95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. , 25 May 2020

Sec. Industrial Biotechnology

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00486

This article is part of the Research Topic Pathway, Genetic and Process Engineering of Microbes for Biopolymer Synthesis View all 13 articles

One of the major challenges for the present and future generations is to find suitable substitutes for the fossil resources we rely on today. In this context, cyanobacterial carbohydrates have been discussed as an emerging renewable feedstock in industrial biotechnology for the production of fuels and chemicals. Based on this, we recently presented a synthetic bacterial co-culture for the production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) from CO2. This co-cultivation system is composed of two partner strains: Synechococcus elongatus cscB which fixes CO2, converts it to sucrose and exports it into the culture supernatant, and a Pseudomonas putida strain that metabolizes this sugar and accumulates PHAs in the cytoplasm. However, these biopolymers are preferably accumulated under conditions of nitrogen limitation, a situation difficult to achieve in a co-culture as the other partner, at best, should not perceive any limitation. In this article, we will present an approach to overcome this dilemma by uncoupling the PHA production from the presence of nitrate in the medium. This is achieved by the construction of a P. putida strain that is no longer able to grow with nitrate as nitrogen source -is thus nitrate blind, and able to grow with sucrose as carbon source. The deletion of the nasT gene encoding the response regulator of the NasS/NasT two-component system resulted in such a strain that has lost the ability use nitrate, but growth with ammonium was not affected. Subsequently, the nasT deletion was implemented in P. putida cscRABY, an efficient sucrose consuming strain. This genetic engineering approach introduced an artificial unilateral nitrogen limitation in the co-cultivation process, and the amount of PHA produced from light and CO2 was 8.8 fold increased to 14.8% of its CDW compared to the nitrate consuming reference strain. This nitrate blind strain, P. putidaΔnasT attTn7:cscRABY, is not only a valuable partner in the co-cultivation but additionally enables the use of other nitrate containing substrates for medium-chain-length PHA production, like for example waste-water.

In times of global warming, extreme weather conditions, and a growing world population, it is mandatory to dedicate arable land to food production and not “waste” it for energy formation or feedstock production for biotechnology. Along that line, efforts are directed toward replacing traditional, crop-based feedstocks like sugarcane, corn, and wheat by carbohydrates derived from ecologically more friendly sources, for example eukaryotic algae or cyanobacteria. These sources of feedstock can be produced on non-arable land with salty or brackish water. Moreover, global warming is combatted at the same time as CO2 is captured in bio-chemical compounds. Unfortunately, the intrinsic capacities of photosynthetic microbes to produce interesting and tailored compounds are limited and efficiencies are low.

One approach to overcome this problem is to combine the phototrophic traits of the cyanobacteria with the biotechnological abilities of a heterotrophic organism. This can be done in a synthetic mixed culture, in which the cyanobacterium produces a substrate that is simultaneously metabolized by a heterotrophic co-culture partner (Ortiz-Marquez et al., 2013; Smith and Francis, 2016; Hays et al., 2017; Löwe et al., 2017). Along that line, a number of studies were published recently, that employed a genetically engineered Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 strain in a functional mixed culture (Hays and Ducat, 2015; Smith and Francis, 2016; Li et al., 2017; Löwe et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2017). This strain, S. elongatus cscB carries the sucrose/H+-symporter CscB from Escherichia coli integrated into the chromosome (Ducat et al., 2012). S. elongatus naturally responds to elevated salt concentrations in the environment with the accumulation of sucrose as compatible solute to counteract the osmotic pressure. Thus, when the engineered strain is grown at elevated salt concentrations, sucrose is produced and exported into the medium by the activity of CscB (Ducat et al., 2012). This sugar is then taken up and converted into a valuable product by the co-culture partner, which likewise needs to be able to grow with elevated salt concentrations. Many of the defined mixed cultures were set up to produce polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by the heterotrophic host (Hays and Ducat, 2015; Smith and Francis, 2016; Weiss et al., 2017). The highest productivity of 28.3 mg L–1 d–1 was reached in a mixed culture between S. elongatus PCC7942 cscB and Halomonas boliviensis, which compares well with PHB production by genetically engineered cyanobacteria strains (Weiss et al., 2017). We recently set up a co-cultivation for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) with S. elongatus PCC7942 cscB and the genetically engineered strain P. putida:mini-Tn5(cscAB), capable of metabolizing sucrose (Löwe et al., 2017). With this mixed culture approach a production rate of PHA of around 23.8 mg L–1 d–1 was reached under nitrogen limiting conditions. However, at the end of the process a major fraction of sucrose was left untouched by P. putida cscAB. To face this problem, we recently engineered a more efficient sucrose consuming strain, P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY, by the introduction of the gene cluster for sucrose metabolism from Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 (Löwe et al., 2020). This strain was able to grow on sucrose with growth rates comparable to the ones obtained with the monomers glucose and fructose. P. putida is a very suitable partner for co-cultivations as it combines various traits, including its genetic tractability and its general stress resistance (Nikel et al., 2016), which is of great importance when grown in the non-optimal environment of the photobioreactor with elevated salt concentrations.

Natural polymers like PHA that show thermoplastic, polypropylene-like properties, could be a valuable substitute for conventional petroleum-based plastic. Depending on the chain-length of the 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids, the polymers have different mechanical properties: Most bacteria produce short chain-length PHA (scl-PHA) which consist mainly of 3-hydroxybutyrate monomers and have limited mechanical properties (Wecker et al., 2015) as they tend to be brittle when not combined with other 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids (Muhammadi et al., 2015). Only a few genera can produce longer chain-length PHAs that are more interesting for applications due to their superior and more flexible properties (Jiang et al., 2012; Wecker et al., 2015; Fontaine et al., 2017). P. putida is one of these native producers of medium chain-length PHA (mcl-PHA), either from lipid based substrates or carbohydrates (Huijberts et al., 1992) in conditions of one or multiple nutrient starvation (Poblete-Castro et al., 2012). P. putida can accumulate around 20% of its cellular dry weight as PHAs in conditions of carbon surplus and nitrogen limitation (Huijberts et al., 1992; Poblete-Castro et al., 2014). However, this is a situation difficult to achieve in a co-culture, as the other partner –at best, should not perceive any limitation.

The common growth medium for S. elongatus is the BG-11 medium (ATCC Medium 616) for blue-green algae (Stanier et al., 1971), which provides nitrate as nitrogen source. The modified BG-11+ medium we adapted for the co-cultivation of S. elongatus and P. putida consequently also has nitrate as nitrogen source (Löwe et al., 2017). In bacteria the assimilation of nitrate takes place by the reduction of nitrate to nitrite and in a second step to ammonium by the activity of nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase. In P. putida the availability of nitrate or nitrite is detected by a two-component sensory system consisting of the sensor NasS and the response regulator NasT (Caballero et al., 2005; Luque-Almagro et al., 2013; Supplementary Figure S1). In the presence of nitrate or nitrite the sensory protein NasS (encoded by PP_2093) binds the substrate, dissociates from the stable complex with NasS and NasT (encoded by PP_2094) is released. The unbound NasT protein then activates transcription of the assimilating nitrate and nitrite reductases encoded by PP_1703 and nirBD (PP_1705, PP_1706), responsible for the reduction of nitrate to ammonium. Furthermore, it was shown that the transcription of nasT is highly induced right at the beginning of NH4+ deficiencies, suggesting that it forms part of the early response to ammonium depletion and helps the cell in preparing for the immediate consumption of the alternative nitrogen source nitrate (Mozejko-Ciesielska et al., 2017).

In this work, we will present a metabolic engineering approach to uncouple the PHA production by P. putida from the presence of nitrate in the medium. This is achieved by the development a “nitrate blind” mutant, which allows the introduction of an artificial unilateral nitrogen limitation in the co-cultivation process. This enabled us not only to increase the PHA produced from CO2 and light to 14.8% of the CDW compared to <1% in the reference strain, but additionally opens up the use of other nitrate containing substrates, like waste-water, for medium-chain-length PHA production with P. putida.

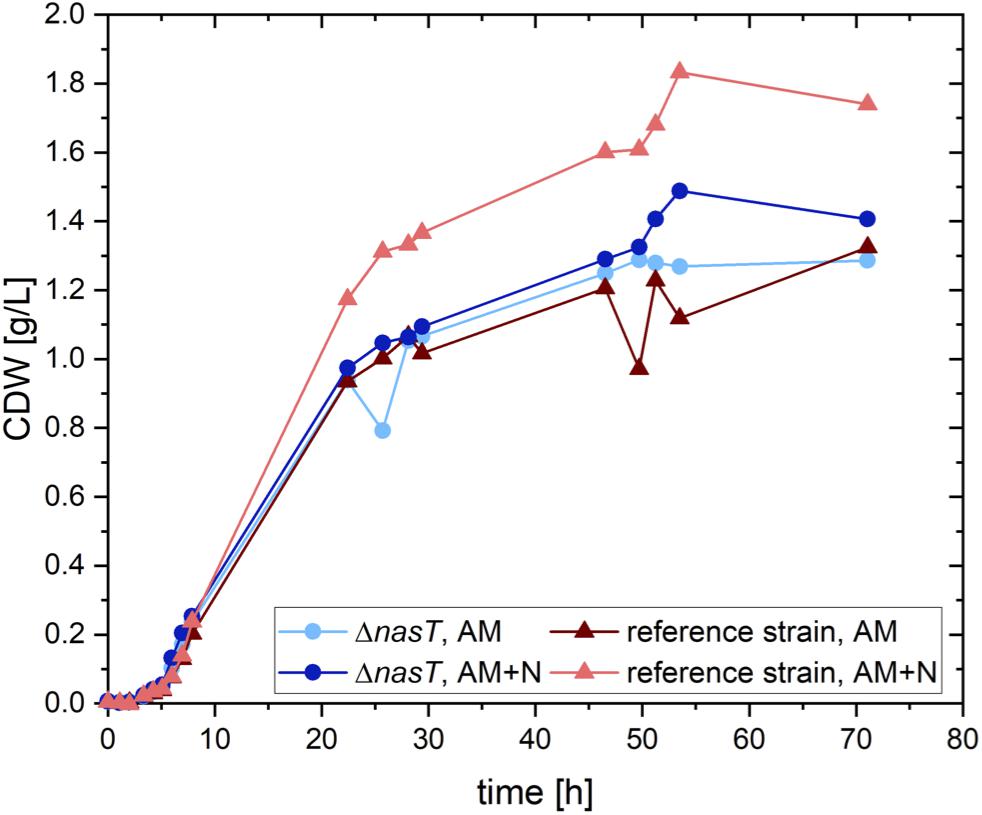

In order to uncouple the accumulation of PHA by P. putida from the presence of nitrate, we aimed to construct a nitrate-blind strain. As a target system we chose the nitrate/nitrite sensing two-component system NasS/NasT (Supplementary Figure S1). To this end, a clean deletion of nasT was introduced into P. putida EM178, a prophage free derivative of P. putida KT2440 by I-SceI aided double homologous recombination (Martínez-García and de Lorenzo, 2011). The resulting strain P. putida EM178 ΔnasT was no longer able to grow with nitrate as sole nitrogen source (Supplementary Figure S2). However, the growth with ammonium was not affected (Figure 1). Both strains showed a similar growth behavior in the presence of ammonium as sole nitrogen source and reached final cellular dry weights of around 1.3 g/L. To test whether the addition of nitrate, a situation found in the co-cultivation, has an effect on the recombinant strain P. putida EM178 ΔnasT, both strains were grown with ammonium and nitrate (see Supplementary Table S1). The recombinant strain P. putida EM178 ΔnasT showed a growth behavior comparable to the one observed in the absence of nitrate, indicating that the additional presence of nitrate had no negative effect on P. putida EM178 ΔnasT. The parental strain P. putida EM178, however, grew best in the presence of both nitrogen sources up to around 1.75 g/L CDW. The overall amount of nitrogen was increased 1.3 fold by the addition of nitrate, which generates a 1.35 fold increase in the final CDW reached by P. putida EM178. The growth rates were similar in all cases, ranging between 0.52 and 0.55 h–1 (Table 1). Thus, the ΔnasT strain grew comparably to the parental strain with ammonium as nitrogen source and was not influenced by the presence of nitrate, as it is unable to induce the nitrate assimilatory pathways. This effect of nasT disruption was already observed in the close relative Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Romeo et al., 2012).

Figure 1. Growth of P. putida EM178 ΔnasT with NH4Cl is not affected. Shown is the calculated cellular dry weight (CDW) for P. putida EM178 (red triangles) and P. putida EM178 ΔnasT (blue circles) grown on glucose in M9 minimal medium with either ammonium as sole nitrogen source (NH4Cl 0.22 g/L) or with a mixture of ammonium and nitrate (NH4Cl 0.22 g/L + NaNO3 0.10 g/L). The additional growth of P. putida EM178 compared to the other strains can be attributed to the nitrate in the medium available as nitrogen source for this strain, but not for P. putida EM178 ΔnasT. Shown are the results of one representative experiment.

However, to employ the nitrate-blind mutant strain in the co-cultivation, it has to be able to metabolize sucrose, a trait not intrinsically present in P. putida (Nogales et al., 2019). Therefore, the deletion of nasT was next introduced into the genetically engineered P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY, which is capable to grow on sucrose as sole carbon source (Löwe et al., 2020), yielding P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY ΔnasT. For the sake of simplicity, the strain P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY will from here on be referred to as “P. putida cscRABY” and P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY ΔnasT as “P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT” (see Supplementary Table S2 for more detail).

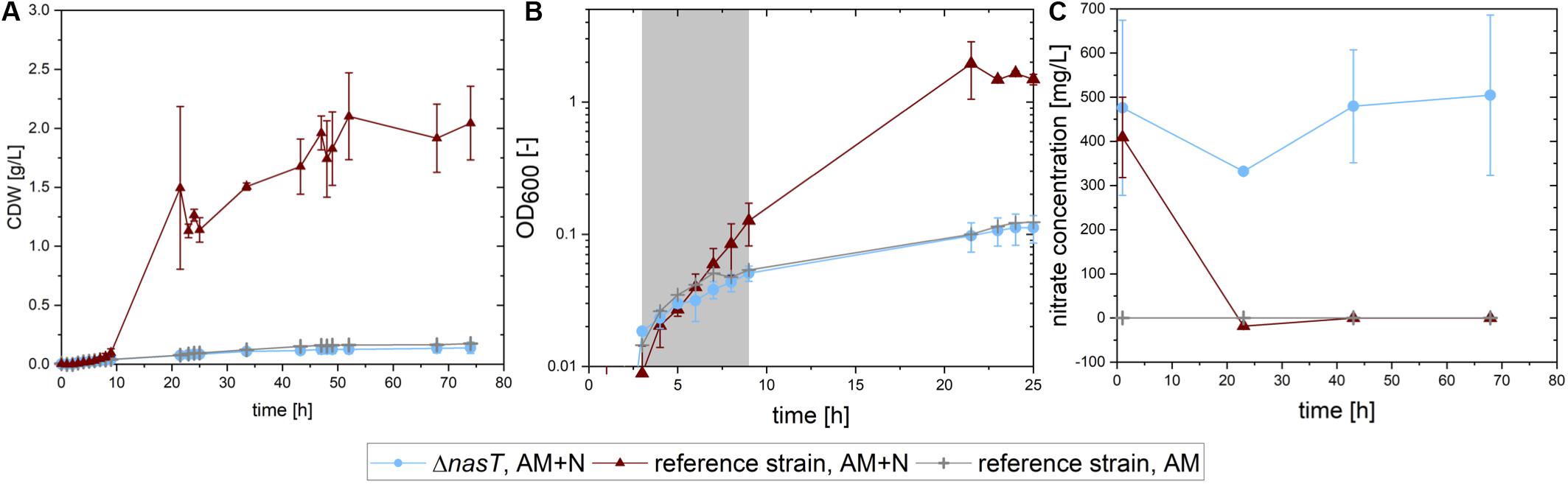

First, we analyzed the growth of both strains on sucrose with low ammonium concentrations and an excess of nitrate, to simulate the conditions in the co-cultivation. As control for the situation as it should be perceived by P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT, which can only grow on the ammonium present in the medium, P. putida cscRABY was grown solely with the low ammonium concentration. The growth rate, the biomass produced, and the nitrate consumed were compared (Figure 2). P. putida cscRABY grew to a CDW of 2.04 ± 0.313 g/L in the medium containing both nitrogen sources, whereas the nasT mutant, reached a biomass concentration of only about 0.14 g/L, even though nitrate was readily available (Figure 2C), corroborating the results from above. In fact, in the control experiment with P. putida cscRABY with ammonium only a similar CDW of about 0.18 g/L was reached.

Figure 2. Growth of P. putida cscRABY and P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT on sucrose. P. putida cscRABY (red triangles) and P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT (blue circles) were grown in M9 medium with low ammonium concentrations (AM = 0.03 g/L NH4Cl) and with or without the addition of nitrate (N = 1 g/L NaNO3) to simulate the conditions of the co-cultivation. (A) The development of the cellular dry weight (CDW) during the cultivation. CDW was calculated using an OD/CDW correlation (see Supplementary Figure S3). (B) The optical density measured at 600 nm along growth. The growth rate μ (see Table 2) was determined in the exponential growth phase (gray shaded area). (C) The nitrate concentration in the supernatant of the cultures.

This is also reflected in the growth rates (Figure 2B and Table 2): A similar growth rate was reached by the ΔnasT strain with both nitrogen sources and P. putida cscRABY grown on ammonium only. When P. putida cscRABY is grown with ammonium and nitrate, a higher growth rate is reached, a consequence of a simultaneous consumption of both nitrogen sources by the culture.

To confirm that P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT was no longer able to take up nitrate, the nitrate concentration was measured along growth (Figure 2C). P. putida cscRABY depleted nitrate in the first 20 h, whereas in the culture with P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT nitrate remained detectable for the time measured. Thus, the disruption of the two-component sensing system NasT/NasS by deletion of nasT in the sucrose consuming P. putida cscRABY generated a strain which is blind to nitrate in conditions resembling the situation found in the co-cultivation.

The next step was to test the potential of P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT in the co-culture with S. elongatus cscB to produce PHA from light and CO2. To provide proof of concept and to allow for parallel cultivations under comparable conditions, we performed the co-cultivation experiments in shaking flasks under constant illumination. All co-cultivations started with an exclusively auxotrophic growth phase of S. elongatus cscB for 3 days with solely nitrate as nitrogen source. Then the inoculation with P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT and simultaneous addition of ammonium took place. IPTG and elevated salt concentration were present from the beginning to induce sucrose production and excretion.

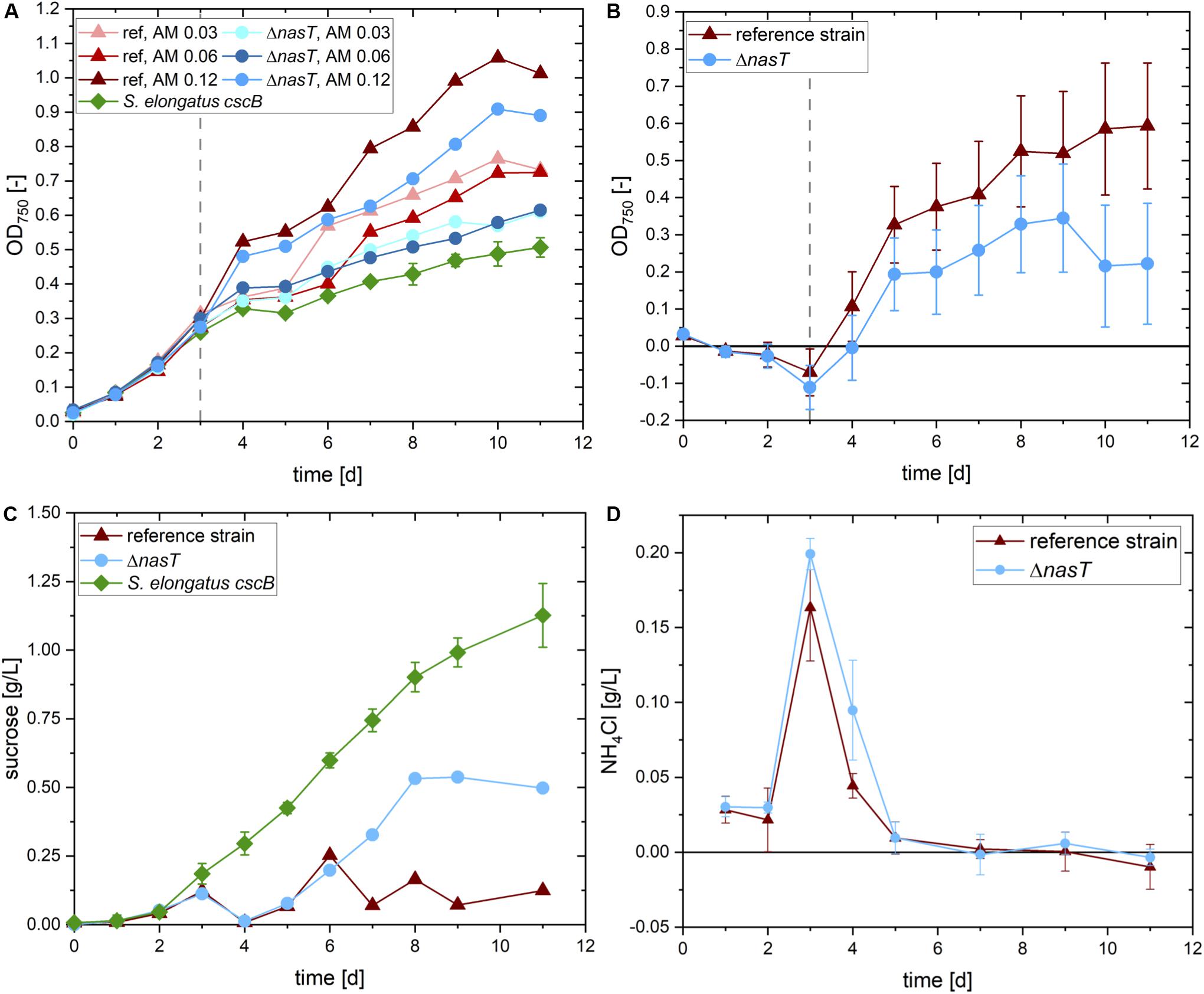

In a first round of experiments, we aimed to find the optimal ammonium concentration to allow for sufficient initial biomass formation of P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT. The availability of ammonium for P. putida cannot be predicted as it is likewise metabolized by S. elongatus cscB. An overview of the experimental setup is given in Supplementary Figure S4 and the results are depicted in Figure 3A. Three different ammonium concentrations were tested in the co-cultivation of S. elongatus cscB with both, P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT and as control with P. putida cscRABY. To get an estimation of the biomass and sucrose produced by S. elongatus cscB, this strain was also grown in mono-culture. In the first auxotrophic phase before the inoculation with the heterotrophic co-culture partner and the addition of different ammonium concentrations, all eight replicates of S. elongatus cscB showed a uniform behavior (Figure 3A). After inoculation with P. putida a clear difference in the optical density (OD) can be observed in the different setups. In every case, the addition of P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT and ammonium led to higher optical densities compared to the mono-cultures of S. elongatus cscB without ammonium. This can be explained by the introduction of additional cells, but also by the addition of ammonium, which promotes growth of the cyanobacterium as well. Comparing the co-cultivations with the ΔnasT mutant to the ones with P. putida cscRABY reveals, that in all cases a better overall growth is observed with P. putida cscRABY. As for this strain nitrate is available as nitrogen source, it reached higher optical densities that contribute to the total OD of the co-culture. A comparison of the development of the total OD with different ammonium concentrations in each of the co-cultivations revealed that no clear difference was observed with 0.03 g/L or 0.06 g/L NH4Cl, i.e., that although the ammonium concentration was doubled the total OD did not increase correspondingly. Therefore, it was assumed that theses concentrations were too low to allow for substantial growth of P. putida. The addition of 0.12 g/L NH4Cl, however, led to an increase in the overall OD, compared to the lower NH4Cl concentrations, suggesting that ammonium was available for growth of P. putida. Thus, this co-culture was analyzed in more detail.

Figure 3. Co-cultivation of S. elongatus cscB and P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT. (A) Total OD at 750 nm of the cultures with different ammonium concentrations. S. elongatus cscB (green diamonds) was grown in mono-culture as control. Co-cultivations were done with P. putida cscRABY (ref; triangles) or with P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT (ΔnasT; circles), AM 0.03: 0.03 g/L NH4Cl; AM 0.06: 0.06 g/L NH4Cl; AM 0.12: 0.12 g/L NH4Cl. (B) Estimated optical density of the P. putida fraction of the co-cultivations with 0.12 g/L ammonium of P. putida cscRABY (red triangles) and P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT (blue circles). (C) Sucrose present in the control cultivation with S. elongatus cscB alone (green squares), or the co-cultivations with 0.12 g/L ammonium with P. putida cscRABY reference strain (red triangles), or P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT (blue circles). (D) Development of the NH4Cl concentrations in the co-cultivations with 0.12 g/L ammonium with P. putida cscRABY reference strain (red triangles) or P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT (blue circles).

To get a rough estimation of the proportion of the OD achieved by P. putida cells, the signal stemming from P. putida was traced back using its different absorption characteristics (for details see Experimental Procedures and Supplementary Material). Therefore, a technique was applied similar to the fluorescence based “spectral unmixing” method described by Lichten et al. (2014). Instead of using variations in fluorescence intensity, here we used the different absorption characteristics of both bacteria. In particular, S. elongatus absorbs light via some pigments involved in photosynthesis, like chlorophyll and carotenoids, in a very different way than P. putida. By measuring at wavelengths that are specific and unspecific for each of the co-culture partners, information on the quantity of both can be obtained. This allowed us to calculate the proportion of P. putida of the total OD. The estimated optical densities reached by P. putida cscRABY or P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT are shown in Figure 3B. At all time points, the estimated OD of P. putida cscRABY exceeds the one estimated for the ΔnasT mutant. Furthermore, according to these estimations, P. putida cscRABY makes up a higher proportion of the overall OD than the ΔnasT strain, which can be explained by the competition with S. elongatus cscB for nitrate.

Every day the sucrose content of these cultivations was determined by means of HPLC (Figure 3C). S. elongatus cscB excreted sucrose into the medium at a rate of 0.14 ± 0.014 g/L d and a titer of 1.13 ± 0.117 g/L was reached after 11 days. To bring this into context, this is roughly half of what was obtained in the bioreactor, where the cells are optimally supplied with light and CO2 (Löwe et al., 2017). In both co-cultivations sucrose concentration decreased to the detection limit 1 h after the inoculation with the P. putida partner. However, whereas in the co-cultivation with P. putida cscRABY the sucrose concentration stayed on a low level throughout the experiment, it increased in the co-cultivation with the ΔnasT mutant strain to around 0.5 g/L of sucrose at the end of the experiment. This suggests that in the co-cultivation with P. putida cscRABY the sucrose produced by S. elongatus cscB is simultaneously taken up and metabolized by the heterotroph. In the co-cultivation with the ΔnasT mutant in contrast, the sucrose consumption pattern diverged from the one obtained with P. putida cscRABY from day six on. Measuring the NH4Cl concentration revealed that this is the time when NH4Cl becomes scarce and was no longer detectable from day seven on (Figure 3D). This suggests that the ΔnasT mutant stopped growing when ammonium was depleted. As a consequence, the ΔnasT mutant reduced the uptake of sucrose, whereas P. putida cscRABY continued to grow with nitrate as nitrogen source.

The plateau in the sucrose concentration reached at day eight might have different explanations on which only can be speculated. It could reflect the moment when cells switched to increased PHA accumulation which comes along with increased uptake of sucrose. However, it can also not be excluded that sucrose production by the cyanobacterium ceased for another reason. Nevertheless, the conditions from day seven on in the co-cultivation with P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT, where no nitrogen source is available for the heterotroph, but the carbon source is still present, should resemble a situation in which PHA accumulation is promoted.

The amount of PHA produced by the respective strain at the end of the co-cultivation experiment was determined. Indeed, P. putida cscRABY ΔnasT accumulated 25.24 mg/L PHA, which make up 14.8% of its calculated dry weight. In contrast, in P. putida cscRABY less than 1% of its calculated dry weight corresponded to PHAs (2.86 mg/L). Thus, deletion of nasT led to a 8.8 fold increase in the PHA accumulation in conditions in which nitrate is present. The distribution pattern of 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids is typical for P. putida (Supplementary Table S3), with 3-hydroxydecanoic acid being the most abundant monomer and does not differ substantially from the one usually obtained in P. putida and also reported in earlier co-cultivations in a photobioreactor (Poblete-Castro et al., 2014; Löwe et al., 2017).

Thus, by disruption of the nitrate sensing TCS, the PHA accumulation is uncoupled from the presence of nitrate in the medium. As a result, this strain experiences nitrogen limitation considerably earlier during the co-cultivation than P. putida cscRABY as it cannot sense nitrate and in consequence does not induce the assimilatory proteins. The lack of nitrogen assimilation should result in an internal decrease of glutamine, which triggers accumulation of the storage compound PHA. This strain is a promising candidate for PHA production from CO2 and light not only at larger scale, but also opens up the use of other nitrate containing substrates, like waste-water, for PHA production.

This co-culture setup combined two novel elements on the side of the heterotroph compared to the published co-cultivations: (i) the blindness to nitrate, which uncouples PHA accumulation from the availability of nitrate and allows us to run the fermentation under normal nitrogen conditions, and (ii) the higher efficiency of sucrose consumption of P. putida cscRABY (Löwe et al., 2020), which represents a clear advance in the co-culture platform for PHA production with P. putida.

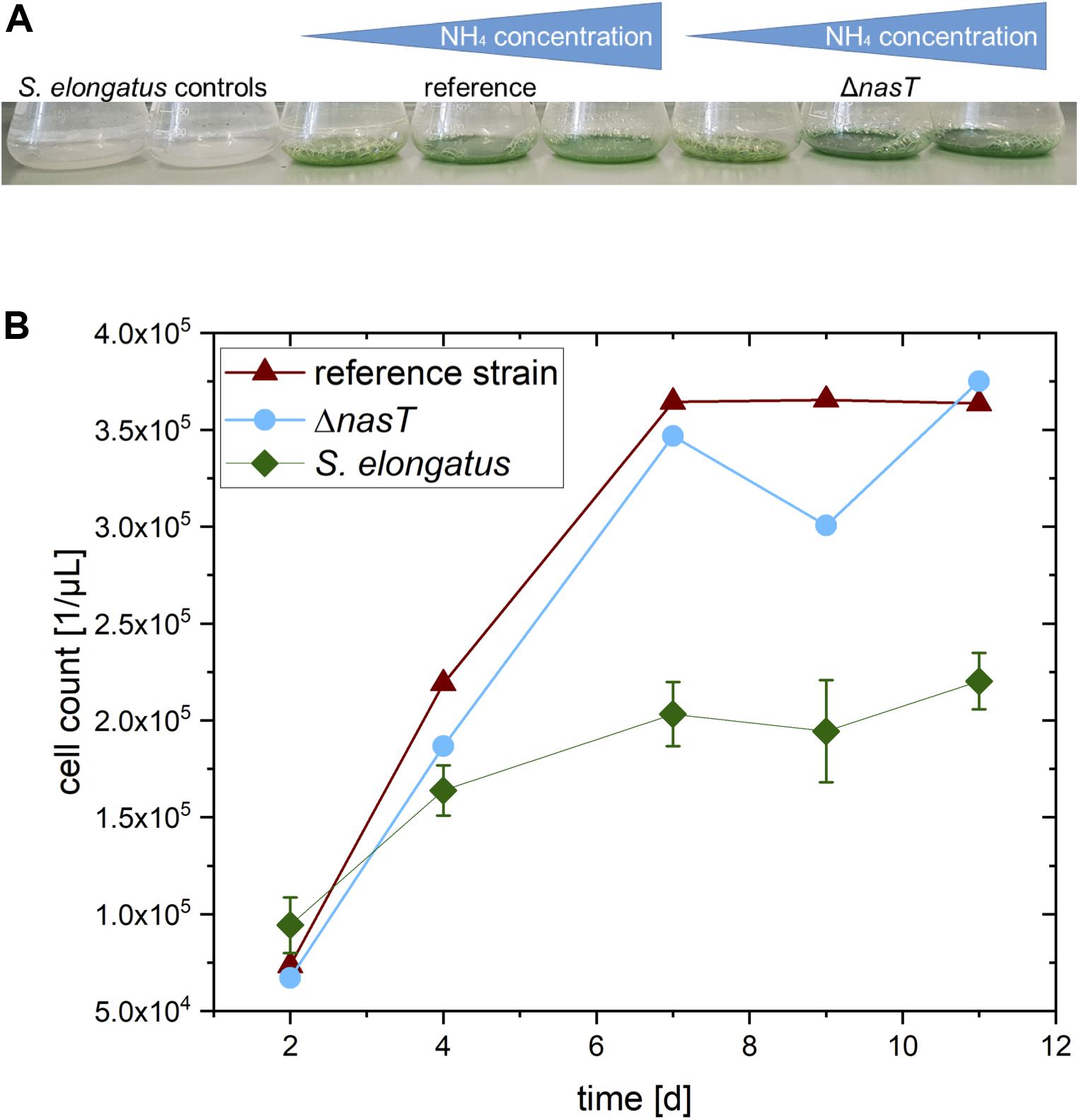

At the end of the co-cultivation experiment described above, we observed that the two S. elongatus monocultures started to lose the green pigmentation, whereas the co-cultures did not. This was even more pronounced 4 weeks after inoculation (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the intensity of the green color of the cultures increased with increasing ammonium concentration. The loss of pigmentation in cyanobacteria is known as chlorosis, a process that describes the depigmentation of cyanobacteria due to degradation of chlorophyll (Forchhammer and Schwarz, 2019). The fitness and viability of a cyanobacterial culture can be estimated from their chlorophyll content, which is reflected by the characteristic green color. When they are stressed or starved, they respond with chlorosis.

Figure 4. Stabilizing effect of the co-cultivation. (A) Color of the cultures 4 weeks after the end of the experiment. Note that the mono-cultures have experienced complete chlorosis, whereas the co-cultures are still green. (B) Number of S. elongatus cscB cells in the different setups: S. elongatus, control: S. elongatus cscB in mono-culture; reference strain: Co-cultivation of S. elongatus cscB with P. putida cscRABY reference strain; ΔnasT: Co-cultivation of S. elongatus cscB with P. putida ΔnasT.

This observation that the presence of P. putida seems to have a stabilizing effect on the cyanobacterium was strengthened by the development of the cyanobacterial cell number in the co-cultivation (Figure 4B). In the mono-cultures of S. elongatus cscB a final cell count of around 2.2 × 105 cells/μL was determined, whereas in the co-cultivation setups S. elongatus cscB reached over 3.6 × 105 cells/μL. This effect was independent of the specific P. putida strain. However, the exact reason for the chlorosis cannot be determined from the experiment. It might be the consequence of the presence of P. putida cells. Thus, it can be speculated that the depletion of oxygen by respiration of P. putida provides an advantage for the cyanobacteria. On the other hand, the effect can also be attributed to the addition of ammonium together with the inoculation of P. putida, which might provide an additional advantage for the cyanobacteria. Another possible positive effect on S. elongatus cscB might be the depletion of sucrose in the culture medium by the activity of P. putida. Nevertheless, any combination thereof is also possible and will be in the focus of another study in out laboratory.

The stabilizing effect of co-cultivations on one of the co-culture partners was not only observed by us, but has been previously reported also by other (Hays et al., 2017). Thus, co-cultivations do not only provide an advantage over mono-cultures due to the division of labor allowing for functions that are difficult to program in individual cells, but also might have an effect on the stability of the system.

Biopolymers like PHA are often accumulated in conditions of nutrient depletion, a situation which sometimes is difficult to achieve in a biotechnological application, or at least requires considerable efforts. Genetic engineering and process engineering open up ways to mimic limitations for the specific microbe, without interfering with the rest of the system. This allows not only to improve existing microbes in terms of their productivity, but may also lay the basis for the usage of novel, or less processed substrates.

Here, we reported that deletion of the nasT gene encoding the response regulator of the NasS/NasT two component system resulted in a strain insensitive to the presence of nitrate and unable to grow with nitrate as nitrogen source. Nevertheless, growth but with other nitrogen sources, like ammonium, remained unaffected. The introduction of this deletion into the sucrose consuming P. putida cscRABY created a strain very well suited as PHA producer strain in the co-cultivation with S. elongatus cscB. As in this strain the PHA accumulation was uncoupled from the presence of nitrate it was not necessary to apply a nitrate limitation on the co-cultivation to induce a regime in P. putida that allowed for accumulation of the polymer. The final PHA titer reached by this recombinant strain was about 9-fold higher than in P. putida cscRABY. However, these numbers are based on the snapshot at the end of the experiment. To quantify the improvement of this tailored strain, next we will determine the PHA production rate in an optimal environment, i.e., the photobioreactor, where controlled conditions can be ensured. Apart from being used as co-cultivation partner, this strain can also be used for mcl-PHA production from other feedstocks as nitrate containing waste and surplus material. The engineering strategy applied in this work represents an important step toward mcl-PHA production from carbohydrates, which have great potential as a source of sustainable bioplastics and for medical applications (Kniewel et al., 2019) as well as for the production of chiral 3-hydroxy fatty acids that themselves can serve as precursors for various high-value products (Lee et al., 1999).

Escherichia coli DH5αλ-pir was used for the extraction of plasmids, transformation and as the plasmid donor in conjugation. E. coli HB101 (pRK600) and E. coli DH5α (pTnS1) served as helpers in conjugation and Tn7 transposition, respectively. All P. putida strains used in this work are derived from P. putida EM178, a prophage-free derivative of P. putida KT2440 (created at Victor de Lorenzo’s lab at CNB, Madrid). An overview on the P. putida strains used in this work and how they are designated in the text is given in Supplementary Table S2. The organisms employed in the mixed culture are the autotrophic host, S. elongatus cscB (Ducat et al., 2012) and P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY ΔnasT, a derivative of P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY (Löwe et al., 2020), was constructed as described below.

Pseudomonas putida and E. coli strains were cultivated at 30°C or 37°C, respectively, in either LB or M9 mineral medium (Miller, 1974) with 2% [w/v] of either glucose for P. putida EM178 and P. putida EM178 ΔnasT, or sucrose for P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABY and P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABYΔnasT as carbon source.

Growth experiments with P. putida EM178 and P. putida EM178 ΔnasT in the presence or absence of nitrate were conducted in an ammonium-reduced M9 medium: 6.77 g/L Na2PO4, 2.99 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L NaCl, and 0.22 g/L NH4Cl with or without the addition of 0.01 g/L NaNO3.

Each experiment was performed in biological duplicates. The mean growth rates were calculated by performing a linear regression in the exponential phase (first 10 h frame) and averaging the slopes for both biological replicates. The given standard deviation refers to the error between biological replicates only since the error of the linear fit was found to be negligible.

For the characterization of the sucrose-metabolizing strain (P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABYΔnasT) the ratio between ammonium and nitrate was shifted toward a higher nitrate proportion to allow only for very little growth with ammonium (0.03 g/L NH4CL and 1 g/L mM NaNO3) and 10 μg/mL Gentamicin was added to select for the integrated sucrose operon. Additionally, the trace element solution A5 originally found in BG11 medium (ATCC Medium 616) was supplemented to avoid deficiency of inorganic cations during growth on nitrate. All cultivations were carried out in 250 mL shaking flasks with 10% filling volume in a shaking incubator at 220 rpm. The precultures were initially grown in LB medium followed by a M9 medium intermediate culture (0.5 g/L NH4Cl). Before inoculation of the main culture the inoculum was washed once in the cultivation medium to avoid transfer of ammonium from the preculture medium.

The co-cultivation was performed in the modified BG11+ medium described previously (Löwe et al., 2017) at 30°C and 120 min–1 rpm with 10% filling volume of 250 mL shaking flasks in the Multitron Pro incubator equipped with CO2 gassing and LED lighting (Infors). A photon flux density of 24 μmol m–2 s–1 was applied and air was used as the sole source of CO2. After inoculation with S. elongatus cscB an initial adaptation and auxotrophic growth phase of 3 days was allowed. Upon inoculation with P. putida various concentrations of NH4Cl were supplied in parallel: 0.03 g/L, 0.06 g/L, and 0.12 g/L to allow for initial growth of P. putida EM178 attTn7:cscRABYΔnasT before the PHA production phase begins. To the two control flasks without heterotrophic partner no ammonium was added. The S. elongatus cscB pre-cultures were grown in 100 mL shaking flasks with 40 mL BG11+ medium in the Multitron Pro incubator. The P. putida pre-cultures were initially grown in LB medium followed by a M9 medium intermediate culture. The main culture was inoculated with washed cells to eliminate carry over of nitrogen and carbon from the intermediate culture.

The gene deletion was carried out as described in Martínez-García and de Lorenzo (2011). All enzymes used were obtained from New England Biolabs (United States). The flanking regions upstream and downstream of nasT of 709 bp, respectively, were amplified by PCR (Q5 Polymerase). The primers used (Supplementary Table S4) for amplification introduced complementary overhangs allowing to join both fragments by overlap extension PCR (Q5 Polymerase), as well as restriction sites for the enzymes EcoRI and HindIII. Thus, after joining, the gene fragment was inserted into the suicide vector pSEVA212S (Silva-Rocha et al., 2013) by restriction digest and ligation (T4 DNA Ligase) to create the integration vector pSEVA212S-ΔnasT. This suicide vector was transferred to P. putida EM178 attTn:cscRABY by triparental mating with E. coli HB101 (pRK600) as helper and co-integrates were selected by plating on LB with 50 mg/ml Kanamycin (de Lorenzo and Timmis, 1994). The integration was confirmed by PCR (oneTaq Polymerase) with the primers fwP_nasT_orient and rvP_nasT_seq (Supplementary Table S4), which also allowed to determine the site of the homologous recombination. Subsequently, the helper plasmid pSW-I was transferred by triparental mating with E. coli DH5α (pTnS1) as donor and one clone with the integrated pSEVA212S-ΔnasT as receptor. Expression of the I-SceI endonuclease was induced with 1 mM 3-methylbenzoic acid for 4 h in a stationary culture (Martínez-García and de Lorenzo, 2011). Subsequently, different dilutions were plated on M9 solid medium with citrate as C-source (0.2% w/v), incubated at 30°C and single-colonies were examined by PCR (oneTaq Polymerase) and the correct deletion was confirmed by complete sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg) of the flanking regions.

Growth of the P. putida cultures was followed by measuring the OD at 600 nm in a 96-well plate in the Infinite 2000 TECAN plate reader. In the case of co-cultivation with S. elongatus cscB, growth was followed likewise, but at 750 nm. The dry weight was approximated using an OD to dry weight correlation determined previously for the common parental strain P. putida EM178 (see Supplementary Figure S3).

The nitrate/nitrite concentration of culture supernatants was determined using a colorimetric assay (Nitrite/Nitrate colorimetric method, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany) in a microplate reader based on the enzymatic reduction of nitrate to nitrite.

The ammonium concentration was determined with the Ammonia Assay (Cat. No. 11 112 732 035, Boehringer Manheim/R-Biopharm) according to the supplier’s manual.

The sucrose concentrations were measured using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) via a Shodex SH1011 column and the PHA content was determined by gas chromatography (GC) from 2 ml of the culture, exactly as described in Löwe et al. (2017).

For the cell count measurements, a 400 μL sample of the co-culture was centrifuged for 5 min at 12000 g. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 400 μL PBS and Nile-red resuspended in DMSO was added to a final concentration of 3.1 μg/mL. After an incubation period of 30 min at room temperature the sample was centrifuged and washed in PBS again and a 1:100 dilution was measured in the Cytoflow Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Cells were excited by a 488 nm laser and S. elongatus cscB could be identified by red fluorescence that is lacking in P. putida.

The OD at 750 nm measured during the experiments is a sum of the ODs of both species.

For the differentiation between the OD of S. elongatus and P. putida, a technique was applied similar to the fluorescence based “spectral unmixing” method described by Lichten et al. (2014). Instead of using variations in fluorescence intensity, here we used the different absorption characteristics of both bacteria. As a photosynthetic organism, S. elongatus has a variety of fluorescent pigments like chlorophylls and carotenoids that strongly absorb in certain wavelength regions. In particular, we used the absorption at the wavelengths at 442 nm and 632 nm, both of which should be highly influenced by chlorophyll absorption. Control experiments with pure cultures indicated that the absorption at both wavelengths show a constant linear correlation with different correlation factors (see Supplementary Figure S5):

where m632/442 is the correlation factor of the two absorption-values which depends on the bacterial strain.

This can be used to estimate the proportions of different bacterial species which will be shown in the following equations. First, both P. putida and S. elongatus contribute toOD632:

Likewise, OD442is also the sum of individual absorptions of the two species:

Having two equations with two variables (OD442, P. putidaand OD442, S. elongatus), we can solve for the single variables:

Since OD442, P. putida also correlates linearly with OD750, P. putida (see Supplementary Figure S6), the proportion of P. putida can easily be calculated from the OD at 442 nm:

In total, absorption measurements at three different wavelengths are necessary to calculate these values when the correlation-factors mi/j are known. The errors of the calculated, final OD750- values are therefore influenced not only by the errors of the correlation-factor mi/j, but also by the error of measurement of three ODs. We calculated the errors accordingly with Gaussian propagation of uncertainty, assuming a combined handling and instrument error of 2%.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

KH and HL conceived and planned the experiments. KH, SL, and HL carried out the experiments. KP-G wrote the manuscript with the help of HL and KH. KP-G and AK supervised the project with the help of HL. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We gratefully thank Victor de Lorenzo, CNB, Spain, and his laboratory for access to the pSEVA plasmid collection and the genetically streamlined versions of P. putida KT2440 and the group of Thomas Bruück, Technical University of Munich, especially Martina Haack for help with the GC analytics.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00486/full#supplementary-material

Caballero, A., Esteve-Núñez, A., Zylstra, G. J., and Ramos, J. L. (2005). Assimilation of nitrogen from nitrite and trinitrotoluene in Pseudomonas putida JLR11. J. Bacteriol. 187, 396–399. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.396-399.2005

de Lorenzo, V., and Timmis, K. (1994). Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235, 386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0

Ducat, D. C., Avelar-Rivas, J. A., Way, J. C., and Silver, P. A. (2012). Rerouting carbon flux to enhance photosynthetic productivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2660–2668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07901-11

Fontaine, P., Mosrati, R., and Corroler, D. (2017). Medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida mt-2 is enhanced by co-metabolism of glycerol/octanoate or fatty acids mixtures. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 98, 430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.115

Forchhammer, K., and Schwarz, R. (2019). Nitrogen chlorosis in unicellular cyanobacteria – a developmental program for surviving nitrogen deprivation. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 1173–1184. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14447

Hays, S. G., and Ducat, D. C. (2015). Engineering cyanobacteria as photosynthetic feedstock factories. Photosyn. Res. 123, 285–295. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9980-0

Hays, S. G., Yan, L. L. W., Silver, P. A., and Ducat, D. C. (2017). Synthetic photosynthetic consortia define interactions leading to robustness and photoproduction. J. Biol. Eng. 11:4. doi: 10.1186/s13036-017-0048-5

Huijberts, G. N., Eggink, G., de Waard, P., Huisman, G. W., and Witholt, B. (1992). Pseudomonas putida KT2442 cultivated on glucose accumulates poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) consisting of saturated and unsaturated monomers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 536–544.

Jiang, X., Sun, Z., Marchessault, R. H., Ramsay, J. A., and Ramsay, B. A. (2012). Biosynthesis and properties of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates with enriched content of the dominant monomer. Biomacromolecules 13, 2926–2932. doi: 10.1021/bm3009507

Kniewel, R., Lopez, O. R., and Prieto, M. A. (2019). “Biogenesis of Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates,” in Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, ed. O. Geiger (Cham: Springer).

Lee, S. Y., Lee, Y., and Wang, F. (1999). Chiral compounds from bacterial polyesters: sugars to plastics to fine chemicals. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 65, 363–368. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19991105)65:3<363::aid-bit15>3.0.co;2-1

Li, T., Li, C.-T., Butler, K., Hays, S. G., Guarnieri, M. T., Oyler, G. A., et al. (2017). Mimicking lichens: incorporation of yeast strains together with sucrose-secreting cyanobacteria improves survival, growth, ROS removal, and lipid production in a stable mutualistic co-culture production platform. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:55. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0736-x

Lichten, C. A., White, R., Clark, I. B. N., and Swain, P. S. (2014). Unmixing of fluorescence spectra to resolve quantitative time-series measurements of gene expression in plate readers. BMC Biotechnol. 14:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-11

Löwe, H., Hobmeier, K., Moos, M., Kremling, A., and Pflüger-Grau, K. (2017). Photoautotrophic production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in a synthetic mixed culture of Synechococcus elongatus cscB and Pseudomonas putida cscAB. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:190. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0875-0

Löwe, H., Sinner, P., Kremling, A., and Pflüger-Grau, K. (2020). Engineering sucrose metabolism in Pseudomonas putida highlights the importance of porins. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 97–106. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13283

Luque-Almagro, V. M., Lyall, V. J., Ferguson, S. J., Roldán, M. D., Richardson, D. J., and Gates, A. J. (2013). Nitrogen oxyanion-dependent dissociation of a two-component complex that regulates bacterial nitrate assimilation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 29692–29702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.459032

Martínez-García, E., and de Lorenzo, V. (2011). Engineering multiple genomic deletions in Gram-negative bacteria: analysis of the multi-resistant antibiotic profile of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 2702–2716. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02538.x

Miller, J. H. (1974). Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: CHS Laboratory Press.

Mozejko-Ciesielska, J., Dabrowska, D., Szalewska-Palasz, A., and Ciesielski, S. (2017). Medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis by Pseudomonas putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant: bioprocess characterization and transcriptome analysis. AMB Express 7:92. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0396-z

Muhammadi, Shabina, Afzal, M., and Hameed, S. (2015). Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates-eco-friendly next generation plastic: production, biocompatibility, biodegradation, physical properties and applications. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 8, 56–77. doi: 10.1080/17518253.2015.1109715

Nikel, P. I., Chavarría, M., Danchin, A., and de Lorenzo, V. (2016). From dirt to industrial applications: Pseudomonas putida as a synthetic biology chassis for hosting harsh biochemical reactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 34, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.011

Nogales, J., Mueller, J., Gudmundsson, S., Canalejo, F. J., Duque, E., Monk, J., et al. (2019). High-quality genome-scale metabolic modelling of Pseudomonas putida highlights its broad metabolic capabilities. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 255–269. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14843

Ortiz-Marquez, J. C. F., Do Nascimento, M., Zehr, J. P., and Curatti, L. (2013). Genetic engineering of multispecies microbial cell factories as an alternative for bioenergy production. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.05.006

Poblete-Castro, I., Escapa, I. F., Jäger, C., Puchalka, J., Lam, C. M. C., Schomburg, D., et al. (2012). The metabolic response of P. putida KT2442 producing high levels of polyhydroxyalkanoate under single- and multiple-nutrient-limited growth: highlights from a multi-level omics approach. Microb. Cell Fact. 11:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-34

Poblete-Castro, I., Rodriguez, A. L., Lam, C. M. C., and Kessler, W. (2014). Improved production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in glucose-based fed-batch cultivations of metabolically engineered Pseudomonas putida strains. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 59–69. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1308.08052

Romeo, A., Sonnleitner, E., Sorger-Domenigg, T., Nakano, M., Eisenhaber, B., and Bläsi, U. (2012). Transcriptional regulation of nitrate assimilation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa occurs via transcriptional antitermination within the nirBD-PA1779-cobA operon. Microbiology 158, 1543–1552. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.053850-0

Silva-Rocha, R., Martínez-García, E., Calles, B., Chavarría, M., Arce-Rodríguez, A., Las Heras de, A., et al. (2013). The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D666–D675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1119

Smith, M. J., and Francis, M. B. (2016). A designed A. vinelandii–S. elongatus coculture for chemical photoproduction from air, water, phosphate, and trace metals. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 955–961. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00107

Stanier, R. Y., Kunisawa, R., Mandel, M., and Cohen-Bazire, G. (1971). Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 35, 171–205.

Wecker, P., Moppert, X., Simon-Colin, C., Costa, B., and Berteaux-Lecellier, V. (2015). Discovery of a mcl-PHA with unexpected biotechnical properties: the marine environment of French Polynesia as a source for PHA-producing bacteria. AMB Express 5:74. doi: 10.1186/s13568-015-0163-y

Keywords: Pseudomonas putida, genetic engineering, polyhydroxyalkanoates, co-cultivation, artificial nitrogen limitation

Citation: Hobmeier K, Löwe H, Liefeldt S, Kremling A and Pflüger-Grau K (2020) A Nitrate-Blind P. putida Strain Boosts PHA Production in a Synthetic Mixed Culture. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:486. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00486

Received: 06 December 2019; Accepted: 27 April 2020;

Published: 25 May 2020.

Edited by:

Ignacio Poblete-Castro, Andres Bello University, ChileReviewed by:

Tanja Narancic, University College Dublin, IrelandCopyright © 2020 Hobmeier, Löwe, Liefeldt, Kremling and Pflüger-Grau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina Pflüger-Grau, ay5wZmx1ZWdlci1ncmF1QHR1bS5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.