- Institute of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

The development of sustainable processes is the most important basis to realize the shift from the fossil-fuel based industry to bio-based production. Non-model microbes represent a great resource due to their advantageous traits and unique repertoire of bioproducts. However, most of these microbes require modifications to improve their growth and production capacities as well as robustness in terms of genetic stability. For this, genome reduction is a valuable and powerful approach to meet industry requirements and to design highly efficient production strains. Here, we provide an overview of various genome reduction approaches in prokaryotic microorganisms, with a focus on non-model organisms, and highlight the example of a successful genome-reduced model organism chassis. Furthermore, we discuss the advances and challenges of promising non-model microbial chassis.

1 Introduction

Global warming is a worldwide threatening issue that requires immediate action on all levels, from personal behaviour to industrial production. Net zero CO2 emissions need to be achieved by the middle of this century and must be consequently kept from there on (Rogelj et al., 2015; Chen, 2021). To reach this goal, the transition from a fossil-fuel based economy to a bio-based circular economy is required, and industrial biotechnology represents one of its key enabling technologies. Bio-based processes can replace the fossil fuel by deriving chemical products via fewer conversion steps, application of mild process conditions and by avoiding toxic waste formation that is difficult to recycle or degrade (Hatti-Kaul et al., 2007). Hence, new biorefinery principles must be developed and optimised, especially in terms of efficiency. Up to now, the scale-up remains the major challenge, and related key aspects include bioreactor configuration, feedstock pre-treatment and microbial host choice and design (Navarrete et al., 2020). The identification of the proper host and its development towards a microbial chassis represents a crucial step, as it must adapt the organism to the feedstock and process demands, thereby determining the overall efficiency of the process.

Nowadays, only few microbial model organisms are used in the commercial production of amino acids, enzymes or insulin, for example. Traditional microbes, such as Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Corynebacterium glutamicum are well established and consequently more exploited. However, different bioprocesses require different traits, and traditional microbes often lack essential requirements such as: high growth rates, easy handling in diverse bioprocesses, robustness against harsh process conditions, and tolerance towards high substrate and product concentrations (Blombach et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2021). Therefore, the quest of developing new microbial chassis with better traits is essential to fulfil the needs of a sustainable bio-based industry. Collective progress in synthetic biology, metabolic engineering and genome reduction is an important resource to achieve this goal (Ko et al., 2020; Voigt, 2020; Garner, 2021).

Here, we review the current knowledge on microbial chassis development by multiple aspects including genome reduction, genetic manipulation tools, and biotechnological application, focusing on promising non-traditional prokaryotic organisms.

2 Microbial chassis development

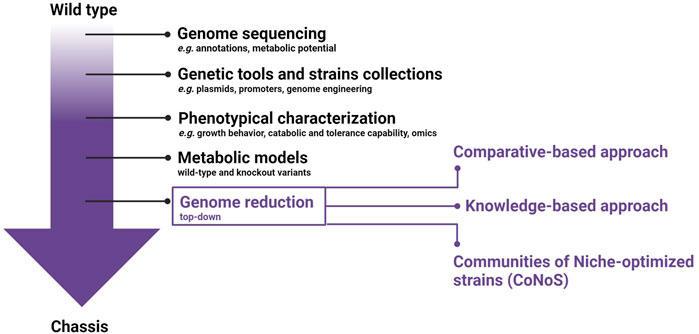

A microbial chassis is defined as an “engineerable and reusable biological platform with a genome encoding several basic functions for stable self-maintenance, growth, and optimal operation but with the tasks and signal processing components growingly edited for strengthening performance under pre-specified environmental conditions” (de Lorenzo et al., 2021). Briefly, to create a microbial chassis, extensive studies are required to provide a detailed information of the general and metabolic features of the selected strain (Figure 1). To start, the complete genome sequence including comprehensive annotation must be available. The in silico analysis of genomic data allows a first evaluation of the metabolic potential. Furthermore, it provides initial knowledge on non-essential genes and putative pathogenic elements that can be targets for the genome reduction strategy. Molecular biological tools, including plasmids and a set of constitutive and inducible promoters of different strengths, have to be developed, alongside genetic engineering tools for precise editing. Ideally, these tools should enable large genomic deletions and multiplexing, enhancing the ease and velocity of genetic manipulations. Omics-based in silico technologies built on quantitative physiology can be exploited to guide strain development to achieve high product titers, rates, and yields. Metabolic models are highly needed and must be constructed based on wild-type (wt) genome and data from knockouts variants. The optimization of the microbial chassis should not only aim at improving its bioproduction performance, but should also require an improvement of its robustness towards industrial settings.

Figure 1. General workflow for chassis development with emphasis on the different approaches available for genome reduction.

3 Genome reduction is a valuable approach for achieving robust chassis

The increasingly efficient new-generation sequencing techniques have completely revolutionized biology (Satam et al., 2023). Biological systems are more and more analysed with a holistic genome-based approach instead of single gene analysis, providing a huge amount of data that highlights the complexity of a cell and gives great insights into the metabolism and physiology. In addition, through the increased number of genomes being sequenced, many predicted proteins with no discernible function are identified (Ijaq et al., 2015). Cell complexity causes unpredictable interactions making modelling of the metabolism and functional predictions more challenging (Choe et al., 2016). For this reason, one of the aims of genome reduction is to reduce the complexity of a chassis and hence improve the predictability and controllability. Genome reduction can proceed in either a bottom-up or top-down approach (Figure 1). The bottom-up approach entails designing and building an artificially synthesized genome. Conversely, the top-down approach starts from an intact genome of the target organism and proceeds with a systematic removal of “unnecessary” genes and genomic regions.

For the sake of the simplicity of this review, bottom-up approaches will be discussed in more detail elsewhere (Chi et al., 2019). Yet, it is worth mentioning the significance of the JCVI-syn3.0 project, which successfully created the first minimal cell (Glass et al., 2017). This engineered cell encodes only for 473 genes in its genome, which is a much lower number than any other free-living organism. While this synthetic cell can survive and replicate, the elimination of many non-essential genes caused 3-fold less slower growth rate than that of the parental Mycoplasma mycoides and some altered morphological traits. To achieve the goal of an industrial chassis a prior thorough knowledge of gene essentiality is required, especially to maintain proper growth and production. Indeed, insufficient knowledge of essential gene sets, especially of non-model organisms, is the main limitation of the bottom-up approach to directly design an active genome. Based on the enormous progress of AI-based tools for genome editing, metabolic modelling in combination with automation and high-throughput genome editing and screening techniques the progress of genome reduction will be enormously accelerated and increasingly efficient (Zampieri et al., 2019; Li S. et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2023). These emerging techniques and approaches will be beneficial for both bottom-up as well as top-down approaches, leading to customized and/or new-to-nature strains for specific applications (Kim et al., 2024). Once there will be this extensive progress, there might be a trade-off between choosing which genome reduction approach is more appropriate to use for a certain application. However, for now, the top-down down approach is less costly and relatively straightforward which is why this approach is more widely used.

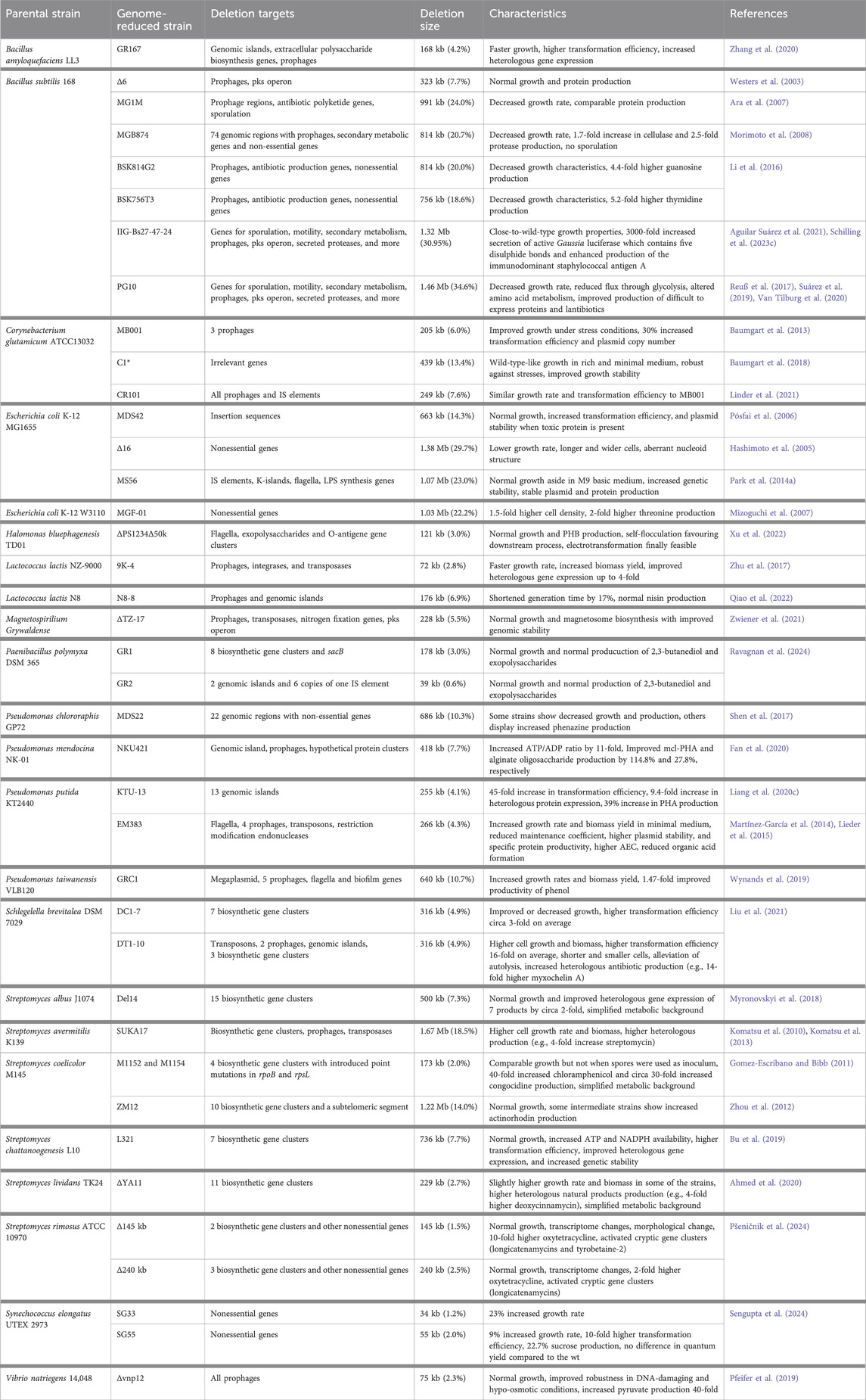

Nowadays, many prokaryotic strains are subjected to genome reduction, as given in Table 1. Compared with eukaryotic genomes, bacterial genomes are smaller and encode a smaller number of genes. Consequently, genome reduction approaches have been less exploited in eukaryotes and were mainly performed to gain knowledge on cellular function and survival strategies (Kurasawa et al., 2020). The few genome reductions as performed for S. cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pombe were both valuable from a functional and industrial application perspective (Sasaki et al., 2013; Shao et al., 2018; Postma et al., 2022). An increase in protein production was achieved for S. pombe (Sasaki et al., 2013). Although negative characteristics were observed for the genome reduced S. cerevisiae, higher levels of ethanol and glycerol were reached (Murakami et al., 2007). A recent approach was used to acquire further knowledge on central carbon metabolism (CCM) by deleting 32 % of CCM-related proteins. No major effects on the growth behaviour were identified. Yet, this study contributes to guide future minimized yeast chassis (Postma et al., 2022).

Concerning prokaryotes, many studies on genome reduction have shown the great benefits of top-down approaches when developing a microbial cell factory: enhancement of genomic stability, higher transformation efficiency, optimization of downstream application and improvement of growth rate and/or bioproduction. The enhancement of genomic stability is reached through the deletion of genetic mobile elements, such as prophages or insertion sequences (IS), and SOS response mechanisms due to causing negative random mutations and/or product inactivation (Csörgo et al., 2012; Park M. K. et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2015; Peng and Liang, 2020; Zwiener et al., 2021). Park et al. developed an IS-free E. coli strain, and enhanced the production of two recombinant proteins, the tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and the bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMBP2) by 25 % and 20 %, respectively (Park M. K. et al., 2014). The deletion of the error-prone DNA polymerases in E. coli also showed increased genomic stability and a 50 % decrease in spontaneous mutation rate (Csörgo et al., 2012). To improve downstream applications, the deletion of undesired products is essential. Many studies have focused on the deletion of antibiotics encoding genes, but also on increasing the precursor supply necessary for a target product (Gomez-Escribano and Bibb, 2011; Myronovskyi et al., 2018; Ahmed et al., 2020). Myronovskyi et al. developed a Streptomyces albus strain in which 15 native antibiotic gene clusters were deleted. The mutant displayed higher production of 5 heterologous expressed biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) of around 2-fold compared to the parent strain (Myronovskyi et al., 2018). Another example is Streptomyces lividans in which the deletion of 10 endogenous antibiotic encoding clusters resulted in a higher growth rate and a 4.5-fold increase of the production of the heterologous expressed deoxycinnamycin (Ahmed et al., 2020). Furthermore, in both studies, the metabolic background was greatly simplified for the analysis of secondary metabolite gene cluster expression. Finally, the deletion of unnecessary proportions of a genome at a large scale might lower the operating costs of the living cells (reduction of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis costs) yielding improved cellular performances in terms of growth rates, cell density, and/or productivity compared with their wild-type counterparts (Westers et al., 2003; Mizoguchi et al., 2007; Lieder et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Bu et al., 2019; Wynands et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2020b; Fan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Qiao et al., 2022; Pšeničnik et al., 2024; Sengupta et al., 2024). A 2.83 % genome-reduced Lactococcus lactis strain showed faster growth, increased biomass yield, and improved protein production of up to 4-fold (Zhu et al., 2017). Also, in another study different genome-reduced strains of Pseudomonas putida were developed reaching a total of 4.3% genomic deletion. They were subsequently tested also in bioreactors and proved to be more efficient than the wild type in growth rate, biomass yield, plasmid stability, and viability (Martínez-García et al., 2014; Lieder et al., 2015).

When aiming to reduce a genome, the major challenge is the choice of the targets for deletions. So far, mainly two strategies are applied. The first approach uses comparative genomics to identify essential genes to avoid the deletion of indispensable functions (Kolisnychenko et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2005b; Liang et al., 2020b). The second approach is more knowledge-based and aims at deleting prophage regions, insertion elements, and secondary metabolites (Li et al., 2016; Baumgart et al., 2018; Myronovskyi et al., 2018; Ahmed et al., 2020; Ravagnan et al., 2024). However, undesired side effects can still be observed (Hashimoto et al., 2005; Murakami et al., 2007; Reuß et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Qiao et al., 2022). Noack and Baumgart systematically categorized the whole genome of C. glutamicum in relevant, non-essential and irrelevant genes. Relevant genes are those which are necessary for survival, while non-essential and irrelevant ones are the usual targets for genome reduction (Noack and Baumgart, 2019). Mainly, non-essential genes are a subset of relevant genes that have no effect on cell viability but can be beneficial for cell growth in certain conditions. Instead, irrelevant genes are highly expressed genes whose products are not required under the defined cultivation conditions and they represent the most promising target genes for deletion. The genome-reduced strain can still replicate on its own while displaying advantageous production traits in the defined environment. To define this set of genes, transcriptomics and proteomics data should be included in the desired environment which should mimic as closely as possible the industrial conditions. This approach should be considered and performed for each target product, since different operating conditions may be required. Another promising concept for genome reduction is the Community of Niche-optimized strains (CoNoS), where two strains of the same species are each carrying one or more auxotrophies and cross-feed each other, saving carbon and energy (Noack and Baumgart, 2019). This strategy was successfully applied for the first time in 2022 using two amino acid auxotrophic C. glutamicum strains (Schito et al., 2022). Synthetic communities can be established between genome-reduced strains growing with mutual dependency and opening up to new future perspectives.

4 Microbial chassis from a historical example to new promises

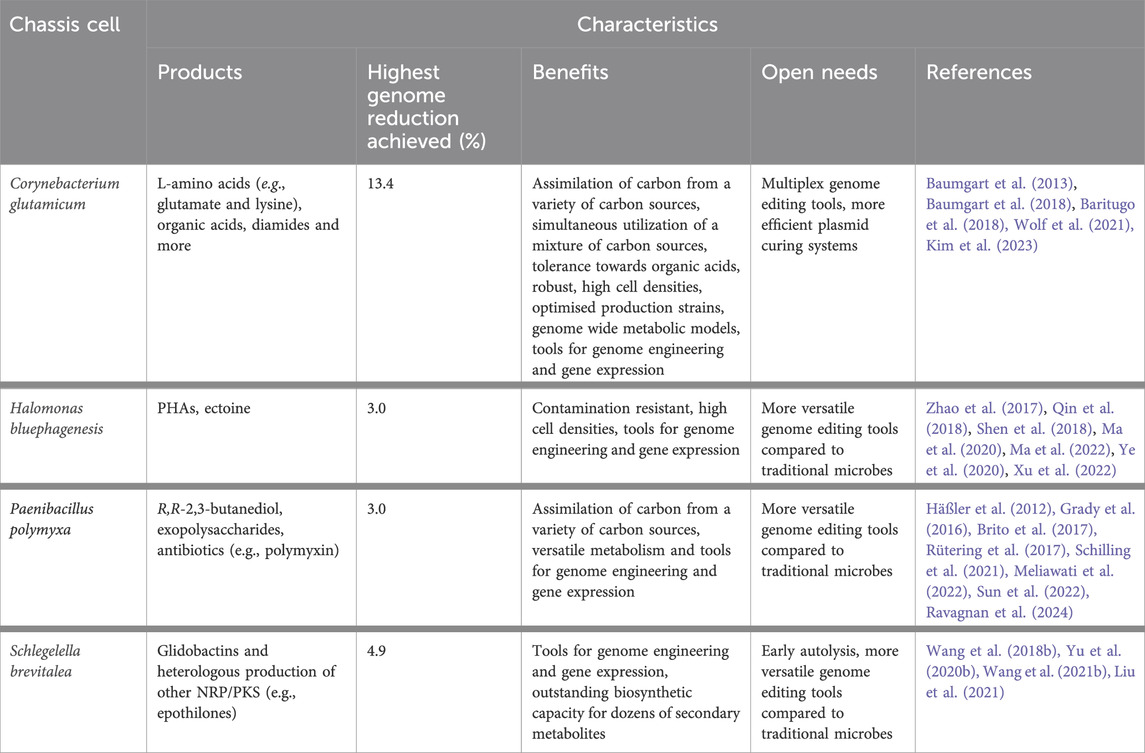

Decades of technological developments have established E. coli, S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis, and C. glutamicum as important workhorses among others. Indeed, these traditional organisms have advantages as chassis cells due to the manifold efficient synthetic biology tools for engineering and well-analyzed genomes and metabolic networks. However, the growing number of more and more versatile and sophisticated bioprocesses and bioproducts bring these established workhorses to their limit from a metabolic point of view. Consequently, new microbes are emerging and gaining more relevance as future chassis. In the section below, we present C. glutamicum as a great example of a model platform chassis, with a special focus on its industrial relevance. Following, we will present an overview of alternative promising microbes with great potential for the production of different value-added products based on their specific characteristics (Table 2).

4.1 Corynebacterium glutamicum

Corynebacterium glutamicum is a facultative anaerobic bacterium that has been used safely for more than 50 years in the food and feed industry. It is commercially used for the production of L-amino acids including the dominating products L-glutamate and L-lysine (Park S. H. et al., 2014; Bampidis et al., 2019). It is also an efficient platform organism for the biotechnological production of diverse and valuable products like organic acids, carotenoids, fuels, diamines, and more (Becker et al., 2018; Wolf et al., 2021).

C. glutamicum represents an excellent workhorse for several reasons. C. glutamicum can assimilate a variety of different carbon sources, like sugars, organic acids, and aromatic compounds simultaneously which renders it superior compared to E. coli, B. subtilis or S. cerevisiae (Baritugo et al., 2018; Inui and Toyoda, 2020). In addition, C. glutamicum shows only a weak carbon catabolite inhibitory effect on mixed carbon sources, which is highly beneficial for industrial applications (Wendisch et al., 2000; Buschke et al., 2013). However, it cannot directly utilize complex polysaccharides, such as xylan, cellulose or starch (Baritugo et al., 2018). For this reason, it has been engineered for consolidated bioprocessing by the heterologous expression of amylolytic and cellulolytic enzymes to produce different biochemicals (Lee et al., 2014; Yim et al., 2017). Another important feature is its robustness and tolerance to organic acids, furfural, and toxic aromatic compounds as obtained from hydrolysis of next-generation feedstocks such as lignocellulosic biomass. Moreover, C. glutamicum cells maintain a strong catalytic function and high-density fermentation under growth-inhibiting conditions (Chen et al., 2017; Conrady et al., 2019; Kitade et al., 2020).

Genomic robust strains, which are free from the adverse effects of prophages and IS elements, are highly demanded in industrial settings. C. glutamicum is a great example of how the deletion of such destabilizing genomic elements can improve bioproduction. Choi et al. deleted the major IS elements and used the resulting mutant for the plasmid-borne production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and γ-aminobutyrate. The authors observed an improved productivity of both products (Choi et al., 2015). The first genome-reduced C. glutamicum (MB001) targeted the three prophage sequences of its genome, resulting in a total genome reduction of 6 %. Under SOS-response conditions, in which one of the bacteriophages is induced, the prophage-free variant showed improved growth, higher transformation efficiency, and 30 % increased production of the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) compared to the wild type (Baumgart et al., 2013). The MB001 strain was further engineered by deleting all copies of two IS elements and was used as a starting point for the singular deletion of 36 predicted nonessential regions. 26 of these regions proved not to affect biological fitness (Unthan et al., 2015). Combinatorial deletions of these irrelevant gene clusters resulted in a library of 28 strains that were characterized by different stress conditions. The final C. glutamicum C1* with a total reduced genome of 13.4 % represents an ideal base for further improvements toward a biotechnologically relevant chassis (Baumgart et al., 2018). Many of these genome-reduced mutants were used for the production of various value-added compounds, as reported (Lara and Gossett, 2019). Recently, Linder et al. have deleted all the IS elements of C. glutamicum starting from the MB001 strain (Linder et al., 2021). Additionally, recent studies have also demonstrated their further industrial potential (Henke and Wendisch, 2019; Haupka et al., 2020; Hemmerich et al., 2020; Walter et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2021; Gauttam et al., 2021; Ferrer et al., 2022; Kiefer et al., 2022; Mindt et al., 2022; Prell et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2023). For example, 3-hydroxycadaverine was produced de novo by the lysine overproducing genome-reduced variant, resulting in the highest titer of this compound reported till now of 8.6 g/L (Prell et al., 2022). Mindt et al. produced indole by exploiting the C1* genome-reduced chassis due to its higher product tolerance and lack of a flavin-dependent monooxygenase which is known to oxidize indole to indoxyl (Mindt et al., 2022; Mindt et al., 2023).

A commonly used approach for editing the genome of C. glutamicum is based on the use of a two-step recombination system with a conditionally lethal marker, such as the levansucrase encoding gene sacB (Niebisch and Bott, 2001). Other genetic tools described are the Cre/loxP system and the RecT-mediated single-stranded recombination (Suzuki et al., 2005a; Huang et al., 2017). These procedures are often laborious and/or lack the simultaneous editing of multiple genes. Recent studies have developed two different CRISPR-Cas systems for genome editing: one utilizing Cfp1 (Cas12a) from Francisella novicida, and the other utilizing Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogens (Jiang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). Both approaches resulted in large nucleotide sequences deletions and integrations and single-nucleotide exchanges were realized. Jiang et al. also achieved double-locus editing (Liu et al., 2017). However, this system still requires optimization concerning editing efficiencies. To improve the homologous repair activity CRISPR systems combined with the recombinase RecT system were successfully established (Cho et al., 2017; Wang B. et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021). The recombineering efficiency reached the highest efficiency reported of 13,250 transformed cells/109 viable cells (Li et al., 2021). The CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technology for gene repression has been widely used with the nuclease deactivated dCas9 and dCfp1 (Cleto et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Göttl et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022a). Other synthetic biology tools for controlling gene expression through static and dynamic regulation have also been investigated in C. glutamicum (Yim et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2020). Many synthetic promoter libraries were also generated (Zhang et al., 2015; 2018; Duan et al., 2021). To regulate the metabolic flux in real-time, dynamic regulatory systems were employed (Tan et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2022; Lai et al., 2022). Finally, C. glutamicum counts different genome-metabolic models developed to guide metabolic engineering targets by improving experimental design (Kjeldsen and Nielsen, 2009; Mei et al., 2016; Feierabend et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Deeper insights into available synthetic tools in C. glutamicum are further reviewed elsewhere (Kim et al., 2023).

C. glutamicum has emerged as a potent host to produce molecules for human health and wellbeing and has greatly expanded its role from a traditional producer of amino acids to a multi-functional microbial production platform. Its valuable native and engineered traits secured its establishment in industry and drive the rapid and continuous technical improvements that help gain deeper insights into C. glutamicum physiology and genetics.

4.2 Halomonas bluephagenesis

Halomonas bluephagenesis is an auto sterile halophilic bacterium, with high potential for next-generation industrial biotechnology (NGIB) (Chen and Jiang, 2018). Due to its fast growth in high salt and alkaline conditions, open and continuous processes were conducted for 2 months without any contamination (Tan et al., 2011). Successful cases of unsterile pilot-scale productions were also performed with significant cost reductions, assessing H. bluephagenesis as a suitable industrial strain for large-scale production under open non-sterile conditions (Ye et al., 2018). To support its growth in such unusual environments, it produces different compounds, such as the compatible solute ectoine and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) which is naturally produced as an energy and carbon storage and stress resistance enhancer, up to 80 % of cell dry mass (Tan et al., 2011; Obruca et al., 2018).

PHAs are a family of biodegradable and biocompatible biopolymers with the potential to replace petroleum-based plastics (Keshavarz and Roy, 2010). They can be used in various fields ranging from packaging to biomedical applications (Valappil et al., 2006; Rehm, 2010; Możejko-Ciesielska and Kiewisz, 2016). Since new PHAs are industrially required to provide different material properties that can suit more applications, H. bluephagenesis has also been genetically engineered to produce PHBV, P3HB4HB, PHA copolymyers P(3HB-co-3HHx), and many others (Yu L. P. et al., 2020; Mitra et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2022). To further increase PHA accumulation, many efforts have been made to improve the competitiveness of microbial production via synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

H. bluephagenesis has been manipulated mainly via a markerless gene replacement procedure mediated by double-strand breaks and via a CRISPR-Cas9 based system (Fu et al., 2014; Qin et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2023). The latter was used to engineer the TCA cycle for PHBV production and for de novo synthesis of the 4-hydroxybutyrate-CoA (4HB) pathway for P3HB4HB production (Chen et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2020). Further optimization approaches for PHA production include the investigation of a set of different promoters, starting from Pporin which is a strong constitutive promoter commonly used in Halomonas sp. Based on mutations in the core sequence of this promoter, a promoter library with a wide range of transcriptional strength was created and its tunability was then demonstrated by regulating the PHA biosynthetic pathway (Shen et al., 2018). A novel type of T7-like inducible promoter systems were identified, one of which was used to express the cell-elongation cassette and PHB biosynthetic pathway reaching a 100-fold increase in cell lengths and a final concentration of 92 % PHB by cell dry weight which is the highest titer reached so far (Zhao et al., 2017). By the use of high-resolution control of gene expressions (HRCGE) system, the 4HB pathway was fine-tuned by titrated IPTG concentrations and varying promoter combinations. Once the fine-tuned pathway was integrated into the genome of the mutant of the two succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenases (ΔgabD2 and ΔgabD3), P3HB4HB synthesis was realised and reached 75 % (wt) (Ye et al., 2020). Other studies designed a synthetic oleic acid induced promoter and two other inducible systems induced by acyl homoserine lactone and IPTG for controllable gene expression (Ma et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2022). A CRISPR interference approach was also established in H. bluephagenesis. This system was used to repress the 2-methylcitrate synthase prpC and the citrate synthase gltA genes which reached the accumulation of PHBV of 82 % and 72 % (wt), respectively, without affecting growth (Tao et al., 2017). Recently, the CRISPR-Cas9 genomic engineering system developed by Qi et al. was further optimized by using dual-sgRNA enabling large genomic deletions up to 50 kb. In sum, 3 % of the whole genome was reduced by deleting flagella, exopolysaccharides (EPSs), and O-antigen gene clusters. For the first time, this mutant was efficiently transformed through electroporation and gained the ability to self-flocculate which facilitates separation procedures. This achievement is the first genome-reduced Halomonas strain (Qin et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2022).

Although H. bluephagenesis synthesize only PHB from unrelated carbon sources, it has emerged as a strong candidate for industrial PHA production with the establishment of a tractable genetic system, the completion of genome sequencing, and the wide application of metabolic engineering. Finally, by producing ectoine, this microbe stands also as a future chassis for the co-production of different valuable biomolecules in open unsterile, and continuous growth conditions (Ma et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2024).

4.3 Paenibacillus polymyxa

Paenibacillus polymyxa is a facultative anaerobe and endospore forming bacterium which is used as a biofertilizer due to its plant growth-promoting abilities: it solubilises phosphate, fixates nitrogen and acts as a biocontrol agent against different pathogens. As such, P. polymyxa produces a wide range of antibiotic compounds which are of great interest in agriculture, medicine and food processing (Padda et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2019; Langendries and Goormachtig, 2021). Furthermore, it has garnered an enormous interest for its ability to use different carbon sources and for the production of R,R-2,3-butanediol (2,3-BDL), and EPS (Grady et al., 2016; Schilling et al., 2020).

2,3-BDL and its derivatives are used in a variety of applications, from next-generation fuels, precursor for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics or food preservatives. Nowadays, there is a strong need of an optimised environmentally friendly alternative (Maina et al., 2022). By mainly producing the relevant (2R,3R) isomer, P. polymyxa DSM 365 is regarded as an efficient producer ensuring a great advantage with a higher purity compared to other known pathogenic 2,3-BDL producing organisms. Physical parameters and fermentation conditions have a profound effect on the final product concentration, as shown in many studies (Häßler et al., 2012; Okonkwo et al., 2017; Ju et al., 2023). With 111 g/L, Häßler et al. have reported the highest concentration obtained by P. polymyxa to date (Häßler et al., 2012). Improvements of the 2,3-BDL production were also achieved through genetic engineering. For the first time, Schilling et al. rationally metabolic engineered P. polymyxa improving the carbon flux towards 2,3-BDL by deletion of one lactate dehydrogenase and overexpressing the butanediol dehydrogenase (Schilling et al., 2020). The same authors were also able to increase the production by using the full potential of a CRISPR mediated transcriptional perturbation tool in which three ldh genes were downregulated at the same time with the upregulation of the bdh gene and showed the redirection of the carbon flux from lactate to 2,3-BDL (Schilling et al., 2021).

Within the last few years, P. polymyxa has gained more interest also as a producer of different interesting exopolysaccharides (Raza et al., 2011; Rütering et al., 2016). They are used in a variety of applications from food to cosmetics to pharmaceuticals and many others (Freitas et al., 2015; Paul et al., 1986; Schilling et al., 2020). P. polymyxa is a natural and avid producer of exopolysaccharides which showed to have great potential new properties compared to already commercialized ones (Rütering et al., 2017, Rütering et al., 2018). Depending on the carbon source and the C/N ratio, it can produce a levan-type polyfructan or heteropolysaccharides (Rütering et al., 2016). After many attempts over the last 50 years, using combinatorial knock-outs of functional genes and by combining analytical methods, it was finally discovered that the heteroexopolysaccharide produced by P. polymyxa consists of three distinct polymers which were named paenan I, paenan II and paenan III (Schilling et al., 2022; Schilling et al., 2023b).

Many of these discoveries were facilitated by the efficient editing system based on CRISPR-Cas9 developed in 2017 (Rütering et al., 2017). This system was successfully applied further for large genomic deletions up to 59 kb using one single sgRNA and multiplexing modifications (Rütering et al., 2017; Meliawati et al., 2022; Ravagnan et al., 2024). Indeed, this tool enabled the construction of two robust genome-reduced variants lacking the production of endogenous biosynthetic gene clusters or nonessential genomic regions including the insertion sequence ISPap1. The growth characteristics and the desired product formation of the two variants were maintained at wt-level, an extremely important achievement and starting point for future targeted genetic modifications (Ravagnan et al., 2024). To add to the list of molecular biology tools available in this species, a multiplex base editing system by fusing the dCas9 with a cytidine deaminase to mediate C to T substitutions and, as previously mentioned, a CRISPR-Cas12a tool for mediated activation (CRISPRa) and interference (CRISPRi) were developed (Kim et al., 2021; Schilling et al., 2021). The latter tool enabled a deeper understanding of P. polymyxa metabolism both for 2,3-BDL and EPS production and could help guide other future metabolic engineering strategies (Schilling et al., 2021). Aside from CRISPR systems, other genetic engineering tools have been described, even if less efficient (Choi et al., 2008; Kim and Timmusk, 2013). Finally, heterogeneous promoters and inducible promoters have already been tested in P. polymyxa (Brito et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). Heinze et al. evaluated 11 different promoters from Bacillus species for the expression of cellulases in P. polymyxa (Heinze et al., 2018). Through high-throughput screening, a novel strong and constitutive promoter PLH-77 was identified (Li et al., 2019). The same authors investigated 22 native promoters based on a transcriptomic dataset in which they identified another very strong promoter, especially for the optimization of indol acetic acid (IAA) production (Sun et al., 2022).

As a non-pathogen, P. polymyxa has great potential as a cell factory especially due to its versatile metabolism and the available tools for both genetic and metabolic engineering. The recent tool developed by Meliawati et al. substantially advanced the application of the Cas9-based approach for P. polymyxa (Meliawati et al., 2022). Additionally, the discovery made by Schilling et al. increased the knowledge of this versatile producer paving the way for new approaches toward tailor-made exopolysaccharides with desirable material properties for medical and industrial applications that could outcompete existing oil-based polymers (Schilling et al., 2022; Schilling et al., 2023a; Schilling et al., 2023b).

4.4 Schlegelella brevitalea

The reputation of Schlegelella brevitalea is mostly due to its native production of the novel type of antifungal and antitumor glidobactins, and its efficient heterologous production of several kinds of secondary metabolites, especially the antitumor epothilones (Bian et al., 2014; Bian et al., 2017; Wang X. et al., 2018). Currently, the original producer Sorangium cellulosum is used in the industrial production of epothilones (Gerth et al., 1996). However, this strain shows many disadvantages, such as slow growth and difficulties in genetic modifications (Julien and Shah, 2002; Julien and Fehd, 2003). Therefore, much work has been done to improve epothilones production by S. brevitalea. The epothilone cluster of S. cellulosom was integrated into the genome of S. brevitalea DSM 7029 resulting in the 75-fold increased epothilone yield of 307 μg/L through the optimization of the medium and introducing propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PCC) genes and rare tRNA genes (Bian et al., 2017). Reintegration of another epothilone cluster from a different strain of S. cellulosum and again engineering of the precursor pathway enabled an improved titer of 82 mg/L in 6-day fermentation, a comparable result to the industrial producer S. cellulosum (Yu Y. et al., 2020). Further studies focused on other approaches to improve its production, starting from transporter engineering, overexpression of ferredoxin genes, functional hybrid polyketide synthases (PKS) generation, swapping domains, and both random and site-directed mutagenesis (Liu et al., 2018; Liang J. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023).

A series of genome-reduced S. brevitalea chassis strains were developed and tested for its heterologous BGC expression capacity (Liu et al., 2021). Two parallel deletion routes were taken: the first one deleted 8 BGCs (DC mutants), the second one sequentially removed few BGCs, several transposases, GIs, prophages, and vicinal nonessential genes (DT mutants). The DT mutants showed decreased autolysis with related improved growth characteristics, 16-fold higher transformation efficiencies, and improved yields of heterologous secondary metabolites up to 13-fold. These results demonstrate the feasibility and improved robustness of these genome-reduced mutants for secondary metabolite expression compared to both the wild type and common platform chassis E. coli and P. putida.

With an efficient genome editing system based on the novel bacteriophage recombinases Redαβ7029, which was recently further improved for multiplexing (Wang X. et al., 2018; Wang X. et al., 2021), several native promoters were tested for heterologous expression (Ouyang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021) and successful production of different heterologous secondary metabolites including epothilones, vioprolides, rhizomides, holrhizin, and more (Yan et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2021), S. brevitalea stands out as promising future chassis.

5 Conclusions and future perspectives

Throughout the years industrial biotechnology has made remarkable progress. Traditional microbes are continuously genetically improved and new microbes are identified and brought towards development as future chassis. Unconventional microbes possess unique characteristics and consequently are required for more tailored bioprocesses to cover the whole industrial product portfolio and the whole substrate field. Still, there is a need to expand the synthetic biology, systems biology and high-throughput techniques to a wider range of bacteria, especially these non-model organisms. Gathering more and more data enables the creation of new available tools for the specific microbe, and data-driven gene annotations advance these less studied organisms to “model-organism” status. Accurate gene annotations would also favour the construction of more reliable, robust, genome-reduced strains. Once many well-established genome-reduced strains will be created, they should be rendered available to the community to use them as starting strains to further engineer and exploit in industry. This might be done by providing them in publicly available strain collections such as ATTC, DSMZ or Addgene, or providing them in an academic background similar to the Keio collection of E. coli of which several millions of samples have been distributed by the National Institute of Genetics of Japan. This will massively help to speed up the development of efficient production strains in the future.

In this review, we have delved into the benefits provided by genome reduction strategies and their future directions, also by describing how genome reduction has been applied in C. glutamicum achieving an efficient chassis. As we have also reported, genome reduction has started to be applied in non-model organisms demonstrating its relevance and feasibility as a tool for host optimisation. Indeed, we envision new genome-reduced strains with improved characteristics soon.

Author contributions

GR: Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Visualization, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. JS: Funding acquisition, Writing–review and editing, Visualization, Validation, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is part of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) funded project Polymore with the no.031B0855A.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguilar Suárez, R., Antelo-Varela, M., Maaß, S., Neef, J., Becher, D., and Maarten Van Dijl, J. (2021). Redirected stress responses in a genome-minimized “midiBacillus” strain with enhanced capacity for protein secretion. mSystems 6, e0065521–21. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00655-21

Ahmed, Y., Rebets, Y., Estévez, M. R., Zapp, J., Myronovskyi, M., and Luzhetskyy, A. (2020). Engineering of Streptomyces lividans for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 5. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-1277-8

Ara, K., Ozaki, K., Nakamura, K., Yamane, K., Sekiguchi, J., and Ogasawara, N. (2007). Bacillus minimum genome factory: effective utilization of microbial genome information. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46, 169–178. doi:10.1042/ba20060111

Bampidis, V., Azimonti, G., de Lourdes Bastos, M., Christensen, H., Dusemund, B., Kouba, M., et al. (2019). Safety and efficacy of l-tryptophan produced by fermentation with Corynebacterium glutamicum KCCM 80176 for all animal species. EFSA J. 17, e05729. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5729

Banerjee, D., Eng, T., Sasaki, Y., Srinivasan, A., Herbert, R. A., Trinh, J., et al. (2021). Genomics characterization of an engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum in bioreactor cultivation under ionic liquid stress 2. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 766674. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.766674

Baritugo, K. A. G., Kim, H. T., David, Y. C., Choi, J. H., Choi, J. il, Kim, T. W., et al. (2018). Recent advances in metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum as a potential platform microorganism for biorefinery. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 12, 899–925. doi:10.1002/bbb.1895

Baumgart, M., Unthan, S., Kloß, R., Radek, A., Polen, T., Tenhaef, N., et al. (2018). Corynebacterium glutamicum chassis C1∗: building and testing a novel platform host for synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 132–144. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00261

Baumgart, M., Unthan, S., Rückert, C., Sivalingam, J., Grünberger, A., Kalinowski, J., et al. (2013). Construction of a prophage-free variant of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 for use as a platform strain for basic research and industrial biotechnology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6006–6015. doi:10.1128/AEM.01634-13

Becker, J., Rohles, C. M., and Wittmann, C. (2018). Metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum for bio-based production of chemicals, fuels, materials, and healthcare products. Metab. Eng. 50, 122–141. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.07.008

Bian, X., Huang, F., Wang, H., Klefisch, T., Müller, R., and Zhang, Y. (2014). Heterologous production of glidobactins/luminmycins in Escherichia coli Nissle containing the glidobactin biosynthetic gene cluster from Burkholderia DSM7029. Chembiochem 15, 2221–2224. doi:10.1002/cbic.201402199

Bian, X., Tang, B., Yu, Y., Tu, Q., Gross, F., Wang, H., et al. (2017). Heterologous production and yield improvement of epothilones in burkholderiales strain DSM 7029. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 1805–1812. doi:10.1021/acschembio.7b00097

Blombach, B., Grunberger, A., Centler, F., Wierckx, N., and Schmid, J. (2021). Exploiting unconventional prokaryotic hosts for industrial biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 40, 385–397. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.08.003

Brito, L. F., Irla, M., Walter, T., and Wendisch, V. F. (2017). Magnesium aminoclay-based transformation of Paenibacillus riograndensis and Paenibacillus polymyxa and development of tools for gene expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 735–747. doi:10.1007/s00253-016-7999-1

Bu, Q. T., Yu, P., Wang, J., Li, Z. Y., Chen, X. A., Mao, X. M., et al. (2019). Rational construction of genome-reduced and high-efficient industrial Streptomyces chassis based on multiple comparative genomic approaches. Microb. Cell Fact. 18, 16. doi:10.1186/s12934-019-1055-7

Buschke, N., Schäfer, R., Becker, J., and Wittmann, C. (2013). Metabolic engineering of industrial platform microorganisms for biorefinery applications - optimization of substrate spectrum and process robustness by rational and evolutive strategies. Bioresour. Technol. 135, 544–554. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.047

Chen, C., Pan, J., Yang, X., Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Si, M., et al. (2017). Global transcriptomic analysis of the response of Corynebacterium glutamicum to ferulic acid. Arch. Microbiol. 199, 325–334. doi:10.1007/s00203-016-1306-5

Chen, G. Q., and Jiang, X. R. (2018). Next generation industrial biotechnology based on extremophilic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 50, 94–100. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2017.11.016

Chen, J. M. (2021). Carbon neutrality: toward a sustainable future. Innovation 2, 100127. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100127

Chen, Y., Chen, X. Y., Du, H. T., Zhang, X., Ma, Y. M., Chen, J. C., et al. (2019). Chromosome engineering of the TCA cycle in Halomonas bluephagenesis for production of copolymers of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 3-hydroxyvalerate (PHBV). Metab. Eng. 54, 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.006

Cheng, Y., Bi, X., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., Li, J., Du, G., et al. (2023). Machine learning for metabolic pathway optimization: a review. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 2381–2393. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.03.045

Chi, H., Wang, X., Shao, Y., Qin, Y., Deng, Z., Wang, L., et al. (2019). Engineering and modification of microbial chassis for systems and synthetic biology. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 4, 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.synbio.2018.12.001

Cho, J. S., Choi, K. R., Prabowo, C. P. S., Shin, J. H., Yang, D., Jang, J., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-coupled recombineering for metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab. Eng. 42, 157–167. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.06.010

Choe, D., Cho, S., Kim, S. C., and Cho, B. K. (2016). Minimal genome: worthwhile or worthless efforts toward being smaller? Biotechnol. J. 11, 199–211. doi:10.1002/biot.201400838

Choi, J. W., Yim, S. S., Kim, M. J., and Jeong, K. J. (2015). Enhanced production of recombinant proteins with Corynebacterium glutamicum by deletion of insertion sequences (IS elements). Microb. Cell Fact. 14, 207. doi:10.1186/s12934-015-0401-7

Choi, S. K., Park, S. Y., Kim, R., Lee, C. H., Kim, J. F., and Park, S. H. (2008). Identification and functional analysis of the fusaricidin biosynthetic gene of Paenibacillus polymyxa E681. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 365, 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.147

Cleto, S., Jensen, J. V. K., Wendisch, V. F., and Lu, T. K. (2016). Corynebacterium glutamicum metabolic engineering with CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 375–385. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.5b00216

Conrady, M., Lemoine, A., Limberg, M. H., Oldiges, M., Neubauer, P., and Junne, S. (2019). Carboxylic acid consumption and production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol. Prog. 35, e2804. doi:10.1002/btpr.2804

Csörgo, B., Fehér, T., Tímár, E., Blattner, F. R., and Pósfai, G. (2012). Low-mutation-rate, reduced-genome Escherichia coli: an improved host for faithful maintenance of engineered genetic constructs. Microb. Cell Fact. 11, 11. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-11-11

de Lorenzo, V., Krasnogor, N., and Schmidt, M. (2021). For the sake of the bioeconomy: define what a synthetic biology chassis is. N. Biotechnol. 60, 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2020.08.004

Duan, Y., Zhai, W., Liu, W., Zhang, X., Shi, J. S., Zhang, X., et al. (2021). Fine-Tuning multi-gene clusters via well-characterized gene expression regulatory elements: case study of the arginine synthesis pathway in C. glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 10, 38–48. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00405

Fan, X., Zhang, Y., Zhao, F., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, S., et al. (2020). Genome reduction enhances production of polyhydroxyalkanoate and alginate oligosaccharide in Pseudomonas mendocina. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 163, 2023–2031. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.067

Feierabend, M., Renz, A., Zelle, E., Nöh, K., Wiechert, W., and Dräger, A. (2021). High-quality genome-scale reconstruction of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032. Front. Microbiol. 12, 750206. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.750206

Ferrer, L., Elsaraf, M., Mindt, M., and Wendisch, V. F. (2022). L-serine biosensor-controlled fermentative production of L-tryptophan derivatives by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biol. (Basel) 11, 744. doi:10.3390/biology11050744

Freitas, F., Alves, V. D., and Reis, M. A. M. (2015). Bacterial polysaccharides: Production and applications in cosmetic industry, in Polysaccharides: Bioactivity and Biotechnology. Springer International Publishing, 2017–2043.

Fu, X. Z., Tan, D., Aibaidula, G., Wu, Q., Chen, J. C., and Chen, G. Q. (2014). Development of Halomonas TD01 as a host for open production of chemicals. Metab. Eng. 23, 78–91. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.006

Garner, K. L. (2021). Principles of synthetic biology. Essays Biochem. 65, 791–811. doi:10.1042/EBC20200059

Gauttam, R., Desiderato, C. K., Radoš, D., Link, H., Seibold, G. M., and Eikmanns, B. J. (2021). Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 748510. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.748510

Gerth, K., Bedorf, N., Höfle, G., Irschik, H., and Reichenbach, H. (1996). Epothilons A and B: antifungal and cytotoxic compoundsfrom Sorangium cellulosum (myxobacteria) production, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 49, 560–563. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.49.560

Glass, J. I., Merryman, C., Wise, K. S., Hutchison, C. A., and Smith, H. O. (2017). Minimal cells-real and imagined. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a023861. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a023861

Gomez-Escribano, J. P., and Bibb, M. J. (2011). Engineering Streptomyces coelicolor for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 207–215. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00219.x

Göttl, V. L., Schmitt, I., Braun, K., Peters-wendisch, P., Wendisch, V. F., and Henke, N. A. (2021). Crispri-library-guided target identification for engineering carotenoid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microorganisms 9, 670. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9040670

Grady, E. N., MacDonald, J., Liu, L., Richman, A., and Yuan, Z. C. (2016). Current knowledge and perspectives of Paenibacillus: a review. Microb. Cell Fact. 15, 203. doi:10.1186/s12934-016-0603-7

Hashimoto, M., Ichimura, T., Mizoguchi, H., Tanaka, K., Fujimitsu, K., Keyamura, K., et al. (2005). Cell size and nucleoid organization of engineered Escherichia coli cells with a reduced genome. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 137–149. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04386.x

Hatti-Kaul, R., Törnvall, U., Gustafsson, L., and Börjesson, P. (2007). Industrial biotechnology for the production of bio-based chemicals - a cradle-to-grave perspective. Trends Biotechnol. 25, 119–124. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.01.001

Haupka, C., Delépine, B., Irla, M., Heux, S., and Wendisch, V. F. (2020). Flux enforcement for fermentative production of 5-aminovalerate and glutarate by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Catalysts 10, 1065–1115. doi:10.3390/catal10091065

Häßler, T., Schieder, D., Pfaller, R., Faulstich, M., and Sieber, V. (2012). Enhanced fed-batch fermentation of 2,3-butanediol by Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Bioresour. Technol. 124, 237–244. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.047

Heinze, S., Zimmermann, K., Ludwig, C., Heinzlmeir, S., Schwarz, W. H., Zverlov, V. V., et al. (2018). Evaluation of promoter sequences for the secretory production of a Clostridium thermocellum cellulase in Paenibacillus polymyxa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 10147–10159. doi:10.1007/s00253-018-9369-7

Hemmerich, J., Labib, M., Steffens, C., Reich, S. J., Weiske, M., Baumgart, M., et al. (2020). Screening of a genome-reduced Corynebacterium glutamicum strain library for improved heterologous cutinase secretion. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 2020–2031. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13660

Henke, N. A., and Wendisch, V. F. (2019). Improved astaxanthin production with Corynebacterium glutamicum by application of a membrane fusion protein. Mar. Drugs 17, 621. doi:10.3390/md17110621

Hu, Q., Sun, S., Zhang, Z., Liu, W., Yi, X., He, H., et al. (2024). Ectoine hyperproduction by engineered Halomonas bluephagenesis. Metab. Eng. 82, 238–249. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2024.02.010

Huang, Y., Li, L., Xie, S., Zhao, N., Han, S., Lin, Y., et al. (2017). Recombineering using RecET in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC14067 via a self-excisable cassette. Sci. Rep. 7, 7916. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08352-9

Ijaq, J., Chandrasekharan, M., Poddar, R., Bethi, N., and Sundararajan, V. S. (2015). Annotation and curation of uncharacterized proteins-challenges. Front. Genet. 6, 119. doi:10.3389/fgene.2015.00119

Inui, M., and Toyoda, K. (2020). “Corynebacterium glutamicum,” in Biology and biotechnology. Editors M. Inui, and K. Toyoda Available at: http://www.springer.com/series/7171.

Jackson, S. S., Sumner, L. E., and Casagrande, R. J. (2021). Alternative hosts as the missing link for equitable therapeutic protein production. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 403–404. doi:10.1038/s41587-021-00892-w

Jeong, H., Choi, S. K., Ryu, C. M., and Park, S. H. (2019). Chronicle of a soil bacterium: Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 as a tiny guardian of plant and human health. Front. Microbiol. 10, 467. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00467

Jiang, Y., Qian, F., Yang, J., Liu, Y., Dong, F., Xu, C., et al. (2017). CRISPR-Cpf1 assisted genome editing of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nat. Commun. 8, 15179. doi:10.1038/ncomms15179

Ju, J. H., Jo, M. H., Heo, S. Y., Kim, M. S., Kim, C. H., Paul, N. C., et al. (2023). Production of highly pure R,R-2,3-butanediol for biological plant growth promoting agent using carbon feeding control of Paenibacillus polymyxa MDBDO. Microb. Cell Fact. 22, 121. doi:10.1186/s12934-023-02133-y

Julien, B., and Fehd, R. (2003). Development of a mariner-based transposon for use in Sorangium cellulosum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 6299–6301. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.10.6299-6301.2003

Julien, B., and Shah, S. (2002). Heterologous expression of epothilone biosynthetic genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 2772–2778. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.9.2772-2778.2002

Keshavarz, T., and Roy, I. (2010). Polyhydroxyalkanoates: bioplastics with a green agenda. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 321–326. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2010.02.006

Kiefer, D., Tadele, L. R., Lilge, L., Henkel, M., and Hausmann, R. (2022). High-level recombinant protein production with Corynebacterium glutamicum using acetate as carbon source. Microb. Biotechnol. 15, 2744–2757. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.14138

Kim, G. Y., Kim, J., Park, G., Kim, H. J., Yang, J., and Seo, S. W. (2023). Synthetic biology tools for engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 1955–1965. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.03.004

Kim, K., Choe, D., Cho, S., Palsson, B., and Cho, B. K. (2024). Reduction-to-synthesis: the dominant approach to genome-scale synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2024.02.008

Kim, M. S., Kim, H. R., Jeong, D. E., and Choi, S. K. (2021). Cytosine base editor-mediated multiplex genome editing to accelerate discovery of novel antibiotics in Bacillus subtilis and Paenibacillus polymyxa. Front. Microbiol. 12, 691839. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.691839

Kim, S. B., and Timmusk, S. (2013). A simplified method for gene knockout and direct screening of recombinant clones for application in Paenibacillus polymyxa. PLoS One 8, e68092. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068092

Kitade, Y., Hiraga, K., and Inui, M. (2020). Aromatic compound catabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum, 323–337. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39267-3_11

Kjeldsen, K. R., and Nielsen, J. (2009). In silico genome-scale reconstruction and validation of the Corynebacterium glutamicum metabolic network. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 102, 583–597. doi:10.1002/bit.22067

Ko, Y. S., Kim, J. W., Lee, J. A., Han, T., Kim, G. B., Park, J. E., et al. (2020). Tools and strategies of systems metabolic engineering for the development of microbial cell factories for chemical production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4615–4636. doi:10.1039/d0cs00155d

Kolisnychenko, V., Plunkett, G., Herring, C. D., Fehér, T., Pósfai, J., Blattner, F. R., et al. (2002). Engineering a reduced Escherichia coli genome. Genome Res. 12, 640–647. doi:10.1101/gr.217202

Komatsu, M., Komatsu, K., Koiwai, H., Yamada, Y., Kozone, I., Izumikawa, M., et al. (2013). Engineered Streptomyces avermitilis host for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene cluster for secondary metabolites. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 384–396. doi:10.1021/sb3001003

Komatsu, M., Uchiyama, T., Ōmura, S., Cane, D. E., and Ikeda, H. (2010). Genome-minimized Streptomyces host for the heterologous expression of secondary metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 2646–2651. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914833107

Kurasawa, H., Ohno, T., Arai, R., and Aizawa, Y. (2020). A guideline and challenges toward the minimization of bacterial and eukaryotic genomes. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 24, 127–134. doi:10.1016/j.coisb.2020.10.012

Lai, W., Shi, F., Tan, S., Liu, H., Li, Y., and Xiang, Y. (2022). Dynamic control of 4-hydroxyisoleucine biosynthesis by multi-biosensor in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 5105–5121. doi:10.1007/s00253-022-12034-6

Langendries, S., and Goormachtig, S. (2021). Paenibacillus polymyxa, a Jack of all trades. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 5659–5669. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15450

Lara, A. R.,, and Gossett, G. (2019). Minimal cells: design, construction, biotechnological applications (Berlin, Germany: Springer international publishing).

Lee, J., Sim, S. J., Bott, M., Um, Y., Oh, M. K., and Woo, H. M. (2014). Succinate production from CO2-grown microalgal biomass as carbon source using engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum through consolidated bioprocessing. Sci. Rep. 4, 5819. doi:10.1038/srep05819

Li, C., Swofford, C. A., Rückert, C., and Sinskey, A. J. (2021). Optimizing recombineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 118, 2255–2264. doi:10.1002/bit.27737

Li, H., Ding, Y., Zhao, J., Ge, R., Qiu, B., Yang, X., et al. (2019). Identification of a native promoter PLH-77 for gene expression in Paenibacillus polymyxa. J. Biotechnol. 295, 19–27. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.02.002

Li, M., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Huang, J., Chen, N., et al. (2020). Efficient multiplex gene repression by CRISPR-dCpf1 in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 357. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00357

Li, N., Shan, X., Zhou, J., and Yu, S. (2022a). Identification of key genes through the constructed CRISPR-dcas9 to facilitate the efficient production of O-acetylhomoserine in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 978686. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.978686

Li, S., An, J., Li, Y., Zhu, X., Zhao, D., Wang, L., et al. (2022b). Automated high-throughput genome editing platform with an AI learning in situ prediction model. Nat. Commun. 13, 7386. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35056-0

Li, Y., Zhu, X., Zhang, X., Fu, J., Wang, Z., Chen, T., et al. (2016). Characterization of genome-reduced Bacillus subtilis strains and their application for the production of guanosine and thymidine. Microb. Cell Fact. 15, 94. doi:10.1186/s12934-016-0494-7

Liang, J., Wang, H., Bian, X., Zhang, Y., Zhao, G., and Ding, X. (2020a). Heterologous redox partners supporting the efficient catalysis of epothilone B biosynthesis by EpoK in Schlegelella brevitalea. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 180. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01439-5

Liang, P., Zhang, Y., Xu, B., Zhao, Y., Liu, X., Gao, W., et al. (2020b). Deletion of genomic islands in the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 genome can create an optimal chassis for synthetic biology applications. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 70. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01329-w

Liang, P., Zhang, Y., Xu, B., Zhao, Y., Liu, X., Gao, W., et al. (2020c). Deletion of genomic islands in the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 genome can create an optimal chassis for synthetic biology applications. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 70. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01329-w

Lieder, S., Nikel, P. I., de Lorenzo, V., and Takors, R. (2015). Genome reduction boosts heterologous gene expression in Pseudomonas putida. Microb. Cell Fact. 14, 23. doi:10.1186/s12934-015-0207-7

Linder, M., Haak, M., Botes, A., Kalinowski, J., and Rückert, C. (2021). Construction of an IS-free Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13 032 chassis strain and random mutagenesis using the endogenous ISCg1 transposase. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 751334. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.751334

Liu, C., Yu, F., Liu, Q., Bian, X., Hu, S., Yang, H., et al. (2018). Yield improvement of epothilones in Burkholderia strain DSM7029 via transporter engineering. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 365. doi:10.1093/femsle/fny045

Liu, C., Yue, Y., Xue, Y., Zhou, C., and Ma, Y. (2023). CRISPR-Cas9 assisted non-homologous end joining genome editing system of Halomonas bluephagenesis for large DNA fragment deletion. Microb. Cell Fact. 22, 211. doi:10.1186/s12934-023-02214-y

Liu, J., Wang, Y., Lu, Y., Zheng, P., Sun, J., and Ma, Y. (2017). Development of a CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing toolbox for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Cell Fact. 16, 205. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0815-5

Liu, J., Zhou, H., Yang, Z., Wang, X., Chen, H., Zhong, L., et al. (2021). Rational construction of genome-reduced Burkholderiales chassis facilitates efficient heterologous production of natural products from proteobacteria. Nat. Commun. 12, 4347. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24645-0

Liu, W., Tang, D., Wang, H., Lian, J., Huang, L., and Xu, Z. (2019). Combined genome editing and transcriptional repression for metabolic pathway engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum using a catalytically active Cas12a. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 8911–8922. doi:10.1007/s00253-019-10118-4

Ma, H., Zhao, Y., Huang, W., Zhang, L., Wu, F., Ye, J., et al. (2020). Rational flux-tuning of Halomonas bluephagenesis for co-production of bioplastic PHB and ectoine. Nat. Commun. 11, 3313. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17223-3

Ma, Y., Zheng, X., Lin, Y., Zhang, L., Yuan, Y., Wang, H., et al. (2022). Engineering an oleic acid-induced system for Halomonas, E. coli and Pseudomonas. Metab. Eng. 72, 325–336. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2022.04.003

Maina, S., Prabhu, A. A., Vivek, N., Vlysidis, A., Koutinas, A., and Kumar, V. (2022). Prospects on bio-based 2,3-butanediol and acetoin production: recent progress and advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 54, 107783. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107783

Martínez-García, E., Nikel, P. I., Aparicio, T., and de Lorenzo, V. (2014). Pseudomonas 2.0: genetic upgrading of P. putida KT2440 as an enhanced host for heterologous gene expression. Microb. Cell Fact. 13, 159. doi:10.1186/s12934-014-0159-3

Mei, J., Xu, N., Mei, J., Liu, L., and Wu, J. (2016). Reconstruction and analysis of a genome-scale metabolic network of Corynebacterium glutamicum S9114. Gene 575, 615–622. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.09.038

Meliawati, M., Teckentrup, C., and Schmid, J. (2022). CRISPR-Cas9-mediated Large cluster deletion and multiplex genome editing in Paenibacillus polymyxa. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 77–84. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.1c00565

Mindt, M., Beyraghdar Kashkooli, A., Suarez-Diez, M., Ferrer, L., Jilg, T., Bosch, D., et al. (2022). Production of indole by Corynebacterium glutamicum microbial cell factories for flavor and fragrance applications. Microb. Cell Fact. 21, 45. doi:10.1186/s12934-022-01771-y

Mindt, M., Ferrer, L., Bosch, D., Cankar, K., and Wendisch, V. F. (2023). De novo tryptophanase-based indole production by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 1621–1634. doi:10.1007/s00253-023-12397-4

Mitra, R., Xu, T., Xiang, H., and Han, J. (2020). Current developments on polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis by using halophiles as a promising cell factory. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 86. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-01342-z

Mizoguchi, H., Mori, H., and Fujio, T. (2007). Escherichia coli minimum genome factory. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46, 157–167. doi:10.1042/ba20060107

Morimoto, T., Kadoya, R., Endo, K., Tohata, M., Sawada, K., Liu, S., et al. (2008). Enhanced recombinant protein productivity by genome reduction in Bacillus subtilis. DNA Res. 15, 73–81. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn002

Możejko-Ciesielska, J., and Kiewisz, R. (2016). Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates: still fabulous? Microbiol. Res. 192, 271–282. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2016.07.010

Murakami, K., Tao, E., Ito, Y., Sugiyama, M., Kaneko, Y., Harashima, S., et al. (2007). Large scale deletions in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome create strains with altered regulation of carbon metabolism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75, 589–597. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-0859-2

Myronovskyi, M., Rosenkränzer, B., Nadmid, S., Pujic, P., Normand, P., and Luzhetskyy, A. (2018). Generation of a cluster-free Streptomyces albus chassis strains for improved heterologous expression of secondary metabolite clusters. Metab. Eng. 49, 316–324. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.09.004

Navarrete, C., Jacobsen, I. H., Martínez, J. L., and Procentese, A. (2020). Cell factories for industrial production processes: current issues and emerging solutions. Processes 8, 768. doi:10.3390/pr8070768

Niebisch, A., and Bott, M. (2001). Molecular analysis of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 branch of the Corynebacterium glutamicum respiratory chain containing an unusual diheme cytochrome c1. Arch. Microbiol. 175, 282–294. doi:10.1007/s002030100262

Niu, J., Mao, Z., Mao, Y., Wu, K., Shi, Z., Yuan, Q., et al. (2022). Construction and analysis of an enzyme-constrained metabolic model of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biomolecules 12, 1499. doi:10.3390/biom12101499

Noack, S., and Baumgart, M. (2019). Communities of niche-optimized strains: small-genome organism consortia in bioproduction. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 126–139. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.07.011

Obruca, S., Sedlacek, P., Koller, M., Kucera, D., and Pernicova, I. (2018). Involvement of polyhydroxyalkanoates in stress resistance of microbial cells: biotechnological consequences and applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 856–870. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.12.006

Okonkwo, C. C., Ujor, V. C., Mishra, P. K., and Ezeji, T. C. (2017). Process development for enhanced 2,3-butanediol production by Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Fermentation 3, 18. doi:10.3390/fermentation3020018

Ouyang, Q., Wang, X., Zhang, N., Zhong, L., Liu, J., Ding, X., et al. (2020). Promoter screening facilitates heterologous production of complex secondary metabolites in burkholderiales strains. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 457–460. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00459

Padda, K. P., Puri, A., and Chanway, C. P. (2017). “Paenibacillus polymyxa: a prominent biofertilizer and biocontrol agent for sustainable agriculture,” in Agriculturally important microbes for sustainable agriculture (Springer Singapore), 165–191. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5343-6_6

Paul, F., Morin, A., and Monsan, P. (1986). Microbial polysaccharides with actual potential industrial applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 4, 245–259. doi:10.1016/0734-9750(86)90311-3

Park, M. K., Lee, S. H., Yang, K. S., Jung, S. C., Lee, J. H., and Kim, S. C. (2014a). Enhancing recombinant protein production with an Escherichia coli host strain lacking insertion sequences. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 6701–6713. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-5739-y

Park, S. H., Kim, H. U., Kim, T. Y., Park, J. S., Kim, S. S., and Lee, S. Y. (2014b). Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-arginine production. Nat. Commun. 5, 4618. doi:10.1038/ncomms5618

Peng, M., and Liang, Z. (2020). Degeneration of industrial bacteria caused by genetic instability. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 36, 119. doi:10.1007/s11274-020-02901-7

Pfeifer, E., Michniewski, S., Gätgens, C., Münch, E., Müller, F., Polen, T., et al. (2019). Generation of a prophage-free variant of the fast-growing bacterium Vibrio natriegens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, 008533–e919. doi:10.1128/AEM.00853-19

Pósfai, G., Plunkett, G., Fehér, T., Frisch, D., Keil, G. M., Umenhoffer, K., et al. (2006). Emergent properties of reduced-genome Escherichia coli. Science 312, 1044–1046. doi:10.1126/science.1126439

Postma, E. D., Couwenberg, L. G. F., van Roosmalen, R. N., Geelhoed, J., de Groot, P. A., and Daran-Lapujade, P. (2022). Top-down, knowledge-based genetic reduction of yeast central carbon metabolism. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 13, e0297021. doi:10.1128/mbio.02970-21

Prell, C., Vonderbank, S. A., Meyer, F., Pérez-García, F., and Wendisch, V. F. (2022). Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for de novo production of 3-hydroxycadaverine. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 4, 32–46. doi:10.1016/j.crbiot.2021.12.004

Pšeničnik, A., Slemc, L., Avbelj, M., Tome, M., Šala, M., Herron, P., et al. (2024). Oxytetracycline hyper-production through targeted genome reduction of Streptomyces rimosus. mSystems 9, e0025024. doi:10.1128/msystems.00250-24

Qiao, W., Liu, F., Wan, X., Qiao, Y., Li, R., Wu, Z., et al. (2022). Genomic features and construction of streamlined genome chassis of nisin z producer Lactococcus lactis n8. Microorganisms 10, 47. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10010047

Qin, Q., Ling, C., Zhao, Y., Yang, T., Yin, J., Guo, Y., et al. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9 editing genome of extremophile Halomonas spp. Metab. Eng. 47, 219–229. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.018

Ravagnan, G., Lesemann, J., Müller, M.-F., Poehlein, A., Daniel, R., Noack, S., et al. (2024). Genome reduction in Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365 for chassis development. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1378873. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1378873

Raza, W., Makeen, K., Wang, Y., Xu, Y., and Qirong, S. (2011). Optimization, purification, characterization and antioxidant activity of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by Paenibacillus polymyxa SQR-21. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 6095–6103. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.033

Rehm, B. H. A. (2010). Bacterial polymers: biosynthesis, modifications and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 578–592. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2354

Reuß, D. R., Altenbuchner, J., Mäder, U., Rath, H., Ischebeck, T., Sappa, P. K., et al. (2017). Large-scale reduction of the Bacillus subtilis genome: consequences for the transcriptional network, resource allocation, and metabolism. Genome Res. 27, 289–299. doi:10.1101/gr.215293.116

Rogelj, J., Schaeffer, M., Meinshausen, M., Knutti, R., Alcamo, J., Riahi, K., et al. (2015). Zero emission targets as long-term global goals for climate protection. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 105007. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/10/105007

Rütering, M., Cress, B. F., Schilling, M., Rühmann, B., Koffas, M. A. G., Sieber, V., et al. (2017). Tailor-made exopolysaccharides-CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing in Paenibacillus polymyxa. Synth. Biol. 2, ysx007. doi:10.1093/synbio/ysx007

Rütering, M., Schmid, J., Rühmann, B., Schilling, M., and Sieber, V. (2016). Controlled production of polysaccharides-exploiting nutrient supply for levan and heteropolysaccharide formation in Paenibacillus sp. Carbohydr. Polym. 148, 326–334. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.074

Rütering, M., Schmid, J., Gansbiller, M., Braun, A., Kleinen, J., Schilling, M., et al. (2018). Rheological characterization of the exopolysaccharide Paenan in surfactant systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 181, 719–126. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.11.086

Sasaki, M., Kumagai, H., Takegawa, K., and Tohda, H. (2013). Characterization of genome-reduced fission yeast strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 5382–5399. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt233

Satam, H., Joshi, K., Mangrolia, U., Waghoo, S., Zaidi, G., Rawool, S., et al. (2023). Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biol 12, 997. doi:10.3390/biology12070997

Schilling, C., Ciccone, R., Sieber, V., and Schmid, J. (2020). Engineering of the 2,3-butanediol pathway of Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Metab. Eng. 61, 381–388. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2020.07.009

Schilling, C., Gansbiller, M., Rühmann, B., Sieber, V., and Schmid, J. (2023a). Rheological characterization of artificial paenan compositions produced by Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Carbohydr. Polym. 320, 121243. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121243

Schilling, C., Klau, L. J., Aachmann, F. L., Rühmann, B., Schmid, J., and Sieber, V. (2022). Structural elucidation of the fucose containing polysaccharide Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Carbohydr. Polym. 278, 118951. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118951

Schilling, C., Klau, L. J., Aachmann, F. L., Rühmann, B., Schmid, J., and Sieber, V. (2023b). CRISPR-Cas9 driven structural elucidation of the heteroexopolysaccharides from Paenibacillus polymyxa DSM 365. Carbohydr. Polym. 312, 120763. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120763

Schilling, C., Koffas, M. A. G., Sieber, V., and Schmid, J. (2021). Novel prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas12a-based tool for programmable transcriptional activation and repression. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 3353–3363. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00424

Schilling, T., Ferrero-Bordera, B., Neef, J., Maaβ, S., Becher, D., and van Dijl, J. M. (2023c). Let there Be light: genome reduction enables Bacillus subtilis to produce disulfide-bonded gaussia luciferase. ACS Synth. Biol. 12, 3656–3668. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.3c00444

Schito, S., Zuchowski, R., Bergen, D., Strohmeier, D., Wollenhaupt, B., Menke, P., et al. (2022). Communities of Niche-optimized Strains (CoNoS) – design and creation of stable, genome-reduced co-cultures. Metab. Eng. 73, 91–103. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2022.06.004

Schmitt, I., Meyer, F., Krahn, I., Henke, N. A., Peters-Wendisch, P., and Wendisch, V. F. (2023). From aquaculture to aquaculture: production of the fish feed additive astaxanthin by Corynebacterium glutamicum using aquaculture sidestream. Molecules 28, 1996. doi:10.3390/molecules28041996

Sengupta, A., Bandyopadhyay, A., Sarkar, D., Hendry, J. I., Liu, D., Church, G. M., et al. (2024). Genome streamlining to improve performance of a fast-growing cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973. mBio 15, e0353023. doi:10.1128/mbio.03530-23

Shao, Y., Lu, N., Wu, Z., Cai, C., Wang, S., Zhang, L. L., et al. (2018). Creating a functional single-chromosome yeast. Nature 560, 331–335. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0382-x

Shen, R., Yin, J., Ye, J. W., Xiang, R. J., Ning, Z. Y., Huang, W. Z., et al. (2018). Promoter engineering for enhanced P(3HB- co-4HB) production by Halomonas bluephagenesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 1897–1906. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.8b00102

Shen, X., Wang, Z., Huang, X., Hu, H., Wang, W., and Zhang, X. (2017). Developing genome-reduced Pseudomonas chlororaphis strains for the production of secondary metabolites. BMC Genomics 18, 715. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-4127-2

Shi, F., Fan, Z., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Tan, S., and Li, Y. (2020). Optimization of ribosomal binding site sequences for gene expression and 4-hydroxyisoleucine biosynthesis in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 140, 109622. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2020.109622

Suárez, R. A., Stülke, J., and Van Dijl, J. M. (2019). Less is more: toward a genome-reduced Bacillus cell factory for “difficult Proteins”. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 99–108. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.8b00342

Sun, H., Zhang, J., Liu, W., E, W., Wang, X., Li, H., et al. (2022). Identification and combinatorial engineering of indole-3-acetic acid synthetic pathways in Paenibacillus polymyxa. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 15, 81. doi:10.1186/s13068-022-02181-3

Suzuki, N., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005a). New multiple-deletion method for the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome, using a mutant lox sequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8472–8480. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8472-8480.2005

Suzuki, N., Okayama, S., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005b). Large-scale engineering of the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3369–3372. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.6.3369-3372.2005

Tan, D., Xue, Y. S., Aibaidula, G., and Chen, G. Q. (2011). Unsterile and continuous production of polyhydroxybutyrate by Halomonas TD01. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 8130–8136. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.05.068

Tan, S., Shi, F., Liu, H., Yu, X., Wei, S., Fan, Z., et al. (2020). Dynamic control of 4-hydroxyisoleucine biosynthesis by modified l-isoleucine biosensor in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 2378–2389. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00127

Tao, W., Lv, L., and Chen, G. Q. (2017). Engineering Halomonas species TD01 for enhanced polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis via CRISPRi. Microb. Cell Fact. 16, 48. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0655-3

Unthan, S., Baumgart, M., Radek, A., Herbst, M., Siebert, D., Brühl, N., et al. (2015). Chassis organism from Corynebacterium glutamicum - a top-down approach to identify and delete irrelevant gene clusters. Biotechnol. J. 10, 290–301. doi:10.1002/biot.201400041

Valappil, S. P., Misra, S. K., Boccaccini, A., and Roy, I. (2006). Biomedical applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates, an overview of animal testing and in vivo responses. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 3, 853–868. doi:10.1586/17434440.3.6.853

Van Tilburg, A. Y., Van Heel, A. J., Stülke, J., De Kok, N. A. W., Rueff, A. S., and Kuipers, O. P. (2020). Mini Bacillus PG10 as a convenient and effective production host for lantibiotics. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 1833–1842. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00194

Voigt, C. A. (2020). Synthetic biology 2020–2030: six commercially-available products that are changing our world. Nat. Commun. 11, 6379. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20122-2

Walter, T., Al Medani, N., Burgardt, A., Cankar, K., Ferrer, L., Kerbs, A., et al. (2020). Fermentative n-methylanthranilate production by engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microorganisms 8, 866–920. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8060866

Wang, B., Hu, Q., Zhang, Y., Shi, R., Chai, X., Liu, Z., et al. (2018a). A RecET-assisted CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Cell Fact. 17, 63. doi:10.1186/s12934-018-0910-2

Wang, H., Liang, J., Yue, Q., Li, L., Shi, Y., Chen, G., et al. (2021a). Engineering the acyltransferase domain of epothilone polyketide synthase to alter the substrate specificity. Microb. Cell Fact. 20, 86. doi:10.1186/s12934-021-01578-3

Wang, H., Shi, Y., Liang, J., Zhao, G., and Ding, X. (2023). Disruption of hrcA, the repression gene of groESL and rpoH, enhances heterologous biosynthesis of the nonribosomal peptide/polyketide compound epothilone in Schlegelella brevitalea. Biochem. Eng. J. 194, 108878. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2023.108878