94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 19 May 2020

Sec. Bioprocess Engineering

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00457

Valeria Agostino1†

Valeria Agostino1† Annika Lenic1

Annika Lenic1 Bettina Bardl2

Bettina Bardl2 Valentina Rizzotto3

Valentina Rizzotto3 An N. T. Phan1

An N. T. Phan1 Lars M. Blank1

Lars M. Blank1 Miriam A. Rosenbaum2,4*

Miriam A. Rosenbaum2,4*Electroautotrophy is a novel and fascinating microbial metabolism, with tremendous potential for CO2 storage and valorization into chemicals and materials made thereof. Research attention has been devoted toward the characterization of acetogenic and methanogenic electroautotrophs. In contrast, here we characterize the electrophysiology of a sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfosporosinus orientis, harboring the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway and, thus, capable of fixing CO2 into acetyl-CoA. For most electroautotrophs the mode of electron uptake is still not fully clarified. Our electrochemical experiments at different polarization conditions and Fe0 corrosion tests point to a H2- mediated electron uptake ability of this strain. This observation is in line with the lack of outer membrane and periplasmic multi-heme c-type cytochromes in this bacterium. Maximum planktonic biomass production and a maximum sulfate reduction rate of 2 ± 0.4 mM day–1 were obtained with an applied cathode potential of −900 mV vs. Ag/AgCl, resulting in an electron recovery in sulfate reduction of 37 ± 1.4%. Anaerobic sulfate respiration is more thermodynamically favorable than acetogenesis. Nevertheless, D. orientis strains adapted to sulfate-limiting conditions, could be tuned to electrosynthetic production of up to 8 mM of acetate, which compares well with other electroacetogens. The yield per biomass was very similar to H2/CO2 based acetogenesis. Acetate bioelectrosynthesis was confirmed through stable isotope labeling experiments with Na-H13CO3. Our results highlight a great influence of the CO2 feeding strategy and start-up H2 level in the catholyte on planktonic biomass growth and acetate production. In serum bottles experiments, D. orientis also generated butyrate, which makes D. orientis even more attractive for bioelectrosynthesis application. A further optimization of these physiological pathways is needed to obtain electrosynthetic butyrate production in D. orientis biocathodes. This study expands the diversity of facultative autotrophs able to perform H2-mediated extracellular electron uptake in Bioelectrochemical Systems (BES). We characterized a sulfate-reducing and acetogenic bacterium, D. orientis, able to naturally produce acetate and butyrate from CO2 and H2. For any future bioprocess, the exploitation of planktonic growing electroautotrophs with H2-mediated electron uptake would allow for a better use of the entire liquid volume of the cathodic reactor and, thus, higher productivities and product yields from CO2-rich waste gas streams.

Microbial Electrochemical Technologies (MET) represent an innovative biotechnological solution for CO2-valorisation and surplus electricity storage (Zhang and Tremblay, 2018). In reductive bioelectrochemical processes electrical energy is used to accomplish cathodic fixation of CO2-rich gas streams into valuable products (Bajracharya et al., 2017). This Microbial Electrosynthesis (MES) is based on the special metabolic ability of electroautotrophic microorganisms: they acquire energy by taking up electrons directly or indirectly from electrodes, while using CO2 as inorganic carbon source and terminal electron acceptor (Nevin et al., 2010).

In the last decade, several acetogens (e.g., Sporomusa ovata, Clostridium ljungdahlii, Morella thermoacetica, and others), methanogens (Methanococcus maripaludis, Methanobacterium IM1, and others) and photoautotrophic iron oxidizers (Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1), which all harbor this peculiar metabolic feature, have been discovered and characterized (Aryal et al., 2017; Karthikeyan et al., 2019; Rowe et al., 2019). However, electroautotrophy is still widely considered a black box, since the molecular mechanisms beyond this extracellular electron uptake are not completely understood and elucidated for the different cathodically active microorganisms. In anodophilic electroactive species like Geobacter and Shewanella, a direct extracellular electron transfer occurs via c-type outer membrane multiheme cytochromes (c-OMCs) and conductive nanowires (Pentassuglia et al., 2018). To the best of our knowledge, up-to now, c-OMCs or similar proteins have not been characterized in the acetogenic genera Clostridium, Sporomusa, and Moorella. The oxidative pathway of acetogens is rather based on the cytoplasmatic electron-bifurcating [FeFe] hydrogenase complex, that coupled Ferrodoxin and NAD(P) reduction with H2 oxidation. These bifurcating-hydrogenases contribute to the energy conservation pathway of aceteogens, providing reduced Ferrodixin for the Rnf complex or the Ech complex, in which exergonic electron flow is coupled to vectorial ion transport out of the cell. This chemiosmotic gradient is harnessed then by the ATP synthase for ATP production (Buckel and Thauer, 2018). Consequently, a H2-mediated electron uptake via hydrogenases is envisaged for the majority of acetogens in BES. In a cathodic environment, hydrogen availability might be strongly enhanced because it is in situ produced as chemically dissolved H2 (i.e., does not have to be dissolved from a bulk gas phase) and can be utilized before it comes out of solution. This raises the hypothesis that every hydrogenotrophic acetogens would be able to grow at H2-evolving cathodes and perform electrosynthesis. However, the capacity of oxidizing H2 for the reduction of CO2 via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is not exclusively sufficient for an acetogenic species to be able to drive MES (Aryal et al., 2017). The work of Aryal et al. (2017) screened different hydrogenotrophic Sporomusa species for acetate production in H2CO2 fermentation flasks and in H2-evolving cathodes. The results showed that not all species were able to perform MES and that a more efficient metabolism in H2CO2-fed flasks does not necessarily translate into better electrosynthetic performance (Aryal et al., 2017).

Different is the situation for extracellular electron uptake in methanogenic biocatalysts, since some of them (Methanosarcinales) harbor not only hydrogenases but also c-OMCs (Yee and Rotaru, 2020). Very recently, a hydrogensase-independent but cell-associated electron uptake feature was reported for Methanosarcina barkeri (Rowe et al., 2019). However, in another Methanosarcinales member (Methanosarcina mazei), the inactivation of c-OMCs did not impact its ability to retrieve extracellular electrons from an electrode (Yee and Rotaru, 2020).

Beyond acetogens and methanogens, other groups of prokaryotes, including iron-reducing bacteria, nitrate-reducing bacteria, and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) have shown electroautotrophic ability, while using terminal acceptors different than CO2 for their respiration (e.g., heavy metals, nitrate, sulfate) (Logan et al., 2019). Consequently, electroautotrophs can be exploited not only for MES, but also for bioremediation applications.

As we recently reviewed, autotrophic SRB-based biocathodes represent a very promising strategy for sustainable biotechnological productions and environmental engineering strategies (Agostino and Rosenbaum, 2018). However, the electrophysiology of these biocatalysts is still quite unexplored. The most well studied electroautotrophic SRB is the Fe0-corroding gram negative Deltaproteobacterium Desulfopila corrodens strain IS4, able to both perform bioelectrochemical sulfate reduction and H2 production (Beese-Vasbender et al., 2015; Deutzmann and Spormann, 2017). Zaybak et al. (2018) have recently discovered electroautotrophy and electrosynthetic acetate production in another gram negative sulfate-reducing Deltaproteobacterium, Desulfobacterium autotrophicum HRM2, able to fix CO2 through the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway.

In a screening for new electroautotrophic candidates, we have identified four possible electroautotrophs: two sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, Thiobacillus denitrificans and Sulfurimonas denitrificans, and two SRB, Desulfosporosinus orientis and Desulfovibrio piger (deCamposRodrigues and Rosenbaum, 2014). Among them, D. orientis was the best performing strain in terms of current consumption. Furthermore, D. orientis possesses interesting metabolic features and its genome is fully sequenced and annotated (Pester et al., 2012). It was isolated from Singapore’s soil in 1959, is strictly anaerobic, and belongs to the Clostridia class (even if it stains gram negative) (Adams and Postgate, 1959; Campbell and Postgate, 1965). It is able to grow chemolithoautotrophically on CO or CO2 and H2 plus sulfate, sulfite and thiosulfate, employing the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (Klemps et al., 1985; Cypionka and Pfennig, 1986). During electron acceptor limitation conditions, it produces acetate and small amount of butyrate (Cypionka and Pfennig, 1986). Furthermore, it can utilize a wide array of organic carbon sources, ranging from short and medium chain fatty acids to alcohols and aromatic compounds (Klemps et al., 1985; Robertson et al., 2001).

Consequently, we decided to deeper characterize the electrophysiology of D. orientis. To possibly understand the mechanisms of extracellular electron uptake (EEU), we studied D. orientis’ electroactivity at different applied cathodic potentials (Ecath) and its ability of using metallic iron (Fe0) as extracellular electron donor. We evaluated its bioelectrochemical sulfate removal performances under different polarization conditions. Finally, we investigated D. orientis’ capacity for acetate bioelectrosynthesis. To this aim, Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) in sulfate-limiting conditions was employed to push the microbial pathways to acetate production.

Desulfosporosinus orientis DSMZ 765 was purchased from the Deutsche Sammlung Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ). D. orientis was routinely maintained in 50 mL DSMZ 63 medium modified as follow (per liter): NH4Cl 1.0 g, CaCl2 × 2H2O 0.1 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, MgSO4 × 7H2O 0.3 g, Na2SO4 2.6 g, D-sodium lactate 5.6 g, yeast extract 1.0 g, resazurin 0.5 mg, L-cysteine-hydrochloride 0.5 g or 0.3 g, NaHCO3 1 g, vitamin solution #141 DSMZ 5.0 ml and trace solution SL-6 plus iron (0.3 g/L stock) 5 mL (deCamposRodrigues and Rosenbaum, 2014). Heterotrophic cultivation was performed in 250 mL serum bottles (Diagonal GmbH & Co KG, Münster, Germany) with N2 atmosphere, statically incubated at 30°C. Autotrophic cultivation of D. orientis was performed in 650 mL serum bottles (Gerresheimer, Düsseldorf, Germany) with 50 mL modified DSMZ 63 medium (without lactate and yeast extract) and H2:CO2 (80:20) atmosphere (1 atm). The serum bottles were incubated at 30°C horizontally in order to increase the gas-liquid contact surface for a better gas solubilization.

Corrosion experiments were performed in 650 mL serum bottles with 50 mL of modified DSMZ 63 medium (without cysteine, lactate and yeast extract), 5 g of Fe0 granules (1–2 mm-99.98%, Alfa Aesar, Germany) and N2/CO2 (80:20) atmosphere (1 atm). The experiments were inoculated with D. orientis pre-culture adapted to autotrophic growth without cysteine (10% v/v). Two abiotic controls with and without the addition of 18 mM of Na-sulfide and a biotic control without Fe0 were performed. In addition, normal autotrophic growth with H2/CO2 (80:20) was monitored. All experiments were performed in triplicate and statically incubated horizontally at 30°C. Samples were collected every 3 days for H2 headspace analysis, acetate and sulfate quantification.

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution experiments were performed in the two different sulfate-limiting conditions: 50 and 25% of the optimal sulfate concentration of modified DSMZ 63 medium (18.2 mM), corresponding to 9.1 mM and 4.6 mM, respectively. The ALE experiments were completed after a period of 6 months, for a total of 18 culture transfers. The experiments were performed in 650 mL serum bottles with a H2:CO2 (80:20) atmosphere using 3.2 mM cysteine for the first four culture transfers and then 1.9 mM cysteine. 10%v/v of stationary phase cultures were used as inoculum for the culture transfers. The performances of the 3rd and 17th culture transfer were characterized in triplicates using late-exponential phase cultures as inoculum.

Bioelectrochemical systems experiments were performed in bench-top double chambers H-type reactors, separated by a cation exchange membrane (CMI-7000S, Membranes International, United States) and containing 400 mL working liquid volume (Supplementary Figure S1B). All BES experiments were performed in 3-electrode configuration, applying a fixed cathodic potential or current through the use of a multi-channel VMP3 potentiostat (BioLogic). Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) were recorded from −300 mV to −1000 mV vs. Ag/AgCl(sat. KCl), at 2 mV s–1 scan rate. Measurements were performed in biotic (end of the test) and abiotic conditions (before inoculation). EDM-3 graphite electrodes (Novotec GmbH, Germany) were used, with a rectangular shaped anode (counter electrode, area 41.6 cm2) and a comb shaped cathode (working electrode, area 156.5 cm2). The reference electrode [Ag/AgCl(sat. KCl)] was placed in the cathodic chamber and all potentials are reported against this reference.

Both chambers were filled with modified DSMZ 63 medium (without lactate and yeast extract). After overnight flushing of the reactors with N2, Na-bicarbonate and vitamin solution from anaerobic stock solutions were added. In case of labeling experiment, Na-H13CO3 was used. The final electrolyte pH was in the range of 6.8–7. The gas feeding of both chambers was switched to a mixture of N2:CO2 (80:20) at a flow rate of 50 ml min–1 (or 15 mL min–1 during labeling experiments), before inoculation. In the cathodic chamber, the N2:CO2 (80:20) feeding served as carbon source, while in the anodic chamber it aimed to sparge out the likely abiotically formed oxygen and prevent membrane cross over to the cathode chamber.

All reactor experiments were inoculated with late exponential phase autotrophic pre-cultures (10% volume of the catholyte). The catholyte was agitated at 200 rpm with a magnetic stir bar and the temperature was controlled at 30°C with an integrated water jacket and the use of a recirculation water bath (Julabo Paratherm U1M, Julabo GmbH, Seelbach, Germany).

For a global overview of the distribution of the ingoing and outcoming charges (Q) in D. orientis’ biocathodes, the charge balance was calculated according to the following equation:

Faraday’s law (Q = z × n × F; with z, number of electrons per molecule; n, moles; F, Faraday constant) was used to calculate the charge input in the cysteine and the charge recovered in sulfate reduction, biomass production and organic acids production. The charge input provided by the cathodic current was calculated via the integral of the recorded current over time.

Prior to SEM imaging, pieces of the graphite electrode were broken off and washed in distilled sterile water and fixed in a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, at 4°C overnight. Then the samples were dehydrated by an ethanol series and dried with hexamethyldisilazane (HDMS) (Margaria et al., 2017). The fixed samples were sputtered with a 20 nm gold layer and examined with a SEM at 5–10 kV on a Zeiss DSM 982 Gemini microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Quantification of organic acids and sulfate was performed by HPLC using a Beckman System Gold 126 Solvent Module coupled with a System Gold 166 UV-detector (Gold HPLC System, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States) at 210 and 280 nm, respectively. For organic acids, the column (Metab AAC, ISERA GmbH, Düren, Germany) was eluted isocratically with 5 mM H2SO4 at flow rate of 0.6 mL min–1 and an oven temperature of 40°C. Prior to every measurement, the supernatant samples were centrifuged (Heraus Pico17 microCentrifuge, Thermo Scientific, Germany) for 5 min at 13000 rpm and transferred to HPLC vials. Sulfate quantification was performed with a NUCLEOSIL® Anion II column (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) packed with NUCLEOSIL® silica gel base material, particle size 10 micron, pore size 300 Å and strongly basic anion exchange capacity of 50 μeq/g. The column was eluted isocratically with 2 mM potassium hydrogen phthalate (pH 5.7) at flow rate of 1.5 mL min–1 and with a column oven temperature of 20°C. All supernatant samples were previously diluted with the eluent (1:1), centrifuged (Heraus Pico17 microCentrifuge, Thermo Scientific, Germany) for 5 min at 13000 rpm and filtered through 0.2 μm filters (Rotilabo® syringe filter, CA 0.2 μm, Ø 15 mm).

Quantification of cysteine was performed using reversed-phase UHPLC (X-LC Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with fluorescence detector (Extinction 340 nm + Emission 455 nm). A Waters XBridge BEH C18 XP column (Waters, Milford, MA, United States) at 25°C and a gradient method were employed. Mobile Phase A and B consisted of 25 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2) + tetrahydrofuran (95:5, v/v) and 25 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2) + acetonitrile + methanol (50:15:35, v/v/v), respectively. Prior to quantification, all samples were diluted 1:10 with double-distilled water and a thiols reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (10 μL sample, 80 μL water and 10 μL TCEP). Derivatization of reduced samples was performed with ortho-phthalaldehyde after alkylation of free sulfhydryl groups with iodoacetic acid (20 μL/50 μL sample).

Off-line H2 analysis of serum bottles and reactor headspace was performed with a Multiple Gas Analyzer coupled with Helium Ionization Detector (HID) and Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) (SRI 8610C, SRI Instruments, Bad Honnef, Germany). Gas separation was carried out with Mole Sieve 5 Å, 13 × 7 and HayeSep D columns, at 53°C for 10 min. Helium was used as carrier gas, with a pressure of 20 psi. A 2.5 mL gas tight syringe (Hamilton®, CS Chromatographie, Germany) was used for sampling.

In order to analyze the isotopic ratio of the extracellular acetate produced by D. orientis with GC-MS/MS, a derivatization method via alkylation to propyl-acetate with methyl chloroformate and an extraction with methyl tert-butyl ether were employed (Tumanov et al., 2016). A Trace GC Ultra – TSQ 8000 Triple Quadrupole (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) with a VF-5 ms + 10 m EZ-Guard column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) was utilized. Samples (1.0 μL) were injected using split mode (1:50) and an inlet temperature of 200°C. The GC gas carrier was Helium at 1.0 mL min–1. The GC oven temperature profile was of 1 min at 45°C, followed by a first ramp 25°C min–1 to 60°C and a second ramp of 50°C min–1 to 190°C, which was then held for 2 min. The temperature of MS transfer line and ion source were set to 280 and 300°C, respectively. The atom percent 13C of derivatized acetate was calculated through the following equation (Hayes, 2004):

Since hydrogen is a critical reaction partner in our system, we first evaluated the starting potential of H2 evolution at our BES cathode. A duplicate abiotic test at different applied cathodic potentials (Ecath) was performed, starting from −600 mV vs. Ag/AgClsat. KCl (all potentials are reported against this reference) and going more negative (Supplementary Figure S1A). The theoretical H2 evolution potential in neutral pH conditions is −610 mV and, indeed, at Ecath of −600 mV no H2 was detected in the cathodic headspace. H2 evolution was observed at potentials of −800 mV and lower.

To investigate the electroactivity of D. orientis, H-type BES reactors were operated under different cathodic polarization conditions. The first experiment was conducted H2-free at an Ecath of −600 mV, and the second at −900 mV, where in-situ electrochemical H2 production occurred. Finally, to boost the initial growth of D. orientis and then test its ability to directly use the cathode as electron donor, a third test with a start-up phase of −900 mV and an electrocatalytic phase of −550 mV was carried out. Growth profiles and the current density (j) data are shown in Figure 1A (with replicated data in Supplementary Figure S2). High negative current was only observed in D. orientis biocathodes poised at −900 mV, with a maximum current density (jmax) of −190 μA cm–2. The D. orientis growth curve followed the current trend: in both −900 mV biocathodes, the exponential growth phase corresponded to the steep increment in current consumption (ODmax 0.21 and 0.24). On the contrary, at −550 and −600 mV no planktonic growth was detected (ODmax 0.1 and 0.09). These findings suggest an inability of the strain to directly use the energy from the cathodic electrode to maintain its growth. Sulfate quantification data confirmed these results: sulfate removal occurred only when D. orientis’ biocathodes were poised at −900 mV (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Performances of Desulfosporosinus orientis biocathodes at different Ecath. (A) Current density and growth profile. For clarity only one replicate is shown, for all data see Supplementary Figure S2; (B) Sulfate quantification in the catholyte; the data represent the average of all conducted replicates and standard deviation. (C) Cyclic Voltammetry analysis in blank (before inoculation) and after biotic polarizations (end of the test). Vertical dashed lines indicate the Ecath switch time point.

Cyclic Voltammetry outcomes supported chronoamperometric results, D. orientis’ growth profile and sulfate data (Figure 1C). The voltammograms of the −900 mV biocathodes showed a reduced overpotential for H2 evolution reaction and the maximum cathodic current was much higher, compared to blank analyses. Biotic CV exhibited an anodic wave starting at potentials above −600 mV, with a visible oxidation peak centered at −420 mV. This peak can be related to the oxidation of sulfur species present in the catholyte (Sun et al., 2009). On the contrary, the CV analysis of the −600 mV biocathodes exhibited no different electroactivity compared to blank analyses. At the end of the experiment, graphite pieces of the −600 and −900 mV biocathodes were fixed and analyzed with SEM to investigate D. orientis colonization of the electrode surface (Supplementary Figure S2D–E). The graphite surface was not covered by a biofilm and no visible extracellular polymeric substance was observed. Few microbial cells were found only on the −900 mV graphite electrodes.

In order to investigate D. orientis’ ability of extracellular electron uptake using an inorganic insoluble electron donor, corrosion tests in serum bottle with Fe0 granules and N2/CO2 gas phase were performed (Supplementary Material Section 1). But also here no microbial growth or biological activity beyond abiotic corrosive hydrogen production and consumption was detected (Supplementary Figure S3). In contrast, autotrophic control cultures with H2/CO2 grew well, readily reduced sulfate and produced acetate (Supplementary Figure S3C).

To investigate the biolectrochemical sulfate removal of D. orientis in autotrophic conditions, the biocathode performance was investigated with different Ecath ranging from −800 to −900 mV. Those potentials where chosen on basis of biotic CV analysis to find the best Ecath in term of sulfate removal and BES coulombic efficiency. Abiotic cathodes with the same polarization conditions and biotic cathodes without potentiostatic control served as controls. Figures 2A,B show the changes of current consumption, D. orientis growth and sulfate removal as a function of time, while Table 1 reports a summary of biocathodic/cathodic performances, including coulombic efficiency data. −900 mV biocathodes exhibited the best performances in term of biomass growth (ODmax = 0.21 ± 0.02), current density (jmax = −75 ± 1 μA cm–2), and 10-days sulfate removal (61 ± 2%). However, the total coulombic efficiency of these biocathodes accounted only for 44 ± 0.6%. −800 mV biocathodes resulted, on the contrary, in higher total coulombic efficiency (77 ± 39%) and electron recovery in sulfate reduction (58 ± 25%). However, the cathodic activity and the 10-days sulfate reduction in these −800 mV biocathodes was very low (8 ± 7% sulfate reduction) (see Supplementary Table S1 for statistical analysis of −900 mV vs. −800 mV performances). The control reactors showed no sulfate reduction (Figure 2D), confirming D. orientis’ involvement in sulfate removal. −900 mV abiotic cathodes exhibited a negative current over time, pointing to another abiotic reduction reaction governing the system at these polarization conditions, most probably abiotic H2 evolution (Figures 2C and Supplementary Figure S4E). These findings could explain the low total CE of −900 mV biocathodes, as most likely the unassigned charges are going into abiotic H2 production.

Figure 2. Sulfate reduction performances of D. orientis biocathodes and abiotic controls at different Ecath. (A) Current density and D. orientis growth profile and (B) biotic sulfate reduction trend; (C) abiotic current density and (D) abiotic and biotic control sulfate reduction profiles. For clarity of data, only one replicate is shown, further replicate data are provided in Supplementary Figure S4.

We also noticed the production of acetate in these experiments. Since some bacteria of the class of Clostridia are able to use amino acids as carbon and energy source (Fonknechten et al., 2010), we evaluated the influence of cysteine, which is used as a reducing agent in our media, on our biocathode performance (Supplementary Material Section 2). In the D. orientis genome, two genes coding for the key enzyme of the cysteine degradation pathway, a carbon-sulfur lyase, are present (Desor_0514 and Desor_2544). When comparing two different concentrations of initial cysteine input at the different Ecath, indeed, the final titer of acetate was dependent on the input of cysteine, as well as on the Ecath (Figure 3). In addition, the final acetate titer was never higher than the input cysteine concentration (Table 1).

Figure 3. Cysteine consumption and acetate production profiles of D. orientis biocathodes at different Ecath. (A) –900 mV with 3.2 and 1.9 mM cysteine input; (B) 1.9 mM cysteine input at –850 mV and –800 mV. The data represent the average of triplicate or duplicate reactors and the error bars show standard deviations.

Anaerobic sulfate respiration is energetically more favorable than acetogenesis (Conrad et al., 1986):

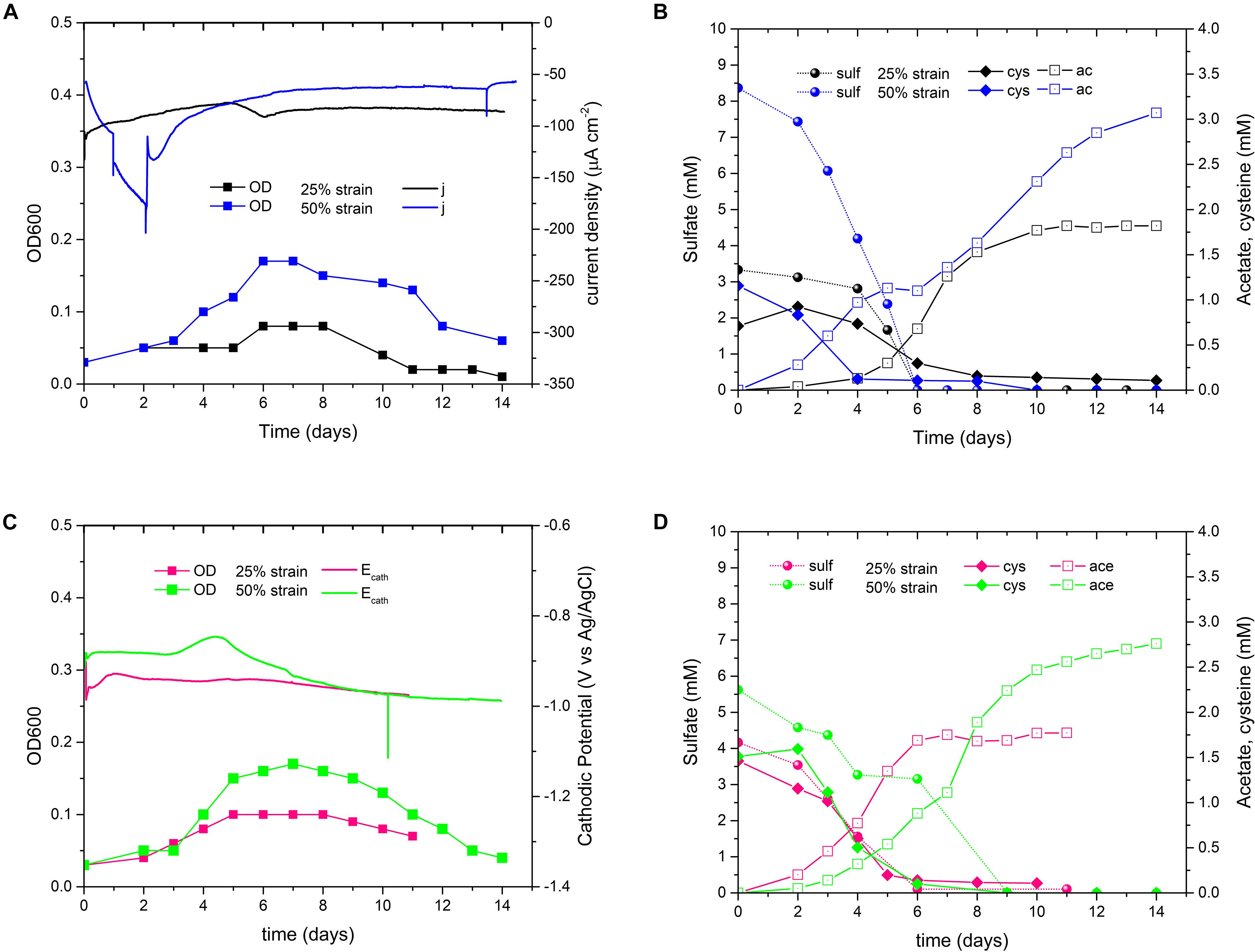

In order to foster the acetogenesis at the expense of sulfate respiration, ALE of D. orientis in sulfate limiting, autotrophic conditions was performed. Two different stress cultivation conditions were employed: 50 and 25% of the optimal sulfate concentration (18 mM = 100%) recommended for D. orientis (deCamposRodrigues and Rosenbaum, 2014). A detailed characterization of the evolved strains was performed after the 3rd and 17th culture transfer (Figure 4, Table 2, and Supplementary Table S2). After three culture transfers, both the 50% and the 25% strains outperformed the 100% strain in term of final acetate titer (P-values = 0.0001 and = 0.0174) and yield per maximum biomass (P-values = 0.0008 and = 0.0015). In all strains, the maximum acetate productivity was similar (difference not statistically significant) and was reached during the exponential growth phase, for then decreasing during stationary phase. In both sulfate limiting conditions, lower cell growth compared to the optimal cultivation conditions was observed and sulfate was depleted after 4 days of cultivation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. D. orientis ALE experiment in sulfate-limiting, autotrophic growth conditions with H2/CO2. (A) pH and OD profiles, (B) sulfate reduction and acetate production trends of 3rd culture transfer; (C) pH and OD profiles, (D) sulfate reduction and acetate production trends of 17th culture transfer. The data represent the average of triplicate cultures and the error bars show standard deviation. 100% = 18 mM sulfate; 50% = 9 mM sulfate; 25% = 4.5 mM sulfate.

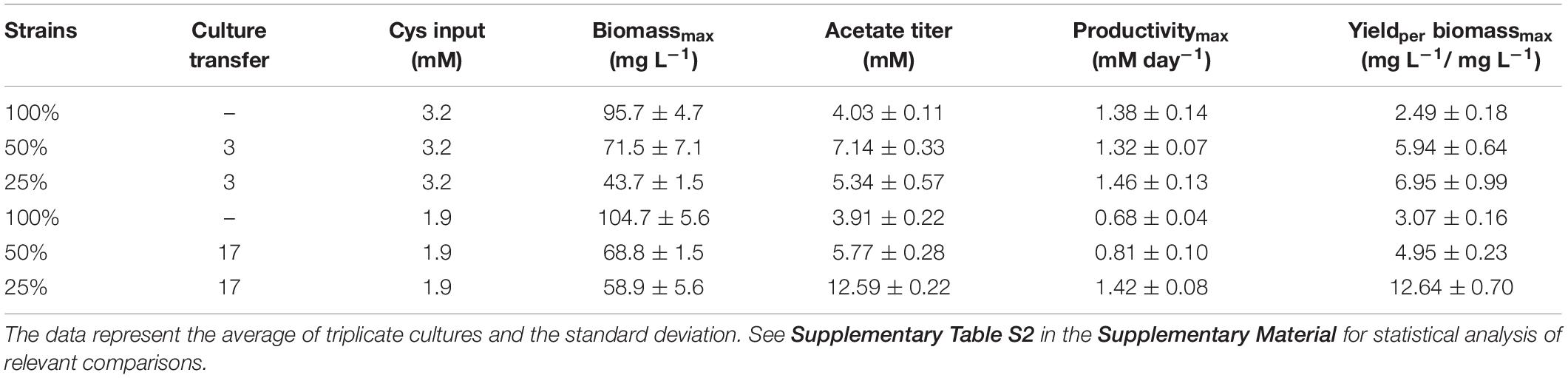

Table 2. Performances of D. orientis strains adapted to sulfate-limiting growth conditions (100% = 18 mM sulfate; 50% = 9 mM sulfate; 25% = 4.5 mM sulfate).

After 17 culture transfers, the 25% strain clearly improved its performances in acetate production and cell growth. The final titer was 2.4–fold higher than the one obtained after only three transfers (P-value < 0.0001), while the yield per maximum biomass was approximately doubled (P-value = 0.0012). The maximum productivity stayed similar (difference not statistically significant), but a high production rate (in range of 1–1.4 mM day–1) was maintained for the entire cultivation period (Figure 4D). Furthermore, after 8 days of cultivation, small quantities of butyrate were produced, reaching a final titer of 0.43 ± 0.02 mM. Butyrate production started at acetate concentrations higher than 8 mM, in accordance with the previous work of Cypionka and Pfenning (Cypionka and Pfennig, 1986). The 50% strain, on the contrary, exhibited decreased performance compared to the 3rd transfer characterization (Table 2).

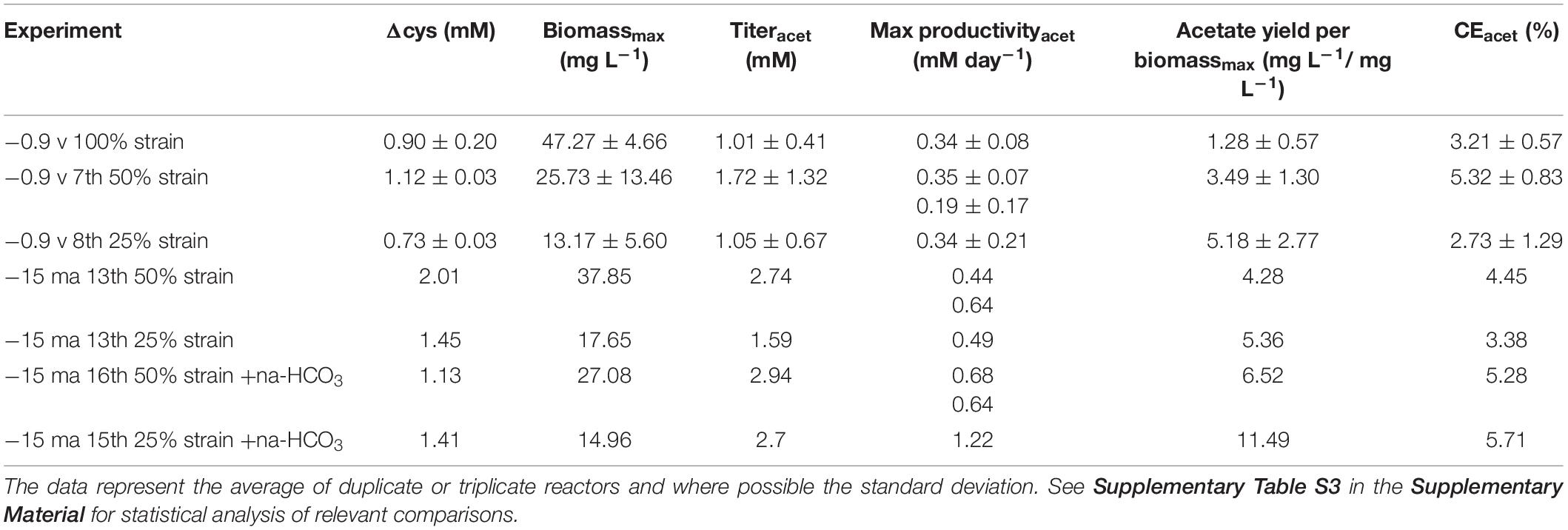

We evaluated the performances of both 50 and 25% sulfate evolved strains at Ecath of −900 mV potentiostatic control and with a stable cathodic current at −15 mA of galvanostatic control. The goal of these experiments was to understand if acetate production in BES only comes from cysteine fermentation or if the adapted D. orientis strains are able to perform bioelectrosynthesis using CO2 and cathodically generated H2. Following Eq. S4, clear bioelectrosynthesis can be stated if the acetate titers were higher than the cysteine consumed.

The tests were performed in triplicate with the 7th 50% and the 8th 25% culture transfer, respectively, but the replicates behaved very differently in term of current consumption, biomass growth and acetate production (the best replicates are shown in Figures 5A,B, the others in Supplementary Figure S5). If we consider the best replicates (Figure 5B), the 50% biocathode outperformed the 25% for the final acetate titer (not statistically significant considering all replicates), while the latter exhibited a higher acetate yield per biomass (not statistically significant considering all replicates, see Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3). The maximum acetate productivity values of both strains were similar to the wild type biocathodes, and always occurred before cysteine depletion (Figure 5B). Yet, after complete cysteine and sulfate consumption, the 50% biocathodes exhibited a second acetate production phase lasting until the end of the test. The final acetate titer of the best performing 25% biocathode exceeded the cysteine input by ∼200%, while the one of the best performing 50% biocathode by ∼165%. Thus, both reactors clearly showed electrosynthetic acetate production, and similar values of cathodic current density [javerage(50%) = −100 μA cm–2, javerage(25%) = −86 μAcm–2].

Figure 5. Comparison of D. orientis adapted strains biocathodes with potentiostatic and galvanostatic control. –900 mV Biocathodes inoculated with the 7th culture transfer of 50% sulfate strain and with the 8th culture transfer of the 25% sulfate strain: (A) OD and current density trends; (B) sulfate reduction, cysteine consumption and acetate production profiles. The best-performing reactors of the 50 and 25% strains are shown. See Supplementary Figure S5 for all the replicates. –15 mA Biocathodes: (C) OD and cathodic potential profiles and (D) sulfate reduction, cysteine consumption and acetate production profiles of 50% strains (13th culture transfer as inoculum) and 25% strains (13th culture transfer as inoculum). See Supplementary Figure S6 for replicate reactors.

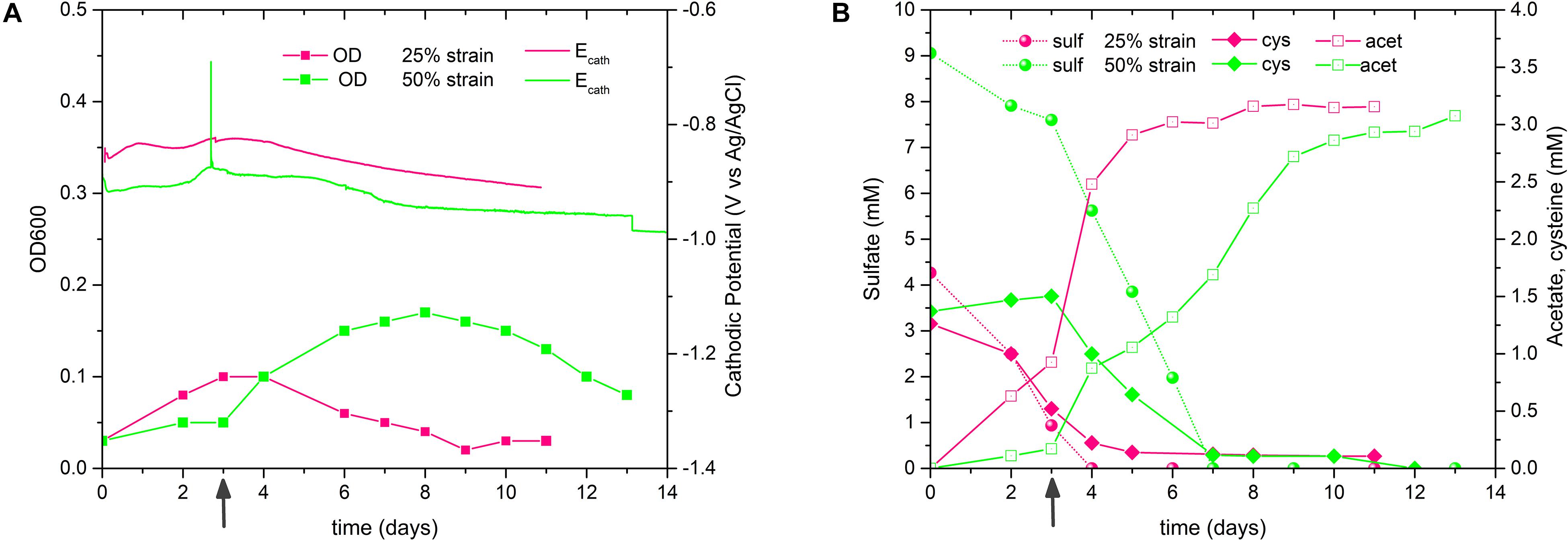

Table 3. Performances of biocathodes inoculated with D. orientis strains adapted to sulfate-limiting growth conditions.

Consequently, we decided to switch to a fixed cathodic current of −15 mA (=96 μA cm–2). The biocathodes were inoculated with the 13th culture transfer of both adapted strains (Figures 5C,D). Both biocathodes were more reproducible, especially regarding growth and acetate production profile (replicates Supplementary Figures S6A,B). The 50% biocathodes outperformed the 25% for the final acetate titer and for biomass production (Table 3), while the latter showed a higher acetate yield per biomass. In both adapted strains, the maximum productivity increased in comparison to the potentiostatically controlled biocathodes (Table 3), and the 50% biocathodes exhibited a maximum value of 0.64 mM day–1 during the second production phase with a final electrosynthetic acetate titer of on average 0.74 mM.

Next, we increased the availability of CO2 in the reactors by doubling the normal concentration of Na-bicarbonate in the catholyte of 1 gL–1 with a second pulse after 3 days of experiment. It should be noted that the catholyte should be always CO2 saturated thanks to the continuous flushing of CO2/N2 (20:80) at flow rate of 50 mL min–1. The experiment was inoculated with the 16th and 15th culture transfers of 50 and 25% strains, respectively, and −15 mA cathodic current was applied. As shown in Figure 6, Supplementary Figures S6C,D, and Table 3, all these biocathodes exhibited a greater electrosynthetic acetate production than the previous BES tests (average duplicate: 1.81 mM the 50% strain and 1.29 mM the 25% strain). Furthermore, the 25% biocathodes drastically increased the maximum acetate productivity and the acetate yield per biomass, reaching values very similar to non-electrochemical serum bottles experiments (Tables 2 and 3): 1.22 mM day–1 and 11.49 mg L–1/mg L–1, respectively.

Figure 6. Performance of D. orientis adapted strains biocathodes with pulsed Na-bicarbonate and –15 mA applied cathodic current. (A) OD and cathodic potential profiles and (B) sulfate reduction, cysteine consumption and acetate production profiles. 50% sulfate biocathodes were inoculated with the 16th culture transfer, while 25% sulfate biocathodes with the 15th culture transfer. Dark gray arrows indicate the second pulse of 1 g L– 1 Na-bicarbonate. See Supplementary Figure S6 for replicate reactors.

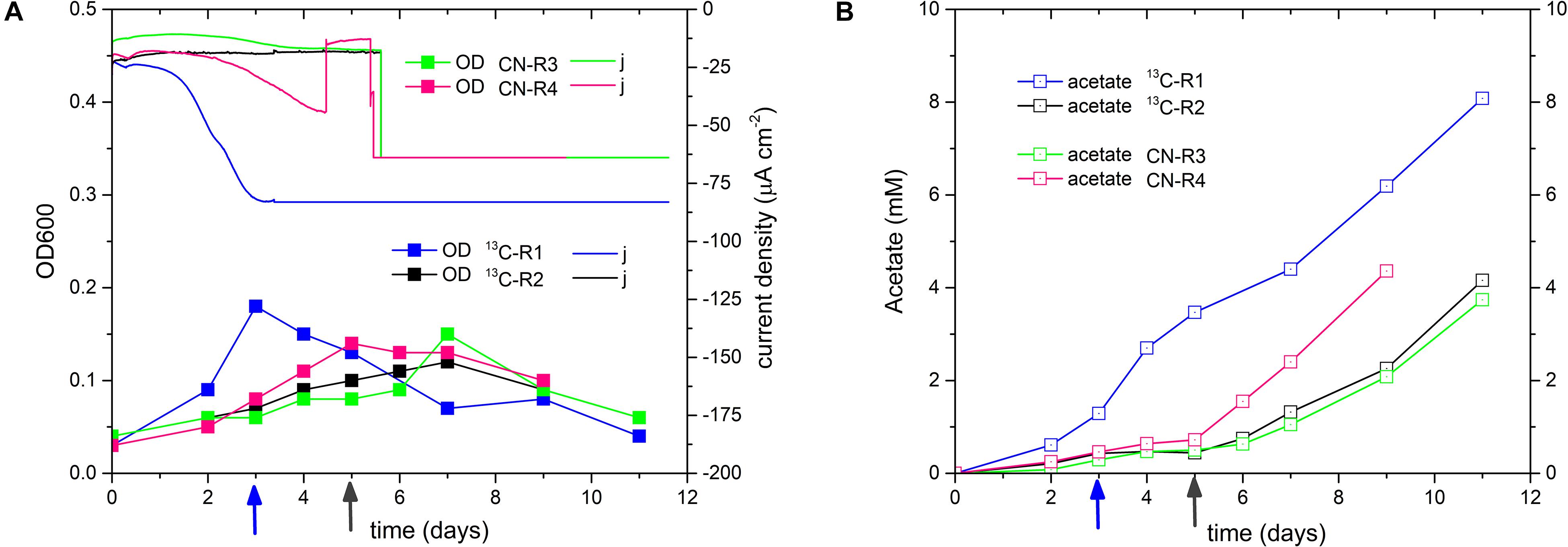

A final confirmation of D. orientis’ bioelectrosynthesis ability was obtained through 13C-labeling BES experiments with the 18th culture transfer of the 25% strain. CO2 is the substrate of the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (Ragsdale and Pierce, 2009; Berg, 2011). Dissolved CO2 can enter in D. orientis cells by membrane diffusion, while bicarbonate enters via an ABC-type transporter. As for other acetogens, D. orientis can convert intracellular bicarbonate to CO2 via carbonic anhydrases (Schnappauf et al., 1997; Pander et al., 2019). Since continuous flushing of 13CO2 gas would be prohibitively expensive, Na-H13CO3 was used and the flow rate of CO2/N2 gas feeding was decreased to 15 mL min–1. To avoid basification problems, 0.1 M MOPS buffer was added in the catholyte and the biocathode start-up was performed at Ecath −900 mV (Figure 7). Two reactors with Na-H12CO3 were run as controls. A 2nd pulse of Na-HCO3 was added during D. orientis middle/late exponential growth phase. Afterward, BES control was switched to a fixed applied current of −10 mA (−13 mA for 13C-Reactor 1, since it exhibited a much higher current during potentiostatic control).

Figure 7. Performance of 13C labeling BES experiments, inoculated with the 18th culture transfer of 25% sulfate D. orientis strain. (A) current density and OD trends; (B) acetate production profile. 13C-R are biocathodes with Na-H13CO3, while CN-R are controls with normal Na-H12CO3. The second pulse of bicarbonate was added at day 3 in 13C-R1 (blue arrow), and at day 5 in the other reactors (gray arrow).

The new BES experimental set-up resulted in a drastic increase of the maximum biomass generated (−13 mA biocathode = 49.97 mg L–1 and −10 mA biocathodesaverage = 38.30 ± 4.11 mgL–1) that yielded the highest final acetate titers of all the tests reported in this study (−13 mA biocathode = 8.08 mM and −10 mA biocathodesaverage = 4.09 ± 0.32 mM) (see Supplementary Table S3 for statistical analysis). Maximum productivities were 0.92 ± 0.08 mM day–1 at the end of the test for the −10 mA biocathodes and 1.41 mM day–1 for the −13 mA biocathodes right after the bicarbonate pulse. The acetate yield per biomassmax was lower (−13 mA biocathode: 9.55 mg L–1/ mg L–1 and −10 mA biocathodes: 6.38 ± 1.01 mgL–1/ mgL–1) in comparison to the previous BES test with the 25% strain 15th culture transfer (Table 3).

The atom percent 13C of derivatized acetate samples was measured by GC-MS/MS. Isotope ratio analysis was performed using the fragment ions CH3CO+ and CH3COOH, having mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of 43 (M0), 44 (M0+1) and 61 (M0), 62 (M0+1), respectively. Supplementary Table S4 reports the atom percent 13C of the acetate produced by D. orientis biocathodes and in 2.5 mM and 5 mM acetate standards. Control reactors with only 12C-bicarbonate showed a 13C% similar to acetate standards and corresponding, thus, to 13C natural abundance. The samples taken after the addition of the 2nd pulse of bicarbonate in 13C- biocathodes exhibited an atom percent 13C 2-folds higher than 12 C- biocathodes (difference statistically significant, see Supplementary Tables S4, S5), confirming that some of the acetate was formed with the provided Na-H13CO3. These results are in accordance with the fact that, in our experimental conditions, D. orientis cells receive a dominant carbon supply directly from 12CO2 gas feeding compared to 13CO2 provided from 13C-bicarbonate. Estimate calculations on the availability of 13CO2 and 12CO2 in the catholyte based on the chemical equilibria are reported in the Supplementary Material Section 3.

The data presented in this work demonstrated the ability of D. orientis to perform a mediated electron uptake from cathodes in the presence of abiotically produced or biologically induced H2. High planktonic biomass production and high sulfate reduction were just observed in biocathodes poised more negative than −850 mV. In these conditions, H2 was even detected in the cathodic headspace, and, thus, it most likely represents the electron donor for D. orientis metabolism. Moreover, no biofilm, typically required for direct electron uptake, was observed on the graphite electrode surface during SEM imaging.

This conclusion was confirmed by metallic iron corrosion experiments, which can help in the understandings of microbial EEU mechanisms: if a direct electron uptake pathway is present, microbes are able to use Fe0 as sole electron donor. Very recently, Tang et al. (2019) has demonstrated direct metal electron uptake via c-OMCs in the autotrophic strain Geobacter sulfurreducens ACL. Evidences of similar EEU mechanism have been reported for two iron-corroding SRB, Desulfopila corrodens strain IS4 (Beese-Vasbender et al., 2015) and Desulfovibrio ferrophilus IS5 (Deng and Okamoto, 2018; Deng et al., 2018).

Desulfosporosinus orientis was not able to use Fe0 as extracellular electron donor, which is supported by D. orientis’ belonging to the cytochrome-poor group of SRB, lacking c-OMCs and periplasmatic multihemes cytochromes (Rabus et al., 2015; Agostino and Rosenbaum, 2018). The electron transport chain is rather based on membrane-bound hydrogenases and formate dehydrogenases associated to the inner membrane through a b-type cytochrome that directly reduces the menaquinone pool (Rabus et al., 2015; Agostino and Rosenbaum, 2018). Specifically, the genes Desor_0303, Desor_0911, and Desor_4119 code for the membrane-associated [NiFe]-hydrogenases of group 1, responsible of hydrogen uptake (Peters et al., 2015). Moreover, a [NiFe]-hydrogenase of group 4f (Desor_1267), with a predicted activity related to H2-evolution, is also present in its genome. This hydrogenase is a component of the anaerobic formate hydrogen lyase complex (Desor_1265 to Desor_1270) that couples oxidation of formate to the reduction of protons to H2 (Sinha et al., 2015). After microbial cell lysis, the release of this complex in the cathodic environment, as well as of the cytoplasmatic [FeFe]-electron bifurcating hydrogenases (Desor_1568, Desor_4949, Desor_5363) could facilitate biotic, non-microbial H2 production by decreasing the hydrogen evolution overpotential (Deutzmann et al., 2015). This possible EEU mechanism in D. orientis should be further investigated via BES experiments with cell-free spent medium as catholyte (Rowe et al., 2019). Moreover, very recently, the maintenance of low H2 partial pressures via microbial H2 consumption was proposed as additional mechanism by which hydrogenotrophic microorganisms could increase the H2 evolution rate on a cathode or Fe0 (Philips, 2020).

The second goal of this study was to characterize the ability of D. orientis for bioelectrochemical sulfate reduction and acetate production with CO2 as carbon source.

All previous works related to bioelectrochemical sulfate removal were carried out using undefined mixed-community autotrophic biocathodes, as we recently reviewed (Agostino and Rosenbaum, 2018). The biocathodic inoculum usually consisted of consortia enriched from wastewater treatment sludge, sewer and sediment, mostly dominated by Desulfovibrio species. In BES research, mixed communities often outperform pure culture biocatalysts, such as for electricity generation in Microbial Fuel Cell and for acetate production in MES. Nevertheless, in this case, D. orientis maximum sulfate reduction rate (SRR) (0.19 ± 0.04 g L–1 day–1 at Ecath −900 mV) was very similar to mixed-community biocathodes (Agostino and Rosenbaum, 2018), except for the works of the Freguia group who obtained a SRRmax of 5.6 g L–1 day–1 but at very negative Ecath −1300 mV (Pozo et al., 2017).

Regarding acetate production with pure cultures, the acetogenic strains Sporomusa ovata and C. ljungdahlii are producing the highest amount of acetate, with maximum production rates of 0.88 and 2.4 mM day–1, at cathodic potentials negative enough to permit abiotic H2 evolution (Bajracharya et al., 2015; Aryal et al., 2017). In addition, acetate productivity by Sporomusa-driven MES can further increase to 3.12 mM day–1, after its adaptation to methanol as only carbon and energy source (Tremblay et al., 2015).

In optimal sulfate conditions, D. orientis seems to generate acetate only via cysteine fermentation, with a maximum productivity of 0.34 mM day–1. However, after successful ALE in sulfate-limiting conditions, both 25 and 50% adapted D. orientis strains (15th and 16th culture transfer) have shown electrosynthetic acetate production biocathodes with fixed current flow of −15 mA and 2 g L–1 of Na-HCO3. The maximum acetate productivity of the 50% sulfate biocathodes (0.64 mM day–1) was very similar to the values achieved by some Sporomusa species (S. acidovorans and S. malonica) (Aryal et al., 2017). The maximum productivity of the 25% sulfate D. orientis biocathodes was double (1.22 mM day–1) compared to 50% biocathodes.

We confirmed electrosynthetic acetate production from CO2 in a modified BES set-up with 13C-labeling experiments. In this test, continuous acetate production even into the D. orientis stationary/dying phase was obtained with the 25% biocathodes, resulting in the highest acetate final titers (−13 mA biocathode = 8.08 mM and −10 mA biocathodesaverage = 4.09 mM) and productivities (−13 mA biocathode = 1.41 mM day–1 and −10 mA biocathodesaverage = 0.92 ± 0.08 mM day–1) of all the tests reported in this work. Since this performance is similar to other acetogenic pure-cultures, D. orientis might compete well with S. ovata or C. ljungdahlii for MES applications. The main differences in this modified BES set-up, compared to the other experiments of our study, consisted of the addition of MOPS buffer and the utilization of a lower CO2 feeding flow rate. Independently of the presence or not of MOPS buffer, the catholyte pH always rose to values of 7.4–7.5 along the experiments and, thus, extracellular pH cannot possibly be the limiting factor. Acetate production performances seem more correlated to the CO2 flow rate and the amount of H2 abiotically produced or biologically induced during the biocathodic start-up phase. The stoichiometry ratio of H2 and CO2 for acetate production is 4 to 2. High amount of dissolved CO2 and /or H2 could inhibit D. orientis growth and production performances, as demonstrated in high pressure gas fermentation studies with other acetogenic strains (Weuster-botz, 2016; Oswald et al., 2018). Further investigations using CO2 and H2 sensors inside the catholyte could clarified, which of these two elements represents the limiting and/or inhibiting factor for acetate production within our D. orientis biocathodes set-up.

During ALE experiments, the 25% adapted strain has shown butyrate production ability in serum bottles with H2 and CO2 atmosphere. Butyrate is a C4 carboxylic acid with higher market value than acetate. It has multiple applications in pharmaceutical, chemical, food and cosmetic industries (Dwidar et al., 2012). Moreover, butyrate is becoming a valuable feed supplement for animal production, as alternative of in-feed antibiotics (Bedford and Gong, 2018). In chemical industry, its major application is in the production of cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) polymers. Bioelectrosynthesis of butyrate from CO2-rich waste gas streams represents a recent and promising alternative to the current fossil-fuel-based commercial manufacturing (Ganigué et al., 2015; Jourdin et al., 2019). Consequently, future works will focus the attention on a better control of BES process parameters (e.g., CO2 feeding strategy, controlled electrochemical H2 dosing, stirring rate and high cells density inoculum) in order to achieve and optimize electrosynthetically butyrate production with D. orientis biocathodes.

In deep electrophysiological characterization of novel pure culture electroautotrophs are still pretty scarce. Growing pure culture autotrophic microbes in BES is a hard task. In our opinion, this study provides a valuable contribute to the field of electromicrobiology. The more we know, and we learn on the physiology and the metabolic features of these fascinating bacteria, the more we can accelerate the development of BES-based technologies for sustainable bioproduction from CO2-rich waste streams.

All relevant data are included in this manuscript and the corresponding Supplementary Material.

VA coordinated the study, designed, conducted and analyzed the experiments, and prepared the draft of the manuscript. AL conducted and analyzed the part of the experiments. BB conducted the cysteine quantification analyses and revised the manuscript. AP supervised and optimized the GC-MS/MS analyses. VR conducted the SEM sample preparation and analyses. LB discussed the work and revised the manuscript. MR conceived the work, advised on the experimental plan, discussed the experiments, revised the manuscript, and provided the funding.

This work was financially supported by the Cluster of Excellence Tailor-Made Fuels from Biomass EXC 236, which was funded by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments to promote Science and Research at German Universities. The laboratory of LB was partially funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy within the Cluster of Excellence 2186 “The Fuel Science Center.” The GC-MS/MS was funded by the DFG under grant agreement No. 233069590.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Liesa Pötschke for fruitful discussions.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00457/full#supplementary-material

Adams, M. E., and Postgate, J. (1959). A new sulphate-reducing vibrio. J. Gen. Microbiol. 20, 252–257.

Agostino, V., and Rosenbaum, M. A. (2018). Sulfate-reducing electroautotrophs and their applications in bioelectrochemical systems. Front. Energy Res. 6:55. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2018.00055

Aryal, N., Tremblay, P. L., Lizak, D. M., and Zhang, T. (2017). Performance of different Sporomusa species for the microbial electrosynthesis of acetate from carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 233, 184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.02.128

Bajracharya, S., Srikanth, S., Mohanakrishna, G., Zacharia, R., Strik, D. P., and Pant, D. (2017). Biotransformation of carbon dioxide in bioelectrochemical systems: state of the art and future prospects. J. Power Sour. 356, 256–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.04.024

Bajracharya, S., Ter Heijne, A., Dominguez Benetton, X., Vanbroekhoven, K., Buisman, C. J. N., Strik, D. P. B. T. B., et al. (2015). Carbon dioxide reduction by mixed and pure cultures in microbial electrosynthesis using an assembly of graphite felt and stainless steel as a cathode. Bioresour. Technol. 195, 14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.05.081

Bedford, A., and Gong, J. (2018). Implications of butyrate and its derivatives for gut health and animal production. Anim. Nutr. 4, 151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.08.010

Beese-Vasbender, P. F., Nayak, S., Erbe, A., Stratmann, M., and Mayrhofer, K. J. J. (2015). Electrochemical characterization of direct electron uptake in electrical microbially influenced corrosion of iron by the lithoautotrophic SRB Desulfopila corrodens strain IS4. Electrochim. Acta 167, 321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.03.184

Berg, I. A. (2011). Ecological aspects of the distribution of different autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1925–1936. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02473-10

Buckel, W., and Thauer, R. K. (2018). Flavin-based electron bifurcation, ferredoxin, flavodoxin, and anaerobic respiration with protons (Ech) or NAD+ (Rnf) as electron acceptors: a historical review. Front. Microbiol. 9:401. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00401

Campbell, L. L., and Postgate, J. R. (1965). Classification of the spore-forming sulfate-reducing bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 29, 359–363.

Conrad, R., Schink, B., and Phelps, T. J. (1986). Thermodynamics of H2-consuming and H2-producing metabolic reactions in diverse methanogenic environments under in situ conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 38, 353–360.

Cypionka, H., and Pfennig, N. (1986). Growth yields of Desulfotomaculum orientis with hydrogen in chemostat culture. Archiv. Microbiol. 143, 396–399.

deCamposRodrigues, T., and Rosenbaum, M. A. (2014). Microbial Electroreduction: screening for new cathodic biocatalysts. Chemelectrochem 1, 1916–1922. doi: 10.1002/celc.201402239

Deng, X., Dohmae, N., Nealson, K. H., Hashimoto, K., and Okamoto, A. (2018). Multi-heme cytochromes provide a pathway for survival in energy-limited environments. Sci. Adv. 4:eaao5682. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao5682

Deng, X., and Okamoto, A. (2018). Electrode potential dependency of single-cell activity identifies the energetics of slow microbial electron uptake process. Front. Microbiol. 9:2744. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02744

Deutzmann, J. S., Sahin, M., and Spormann, A. M. (2015). Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis. mBio 6:496. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00496-15

Deutzmann, J. S., and Spormann, A. M. (2017). Enhanced microbial electrosynthesis by using defined co-cultures. ISME J. 11, 704–714. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.149

Dwidar, M., Park, J., Mitchell, R. J., and Sang, B. (2012). The Future of Butyric Acid in Industry. Sci. World J. 2012:471417. doi: 10.1100/2012/471417

Fonknechten, N., Chaussonnerie, S., Tricot, S., Lajus, A., Andreesen, J. R., Perchat, N., et al. (2010). Clostridium sticklandii, a specialist in amino acid degradation:Revisiting its metabolism through its genome sequence. BMC Genom. 11:555. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-555

Ganigué, R., Puig, S., Batlle-Vilanova, P., Balaguera, M. D., and Colprima, J. (2015). Microbial electrosynthesis of butyrate from carbon dioxide. Chem.Commun. 51, 3235–3238. doi: 10.1039/C4CC10121A

Hayes, J. M. (2004). An Introduction To Isotopic Calculations. Woods Hole, MA: National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Facility.

Jourdin, L., Winkelhorst, M., Rawls, B., Buisman, C. J. N., and Strik, D. P. B. T. B. (2019). Enhanced selectivity to butyrate and caproate above acetate in continuous bioelectrochemical chain elongation from CO2: steering with CO2 loading rate and hydraulic retention time. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 7:100284. doi: 10.1016/j.biteb.2019.100284

Karthikeyan, R., Singh, R., and Bose, A. (2019). Microbial electron uptake in microbial electrosynthesis: a mini-review. J. Indust. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46, 1419–1426. doi: 10.1007/s10295-019-02166-6

Klemps, R., Cypionka, H., Widdel, F., and Pfennig, N. (1985). Growth with hydrogen, and further physiological characteristics of Desulfotomaculum species. Archiv. Microbiol. 143, 203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00411048

Logan, B. E., Rossi, R., Ragab, A., and Saikaly, P. E. (2019). Electroactive microorganisms in bioelectrochemical systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17:319. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0173-x

Margaria, V., Tommasi, T., Pentassuglia, S., Agostino, V., Sacco, A., Armato, C., et al. (2017). Effects of pH variations on anodic marine consortia in a dual chamber microbial fuel cell. Intern. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 1820–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.07.250

Nevin, K. P., Woodard, T. L., Franks, A. E., Summers, A. E., and Lovley, D. R. L. (2010). Microbial electrosynthesis: feeding microbes electricity to convert carbon dioxide and water to multicarbon extracellular organic compounds. mBio 1, e103–e110. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00103-10.Editor

Oswald, F., Stoll, I. K., Zwick, M., Herbig, S., and Sauer, J. (2018). Formic acid formation by Clostridium ljungdahlii at elevated pressures of carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6:6. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00006

Pander, B., Harris, G., Scott, D. J., Winzer, K., Köpke, M., Simpson, S. D., et al. (2019). The carbonic anhydrase of Clostridium autoethanogenum represents a new subclass of β-carbonic anhydrases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 7275–7286. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10015-w

Pentassuglia, S., Agostino, V., and Tommasi, T. (2018). “EAB—electroactive biofilm: a biotechnological resource,” in Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering-Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry: Surface Science and Electrochemistry, ed. K. Wandelt (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 110–123.

Pester, M., Brambilla, E., Alazard, D., Rattei, T., Weinmaier, T., Han, J., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequences of Desulfosporosinus orientis DSM765T, Desulfosporosinus youngiae DSM17734T, Desulfosporosinus meridiei DSM13257T, and Desulfosporosinus acidiphilus DSM22704T. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6300–6301. doi: 10.1128/JB.01392-12

Peters, J. W., Schut, G. J., Boyd, E. S., Mulder, D. W., Shepard, E. M., Broderick, J. B., et al. (2015). [FeFe] - and [NiFe] -hydrogenase diversity, mechanism, and maturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 1350–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.11.021

Philips, J. (2020). Extracellular electron uptake by acetogenic bacteria: does H2 consumption favor the H2 evolution reaction ona cathode or metallic iron? Front. Microbiol. 10:2997. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02997

Pozo, G., Lu, Y., Pongy, S., Keller, J., Ledezma, P., and Freguia, S. (2017). Selective cathodic microbial bio fi lm retention allows a high current-to-sul fi de ef fi ciency in sulfate-reducing microbial electrolysis cells. Bioelectrochemistry 118, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2017.07.001

Rabus, R., Venceslau, S. S., Wöhlbrand, L., Voordouw, G., Wall, J. D., and Pereira, I. A. C. (2015). A post-genomic view of the ecophysiology, catabolism and biotechnological relevance of sulphate-reducing prokaryotes. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 66:321. doi: 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2015.05.002

Ragsdale, S. W., and Pierce, E. (2009). Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784, 1873–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.08.012.Acetogenesis

Robertson, W. J., Bowman, J. P., Franzmann, P. D., and Mee, B. J. (2001). Desulfosporosinus meridiei sp. nov., a spore- forming sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from gasolene-contaminated groundwater. Intern. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 133–140. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-1-133

Rowe, A. R., Xu, S., Gardel, E., Bose, A., Girguis, P., Amend, J. P., et al. (2019). Methane-linked mechanisms of electron uptake from cathodes by Methanosarcina barkeri. mBio 10:e02448-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02448-18

Schnappauf, G., Braus, G. H., Gössner, A. S., Drake, H. L., Braus-stromeyer, S. A., Schnappauf, G., et al. (1997). Carbonic anhydrase in Acetobacterium woodii and other acetogenic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 179, 7197–7200. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7197-7200.1997

Sinha, P., Roy, S., and Das, D. (2015). Role of formate hydrogen lyase complex in hydrogen production in facultative anaerobes. Intern. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 8806–8815. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.05.076

Sun, M., Mu, Z. X., Chen, Y. P., Sheng, G. P., and Liu, X. W. (2009). Microbe-assisted sulfide oxidation in the anode of a microbial fuel cell. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 3372–3377. doi: 10.1021/es802809m

Tang, H., Holmes, D. E., Ueki, T., Palacios, P. A., and Lovley, D. R. (2019). Iron corrosion via direct metal-microbe electron transfer. mBio 10, e303–e319. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00303-19

Tremblay, P. L., Höglund, D., Koza, A., Bonde, I., and Zhang, T. (2015). Adaptation of the autotrophic acetogen Sporomusa ovata to methanol accelerates the conversion of CO2 to organic products. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep16168

Tumanov, S., Bulusu, V., Gottlieb, E., and Kamphorst, J. J. (2016). A rapid method for quantifying free and bound acetate based on alkylation and GC-MS analysis. Cancer Metab. 4, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0157-

Weuster-botz, C. K. D. (2016). Effects of hydrogen partial pressure on autotrophic growth and product formation of Acetobacterium woodii. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 39, 1325–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00449-016-1600-2

Yee, M. O., and Rotaru, A. (2020). Extracellular electron uptake in Methanosarcinales is independent of multiheme c -type cytochromes. Sci. Rep. 10:372. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57206-z

Zaybak, Z., Logan, B. E., and Pisciotta, J. M. (2018). Electrotrophic activity and electrosynthetic acetate production by Desulfobacterium autotrophicum HRM2. Bioelectrochemistry 123, 150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2018.04.019

Keywords: sulfate-reducing bacteria, Desulfosporosinus, bioelectrochemical systems, cathode, microbial electrosynthesis, acetogenesis, CO2 reduction

Citation: Agostino V, Lenic A, Bardl B, Rizzotto V, Phan ANT, Blank LM and Rosenbaum MA (2020) Electrophysiology of the Facultative Autotrophic Bacterium Desulfosporosinus orientis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:457. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00457

Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 21 April 2020;

Published: 19 May 2020.

Edited by:

Madalena Santos Alves, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Albert Guisasola, Autonomous University of Barcelona, SpainCopyright © 2020 Agostino, Lenic, Bardl, Rizzotto, Phan, Blank and Rosenbaum. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Miriam A. Rosenbaum, bWlyaWFtLnJvc2VuYmF1bUBsZWlibml6LWhraS5kZQ==

†Present address: Valeria Agostino, Centre for Sustainable Future Technologies, Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Turin, Italy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.