- Department of Architecture and Interior Design, College of Engineering, University of Bahrain, Sakhir, Bahrain

Research problem and purpose: Residents’ modifications in subsidized housing are a widespread phenomenon in Bahrain. Households begin to modify their allocated residential units as soon as they receive them, resulting in financial burdens and an aesthetic loss of the uniform physical appearance. This research aims to identify the issues leading to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units.

Materials and methods: Literature indicates that this phenomenon is closely related to resident behaviors. Thus, the study presents a conceptual framework that examines the similarities and differences in residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing. Accordingly, the study employed the qualitative approach and was conducted in two phases. The first phase investigated common resident behaviors through structured interviews with twelve experts involved in the modification process. The second phase used the case study strategy with three selected cases from the East Hidd housing project to examine the different behaviors related to residents’ lifestyles. It included on-site observations, plan analysis, and structured interviews with householders using the AIO approach.

Results: The findings revealed general and specific issues that lead to residents' modifications. The general issues represent common behaviors for most residents and are usually associated with the prior-occupancy stage. They include residents’ preference for simple modern designs with spacious living rooms and bedrooms, trendy modern materials, and large windows; residents’ need for sustainable housing units that incorporate all three aspects of sustainability, particularly the socio-cultural, which is related to factors like privacy, hospitality, and the aesthetics and distinction of houses; and the damages resulting from the improper practices of residents that mainly revolve around excluding the experts and involving the unqualified in the modifications process. The specific issues represent families’ different behaviors and are usually associated with the post-occupancy stage. Those include residents’ need to modify their houses according to their lifestyles, which appeared in the guest room, the courtyard, and the interior divisions of the extended bedroom.

Conclusion: Considering both issues while designing future projects helps create flexible units that satisfy the needs of the majority while allowing for modifications at any time. This, in turn, helps reduce and streamline the modification process.

1 Introduction

Home is a haven for humans and a refuge from the outside world’s noise (Bachelard and Stilgoe, 1994). It is the place that one can escape to, where he finds safety, comfort, and isolation (Dayaratne and Kellett, 2008; Jacobson, 2010). Thus, a home must meet one’s needs, desires, and preferences (Jiwane, 2021). For this reason, the architect’s role is based in the first place on the desires and needs of individuals. But what if the design of the house is unified for a group of people? How can the architect make it suitable for all of them? It will undoubtedly be challenging to achieve since each resident has different desires and perceptions. This fully applies to housing projects designed for a large group of people. Although housing projects are typically designed to meet the requirements of residents, they usually do not fully accomplish their needs and preferences (Ahmed and Othman, 2015). Further, responsible authorities are unable to provide a precise unit design for a wide variety of residents with different needs (Jiwane, 2021). Accordingly, most residents make various modifications to their housing units according to their passions and desires, leading to financial burdens (Natakun and O’Brien, 2009; Ahmed and Othman, 2015).

The phenomenon of residents’ modifications is regular and widespread in housing units worldwide, including Bahrain, where residents begin to modify the designs of their housing units after receiving the keys (Saraiva et al., 2019). It is an inevitable continuous process influenced by sociocultural factors, evolving lifestyles and circumstances, human needs and behaviors, and economic and technological growth (Dayaratne and Kellett, 2008; Obeidat et al., 2022; Ozer and Jacoby, 2022). This means that this phenomenon cannot be stopped because every family has different needs, and a typical design cannot satisfy everyone’s requirements (Jiwane, 2021). However, the modifications can be either reduced or facilitated in future projects (Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero, 2022). Besides, studying the similarities and differences of subsidized housing designs is beneficial and aids in improving housing regulations (Ozer and Jacoby, 2022).

Despite the prevalence of this phenomenon, limited studies on residents’ modifications in subsidized housing have been conducted in Bahrain. Furthermore, while the literature indicates a strong link between this phenomenon and residents’ behaviors (Salman, 2016; Mahmood and Hussain, 2018; Sunarti et al., 2019; Aryani and Jen-tu, 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022), few studies have addressed residents’ common behaviors during the modification process. Aside from that, relatively few researchers have examined the relationship between residents’ diverse lifestyles and their modifications in subsidized housing. Consequently, this research aims to fill these gaps as a critical step in identifying the issues leading to modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing. This, in turn, contributes to improving the design of future housing units as it reveals the preferences and motivations of Bahraini residents in subsidized housing. It also contributes to reducing the modifications and violations. Besides, it aids in exploring the patterns of residents’ modifications that assist in determining the particular needs of residents and setting guidelines for the design of future projects. In addition, this research is occasionally and regionally necessary since technology, social, and cultural factors impact residents’ behaviors and lifestyles (Dayaratne and Kellett, 2008; Duffy, 2009; Ozer and Jacoby, 2022).

This paper is part of a broader, ongoing study for a master’s thesis that aims to identify the issues leading to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units. It focuses on the findings of 12 expert interviews and three case studies, whereas the master thesis expands on the research and includes a sample size of 20 experts and six case studies. Thus, the preliminary results are presented to a wider audience in this paper. In contrast, the master thesis presents a more thorough examination and comprehensive discussion. The study objectives are as follows:

• Determining residents’ common behaviors in Bahraini subsidized housing units.

• Analyzing the patterns of residents’ modifications.

• Studying the relationship between residents’ modifications and lifestyles.

These objectives seek to answer the research question: What issues lead to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units?

2 Literature review

2.1 Background

A subsidized housing project is a local government-provided program that consists of residential units for low-income residents (Freeman and Botein, 2002). The term ‘Subsidized housing’ is inclusive as it encompasses a variety of housing that is financially subsidized and granted by the local housing authorities (Ozer and Jacoby, 2022). Providing those housing projects is essential for societies because they significantly contribute to offering suitable accommodation and public services for low-income households (Drews, 1983). Subsidized housing projects also contribute to developing social and economic segments (Keith et al., 2011). This is owing to the massive scale of these projects and the use of standard designs, which reduces construction costs (Ozer and Jacoby, 2022). Subsidized housing units are generally small and consist of two or three floors (Stoloff, 2019). They are provided with general needs and standard regulations (Reeves, 2005). Since these units follow standards and universal characteristics, their designs are typical Since these units follow standards and universal characteristics, their designs are typical (Salman, 2016). However, these standards differ from one country to another depending on the socio-cultural aspect (Ozer and Jacoby, 2022).

In Bahrain, the growing urbanization and overpopulation put severe stress on the Ministry of Housing (MoH) to accelerate the construction of housing projects and fulfill the current and future public demands (Al-Saffar, 2014). Consequently, the MoH has presented significant efforts in the housing sector by developing numerous housing programs in various locations across the country (Al-Khalifa, 2015). Thus, the Kingdom of Bahrain is considered one of the Arab Gulf countries with conspicuous success and prosperity in the housing sector due to its ability to accommodate rapid urbanization and residential development (Al-Saffar, 2014). Subsidized housing projects are among the fundamental policies of the MoH, which are accomplished either through extending existing cities or establishing entirely new ones (Al-Khalifa, 2015). The primary goal of those projects is to provide appropriate accommodations for low-income households (Al-Saffar, 2014; Al-Khalifa, 2015; Salman, 2016). Isa and Hamad towns, established between 1963 and 1984, are considered among the initial housing initiatives and significant achievements of the MoH (Hamouche, 2004; Al-Khalifa, 2015). Both of those housing developments provided residents with subsidized housing units and public services (Hamouche, 2004). Since then, the MoH has developed various housing projects in several regions throughout Bahrain (Al-Khalifa, 2015).

In addition to Isa and Hamad Towns, previous subsidized housing projects include Malkiya, Madinat Zayed, and Zallaq, while recent developments include East Hidd, East Sitra, Salmabad, and others. So, the literature indicates that subsidized housing is an urgent priority for societies since it offers suitable housing for low income families while also improving the social and economic sectors. It also shows that the housing units in these projects are characterized by unified designs and specifications, which drives residents to make various modifications.

2.2 Residents’ modifications in subsidized housing

The process of modifications in housing units can be described in several terms, including housing transformations, extensions, adjustments, and alterations (Aduwo et al., 2013). The alterations in this process have various ways, like modifying housing requirements or improving their livability (Mohit et al., 2010). In other words, the modifications could be major related to the structure of the house, or minor, such as changing the color of the rooms (Obeidat et al., 2022). In addition, these modifications differ according to their legislation and location. For this reason, researchers have described this process with different definitions. For example, Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero (2022) define it as occupants’ responses to unfulfilled needs in standard housing units. Moreover, Natakun and O’Brien, (2009) describe it as remodeling internal and external spaces through a set of changes to the design and structure of the house to meet the particular family needs while also reflecting their tastes and personalities. Similarly, Aduwo, Ibem and Opoko (2013) claims that this process refers to the adjustments that inhabitants make to the layout of their housing units to meet their evolving demands and preferences. So, the process of resident modification is a significant phenomenon that occurs in subsidized housing all around the world. Therefore, it is essential to review it from both local and international perspectives.

2.2.1 International perspective

Several international studies have discussed the issue of residents’ modifications in subsidized housing units. For example, Jiwane (2021) conducted a survey to investigate occupants’ opinions and satisfaction with a housing project in Kanhapur village in India. The findings of this study show that dwellings were modified and altered by the occupants because they didn’t meet their demands. Another study by Tipple (1999) examined the housing transformation in four different countries: Egypt, Bangladesh, Ghana, and Zimbabwe. The results clearly show that the selected case studies have a common issue of not having enough rooms for the residents, and the plot size is small, which led them to extend the space. The results further show that many new owners of subsidized housing units will expand their living spaces to make their homes more suitable for their lifestyles.

In addition, Natakun and O’Brien, (2009) investigated the common modifications made in one of the housing projects in Bangkok by analyzing the architectural plans and conducting interviews with its residents. The findings indicate that residents modified their homes by following common patterns, such as extending the front and back patios, living rooms, and roofs. The results also imply that the modifications made by residents reflect their preferences and emotional needs.

2.2.2 Local perspective

The phenomenon of residents modifications has been discussed in some local research. Salman (2016) elaborates on this indicating that Bahraini residents adjust their housing units as soon as they move in to meet their requirements and reflect their identities. Salman attributes this to the typical layout of housing units that do not suit the different tastes of inhabitants. Moreover, Alkhenaizi (2018) claims that numerous households in Bahrain expand their houses to provide accommodations for their adults.

Even though this phenomenon is prevalent in subsidized housing in Bahrain, few studies have been conducted on it. One of the studies was conducted by Saraiva, Serra and Furtado (2017) who analyzed and compared the spatial configurations of traditional and subsidized housing in Bahrain. According to Saraiva, Serra and Furtado (2017), analysis indicates that gender segregation, one of the fundamental social values of the Bahraini society, is missing in the new subsidized housing. Furthermore, Saraiva, Serra and Furtado (2019) demonstrate that several modifications were made to the units’ layouts of the Samaheej project, including structural transformations, connecting the setbacks with the indoor and extending spaces. The study also confirms that when residents receive their houses, they immediately modify the functional distribution of spaces, structure, and style.

So, the international and local reviews show that residents’ modifications differ from one region to another. This implies that the process of modifications in subsidized housing is firmly based on residents’ behaviors.

2.3 Residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing

Subsidized housing residents make various modifications to their units based on specific preferences. For example, they modify their dwellings to enhance their living conditions while also meeting the emerging demands of their family members (Salim, 1998). They also aspire to provide additional spaces that satisfy their housing requirements and activities (Aduwo et al., 2013). Furthermore, housing transformations enable residents to personalize their homes to meet their desires and expectations (Mohit et al., 2010). Thus, residents’ needs and requirements are linked to several aspects. Accordingly, these aspects shape residents’ behaviors, which, in turn, affect the design of subsidized housing units. Obeidat et al. (2022), for instance, argue that the alterations made to housing units are attributed to the spatial behaviors of residents. Similarly, Sunarti et al. (2019) found that occupants’ changing behavior led to a transformation in low-income housing. Mahmood and Hussain (2018) support the same point, affirming that adjustments to physical housing spaces reflect the inhabitants’ behaviors. This indicates that occupants’ behaviors play a fundamental role in the process of modifications in subsidized housing. Therefore, it’s essential to study the aspects associated with residents’ behaviors and their influence on the design of housing units (Obeidat et al., 2022). The literature discusses the following aspects:

2.3.1 Motivational factors behind residents’ modifications

Studies have discussed several factors influencing residents’ behaviors and practices in subsidized housing. One of these essential aspects is socio-cultural. House designs and functions express cultural and social principles and concepts (Lawrence, 2019). Indeed, families evaluate housing conditions based on the extent to which family and cultural norms are employed (Morris and Winter, 1975). Not only that, if the housing does not meet those standards, it frequently leads to residents’ dissatisfaction (Morris and Winter, 1975). Ozer and Jacoby (2022) have found that sociocultural norms fundamentally influence housing designs and standards. Besides, they also emphasize that sociocultural norms determine the differences in requirements for subsidized housing designs. Furthermore, Obeidat, Abed and Gharaibeh (2022) have discussed the significance of privacy as a basis for modifying public housing design. They confirm that the modifications made to housing designs are based on sociocultural norms.

On the other hand, economic development and surrounding circumstances influence residents’ behaviors, which are reflected in subsidized housing modifications. For example, Aduwo, Ibem and Opoko (2013) indicate that various interconnected factors, including socioeconomic trigger housing alterations. Besides, Al-Saffar (2014) argues about the impact of the developing economy on the living standards of Bahrain residents. Sunarti, Syahbana and Manaf (2019) agree about the same view, claiming that economic status impacts the transformation of housing units. Ozer and Jacoby (2022) also support this, demonstrating that the COVID-19 pandemic has generated new residential demands and aspirations. In addition, Alkhenaizi (2018) has discussed how Bahraini residents’ behaviors have changed due to globalization. According to Alkhenaizi (2018), many households currently live in modest, modern-style homes rather than the larger ones that used to house generation upon generation. Similarly, El-Haddad (2003) has discussed the same subject in GCC countries, indicating that households migrated away from courtyard houses and are moving towards contemporary ones that encourage individual expression.

This means that residents have particular housing preferences over time. It also indicates that residents’ modifications in subsidized housing reflect those preferences. For this reason, designers and developers must be conscious of consumers’ changing demands and preferences and stay current with the recent trends in housing designs (Lee, Carucci Goss and Beamish, 2007; Wardhani et al., 2020). Thus, housing modifications keep changing over time, resulting in new trends that necessitate ongoing research (Nwankwo et al., 2014).

So, investigating residents’ common modifications that reflect their housing preferences and the reasons behind them provide a comprehensive understanding of the major issues driving residents’ modifications in housing units. Several studies have discussed those concepts. For instance, Nwankwo et al. (2014) investigated the nature of modifications made by most residents and the reasons behind them. Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero (2022) also surveyed the design factors needed for future housing projects by examining the nature of residents’ post-occupancy modifications. Similarly, a study by Obeidat, Abed and Gharaibeh (2022) was conducted to determine transformation forms for a public housing project.

2.3.2 Implications of residents’ modifications

While modifications to housing units increase residents’ satisfaction, they negatively impact the building’s efficiency and sustainability (Aduwo et al., 2013; Ahmed and Othman, 2015). This occurs due to residents’ incorrect behaviors and habits and improper practices during the modification process, triggering numerous problems and risks. Makachia (2005) investigated the transformations of a Nairobi city housing project and discovered that they influenced the aesthetic aspect. Landman has further found that the modifications created shambles, reduced the intended convenience and privacy, decreased interior ventilation for the interiors, and limited leisure and social spaces. Moreover, Aduwo, Ibem and Opoko (2013) propose developing a basic housing scheme that would allow residents to modify their housing units in an organized and thoughtful way while minimizing negative consequences. For this reason, Abdellatif and Othman, (2006) believe it is essential to pinpoint flaws and mistakes in residents’ modifications in low-income housing projects to prevent duplicating them and enhancing their quality in subsequent projects. Furthermore, Abdellatif and Othman, (2006) conducted a study on a low-income housing project in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, investigating the mistakes and negative impacts of residents’ modifications. The findings of this study have revealed that these mistakes resulted either from wrong design decisions or construction flaws caused by the residents through the modification process.

This issue also exists in subsidized housing projects in Bahrain. There have been several infractions of building modifications in housing projects, including wrong engineering practices that resulted in cracks in the walls of the units, water leaks, and faulty electrical connections that may lead to fires (AlBilad, 2020). Many residents attempted to fix the illegal practices, but they encountered difficulties due to the seriousness of those infractions and the high financial cost (AlBilad, 2020). Besides, other residents also had difficulty obtaining building permits because they were not adhering to the regulations (AlBilad, 2020). This indicates that, these housing damages and negative implications of the modifications they made to their dwelling units result from the wrong behaviors and mistakes they made during that process (Abdellatif and Othman, 2006).

Thus, mistakes and illegal practices are considered part of the common wrong and risky behaviors many residents make during the modifications process in subsidized housing due to their scanty experience in this field. This emphasizes the importance of involving experts and engineers in the modification process, which many residents ignore (Nwankwo et al., 2014). As a result, experts, such as professional engineers and designers, must understand residents’ behaviors because their primary role is to serve and meet their needs. Therefore, the process of residents’ modifications, motivations, and consequences probably vary among nations (Aduwo et al., 2013). In other words, residents of subsidized housing in a particular region share common behaviors and practices. However, there are some differences in residents’ behaviors related to their lifestyles that experts must be aware of and account for in every modification they make, as they differ from one family to another and from one house to another.

2.3.3 Lifestyles and the AIO approach

The concept of lifestyle is usually employed in studies of users’ behaviors and preferences (Lee, Carucci Goss and Beamish, 2007). Scholars have heatedly debated and described this concept in a variety of ways. For instance, Plummer (1974) described it as a way of life that deals with many issues intimately connected to individuals’ attitudes in their daily life and work. Reichman (1977) considered it an individual’s behavioral reaction to socioeconomic disparities. Similarly, Veal (1993) defined it as a distinct pattern reflecting interpersonal or social behavior. Furthermore, Jensen (2009) believed that lifestyle should not be viewed as a fixed thing because it is associated with mutable habits, implying that lifestyle changes with time. This indicates that lifestyle research is critical in understanding users’ behaviors.

Recent studies focus on lifestyles as a representation (Aduwo et al., 2013) of behavioral orientations and patterns (Zhao and Lyu, 2022). This is reflected in residents’ modifications to their units, resulting in various design patterns. Consequently, this suggests a relationship between residents’ modifications in housing units and their lifestyles. According to Aduwo, Ibem and Opoko (2013), residents modify their housing dwellings because they do not meet their demands and lifestyles. Besides, Mirmoghtadaee (2009) highlights the link between the modifications to housing forms and residents’ lifestyles, indicating that the components of the residential units represent the dominant lifestyle based on sociocultural attributes. Mirmoghtadaee (2009) further emphasizes that residents alter their environments to suit their needs and lifestyles.

Diverse variables can influence users’ lifestyles, including income, fortune, age, socioeconomic factors, material status, presence of children, place, and interests (Beamish, Carucci Goss and Emmel, 2001). The AIO approach is a measurement tool developed to study users’ lifestyles by examining those variables (Zhao and Lyu, 2022). It was first devised by Wells and Tigert (1971), focusing on three dimensions: users’ activities, interests, and opinions. These dimensions are associated with how people utilize their leisure time, their areas of interest, and their perspectives (Zhao and Lyu, 2022). Later, Plummer (1974) expanded the AIO approach by including demographics. According to Plummer, demographic is related to several characteristics, including age, family size, and occupation. As a result, the AIO approach has four dimensions linked to specific aspects.

2.4 Sustainability and subsidized housing

Sustainability is one of the most significant issues of the current time in the architectural field. It’s not merely a trend but a massive step toward healthier environments and better lifestyles (El-Ghonaimy, 2010; Abouelela, 2021). It’s a development that addresses the demands of both current and future generations (Kirkby et al., 1995). Sustainability incorporates crucial characteristics that most inhabitants strive for in their home designs combined in three pillars: Social, Economic, and Environment. Implementing those pillars in housing projects enhances their performance and satisfies residents’ needs and requirements (El-Ghonaimy, 2010; Ibrahim, 2020). In fact, subsidized housing standards integrate social, cultural, and economic aspects associated with residents’ common behaviors and lifestyles (Ravetz, 2001). Since these aspects are the pillars of sustainability, it implies a relationship between residents' modifications in subsidized housing and sustainability. In other words, residents of those houses behave according to sustainability aspects. Numerous studies have discussed the significance of sustainability for housing projects (Abdellatif and Othman, 2006; Talen and Koschinsky, 2011; Ibrahim, 2020; Atália et al., 2022).

2.5 Literature gaps

Based on the literature review, the process of residents’ modifications in subsidized housing is a common phenomenon locally and internationally and is mainly associated with residents’ behaviors. However, although the literature has extensively discussed residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing, few have addressed the similarities of these behaviors in the process of modifications. Besides, residents’ common mistakes and incorrect practices were not adequately highlighted despite the seriousness of the matter, its negative impacts on the buildings, and its widespread prevalence in subsidized housing worldwide and in Bahrain. Similarly, few studies have been conducted on the differences in behaviors related to the lifestyle of subsidized housing residents, notwithstanding the literature indicating an association between the modifications and lifestyle. Despite the AIO approach’s efficiency in studying and comprehending users’ lifestyles and behaviors (Zhao and Lyu, 2022), only a limited number of studies have applied it in housing research in general and residents’ modifications in particular.

Therefore, this study seeks to fill these gaps to answer the research question: what are the issues that lead to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units?

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Conceptual framework

The literature and recent studies like (Atália et al., 2022; Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero, 2022; Obeidat et al., 2022; Ozer and Jacoby, 2022; Zhao and Lyu, 2022) revolve around the following key points:

• Residents of the same region share similar behaviors and practices because they share the same customs and traditions. These common behaviors, however, can change over time and are influenced by technological advancement and economic growth.

• Residents’ common behaviors during the modification process in subsidized housing reflect their housing preferences toward recent trends, common motivations for the modifications, and residents’ common mistakes and incorrect practices.

• Residents’ behaviors differ in some ways due to the unique lifestyles of each family. This can be seen in the modifications that residents make to the design of their housing units based on their particular needs and perceptions, resulting in various design patterns.

• There is a relationship between residents’ modifications and sustainability aspects. These aspects represent the common motivators for residents to make modifications, and they vary by region. Therefore, it’s necessary to investigate which aspects are most required for housing residents.

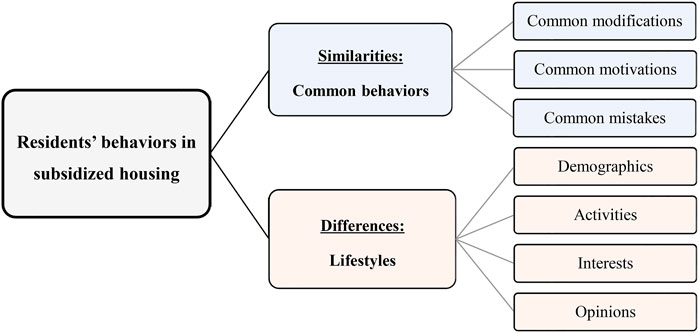

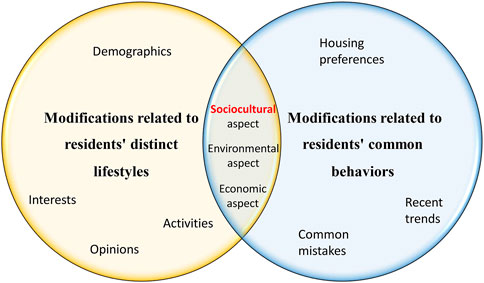

So, residents of subsidized housing in the same region have similarities and differences in their behaviors and practices in the modification process. On the one hand, similarities represent residents’ common behaviors and are associated with three categories: current common and repeated modifications reflecting most residents’ inclinations and preferences, common motivations behind modifications, and common improper practices. On the other hand, differences represent residents’ distinct lifestyles and are linked to four dimensions: Demographics, Activities, Interests, and Opinions. Accordingly, as an initial step toward answering the research question, which seeks to identify the issues that led to residents’ modifications, this study develops a conceptual framework that investigates the similarities and differences in residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing (Figure 1). Research investigations into this field are limited, as only a few studies have examined the similarities and differences in housing designs (Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero, 2022; Ozer and Jacoby, 2022).

3.2 Research methodology

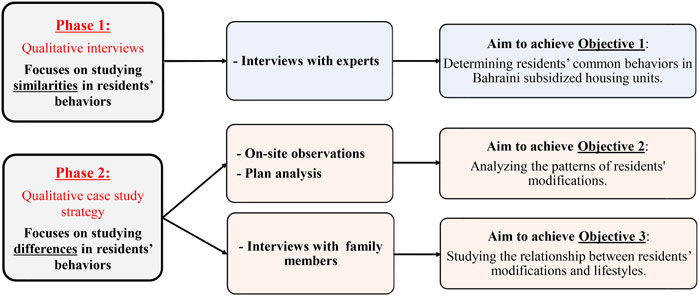

The research is ethnographic and exploratory; it explores the issues behind residents’ modifications in subsidized housing units in Bahrain. According to the conceptual framework described earlier, this necessitates gathering comprehensive and in-depth data about residents’ common behaviors and lifestyles. Therefore, the research employed a qualitative methodology using two primary methods: qualitative interviews and a case study strategy, which was carried out in two phases as follows:

• The first phase investigated the similarities in residents’ behaviors in Bahraini subsidized housing. Structured interviews were conducted with experts involved in the modification process from various engineering and interior design offices throughout Bahrain, including architects, interior designers, and civil engineers. The study used snowball sampling, a non-probability purposive sampling technique, to select the experts. Although the literature has emphasized the importance of experts in the processes of residents’ modifications, only a few research in the field have used them as a study sample (Abdellatif and Othman, 2006; Sunarti et al., 2019). Experts were asked about the most common modifications, motivations, and mistakes relating to the resident modifications process. During the interviews, the experts expressed their enthusiasm for the subject at hand, emphasizing its significance in light of the current prevalence of this phenomenon among Bahraini subsidized housing residents. This method, however, was insufficient for exploring all of the issues underlying the modifications because it only revealed issues related to residents’ common behaviors. Thus, a second, more focused phase of data collection was carried out to comprehend the issues concerning residents’ lifestyles.

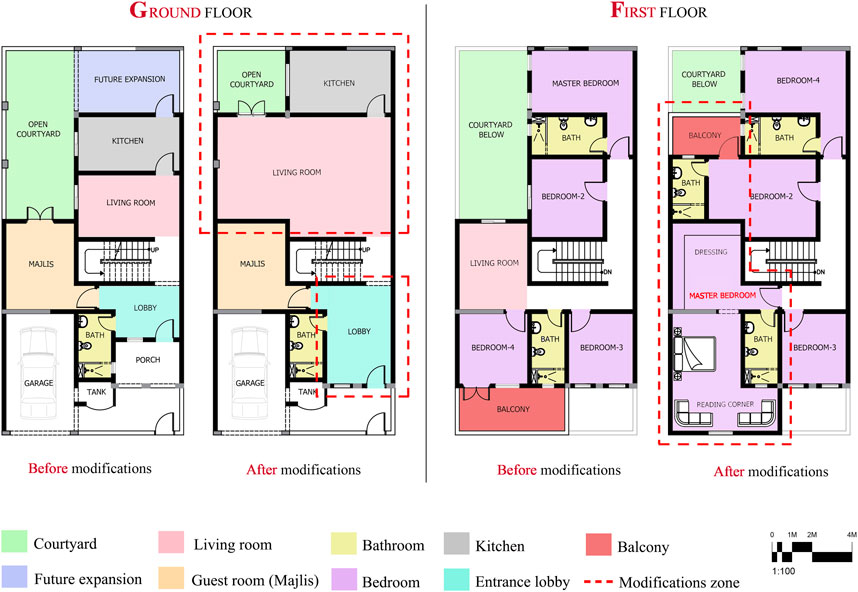

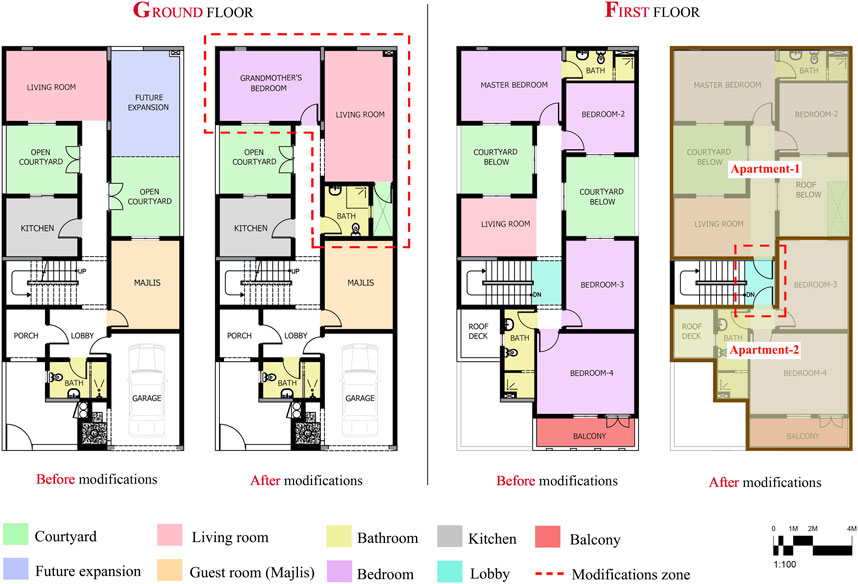

• The second phase used the case study strategy to examine the differences in residents’ behaviors in Bahraini subsidized housing. According to the data gathered during the first phase of expert interviews, the East Hidd project is one of the housing projects with the most resident modifications. Consequently, the sample was chosen from this project with the assistance of the interviewed experts; they were asked to propose cases for modified houses in the East Hidd project, and a list was created based on their suggestions. Then, three case studies were selected using a convenient sampling technique according to residents’ availability and readiness to participate in the research. Different research tools were used in the case study strategy. First, after obtaining permission from householders and getting their signatures on consent forms, on-site observations were conducted, which involved visiting the sites of the cases and documenting the observations with notes and photographs. It should be noted that 3D perspectives were used to document the modifications in private spaces like bedrooms where photography was not permitted. Several studies in the field have also used the observation tool (Jiwane, 2021; Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero, 2022; Obeidat et al., 2022). During site visits, original plans were utilized to help understand the modifications made. After that, both the original and modified plans of each case study were analyzed by drawing them in AutoCAD and coloring the altered zones to aid in identifying the different design patterns of residents’ modifications. Various studies have investigated the patterns of residents’ modifications and used the plan analysis tool (Aduwo et al., 2013; Aryani et al., 2015; Alkhenaizi, 2018; Obeidat et al., 2022). The last tool used in this phase was structured interviews with householders. For each case study, an interview was conducted with one of the householders to investigate the relationship between the family's lifestyle and the modifications they have made. The AIO approach, which has four dimensions—demographics, activities, interests, and opinions—was used as the interview instrument. A recent study emphasized the significance and efficacy of this approach in examining lifestyles (Zhao and Lyu, 2022). However, limited studies used it in housing research (Lee, Carucci Goss and Beamish, 2007; Shafiei et al., 2010).

The methods used in both phases were cautiously chosen to contribute to filling the gaps identified in the literature review. In the first phase, expert interviews were conducted to fill the gaps related to the scarcity of data collected from experts on this subject and the lack of discussions on residents’ mistakes during the amendment process. The second phase addressed the gap caused by the absence of lifestyle studies and the AIO approach in housing research. So, the research methodology contributed to collecting sufficient information about residents’ similar and different behaviors regarding the subsidized housing modification process. This, in turn, contributed to achieving the research objectives and providing clear and comprehensive answers to the research question (Figure 2). The methodological triangulation strategy used in data collection, which involved various data sources and methods, helped ensure the study’s validity and reliability. It also enabled a more robust and subtle interpretation of the findings and a more thorough comparison. The Research and Scientific Publications Committee gave its approval to the paper.

4 Results

4.1 Phase 1: interviews with experts

Findings of this phase revolved around three categories: Residents’ common modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing, the common motivations behind them, and the common mistakes that residents make in this process. So, based on experts’ responses, the data collected about each category were classified into different themes as follows:

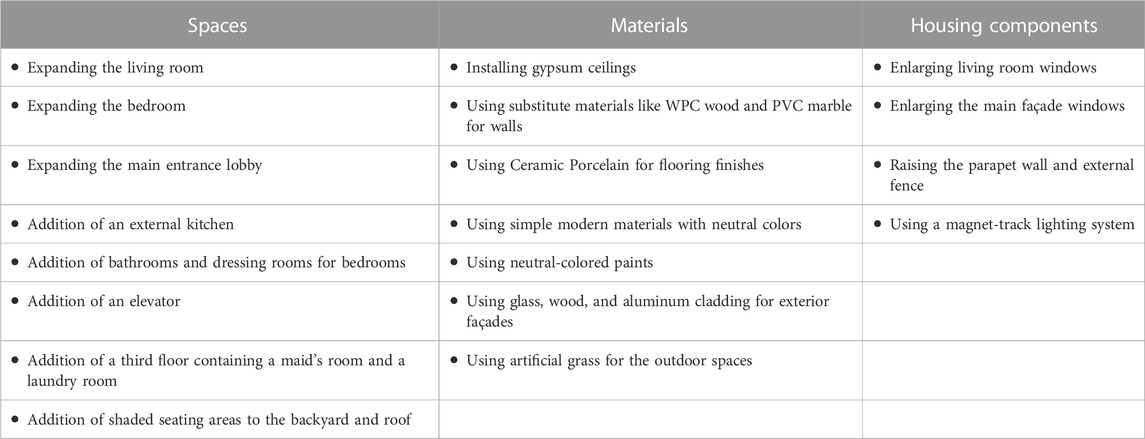

4.1.1 The common modifications

This category is related to the housing preferences of residents. It includes the following themes:

4.1.1.1 Spaces

Interviews revealed that the most common modifications residents make in Bahraini subsidized housing are related to space. According to interviewee #4, the spaces of housing units are insufficient for fulfilling the demands of family members. Besides, “small spaces do not fulfill the requirements of the eastern Bahraini family,” as interpreted by interviewee #6. Most interviewees also emphasized that the expansions were mainly made to the living rooms. This was confirmed by interviewee #2, claiming that “it is always requested to expand the living room hall to include a sitting area for female guests.”

In addition, the living room has been expanded in various ways. For example, some residents increase its size by combining it with the space of the guest room (Majlis). Another option, as demonstrated by interviewee #4, is to open the kitchen: “Clients frequently expand living rooms by removing walls and converting closed kitchens into open ones, resulting in a larger living room with a dining area.” Some residents also expand it by using a portion of the garage space, which is an illegal practice, as highlighted by interviewee #6. Residents also use the same technique to expand the guest room, which is another illegal practice. Interviewees also indicated that residents make bedroom expansions, primarily by removing the balconies from the master rooms and using their spaces, as explained by interviewee #1. Moreover, extensions may also include the house’s main entrance lobby because “it reflects the taste of the households,” as argued by interviewee #4.

Furthermore, not only extensions but additions are also among the modifications associated with spaces. As evidenced by the interviews, one of the essential additions for the residents is the addition of an external kitchen. Interviewee #2 emphasized, “An exterior kitchen is always necessary to isolate the odors from the rest of the house.” Likewise, interviewee #6 added, “The outdoor kitchen is essential in eastern homes because families use it daily for cooking.” Additions may also include bathrooms and dressing rooms for first-floor bedrooms. This was emphasized by most of the interviewees, including interviewee #3, who stated, “Some customers desire more bedrooms and individual bathrooms for every room.” Besides, specifying a space for the elevator is also among the recent common modifications, as highlighted by interviewee #4, “Most of those who build a third floor consider adding an elevator.” In addition, most Bahraini residents need to add a third floor, as stated by the interviewees. Interviewee #4 confirmed this, “Most of the residents build a third floor, which usually contains the maid’s room and the laundry room.”

Besides that, interviews also revealed that residents use the outdoor spaces to create private gardens and shaded seating areas. Interviewee #3 explained, “Even if it is a small area, residents believe it must be present.” Interviewee #1 also claimed that most residents prefer “adding shaded sitting areas or a pergola to the backyard.” Furthermore, interviewee #4 added, “Sometimes residents request to expand the duct to 4 m in length and 3 m in width so it can be used as an indoor garden.” Interviewee #4 further indicated that residents also request to create gardens on their units’ roofs and “usually prefer to include pergolas, planting areas, and a barbecue area.”

4.1.1.2 Materials

Modifying the materials, whether related to the interior design of housing units or the facades and outdoor spaces, is another modification performed by the residents. The interviews showed that the residents have certain common choices in this regard. Most residents, for example, prefer installing gypsum ceilings indoors because, according to interviewees, this material comes in various forms and sizes, including those resistant to temperatures and humidity, commonly used in kitchens. It is also durable and easy to install. Furthermore, most of the interviewees agreed that the substitute materials for the original ones are commonly used due to their lower cost and wide range of options. These include “WPC wood and PVC marble boards, which residents prefer to use mainly on the ground floor, particularly in the spaces that guests use, such as the main entrance, living rooms, and Majlis.”, claims interviewee #4. This also applies to the floorings where “Ceramic and Porcelain are preferred as finishing materials instead of pricy ones,” as indicated by interviewee #3. Interviews also demonstrated that residents incorporate contemporary materials like glass, wood, and aluminum into their exterior facades. In addition, for outdoor spaces, residents prefer using artificial grass instead of natural ones, which requires more maintenance, as emphasized by interviewee #10. Finally, regarding the colors, “Clients prefer neutral-colored paints,” according to interviewee #11.

4.1.1.3 Housing components

Interviews indicated that there are common modifications related to housing components. They include enlarging the sizes of the living room windows facing the backyard. They also include expanding the windows on the main façade, which is illegal. Besides, interviewees confirmed that some residents raised the height of the parapet wall, and others increased the height of the external fence to obtain privacy. Not only that, but some residents also “add a shed to the living windows overlooking the backyard to provide privacy,” as added by interviewee #12. Regarding lighting systems, interviewees agreed that residents have specific preferences mostly related to modern and trendy styles and techniques. According to interviewee #12, “There is an increasing demand for installing the magnet-track lighting system in subsidized housing units.” Residents also prefer “adding hidden lighting to the ceiling,” as claimed by interviewee #1.

So, residents’ common modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units revolve around three themes summarized in Table 1.

4.1.2 The common motivations

This category is related to the dominant reasons behind residents’ modifications. It includes the following themes:

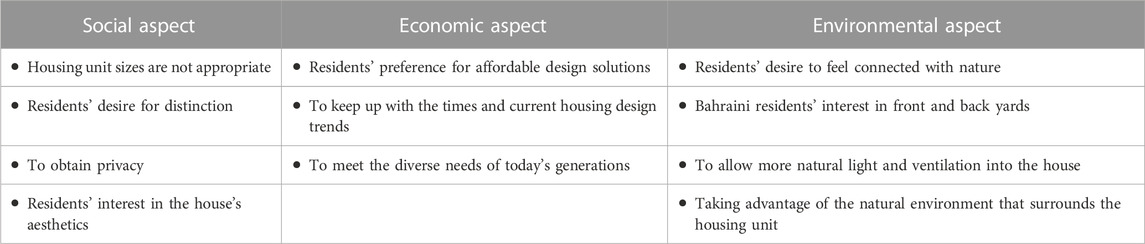

4.1.2.1 Social aspect

The interviews showed that residents made many modifications based on the social aspect. For example, most of the residents made expansions in their housing units because their sizes do not accommodate the needs of the residents and the number of family members. This was confirmed by interviewee #4: “Since the Bahraini family gathers every weekend, most families require a larger living room that overlaps with the dining room rather than isolating each space separately.” Another motivation for residents’ modifications is related to the future circumstances of family members. Interviewee #2 also explained this point, “Indeed … one of the children will eventually settle in the family home, and he will, of course, require some privacy.”

In addition, most interviewees also emphasized that residents usually modify the façade of their housing units. According to interviewee #3, residents modify their façades “due to its rigidity and monotony.” Moreover, interviewee #1 highlighted that residents modify facades “because they are typical in style and formation due to mass production, which creates confusion in finding the house’s location or describing its’ address.” Interviews also clarified that privacy is another motivating factor behind the modifications. The privacy modifications, according to interviewee #10, include designating one guest room for men and another for women. Interviewee #10 further demonstrated that each family member needs to have their own space. Furthermore, interviewees argued that residents are concerned about the aesthetics of their homes and how guests perceive them, and they consider it a critical reason for making modifications. Interviewee #4 claimed, “Residents usually modify the ground floor to make it suitable for guests only.” Interviewee #11 explained, “Sometimes modifications are just luxuries and not a real need.”

4.1.2.2 Economic aspect

As interviews showed, the economic aspect plays an integral role in the modification process, and it’s one of the fundamental concerns for Bahraini residents in subsidized housing. For example, most residents seek cheap, high-quality materials requiring less maintenance, as most interviewees assured. Besides, residents’ modifications are based on the needs of future generations as well as changing circumstances. According to interviewee #2, “the period of COVID-19 had a significant effect on the client’s needs.” This is exemplified by recent additions such as the gym and gaming room, as stated by interviewee #2. Other related modifications to this aspect include those aimed at saving energy in the home. Many residents, for instance, “tend to reduce the number of lights in the ceiling while still providing adequate illumination, resulting in lower lighting costs,” as affirmed by interviewee #4.

4.1.2.3 Environmental aspect

As the interviews revealed, many of the modifications made by residents in their housing units are related to the environmental aspect. For example, as agreed by most interviewees, one of the most common requests is to enlarge the windows and doors to allow as much natural light and ventilation as possible to enter the interior spaces. Besides, interviewee #10 claimed that “Residents frequently include trees in their homes because they reduce heat.” Furthermore, interviewees indicated that Bahraini residents pay close attention to their home’s front and backyards, designing them uniquely with natural elements like plants and waterfalls. They also noted that residents frequently install larger windows overlooking these courtyards, making them feel more connected to nature, especially when waterfalls and plants are added. According to interviewee #1, “Some residents would have the desire to make glass facades overlooking the back garden.” Moreover, as demonstrated by the interviews, modifications are influenced by the surroundings’ geography. This was noticeable in the East Hidd subsidized housing project, where most residents “prefer to take advantage of the sea view by installing larger windows,” as claimed by interviewee #4.

So, the common motivations behind residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units revolve around three themes summarized in Table 2.

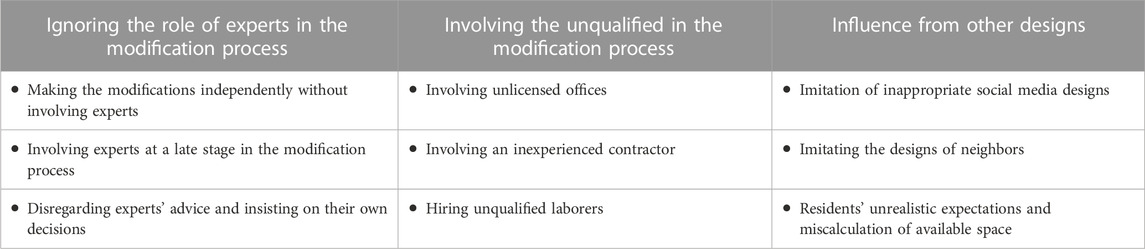

4.1.3 The common mistakes

This category is related to residents’ incorrect practices in the process of modifications. It includes the following themes:

4.1.3.1 Ignoring the role of experts in the modification process

Interviews revealed that residents make numerous wrong decisions during the process of modifications. Among these decisions is excluding the experts. According to the interviewees, most residents disregard experts’ advice and insist on their own choices. Besides, they neglect to involve them in the process of modifications. This includes two cases: residents either make the adjustments independently or involve experts late in the process. This behavior results in many adverse effects. For example, “In the long run, not consulting a specialized office may result in structural flaws in these modifications.” claimed interviewee #2. Besides, interviewee #6 highlighted that residents might “incorrectly install thermal, moisture, or water insulation materials.” Furthermore, interviewee #6 also added, “These mistakes result in high electricity and consequences such as fires and trespassing on neighboring property.” Not only that, but residents may also “remove a wall without realizing it is a bearer or direct support for the house … this has an impact on the building’s safety in the future”, claimed interviewee #5. Due to that, “most designers realize they need to make considerable changes to correct what the client has done. For example, they may need to break a wall, change the paint, or add new electrical outlets, increasing the costs and efforts and delaying the project delivery”, as explained by interviewee #4. Thus, interviewees agreed that involving experts at earlier stage help avoid these mistakes and violations and choosing the best solutions based on the client’s needs and budgets.

4.1.3.2 Involving the unqualified in the modification process

Interviews revealed that a wide range of residents hire an unlicensed and inexperienced designers or contractors, which worsens and exacerbate the issue of modifications. The interviewers focused on the negative impacts and risks associated with residents’ wrong behaviors. For example, interviewee #1 claimed, “it results in residents receiving a building violation, which prompts them to return to an engineering office to obtain a building permit without a breach, and the process is repeated.” Besides, interviewee #1 further added, “Spending a lot of money on expansions and re-planning, which results in a budget deficit and residents will not have enough money for furnishing.” Interviewee #4 also explained, “An unqualified contractor may misinterpret the design or start work without adequate detailed construction plans, follow-ups, or supervisory visits. As a result, many mistakes are made while making the modifications, such as installing the floors incorrectly.”

4.1.3.3 Influence from other designs

Interviews revealed that this is one of the most prevalent behaviors in today’s society, and social media has a big part in enabling it. This mistake occurs when residents copy designs from their neighbors or images found online. According to interviewee #2, “Due to the use of the Internet and social media, many ideas haunt the client’s mind, which makes him unable to determine his priorities in choosing the design.” Interviewee #6 presented an example of this case, stating that “if the neighbor builds something inside his house, the inhabitant imitates him or seeks the assistance of the same contractor in charge of the construction, whether he is experienced or not.” The main reason behind these mistakes is that “Clients have high expectations for housing units in terms of the components used or the final design, which are out of proportion to the available space,” as indicated by interviewee #9.

So, residents’ common mistakes in the modification process in Bahraini subsidized housing units revolve around three themes summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3. The common mistakes made by residents during the modification process of Bahraini subsidized housing units.

4.2 Phase 2: case studies

The East Hidd is one of Bahrain’s most recent subsidized housing developments. It’s located in a new town in Muharraq Governorate. The project is expected to contain 2,827 housing units when it is finally completed (MoH, 2023). The Ministry of Housing offered different housing units, each with a slightly different layout. The areas of those units range from 240.85 to 256.337 square meters, and they all have two floors. Three case studies were chosen from this project to study the relationship between residents’ modifications and lifestyles. The data collected in each case study was classified according to lifestyle dimensions and summarized as follows:

4.2.1 Case study 1

4.2.1.1 Demographics

The house is inhabited by six members: the homeowner and his wife, two sons, one daughter, and a maid. The couple is 38 and 36 years old, their sons are 17 and 6, and their daughter is 13. Their habitation period is 1 year and a half.

4.2.1.2 Activities

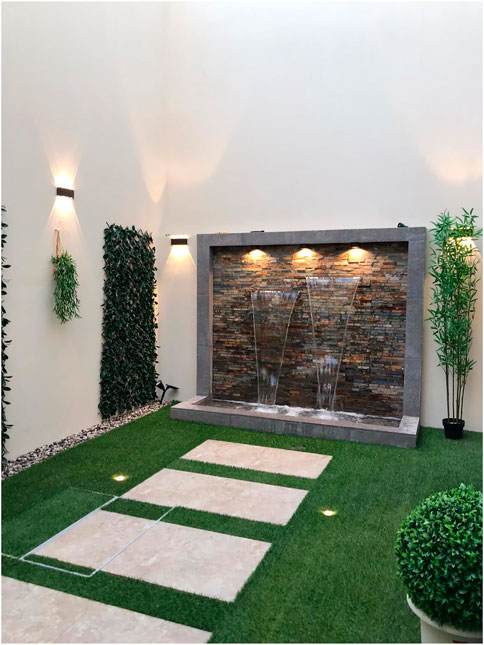

One of the most significant activities for homeowners is having breakfast and lunch with their children because of the nature of their work, which requires them to spend most of their time outside the home. Due to this, they reduced the size of the courtyard and added a dining space near the kitchen on the ground floor. As a result, they also downsized the bathroom and designed a washing zone to serve the dining area. The living room is another critical space where family gatherings take place every weekend, which was the motive behind extending it toward the space provided for future expansions (Figure 3). The children’s private tutors mostly use the guest room (Majlis) because it’s a quiet space apart from the rest of the house. Besides, the homeowner uses it for hosting his friends once a week. So, to maintain the house’s privacy, an external door was installed for the guest room, as explained by the interviewed householder. Additionally, the family members frequently use the courtyard’s outdoor seating area on the weekends during the months when the weather is agreeable, where they can relax, barbecue, and enjoy the view of the waterfall and the plants they have sown (Figure 4). They also use it for family gatherings, particularly during Ramadan. In addition, another activity preferred by the homeowners is the use of the sitting room in the first-floor bedroom, which they designed specifically for their needs by expanding its area and dividing it into two zones: one for the bed and the other for seating with a TV, or “a home cinema,” as the house owner described it (Figure 5).

4.2.1.3 Interests

The couple is concerned with the aesthetics of their home, which influences their selection of furniture, materials, colors, and finishes. Besides, because their budget is limited, they were looking for affordable and aesthetically pleasing solutions. However, they prioritize some preferences, even if expensive, such as the safest electrical sockets, floors, and furniture to ensure they last longer. As for the lighting, they provided a low-cost option that also looks beautiful because, for them, it is one of the items that can be easily replaced, regardless of its quality. The householder interviewed confirmed that he took special care of the entrance, hall, and Majlis because they are “the address of the house” where guests are welcomed. As a result, he employed high-priced and high-quality materials in these areas, such as foam and dyeing. The homeowners are also interested in home gardening, as they sow plants, roses, and fruit trees in the courtyard. They are also interested in nature, so they have installed an additional glass door in the living room facing the courtyard to allow more natural light and ventilation to enter the indoors and provide an aesthetic view.

4.2.1.4 Opinions

The interviewed householder asserted that he is delighted with all of the changes because he believes they have made the house better suited to the needs and desires of family members. He also noted that the modifications made the house look more beautiful in keeping with the modern style, indicating their interest in recent trends, as most subsidized housing residents prefer this style. However, the householder admits that he overspent on decoration and luxuries, saying, “I should have saved this amount for necessities before spending it on decoration.”

4.2.2 Case study 2

4.2.2.1 Demographics

The house is inhabited by four members: the homeowner and his wife, one son, and one daughter. The couple is 39 and 45 years old; their son is 15, and their daughter is 14. Their habitation period is 3 years.

4.2.2.2 Activities

The house owners spend most of their time at work while their children are at school. For this reason, the time they spend at home is for “meeting to dine,” as described by the interviewed householder. Thus, having a dedicated dining area is critical for them, so they expanded the living room to accommodate this need (Figure 6). Furthermore, the homeowners rarely have guests or family gatherings. Hence, they are unconcerned about the guest room and do not use it regularly; as the interviewed householder stated, “it would be better if the guest room’s space were combined with the living room in the future.” The householder also confirmed that family members frequently use the living room to gather and watch TV together on weekends or after work. In addition, cooking and baking are regular activities for the housewife, which is why the kitchen was expanded. Not only that, but the housewife also enjoys spending her free time reading stories and novels in a quiet area with a view of the outside, is exposed to sunlight, and is connected to nature. Therefore, the main bedroom was enlarged to accommodate this, and a sitting area was added, including a designated reading corner.

4.2.2.3 Interests

One of the elements that the homeowners are interested in is large windows that allow plenty of natural light and sunlight in. As a result, they enlarged the window and installed a glass door overlooking the courtyard to provide a stronger connection with nature (Figure 7). It is also important to them that the spaces are spacious, even if they do not have family gatherings, because this provides them with comfort when moving around, as described by the interviewed householder. They are also concerned with the aesthetic aspect and the quality, even if the cost is higher, so they removed the wall next to the staircase and replaced it with a golden-colored aluminum partition to provide an aesthetic to the living room (Figure 8). In addition, gypsum ceilings with concealed lighting were installed in most of the rooms. It is also critical for homeowners to achieve comfort in the home by customizing it to their preferences, even if it comes at a cost. For example, the housewife is interested in modern house designs that are more spacious and have large windows that connect to the outside. She is also interested in fashion and makeup and prefers having her own space in her bedroom. As a result, she considered these requirements when expanding her bedroom, which she describes as a separate apartment. Thus, the bedroom includes spaces for different functions: a seating area for reading and a dressing area with a makeup corner, precisely what the housewife desired. Since the daughter is also interested in fashion, just like the mother, her bedroom was expanded to accommodate this desire.

4.2.2.4 Opinions

The homeowners are not completely satisfied with the modifications because, for example, they discovered after experiencing the modified spaces that the guest room is underutilized. Furthermore, the interviewed householder confirmed that they wished to close off the area in front of the entrance door but could not do so because it is illegal. They also wished to replace the windows with larger ones. Since the homeowners do not benefit from the guest room and they rarely use it, they want to open it up to the living room in the future. Besides, after enlarging the living room, the area of the ground floor courtyard (garden) became relatively small, so one of their plans is to add a garden on the roof. They also intend to build an entire floor for the son when he is older. In the opinion of the homeowners, future housing projects should have more spacious interiors.

4.2.3 Case study 3

4.2.3.1 Demographics

The house is inhabited by six members: the homeowner and his wife, their son, their daughter, their grandmother, and their uncle. The couple is 31 and 36 years old, their son and daughter are 10 and 8, their grandmother is 70, and their uncle is 54. Their habitation period is 2 months.

4.2.3.2 Activities

One of the essential activities for homeowners is family gatherings on weekends. So, the homeowners took advantage of the space available for future expansion, constructing a living room for family gatherings instead of using the small existing one, according to the interviewed householder (Figure 9). They also used a portion of the courtyard space to construct a bathroom adjacent to the living room, with a ventilation space behind it. As the interviewed householder explained, “the living room is used not only for family gatherings but also for dining, and the children use it to play and study.” Accordingly, the homeowners expand the living room since it serves as the primary gathering and activity space (Figure 10). The guest room is typically used when male guests, such as friends of the husband or uncle, arrive while women sit in the newly built living room. The homeowners are very concerned with both gender segregation and privacy. As it is difficult for the grandmother to ascend to the first floor, the old living room was replaced with a bedroom for the grandmother. The old living room was also chosen as the grandmother’s bedroom because it faces the courtyard, allowing natural light to enter the room, which the grandmother values. Besides, the grandmother usually fries strong-smelling foods like fish in the courtyard. The house’s owners also divided the first-floor area into two sections by adding a door to each section, creating an apartment separate from the other (Figure 11). This is because one of the two sections is inhabited by the spouses and their children, while the other is being prepared for the uncle who is planning to marry and settle there.

4.2.3.3 Interests

One of the things that homeowners are interested in is connectivity with nature and space ventilation. For this reason, when they built the living room and bathroom, they were determined to leave a space from the courtyard for ventilation, as explained by the interviewed householder. The grandmother also values the courtyard because she is passionate about home gardening. Besides, homeowners are also interested in family gatherings, which take place every weekend, especially since the house is considered “the grandmother’s house, where the children and grandchildren gather,” as described by the interviewed householder. They also prefer practical home solutions that are both affordable and long-lasting, whether for materials, furniture, or finishes. They have no interest in the aesthetic aspect of the design as they think that selecting practical solutions is more crucial, especially in the living room, where they perform most of the activities. During the interview, the householder also confirmed, “The modifications are based on the needs and priorities of the family.” Privacy is at the top of their priorities, especially when men attend family gatherings and visits. So, the householder stated they would prefer an external door for the guest room.

4.2.3.4 Opinions

The house’s residents are pleased with all the modifications they have made because it meets their needs and provides leisure and comfort. According to the interviewed householder, “the space does not allow for more modifications, as any modification affects other spaces.” However, the homeowners intend to use a portion of the garage space in the future to construct a toilet for the guest room that will be used by male guests, particularly during visits and family gatherings. They also plan to widen the front internal entrance lobby of the house and build a maid’s room with a laundry room on the roof. The householder further emphasized the importance of incorporating natural lighting in all interior spaces of future housing units and increasing the size of the bedrooms and living rooms. The interviewee also believes that housing units should include a separate guest room with a toilet because “most Bahraini families require privacy while hosting guests, particularly non-relatives.”

5 Discussion

The research aimed to explore the issues leading to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing through two phases. The first phase focused on the issues related to residents’ common behaviors concerning the process of modifications through interviewing experts. Those are associated with three categories: Residents’ common modifications, motivations, and mistakes. Regarding the common modifications, findings showed that residents desire specific preferences and new trends in housing design before inhabitation. Those preferences are related to different themes, including particular space arrangements and sizes, materials and design techniques, and housing components, both internally and externally. The analysis demonstrated that these themes lean toward simple modern designs. This supports the claim of Taki and Alsheglawi (2022) that Bahrain is heading toward modern designs, which most residents prefer. This is evident in the spacious spaces that most residents prefer, as interviews revealed that space expansion is the most common modification among Bahraini subsidized housing residents. Besides, the interviews indicated that space expansion mostly appears in living rooms and can be achieved through various methods, such as utilizing kitchen space. This was also confirmed by Saraiva, Serra and Furtado (2019), who stated that expanding the living room is frequently accomplished by utilizing the kitchen space. As a result, most residents add an external kitchen, which is another common modification, as the findings indicated. Salman (2016) also highlighted this, indicating that modern residences must have exterior kitchens to avoid strong odors produced by Bahraini cuisines. Additionally, expanding bedrooms is one of the modifications that residents constantly make to accommodate additional functions. Moreover, residents’ preference for modern styles is also evident in their choices for sustainable modern-style materials and expansive glazed facades.

Regarding the common motivations, findings revealed that there are constant motivations behind the modifications represented in the three pillars of sustainability, particularly the sociocultural pillar. This reflects how strongly the Bahraini residents clung to their customs, traditions, culture, and values. This was evident in residents’ concern for privacy, hospitality, and family gatherings. This was also highlighted and discussed by other studies (Alkhenaizi, 2018; Saraiva et al., 2019; Obeidat et al., 2022). Regarding the common mistakes, findings indicated that most residents commit widespread mistakes before and during the modification process. These mistakes cause damages that exacerbate the modification process and make it more complicated. This was also noted by Abdellatif and Othman, (2006), who explained some of those mistakes and their associated obstacles. Therefore, to implement the modifications accurately and effectively, selecting experienced contractors in addition to qualified design offices is crucial before beginning the modification process. This will help clients understand building codes and violations, as well as the dangers of working alone without the assistance of specialists. Therefore, knowing these mistakes helps avoid them in future projects and reduces the modifications (Chukwuma-Uchegbu and Aliero, 2022).

The findings of the second phase demonstrate that differences in residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing related to their distinct lifestyles are strongly associated with the post-occupancy stage. In other words, many modifications are based on the lifestyle dimensions such as Demographics, Activities, Interests, and Opinions. For example, as demonstrated in the first case study, some residents may make specific modifications to meet the needs of an elderly family member. Some also intend to make substantial changes because their accommodation period was longer and revealed some issues with the modifications they made before occupancy, such as the fact that the modifications are not suitable for them, as evident in the second case study.

Furthermore, residents modify their dwellings to cater to their activities, which differ from one family to another because, as revealed by interviews with householders, residents’ activities are closely related to their working and leisure time, visitors, and family gatherings. For instance, in the first case study, the homeowners concentrated on having a private space to practice their activities and hobbies, which was represented by the sitting area in the bedroom and the courtyard; in the second case study, the focus was on the kitchen because the housewife cooks frequently; and in the third case study, the homeowners concentrated on the living room because the house is considered the family home, where family gatherings take place regularly. Moreover, in all three cases, residents modified their housing units to accommodate their various interests. In the first case study, residents were most interested in luxuries, aesthetics, and courtyard design; in the second, homeowners were interested in spacious spaces and contemporary style; and in the third, residents were most concerned with privacy and cost savings.

In addition, the interviewed householders reaffirmed their intention to make modifications in the future, either because they realized one of the changes they had made was inappropriate or to accommodate new circumstances and future events, such as the marriage of one of the family members, or creating space for recent activity. This is consistent with the argument of Jensen (2009), who indicates that lifestyle evolves over time. Residents also demonstrated the significance of personalization in design by enabling them to customize their surroundings to suit their preferences and reflect their personalities. This was also emphasized and discussed by (Tipple, 1999; Marcus, 2006).

This implies that many of the modifications made by residents are related to the lifestyles of families, as clarified by Aduwo, Ibem and Opoko (2013). These modifications vary because each family employs lifestyle dimensions based on priorities, resulting in different design patterns, as illustrated in Figures 3, 6, 9. In other words, this confirms and demonstrates the relationship between lifestyle and residents’ various modifications, which was also indicated by Mirmoghtadaee (2009). Furthermore, the design patterns analysis revealed that the various lifestyle modifications are concentrated in specific zones. This is evident in the three cases through the different design solutions and future plans for the guest rooms, courtyards, and interior divisions for the extended bedrooms. Accordingly, providing flexibility in these spaces is recommended, as it will allow for the various modifications that residents may make over time (Aryani and Jen-tu, 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022). Simultaneously, it was demonstrated that similar modifications were implemented in the case studies, such as expanding living rooms and allocating space for the dining table, extending bedrooms, and using oversized windows and glazed sliding doors overlooking the courtyard. Experts have also identified these modifications as among the most common in subsidized housing units, indicating their importance to residents. Besides, residents have a common desire for sustainability aspects; despite the differences in residents’ interests, they revolve around the three pillars of sustainability, particularly the socio-cultural aspect. This is consistent with experts’ responses about the common motivations behind residents’ modifications, implying that these aspects are considered motivators for residents to make general or specific modifications (Figure 12).

This is mainly prominent in the courtyard space in the three case studies. As shown in the patterns of residents’ modifications, all homeowners used the courtyard space to expand their living rooms. Simultaneously, a portion of the courtyard was left with a different size in each case based on the homeowners’ differing interests and priorities. According to the interviewed householders, they either need the courtyard to serve as a natural aesthetic view of the interior and a source of natural lighting and ventilation or to utilize its space for various activities. This emphasizes the importance of the courtyard for Bahraini residents. In agreement with this perspective, Lafi and Al-khalifa (2022) stated that the courtyard has considerable value for Bahraini residents because of its cultural, social, and environmental significance and its role in contributing to the privacy and sustainability of the house. This was further confirmed during the first phase of the research by interviewee #3, who pointed out that the presence of a courtyard in Bahraini residences is essential regardless of its size.

Therefore, after comparing and contrasting the behaviors of residents in Bahrain’s subsidized housing during the two phases, it was found that the issues that lead to residents’ modifications can be classified as follows:

• General issues represent the similarities of residents’ behaviors in subsidized housing and are usually associated with the prior-occupancy stage. These issues affect the majority of residents, and they include the following:

◦ Residents’ preference for simple modern designs with openness and spacious interiors. This was abundantly clear through the common modifications that most residents make, such as extending living rooms and bedrooms, using trendy modern materials and techniques, and installing large windows and glazed sliding doors overlooking the courtyard.

◦ Residents’ desire for sustainable housing units that consider social, cultural, economic, and environmental aspects—with the sociocultural part having the most significant influence on this process because it is affiliated with critical factors such as privacy, hospitality, and the aesthetics and distinction of houses—means that residents’ modifications are a complex process that necessitates a thorough investigation and comprehension of all of these aspects.

◦ Damages caused by residents’ common mistakes during the modification process, such as ignoring the consultation of the engineering office, hiring inexperienced workers, and being influenced by designs that do not meet their needs.

• Specific issues represent differences in the behaviors of subsidized housing residents and are usually associated with the post-occupancy stage. These issues relate to families’ distinct lifestyles, as demonstrated by the different modifications made or to be made to the guest room, courtyard, and interior divisions of the extended bedroom. They include the following:

◦ Residents’ need to modify the house based on demographic factors, including the number and ages of family members, marital status, and occupation period.

◦ Residents’ need to modify the house based on their activities, which include their routines, habits, hobbies, and time use. So, it is linked to the functions performed by residents. Thus, the modifications associated with this dimension are typically related to the space size and arrangement.

◦ Residents’ need to modify the house based on their interests related to intangible factors, such as their desire for a particular style. It also includes residents’ adherence to cultural norms and religious values, such as family gatherings and privacy, as well as their concern for natural resources, budget, and quality.

◦ Residents’ need to modify the house based on their opinions and perceptions. This includes their satisfaction with the current design and modifications, future plans, and perspectives on the essential housing requirements.

So, this fills gaps in the literature and answers the research question, which states: what are the issues that lead to residents’ modifications in Bahraini subsidized housing units?

6 Conclusion

The process of residents’ modifications in subsidized housing results from residents’ behaviors associated with a combination of shared factors and distinctive lifestyles. This study has examined two dimensions: similarities and differences in residents’ behaviors in Bahraini subsidized housing. The findings indicate that most Bahraini residents prefer simple, modern designs with spaciousness, openness to outdoor spaces, and modern materials and techniques. Results also highlight the importance of sustainable housing units that incorporate all three aspects of sustainability, particularly the socio-cultural. They have also revealed the critical role of experts in this process in minimizing these modifications and avoiding violations when hiring them from the beginning.

Moreover, results show that lifestyle has a strong relationship with these modifications. Therefore, it’s crucial to consider the common behaviors of residents in subsidized housing when designing future housing projects. Simultaneously, housing units must be flexible and adaptable to accommodate the evolving lifestyles of families and allow for modifications at any time. This will, in turn, contribute to reducing and streamlining the process of modifications.

This study also confirms the significance of studying the two directions related to residents’ modifications in subsidized housing: similarities in the prior-occupancy stage and differences in the post-occupancy stage. This is because most previous studies concentrated solely on the post-occupancy stage, although residents usually begin making modifications during the pre-occupancy. Future research should therefore focus on these two directions investigated in the two phases of this study: the first phase was general, related to similar and repetitive behaviors of most people. In contrast, the second phase was more specific and linked to the behaviors of individual families and their different lifestyles. So, studying both phases is essential to determining the issues leading to residents’ modifications in subsidized housing. Thus, both of them were required to answer the research question comprehensively. This study provides a comprehensive conceptual framework for studying the two directions. It lays the groundwork for future research addressing the same issue in different regions in Bahrain, the Gulf countries, and worldwide. Therefore, the research proposes using the same two-phased methodology to study the same issue in other housing projects locally or regionally. Despite its antiquity, modifications are ongoing and must be explored from time to time in different regions. This study focused on the East Hidd project, so further research should focus on other housing projects in Bahrain to explore other issues related to this phenomenon.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because raw data is restricted for access to keep the privacy of identifiable matters. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWF5d2xhZmlAZ21haWwuY29t.

Ethics statement