- 1Key Laboratory of Industrial Fermentation Microbiology, Ministry of Education, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China

- 2Tianjin Key Laboratory of Industrial Microbiology, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China

- 3College of Biotechnology, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China

- 4National Engineering Laboratory for Industrial Enzymes, Tianjin, China

Steroid hormones that serve as vital compounds are necessary for the development and metabolism of a variety of organisms. The neverland (NVD) family genes encode the conserved Rieske-type oxygenases, which are accountable for the dehydrogenation during the synthesis and regulation of steroid hormones. However, the His-tagged NVD protein from Caenorhabditis elegans expresses as inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). This bottleneck can be solved through refolding by urea or the introduction of a maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag at the N-terminus. Through further research on purification after the introduction of a MBP tag at the N-terminus, the CD measurement and fluorescence-based thermal shift assay indicated that MBP was favorable for the NVD proteins’ solubility and stability, which may be beneficial for the large-scale manufacture of NVD protein for further research. The structural model contained the Rieske [2Fe–2S] domain and non-heme iron-binding motif, which were similar to 3-ketosteroid 9 α-hydroxylase.

Introduction

Sterol derivatives mediate a wide range of growth, development, and evolution in most living species (Thummel and Chory, 2002). In insects, the steroid hormone ecdysone plays an essential role in the developmental transitions and egg production (Huang et al., 2008). The flies could not reach the adult stage when the synthesis for lathosterol was disabled by shutting down the NVD gene using the RNA interference (RNAi) in vivo. This matter can be solved by supplementing the standard food or lathosterol on time (Lang et al., 2012). The sterol metabolites also had many important properties, mostly related to the biosynthesis and regulation of amino acids and vitamins (Romero et al., 2005), which are involved in cholesterol homeostasis and synthesis of vitamin D3.

The metabolites of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) have raised a great concern due to its biological effects and physiological properties, such as calcium metabolism and phosphate homeostasis, regulation of immune responses, promotion of insulin secretion, and stimulation of cell proliferation and differentiation (Di Rosa et al., 2011). The vitamin D3 was synthesized in humans, and most of the vertebrate animals on the skin, in which the 7-dehydroxycholesterol (7-DHC) was converted into pre-vitamin D3 via ultraviolet (UV) irradiation at wavelengths of 290–320 nm and, meanwhile, followed by a thermal isomerization to form vitamin D3 spontaneously (Tripkovic et al., 2012). The high incidence of renal bone disease, osteomalacia and osteoporosis, was reported to be associated with the malabsorption of calcium, which is caused by a deficiency of vitamin D3 (Kanis, 1999). Compared with the chemosynthesis of 7-DHC using cholesterol (Dugas and Brunel, 2006), the bioconversion of cholesterol into 7-DHC has attracted more attention with regioselectivity and no pollution for the environment (Yoshiyama et al., 2006; Wollam et al., 2011; Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al., 2011; Lang et al., 2012). The reaction can be catalyzed by the evolutionarily conserved Rieske-domain oxygenase neverland (NVD), which contains a Rieske [2Fe–2S] cluster binding domain to function as an electron acceptor and electron transfer, and a highly conserved non-heme iron-binding center as a catalytic domain (Yoshiyama et al., 2006). Several Rieske-domain oxygenase genes from reptiles, insects, nematodes, and deuterostome species had been reported including Anolis carolinensis (protein ID XP_003230725.2), Anopheles gambiae (protein ID EAA04927.5) (Holt et al., 2002), Bombyx mori (protein ID BAE94192.1) (Yamanaka et al., 2005), Caenorhabditis elegans (protein ID CAA98235.2) (Rottiers et al., 2006), Ciona intestinalis (protein ID BAK39961.1) (Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al., 2011), Drosophila melanogaster (protein ID ABW08586.1) (Warren et al., 2002), Danaus plexippus (protein ID OWR46621.1) (Zhan et al., 2011), Danio rerio (protein ID BAK39960.1) (Yoshiyama et al., 2006), Gallus gallus (protein ID XP_425346.2) (Yoshiyama et al., 2006), Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus (protein ID BAK39963.1) (Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al., 2011), Rhodococcus rhodochrous (kshA, protein ID ADY18310.1) (Petrusma et al., 2011), Spodoptera littoralis (protein ID ADK56283.1) (Iga et al., 2013), Pseudomonas fluorescens (prnD, protein ID AAB97507.1) (Lee et al., 2005), Podarcis muralis (protein ID XP_028576239.1), Pseudonaja textilis (protein ID XP_026568371.1), and Xenopus laevis (protein ID BAK39959.1) (Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al., 2011). The family proteins are an essential regulator of cholesterol metabolism and steroidogenesis.

In addition, NVD from Caenorhabditis elegans (CeNVD) were identified in the metabolic pathway of cholesterol, and genetic evidence has demonstrated that the NVD gene plays a vital role in the larval development and adult aging in the ecdysteroid biosynthesis (Rottiers et al., 2006; Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al., 2011). However, there have been a few reports about the effective heterologous expression and production system of the NVD family proteins in vitro. Here, we verified that the NVD protein was expressed as inclusion bodies with His-tag (Zhu et al., 2019b), and a small amount of soluble protein was obtained, even though it was further refolded by urea. Subsequently, we introduced the maltose-binding protein (MBP) to enhance the soluble expression and purification of CeNVD in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3), and the thermostability of CeNVD was also improved.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The neverland gene from Caenorhabditis elegans (CeNVD) was chemically synthesized in pET-28a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI, United States) vector by GENEWZ (Suzhou, China) after codon was optimized. The DNA fragment of 1,110 bp was PCR amplified using gene-specific primers, which contain the EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites at the 5′- and 3′-terminal, and was cloned into the pMal-c2X (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, United States) plasmid vector, which contains an N-terminal MBP-tag and sequence. The E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) strain was employed as a heterologous expression host.

Expression and Purification

The recombinant plasmid was transformed into an E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain and grown in a Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml) with a shaking of 220 rpm at 37°C. When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6–0.8, 0.5 mM, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the culture, and the recombinant cells were cultivated with a shaking of 160 rpm at 16°C for 16–18 h to induce the protein expression. After cultivation, the recombinant cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and washed twice with PBS (pH 8.0) (Sun et al., 2019).

In order to purify the CeNVD_pET-28a(+), the washed cells were resuspended in a 30-ml lysis buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0) containing 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and disrupted using a sonicator (Sonic Dismembrator Model 100, Pittsburgh, PA, United States) on ice bath for 20 min, the unbroken cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose affinity chromatography matrix (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer A. After washing the open column with 10-ml of lysis buffer A extensively, the bound protein was eluted with a 10-ml elution buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl, 300 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0) (Mao et al., 2018).

For purification of the CeNVD_pMal-c2X, the amylose resin was applied to the fixed MBP_CeNVD fusion protein. The unbound protein was washed with lysis buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0), and the target protein was eluted with 10 ml of elution buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM maltose, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0) (Zhu et al., 2019b). Then the protein was further purified by an anion exchange chromatography employing a Resource Q column (column volume: 6 ml, flow rate: 4 ml/min, GE Healthcare, Stockholm, Sweden) on the ÄKTA system (GE Healthcare, Sweden) (Sun et al., 2018). The purified enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient between 0 and 1 M NaCl at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. Subsequently, the MBP tag was digested using a Factor Xa Protease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, United States) at 4°C for 12 h and then loaded on an amylose resin to remove the MBP tag and undigested protein. The flow-through buffer containing the target protein was collected and concentrated for further experiments.

Western Blot Analysis of CeNVD_pET-28a(+)

After the centrifugation of the disrupted CeNVD_pET-28a(+), the cleared supernatant and precipitant were loaded on SDS–PAGE gels, then all the protein molecules was transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked in a PBST buffer (PBS pH 8.0, 0.02% Tween-20) containing a 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 h, followed by incubation in an anti-His-tag mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), which was diluted in a blocking buffer (PBST pH 8.0, 1% BSA) at the indicated concentrations of 1:5,000 for 12 h at 4°C. After washing with PBST for four times, the membrane was protected from light and incubated with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, Tiangen Biochemical Technology, Beijing, China) at a dilution of 1:1,000 and room temperature for 2 h. After washing, the target protein was trapped by the HRP-DAB chromogenic substrate kit (Tiangen Biochemical Technology, Beijing, China), and the immunoreactive band was digitally scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imager (LI-COR Bio-science, Lincoln, NE, United States) (Wan et al., 2016).

The Refolding of Denatured Protein

The CeNVD_pET-28a(+) cells were collected and resuspended in lysis buffer C (20 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 8 M urea, and 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0), and then disrupted and centrifuged as mentioned above. The cleared supernatant containing the denatured enzyme was refolded by sequential dialysis with a gradient descent of urea concentrations (7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0.5, 0 M), then trapped on a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA superflow resin (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and washed with lysis buffer D (20 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM GSSG, 3 mM GSH, and 500 mM arginine, pH 8.0). The refolded protein was eluted with elution buffer D (20 mM Tris–HCl, 300 mM imidazole,300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM GSSG, 3 mM GSH, 500 mM arginine, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 8.0) (Qin et al., 2017a). The protein concentration of each purification step was measured via the BCA protein assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) (Qin et al., 2017b).

Molecular Mass Determination

The molecular weight of the native CeNVD was measured by a gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex200 Increase 10/300 GL column on the ÄKTA system (GE Healthcare, Sweden) (Zhu et al., 2019a). The target enzyme was eluted with a buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with aldolase (158 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa) as calibration proteins (GE Healthcare).

Circular Dichroism Measurements

The circular dichroism (CD) spectra was determined using a MOS-450 CD spectropolarimeter (Biologic, Claix, Charente, France). The protein sample was loaded into a 1-cm path-length quartz cuvette in which 0.1 mg/ml of protein was dissolved in PBS (pH 8.0), and the CD data were recorded in the far-UV band of 190–250 nm at room temperature for an average of four times scan with a rate of 1 nm/s, a bandwidth of 0.1 nm, and a step resolution of 0.1 nm (Zhu et al., 2019c). Analysis of the protein secondary structure was performed with the program BeStSel1 (Micsonai et al., 2015, 2018).

Fluorescence–Based Thermal Shift Assay

The thermal stability of CeNVD was characterized via the fluorescence-based thermal shift assay using a 48-well assay plate real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). Reaction samples were conducted in three replicates that contained 0.4 mg/ml of protein and 100 × SYPRO Orange dye in PBS buffer (pH 8.0). The temperature was increased with a linear gradient of 20–90°C at 0.5°C/30 s, and the minimal value was regarded as the melting temperature (Tm) (Mao et al., 2020a).

Structure Modeling of CeNVD

The three-dimensional (3D) homology model of CeNVD was generated by the SWISS-MODEL (swissmodel.expasy.org/) (Guex and Peitsch, 1997) using a template of 3-ketosteroid 9 α-hydroxylases from R. rhodochrous (PDB ID: 4QDF, 2.43 Å) (Penfield et al., 2014), which shared a 30% sequence identity with CeNVD. Then the generated models were visualized and analyzed using the PyMoL software2.

Results and Discussion

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

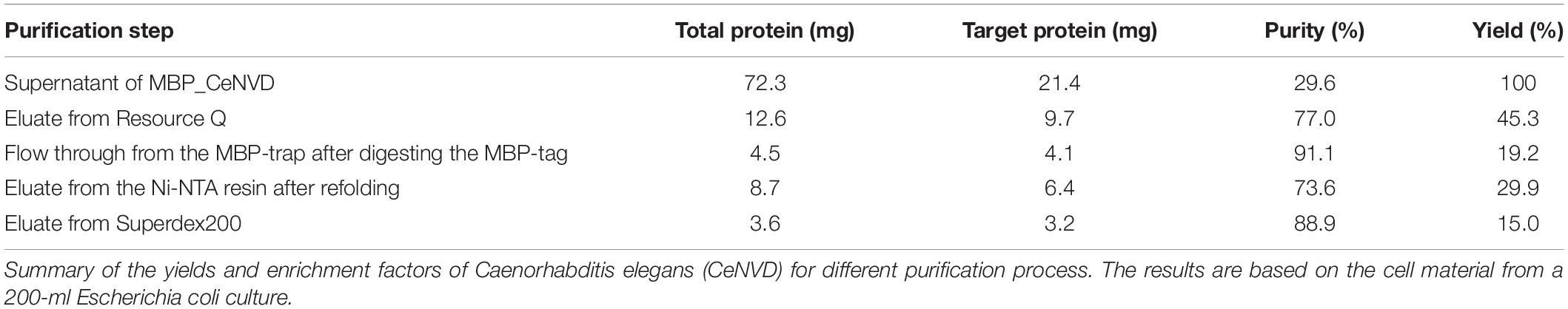

The phylogenetic tree of Rieske oxygenase from various microorganisms revealed that the evolutionary relationship of CeNVD was similar to that of C. intestinalis (Figure 1A) with 41.8% amino acid sequence identity. It showed the lower sequence identity of 30.2% with B. mori. BLAST and sequence analysis indicated that the NVD from C. elegans shared a higher sequence identity with X. laevis (45.7%), D. rerio (44.9%), G. gallus (44.0%), C. intestinalis (41.8%), and A. gambiae (40.3%). Amino acid sequence alignment and analysis with the homologous proteins displayed that the family proteins contained two evolutionally conserved domains, Rieske [2Fe–2S] domain (C-X-H-X16-17-C-X2-H) and non-heme iron-binding motif [Fe(II); E/D-X3-D-X2-H-X4-H]. The conserved residues in CeNVD contained C122, H124, C143, H146 in the Rieske domain, and E230, D234, H237, H242 in the Fe (II) domain (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree of Caenorhabditis elegans (CeNVD) with family enzymes. (A) The phylogenetic analysis of Rieske oxygenases from different species. (B) Multiple alignment of CeNVD with other Rieske oxygenases; the green triangle (▲) and orange asterisk (∗) were responsible for the Rieske [2Fe–2S] domain (C-X-H-X16-17-C-X2-H) and non-heme iron-binding motif [Fe(II); E/D-X3-D-X2-H-X4-H], respectively. The alignment was prepared using the program ESPript 3.0 service (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/).

Heterologous Expression and Purification of CeNVD Recombinant Enzyme

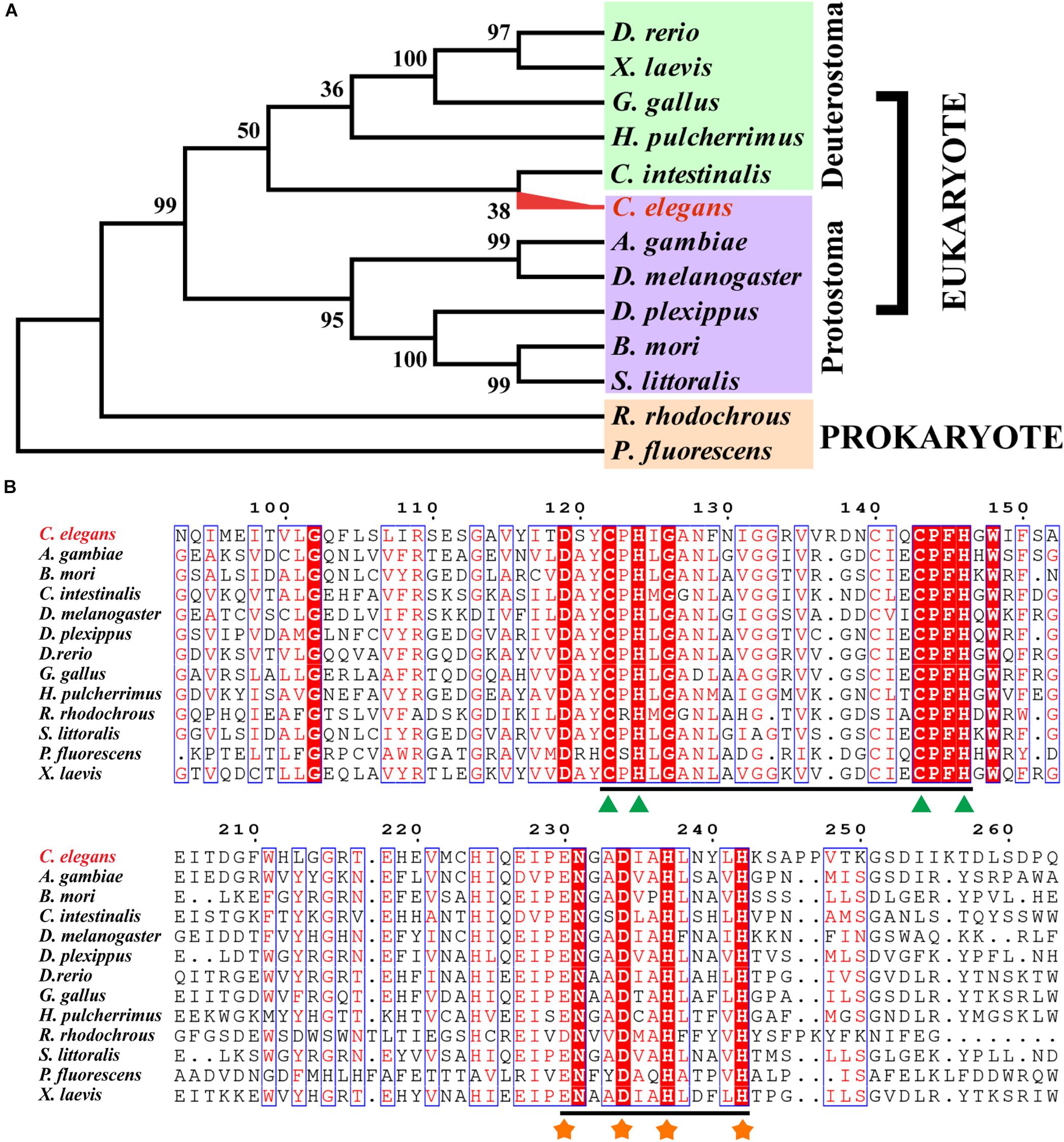

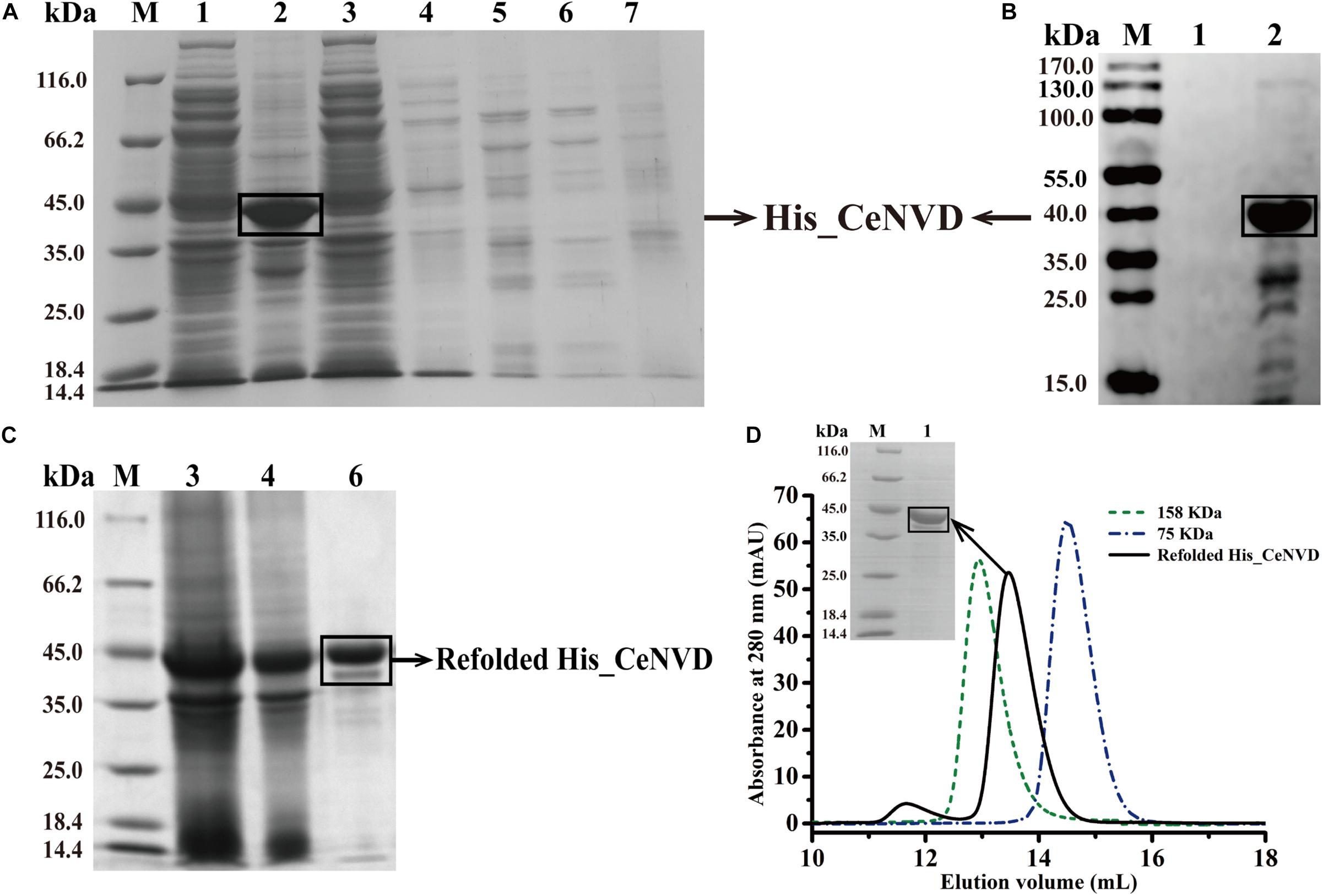

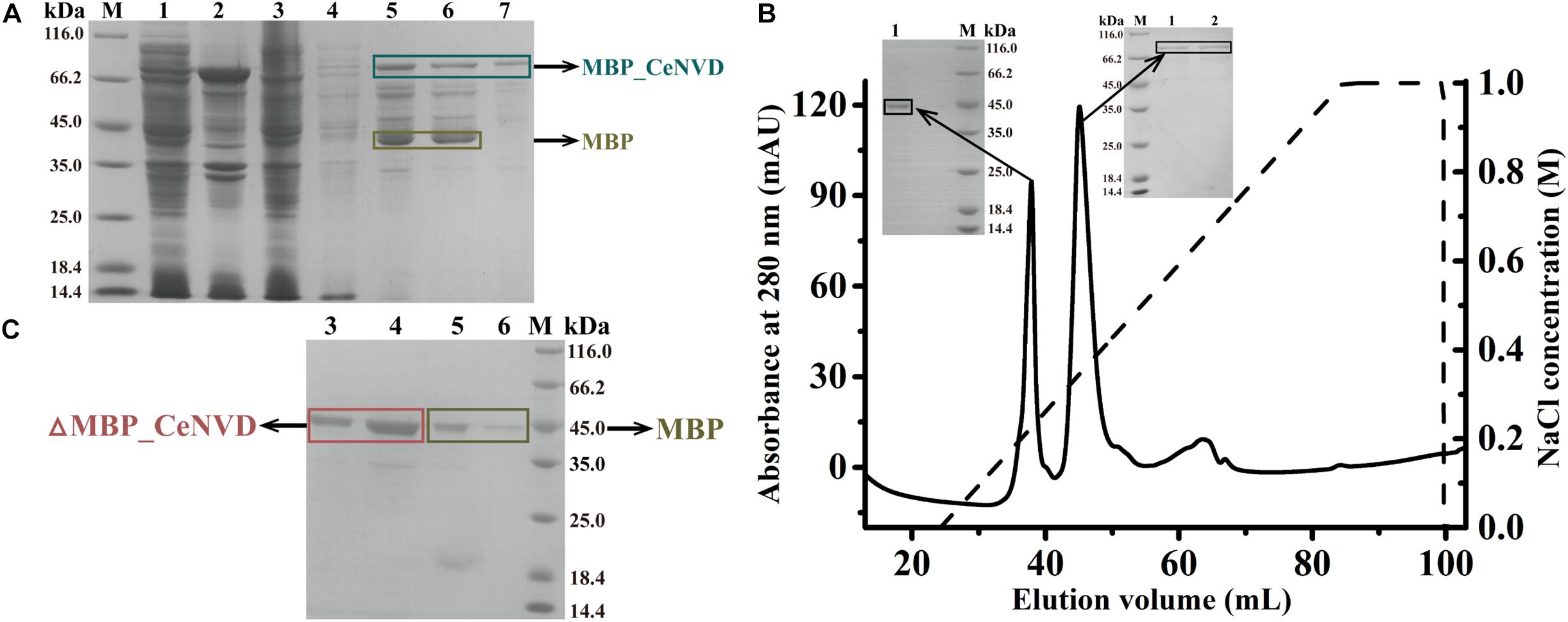

The CeNVD_pET28a(+) was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) and purified by the His-trap affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis demonstrated that the target protein appeared as a single band with a molecular mass of approximately 42 kDa, consistent with the calculated molecular weight of 42,800 Da. However, the protein was overwhelmingly expressed as inclusion bodies (Figures 2A,B). Subsequently, the CeNVD gene was cloned and inserted into pMal-c2X. The reconstructed enzyme was overexpressed and purified by a genericmultiple-step purification using an amylose fast flow resin and anion exchange chromatography (Figures 3A,B). The MBP-tag was then digested by a Factor Xa protease and removed by an amylose resin (Figure 3C). The yields and purities of CeNVD for the different purification stages are summarized in Table 1. Finally, 4.1 mg of CeNVD with 91.1% high purity was obtained in 200-ml of cell culture. Therefore, the MBP was advantageous to the soluble expression and purification of CeNVD in E. coli, and the purification multiple-step purification method was necessary to obtain highly purified recombinant CeNVD.

Figure 2. Purification of the CeNVD_pET28a(+) by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity chromatography. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of CeNVD_pET28a(+). (B) Western blot analysis of CeNVD_pET-28a(+). (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of the denatured and refolded protein. (D) Size-exclusion chromatography of the refolding protein, aldolase (158 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa) as reference proteins; Lanes 1: supernatant; 2: sediment; 3: flow-through; 4: wash buffer; 5: resin before eluting; 6: elution buffer; 7: resin after eluting.

Figure 3. (A) Purification of CeNVD_pMal-c2X by the MBP-trap affinity chromatography. (B) Purification of CeNVD_pMal-c2X by the anion-exchange. (C) Purification of CeNVD by the MBP-trap without the MBP tag. Lanes 1: supernatant; 2: sediment; 3: flow-through; 4: wash buffer; 5: resin before eluting; 6: elution buffer; 7: resin after eluting.

Characterization of the Refolded His_CeNVD

His_CeNVD was expressed as inclusion bodies. Therefore, we added arginine and urea to refold the protein with an extra redox system to improve the refolding yield, such as reduced and oxidized glutathione (GSH and GSSG) (Chen et al., 2016). Here, we used a gradient descent of urea with 500 mM arginine and a redox pair (GSH and GSSG) to facilitate the protein solubilizing and refolding. After dialysis, the refolded His_CeNVD was further purified by an Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Figure 2C), and the fraction was further analyzed through a gel filtration chromatography, and a single peak was detected at 280 nm. Consistent with the gel filtration chromatography analysis, SDS-PAGE indicated that the refolded His_CeNVD of higher purity (88.9%) (Table 1) was obtained and a trimer state in solution (Figure 2D).

Characterization of All CeNVD

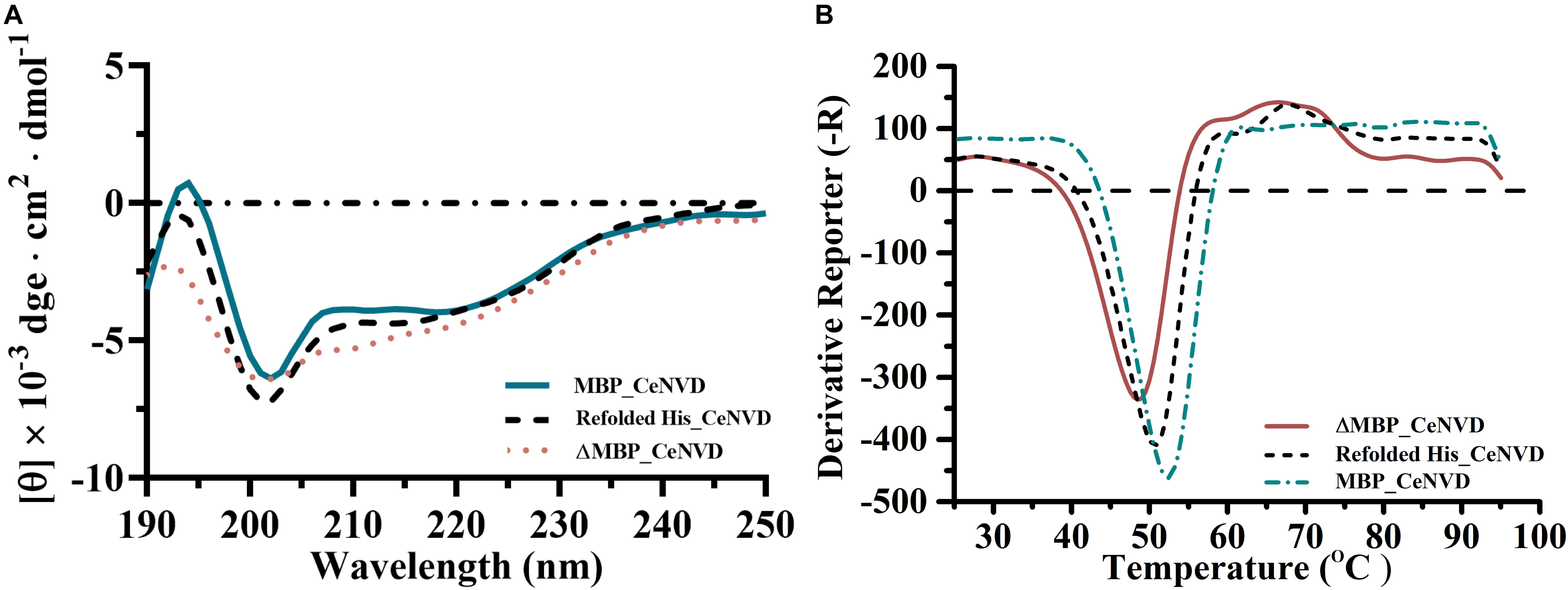

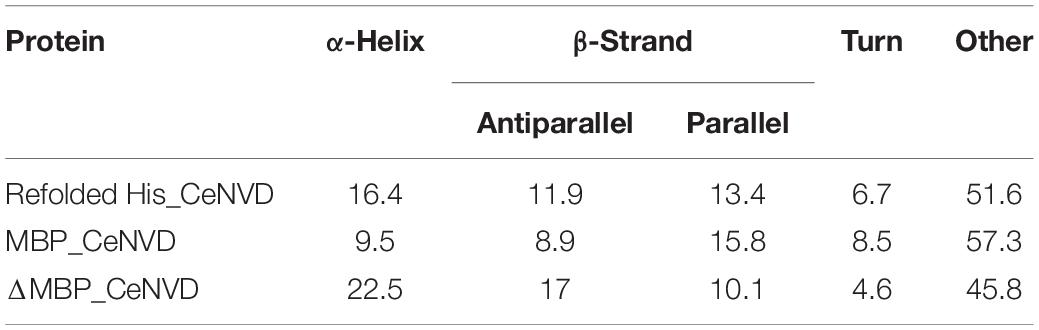

The secondary structure of the MBP_CeNVD, ΔMBP_CeNVD, and refolded His_CeNVD were measured by CD spectroscopy (Figure 4A). The MBP_CeNVD showed a negative absorption peak centered around 202 nm, and the percentage of α-helix, β-strand, turn, and unordered regions were 9.5%, 24.7%, 8.5%, and 57.3%, respectively. The CD spectrum of the ΔMBP_CeNVD and refolded protein demonstrated a visible increase in α-helix (22.5%, 16.4%) and a slight decrease in turn structures (4.6%, 6.7%) and unstructured regions (45.8% and 51.6%) (Table 2).

Figure 4. (A) The CD spectra and (B) melting curves of CeNVD. The experiments were conducted in three replicates, and the data represent the means ± standard deviations.

Table 2. Secondary structure assignments (%) of CeNVD determined by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy in the wavelength region from 190 to 250 nm.

Fluorescence-based thermal shift assay was used to determine the thermostability of the three types of CeNVD. As shown in Figure 4B, the Tm value of the MBP_CeNVD was higher than the His_CeNVD and ΔMBP-NVD (52.5°C, 50°C, and 48°C), which suggested that the MBP was profitable for the thermostability of CeNVD.

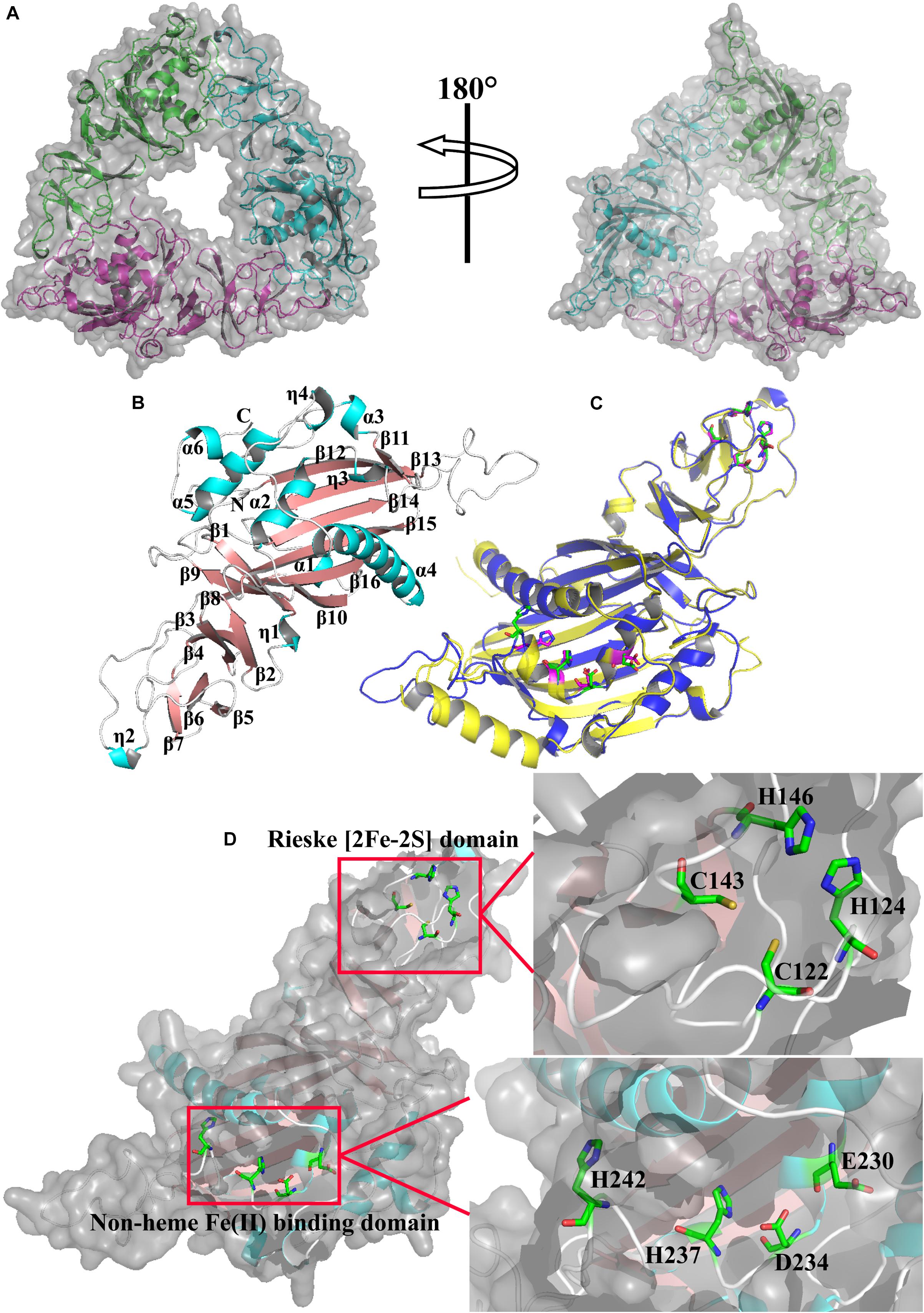

Structural Analysis of CeNVD

The structure of CeNVD contains six α-helices (α1–α6) and 16 antiparallel β-strands (β1–β16) (Figures 5A,B), which are conserved in the NVD family enzymes. It contains an N-terminal Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster (C122, H124, C143, H146) and followed by the catalytic domain harboring non-heme Fe (II) center (E230, D234, H237, H242). The Rieske cluster was located at strands β4, β5 and β6, β7. As for the Fe (II) center, E230 and D234 are located at α2, H237 is located at η3, and H242 is located on a loop between η3 and β11 (Figure 5D; Penfield et al., 2014). Structural alignment revealed that the structure and residues in the major domains are remarkably similar to that of 3-ketosteroid 9 α-hydroxylases from R. rhodochrous (C67, H69, C86, H89) and (D174, D178, H181, H186) (Figure 5C; Mao et al., 2020b).

Figure 5. (A) The structure model of CeNVD. (B) Monomer structure of CeNVD with the α-helices (cyan) and β-strands (salmon) are labeled. (C) The superimposed subunits of CeNVD (blue) and the 3-ketosteroid 9 α-hydroxylases from Rhodococcus rhodochrous (yellow) with major domains; residues are shown as green and magenta sticks. (D) The stereo view of Rieske [2Fe–2S] domain and non-heme Fe(II)-binding domain.

Conclusion

Our study provides a methodological approximation for the purification of soluble Rieske domain-containing oxygenase expressed in E. coli. We successfully expressed and purified the CeNVD protein in E. coli with the soluble formation of refolded His-NVD and MBP-NVD, showing that the MBP tag could increase the soluble expression of CeNVD, which is advantageous for further purification and improvement of thermostability.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

FL and H-MQ designed the research. SM, ZS, MW, and XW performed the experiments and analyzed the data. H-MQ, SM, and FL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Synthetic Biology Research (Grant No. 2019YFA0905300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771911 and 21878233), and Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (TSBICIP-KJGG-001-09).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-41569/v1, doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-41569/v1.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.593041/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Chen, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, C., Li, X., Gao, Q., Dong, C., et al. (2016). Improving the refolding efficiency for proinsulin aspart inclusion body with optimized buffer compositions. Protein Expr. Purif. 122, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.01.015

Di Rosa, M., Malaguarnera, M., Nicoletti, F., and Malaguarnera, L. (2011). Vitamin D3: a helpful immuno-modulator. Immunology 134, 123–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03482.x

Dugas, D., and Brunel, J. M. (2006). Synthesis of 7-dehydrocholesterol through a palladium catalyzed selective homoannular conjugated diene formation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 253, 119–122. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLCATA.2006.03.014

Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (1997). SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505

Holt, R. A., Subramanian, G. M., Halpern, A., Sutton, G. G., Charlab, R., Nusskern, D. R., et al. (2002). The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science 298, 129–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1076181

Huang, X., Warren, J. T., and Gilbert, L. I. (2008). New players in the regulation of ecdysone biosynthesis. J. Genet. Genomics 35, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60001-6

Iga, M., Blais, C., and Smagghe, G. (2013). Study on ecdysteroid levels and gene expression of enzymes related to ecdysteroid biosynthesis in the larval testis of Spodoptera littoralis. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 82, 14–28. doi: 10.1002/ARCH.21068

Kanis, J. A. (1999). Vitamin D analogs: from renal bone disease to osteoporosis. Kidney Int. 56, S77–S81. doi: 10.1046/J.1523-1755.1999.07317.X

Lang, M., Murat, S., Clark, A. G., Gouppil, G., Blais, C., Matzkin, L. M., et al. (2012). Mutations in the neverland gene turned Drosophila pachea into an obligate specialist species. Science 337, 1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1224829

Lee, J., Simurdiak, M., and Zhao, H. (2005). Reconstitution and characterization of aminopyrrolnitrin oxygenase, a Rieske N-oxygenase that catalyzes unusual arylamine oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36719–36727. doi: 10.1074/JBC.M505334200

Mao, S., Cheng, X., Zhu, Z., Chen, Y., Li, C., Zhu, M., et al. (2020a). Engineering a thermostable version of D-allulose 3-epimerase from Rhodopirellula baltica via site-directed mutagenesis based on B-factors analysis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 132:109411. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.109441

Mao, S., Song, Z., Wu, M., Wang, X., Lu, F., and Qin, H. M. (2020b). Expression, Purification, Refolding and Characterization of a Neverland Protein from Caenorhabditis elegans. Available online at: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-41569/v1 (accessed July 16, 2020).

Mao, S., Wang, J., Liu, F., Zhu, Z., Gao, D., Guo, Q., et al. (2018). Engineering of 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase based site-directed saturation mutagenesis for efficient biotransformation of steroidal substrates. Microb. Cell Fact. 17:141. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0981-0

Micsonai, A., Wien, F., Bulyaki, E., Kun, J., Moussong, E., Lee, Y. H., et al. (2018). BeStSel: a web server for accurate protein secondary structure prediction and fold recognition from the circular dichroism spectra. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W315–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky497

Micsonai, A., Wien, F., Kernya, L., Lee, Y. H., Goto, Y., Refregiers, M., et al. (2015). Accurate secondary structure prediction and fold recognition for circular dichroism spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E3095–E3103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500851112

Penfield, J. S., Worrall, L. J., Strynadka, N. C., and Eltis, L. D. (2014). Substrate specificities and conformational flexibility of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylases. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 25523–25536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.575886

Petrusma, M., Hessels, G., Dijkhuizen, L., and Van Der Geize, R. (2011). Multiplicity of 3-ketosteroid-9α-hydroxylase enzymes in Rhodococcus rhodochrous DSM43269 for specific degradation of different classes of steroids. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3931–3940. doi: 10.1128/JB.00274-11

Qin, H. M., Wang, J., Guo, Q., Li, S., Xu, P., Zhu, Z., et al. (2017a). Refolding of a novel cholesterol oxidase from Pimelobacter simplex reveals dehydrogenation activity. Protein Expr. Purif. 139, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/J.PEP.2017.07.008

Qin, H. M., Zhu, Z., Ma, Z., Xu, P., Guo, Q., Li, S., et al. (2017b). Rational design of cholesterol oxidase for efficient bioresolution of cholestane skeleton substrates. Sci. Rep. 7:16375. doi: 10.1038/S41598-017-16768-6

Romero, P., Wagg, J., Green, M. L., Kaiser, D., Krummenacker, M., and Karp, P. D. (2005). Computational prediction of human metabolic pathways from the complete human genome. Genome Biol. 6:R2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r2

Rottiers, V., Motola, D. L., Gerisch, B., Cummins, C. L., Nishiwaki, K., Mangelsdorf, D. J., et al. (2006). Hormonal control of C. elegans dauer formation and life span by a Rieske-like oxygenase. Dev. Cell 10, 473–482. doi: 10.1016/J.DEVCEL.2006.02.008

Sun, D., Gao, D., Liu, X., Zhu, M., Li, C., Chen, Y., et al. (2019). Redesign and engineering of a dioxygenase targeting biocatalytic synthesis of 5-hydroxyl leucine. Catal. Sci. Technol. 9, 1825–1834. doi: 10.1039/C9CY00110G

Sun, D., Gao, D., Xu, P., Guo, Q., Zhu, Z., Cheng, X., et al. (2018). A novel L-leucine 5-hydroxylase from Nostoc piscinale unravels unexpected sulfoxidation activity toward L-methionine. Protein Expr. Purif. 149, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/J.PEP.2018.04.009

Thummel, C. S., and Chory, J. (2002). Steroid signaling in plants and insects–common themes, different pathways. Genes Dev. 16, 3113–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.1042102

Tripkovic, L., Lambert, H., Hart, K., Smith, C. P., Bucca, G., Penson, S., et al. (2012). Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 1357–1364. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031070

Wan, D., Yang, X., Wang, Y., Zhu, H., Wang, T., Liu, Z., et al. (2016). Catalpol stimulates VEGF production via the JAK2/STAT3 pathway to improve angiogenesis in rats’ stroke model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 191, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/J.JEP.2016.06.030

Warren, J. T., Petryk, A., Marqués, G., Jarcho, M., Parvy, J. P., Dauphin-Villemant, C., et al. (2002). Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11043–11048. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.162375799

Wollam, J., Magomedova, L., Magner, D. B., Shen, Y., Rottiers, V., Motola, D. L., et al. (2011). The Rieske oxygenase DAF-36 functions as a cholesterol 7-desaturase in steroidogenic pathways governing longevity. Aging Cell 10, 879–884. doi: 10.1111/J.1474-9726.2011.00733.X

Yamanaka, N., Hua, Y. J., Mizoguchi, A., Watanabe, K., Niwa, R., Tanaka, Y., et al. (2005). Identification of a novel prothoracicostatic hormone and its receptor in the silkworm Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14684–14690. doi: 10.1074/JBC.M500308200

Yoshiyama, T., Namiki, T., Mita, K., Kataoka, H., and Niwa, R. (2006). Neverland is an evolutionally conserved Rieske-domain protein that is essential for ecdysone synthesis and insect growth. Development 133, 2565–2574. doi: 10.1242/DEV.02428

Yoshiyama-Yanagawa, T., Enya, S., Shimada-Niwa, Y., Yaguchi, S., Haramoto, Y., Matsuya, T., et al. (2011). The conserved Rieske oxygenase DAF-36/Neverland is a novel cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25756–25762. doi: 10.1074/JBC.M111.244384

Zhan, S., Merlin, C., Boore, J. L., and Reppert, S. M. (2011). The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration. Cell 147, 1171–1185. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2011.09.052

Zhu, Z., Gao, D., Li, C., Chen, Y., Zhu, M., Liu, X., et al. (2019a). Redesign of a novel D-allulose 3-epimerase from Staphylococcus aureus for thermostability and efficient biocatalytic production of D-allulose. Microb. Cell Fact. 18:59. doi: 10.1186/S12934-019-1107-Z

Zhu, Z., Li, C., Cheng, X., Chen, Y., Zhu, M., Liu, X., et al. (2019b). Soluble expression, purification and biochemical characterization of a C-7 cholesterol dehydrogenase from Drosophila melanogaster. Steroids 152:108495. doi: 10.1016/J.STEROIDS.2019.108495

Keywords: neverland, maltose-binding protein, refolding, soluble expression, structural model-3-

Citation: Mao S, Song Z, Wu M, Wang X, Lu F and Qin H-M (2020) Expression, Purification, Refolding, and Characterization of a Neverland Protein From Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:593041. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.593041

Received: 09 August 2020; Accepted: 24 September 2020;

Published: 21 October 2020.

Edited by:

Eduardo Jacob-Lopes, Federal University of Santa Maria, BrazilReviewed by:

Xiaoqiang Ma, Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), SingaporeDirk Tischler, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany

Copyright © 2020 Mao, Song, Wu, Wang, Lu and Qin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fuping Lu, bGZwQHR1c3QuZWR1LmNu; ZnVwaW5nbHUyMDE2QHNpbmEuY29t; Hui-Min Qin, aHVpbWlucWluQHR1c3QuZWR1LmNu

Shuhong Mao1,2,3,4

Shuhong Mao1,2,3,4 Zhan Song

Zhan Song Hui-Min Qin

Hui-Min Qin