95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. , 21 May 2024

Sec. Diabetes Inequalities

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcdhc.2024.1306199

This article is part of the Research Topic Ethnic Inequalities in Diabetes Care and Outcomes View all 5 articles

Objective: Ethnic minority groups in high income countries in North America, Europe, and elsewhere are disproportionately affected by T2DM with a higher risk of mortality and morbidity. The use of community health workers and peer supporters offer a way of ensuring the benefits of self-management support observed in the general population are shared by those in minoritized communities.

Materials and methods: The major databases were searched for existing qualitative evidence of participants’ experiences and perspectives of self-management support for type 2 diabetes delivered by community health workers and peer supporters (CHWPs) in ethnically minoritized populations. The data were analysed using Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability.

Results: The results are described within five domains of the framework of acceptability collapsed from seven for reasons of clarity and concision: Affective attitude described participants’ satisfaction with CHWPs delivering the intervention including the open, trusting relationships that developed in contrast to those with clinical providers. In considering Burden and Opportunity Costs, participants reflected on the impact of health, transport, and the responsibilities of work and childcare on their attendance, alongside a lack of resources necessary to maintain healthy diets and active lifestyles. In relation to Cultural Sensitivity participants appreciated the greater understanding of the specific cultural needs and challenges exhibited by CHWPs. The evidence related to Intervention Coherence indicated that participants responded positively to the practical and applied content, the range of teaching materials, and interactive practical sessions. Finally, in examining the impact of Effectiveness and Self-efficacy participants described how they changed a range of health-related behaviours, had more confidence in dealing with their condition and interacting with senior clinicians and benefitted from the social support of fellow participants and CHWPs.

Conclusion: Many of the same barriers around attendance and engagement with usual self-management support interventions delivered to general populations were observed, including lack of time and resource. However, the insight of CHWPs, their culturally-sensitive and specific strategies for self-management and their development of trusting relationships presented considerable advantages.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prominent global health challenge impacting 536.6 million adults worldwide (1). Ethnic minority groups in high income countries in North America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand are disproportionately affected by T2DM and also have a higher risk of mortality and morbidity (2–7). Supported self-management that helps control blood sugar levels and sustain positive health and lifestyle behaviours is an internationally recognised method of improving the prognosis for those with T2DM (8, 9). However, in developed countries, the benefits of self-management are not realised in minoritized communities more vulnerable to the cultural and social barriers which impact engagement with diabetes care more broadly, and specifically with self-management support (10, 11). These barriers include health literacy, cultural stigma, a lack of personal resource, the severity of the condition, and broader factors involving the healthcare system and the interaction with care providers (10, 12–15) (as summarised in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Factors affecting access and engagement with (diabetes) self-management programmes (15).

With the increasing prevalence of T2DM in minoritized communities, it is important to identify and understand which components of self-management interventions might be best placed to address these barriers (15, 16). One approach that has shown promise in T2DM, and other long-term conditions, is the use of individuals linguistically, experientially and ethnically indigenous to target communities in the delivery of diabetes self-management advice and education (DSME) and other aspects of self-management support (4, 17–22). These individuals have been employed in a range of roles with various names including community health workers, lay health workers, peer educators, and peer mentors, and receive varying levels of training (17–19, 23, 24). For the purposes of this review, we use the collective term community health worker and peer supporter or educator (CHWP) defined as: “non-professional workers who are from or understand local communities, and deliver structured community-based support or education for diabetes self-management having received intervention-specific training” (25).

Despite inconsistent empirical evidence of CHWPs’ direct effect on diabetes outcomes, early indications are that CHWPs offer a promising means of improving HbA1c control (21, 26) as well as psycho-social benefits of increased self-efficacy and acceptance (27). However, if this impact is to be optimised in minoritized populations, it is important to understand participant views on CHWPs and use these to inform future iterations (28–32).

This qualitative systematic review collates and analyses qualitative evidence from participants in diabetes self-management interventions for ethnic minorities delivered by CHWPs. To structure our findings and analysis we used Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) which was developed to explore acceptability of health care interventions from the perspectives of providers and patients (33). We described participant experiences and perspectives of care interventions within its domains including the burden of participation, intervention coherence, and perceived effectiveness (33). This has allowed us to identify several key factors influencing the success of CHWP-led interventions in minoritized communities and enabled the creation of a series of recommendations for future implementation.

A systematic review of qualitative data describing participant experiences of CHWP-led T2DM self-management interventions in minoritized populations. Eligibility criteria and search terms were developed using the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Data, Evaluation, Research Type) tool which is tailored specifically to the screening of qualitative research (34) (see Supplementary File 1). The findings are presented within an adapted version of Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (33).

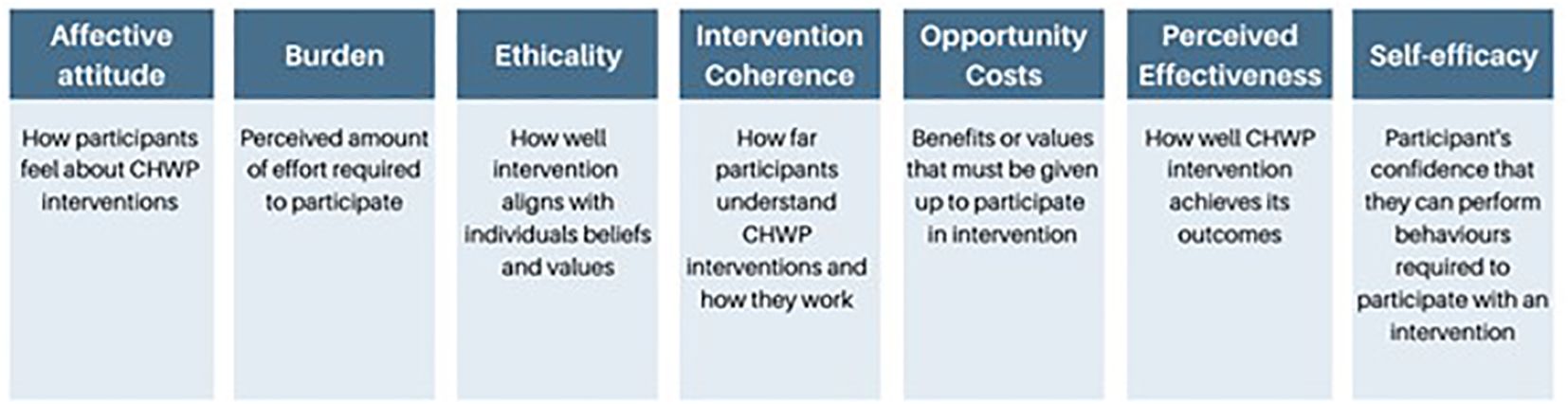

The TFA was developed by Sekhon et al. firstly by producing an overview of reviews that defined, theorised or measured the acceptability of healthcare interventions (33). This was then used to develop the theoretical framework by defining acceptability, describing its properties and scope, and then identifying component constructs and empirical indicators (33). The final TFA consisted of seven domains: affective attitude, burden, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy (see Figure 2). Together they describe whether those receiving (or delivering) an intervention consider it to be appropriate based on anticipated or experiential cognitive and emotional responses (33). It has been successfully used in a range of settings and circumstances including the treatment of HIV (35), breast cancer (36) and mental health (37). The seven domains and their constructs were used to guide the presentation and analysis of our qualitative findings to understand the acceptability of CHWP interventions in ethnic minority groups.

Figure 2 Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) and Definitions (33).

The following five electronic databases were searched in August 2023: MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL via EBSCO), PsycInfo and Web of Science. Google Scholar and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global were also searched to identify grey literature. The search strategy (See Supplementary File 2), including all index terms and identified keywords, was adapted for each specified database. Reference lists of eligible papers were hand searched for additional citations. No date limits were applied as CHWP involvement in diabetes management first appeared in the literature in the 1980s (38). The geographical range of the included studies was restricted to Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Western Europe and the USA as they constitute developed health economies (all be it with different models of healthcare provision) and are resident to sizeable ethnic minority communities i.e. all ethnic groups whose members typically share a combination of characteristics of culture, religion or language, except the white group of western European origin (39, 40).

Search results were exported and indexed in EndNote 20 (41). After removing duplicates, studies were screened using Covidence software, a web-based system for managing systematic reviews (42). Studies which met the following criteria were included: (1) Conducted in a high-income western country [as defined by the world bank (43)]; (2) Explored participants’ perspectives using qualitative methods; (3) Interventions (including programmes or elements of programmes) led by CHWPs related to self-management or prevention of T2DM; (4) Ethnic minority adults represented the majority of the cohort explored; and (6) Full-text versions were available in English. Studies were excluded: if (1) the role of the CHWP could not be clearly identified or (2) were aimed at those with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or gestational diabetes.

Two independent reviewers including the 1st author carried out title and abstract screening using the above eligibility criteria. Both reviewers received training in qualitative research methods and systematic review screening as part of their intercalated training. Any disagreements were firstly discussed between the reviewers (i.e. VG and FJ) and escalated to IL for a final decision if they could not be resolved. The two reviewers screened full-text versions of studies and excluded papers which did not fulfil inclusion criteria: IL had oversight of the selection process and all papers included in the review were consensually agreed by both authors.

Data were first extracted on general study characteristics and key intervention components. Study data were imported into NVivo 1.0 software for analysis (44). Where studies employed mixed methods, only qualitative data were extracted. The data included in the analysis consisted of verbatim quotes from participants of individual studies and authors’ interpretations of findings.

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist was used by two independent reviewers to appraise the limitations and strengths of each study’s methodological reporting (Supplementary File 3) (45). No articles were excluded based on reporting quality as all studies enhanced the conceptual richness of the final synthesis. In mixed method studies, only qualitative aspects were appraised.

A framework-based approach was used combining both deductive and inductive analyses to populate the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) (33, 46). Analysis consisted of two main stages: First Deductive Coding was applied which involved familiarisation with the data set and allocating the data into the most appropriate TFA domains. Second, we used an iterative process of Inductive Coding whereby similar codes within each domain were grouped leading to the final set of domains and constructs.

A total of 17 studies were included in the systematic review. The PRSIMA diagram describing study selection is shown in Figure 3 (47). In total the views and perceptions of 387 participants were described, with 15 studies conducted in the USA, one in Canada and another in Australia; of these seven focussed on Latino populations (48–54); five African American (55–59); one mixed of both populations (60), one Native American (61), one Punjabi (62); one Aboriginal (63); and one on Pacific Islanders (64). Papers were published between 2009 and 2022. All studies focused on participant perspectives post-intervention and thus assessed retrospective acceptability. Key study characteristics and specific intervention components are summarised in Table 1.

The TFA as developed by Sekhon et al. has been refined to bring greater clarity and concision: the domain ‘Ethicality’ has been renamed ‘Cultural sensitivity’; a phrase more precisely describing the domain and its constructs as represented in this review. Due to overlaps in the findings, ‘Burden’ and ‘Opportunity Costs’ were grouped to form one domain as were the related domains of ‘Intervention Effectiveness’ and ‘Self-efficacy’ resulting in five final domains and a total of 14 constructs. Table 2 presents definitions of the main domains and emergent constructs.

Below we explore the findings within each domain and construct, using exemplar participant quotes (shown in italics). Participant characteristics, where available, are provided to contextualise their views. (Male and female Latino and Hispanic participants are referred to hereon as “Latino(s) or Latina(s)”).

Participants described their overall appreciation for the involvement of CHWPs in terms of their communication style and the way in which they made participants feel at ease (48–53, 55, 60–65). As one African American participant described:

“My experience was really good. I mean, everybody made me comfortable … as far as the way they explained things, especially in the meetings … it was easy to follow along.” [African American Participant] (58)

In another example, a participant described how the CHWP recapped the basics of healthy eating without judgement after a participant was witnessed snacking unhealthily:

“When I first started with Ms. … I was sneaking eating and she would know it. One time she caught me. She did not get all aggressive or ugly like that. She just broke it down to me and brought it down to how important my health was and got me back on the right track.” [African American participant] (56)

Despite the generally positive response towards CHWPs, participants across several studies were dissatisfied with CHWPs’ clinical knowledge, and inability to answer more detailed questions (51, 60, 62, 64, 65). As one participant described:

“I think … some things that maybe they couldn’t really give you the answer to, I think they should know a little more … I think we asked her something one time and I can’t remember what it was but she couldn’t really answer either.” (60)

Related to this, CHWP training varied from a brief induction delivered by research staff (58) to an in-depth training programme with regular updates delivered by local health care providers (61). In studies the training regime was often poorly described or inconsistent making it difficult to evaluate the resulting impact on intervention quality (49, 52, 55, 56, 60, 63).

Participants in four studies described the trusting relationship they developed with CHWPs and their ability to engage in open discussions about their success and failures following CHWP guidance (59–61, 66). As one African American participant explained:

“With him [CHWP], I could keep it real. I could tell him I didn’t do this or that.” [African American, Male] (59)

This was contrasted with feelings of being judged by clinicians. As a Latino participant in the USA described:

“The doctor sees my blood tests and he tells me it’s bad and that I’m not doing well. That makes me feel worse. She [promo-tora] doesn’t judge us.” [Latino participant] (50)

This apparently unconditional support contributed to some participants describing their relationship with CHWPs as akin to that of a senior family member (50, 61). As one participant in a study conducted amongst the Navajo population in the USA, described:

“I can tell her anything about my personal life … [she] is like my grandma and [she] is like a cousin sister to me.” [Navajo, male] (61)

The trusting, respectful nature of this relationship led to CHWPs exerting greater levels of influence. As exemplified in the comments of a Latino participant in a study in California:

“About two weeks went by and I still didn’t feel like making changes. I kept wanting to eat the same things, but the encouragement that the [promotora] gave me … That was a source of motivation.” [Latino participant] (51)

In relation to the importance of shared characteristics, participants in three studies described the significance of the CHWP having diabetes (50, 60, 65). Latino and African American participants in two studies felt that CHWPs who did not have diabetes could not fully understand their feelings as they lacked experiences of the challenges presented by T2DM (50, 65).

Participants in four studies, which included Native American, African American, and Latino populations, described their negative perceptions of health care professionals (HCPs) (54, 60, 61, 67). In one study set in Latino communities, doctors were perceived as lacking “personalismo”; the belief within Latino culture of being able to personally relate to others regardless of social or economic standing (67). As one participant explained:

“There is no such thing as ‘personalismo’ anymore. Doctor’s take so little time with us…” [Latino participant] (54)

There was also a lack of trust in the judgement of clinicians, for example one Native American participant raised concerns on the over medicalisation of diabetes:

“What if you’re at the normal level again and doctor just keeps telling you, take it, take it?” [Navajo, male] (61).

There were also concerns that clinical staff were formerly connected or answerable to central government organisations and authorities. One Latina participant in a study set in Detroit, USA described how she felt threatened by doctors as she believed that professional workers would send her to the police or the Immigration and Naturalization Service (60).

Despite the reservations that some held, two interventions where CHWPs worked alongside other health (and social) care providers were well-received by participants (51, 53). In the study set in the Latino population, one participant described how they were motivated to adhere to the intervention by the additional gravitas of a clinical opinion:

“My physician explained to me that I needed to take the program very seriously since I had a high A1c level, that’s when I took it seriously.” [Latina participant] (51)

The physical and mental health of participants related to T2DM severity affected ability to attend sessions in two studies set in Latino populations (49, 51). As one participant from a Latino population in Connecticut, USA explained:

“Sometimes I’m not feeling well, sometimes I feel lightheaded or have a headache related to my diabetes, so I have to cancel my session…’’ [Latino participant] (49)

In this instance, participants favoured programme adaptations which facilitated remote access and therefore minimised the impact of ill health on the ability to travel. As one participant explained:

“I would prefer to meet with the CHW more often at my place, [because of] my health conditions It’s sometimes difficult for us to meet in person at the clinic.” [Latino participant] (49)

A number of participants described the difficulties in attending classes due to a range of personal obligations and responsibilities. This included a lack of childcare or childminding facilities (63) and work commitments (49, 58). In particular, the scheduling of sessions immediately after office hours impacted attendance. As one African American participant explained:

“… I get off work at 5:00…I work on the phones, and I’m quiet for hours afterwards. I just don’t want to hear myself talk.” [African American participant] (58)

Participants described a number of logistical barriers that inhibited sustained engagement with the intervention specifically relating to transport issues, expense, and local amenities (49, 51). In Latino communities in Connecticut, USA, one participant described impact on their engagement with the intervention due to difficulties in reaching the venue of the intervention:

“My weight is still fiuctuating, sometimes I lose weight, then I gain it back because it’s hard for me to get to the YMCA.’’ [Latina participant] (49)

Latino participants in California, USA described their frustration at the costs associated with healthy eating and purchasing the fresh food recommended (51).

“Sometimes the reality is that organic and healthy food are expensive.” [Latina participant] (51)

Participants in the same intervention received advice from CHWPs that walking was a simple but effective way of increasing physical activity (51). However, the high levels of violent crime in the local neighbourhood limited opportunities for outdoor exercise:

“One goes to the park to exercise and … things happen … well, one gets assaulted. Then it’s scary.” [Latina participant] (51)

The impact of pre-existing cultural mores on engagement with the intervention were described in Latino populations in two studies based in the USA (51, 54). Female participants reported difficulties in changing their diet due to resistance from their partners and children as refusing to cook traditional dishes was considered culturally disrespectful (51, 54). This could lead to family conflict and drove some Latina participants to abandon the programme (51). The cultural concept of ‘machismo’ holds that men are tough and possess a superior position as head and breadwinner of the family (68). This led to marital conflict where some husbands objected to their wives attending classes:

“This was about to cost me a divorce. Because I would go to classes and my husband didn’t like it.” [Latina participant] (51)

It also meant that men faced pressure to maintain a strong image. For example, in a study based in Texas, USA, men described their reluctance to share personal challenges with CHWPs in group sessions:

“I keep my mouth shut; it is not macho [manly] to tell someone that you are weak. Mexican-American men just don’t feel comfortable sharing their weakness in public.” [Latino participant] (54)

CHWPs shared or understood the cultural characteristics of participants which helped contextualise their advice and guidance (50–54, 60–62, 64). For example, they were able to describe how familiar foods could be used in controlling blood sugar (54, 62). As one Latina participant from a study set in Texas, USA described:

“Just knowing how I can eat a little bit of menudo [traditional Mexican soup], makes me feel less restricted. I always test afterwards now to see how me and the menudo did.” [Latina participant] (54)

Participants also appreciated CHWPs’ awareness of hospitality customs which present additional dietary temptations and social pressure, from well-meaning hosts (54, 62). CHWPs gave individuals the confidence to politely decline some of the foods offered, as one Punjabi participant explained:

“I learned to say no at social gatherings i.e., no samosas!” [Punjabi participant] (62)

It is widely understood that bilingual services can further increase the cultural applicability of self-management interventions (69) and the ability of CHWPs to speak the same language as participants was not only appreciated by participants but in was some instances a necessity (50, 62). As one Latino participant in Pennsylvania, USA described:

“Some of us don’t speak English, so it is important to have the classes in Spanish.” [Latino participant] (50)

Educational materials should also be translated into the native language of participants as partial translation can create a barrier for monolingual participants (62). One Punjabi participant noted this barrier when some intervention components were only available in English:

“Please put all information about Leader’s Manual on website and next workshop dates information in Punjabi.” [Punjabi participant] (62)

Participants described how they had an increased understanding of the link between activity, diet and blood glucose control due to practical and applied examples used by CHWPs (48, 50–53, 57–63, 65). As one Hispanic participant from a study set in Washington, USA explained:

“I was always scared about how, if I eat this food, ah, my sugar would go way up and stuff. But [the promotora] taught me that you can eat that food, just not a lot of it.” [Hispanic participant] (52)

The content of the interventions included advice on physical activity, cooking guidance, and elements of clinical management (49, 52, 57, 58, 61–64).

A range of teaching materials were employed including Loteria (teaching cards) (51); self-completed workbooks (54); visual props (61, 63) including photovoice, a process that uses participant-taken photos to encourage reflection on community needs and concerns (55). As one Native American participant described:

“She brought pictures and I understood from those pictures, including the flipcharts.” [Navajo, Female] (61)

Two different interventions incorporated practical cooking sessions (57, 63), and one of these also included an exercise circuit (63). The practical application of this information was helped by the distribution of supportive materials for healthy eating such as cookbooks (52), measuring cups, and portioning plates (61). To encourage physical exercise, pedometers (52) and exercise bands (61, 64) were supplied, and to support clinical management of T2DM dosette boxes (64) and glucose monitors (52) were provided.

CHWP-led interventions utilised group sessions (48, 50–52, 60, 62, 64); one-to-one sessions (61, 70); or a combination of both (57, 58). Participants in four studies favoured group sessions as it allowed them to form friendships and expand their social network, particularly where support was unavailable at home (49, 50, 65, 66). As one Latina participant from Connecticut, USA explained:

“I live alone so sometimes I feel isolated. However, now that I’m in this program, I feel more connected.” [Latina participant] (49)

Participants also valued hearing others speak about their personal challenges with diabetes which served to reassure them that others faced similar obstacles. As one participant explained:

“You feel a little more comfortable with somebody that’s going through the same thing that you are going through.” [African American participant] (58)

Another participant described how their CHWP had actively facilitated and encouraged participants to connect and support one another as they undertook the intervention:

“The promotora kept us motivated by encouraging us to exchange phone numbers, telling us to call other classmates when we didn’t feel well, explaining how we felt; and that helped us to open up on many things.” [Latino participant] (51)

The structure of the various interventions frequently lacked detail on duration but in two studies participants expressed regret that they did not last longer (48, 49). Elsewhere, participants wanted more emphasis on follow-up between classes to consolidate learning and offer additional support (57, 62, 64). There was also a desire to retain access to CHWPs for advice following completion of the intervention. For example, one African American participant explained how this contact would help negotiate the Christmas holidays:

“December’s coming up … I do remember we talked about, you know, dealing with depression, holidays, meals, and things like that. I would like to get a brush up on that…” [African American participant] (58)

The majority of the interventions were conducted entirely face-to-face though three studies incorporated follow-up telephone calls in between taught sessions (53, 56, 65). As one participant explained:

“They always concerned about different things like your sugar, your HbA1C, are you keeping up with those type of issues and that helps because I never been in that space where people call me to see how I’m doing and am I doing the correct things and its pleasurable to get that kind of attention.” [African American participant] (56)

Participants in a number of studies reported improvements in a range of self-management behaviours as a result of the CHWP-led intervention (48, 50–53, 57, 59–63, 65): As one Latino participant described:

“I have a better understanding of how to test my blood sugar, how to manage my diabetes, navigate my different medical appointments, and also engage in more physical activity.” [Latino participant] (49)

Participants described how they effectively applied CHWP teaching to transform their diet (52, 61). As one Native American participant explained:

“I totally got away from sodas. I don’t drink sodas no more. Bread, I don’t eat no more. Just water, constantly, every day, I drink a lot of water. Junk food I don’t eat anymore.” … “Even when we eat out, my family, I just get a salad while they eat their burgers.” [Navajo, male] (61)

A Latino participant in a study set in Washington, USA described how the CHWP intervention helped change the eating behaviours of their entire family (52):

“We didn’t have a good habit and … they would eat at a certain time and the kids would be snacking at a certain time and, ah, well, now it’s like “No! We’re gonna get breakfast, lunch, and dinner and we’re gonna sit down - we’re gonna do this together!’ “ [Latina participant] (52)

Two different studies explored the introduction of exercise and physical activity into daily routines with participants reporting positive effects the interventions had on their routine levels of activity (61, 62). In a study set amongst the Punjabi community in Canada one participant described how they made a conscious choice to use the stairs instead of the elevator:

“I used to walk only with a walker but now am improving and am walking with a cane, I climb the stairs now for exercise and I’m getting stronger.” [Punjabi participant] (62)

Also related to increased activity, a Native American participant described how following the intervention they became more active, whether in the home or through outdoor exercises such as taking a walk:

“Instead of staying on the couch, do something around the house, she said. At least take a walk to the highway and come back or walk around the house.” [Navajo, female] (61)

Another participant in the same study described how they more regularly monitored blood glucose as encouraged by the CHWP which confirmed that their efforts were succeeding:

“I’ve been improving … I check my blood all the time and, uh, pretty good. Down to 98, 96.” [Navajo, male] (61)

Following programme completion, participants in a number of studies described how they felt empowered and better prepared when communicating with HCPs (48, 52, 53, 60, 62, 65). As one participant from Detroit, USA stated:

“Now I feel more comfortable talking with my doctor and asking all that I think that I need to know. I know more, so I can ask more. I’m not so afraid.” [African American participant] (60)

Another African American participant expressed similar feelings of increased confidence when interacting with clinicians and appreciated that they have a responsibility to help patients:

“…you do not have to be afraid. Just you are [in] there, that’s your doctor. It’s confidential. Whatever it is, whatever you feel, that’s what they are there for.” [African American participant] (65)

Participants in a number of studies described how the intervention helped them come to terms with their diagnosis and were therefore psychologically better equipped to live with diabetes (50, 51, 54, 60, 62). As one Latino participant explained:

“My lifestyle has changed a lot. I feel happy and relieved. Before, I felt bad. But now I have more self-esteem. Before, I thought that there was no solution. Now I know that I can live well and feel well.” [Latino participant] (50)

Our research provides a much-needed synthesis of primary qualitative studies exploring CHWP-led interventions designed to improve self-management of T2DM within ethnic minority groups. The TFA has proven a useful tool in exploring existing evidence with pertinent findings emerging within each of the five domains. Affective attitude described participants’ overall positive attitudes towards CHWP-led interventions. Participants responded favourably to CHWPs as their shared characteristics enabled a closer and more familial relationship in comparison to mainstream health care providers, though not without concerns over the depth of their clinical knowledge. In considering Burden and Opportunity Costs, participants reflected on the difficulties faced attending and completing the interventions. These included the impact of poor health, cost, and obligations of work and family. In relation to Cultural sensitivity, participants appreciated the enhanced understanding of their needs and challenges demonstrated by CHWPs including how they placed strategies for behavioural change in a culturally-relevant context. The evidence related to Intervention Coherence indicated that participants responded positively to the content of DMSE, the camaraderie and support with fellow participants developed during group sessions, and interventions involving telephone follow-up. Finally, in examining the impact on Effectiveness and Self-efficacy, participants described sustained changes to health behaviours and the increased confidence in managing their condition and interacting with senior clinicians. Below we discuss these findings in more detail and conclude with a series of recommendations based on the presented evidence to inform future CHWP-led interventions (28).

Participants responded positively to the delivery of self-management interventions by CHWPs (50–52, 54, 58, 60, 61), though in some studies participants highlighted concerns over the limitations of CHWPs’ clinical knowledge (60, 62). The structure of CHWP training varied in the studies identified but concerns over the level of clinical knowledge of CHWPs have emerged previously in a range of interventions. The lack of focus on CHWP training has been identified previously in other conditions (71) as well as in T2DM interventions (72, 73), resulting in a call for additional assistance or training (74).

It is understood that a trusting relationship between patient and HCPs encourages personalised care and improves overall patient experience (75–77). Establishing such trust is especially important in improving engagement for marginalised communities often wary of traditional healthcare organisations due to previous negative experiences such as language barriers, poor cultural competence and racial discrimination (78–81). Contrary to this suspicion of HCPs, the studies we identified described the close bond created between participants and CHWPs, crediting their shared socio-cultural background (49–52, 58–61). There is also increasing evidence that through their role as mediators and advocates, and an increased emotional understanding, CHWPs can help restore patient trust in the healthcare system (82–87).

A range of factors relating to personal circumstances including poor health, work, logistical barriers relating to travel, and the cost of fresh food impacted engagement with the intervention (48, 49, 51, 56, 63–65).

The issues identified around transport and work commitments are also widely recognised in the general population with T2DM (88–90). Although these problems are not specific to minority populations (91), in USA and Europe they are more prevalent in these groups due to the intertwined relationship between ethnicity and socio-economic status (92). Lower socio-economic status amongst minoritized populations is reflected in longer commutes, use of public transport and multiple low-paid employment, all of which impact ability to attend self-management interventions (92–94). The prohibitive cost of “healthy” eating also reflects existing evidence of the negative impact of food insecurity on controlling diabetes in minority populations (95–97). Solving these broader socio-economic determinants is difficult within the scope of a single intervention but there are indications that providing transport (98), food coupons (99), or “food is medicine” type initiatives where nutritional food is prescribed by HCPs (100) can help low-income families manage diabetes (101). There is also the potential of CHWPs to visit individual households or provide remote sessions as ways of encouraging engagement with self-management support (102) though these are subject to issues of connectivity and digital literacy which can be limited in minoritized populations (103).

There are a range of culturally specific influences that can impact healthy behaviours in minoritized populations including gendered roles, religion, and custom (104). Implementing dietary changes for those with T2DM is challenged both in the USA and Europe by strong hospitality cultures, particularly during traditional religious celebrations or personal events (105–109). In this context, the culturally sympathetic dietary advice delivered by CHWPs familiar with traditional foods and social pressures was highly valued by participants (50, 52–54, 60, 62, 64).

It is also broadly understood that trends in health behaviours are closely tied with established cultural beliefs around family and gender (104). This appeared particularly pronounced amongst Latino participants in the studies we identified (51, 54). In Latino populations this is exacerbated by strongly gendered roles for men and women (68, 110–114). In Latino communities, delivering dietary interventions at a family-level has been identified as one strategy to overcome domestic resistance (115) and have proven successful in preventing T2DM (116), and promoting a range of improved self-management behaviours in Latino adults diagnosed with T2DM (117, 118).

The ability of CHWPs to deliver interventions in the native language of participants was key for some Latino, Navajo and Punjabi participants (50, 61, 62). This has been previously recognised as an important consideration in delivering self-management interventions in Latino (119) Black African and Caribbean (120), Asian (121) and a range of minority populations (122, 123). However, providing content in a familiar language does not itself overcome issues of health literacy which is typically more predominant in minoritized populations (124). Tailoring health information to individual levels of understanding is required in both minority and general populations (125) and there is evidence that comprehension can be improved by their co-production (126–128).

The applied content of the DSME delivered by CHWPs in the identified studies were credited by participants with effectively linking theory to practical self-management advice (48, 50–53, 57–63, 65). This included how to interpret food labels, and the relationship between blood sugar levels and nutrient intake (57, 63, 64) (49, 52, 58, 61, 62). This reflects previous evidence that the content of CHWP-led T2DM interventions in the general population, particularly where they combine multiple teaching strategies, are considered more practical than traditional hospital consultations (129–137).

A mixture of teaching materials were used to mitigate differences in health literacy including: visual aids such as photovoice (55) previously recognised as an effective tool in conveying needs of individuals and their communities (138, 139), ‘loteria cards’ (51), and workbooks (54) which have also proved successful in DSME for Black women with T2DM (140). There is also evidence from previous DSME programmes that including practical sessions such as interactive cooking classes can help those with diabetes better manage HbA1c (141–143).

Non-judgemental support provided by either class peers or CHWPs, in particular where CHWPs also had diabetes, was well received (48, 49, 51, 58, 59, 62). CHWPs’ follow-up telephone calls between sessions were welcomed and regular provider contact has previously been associated with increased engagement with self-management regimes in general populations (144).

First-hand accounts of the challenges and consequences of (uncontrolled) T2DM whether from peers or CHWPs resonated with participants (51). This echoes previous work that described the motivation provided by improved awareness of serious diabetes related complications within the general population (145). The importance of the peer support from fellow participants was also highlighted and again these benefits have been observed in minoritized populations with T2DM (15, 146, 147) as well as in the general population (148).

Participants described improvement in a number of self-management behaviours including increased physical activity and healthier dietary habits, demonstrated in several studies by improved HbA1c control (48, 50–53, 57, 59–63, 65). CHWP-led interventions have proven similarly effective in the general population (73) with growing evidence of significantly improved blood glucose control (149, 150).

Individuals from all populations require a high level of self-efficacy to successfully manage the complex demands of T2DM self-management (151, 152). Participants in a number of identified studies reported greater confidence regarding independently managing diabetes and notably in their interactions with HCPs, where they were encouraged to be more active in discussions with clinicians. For example, questioning whether they had access to the necessary diabetes services and tests and querying any treatment changes (50, 58, 60, 62). Effective coaching on communication with HCPs is an increasingly important element of DSME programmes aimed at the whole population (153) but especially in minority groups where there are long-standing issues of patient passivity and miscommunication (154).

This comprehensive review provides valuable insight on minority perspectives of CHWP-led interventions and shared perspectives within the general population (10, 12–14). They also highlight that utilising CHWPs might mitigate some of the issues around language and culture but these interventions are still vulnerable to broader socio-economic issues that can impact attendance, and sustained engagement (13, 155). The TFA proved a useful means of organising the data and its comprehensive structure added to the reviews methodological rigour which used best practice throughout (34, 47, 156). However, the overall quality of the studies was low, their design heterogenous and the specifics of the intervention were often poorly described (49, 52, 55, 56, 60, 63). One element shared by all studies was that they assessed participant experience retrospectively introducing the possibility of recall bias (157). As with other reviews, it is also vulnerable to the biases introduced by the authors of the original studies (158) and we discovered a lack of overall study quality which has been reported in similar reviews of CHWP-led interventions (159).

Although the majority of studies are USA-based, and conducted in Latino and African American populations the work also includes valuable yet underrepresented perspectives of Native Americans, Punjabis and Aboriginal people (160, 161). However, caution should be applied when considering these findings in relation to other ethnicities and minoritized populations should not be considered a homogenous group and individualised co-designed approaches would ideally be pursued.

The majority of the CHWPs studied were female and though this is reflective of the CHWP workforce (with recent estimates suggesting 70% are female) (162), there may be gender specific responses related to male CHWPs that require further enquiry. A large number of studies were excluded because the CHWP element was part of a larger, multi-component self-management support programme. Future work might more closely observe the impact of the CHWP-element of any broader programme including exploration of the CHWP’s perspective.

Despite the clear potential of CHWP-led interventions to address some of the persistent challenges faced in improving T2DM self-management both in general and minoritized communities, there is still the opportunity for improvement in design and delivery. This includes exploring the experiences of lower- and middle-income countries in their utilisation of CHWPs. Below we draw out some practicable recommendations that might be applied when introducing CHWP-led interventions, presenting each within the domains of the TFA. These considerations alongside the broader findings of our review have been used to inform a series of questions for those commissioning and implementing CHWP-led interventions in ethnic minorities (see Supplementary File 3). Future programmes and research might draw on these, to improve practice and expand the non-professional health workforce.

Training and coordinating CHWPs for these roles is crucial and requires further research (73). There is opportunity to link CHWPs more closely with multidisciplinary teams who can provide ready access to more specialised clinical expertise (163). There is existing evidence that suggests a need for more systematic and comprehensive CHWP training, whether delivering interventions to minorities (72) or the general population (73, 164, 165).

It has been acknowledged that CHWPs can act as cultural mediators, liaison workers, navigators or advocates and their role covers various aspects of social support and health education (38). In identified studies CHWPs were employed in a number of varying roles however it is key that the precise roles of CHWP are understood and the expectations of participants and commissioners are established.

Many of the barriers associated with attendance and adherence to CHWP-led interventions in minorities are more broadly applicable across the general population (10, 12–14). To accommodate working adults and those with limited transport access or poor health, interventions should be available in a range of remote formats including online platforms and telephone coaching (166). There should also be a general focus on more readily accessible community venues with flexibility around timing (150, 167, 168). Issues of food security should be acknowledged by CHWPs in the content of the intervention and to help address this participants should be linked with support mechanisms through the local government or healthcare services (99–101).

Family-level interventions can potentially mitigate the influence of culturally-gendered roles and should therefore be considered in male-dominated cultures (117, 118). The CHWP workforce is also predominantly female hence it is vital to consider the recruitment of male CHWPs to support male participants that may otherwise feel inhibited by female leads (162, 169).

To help combat barriers of language and (health) literacy, CHWPs should ideally speak the same native language as participants and use educational materials written plainly and preferably co-designed with target populations (15, 170–174). In considering content, participants should be provided with practical information on how to marry cultural behaviours or practices with a healthy lifestyle (52, 61, 62, 175, 176).

The benefits of interacting with other culturally similar participants were described and more formally facilitated links between participants might be considered in future CHWP-led interventions (146, 177). Also important was coaching participants in how to effectively communicate with HCPs. This strategy has been successfully incorporated into a number of self-management interventions for T2DM and would ideally also be more universally applied to CHWP-led interventions (178).

This review has highlighted the key factors influencing how minoritized participants perceive CHWP-led interventions. Programmes were mostly positively received but points contributing to high attrition rates were raised. Many of the described barriers are contextual and also impact the general population undertaking T2DM self-management support interventions signalling a need for broader consideration at a health economics and policy level. However, barriers were often heightened in minoritized populations indicating that there are areas where the content or delivery of the intervention can be improved or more finely attuned to the socio-economic contexts of specific minoritized populations. Related to these we have specified a number of elements that warrant consideration for those commissioning or delivering these interventions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

VG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. IL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. IL is funded in part by NIHR grant Reference Number NIHR202358. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The authors thank Frédérique Janssen for her role as second reviewer which helped improve the validity and quality of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcdhc.2024.1306199/full#supplementary-material

1. Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes and Clinical Practice (2022) 183:1872–8227.

2. Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, Ramsay J, Eldridge S, Feder G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br. J. Gen. Practice. (2005) 55:831–7.

3. Alexander GK, Uz SW, Hinton I, Williams I, Jones R. Culture brokerage strategies in diabetes education. Public Health Nursing. (2008) 25:461–70.

4. Zeh P, Sturt JA, Sandhu HK, Cannaby AM. A systematic review of the impact of culturally-competent diabetes care interventions for improving diabetes-related outcomes in ethnic minority groups. Diabetologia. (2011) 54:S402.

5. Amos AF, McCarty Dj Fau - Zimmet P, Zimmet P. The rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010. Diabetic Medicine. (1997), 0742–3071.

6. Chopra S, Lahiff TJ, Franklin R, Brown A, Rasalam R. Effective primary care management of type 2 diabetes for indigenous populations: A systematic review. PloS One. (2022) 17.

7. Farmaki AA-O, Garfield VA-O, Eastwood SA-O, Farmer RE, Mathur RA-O, Giannakopoulou OA-O, et al. Type 2 diabetes risks and determinants in second-generation migrants and mixed ethnicity people of South Asian and African Caribbean descent in the UK. Diabetologia. (2022), 1432–0428.

8. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycaemic control. Patient Education and Counselling. (2016), 1873–5134.

9. Captieux M, Pearce G, Parke H, Wild S, Taylor SJC, Pinnock H. Supported self-management for people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. Lancet. (2017) 390:S32.

10. Nam S, Chesla C Fau - Stotts NA, Stotts Na Fau - Kroon L, Kroon L Fau - Janson SL, Janson SL. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. (2011), 1872–8227.

11. Goff LA-O, Moore A, Harding S, Rivas C. Providing culturally sensitive diabetes self-management education and support for black African and Caribbean communities: a qualitative exploration of the challenges experienced by healthcare practitioners in inner London. BMJ Open Diabetes Research. (2020), 2052–4897. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001818

12. Peyrot M, Barnett A, Meneghini L, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabetic Med. (2012) 29:682–9.

13. Mansyur CL, Rustveld LO, Nash SG, Jibaja-Weiss ML. Social factors and barriers to self-care adherence in Hispanic men and women with diabetes. Patient Educ. counselling. (2015) 98:805–10.

14. Jaam M, Awaisu A, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Kheir N. A holistic conceptual framework model to describe medication adherence in and guide interventions in diabetes mellitus. Res. Soc. Administrative Pharmacy. (2018) 14:391–7.

15. Litchfield I, Barrett T, Hamilton-Shield J, Moore T, Narendran P, Redwood S, et al. Current evidence for designing self-management support for underserved populations: an integrative review using the example of diabetes. Int. J. Equity Health. (2023) 22:188.

16. Creamer J, Attridge M, Ramsden M, Cannings-John R, Hawthorne K. Culturally appropriate health education for Type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: an updated Cochrane Review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetic Med. (2016) 33:169–83.

17. Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2003) 40:321–32.

18. Sokol R, Fisher E. Peer support for the hardly reached: a systematic review. Am. J. Public Health. (2016) 106:e1–8.

19. Olaniran A, Smith H, Unkels R, Bar-Zeev S, van den Broek N. Who is a community health worker? - a systematic review of definitions. Global Health Action. (2017), 1654–9880.

20. Mobula LM, Okoye MT, Boulware LE, Carson KA, Marsteller JA, Cooper LA. Cultural competence and perceptions of community health workers’ effectiveness for reducing health care disparities. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health. (2014), 2150–1327.

21. Palmas W, March D Fau - Darakjy S, Darakjy S Fau - Findley SE, Findley Se Fau - Teresi J, Teresi J Fau - Carrasquillo O, Carrasquillo O Fau - Luchsinger JA, et al. Community health worker interventions to improve glycaemic control in people with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. (2015), 1525–497.

22. Knowles M, Crowley AP, Vasan A, Kangovi S. Community health worker integration with and effectiveness in health care and public health in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health. (2023) 44:363–81.

23. Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu. Rev. Public Health. (2014) 35:399–421.

24. Cherrington A, Ayala Gx Fau - Elder JP, Elder Jp Fau - Arredondo EM, Arredondo Em Fau - Fouad M, Fouad M Fau - Scarinci I, Scarinci I. Recognizing the diverse roles of community health workers in the elimination of health disparities: from paid staff to volunteers. Ethnicity and Disease. (2010), 1049–510X.

25. Lehmann U, Sanders D. Policy brief: community health workers: what do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Evidence Inf. Policy. (2007) 2.

26. Little TV, Wang ML, Castro EM, Jiménez J, Rosal MC. Community health worker interventions for latinos with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr. Diabetes Rep. (2014) 14:558.

27. Schönfeld P, Preusser F, Margraf J. osts and benefits of self-efficacy: Differences of the stress response and clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2017), 1873–7528.

28. O’Cathain AA-OX, Croot LA-O, Duncan EA-OX, Rousseau N, Sworn K, Turner KA-O, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. (2019), 2044–6055.

29. Hommel KA, Hente E Fau - Herzer M, Herzer M Fau - Ingerski LM, Ingerski Lm Fau - Denson LA, Denson LA. Telehealth behavioural treatment for medication nonadherence: a pilot and feasibility study. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. (2013), 1473–5687.

30. Joo JA-O, Liu MF. Experience of culturally-tailored diabetes interventions for ethnic minorities: A qualitative systematic review. Clinical Nursing Research. (2021), 1552–3799 (.

31. Jerrim J, de Vries R. The limitations of quantitative social science for informing public policy. Evidence Policy. (2017) 13:117–33.

32. Dallosso H, Mandalia P, Gray LJ, Chudasama YV, Choudhury S, Taheri S, et al. The effectiveness of a structured group education programme for people with established type 2 diabetes in a multi-ethnic population in primary care: A cluster randomised trial. Nutrition Metab. Cardiovasc. Diseases. (2022) 32:1549–59.

33. Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2017) 17:88.

34. Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO. PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2014) 14:579.

35. Ortblad KF, Sekhon M, Wang L, Roth S, van der Straten A, Simoni JM, et al. Acceptability assessment in HIV prevention and treatment intervention and service delivery research: a systematic review and qualitative analysis. AIDS Behaviour. (2023) 27:600–17.

36. Bellhouse S, Hawkes RE, Howell SJ, Gorman L, French DP. Breast cancer risk assessment and primary prevention advice in primary care: a systematic review of provider attitudes and routine behaviours. Cancers. (2021) 13:4150.

37. Koulouri T, Macredie RD, Olakitan D. Chatbots to support young adults’ mental health: an exploratory study of acceptability. ACM Trans. Interactive Intelligent Syst. (TiiS). (2022) 12:1–39.

38. Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Brownstein JN, Johnson S, Borbon IA, Rael R, et al. The final report of the National Community Health Advisor Study: weaving the future. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona (1998).

39. United Nations. About minorities and human rights (2005). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-minority-issues/about-minorities-and-human-rights#:~:text=An%20ethnic%2C%20religious%20or%20linguistic,combination%20of%20any%20of%20these.

40. (OECD) OfEC-oaD. Trends in international migration (2005). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/31853067.pdf.

42. Covidence. Covidence systematic review software melbourne. Australia: Veritas Health Innovation (2016).

43. Fantom N, Serajuddin U. The World Bank’s classification of countries by income. The World Bank (2016).

45. CASP. CASP (Qualitative) checklist (2018). Available online at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASPQualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

46. Proudfoot K. Inductive/deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. (2022) 17:308–26.

47. Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. Implementing PRISMA-P: recommendations for prospective authors. Systematic Rev. (2016) 5:1–2.

48. Castillo A, Giachello A, Bates R, Concha J, Ramirez V, Sanchez C, et al. Community-based diabetes education for latinos. Diabetes Educator. (2010) 36:586–94.

49. Chang W, Oo M, Rojas A, Damian AJ. Patients’ Perspectives on the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a community health worker program: A qualitative study. Health Equity. (2021) 5:160–8.

50. Deitrick LM, Paxton HD, Rivera A, Gertner EJ, Biery N, Letcher AS, et al. Understanding the role of the promotora in a Latino diabetes education program. Qual. Health Res. (2010) 20:386–99.

51. Joachim-Celestin M, Gamboa-Maldonado T, Dos Santos H, Montgomery SB. A qualitative study on the perspectives of latinas enrolled in a diabetes prevention program: is the cost of prevention too high? J. primary Care Community Health. (2020) 11:2150132720945423.

52. Shepherd-Banigan M, Hohl SD, Vaughan C, Ibarra G, Carosso E, Thompson B. “The promotora explained everything”: participant experiences during a household-level diabetes education program. Diabetes educator. (2014) 40:507–15.

53. Otero-Sabogal R, Arretz D Fau - Siebold S, Siebold S Fau - Hallen E, Hallen E Fau - Lee R, Lee R Fau - Ketchel A, Ketchel A Fau - Li J, et al. Physician-community health worker partnering to support diabetes self-management in primary care. Quality in Primary Care. (2010), 1479–072.

54. Haltiwanger EP, Brutus H. A culturally sensitive diabetes peer support for older Mexican-Americans. Occupational Therapy International. (2012), 1557–0703.

55. Jia J, Quintiliani L, Truong V, Jean C, Branch J, Lasser KE. A community-based diabetes group pilot incorporating a community health worker and photovoice methodology in an urban primary care practice. Cogent Med. (2019) 6:1–14.

56. Okoro FO, Veri S, Davis V. Culturally appropriate peer-led behaviour support program for african americans with type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Public Health. (2018), 2296–565.

57. Pullen-Smith B. A descriptive study of the leadership role of community health ambassadors on diabetes-related health behaviours. In: Dissertation abstracts international: section B: the sciences and engineering (2014). p. 75(1–B(E)).

58. Shiyanbola OA-O, Maurer M, Schwerer L, Sarkarati NA-O, Wen MA-O, Salihu EY, et al. A culturally tailored diabetes self-management intervention incorporating race-congruent peer support to address beliefs, medication adherence and diabetes control in african americans: A pilot feasibility study. Patient Preference and Adherence. (2022), 1177–889X.

59. Turner CD, Lindsay R, Heisler M. Peer coaching to improve diabetes self-management among low-income black veteran men: A mixed methods assessment of enrolment and engagement. The Annals of Family Medicine. (2021), 1544–717.

60. Heisler M, Spencer M, Forman J, Robinson C, Shultz C, Palmisano G, et al. Participants’ Assessments of the effects of a community health worker intervention on their diabetes self-Management and interactions with healthcare providers. Am. J. Prev. Med. (2009) 37:S270–S9.

61. Lalla A, Salt S, Schrier E, Brown C, Curley C, Muskett O, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a community health representative program on patient experiences in Navajo Nation. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2020) 20:24.

63. Seear KH, Atkinson DN, Lelievre MP, Henderson-Yates LM, Marley JV. Piloting a culturally appropriate, localised diabetes prevention program for young Aboriginal people in a remote town. Australian journal of primary health (2019).

64. Sinclair KA, Zamora-Kapoor A, Townsend-Ing C, McElfish PA, Kaholokula JK. Implementation outcomes of a culturally adapted diabetes self-management education intervention for Native Hawaiians and Pacific islanders. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1579.

65. Shiyanbola OO, Ward E, Brown C. Sociocultural influences on african americans’ Representations of type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study. Ethnicity disease. (2018) 28:25–32.

66. Joachim-Célestin M. Investigating the stages of readiness of adults enrolled in a promotor-led diabetes prevention programme [Dr.P.H.]. United States – California: Loma Linda University (2017).

67. Davis RE, Lee S, Johnson TP, Rothschild SK. Measuring the elusive construct of personalismo among mexican american, puerto rican, and Cuban american adults. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. (2019) 41:103–21.

68. Galanti GA. The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: an overview. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. (2003), 1043–6596.

69. Wilson C, Alam R, Latif S, Knighting K, Williamson S, Beaver K. Patient access to healthcare services and optimisation of self-management for ethnic minority populations living with diabetes: a systematic review. Health Soc. Care community. (2012) 20:1–19.

70. Chang A, Cueto V, Li H, Singh B, Kenya S, Alonzo Y, et al. Community Health workers are associated with patient reported access to care without effect on service utilization among latinos with poorly controlled diabetes. J. Gen. Internal Med. (. 2015) 30:S48–S9.

71. Seneviratne SA-O, Desloge A, Haregu TA-O, Kwasnicka D, Kasturiratne A, Mandla A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of community health worker training to improve the prevention and control of cardiometabolic diseases in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The Journal of Healthcare Organisation, Provision and Financing. (2022), 1945–7243.

72. Adams LB, Richmond J, Watson SN, Cené CW, Urrutia R, Ataga O, et al. Community health worker training curricula and intervention outcomes in African American and Latinx communities: a systematic review. Health Educ. Behaviour. (2021) 48:516–31.

73. Egbujie BA, Delobelle PA, Levitt N, Puoane T, Sanders D, van Wyk B. Role of community health workers in type 2 diabetes mellitus self-management: A scoping review. PloS One. (2018) 13:e0198424.

74. Jane G, Julia de K, Olukemi B, Michel M, Yu-hwei T, Hlologelo M, et al. Household coverage, quality and costs of care provided by community health worker teams and the determining factors: findings from a mixed methods study in South Africa. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e035578.

75. Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Njue SM, Giordano TP. Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med. Education. (2017) 17:32.

76. Dean M, Street RL. A 3-stage model of patient-centred communication for addressing cancer patients’ emotional distress. Patient Educ. Counselling. (2014) 94:143–8.

77. Thorne SE, Kuo M, Armstrong E-A, McPherson G, Harris SR, Hislop TG. ‘Being known’: patients’ perspectives of the dynamics of human connection in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology. (2005) 14:887–98.

78. Vanden Bossche DA-O, Willems SA-O, Decat PA-O. Understanding trustful relationships between community health workers and vulnerable citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic: A realist evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 5(19). doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052496

79. Rivenbark JG, Ichou M. Discrimination in healthcare as a barrier to care: experiences of socially disadvantaged populations in France from a nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:31.

80. Ajayi Sotubo O. A perspective on health inequalities in BAME communities and how to improve access to primary care. Future Healthcare Journal. (2021), 2514–6645.

81. Hackett RA, Ronaldson A, Bhui K, Steptoe A, Jackson SE. Racial discrimination and health: a prospective study of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1652.

82. Capotescu C, Chodon T, Chu J, Cohn E, Eyal G, Goyal R, et al. Community health workers’ Critical role in trust building between the medical system and communities of colour. Am. J. Managed Care. (2022) 28.

83. Robert LF, Carolina Gonzalez S, Inez C, Polly Hitchcock N, Raymond FP, Ramin P, et al. Community health workers as trust builders and healers: A cohort study in primary care. Ann. Family Med. (2022) 20:438.

84. Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, Koukouli S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare. (2020) 8(21):26.

85. Grant M, Wilford A, Haskins L, Phakathi S, Mntambo N, Horwood CM. Trust of community health workers influences the acceptance of community-based maternal and child health services. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Family Med. (2017) 9:1–8.

86. LeBan K, Kok M, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 9. CHWs’ Relat. Health system communities. Health Res. Policy Systems. (2021) 19:1–19.

87. Kok MC, Ormel H, Broerse JE, Kane S, Namakhoma I, Otiso L, et al. Optimising the benefits of community health workers’ unique position between communities and the health sector: a comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Global Public Health. (2017) 12:1404–32.

88. Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. (2013) 12:1–5.

89. Wilkinson A, Whitehead L, Ritchie L. Factors influencing the ability to self-manage diabetes for adults living with type 1 or 2 diabetes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2014) 51:111–22.

90. McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:419.

91. Yoon S, Ng JH, Kwan YH, Low LL. Healthcare professionals’ views of factors influencing diabetes self-management and the utility of a mHealth application and its features to support self-care. Front. Endocrinology. (2022) 13:793473.

92. Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology. (2016), 1930–7810.

93. McLafferty S, Preston V. Who has long commutes to low-wage jobs? Gender, race, and access to work in the New York region. Urban geography. (2019) 40:1270–90.

94. Clark K, Shankley W. Ethnic minorities in the labour market in Britain. Ethnicity Race Inequality UK: Policy Press;. (2020) p:127–48.

95. Berkowitz SA, Gao X, Tucker KL. Food-insecure dietary patterns are associated with poor longitudinal glycaemic control in diabetes: results from the Boston Puerto Rican Health study. Diabetes Care. (2014) 37:2587–92.

96. Essien UR, Shahid NN, Berkowitz SA. Food insecurity and diabetes in developed societies. Curr. Diabetes Rep. (2016) 16:1–8.

97. Heerman W, Wallston K, Osborn C, Bian A, Schlundt D, Barto S, et al. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes self-care behaviours and glycaemic control. Diabetic Med. (2016) 33:844–50.

98. Johnson PJ, O’Brien M, Orionzi D, Trahan L, Rockwood T. Pilot of community-based diabetes self-management support for patients at an urban primary care clinic. Diabetes Spectr. (2019) 32:157–63.

99. Mayer VL, McDonough K, Seligman H, Mitra N, Long JA. Food insecurity, coping strategies and glucose control in low-income patients with diabetes. Public Health Nutr. (2016) 19:1103–11.

100. Downer S, Clippinger E, Kummer C, Hager K, Acosta V. Food is medicine research action plan. In: Centre for health law and policy innovation of harvard law school (2022).

101. Levi R, Bleich SN, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and diabetes: overview of intersections and potential dual solutions. Diabetes Care. (2023) 46(9):dci230002.

102. Istepanian RSH, Al-Anzi TM. m-Health interventions for diabetes remote monitoring and self-management: clinical and compliance issues. Mhealth. (2018) 4:4.

103. Poduval S, Ahmed S, Marston L, Hamilton F, Murray E. Crossing the digital divide in online self-management support: analysis of usage data from heLP-diabetes. JMIR Diabetes. (2018) 3:e10925.

104. Hernandez MA-O, Gibb JA-O. Culture, behaviour and health. Evol Med Public Health. (2020), 2050–6201.

105. Mora N, Golden SH. Understanding cultural influences on dietary habits in Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latino patients with type 2 diabetes: a review of current literature and future directions. Curr. Diabetes Rep. (2017) 17:1–12.

106. Piombo L, Nicolella G, Barbarossa G, Tubili C, Pandolfo MM, Castaldo M, et al. Outcomes of culturally tailored dietary intervention in the North African and Bangladeshi diabetic patients in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. (2020) 17:8932.

107. Li-Geng T, Kilham J, McLeod KM. Cultural influences on dietary self-management of type 2 diabetes in East Asian Americans: a mixed-methods systematic review. Health Equity. (2020) 4:31–42.

108. Pardhan S, Nakafero G, Raman R, Sapkota R. Barriers to diabetes awareness and self-help are influenced by people’s demographics: perspectives of South Asians with type 2 diabetes. Ethnicity Health. (2020) 25:843–61.

109. Thornton PL, Salabarría-Peña Y Fau - Odoms-Young A, Willis Sk Fau - Kim H, Kim H Fau - Salinas MA Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: the role of social support. Journal of Maternal and Child Health. (2006), 1092–7875.

110. Lopez C, Vazquez M, McCormick AS. Familismo, respeto, and bien educado: traditional/cultural models and values in latinos. Family Literacy Practices Asian Latinx Families: Educ. Cultural Considerations: Springer;. (2022) p:87–102.

111. Zamudio CD, Sanchez G, Altschuler A, Grant RW. Influence of language and culture in the primary care of spanish-speaking latino adults with poorly controlled diabetes: A qualitative study. Ethnicity and Disease. (2017), 1049–510X.

112. Soltero EG, Olson ML, Williams AN, Konopken YP, Castro FG, Arcoleo KJ, et al. Effects of a community-based diabetes prevention program for latino youth with obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Obesity. (2018) 26:1856–65.

113. Niemann Y. Stereotypes about chicanas and chicanos. Counselling Psychol. - COUNS Psychol. (2001) 29:55–90.

114. Mendez-Luck CA, Anthony KP. Marianismo and caregiving role beliefs among U.S.-born and immigrant mexican women. Journals of Gerontology. (2015), 1758–5368.

115. Soltero EG, Peña A, Gonzalez V, Hernandez E, Mackey G, Callender C, et al. Family-based obesity prevention interventions among Hispanic children and families: a scoping review. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2690.

116. Nuñez A, González P, Talavera GA, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Roesch SC, Davis SM, et al. Machismo, marianismo, and negative cognitive-emotional factors: findings from the hispanic community health study/study of latinos sociocultural ancillary study. J Lat Psycol. (2015).

117. Hu J, Wallace DC, McCoy TP, Amirehsani KA. A family-based diabetes intervention for hispanic adults and their family members. Diabetes Educator. (2013) 40:48–59.

118. Leung M, Barata Cavalcanti O, Dada A, Brown M, Mateo K, Yeh M-C. Treating obesity in latino children: A systematic review of current interventions. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. (2017) 6:1–15.

119. Hildebrand JA, Billimek J, Lee JA, Sorkin DH, Olshansky EF, Clancy SL, et al. Effect of diabetes self-management education on glycaemic control in Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. (2020) 103:266–75.

120. Gucciardi E, Chan VW-S, Manuel L, Sidani S. A systematic literature review of diabetes self-management education features to improve diabetes education in women of Black African/Caribbean and Hispanic/Latin American ethnicity. Patient Educ. Counselling. (2013) 92:235–45.

121. Tolentino DA, Ali S, Jang SY, Kettaneh C, Smith JE. Type 2 diabetes self-management interventions among asian americans in the United States: A scoping review. Health Equity. (2022) 6:750–66.

122. Bivins BL, Hershorin IR, Umadhay LA. Haitian American women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: An integrative review. Acta Sci. Women’s Health. (2019) 1:3.

123. Lambert S, Schaffler JL, Brahim LO, Belzile E, Laizner AM, Folch N, et al. The effect of culturally-adapted health education interventions among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) patients with a chronic illness: A meta-analysis and descriptive systematic review. Patient Educ. Counselling. (2021) 104:1608–35.

124. Valdez R, Spinler K, Kofahl C, Seedorf U, Heydecke G, Reissmann D, et al. Oral health literacy in migrant and ethnic minority populations: a systematic review. J. Immigrant Minority Health. (2022) 24:1061–80.

125. van der Gaag M, van der Heide I, Spreeuwenberg PMM, Brabers AEM, Rademakers JJDJM. Health literacy and primary health care use of ethnic minorities in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv. Res. (2017) 17:350.

126. Adebajo A, Blenkiron L, Dieppe P. Patient education for diverse populations. Rheumatology. (2004) 43:1321–2.

127. Greenhalgh T, Collard A Fau - Begum N, Begum N. Sharing stories: complex intervention for diabetes education in minority ethnic groups who do not speak English. BMJ. (2005), 1756–833.

128. Samanta A, Johnson M, Guo F, Adebajo A. Snails in bottles and language cuckoos: An evaluation of patient information resources for South Asians with osteomalacia. Rheumatol. (Oxford England). (2009) 48:299–303.

129. Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Taylor L, Krieger J, Nelson KM. Improvements in physical activity and some dietary behaviours in a community health worker-led diabetes self-management intervention for adults with low incomes: results from a randomized controlled trial. Trans. Behav. Med. (2021) 11:2144–54.

130. Allen JO, Concha JB, Mejía Ruiz MJ, Rapp A, Montgomery J, Smith J, et al. Engaging underserved community members in diabetes self-management: evidence from the YMCA of greater richmond diabetes control program. Diabetes Educ. (2020) 46:169–80.

131. Slater A, Cantero PJ, Alvarez G, Cervantes BS, Bracho A, Billimek J. Latino health access: comparative effectiveness of a community-initiated promotor/a-led diabetes self-management education program. Fam Community Health. (2022) 45:34–45.

132. Ye W, Kuo S, Kieffer EC, Piatt G, Sinco B, Palmisano G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a diabetes self-management education and support intervention led by community health workers and peer leaders: projections from the racial and ethnic approaches to community health detroit trial. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:1108–15.

133. Raymond JK, Reid MW, Fox S, Garcia JF, Miller D, Bisno D, et al. Adapting home telehealth group appointment model (CoYoT1 clinic) for a low SES, publicly insured, minority young adult population with type 1 diabetes. Contemp Clin. Trials. (2020) 88:105896.