA-3′ and R: 5′-CTTCCGAGCATCAACTACTTTCT-3′)

Ptgs2 (F: 5′-TGAGCAACTATTCCAAACCAGC-3′ and R: 5′-GCACGTAGTCTTCGATCACTATC-3′)

Lhcgr (F: 5′-CGCCCGACTATCTCTCACCTA-3′ and R: 5′-GACAGATTGAGGAGGTTGTCAAA-3′).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed according to the procedures described previously (Yuan et al., 2014). Briefly, ovaries were submerged in PBS plus 1% formaldehyde, minced and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Addition of 0.125 M glycine quenched the cross-linking reaction. Tissue pieces were then spun down and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Chromatin was then isolated by adding lysis buffer, followed by disruption with a Dounce homogenizer. Lysates were sonicated to an average size of ∼200–500 bp using QSonica’s Q800R sonicator system (20% amplitude, 10 s on and 20 s off for 10 min). For each ChIP reaction, a total of 10 μg of antibody (PPZ0506, Thermo Fisher) was added to the precleared chromatin and incubated overnight at 4∘C. Subsequently, 50 μl of Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen) was added to each ChIP reaction and incubated for 4 h at 4∘C. Dynabeads were washed with RIPA buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 0.7% Na-deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.5 M LiCl) three times and once with TE. Chromatin fragments were eluted, followed by reverse crosslinking and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. ChIP DNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5. Purified DNA was subjected to qPCR for assessing enrichment of specific genomic regions. Primers for each gene are as follows:

PgR (F: 5′-TCTACCCGCCATACCTTAACTA-3′ and R: 5′-CCAAAGACCAGCTCCACAA-3′)

Inhba (F: 5′-AGCCCAGAATATTCCACAGAAG-3′ and R: 5′-CTTTGGGAAAGCCTCCTCTC-3′)

Ptgs2 (F: 5′-GGAAAGACAGAGTCACCACTAC-3′ and R: 5′-GAAGCTCTTAGCTCGCAGTT-3′)

Lhcgr (F: 5′-AGAGAAGCTTCCTCAGGTTTG-3′ and R: 5′-GGCTGTCTTTGTTATCCCAGTA-3′).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with PrismPad 7 software (GraphPad Prism Software Inc). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Unless otherwise stated, statistical analyses was assessed using the two-tailed Student t-test assuming unequal variance. Threshold for statistical significance for each test was set at 95% confidence (p < 0.05).

Results

Establishment of an ERβ Y55 Mutant Mouse Strain

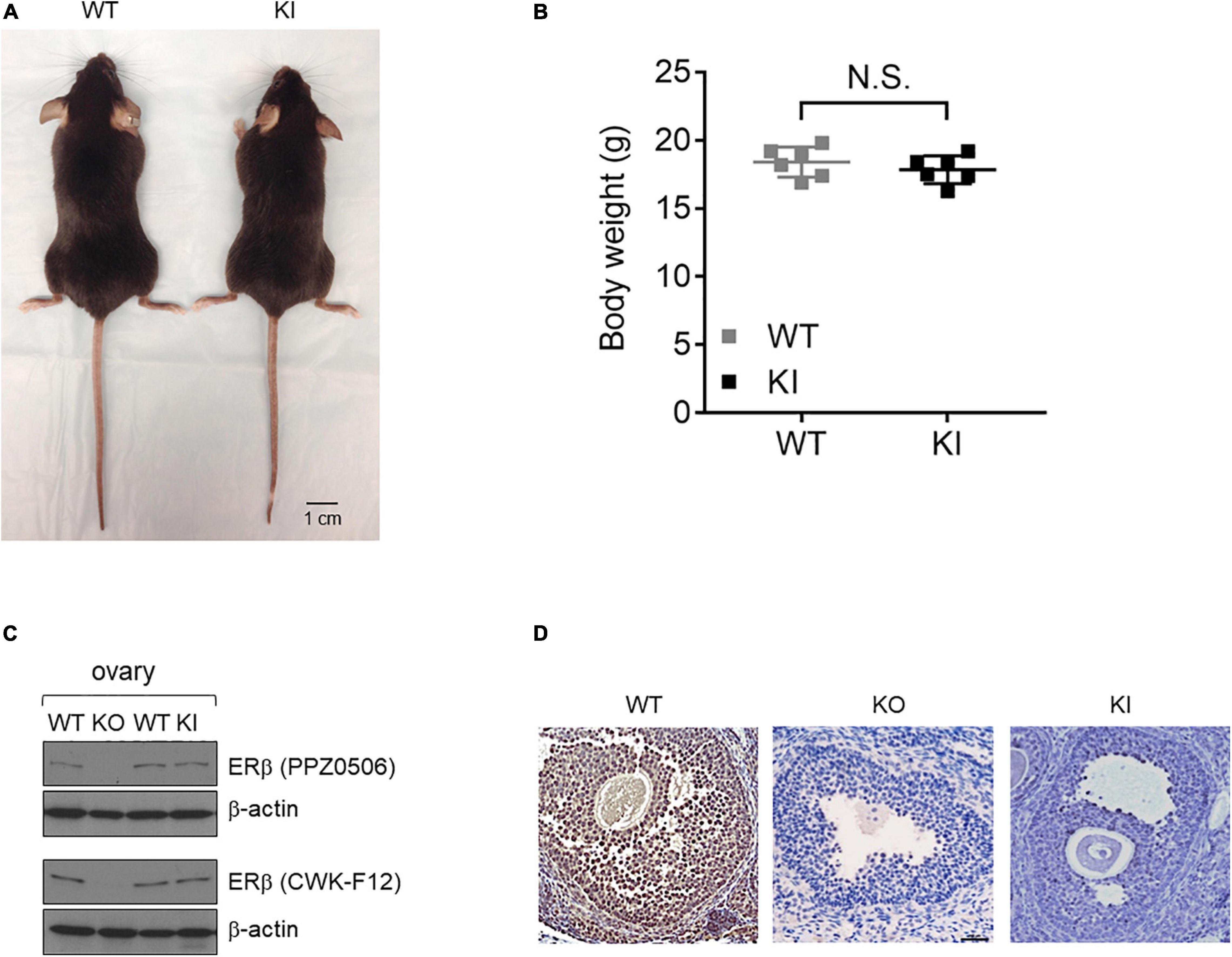

We used an ERβ Y55F whole body KI mouse line to investigate whether phosphorylation of site Y55 in mouse ERβ (Y36 in human, Supplementary Figure 1) plays a physiological role in ovarian development. Consistent with previously reported ERβ KO mice (Krege et al., 1998; Maneix et al., 2015), KI female mice had no obvious developmental defects and were indistinguishable in body size and weight from their WT littermates at 8-week old (Figures 1A,B, n = 6). For initial characterization of protein expression, we included a previously reported ERβ KO mouse model as control (Krege et al., 1998). ERβ protein expression in mutant ovaries was comparable to that in wild type ovaries based on results with two commercially available ERβ antibodies (Figure 1C). Levels of ERα, primarily expressed in theca cells, were not affected in KI ovaries (Supplementary Figure 2A). In addition, expression of c-Abl or EYA2, two upstream regulators of human ERβ Y36 phosphorylation (Yuan et al., 2014), was not altered either in KI or WT ovaries (Supplementary Figure 2A). Using an ERβ phosphotyrosine-specific antibody generated from our previous work (Yuan et al., 2014), we did not detect any appreciable IHC signal for phosphorylated ERβ in either KO or KI mutant mouse ovaries in contrast to the strong signals in wild type ovaries (Figure 1D). These results thus confirm genetic ablation of this particular tyrosine phosphorylation signaling in ERβ in KI ovarian tissue.

Figure 1. Generation and validation of the Esr2 Y55F KI animal model. (A) The gross appearances of KI (right) and WT (left) female mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bar, 1 cm. (B) WT and KI female mice body weight at 8-week old. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6; N.S.: Not Significant, Student’s t-test. (C) Western blot analysis of ovarian tissue extracts from ERβ KO, Y55F KI, and WT littermates. Two different commercial anti-ERβ antibodies were used. (D) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for ERβ pY55 in the ovaries from WT, ERβ KO, and Y55F KI mice (n = 6 per genotype). Scale bar, 100 μm.

The ERβ Phosphotyrosine Switch Is Important for Murine Ovarian Function

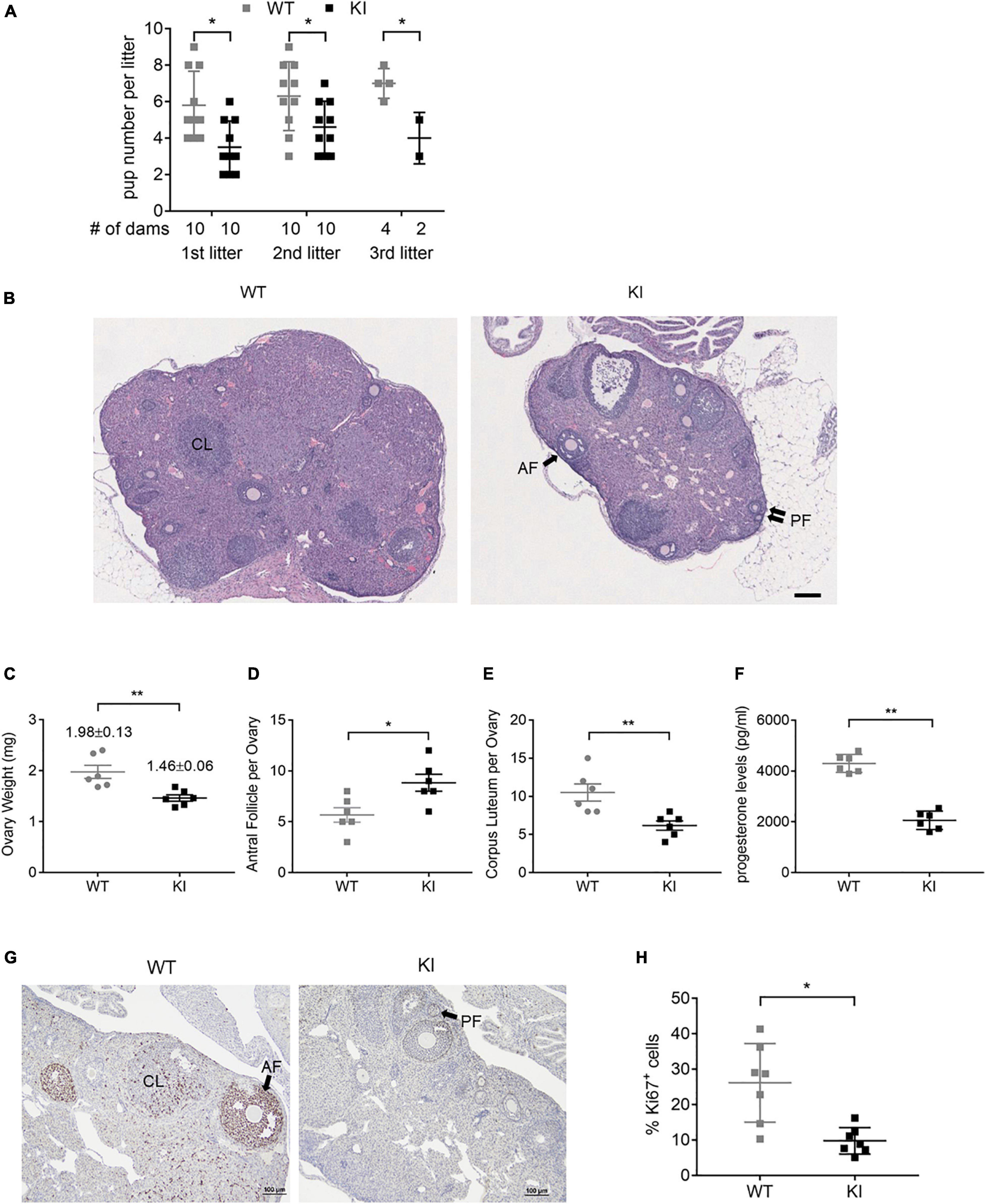

To assess the impact of Y55F mutation on female fertility, we carried out continuous mating of WT and KI female mice with young mature WT male mice over a 6-month period. KI dams had substantially reduced litter sizes compared to WT control in each of the three pregnancies observed during the time period analyzed (Figure 2A), while the frequency of pregnancy was similar between WT and mutant groups (data not shown). On average, KI dams had 4.2 ± 0.4 pups per litter, versus 6.4 ± 0.4 for WT (p < 0.01). The reduced fertility phenotype of KI mutant is consistent with previously reported fertility defect of Esr2 KO mice (3.1 ± 1.8 pups per litter; Krege et al., 1998). To further interrogate functional deficiency of KI mice, we treated age-matched WT and KI female littermates with PMSG and hCG consecutively to achieve superovulation. KI ovaries were smaller than their wild type counterparts, showed a diffusely luteinized stroma, and had significantly more antral follicles and fewer corpora lutea that were less demarcated from surrounding stromal cells compared to wild type ovaries (Figures 2B–E, n = 6). There was no statistical difference in hemorrhagic follicles between WT and KI ovaries by total count (Supplementary Figure 2B).

Figure 2. ERβ Y55 is important for murine ovarian functions. (A) Outcome of 6-month continuous mating for testing of female fertility. Results are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. (B) Representative H&E images of super-ovulated ERβ WT and KI ovaries. Scale bar, 100 μm. AF, antral follicle; PF, primary follicles; and CL, corpus luteum. (C) Mass of ovaries in WT and KI mice (n = 6) at the age of 8-week old. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. (D, E) Total number of antral follicle (D) and corpus luteum (E) per ovary from 6 ovaries of each genotype. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and Student’s t-test. (F) Plasma level of progesterone from WT and KI female mice at 8–10 weeks of age (n = 6). Values are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test. (G) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for the cell proliferation marker Ki67 in ovaries of WT and KI mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) Quantification of Ki67-positive granulosa cells in the ovaries of WT and KI mice (n = 7). Values are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

The ovary is the primary source of estrogen and progesterone synthesis in fertile females. As a measurement of this aspect of ovarian function, hormone concentrations in plasma serum were compared in WT and KI female mice. KI mice had normal circulating estrogen levels (Supplementary Figure 2C) but significantly lower progesterone levels versus WT (Figure 2F), which is consistent with the reduced litter size of KI dams. In addition, ovaries of KI mice displayed lower percentages of Ki67-positive granulosa cells compared to WT controls (Figures 2G,H, n = 7), indicating reduced cell proliferation.

Y55 Is Important for ERβ-Dependent Transcription in Ovarian Tissue

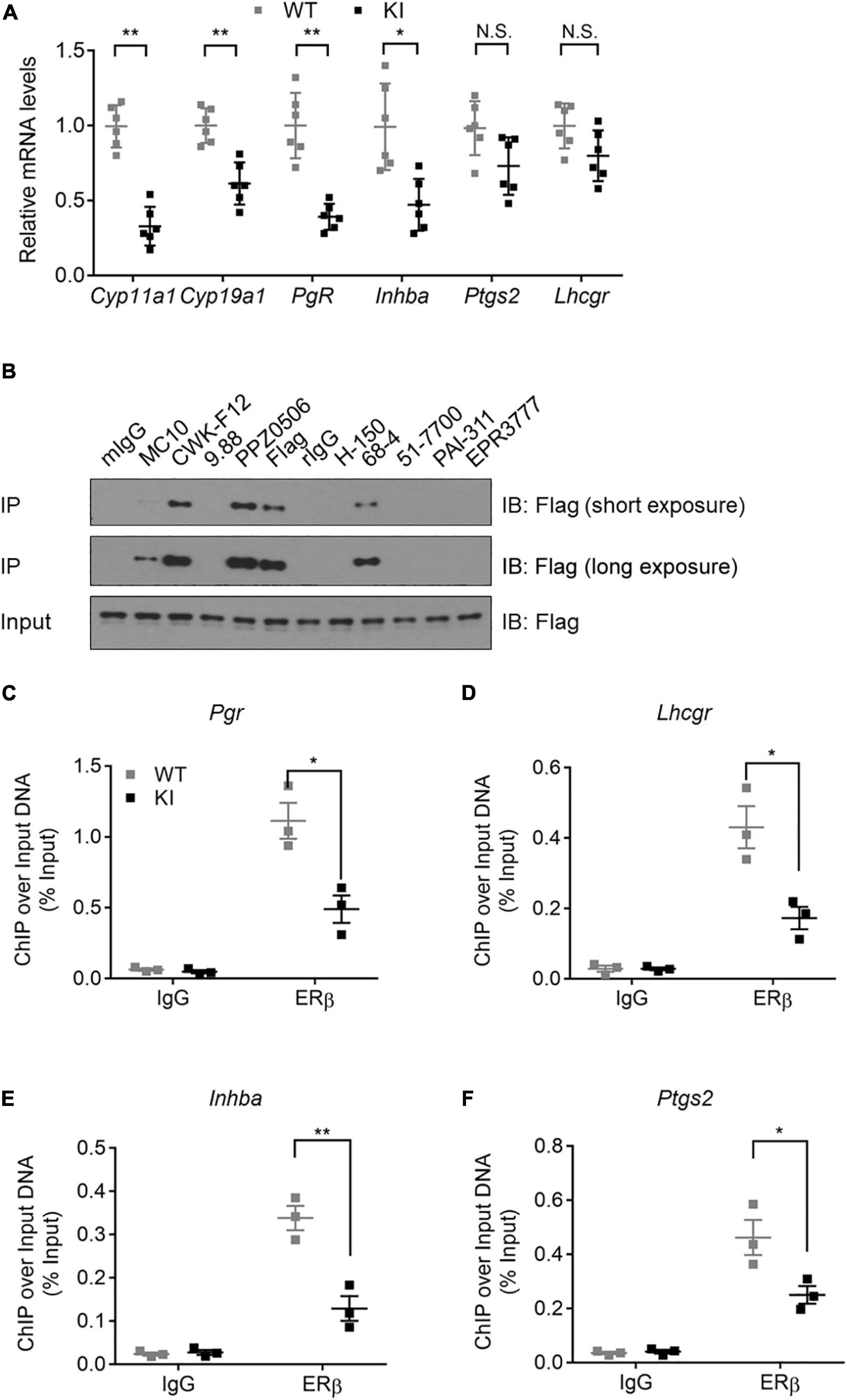

To determine the molecular defect associated with the Y55F mutant, we first asked whether Y55F mutation affects the relative abundance of ERβ in cytoplasm versus nucleus. Levels of Flag-tagged ERβ WT and Y55F protein were comparable in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (Supplementary Figure 2D). Next, we analyzed mRNA levels of several key steroidogenesis-related ERβ target genes in ovarian tissues of WT and KI mice. We found that KI mice exhibited reduced expression of Cyp11a1, Cyp19a1, progesterone receptor (Pgr), and Inhba as compared to their WT counterparts (Figure 3A). Levels of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2) and Lhcgr mRNA were also reduced in KI ovaries but the changes were not statistically significant (Figure 3A). We then determined the impact of the Y55F mutation on ERβ chromatin binding to its target transcription promoters. Due to the concerns over the specificity and IP efficiency of commercially available anti-ERβ antibodies (Weitsman et al., 2006; Andersson et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2017), we screened a panel of commercial anti-ERβ antibodies for their ability to IP FLAG-tagged mouse ERβ in human 293T cells (ERβ-negative). We found that anti-ERβ antibodies CWK-F12 and PPZ0506 gave rise to robust and specific ERβ IP signals (Figure 3B). Our result is consistent with a recent report regarding specific cross-reactivity of PPZ0506 against human and mouse ERβ proteins (Ishii et al., 2019). ChIP indicates that ERβ chromatin occupancy at the promoter regions of its target genes is substantially reduced in KI mutant ovaries (Figures 3C–F). Taken together, these data strongly support the notion that phosphotyrosine-dependent ERβ signaling regulates ERβ-dependent steroidogenic transcription program in mouse ovaries.

Figure 3. Y55 is important for ERβ transcriptional activity in murine ovaries. (A) Levels of mRNA for steroidogenesis genes in the ovaries from WT and KI mice (n = 6) after superovulation. N.S.: Not Significant, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and Student’s t-test. (B) IP-WB of 293T/Flag-mERβ cells with a panel of commercial anti-ERβ antibodies. (C–F) ChIP-qPCR analyses of ERβ occupancy near TSS of the Pgr (C), Lhcgr (D), Inhba (E), and Ptgs2 (F) genes in mouse ovaries from WT and KI mice. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and Student’s t-test.

Discussion

As nuclear hormone receptors, ERα and ERβ are involved in regulation of many complex physiological processes in humans and rodents (Paterni et al., 2014). For example, ERα promotes cell proliferation in an estrogen-dependent manner in the breast, whereas ERβ inhibits proliferation of multiple cancer cell types including breast, prostate and colon while facilitating granulosa cell differentiation during ovarian folliculogenesis. In contrast to the extensive literature on ERα function, how ERβ biological activity is regulated remains vastly under-explored. In the current study, we used a mouse genetic model to demonstrate a definitive role of an ERβ-specific phosphotyrosine switch in regulation of mouse ovarian functions including fertility, steroidogenesis, and ovarian transcription. However, we point out that our current study did not investigate the effect of ERβ Y55F mutation on the hypothalamus-pituitary axis. Therefore, the ovarian defects observed in whole-body KI mice could be contributed by lower gonadotropin secretion and subsequent reduction in follicle growth due to hypothalamus-pituitary dysfunction.

Three animal models for ERα phosphorylation site mutants were reported recently. Female mice carrying a mutant S122 ERα had a tissue-preferential impact on adipose tissue mass (Ohlsson et al., 2020). In a separate report, blocking of ERα Ser216 phosphorylation aggravated microglia activation and brain inflammation (Shindo et al., 2020). In a third study, dramatic developmental defects in the reproductive organs, mammary glands, and bones were observed in a Cre-inducible mouse model carrying an ERα Y541 mutation (ERα Y537S in humans; Simond et al., 2020). The ovarian phenotype of ERβ Y55F KI mice described in the current study extends the accumulating genetic evidence for the distinct impact of various PTMs on the physiological functions of the two ER isotypes in multiple tissues and organs.

In a previous study, loss of ERβ was shown to cause spontaneous granulosa cell tumors as well as pituitary tumors in 20 to 24 month-old female animals (Fan et al., 2010). The elevated incidence of pituitary tumors in ERβ KO mice was likely due to excessive secretion of gonadotropin releasing hormone from hypothalamus. No increased tumor incidence was observed in our Y55F KI mice up to 17 months of age. However, using transplant tumor models, we found that KI mice experienced compromised antitumor immunity and accelerated tumor growth (Yuan et al., 2021), suggesting a tumor-suppressive activity of host ERβ signaling.

ERβ, but not ERα, is known to be highly expressed in ovarian granulosa cells (Schomberg et al., 1999; Inzunza et al., 2007; Ishii et al., 2019). In response to gonadotropins, ERβ promotes transcriptional activation of multiple differentiation/steroidogenic genes including Cyp11a1, Cyp19a1, and Lhcgr. Cyp11a1 encodes the cytochrome P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage (P450scc) enzyme, which catalyzes conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone (Hu et al., 2004; Chien et al., 2013). This is the first step in steroidogenesis that specializes in steroid hormone production. Cyp19a1 encodes aromatase, an important enzyme in the aromatization of androgen to estrogen (Hanukoglu, 1992) and the rate-limiting step in estrogen biosynthesis. In addition, ERβ is required for expression of known LH-responsive genes such as Ptgs2 and Pgr (Couse et al., 2005; Emmen et al., 2005). Our mRNA analysis clearly shows that ERβ-dependent transcription of these steroidogenic genes is regulated by the Y55 phosphotyrosine switch. Our published work identifies c-Abl and EYA2 as the corresponding kinase and phosphatase that directly control the phosphorylation status of this molecular switch in human breast cancer cells (Yuan et al., 2014). Future work is needed to determine whether the same kinase/phosphatase pair is involved in regulation of ERβ functions via Y55 phosphorylation in mouse ovaries.

Due to technical limitation, whole ovaries instead of purified primary granulosa cells were used in our ERβ ChIP analysis. We recognize that reduced granulosa cell proliferation in KI ovaries could complicate the interpretation of our ERβ ChIP result. It will be important to confirm dynamics of ERβ chromatin binding in purified granulosa cell populations using more sensitive ChIP conditions.

Not all granulosa cell-related genes examined were down-regulated in KI ovaries. For example, Ptgs2 and Lhcgr mRNA levels were not significantly different in WT and KI ovaries. This could be due to the following reasons. LH transiently up-regulates Ptgs2 in granulosa cells of large antral follicles within 4 h (Carletti and Christenson, 2009), but its effect on Ptgs2 mRNA expression after 11 h differs in different studies (Joyce et al., 2001; Lee-Thacker et al., 2020). In addition, PTGS2 protein is also expressed in the interstitial cells of rat ovaries (Quintana et al., 2008). Regarding Lhcgr mRNA expression, it is known that FSH induces Lhcgr only in mural granulosa cells (Erickson et al., 1979; Law et al., 2013), which do not proliferate in response to FSH. Thus, the impact of granulosa cell growth defects on Lhcgr mRNA levels is likely to be less than on those genes that are uniformly expressed in granulosa cells. Additionally, Lhcgr is down-regulated in preovulatory granulosa cells and corpus luteum. Thus, the post-superovulation treatment may not be the best way to evaluate Lhcgr levels in KI ovaries.

Our previous cancer-related study shows that the ERβ-specific agonist S-equol elevates the same phosphotyrosine switch in cancer cells and antitumor CD8+ T cells and inhibits tumor growth in both xenograft and syngeneic tumor models (Yuan et al., 2016, 2021). S-equol is a natural compound with proven clinical safety and high tolerance in humans, based on multiple phase I and II clinical trials (Setchell et al., 2005; Jackson et al., 2011; Takeda et al., 2018). Our finding of the importance of this ERβ molecular switch in supporting ovarian functions raises the distinct possibility that S-equol could be explored for potential treatment of infertility and other related reproductive disorders.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), The George Washington University.

Author Contributions

RL conceived and supervised the project. RL and YH designed the experiments. BY, JY, and LD performed the experiments and analyzed the data. RL and BY wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants to RL (NIH HD091916 and CA206529) and YH (NIH CA212674 and DOD W81XWH-17-1-0007).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Susan Weintraub and Xiaoli Gao for their excellent technical assistance in hormone measurement, and Ms. Sabrina Smith for technical assistance.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.649087/full#supplementary-material

References

Andersson, S., Sundberg, M., Pristovsek, N., Ibrahim, A., Jonsson, P., Katona, B., et al. (2017). Insufficient antibody validation challenges oestrogen receptor beta research. Nat. Commun. 8:15840. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15840

Antal, M. C., Krust, A., Chambon, P., and Mark, M. (2008). Sterility and absence of histopathological defects in nonreproductive organs of a mouse ERbeta-null mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 2433–2438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712029105

Carletti, M. Z., and Christenson, L. K. (2009). Rapid effects of LH on gene expression in the mural granulosa cells of mouse periovulatory follicles. Reproduction 137, 843–855. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0457

Cheng, X., Cole, R. N., Zaia, J., and Hart, G. W. (2000). Alternative O-glycosylation/O-phosphorylation of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Biochemistry 39, 11609–11620. doi: 10.1021/bi000755i

Cheung, E., Acevedo, M. L., Cole, P. A., and Kraus, W. L. (2005). Altered pharmacology and distinct coactivator usage for estrogen receptor-dependent transcription through activating protein-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 102, 559–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407113102

Chien, Y., Cheng, W. C., Wu, M. R., Jiang, S. T., Shen, C. K., and Chung, B. C. (2013). Misregulated progesterone secretion and impaired pregnancy in Cyp11a1 transgenic mice. Biol. Reprod 89:91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.110833

Couse, J. F., and Korach, K. S. (1999). Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 20, 358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370

Couse, J. F., Yates, M. M., Deroo, B. J., and Korach, K. S. (2005). Estrogen receptor-beta is critical to granulosa cell differentiation and the ovulatory response to gonadotropins. Endocrinology 146, 3247–3262. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0213

Couse, J. F., Yates, M. M., Walker, V. R., and Korach, K. S. (2003). Characterization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in estrogen receptor (ER) Null mice reveals hypergonadism and endocrine sex reversal in females lacking ERalpha but not ERbeta. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1039–1053. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0398

Dupont, S., Krust, A., Gansmuller, A., Dierich, A., Chambon, P., and Mark, M. (2000). Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development 127, 4277–4291.

Emmen, J. M., and Korach, K. S. (2003). Estrogen receptor knockout mice: phenotypes in the female reproductive tract. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 17, 169–176.

Emmen, J. M., Couse, J. F., Elmore, S. A., Yates, M. M., Kissling, G. E., and Korach, K. S. (2005). In vitro growth and ovulation of follicles from ovaries of estrogen receptor (ER){alpha} and ER{beta} null mice indicate a role for ER{beta} in follicular maturation. Endocrinology 146, 2817–2826. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1108

Erickson, G. F., Wang, C., and Hsueh, A. J. (1979). FSH induction of functional LH receptors in granulosa cells cultured in a chemically defined medium. Nature 279, 336–338. doi: 10.1038/279336a0

Fan, X., Gabbi, C., Kim, H. J., Cheng, G., Andersson, L. C., Warner, M., et al. (2010). Gonadotropin-positive pituitary tumors accompanied by ovarian tumors in aging female ERbeta-/- mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 6453–6458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002029107

Hanukoglu, I. (1992). Steroidogenic enzymes: structure, function, and role in regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 779–804. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90307-5

Hong, H., Yen, H. Y., Brockmeyer, A., Liu, Y., Chodankar, R., Pike, M. C., et al. (2010). Changes in the mouse estrus cycle in response to BRCA1 inactivation suggest a potential link between risk factors for familial and sporadic ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 221–228. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3232

Hu, M. C., Hsu, H. J., Guo, I. C., and Chung, B. C. (2004). Function of Cyp11a1 in animal models. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 215, 95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.024

Inzunza, J., Morani, A., Cheng, G., Warner, M., Hreinsson, J., Gustafsson, J. A., et al. (2007). Ovarian wedge resection restores fertility in estrogen receptor beta knockout (ERbeta-/-) mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 104, 600–605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608951103

Ishii, H., Otsuka, M., Kanaya, M., Higo, S., Hattori, Y., and Ozawa, H. (2019). Applicability of Anti-Human Estrogen Receptor beta Antibody PPZ0506 for the Immunodetection of Rodent Estrogen Receptor beta Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:ijms20246312. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246312

Jackson, R. L., Greiwe, J. S., and Schwen, R. J. (2011). Emerging evidence of the health benefits of S-equol, an estrogen receptor beta agonist. Nutr. Rev. 69, 432–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00400.x

Joyce, I. M., Pendola, F. L., O’Brien, M., and Eppig, J. J. (2001). Regulation of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in mouse granulosa cells during ovulation. Endocrinology 142, 3187–3197. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8268

Krege, J. H., Hodgin, J. B., Couse, J. F., Enmark, E., Warner, M., Mahler, J. F., et al. (1998). Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 95, 15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677

Lam, H. M., Suresh Babu, C. V., Wang, J., Yuan, Y., Lam, Y. W., Ho, S. M., et al. (2012). Phosphorylation of human estrogen receptor-beta at serine 105 inhibits breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 358, 27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.012

Law, N. C., Weck, J., Kyriss, B., Nilson, J. H., and Hunzicker-Dunn, M. (2013). Lhcgr expression in granulosa cells: roles for PKA-phosphorylated beta-catenin, TCF3, and FOXO1. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1295–1310. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1025

Lee-Thacker, S., Jeon, H., Choi, Y., Taniuchi, I., Takarada, T., Yoneda, Y., et al. (2020). Core Binding Factors are essential for ovulation, luteinization, and female fertility in mice. Sci. Rep. 10:9921. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64257-0

Madak-Erdogan, Z., Charn, T. H., Jiang, Y., Liu, E. T., Katzenellenbogen, J. A., and Katzenellenbogen, B. S. (2013). Integrative genomics of gene and metabolic regulation by estrogen receptors alpha and beta, and their coregulators. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9:676. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.28

Maneix, L., Antonson, P., Humire, P., Rochel-Maia, S., Castaneda, J., Omoto, Y., et al. (2015). Estrogen receptor beta exon 3-deleted mouse: The importance of non-ERE pathways in ERbeta signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 112, 5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504944112

Nelson, A. W., Groen, A. J., Miller, J. L., Warren, A. Y., Holmes, K. A., Tarulli, G. A., et al. (2017). Comprehensive assessment of estrogen receptor beta antibodies in cancer cell line models and tissue reveals critical limitations in reagent specificity. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 440, 138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.016

Ohlsson, C., Gustafsson, K. L., Farman, H. H., Henning, P., Lionikaite, V., Moverare-Skrtic, S., et al. (2020). Phosphorylation site S122 in estrogen receptor alpha has a tissue-dependent role in female mice. FASEB J. 2020:201901376RR. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901376RR

O’Lone, R., Frith, M. C., Karlsson, E. K., and Hansen, U. (2004). Genomic targets of nuclear estrogen receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1859–1875. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0044

Paterni, I., Granchi, C., Katzenellenbogen, J. A., and Minutolo, F. (2014). Estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids 90, 13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012

Pelletier, G., Labrie, C., and Labrie, F. (2000). Localization of oestrogen receptor alpha, oestrogen receptor beta and androgen receptors in the rat reproductive organs. J. Endocrinol. 165, 359–370. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650359

Picard, N., Charbonneau, C., Sanchez, M., Licznar, A., Busson, M., Lazennec, G., et al. (2008). Phosphorylation of activation function-1 regulates proteasome-dependent nuclear mobility and E6-associated protein ubiquitin ligase recruitment to the estrogen receptor beta. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 317–330. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0281

Quintana, R., Kopcow, L., Marconi, G., Young, E., Yovanovich, C., and Paz, D. A. (2008). Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) by meloxicam decreases the incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in a rat model. Fertil. Steril. 90(4 Suppl.), 1511–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.028

Sar, M., and Welsch, F. (1999). Differential expression of estrogen receptor-beta and estrogen receptor-alpha in the rat ovary. Endocrinology 140, 963–971. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6533

Saville, B., Wormke, M., Wang, F., Nguyen, T., Enmark, E., Kuiper, G., et al. (2000). Ligand-, cell-, and estrogen receptor subtype (alpha/beta)-dependent activation at GC-rich (Sp1) promoter elements. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5379–5387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5379

Schomberg, D. W., Couse, J. F., Mukherjee, A., Lubahn, D. B., Sar, M., Mayo, K. E., et al. (1999). Targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor-alpha gene in female mice: characterization of ovarian responses and phenotype in the adult. Endocrinology 140, 2733–2744. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.6.6823

Setchell, K. D., Clerici, C., Lephart, E. D., Cole, S. J., Heenan, C., Castellani, D., et al. (2005). S-equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor beta, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1072

Shindo, S., Chen, S. H., Gotoh, S., Yokobori, K., Hu, H., Ray, M., et al. (2020). Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylated at Ser216 confers inflammatory function to mouse microglia. Cell Commun. Signal. 18:117. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00578-x

Simond, A. M., Ling, C., Moore, M. J., Condotta, S. A., Richer, M. J., and Muller, W. J. (2020). Point-activated ESR1(Y541S) has a dramatic effect on the development of sexually dimorphic organs. Genes Dev. 34, 1304–1309. doi: 10.1101/gad.339424.120

Stender, J. D., Kim, K., Charn, T. H., Komm, B., Chang, K. C., Kraus, W. L., et al. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor alpha DNA binding and tethering mechanisms identifies Runx1 as a novel tethering factor in receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 3943–3955. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00118-10

St-Laurent, V., Sanchez, M., Charbonneau, C., and Tremblay, A. (2005). Selective hormone-dependent repression of estrogen receptor beta by a p38-activated ErbB2/ErbB3 pathway. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 94, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.02.001

Takeda, T., Shiina, M., and Chiba, Y. (2018). Effectiveness of natural S-equol supplement for premenstrual symptoms: protocol of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open 8:e023314. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023314

Tharun, I. M., Nieto, L., Haase, C., Scheepstra, M., Balk, M., Mocklinghoff, S., et al. (2015). Subtype-specific modulation of estrogen receptor-coactivator interaction by phosphorylation. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 475–484. doi: 10.1021/cb5007097

Tremblay, A., and Giguere, V. (2001). Contribution of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and CREB binding protein in ligand-independent activity of estrogen receptor beta. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 77, 19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00031-0

Tremblay, A., Tremblay, G. B., Labrie, F., and Giguere, V. (1999). Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor beta through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Mol. Cell 3, 513–519. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80479-7

Vivar, O. I., Zhao, X., Saunier, E. F., Griffin, C., Mayba, O. S., Tagliaferri, M., et al. (2010). Estrogen receptor beta binds to and regulates three distinct classes of target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22059–22066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114116

Warner, M., Wu, W. F., Montanholi, L., Nalvarte, I., Antonson, P., and Gustafsson, J. A. (2020). Ventral prostate and mammary gland phenotype in mice with complete deletion of the ERbeta gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 117, 4902–4909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920478117

Weitsman, G. E., Skliris, G., Ung, K., Peng, B., Younes, M., Watson, P. H., et al. (2006). Assessment of multiple different estrogen receptor-beta antibodies for their ability to immunoprecipitate under chromatin immunoprecipitation conditions. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 100, 23–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9229-5

Yuan, B., Cheng, L., Chiang, H. C., Xu, X., Han, Y., Su, H., et al. (2014). A phosphotyrosine switch determines the antitumor activity of ERbeta. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3378–3390. doi: 10.1172/JCI74085

Yuan, B., Cheng, L., Gupta, K., Chiang, H. C., Gupta, H. B., Sareddy, G. R., et al. (2016). Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates ERbeta ubiquitination, protein turnover, and inhibition of breast cancer. Oncotarget 7, 42585–42597. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10018

Yuan, B., Clark, C. A., Wu, B., Yang, J., Drerup, J. M., Li, T., et al. (2021). Estrogen receptor beta signaling in CD8(+) T cells boosts T cell receptor activation and antitumor immunity through a phosphotyrosine switch. J. Immunother. Cancer 9:001932. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001932

Keywords: estrogen receptor beta, knock-in, ovary, follicle, fertility

Citation: Yuan B, Yang J, Dubeau L, Hu Y and Li R (2021) A Phosphotyrosine Switch in Estrogen Receptor β Is Required for Mouse Ovarian Function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:649087. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.649087

Received: 13 January 2021; Accepted: 16 March 2021;

Published: 09 April 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer R. Wood, University of Nebraska System, United StatesReviewed by:

John Hawse, Mayo Clinic, United StatesTakeshi Kurita, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Yuan, Yang, Dubeau, Hu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rong Li, cmxpNjlAZ3d1LmVkdQ==; Bin Yuan, eXVhbmJpbkBnd3UuZWR1

Bin Yuan

Bin Yuan Jing Yang1

Jing Yang1 Louis Dubeau

Louis Dubeau Rong Li

Rong Li