95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. , 15 February 2023

Sec. Synthetic Biology

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1138376

Baodong Hu1,2,3,4

Baodong Hu1,2,3,4 Xinrui Zhao1,2,3,4*

Xinrui Zhao1,2,3,4* Jingwen Zhou1,2,3,4

Jingwen Zhou1,2,3,4 Jianghua Li1,2,3,4

Jianghua Li1,2,3,4 Jian Chen1,2,3,4

Jian Chen1,2,3,4 Guocheng Du1,2,3,4,5*

Guocheng Du1,2,3,4,5*The hydroxylation is an important way to generate the functionalized derivatives of flavonoids. However, the efficient hydroxylation of flavonoids by bacterial P450 enzymes is rarely reported. Here, a bacterial P450 sca-2mut whole-cell biocatalyst with an outstanding 3′-hydroxylation activity for the efficient hydroxylation of a variety of flavonoids was first reported. The whole-cell activity of sca-2mut was enhanced using a novel combination of flavodoxin Fld and flavodoxin reductase Fpr from Escherichia coli. In addition, the double mutant of sca-2mut (R88A/S96A) exhibited an improved hydroxylation performance for flavonoids through the enzymatic engineering. Moreover, the whole-cell activity of sca-2mut (R88A/S96A) was further enhanced by the optimization of whole-cell biocatalytic conditions. Finally, eriodictyol, dihydroquercetin, luteolin, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone, as examples of flavanone, flavanonol, flavone, and isoflavone, were produced by whole-cell biocatalysis using naringenin, dihydrokaempferol, apigenin, and daidzein as the substrates, with the conversion yield of 77%, 66%, 32%, and 75%, respectively. The strategy used in this study provided an effective method for the further hydroxylation of other high value-added compounds.

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s, CYPs) are heme-containing enzymes that catalyze various types of chemical reactions on a variety of substrates (Hu et al., 2022b). Importantly, they are able to catalyze the regioselective and stereoselective oxidations of C-H bonds (Urlacher and Girhard, 2019). P450s are thought to be reliable, effective, and ecofriendly biocatalysts for the synthesis of valuable compounds in recombinant hosts. In addition, compared to the utilization of purified or extracted P450s, whole-cell biotransformation has shown a clear advantage by providing the necessary precursors, the expensive cofactors NAD(P)H, and suitable environments for catalytic reactions (Hu et al., 2022a). Moreover, to exploit the versatile P450s for industrial applications, Escherichia coli is a widely applied and efficient system for whole-cell biotransformation (Park et al., 2020).

Compared to the eukaryotic P450s, the bacterial P450s are cytosolic, presenting practical advantages for biotechnological applications (Moody and Loveridge, 2014). The largest genus of actinobacteria, Streptomyces, produce 70%–80% of the natural bioactive compounds (Berdy, 2005). The Streptomyces genomes provide a rich source of P450s that can generate a variety of novel compounds (Lamb et al., 2013). There are at least 17 subfamilies of CYP105 in Streptomycetes, which play important roles in the biotransformation or degradation of xenobiotics, and the biosynthesis of numerous bioactive compounds (Moody and Loveridge, 2014). For example, vitamin D3 can be converted to its active form (1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) by CYP105A1 (Sawada et al., 2004). In addition, the CYP105 family has shown great potential for industrial applications (Yasuda et al., 2018). An important cholesterol-lowering drug, pravastatin, is produced by the stereoselective hydroxylation of mevastatin by CYP105A3 (P450 sca-2) in S. carbophilus (Watanabe et al., 1995). The activity of mutant (G52S/T85F/F89I/T119S/P159A/V194N/D269E/T323A/N363Y/E370V) increased by 29.3-fold compared to the wild type P450 sca-2 (Ba et al., 2013b). Moreover, CYP105D7 showed a broad spectrum of substrates, including pentalenic acid (Takamatsu et al., 2011), diclofenac (Xu et al., 2015), daidzein (Pandey et al., 2010), naringenin (Liu et al., 2016), compactin (Yao et al., 2017), testosterone (Ma et al., 2019), and capsaicin (Ma et al., 2021).

Flavonoids are one of the largest known groups of natural products, which are widely found in the plants (Havsteen, 2002). They have a phenyl benzopyrone structure (C6-C3-C6) and are mainly classified as flavones, flavanols, flavanones, flavanonols, and isoflavones (Figure 1) (Middleton et al., 2000). They exhibit therapeutic and chemo-preventive effects on human health, including antioxidant activity (PG, 2000), antimicrobial activity (Cushnie and Lamb, 2005), anti-inflammatory activity (Pan et al., 2010), and anti-cancer properties (Ravishankar et al., 2013). In addition, they can be served as potential drug candidates to treat symptoms associated with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection (Adhikari et al., 2021). However, the low water solubility and instability limit the pharmaceutical application of these flavonoid compounds (Chu et al., 2016). Hydroxylation is a common strategy to improve their solubility and stability (Lin and Yan, 2014). Moreover, the structural diversity and biological activity of flavonoids also can be improved through hydroxylation. For example, 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone, the 3′-hydroxylated product of daidzein, exhibits better anti-cancer properties than daidzein and plays an essential role in suppressing ultraviolet B-induced skin cancer (Lee et al., 2011).

Biocatalytic hydroxylation is an environmentally friendly approach compared to the chemical hydroxylation. Flavonoids 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), responsible for the hydroxylation of flavonoids in plants, has been well studied (Gao et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Park et al., 2022b). However, the plant-derived P450s have low activity in prokaryotic hosts (Gao et al., 2020; Park et al., 2022b). Currently, the hydroxylation of flavonoids has not been well achieved in bacteria. Several bacterial P450s, including P450 BM3 (Chu et al., 2016), CYP105D7 (Liu et al., 2016), CYP107P2 (Pandey et al., 2011), CYP107Y1 (Pandey et al., 2011), and CYP105A5 (Subedi et al., 2022), have been explored to hydroxylate selected flavonoids with a low conversion rate.

In this study, we report a bacterial whole-cell biocatalyst for the efficient hydroxylation of a variety of flavonoids. At first, the bacterial P450 sca-2mut exhibiting outstanding 3′-hydroxylation activity towards flavonoids was selected from five P450s candidates. Then, the whole-cell activity of sca-2mut towards flavonoids was enhanced by employing a new combination of redox partners and enzymatic engineering of sca-2mut. Subsequently, the whole-cell activity was further enhanced by the optimization of whole-cell biocatalytic conditions. Finally, the whole-cell sca-2mut biocatalyst was applied to efficiently produce eriodictyol, dihydroquercetin, luteolin, 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone as examples of flavanone, flavanonol, flavone, and isoflavone, respectively.

E. coli DH5α and C41(DE3) were used as hosts for DNA cloning and whole-cell biotransformation, respectively. Primer STAR HS DNA polymerase and restriction endonucleases were obtained from Takara (Dalian, China). DNA and genomic DNA Extraction Kits were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, United States) and TIANGEN (Beijing, China), respectively. The plasmid miniprep purification kit was purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Oligonucleotide synthesis and sequence analysis were achieved by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). ALA and hemin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). Naringenin, eriodictyol, dihydrokaempferol, dihydroquercetin, kaempferol, quercetin, apigenin, luteolin, daidzein, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone were purchased from Yuanye Bio-Technology (Shanghai, China). Other chemicals were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and were of the highest commercial grade available.

All the plasmids, primers, and strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables S1–S3, respectively.

The genes encoding CYP105D7 from S. avermitilis (Liu et al., 2016), CYP105A3 (variant III; G52S/T85F/F89I/T119S/P159A/V194N/D269E/T323A/N363Y/E370V; named sca-2mut) from S. carbophilus (Ba et al., 2013b), CYP 105P2 from S. peucetius (Niraula et al., 2012), CYP105A1 (R73A/R84A; named CYP105A1mut) from S. griseolus (Yasuda et al., 2017), CYP105AB3 (Q87W/T115A/H132L/R191W/G294D; named moxAmut) from Nonomuraea recticatena (Kabumoto et al., 2009), putidaredoxin reductase (CamA) and putidaredoxin (CamB) from Pseudomonas putida (Ba et al., 2013a) were codon optimized and synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China). To construct the whole-cell biocatalytic system for the hydroxylation of flavonoids, camB-camA genes were first subcloned into the Nco I/Sal I of plasmid pRSFDuet-1 to generate plasmid pRSF-CamA-CamB. Subsequently, CYP105P2, CYP105D7, moxAmut, CYP105A1mut, and sca-2mut genes were individually subcloned into the Nde I/Xho I of plasmid pRSF-CamA-CamB to generate plasmids pRSF-105P2-CamA-CamB, pRSF-105D7-CamA-CamB, pRSF-moxAmut-CamA-CamB, pRSF-105A1mut-CamA-CamB, and pRSF-sca-2mut-CamA-CamB, respectively.

To investigate the effect of different redox partners on the catalytic performance of sca-2mut towards flavonoids, other redox partners were selected and optimized. First, using the plasmid donated by Professor Shengying Li from Shandong University as a template, the genes encoding ferredoxin Fdx_1499 and the ferredoxin reductase FdR_0978 from Synechococcus elongates PCC7942 (Zhang et al., 2018) were obtained by PCR using primers Fdx_1499-RH-F/Fdx_1499-RH-R and FdR_0978-RH-F/FdR_0978-RH-R, respectively. These two obtained fragments were fused by overlap extension PCR (Horton et al., 1993), and subsequently inserted into the Nco I/Sal I of plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut to generate plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-Fdx_1499-FdR_0978. In the same way, the gene encoding flavodoxin reductase Fpr (GenBank: QJZ14319.1) from E. coli in combination with the genes encoding endogenous flavodoxin Fld (GenBank: QJZ13227.1), FldA (GenBank: QJZ11404.1) (Bakkes et al., 2015), or FldB (GenBank: QJZ13309.1), were used to construct plasmids pRSF-sca-2mut-Fld-Fpr, pRSF-sca-2mut-FldA-Fpr, and pRSF-sca-2mut-FldB-Fpr, respectively. Furthermore, the gene encoding E. coli Fpr grouped with the genes encoding flavodoxin YkuN (Gene ID: 939194) or flavodoxin YkuP (Gene ID:938811) from Bacillus subtilis (Bakkes et al., 2017), were inserted into the Nco I/Sal I of plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut to generate plasmids pRSF-sca-2mut-YkuN-Fpr and pRSF-sca-2mut-YkuP-Fpr, respectively. In addition, the fused enzyme (sca-2mut-BM3) was constructed by fusing the heme domain of sca-2mut and the reductase domain of P450 BM3 from Bacillus megaterium. Fragments of gene sca-2mut and the reductase domain of BM3 were obtained by PCR using primers Sca2-RH-F/Sca2-RH-R and BM3-RH-F/BM3-RH-R, respectively. The products of amplification were fused by overlap extension PCR and subsequently inserted into the Nde I/Xho I of pRSFDuet-1 to generate plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-BM3.

To construct the mutants of sca-2mut (plasmids sca-2mutR77A-Fld-Fpr, sca-2mutR88A-Fld-Fpr, sca-2mutR93A-Fld-Fpr, sca-2mutG95A-Fld-Fpr, sca-2mutS96A-Fld-Fpr, sca-2mutR197A-Fld-Fpr, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr), the fragments were obtained by PCR using the primers (Supplementary Table S2) with plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-Fld-Fpr as a template, and the obtained PCR products were assembled by Gibson assembly (Gibson et al., 2009).

To construct the plasmid ADB-N-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr, the zinc finger proteins ADB1 (RSNR-RDHT-VSTR-QSNI), ADB2 (VSSR-RSHR-RSNR-CSNR), and ADB3 (QSSR-RSHR-RHHR-QTHQ) (Xu et al., 2020) were fused to the N terminus of Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A, respectively (primers in Supplementary Table S2). Using the same approach, the zinc finger proteins ADB1, ADB2, and ADB3 were fused to the N terminus of Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A, respectively, to generate plasmid ADB-C-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr. To construct the plasmids Lig-N-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr and Lig-C-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr, the ligands of GBD, SH3, and PDZ were fused to the N terminus or C terminus of Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A, respectively (primers in Supplementary Table S2). Plasmid DNA scaffold was constructed by PCR using primers DNA-scaffold-F/DNA-scaffold-R with plasmid pACYCDuet-1 as a template. Plasmids protein scaffold, CipA-N-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr, CipA-C-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr, CipB-N-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr, and CipB-C-sca-2mutR88A/S96A-Fld-Fpr were codon optimized and synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China).

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, and pH 7.0) was used for cloning and seeding cultures. To obtain seed cultures, colonies of the recombination strain grown from LB agar plates (2% agar, w/v) were inoculated into 50 mL test tubes containing 5 mL LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated in a rotary shaker at 37°C and 220 rpm for 12 h. 1 mL of the seed cultures was transferred to 250 mL shaking flasks containing 50 mL Terrific Broth (TB) medium (12 g/L tryptone, 24 g/L yeast extract, 0.4% v/v glycerol, 0.017 M KH2PO4, and 0.072 M K2HPO4) supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 100 mg/L ALA and 20 mg/L FeSO4·7H2O, and the cultures were then incubated at 37°C and 220 rpm. When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6-0.8, 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to induce enzyme expression. After induction, the cultures were incubated at 25°C for 20 h.

For cultivation of HFLA-20 to HFLA-23 strains, 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol were added into the medium.

After cultivation, 50 mL of cells were harvested by centrifugation (8,000 rpm, 10 min), then washed twice with potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 8.0), and subsequently resuspended with 25 mL potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 8.0) containing 10% glycerol or 10% glucose. 25 mL of cell suspension (30 OD600) was used for the whole-cell biocatalysis in 250 mL shaking flasks.

To examine the catalytic efficiency of hydroxylation of flavonoids, naringenin, dihydrokaempferol, kaempferol, apigenin, and daidzein (5 g/L in ethanol) was added to the cell suspension to give the final concentration of 100 mg/L, respectively. Whole-cell biocatalysis were performed at 30°C and 220 rpm for 12 h. Then, 1 mL of the whole-cell biocatalytic reaction solution was collected and extracted thrice with 1 mL ethyl acetate. The products were dried, dissolved in methanol, and subsequently analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

To optimize biocatalytic conditions, 25 mL of the cell suspension (30 of OD600) was used for the bioconversion reaction in 250 mL shaking flasks. To investigate the effect of temperature on the catalytic activity, reactions were performed at pH 8.0 with the temperature ranging from 20°C to 40°C. To optimize pH, reactions were performed at 37°C and 220 rpm in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0-8.0) or Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0).

A homology model of sca-2mut and sca-2mutR88A/S96A was constructed using the highly homologous template CYP105A1 (PDB code 2ZBX, 75.1% identity) (Sugimoto et al., 2008) in Discovery Studio 2019 (DS 2019). The predicted structures for sca-2mut and sca-2mutR88A/S96A were evaluated by UCLA−DOE LAB-SAVES v6.0 web server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). Molecular docking analysis was performed using the CDOCKER tool of DS 2019.

Cell growth was detected by measuring OD600 using a spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan).

Naringenin, eriodictyol, dihydrokaempferol, dihydroquercetin, kaempferol, quercetin, apigenin, luteolin, daidzein, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone were quantified using an Agilent 1260 HPLC instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) equipped with ultraviolet/VIS detector. A reverse-phase column ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, Agilent, United States) was used to monitor the absorbance at 290 nm. Elution was performed with mobile phase A consisting water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and mobile phase B consisting methanol containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The flow rate was set as 0.8 ml·min-1 and the solvent gradient was adopted as follow: 0–1 min, isocratic at 10% B; 1–10 min, 10%–40% B; 10–20 min, 40%–60% B; 20–23 min, 60% B; 23–25 min, 60%–10% B; 25–27 min, 10% B.

All experiments were performed with three biological replicates. The data were analyzed by the software GraphPad Prism 8.0 and displayed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD) from triplicate experiments.

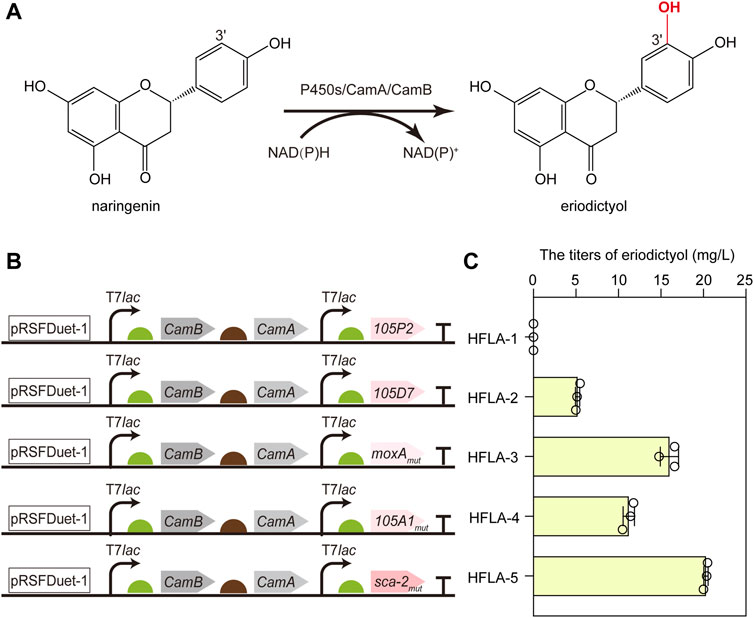

To screen the efficient bacterial P450s for the hydroxylation of flavonoids, CYP105D7 from S. avermitilis (Liu et al., 2016), sca-2mut (CYP105A3) from S. carbophilus (Ba et al., 2013b), CYP105P2 from S. peucetius (Niraula et al., 2012), CYP105A1mut from S. griseolus (Yasuda et al., 2017), and moxAmut (CYP105AB1) from N. recticatena (Kabumoto et al., 2009) were chosen as candidates to investigate the catalytic performance toward flavonoids. Since the CYP105 family is a three-component P450 enzyme, the most widely studied redox partners CamA (putidaredoxin reductase) and CamB (putidaredoxin) were employed in the whole-cell biocatalysis to transfer electrons from NAD(P)H to the heme-iron reactive center for O2 activation. Thus, the genes encoding CamA and CamB were co-expressed with these five P450s genes using a pRSFDuet-1 plasmid in the C41(DE3) strain (Hu et al., 2022a), respectively, resulting in HFLA-1 to HFLA-5 strains. Subsequently, the hydroxylation of flavonoids by whole-cell as biocatalysts was compared using naringenin as a model substrate (Figures 2A, B).

FIGURE 2. Screening of the efficient bacterial P450s for the hydroxylation of flavonoids. (A) Schematic representation of the regioselective hydroxylation of naringenin by P450s with redox partners of CamA and CamB. (B) Schematic diagram of combining different P450s and redox partners to construct whole-cell biocatalyst plasmids. P450s included CYP105P2, CYP105D7, P450 moxAmut, CYP105A1mut, and P450 sca-2mut. (C) Titers of eriodictyol produced by whole-cell biocatalysts of different P450s using 100 mg/L naringenin. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

Except the HFLA-1 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-105P2-CamA-CamB), the other four strains can catalyze hydroxylation at C-3′ of naringenin to produce eriodictyol (Figure 2C). A titer of 5.2 ± 0.3 mg/L eriodictyol was produced by the HFLA-2 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-105D7-CamA-CamB) using 100 mg/L of naringenin as a substrate, which was comparable to that previously reported (10.3% of conversion rate using 0.15 mM naringenin) (Liu et al., 2016). Since the quintuple mutant Q87W/T115A/H1432L/R194W/G294D showed 4.3-fold higher activity towards naringenin than the wild-type moxA (Kabumoto et al., 2009), a higher level of eriodictyol (16.0 ± 1.1 mg/L) was obtained by the HFLA-3 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-moxAmut-CamA-CamB). Furthermore, 11.2 ± 0.7 and 20.3 ± 0.3 mg/L eriodictyol were produced by the HFLA-4 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-105A1mut-CamA-CamB) and the HFLA-5 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-CamA-CamB), respectively, which were the first report of eriodictyol production by CYP105A1 and P450 sca-2 through hydroxylation at the C-3′ of naringenin. In particular, sca-2mut showed the best catalytic performance in the C-3′ hydroxylation of naringenin, and the titer of eriodictyol produced by the HFLA-5 strain was 3.9-, 1.3-, and 1.8-fold higher than that produced by the HFLA-2 strain, the HFLA-3 strain, and the HFLA-4 strain. Therefore, sca-2mut was selected for efficient hydroxylation of flavonoids.

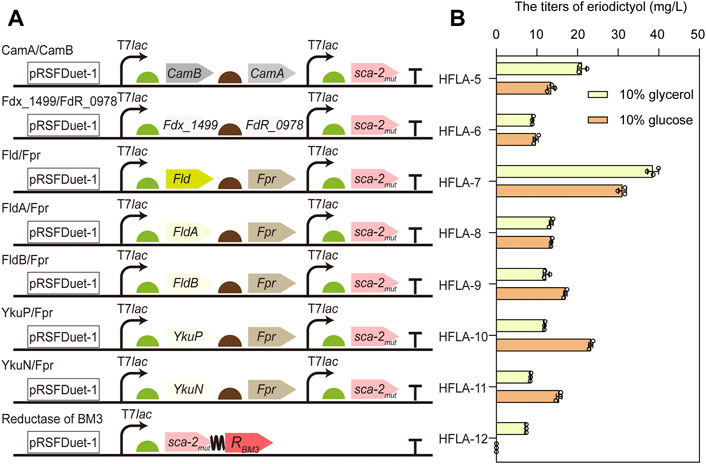

For the common bacterial three-component P450s, the process of transferring electron by redox partner is important for catalysis. However, the optimal redox partners for sca-2mut are unknown (Zhang et al., 2018). To obtain the suitable redox partners for the hydroxylation of flavonoids by P450 sca-2mut, the different combinations of flavodoxin and flavodoxin reductase were used to reconstitute the activity of P450 sca-2mut, including the electron transfer proteins flavodoxin (Fld, FldA, or FldB) from E. coli in combination with the endogenous flavodoxin reductase Fpr (Bakkes et al., 2015), respectively, the flavodoxin (YkuN or YkuP) (Girhard et al., 2010) from B. subtilis in combination with E. coli Fpr, respectively, and the ferredoxin Fdx_1499 and ferredoxin reductase FdR_0978 from S. elongates PCC7942 (Sun et al., 2017) (Figure 3A). In addition, the chimeric protein was constructed by fusing the P450 sca-2mut to the reductase domain of P450BM3 from B. megaterium (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3. Improving the catalytic activity of sca-2mut by engineering redox partners. (A) Schematic representation of combining sca-2mut with different redox partners to reconstitute the activity of sca-2mut. Redox partners included Fdx_1499/FdR_0978, Fld/Fpr, FldA/Fpr, FldB/Fpr, YkuP/Fpr, YkuN/Fpr, and the reductase domain of BM3. (B) Titers of eriodictyol produced by different sca-2mut whole-cell biocatalysts with different redox partners using 100 mg/L naringenin. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

The plasmids harboring the genes encoding different redox partners were transformed into the C41(DE3) strain, resulting in HFLA-6 to HFLA-12 strains. Subsequently, their performances in the hydroxylation of flavonoids were investigated using a final concentration of 100 mg/L naringenin as a substrate. Whole-cell biocatalysis was performed in potassium phosphate buffer containing glucose (1%, 2%, and 10% w/v) or glycerol (10% v/v), respectively. The seven strains showed similar catalytic activity toward naringenin in the biocatalytic systems containing 1%, 2%, and 10% w/v of glucose (Supplementary Figure S1). The HFLA-7 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-Fld-Fpr) had both the best catalytic performance towards naringenin in glycerol or glucose containing biocatalytic system, producing 38.6 ± 1.4 or 31.1 ± 1.0 mg/L eriodictyol, respectively (Figure 3B). This result suggested that glycerol was more beneficial to the catalytic efficiency than glucose in the whole-cell biocatalysis of HFLA-7 strain. Notably, the E. coli flavodoxin Fld was used in combination with Fpr for the first time to reconstitute the activity of P450s. In the recent study, FdR_0978/Fdx_1499 was the most promising redox partner for the in vitro activity of sca-2 towards mevastatin compared to the redox systems Adx/AdR and Pdx/PdR (Liu et al., 2022). However, the HFLA-6 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-Fdx_1499-FdR_0978) produced 8.9 ± 0.2 and 9.7 ± 0.6 mg/L eriodictyol in the in vivo biocatalytic system containing glycerol or glucose, which were only 23.1% and 31.2% of the HFLA-7 strain, respectively (Figure 3B). Therefore, the HFLA-7 strain was used for the following improvement.

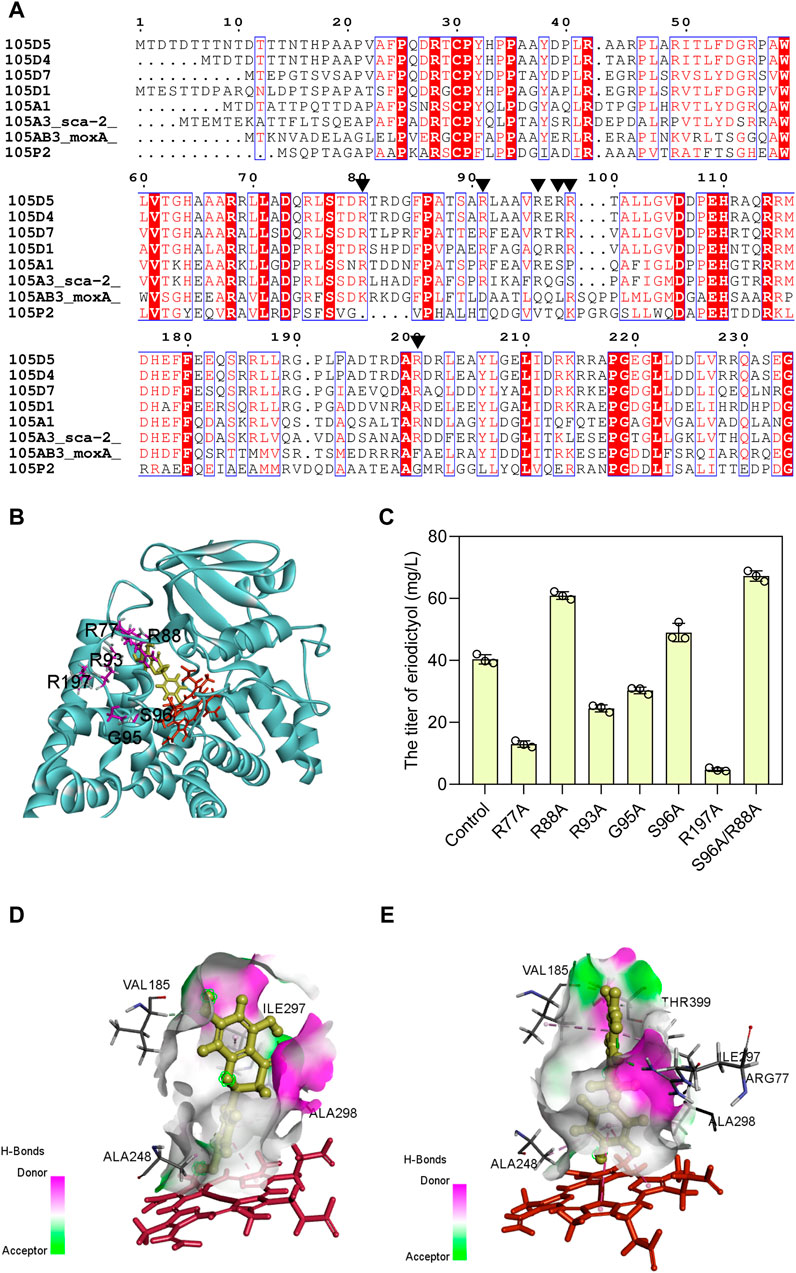

Based on the evolutionary information encapsulated in homologous protein sequences, the approach of consensus design has been employed to improve the stability (Porebski and Buckle, 2016) and activity (Yao et al., 2022) of proteins. Hence, the mutagenesis was designed to obtain the sca-2 variants by consensus design. Multiple sequence alignment was performed on the CYP105 family and the conserved arginine residues around the active site pocket were shown as red boxes (Figure 4A). CYP105D7, sharing 53% identity of amino acid sequence with sca-2, has four arginine residues (Arg70, Arg81, Arg88, and Arg190) that form a wall of the substrate-binding pocket (Xu et al., 2015), and the double mutant R70A/R190A has a nearly 9-fold increase in the in vivo conversion rate of testosterone (Ma et al., 2019). The distal pocket of CYP105A1 contains three Arg residues (Arg73, Arg84, and Arg193) (Sugimoto et al., 2008), and the double mutant R73A/R84A exhibited a 319-fold higher Kcat/Km for 25-hydroxylation towards the substrate 1α(OH) vitamin D3 (Hayashi et al., 2008). Based on these simulated results, six residues of sca-2mut (Arg77, Arg88, Arg93, Gly95, Ser 96, and Arg197) (Figure 4B) were mutated, and the catalytic performance of the mutants on naringenin were examined.

FIGURE 4. Enhancing the catalytic activity of sca-2mut by sequence-guided engineering. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment using the representative CYP105 family. Black triangle indicates the conserved arginine residues on the surface of an active site. (B) Selection of amino acids used as mutations (R77, R88, R93, G95, S96, and R197) are positioned around the substrate area of sca-2. (C) Titers of eriodictyol produced by engineering strains containing sca-2 mutants. (D) The interactions between naringenin and sca-2mut model. (E) The interactions between naringenin and sca-2mutR88A/S96A model. Heme was indicated as red and ligand indicated as yellow. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

Two single mutants, sca-2mutR88A (HFLA-14 strain) and sca-2mutS96A (HFLA-17 strain), exhibited 58% and 27% significantly increase in catalytic activity for naringenin compared to the HFLA-7 strain (harboring plasmid pRSF-sca-2mut-Fld-Fpr), producing 60.9 ± 1.2 and 49.0 ± 2.9 mg/L eriodictyol using 100 mg/L naringenin as a substrate, respectively (Figure 4C). Then, the double mutant sca-2mutR88A/S96A (HFLA-19 strain) was constructed, and the catalytic activity was further increased by 10% compared to the best single mutant sca-2mutR88A (HFLA-14 strain), producing 67.2 ± 1.7 mg/L eriodictyol.

To analyze the reason for the enhanced yield, the homology models for the sca-2mut and mutant sca-2mutR88A/S96A were constructed and checked (Supplementary Figure S2). Subsequently, the analysis of molecular docking was performed using the CDOCKER tool of DS 2019 with substrate naringenin as the ligand (Figures 4D, E). Although the amino acids Arg 88 and Ser 96 did not directly interact with the substrate naringenin, the hydrogen bond around the substrate increased in the sca-2mut R88A/S96A model compared to the sca-2mut model (Figures 4D, E; Supplementary Figure S3). In addition, the increased hydrophobic interaction of Ala 88 and Ala 96 with surrounding amino acids may lead to a more flexible of substrate access (Supplementary Figure S4).

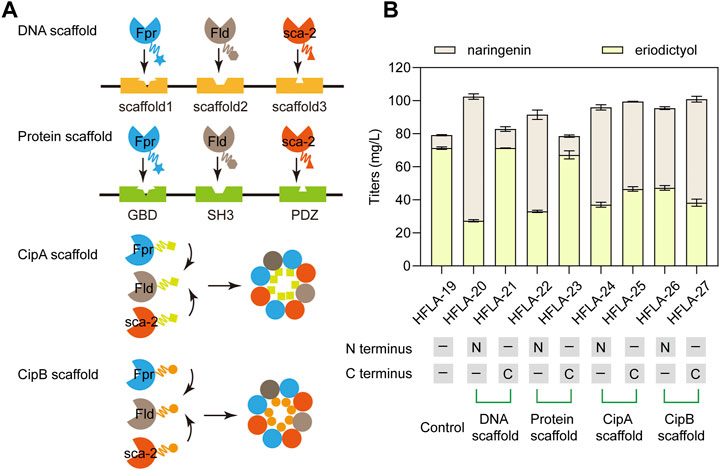

The efficient electron transfer between P450s and redox partners is important for the biosynthesis of natural products (Park et al., 2022a). Therefore, DNA scaffolds (Xu et al., 2020), Protein scaffolds (Dueber et al., 2009), Photorhabdus luminescens CipA scaffold (Wang et al., 2017), and P. luminescens CipB scaffold (Wang et al., 2017) were applied to assemble Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A. Different scaffolds were fused to the N terminus or C terminus of these three enzymes and their effects on the catalytic performance of naringenin were investigated. At first, DNA scaffolds, protein scaffolds, CipA scaffold, and CipB scaffold were respectively fused to the N terminus of Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A in the HFLA-19 strain to generate HFLA-20, HFLA-22, HFLA-24, and HFLA-26 strains (Figure 5A). The titers of eriodictyol in these four strains decreased by 33.7%–61.7% compared to the HFLA-19 strain, indicating that the scaffolds fused to the N terminus of the three enzymes resulted in an overall decrease in whole-cell activity (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5. Improvement of the electron transfer efficiency by different scaffolds. (A) Schematic representation of the assembly of P450s and redox partners by the DNA scaffolds, Protein scaffolds, CipA scaffold, and CipB scaffold, respectively. (B) Titers of eriodictyol produced by different sca-2mut whole-cell biocatalysts with the assembly of enzymes by scaffolds using 100 mg/L naringenin. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

Then, the scaffolds were fused to the C terminus of Fpr, Fld, and sca-2mutR88A/S96A in the HFLA-19 strain, respectively, obtaining the HFLA-21, HFLA-23, HFLA-25, and HFLA-27 strains. These four strains produced 100.1%, 94.8%, 65.3%, and 53.7% of the eriodictyol titers of the HFLA-19 strain, respectively, indicating that the use of scaffolds to assemble of P450s and redox partners did not further improve the titers of eriodictyol (Figure 5B). In the previous reports, these scaffolds were used to assemble enzymes to enhance the synthesis of natural products in growing cells (Dueber et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2020; Park et al., 2022a). During the fermentation of growing cells, products are synthesized from growth substrates by the natural metabolism of the host cells and are accompanied in the fermentation broth by metabolic intermediates that make downstream processing complicated (Ladkau et al., 2014; Lee and Kim, 2015). In biotransformation, the cell growth and production phase are separated, and the use of resting cells can convert substrates to desired products (Lin and Tao, 2017). In addition, the use of resting cells is a good alternative when the optimal pH, temperature, or medium composition for biotransformation differs from the values that allow optimal growth conditions (de Carvalho, 2017). Thus, the scaffolds were not suitable for the whole-cell catalysis with P450 sca-2mutR88A/S96A using resting cells.

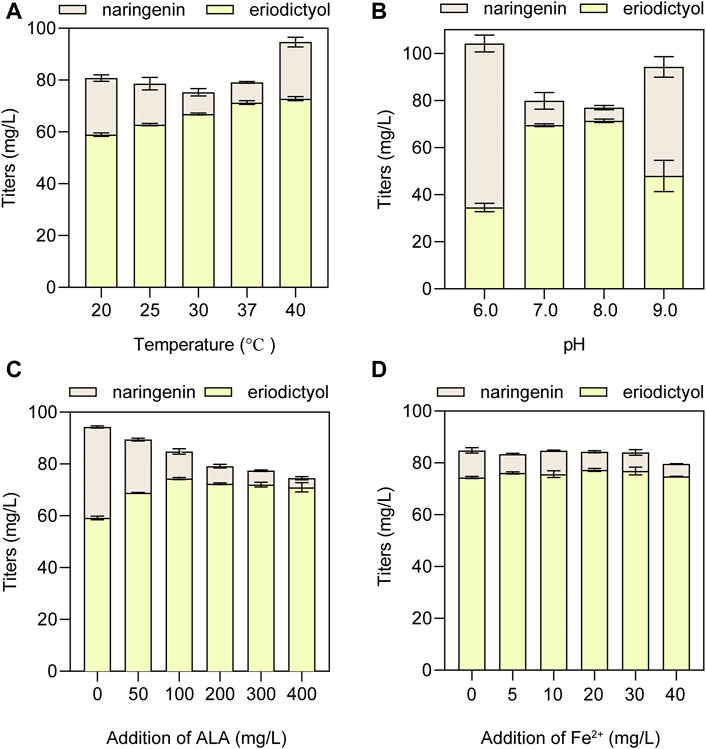

To obtain the optimal conditions of whole-cell biocatalysis, the suitable temperature and pH were optimized using the HFLA-19 biocatalyst. At first, the effect of biocatalytic temperature ranging from 20°C to 40°C on the production of eriodictyol was examined using 100 mg/L naringenin as a substrate. The results showed that the titer of eriodictyol increased with the increase of biocatalytic temperature (Figure 6A). 71.3 ± 0.7 mg/L of eriodictyol was produced at the biocatalytic temperature at 37°C, and the titer did not increase when the biocatalytic temperature was higher than 37°C. Subsequently, the effect of pH values ranging from 6.0 to 9.0 on the production of eriodictyol was examined, and the highest titer of eriodictyol (71.3 ± 0.7 mg/L) was obtained at pH 8.0°C and 37°C (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6. The optimization of whole-cell biocatalytic conditions for the HFLA-19 strain. (A) Effect of temperature on eriodictyol titer. (B) Effect of pH on eriodictyol titer. (C) Effect of ALA addition. (D) Effect of ferrous ion addition. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

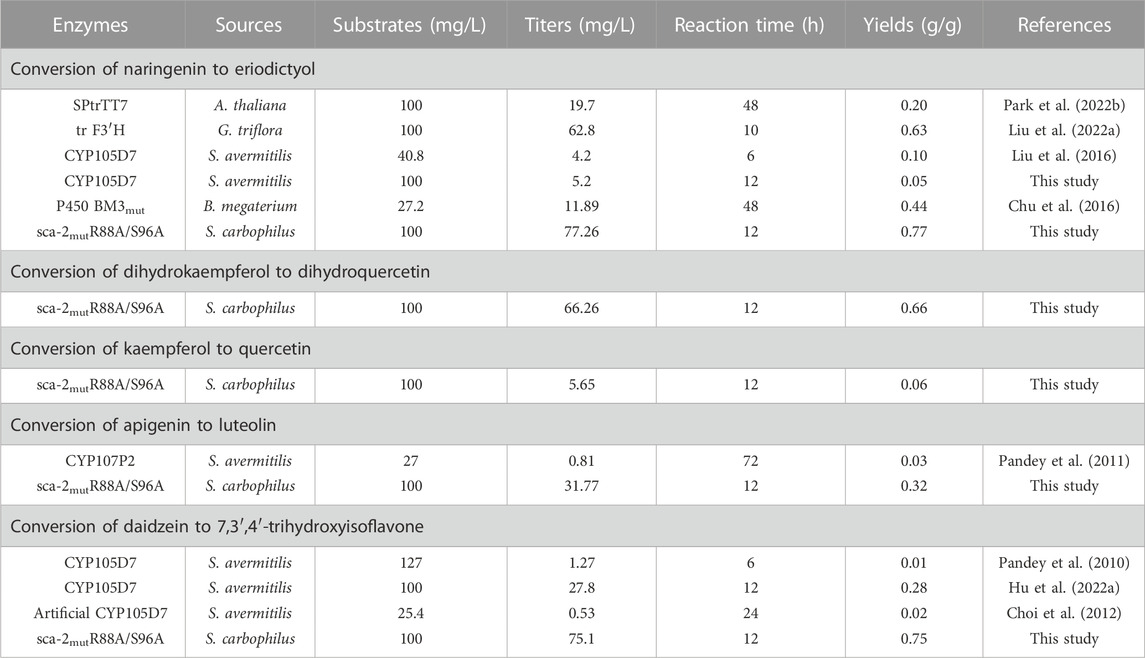

Since P450s are heme-containing enzymes, increasing the intracellular supply of heme can enhance the overall activity of whole-cell biocatalysts (Park and Choi, 2020). However, the direct addition of different final concentrations of heme (5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg/L) to the medium did not significantly increase the titer of eriodictyol due to the weak import of heme in the C41(DE3) strain (Supplementary Figure S5), which is consistent with the previous study (Zhao et al., 2022). Since the uptake of the heme precursor (5-aminolevulinic acid, ALA) was efficient in E. coli (Verkamp et al., 1993), the effect of adding different final concentrations of ALA (50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 mg/L) on biocatalysis was investigated. The highest titer of eriodictyol could reach 74.3 ± 0.4 mg/L when 100 mg/L ALA was added to the medium (Figure 6C). In addition, the supplementation with iron also helps in the synthesis of heme. Based on adding 100 mg/L ALA in the medium, different final concentrations of FeSO4·7H2O (5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg/L) were added into the medium, respectively, and 77.3 ± 0.6 mg/L eriodictyol was produced when 20 mg/L FeSO4·7H2O was supplied (Figure 6D). Hence, the 72.5% of molar conversion rate is higher than the highest molar conversion rate (59.3%) reported so far for the heterologous expression of the F3′H from Gentiana triflora and cytochrome P450 reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana in engineering E. coli (Table 1) (Liu et al., 2022).

TABLE 1. The overview of known recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell P450 biocatalysts used for the production of flavonoids.

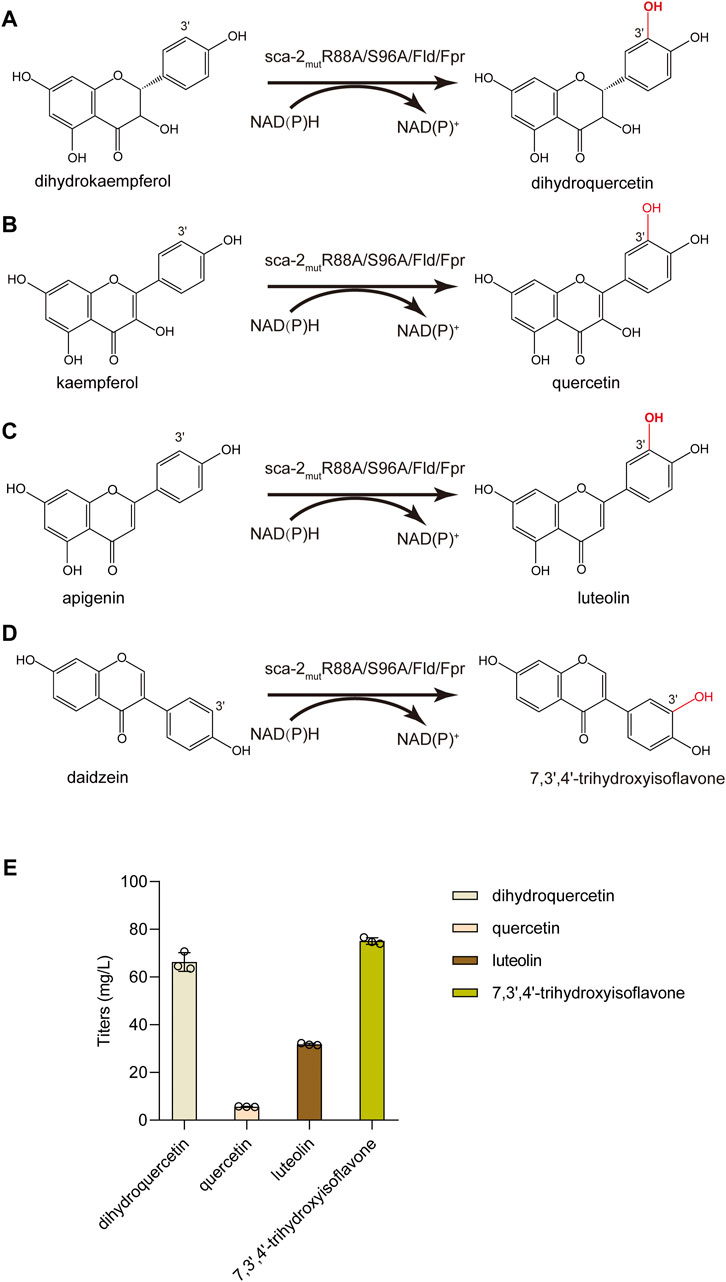

Besides naringenin (flavanone), the hydroxylation potential of sca-2mutR88A/S96A toward dihydrokaempferol (flavanonol), kaempferol (flavonol), apigenin (flavone), and daidzein (isoflavone) was investigated. The results of whole-cell biocatalysis of the HFLA-19 strain toward the four types of flavonoids were shown in Figure 7. The HFLA-19 whole-cell biocatalyst produced 66.3 ± 3.9 mg/L of dihydroquercetin (yield: 0.66 g/g), 5.7 ± 0.1 mg/L of quercetin (yield: 0.06 g/g), 31.8 ± 0.4 mg/L of luteolin (yield: 0.32 g/g), and 75.1 ± 1.4 mg/L of 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone (yield: 0.75 g/g), respectively, using 100 mg/L of dihydrokaempferol, kaempferol, apigenin, and daidzein as the substrates. The HFLA-19 whole-cell biocatalyst showed the efficient catalytic performance of C-3′ hydroxylation toward dihydrokaempferol, apigenin, and daidzein compared to the previously reported (Table 1). Notably, the conversion rates of dihydrokaempferol and daidzein by the HFLA-19 whole-cell catalysis were the highest reported so far.

FIGURE 7. Biocatalytic hydroxylation of different flavonoids. (A–D) Schematic representation of the enzymatic reactions catalyzed by sca-2mutR88A/S96A. (E) Titers of dihydroquercetin, quercetin, luteolin, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone produced by the HFLA-19 whole-cell biocatalyst. The data are shown as mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

In this study, an efficient bacterial whole-cell P450 biocatalyst was obtained by mining the suitable P450 enzymes, engineering redox partners, protein engineering, and the optimization of whole-cell biocatalytic conditions. By using the sca-2mutR88A/S96A whole-cell biocatalyst, eriodictyol, dihydroquercetin, quercetin, luteolin, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone were produced with the titers of 77.3, 66.3, 5.7, 31.8, and 75.1 mg/L, respectively, in a reaction system containing a final concentration of 100 mg/L substrate. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of C-3′ hydroxylation of flavonoids by P450 sca-2 (CYP105A3), expanding the substrate spectrum of sca-2. In addition, the conversion rates of eriodictyol, dihydroquercetin, luteolin, and 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone were the highest conversion rates obtained so far by whole-cell biocatalysis of P450s. This study demonstrates a versatile P450 whole-cell biocatalyst for the efficient hydroxylation of flavonoids, providing a potential biocatalyst for application in synthetic biology.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

XZ, JZ, JL, JC, and GD conceived the idea and designed for this work. BH performed experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. XZ and GD wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0906400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900067), and the National First-class Discipline Program of Light Industry Technology and Engineering (LITE 2018-08).

In addition, we thank Professor Shengying Li from Shandong University for providing the ferredoxin reductase Fdr_0978 and ferredoxin Fdx_1499 from Synechococcus elongates PCC7942.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1138376/full#supplementary-material

Adhikari, B., Marasini, B. P., Rayamajhee, B., Bhattarai, B. R., Lamichhane, G., Khadayat, K., et al. (2021). Potential roles of medicinal plants for the treatment of viral diseases focusing on COVID-19: A review. Phytother. Res. 35 (3), 1298–1312. doi:10.1002/ptr.6893

Ba, L., Li, P., Zhang, H., Duan, Y., and Lin, Z. (2013a). Engineering of a hybrid biotransformation system for cytochrome P450sca-2 in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. J. 8 (7), 785–793. doi:10.1002/biot.201200097

Ba, L., Li, P., Zhang, H., Duan, Y., and Lin, Z. (2013b). Semi-rational engineering of cytochrome P450sca-2 in a hybrid system for enhanced catalytic activity: Insights into the important role of electron transfer. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110 (11), 2815–2825. doi:10.1002/bit.24960

Bakkes, P. J., Biemann, S., Bokel, A., Eickholt, M., Girhard, M., and Urlacher, V. B. (2015). Design and improvement of artificial redox modules by molecular fusion of flavodoxin and flavodoxin reductase from Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 5, 12158. doi:10.1038/srep12158

Bakkes, P. J., Riehm, J. L., Sagadin, T., Ruhlmann, A., Schubert, P., Biemann, S., et al. (2017). Engineering of versatile redox partner fusions that support monooxygenase activity of functionally diverse cytochrome P450s. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 9570. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10075-w

Berdy, J. (2005). Bioactive microbial metabolites - a personal view. J. Antibiot. 58 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1038/ja.2005.1

Choi, K. Y., Jung, E., Jung, D. H., An, B. R., Pandey, B. P., Yun, H., et al. (2012). Engineering of daidzein 3'-hydroxylase P450 enzyme into catalytically self-sufficient cytochrome P450. Microb. Cell. Fact. 11, 81. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-11-81

Chu, L. L., Pandey, R. P., Jung, N., Jung, H. J., Kim, E. H., and Sohng, J. K. (2016). Hydroxylation of diverse flavonoids by CYP450 BM3 variants: Biosynthesis of eriodictyol from naringenin in whole cells and its biological activities. Microb. Cell. Fact. 15 (1), 135. doi:10.1186/s12934-016-0533-4

Cushnie, T. P. T., and Lamb, A. J. (2005). Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 26 (5), 343–356. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002

de Carvalho, C. C. (2017). Whole cell biocatalysts: Essential workers from nature to the industry. Microb. Biotechnol. 10 (2), 250–263. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.12363

Dueber, J. E., Wu, G. C., Malmirchegini, G. R., Moon, T. S., Petzold, C. J., Ullal, A. V., et al. (2009). Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat. Biotechnol. 27 (8), 753–759. doi:10.1038/nbt.1557

Gao, S., Xu, X., Zeng, W., Xu, S., Lyv, Y., Feng, Y., et al. (2020). Efficient biosynthesis of (2S)-eriodictyol from (2S)-naringenin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through a combination of promoter adjustment and directed evolution. ACS Synth. Biol. 9 (12), 3288–3297. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00346

Gibson, D. G., Young, L., Chuang, R. Y., Venter, J. C., Hutchison, C. A., and Smith, H. O. (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6 (5), 343–345. doi:10.1038/Nmeth.1318

Girhard, M., Klaus, T., Khatri, Y., Bernhardt, R., and Urlacher, V. B. (2010). Characterization of the versatile monooxygenase CYP109B1 from Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87 (2), 595–607. doi:10.1007/s00253-010-2472-z

Havsteen, B. H. (2002). The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 96 (2-3), 67–202. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00298-X

Hayashi, K., Sugimoto, H., Shinkyo, R., Yamada, M., Ikeda, S., Ikushiro, S., et al. (2008). Structure-based design of a highly active vitamin D hydroxylase from Streptomyces griseolus CYP105A1. Biochemistry 47 (46), 11964–11972. doi:10.1021/bi801222d

Horton, R. M., Ho, S. N., Pullen, J. K., Hunt, H. D., Cai, Z. L., and Pease, L. R. (1993). Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 217, 270–279. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f

Hu, B. D., Yu, H. B., Zhou, J. W., Li, J. H., Chen, J., Du, G. C., et al. (2022a). Whole-cell P450 biocatalysis using engineered Escherichia coli with fine-tuned heme biosynthesis. Adv. Sci. 2022, e2205580. doi:10.1002/advs.202205580

Hu, B. D., Zhao, X. R., Wang, E. D., Zhou, J. W., Li, J. H., Chen, J., et al. (2022b). Efficient heterologous expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in microorganisms for the biosynthesis of natural products. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 1–15. doi:10.1080/07388551.2022.2029344

Kabumoto, H., Miyazaki, K., and Arisawa, A. (2009). Directed evolution of the actinomycete cytochrome P450 moxA (CYP105) for enhanced activity. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 73 (9), 1922–1927. doi:10.1271/bbb.90013

Ladkau, N., Schmid, A., and Buhler, B. (2014). The microbial cell-functional unit for energy dependent multistep biocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 30, 178–189. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.06.003

Lamb, D. C., Waterman, M. R., and Zhao, B. (2013). Streptomyces cytochromes P450: Applications in drug metabolism. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 9 (10), 1279–1294. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.806485

Lee, D. E., Lee, K. W., Byun, S., Jung, S. K., Song, N., Lim, S. H., et al. (2011). 7,3',4'-Trihydroxyisoflavone, a metabolite of the soy isoflavone daidzein, suppresses ultraviolet B-induced skin cancer by targeting Cot and MKK4. J. Biol. Chem. 286 (16), 14246–14256. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.147348

Lee, S. Y., and Kim, H. U. (2015). Systems strategies for developing industrial microbial strains. Nat. Biotechnol. 33 (10), 1061–1072. doi:10.1038/nbt.3365

Lin, B., and Tao, Y. (2017). Whole-cell biocatalysts by design. Microb. Cell. Fact. 16 (1), 106. doi:10.1186/s12934-017-0724-7

Lin, Y. H., and Yan, Y. J. (2014). Biotechnological production of plant-specific hydroxylated phenylpropanoids. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 111 (9), 1895–1899. doi:10.1002/bit.25237

Liu, J., Tian, M., Wang, Z., Xiao, F., Huang, X., and Shan, Y. (2022a). Production of hesperetin from naringenin in an engineered Escherichia coli consortium. J. Biotechnol. 347, 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2022.02.008

Liu, L., Yao, Q., Ma, Z., Ikeda, H., Fushinobu, S., and Xu, L. H. (2016). Hydroxylation of flavanones by cytochrome P450 105D7 from Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 132, 91–97. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2016.07.001

Liu, X., Li, F., Sun, T., Guo, J., Zhang, X., Zheng, X., et al. (2022b). Three pairs of surrogate redox partners comparison for Class I cytochrome P450 enzyme activity reconstitution. Commun. Biol. 5 (1), 791. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03764-4

Ma, B. B., Wang, Q. W., Han, B. N., Ikeda, H., Zhang, C. F., and Xu, L. H. (2021). Hydroxylation, epoxidation, and dehydrogenation of capsaicin by a microbial promiscuous cytochrome P450 105D7. Chem. Biodivers. 18 (4), e2000910. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202000910

Ma, B., Wang, Q., Ikeda, H., Zhang, C., and Xu, L. H. (2019). Hydroxylation of steroids by a microbial substrate-promiscuous P450 cytochrome (CYP105D7): Key arginine residues for rational design. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85 (23), e01530–e01519. doi:10.1128/AEM.01530-19

Middleton, E., Kandaswami, C., and Theoharides, T. C. (2000). The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 52 (4), 673–751.

Moody, S. C., and Loveridge, E. J. (2014). CYP105-diverse structures, functions and roles in an intriguing family of enzymes in Streptomyces. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117 (6), 1549–1563. doi:10.1111/jam.12662

Niraula, N. P., Bhattarai, S., Lee, N. R., Sohng, J. K., and Oh, T. J. (2012). Biotransformation of flavone by CYP105P2 from Streptomyces peucetius. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22 (8), 1059–1065. doi:10.4014/jmb.1201.01037

Pan, M. H., Lai, C. S., and Ho, C. T. (2010). Anti-inflammatory activity of natural dietary flavonoids. Food Funct. 1 (1), 15–31. doi:10.1039/c0fo00103a

Pandey, B. P., Lee, N., Choi, K. Y., Jung, E., Jeong, D. H., and Kim, B. G. (2011). Screening of bacterial cytochrome P450s responsible for regiospecific hydroxylation of (iso)flavonoids. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 48 (4-5), 386–392. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.01.001

Pandey, B. P., Roh, C., Choi, K. Y., Lee, N., Kim, E. J., Ko, S., et al. (2010). Regioselective hydroxylation of daidzein using P450 (CYP105D7) from Streptomyces avermitilis MA4680. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 105 (4), 697–704. doi:10.1002/bit.22582

Park, H. A., and Choi, K. Y. (2020). Alpha, omega-oxyfunctionalization of C12 alkanes via whole-cell biocatalysis of CYP153A from Marinobacter aquaeolei and a new CYP from Nocardia farcinica IFM10152. Biochem. Eng. J. 156, 107524. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2020.107524

Park, H., Park, G., Jeon, W., Ahn, J. O., Yang, Y. H., and Choi, K. Y. (2020). Whole-cell biocatalysis using cytochrome P450 monooxygenases for biotransformation of sustainable bioresources (fatty acids, fatty alkanes, and aromatic amino acids). Biotechnol. Adv. 40, 107504. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107504

Park, S. Y., Eun, H., Lee, M. H., and Lee, S. Y. (2022a). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli with electron channelling for the production of natural products. Nat. Catal. 5 (8), 726–737. doi:10.1038/s41929-022-00820-4

Park, S. Y., Yang, D., Ha, S. H., and Lee, S. Y. (2022b). Production of phenylpropanoids and flavonolignans from glycerol by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 119 (3), 946–962. doi:10.1002/bit.28008

Porebski, B. T., and Buckle, A. M. (2016). Consensus protein design. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 29 (7), 245–251. doi:10.1093/protein/gzw015

Ravishankar, D., Rajora, A. K., Greco, F., and Osborn, H. M. I. (2013). Flavonoids as prospective compounds for anti-cancer therapy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 45 (12), 2821–2831. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.10.004

Sawada, N., Sakaki, T., Yoneda, S., Kusudo, T., Shinkyo, R., Ohta, M., et al. (2004). Conversion of vitamin D3 to 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by Streptomyces griseolus cytochrome P450SU-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320 (1), 156–164. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.140

Subedi, P., Park, J. K., and Oh, T. J. (2022). Engineering of microbial substrate promiscuous CYP105A5 for improving the flavonoid hydroxylation. Catalysts 12 (10), 1157. doi:10.3390/catal12101157

Sugimoto, H., Shinkyo, R., Hayashi, K., Yoneda, S., Yamada, M., Kamakura, M., et al. (2008). Crystal structure of CYP105A1 (P450SU-1) in complex with 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3,. Biochemistry 47 (13), 4017–4027. doi:10.1021/bi7023767

Sun, Y., Ma, L., Han, D., Du, L., Qi, F., Zhang, W., et al. (2017). In vitro reconstitution of the cyclosporine specific P450 hydroxylases using heterologous redox partner proteins. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44 (2), 161–166. doi:10.1007/s10295-016-1875-y

Takamatsu, S., Xu, L. H., Fushinobu, S., Shoun, H., Komatsu, M., Cane, D. E., et al. (2011). Pentalenic acid is a shunt metabolite in the biosynthesis of the pentalenolactone family of metabolites: Hydroxylation of 1-deoxypentalenic acid mediated by CYP105D7 (SAV_7469) of Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Antibiot. 64 (1), 65–71. doi:10.1038/ja.2010.135

Urlacher, V. B., and Girhard, M. (2019). Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in biotechnology and synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 37 (8), 882–897. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.01.001

Verkamp, E., Backman, V. M., Bjornsson, J. M., Soll, D., and Eggertsson, G. (1993). The periplasmic dipeptide permease system transports 5-aminolevulinic acid in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175 (5), 1452–1456. doi:10.1128/jb.175.5.1452-1456.1993

Wang, Y., Heermann, R., and Jung, K. (2017). CipA and CipB as scaffolds to organize proteins into crystalline inclusions. ACS Synth. Biol. 6 (5), 826–836. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00323

Watanabe, I., Nara, F., and Serizawa, N. (1995). Cloning, characterization and expression of the gene encoding cytochrome P450sca-2 from Streptomyces carbophilus involved in production of pravastatin, a specific HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. Gene 163 (1), 81–85. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(95)00394-L

Xu, L. H., Ikeda, H., Liu, L., Arakawa, T., Wakagi, T., Shoun, H., et al. (2015). Structural basis for the 4'-hydroxylation of diclofenac by a microbial cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 (7), 3081–3091. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-6148-y

Xu, X., Tian, L., Tang, S., Xie, C., Xu, J., and Jiang, L. (2020). Design and tailoring of an artificial DNA scaffolding system for efficient lycopene synthesis using zinc-finger-guided assembly. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47 (2), 209–222. doi:10.1007/s10295-019-02255-6

Yao, Q., Ma, L., Liu, L., Ikeda, H., Fushinobu, S., Li, S., et al. (2017). Hydroxylation of compactin (ML-236B) by CYP105D7 (SAV_7469) from Streptomyces avermitilis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27 (5), 956–964. doi:10.4014/jmb.1610.10079

Yao, X., Kang, T., Pu, Z., Zhang, T., Lin, J., Yang, L., et al. (2022). Sequence and structure-guided engineering of urethanase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens d3 for improved catalytic activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70 (23), 7267–7278. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.2c01406

Yasuda, K., Sugimoto, H., Hayashi, K., Takita, T., Yasukawa, K., Ohta, M., et al. (2018). Protein engineering of CYP105s for their industrial uses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 1866 (1), 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.05.014

Yasuda, K., Yogo, Y., Sugimoto, H., Mano, H., Takita, T., Ohta, M., et al. (2017). Production of an active form of vitamin D2 by genetically engineered CYP105A1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 486 (2), 336–341. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.040

Zhang, W., Du, L., Li, F. W., Zhang, X. W., Qu, Z. P., Hang, L., et al. (2018). Mechanistic insights into interactions between bacterial Class I P450 enzymes and redox partners. ACS Catal. 8 (11), 9992–10003. doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b02913

Keywords: cytochrome P450 enzyme, Escherichia coli, whole-cell biocatalyst, SCA-2, hydroxylation, flavonoids

Citation: Hu B, Zhao X, Zhou J, Li J, Chen J and Du G (2023) Efficient hydroxylation of flavonoids by using whole-cell P450 sca-2 biocatalyst in Escherichia coli. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11:1138376. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1138376

Received: 05 January 2023; Accepted: 03 February 2023;

Published: 15 February 2023.

Edited by:

Genlin Zhang, Shihezi University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Hu, Zhao, Zhou, Li, Chen and Du. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinrui Zhao, emhhb3hpbnJ1aUBqaWFuZ25hbi5lZHUuY24=; Guocheng Du, Z2NkdUBqaWFuZ25hbi5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.