- Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany

The septins are a conserved family of GTP-binding proteins present in all eukaryotic cells except plants. They were originally discovered in the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae that serves until today as an important model organism for septin research. In yeast, the septins assemble into a highly ordered array of filaments at the mother bud neck. The septins are regulators of spatial compartmentalization in yeast and act as key players in cytokinesis. This minireview summarizes the recent findings about structural features and cell biology of the yeast septins.

The classical Hartwell screen revealed genes involved in cell cycle regulation of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hartwell, 1971). Beside many others, the screen showed mutations in the four genes CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, and CDC12 (cell division cycle). These were later classified as members of the septins, a new family of cytoskeletal proteins in the budding yeast (Sanders and Field, 1994; Pringle, 2008). Another mitotic septin, Shs1 (seventh homolog of septin), was identified more than two decades after the initial screen (Mino et al., 1998). In meiosis, Cdc11 and Cdc12 are replaced by two other septins, Spr28 and Spr3, respectively (Ozsarac et al., 1995; De Virgilio et al., 1996). These two septins are expressed under an own promoter and the resulting meiosis-specific septin complexes exhibit distinct functionalities than their mitotic counterparts (Garcia et al., 2016). In this review we will focus on the mitotic septins.

The mitotic yeast septin proteins can be recombinantly expressed and purified from E. coli (Bertin et al., 2008; Renz et al., 2013). Analysis of mutated or truncated recombinant septin preparations uncovered the organization of the individual subunits: They assemble into hetero-oligomers, called rods, with the order Cdc11-Cdc12-Cdc3-Cdc10-Cdc10-Cdc3-Cdc12-Cdc11 with Shs1 sometimes replacing the terminal subunit Cdc11 (Bertin et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2011). These rods appear in vitro as short filaments of 32 nm length under high salt conditions (Kaplan et al., 2015). Septin rods can be induced to form long septin filaments in vitro by lowering the salt concentration of a buffer that otherwise keeps the rods stable in solution (Bertin et al., 2008; Renz et al., 2013). These filaments are about 1.5 μM long and exhibit a thickness within the range observed for microtubuli (Kaplan et al., 2015). Hexameric rods lacking the terminal subunit Cdc11 fail to form filaments suggesting that filament formation occurs end-over-end via the terminal subunit Cdc11 (Bertin et al., 2010). This observation was further fostered by applying single molecule localization microscopy to rods with their central and terminal subunits labeled with fluorescent dyes (Kaplan et al., 2015). Another study using septin preparations labeled with suitable FRET donor and acceptor dyes confirmed the end-over-end assembly via Cdc11 and showed that this interaction has a high affinity with a KD in the nano-molar range (Booth et al., 2015). Alternative modes for filament formation via other subunit contacts could be excluded by evaluation of different combinations of subunits labeled with the FRET compatible dyes (Booth et al., 2015).

Septin octamers containing Shs1 instead of Cdc11 as terminal subunit do not form linear filaments in vitro but rather curved bundles that assemble into closed rings (Garcia et al., 2011) suggesting that Shs1 is necessary to form also curved structures in vivo. Recombinant septin rods exclusively capped with Shs1 do not assemble end-over-end into filaments whereas Shs1-Cdc11 contacts are formed in vitro (Booth et al., 2015).

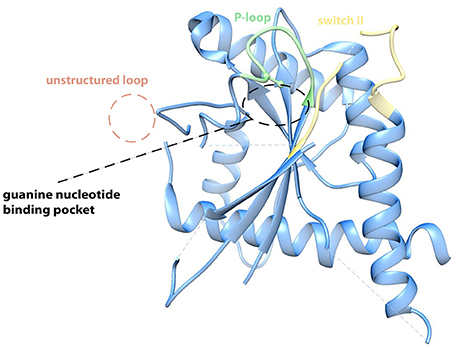

Crystal structures of the human subunits SEPT2 and SEPT7 provided invaluable insight into the architecture of subunit contacts and filament formation (Sirajuddin et al., 2007, 2009; Zent et al., 2011). Structurally, septins are GTP-binding proteins sharing similarities with the small GTPases of the Ras family (Leipe et al., 2002). A central conserved G-domain is flanked by variable N- and C-terminal extensions. The G-domain core resembles the conserved Ras structure with six β-strands and five α-helices. Structural elements from Ras like the switch I and switch II motifs and the P-loop (Schweins and Wittinghofer, 1994) classify the septins as bona fide GTPases. Besides these canonical structural elements, the septin G-domain harbors a septin unique element at its C-terminus that forms a distinct α-helix, α6 following the domain nomenclature from Ras, which points away from the G-domain in a 90° angle. Other septin specific features are the presence of a short N-terminal helix, α0, and a distinct loop with two antiparallel strands β7 and β8.

The crystal structure of a septin filament consisting of SEPT7, SEPT6, and SEPT2 revealed the nature of the binding interface of the septin subunits within the filament (Sirajuddin et al., 2007): Interactions between two adjacent G-domains (called G-interface) alternate with interactions of two adjacent N- and C-termini of two subunits (called NC-interface). The filament subunit is a hexamer with the order SEPT7-SEPT6-SEPT2-SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7. Here SEPT7 forms a G-interace with SEPT6, SEPT6, and SEPT2 form a NC-interface, SEPT2 and SEPT2 a G-interface and so on. The α6 helix is the prominent element of the NC-interface. C-terminal extensions like predicted coiled-coils do not seem to contribute to the NC-interface (Sirajuddin et al., 2007). The G-interface is composed of a complex network of interactions between different amino acid residues of the respective opposite subunit. Especially the interacting Val, His, and Trp residues located in the β7 and β8 sheets are highly conserved among human and fungal septins. Based on the high sequence homology between fungal and human septins one would assume that the architecture of the G-interface is shaped similarly in yeast septins. However, in the recently solved crytsal structure of Cdc11 (Brausemann et al., 2016, Figure 1), the terminal subunit of the S. cerevisiae septin rod, the loop containing the β7 and β8 sheets is not structured and the base of the loop points away from the presumed G-interface in an approximetaly 90° angle (Figure 1). This, together with the finding that Cdc11 dimers are maintained via the C-terminal coiled-coil extensions of the Cdc11 monomers and not via a NC- or G-interface, suggests that at least some yeast septins have interaction interfaces that might differ from the “classic” NC- and G-interfaces from the human septins.

Figure 1. Crystal structure of Cdc1120−298 (PDB-ID 5AR1). The protein crystallized in its apo form. The P-loop, the switch II loop and the anti-parallel ß7–ß8 sheets contribute to the G-binding interface in the human SEPT2 and SEPT7 (Sirajuddin et al., 2007; Zent et al., 2011). In the Cdc11 crystal the ß7–ß8 hairpin is unstructured and points away from the binding interface in a 90° angle, whereas P-loop (green) and switch II region (yellow) show high similarities. An arginine within the P-loop of Cdc11 possibly hinders effective binding of a nucleotide and thereby possibly explains why Cdc11 is incapable of binding a nucleotide (Brausemann et al., 2016). Figure created with Chimera vers. 1.10.2. from PDB structure 5AR1.

Cdc11 exhibits one more unique feature: The crystal structure is from the apo form and does consequently not contain a nucleotide (Brausemann et al., 2016). All yeast and human septins harbor an absolute conserved lysine residue in the canonical P-loop sequence GXXXXGKS/T. The P-loop is usually in contact with the β-phosphate of the bound GTP or GDP. Instead of the conserved lysine, Cdc11 has an arginine in this position of the P-loop whose side chain would collide with the β-phosphate of any bound nucleotide (Figure 1). Is Cdc11 not capable of binding a nucleotide? This assumption is fostered by the finding that cells expressing cdc11 alleles that contain mutants in the P-loop show wild type like phenotype at 30°C (Casamayor and Snyder, 2003). Furthermore, only Cdc10 and Cdc12 have been shown to bind and hydrolyze GTP whereas GTPase activity could not be shown for Cdc3 and Cdc11 (Versele and Thorner, 2004).

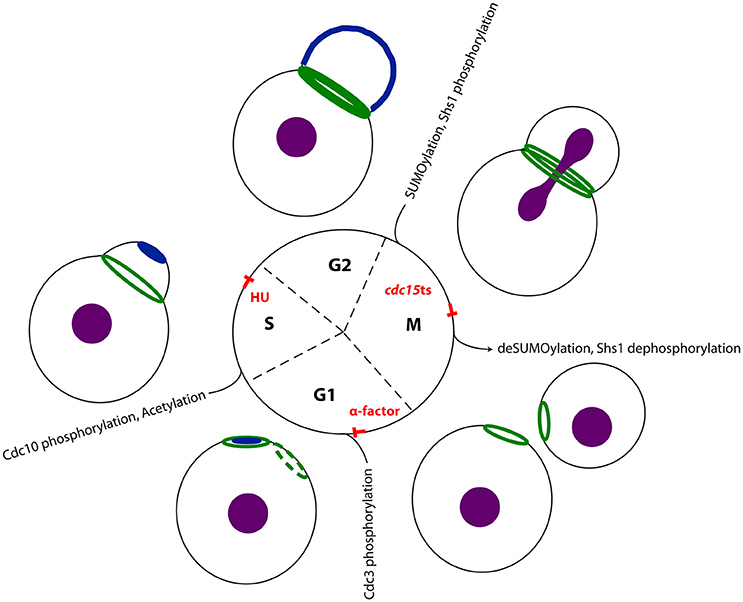

In the living yeast cell, the septin filaments assemble at the bud neck in an organized array, the so-called septin ring. This ring undergoes different cell cycle dependent architectural transitions (Figure 2). In early G1-phase, the septins are recruited to and accumulate at the presumptive bud site in a patch-like structure. Shortly before bud emergence, the septins assemble in a Cdc42 dependent manner into a ring marking the future site of bud growth and cytokinesis (Gladfelter et al., 2002; Caviston et al., 2003; Iwase et al., 2006). This initial recruitment of the septins to the future bud site depends besides Cdc42 on its effectors Gic1 and Gic2, and the action of the cyclin-dependent kinases Cdc28 and Pho85 (Tang and Reed, 2002; Iwase et al., 2006; Egelhofer et al., 2008; Okada et al., 2013). Evaluation of the mechanisms underlying the annealing of recombinant septin rods and formation of filaments on lipid bilayers suggests that septin filaments are formed in vivo at the plasma membrane from small complexes that diffuse in two dimensions (Bridges et al., 2014). Initial recruitment to the plasma membrane is supposed to be mediated by phospholipids. In an in vitro lipid monolayer model PIP2 enhanced the filament assembly rate of septin hetero-octamers (Bertin et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Septins in the cell cycle of S. cerevisiae. The septins undergo cell cycle depending transitions: In G1 phase active Cdc42 (dark blue) polarizes at the plasma membrane, defining the presumptive bud site. The septins (dark green) are recruited to this site and remain as a ring at the neck upon bud emergence. This ring expands into a stable hourglass-shaped collar until the onset of mitosis. In late anaphase the septin collar splits into two distinct rings. In a recent study, Renz et al. detected interaction partners systematically at different stages of the cell cycle and could thereby reconstitute a time-resolved interactome of the septin rod (Renz et al., 2016). Treatment of the yeast cells with alpha factor arrested cells in early G1 phase, where no septin structure was visible. Using hydroxyurea arrested the cells in S-phase, where a stable septin ring was visible at the bud neck. Finally, a temperature shift in cells carrying a cdc15-1 allele, allowed determining interaction partners with split septin rings. The respective cell cylce blocks and major known post translational modifications (Hernández-Rodríguez and Momany, 2012) of the respecive cell cycle state are indicated. The nucleus is colored in purple.

After bud formation, the septin ring expands into a stable hourglass-shaped collar that is present at the bud neck until the onset of mitosis (Vrabioiu and Mitchison, 2006; Oh and Bi, 2011; Ong et al., 2014). Before cytokinesis, the septin collar splits into two distinct rings, one located at the mother and one at the daughter site of the bud neck. The contractile actomyosin ring (AMR), which powers the ingression of the cleavage furrow and septum formation, is assembled between the two septin rings (Wloka and Bi, 2012). Myo1, one essential constituent of the AMR, is recruited to the site of cytokinesis via the septin interacting protein Bni5 (Fang et al., 2010; Schneider et al., 2013). Bni5 in turn associates with the C-terminal extensions of the septin subunits Cdc11 and Shs1 (Finnigan et al., 2015).

After completion of cell separation, the old septin rings are disassembled and septin subunits are partially replaced and recycled for the next round of the cell cycle (McMurray and Thorner, 2008).

Taken together, the septins act mainly as scaffold for other proteins that are recruited to the bud neck or the site of cytokinesis, respectively. Additionally, the septins function as a diffusion barrier for proteins and organelles at the cortex of the bud neck (Luedeke et al., 2005; Shcheprova et al., 2008; Caudron and Barral, 2009; Orlando et al., 2011).

The transitions that the septins undergo throughout the cell cycle are supposed to be regulated by posttranslational modifications: Transition of the septin ring into a stable septin collar after bud emergence is associated with the phosphorylation and acetylation of certain subunits (Mitchell et al., 2011; Hernández-Rodríguez and Momany, 2012). For example, the p21-activated kinase Cla4 phosphorylates Cdc10 after bud emergence and a deletion of CLA4 strongly affects the timely formation of septin structures (Dobbelaere et al., 2003; Kadota et al., 2004; Versele and Thorner, 2004). The splitting of the septin collar at the onset of cytokinesis is supposed to be initiated by a collective switch in the orientation of the septin filaments from parallel to perpendicular to the growth axis of the cell (DeMay et al., 2011). The switch is accompanied by at least two different modifications. First, the bud neck kinase Gin4 phosphorylates Shs1 at residues different from those being modified in G1-phase (Mortensen et al., 2002). Gin4 is recruited together with the septins to the presumptive bud site, co-localizes with the septins at the bud neck for the complete cell cycle and disappears from the bud neck after splitting of the septin collar (Longtine et al., 1998; Mortensen et al., 2002; Au Yong et al., 2016). Second, the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) Smt3 is covalently attached to Cdc3, Cdc11, and Shs1 at the mother site of the bud (Johnson and Blobel, 1999). Phosphorylation events play apparently an important role in septin structure transitions and septin organization and several more kinases have been identified to interact with the septins: Gin4 (Dobbelaere et al., 2003), Kcc4 (Okuzaki and Nojima, 2001; Kozubowski et al., 2005), Ste20 (Ptacek et al., 2005), Hsl1 (Finnigan et al., 2016), Elm1 (Kang et al., 2016), and Kin2, the ortholog of animal MARK/PAR-1 kinase (Yuan et al., 2016), were all identified as septin interactors.

However, for most of these regulatory proteins the exact timing of the interaction with the septins remains unknown and one can speculate that much more interactions exist but are not identified so far. Recently, Renz et al., performed a systematic screen for septin interaction partners throughout the cell cycle by combining cell cycle synchronization at stages with a distinct septin structure (Figure 2) with quantitative mass spectrometry to timely resolve the septin interactome (Renz et al., 2016). Yeast cells were synchronized in G1 phase with alpha factor, in S phase with hydroxyurea and in late anaphase with the help of a tempertaure sensitive cdc15 allele. This strategy allowed to link interaction partners to specific transition states of septin structures. Distinct sets of regulatory proteins were found to interact with the septins at certain stages of the cell cycle: Gin4 and the anillin-like protein Bud4, a known septin interactor (Kang et al., 2013), were identified both in S-phase and anaphase. The kinases Hsl1, Mck1, and Prk1 are specifically associated with the septins in S-phase cells. Ste20 and yeast SUMO (Smt3) were only identified as specific septin interactors in cells with split septin rings. An activity of Mck1 and Prk1 on the septins has not been reported and remains to be confirmed by supplementary studies. This screen strengthened also evidence that septins play a role in endocytosis: Syp1 is a negative regulator of the WASP-Arp23 complex and involved in endocytic site formation, but was also classified as septin organizing protein (Qiu et al., 2008; Merlini et al., 2015). It interacts with the septins in anaphase (Renz et al., 2016). In S-phase, the septins interact with Sla2, an adaptor protein that links actin to clathrin and endocytosis (Skruzny et al., 2015). In alpha facor arrested cells, Vps1 interacts with the septins (Renz et al., 2016). Vps1 is a dynamin related protein that functions at several stages of membrane trafficking including endocytic scission (Smaczynska-de Rooij et al., 2010, 2015).

The septins influence the composition of the ER at the bud neck and thereby render diffusion of ER membrane proteins from mother to bud. Septins, septin dependent kinases, the membrane protein Bud6 and sphingolipids were shown to be required for the ER diffusion barrier (Luedeke et al., 2005; Clay et al., 2014). Interestingly, the published septin interactome contains a hit for Erp1 (Renz et al., 2016), a member of the p24 complex that was reported to be involved in ER retention and ER-Golgi transport (Copic et al., 2009). Another constituent of COPII vesicles that interacts with p24 family members, Sfb3/Lpt1 (Manzano-Lopez et al., 2015), was additionally identified in the MS screen. These findings support the previsously published model of a septin dependent ER diffusion barrier.

Recapitulatory, the past few years have witnessed a considerable increase of published results concerning yeast septins, the majority of these in budding yeast. Efforts were made in all areas of septin biology, from structural investigations using EM, light microscopy and X-ray diffraction to reconstruction of septin assembly in complex in vitro systems and to elucidation of septin related processes in the living cell. All these studies together establish and/or approve the budding yeast as a prime model organism for septin research. While structural information of several of the human septin subunits is now avaliable (the PDB provides crystal structures for SEPT2, SEPT7, SEPT9, SEPT3 and the septin trimer 2/6/7), only one structure from a yeast septin was solved (Cdc11). Structure determination, the evaluation of the role of posttranslational modifications of the septins and the uncovering of so far unknown septin related processes in the living cell will represent the challenges for septin biologists for the next decade.

Author Contributions

TG and OG wrote the manuscript. OG prepared the figures.

Funding

OG was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant JO 187/8-1.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Au Yong, J. Y., Wang, Y. M., and Wang, Y. (2016). The Nim1 kinase Gin4 has distinct domains crucial for septin assembly, phospholipid binding and mitotic exit. J. Cell Sci. 129, 2744–2756. doi: 10.1242/jcs.183160

Bertin, A., McMurray, M. A., Grob, P., Park, S. S., Garcia, G. III. Patanwala, I., et al. (2008). Saccharomyces cerevisiae septins: supramolecular organization of heterooligomers and the mechanism of filament assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8274–8279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803330105

Bertin, A., McMurray, M. A., Thai, L., Garcia, G. III. Votin, V., Grob, P., et al. (2010). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 711–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.002

Booth, E. A., Vane, E. W., Dovala, D., and Thorner, J. (2015). A Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based system provides insight into the ordered assembly of yeast septin hetero-octamers. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28388–28401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.683128

Brausemann, A., Gerhardt, S., Schott, A. K., Einsle, O., Große-Berkenbusch, A., Johnsson, N., et al. (2016). Crystal structure of Cdc11, a septin subunit from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.01.004

Bridges, A. A., Zhang, H., Mehta, S. B., Occhipinti, P., Tani, T., and Gladfelter, A. S. (2014). Septin assemblies form by diffusion-driven annealing on membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 2146–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314138111

Casamayor, A., and Snyder, M. (2003). Molecular dissection of a yeast septin: distinct domains are required for septin interaction, localization, and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2762–2777. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2762-2777.2003

Caudron, F., and Barral, Y. (2009). Septins and the lateral compartmentalization of eukaryotic membranes. Dev. Cell 16, 493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.003

Caviston, J. P., Longtine, M., Pringle, J. R., and Bi, E. (2003). The role of Cdc42p GTPase-activating proteins in assembly of the septin ring in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4051–4066. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0247

Clay, L., Caudron, F., Denoth-Lippuner, A., Boettcher, B., Buvelot Frei, S., Snapp, E. L., et al. (2014). A sphingolipid-dependent diffusion barrier confines ER stress to the yeast mother cell. Elife 3:e01883. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01883

Copic, A., Dorrington, M., Pagant, S., Barry, J., Lee, M. C., Singh, I., et al. (2009). Genomewide analysis reveals novel pathways affecting endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis, protein modification and quality control. Genetics 182, 757–769. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.101105

DeMay, B. S., Bai, X., Howard, L., Occhipinti, P., Meseroll, R. A., Spiliotis, E. T., et al. (2011). Septin filaments exhibit a dynamic, paired organization that is conserved from yeast to mammals. J. Cell Biol. 193, 1065–1081. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012143

De Virgilio, C., DeMarini, D. J., and Pringle, J. R. (1996). SPR28, a sixth member of the septin gene family in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that is expressed specifically in sporulating cells. Microbiology 142(Pt 10), 2897–2905. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2897

Dobbelaere, J., Gentry, M. S., Hallberg, R. L., and Barral, Y. (2003). Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of septin dynamics during the cell cycle. Dev. Cell. 4, 345–357. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00061-3

Egelhofer, T. A., Villén, J., McCusker, D., Gygi, S. P., and Kellogg, D. R. (2008). The septins function in G1 pathways that influence the pattern of cell growth in budding yeast. PLoS ONE 3:e2022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002022

Fang, X., Luo, J., Nishihama, R., Wloka, C., Dravis, C., Travaglia, M., et al. (2010). Biphasic targeting and cleavage furrow ingression directed by the tail of a myosin II. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1333–1350. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201005134

Finnigan, G. C., Booth, E. A., Duvalyan, A., Liao, E. N., and Thorner, J. (2015). The Carboxy-Terminal Tails of Septins Cdc11 and Shs1 Recruit Myosin-II Binding Factor Bni5 to the Bud Neck in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 200, 821–840. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176495

Finnigan, G. C., Sterling, S. M., Duvalyan, A., Liao, E. N., Sargsyan, A., Garcia, G., et al. (2016). Coordinate action of distinct sequence elements localizes checkpoint kinase Hsl1 to the septin collar at the bud neck in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 27, 2213–2233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e16-03-0177

Garcia, G. III. Bertin, A., Li, Z., Song, Y., McMurray, M. A., Thorner, J., et al. (2011). Subunit-dependent modulation of septin assembly: budding yeast septin Shs1 promotes ring and gauze formation. J. Cell Biol. 195, 993–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201107123

Garcia, G. III. Finnigan, G. C., Heasley, L. R., Sterling, S. M., Aggarwal, A., Pearson, C.G., et al. (2016). Assembly, molecular organization, and membrane-binding properties of development-specific septins. J. Cell Biol. 212, 515–529. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511029

Gladfelter, A. S., Bose, I., Zyla, T. R., Bardes, E. S., and Lew, D. J. (2002). Septin ring assembly involves cycles of GTP loading and hydrolysis by Cdc42p. J. Cell Biol. 156, 315–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109062

Hartwell, L. H. (1971). Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. IV. Genes controlling bud emergence and cytokinesis. Exp. Cell Res. 69, 265–276. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90420-7

Hernández-Rodríguez, Y., and Momany, M. (2012). Posttranslational modifications and assembly of septin heteropolymers and higher-order structrues. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.09.007

Iwase, M., Luo, J., Nagaraj, S., Longtine, M., Kim, H. B., Haarer, B. K., et al. (2006). Role of a Cdc42p effector pathway in recruitment of the yeast septins to the presumptive bud site. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1110–1125. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0793

Johnson, E. S., and Blobel, G. (1999). Cell cycle-regulated attachment of the ubiquitin-related protein SUMO to the yeast septins. J. Cell Biol. 147, 981–994. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.981

Kadota, J., Yamamoto, T., Yoshiuchi, S., Bi, E., and Tanaka, K. (2004). Septin ring assembly requires concerted action of polarisome components, a PAK kinase Cla4p, and the actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5329–5345. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0254

Kang, H., Tsygankov, D., and Lew, D. J. (2016). Sensing a bud in the yeast morphogenesis checkpoint: a role for Elm1. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 1764–1775. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0014

Kang, P. J., Hood-DeGrenier, J. K., and Park, H. O. (2013). Coupling of septins to the axial landmark by Bud4 in budding yeast. J. Cell Sci. 126, 1218–1226. doi: 10.1242/jcs.118521

Kaplan, C., Jing, B., Winterflood, C. M., Bridges, A. A., Occhipinti, P., Schmied, J., et al. (2015). Absolute arrangement of subunits in cytoskeletal septin filaments in cells measured by fluorescence microscopy. Nano Lett. 15, 3859–3864. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00693

Kozubowski, L., Larson, J. R., and Tatchell, K. (2005). Role of the septin ring in the asymmetric localization of proteins at the mother-bud neck in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3455–3466. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0764

Leipe, D. D., Wolf, Y. I., Koonin, E. V., and Aravind, L. (2002). Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 41–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378

Longtine, M. S., Fares, H., and Pringle, J. R. (1998). Role of the yeast Gin4p protein kinase in septin assembly and the relationship between septin assembly and septin function. J. Cell Biol. 143, 719–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.719

Luedeke, C., Frei, S. B., Sbalzarini, I., Schwarz, H., Spang, A., and Barral, Y. (2005). Septin-dependent compartmentalization of the endoplasmic reticulum during yeast polarized growth. J. Cell Biol. 169, 897–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412143

Manzano-Lopez, J., Perez-Linero, A. M., Aguilera-Romero, A., Martin, M. E., Okano, T., Silva, D. V., et al. (2015). COPII coat composition is actively regulated by luminal cargo maturation. Curr. Biol. 25, 152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.039

McMurray, M. A., and Thorner, J. (2008). Septin stability and recycling during dynamic structural transitions in cell division and development. Curr. Biol. 18, 1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.020

Merlini, L., Bolognesi, A., Juanes, M. A., Vandermoere, F., Courtellemont, T., Pascolutti, R., et al. (2015). Rho1- and Pkc1-dependent phosphorylation of the F-BAR protein Syp1 contributes to septin ring assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 3245–3262. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-06-0366

Mino, A., Tanaka, K., Kamei, T., Umikawa, M., Fujiwara, T., and Takai, Y. (1998). Shs1p: a novel member of septin that interacts with spa2p, involved in polarized growth in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 732–736. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9541

Mitchell, L., Lau, A., Lambert, J. P., Zhou, H., Fong, Y., Couture, J. F., et al. (2011). Regulation of septin dynamics by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae lysine acetyltransferase NuA4. PLoS ONE 6:e25336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025336

Mortensen, E. M., McDonald, H., Yates, J. III., and Kellogg, D. R. (2002). Cell cycle-dependent assembly of a Gin4-septin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2091–2105. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0500

Oh, Y., and Bi, E. (2011). Septin structure and function in yeast and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.006

Okada, S., Leda, M., Hanna, J., Savage, N. S., Bi, E., and Goryachev, A. B. (2013). Daughter cell identity emerges from the interplay of Cdc42, septins, and exocytosis. Dev. Cell. 26, 148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.015

Okuzaki, D., and Nojima, H. (2001). Kcc4 associates with septin proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 489, 197–201. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02104-4

Ong, K., Wloka, C., Okada, S., Svitkina, T., and Bi, E. (2014). Architecture and dynamic remodelling of the septin cytoskeleton during the cell cycle. Nat. Commun. 5, 5698. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6698

Orlando, K., Sun, X., Zhang, J., Lu, T., Yokomizo, L., Wang, P., et al. (2011). Exo-endocytic trafficking and the septin-based diffusion barrier are required for the maintenance of Cdc42p polarization during budding yeast asymmetric growth. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 624–633. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0484

Ozsarac, N., Bhattacharyya, M., Dawes, I. W., and Clancy, M. J. (1995). The SPR3 gene encodes a sporulation-specific homologue of the yeast CDC3/10/11/12 family of bud neck microfilaments and is regulated by ABFI. Gene 164, 157–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00438-C

Pringle, J. R. (2008). “Origins and development of the septin field,” in The Septins, eds P. A. Hall, S. E. H. Russell, and J. R. Pringle (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 7–34.

Ptacek, J., Devgan, G., Michaud, G., Zhu, H., Zhu, X., Fasolo, J., et al. (2005). Global analysis of protein phosphorylation in yeast. Nature 438, 679–684. doi: 10.1038/nature04187

Qiu, W., Neo, S. P., Yu, X., and Cai, M. (2008). A novel septin-associated protein, Syp1p, is required for normal cell cycle-dependent septin cytoskeleton dynamics in yeast. Genetics 180, 1445–1457. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091900

Renz, C., Johnsson, N., and Gronemeyer, T. (2013). An efficient protocol for the purification and labeling of entire yeast septin rods from E.coli for quantitative in vitro experimentation. BMC Biotechnol. 13:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-60

Renz, C., Oeljeklaus, S., Grinhagens, S., Warscheid, B., Johnsson, N., and Gronemeyer, T. (2016). Identification of cell cycle dependent interaction partners of the septins by quantitative mass spectrometry. PLoS ONE 11:e0148340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148340

Sanders, S. L., and Field, C. M. (1994). Cell division: septins in common? Curr. Biol. 4, 907–910. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00201-3

Schneider, C., Grois, J., Renz, C., Gronemeyer, T., and Johnsson, N. (2013). Septin rings act as a template for myosin higher-order structures and inhibit redundant polarity establishment. J. Cell Sci. 126, 3390–3400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.125302

Schweins, T., and Wittinghofer, A. (1994). GTP-binding proteins. Structures, interactions and relationships. Curr. Biol. 4, 547–550. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00122-6

Shcheprova, Z., Baldi, S., Frei, S. B., Gonnet, G., and Barral, Y. (2008). A mechanism for asymmetric segregation of age during yeast budding. Nature 454, 728–734. doi: 10.1038/nature07212

Sirajuddin, M., Farkasovsky, M., Hauer, F., Kühlmann, D., Macara, I. G., Weyand, M., et al. (2007). Structural insight into filament formation by mammalian septins. Nature 449, 311–315. doi: 10.1038/nature06052

Sirajuddin, M., Farkasovsky, M., Zent, E., and Wittinghofer, A. (2009). GTP-induced conformational changes in septins and implications for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16592–16597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902858106

Skruzny, M., Desfosses, A., Prinz, S., Dodonova, S. O., Gieras, A., Uetrecht, C., et al. (2015). An organized co-assembly of clathrin adaptors is essential for endocytosis. Dev. Cell. 33, 150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.023

Smaczynska-de Rooij, I. I., Allwood, E. G., Aghamohammadzadeh, S., Hettema, E. H., Goldberg, M. W., and Ayscough, K. R. (2010). A role for the dynamin-like protein Vps1 during endocytosis in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 123, 3496–3506. doi: 10.1242/jcs.070508

Smaczynska-de Rooij, I. I., Marklew, C. J., Allwood, E. G., Palmer, S. E., Booth, W. I., Mishra, R., et al. (2015). Phosphorylation regulates the endocytic function of the yeast dynamin-related protein Vps1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36, 742–755. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00833-15

Tang, C. S., and Reed, S. I. (2002). Phosphorylation of the septin cdc3 in g1 by the cdc28 kinase is essential for efficient septin ring disassembly. Cell Cycle 1, 42–49. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.1.99

Versele, M., and Thorner, J. (2004). Septin collar formation in budding yeast requires GTP binding and direct phosphorylation by the PAK, Cla4. J. Cell Biol. 164, 701–715. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312070

Vrabioiu, A. M., and Mitchison, T. J. (2006). Structural insights into yeast septin organization from polarized fluorescence microscopy. Nature 443, 466–469. doi: 10.1038/nature05109

Wloka, C., and Bi, E. (2012). Mechanisms of cytokinesis in budding yeast. Cytoskeleton 69, 710–726. doi: 10.1002/cm.21046

Yuan, S. M., Nie, W. C., He, F., Jia, Z. W., and Gao, X. D. (2016). Kin2, the Budding Yeast Ortholog of Animal MARK/PAR-1 Kinases, Localizes to the Sites of Polarized Growth and May Regulate Septin Organization and the Cell Wall. PLoS ONE 11:e0153992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153992

Keywords: septins, budding yeast, GTPase, crystal structure, cytokinesis

Citation: Glomb O and Gronemeyer T (2016) Septin Organization and Functions in Budding Yeast. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4:123. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00123

Received: 31 August 2016; Accepted: 19 October 2016;

Published: 03 November 2016.

Edited by:

Manoj B. Menon, Hannover Medical School, GermanyReviewed by:

Ravi Manjithaya, Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, IndiaMarkus Proft, Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia (CSIC), Spain

Copyright © 2016 Glomb and Gronemeyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thomas Gronemeyer, dGhvbWFzLmdyb25lbWV5ZXJAdW5pLXVsbS5kZQ==

Oliver Glomb

Oliver Glomb Thomas Gronemeyer

Thomas Gronemeyer