94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Built Environ., 22 May 2023

Sec. Urban Science

Volume 9 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2023.1154523

This article is part of the Research TopicNew Approaches for Sustainable & Resilient Processes and Products of Social Housing Development in the Arabian Gulf CountriesView all 13 articles

Mae Al-Ansari*

Mae Al-Ansari* Saud AlKhaled

Saud AlKhaledIn September 2015, the State of Kuwait signed the UN’s 2030 Agenda, committing to all 17 of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include the building of sustainable cities and communities through initiatives such as social housing. In response, the New Kuwait Vision 2035 has witnessed a shift in approach to the social housing paradigm at the state level. This paper examines the status of recent social housing projects in Jaber Al-Ahmed City, Kuwait, through a critical, evidence-based analysis of the decision-making processes and urban-architectural products that shaped its development. The mixed-methods data for this case study were generated via archival research and semi-structured interviews supplemented with field observations to evaluate the local and international sustainability agendas implemented in the city as process and product. Principles of Sustainable Urban Forms are implemented for the evaluation. The article also presents evidence of local urban practices (resident appropriation and participation), legitimized environmental practices, and community wellbeing. It concludes with recommendations for resolving issues in the current processes around the design and implementation of sustainable urban forms to inform future social housing developments. These recommendations for sustainable social housing in Kuwait provide an opportunity to revisit and reconsider the core values of sustainability while adding to the multiplicity of its definitions. Although recent social housing projects in Kuwait may demonstrate an overall effective process-to-product procedure as a means of architectural production that addresses the country’s housing demand, important aspects remain in question with regard to sustainable built environments.

In December 2012, at the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference in Doha, Kuwait announced its commitment to diversifying its energy sources by exploring its solar and wind capabilities, committing to an increase in its use of renewables to 1% of total energy consumption by 2015 and 15% by 2030. Building on this initiative, Kuwait endorsed and committed to all 17 of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in September 2015, including SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. This SDG entails a commitment to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” (United Nations, 2015; General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, 2019, p. 67). Accordingly, the government formed the National Sustainable Development Committee (NSDC) and the National Observatory of Sustainable Development (NOSD). It also tasked the General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development (GSSCPD) with drafting the third Kuwait National Development Plan (KNDP) to align with the New Kuwait Vision 2035 (General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, 2020). The KNDP aims to “transform Kuwait into a financial, cultural, and institutional leader in the region” (Al-Sharhan, 2017). Kuwait’s Vision 2035 set forth seven pillars based on the 17 SDGs, including Pillar 5: A Sustainable Living Environment, which “aims at ensuring the availability of living accommodation through environmentally sound resources and tactics” (General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, 2019, p. 18). The Kuwait Voluntary National Review (VNR) to the UN (2019) records that the Public Authority for Housing Welfare (PAHW) participated in the steering committee for this process. However, the VNR provided very limited information about the housing outlook beyond the 2016 data showing the completed number of units (26,874 plots and 26,308 houses) and those being prepared or under construction (17,234 plots and 3,676 houses). These decisions have enabled Kuwait to consolidate a “sustainable” approach to social housing, although previous social housing initiatives did not adhere to any particular aspect of sustainability.

There has been minimal research into sustainable urban forms (SUFs) and sustainable social housing in the Arabian Gulf, and Kuwait in particular. Within the general discourse on sustainability and urban forms that emerged in the late 1990s (Frey, 1999; Jenks, 2000; Williams et al., 2000), a new theoretical framework for restructuring and understanding the form of sustainable cities was proposed in 2006 by urban planning scholar Yosef Rafeq Jabareen. Loosely described as the achievement of sustainable urbanism through the configuration of the functions, shape, and resiliency of city form (Ahmed, 2017; Mobaraki and Vehbi, 2022), the SUF concept merges four known urban forms with combinations of sustainable design concepts that define the sustainable city in terms of its social, economic and environmental aspects. According to Jabareen, these sustainable urban forms are neo-traditional development, urban containment, the compact city, and the eco-city. They are achieved by operationalizing seven design concepts: compactness, sustainable transport, density, mixed land use, diversity, passive solar design, and greening (Jabareen, 2006). The author’s proposal aimed to establish a reliable “sustainable urban form matrix” to aid the evaluation of city form.

In 2017, Mohammed Galal Ahmed adopted Jabareen’s framework to evaluate SUFs in Emirati social housing located in Al Ain City, United Arab Emirates. Ahmed compared a “conventional” neighborhood (Al Salamat) to a “sustainable” neighborhood (Shaubat Al Wuttah) by applying a customized set of sustainable design principles, an approach that informed and expanded the discussion of SUFs in the Arabian Gulf (Ahmed, 2017). Extending Jabareen’s matrix, his inquiry is particularly responsive to the cultural nuances of sustainable social housing in the region. He merges aspects such as density with compactness and added elements like privacy, safety, imageability, resilience, accessibility, local autonomy, and choice to his SUF matrix (Ahmed, 2017).

While Jabareen and Ahmed examined SUFs, other scholars approached sustainability in Arabian Gulf architecture and urbanism as a discourse on political, economic, and social policy. Yasser Elsheshtawy (2018) reviewed various examples of Arabian Gulf projects to demonstrate how the commitment to construct sustainable built environments is deeply intertwined with the process of nation-building. He argues that a “greenwashing” strategy underpinning the rhetoric of sustainability has been adopted by Gulf nations to appease foreign entities and gain international recognition (Elsheshtawy, 2018, p. 3). While the focus on sustainability fulfills the New Urban Agenda (NUA), he claims the practices remain neither sustainable nor resilient. Urban policies that support housing sprawl, residential segregation, privatization of public space, and higher land values demonstrate this trend. As a result, governments in the Arabian Gulf have tended to focus on achieving technologically enhanced environmental measures of sustainability rather than resolving social concerns within their communities. Meanwhile, the Arabian Gulf city remains car-centric, less energy-efficient, and characterized by low-density developments and a scarcity of freshwater resources (Elsheshtawy, 2018, pp. 4–7).

Similarly, Eric Verdeil asks: “Why does green urbanism in MENA countries seem to be underdeveloped?” (2019, p. 36). He observes that in the Arabian Gulf, support for urban and architectural sustainability is intertwined with achieving social stability and the strategy of worlding, wherein nations base decisions on the extent to which they contribute to the image they wish to portray to the world—particularly that of their developed status (Verdeil, 2019, pp. 35–36). Pursuing social stability through the engagement of modern forms of consumption that may not be environmentally friendly undermines the commitments made by adopting environmental policies aligned with international standards. Urbanization, Verdeil remarks, “remains car-centric and privileges individual sprawling housing for the nationals, both of which can only thrive thanks to massive energy and resources consumption and environmental losses” (2019, p. 38). He thus concludes that the governance of sustainable urbanism in Middle Eastern countries lacks an overall concern for ecology and calls for ordinary urban practices to be examined and accommodated by policymakers through design intentions and building codes that demonstrate their commitment to local sustainability measures. These include strategies such as subsidy cuts to water, electricity, and gas services offered by the government that encourage reduced usage by consumers (Verdeil, 2019, pp. 37-39). Likewise, in his study of the sustainable ambitions of Masdar City, UAE, and the consequences of its implementation, Laurence Crot agrees with both Elsheshtawy and Verdeil, suggesting that urban sustainability schemes in the Arabian Gulf have been geared to satisfy a “social contract” between the governments and people as a form of appeasement at the expense of impacting real change (2013).

Considering the sustainability of Kuwait’s urban development, Muhannad Albaqshi recognizes that the country’s modern neighborhoods possess a “latent” sustainability that has not yet been realized. Although Albaqshi notes that “Sustainability is already present in the blueprint of Kuwait’s urban fabric” (2010, p. 108), preference for urban sprawl and car dependency hinder the development of aspects such as walkability and multimodal transportation. Based on Doug Farr’s definition of sustainable urbanism, Albaqshi outlines ten core principles for assessing Kuwaiti neighborhoods: (1) limited population, (2) limited physical area, (3) mixed-use zoning, (4) urban characteristics, (5) prime access to public spaces, (6) pedestrian-friendly streets, (7) efficient mass transit system, (8) high-performance infrastructure, (9) local character in urban design elements, and (10) sustainability policies addressed at all scales. While Kuwaiti neighborhoods tend to meet the criteria of limited density, area, mixed uses, public space, and characteristics of urban design, Albaqshi notes the need for more pedestrian-friendly streets, along with an improved mass transit system, elements of urban identification and local character, and an environmental agenda through which poor waste management and energy consumption are addressed. For example, he proposes the revision of local building codes to discourage residents from parking cars on sidewalks (Albaqshi, 2010, pp. 116–118).

The issue of sustainable urbanism has recently been addressed in work examining the political connotations of social housing in the Middle East (Kilinc and Gharipour, 2019, p. 2). The authors note how the general move towards neoliberal economic practices in the region—particularly in the Arabian Gulf area—has accompanied a decline in centralized participation by governments in providing social housing due to high construction, infrastructure, and maintenance costs. This has resulted in public-private partnerships for the design and construction of social housing, which limits the possibility of participatory design for housing recipients, among other issues. Inevitably, such a change impacts equitable access to housing as a process provided by Middle Eastern governments, but it also establishes social housing as a crucial product in need of sustainable development.

Within this discussion, it is worth noting that sustainable social housing is crucial to Kuwait’s push to reach its UN-mandated SDG goals. Yet scholars describe social housing in Kuwait—like many other Arab Gulf countries—as a “tradeoff” and “battlefield” between the state and its citizens (Sadik, 1996; Al-Dekhayel, 2000). As Mae Al-Ansari (2016) puts it, “The state gains leverage through the distribution of wealth and the establishment of institutions that confirm its national independence. In return, citizens accept material satisfaction and adopt the Kuwaiti political regime” (p. 264). Similarly, in the recent past, Kuwaitis appeared to consider government housing as their preeminent right as citizens—even more so than the right to vote (Sapsted, 1980, p. 106). Historically, massive social housing construction campaigns have driven the modernization of Middle Eastern nations (Sadik, 1996, pp. 32–35). Thus, the State of Kuwait continues to carry these visions, values, and ideals for social housing as the 21st century unfolds and it navigates the expectations of its citizenry and the world at large. The challenging question then becomes how the government negotiates these dimensions—as both process and product—considering its support for the SDGs and its commitment to creating sustainable living environments.

Kuwait’s social housing initiative began in the early 1950s as one among many of the services offered by the new, modern, welfare state that emerged from the former pearling and trade center of Kuwait Town. The government’s “cradle to grave” policy used incoming oil revenues to provide citizens with access to education, healthcare, housing, and employment. From inception, the policy focused on the overall wellbeing of the population, and this concern was reflected in the subsequent design of Kuwait City and its suburbs in 1952 by British planners Minoprio, Spencely, and MacFarlane. Suburban neighborhoods were designed as self-sufficient communities modeled on the English Garden City, with detached single-family dwellings, schools, and mosques. Based on the Perry (1929) “Neighborhood Unit” concept, these districts also featured secondary commercial nodes distributed among neighborhood blocks offering services such as dry cleaning, tailoring, and small shops, as well as the main service core containing a supermarket, government offices, a clinic, and other large commercial services. The intention was to create a neighborhood fit for the modern Kuwaiti lifestyle (Ghareeb, 2020).

Since its establishment, Kuwait’s social housing program has been characterized by gradual, piecemeal distribution within neighborhood units in the form of houses, land plots with construction loans, and apartment units. Around 1952, social housing in Kuwait was established via plots in newly planned neighborhoods. These were exchanged for “appraised” housing in the town center, which would be demolished to accommodate the new modern Kuwait City center (a process known as Tathmeen, or “appraisal”). The funds received from the appraisals enabled families to construct modern, detached, single-family villas. Two-story housing units were also constructed directly by the municipality in the mid-1950s for those with limited income, and the demand for housing began to rise. The Housing Welfare Law came into effect in 1967, and the government’s “Land and Loan scheme” saw it continue to construct and allocate detached and semi-detached housing to citizens, as well as offering special financing options with 30-year, interest-free loans to help a new generation of citizens construct homes. The 1970s and 1980s saw the first social housing apartment units, as projects such as those located in Sawaber and Sabah Al-Salem were commissioned to accommodate the rising values and reduced availability of land. This period also saw the emergence of dissatisfaction among middle- and lower-income housing residents, whose responses to National Housing Authority surveys revealed they were modifying their units during their first year of residency (Al-Ansari, 2016, pp. 282–284).

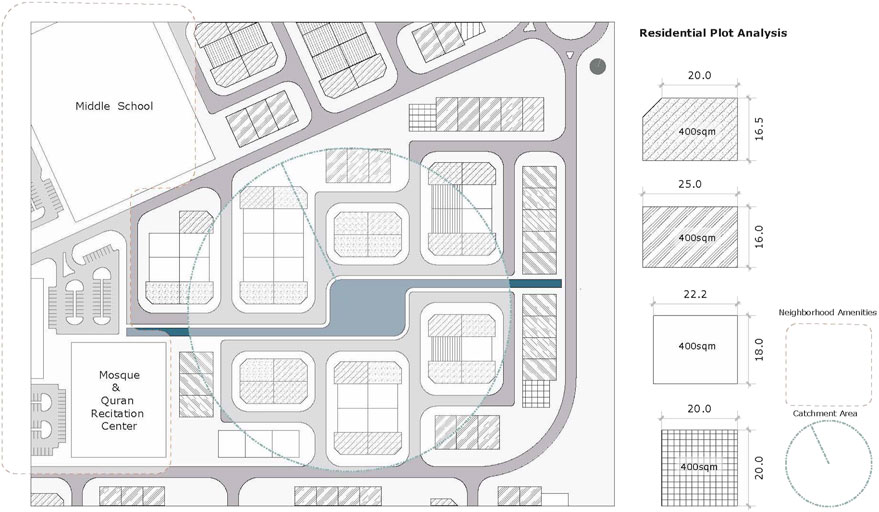

After much criticism of the income-based disparities in its provision, the government standardized social housing in the early 1980s to offer 400 m2 plots for all, with a specific built-up area and set of program components. In doing so, it dispensed with apartment units as viable social housing options. Different versions of the land and loan scheme have since been implemented, with a few recent exceptions such as the distribution of a small number of detached houses under exceptional circumstances in 2021. In early 2005, the focus of social housing in Kuwait turned to self-sufficient satellite towns (Ghareeb, 2020, p. 88), with the PAHW currently distributing plots in South Sabah Al-Ahmed City (20,380 units) and South Saad Al-Abdullah City (24,508 units). Three additional cities are being planned at Khiran (45,000 plots), Sabriya (52,000 plots), and Nawaf Al-Ahmed City (52,000 plots).

This summary of Kuwait’s social housing history demonstrates, among other issues, the trial-and-error approach to housing provision adopted since the establishment of the country’s welfare state. It also demonstrates how the state has striven to achieve different forms of sustainable living, whether through equitable access to plots, the construction of housing units, the provision of financial options in the form of long-term, interest-free loans to support housing construction, or by prioritizing the general welfare of its citizens. These goals are reiterated in the country’s latest National Development Plan for 2025 (General Secretariat of the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, 2020, 2020, p. 185).

According to its Deputy Director General for Planning and Design, the PAHW is committed to achieving the energy goals set forth by the late Emir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed Al-Sabah, in line with the 4th Kuwait Master Plan 2040: Towards a Smart State. As such, the PAHW has set the following energy initiatives as targets for 2030, some of which have already been achieved:1

• 20% of the energy needs of new public buildings will be met by renewable sources.

• A smart sustainable model home will be designed and constructed.

• 1,184 social housing units that use renewable energy for water heating will be completed in the neighborhood of East Sabah Al-Ahmad.

• New zoning codes will be developed to ensure 10% of housing energy needs are covered by renewables.

• New building specifications that include renewable energy and green building regulations will be developed to ensure that 5% of new-build energy needs are met by renewables.

• A feasibility study will be conducted that explores the viability of district cooling through 40% use of renewable energy in new social housing neighborhoods.

• Smart cities will be designed and constructed.

The Head of the PAHW’s Electrical and Renewable Energy Division claimed that the 20% target to use renewable energy in public buildings has been accomplished by using solar photovoltaic systems, water treatment systems, solar water heating, and wastewater management. Even higher percentages of renewable usage have been achieved in some public buildings such as mosques, schools, clinics, and police stations. As of 2018, over 80 public buildings had been completed, over 200 buildings were under construction, and approximately 453 buildings were in the tendering phase, all of which use at least 20% renewable energy.1 Furthermore, the PAHW hopes that district cooling will be a standard feature of future neighborhood designs.

In 2012 and with the support of the private sector, the PAHW began the process of designing, constructing, furnishing, and maintaining House 2035, a smart sustainable model home that encapsulated the Public Authority’s outlook on embracing sustainable living by encouraging Kuwaitis to adopt a more environmentally sensitive lifestyle (Figure 1). A low-energy prototype, House 2035 is a 400 m2 detached, single-family villa located in the Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood that is fitted with sensor technology to display “normal” home consumption of resources (e.g., water and electricity) (National Technology Enterprises Company, n.d.). Eight smart meters are installed throughout the house to monitor the energy produced by solar panels, including electricity consumption, a significant portion of which comes from air conditioning. Inaugurated on 20 February 2020, House 2035 has produced real-time readings since at least October 2021 and is expected to supply the PAHW with data for 5 years. As a “showcase house,” House 2035 integrates efficient systems such as PVC solar panels, variable refrigerant flow (VRF) air conditioning systems, solar water heating, and grey water treatment. The bases for comparison include HVAC, lights, sockets, water heating, and other outlets for water and electricity consumption.

Named after the sustainability pledges made by the State of Kuwait to the UN, House 2035 provides a model of smart and sustainable building design, construction, furnishings, and maintenance. The villa was designed by architectural firm Dar SQC International Consultants with specific targets for technology and materials: availability, accessibility (physical or local access), and affordability. Market availability, distance to the supply chain, availability of labor, and the costs of transportation, installation and maintenance of technology, and building materials were all factors considered by the PAHW. The villa boasts features such as an EV charging station, LED lighting, energy auditing, and solar power, and is GSAS four-star certified (National Technology Enterprises Company, n.d.).

As for new zoning codes, in 2019 PAHW adopted an Urban Design Manual which incorporates sustainability measures linked to seven urban design principles (PAHW, 2019, p. 9). These include:

• a compact city form adapted to the Kuwaiti desert landscape,

• small-scale and mixed-use neighborhoods,

• a diverse and polycentric city,

• roads as connectors within a grid that is less hierarchical,

• integrated public transport within transit-oriented neighborhoods,

• pedestrian-friendly and green urban spaces,

• urban identity, character, and cultural sensitivity.

PAHW is also leading the country into the future through its endeavor to produce smart cities via social housing. In fact, the western neighborhood of South Saad Al-Abdullah has since 2016 been advertised as the region’s first city to be designed with environmentally friendly and smart systems in mind (Al-Abdullah, 2017; Kuwait News Agency, 2016; Kuwait News Agency, 2019). The smart city model has been adopted from and in partnership with South Korea to bring this 6400-ha city for 400,000 residents to life (Euronews, 2018). With six main approaches that encompass smart living, smart environment, smart welfare, smart utility, smart mobility, and smart safety, features like waste management, air mist cooling systems, street light remote management, EV charging systems, and water grid management become tools to realize a more sustainable, efficiently managed built environment through the monitoring and regulation of energy consumption. To achieve this vision, various public services in social housing neighborhoods must be retrofitted and/or outfitted with new systems.

More recently, the XZero development was unveiled by Dubai-based URB as a car-free, smart, zero-carbon city for 100,000 residents in Kuwait (2022). The scheme of this 1600-ha city in Kuwait’s southern region focuses on density and green spaces to enhance walkability supported by a green circular economy to provide residents with food and energy security (Florian, 2022). With features like 100% renewable energy and water recycling, zero-waste infrastructure, and a productive landscape, XZero has been described as “a unique resilient landscape which will promote health, wellbeing and biodiversity” (URB, 2022). Among other smart systems, Artificial Intelligence is employed to provide predictive analysis on consumption and production, and for aspects such as water management in efforts to create a city of resiliency and liveability (URB, 2022).

This paper adopts an evidence-based methodology to investigate and evaluate how different dimensions of sustainable urban forms operate within the social housing building typologies of Kuwait. It aims to do so by systematically examining the process-to-product relationships entailed in realizing built form. This includes assessing how design elements and decisions facilitate experiences of movement (pedestrianism), social interaction, neighborhood belonging and identity, and choice in the process-to-product spectrum. Semi-structured interviews and field observations were adopted to collect necessary off- and on-site data. These data were analyzed using the matrix of design principles set out by Jabareen (2006) and Ahmed (2017). Due to similarities between Kuwait and the UAE in such aspects as physical proximity, climate, culture, history, religion, language, governance, and economy, Ahmed’s matrix was considered an appropriate guide to the methodology and analysis used in this study. His criteria of privacy, safety, imageability, resilience, accessibility, local autonomy, and choice were viewed as highly relevant to evaluating the sociocultural context of SUFs in Jaber Al-Ahmed.

The neighborhood of Jaber Al-Ahmed was selected after careful consideration of the PAHW’s social housing projects. The following questions informed this decision: (1) whether all PAHW projects completed since the authority was established in the 1950s should be considered; (2) whether only neighborhoods with housing units constructed by the PAHW should be examined or only plots distributed for housing should be included; and (3) whether only one or a few of the numerous neighborhood projects would provide sufficient evidence to generate robust conclusions.

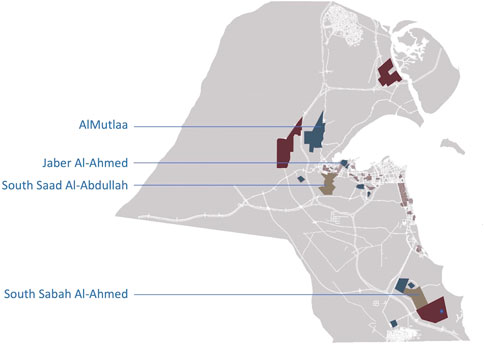

Upon investigation, the diverse approaches to design in each social housing neighborhood emerged as a necessary criterion. For example, the neighborhoods of South Sabah Al-Ahmed, AlMutlaa, and South Saad Al-Abdullah vary considerably in terms of their plot arrangements (Figure 2). The matter of scale also influenced our choice of which site to study, raising various issues including but not limited to connectivity, methods of transportation, and employment. This, along with the diversity of housing types and access to information on design process and evidence of occupancy guided the selection process.

FIGURE 2. Map showing various PAHW social housing developments (source: by authors based on Public Authority for Housing Welfare, 2022).

The clearest example of a design approach to social housing was identified as the Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood designed in 2007 by Pan Arab Consultant Engineers (PACE). Although the project predates the UN Agenda signed by Kuwait in 2015, aspects of both Jabareen’s and Ahmed’s design principles seem to be embedded in its conceptual foundations. In other words, it enabled an analysis of process-to-product to be carried out through the investigation. The neighborhood also features a diversity of housing types such as villas, apartments, and future townhouses, unlike neighborhoods such as Sabah Al-Ahmed. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, the developmental status of Jaber Al-Ahmed provided evidence of residential habitation, appropriation, and community building whereas the relatively newer neighborhoods mentioned above were designed after 2015 and the processes of plot distribution and housing construction remain incomplete.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of government authorities and design firms to shed light on the design and construction processes involved in Kuwait’s sustainable social housing. Officials at the PAHW’s Department of Planning and Design answered open-ended questions about the process of completing social housing projects in general and the design of the Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood in particular. Another PAHW official responsible for renewable energy provided insight into the sustainability initiatives of the institution. All interviewees were either architects or engineers familiar with the architectural design and construction process of social housing projects.

Neighborhood residents’ behavior was documented by collecting and analyzing aerial images and on-site photographs. Design principles were applied (1) to evaluate the success of the design of the neighborhood, street, plot, and housing unit in terms of achieving or promoting accessibility, mixed use, diversity, mobility, density, greening, and passive solar design, and (2) to document evidence of choice, local autonomy, privacy, and imageability. To determine the distances between services and housing plots, Google Earth measuring tools and features were employed. Local building codes for housing design, such as maximum built-up area, building height, and setbacks were used to contextualize and further assess the elements mentioned above.

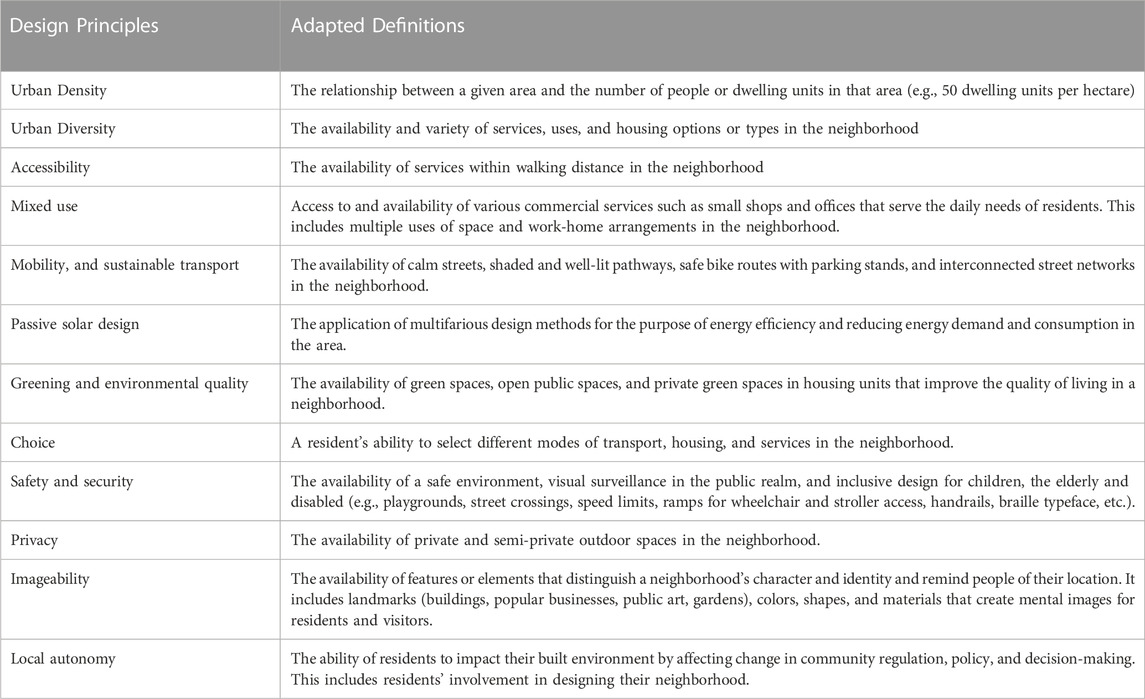

This evaluative analysis of the design principles of Kuwaiti SUFs draws on the criteria of Jabareen (2006) and Ahmed (2017) and is proposed by the authors of this study as a new sustainability approach to be adopted by the PAHW in its social housing schemes. Specific measurements and methods of examination were used to evaluate each criterion throughout the project stages of Planning, Design, Construction, and Occupancy (Table 1). They received a final assessment of Highly Considered, Partially Considered (as an aspect of either process or product), or Not Considered (Table 2). While a “Highly Considered” evaluation denotes that all dimensions described in the definition of each design aspect are satisfied, a design aspect is “Partially Considered” when at least one dimension within its definition is fulfilled, and an evaluation of “Not Considered” indicates that no defined dimensions have been addressed. A numerical scoring system has been adopted to support the analysis, as “0” refers to aspects “Not Considered,” “1” refers to aspects “Partially Considered,” and “2” signifies “Highly Considered” aspects. Tabulations of scores are provided for each design principle for reference.

TABLE 1. Design principles matrix with definitions, based on the SUF principles of Jabareen (2006) and Ahmed (2017).

TABLE 2. Assessment of Sustainable Urban Form Considerations at Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood, Kuwait.

The path to implementing the PAHW’s sustainability strategies—including the production of sustainable neighborhoods—has not been entirely smooth. Apparently, this is not due to administrative failings on the PAHW’s part but results from a lack of cooperation, communication, and overlap amongst the different government administrations and their roles in the design and construction process. For example, the PAHW’s Deputy General recounted the authority’s attempts to implement multiple regulations and codes for social housing projects such as approving new zoning codes and building specifications, as well as the installation of various forms of renewable energy systems (e.g., PVC panels on the roofs of schools and public buildings like clinics and police stations). Unfortunately, long-term operations and maintenance procedures for the systems proved unsuccessful. Even aspects of social sustainability such as walkability and accessibility were impacted: the planning of recreational elements like parks and water features must observe Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) regulations and require approval from the Public Authority for Agriculture Affairs and Fish Resources (PAAAFR), which operates and maintains them after construction is completed. Needless to say, irrigation water shortage issues in neighborhoods like JA appear to have prevented the PAAAFR from accepting the project handover.

Moreover, the PAHW’s Deputy General clarified that—even with new zoning codes—there was no guarantee that citizens would follow the renewable energy regulations unless these were upheld by Kuwait’s Municipality via the administration of new laws and the mobilization of divisions to penalize transgressions. The Deputy General emphasized that the approach needed to be holistic rather than piecemeal. As a result, he projected that a restructuring of government authorities would be required to achieve the renewable energy requirements. Hence, in Kuwait, the goal of achieving 15% or 20% reliance on renewable energy through minor interventions in building design and construction is much easier to accomplish than operating and maintaining the systems themselves.

The Head of the Electrical and Renewable Energy Division at the PAHW agreed that regulatory setbacks challenged its efforts to achieve more sustainable social housing. For example, electricity codes and regulations needed updating—a process that requires various government entities to collaborate with the Ministry of Electricity & Water & Renewable Energy (MEW). In addition, she highlighted technological challenges with some products, such as PVC panels that are especially sensitive to Kuwait’s climate. She explained that maintenance was difficult due to the dusty and humid Kuwaiti summer, and performance was often impacted because of dirt accumulation on the panels. Water is needed to remove the accumulated residue and is difficult to obtain in isolated desert sites. As a result, water tankers have periodically driven to sites where water is scarce and sprayed the panels—a solution that is costly, inefficient, and unsustainable in terms of water usage and resource management. On the other hand, dry cleaning processes increase the risk of permanently scratching and damaging the panels.

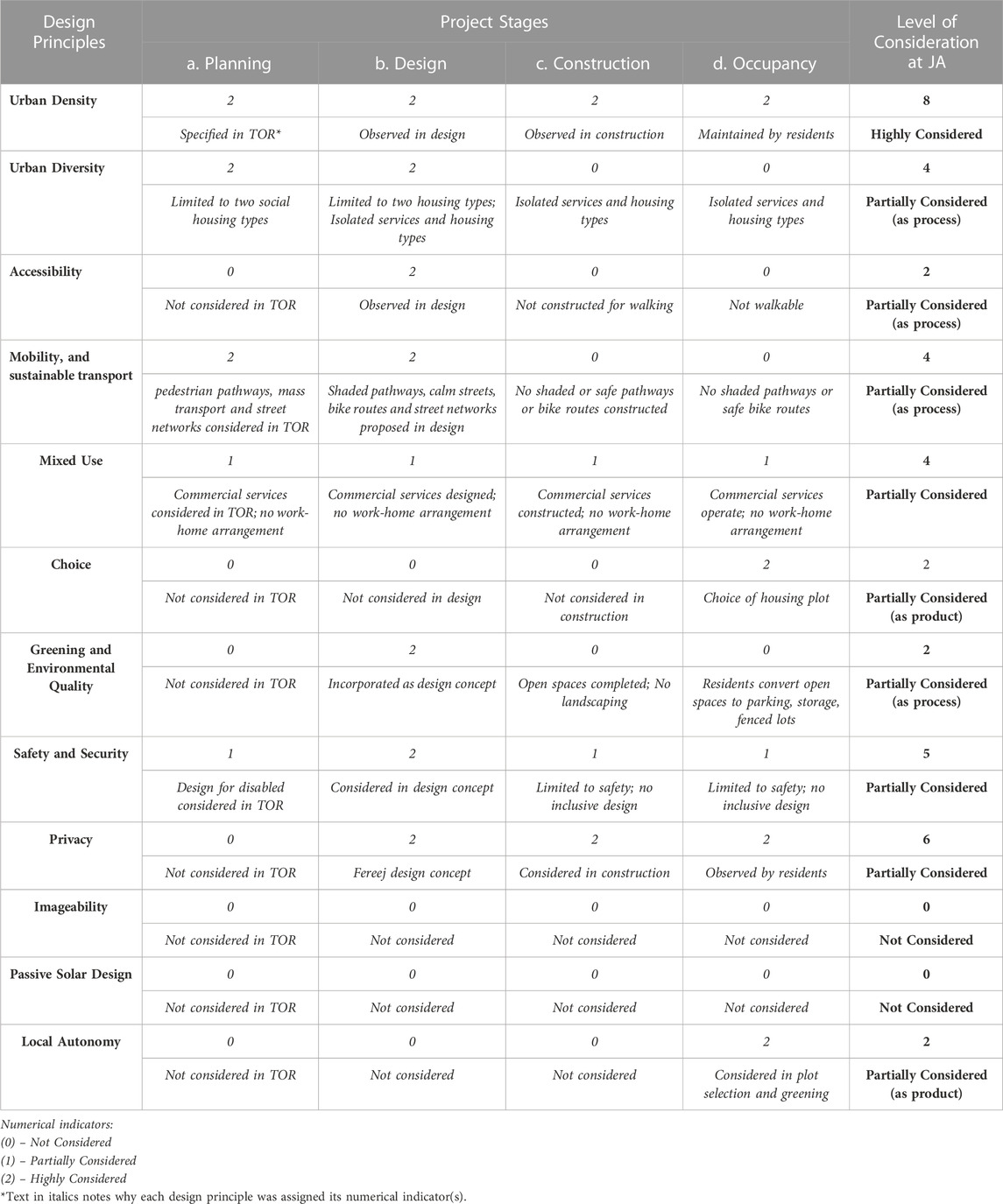

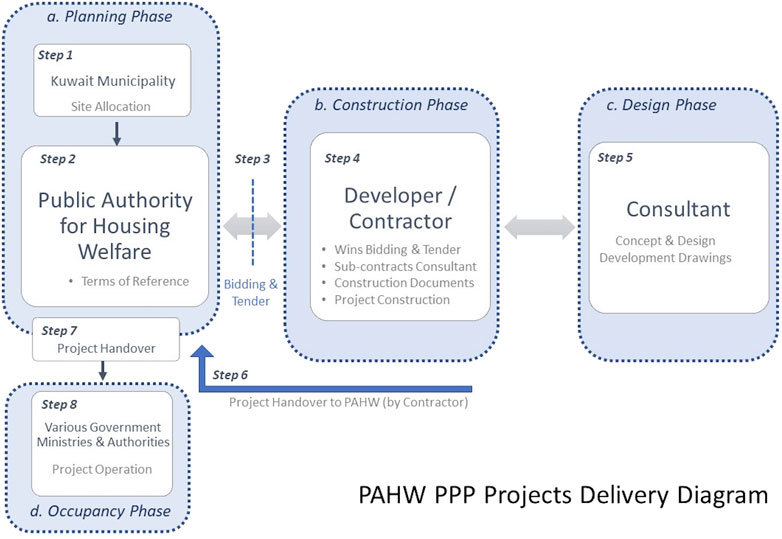

The PAHW has the capacity for large-scale project design. The process of commissioning a social housing project first requires the authority to request a land allocation from Kuwait Municipality, which, referring to the master plan, must select a site appropriate to the proposed function (Figure 3). Following approval, the municipality hands over the site to the PAHW, which checks for any obstacles or irregularities and proceeds to plan the site. This stage requires a committee comprised of ministry representatives to approve the project since it involves multiple public services, such as mosques, schools, supermarkets, police stations, clinics, post offices, commercial shops, and other facilities, including green spaces. Once this consortium of ministries and public authorities approves the project, the Council of Ministers is informed for reference.

FIGURE 3. The PAHW project delivery process, based on semi-structured interviews with PAHW officials.

The PAHW then drafts and announces a request for proposals (RFP) in the media (local newspapers and its website) wherein a terms of reference (ToR) document is issued to guide the submission of proposals by design consultants. This includes the project goals, activities, scope of work, and tasks to be performed. It covers how the site is to be organized in terms of appropriate allocation and zoning of public services, infrastructure planning, residential zoning, and road design and construction. Various studies are required by the ToR, including traffic studies, site surveys, soil testing, and studies of topography, demographics, and environmental impact. Design firms respond by submitting project proposals. Once the winning proposal is announced, the design is developed in consultation with the PAHW.

The bidding and tender process follows, and the winning contractor is tasked with drawing up the construction documents, which are effectively guidelines for translating the concept into the constructed reality. Because contractors often assign shop drawings to sub-contracted design firms, the original project concept typically undergoes multiple iterations before arriving at its final form. Once the project is completed, it is handed back to the PAHW, which is also involved in supervising building works through its construction department. The PAHW then transfers the public buildings to their respective ministry authorities for operation and maintenance and distributes housing plots to the citizenry.

The PAHW officials stated that these process-to-product procedures were sometimes delayed due to the apparent lack of cooperation from the ministries involved. They claimed that some ministries do not accept the project handover and refuse to allocate budgets for operating and maintaining the buildings. The latter may feel that if they have not been involved in a project’s design and construction beyond the initial planning stage, they should not be tasked with subsequently operating and maintaining it. Accordingly, some Ministries have refused to accept project delivery from the PAHW, whose Deputy General Director attributed the lack of cooperation to the following: (1) the officials’ lack of awareness of the nature and importance of implementing sustainability strategies; (2) the absence of guidance or clear directives from policymakers about the importance of applying sustainability measures to projects; (3) the lack of clear government budgetary allocations to sustainable strategies and systems; and (4) the lack of incentives for implementing sustainable design across the state sector.2 These issues were seen most prominently in the reduction of JA’s “Green Finger” concept to isolated green spaces on paper, which have taken the form of barren, fenced desert islands within the neighborhood blocks.

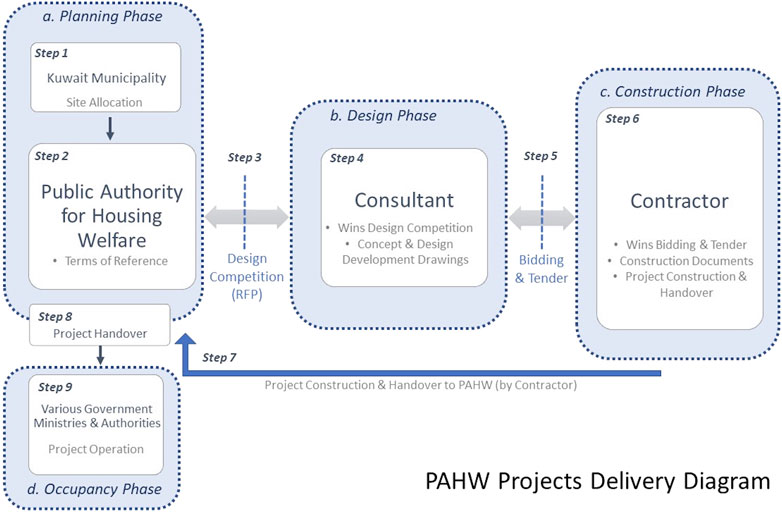

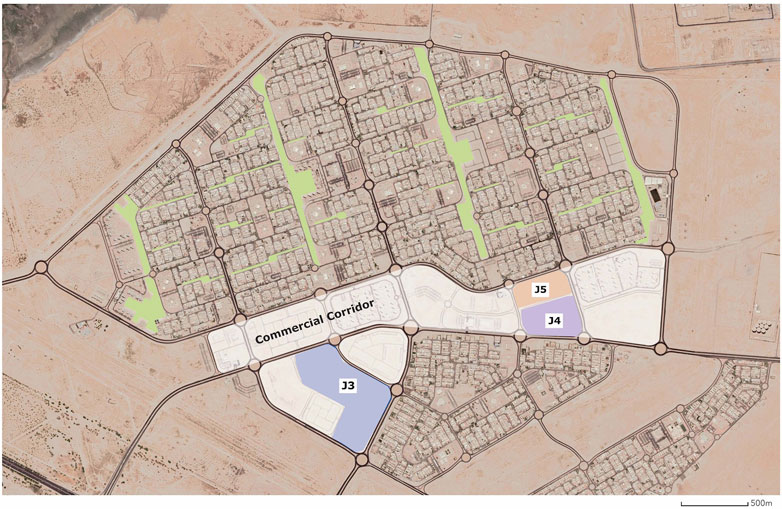

In recent years, the PAHW has shifted its vision towards privatizing its public services. Its processes seek to design successful neighborhoods that account for the needs of residents and the wider market. This trend reflects the Middle East’s wide embrace of neoliberal economic policies and the observably shrinking role of central authorities in housing provision (Kilinc and Gharipour, 2019). In Kuwait in particular, this shift has been encapsulated by the introduction of public-private partnerships, or PPPs, into the PAHW’s projects. In these models, the PAHW commissions an organization to develop the project, which is then subcontracted to a design consultant and construction firm for completion (Figure 4). The PPP model aims to both reduce delays in design and construction and short-circuit any mediations that might interfere with the progress of the project. The involvement of the private sector accelerates the design and construction schedule while allowing the developers to benefit from an allotted time frame before transferring the project back to the PAHW, which in turn profits through continued operation and maintenance of the project after the handover is complete.

FIGURE 4. The PAHW project delivery process (PPP approach), based on semi-structured interviews with PAHW officials.

The J3, J4, and J5 zones at Jaber Al-Ahmed are being developed on the PPP model between the PAHW and the private sector (Figure 5). In August 2020, a PPP contract was awarded to local companies including Mabanee (a large real-estate development company) to design, construct, finance, operate, maintain, and transfer the investment to the PAHW (SaudiGulf Projects, 2020; Public Authority for Housing Welfare, 2022). J3 is currently being designed as a commercial zone with 276 housing units attached (Makhoul, 2021). In detail, it consists of two large-scale shopping malls, open green spaces, mosques, and residential building types (townhouses and apartments with parking spaces) developed as a PPP investment opportunity between PAHW, Mabanee, the contractor, and the design consultant. The benefits of this neighborhood design include its walkability, its community gathering spaces, and the easy access it provides to commercial activities at the malls.

FIGURE 5. Map of Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood showing neighborhood blocks, green finger strips, the commercial corridor, and PPP investment zones J3, J4, and J5. (source: edited by authors based on Google. (n.d.), 2022).

The PAHW’s initial aim for Jaber Al-Ahmed was to develop a “contemporary city to support Kuwait’s growing population,” that would offer a self-sufficient and “unique and progressive style of living” (PACE Architecture Engineering + Planning, n.d.). The design of the neighborhood, located roughly 22 km west of Kuwait City and slated to house a population of 80,000, was to include a mix of low- and high-density housing types, low-rise apartment buildings, shopping malls, government and municipal buildings, sports facilities, private universities, and hospitals on 1,244.54 ha (Figure 5). At the smaller residential scale, and in line with local neighborhood design schemes developed since the 1950s, mosques, shops, schools, and parks had to be situated within walking distance from people’s homes. At JA, villas must follow Kuwait Municipality building codes that restrict 400 m2 plots for detached single-family housing to a maximum three-floor height of 15 m, a maximum built-up area of 210% (with 120 m2 permitted on the top floor) with setbacks of 2 m from the service road and 1.5 m on all other sides of the plot (Kuwait Municipality, 2022). The project’s RFP encouraged bidders to use urban design thinking creatively and propose environmental solutions.

The Terms of Reference (ToR) for the Jaber Al-Ahmed neighborhood project were issued in December 2005 with the project vision to be developed by mid-2007, a duration of 546 days or about 18 months. The ToR describes the project’s main components: the neighborhood would offer about 4,921 plots or houses for a population of 80,000 people. Moreover, it would provide a commercial zone for private sector engagement in the form of shopping malls, private hospitals, universities, and schools, an Olympic village, and high-rise investment housing of a relatively high density at 100–150 m2 per apartment. Housing types would be offered in low-density, single-family “villa” plots of 400 m2 as well as what the PAHW termed “vertical housing” in the form of six-story apartment complexes on 1,000 m2 plots containing 400 m2 apartments. Services to promote a self-sufficient neighborhood would include health clinics, schools, supermarkets, safety facilities, artisan spaces, and leisure and entertainment spots.

The government assumed this solution would help to provide Kuwaiti citizens with equal, or at least equitable, access to housing. They attempted to further incentivize apartment living in the ToR by explicitly encouraging consultants to consider how they would market this type of housing to Kuwaitis. Consultants were also encouraged to align new methods of neighborhood planning and housing design with the Third Kuwait Master Plan and with conditions in neighboring urban areas as well as the PAHW’s recommended land use plan. They were additionally urged to incorporate non-conventional methods of wastewater treatment and recycling. These instructions required the consultant to conduct environmental studies and opened the door to SUF design thinking. The ToR also aimed to foster a cooperative ethos among government entities to develop the overlapping services of facilities operated and maintained by the Ministries of Health, Interior, Education, Awqaf & Islamic Affairs, the Public Authority for Youth & Sport, and the PAAAFR.

However, the instructions were essentially limited to those described above. For example, while the consultants were specifically required to submit traffic studies using different platforms and methodologies, features specifically designed for pedestrians and people with special needs were barely mentioned beyond the advice to consider these profiles when planning the site (e.g., by allocating pathways and pedestrian bridges). Similarly, there was little consideration for human experience, identification in space, and movement in terms of design instructions, studies, and deliverable proposals. Interested parties were expected to submit sufficient studies of demographics and social context, but no explanation of how to do so was provided. The ToR can thus be viewed as car-centric, with the prospective designs requiring minimal study of alternative/mass transportation solutions.

While the ToR covered general information about the social and demographic profiles of the project’s residents, economic and feasibility studies for investment opportunities at JA were articulated in greater detail. For example, the PAHW issued explicit instructions to maximize profits from the commercial zone, while there was a missed opportunity to amplify artisan spaces as empowering the entrepreneurial potentials of citizens of all ages and genders. These spaces could have been explicitly framed as spaces of production (i.e., to support citizens’ earning capacity) as opposed to spaces of consumption (i.e., to encourage citizens’ spending).

The JA neighborhood’s design resulted from an open design competition established and publicized by the PAHW, with the winning proposal submitted by PACE. The project design was developed by PACE in collaboration with the PAHW but was tendered by the authority, which assigned a contractor to complete the shop drawings and construct the project. The original concept ultimately underwent three to four iterations and translations—from designer to client and contractor to sub-contractor—before reaching its final form.

While sustainability was not a clearly articulated initiative in the PAHW’s ToR for the design of the JA neighborhood, the PACE executives explained that this practice was common in the government sector, where design consultants are encouraged to submit innovative project proposals. Consultants can also suggest modifications or additions to zoning codes, building regulations, and specifications for Kuwait Municipality and the PAHW to consider. These points are consistent with the proposed coastal park that features in the concept diagrams of the north of JA.

To address the type and scale of public services proposed for JA, PACE contacted all the government authorities to gather their programmatic requirements. Once the information was received, the program was compiled. The design of the project’s commercial services zone (or corridor) resulted from PACE’s efforts to communicate with the authorities (Figure 5). Thus, the positioning of elements such as the Olympic village and educational zone (to the east and west of the site, respectively) ensured minimum disruption to the neighborhood in terms of traffic, noise pollution, and overall safety.

Unfortunately, when comparing PACE’s design proposal for JA to the completed neighborhood, the project’s feature Green Finger concept is difficult to distinguish. Barren islands and open desert spaces have been taken over by awnings for private parking spaces and fenced in by trees—an apparent encroachment by neighborhood residents. This result cannot be attributed solely to the PAHW, PACE, or the contractor. From the conception of the design by the consultant until the design documents move to the contractor for tender and bidding, the project undergoes multiple iterations before its final form takes shape. Yet again, one must acknowledge the tension in designing and delivering government projects, wherein the vision is not always fully realized by the contractor, who completes shop drawings according to a foreign architectural concept and builds the project at competitive costs. In the current case, this all-too-common outcome of urban and architectural projects eroded the infrastructural nuances of sustainable living in the social housing project.

JA residents have already called on the government to provide essential services like access to mass transportation (e.g., opening bus routes), beautification of the neighborhood, and the opening of various schools (Arab Times, 2019a). Such provision may be considered less a design issue than one of management, operation, and maintenance. However, the process and product of design inevitably inform the long-term success and longevity of social housing projects like this. More importantly, one wonders how well the recent shifts in decision-making address aspects of sustainable living, and whether these new measures of social housing production will attract Kuwaitis to live in the neighborhoods.

Given the neighborhood was designed for a population of 80,000 on 1,244.54 ha (PAHW, n.d.), JA’s per hectare population density (pph) only narrowly exceeds the target parameters established by Ahmed (2017) (50–60 pph) at 64.3 pph. While residential density in the design process was primarily calculated using the information provided by the PAHW and PACE as a general guide to both commercial and residential units, its calculation in the design product extracted values directly from the neighborhood design (i.e., where different site densities could be isolated) (Pont and Haupt, 2009). This yielded two ways of calculating density, which the researchers attempted to reconcile by understanding the relationship between JA’s commercial and residential density (Figure 6). While the ToR guided the designer and predetermined overall density during the design process, it only determined the projected population of 80,000 people, without specifying the number of site users such as residents, visitors, and commercial and government employees. Accordingly, the residential share of the neighborhood was calculated to be about 25% of the total based on a selected area of interest. Hence, it is inferred that JA had achieved the appropriate residential density and is Highly Considered as a criterion for the design of SUFs.

FIGURE 6. Plan diagram showing the nature of the cul-de-sac fereej configuration that promotes a sense of safety and security in the neighborhood, the plot setbacks from the street, street widths, and the catchment area from the main green finger strip to the neighboring dwelling units to assess access.

JA offers detached and vertical social housing options. However, their design undermines the SUF criteria in two ways: (1) it lacks diverse plot sizes since all plots for detached housing are 400 m2 to ensure equitable distribution and (2) these different housing options are physically separated from one another. In other words, each housing type is zoned and relatively isolated from the others. One case in point is the arrangement and location of vertical housing (six-story apartment complexes) throughout JA (Figures 5, 7). While these have been dispersed throughout the neighborhood at different locations relative to commercial nodes, their proximity starkly resembles and recreates the conditions found at the apartment complexes of the Sabah Al-Salem Housing Project (SSHP). SSHP has desert islands that form a moat-like buffer zone around the housing project. Over time, this has enhanced the feeling of physical isolation and social stigmatization among its female residents (Al-Ansari, 2019). The sole difference is that JA’s apartment units have been added in smaller groupings throughout the neighborhood such that on the master plan they appear less zoned and more “integrated” into their community environment. Yet from the pedestrian’s perspective, the housing types are clearly separated in a way almost identical to Sabah Al-Salem, which has a strictly zoned master plan.3 Thus the assessment of urban diversity at JA is Partially Considered as part of the design process and not fully realized in the design product.

FIGURE 7. Image showing the displacement of JA apartment complexes relative to the low-density scale of nearby villas.

In terms of social diversity, the JA neighborhood design provides Kuwaiti families with equal plots and imposes no income-based restrictions. Plots are distributed to families according to the date of parental marriage. It is therefore assumed that the families moving into JA are of a similar age: adult parents would belong to the same generation, while the ages of their children would also be more closely matched as a result.4

JA is also designed to offer diverse services in the form of large-scale hospitals, private universities, shopping malls, and sporting venues in the commercial corridor with smaller-scale clinics, schools, government offices, and supermarkets available in the main commercial zone. Small commercial shops, such as tailors, dry-cleaners, cafés, and salons are located closer to the plots in small and intermediate commercial zones. This arrangement is based on scale and is not a dynamic that might resemble mixed-use zoning where people live above their workplace or commercial service premises.

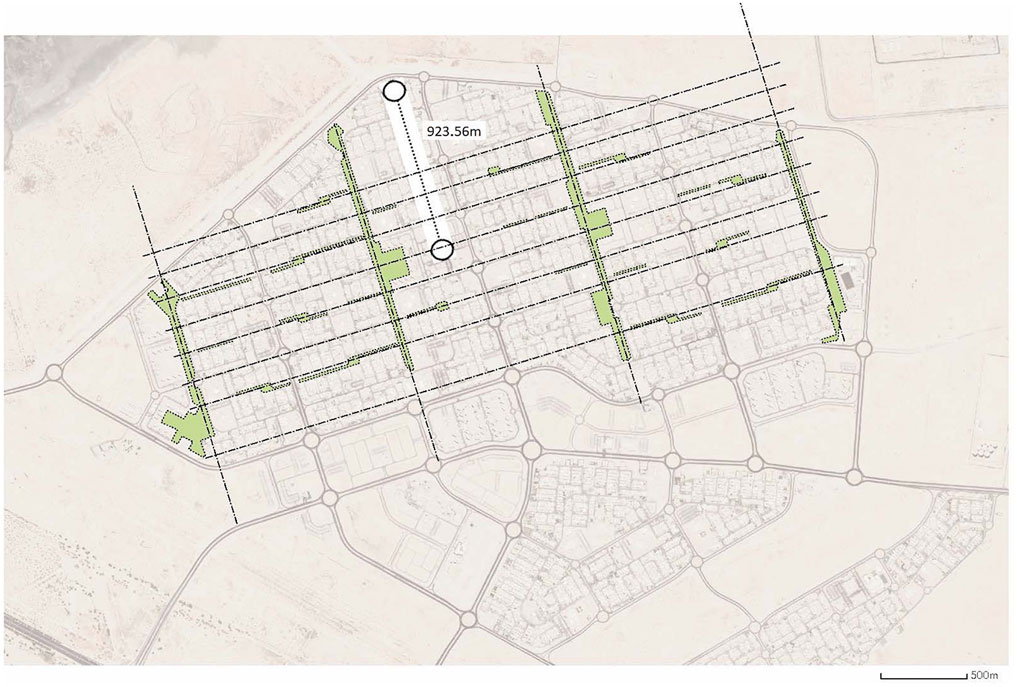

Accessibility, i.e., the ease with which a resident can reach services, is a challenge at JA. Ahmed (2017) states that services should be located 400–600 m from houses to allow ease of pedestrian access. At JA, the plots closest to the commercial nodes have the most convenient access to their services, while more distant alternatives can be over 900 m away (Figure 8). Given the absence of shading and well-lit pathways, such distances discourage pedestrianism and lower walkability, mobility, and choice.

FIGURE 8. Aerial image of JA showing the analysis of the neighborhood’s Green Finger network and the walking distance (approximately 924 m) between a residential and service location. (base map source: Google. (n.d.), 2022).

Ahmed also advocates giving public transport such as bus systems priority use of the road and restricted lanes, with bus stops at intervals of 200–300 m linking housing blocks. The reality is unfortunately that the Kuwait Public Transport Company (KPTC) is neither granted road priority, nor restricted lanes for its buses. This is as true of JA as other neighborhoods served by the state (Rhode et al., 2017). While there are bus stop signs and special drop-off zones on main thoroughfares (such as ring roads) across the country and in downtown Kuwait City, not many were observed in JA in late 2022 when the present study was conducted. This state of affairs has persisted even though, in January 2019, JA’s housing association voiced its concern at the lack of public transport services in the area and by June 2019, the local cooperative society requested that KPTC begin providing its services to JA, mainly to serve commuting workers at the cooperative supermarkets (Arab Times, 2019b). Thus, accessibility is only Partially Considered at JA in design process and is yet to be addressed in the design product.

Identified by Ahmed (2017) as the availability of more than one mode of transport, mobility presumes the existence of interconnected street networks and residential blocks, the availability of shaded, well-lit streets, pedestrian and bicycle routes with parking stands, as well as calm streets and safe modes of transport. While JA’s residential blocks are interconnected with street networks in the fereej concept, the in-between areas designated as green spaces have been left barren and abandoned. This discourages mobility, as the routes are dusty, hot, and dark at night, unwelcoming, and dangerous to pedestrians and cyclists. Moreover, the planned neighborhood does not include generous setbacks from sidewalks and walkways to benefit pedestrian residents (Figures 6, 9). In fact, plot setbacks are often taken over by parked cars, deterring residents from leaving their houses to walk to the nearest commercial service because there is no available space to walk. Children who ride their bikes are forced to do so on the neighborhood’s roads; while these are seldom busy in the interior blocks, they remain a safety risk to those sharing the road with cars. Thus, mobility at JA is very limited, or Partially Considered, although the planning and original design stages may have proposed it.

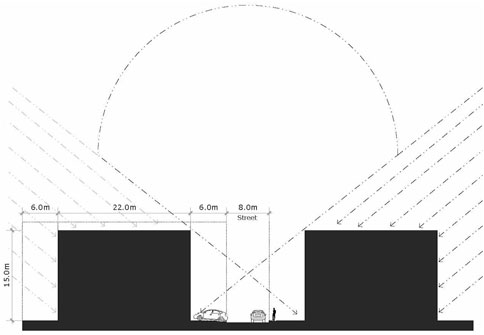

FIGURE 9. Sectional diagram demonstrating the plot setbacks from the street, the sidewalk and street widths, the indications of solar angles, and the exposure of street canyon facets to illustrate safety, security, privacy, accessibility, and the limited practices of passive solar design.

This criterion addresses the variety of zoning opportunities in a particular area. A multi-use building offering commercial services and housing can limit commutes between home and work. It also encourages mobility, as commercial services are located closer to residential units. Ahmed specifies that 40%–60% of the floor area of mixed-use buildings should be dedicated to commercial, civic, and recreational purposes, while 30%–50% should be allocated for residential uses, and 10% should be used for public services (2017, p. 8). These proportions of mixed-use facilities were not available in JA’s original design yet seem to be targeted by the J3 zone development, which includes a block of townhouses overlooking a central square near the anchor shopping mall.

On the other hand, Albaqshi’s study of Kuwait’s “latent” urban sustainability asserts that the combination of residential types and commercial nodes—as well as their proximity to one another—in ideal Kuwaiti neighborhoods constitutes a type of mixed-use zoning (2010). If this definition is applied, then both the variety of the commercial services at JA and residents’ access to these might attain the mixed-use design criteria of SUFs. Hence mixed uses at JA are only Partially Considered.

Through the years, citizens have often expressed a sense of entitlement to social housing, which many view as a form of investment. At JA, this would explain why houses have been leased out to nursery schools and other for-profit organizations, signaling to government officials that the applicants did not actually require social housing as their primary source of shelter. By allowing such informal commercial activities to take place in neighborhood blocks, the government fosters an appreciation for mixed uses of land. It is nevertheless important to ensure that such activities are sustainable and to maintain order in the built environment.

Inevitably, accessibility is tied to convenience and choice in sustainable neighborhoods. Choice entails mobility, a variety of housing types, catchment areas that overlap neighborhoods, and the existence of a hierarchy of services at different scales. While mobility and housing variety are relatively limited at JA, a hierarchy of services at different scales has been adopted from the ideal Kuwaiti neighborhood model. For example, the master plan contains small, intermediate, and main levels of commercial nodes. The first level combines religious and commercial zoning: a local mosque and small grocery store, dry cleaning service, tailor, and/or food service. This enables residents to meet their everyday needs without having to visit the main commercial zone. The intermediate node comprises a religious zone such as a Quran recitation center, a commercial zone that includes cafés and salons, and a school zone. Finally, the main commercial core or node includes the full gamut of religious, commercial, academic, and public services. Public services such as the health clinic, post office, mosque, police station, and MEW offices are found near the main supermarket, restaurants, and commercial shops.

The evaluation of choice and local autonomy in JA’s social housing provision can include the ability of each Kuwaiti family to select their plot. The PAHW randomly allocates plots to Kuwaitis via lottery-style draws. The authority’s guidelines clearly delineate the name of the neighborhood and define which parcels of land are being distributed. In response to this somewhat disempowering way of distributing land, citizens encourage PAHW employees to put citizens who may want to swap plots in touch with each another. Another unofficial practice entails allocating plots to citizens of particular tribal and ethnic backgrounds by alerting members of particular social groups when many of their applicant members would be placed in the draw. Applicants may choose when to enter these draws and when to sit them out. This forms neighborhood enclaves according to tribal and ethnic affiliations that resemble the original organic formation of family-based residential clusters in Kuwait Town.

On the other hand, the individual’s ability to autonomously impact and even alter regulations linked to Kuwaiti social housing is limited—especially because the service must satisfy the entire population. The Kuwait Municipality and PAHW are encouraged to collaborate to learn more about the unplanned, illegitimate suburban practices of neighborhood residents, so regulations may be adjusted to accommodate these needs where possible. For example, the practices of taking over public land in residential blocks to install parking awnings and enclose private outdoor space for personal uses such as gatherings and small-scale farming should be addressed by government entities. Such issues are indicative of a design problem while also providing an opportunity to generate ideas on legitimizing them in ways that do not interfere with public spaces (Figure 10). Thereby, zoning and building regulations could reconcile the legal tensions and safety risks involved in illegitimate practices while simultaneously acknowledging the validity of residents’ needs; the Kuwait Municipality has already begun to address this issue (AlEnizi, 2020). Hence choice and local autonomy at JA are only Partially Considered in the design product.

FIGURE 10. Image showing encroachment on JA’s Green Finger strips by private gardens and covered parking spaces.

This criterion covers the design of green spaces, public open spaces and streets, and private and semi-private spaces in residential neighborhoods. PACE’s main vision for the JA master plan was its “Green Finger” concept that emphasized sustainable living (Figure 8). The name referred to linear strips of green open spaces interwoven into the fabric of the neighborhood and leading north to proposed coastal parks overlooking Kuwait Bay. Programming for these green strips includes walkways, bike paths, tennis courts, and other sporting facilities that would create a recreational zone for weekend activities. The concept places the notion of greening and landscape design at the core of a successful neighborhood, implying that environmental quality is an integral part of the site infrastructure and must be designed and constructed accordingly. In other words, by the time the plots are distributed to citizens, the Green Fingers are presumed to have already been planted and furnished.

The project designer highlighted that the original Green Finger concept had shifted drastically between its inception and the finished product (Figures 11, 12). The original vision included more connected green walkways but appears to have been diluted to provide as many housing plots as possible, resulting in fragmented strips that have, in many cases, been appropriated for the purposes described above. Today the site’s “green fingers” are islands whose barrenness points to a lack of planting, which itself exposes the dire need for cooperation and involvement from all authorities at the earliest stages of the design process. The “green fingers” have now been taken over by residents for private parking, private outdoor spaces, and small-scale farming. Hence, greening and environmental quality has only been Partially Considered as part of the design process.

FIGURE 11. Image of one of JA’s Green Finger strips: a barren open space has been enclosed to prevent residents from encroaching on the plot.

FIGURE 12. An aerial image of the Green Finger strip at JA provides evidence of barren open space with scattered, fenced-off encroachments and private landscaping (source: Google. (n.d.), 2023).

Safety and security include measures of the density of a neighborhood and its compactness, the presence of mixed uses, and inclusive design for children, the disabled, and the elderly. Jane Jacobs (1961) and Newman (1973) argued that safety and security are achieved through visual surveillance in the public realm. Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” approach encouraged members of the community to share in the responsibility of keeping neighborhood streets safe through visual surveillance. The notion positively impacts the design of neighborhood buildings, with architecture facilitating surveillance and ensuring there are no “blind spots” impeding parents’ sight of their children playing on the street, or a street vendor’s view of his or her goods, for instance (Jacobs, 1961).5

Upon examining JA’s residential blocks, the “eyes on the street” theme is materialized in the proximity of the built-up housing plots (Figures 6, 9). In addition, the narrow street width reduces vehicle speed, especially since visibility is limited by cars parked on the sidewalks. However, the residential blocks rarely feature passersby—or “visitors” as Jacobs might call them—to provide diversity in terms of age, income, and working hours, as well as constant motion within the neighborhood. Between the morning and afternoon rush hours, like all suburban Kuwaiti neighborhoods, JA is relatively quiet as working parents and schoolchildren are away from home. Live-in staff comprising housekeepers, chauffeurs, and chefs remain but are not expected to participate in neighborhood protection practices. Housing plots near or adjacent to the small, intermediate, and main commercial nodes receive the added benefit of neighborhood surveillance throughout the day and additional parking spaces after working hours at the cost of greater exposure to rush-hour traffic and noise pollution.

Finally, the JA residential block design did not obviously accommodate the needs of children, elderly people, or those with disabilities. In general, such needs are normally handled on the premises according to the occupants of each plot. The commercial nodes, however, feature ramps for sidewalks and supermarket entrances to assist the movement of shopping carts, and reserved parking spots are provided for the disabled and elderly. It must be acknowledged that Kuwaiti suburban neighborhoods have relatively low crime rates, and this is in part due to the design of the self-sufficient garden city model, which discourages entry to traffic from outside the neighborhood. Consequently, security and safety do not seem to be a major focus for the designer at JA, as PACE adopted the already “latently” sustainable neighborhood design of the ideal Kuwaiti suburb. As such, safety and security are Partially Considered at JA.

Privacy can be evaluated at the different scales of neighborhood, block, and building. It encompasses the design and orientation of buildings on their plots to allow private transition spaces between interior and exterior, as well as the arrangement of housing plots in clusters or blocks.

At the neighborhood scale, privacy in JA incorporates the fereej concept, the traditional Kuwaiti neighborhood assemblage of housing units that ensures private living and calm streets (Figures 6, 9). The fereej is supported by urf (the customs of the Islamic Sunnah), which prioritizes neighborly relations and observes privacy requirements at the scale of the building, such as the prohibition of windows that overlook neighboring plots, and the inclusion of bent entry foyers that block visual access into the family or women’s courtyard. Traditional Kuwaiti architecture prohibited exterior window openings in all rooms except for the men’s diwan, which would most often overlook the public street or coastline: the windows of other rooms would face the interior courtyard (Lewcock, 1978).

This approach to neighborhood design has been retained during Kuwait’s ongoing urbanization and ensures safety, security, and privacy for ideal suburban neighborhoods in the present day. However, plot owners are responsible for the design and orientation of houses, which must follow local zoning ordinances and building regulations on built-up areas, setbacks, building heights and projections, etc.,6 It is worth noting the particular focus on privacy at the scale of the apartment housing unit in JA, as personalization, views, and sound insulation become important design factors, although they were not explicitly requested in the planning stage. A staggered building approach is adopted for vertical housing units to ensure the occupants of one building do not have visual access to their neighbors in the adjacent buildings. As such, privacy is Partially Considered at JA.

As posited by Ahmed (2017), imageability denotes the extent to which distinguishable features and activities, as well as architectural and urban design, provide a sense of identification and place for residents in a neighborhood that quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer. It is that shape, color, or arrangement which facilitates the making of vividly identified, powerfully structured, highly useful mental images of the environment (Lynch, 1960). Imageability is supported by design elements such as the path, node, landmark, edge, and district that combine to convert urban spaces into places that feel familiar. Christian Norberg-Schulz (1979) considers the experiential, phenomenological elements of architecture in creating a sense of place. He claims that orientation and identification are key to achieving familiarity and a sense of place, a term he refers to as genius loci. Whether from an urban or phenomenological-architectural perspective, identification creates a sense of belonging for both residents and visitors to a neighborhood. It fosters safety and inclusion and ties space to memory and experience. It is facilitated by high urban density, compactness, mixed uses, accessibility, and environmental quality.

At JA, the elements of imageability and sense of place appear to have been supplanted by the government’s programming requirements, infrastructure, and regulatory codes. At a large scale, these have produced spaces that people struggle to identify with. For one, the lack of landscape design in multiple roundabouts disorientates residents and visitors by rendering neighborhood streets and residential blocks generic. There are no public plazas or spaces for community gathering beyond those at the main commercial node and the “Green Fingers,” which have already been abandoned or fenced off by private residents due to underdevelopment. The residents’ protest at this lack of imageability is evident in their publicized requests for improved services in the area (AlAdala, 2021). Thus, imageability at JA is Not Considered.

Any evaluation of solar design at the building scale must account for aspects such as built form, building design, the use of urban materials and surfaces, the availability of water and vegetation, traffic patterns, and street canyons. With neighborhood street widths of about 6 m, plotline-to-sidewalk setbacks that range between six and 8 m, and building heights of 15 m, the hot and dry climate is more likely to produce rather stagnant conditions that inhibit nocturnal radiative cooling in the neighborhood (AlKhaled et al., 2020) (Figure 9). This discourages walkability and prevents residents from lingering outside their homes for social interaction with neighbors. Meanwhile, the parking of automobiles on pavements and streets also contributes to urban heat gain due to the high thermal capacity. Cars moving through the neighborhood produce anthropogenic waste heat that is often not effectively ventilated out of the residential block by the morphology of the street canyon at an efficient rate. Table 2 demonstrates the limited effectiveness of JA neighborhood’s passive solar design characteristics to meet the SUF criteria, which is apparently Not Considered in either design process or product.

This process-to-product analysis has considered the design and construction of Jaber Al-Ahmed from the client, designer, contractor, and resident user perspectives, evaluating the extent to which JA’s social housing meets the Sustainable Urban Forms criteria. As a design product, JA successfully fulfills one of the SUF criteria (Density), while the design partially considers nine categories (ranked by highest score: Privacy, Diversity, Mixed Use, Safety & Security, Accessibility, Mobility & Sustainable Transport, Choice, Greening & Environmental Quality, and Local Autonomy), and does not address two categories (Imageability and Passive Solar Design). Overall, JA is either fully or partially responsive to ten of the twelve SUF design principles examined. Analysis shows that the Design stage for JA was the most responsive to SUF criteria, followed by Occupancy, Planning, and finally Construction stage. To further enhance the ways that the SUFs might meet the State of Kuwait’s social housing needs, our recommendations on social housing policy and design process are set out below:

1. Closer collaboration and a clearer direction are required from all government authorities involved during the initial planning phases. Under PAHW leadership, the consortium of ministries should strive to fully achieve the original vision or design concept. This requires all relevant authorities to coordinate fully with each other, provide their input to the process from an early stage, and budget for the resources needed to realize the design.

2. Increased interdisciplinarity is required among policymakers, planners, financiers, developers, architects, project operators, and any (sub-)contractors that participate in the design and construction processes, in a manner that avoids disrupting or distorting the original design concept.

3. Green spaces must feature in all future ToRs provided by the PAHW. Green spaces must be considered as infrastructural components that link communal spaces and increase walkability, imageability, and social interaction with the neighborhood. This is a crucial point to make since residents should move into their neighborhoods with parks and green spaces already established and matured.

4. Before commissioning projects, the PAHW must have an overall, comprehensive vision, philosophy, or approach that guides decision-making. The sustainability directive signed in response to the UN’s 2030 Agenda is potentially one such approach. In addition, the PAHW should undertake follow-up evaluations of initiatives, using post-occupancy surveys, for example.

5. It is crucial to recognize the importance of participatory design practices and legitimize unplanned urban practices through environmentally responsive building regulations and community engagement.

Overall, this study does not propose novel approaches to designing sustainable social housing neighborhoods per se. However, it aims to support the continued reworking of sustainability measures already adopted in other parts of the world. Indeed, such measures are already evident in the PAHW initiatives at all scales, including the incorporation of sustainable technology in public buildings and dwelling units to meet renewable energy needs, the revision of building specifications and zoning codes, and the initiation of smart city design. While this singular case does not provide a generalized view of sustainable built environments, especially considering the nascent nature of this field in the Arabian Gulf and Kuwait in particular, it is one step towards understanding sustainable social housing in Kuwait. Generalizability in this case, including discussions and analysis of the Terms of References and design consultant contributions, as well as the presentation of diagrams, is particular to the JA site and the limitations of space and time.

In examining the process-to-product design procedure in the case of Jaber Al-Ahmed, no evidence was found of deliberate “greenwashing” at the state level, in the manner described by Elsheshtawy (2018). However, the rhetoric of sustainability is being engaged via partial commitments to both the international NUA and the 2030 Agenda. There is evidence of the “worlding” strategy used to gain the international recognition of developed countries: Kuwait’s commitment to the 2030 Agenda is publicized while policymakers seem to lack concern for ecology at the local level. For instance, recent news about the state’s venture into smart cities is one example of its commitment to sustainable living environments whose results remain unrealized in neighborhoods like South Saad Al-Abdullah.

Another demonstration of this trend is the latest decision by Kuwait Municipality to regulate landscaping and planting practices in open spaces in neighborhoods by issuing four-year permits (AlEnizi, 2020). This policy essentially allows plot owners to legally encroach onto public land by planting it for a limited time, thereby privatizing such spaces in an apparent effort to maintain what Crot (2013) describes as the “social contract” between the government and people. Ordinary urban practices need to be examined and legitimized by policymakers through design intent and building codes to fulfill aspects of choice at the local level. However, decision-makers must also avoid falling into the trap of the social contract that appeases citizens in lieu of effective governance measures that benefit the state. While this study marks the first steps toward examining SUFs in the Arabian Gulf, further research is required to assess local PAHW initiatives against SUF principles and the realization of sustainable social housing in the region.

This evaluation of one social housing neighborhood reveals that the impetus of design intentions may be eroded during the actual process of design in coordination with the client, and later, by the contractor. Project handovers may also decompose the original design intent or concept when various government authorities not directly invested in the project are expected to operate and maintain the properties and design features without prior involvement in the design phase. When these actors are disenfranchised, the project or product of the sustainable social housing initiative is much more likely to fail. Herein lies the paradox: the government’s resource-intensive megaprojects (at the planning, design, construction, and occupancy levels) give way to resource-intensive management and life cycles in social housing (at the level of residents). Social housing policy must not only distribute land parcels and offer public services but should also promote a framework that fosters self-organized community building and allows the adoption of grassroots practices to achieve sustainability for all (Morgan and Talbot, 2000; Plumb et al., 2011; Wheeler, 2015). Moreover, further study on post occupancy and other social housing neighborhoods is required to gain a better understanding of the dynamics at play. Such research should also emphasize how each of the twelve SUF principles impacts the achievement of sustainable social housing.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.