94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. , 13 May 2022

Sec. Nanobiotechnology

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.902312

This article is part of the Research Topic Smart Nanomaterials for Biosensing and Therapy Applications View all 21 articles

Lihua Li1†

Lihua Li1† Jifan Zhang2†

Jifan Zhang2† Yang Lin1

Yang Lin1 Yongfeng Zhang3

Yongfeng Zhang3 Shujie Li1

Shujie Li1 Yanzhen Liu1

Yanzhen Liu1 Yingxu Zhang1

Yingxu Zhang1 Leilei Shi2*

Leilei Shi2* Shouzhang Yuan1*

Shouzhang Yuan1* Lihao Guo3*

Lihao Guo3*Using photothermal therapy to treat cancer has become an effective method, and the design of photothermal agents determines their performance. However, due to the major radiative recombination of a photogenerated electron in photothermal materials, the photothermal performance is weak which hinders their applications. In order to solve this issue, preventing radiative recombination and accelerating nonradiative recombination, which can generate heat, has been proved as a reasonable way. We demonstrated a Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite with an obviously enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency (η = 87.98%), and this improvement can be attributed to the electron migration. Then, a mechanism is proposed based on the electron transfer regulatory effect and the localized surface plasmon resonance effect, which synergistically promote nonradiative recombination and generate more heat. Overall, our design strategy shows a way to improve the photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4, and this method can be extended to other photothermal agents to let them be more efficient in treating cancer.

In the 21st century, the cancer problem has become more dominant and malignant, which is one of the most threatening public health questions and causes over 9.6 million deaths annually in the world (Massagué and Obenauf, 2016; Steeg, 2016). However, there is still a method that can rapidly and completely treat cancer because of metastasis; meanwhile, the traditional treatments, for e.g., radiotherapy and chemotherapy, may induce severe side effects which are traumatic for patients (Yilmaz et al., 2007). In recent decades, the optical treatment has been considered an efficient and less traumatic approach to treat primary and metastatic tumors, and the photothermal therapy (PTT) has been synergistically used with traditional methods and has shown a satisfied treatment effect (Chang et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2020). In brief, under optical irradiation, photothermal reagents can generate localized hyperthermia and treat cancer. However, most of the existing photothermal materials lack photothermal performance due to the minority nonradiative recombination of the photogenerated electron. The low photothermal conversion determines that more materials or higher laser power will be used to achieve the heat temperature, which can easily cause damage to patients (Zhou et al., 2018; Xi et al., 2020). So, the suitable photothermal materials with high photothermal performance are urgently needed.

Ternary chalcogenide, Cu2MoS4, is a representative material that has been exploited in photothermal therapy (Chen et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2019). However, the photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4 is weak which is common for simplex phototherapy reagents and can be explained by the band theory that the photothermal effect of Cu2MoS4 is mainly induced by the nonradiative recombination (producing phonon) of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, but this recombination is low compared with the radiative recombination (Zhang et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2021). Hence, it is highly desirable to improve the photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4 to make it a suitable photothermal reagent that achieves better anticancer outcomes.

In order to accelerate the probability of nonradiative recombination in the electron transfer process and prevent radiative recombination, which can efficiently enhance the photothermal effect of Cu2MoS4, constructing a heterostructure of noble metal or graphene and Cu2MoS4 has been proved as a reasonable method (Zhang et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2020). The high conductivity can lead the electron to migrate from Cu2MoS4 to noble metal or graphene when they come into contact with Cu2MoS4, and then the radiative recombination can be prevented while the probability of nonradiative recombination increases, thus enhancing photothermal performance (Rameshbabu et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the composite process of Cu2MoS4 and noble metal (usually nanoparticles) or graphene is difficult, and the interface resistance of metal nanoparticles may hinder the transfer of electrons, weakening the migration. Hence, MXene, a new member of 2D materials considered 2D transition metal carbides or nitrides with metallic conductivity, has become a substitute for noble metal and graphene, and the abundant surface termination groups on MXene’s surface provide a large number of sites for Cu2MoS4 to anchor on (Guo et al., 2021; Mohammadi et al., 2021; Qiu et al., 2021). Meanwhile, owing to the high work function, superior electron conductivity, and lower interface resistance (compared with noble metal nanoparticles) of MXene, the caused electron transfer regulatory effect can enhance the photothermal performance of composites, which is similar to the aforementioned noble metal (Mariano et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). More interestingly, under visible light radiation at 800 nm (1.5 eV), the MXene can produce the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect which is a novel method to assist the separation of electrons and further stimulate the generation of heat (Mariano et al., 2016; Demellawi et al., 2018; Lioi et al., 2019).

We introduced Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets to improve the photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4, and a Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite was synthesized (Scheme 1). The results of the photothermal conversion experience confirmed our hypothesis, and the best performance of the nanocomposite obtained can increase the temperature by more than 55 °C under NIR radiation (1.0 W/cm−2 at 808 nm) with an obviously enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency (87.98%) compared with pure Cu2MoS4 (72.07%). Using the absorption spectrum and photoluminescence (PL) spectrum, the electron transfer process can be verified, and the obvious quenching phenomenon, i.e., weakened radiative recombination, reflects the rapid separation and transfer of photogenerated electrons. Based on the experimental results and band theory, we proposed a mechanism of enhanced photothermal performance that is mainly caused by promoted separation and transfer of electron and nonradiative recombination, owing to the electron transfer regulatory effect and LSPR effect. Therefore, these results suggest that the Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite with enhanced photothermal performance could be used to treat cancers.

Using a minimally intensive layer delamination (MILD) method as previously reported (Halim et al., 2014), the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets were prepared from commercial Ti3AlC2 MAX purchased from Forsman Scientific Co. In detail, first, the etching agent was prepared by gently adding 1.5 g LiF into 20 ml of 9 M HCl with continuous stirring. After LiF was totally dissolved, 1 g Ti3AlC2 MAX powder was slowly added to the etching agent, and the mixture was continuously stirred at 35°C for 30 h. Afterward, the product was washed several times with deionized water (DI water), and when the pH of the supernatant reached 6, the supernatant was ultrasonicated for 1.5 h with N2 atmosphere protection in an ice bath. Then, the Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets were obtained after centrifugation (3,500 rpm for 1 h).

The Cu2O precursor was synthesized by reducing copper hydroxide. NaOH (30 ml 3.75 M) solution was added dropwise in CuSO4 (30 ml 0.5 M) solution with continuous stirring to prepare Cu(OH)2 colloid; meanwhile, glucose (C6H12O6, 30 ml 0.75 M) solution was prepared and kept at 60°C. Then, the Cu(OH)2 colloid was heated to 60°C and added into glucose solution drop by drop at 60°C by placing in a water bath. Then, the mixture color gradually turned brick-red which indicates the successful preparation of Cu2O. After allowing the colloid to react at 60°C for 30 min, the precursor was obtained through filtrating colloid and vacuum drying.

To synthesize Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites, 0.02 g MXene was first dissolved in 30 ml DI water, and (0 g, 0.14 g, 0.42 g, 0.70 g, 0.98 g, and 1.3 g) thioacetamide (TAA) was added into MXene colloidal solution. Meanwhile, (0 g, 0.17 g, 0.51 g, 0.85 g, 1.2 g, and 1.6 g) MoO3 and (0 g, 0.12 g, 0.36 g, 0.60 g, 0.84 g, and 1.1 g) Cu2O were ultrasonically dispersed into 5 ml DI water, respectively. Then, three dispersion solutions were transferred into a 100-ml tailor-made Teflon reactor, and using a microwave, the reaction temperature could be rapidly elevated to 150°C within 3 min. Afterward, the reaction temperature was maintained at 150°C for 2 h, and the Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite (marked Cu2MoS4, Cu2MoS4@MXene-1, Cu2MoS4@MXene-3, Cu2MoS4@MXene-5, Cu2MoS4@MXene-7, and Cu2MoS4@MXene-9 for different ratios) products were obtained after washing and drying.

In the following photothermal performance experiment, a series of concentration (0, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 1,000 μg/ml) solutions (1 ml) of six samples were prepared in an Eppendorf tube, respectively, and a NIR laser (1.0 W/cm2) at 808 nm was used to irradiate the samples (Zhang et al., 2021). Then, during 600 s of irradiation, the temperature change of samples was monitored using an infrared thermal imaging camera and recorded on a computer connected to the camera in real-time. The photostability was tested (500 μg/ml) by repeating the heating (laser on for 600 s)/cooling (laser off for 600 s) processes three times (power density is 1.0 W/cm2). Furthermore, the laser was modulated for 0.5 W/cm2, 1.0 W/cm2, and 1.5 W/cm2 to evaluate the influence of power density.

Based on the results of the photothermal experiment, the photothermal conversion efficiency can be calculated according to Equation 1:

where η is the photothermal conversion efficiency, h (Wcm−2 K−1) is the heat transfer coefficient, S (cm2) is the surface area of quartz cuvette, Tmax (K) is the highest equilibrium temperature, T0 (K) is the surrounding temperature, Qdis (W) is the heat loss which is approximate to 0, W is the power density of the laser, and A808 is the absorbance of samples at 808 nm. Moreover, the Tmax, T0, and A808 can be measured, while the hS is calculated through Equation 2:

where mW and CW represent the total mass and the specific heat capacity of solvent and water, respectively, and τs is the time constant which can be obtained through Equation 3:

Using the recording temperature T, the τs can be calculated, and then the photothermal conversion efficiency is calculated (Chen et al., 2019).

The morphologies and compositions of precursors and composites were characterized using the transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL-2100F), the X-ray diffraction spectrometer (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance), Raman and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy (Renishaw inVia), and UV-vis-NIR spectra (JASCO V-570). Infrared thermal imaging was monitored using an IR thermal camera (TELEDYNE FLIR Exx) and recorded using a computed connected to the camera.

As illustrated in Scheme 1, we have prepared Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites through the in situ hydrothermal method (see details in Experimental Section). In brief, the prepared MXene nanosheets were first mixed with thioacetamide (TAA) in water; meanwhile, the MoO3 and Cu2O were ultrasonically dispersed in water. Then, the reaction fluid prepared by mixing three dispersions was poured into a microwave hydrothermal reactor and allowed to react using a microwave. After washing with DI water, the Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites can be obtained. More importantly, this process allows Cu2MoS4 nanoplates to uniformly grow on MXene nanosheets which cannot be reached by the physical mixing method. Furthermore, due to the high quality of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites and the unique effect caused by composite processes, such as band engineering and high electron conductivity of MXene, a more excellent photothermal conversion performance can be achieved than than that of pure Cu2MoS4 nanoplates.

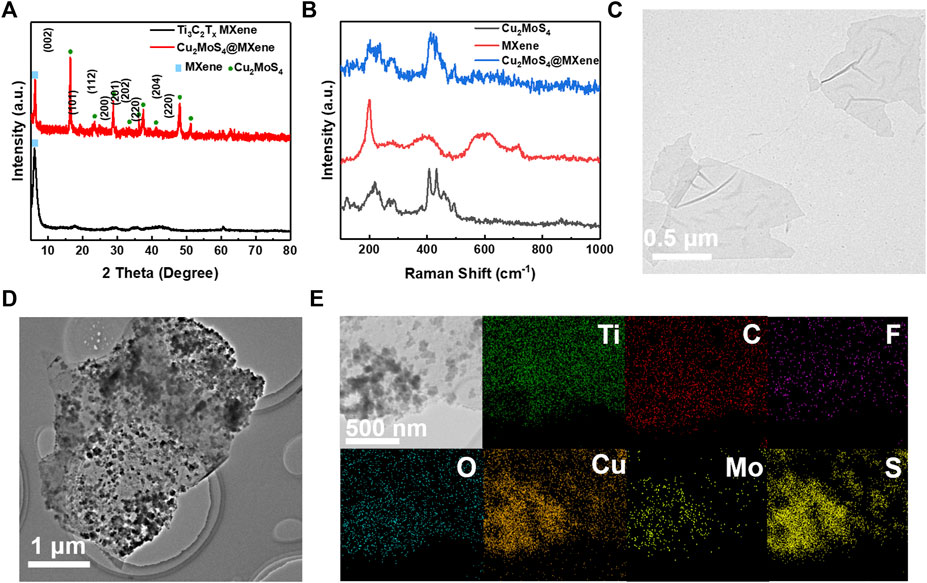

As for the basics of nanocomposites, the MXene nanosheets were first prepared using the MILD method (Halim et al., 2014). The Ti3AlC2 (MAX) precursor was etched with LiF and HCl. During the etching process, the Al layer in the MAX phase was selectively etched and Ti3C2Tx nanosheets remained. As shown in the XRD pattern (Figure 1A), both the diffraction peaks at 39°, which can be indexed to the (104) plane of Ti3AlC2 MAX, disappear, and the (002) peak left shifts to 6.5°, indicating successful preparation of Ti3C2Tx nanosheets (Lipatov et al., 2016). According to the pattern of the Raman spectrum (Figure 1B), the vibration modes of MXene nanosheets can be divided into two types: out-of-plane mode (A1g) and in-plane mode (Eg), and the vibration peak at 198 cm−1, 715 cm−1 and 253 cm−1, and 502 cm−1 can be well assigned to these two modes, respectively (Hu et al., 2015). Using TEM, the monolayer Ti3C2Tx nanosheets can be seen with a size of approximately 1 μm, as shown in Figure 1C. The results of these characterization methods show that the high-quality MXene nanosheets have been successfully produced and can be used in the next composite process.

FIGURE 1. Characterization of precursor and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites. (A) XRD pattern of Ti3C2Tx MXene and Cu2MoS4@MXene. (B) Raman spectra of Cu2MoS4, MXene, and Cu2MoS4@MXene. TEM images of (C) MXene nanosheets and (D) Cu2MoS4@MXene. (E) EDS mapping of Ti, C, F, O, Cu, Mo, and S of Cu2MoS4@MXene.

Because of many hydrophilic terminations planted on the surface of MXene nanosheets during the liquid etching process, the MXene can be well dispersed in water, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1, which ensures the stability of MXene solution in the hydrothermal process. After the hydrothermal process, the morphology of MXene nanosheets has undergone an obvious change (Figure 1D), and there are many nanoplates anchored on the surface of unimpaired MXene nanosheets. In Figure 1E, the distribution of elements reflected by EDS shows that the MXene is still intact, and the Cu2MoS4 nanoplates are only synthesized on the surface of MXene nanosheets which meets our expectations. Interestingly, it can be seen that the size of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites appears bigger than that of pure MXene nanosheets, and this phenomenon may be a combination of several nanosheets, which is caused by some anchored Cu2MoS4 that can connect adjacent MXene nanosheets. In order to further confirm the successful synthesis of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites, the XRD and Raman spectra were used. In Figure 1A, the XRD result of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites illustrates that the Cu2MoS4 on the MXene nanosheets has good crystallinity, and the major peaks at 6.1°, 16.3°, 28.8°,37.4°, and 47.9° are well indexed to the MXene and tetragonal-phase of Cu2MoS4 (P

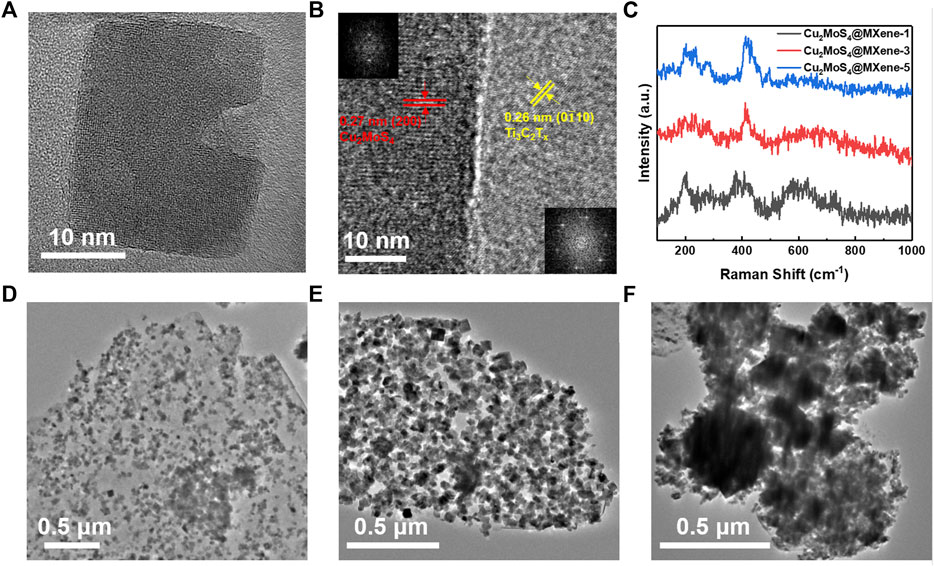

FIGURE 2. Characterization of different Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites. (A,B) HRTEM of Cu2MoS4@MXene (inset in B is the FFT of Cu2MoS4 and MXene, respectively). (C) Raman spectra of Cu2MoS4@MXene-1, Cu2MoS4@MXene-3, and Cu2MoS4@MXene-5. (D–F) TEM images of Cu2MoS4@MXene-1, Cu2MoS4@MXene-5, and Cu2MoS4@MXene-9, respectively.

Considering the ratio of Cu2MoS4 and MXene in Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites may affect their performance, we prepared a series of nanocomposite samples with a gradient ratio. There is a regular variation in the Raman spectrum (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure S2), and with the increased ratio of Cu2MoS4, the vibration peak of MXene becomes decrescent and that of Cu2MoS4 becomes stronger. Moreover, the microscopic morphology of Cu2MoS4@MXene-1, Cu2MoS4@MXene-5, and Cu2MoS4@MXene-9 prove the result of the Raman spectrum, which shows that the observed coverage ratio of anchored Cu2MoS4 nanoplates on MXene nanosheets increases, but when the ratio of Cu2MoS4 is too high (Cu2MoS4@MXene-9), the excessive aggregation occurs which is unfavorable in application (Fang et al., 2020). In addition, when the ratio of Cu2MoS4 becomes high, there are more evident signals of Cu and Mo elements in EDS mapping (Supplementary Figure S3) compared with the low ratio sample. Also, an evident aggregation of Cu2MoS4 can be seen, which further verified the aforementioned point. However, even if the ratio is excessively increased, there are still no Cu2MoS4 nanoplates lying outside the MXene nanosheets because of the anchoring effect mentioned earlier, which ensures the contact of Cu2MoS4 with high conductivity MXene and the electron transfer regulatory effect.

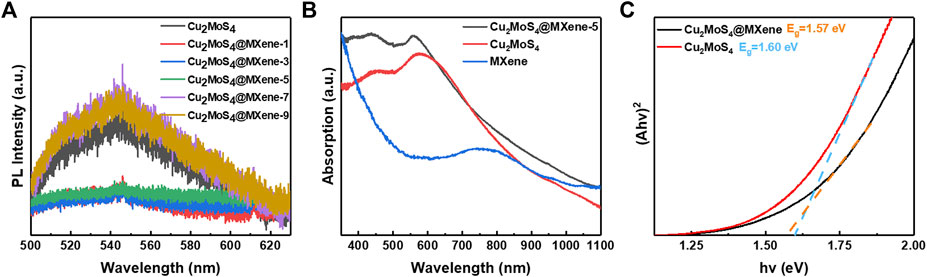

As introduced earlier, the MXene can affect the photothermal performance of nanocomposites through band engineering and regulatory effect, so to make clear the role of MXene in this process and whether the nanocomposite will gather an improved performance, the following optical properties of nanocomposites are enumerated: the result of the PL spectrum suggests that the nanocomposites’ PL intensity is different from pure Cu2MoS4, and the samples marked as Cu2MoS4@MXene-1, Cu2MoS4@MXene-3, and Cu2MoS4@MXene-5 have a lower intensity. According to the band theory, the PL intensity is associated with the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, and the more radiative recombination occurs, and the higher PL intensity will be received (Feng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Thus, it is obvious that the radiative recombination rate of samples with lower PL intensity is slower than that of pure Cu2MoS4 because the MXene with high electron conductivity can separate and transfer electrons from photogenerated exciton which prevents the radiative recombination and increases the concentration of carriers. Moreover, the separated carriers can efficiently facilitate crystal lattice vibrations after interacting with hot carriers produced by MXene because of the NIR-induced LSPR effect, thus leading to elevated temperatures (Zhou et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). However, when the ratio of Cu2MoS4 is excessive, the PL intensity becomes stronger and more radiative recombination occurs, which could be caused by aggregation issues and may weaken the photothermal performance.

Figure 3B is the UV-vis-NIR absorption spectrum of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites, and the pattern illustrates that the nanocomposites exhibit a stronger absorption than the pure Cu2MoS4 in a nearly full band spectrum, which is another cause of high photothermal performance. As shown in Figure 3B, the absorption spectra of pure MXene shows a weak absorption intensity in visible and near-infrared region compared with Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite. Furthermore, according to Tauc’s formulation (Wood and Tauc, 1972; Tauc, 1974), the optical band gaps can be calculated as around 1.60 and 1.57 eV for pure Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites, respectively (Figure 3C). The narrowing band gap can be explained by the band theory that when the high work function MXene nanosheets come in contact with Cu2MoS4, the electrons will be drawn from a higher Fermi level of Cu2MoS4 to MXene, and when this process achieves a balance, the Fermi level of Cu2MoS4 will be brought down. So the band gap of nanocomposites is narrower than that of pure Cu2MoS4. In addition, this band gap engineering can promote the separation of photogenerated exciton and improve the photothermal performance, thus conforming to the result of the PL spectrum mentioned previously.

FIGURE 3. Optical properties of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites. (A) PL spectra (excited by a 325-nm laser from 500 to 630 nm) of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites. (B) UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of Cu2MoS4, Cu2MoS4@MXene, and MXene. (C) Tauc plots of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene.

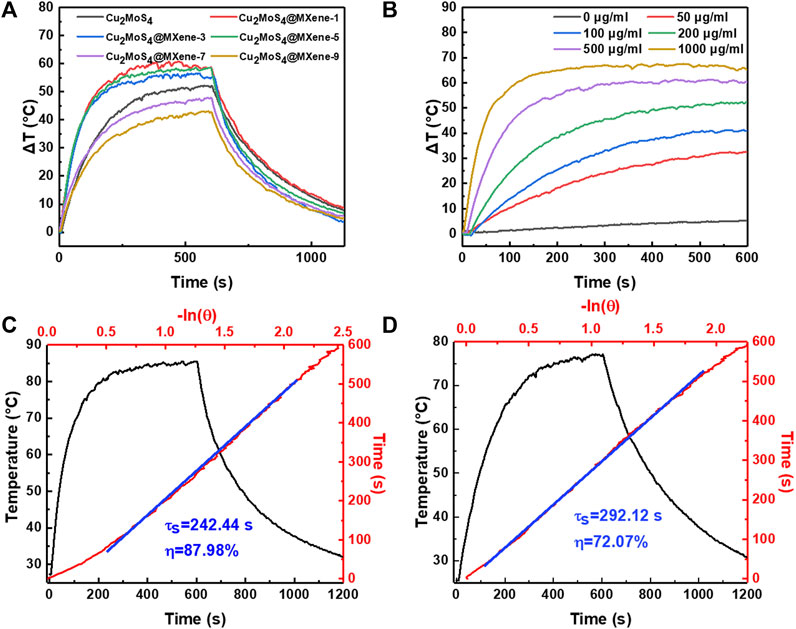

On account of the previously mentioned results, we forecast that the high-quality Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites possess better photothermal performance than pure Cu2MoS4 due to the novel effects caused by the composite process, e.g., band engineering, electron transfer regulatory effect, and anchored effect. Thus, the NIR thermal conversion performance of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites was tested to verify this forecast. As shown in Figure 4A, under NIR light (1.0 W/cm2 at 808 nm) for 10 min, the temperature of each sample (500 μg/ml) has an obvious increase, and the highest ΔT can reach more than 55°C with two samples, i.e., Cu2MoS4@MXene-1 and Cu2MoS4@MXene-5, which is higher than pure Cu2MoS4 (50°C). However, the photothermal performance of samples marked as Cu2MoS4@MXene-7 and Cu2MoS4@MXene-9 is worse, which may be caused by the aggregation issue mentioned earlier. In addition, the temperature change is also dependent on concentration and laser power density which further demonstrates the distinguished photothermal conversion property of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S4) (Hao et al., 2021). Taking into account the photostability of Cu2MoS4@MXene-1 and Cu2MoS4@MXene-5 (Supplementary Figure S5), Cu2MoS4@MXene-5 has the best performance, which matches the microscopic morphology and optical properties. When compared with the corresponding NIR thermal time constants (τs) and conversion efficiency (η) of pure Cu2MoS4 (292.12 s and 72.07%), the better τs and η of Cu2MoS4@MXene-5 are calculated as 242.44 s and 87.98%, respectively (Figure 4C and Figure 4D) (Chang et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Therefore, based on all of these experimental data, it is evident that the composite process efficiently promoted the photothermal conversion ability.

FIGURE 4. Photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene. (A) Photothermal activity of Cu2MoS4 and Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites. (B) Concentration-dependent temperature change curves of Cu2MoS4@MXene-5. (C,D) Heating–cooling curves and linear time constant curves of Cu2MoS4@MXene and Cu2MoS4.

To reveal the reasons for the enhanced performance of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites, their photothermal mechanism is proposed based on the previously analyzed experimental data. As reported in other previous work, under NIR irradiation, the electron in the photogenerated exciton will transit to the conduction band; then, the major electron in the excited state will recombine with the hole through radiating fluorescence; meanwhile, only a minority of electron–hole pairs have a photothermal effect due to nonradiative recombination, which can be described as the photothermal mechanism (Li et al., 2021). However, when the high work function (5.28 ± 0.03 eV) MXene is introduced, the heterojunction formed between Cu2MoS4 and MXene should be regarded as the transfer barrier (Regulacio et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Prabaswara et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Referring to the band theory, the excited electron will irreversibly migrate from the Cu2MoS4 to MXene until their Fermi level reaches equilibrium; then, this migration can be accelerated because of the high-electron conductivity of MXene, and this process is defined as the band engineering caused by electron transfer regulatory effect. Obviously, the major excited electron of Cu2MoS4 in Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposites will migrate to MXene instead of radiatively recombining with the hole, so the probability of nonradiative recombination can multiply which improves the photothermal performance (Li et al., 2021).

Meanwhile, the UV-vis spectrum and Raman spectrum indicate an LSPR effect of MXene at 800 nm (1.5 eV) which can be attributed to an out-of-plane transverse plasmonic resonance, and owing to the LSPR effect, the MXene can generate the hot carriers under vis-NIR irradiation. Then, the injected hot carriers can further assist the separation and transfer of electrons and prevent the radiative recombination which is another crucial reason for improved photothermal performance.

In brief, after the hydrothermal process, Cu2MoS4 was anchored on the surface of MXene nanosheets, and the electron spontaneously migrates across the transfer barrier (electron transfer regulatory effect and band engineering). Then, with the synergy of MXene’s LSPR effect, the nonradiative recombination, i.e., the performance of photothermal conversion, can be efficiently accelerated.

In summary, in order to improve the photothermal performance of Cu2MoS4, the MXene nanosheets were introduced, and the Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite was successfully synthesized. Due to the superior electron conductivity and high work function of MXene, the motion of the electron was changed at the heterostructure of Cu2MoS4 and MXene, and the electron can migrate from Cu2MoS4 to MXene which promotes the nonradiative recombination and generates heat. Also, the experimental results show that the radiative combination was evidently prevented, indicating an accelerated nonradiative combination, and the enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency of Cu2MoS4@MXene nanocomposite can reach 87.98% compared with the pure Cu2MoS4 (η = 72.07%). Then, a mechanism was proposed based on the electron transfer regulatory effect and LSPR effect. Finally, this work provides an efficient method to enhance the photothermal performance of phototherapy reagents and make them play a great role in cancer treatment.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

LL, JZ, LS, and LG designed the project and analyzed the data. YL, YoZ, SL, YZL, and YiZ performed the experiments. LG wrote the manuscript. LS, SY, and LG revised the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22105229).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2022.902312/full#supplementary-material

Agresti, A., Pazniak, A., Pescetelli, S., Di Vito, A., Rossi, D., Pecchia, A., et al. (2019). Titanium-carbide MXenes for Work Function and Interface Engineering in Perovskite Solar Cells. Nat. Mater. 18, 1264. doi:10.1038/s41563-019-0527-9

Chang, M., Wang, M., Wang, M., Shu, M., Ding, B., Li, C., et al. (2019). A Multifunctional Cascade Bioreactor Based on Hollow‐Structured Cu 2 MoS 4 for Synergetic Cancer Chemo‐Dynamic Therapy/Starvation Therapy/Phototherapy/Immunotherapy with Remarkably Enhanced Efficacy. Adv. Mater. 31, 1905271. doi:10.1002/adma.201905271

Chang, M. Y., Hou, Z. Y., Wang, M., Wang, M. F., Dang, P. P., Liu, J. H., et al. (2020). Cu2MoS4/Au Heterostructures with Enhanced Catalase-like Activity and Photoconversion Efficiency for Primary/Metastatic Tumors Eradication by Phototherapy-Induced Immunotherapy. Small 16, 14. doi:10.1002/smll.201907146

Chen, W. C., Wang, X. F., Zhao, B. X., Zhang, R. J., Xie, Z., He, Y., et al. (2019). CuS-MnS2 Nano-Flowers for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Guided Photothermal/photodynamic Therapy of Ovarian Cancer through Necroptosis. Nanoscale 11, 12983–12989. doi:10.1039/c9nr03114f

Chen, W. X., Chen, H. P., Zhu, H. T., Gao, Q. Q., Luo, J., Wang, Y., et al. (2014). Solvothermal Synthesis of Ternary Cu2MoS4 Nanosheets: Structural Characterization at the Atomic Level. Small 10, 4637–4644. doi:10.1002/smll.201400752

Cheng, Y., Chang, Y., Feng, Y. L., Jian, H., Tang, Z. H., and Zhang, H. Y. (2018). Deep-Level Defect Enhanced Photothermal Performance of Bismuth Sulfide-Gold Heterojunction Nanorods for Photothermal Therapy of Cancer Guided by Computed Tomography Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 246–251. doi:10.1002/anie.201710399

Demellawi, J. K., Lopatin, S., Yin, J., Mohammed, O. F., and Alshareef, H. N. (2018). Tunable Multipolar Surface Plasmons in 2D Ti3C2TX MXene Flakes. ACS Nano 12, 8485–8493. doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b04029

Fang, Y. Z., Hu, R., Zhu, K., Ye, K., Yan, J., Wang, G. L., et al. (2020). Aggregation-Resistant 3D Ti3C2Tx MXene with Enhanced Kinetics for Potassium Ion Hybrid Capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 10. doi:10.1002/adfm.202005663

Feng, H., Dai, Y., Guo, L., Wang, D., Dong, H., Liu, Z., et al. (2021). Exploring Ternary Organic Photovoltaics for the Reduced Nonradiative Recombination and Improved Efficiency Over 17.23% With a Simple Large-Bandgap Small Molecular Third Component. Nano Res. 15, 3222–3229. doi:10.1007/s12274-021-3945-3

Guo, L. H., Li, Z. K., Hu, W. W., Liu, T. P., Zheng, Y. B., Yuan, M. M., et al. (2021). A Flexible Dual-Structured MXene for Ultra-sensitive and Ultra-wide Monitoring of Anatomical and Physiological Movements. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9, 26867–26874. doi:10.1039/d1ta08727d

Halim, J., Lukatskaya, M. R., Cook, K. M., Lu, J., Smith, C. R., Näslund, L.-Å., et al. (2014). Transparent Conductive Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide Epitaxial Thin Films. Chem. Mater. 26, 2374–2381. doi:10.1021/cm500641a

Hao, Y., Mao, L., Zhang, R., Liao, X., Yuan, M., and Liao, W. (2021). Multifunctional Biodegradable Prussian Blue Analogue for Synergetic Photothermal/Photodynamic/Chemodynamic Therapy and Intrinsic Tumor Metastasis Inhibition. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 4, 7081–7093. doi:10.1021/acsabm.1c00694

Hu, T., Wang, J. M., Zhang, H., Li, Z. J., Hu, M. M., and Wang, X. H. (2015). Vibrational Properties of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2T2 (T = O, F, OH) Monosheets by First-Principles Calculations: a Comparative Study. Phy. Chem. Chem. Phy. 17, 9997–10003. doi:10.1039/c4cp05666c

Kim, Y., Tiwari, A. P., Prakash, O., and Lee, H. (2017). Activation of Ternary Transition Metal Chalcogenide Basal Planes through Chemical Strain for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Chempluschem 82, 785–791. doi:10.1002/cplu.201700164

Li, J., Li, Z., Liu, X., Li, C., Zheng, Y., Yeung, K. W. K., et al. (2021). Interfacial Engineering of Bi2S3/Ti3C2Tx MXene Based on Work Function for Rapid Photo-Excited Bacteria-Killing. Nat. Commun. 12, 1224. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21435-6

Lin, Y. X., Chen, S. M., Zhang, K., and Song, L. (2019). Recent Advances of Ternary Layered Cu2MX4 (M = Mo, W; X = S, Se) Nanomaterials for Photocatalysis. Solar, Rrl 3, 13. doi:10.1002/solr.201800320

Lioi, D. B., Neher, G., Heckler, J. E., Back, T., Mehmood, F., Nepal, D., et al. (2019). Electron-Withdrawing Effect of Native Terminal Groups on the Lattice Structure of Ti3C2TX MXenes Studied by Resonance Raman Scattering: Implications for Embedding MXenes in Electronic Composites. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 6087–6091. doi:10.1021/acsanm.9b01194

Lipatov, A., Alhabeb, M., Lukatskaya, M. R., Boson, A., Gogotsi, Y., and Sinitskii, A. (2016). Effect of Synthesis on Quality, Electronic Properties and Environmental Stability of Individual Monolayer Ti3C2 MXene Flakes. Adv. Electro. Mater. 2, 9. doi:10.1002/aelm.201600255

Lv, R., Liang, Y.-Q., Li, Z.-Y., Zhu, S.-L., Cui, Z.-D., and Wu, S.-L. (2021). Flower-like CuS/graphene Oxide with Photothermal and Enhanced Photocatalytic Effect for Rapid Bacteria-Killing Using Visible Light. Rare Met. 41, 639–649. doi:10.1007/s12598-021-01759-4

Mariano, M., Mashtalir, O., Antonio, F. Q., Ryu, W. H., Deng, B. C., Xia, F. N., et al. (2016). Solution-processed Titanium Carbide MXene Films Examined as Highly Transparent Conductors. Nanoscale 8, 16371–16378. doi:10.1039/c6nr03682a

Massagué, J., and Obenauf, A. C. (2016). Metastatic Colonization by Circulating Tumour Cells. Nature 529, 298–306. doi:10.1038/nature17038

Mohammadi, A. V., Rosen, J., and Gogotsi, Y. (2021). The World of Two-Dimensional Carbides and Nitrides (MXenes). Science 372, 1165. doi:10.1126/science.abf1581

Prabaswara, A., Kim, H., Min, J.-W., Subedi, R. C., Anjum, D. H., Davaasuren, B., et al. (2020). Titanium Carbide MXene Nucleation Layer for Epitaxial Growth of High-Quality GaN Nanowires on Amorphous Substrates. ACS Nano 14, 2202–2211. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b09126

Qiu, Z. M., Bai, Y., Gao, Y. D., Liu, C. L., Ru, Y., Pi, Y, C., et al. (2021). MXenes Nanocomposites for Energy Storage and Conversion. Rare Met. 41 1101–1128. doi:10.1007/s12598-021-01876-0

Rameshbabu, R., Vinoth, R., Navaneethan, M., Hayakawa, Y., and Neppolian, B. (2017). Fabrication of Cu2MoS4 Hollow Nanotubes with rGO Sheets for Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Performance. Crystengcomm 19, 2475–2486. doi:10.1039/c6ce02337a

Regulacio, M. D., Wang, Y., Seh, Z. W., and Han, M.-Y. (2018). Tailoring Porosity in Copper-Based Multinary Sulfide Nanostructures for Energy, Biomedical, Catalytic, and Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 3042–3062. doi:10.1021/acsanm.8b00639

Wang, D. B., Fang, Y. X., Yu, W., Wang, L. L., Xie, H. Q., and Yue, Y. A. (2021). Significant Solar Energy Absorption of MXene Ti3C2Tx Nanofluids via Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C. 220, 12. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2020.110850

Xi, D. M., Xiao, M., Cao, J. F., Zhao, L. Y., Xu, N., and Long, S. R. (2020). NIR Light-Driving Barrier-free Group Rotation in Nanoparticles with an 88.3% Photothermal Conversion Efficiency for Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Mater. 32, 8. doi:10.1002/adma.201907855

Yang, Y., Jeon, J., Park, J.-H., Jeong, M. S., Lee, B. H., Hwang, E., et al. (2019). Plasmonic Transition Metal Carbide Electrodes for High-Performance InSe Photodetectors. ACS Nano 13, 8804–8810. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b01941

Yilmaz, M., Christofori, G., and Lehembre, F. (2007). Distinct Mechanisms of Tumor Invasion and Metastasis. Trends Mol. Med. 13, 535–541. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2007.10.004

Yuan, M., Xu, S., Zhang, Q., Zhao, B., Feng, B., Ji, K., et al. (2020). Bicompatible Porous Co3O4 Nanoplates with Intrinsic Tumor Metastasis Inhibition for Multimodal Imaging and DNA Damage-Mediated Tumor Synergetic Photothermal/photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 394, 124874. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124874

Zhang, C. J., Pinilla, S., McEvoy, N., Cullen, C. P., Anasori, B., Long, E., et al. (2017b). Oxidation Stability of Colloidal Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbides (MXenes). Chem. Mater. 29, 4848–4856. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00745

Zhang, K., Chen, W. X., Wang, Y., Li, J., Chen, H. P., Gong, Z. Y., et al. (2015). Cube-like Cu2MoS4 Photocatalysts for Visible Light-Driven Degradation of Methyl orange. Aip Adv. 5, 5. doi:10.1063/1.4926923

Zhang, K., Lin, Y., Muhammad, Z., Wu, C., Yang, S., He, Q., et al. (2017a). Active {010} Facet-Exposed Cu2MoS4 Nanotube as High-Efficiency Photocatalyst. Nano Res. 10, 3817–3825. doi:10.1007/s12274-017-1594-3

Zhang, K., Lin, Y. X., Wang, C. D., Yang, B., Chen, S. M., Yang, S., et al. (2016). Facile Synthesis of Hierarchical Cu2MoS4 Hollow Sphere/Reduced Graphene Oxide Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 13120–13125. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b03767

Zhang, Q., Song, Q. C., Wang, X. Y., Sun, J. Y., Zhu, Q., Dahal, K., et al. (2018). Deep Defect Level Engineering: a Strategy of Optimizing the Carrier Concentration for High Thermoelectric Performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 933–940. doi:10.1039/c8ee00112j

Zhang, R., Zheng, Y., Liu, T., Tang, N., Mao, L., Lin, L., et al. (2021). The Marriage of Sealant Agent between Structure Transformable Silk Fibroin and Traditional Chinese Medicine for Faster Skin Repair. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 1599–1603. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.018

Zhou, B., Su, M., Yang, D., Han, G., Feng, Y., Wang, B., et al. (2020). Flexible MXene/Silver Nanowire-Based Transparent Conductive Film with Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Electro-Photo-Thermal Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 12, 40859–40869. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c09020

Keywords: photothermal conversion, MXene, heterostructure, nanocomposite, electron migration

Citation: Li L, Zhang J, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Li S, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Shi L, Yuan S and Guo L (2022) A Strategy to Design Cu2MoS4@MXene Composite With High Photothermal Conversion Efficiency Based on Electron Transfer Regulatory Effect. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10:902312. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.902312

Received: 23 March 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 13 May 2022.

Edited by:

Zhe Wang, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeCopyright © 2022 Li, Zhang, Lin, Zhang, Li, Liu, Zhang, Shi, Yuan and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leilei Shi, c2hpbGxlaUBtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu; Shouzhang Yuan, cGhlbGl4QDEyNi5jb20=; Lihao Guo, MjAxNDEyMTMzNDZAc3R1LnhpZGlhbi5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.