94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Built Environ. , 07 March 2025

Sec. Sustainable Design and Construction

Volume 11 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2025.1549313

Mohamed Salah Ezz1,2*

Mohamed Salah Ezz1,2* Mohamed Ahmed F. Mahdy3,4

Mohamed Ahmed F. Mahdy3,4 Saleh Baharetha1

Saleh Baharetha1 Mohammad A. Hassanain5,6

Mohammad A. Hassanain5,6 Mohammed M. Gomaa7,8

Mohammed M. Gomaa7,8This study presents an assessment methodology to evaluate design studio facility effectiveness by conducting a post-occupancy evaluation case study. The effectiveness of architectural studios determines how students learn in architecture schools because it affects their creativity levels and productivity and educational achievement. POE represents an essential strategy for educational facility assessment which helps verify their match with user requirements. The study follows a sequential method that initiates with a study of architectural studio importance and POE performance in academic spaces. The researchers conducted their study at Onaizah Colleges located in Qassim, Saudi Arabia by implementing both qualitative and quantitative data gathering techniques which included walkthrough inspections and semi-structured interviews and the distribution of questionnaires. The study identifies a methodical several-step system to evaluate architectural studio performance. A structured categorization of performance criteria included ten groups that evaluated functional and technical operations with behavioral capabilities across environmental comfort and spatial organization and technological implementation and user satisfaction. Educational architecture proves its dependency on fundamental features of comfort together with functionality based on the study outcomes. The framework enables professional users to methodically analyze studio layouts for enhancing their educational performance and user satisfaction. The research analysis demonstrates how user-centered design approaches must be used to improve student learning because it identifies important performance elements. The research uniquely utilizes a systematic approach to studio assessment which delivers essential information to facilities management regarding studio administration to enhance educational outcomes.

The education process at universities develops three fundamental aspects of student growth: personality and communication abilities and brain development. Built environment design stands as a leading factor that determines accessibility and educational outcomes in student experiences. Educational interior design has significant effects on both students and teaching staff who work in architectural design studios. Education studios function as live-work spaces that enable students to participate in innovative problem-solving group work and intellectual growth (Hesham, 2022). Every facility that is strategically planned supports learning activities through the combination of collaborative spaces and secure areas and features stimulating environments and suitable social areas for students. (Hassanain, 2008).

The average daily student time inside architectural studios ranges between four and 10 hours, depending on their workload, so it is important to study their impact on performance and wellbeing. The assessment process known as post-occupancy evaluation (POE) gives architects, planners, and facility managers an essential understanding of educational facility success so they can make decisions regarding improvement needs. POE represents “the systematic assessment of facilities after prolonged occupancy to determine their impact on organizational goals and user-occupant requirements” (Preiser, 1988).

Even though POE offers numerous advantages, educational institutions seldom utilize this method because universities tend to exclude it from their structural contracts with builders (Smitha et al., 2023). Buildings serve as essential facilities for learning, so post-occupancy evaluations lead to actionable suggestions for improving the studio environment (Sambe and Korna, 2020).

This research examines important performance indicators of educational architectural studios in Onaizah College’s educational buildings located in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The study determines how well these studios accomplish their success factors by using a systematic assessment system for their fundamental performance needs. The study produces data that proves beneficial for architects together with planners and facility managers who supervise educational facilities. The main finding of this research demonstrates that design studios for architecture should utilize performance measures appropriate for their individual academic and environmental settings.

Through the convergence of objective and subjective components, architecture transforms reality by combining creative elements with structural arrangements. The educational environment of architecture needs to create conditions that develop innovation and critical thinking abilities. The architectural design studio represents a vital element of architectural study; thus, it needs to create dynamic areas that promote experiential educational methods. The development of the studio space needs to adopt a student-driven strategy that supports students in their intellectual requirements as well as social interactions and emotional development (Ozorhon and Sarman, 2023), (Saifudin Mutaqi, 2018), (Shaqour and Abo Alela, 2022).

The educational process in design studios uses interactive exploratory techniques that produce iterative improvement through design activity. Students at studio classes cooperate through model-building and sketching activities, as well as group discussions with peers and instructors, to develop a stronger architectural understanding. According to the literature, design studios face criticism due to their unclear objectives and evaluation standards (Lueth, 2008; Evans et al., 1987; Zhong et al., 2022; Monroe et al., 2019; Sedghikhanshir et al., 2022; ezz and Elsayed, 2024).

Four features distinguish the contemporary design studio from its historical counterpart as a learning setting: the process of customized design, which requires imagination; the fact that a student’s behavior, character, and emotions are publicly shown; and the impact of the instructors on the project’s final product. In contrast to the mentioned features, the traditional classroom has traits like (a) the student’s mindset is that of a blank slate, (b) creativity is not required, (c) the instructor has no direct control over the method by which students produce their work, and (d) the attitude that students’ personalities are unimportant, primarily because of the large class sizes (Evans et al., 1987; Zhong et al., 2022; Monroe et al., 2019; Sedghikhanshir et al., 2022; ezz and Elsayed, 2024; Hassanain et al., 2020; Mahmoud et al., 2019).

The Environmental Stress Theory, coupled with other supporting scientific evidence, shows that inadequate studio planning leads to work stress alongside lowered productivity, which proves that adequate studio ventilation, natural light and proper ergonomics are essential (Elnaklah et al., 2023). According to the Prospect-Refuge Theory, educational facilities provide ideal performance conditions when they combine open areas and private zones that create protected spaces for productive student engagement (El-Darwish and El-Gendy, 2018). Theories related to spatial cognition demonstrate that student learning becomes more efficient when intuitive spaces are designed because the spatial environment helps reduce mental congestion (Fatma et al., 2017).

Several critical research questions guide this study: What are the key performance parameters of architectural design studios, and how do these compare to traditional learning environments? How do technical, functional, and behavioral elements influence the effectiveness of the architectural design studio at Onaizah Colleges? Based on post-occupancy evaluation findings, what successes and challenges can be identified in the current studio setup? Finally, what evidence-based recommendations can be proposed to enhance the architectural design studio environment?

The research presents an innovative structure that enables a comprehensive assessment of architectural design studio performances. This study provides a different approach through the incorporation of diverse technical, functional and behavioral indicators for studio performance assessment because previous work only focused on single performance factors. The application of post-occupancy evaluation (POE) in Saudi Arabian architectural education makes this research especially unique. This research merges user assessments and performance criteria to generate fresh knowledge about optimizing design studios for educational effectiveness and creative development. Results from this study enable architects, along with planners and administrators, to develop better architectural studios all around the world through a distinct assessment tool.

This study advances existing research by developing a multi-dimensional framework that integrates technical, functional, and behavioral performance elements (45 indicators in total) to assess architectural design studio facilities holistically. Unlike prior studies that often focused on isolated factors (e.g., thermal comfort or acoustics), our framework synthesizes diverse criteria into a unified evaluation tool.

This part of the study reviewed the related literature to give a theoretical backdrop for the topics related to the scope of this study. One of the recent POE studies of educational facilities was conducted by Sambe and Korna (2020) to assess the condition and performance of the School of Environmental Studies building at Nuhu Bamalli Polytechnic, Zaria, Nigeria. The study examined three main performance indicators, namely, functional, technical, and behavioral performance indicators. Data were collected using questionnaires, walkthroughs, and observation. A selected building users were asked to report their feedback and experience about the facility. The study’s results highlighted deficiencies in the adequacy of storage spaces, noise levels, and the quality and cleanliness of washrooms/toilets. It also indicated that inadequate facilities led to actions that impacted users’ comfort and performance in the workplace. The study suggested that higher education institutions in Nigeria might improve building performance by incorporating user feedback into maintenance policies and planning for future infrastructure expansion during the design stage.

In the context of addressing the different impacts of thermal comfort on students in ordinary classrooms and students in architectural design studios, (Evans et al., 1987) conducted a POE study in a university building in Jordan during the heating season with the aim of investigating the potential individual differences among students. Continuous monitoring was performed combined with periodic measures for mean radiant temperature, indoor temperature, relative humidity and air speed. Subjective data was collected from students using several tools such as questionnaires, observations and focus groups. The results showed a noticeable difference in indoor air quality between classrooms and architecture design studios. While 53% of students reported feeling warm in design studios, it was found that 58.8% of students reported feeling cold in lecture halls, and the students thought that they were more productive when they felt the surrounding environment was cooler.

In terms of investigating the impacts of thermal comfort in producing an effective learning environment, (Smitha et al., 2023) conducted a study to examine the thermal performance and comfort of a design studio classroom at Universitas Indonesia, Depok. A questionnaire survey was distributed to Ninety-one students (20% male, 80% female) to report their feedback about their thermal perspective. Humidity and temperature conditions were recorded through field measurements throughout two lecture periods. The study found that studio classrooms can function well thermally, even if some users prefer cooler temperatures. The study emphasized the importance of understanding subjective and objective components of thermal comfort in creating an effective learning environment. The authors suggested that future research should consider individual preferences and other environmental influences.

To improve the interior context of educational environments, a study was conducted by El-Darwish and El-Gendy (2018) to evaluate thermal comfort in higher education buildings in Egypt’s hot desert climate. The authors discussed three POE quantitative or qualitative strategies for improving interior conditions and underlined the need to use several methods to verify findings. The research conducted a POE questionnaire survey as an interactive evaluation and revealed that just one-third of spaces meet occupant satisfaction standards. However, an assessment of a sample of indoor spaces reveals that two-thirds meet occupant satisfaction standards based on actual measurements and simulation outcomes. The study underscores a notable disparity in results. It emphasizes that indoor spaces should be managed to offer conditions that users genuinely perceive as favorable and that effectively respond to their needs.

A similar study was conducted by Fatma et al. (2017), Hassanain et al. (2018). To assess thermal comfort in two primary schools built on the same plane in different temperature zones during two seasons. The study depended mainly on two stages; the first stage included incorporating measurements using meteorological equipment. The obtained data was used to quantify the physical factors of the thermal atmosphere, such as relative humidity rate, wind speed and temperature within classrooms. The second stage was a psychological investigation that aimed to support the findings of the first stage by using inquiry with building users. The study revealed that classroom interior temperatures are deemed tolerable throughout the winter months in schools in the northern part of the country. However, the study demonstrated that the internal thermal atmospheres in the addressed schools in the south are inadequate in both seasons. The authors noted that the rate of relative humidity in the north and the ambient temperature in the south are the main determinants of wintry thermal comfort, and users in southern schools report temperatures that are greater than those of users in northern schools.

For the aim of enhancing future educational projects, (Ranjbar, 2019), conducted a POE study of an academic building at a Midwestern University to investigate areas of user dissatisfaction. The building was remodeled and followed by performing a POE with selected building users, including faculty, students, and staff. Several interviews were done with the staff responsible for the project, including the construction manager, architect, Interior designer, and the university facility planning director. A questionnaire survey was distributed to 45 faculty and staff and 750 students. The study results showed that, overall, users were satisfied with the remodeled building, although there were a few minor concerns related to navigation within the building and temperature.

Thermal comfort is a mental state signifying contentment with the thermal environment, assessed through individual perception (Mitkees et al., 2022). Thermal comfort of educational environments is one of the key IEQ factors that could impact students’ health and academic performance (Puckett, 2022). It has been acknowledged that thermal comfort plays a significant role in the general comfort of interior space users. Therefore, improving indoor comfort conditions is just as crucial for a student’s general comfort in an educational setting as it enhances learning performance (Hesham, 2022). Thermal comfort is critical for architectural design students who spend much time learning and working at high metabolic rates (Evans et al., 1987; Al-Jokhadar et al., 2023a). Bad thermal comfort in classrooms could lead to occupant dissatisfaction. This issue is particularly notable in art classrooms and design studios, where high activity levels and specific thermal comfort needs are essential (Ahmed et al., 2021; Aydin and Li, 2019; Gad et al., 2022).

Acoustics refers to the sound-related qualities of various elements and spans multiple professions and fields of study, including architecture, engineering, and all science-related disciplines. Acoustic comfort refers to the wellbeing of building occupants, achieved by reducing or eliminating unwanted noise from the environment or the building itself. It also involves enhancing speech clarity and music quality according to the building’s function, making the space more productive and beneficial for occupants. Well-designed design studios that prioritize acoustic comfort enable students to perform better and protect them from the negative effects of unwanted noise-related issues (Gad et al., 2022; Benjamin and Alibaba, 2019). Poor acoustic conditions in educational indoor environments negatively affect students’ cognitive performance and wellbeing, ultimately hindering their productivity. Irrelevant speech from single and multiple speakers in design studios, combined with noise from printers, phones, and HVAC systems, can diminish the overall quality of the acoustic environment (Building, 2022).

In architecture, daylighting focuses on using natural light as the main illumination source during the day, which, when effectively integrated, creates a visually comfortable space with a connection to the outdoors. Producing artificial light from fossil fuel-powered sources is unsustainable, as fossil fuels are expensive, non-renewable, and release by-products that harm the environment (Idowu, 2020 and Phuong et al., 2023). The design studio’s focus extends beyond just producing images; it also serves as a space for exploring design concepts. Therefore, the room should stimulate users’ creativity in architectural design (Mandala, 2019). A building’s daylighting solution relies on the natural characteristics of its location. Consequently, each project’s daylighting approach must include a scientifically rigorous analysis and evaluation tailored to its specific location (Mandala, 2019).

In educational facilities, where students primarily occupy classrooms, the issue of poor indoor environmental quality (IEQ) emerges (Al-Jokhadar et al., 2023b). In recent years, indoor air quality has gained significant attention from researchers aiming to enhance indoor living environments. These factors are especially critical in school buildings, as poor indoor air quality (IAQ) can negatively impact students’ health and performance. Students spend a substantial portion of their day indoors. Poor indoor air quality in educational spaces can lead to health issues, causing student absenteeism and adverse health symptoms while also lowering academic concentration levels. Classroom ventilation’s primary purposes are to reduce health risks, minimize occupant discomfort, and mitigate any negative impacts on learning and productivity (Jahangiri et al., 2018).

Universities and colleges should offer a safe and secure environment for students to develop necessary life skills after graduation. Safe educational environments increase student satisfaction, making them less likely to withdraw (Iranmanesh and Onur, 2022). Several possible hazards and risks in universities, like other industries and organizations, can face many threats. Students and staff spend a significant portion of their day in classes, making safety a top priority for universities. The design studio is a crucial component of the educational environment and must meet standards for safety, color, equipment, noise, lighting, enough space, and air conditioning (Aydin and Li, 2019). Unsafe educational environments can negatively impact students, instructors, and visitors. Therefore, they should be designed to meet safety requirements concerning the building, equipment, and environmental factors such as lighting, noise, temperature, and humidity (Al Rahhal Al Orabi and Al-Gahtani, 2022).

In most architecture schools, the architecture Studio is central to the architectural learning process. Through this process, students are trained to develop skills in designing architectural spaces grounded in understanding the site, its function, and aesthetics (Shaqour and Abo Alela, 2022 and Saifudin Mutaqi, 2018). The quality of a design studio plays a crucial role in the effective execution of architectural projects. Due to its unique morphological characteristics, the design studio is a space where fundamental design activities occur (Jahangiri et al., 2018; Iranmanesh and Onur, 2022; Al Rahhal Al Orabi and Al-Gahtani, 2022). Understanding the relationship between people and their environment is a central focus in behavioral sciences, as human behaviors, attitudes, and values play a key role in shaping environments that meet diverse needs. A crucial element of the educational process is the interaction between students and their environment, which reflects the influence of that environment on behavior (Widiastuti et al., 2020).

It is a major concern to understand the mutual relationship between people and their built environment since it affects human behaviors, attitudes, and values. Consequently, architects hold significant responsibility for designing buildings that engage with their users and fulfill their needs (Gad et al., 2022; Al Rahhal Al Orabi and Al-Gahtani, 2022). In educational environments, patterns have a substantial impact on students’ mood; buildings’ interior finishes, such as color, size, and patterns, have a considerable effect on students’ mood buildings. Color influences emotions and physiology, affecting mood and performance. Additionally, it has a physical, psychological, and social impact on human life (Obeidat and Al-Share, 2012). In architectural design studios, materials used for walls, floors, ceilings, and furniture contribute to the space’s comfort, aesthetics, and functionality. Thoughtful interior finishes create an inspiring atmosphere and support students in their academic and creative pursuits by fostering an environment tailored to their needs (Corluluoglu and Karakaya, 2022).

Supporting services in architectural design studios are essential for enhancing the performance and productivity of architecture students. These services, which include access to printing and plotting facilities, material storage, technology resources, and flexible workspace arrangements, enable students to execute their designs efficiently and explore creative solutions without unnecessary interruptions (Corluluoglu and Karakaya, 2022; Kamalipour et al., 2014). The availability of resources such as large-format plotters, advanced software, and high-quality model-making tools allows students to refine their projects with professional precision, promoting skill development and increasing project quality. Moreover, efficient technical support and equipment maintenance ensure that students can rely on the studio as a functional workspace (Corluluoglu and Karakaya, 2022).

In architecture, urban design, and planning education, design studios are spaces for imagination, critique, debate, creativity, consultation, and collaboration (Emam et al., 2019). Architectural design has long been a collaborative process that relies on participatory practices. It involves skilled individuals such as architects, engineers, and clients working together toward a common goal. Consequently, there is growing interest in creating a collaborative design studio environment and enhancing architecture students’ skills. Architecture students engage in design studios with peers and teachers, fostering communication and debate. Additionally, they must collaborate to reach a common goal and prepare for the collaborative character of the architectural profession. In design studios, collaborative learning focuses on the learner. This empowers students to collaborate and learn more about studio projects. In contrast, a teacher-centered model relies solely on instructors for authority and knowledge (Demirbas and Demirkan, 2000).

While many architecture, urban design, and planning students often work on their projects individually, there is a crucial tendency to learn and grow through debate, challenge, and discussion with others in the design studio. Issues like privacy and territoriality are essential considerations in architectural design studios, where students require personal space to focus, create, and reflect on their work (Demirbas and Demirkan, 2000; Hassanain and Mohammed, 2012).

To accomplish this paper’s stated goals, a developed methodology that evaluates an existing indoor environment in architectural design studios to determine how well it supports and satisfies the explicit and implicit human needs and values of the people for whom the building was intended. The authors first reviewed the published literature on the applications and advantages of POEs and indoor environmental requirements in architectural design studios. The methodology of the study compromised three stages as follows (Figure 1):

The planning stage includes building selection, calculating sample sizes, conducting site visits, and coordinating with management and academic staff. It also includes conducting a user satisfaction survey to gather qualitative feedback from architecture design studio users on their experiences with the designed environment.

- The data collection stage, which includes conducting focus group meetings, walkthroughs, building investigation, and distributing questionnaire surveys to architectural design studio users.

- The data analysis stage includes organizing data, filtering information, and investigating the survey results to illustrate the level of satisfaction with the specified indoor environmental performance criteria.

To achieve the objectives of the study, The following case study was implemented within the studios of the Architecture department, both male and female, Onaizah Colleges, located in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The case study buildings stand tall with three floors and an elongated shape plan that provides a sense of openness and accessibility, as shown in Figure 2. Various state-of-the-art laboratories are situated on the ground floor, creating a hub for scientific exploration and experimentation. The first floor houses spacious study halls designed to foster a focused learning environment for students. The second floor is dedicated to architectural studios, where creativity flourishes amid abundant natural light. Interior courtyards within the building feature a vibrant cafeteria where students gather and relax between classes. Six staircases efficiently connect all floors, while three main entrances welcome students and visitors. In addition, the buildings are equipped with discreet back emergency exits, ensuring safety and smooth circulation throughout the facility.

This study employed various data-gathering techniques, including surveys, interviews, walkthrough inspections, and photographic documentation. Over several years, 75 architecture students, comprising freshmen, juniors, and seniors, completed the questionnaire. Additionally, the research included interviews with three architectural studio instructors and fifteen architecture students from various years, ranging from junior to senior level. The POE team conducted a walkthrough evaluation within the selected architectural design studio. This evaluation took place over eight working hours of a typical business day and encompassed both male and female studios. The case study building features three floors.

Ground floor: State-of-the-art laboratories supporting scientific exploration

First Floor: Spacious study halls fostering focused learning.

Second Floor: Dedicated architectural studios for design and collaboration.

The architectural design studios for design studio courses are situated on the second floor of the College of Engineering and Information Technology in male and female buildings. The spaces occupy several design studios with a variety of layouts, as illustrated in Figures 3–5. There are eight architectural design studios located in the male student building and six in the female building. The area of the addressed design studios ranges (51 m2 and 106 m2) on average, with a 3.4 m height ceiling. The maximum occupancy rate of the studios is 24 students. The whole studio space can accommodate up to 75 architecture students from various years (freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior). The area of studio spaces is designed in alignment with the structural framework to offer an open, adaptable space that enhances the rhythmic flow. The design studios are distributed along corridors with varying orientations, primarily west and south. The studios have operable windows that allow for natural ventilation with no shading devices, and the students have control of the air conditioning system.

A total of 45 performance indicators were synthesized from various literature sources to evaluate the architectural design studio in the case study. These indicators are categorized according to their respective technical and functional performance elements. To establish a systematic approach that prioritizes the needs of users within the architectural design studio facility, the authors conducted a comprehensive review of existing literature to study knowledge sectors pertinent to the specified technical, functional, and behavioral performance criteria. The identified effectiveness elements, along with their corresponding references, are presented in the study as shown in Table 1.

This department collects data through many techniques, such as interviews, questionnaire surveys, and walkthrough inspections (Table 2).

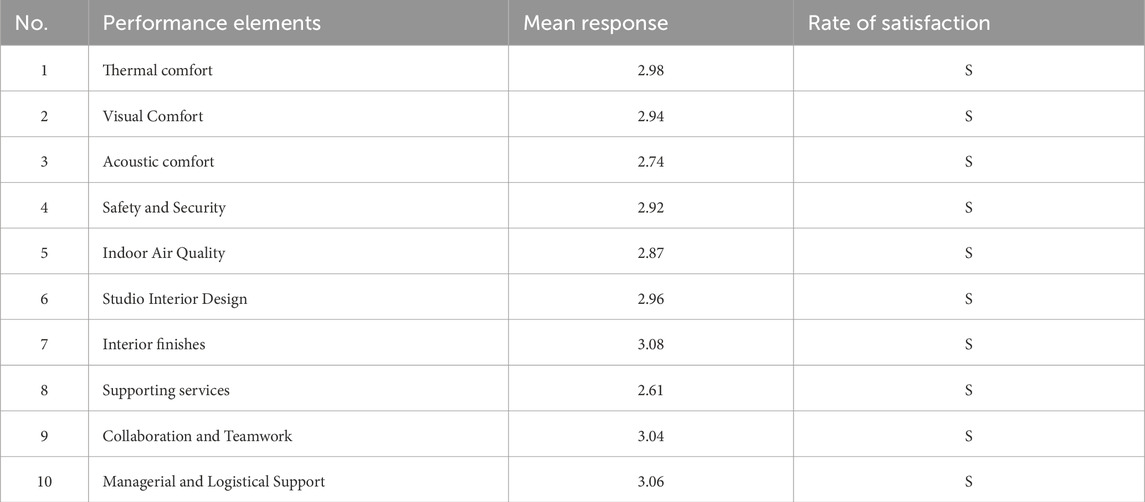

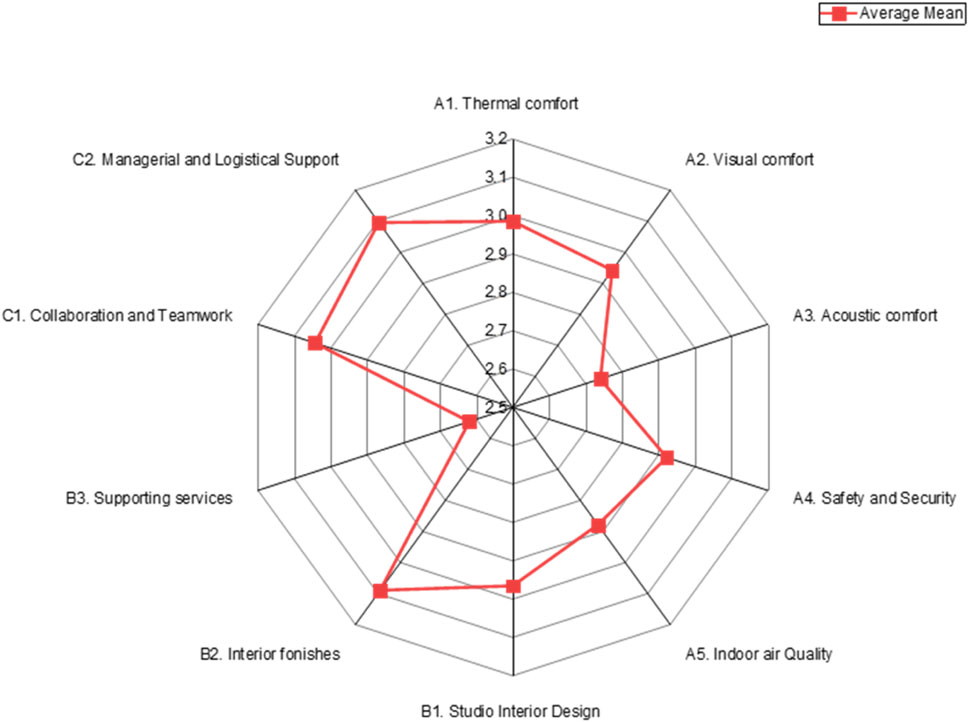

Table 2. Summary of the Mean Responce for Performance Elements and their Associated Rate of Satisfaction.

The authors carried out the walkthrough inspection. Students and studio instructors were informed before the walkthrough to ensure cooperation and increase understanding and tolerance. The experiment was carried out on normal days when regular design studio classes were held to replicate the actual scenario.

Several key observations have been made during the architectural design studio’s walkthrough. The absence of territoriality for each student fosters a more open and collaborative workspace, allowing flexibility in seating arrangements and encouraging interaction. The flexible tables enhance this dynamic environment, enabling students to adapt their workspaces for group projects or personal tasks. The thermal comfort of the design studio was ensured by centralized air conditioning, maintaining a consistent and comfortable temperature. Similarly, the lighting system effectively combines natural and artificial light, creating a uniformly illuminated workspace. However, lacking IT facilities could hinder productivity, as students may require access to digital tools for design software and research. On the positive side, thermal comfort and lighting appear well addressed, contributing to a conducive working environment. The absence of plotters and model-making materials could limit students’ ability to produce physical design outputs, which are essential for architectural projects. The lack of available materials for model-making could further impede hands-on learning and creativity. Figure 6 shows images obtained from design studios during the conduction walkthrough and observation.

The results from the questionnaire survey aimed to determine the degree of satisfaction with the performance of the architectural design studio. Respondents were asked to assess their satisfaction using 45 performance elements categorized into three main groups. Satisfaction was measured on a four-point Likert scale, where “4”indicated extremely satisfied, “3”represented satisfied, “2”denoted dissatisfied, and “1”indicated extremely dissatisfied. A synopsis of the average input for the technical, functional, and behavioral indicators elements is presented in Table (Hassanain, 2008). The analysis included 52 responses to the occupants’ satisfaction survey, which informed findings and recommendations for enhancing the performance of the case study building. These findings reflect the level of occupant satisfaction across the identified indicators for each of the 45 performance elements. The analysis of the performance indicators involved calculating relevant weighted means, utilizing the formula proposed by Elnaklah et al. (2023); Equation 1. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, a measure of internal consistency reliability for a set of items intended to assess a single construct, was calculated to assess the reliability of the scale. The formula used is:

In this context, K represents the number of items (45 performance indicators). At the same time, the variance associated with each element was found to be 55.23, and the variance associated with the total scores was calculated to be 190. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale is 0.726, indicating a high level of internal consistency reliability.

In order to ascertain and assess occupant satisfaction, the average satisfaction for each PI was then computed. Every satisfaction level was given a weight based on its classification. The following weights were applied to the satisfaction levels: “very satisfied” received four points; “satisfied” received three; “unsatisfied” received two; and “strongly dissatisfied” received one point (Equation 2). The calibration, matching weight, and satisfaction rate for every performance element are shown in Table 3. For every performance measure, the average satisfaction (mean) was determined using the equation that follows.

Where: S_sub j: is the weighted mean response.

The questionnaire was created and distributed to students using the Architectural Design Studio at Onaizah Colleges–both male and female. The number of the obtained questionnaire survey reached a total of 52 responses, which represented a percentage of (69.33%) of the total 75 distributed surveys. Participants in the questionnaire were asked to choose one of four assessment phrases to indicate how satisfied (or not) they were with the specified performance elements. The questionnaire survey contained (45) performance elements grouped under ten performance categories, including indoor air quality, sound comfort, visual comfort, safety and security, Thermal comfort and acoustic comfort, studio interior design, Managerial and Logistical Support, interior finishes, supporting services collaboration and teamwork. The respondents’ satisfaction rates for each of the performance elements are explained as follows.

The residents’ rates of satisfaction with the five technical performance requirements are discussed herein as follows.

This namely, category included four performance elements: the ambient temperature in the studio during the morning times, the ambient temperature in the studio during the evening times, the impact of temperature on focus and work activity, and the general perception of the thermal environment in the studio. Respondents’ responses showed that the building’s overall grade of thermal comfort recorded a mean score of 2.98. These results showed that respondents were “Satisfied” With the included performance Items, as shown in Table 4; Figure 7, with a slight difference among the four performance elements.

All elements and attributes associated with this indicator: adequacy of lighting at your workstation, lighting distribution and quality (glare and reflections), natural sunlight in the studio and the suitability of lighting intensity (lux levels) being for work in the studio achieved mean values of (2.92), (3.32), (3.03), (2.69) and (2.75), correspondingly. User responses generally highlighted this mean value of Visual comfort (2.94), which was closer to the moderate level of satisfaction, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 7.

Three of four performance indicators related to acoustic comfort (the level of noise produced in the studio space, sound clarity and quality and overall impression of the sound environment in the studio) recorded mean scores of (2.96), (2.86) and (2.75) respectively, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 7, which indicates that their degree of satisfaction is moderate. The rest of the performance indicators related to acoustic comfort (Noise level coming from outside the studio) achieved an Average value of (2.38), indicating That user satisfaction with this performance element was less than the minimum. Based on the feedback from users, the overall average value of the quality of acoustic comfort was (2.74), Which suggests that the quality of acoustic comfort Reached a degree of satisfaction that is less than average.

This category includes five performance elements, as listed in Table 2. Three of the five performance elements under safety a security (ease of identifying emergency exits for occupants and visitors, ease of evacuating the building in case of fire emergencies and availability of safety roles) Average grades recorded (3.01), (3.2) and (3.0) in contrast, revealing that their level of satisfaction was higher than the moderate level. However, the rest of the performance elements (easy to identify and reach The alarm system for fire and quality and Visualize the building’s fire safety systems) achieved a mean value of (2.75) and (2.61) respectively, suggesting that their Satisfaction level was below the moderate level. The average value of the quality of safety and security was (2.93) This is very close to a moderate level of satisfaction.

This performance category included three performance elements. Two of these performance elements (quality and freshness of the indoor air and overall perception of indoor air quality) achieved mean values of (2.96), and (3.09), respectively. This result indicates a degree of satisfaction above the average level. Only one performance element (control of mechanical and natural ventilation levels) recorded a mean value of (2.57), revealing a level of satisfaction less than moderate. However, the overall indoor air quality reached an average value (2.87), demonstrating that students were satisfied.

The respondents’ rates of satisfaction for the five functional performance elements are discussed herein as follows.

Ten performance elements were evaluated in this category, namely, flexibility of the drawing board in terms of vertical adjustment, type of chair where you set, The table height, availability of personal storage, the width of walkways in the studio, willingness to stay for a long time in the studio, ease of movement in the studio, overall perception of studio’s interior design, ergonomic of furniture and flexibility of the studio to accommodate several functions. The mean response from the 52 respondents who completed the user satisfaction survey indicated that they were ‘Satisfied’ with the listed performance elements in this category, with an average satisfaction rate of 2.92, As shown in Table 4 and Figure 8.

There were sixteen performance elements in this category. These are the quality and presentation of wall finishes, the quality of floor finish in the studio, and the overall perception of interior finishes in the studio. These performance elements Average grades recorded (3.23), (3.05) and (2.98) respectively, revealing that the level of satisfaction was more than the moderate level. The overall quality of interior finishes was recorded at a rate value of (3.08). This outcome indicated that the respondents were “Satisfied” with the listed performance elements under This classification.

This category includes five performance elements, as listed in Table 4. Four of these elements (adequacy of help provided in cases of technical problems with IT equipment, the impact of architectural design studio education on perceptions, Need for a blank slate with a slide projector and screen suitable for the studio) had achieved a mean value of (2.61), (2.96), (2.65) and (3.03) respectively, revealing a degree of satisfaction closed to the moderate level. Only one performance element (Convenience of printers and plotters in the studio) recorded an average value of (1.82), which indicates the dissatisfaction expressed by the sample members towards this performance element. However, the overall quality of supporting services maintained a mean value of (2.61), demonstrating that students were satisfied, as illustrated in Table 4 and Figure 8.

The respondents’ rates of satisfaction for the two behavioral performance requirements are discussed herein as follows.

There were four performance elements in this category. Three of four performance elements related to this category (the collaboration of the students with their peers, contributing positively to group projects and Ability to personalize workspace within the studio) Average grades recorded of (3.26), (3.23) and (3.11) respectively, indicate that their satisfaction degree is Above moderate. For the fourth performance element (The adequacy of the brainstorming table (huddle) to accommodate group discussion), I recorded an average grade (2.55), representing a level of performance below the moderate level. The overall excellence of this category had achieved a mean value of (3.04), indicating that the respondents were ‘Satisfied’ with the listed performance elements under this category, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 9.

Two performance elements were evaluated in this category, namely, feeling for privacy while working and territoriality, with a recorded mean value of (3.13) and (3.03), respectively. This result indicated that the 52 respondents who completed the user satisfaction survey were “Satisfied” with the listed performance elements I, with an overall mean value of (3.09) as shown in Table 4 and Figure 9.

Fifteen participants, consisting of 10 students and 5 design studio instructors, took part in interviews as part of the post-occupancy evaluation study to gain a complete understanding of the architectural design studio environment. For user experience sampling, the researchers selected participants whose participation would yield a broad spectrum, including students from different studio knowledge backgrounds.

The interview format operated with a semi-structured methodology to investigate particular aspects of the studio facilities. Key questions included: What method do you use to assess studio thermal comfort? The studio lighting should assist both your work progress and creative process. The interior design and furnishings work well for your practical requirements. What obstacles exist when obtaining plotter access and printers from your institution?

Summary of Key Responses: The studio environment receives positive feedback for being thermally suitable, while the lighting levels enhance students’ attention and assist their creative processes. People universally identified these aspects as favorable elements. The participants approved of both the comfortable furniture design and its quality standards, which added to the arrangement’s positive workplace atmosphere. Most participants reported regarding supporting services as a major productivity obstacle because the supply of plotters and printers remained insufficient. Students working under time pressures pointed out this problem as their main issue.

An indicative assessment of the indoor environment was carried out in a representative sample of architectural design studios at Onaizah Colleges, Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The study has determined the rate of satisfaction obtained for the identified 45 performance elements. The degree of satisfaction was measured using a questionnaire, where architectural design studio users provided feedback on the built environment by rating their satisfaction across the identified performance elements. The findings obtained from the study showed variable degrees of satisfaction across the technical, functional and behavioral performance elements.

Regarding technical performance elements, the overall satisfaction rate of thermal comfort was 2.98 as shown in Figure 10, which emphasized the satisfaction status of design studio rates. This finding is in line with previous research findings conducted by Elnaklah et al. (2023), Smitha et al. (2023), and Hassanain and Mohammed (2012). However, the findings contradict those of an earlier study conducted by El-Darwish and El-Gendy (2018), Ahmadi et al. (2016). It was also noticed that there is a slight difference among the four performance elements categorized under the thermal comfort category. Students generally liked the thermal environment yet mentioned that their comfort perception changed based on which seats they occupied. The need exists to modify both airflow systems and ventilation distribution across rooms. Research shows that keeping thermal comfort levels at their best helps students focus and be creative, so the next step should be to develop new cooling systems made specifically for architectural design studio spaces. An investigation needs to be conducted about how temperature fluctuations throughout the year influence user performance outcomes.

Figure 10. Shown the average mean for performance elements: Technical, functional, and behavioural performance indicators.

Although the average rating of Acoustic comfort was 2.7, denoting the satisfaction rate of design studio users, it was found that many students were dissatisfied with the level of noise generated from outside the studio. This outcome is consistent with previous research conducted by Benjamin and Alibaba (2019) and Building (2022), which pointed out that acoustic comfort in architectural design studios is very important to help students gain more knowledge and improve communication between students, instructors, and advisors. The interview participants mentioned external noises that disrupt their design focus, emphasizing the future need for soundproofing elements in studio structures; the discovered results confirm the urgency to use superior soundproofing technologies or establish audio recording spaces where external noises remain at a minimum. Future research should examine which acoustic solutions produce superior results regarding user satisfaction and productivity in such working spaces.

In the context of functional performance, studio interior design recorded an average rate of 2.92, as shown in Figure 10, which indicates the satisfaction of design studio users. This finding is in line with research conducted by Saifudin Mutaqi (2018), Kesseiba (2017), and Tu (2015) emphasizing the development of the working atmosphere in design studios to encourage students and improve their productivity. According to Shaqour and Abo Alela (2022), design characteristics or educational environments are crucial and affect student’s creativity. The inside space of the design studio should be more than just a box-shaped classroom to encourage students to work and inspire them when they feel stuck with concepts. They need enough area to accommodate their various activities during the long working hours, including interaction, discussion, and making models, and therefore, several features should be taken into account and incorporated within the internal design studio environments, such as a coffee corner, model-making zone, views more than walls and adequate furniture (Shaqour and Abo Alela, 2022) Students generally liked the thermal environment yet mentioned that their comfort perception changed based on which seats they occupied. The need exists to modify both airflow systems and ventilation distribution across rooms. Architectural studios need flexible interior designs that accommodate different activities, according to these research findings. Research should explore which particular interior components affect creative operational flow and learning effectiveness.

Regarding behavioral performance, the privacy performance element recorded mean scores of (3.13). This outcome is consistent with previous research conducted by Demirbas and Demirkan (2000), which indicated that students preferred being at their tables to achieve the accepted level of privacy. Interviews with students indicated that some preferred to be alone to work. From this interesting point, it is clear that even the majority of students preferred to be alone or in seclusion; in practice, they favored closeness with peers. The interview participants emphasized personal workspaces because they need them, yet proximity between colleagues leads to spontaneous collaboration and knowledge transfer, which demonstrates the requirement for privacy alongside group interaction possibilities; researchers discovered the requirement for a strike between privacy preservation and collaborative design studio participation in their study. To achieve effective control over individual privacy conflicts, professionals should invest in movable partitions and modular workstations. Additional investigations should examine the natural adjustments students make regarding privacy needs across different phases of their academic assignments.

In general, this study makes a significant contribution by assessing the performance of architectural design studios to fulfill the requirements and expectations of their users. Through a detailed post-occupancy evaluation (POE), this study provides valuable insights into aspects such as thermal comfort, visual comfort, and interior design, which are critical to supporting the productivity and wellbeing of students and faculty in these spaces. The research results present specific solutions that can enhance student learning environments in design studios by implementing strategies that improve comfort, noise control, accommodating flexibility and maintaining privacy.

The paper focuses on how the educational environment functions by performing a post-occupation evaluation (POE) study that evaluates architectural design studio facilities. Building performance assessment becomes possible through the investigation of occupant perceptions and satisfaction levels and their provided feedback. The data showed that architectural design studio users displayed overall satisfaction regarding performance aspects, although acoustic comfort and IT facility availability needed improvements. The findings show that user dissatisfaction regarding external noise and lacking IT facilities reveal potential areas where improvement measures can be developed.

The main achievement of this work involves creating a systematic multi-dimensional assessment framework for the needs of architectural design studios. The research established an integrated framework through technical, functional, and behavioral performance criteria to conduct complete assessments of creative spaces. The developed framework offers a guide for future evaluations and design enhancements in educational environments that are similar to the study site.

The authors performed this study as a single case analysis at Onaizah Colleges located in Saudi Arabia to create a deep understanding of architectural design studios as they operate. Through its targeted research approach, the study provides a deep analysis of particular environmental conditions and cultural influences together with institutional settings for architectural studio education. Consequently, it delivers important practical knowledge to related educational contexts. The usage of a unique population of students and faculty members in this study allows specific user feedback that directly reflects the natural experiences that happen in this unique academic environment. The research findings revealing insufficient IT resources and model-making materials as factors impacting satisfaction did not weaken the overall value of the developed POE framework. The framework demonstrates its practical value when it guides assessments of actionable problem areas alongside practical solutions for improvement.

Future research can use multiple institutions from different climate zones and cultural areas to extend the findings obtained from this study. By examining various institutions, the conclusions would become more valid for wider scenarios. Repetitive studies across time periods will enable a better understanding of changing user satisfaction rates and performance trends, thus helping institutions plan facility changes. Examining the impact of high-performance computers along with virtual reality setups in architectural education will provide a critical understanding of their benefits for education quality and creative abilities.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/ participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

ME: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. MM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing. SB: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing–original draft. MH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing–review and editing. MG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors confirm that the data applied in this study is primary data and were generated at the building materials laboratory of Kingdom University in Bahrain. They declare that this research was funded by Kingdom University, Kingdom of Bahrain, grant number KU – SRU - 2024 – 02.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmadi, R. T., Saiki, D., and Ellis, C. (2016). Post-occupancy evaluation of an academic building: lessons to learn. J. Appl. Sci. Arts 1 (2), 1–16. Available at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/jasa/vol1/iss2/4/.

Ahmed, H., Edwards, D. J., Lai, J. H. K., Roberts, C., Debrah, C., Owusu-Manu, D. G., et al. (2021). Post occupancy evaluation of school refurbishment projects: multiple case study in the UK. Buildings 11 (4), 169. doi:10.3390/buildings11040169

Al-Jokhadar, A., Alnusairat, S., Abuhashem, Y., and Soudi, Y. (2023a). The impact of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in design studios on the comfort and academic performance of architecture students. Buildings 13 (11), 2883. doi:10.3390/buildings13112883

Al-Jokhadar, A., Alnusairat, S., Abuhashem, Y., and Soudi, Y. (2023b). The impact of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in design studios on the comfort and academic performance of architecture students. Buildings 13 (11), 2883. doi:10.3390/buildings13112883

Al Rahhal Al Orabi, M. A., and Al-Gahtani, K. S. (2022). A framework of selecting building flooring finishing materials by using building information modeling (BIM). Adv. Civ. Eng. doi:10.1155/2022/8556714

Aydin, K., and Li, Z. (2019). Analysing the effects of thermal comfort and indoor air quality in design studios and classrooms on student performance Analysing the effects of thermal comfort and indoor air quality in design studios and classrooms on student performance,” doi:10.1088/1757-899X/609/4/042086

Benjamin, A. O., and Alibaba, H. Z. (2019). Achieving acoustic comfort in the architectural design of a lecture hall. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Eng. Res. 6 (2), 161–184. Available at: https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Achieving%20Acoustic%20Comfort-6958.pdf (Accessed: January 1, 2025).

Building, H. G. (2022). Visualization of acoustic comfort in an open-plan, high-performance glass building, 1–10.

Corluluoglu, G., and Karakaya, A. F. (2022). On the interaction between shared design studios and interior architecture students: a new spatial experience with extended reality for supporting place attachment. J. Des. Stud. 4 (spi2), 75–86. doi:10.46474/jds.1149634

Demirbas, O. O., and Demirkan, H. (2000). “Privacy dimensions: a case study in the interior architecture design studio privacy dimensions: a case study in the interior architecture,” doi:10.1006/jevp.1999.0148

El-Darwish, I. I., and El-Gendy, R. A. (2018). Post occupancy evaluation of thermal comfort in higher educational buildings in a hot arid climate. Alex. Eng. J. 57 (4), 3167–3177. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2017.11.008

Elnaklah, R., Ayyad, Y., Alnusairat, S., AlWaer, H., and AlShboul, A. (2023). A comparison of students’ thermal comfort and perceived learning performance between two types of university Halls: architecture design studios and ordinary lecture rooms during the heating season. Sustain 15 (2), 1142. doi:10.3390/su15021142

Emam, M., Taha, D., and ElSayad, Z. (2019). Collaborative pedagogy in architectural design studio: a case study in applying collaborative design. Alex. Eng. J. 58 (1), 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2018.03.005

Evans, G. W., and Cohen, S. (1987). Environmental stress, in Handbook of environmental psychology, Editors D. Stokols, and I. Altman, 1, 571–610. New York: Wiley. Available at: https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/psychology/stress-immunity-disease-lab/publications/environmentalstress/pdfs/evanscohenchap04.pdf.

ezz, M. S., and Elsayed, H. A. (2024). Enhancing assessment methods in architectural design studio: a proposal for criteria-based evaluation. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 0 (0), 0. doi:10.21608/eijest.2024.288152.1273

Fatma, A., Boualem, D., and Hemza, S. (2017). Post-occupancy assessment of thermal environment in classrooms. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 12 (5), 1233–1247. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1278286.pdf (Accessed: January 2, 2025).

Gad, J. Q. S. E., Nour, W. A., El Dawla, M. K., and Dawla, E. (2022). How does the interior design of learning spaces impact the students' health, behavior, and performance? J. Inter. Des. 12 (5), 1233–1247. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364334027_How_does_the_interior_design_of_learning_spaces_impact_the_students_health_behavior_and_performance (Accessed: January 5, 2025).

Hassanain, M. A. (2008). On the performance evaluation of sustainable student housing facilities. J. Facil. Manag. 6 (3), 212–225. doi:10.1108/14725960810885989

Hassanain, M. A., Alnuaimi, A. K., and Sanni-Anibire, M. O. (2018). Post occupancy evaluation of a flexible workplace facility in Saudi Arabia. J. Facil. Manag. 16 (2), 102–118. doi:10.1108/JFM-05-2017-0021

Hassanain, M. A., Alhaji Mohammed, M., and Cetin, M. (2012). A multi-phase systematic framework for performance appraisal of architectural design studio facilities. Facilities 30, 324–342. doi:10.1108/02632771211220112

Hassanain, M. A., Sanni-Anibire, M. O., Mahmoud, A. S., and Ahmed, W. (2020). Post-occupancy evaluation of research and academic laboratory facilities. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 38 (5), 797–810. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-12-2018-0097

Hesham, R. (2022). Impact of interior architecture of design studios on undergraduate students’ performance. J. Arts and Archit. Res. Stud. 3 (5), 103–120. doi:10.47436/jaars.2022.130701.1086

Idowu, O. (2020). Daylight for visual comfort and learning in architectural studios in modibbo adama university of technology, yola. Uyo, Nigeria: Faculty of Environmental Studies at the University of Uyo.

Iranmanesh, A., and Onur, Z. (2022). Generation gap, learning from the experience of compulsory remote architectural design studio. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 19 (1), 40. doi:10.1186/s41239-022-00345-7

Jahangiri, M., Baneshi, S., Saeedi Garagani, Z., Kamalinia, M., and Daneshmandi, H. (2018). Assessing the level of safety measures in university classrooms: a case study in a university in the southwest of Iran. J. Health Sci. Surveill. Syst. 6 (4), 160–164. Available at: https://jhsss.sums.ac.ir/article_46195.html.

Kamalipour, H., Kermani, Z. M., and Houshmandipanah, E. (2014). Collaborative design studio on trial: a conceptual framework in practice. Curr. Urban Stud. 02 (01), 1–12. doi:10.4236/cus.2014.21001

Kesseiba, K. (2017). Introducing creative space: architectural design studio for architecture students; challenges and aspirations. J. Adv. Soc. Sci. Humanit., 1–15. doi:10.15520/jassh38240

Lueth, P. L. (2008). The architectural design studio as a learning environment: a qualitative exploration of architecture design student learning experiences in design studios from first through final year. Ames, IA, USA: owa State University. Available at: https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e9491055-a743-4874-b677-7ab3a64bc0e4/content (Accessed: January 1, 2025).

Mahmoud, A. S., Sanni-Anibire, M. O., Hassanain, M. A., and Ahmed, W. (2019). Key performance indicators for the evaluation of academic and research laboratory facilities. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 37 (2), 208–230. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-08-2018-0066

Mandala, A. (2019). “Lighting quality in the architectural design studio case study: architecture design studio at Universitas katolik parahyangan, bandung, Indonesia lighting quality,” in The architectural design studio case study: architecture design studio at unive. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/238/1/012032

Mitkees, L., Heidarinejad, M., and Stephens, B. (2022). Numerical investigation of thermal comfort of a thermally active student desk (TASD) in a virtual domain of historic S.R. Crown Hall building. ASHRAE IBPSA-USA Build. Simul. Conf., 67–75. doi:10.26868/25746308.2022.simbuild2022_c008

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., and Chaves, W. A. (2019). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: a systematic review of the research. Environ. Educ. Res. 25 (6), 791–812. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

Obeidat, A., and Al-Share, R. (2012). Quality learning environments: design-studio classroom. Asian Cult. Hist. 4 (2), 165–174. doi:10.5539/ach.v4n2p165

Ozorhon, G., and Sarman, G. (2023). The architectural design studio: a case in the intersection of the conventional and the new 5, 295–312. doi:10.46474/jds.1394851

Phuong, N. H., Nguyen, L. D. L., Nguyen, V. H. M., Cuong, V. V., Tuan, T. M., and Tuan, P. A. (2023). A new approach in daylighting design for buildings. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 13 (4), 11344–11354. doi:10.48084/etasr.5798

W. F. E. Preiser (1988). Post-occupancy evaluation (New York, NY, USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold). Available at: https://archive.org/details/postoccupancyeva0000prei/page/n5/mode/2up?utm_source.

Puckett, K. (2022). Safety and security on campus: student perceptions and influence on enrollment. USA: East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN. Available at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/4103/([Accessed January 4, 2025).

Ranjbar, A. (2019). Analysing the effects of thermal comfort and indoor air quality in design studios and classrooms on student performance. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 609 (4), 042086. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/609/4/042086

Saifudin Mutaqi, A. (2018). Architecture studio learning: strategy to achieve architects competence. SHS Web Conf. 41, 04004. doi:10.1051/shsconf/20184104004

Sambe, N., and Korna, J. (2020). Anchor borrowers programme and rice production in kwande local government area, benue state, Nigeria. Mediterr. Publ. Res. Int. 11 (6), 45–64. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/43669176/ANCHOR_BORROWERS_PROGRAMME_AND_RICE_PRODUCTION_IN_KWANDE_LOCAL_GOVERNMENT_AREA_BENUE_STATE_NIGERIA.

Sedghikhanshir, A., Zhu, Y., Beck, M. R., and Jafari, A. (2022). The impact of visual stimuli and properties on restorative effect and human stress: a literature review. Buildings 12 (11), 1781. doi:10.3390/buildings12111781

Shaqour, E. N., and Abo Alela, A. H. (2022). Improving the architecture design studio internal environment at NUB. J. Adv. Eng. Trends 41 (2), 31–39. Available at: https://jaet.journals.ekb.eg/article_185351.html.

Smitha, K. D., Khairunnisa, G., Rahmasari, K., and Dewi, O. C. (2023). Post-occupancy evaluation of thermal comfort at studio classroom in hot and humid climate. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1267, 012032. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1267/1/012032

Tu, U. (2015). Factors influencing function and form decisions of interior architectural design studio students, 174, 1090–1098. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.799

Widiastuti, K., Susilo, M. J., and Nurfinaputri, H. S. (2020). How classroom design impacts for student learning comfort: architect perspective on designing classrooms. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 9 (3), 469–477. doi:10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20566

Keywords: post-occupancy evaluation, design studio, architecture, performance element, performance elements

Citation: Ezz MS, Mahdy MAF, Baharetha S, Hassanain MA and Gomaa MM (2025) Post occupancy evaluation of architectural design studio facilities. Front. Built Environ. 11:1549313. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2025.1549313

Received: 20 December 2024; Accepted: 12 February 2025;

Published: 07 March 2025.

Edited by:

Krushna Mahapatra, Linnaeus University, SwedenReviewed by:

Davide Lombardi, Xi’an Jiaotong - Liverpool University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Ezz, Mahdy, Baharetha, Hassanain and Gomaa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohamed Salah Ezz, ZHJtb2hhbWVkc2FsYWhAb2MuZWR1LnNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.