95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. , 04 January 2022

Sec. Biomaterials

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.788574

This article is part of the Research Topic Bioactive Agents for Functionalization of Biomaterials for Precise Tissue Engineering View all 25 articles

Recently, the widespread use of antibiotics is becoming a serious worldwide public health challenge, which causes antimicrobial resistance and the occurrence of superbugs. In this context, MnO2 has been proposed as an alternative approach to achieve target antibacterial properties on Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans). This requires a further understanding on how to control and optimize antibacterial properties in these systems. We address this challenge by synthesizing δ-MnO2 nanoflowers doped by magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and potassium (K) ions, thus displaying different bandgaps, to evaluate the effect of doping on the bacterial viability of S. mutans. All these samples demonstrated antibacterial activity from the spontaneous generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) without external illumination, where doped MnO2 can provide free electrons to induce the production of ROS, resulting in the antibacterial activity. Furthermore, it was observed that δ-MnO2 with narrower bandgap displayed a superior ability to inhibit bacteria. The enhancement is mainly attributed to the higher doping levels, which provided more free electrons to generate ROS for antibacterial effects. Moreover, we found that δ-MnO2 was attractive for in vivo applications, because it could nearly be degraded into Mn ions completely following the gradual addition of vitamin C. We believe that our results may provide meaningful insights for the design of inorganic antibacterial nanomaterials.

Manganese oxides (MnO2) have been extensively studied due to the structural multiformity. The various structures, corresponding to different chemical and physical properties, have been widely applied in catalysis, batteries, sensors, molecular sieves, energy storage, etc. (Dawadi et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2020; Marciniuk et al., 2021; Ouyang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Particularly, δ-MnO2 has attracted considerable attention due to its unique layered structure, where its bandgap can be tuned by filling ions between the layers (Luo et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2017). Herein, δ-MnO2 samples with different bandgaps, doped by alkali metals such as magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), or potassium (K), has been used as antibacterial materials.

Recently, the abuse of antibiotics is becoming a serious worldwide public health challenge, which causes antimicrobial resistance and the occurrence of superbugs (Podder et al., 2018; Teng et al., 2020). It not only prolongs treatment but also declines life expectancy due to higher morbidity/mortality risk (Podder et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Estes et al., 2021). These serious public health challenges require the development of new bactericidal methods (Herman and Herman, 2014; Gatadi et al., 2021). With the development of nanotechnology, new antibacterial agents have arisen (Herman and Herman, 2014; Liu et al., 2020). These nanoscale agents may provide more effective and/or more convenient routes (Dizaj et al., 2014; Herman and Herman, 2014). Particularly, nanomaterials based on inorganic metal oxide semiconductors, i.e., CuO, ZnO, MgO, etc., have been considered as alternative antibacterial materials (Zhang et al., 2010; Bafekr and Jalal, 2018; Hong et al., 2018; Chandra et al., 2019; Ogunyemi et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2010; Baruah et al., 2021; Haider et al., 2021; Han et al., 2021; Qian et al., 2021), whose activities can easily be tuned by altering their morphology and/or component (Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015).

Generally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) can injure biomolecules by its strong oxidation potential (Sharifi et al., 2012; Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015; Podder et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2020). The oxidant activity of metal oxide semiconductor nanomaterials usually originates from light-induced oxidative properties to generate ROS, including hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide anions radicals (·O2−), and singlet oxygen (1O2) (Podder et al., 2018). The generation of ROS under light exposure comes from the photo-generated electron-hole pairs excited on the appropriate band levels through the absorption of light, which interact with water and then produce ROS (Hirakawa and Nosaka, 2002; Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015). In addition to photoexcitation, the ROS can also be produced by electrons trapped by the defects at the surface of materials in the absence of light (Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015; Hao et al., 2017). However, we found that doped agents, which can provide free electrons to induce the production of ROS, also result in the antibacterial activity without external light exposure. MnO2 has five different phases (α, β, γ, λ, and δ) and the different properties of each phase make it be extensively studied in the fields of catalysis (Suib, 2008; Truong et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2017). Moreover, MnO2 can effectively enhance the produce of ·OH in the aqueous solution via the excitation and formation of electron-hole pairs (Das et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2018; Chhabra et al., 2019). Particularly, δ-MnO2, with a unique layered crystalline structure, has aroused much investigation. By changing the quantity of filling ions between MnO2 layers, its doping level can easily be tuned (Golden et al., 1986; Luo et al., 2008; Geng et al., 2016).

We report herein the synthesis of δ-MnO2 nanoflowers doped by Mg, Na, and K ions to evaluate the effect of doping on the bacterial viability of Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans), a recognized cariogenic bacterium (Song et al., 2020; Afrasiabi et al., 2021). Here, the antibacterial properties of δ-MnO2 were probed in the dark (without external illumination). It was observed that all δ-MnO2 nanoflowers demonstrated an excellent antibacterial activity without external light exposure. Our data showed that in doped MnO2 nanoflowers the free electrons due to doping could induce the production of ROS, resulting in the antibacterial activity. Moreover, δ-MnO2 nanoflowers with narrower bandgap displayed a superior antibacterial ability, in which higher doping levels, providing more free electrons to induce the production of ROS, led to better antibacterial properties (following the order: K+>Na+>Mg2+). Furthermore, following the gradual addition of vitamin C, the δ-MnO2 could nearly be degraded into Mn ions completely, making this materials potential for in vivo applications (Liu et al., 2021).

Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, >99.5%, Sinopharm), sodium permanganate monohydrate (NaMnO4·H2O, ≥97%, Sigma-Aldrich), magnesium permanganate hydrate (Mg(MnO4)2·xH2O, Sigma-Aldrich), manganese sulfate monohydrate (MnSO4·H2O, >99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich), superoxide dismutase (SOD, 15KU, Gunn reagent), vitamin C (VC, 99%, Adamas), and all the chemicals were used without any further purification. De-ionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ) was used throughout the experiments.

SEM images were obtained by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Hitachi S-4800) which worked at 5 kV. To prepare the samples of SEM, the aqueous suspension including the nanoflowers was dripped on a Si wafer, followed by drying under the air condition. HRTEM images were obtained with a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, TECHAI G2S-TWIN) operated at 200 kV. To prepare the samples of HRTEM, the alcoholic suspension including the nanoflowers was dripped on a copper grid, followed by drying under the air condition. UV-VIS spectra were obtained from the powder of MnO2 with a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was characterized by a Rigaku D/Max-2550. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out using a Thermo Science ESCALAB 250Xi with monochromatic Al Kα (1486.7 eV). The binding energy (BE) was scaled, which regarded the C 1s line at 284.6 eV as the standard for calibration. All data were processed by using the CasaXPS software. The electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra were conducted on a Bruker A300 Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectrometer.

MnO2 nanoflowers were synthesized through hydrothermal methods as reported previously (Hu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). For K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers, 1.0 g KMnO4 and 0.4 g MnSO4 were added into the Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, together with 30 ml DI water. After stirring for 30 min, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated and stirred at 140°C for 1 h and then cooled down to room temperature. The obtained MnO2 nanoflowers were washed three times with ethanol and three times with DI water by successive cycles of centrifugation and removal of supernatant. Finally, the materials were dried at 60°C for 12 h in a vacuum oven for further use. The Na-doped and Mg-doped samples were prepared with the same procedure, except that the 1.0 g KMnO4 was replaced by 1.012 g NaMnO4·H2O or 0.84 g Mg(MnO4)2·xH2O, respectively.

Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) (UA159) were obtained from Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). S. mutans was cultured in brain heart infusion broth (BHI broth, Difco laboratories, United States) at 37°C in anaerobic system (N2 80%, H2 10%, CO2 10%). Bacteria were harvested at the exponential growth phase for the use of subsequent experiments.

The bacterial viability was assessed by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, S. mutans suspensions at a density of 1 × 106 colony forming units (CFUs)/ml were treated with the different concentrations of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers (100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml) in BHI at 37°C under standard anaerobic conditions (N2 80%, H2 10%, CO2 10%) for 24 h. After 24 h of anaerobic culture, 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added to each well and incubated in dark for 2 h. The supernatant was discarded, and the substrate was reacted in solution by dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance was tested at 490 nm wavelength using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, United States). All samples were performed in triplicate. The negative control was the S. mutans group without MnO2 nanoflowers treatment. By comparing the OD values (490 nm) of the negative control with that of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers, the inhibition percentage of bacterial viability was calculated by using the equation: [(OD (negative control)-OD (sample))/OD (negative control)]×100%.

Firstly, 1 × 1 cm sterile glass slides were placed in a 24-well plate, and 50 μl ∼106 CFU/ml S. mutans was added to each well. Then, 150 μl suspensions with different concentrations of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers (100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml) were added into the mixture, respectively. In addition, 200 μl ∼106 CFU/ml S. mutans was added to the control wells and anaerobically cultured for 24 h at 37°C. After 24 h of anaerobic culture, the crystal violet was fixed with methanol, stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet, moistened with sterile double steam water, and washed overnight. After drying, the crystal violet was dissolved with 90% ethanol and the absorbance was tested at 550 nm wavelength using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, United States). All samples were performed in triplicate. The negative control was the biofilm without MnO2 nanoflowers. By comparing the OD values (550 nm) of the negative control with that of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers, the inhibition percentage of biofilm formation was calculated by using the equation: [(OD (negative control)-OD (sample))/OD (growth control)]×100%

The mouse fibroblast cell line (L929) was obtained from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured in minimum essential medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin−streptomycin (Gibco, CA), at 37°C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cells without any exposure to nanoparticles served as the negative control. Cytotoxicity was assessed by using the MTT assay. Briefly, to evaluate the mitochondrial function and cell viability of L929 cells treated with different concentrations of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers (100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml), cells were seeded at a density of 104 cells/well on 96-well plates and then treated with particles at different concentrations for 24 h. After 24 h treatment, MTT solution (20 μl, 5 mg/ml) (Amersco, Solon, OH, United States) was added into each well and incubated for an additional 4 h in 37°C incubator. Subsequently, 150 μl DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance at 570 and 630 nm was measured by a microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Scientific, MA, United States).

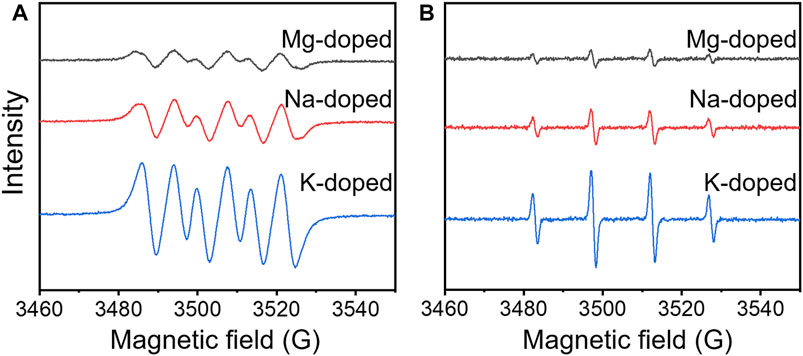

ESR spectroscopy was employed to detect ROS using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin trap (Bosnjakovic and Schlick, 2006; Szterk et al., 2011). DMPO traps ·OH to form DMPO−∙OH spin adduct which gives a quadrant signal. It also traps ·O2− to form DMPO−·O2− spin adduct which also gives a quadrant signal. To suspension of MnO2, DMPO was added and the ESR spectra were recorded. All the experiments were performed in dark.

Take K-doped MnO2 nanoflowers as example, the atomic radio between Mn and K was obtained with the quantitative analysis of high-resolution XPS spectra. We regarded IMn and IK as the Mn and K intensities from one Mn and K atom, respectively. The total intensities of Mn 2p3/2 and K 2p3/2 can be expressed by following expression (Hu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019):

where the layer-by-layer attenuation factor is given by k = exp (−c/λ sinθ). The c is the depth of atoms, λ is the photoelectron inelastic mean free path, and θ is the takeoff angle relative to the sample surface. Owing to the isotropic property of nanoflowers, k should be integrated to obtain the average. Thus, the layer-by-layer attenuation factor is given by the following expression:

The parameter c can be obtained by XRD. The photoelectron inelastic mean free path (λMn = 1.73 nm, λK = 2.25 nm) was calculated by using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database.

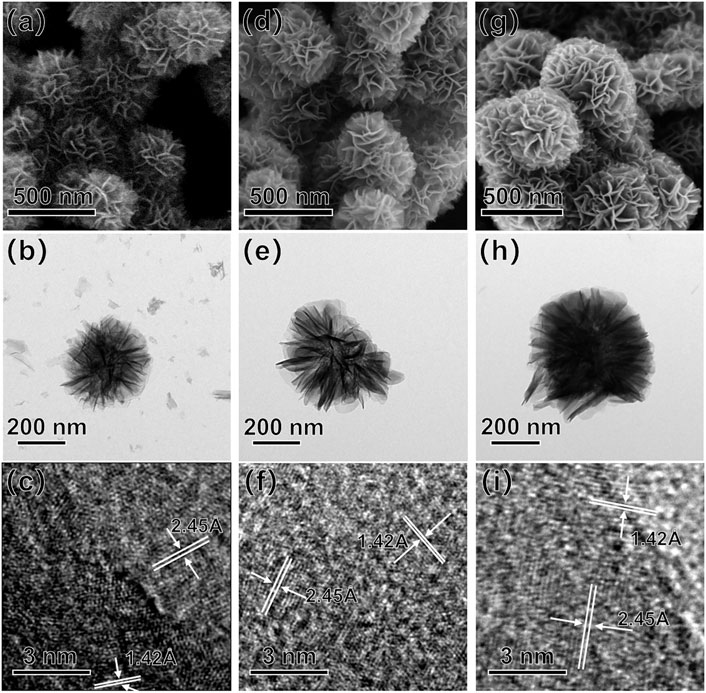

We started by using Mg(MnO4)2 as precursor to synthesize Mg-doped δ-MnO2 materials. Figure 1A shows the SEM image of Mg-doped MnO2, which presented a flower-like morphology and the size was ∼380 nm in diameter. Supplementary Figure S1A shows the XRD patterns of Mg-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers. All the peaks correspond to the crystal planes of δ-MnO2 (Hu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019), and no other crystalline phases were detected. Figures 1B,C present the TEM and HRTEM images of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers. The lattice spacings of 1.42 and 2.45 Å coincide with the (110) and (101) interlayer distance in δ-MnO2. This is also supported by the SAED patters shown in Supplementary Figure S2A.

FIGURE 1. SEM (A,D,G), TEM (B,E,H), and HRTEM (C,F,I) images of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers.

The band gap for the Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers was calculated as 1.13 eV from the UV-VIS spectrum shown in Supplementary Figure S3A. The narrower bandgap observed here relative to the previously reported (Sakai et al., 2005; John et al., 2016) might be attributed to the doping of Mg2+ ions between layers of MnO2 (Luo et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019), which will be discussed later.

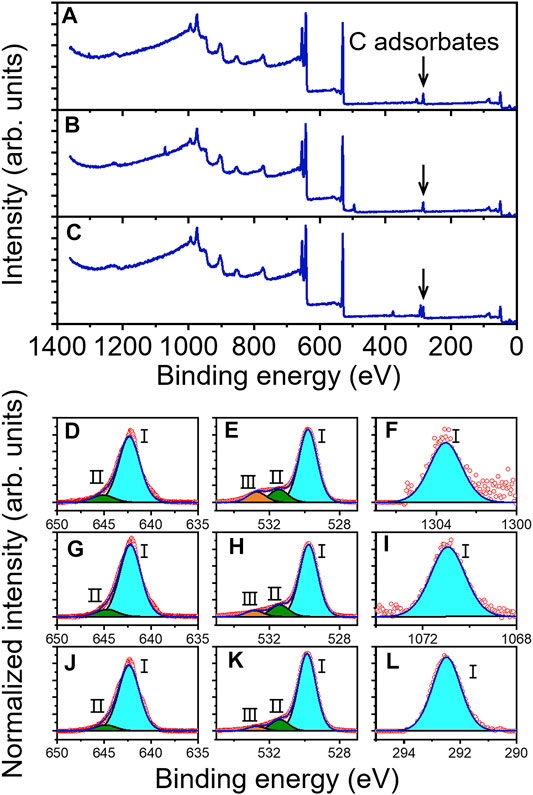

Figure 2A shows the XPS survey spectrum of Mg-doped MnO2. It was detected that, with a ∼15 min UV exposure, surface C contamination has a ∼8 times minor intensity relative to that of Mn 2p3/2. The binding energy (BE) values of different elements were presented in Supplementary Table S1. The Mn 2p3/2 core-level spectrum in Figure 2D presented two components. The main peak labeled I with low BE at 642.3 eV is due to bulk-coordinated Mn, and the other peak with high BE at 645.1 eV (peak II) corresponds to MnO2 interacted with absorbed oxygen from air (Selvakumar et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2020). However, no signal corresponding to reduced Mn3+, which is known to occur as a result of the formation of oxygen vacancies, was observed (Selvakumar et al., 2015). Figure 2E shows the O 1s core-level spectrum, which presented three components. The main peak (BE 529.9 eV) labeled I is due to bulk-coordinated oxygen. Peak II (BE 531.5 eV) and peak III (BE 532.9 eV) are attributed to the surface component and the carbonate or hydroxyl groups chemically bound on the surface, respectively (Tang et al., 2020; Arunpandiyan et al., 2021). Figure 2F presents the Mg 1s spectrum which only has one component. The BE of Mg 1s is 1303.5 eV, which is higher than that of Mg2Si (∼1302.3 eV) and Mg(OH)2 (∼1303 eV) (Esaka et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2017). The results indicate that Mg2+ is chemically bound to MnO2 (Nefedov, 1977). In the Mg 1s spectrum only one component was observed, suggesting that all Mg2+ ions were filled between the MnO2 layers (Hu et al., 2019).

FIGURE 2. Survey XPS scan of (A) Mg-doped, (B) Na-doped, and (C) K-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers. Core-level spectra for Mg-doped (D–F), Na-doped (G–I), and K-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers (J–L): (D,G,J) Mn 2p3/2, (E,H,K) O 1s, (F) Mg 1s, (I) Na 1s, and (L) K 2p3/2.

Since the biocompatibility of materials is a prerequisite for their intended use in the human body, in vitro cytotoxicity studies of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers were carried out prior to antibacterial testing. Specifically, L929 mouse fibroblastic cells were exposed for 24 h to different concentrations (0, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml) of MnO2 nanoflowers and then the cell viability was determined using the MTT assay, a well-established colorimetric method to evaluate the cytotoxicity of biomedical device according to ISO 10993-5:2009. After 24 h of incubation, the cell viability of L929 cells was more than 90% with the concentration of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers at 100–400 μg/ml, whereas it was reduced to 66 ± 5.7% when the dose was increased up to 800 μg/ml (Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that the MnO2 nanoflowers exhibited no or low cytotoxicity even at high concentration. When the concentration was higher than 400 μg/ml, an apparent decrease in cell viability was found, indicating high dose of MnO2 nanoparticles could induce cell death, which was consistent with our previous studies showing high concentrations of silica nanoparticles could induce cell necrosis in endothelial cells (Liu and Sun, 2010). It might be attributed to the higher cellular uptake of nanoparticles, which could directly damage cell plasma membranes and thus cause cell necrosis (Liu and Sun, 2010).

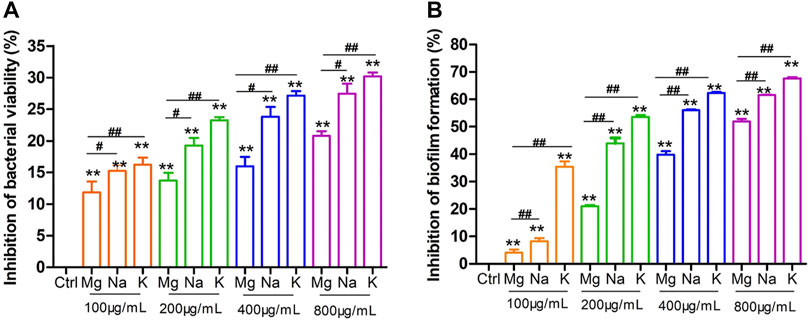

Then, the antibacterial activity of Mg-doped MnO2 sample was evaluated by detection of the bacterial viability and biofilm formation of S. mutans (Bijle et al., 2020; Daood et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020). Firstly, MTT assay was applied to evaluate the effect of Mg-doped MnO2 sample on the bacterial viability of S. mutans. As shown in Figure 3A, Mg-doped MnO2 can effectively inhibit bacterial viability. When the Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers at 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml concentration were added, the percentage of inhibition was 11.86 ± 2.18, 13.73 ± 1.45, 16.0 ± 1.83, and 20.79 ± 0.94%, respectively, reflecting that as the concentration of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers increases, the inhibition of bacterial viability shows an upward trend.

FIGURE 3. The inhibition effect of Mg-, Na-, and K-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers on S. mutans bacterial viability and biofilm formation at 24 h. (A) Bacterial viability by MTT assay. (B) Biofilm formation by crystal violet assay. Bacteria without nanoparticle treatment served as the negative control. Data represents mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. the negative control group; ##p < 0.01 significant difference as compared groups.

Generally, the MTT assay for assessment of antibacterial activity revealed the function of bacterial dehydrogenase system involved in metabolism (He et al., 2015). Furthermore, bacterial biofilm formation is known to increase resistance against the antibiotic and plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of infections (Banerjee et al., 2020). Then, we also examined the effect of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers on S. mutans biofilm formation by crystal violet staining (Asgharpour et al., 2019; Chan et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020), and the results showed the same trend as the MTT assay (Figure 3B). In the presence of Mg-doped MnO2, the inhibition percentage of biofilm formation was 4.1 ± 1.45% at 100 μg/ml, 21.02 ± 0.49% at 200 μg/ml, 39.86 ± 1.59% at 400 μg/ml, and 51.99 ± 1.18% at 800 μg/ml concentration, respectively, showing a dose-dependent enhanced antibacterial activity and reduced biofilm formation against S. mutans induced by Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers. Interestingly, these antibacterial tests were all performed in the dark.

From the above results, it was intriguing to find that the Mg-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers exhibited spontaneous antibacterial properties in the dark. Since it is established that ROS is responsible for antibacterial activity in the dark (Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015), their formation was investigated by electron spin resonance (ESR) using DMPO as a quencher without external illumination. Figures 4A,B show the characteristic DMPO-·O2− and DMPO-·OH signals in the case of Mg-doped MnO2 nanoflowers at 800 μg/ml concentration (Peng et al., 2021; Zong et al., 2021). The results show that both superoxide radicals (O2−) and hydroxyl radical (

FIGURE 4. ESR spin trapping spectra of (A) DMPO-·O2− and (B) DMPO-·OH on Mg-, Na-, and K-doped δ-MnO2 nanoflowers in the dark.

It has been reported that ZnO and MgO nanoparticles produced ROS in the dark due to the transfer of electrons trapped by the oxygen vacancies at the surface of materials (Prasanna and Vijayaraghavan, 2015; Hao et al., 2017). However, in our case, the presence of oxygen vacancies on the δ-MnO2 surface was not detected from the XPS results (Selvakumar et al., 2015). For the Mg 1s core-level spectrum in Figure 2F, it can be observed that Mg is chemically bound to MnO2, and thus, the valence electrons of Mg were transferred to MnO2, becoming free electrons. It implies that the production of ROS in the dark might be produced by the free electrons in δ-MnO2 coming from doping.

In order to further confirm this hypothesis, NaMnO4 and KMnO4 were employed to synthesize the Na- and K-doped δ-MnO2 as similarly described for Mg-doped δ-MnO2. In this case, it has been established that these δ-MnO2 samples can enable higher doping levels relative to Mg-doped δ-MnO2, which can lead to an increase number of free electrons (Hu et al., 2019). Figures 1D,G present their SEM images. These MnO2 samples showed similar flower-like morphology as that of Mg-doped ones, and the sizes were ∼460 nm in diameter (Na-doped MnO2) and ∼500 nm in diameter (K-doped MnO2), respectively. From the XRD patterns in Supplementary Figures S1B,C, it was observed that they all presented very similar crystalline structures to Mg-doped sample. Figures 1E,H present their TEM images. The HRTEM images depicted in Figures 1F,I, as well as SAED patterns in Supplementary Figure S2B,C, display the same lattice spacings (1.42 and 2.45 Å) of MnO2 as that of Mg-doped δ-MnO2. The bandgaps were calculated from UV-VIS spectra (Supplementary Figures S3B,C, respectively), which were 1.06 (Na-doped MnO2) and 0.75 eV (K-doped MnO2), respectively.

Figures 2B,C display the XPS survey spectra of Na- and K-doped MnO2. In Figure 2I,L, it presented only one component in both Na 1s and K 2p3/2 spectra. The BE of Na 1s (1070.9 eV) is higher than that of NaOH (∼1069.6 eV), while the BE of K 2p3/2 (292.5 eV) is higher than that of KF (∼292.2 eV) (Oh et al., 2013). Thus, it indicates that Na+ or K+ ions were also filled between the layers of MnO2 (Hu et al., 2019). In Figures 2G,J, Mn 2p3/2 core-level spectra presented 2 components, which was consistent with the Mg-doped MnO2 sample. The BE of peak II are 644.9 (Na-doped MnO2) and 644.7 eV (K-doped MnO2), respectively, which are 0.2 and 0.4 eV lower than the corresponding peaks of Mg-doped MnO2. Meanwhile, the BE of peak II and III of O 1s peak for Na-doped and K-doped samples also shift to lower BE values relative to those of Mg-doped sample. These variations demonstrate that between MnO2 and doped ions, it occurred a charge transfer (Luo et al., 2000; Gupta et al., 2018). The reason can be explained by the different doping levels as follows.

The atomic ratios calculated from the XPS data for Mg/Mn (Mg-doped MnO2), Na/Mn (Na-doped MnO2), and K/Mn (K-doped MnO2) were 1:626, 1:52, and 1:7, respectively. Details on these calculations are described in the experimental section (Hu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). This difference might be that the bigger size of ions results in larger interaction between ions and MnO2 layers, because the ions presented the size of K+>Na+>Mg2+ (Hu et al., 2019). Therefore, the difference in the amounts of doping ions in MnO2 results in the variance in the bandgap values, and meanwhile contribute to the lower BE of Mn and O peaks in Na- and K-doped samples relative to those of Mg-doped ones.

Then, MnO2 doped by Na+ and K+ ions were employed to evaluate the effect of free electrons quantity on the bacterial viability and biofilm formation of S. mutans in the dark. In vitro cytotoxicity studies were also tested. The experimental procedure was the same as that of Mg-doped MnO2 samples, and the results were described in Supplementary Figure S4. Consistent with the cytotoxicity results of Mg-doped MnO2, neither Na- nor K-doped MnO2 had a significant effect on cell viability at concentration below 400 μg/ml, while a slight reduction in cell viability was observed at 800 μg/ml. Thus, the MTT assay showed no significant cytotoxicity for MnO2 against L929 cells when the concentration was no more than 400 μg/ml. It was noted that K-doped MnO2 had the least cytotoxicity, while Mg-doped MnO2 displayed higher cytotoxicity than Na-doped MnO2 sample. According to ISO 10993-5:2009, the biocompatibility of K-doped MnO2 was very much within the acceptable limits even at a concentration as high as 800 μg/ml.

Subsequently, we used both the MTT assay and crystal violet staining assay to evaluate the effect of MnO2 nanoflowers with different doping on the bacterial viability and biofilm formation of S. mutans. As shown in Figure 3A, the inhibition of S. mutans bacterial viability exposed to Na-doped MnO2 nanoflowers at 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml concentration was 15.25 ± 1.11, 19.26 ± 1.39, 23.81 ± 1.83, and 27.46 ± 1.82%, respectively. Meanwhile the inhibition with K-doped MnO2 at concentrations of 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml was 16.22 ± 1.38, 23.26 ± 0.65, 27.13 ± 0.98, and 30.20 ± 0.77%, respectively, reflecting that as the concentrations of MnO2 nanoflowers increases, the antibacterial activity shows an upward trend.

From Figure 3B, in the presence of Na-doped MnO2, the inhibition of biofilm formation was 8.25 ± 1.48% at 100 μg/ml, 44.0 ± 2.40% at 200 μg/ml, 56.0 ± 0.46% at 400 μg/ml, and 61.57 ± 0.24% at 800 μg/ml, respectively. In the presence of K-doped MnO2, the inhibition of biofilm formation was 35.44 ± 2.28% at 100 μg/ml, 53.56 ± 1.00% at 200 μg/ml, 62.38 ± 0.46% at 400 μg/ml, and 67.61 ± 0.61% at 800 μg/ml, respectively. Obviously, both MTT assay and crystal violet staining have shown that K-doped MnO2 has the superior antibacterial and antibiofilm formation ability, which is better than that of Na-doped sample. Meanwhile, the Mg-doped MnO2 had the lowest antibacterial activity. Therefore, these results confirm the hypothesis that higher doping levels could provide more free electrons, which enhanced the antibacterial properties in doped δ-MnO2.

Figures 4A,B also show the characteristic DMPO-·O2− and DMPO-·OH signals in the case of Na- and K-doped MnO2 (Peng et al., 2021; Zong et al., 2021). The results show that both

In aqueous solutions, the free electrons in δ-MnO2 coming from doping can transfer to the water around it and form ·O2−, while ·OH is known as a derivative of

Supplementary Figure S6 presented the controllable degradation behavior of δ-MnO2. Following the gradual addition of vitamin C into the suspension with δ-MnO2 samples, it started to fade color, which indicated that MnO2 could be degraded in the presence of vitamin C. When the quantity of vitamin C was 14 times over MnO2 samples, it observed a nearly complete degradation of MnO2 into water soluble Mn ions, which can be rapidly excreted from the body, making this materials potential for in vivo applications, presenting not only an outstanding antibacterial efficacy but also an excellent biosafety (Liu et al., 2021).

δ-MnO2 nanoflowers doped by Mg, Na, and K ions were successful synthesized and their bandgap tunable antibacterial properties and controllable degradability mediated by vitamin C were systematically investigated. Interestingly, it was observed that all the samples showed antibacterial activity in the dark, and the antibacterial activity increased with doping levels, which was favored in the K+>Na+>Mg2+ order. Our data suggest that doped MnO2 can provide free electrons to induce the production of ROS and result in the antibacterial activity in the dark. Moreover, it is shown that higher doping levels can provide more free electrons, which enhance the antibacterial activity of the δ-MnO2 materials. Following the gradual addition of vitamin C, MnO2 nanoflowers could nearly be degraded into water soluble Mn ions completely, indicating that these materials also display biosafety. We believe that our results shed light on the design and fabrication of antibacterial nanomaterials with tailored properties.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YY (investigation, writing—original draft); NJ (methodology, investigation, analysis); XL (conceptualization, project administration); JP (conceptualization, funding acquisition); ML (investigation, analysis); CW (investigation, analysis); PC (methodology, analysis); JW (conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition).

This work was supported by Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (20ZR1401700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21703031, 81971751, 22005046, and 61376017), Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Fund (19ZR1445500, 20Y11904100), innovative research team of high-level local universities in Shanghai (SSMU-ZDCX20180900), and the Research Discipline fund No. KQYJXK2020 from Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, and College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2021.788574/full#supplementary-material

Afrasiabi, S., Bahador, A., and Partoazar, A. (2021). Combinatorial Therapy of Chitosan Hydrogel-Based Zinc Oxide Nanocomposite Attenuates the Virulence of Streptococcus Mutans. BMC Microbiol. 21, 62. doi:10.1186/s12866-021-02128-y

Arunpandiyan, S., Vinoth, S., Pandikumar, A., Raja, A., and Arivarasan, A. (2021). Decoration of CeO2 Nanoparticles on Hierarchically Porous MnO2 Nanorods and Enhancement of Supercapacitor Performance by Redox Additive Electrolyte. J. Alloys Compd. 861, 158456. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.158456

Asgharpour, F., Moghadamnia, A. A., Zabihi, E., Kazemi, S., Ebrahimzadeh Namvar, A., Gholinia, H., et al. (2019). Iranian Propolis Efficiently Inhibits Growth of Oral Streptococci and Cancer Cell Lines. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 19, 266. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2677-3

Banerjee, S., Vishakha, K., Das, S., Dutta, M., Mukherjee, D., Mondal, J., et al. (2020). Antibacterial, Anti-biofilm Activity and Mechanism of Action of Pancreatin Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 190, 110921. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110921

Baruah, R., Yadav, A., and Das, A. M. (2021). Livistona Jekinsiana Fabricated ZnO Nanoparticles and Their Detrimental Effect towards Anthropogenic Organic Pollutants and Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Spectrochimica Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 251, 119459. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2021.119459

Bijle, M. N., Neelakantan, P., Ekambaram, M., Lo, E. C. M., and Yiu, C. K. Y. (2020). Effect of a Novel Synbiotic on Streptococcus Mutans. Sci. Rep. 10, 7951. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-64956-8

Bosnjakovic, A., and Schlick, S. (2006). Spin Trapping by 5,5-Dimethylpyrroline-N-Oxide in Fenton media in the Presence of Nafion Perfluorinated Membranes: Limitations and Potential. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 10720–10728. doi:10.1021/jp061042y

Carré, G., Benhamida, D., Peluso, J., Muller, C. D., Lett, M.-C., Gies, J.-P., et al. (2013). On the Use of Capillary Cytometry for Assessing the Bactericidal Effect of TiO2. Identification and Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 12, 610–620. doi:10.1039/c2pp25189b

Chan, A., Ellepola, K., Truong, T., Balan, P., Koo, H., and Seneviratne, C. J. (2020). Inhibitory Effects of Xylitol and Sorbitol on Streptococcus Mutans and Candida Albicans Biofilms Are Repressed by the Presence of Sucrose. Arch. Oral Biol. 119, 104886. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104886

Chandra, H., Patel, D., Kumari, P., Jangwan, J. S., and Yadav, S. (2019). Phyto-mediated Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles of Berberis Aristata: Characterization, Antioxidant Activity and Antibacterial Activity with Special Reference to Urinary Tract Pathogens. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 102, 212–220. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.035

Chhabra, T., Kumar, A., Bahuguna, A., and Krishnan, V. (2019). Reduced Graphene Oxide Supported MnO2 Nanorods as Recyclable and Efficient Adsorptive Photocatalysts for Pollutants Removal. Vacuum 160, 333–346. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.11.053

Dadi, R., Azouani, R., Traore, M., Mielcarek, C., and Kanaev, A. (2019). Antibacterial Activity of ZnO and CuO Nanoparticles against Gram Positive and Gram Negative Strains. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 104, 109968. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.109968

Daood, U., Burrow, M. F., and Yiu, C. K. Y. (2020). Effect of a Novel Quaternary Ammonium Silane Cavity Disinfectant on Cariogenic Biofilm Formation. Clin. Oral Invest. 24, 649–661. doi:10.1007/s00784-019-02928-7

Das, S., Samanta, A., and Jana, S. (2017). Light-Assisted Synthesis of Hierarchical Flower-like MnO2 Nanocomposites with Solar Light Induced Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 9086–9094. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02003

Dawadi, S., Gupta, A., Khatri, M., Budhathoki, B., Lamichhane, G., and Parajuli, N. (2020). Manganese Dioxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Application and Challenges. Bull. Mater. Sci. 43, 277. doi:10.1007/s12034-020-02247-8

Dizaj, S. M., Lotfipour, F., Barzegar-Jalali, M., Zarrintan, M. H., and Adibkia, K. (2014). Antimicrobial Activity of the Metals and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 44, 278–284. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.031

Esaka, F., Nojima, T., Udono, H., Magara, M., and Yamamoto, H. (2016). Non-destructive Depth Analysis of the Surface Oxide Layer on Mg2 Si with XPS and XAS. Surf. Interf. Anal. 48, 432–435. doi:10.1002/sia.5939

Estes, L. M., Singha, P., Singh, S., Sakthivel, T. S., Garren, M., Devine, R., et al. (2021). Characterization of a Nitric Oxide (NO) Donor Molecule and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticle (CNP) Interactions and Their Synergistic Antimicrobial Potential for Biomedical Applications. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 586, 163–177. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2020.10.081

Gatadi, S., Madhavi, Y. V., and Nanduri, S. (2021). Nanoparticle Drug Conjugates Treating Microbial and Viral Infections: A Review. J. Mol. Struct. 1228, 129750. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129750

Geng, Z., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Li, G., Li, L., Huang, K., et al. (2016). δ-MnO2-Mn3O4 Nanocomposite for Photochemical Water Oxidation: Active Structure Stabilized in the Interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 8, 27825–27831. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b09984

Golden, D. C., Dixon, J. B., and Chen, C. C. (1986). Ion Exchange, thermal Transformations, and Oxidizing Properties of Birnessite. Clays and Clay Minerals 34, 511–520. doi:10.1346/ccmn.1986.0340503

Gupta, V. K., Fakhri, A., Azad, M., and Agarwal, S. (2018). Synthesis and Characterization of Ag Doped ZnS Quantum Dots for Enhanced Photocatalysis of Strychnine as a Poison: Charge Transfer Behavior Study by Electrochemical Impedance and Time-Resolved Photoluminescence Spectroscopy. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 510, 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2017.09.043

Haider, M. K., Ullah, A., Sarwar, M. N., Saito, Y., Sun, L., Park, S., et al. (2021). Lignin-mediated In-Situ Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles on Cellulose Nanofibers: A Potential Wound Dressing Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules 173, 315–326. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.01.050

Han, X., Zhang, G., Chai, M., and Zhang, X. (2021). Light-assisted Therapy for Biofilm Infected Micro-arc Oxidation TiO2 Coating on Bone Implants. Biomed. Mater. 16, 025018. doi:10.1088/1748-605x/abdb72

Hao, Y.-J., Liu, B., Tian, L.-G., Li, F.-T., Ren, J., Liu, S.-J., et al. (2017). Synthesis of {111} Facet-Exposed MgO with Surface Oxygen Vacancies for Reactive Oxygen Species Generation in the Dark. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 9, 12687–12693. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b16856

He, J., Zhu, X., Qi, Z., Wang, C., Mao, X., Zhu, C., et al. (2015). Killing Dental Pathogens Using Antibacterial Graphene Oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 7, 5605–5611. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b01069

Herman, A., and Herman, A. P. (2014). Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: Their Toxicity and Mechanisms of Action. J. Nanosci. Nanotech. 14, 946–957. doi:10.1166/jnn.2014.9054

Hirakawa, T., and Nosaka, Y. (2002). Properties of O2- and OH Formed in TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions by Photocatalytic Reaction and the Influence of H2O2 and Some Ions. Langmuir 18, 3247–3254. doi:10.1021/la015685a

Hong, W.-E., Hsu, I.-L., Huang, S.-Y., Lee, C.-W., Ko, H., Tsai, P.-J., et al. (2018). Assembled Growth of 3D Fe3O4@Au Nanoparticles for Efficient Photothermal Ablation and SERS Detection of Microorganisms. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 5689–5697. doi:10.1039/c8tb00599k

Hu, S., Liu, X., Wang, C., Camargo, P. H. C., and Wang, J. (2019). Tuning Thermal Catalytic Enhancement in Doped MnO2-Au Nano-Heterojunctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 11, 17444–17451. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b03879

Ijaz, M., Zafar, M., Islam, A., Afsheen, S., and Iqbal, T. (2020). A Review on Antibacterial Properties of Biologically Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanostructures. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 30, 2815–2826. doi:10.1007/s10904-020-01603-9

Javedani Bafekr, J., and Jalal, R. (2018). In Vitro antibacterial Activity of Ceftazidime, unlike Ciprofloxacin, Improves in the Presence of ZnO Nanofluids under Acidic Conditions. IET nanobiotechnol. 12, 640–646. doi:10.1049/iet-nbt.2017.0119

Jiang, J., Zhang, C., Zeng, G.-M., Gong, J.-L., Chang, Y.-N., Song, B., et al. (2016). The Disinfection Performance and Mechanisms of Ag/lysozyme Nanoparticles Supported with Montmorillonite clay. J. Hazard. Mater. 317, 416–429. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.05.089

Jiang, M., Yan, L., Li, K. a., Ji, Z. h., and Tian, S. g. (2020). Evaluation of Total Phenol and Flavonoid Content and Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activities of Trollius Chinensis Bunge Extracts on Streptococcus Mutans. Microsc. Res. Tech. 83, 1471–1479. doi:10.1002/jemt.23540

Jiang, Y.-Z., Wang, Y.-L., Wang, C.-Y., Bai, L.-M., Li, X., and Li, Y.-B. (2017). Magnesium Hydroxide Whisker Modified via In Situ Copolymerization of N-Butyl Acrylate and Maleic Anhydride. Rare Met. 36, 997–1002. doi:10.1007/s12598-016-0826-0

John, R. E., Chandran, A., Thomas, M., Jose, J., and George, K. C. (2016). Surface-defect Induced Modifications in the Optical Properties of α-MnO2 Nanorods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 367, 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.153

Kasemets, K., Ivask, A., Dubourguier, H.-C., and Kahru, A. (2009). Toxicity of Nanoparticles of ZnO, CuO and TiO2 to Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Toxicol. Vitro 23, 1116–1122. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2009.05.015

Lakshmi Prasanna, V., and Vijayaraghavan, R. (2015). Insight into the Mechanism of Antibacterial Activity of ZnO: Surface Defects Mediated Reactive Oxygen Species Even in the Dark. Langmuir 31, 9155–9162. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02266

Li, K., Li, H., Xiao, T., Long, J., Zhang, G., Li, Y., et al. (2019). Synthesis of Manganese Dioxide with Different Morphologies for Thallium Removal from Wastewater. J. Environ. Manage. 251, 109563. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109563

Li, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, D., Zhao, J., and Zhang, H. (2017). Snowflake-like Core-Shell α-MnO2@δ-MnO2 for High Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 251, 344–354. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2017.08.146

Liu, W., Ge, H., Ding, X., Lu, X., Zhang, Y., and Gu, Z. (2020). Cubic Nano-Silver-Decorated Manganese Dioxide Micromotors: Enhanced Propulsion and Antibacterial Performance. Nanoscale 12, 19655–19664. doi:10.1039/d0nr06281b

Liu, X., Sui, B., Camargo, P. H. C., Wang, J., and Sun, J. (2021). Tuning Band gap of MnO2 Nanoflowers by Alkali Metal Doping for Enhanced Ferroptosis/phototherapy Synergism in Cancer. Appl. Mater. Today 23, 101027. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2021.101027

Liu, X., and Sun, J. (2010). Endothelial Cells Dysfunction Induced by Silica Nanoparticles through Oxidative Stress via JNK/P53 and NF-Κb Pathways. Biomaterials 31, 8198–8209. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.069

Luo, J., Zhang, Q., Garcia-Martinez, J., and Suib, S. L. (2008). Adsorptive and Acidic Properties, Reversible Lattice Oxygen Evolution, and Catalytic Mechanism of Cryptomelane-type Manganese Oxides as Oxidation Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3198–3207. doi:10.1021/ja077706e

Luo, J., Zhang, Q., and Suib, S. L. (2000). Mechanistic and Kinetic Studies of Crystallization of Birnessite. Inorg. Chem. 39, 741–747. doi:10.1021/ic990456l

Marciniuk, G., Ferreira, R. T., Pedroso, A. V., Ribas, A. S., Ribeiro, R. A. P., de Lázaro, S. R., et al. (2021). Enhancing Hydrothermal Formation of α-MnO2 Nanoneedles over Nanographite Structures Obtained by Electrochemical Exfoliation. Bull. Mater. Sci. 44, 62. doi:10.1007/s12034-020-02336-8

Morrison, C. J., Isenberg, R. A., and Stevens, D. A. (1988). Enhanced Oxidative Mechanisms in Immunologically Activated versus Elicited Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils: Correlations with Fungicidal Activity. J. Med. Microbiol. 25, 115–121. doi:10.1099/00222615-25-2-115

Nefedov, V. I. (1977). X-Ray Photoelectron Spectra of Halogens in Coordination Compounds. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenomena 12, 459–476. doi:10.1016/0368-2048(77)85097-4

Ogunyemi, S. O., Zhang, M., Abdallah, Y., Ahmed, T., Qiu, W., Ali, M. A., et al. (2020). The Bio-Synthesis of Three Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO, MnO2, and MgO) and Their Antibacterial Activity against the Bacterial Leaf Blight Pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 11, 588326. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.588326

Oh, J. H., Kang, Y. S., and Kang, S. W. (2013). Poly(vinylpyrrolidone)/KF Electrolyte Membranes for Facilitated CO2 Transport. Chem. Commun. 49, 10181–10183. doi:10.1039/c3cc46253f

Ouyang, Q., Wang, L., Ahmad, W., Rong, Y., Li, H., Hu, Y., et al. (2021). A Highly Sensitive Detection of Carbendazim Pesticide in Food Based on the Upconversion-MnO2 Luminescent Resonance Energy Transfer Biosensor. Food Chem. 349, 129157. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129157

Peng, Y.-P., Liu, C.-C., Chen, K.-F., Huang, C.-P., and Chen, C.-H. (2021). Green Synthesis of Nano-Silver-Titanium Nanotube Array (Ag/TNA) Composite for Concurrent Ibuprofen Degradation and Hydrogen Generation. Chemosphere 264, 128407. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128407

Piccaro, G., Pietraforte, D., Giannoni, F., Mustazzolu, A., and Fattorini, L. (2014). Rifampin Induces Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7527–7533. doi:10.1128/aac.03169-14

Podder, S., Chanda, D., Mukhopadhyay, A. K., De, A., Das, B., Samanta, A., et al. (2018). Effect of Morphology and Concentration on Crossover between Antioxidant and Pro-oxidant Activity of MgO Nanostructures. Inorg. Chem. 57, 12727–12739. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01938

Qian, F., Zheng, Y., Pan, N., Li, L., Li, R., and Ren, X. (2021). Synthesis of Polysiloxane and its Co-application with Nano-SiO2 for Antibacterial and Hydrophobic Cotton Fabrics. Cellulose 28, 3169–3181. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-03704-1

Sakai, N., Ebina, Y., Takada, K., and Sasaki, T. (2005). Photocurrent Generation from Semiconducting Manganese Oxide Nanosheets in Response to Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 9651–9655. doi:10.1021/jp0500485

Selvakumar, K., Senthil Kumar, S. M., Thangamuthu, R., Ganesan, K., Murugan, P., Rajput, P., et al. (2015). Physiochemical Investigation of Shape-Designed MnO2 Nanostructures and Their Influence on Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activity in Alkaline Solution. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 6604–6618. doi:10.1021/jp5127915

Sharifi, S., Behzadi, S., Laurent, S., Laird Forrest, M., Stroeve, P., and Mahmoudi, M. (2012). Toxicity of Nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2323–2343. doi:10.1039/c1cs15188f

Sikora, P., Augustyniak, A., Cendrowski, K., Nawrotek, P., and Mijowska, E. (2018). Antimicrobial Activity of Al2O3, CuO, Fe3O4, and ZnO Nanoparticles in Scope of Their Further Application in Cement-Based Building Materials. Nanomaterials 8, 212. doi:10.3390/nano8040212

Song, Y.-M., Zhou, H.-Y., Wu, Y., Wang, J., Liu, Q., and Mei, Y.-F. (2020). In Vitro Evaluation of the Antibacterial Properties of Tea Tree Oil on Planktonic and Biofilm-Forming Streptococcus Mutans. AAPS Pharmscitech 21, 227. doi:10.1208/s12249-020-01753-6

Suib, S. L. (2008). Porous Manganese Oxide Octahedral Molecular Sieves and Octahedral Layered Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 479–487. doi:10.1021/ar7001667

Szterk, A., Stefaniuk, I., Waszkiewicz-Robak, B., and Roszko, M. (2011). Oxidative Stability of Lipids by Means of EPR Spectroscopy and Chemiluminescence. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 88, 611–618. doi:10.1007/s11746-010-1715-6

Tang, X., Wang, C., Gao, F., Ma, Y., Yi, H., Zhao, S., et al. (2020). Effect of Hierarchical Element Doping on the Low-Temperature Activity of Manganese-Based Catalysts for NH3-SCR. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104399. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2020.104399

Teng, X., Liu, X., Cui, Z., Zheng, Y., Chen, D.-f., Li, Z., et al. (2020). Rapid and Highly Effective Bacteria-Killing by polydopamine/IR780@MnO2-Ti Using Near-Infrared Light. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 30, 677–685. doi:10.1016/j.pnsc.2020.06.003

Truong, T. T., Liu, Y., Ren, Y., Trahey, L., and Sun, Y. (2012). Morphological and Crystalline Evolution of Nanostructured MnO2 and its Application in Lithium-Air Batteries. ACS Nano 6, 8067–8077. doi:10.1021/nn302654p

Wang, M., Shen, M., Zhang, L., Tian, J., Jin, X., Zhou, Y., et al. (2017). 2D-2D MnO2/g-C3n4 Heterojunction Photocatalyst: In-Situ Synthesis and Enhanced CO2 Reduction Activity. Carbon 120, 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2017.05.024

Wang, Z., Yan, X., Wang, F., Xiong, T., Balogun, M.-S., Zhou, H., et al. (2021). Reduced Graphene Oxide Thin Layer Induced Lattice Distortion in High Crystalline MnO2 Nanowires for High-Performance Sodium- and Potassium-Ion Batteries and Capacitors. Carbon 174, 556–566. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.12.071

Xia, T., Kovochich, M., Liong, M., Mädler, L., Gilbert, B., Shi, H., et al. (2008). Comparison of the Mechanism of Toxicity of Zinc Oxide and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Based on Dissolution and Oxidative Stress Properties. ACS Nano 2, 2121–2134. doi:10.1021/nn800511k

Xiao, L., Sun, W., Zhou, X., Cai, Z., and Hu, F. (2018). Facile Synthesis of Mesoporous MnO2 Nanosheet and Microflower with Efficient Photocatalytic Activities for Organic Dyes. Vacuum 156, 291–297. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.07.045

Xu, H., Ma, R., Zhu, Y., Du, M., Zhang, H., and Jiao, Z. (2020). A Systematic Study of the Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Cold Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma for Water Disinfection. Sci. Total Environ. 703, 134965. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134965

Yao, H., Huang, Y., Li, X., Li, X., Xie, H., Luo, T., et al. (2020). Underlying Mechanisms of Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress Photoinduced by Graphene and its Surface-Functionalized Derivatives. Environ. Sci. Nano 7, 782–792. doi:10.1039/c9en01295h

Ye, X., Jiang, X., Chen, L., Jiang, W., Wang, H., Cen, W., et al. (2020). Effect of Manganese Dioxide crystal Structure on Adsorption of SO2 by DFT and Experimental Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 521, 146477. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146477

Zhang, L., Pornpattananangkul, D., Hu, C.-M., and Huang, C.-M. (2010). Development of Nanoparticles for Antimicrobial Drug Delivery. Cmc 17, 585–594. doi:10.2174/092986710790416290

Zhou, G., Liu, H., Ma, Z., Li, H., and Pei, Y. (2017). Spatially Confined Li-Oxygen Interaction in the Tunnel of α-MnO2 Catalyst for Li-Air Battery: A First-Principles Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 16193–16200. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b01855

Zhu, K., Wang, C., Camargo, P. H. C., and Wang, J. (2019). Investigating the Effect of MnO2 Band gap in Hybrid MnO2-Au Materials over the SPR-Mediated Activities under Visible Light. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7, 925–931. doi:10.1039/c8ta09785b

Keywords: MnO2, doping, antibacterial property, reactive oxygen species, alkali metal ions

Citation: Yan Y, Jiang N, Liu X, Pan J, Li M, Wang C, Camargo PHC and Wang J (2022) Enhanced Spontaneous Antibacterial Activity of δ-MnO2 by Alkali Metals Doping. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9:788574. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.788574

Received: 02 October 2021; Accepted: 15 November 2021;

Published: 04 January 2022.

Edited by:

Rui Guo, Jinan University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yan, Jiang, Liu, Pan, Li, Wang, Camargo and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin Liu, bGl1eGluMDU1NkAxNjMuY29t; Jie Pan, amllcGFuQGZ1ZGFuLmVkdS5jbg==; Jiale Wang, amlhbGUud2FuZ0BkaHUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.