95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Blockchain , 12 February 2025

Sec. Financial Blockchain

Volume 7 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbloc.2024.1492739

Noble Po Kan Lo1,2*

Noble Po Kan Lo1,2* Tony Hon Yiu Lau3,4

Tony Hon Yiu Lau3,4This paper investigates the challenges and effectiveness of Hong Kong’s regulatory framework for digital assets and cryptocurrencies in the wake of the JPEX Scandal. The scandal serves as the first significant test of the city’s regulatory measures aimed at protecting consumers and investors from fraudulent activities within the crypto space. The study delves into the background and development of blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies, highlighting their rapid evolution and the associated regulatory challenges. By examining the JPEX case, the paper evaluates the robustness of Hong Kong’s regulatory tools and their ability to balance consumer protection with fostering innovation. The paper employs a doctrinal legal methodology, supplemented by a case study of JPEX, to assess whether the current regulatory framework is adequate or if further adjustments are required. The findings suggest that while significant strides have been made, certain gaps remain, particularly concerning decentralised finance (DeFi) and decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). The paper concludes with recommendations for enhancing regulatory clarity and ensuring the sustainable growth of Hong Kong as a global crypto hub.

This paper examines the challenges and the effectiveness of the current regulatory framework for digital assets and cryptocurrencies in Hong Kong. This is a rapidly developing area, as Hong Kong has only recently developed such a regulatory framework in response to a number of high profile scandals around the world in order to protect consumers and investors from fraudsters. The recent JPEX Scandal in Hong Kong represents the first real test of the new regulatory regime in place. This paper will therefore examine this case study and use it as a basis on which to assess the efficacy of the regulatory tools and regime put in force in Hong Kong in recent years.

Before going any further with this assessment however, it is necessary to briefly identify the background and context in which this debate arises, to explain what is meant by the term “cryptocurrency,” what is meant by blockchain technology, and how these tools work, as well as to explain how and why the cryptocurrency markets have developed so rapidly into a virtual “wild-west” like environment. This environment is one where whereby regulators and lawmakers around the world find themselves scrambling to try and put in place and adequate regulatory framework which is capable of effectively protecting consumers, without also stifling the development of what still might prove to be an incredibly important and valuable technological development.

The starting point of this story is the development of the technology now commonly known as “blockchain.” It was 2008 when the pseudo-anonymous individual or group of individuals under the assumed name of “Satoshi Nakamoto” first mined the so-called “genesis” block of bitcoin, and distributed the Bitcoin White Paper to the world at large (Cappiello and Carullo, 2021, p. 12). Bitcoin has, ever since, been a continually mined and operating effective proof of concept for the technology which Satoshi Nakamoto sought to introduce to the world; that of the blockchain technology (Cappiello and Carullo, 2021).

The blockchain is essentially little more than a digital ledger, capable of being interacted to by anyone holding tokens programmed to be hosted by or on that chain. A key characteristics is that the blockchain and entries upon it are indelible; they cannot be hidden, deleted, or altered once they have been entered, and no forged or fraudulent entries can be put upon the chain (Cappiello and Carullo, 2021). Bitcoin has also highlighted the potential importance of so-called “cryptocurrencies.” These are tokens, created to be able to interact with the blockchain in question, by the process of “mining” and these tokens can be sent to other users of the blockchain and verified as such indelibly, in a way which provides a very high cryptographically level of certainty or proof (Cappiello and Carullo, 2021). The term “virtual assets” includes cryptocurrencies, but is much wider than this, as stated by [Swammy et al. (2018), p. 31]. Virtual assets refer to any digital representation of value, except for, digital representations of FIAT currencies (Financial Action Task Force, 2024). Both are facilitated by the use of blockchain technologies. The use of this form of technology potentially opens up many extremely important and potentially valuable uses for crypto technology, and for the virtual assets which already exist. Not too surprisingly, extremely volatile, and largely unregulated global market places have developed to allow speculative trading of these assets.

There have been calls in recent years for enhanced state regulatory intervention in the sector. Many states around the world have begun to draw up regulatory regimes for the virtual asset markets in the hopes of taming the wild-west. Hong Kong is one of these states, which has in recent years, began to develop a clear legal framework which identifies crypto-assets as legal “property” under certain circumstances (Government of Hong Kong, 2022), and which now provides some licensing requirements for cryptocurrency exchanges or trading platforms (sometimes referred to as virtual asset trading platforms or VATPs) operating in its territory (Government of Hong Kong, 2022). Indeed, in recent days, Hong Kong’s efforts to place itself at the forefront of providing regulatory clarity for digital asset platform providers and to encourage the technological adoption and development of crypto-assets themselves have seen further developments. Here, the Financial Services and Treasury Bureau, along with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority jointly issued, on 17 July 2024, the conclusions to the consultations on recent legislative proposals to introduce a fiat-references stablecoin, or centralised digital currency in the state (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2024). The vast majority of respondents to these proposals have been supportive of legislative intent to ensure a regulatory framework for fiat-referenced stablecoin issuers, in addition to those already implemented for VATPs (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2024).

Regulators in Hong Kong have already begun to use this new regulatory framework. In September 2023 the police of Hong Kong made arrests of some 72 individuals and seized assets worth $228 million HK against the VATP known as “JPEX” and individuals associated with it (Johnston M., 2024). This was following the warning given by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) in July 2022 that JPEX had been added to its “Alert List” as an unlicensed virtual asset platform offering customers in Hong Kong access to the purchase or trading of virtual digital assets, without having acquired or applied for a license to do so (Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission, 2024). This was an early indication of the application of the new regulatory framework introduced in Hong Kong which has for the first time, required providers of these forms of digital assets to apply for a license before doing so. It is the efficacy of these investigations, prosecutions, and the framework which gives the SFC the powers exercised here which will be examined in this paper.

This paper examines emerging models of organization, such as decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), and their implications for regulatory frameworks. This is a new sort of entity which operates through the use of blockchain-enabled smart contracts, and in which each member of the DAO in question has a right to take part in the governance and decision-making of the DAO by proposing and voting on matters in a similar way to which shareholders in a company vote on matters. There has been some suggestion that DAOs are susceptible to fraud, and to abuse by some who hold significant numbers of tokens (sometimes through proxies) or who time proposals to ensure that even their non-majority holding allows them to pass resolutions (Yan and Leung, 2024). Suggestions such as insisting upon a minimum quorum to be present before DAOs might pass such resolutions have been proposed, but given the autonomous nature of these entities, and their delocalised state, how any such rules could ever be enforced is open to question. The extent to which Hong Kong’s new virtual asset regime properly addresses these concerns will also be examined here.

The key research questions to be answered here are as follows:

1) Is the virtual asset regulatory framework put in place in Hong Kong sufficient to regulate the sector given the JPEX Scandal, by ensuring transparency and accountability of digital asset platform providers, without unduly harming innovation?

2) What lessons does the JPEX Scandal in Hong Kong have for regulators as to the risks posed by the crypto environment and can regulation properly address this?

The main methodological basis for this paper is a doctrinal legal method. The doctrinal legal method is a model of legal study which seeks to ascertain the precise, accurate statement of the law as it stands in a given area (Hutchinson and Duncan, 2012, p. 88). This is an essential methodology to consider when seeking to establish what the scope and extent of Hong Kong’s virtual asset regulatory and legal framework is, as this is a question of law. Identifying the relevant sources of law in the form of ordinances passed by the Hong Kong legislature, or decisions of the appellate courts, will therefore allow an accurate picture of the regulatory regime to be put forward.

Since this paper also seeks to assess this regulatory framework qualitatively and a particular case study in the form of the JPEX scandal is being examined, some other supporting approaches will also be utilised in the research and drafting of this paper. In particular, a case study will be conducted on the JPEX scandal. Finally, whether the cryptocurrency regulation framework which has been put in place achieves its ostensible goals, and those of regulation of a sector more generally will be analysed. Therefore, a deeper form of analysis other than mere description of the law here can be provided.

The starting point for this discussion over the JPEX scandal, and over the way in which the authorities in Hong Kong have been able to deal with this, must be with a discussion over the framework of regulation which has now been put in place to govern digital assets such as cryptocurrencies in Hong Kong.

As has already been noted, this particular form of digital assets are a relatively new technological development. Cryptocurrencies have only really been in the public sphere for around a decade or so (whilst Bitcoin was developed in late 2008 or 2009, it only really obtained prominence in the public and became more widely traded after 2010 when the world’s first crypto-exchanges were developed allowing people to trade these on a market which tracked a price or value for the assets) (Swammy et al., 2018, p. 17). Similarly, other popular cryptocurrencies (so-called “altcoins”) built on different blockchains such as Ethereum, have only been created in the more recent past (Swammy et al., 2018, p. 17).

All of this, and the rather unique nature of these coins as existing only in a digital form has led to questions around the world being asked as to what the legal status of these assets are. The lack of regulatory clarity here is not helped by the fact that these digital assets typically play a number of roles or use cases. For example, perhaps the most obvious use of a digital asset such as bitcoin might be to consider it a medium of payment, such as a currency (Bauer et al., 2018, p. 178). This section will now examine the possible arguments which can be used when identifying virtual assets as a form of property, which are derived from their use as virtual crypto-currencies by users, by their utility in the form of smart contract operations, both of which support assertions that virtual assets ought to be capable of being regarded as “property.”

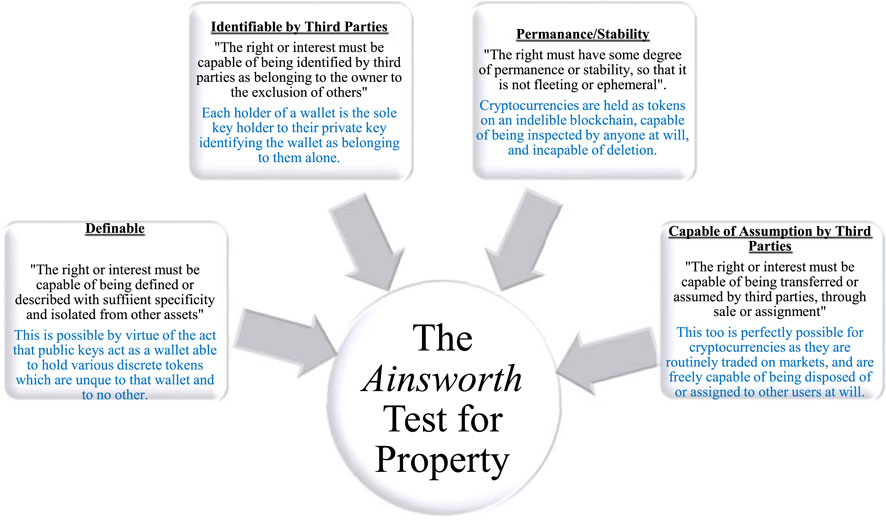

Before analysing these arguments however, it is first necessary to establish what is meant by the term “property” itself under the law in Hong Kong. As will be seen in Section 3.2 below, the term “property” is accepted as being legally defined according to the Ainsworth test, set out at common law by the House of Lords in National Provincial Bank Ltd. v Ainsworth (National Provincial Bank Ltd. v Ainsworth, 1965). The Ainsworth case identified that in order for any matter to be recognised as “property” it must be capable of being, firstly, definable, secondly, identifiable by third parties, thirdly capable of being or having its rights assumed by third parties. Fourth, and finally, the matter in question must have some degree of permanence or stability (National Provincial Bank Ltd. v Ainsworth, 1965). The law in Hong Kong has had this applied to the question of cryptocurrency in the Gatecoin case where the nature of the cryptocurrency user’s private key was regarded as being analogous to that of a PIN number or password [Re Gatecoin Limited (In Liquidation), 2023]. As such, and as will be seen below, it was accepted that virtual assets such as cryptocurrency (but also potentially other forms of virtual assets too) could be regarded as being “property” in the law of Hong Kong, and for their owners and holders to have certain rights over that property.

Why is it that virtual assets are required to be recognised as property? The reason, in short, is that a range of virtual assets have increasingly valuable uses and valuations, and their users therefore require a degree of legal certainty as to their rights and obligations in respect of contracts involving these assets. Virtual assets, for example, are often used as “cryptocurrencies” and are used in some instances to purchase goods and services, akin to the way in which “money” is used. This leads it to be necessary to assess whether virtual assets can be considered a form of “money” as well as being a form of property per se.

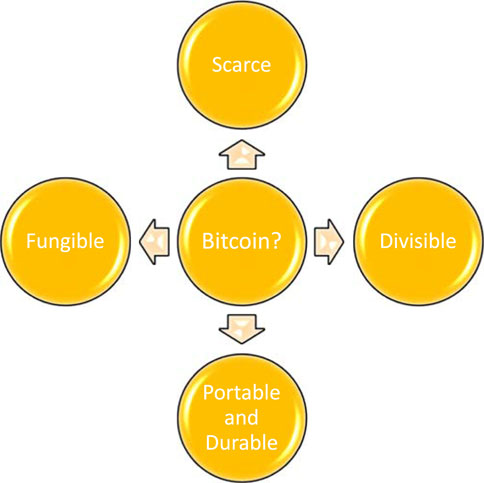

The issue here then is whether virtual assets such as cryptocurrencies can be seen as a form of “currency.” After all, these digital assets are commonly referred to as being “cryptocurrencies” because they have historically been used as such. Currency, in the form of “money” is described by some such as Clarke typically has a number of attributes which it needs to be able to perform that role (Clarke, 2020, p. 7). These attributes may be described briefly as being, divisibility (the currency needs to be able to be divided into smaller sub-units for pricing purposes and utility), fungibility (so that each unit is capable of free exchange with any other of the same value), it must be scarce and incapable of reproduction of forgery, portable and durable as seen in the diagram in Figure 1 (Clarke, 2020).

Figure 1. The aspects of a currency (Clarke, 2020).

Seen from the perspective of the attributes which are set out in the graphic above, it is certainly possible to consider Bitcoin capable of being able to perform the role of a currency. Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies, are typically divisible into various fractions of a coin or token, they are fungible, scarce, as a result of their coding, being needed to be mined for new tokens to be issued and quite often have a “hard cap” coded into the blockchain; there will never be more than 21 million total bitcoin tokens ever minted, for example, (Maurushat and Halpin, 2022, p. 242).

Furthermore, there is nothing necessarily which says that a currency is required to be sanctioned by a state, or published by a central bank or the Government in order to operate as currency (although defining it as being legal tender in a given state is of course a different matter) (Maurushat and Halpin, 2022). In fact, various forms of currency, both state sanctioned and unsanctioned, are commonly used by people all around the world in their various transactions. In some states such as in Argentina, where inflation is high and the currency volatile or weak, it is common for traders to want to accept only some foreign currency also widely available where possible, such as the United States Dollar (USD) (Lewis, 2022). Traders engaged in commercial cross-border transactions routinely select a currency to denominate the value of their transaction in and in which payment is required to be made. The law of contract, in Hong Kong, as well as in other states, routinely allows parties the necessary freedom of contract and party autonomy to be able to select a given transaction in this manner. It is quite feasible therefore to see bitcoin as a form of property in the form of money.

At the same time, others have suggested that digital assets lack the required durability and acceptance amongst the public to operate as effective currencies, and, even more convincingly, that they do not operate as a sufficient store of value because of their wildly volatile prices meaning that people typically do not want to give up their tokens to purchase services and goods because they fear that their tokens would still appreciate massively in value at some point in the near future making such a transaction unwise (Lewis, 2022). Anecdotes are still common in the cryptocurrency community regarding early adopters who bought pizza for 10,000 bitcoin, for example, which at its present value constitutes a value around $3.8 billion USD (Lewis, 2022). These concerns have led to digital assets being considered by their proponents (or opponents) as being other forms of property, such as being stores of value (akin to digital gold, for example,), commodities, or even utilities such as gas or oil because of the attributes which some coins have which allow them to perform certain functions; this is particularly so since the launch of Ethereum whereby instructions can be inscribed onto what is called the “Ethereum Virtual Machine” (or EVM, although there are now alternative smart contract platforms or blockchains in existence) which allow so-called “smart contracts” to be arranged.

A smart contract is a self-executing contract, which operates autonomously once it is agreed, and which will result in the automatic transfer of given assets from one address to another, or for some other pre-arranged result to occur once parameters are sufficiently met according to the programming of that contract (Verstappen, 2023). These autonomous contracts have been regarded as having the potential to significantly benefit trade and commerce by removing counter-party risk, because they are incapable of being stopped, frustrated, or avoided by a party once their obligations are agreed upon. In other words, if performance of the contractual obligation in question is performed by the other party, payment is guaranteed and operates according to cryptography, not upon the goodwill of the other party (Verstappen, 2023). Potentially, this may reduce the need for settlement, or clearing of transactions across borders, allowing instantaneous settlement without the need for intermediary clearing houses. The self-executing nature of these contracts also means that they appear to be largely autonomous, and ought not to require enforcement in a court of law.

In order to perform these roles however, and to provide commerce with a potentially highly efficient tool or medium through which it can achieve its aims and objectives, some clarity or understanding of the legal nature of these assets themselves must be provided by the state. After all, parties might be wary of transacting in a currency which has no legal status, and which cannot be enforced if necessary by a court. Likewise, parties might wish to be assured that they have some recourse in the event of fraud, or theft of their digital assets. Given that offences such as “theft” [under the Theft Ordinance (Cap 210)] requires a person to dishonestly appropriate “property” belonging to another, with an intention to permanently deprive them of it (Theft Ordinance, Cap 210, s.9), it stands to reason that in order to be able to commit that offence with digital assets such as crypto-currencies, these assets must indeed be capable of being classed as “property” in the first place.

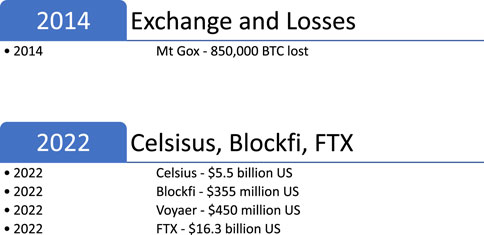

Finally, another pressing concern for the use and recognition of virtual assets as property is to ensure that the users and holders of these forms of property are afforded some form of protection in the event of abuse or loss. For institutions such as banks, which are typically placed under a number of prudential rules related to the capital levels which they hold and the type of debt and assets which they are required to hold in certain types or forms (such as a requirement to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets able to cover at least 1 month of their funding requirements under the Basel IV Accords, which will come into force in Hong Kong in January 2025) (KPMG, 2024) then it is also necessary to know legally, what classification digital assets are, before they could be held in any real number or as a speculative asset. Finally, given the nature of cryptocurrency, and considering the number of scandals and failures which have occurred with cryptocurrency exchanges such as the FTX scandal, or the Celsius and Blockfi insolvencies in 2022, or the collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014 (in which investors lost some 850,000 Bitcoin in total), investors in digital assets who have stored or deposit these assets online with these companies, in order to earn interest or provide liquidity, might also wish to be reassured that they own “property” with which normal rights as creditors, for example, are capable of being attached to (Witzig and Salomon, 2019, p. 34).

The consequences of exchange losses due to collapses and business failure are potentially vast for investors, as indicated by Figure 2, which shows the consequences of failure of these central digital asset platforms.

Figure 2. Timeline of Major Cryptocurrency Exchange Collapses and losses (Witzig and Salomon, 2019).

Given, as noted, that these digital assets are a new phenomenon, upon their introduction and use, there was not, in Hong Kong, nor in any other state, any real understanding or specific bespoke legal regime which could be said to apply to digital assets which could ensure that they were initially classified as being “property.” Fortunately however, there has now been some effort made to clarify this, both in Hong Kong, and in some other states such as in the UK (UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, 2024). In Hong Kong, for example, the Government, in the form of the Financial Services and Treasury Bureau have indicated an intention to accept the recognition of virtual digital assets as a form of property, and that the government wished to “calibrate” its legal and regulatory regime in order to facilitate and encourage the wider use and adoption of such virtual assets (Government of Hong Kong and Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau, 2022). This statement of intent has been a particularly progressive one compared to the apparent distrust or antipathy seen in other jurisdictions to the potentially disrupting nature of virtual assets, and has led to some to suggest that Hong Kong might be able to develop as a future hub of crypto and virtual asset development (Ng, 2023). Hong Kong, which is looking to try and develop a niche for itself following something of a loss of prominence in terms of its financial centre compared to other mainland Chinese financial centres such as in Shanghai, may be uniquely well placed to prosper from and capitalise on a coming virtual asset revolution, as it has a high-tech savvy, well-educated labour force, deep capital pools, and, perhaps most importantly, regulatory autonomy on a scale which no other Chinese special administrative or autonomous region enjoys under the Hong Kong Basic Law, meaning that it can take its own steps as a region to administer and welcome the use of virtual assets irrespective of the general approach which the authorities in China more generally take (Droulers, 2023). It is, for example, notable at the present time that trading in virtual assets is presently banned in China, in line with the principles of the socialist system enforced and contained in the Chinese Constitution itself. Hong Kong’s special status as being part of China, but retaining its own common-law and capitalist model under the Basic Law for Hong Kong, and under the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 provides the region with both flexibility to take advantage of new technologies and developments such as that of blockchain technology and its associated virtual or crypto-assets, whilst also allowing the state to operate as something of a bridge between the rest of the world and China itself (Droulers, 2023).

The chance for Hong Kong to develop itself as a key hub and global player in this area is also highlighted by the fact that many other states which could otherwise be well placed to capitalise on this trend are presently unwilling to do so for political or economic reasons. The United States is one good example, where the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been taking something of a hard-line to virtual assets (SEC, 2024). This has been through suggesting that virtually all virtual asset other than bitcoin may constitute unlicensed securities (SEC, 2024) in contravention of the Securities Exchanges Act of 1934 (Securities and Exchanges Act, 1934), have been suggested to be at risk of losing out on the race to the front of the development of these assets as developers seek more welcoming jurisdictions to operate from (Reuters, 2024). If Hong Kong is to profit from the unwillingness and tardiness of other competing jurisdictions and develop the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) as a leading hub in the future for the development and use of virtual assets, and, thus, global commerce fuelled by such virtual assets, it must be a priority to develop a regulatory framework for these assets, and to establish first and foremost a classification of these assets as being a form of “property” with which the holders of which can ensure their property rights are protected.

In Hong Kong, the question of whether digital assets can constitute money has now been determined upon by a decision of the courts in a decision which was perfectly aligned with the stated objectives and intention of the Government noted above. This was seen in the form of the Court of First Instance of Hong Kong and its decision in Re Gatecoin Limited (in liquidation) (HKCFI, 2023). The Gatecoin case was a case arising from the development, and eventual collapse of, another cryptocurrency exchange, this time one based in Hong Kong itself. Gatecoin, a virtual asset platform and crypto-currency exchange was founded in 2015, and allowed its users to trade and exchange some forty-five of its listed virtual asset tokens hosted upon it. In order to do so, users would upload traditional, fiat currencies to the site to create liquidity, and would then purchase holdings which they could store as crypto-tokens in their wallets hosted by the site, or change or exchange these for other currencies or indeed other crypto-tokens, allowing instantaneous live trading of these assets to take place (Siu et al., 2023). In order to ensure liquidity was available for these trades, the exchange itself was of course required to purchase its own stocks of these assets from the global market, and price volatility ultimately meant that in 2019 the company was insolvent, and liquidators appointed. It was estimated that the value of the cryptocurrencies held by Gatecoin upon their insolvency was around $140 million HK at the time (Philipps and Sharman, 2024). The company’s liquidators were able to secure the crypto-assets held by Gatecoin and hosted on their website by October of 2022, but were challenged by Gatecoin’s creditors, many of whom argued that the assets hosted on the site held in their own wallets were not deposits, or held by Gatecoin on trust for them, but were in fact their own property which ought not to form part of Gatecoin’s assets available for distribution in general under the principles of insolvency law. In order to be able to distribute the assets of the company to its creditors (the majority of retail investors who held their tokens in Gatecoin’s hosted wallets would be recognised as unsecured creditors if they were to be considered creditors in the first place) (Philipps and Sharman, 2024). The liquidators therefore applied to the court under s200 (3) of the (Companies Ordinance Cap 32, 2023), for directions in respect of the characterisation of the assets held by the company, and to the allocation of such assets to the creditors [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation) (2023)].

The application brought by the liquidators to the Court of First Instance here was the first real legal test of Hong Kong’s regulatory and legal regime and whether it would be able to fulfil the hopes which the Financial Services and Treasury Bureau have publicly stated to hold in respect of Hong Kong’s potential to be a virtual asset hub (Government of Hong Kong and Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau, 2022). The clarity and simplicity of the judgment in Re Gatecoin makes it clear that the courts have passed this first, essential test, as it is now the case that it virtual assets in Hong Kong are certainly capable of being considered “property” and can therefore be held on trust, opening up a range of new possibilities and uses for companies and individuals operating in Hong Kong to use these assets in the future (Leung H. T., 2024). What is more is that the court was able to reach such a determination without there being a need for the introduction of any new, crypto-specific rules or statutes, based on the law as it stands in Hong Kong at the present time, indicating that the law is already sufficiently flexible to be used to apply to this relatively new class of assets.

The Court in Re Gatecoin identified that the legal test for what “property” is was not set out in any legislative statute; even the Interpretation and General Clause Ordnance (Cap 1) intended to provide guidance and interpretation on the law in Hong Kong was incapable of performing this, because it only provides for a broad and general definition of property rather than to provide a legal test for it [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation) (2023)]. In the absence of any existing statutory provisions however, the Court was able to identify that the common law had already set out a four-stage test for the determination of whether a given thing had the characteristic of “property” or not in the case of National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth [(1965) AC 1175]. The House of Lords in Ainsworth held that in order to be property, something was required to be, firstly, capable of definition, secondly, for it to be identifiable by the parties in question, thirdly, for it to be capable in its nature of assumption by the parties, and finally, for the thing to have some degree of permanence or stability [(1965) AC 1175].

Once this had been identified as the proper test for the determination of a thing as “property”, the court in Re Gatecoin went on to assess the various characteristics of virtual assets against this. Clearly, it was held, that crypto-assets such as coins were capable of being both defined and identified by the parties because of the fact that different tokens existed and were held in different wallets to which different owners held the private keys of [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation) (2023)]. It was also the case that these assets were indeed capable of being “assumed” by different users, as they were capable of being traded on markets, held in different wallets to which only the owner had the private key to access, and were generally respected by parties themselves in the trade as being things which ownership rights existed in respect of. Finally, it was also accepted by the court that the property in the form of crypto assets also had permanence and stability because of the very nature of the indelible and permanent nature of the blockchain which cannot be altered retrospectively, and which is incapable of being stopped or destroyed [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation) (2023)]. Each transaction can furthermore be inspected by anyone on the blockchain providing an additional degree of permanence, stability, and helping parties to be able to identify more readily this form of property [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation) (2023)]. This can be seen by considering the Ainsworth test and its requirement against the nature of cryptocurrencies hosted on a blockchain in the diagram below.

After identifying that the cryptocurrencies held in wallets hosted by Gatecoin Limited were indeed forms of “property” under the test in Ainsworth (Figure 3), the court next had to determine how this property ought to be distributed. The court held that the property could not have been considered to have been the subject of an express trust, held in favour of the creditors, as none of the so-called “three certainties” required by trust law were met (Siu et al., 2023). Difficulty in particular here arose over certainty of intention, as the contractual disclaimer entered into by customers of Gatecoin and the site itself expressly declaimed any sort of fiduciary relationship existing between the company and its customers. Whilst a trust might have been established here on the basis that these currencies were intangible even if held in bulk as in Hunter v Moss (1994), and whilst there may have been a Quistclose trust created in respect of some creditors whose funds had been borrowed for a specific purpose to purchase certain assets (Barclays Bank Ltd. v Quistclose Investments Ltd., 1968), it could not be said for the majority of customers that the company held the funds in the customer accounts on trust for these customers. As such, the result was that the company owed these individuals the sum or value of their holdings, and as a result that the customers were (unsecured) creditors [Re Gatecoin Limited (in Liquidation), 2023]. Again, just as with the determination of whether or not virtual assets such as crypto-currencies could be considered “property” which was determined under established and well-known principles of the common law, it was also the case that the court was able to dispose of the liquidator’s request for declaration as to how the assets of the company in liquidation were to be disposed of by simply applying the well-known rules of trust law and insolvency law to the facts. That the common law was able to satisfactorily dispose of the case in this way, despite the novelty of an entirely new class of assets having been developed, highlights the great flexibility this model of law embodies, and bodes well for Hong Kong’s claims an ambitions to develop as a hub for virtual assets in the future.

Figure 3. The Ainsworth Test for “Property” as applied to cryptocurrencies (Siu et al., 2023).

The application of the Ainsworth test for “property” to the facts of the Gatecoin case, and by extension, to various classes of virtual assets has therefore provided significant and vitally important certainty to the law in Hong Kong, as well as in other common law countries such as the UK where the Jurisdiction Taskforce headed by a senior judge in the form of the Master of the Rolls Sir Geoffrey Vos had already declared virtual assets as having the quality of property, and where the decision of the Hong Kong Court of First Instance might be persuasive as an authority for other courts (UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, 2024). Similarly, it has also been held in another common law court, in New Zealand, in Ruscoe v Cryptopia by the High Court of New Zealand that crypto assets are indeed capable of being recognised as “property” by the common law, and this was in fact a judgment which was acknowledged as being persuasive by the Hong Kong Court of First Instance in the Gatecoin case itself [Ruscoe v Cryptopia (2020)].

The ease with which the common law therefore, and the test in Ainsworth can be applied to virtual assets such as cryptocurrencies is a key plank in the region’s ambitions to develop Hong Kong as a hub for the development of blockchain technology in the future. By providing certainty and legal and regulatory clarity in this way, developers might decide that they can launch a coin, or an exchange in Hong Kong, safe in the knowledge that their property rights will be protected.

In short, if the Gatecoin case was a test for Hong Kong’s ambitions to develop as a crypto and virtual asset hub of the future as has been suggested here, then the common law, and the provisions of Hong Kong Basic Law in the (Companies Ordinance Cap 32, 2023) might be said to have passed this test with flying colours (Companies Ordinance Cap 32, 2023). The next section of this paper will assess the extent to which the same can be said of the new virtual asset specific legislative and regulatory framework which has been recently put in place in Hong Kong in pursuit of these objectives (Choy, 2023). As will be seen, these provisions have already been tested and come under stain from another of the now seemingly regular cryptocurrency scandals which have befallen this industry, in the so-called JPEX scandal. This will now be considered further.

As part of Hong Kong’s ambitions to ensure the region becomes a leading hub for the developing virtual asset industry around the world, the state has recently introduced a comprehensive regulatory framework for the licensing of exchanges, whilst seeking to ensure that the state’s obligations in respect of its anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) obligations (Hong Kong is a member of the Financial Action Task Force or FATF, and as such, is obliged to implement the FATF’s published anti-money laundering recommendations) (Government of Hong Kong, 2023). These rules seek to both facilitate the development of virtual asset exchanges and to encourage them to be launched within the state; many (including the now notorious FTX, which was launched by the now incarcerated Sam Bankman-Fried in Hong Kong in 2019 before subsequently relocating the company to the Bahamas) (Ng, 2023) but, at the same time, to ensure that operators within the jurisdiction comply with the AML-CTF provisions and statutory requirements set out in the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (AMLO). This new regulatory regime partners the finding of the Hong Kong courts in Re Gatecoin Limited which has already provided some degree of certainty and clarity as to the “property” status of virtual currencies in Hong Kong. However, as will now be seen, this new regime has already come under scrutiny, and there have been questions asked as to whether the regulatory framework is able to properly govern new models of entity such as decentralised autonomous organisations (or DAOs), a form of unincorporated association of individuals who hold so-called “governance” tokens in the form of virtual assets and who together vote on the DAO’s course of action to run it in a manner somewhat similar to shareholders of an incorporated company. The difference with the way in which a DAO operates compared to a company notwithstanding the fact that a DAO is not incorporated and thus lacks any distinct legal personality of its own, unlike a company [Salomon v A Salomon and Co. Ltd. (1897)] is that the DAO does not have a centralised board of directors which set its strategy or run the organisation on a day-to-day basis. Instead, the DAO and its activities are voted on democratically by all of its members, albeit with voting rights determined by the number of tokens staked by a given individual or organisation (Walsh and Kong, 2024). Quite how well regulated these entities are under the law in Hong Kong is an issue which must be assessed here.

Before assessing the law as it applies to DAOs in particular however, it is necessary to set out and to analyse the new regulatory framework which has been introduced in Hong Kong over the past few years. The Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (Amendment) Ordinance 2022 (Amendment Ordinance) introduced these reforms into Hong Kong law, including the addition of Part 5B to the AMLO, which establishes a licensing regime for virtual asset service providers (VASPs).

The rules in the new Ordinance now create a statutory definition of “virtual assets” (or VAs). This definition provides that VAs are as being a “cryptographically secured digital representation of value” as long as this is “expressed as a unit of account or store of value” [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZR (1)]. Section 53ZR, which creates this definition is not inconsistent with the decision in Re Gatecoin, as it goes on to provide that in addition to these characteristics, the virtual asset (to be defined as such) must also be intended to be used as a medium of exchange (as most cryptocurrencies appear at least on their face to be), or to provide rights such as a right to vote on management, governance or the affairs of any arrangement related to cryptographically secured digital representations of value (in other words, DAO governance tokens). The law also acknowledges the importance of recognizing virtual assets as “property” by incorporating principles similar to the Ainsworth criteria, emphasizing that these assets must be capable of being transferred, stored, or traded electronically as part of their legal classification under the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615 (2022).

This is a comprehensive definition which has been given in law here to ensure that the widest possible range of virtual assets and digital currencies are capable of falling within the scope of the Act. The inclusion of a specific provision which appears intended to ensure that governance tokens for DAOs are definitively capable of being considered “virtual assets” for the purpose of the Act indicates a degree of familiarity and technical competence on the part of the legislature here which is to be commended. As will be seen, this is also vitally important in the way in which the new regulatory regime appears to interact with the regulation of DAOs themselves.

This is intended not only to catch within it virtual asset platforms such as cryptocurrency exchanges themselves, but also those which are intended to allow so-called “peer-to-peer” transactions whereby parties agree to transfer or swap virtual assets such as cryptocurrencies between themselves either in return for alternative currencies or indeed, FIAT currency. Peer to peer exchanges have been a matter of some concern for regulators around the world because they are perceived as increasing the risk of money laundering; whilst an exchange might engage in “know-your-customer” responsibilities, another exchange user, once introduced to a customer of their own, is unlikely to be under any real pressure to engage in such, or to report accurately their transactions, and are unlikely to be investigated by regulators or the criminal agencies of their state (Madan and Moray, 2024, p. 187). Hong Kong’s intention to regulate this sector however, in the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance appears to attempt to regulate this by imposing obligations of licensing, and thus subsequently, obligations to ensure customer due-diligence, suspicious activity reporting, and other typical anti-money laundering protocols such as those set out in the FATF’s recommendations to those customers, including those it introduces to each other via a peer-to-peer platform. At the same time however, the scope of the Ordinance clearly only covers exchanges here and goes as far as ensuring that licenses are obtained by those exchanges introducing users to meet each other or to engaging in contracting in a peer-to-peer manner. The Ordinance does not however, cover those individuals engaged in peer-to-peer transactions themselves, nor those transferring crypto-assets to one another without the use of the regulated exchange as an intermediary. In other words, the Ordinance does not apply to any over-the-counter (OTC) exchanges as long as neither tokens nor the funds for the acquisition itself are handled by the exchange in question (Choy, 2023).

Following the determination by the new s53ZR of what virtual assets are, the new law then goes on to provide in s53ZRD that in order to carry on a business providing any VA service, or to hold oneself out as so doing, a license is required [Choy, 2023, s53ZRD (1)]. Doing so, or performing any other regulated function in respect of virtual assets constitutes a criminal offence under s53ZRD (4) and (5) allowing serious criminal penalties to follow upon conviction [Choy, 2023, s53ZRD (4) (5)]. Regulated activities meanwhile, and “VA services” are also defined in s53ZRB and in Schedule 3B of the Ordinance in an extremely wide manner, and include any person either carrying on business as such (itself a rather straightforward and relatively narrow provision) but also any person or corporation performing a VA service on behalf of another (an agent) or any person or corporation licensed to perform VA services. Under Schedule 3B to the Ordinance meanwhile, specific VA services are expressly defined and include, amongst other things, any service where a party offers to either purchase or sell virtual assets for another in a way which results in a binding transaction (any platform which allows for contracts for the purchase or sale of virtual assets in a manner which creates a binding legal contract therefore) but also any such service which merely “regularly introduces” parties to one another in such a way to allow them to conclude such transactions on their own behalf [Choy, 2023, Schedule 3B para 1 (a) (i) (ii)]. In order to for these virtual asset service providers (crypto-exchanges) to obtain a license for the performance of virtual asset service provision meanwhile, it is necessary for them not only to be a company incorporated in Hong Kong, or to have a business registration certificate for it issued in Hong Kong (Choy, 2023, s53ZR), but it is also necessary for the virtual asset service provider to be able to pass a “fit and proper” test under Subdivision 2 s53ZRJ of the Ordinance (Choy, 2023, Subdivision 2 s53ZRJ).

This requires that the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) to determine, before granting a license to provide virtual asset services, that the body making an application for the license is a fit and proper one (Choy, 2023, Subdivision 2 s53ZRJ). Factors taken into account here include a range of matters designed to ensure that the risk of failure by the organisation, and thus, harm being done to its investors just as has occurred with failed crypto-exchanges all over the world from FTX to Gatecoin, is minimised. Thus, the Commission is likely to take into account the overall financial position and solvency of those seeking the license, their education and qualifications, their ability to provide these services competently, honestly, and fairly, and their reputation, including whether or not any relevant criminal offences have been committed by the individual (by assessing their previous convictions) [Choy, 2023, s53ZRJ (1) (a)-(d)]. In addition to this is the fact that the Ordinance requires each licensed provider of virtual assets to nominate at least two individuals (one of whom must be an executive director of the licensee) who are regarded by law as being “responsible officers” of the company, requires that reasonable officer to be subject to licensing approval by the SFC [Choy, 2023, s53ZRP (1)]. The Commission must refuse this license unless it is satisfied that the applicant is a fit and proper person to be approved as a responsible officer [Choy, 2023, s53ZRP (1)].

This is sufficiently wide to give the Commission a degree of latitude in their investigations to ensure that the individual is not suffering from any compromise, such as owing debts to others, being otherwise impecunious, or under pressure from other sources which might compromise their ability to perform their services fairly and with integrity. Any person who does perform the carrying out of virtual asset services as defined in the Ordinance without a license, or who holds out that they hold a license to do so when they do not, also commits a criminal offence under the Ordinance (Choy, 2023). This licensing regime is a mechanism which seeks to introduce a degree of accountability into the virtual asset platform world, at least as far as it operates in Hong Kong. As has been seen, there have been a wide number of scandals and collapses of virtual asset providers around the world, from JPEX to FTX; many of these have, to some extent, been due to a failure of certain individuals within the organisation involved to display proper processes or caution. In the FTX collapse and subsequent investigations, for example, it has been alleged that the Chief Executive Officer, Sam Bankman-Freid, along with other executives of the organisation, simply lacked the experience, expertise and skill required to run such a large organisation (Hansen and Komprozos-Athanasiou, 2024). This led to failures such as those allowing individuals to mix client funds with company assets, resulting in significant loss to investors. It is arguable that a fit and proper persons test, included as part of a general licensing requirement such as that now in force in Hong Kong, might well have identified that these individuals were unfit for such operations and would thus have denied a license to the firm until such time as a more qualified and experienced group of responsible officers were put forward. This is one important element of the Hong Kong licensing regime.

Other provisions under the AMLO addressing virtual assets include measures to combat fraudulent practices, such as Section 53ZRF(1), which criminalizes deceptive schemes in virtual asset transactions making it a specific offence for any person directly or indirectly, in a transaction involving virtual assets, to employ any scheme or device with the intent to defraud or deceive or to engage in any business practice or course of action which is fraudulent or deceptive or which would constitute a fraud (Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZRF). There is some doubt that this provision was one which was strictly necessary; after all, once it is established that virtual assets constitute “property” as they do in Hong Kong law, it subsequently becomes perfectly possible for other existing offences such as those in the Theft Ordinance (Cap 210) such as offences of theft or fraud to apply perfectly well to transactions involving virtual assets, just as it would otherwise apply to transactions involving more traditional asset classes. Nevertheless, the focus of the Hong Kong legislature here has been to seek to ensure that there is a comprehensive system of regulation put in place in respect of virtual assets, and that therefore no proverbial stone was left unturned or overlooked when it comes to creating such a regime. Certainly, the introduction of a specific crypto-specific prohibition on engaging in fraudulent or deceptive transactions might be regarded as being helpful and beneficial for the purposes of ensuring legal certainty, and, thus, in increasing confidence in the market for investors (Wan, 2023). This would again align with the Government’s stated intention and policy goals of creating a productive regulatory environment for which the new virtual asset industry might begin to establish itself in Hong Kong.

Another key provision of the AMLO is Section 53ZRG(1), which prohibits fraudulent or reckless misrepresentations to induce virtual asset transactions which creates an offence for those who make any fraudulent misrepresentation or reckless misrepresentation for the purpose of inducing another to enter into, offer for, to acquire, dispose of and so on, virtual assets (Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZRG). This is a significant change for the law here and ought to help encourage the protection of retail customers not only from misleading advertisements, but also, to a degree, to protect them from market manipulation. Another key concern which has been raised about the way in which the world’s crypto-markets operate is that in the most part, these markets remain unregulated and thus free from many of the insider dealing and market manipulation or market abuse rules which exist in respect to traditional securities and equities dealing (Li et al., 2024). Existing legal rules on contractual misrepresentation may help protect individuals from being misled by crypto-exchanges that sell tokens directly to users through advertisements or statements they knew or should have known were false. However, the introduction of a specific criminal offense extends beyond direct sellers to cover anyone making such misrepresentations “for the purpose of inducing another person” to engage in a transaction for virtual assets. This provision may also apply to fraudulent market practices such as speculative market rigging, spoofing, or misleading investors into purchasing virtual assets that are largely controlled by a few major holders (“whales”). These individuals often manipulate the market by timing the sale of their undisclosed holdings at peak prices, triggering a market crash and leaving investors with significant losses (Li W. et al., 2024).

As can be seen from the above, these provisions represent a comprehensive attempt to regulate the provision of virtual asset services in Hong Kong and to protect retail investors from the potential harm which might be caused by fraudulent or deceptive behaviour. Kyles (2022), p.121 suggests that the risk of crypto-exchanges committing money-laundering facilitation offenses ought, theoretically, to be reduced too by these regulatory changes which have stemmed from an acknowledgement as was noted in the first part of this paper that crypto-assets are indeed “property” and can and should be treated legally as requiring the same sort of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing care and due diligence to be taken by intermediaries such as virtual asset service providers therefore.

The imposition of these rules is accompanied by the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (AMLO) vesting an oversight role in the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) under Section 53ZRB(1). This empowers the SFC to enforce compliance with the regulatory framework. As will be seen, this has allowed for the Ordinance and its new rules to be provided with a degree of regulatory enforcement. Indeed, even prior to the Hong Kong Police’s arrest of JPEX executives and their seizure of assets held by the firm, the SFC had already issued warnings over the firm and its operations suggesting that the offering for sale of digital assets on its own virtual asset platform was now incompatible with the new regulatory framework in force in Hong Kong.

The SFC is granted specific powers under Section 3.1 of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (Cap 615) to either publicly reprimand an institution (such as JPEX) contravening of the Ordinance and its rules, to order that institution to take certain remedial action, or to order the institution to pay a fine up to a limit of $10,000,000 HK or a sum three times the amount of profit gained or costs avoided by the institution resulting from them contravening the Ordinance in the first place [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s21 (2)]. The SFC does therefore have a clearly defined role in the regulation of the sector. Additionally, as provided for in Part 2 of the Ordinance, the SFC and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority are both provided with the right to publish guidance and guidelines as it considers appropriate, including on how relevant penalties are to be calculated [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s21 (2)]. There are in fact a number of different guidelines which the SFC has published. One of these in recent years has been its guidelines published in 2023 on Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Financing of Terrorism (Securities and Futures Commission, 2023). This Code, which applies to licensed entities (i.e., those which have successfully applied for and received a license to provide virtual asset services under the Ordinance by the SFC) provides guidance on such entities on how to pursue customer due diligence, its record-keeping requirements, staff training, wire-transfer procedures, and so on (Securities and Futures Commission, 2023). Further, specific guidance is provided for virtual asset providers on best practices to prevent virtual assets such as crypto-currencies being used in money laundering or the financing of terrorism in Chapter 12 of the Guidelines (Securities and Futures Commission, 2023, Chapter 12). After setting out the crypto-specific risks of money laundering which the use of pseudo-anonymous coins provide, the Guidelines suggest that holistic efforts ought to be made to identify risks, by identifying the regulatory jurisdiction governing their clients (some countries provide for greater risks than others, for example,) but also by identifying the particular risks of the virtual asset in question; it is provided that matters such as the market capitalisation of the coin, its price volatility, its trading volume and so on are all matters which might require proportional risk-measures to be taken (Securities and Futures Commission, 2023). The emphasis is very much on ensuring that proportionate risk-mitigation measures be taken by virtual asset service providers, and the guidance is useful in that it helps to identify what matters ought to be taken into account in any given situation so that these risks can be more readily identified.

A key limitation of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (AMLO) is its exclusion of certain activities, such as unregulated over-the-counter (OTC) transactions, from its scope. Instead, these are left to market participants who it appears to be assumed are capable of protecting themselves unlike general retail customers who are likely to be interacting with these virtual asset service providers. Overall, the regulatory framework established by the AMLO appears sufficient to enhance industry certainty and bolster confidence among users of licensed virtual asset providers who are now licensed in Hong Kong. This will however naturally require some oversight from the SFC, to further ensure confidence in the regulatory regime as time goes on (Securities and Futures Commission, 2023). It seems here that the SFC is wasting little time here in enforcing these new rules however. The JPEX Scandal has already provided a significant test to the new regulatory regime as will now be seen.

In September 2023, just some 6 months or so after the coming into force of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance was amended to introduce this new regulatory framework for virtual assets in Hong Kong law, reports circulated that the SFC and the police in Hong Kong were investigating allegations of fraud being committed by the virtual asset trading platform JPEX (Guinto and Yip, 2023). The investigation was sparked by reports from investors who complained that the Dubai-based exchange JPEX had been advertising in Hong Kong encouraging investors in Hong Kong to purchase virtual asset tokens with the firm; these advertising efforts were assisted by a so-called social media influencer in Hong Kong, Joseph Lam, who promised subscribers high-yields and profit, and suggested that the purchases could help investors buy a house, or grow their “social clout” (Guinto and Yip, 2023). The platform subsequently declared that they were suffering from a “liquidity shortage” and were unable to process user’s requests for withdrawals, raising concerns about the exchange’s solvency.

The SFC subsequently accused the platform of failure to comply with Hong Kong’s new regulatory framework. The main concerns for the SFC here were that JPEX was seeking, directly or indirectly, to carrying on a virtual asset service without a license in Hong Kong as required under s53ZRD (1) of the Ordinance [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZRD (1)]. Whilst JPEX asserted that they had applied for a license in Hong Kong, and had been licensed elsewhere, this was subsequently found to be untrue, and the SFC subsequently shut down several of the exchanges OTC shops. Whilst therefore it was suggested above that one of the weaknesses of the regulatory regime might have been that it did not cover all OTC transactions, the Ordinance does cover, as was noted, OTC transactions where the virtual asset provider is the party engaged in the introduction of parties here under Schedule 3B of the Ordinance (Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, Schedule 3B). On this occasion, this appears to have been sufficient to ensure that sufficient power was available to the SFC to shut down these OTC shops which were operating without a license in the jurisdiction (Drylewski et al., 2023).

By being able to establish that JPEX was operating in Hong Kong without a license, even though the company had been registered in another state, in the form of Dubai, and had been licensed in that state according to local law in Dubai, the fact that the SFC in Hong Kong was able to cease the operation of local shops and businesses operated by JPEX in Hong Kong under the new law helps to conceptualise the legal reach of the new licensing requirements. The JPEX case demonstrates that any business offering virtual asset services in Hong Kong, or to Hong Kong-based clients, must comply with the licensing regime under the AMLO. The SFC exercises significant control under Section 53ZRD(3)(a) to assess whether applicants are ‘fit and proper’ persons before granting licenses. This ought, theoretically at least, provide a greater degree of protection for users of virtual assets in Hong Kong, who can be reassured that those they are using to host their wallets or virtual assets have indeed been reviewed by the SFC and found competent and compliant with the law of Hong Kong. In turn, this ought to create confidence in the consumer and encourage adoption of this form of property, creating a virtuous cycle of adoption and use in the country in pursuit of the legislative’s stated aims of making Hong Kong a regional and global virtual asset hub.

Despite the SFC’s successful enforcement of the AMLO’s licensing regime in the JPEX case, critics argue that challenges persist due to the cross-border nature of virtual asset transactions, there have still been some suggestions from those such as Drylewski and others, that the regime faces a number of difficulties given the international, cross-border nature of the virtual asset industry and the way in which transactions are carried out in a delocalised manner from anywhere in the world [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s30 (3) (c)]. In particular, these critics suggest that there might be more difficulty in the future in the SFC enforcing these rules such as the licensing requirement because of the need, under s53ZRD (1) (a) to “carry on business” in Hong Kong, or to “actively market” their services within Hong Kong as provided for under s53ZRB (3)’s definition of ‘providing a VA service” sets out [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, ss53ZRD (1) (a), 53ZRB (3)]. Whilst it was the case that JPEX was clearly doing both in the country, through actively marketing on the Hong Kong metro, for example, and through its presence through its established OTC shops in the state, there may be more difficulty in the future here in asserting the jurisdiction of Hong Kong law especially as exchanges and virtual asset service providers based elsewhere in the world become more familiar with the provisions of the law.

It might, for example, be much more difficult in the future for the SFC to establish that a virtual asset service provider based elsewhere in the world was “actively marketing” in Hong Kong if they simply market elsewhere in the world through a viral-marketing technique, which is subsequently shared and repeated, or amplified by influencers in Hong Kong without their control or direction. The broad drafting of Sections 53ZRB(3) and 53ZRB(4) of the AMLO enables the ordinance to assert extraterritorial jurisdiction over virtual asset service providers (VASPs) operating outside Hong Kong but targeting local clients. It is provided, for example, here that “active marketing” is satisfied as long as a person’s “marketing of the specified service is to be regarded as holding itself, himself, or herself out as carrying on a business providing that VA service” [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZRB (4) (b)]. It is further provided in s53ZRB (5) (c) that this applies whether or not the “specified services are marketed in Hong Kong or from a place outside Hong Kong” [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, s53ZRB (5) (c)]. Under Schedule 3B of the AMLO, virtual asset service providers (VASPs) may be subject to Hong Kong’s licensing requirements even without direct marketing in the jurisdiction, provided they hold themselves out globally as offering regulated activities within the territory. Far from jurisdictional issues being a challenge here, it does seem, prima facie at least, that the Hong Kong legislature has empowered the SFC to target any virtual asset provider anywhere in the world. Naturally enough, actually enforcing those rules is likely to be difficult if the entity has no assets nor any presence in Hong Kong. Here however, the SFC seems content to be able to take action against these organisation’s subsidiaries within the region, as was seen in the SFC’s enforcement action taken against ETRADE Securities (Hong Kong) Ltd., a subsidiary of the US registered ETrade U.S. (Drylewski et al., 2023). This enforcement action was taken on the basis of the parent US company “actively marketing” into Hong Kong without a license, with the subsidiary company accused of aiding and abetting this activity; no action was actually taken against the entity committing the primary party committing the offence here, in the form of the US company, and only against the inchoate aider and abettor.

Another possible weakness with the law identified by Drylewski and others is the difficulty which is inherent in seeking to regulate so-called “DeFi” or decentralised finance applications; these are typically peer-to-peer operated with different participants taking it upon themselves to provide liquidity pools (in return for a reward generated by fees) without any human interaction. Instead, the whole process takes place through the application of autonomous self-enforcing and executing smart contracts (Drylewski et al., 2023). As noted above, the AMLO regulates virtual asset services provided through platforms interacting directly with the public or facilitating peer-to-peer transactions, as outlined in Schedule 3B. It is therefore fair to say that the absence of mechanisms designed to help to regulate DeFi represents one significant legal gap in Hong Kong’s regulatory framework.

A similar concern arises in respect of the legal status of DAO’s operating in Hong Kong. Here, it is unclear from the application of the Ordinance whether or not DAO tokens themselves are regulated by the Ordinance’s scope, and whether DAOs themselves are “virtual asset service providers” (Yan and Leung, 2024). In the JPEX Scandal, one of the matters which the SFC used to indict the company was that it had offered its user’s DAO governance tokens without a license; this was said to be part of the activity which constituted the provision of a virtual asset service provision within the territory and this seems straightforward enough. However, if these tokens are not offered by a centralised exchange in this manner, but instead distributed by other users in a more decentralised manner, peer-to-peer for example, it does not appear as though this distribution would be one capable of constituting the performance of a virtual asset service. The DAO itself however might still be recognised itself as performing these services, if it “offers to sell or purchase virtual assets” or, under Schedule 3B (1) (b) where client’s money or virtual assets are held directly or indirectly by the DAO [Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance Cap 615, 2022, Sch. 3B (1) (a) (b)]. It is certainly the case, for example, that a DAO does indeed hold money or virtual assets belonging to its token holders or members, in the form of DAO tokens itself, which are owned by its members. However, whether these members, who also run the DAO as a sort of virtual partnership, through smart contracts, are actually “clients” of the DAO, or its managers, remains legally unclear. There has not yet been any real case law on DAOs in the common law world, or in Hong Kong, which could help to clarify what the relationship of the DAO’s members to the organisation is itself, and whether in particular this form of organisation could ever be considered a “virtual asset service provider” which requires licensing to operate in Hong Kong. Nor is it clear how the SFC or any other regulatory agency could ever really be expected to practically regulate or police such activity. Of course, given the judgment in the Gatecoin case, it is nevertheless the case that these DAO tokens can be considered property, in the form of “securities” under the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap 571) (SFO) (Securities and Futures Ordinance, Cap 571), and this is something which the SFC has asserted is likely to be considered in the future here, given the analogy of these tokens as being akin to “stock” tokens, allowing members a vote on the way in which the organisation is run (Yan and Leung, 2024). This is indicative of the way in which the courts’ decisions in cases such as Gatecoin can be used to help to fill gaps and interpretive lacunae in the statutory regulation put into force by the legislature in Hong Kong. Ultimately however, more clarity is still required to be provided by either the legislature or by the courts in respect of what DAOs are legally, and how they can be regulated.

In conclusion, the Hong Kong legislature and the courts of Hong Kong ought to be commended in general terms for attempting to introduce a comprehensive regulatory framework for the regulation of virtual assets, and of virtual asset service providers within the region.

The courts of Hong Kong in Re Gatecoin have helped to clarify the understanding of virtual assets as being property under the law in Hong Kong. Combined with the creation of a consistent statutory definition of virtual assets in the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance. As a result, there is now a well understood and accepted identification of virtual assets as property, creating regulatory clarity. In turn, this will help to guarantee Hong Kong’s competitiveness as a hub for the development of virtual assets globally. As can be seen, there are two key strands to this model; the first is the identification and regulation of virtual assets conforming to the requirements of the Ainsworth test and the requirements of the Ordinance. The second is the pursuit of consumer protection by the licensing obligations of virtual asset platforms and providers and the creation of a range of offenses for those not conforming to these obligations.

In addition, the regulatory objective of the Hong Kong legislature has been facilitated by providing the SFC in Hong Kong with regulatory oversight and enforcement powers. The JPEX Scandal has highlighted that the law in Hong Kong has a long reach. The provisions are drafted as widely as possible to help ensure that almost any virtual asset provider, operating anywhere in the world, might be caught by the provisions and need to ensure that they obtain a license in Hong Kong, because the failure to do so may lead the SFC to identify that their active marketing elsewhere in the world constitutes “holding out” their status as a virtual asset provider even within Hong Kong itself.

There remain challenges for the law here particularly in the legal characterisation of DAOs, which the Ordinance fails to cover, and in respect of both DeFi and OTC transactions where no virtual asset service provider as defined in the Ordinance has played a role in the transaction. This means that whilst it can be said that the regulatory framework provides a significant step forward for Hong Kong and its ambitions to develop as a global crypto-hub of the future, further regulatory clarity is still needed. This is likely to take some time to develop, as technological development and industrial adoption of blockchain technology itself remains in its infancy. Like all jurisdictions around the world, Hong Kong must take care when introducing regulation in this sector not only to help encourage adoption and to ensure the safety and regulation of the industry, but to do so in a manner which does not result in a regulatory chill of further technological developments.

NL: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. TL: Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author TL was employed by Lau, Horton & Wise LLP, in Association with CMS Hasche Sigle, Hong Kong LLP.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (Amendment) Ordinance (2022). Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (amendment) ordinance. Hong Kong: e-Legislation.

Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance, Cap 615 (2022). Part 5B: virtual asset services. Hong Kong: e-Legislation.

Bauer, D. G., Hong, K., and Lee, A. (2018). Bitcoin: medium of exchange or speculative asset? J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 54, 177–178. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2017.12.004

Choy, K. (2023). Hong Kong amends anti-money laundering law to cover virtual asset service providers. Nixon Peabody. Available at: https://www.nixonpeabody.com/insights/alerts/2023/01/18/hong-kong-amends-anti-money-laundering-law-to-cover-virtual-asset-service-providers (Accessed June 27, 2024).

Clarke, T. (2020). Is bitcoin money? Applications of characteristics and functions of money to bitcoin. 1st ed Grin, 7.

Droulers, A. (2023). Why Hong Kong wants to be a hub for the crypto sector. New York, NY: Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-05/why-hong-kong-wants-to-be-a-hub-for-the-crypto-sector?embedded-checkout=true (Accessed June 27, 2024).

Drylewski, A. C., Kwok, S., Levi, S. D., Zhang, S., and Davis-West, M. (2023). ‘JPEX case is test for Hong Kong’s new regulatory regime for virtual asset exchanges. Skadden Insights. Available at: https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2023/11/jpex-and-hong-kongs-tightened-regulatory-controls (Accessed June 27, 2024).

Government of Hong Kong (2022). Virtual assets and regulatory clarity: legal status of crypto-assets in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau.

Government of Hong Kong (2023). Guideline on anti-money laundering and counter-financing of terrorism. Available at: https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/regulatory-resources/consultations/AML_Guideline_(AI)_20230118.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2024).

Government of Hong KongFinancial Services and the Treasury Bureau (2022). Policy statement on development of virtual assets in Hong Kong. Available at: https://gia.info.gov.hk/general/202210/31/P2022103000454_404805_1_1667173469522.pdf (Accessed June 24, 2024).

Guinto, J., and Yip, M. (2023). JPEX: Hong Kong investigates influencer-backed crypto exchange. BBC News. 22 September.

Hansen, K. B., and Komprozos-Athanasiou, A. (2024). Not so dumb money? Constituting professionals and amateurs in the history of finance capitalism. Thesis Elev. 181, 72–88. doi:10.1177/07255136241240091

Hong Kong Monetary Authority (2024). Consultation conclusions on stablecoin legislative proposals. Available at: https://www.hkma.gov.hk/eng/news-and-media/press-releases/2024/07/20240717-3/(Accessed July 18, 2024).

Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (2024). Statement on JPEX. Available at: https://www.sfc.hk/en/News-and-announcements/Policy-statements-and-announcements/Statement-on-JPEX (Accessed July 18, 2024).

Hutchinson, T., and Duncan, N. S. (2012). Defining and describing what we do: doctrinal legal research. Deakin Law Rev. 17, 83–115. doi:10.21153/dlr2012vol17no1art70

Johnston, M. (2024). HK police offers update on JPEX fraud investigation. Singapore: Regulation Asia. Available at: https://www.regulationasia.com/hk-police-offers-update-on-jpex-fraud-investigation/(Accessed July 18, 2024).

KPMG (2024). Basel IV update: SA and IRB. Available at: https://kpmg.com/cn/en/home/insights/2024/03/basel-iv-update-sa-and-irb.html (Accessed June 27, 2024).

Kyles, D. L. (2022). “Centralised control over decentralised structures: AML and CTF regulation of blockchains and distributed ledgers,” in Financial technology and the law: combating financial crime. Editors D. Goldsbarsht, and L. de Koker 1st edn (Springer).

Leung, H. T. (2024). Cryptocurrency as property under HK law. Available at: https://www.iflr.com/article/2bm4v6fxgluvp6xyjuhog/cryptocurrency-as-property-under-hk-law (Accessed June 26, 2024).