95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. , 24 April 2015

Sec. Synthetic Biology

Volume 3 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2015.00048

This article is part of the Research Topic Cyanobacteria: The Green E. coli View all 14 articles

Victoria H. Work1

Victoria H. Work1 Matthew R. Melnicki2

Matthew R. Melnicki2 Eric A. Hill2

Eric A. Hill2 Fiona K. Davies3

Fiona K. Davies3 Leo A. Kucek2

Leo A. Kucek2 Alexander S. Beliaev2

Alexander S. Beliaev2 Matthew C. Posewitz3*

Matthew C. Posewitz3*The cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Pasteur culture collection 7002 was genetically engineered to synthesize biofuel-compatible medium-chain fatty acids (FAs) during photoautotrophic growth. Expression of a heterologous lauroyl-acyl carrier protein (C12:0-ACP) thioesterase with concurrent deletion of the endogenous putative acyl-ACP synthetase led to secretion of transesterifiable C12:0 FA in CO2-supplemented batch cultures. When grown at steady state over a range of light intensities in a light-emitting diode turbidostat photobioreactor, the C12-secreting mutant exhibited a modest reduction in growth rate and increased O2 evolution relative to the wild-type (WT). Inhibition of (i) glycogen synthesis by deletion of the glgC-encoded ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) and (ii) protein synthesis by nitrogen deprivation were investigated as potential mechanisms for metabolite redistribution to increase FA synthesis. Deletion of AGPase led to a 10-fold decrease in reducing carbohydrates and secretion of organic acids during nitrogen deprivation consistent with an energy spilling phenotype. When the carbohydrate-deficient background (ΔglgC) was modified for C12 secretion, no increase in C12 was achieved during nutrient replete growth, and no C12 was recovered from any strain upon nitrogen deprivation under the conditions used. At steady state, the growth rate of the ΔglgC strain saturated at a lower light intensity than the WT, but O2 evolution was not compromised and became increasingly decoupled from growth rate with rising irradiance. Photophysiological properties of the ΔglgC strain suggest energy dissipation from photosystem II and reconfiguration of electron flow at the level of the plastoquinone pool.

Photosynthetic metabolism generates a wide range of biomolecules fundamental to energy, agriculture, and health (Durrett et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2008; Atsumi et al., 2009; Lubner et al., 2009; Lindberg et al., 2010; Lu, 2010; Niederholtmeyer et al., 2010; Kilian et al., 2011; Wahlen et al., 2011; Ducat et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2012; Work et al., 2013; Sorek et al., 2014). Having rapid growth rates, efficient energy conversion, and metabolic adaptability, photosynthetic microorganisms (PSMs) including genetically tractable unicellular algae and cyanobacteria have received substantial attention for synthesizing biofuel precursors via native or transgenic processes (Ferrari et al., 1971; Cascon and Gilbert, 2000; Heifetz, 2000; Lee, 2001; Schmer et al., 2008; Rodolfi et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2011; Fore et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011; Radakovits et al., 2011; Soratana and Landis, 2011; Rosgaard et al., 2012; Bentley et al., 2013; Gronenberg et al., 2013; Leite et al., 2013; Möllers et al., 2014; Davies et al., 2015).

Biodiesel can be derived from biological fatty acids (FAs) extracted from photosynthetic organisms (Ma and Hanna, 1999; Durrett et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2008). While oil content and quality differs between species, the composition of FAs typically includes the predominant 16- and 18-carbon FAs (C16 and C18), as well as varying levels of shorter (C8–C14) and longer (≥C20) FAs (Gopinath et al., 2010). Currently, vegetable oil is the main source of the approximately 20 billion liters (L) of biodiesel produced yearly worldwide (Hoekman et al., 2012; Kopetz, 2013). However, recent efforts in genetic engineering seek to utilize microorganisms for FA production, a concept that would transition fuel production from cropland to bioreactors or pond systems (Lee, 2001; Hu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Rodolfi et al., 2009; Leite et al., 2013). Lauric acid (C12:0) is naturally synthesized by coconut, palm, and bay trees (Litchfield et al., 1967; Denke and Grundy, 1992) and, when esterified, exhibits qualities comparable to modern diesel fuel, with better cold-flow properties relative to longer chain FAs (Gopinath et al., 2010; Hoekman et al., 2012). Microbial C12 synthesis has been achieved via transgenics in both heterotrophic and photoautotrophic hosts (Ohlrogge et al., 1995; Lu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Radakovits et al., 2011; Lennen and Pfleger, 2012), offering diverse opportunities in production platforms.

In photosynthetic eukaryotes, FAs of specific chain lengths are hydrolyzed from acyl carrier protein (ACP) by thioesterase enzymes, and the released FAs move out of the chloroplast into the cytoplasm where they are activated by coenzyme A (CoA) to facilitate transfer into higher lipids (Radakovits et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013). It has been found that many bacteria, including cyanobacteria, typically bypass the free FA (FFA) intermediate when assembling newly synthesized FA into membrane lipids (Sato and Wada, 2010; Jansson, 2012). When heterologous thioesterases are expressed in certain bacteria, most of the hydrolyzed FFA is found either in the culture medium or associated with the outside of the cell (Voelker and Davies, 1994; Ohlrogge et al., 1995; Liu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Ruffing and Jones, 2012; Ruffing, 2014). Though the mechanism of secretion is not established, it is known that extracellular FFA can move back across the membrane and be reincorporated into metabolism by an acyl–acyl carrier protein synthetase (AAS) (Kaczmarzyk and Fulda, 2010). If this enzyme is disrupted, FFAs remain in the medium and can separate from the aqueous cultures. In the present study, carbon distribution in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Pasteur culture collection (PCC) 7002 was modified for C12 FFA synthesis by heterologous thioesterase expression (and AAS deletion) in both wild-type (WT) and carbohydrate-deficient genetic backgrounds.

Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (Synechococcus sp. 7002 hereafter) was genetically modified using previously described protocols (Frigaard et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2011). The pAQ1Ex plasmid containing the Synechocystis sp. 6803 promoter cpcBA (Xu et al., 2011) and spectinomycin antibiotic-resistance gene aadA (Frigaard et al., 2004); and the kanamycin-resistant ΔglgC mutant (Guerra et al., 2013) harboring the gene aphII (Frigaard et al., 2004) were kindly provided from the laboratory of Donald A. Bryant. In Synechococcus sp. 7002, the gene glgC (NC_010475.1) encodes ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase), which activates glucose for polymerization. The gene fadD (NC_010475.1) encodes a putative AAS with homology to the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 gene slr1609 (NC_000911.1) (Kaczmarzyk and Fulda, 2010; Gao et al., 2012). A thioesterase derived from Umbellularia californica encoded by the gene fatB1 (GenBank M94159) hydrolyzes 12-carbon FA chains from ACP during FA synthesis yielding lauric acid (C12), and a version of this gene codon optimized for expression in Synechocystis sp. 6803 was generously provided from the laboratory of Roy Curtiss III (Liu et al., 2011). Lauric acid and C12 in the text designate transesterifiable 12-carbon saturated fatty acyl chains.

The pAQ1Ex vector was modified for knockin expression of fatB1 concurrent with deletion of the putative AAS. To construct the lauric acid secretion (LAS) module, fatB1 was placed between the vector’s promoter and antibiotic selection marker via NcoI/BamHI restriction sites. Flanking sequences of the fadD gene were inserted to target the cassette for homologous recombination using F||R primer pairs (5′–3′) 1:gttcacATGCATggctaggttcgtaatctttgggggta||gtatagGAATTCgccgaaatcatggct

acaatcctacttt, 2:catactGTCGACgatccgaatggcggaatcttcg||gttcacGCATGCgtg

ctggcttttgtcacaatcttcttg (restriction enzyme recognition sequences used in plasmid construction are capitalized). Transformation was accomplished following an established protocol for homologous recombination in this organism (Xu et al., 2011). Integration of the LAS module into all genome copies was achieved by increasing spectinomycin pressure and confirmed by PCR (not shown) for complete allele segregation using the 1F and 2R primers listed above. The strain SA01 contains the LAS module in a WT background, and the strain SA13 contains this module in a carbohydrate-deficient background (Table 1).

The saltwater medium A+ used in batch experiments contained, per liter, 18 g NaCl, 5 g MgSO4⋅7H2O, 1 g NaNO3, 0.6 g KCl, 0.05 g KH2PO4, 0.03 g Na2-EDTA, 0.27 g CaCl2, 1 g Trizma base (Tris), 1 mL L−1 of 3.89 g L−1 FeCl3⋅6H2O stock in 0.1 N HCl, and 1 mL L−1 of P1 metals micronutrient solution. The P1 stock solution contained, per liter, 34.26 g H3BO3, 4.32 g MnCl2⋅4H2O, 0.315 g ZnCl, 0.03 g MoO3 (85%), 12.15 mg CoCl2⋅6H2O, and 3 mg CuSO4⋅5H2O. For A+ medium without nitrogen (−N), NaNO3 was replaced by an equimolar amount of NaCl.

Liquid cell cultures were grown using a rotary shaker under constant illumination in an atmosphere of 1% CO2, 34°C, and 160 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (μmol m−2 s−1 hereafter) photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks with soft caps to facilitate gas exchange (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Batch flask cultures were grown in quadruplicate and standardized to 2.5 mg L−1 chlorophyll a at the beginning of each experiment. Pre-cultures were similarly normalized and grown to mid-linear phase (15–25 μg mL−1 chlorophyll a), whereupon cells were concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh medium for experimental replicates, which were sampled over a time course.

Steady-state physiology was assayed in a photobioreactor (PBR) that maintains constant optical density (turbidostasis) over a range of light intensities delivered by 630 and 680 nm light-emitting diodes (LEDs), as described previously (Melnicki et al., 2013). For maximal light penetration and steady-state illumination, cell cultures were maintained at 0.08 OD730 in A+ medium containing 0.9 g L−1 NH4Cl as the nitrogen source, and Tris was omitted as pH 7.5 was maintained independently. Cultures were held at 30°C and constantly sparged with N2 gas containing 1.3% CO2 at 4.1 L min−1. Doubling times were calculated by ln(2)/dilution rate, O2 evolution by percent air saturation, photophysiology by pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry, and biochemical composition were measured in WT, SA01, and ΔglgC strains at light intensities of 5/5 (33), 10/10 (66), 15/15 (99), 20/20 (132), 25/25 (165), 40/40 (264), 60/60 (396), 70/70 (462), 125/60 (610), and 170/60 (759) as incident 630/680 nm light each and (in parentheses) total spherical μmol m−2 s−1. A linear 2π incident sensor was used to measure individual wavelengths, and total spherical illumination was reported by a 4π sensor. Absorbance scans of total cell culture were measured over a 350–900 nm spectral range using a Shimadzu BioSpec 1601 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Non-transmitted fractions of 630 and 680 nm light were calculated using transmitted light values obtained in situ from the linear sensor and normalized to total spherical irradiance as described previously (Melnicki et al., 2013).

Chlorophyll a was measured by absolute methanol extraction of a 1-mL cell pellet and calculated as described previously (Meeks and Castenholz, 1971; Porra et al., 1989). Reducing carbohydrates (RCs) were measured as glucose equivalents by a colorimetric anthrone–sulfuric acid assay described previously (Meuser et al., 2012).

Dry cell weight (DCW) of batch cultures was measured from 2 mL of liquid culture concentrated by centrifugation. The cell pellet was washed once in 1 g L−1 Tris buffer (TB), resuspended in 1 mL TB, thoroughly dried at 80°C, and the dry weight of 1 mL TB subtracted to give DCW. From PBR cultures, DCW is represented as ash-free weight from 400 mL steady-state culture concentrated by centrifugation, resuspended in distilled water, dried at 105°C, and burned at 550°C for 1 h. Ash-free weight was calculated as mass lost between drying and burning.

Organic acids (OAs) were quantified by HPLC (Surveyor Plus, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using 0.45-μm filtered supernatant from −N cultures. A 25-μL sample was injected onto a 150 mm × 7.8 mm fermentation monitoring column (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 0.5 mL min−1 8 mM H2SO4 eluent, 45°C column operating temperature, and 50°C refractive index (RI) detector operating temperature, in parallel with a photodiode array detector for absorbance at 210 nm. A standard mix of acetate, pyruvate, succinate, α-ketoglutarate, and α-ketoisocaproate was used for quantification, and all samples were held at 10°C in a thermostated sample tray before injection.

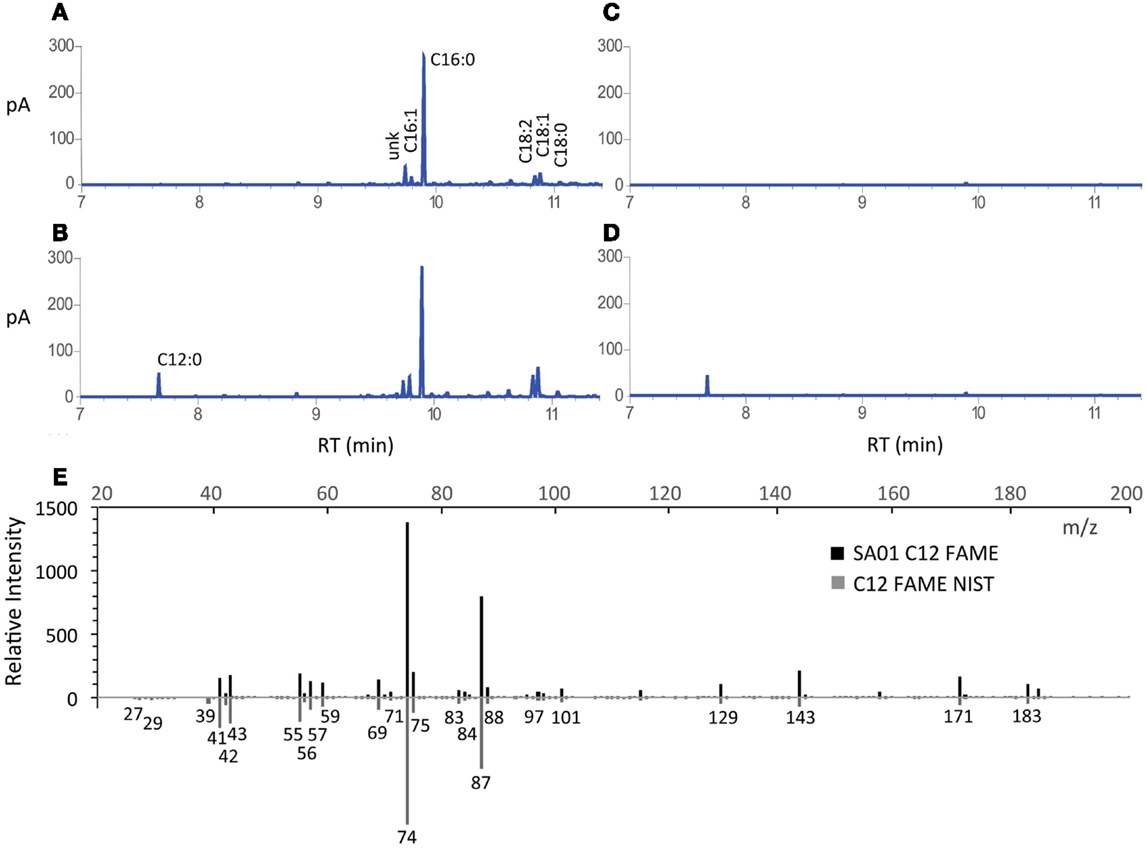

Fatty acyl content was measured as transesterifiable fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using an adapted method (Radakovits et al., 2011). Briefly, 0.5 mL of liquid culture was hydrolyzed and lipids saponified at 100°C for 2 h in 1 mL 95:5% v/v absolute methanol:0.8 g L−1 KOH (in H2O), after which 1.5 mL 94.2:5.8% v/v methanol:12N HCl was added for acid-catalyzed methylation at 80°C for 5 h. FAMEs were extracted into 1 mL n-hexane and the extract was analyzed using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (GC) and DB-5ms column with flame ionization detection (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A flow rate of 1.15 mL min−1 H2 carrier gas was used to separate FAMEs at 20°C min−1 to 230°C, held for 1 min, then 20°C min−1 to 310°C and held for 5 min. A standard mix of FAMEs was used for quantification and retention time correlation (37-component FAME mix, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Due to insufficient resolution between unsaturated C18 FAs, the combined contents of 18:1, 18:2, and 18:3 are reported as 18:n. The unknown (unk) compound that elutes prior to C16:1 was not included in FAME tabulations. A two-tailed t-test was performed to determine statistical significance (p-value). Lauric acid methyl ester (C12 FAME) was identified via mass spectral analysis conducted using a Varian 3800 GC and Varian 1200 quadrupole MS/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a Rxi-5ms column (30 mm × 0.25 mm; 0.25 μm film thickness) (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA). A flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1 He carrier gas was used to separate FAMEs at 20°C min−1 from 70 to 230°C for a 1-min hold, then 20°C min−1 to 310°C for a 5-min hold. Mass spectra were obtained after electron ionization at 70 eV. Results were compared to the known mass spectrum of C12 FAME (NIST Mass Spec Data Center, and Stein, 2015).

Variable chlorophyll fluorescence was measured using PAM fluorometry in a DUAL-PAM-100 system (Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) with a photodiode detector and RG665 filter (Schreiber, 1986). Red measuring light (620 nm) at the lowest power was pulsed at 1000 Hz during the dark and at 10,000 Hz during 635 nm actinic illumination at 98 μmol m−2 s−1. From PBR cultures, 3 mL was immediately transferred to a cuvette and fluorescence induction was measured with a programed script consisting of 15 s darkness, 30 s actinic illumination (O), application of a saturating pulse at 2000 μmol m−2 s−1 for 200 ms (J), 5 s of only far-red light (730 nm) (I), another 15 s of actinic light (P), and 30 s of darkness (S). Variable fluorescence observed during the O-J-I-P-S induction provided the basis to compare changes in the electron transport processes downstream of PSII. The effective quantum yield of PSII (YII’) was measured by transient fluorescence changes between “J” and “I” states. The estimated redox status of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool was determined by the rise from “I” to “P” level, normalized to the total variable fluorescence observed over this period, and subtracted from 1 (Chylla and Whitmarsh, 1989). Relative changes in electron transport downstream of the PQ pool were measured by P > > S quenching as the drop from “P” to “S” states relative to the variable fluorescence (Serrano et al., 1981). The relative dark rate of PQ oxidation was obtained from the declining slope of post-illumination fluorescence, calculated from between 10 and 20 s after the level had peaked (Ryu et al., 2003). Dark-adapted measurements were taken after cells were held in the dark for 20 min and then acclimatized in actinic light for 90 s before induction.

Nitrogen replete and nitrogen deplete batch cultures of WT, SA01, ΔglgC, and SA13 were analyzed over 48 h for chlorophyll a, DCW, FAME, RC, and OA. Cultures of C12-secreting strains developed a layer of surfactant bubbles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Foaming is visible atop culture medium of the lauric acid-secreting Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 strains SA01 and SA13.

Bulk biomass accumulation in nutrient replete batch cultures yielded an increase in chlorophyll a content of 12- to 15-fold over 48 h (Figure S1A in Supplementary Material), and DCW accumulated 4- to 5-fold (Figure S1C in Supplementary Material). In nitrogen-deplete cultures, growth attenuation was suggested by unchanging chlorophyll a content and DCWs that were within the range of error relative to inoculum DCWs over the time course (Figures S1B,D in Supplementary Material).

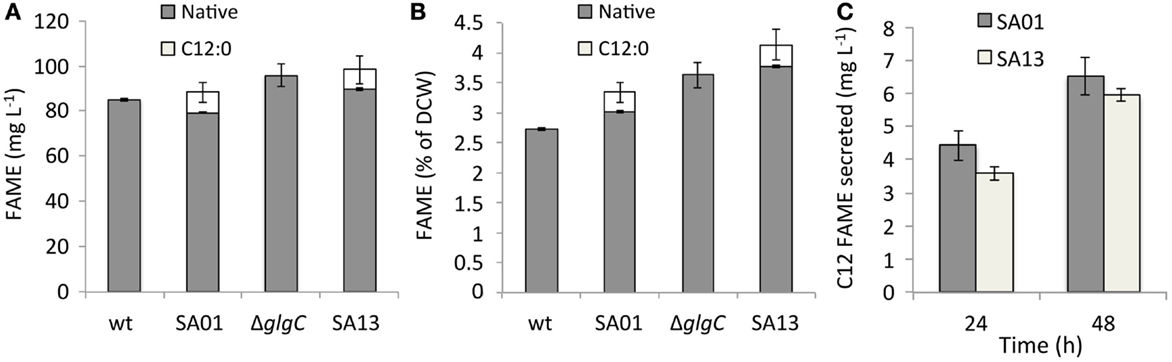

Secretion conferred by the LAS modification of transesterifiable C12 FAs into batch culture medium is demonstrated in Figures 2A–D. The identity of transesterified C12 was confirmed by GC–MS (Figure 2E). Lauric acid was detected neither during nitrogen starvation nor when fatB1 was expressed at a neutral locus without concurrent deletion of the putative AAS fadD (not shown). After 48 h, total FAME recovered from nutrient replete batch cultures reached 85.0 ± 0.7 (WT), 83.6 ± 4.5 (SA01), 95.3 ± 5.0 (ΔglgC), and 93.6 ± 6.1 (SA13) mg L−1 (Figure 3A), representing 3–5% of DCW (Figure 3B). Over 48 h, SA01 and SA13 generated, respectively, 9.1 ± 0.4 and 8.7 ± 0.6 mg L−1 C12, accounting for ~10% of total FAME (Table 2). C12 was recovered from culture medium of SA01 and SA13, respectively, at concentrations of 4.4 ± 0.4 and 3.5 ± 0.2 mg L−1 after the first 24 h, and 6.5 ± 0.6 and 5.9 ± 0.2 mg L−1 after 48 h (Figure 3C), an ~70% secretion level in both strains.

Figure 2. FAME profiles and identification of secreted FA from batch cultivation of WT and SA01 strains of Synechococcus sp. 7002. GC-FID chromatograms of FAME from representative (A) WT and (B) SA01 cell culture, and (C) WT and (D) SA01 cell-free supernatant. (E) Mass spectrum from GC–MS of SA01 FAME matching lauric acid methyl ester from the NIST database (C12 FAME NIST) (NIST Mass Spec Data Center, and Stein, 2015). The labeled standard is shown on the mirror axis. m/z, mass-to-charge ratio; pA, picoamps (detection current); RT, retention time.

Figure 3. FAME content of nutrient replete batch cultures after 48 h represented (A) by volume and (B) as a function of average dry cell weight (DCW). Native, endogenous fatty acyls; C12:0, heterologous lauric acid. (C) C12 FAME recovered from the medium of nutrient replete SA01 and SA13 cultures after 24 and 48 h. Error bars represent SD over four biological replicates.

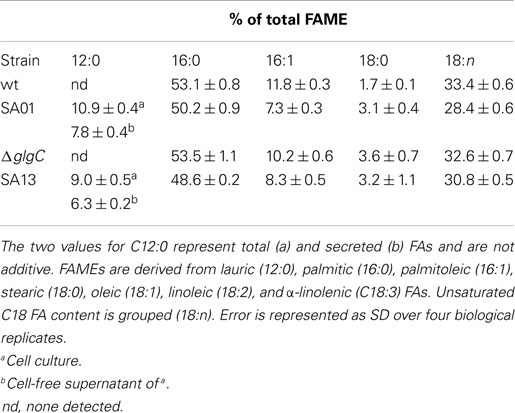

Table 2. Percent of total FAME by chain length from 48-h nutrient replete cultures, corresponding to Figure 3.

Distribution of FAME in 48-h nutrient replete cultures (Table 2) is consistent with previous studies of Synechococcus sp. 7002, including cumulative levels of unsaturated C18 FA (Kenyon, 1972; Sakamoto et al., 1997; Sakamoto and Bryant, 2002). Strains with the LAS modification showed diminished contents of 16:0 (p < 0.02), 16:1 (p < 0.001), and 18:n (p < 0.01). All three mutants contained twofold more 18:0 than WT. The ΔglgC mutant exhibited less 16:1 than WT (p < 0.02), while 16:0 and 18:n occurred at WT levels. In the AGPase-disrupted background, the LAS modification conferred a lower fraction (p < 0.02) of C12 relative to total FAME under the culturing conditions used.

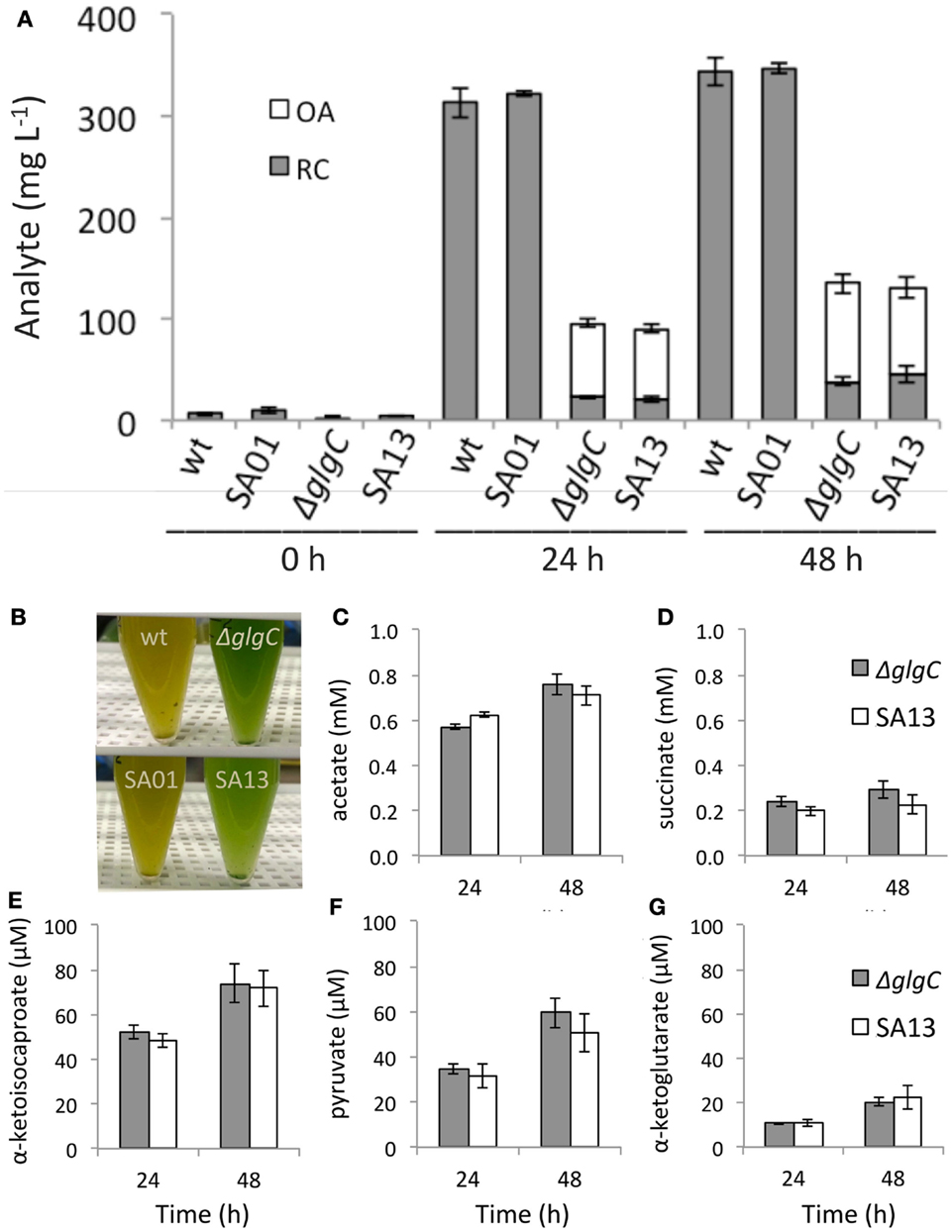

During nitrogen deprivation (−N), AGPase-disrupted strains accumulated substantially less RC than the WT background: over 24–48 h, RC on a culture volume basis reached 7–11% of WT levels in ΔglgC and 6–13% in SA13 (Figure 4A). Under the same conditions, RC comprised 30% of DCW in the WT background after 24 h and remained at this percentage over the next 24 h; whereas RC was accumulated to 4–5% of DCW in ΔglgC and 4–7% in SA13. The carbohydrate-deficient background secreted OA during −N to a total of 15% of DCW in both ΔglgC and SA13 after 24 and 48 h. Neither WT nor SA01 secreted detectable amounts of OA over the −N time course, and OAs were not detected in nutrient replete growth media (not shown). Combined, RC and OA (RC + OA) in the AGPase-disrupted strains accumulated under −N conditions to 19% of DCW. Relative to WT RC levels, RC + OA in ΔglgC cultures reached 31% after 24 h and 39% after 48 h, and SA13 reached 28 and 38% of WT, respectively (Figure 4A). While WT and SA01 cultures developed yellow coloration during −N, the AGPase-disrupted cultures did not (Figure 4B). Under the culturing conditions used, acetate was the most abundant OA secreted from the carbohydrate-deficient strains during −N, followed by succinate and α-ketoisocaproate (Figures 4C–E). Lesser concentrations of pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate were also observed (Figures 4F,G). Levels of OA secretion were not affected by the LAS modification.

Figure 4. (A) Reducing carbohydrate (RC) content and secreted organic acids (OAs) by volume in batch cultures of WT, SA01, ΔglgC, and SA13 during nitrogen deprivation at inoculation (0 h) and after 24 and 48 h. (B) Pigmentation differences between wild-type and carbohydrate-deficient backgrounds during nitrogen deprivation. (C–G) Individual OA secreted from ΔglgC and SA13 strains after 48 h of nitrogen deprivation. Error bars represent SD over four biological replicates.

At stable growth rate for each indicated light intensity in the LED-PBR, cultures of Synechococcus sp. 7002 WT, SA01, and ΔglgC were analyzed for RC, DCW, FAME, O2 evolution, doubling rate, and photophysiological characteristics. Growth rate and O2 production measurements for the same conditions were made previously using a separate cultivar of WT Synechococcus sp. 7002 (not shown), which demonstrate the reproducibility of PBR measurements (Work, 2014).

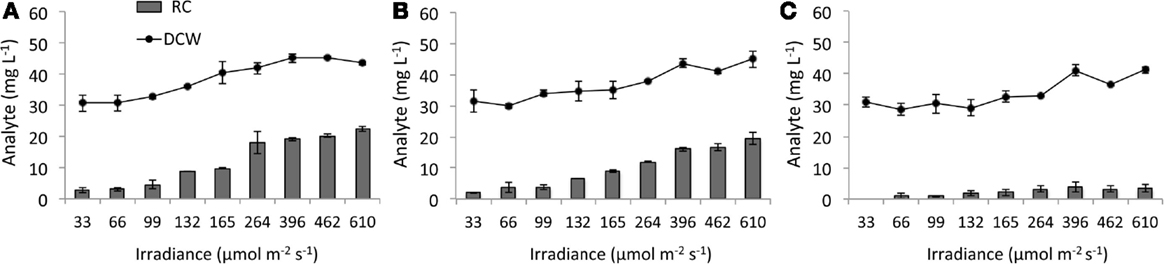

Disruption of AGPase inhibited RC accumulation while RC levels in the WT background increased with light intensity (Figure 5). At 610 μmol m−2 s−1, RC represented 51% of DCW in WT and 43% in SA01, but ΔglgC reached only 10% of DCW which occurred at 264 μmol m−2 s−1. Due to the dilute concentration of PBR cultures, FAMEs of C16:0 and C12:0 (C12 hereafter) were detectable but not quantifiable (<1 mg L−1). In representative PBR cultures at 396 μmol m−2 s−1, all observed C12 was recoverable from SA01 cell-free filtrate, and C12 was not detected in WT or ΔglgC (not shown) (Work, 2014).

Figure 5. Dry cell weight (DCW) and reducing carbohydrates (RCs) in steady-state PBR cultures. (A) WT, (B) SA01, and (C) ΔglgC strains of Synechococcus sp. 7002 with increasing 630/680 nm light intensity reported as spherical irradiance. The 33 μmol m−2 s−1 RC value for ΔglgC and 759 μmol m−2 s−1 biomass values were not available. Error bars represent SD over three samplings.

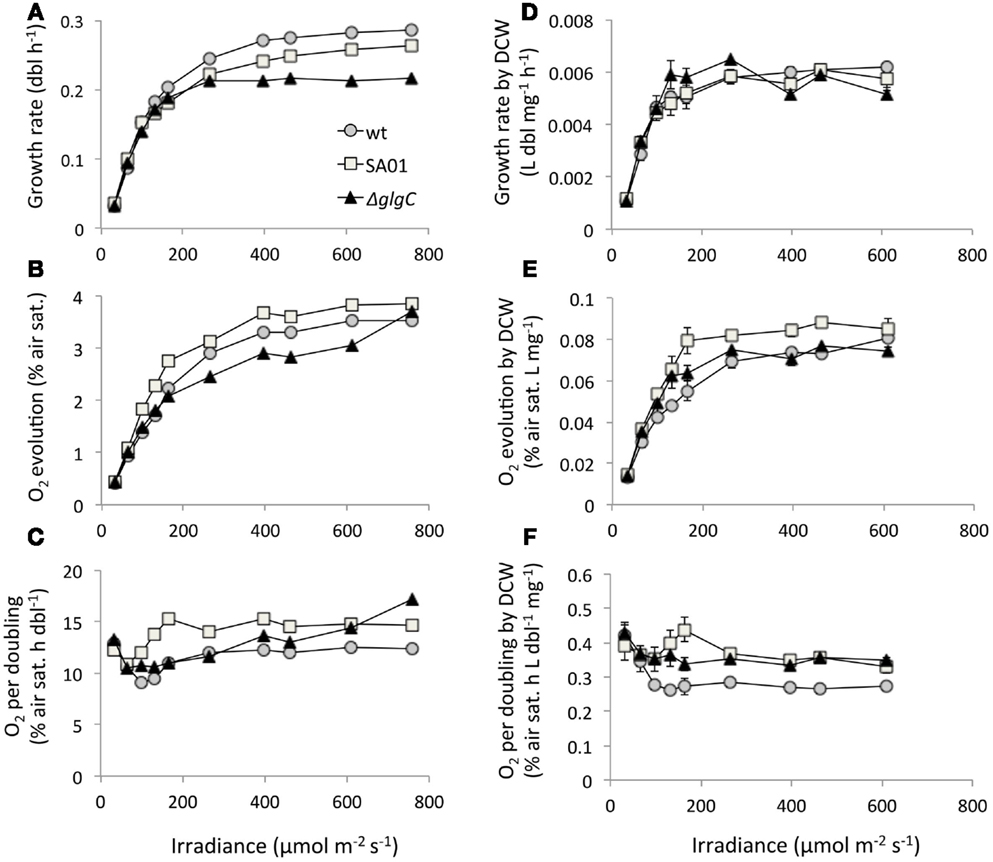

Minimum stable doubling times of 3.5 h (WT), 3.8 h (SA01), and 4.6 h (ΔglgC) were observed at 759 μmol m−2 s−1 in the WT background and at 462 μmol m−2 s−1 in ΔglgC (Figure 6A). Bulk O2 evolved by SA01 exceeded both WT and ΔglgC over the majority of light intensities tested (Figure 6B). On a per-doubling basis, ΔglgC produced O2 at levels similar to WT and in fact surpassed WT at 396 μmol m−2 s−1 and above (Figure 6C) despite diminished growth rates (Figure 6A). The doubling rate required per unit DCW was similar between all strains (Figure 6D). O2 evolved by ΔglgC was comparable to WT by bulk DCW (Figure 6E) but greater on the basis of DCW-normalized growth rate (Figure 6F). The uncoupling of O2 evolution from growth rate in ΔglgC at high irradiance was not observed when further normalized to DCW (Figure 6F). Despite attaining lower growth rates than WT at 264 μmol m−2 s−1 and above, SA01 exhibited consistently elevated O2 evolution by volume (Figure 6B), growth rate (Figure 6C), bulk DCW (Figure 6E), and DCW-normalized growth rate (Figure 6F).

Figure 6. Growth rates, O2 evolution, and dry cell weight (DCW) normalization of steady-state PBR cultures by light intensity. (A) Doubling rate, (B) bulk O2 evolution, (C) O2 production normalized to growth rate, (D) doubling rate per unit DCW, (E) O2 evolved on the basis of DCW, and (F) per-doubling O2 evolution normalized to DCW. Values for DCW at 759 μmol m−2 s−1 were not available. Light intensity is reported as spherical irradiance. Error bars represent SD over three samplings at each light intensity.

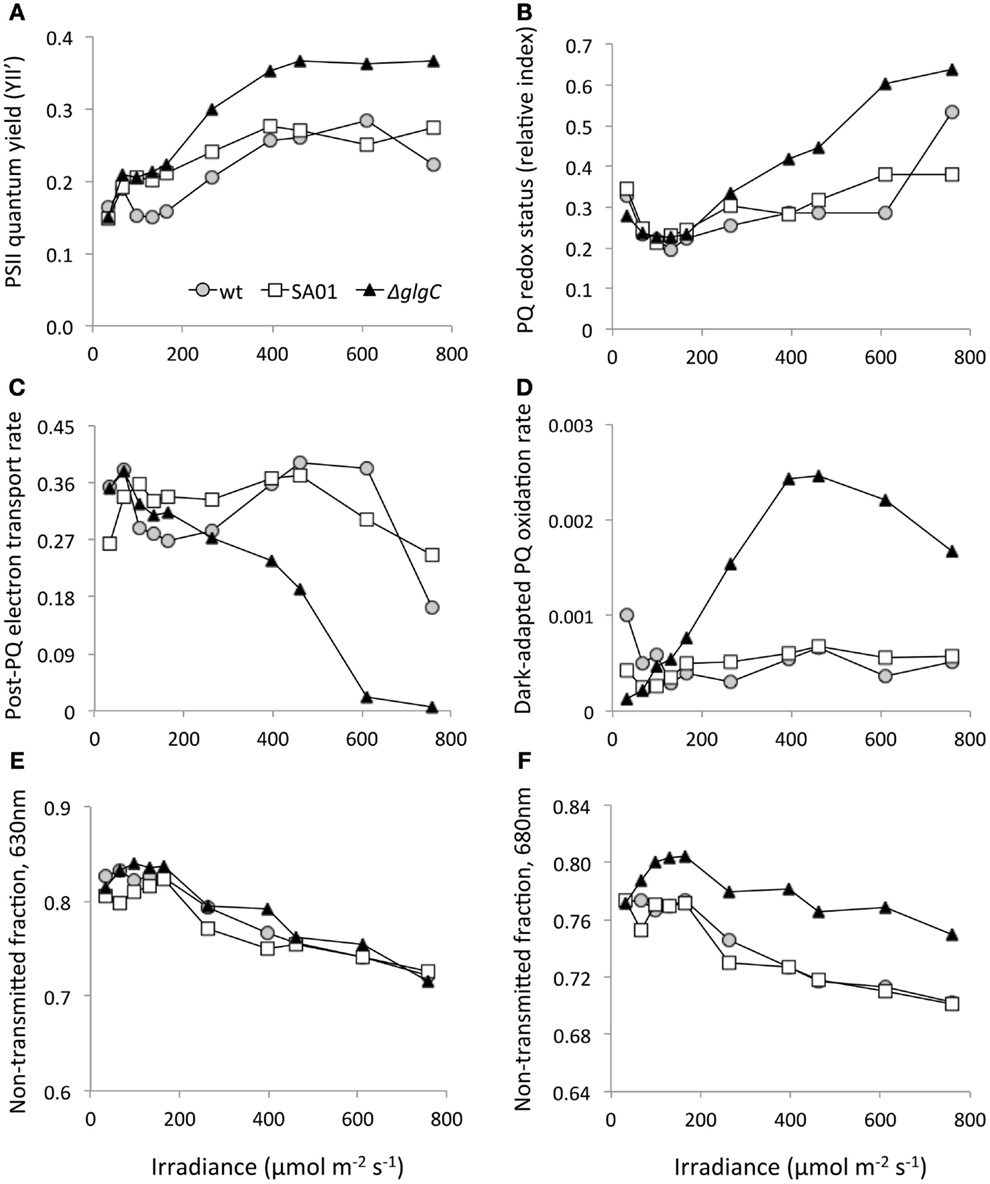

Photosynthetic electron transport appears to be altered by AGPase disruption (Figure 7). With increasing irradiance of the ΔglgC culture, a higher quantum yield of PSII was observed (Figure 7A), and the PQ pool became more reduced (Figure 7B) than the WT background. The rate of electron transport downstream of the PQ pool was also adversely affected by glgC disruption (Figure 7C), as less P > > S quenching occurred in this background with higher light. After dark adaptation, ΔglgC cultures exposed to 165 μmol m−2 s−1 and above exhibited more rapid rates of PQ oxidation in the dark (Figure 7D). The transmittance of 630 nm light by cell cultures was unaffected between strains (Figure 7E), but ΔglgC transmitted less 680 nm light than the WT background (Figure 7F) indicating more absorption or scattering by the strain at this wavelength.

Figure 7. Pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry from steady-state PBR cultures of WT, SA01, and ΔglgC over a range of light intensities. (A) PSII quantum yield (YII’). (B) Relative redox status of the PQ pool (more positive is more reduced). (C) Relative P > > S electron transport rates downstream of PQ. (D) Dark PQ oxidation rates in dark-adapted cultures. Non-transmitted fractions of (E) 630 nm and (F) 680 nm light by cell culture.

Derived from photosynthetically fixed CO2, FAs secreted by genetically engineered cyanobacteria have yielded up to 197 mg L−1 FFA by Synechocystis sp. 6803 and 131 mg L−1 FFA (6.5 mg L−1 d−1) by Synechococcus sp. 7002 (Liu et al., 2011; Ruffing and Jones, 2012; Ruffing, 2014). Secretion of 4.4 mg L−1 day−1 transesterifiable lauric acid (C12) from modified strains of Synechococcus sp. 7002 was achieved in batch cultures that grew at a similar rate to WT. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a common ingredient in soap, and the foam layer atop cultures secreting C12 suggests detergent activity. Under these conditions, C12 may accumulate in surface bubbles. Phase separation may be a consideration in applying photosynthetic FA secretion on an industrial scale, and actively removing C12 from cultures, for example by hexane overlay (Davies et al., 2014) or solid-state methods (Léonard et al., 2011), may create more favorable conditions for productivity.

Attenuating the synthesis of polymeric carbohydrates did not augment C12 production during normal growth, and attempts to direct metabolism to FAs by nitrogen starvation instead eliminated C12 altogether. The absence of C12 may be due to cessation of protein and/or lipid synthesis under these conditions, or, since a phycocyanin-related promoter is responsible for fatB1 expression, the gene may be downregulated in times of nitrogen stress, as phycobiliproteins can be degraded as an intracellular nutrient source (Sauer et al., 1999; Richaud et al., 2001). Additionally, the AGPase-disrupted batch cultures exhibited a non-bleaching phenotype when nitrogen-deprived, and as previously reported, higher absorbances in the 580–650 nm phycobilin range suggest that these proteins are not deconstructed for nutrients in this background as they are in WT (Guerra et al., 2013; Davies et al., 2014). Similar characteristics were described in carbohydrate-deficient mutants of Synechocystis sp. 6803 and Synechococcus elongatus 7942 (Carrieri et al., 2012; Gründel et al., 2012; Hickman et al., 2013).

Intracellular carbohydrate accumulation during nitrogen stress requires AGPase for glucose polymerization in Synechococcus sp. 7002 (Davies et al., 2014), S. elongatus PCC 7942 (Hickman et al., 2013), and Synechocystis sp. 6803 (Carrieri et al., 2012; Gründel et al., 2012), and energy spilling in the form of OA secretion was observed upon disruption of this function; and a similar outcome occurred with glycogen synthase deletions (Xu et al., 2013). Of the OA secreted by nitrogen-deprived ΔglgC and SA13 strains, pyruvate (C3), α-ketoglutarate (C5), and succinate (C4) are also gluconeogenic metabolites (Zhang and Bryant, 2011; Steinhauser et al., 2012). In S. elongatus 7942, α-ketoglutarate has been demonstrated as an effector of the nitrogen regulator NtcA (Vázquez-Bermúdez et al., 2001; Tanigawa et al., 2002). Possibly derived from protein degradation or metabolite redistribution, α-ketoisocaproate (C6) is a biosynthetic intermediate of the amino acid leucine and can be converted to acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate, which, along with pyruvate and acetate (C2), are direct precursors of FAs, terpenoids, higher alcohols, and reduced storage polymers such as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). Though biosynthetic enzymes for the latter two have not been identified in Synechococcus sp. 7002 (McNeely et al., 2010), secreted OA could be supplied to a capable organism by medium exchange (Niederholtmeyer et al., 2010) or co-cultivation (Contag, 2012; Therien et al., 2014).

Steady-state photoautotrophic doubling times of 3.5 h (WT), 3.8 h (SA01), and 4.6 h (ΔglgC) are close to the fastest observed in Synechococcus sp. 7002 (Ludwig and Bryant, 2012). Increased O2 production on the basis of DCW-normalized growth rate in both SA01 and ΔglgC may represent unidentified photosynthetic energy sinks (Badger et al., 2000; Nomura et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2013), which in SA01 could be related to the synthesis of secreted FA. Diminished photosynthetic productivity caused by AGPase disruption was evident, as ΔglgC reached maximum growth rate at a lower light intensity than WT. After growth rate saturation, dissipation of excess radiant energy appears to be accomplished in part by RC storage in the WT background. Restricting RC by AGPase disruption resulted in a more reduced, less oxidizable PQ pool indicating overreduction of the photosynthetic electron transport chain and/or the inability to utilize photosynthetic reductant. However, high rates of PQ oxidation by ΔglgC in the dark possibly demonstrate a respiratory or other continuous quenching function (Joët et al., 2002; Bailey et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2011). The severity of these redox alterations may lead to the protection of PSII in ΔglgC under irradiances at which WT and SA01 accumulated RC, as evidenced by O2 evolution decoupling, elevated PSII quantum yields, and more scattered or absorbed 680 nm light, perhaps owing in part to increased content of PSII or a phycobiliprotein such as phycocyanobilin that can absorb at 680 nm and is involved in free radical scavenging (Alvey et al., 2011; Ge et al., 2013). Demonstrating a robust capacity to manage excess light energy, Synechococcus sp. 7002 could be a promising organism in scaled systems (Dong et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010; Ludwig and Bryant, 2012), and efforts to reroute metabolic flux may identify enzyme targets through further investigation of carbon partitioning at high light in the present genetic backgrounds.

The planktonic cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. 7002 was engineered to convert photosynthate into biofuel precursors, which were naturally secreted from the cell. Lauric acid and OAs can be processed into diesel and alcohols or used as a carbon source for other organisms, and their recovery from culture filtrate avoids costly cell harvesting and lysis. Though redirection of carbohydrate-deficient metabolism toward FA synthesis was not effective under the present conditions, central metabolites for FA, terpenoid, and glucan biosynthesis were generated that potentially could be captured with further metabolic adjustments for redistribution into desired pathways.

The LAS module was constructed by VW, who also transformed and developed the LAS strains, performed batch cultivations and biochemical assays, and compiled this manuscript. MM performed PAM fluorometry measurements and contributed to PBR research design. EH designed, built, and operated the LED-PBR to generate O2 and dilution rate measurements, and assisted with dry weight measurements. FD performed mass spectral analysis, identified and helped quantify OAs, and assisted with quantitation of RCs. LK contributed to PAM fluorometry data collection. AB and MP were responsible for the project’s conception and provided laboratory resources. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors thank Shuyi Zhang and Dr. Donald A. Bryant for providing genetic materials and the ΔglgC mutant, and Dr. Roy Curtiss III for providing the fatB1 gene. We gratefully acknowledge the work of Gaozhong Shen to provide technical advice, Dr. Sarah D’Adamo for assistance with HPLC analysis, Dr. Robert Jinkerson for optimizing the anthrone protocol, and Dongxu (Tom) Li and Dr. Jinkerson for contributions to FAME methodology. This research was supported by the Genomic Science Program (GSP), Office of Biological and Environmental Research (OBER), U.S. Department of Energy, and is a contribution of the PNNL Biofuels Scientific Focus Areas.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fbioe.2015.00048/abstract

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; DCMU, 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea; LED, light-emitting diode; PCC, Pasteur culture collection.

Alvey, R. M., Biswas, A., Schluchter, W. M., and Bryant, D. A. (2011). Effects of modified phycobilin biosynthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1663–1671. doi: 10.1128/JB.01392-10

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Atsumi, S., Higashide, W., and Liao, J. C. (2009). Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1177–1180. doi:10.1038/nbt.1586

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Badger, M. R., von Caemmerer, S., Ruuska, S., and Nakano, H. (2000). Electron flow to oxygen in higher plants and algae: rates and control of direct photoreduction (Mehler reaction) and rubisco oxygenase. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1433–1446. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0704

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bailey, S., Melis, A., Mackey, K. R. M., Cardol, P., Finazzi, G., van Dijken, G., et al. (2008). Alternative photosynthetic electron flow to oxygen in marine Synechococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 269–276. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.01.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bentley, F., García-Cerdán, J., Chen, H.-C., and Melis, A. (2013). Paradigm of monoterpene (β-phellandrene) hydrocarbons production via photosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Bioenerg. Res. 6, 917–929. doi:10.1007/s00425-014-2080-8

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carrieri, D., Paddock, T., Maness, P.-C., Seibert, M., and Yu, J. (2012). Photo-catalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to organic acids by a recombinant cyanobacterium incapable of glycogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9457–9461. doi:10.1039/c2ee23181f

Cascon, V., and Gilbert, B. (2000). Characterization of the chemical composition of oleoresins of Copaifera guianensis Desf., Copaifera duckei Dwyer and Copaifera multijuga Hayne. Phytochemistry 55, 773–778. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00284-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chylla, R. A., and Whitmarsh, J. (1989). Inactive photosystem II complexes in leaves: turnover rate and quantitation. Plant Physiol. 90, 765–772. doi:10.1104/pp.90.2.765

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Contag, P. R. (2012). Organism co-culture in the production of biofuels. US patent application 20120124898.

Davies, F. K., Jinkerson, R. E., and Posewitz, M. C. (2015). Toward a photosynthetic microbial platform for terpenoid engineering. Photosyn. Res. 123, 265–284. doi:10.1007/s11120-014-9979-6

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Davies, F. K., Work, V. H., Beliaev, A. S., and Posewitz, M. P. (2014). Engineering limonene and bisabolene production in wild type and a glycogen-deficient mutant of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2:21. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2014.00021

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Denke, M. A., and Grundy, S. M. (1992). Comparison of effects of lauric acid and palmitic acid on plasma lipids and lipoproteins. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 56, 895–898.

Dong, C., Tang, A., Zhao, J., Mullineaux, C. W., Shen, G., and Bryant, D. A. (2009). ApcD is necessary for efficient energy transfer from phycobilisomes to photosystem I and helps to prevent photoinhibition in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1122–1128. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ducat, D. C., Avelar-Rivas, J. A., Way, J. C., and Silver, P. A. (2012). Rerouting carbon flux to enhance photosynthetic productivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2660–2668. doi:10.1128/AEM.07901-11

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Durrett, T. P., Benning, C., and Ohlrogge, J. (2008). Plant triacylglycerols as feedstocks for the production of biofuels. Plant J. 54, 593–607. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03442.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Elliott, L. G., Feehan, C., Laurens, L. M. L., Pienkos, P. T., Darzins, A., and Posewitz, M. C. (2012). Establishment of a bioenergy-focused microalgal culture collection. Algal Res. 1, 102–113. doi:10.1007/s12010-011-9199-x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Elliott, L. G., Work, V. H., Eduafo, P., Radakovits, R., Jinkerson, R. E., Darzins, A., et al. (2011). “Microalgae as a feedstock for the production of biofuels: microalgal biochemistry, analytical tools, and targeted bioprospecting,” in Bioprocess Sciences and Technology, ed. M.-T. Liong (New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 85–115.

Ferrari, M., Pagnoni, U. M., Pelizzoni, F., Lukeš, V., and Ferrari, G. (1971). Terpenoids from Copaifera langsdorfii. Phytochemistry 10, 905–907. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97176-0

Fore, S. R., Porter, P., and Lazarus, W. (2011). Net energy balance of small-scale on-farm biodiesel production from canola and soybean. Biomass Bioenergy 35, 2234–2244. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.02.037

Frigaard, N.-U., Sakuragi, Y., and Bryant, D. (2004). “Gene inactivation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 and the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum using in vitro-made DNA constructs and natural transformation,” in Photosynthesis Research Protocols, ed. R. Carpentier (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), 325–340.

Gao, Q., Wang, W., Zhao, H., and Lu, X. (2012). Effects of fatty acid activation on photosynthetic production of fatty acid-based biofuels in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Biotechnol. Biofuels 5, 1–9. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-5-17

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ge, B., Li, Y., Sun, H., Zhang, S., Hu, P., Qin, S., et al. (2013). Combinational biosynthesis of phycocyanobilin using genetically-engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 35, 689–693. doi:10.1007/s10529-012-1132-z

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gopinath, A., Sukumar, P., and Nagarajan, G. (2010). Effect of biodiesel structural configuration on its ignition quality. Int. J. Energ. Environ. 1, 295–306.

Gronenberg, L. S., Marcheschi, R. J., and Liao, J. C. (2013). Next generation biofuel engineering in prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 462–471. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.037

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gründel, M., Scheunemann, R., Lockau, W., and Zilliges, Y. (2012). Impaired glycogen synthesis causes metabolic overflow reactions and affects stress responses in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microbiology 158, 3032–3043. doi:10.1099/mic.0.062950-0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guerra, L. T., Xu, Y., Bennette, N., McNeely, K., Bryant, D. A., and Dismukes, G. C. (2013). Natural osmolytes are much less effective substrates than glycogen for catabolic energy production in the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. J. Biotechnol. 166, 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.04.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heifetz, P. B. (2000). Genetic engineering of the chloroplast. Biochimie 82, 655–666. doi:10.1016/S0300-9084(00)00608-8

Hickman, J. W., Kotovic, K. M., Miller, C., Warrener, P., Kaiser, B., Jurista, T., et al. (2013). Glycogen synthesis is a required component of the nitrogen stress response in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Algal Res. 2, 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2013.01.008

Hoekman, S. K., Broch, A., Robbins, C., Ceniceros, E., and Natarajan, M. (2012). Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 16, 143–169. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.143

Hu, Q., Sommerfeld, M., Jarvis, E., Ghirardi, M., Posewitz, M., Seibert, M., et al. (2008). Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: perspectives and advances. Plant J. 54, 621–639. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03492.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jansson, C. (2012). “Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for direct conversion of CO2 to hydrocarbon biofuels,” in Progress in Botany 73, eds U. Lüttge, W. Beyschlag, B. Büdel, and D. Francis (Berlin: Springer), 81–93.

Joët, T., Genty, B., Josse, E.-M., Kuntz, M., Cournac, L., and Peltier, G. (2002). Involvement of a plastid terminal oxidase in plastoquinone oxidation as evidenced by expression of the Arabidopsis thaliana enzyme in tobacco. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31623–31630. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203538200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kaczmarzyk, D., and Fulda, M. (2010). Fatty acid activation in cyanobacteria mediated by acyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase enables fatty acid recycling. Plant Physiol. 152, 1598–1610. doi:10.1104/pp.109.148007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kenyon, C. N. (1972). Fatty acid composition of unicellular strains of blue-green algae. J. Bacteriol. 109, 827–834.

Kilian, O., Benemann, C. S. E., Niyogi, K. K., and Vick, B. (2011). High-efficiency homologous recombination in the oil-producing alga Nannochloropsis sp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 21265–21269. doi:10.1073/pnas.1105861108

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kopetz, H. (2013). Renewable resources: build a biomass energy market. Nature 494, 29–31. doi:10.1038/494029a

Lee, Y.-K. (2001). Microalgal mass culture systems and methods: their limitation and potential. J. Appl. Phycol. 13, 307–315. doi:10.1023/A:1017560006941

Leite, G. B., Abdelaziz, A. E., and Hallenbeck, P. C. (2013). Algal biofuels: challenges and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 145, 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.02.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lennen, R. M., and Pfleger, B. F. (2012). Engineering Escherichia coli to synthesize free fatty acids. Trends Biotechnol. 30, 659–667. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.09.006

Léonard, P., Dandoy, P., Danloy, E., Leroux, G., Meunier, C. F., Rooke, J. C., et al. (2011). Whole-cell based hybrid materials for green energy production, environmental remediation and smart cell-therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 860–885. doi:10.1039/c0cs00024h

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, Q., Du, W., and Liu, D. (2008). Perspectives of microbial oils for biodiesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 80, 749–756. doi:10.1007/s00253-008-1625-9

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, Y., Han, D., Yoon, K., Zhu, S., Sommerfeld, M., and Hu, Q. (2013). “Molecular and cellular mechanisms for lipid synthesis and accumulation in microalgae: biotechnological implications,” in Handbook of Microalgal Culture, eds A. Richmond and Q. Hu (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.), 545–565.

Lindberg, P., Park, S., and Melis, A. (2010). Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria, using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab. Eng. 12, 70–79. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2009.10.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Litchfield, C., Miller, E., Harlow, R. D., and Reiser, R. (1967). The triglyceride composition of 17 seed fats rich in octanoic, decanoic, or lauric acid. Lipids 2, 345–350. doi:10.1007/BF02532124

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, X., Sheng, J., and Curtiss, R. III (2011). Fatty acid production in genetically modified cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 6899–6904. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103014108

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, X. (2010). A perspective: photosynthetic production of fatty acid-based biofuels in genetically engineered cyanobacteria. Biotechnol. Adv. 28, 742–746. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.05.021

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, X., Vora, H., and Khosla, C. (2008). Overproduction of free fatty acids in E. coli: implications for biodiesel production. Metab. Eng. 10, 333–339. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2008.08.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lubner, C. E., Grimme, R., Bryant, D. A., and Golbeck, J. H. (2009). Wiring photosystem I for direct solar hydrogen production. Biochemistry 49, 404–414. doi:10.1021/bi901704v

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ludwig, M., and Bryant, D. A. (2012). Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002 transcriptome: acclimation to temperature, salinity, oxidative stress, and mixotrophic growth conditions. Front. Microbiol. 3:354. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00354

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ma, F., and Hanna, M. A. (1999). Biodiesel production: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 70, 1–15. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00025-5

McDonald, A. E., Ivanov, A. G., Bode, R., Maxwell, D. P., Rodermel, S. R., and Hüner, N. P. A. (2011). Flexibility in photosynthetic electron transport: the physiological role of plastoquinol terminal oxidase (PTOX). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 8, 954–967. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.024

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McNeely, K., Xu, Y., Bennette, N., Bryant, D. A., and Dismukes, G. C. (2010). Redirecting reductant flux into hydrogen production via metabolic engineering of fermentative carbon metabolism in a cyanobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 5032–5038. doi:10.1128/AEM.00862-10

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meeks, J. C., and Castenholz, R. W. (1971). Growth and photosynthesis in an extreme thermophile, Synechococcus lividus (Cyanophyta). Arch. Mikrobiol. 78, 25–41. doi:10.1007/BF00409086

Melnicki, M. R., Pinchuk, G. E., Hill, E. A., Kucek, L. A., Stolyar, S. M., Fredrickson, J. K., et al. (2013). Feedback-controlled LED photobioreactor for photophysiological studies of cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 134, 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.079

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meuser, J. E., D’Adamo, S., Jinkerson, R. E., Mus, F., Yang, W., Ghirardi, M. L., et al. (2012). Genetic disruption of both Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [FeFe]-hydrogenases: insight into the role of HYDA2 in H2 production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 704–709. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Möllers, K. B., Canella, D., Jørgensen, H., and Frigaard, N.-U. (2014). Cyanobacterial biomass as carbohydrate and nutrient feedstock for bioethanol production by yeast fermentation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 64. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-7-64

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Niederholtmeyer, H., Wolfstädter, B. T., Savage, D. F., Silver, P. A., and Way, J. C. (2010). Engineering cyanobacteria to synthesize and export hydrophilic products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3462–3466. doi:10.1128/AEM.00202-10

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

NIST Mass Spec Data CenterStein, S. E., director. (2015). “Mass Spectra,” in NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database, Number 69, ed. P. J. Linstrom and W. G. Mallard (Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology). Available at: http://webbook.nist.gov

Nomura, C., Sakamoto, T., and Bryant, D. (2006). Roles for heme-copper oxidases in extreme high-light and oxidative stress response in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Arch. Microbiol. 185, 471–479. doi:10.1007/s00203-006-0107-7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ohlrogge, J., Savage, L., Jaworski, J., Voelker, T., and Postbeittenmiller, D. (1995). Alteration of acyl-acyl carrier protein pools and acetyl-CoA carboxylase expression in Escherichia coli by a plant medium-chain acyl-acyl carrier protein thioesterase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 317, 185–190. doi:10.1006/abbi.1995.1152

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Porra, R. J., Thompson, W. A., and Kriedemann, P. E. (1989). Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975, 384–394. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80347-0

Radakovits, R., Eduafo, P. M., and Posewitz, M. C. (2011). Genetic engineering of fatty acid chain length in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Metab. Eng. 13, 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2010.10.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Radakovits, R., Jinkerson, R. E., Darzins, A., and Posewitz, M. C. (2010). Genetic engineering of algae for enhanced biofuel production. Eukaryotic Cell 9, 486–501. doi:10.1128/EC.00364-09

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Richaud, C., Zabulon, G., Joder, A., and Thomas, J.-C. (2001). Nitrogen or sulfur starvation differentially affects phycobilisome degradation and expression of the nblA gene in Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2989–2994. doi:10.1128/JB.183.10.2989-2994.2001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rodolfi, L., Chini Zittelli, G., Bassi, N., Padovani, G., Biondi, N., Bonini, G., et al. (2009). Microalgae for oil: strain selection, induction of lipid synthesis and outdoor mass cultivation in a low-cost photobioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 102, 100–112. doi:10.1002/bit.22033

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rosgaard, L., de Porcellinis, A. J., Jacobsen, J. H., Frigaard, N.-U., and Sakuragi, Y. (2012). Bioengineering of carbon fixation, biofuels, and biochemicals in cyanobacteria and plants. J. Biotechnol. 162, 134–147. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.05.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ruffing, A. M. (2014). Improved free fatty acid production in cyanobacteria with Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 as host. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2:17. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2014.00017

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ruffing, A. M., and Jones, H. D. T. (2012). Physiological effects of free fatty acid production in genetically engineered Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109, 2190–2199. doi:10.1002/bit.24509

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ryu, J. Y., Suh, K. H., Chung, Y. H., Park, Y. M., Chow, W. S., and Park, Y. I. (2003). Cytochrome c oxidase of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 protects photosynthesis from salt stress. Mol. Cells 16, 74–77.

Sakamoto, T., and Bryant, D. A. (2002). Synergistic effect of high-light and low temperature on cell growth of the Δ12 fatty acid desaturase mutant in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Photosyn. Res. 72, 231–242. doi:10.1023/A:1019820813257

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sakamoto, T., Higashi, S., Wada, H., Murata, N., and Bryant, D. A. (1997). Low-temperature-induced desaturation of fatty acids and expression of desaturase genes in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152, 313–320. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10445.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sato, N., and Wada, H. (2010). “Lipid biosynthesis and its regulation in cyanobacteria,” in Lipids in Photosynthesis, eds H. Wada and N. Murata (Dordrecht: Springer), 157–177.

Sauer, J., Görl, M., and Forchhammer, K. (1999). Nitrogen starvation in Synechococcus PCC 7942: involvement of glutamine synthetase and NtcA in phycobiliprotein degradation and survival. Arch. Microbiol. 172, 247–255. doi:10.1007/s002030050767

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schmer, M. R., Vogel, K. P., Mitchell, R. B., and Perrin, R. K. (2008). Net energy of cellulosic ethanol from switchgrass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 464–469. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704767105

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schreiber, U. (1986). “Detection of rapid induction kinetics with a new type of high-frequency modulated chlorophyll fluorometer,” in Current Topics in Photosynthesis, eds J. Amesz, A. J. Hoff, and H. J. Gorkum (Dordrecht: Springer), 259–270.

Serrano, A., Rivas, J., and Losada, M. (1981). Nitrate and nitrite as ‘in vivo’ quenchers of chlorophyll fluorescence in blue-green algae. Photosyn. Res. 2, 175–184. doi:10.1007/BF00032356

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Soratana, K., and Landis, A. E. (2011). Evaluating industrial symbiosis and algae cultivation from a life cycle perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 6892–6901. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.04.018

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sorek, N., Yeats, T. H., Szemenyei, H., Youngs, H., and Somerville, C. R. (2014). The implications of lignocellulosic biomass chemical composition for the production of advanced biofuels. Bioscience 64, 192–201. doi:10.1093/biosci/bit037

Steinhauser, D., Fernie, A. R., and Araújo, W. L. (2012). Unusual cyanobacterial TCA cycles: not broken just different. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 503–509. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Suzuki, E., Ohkawa, H., Moriya, K., Matsubara, T., Nagaike, Y., Iwasaki, I., et al. (2010). Carbohydrate metabolism in mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 defective in glycogen synthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3153–3159. doi:10.1128/AEM.00397-08

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tanigawa, R., Shirokane, M., Maeda, S.-I., Omata, T., Tanaka, K., and Takahashi, H. (2002). Transcriptional activation of NtcA-dependent promoters of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 by 2-oxoglutarate in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4251–4255. doi:10.1073/pnas.072587199

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Therien, J. B., Zadvornyy, O. A., Posewitz, M. C., Bryant, D. A., and Peters, J. W. (2014). Growth of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in acetate-free medium when co-cultured with alginate-encapsulated, acetate-producing strains of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 154–161. doi:10.1186/s13068-014-0154-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vázquez-Bermúdez, M. A. F., Herrero, A., and Flores, E. (2001). 2-Oxoglutarate increases the binding affinity of the NtcA (nitrogen control) transcription factor for the Synechococcus glnA promoter. FEBS Lett. 512, 71–74. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02219-6

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Voelker, T. A., and Davies, H. M. (1994). Alteration of the specificity and regulation of fatty acid synthesis of Escherichia coli by expression of a plant medium-chain acyl-acyl carrier protein thioesterase. J. Bacteriol. 176, 7320–7327.

Wahlen, B. D., Willis, R. M., and Seefeldt, L. C. (2011). Biodiesel production by simultaneous extraction and conversion of total lipids from microalgae, cyanobacteria, and wild mixed-cultures. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 2724–2730. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.026

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Work, V. H. (2014). “Physiological surveys of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002,” in Metabolic and Physiological Engineering of Photosynthetic Microorganisms for the Synthesis of Bioenergy Feedstocks: Development, Characterization, and Optimization. [Doctoral dissertation], (Golden, CO: Colorado School of Mines), 108–125.

Work, V. H., Bentley, F. K., Scholz, M. J., D’Adamo, S., Gu, H., Vogler, B. W., et al. (2013). Biocommodities from photosynthetic microorganisms. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 32, 989–1001. doi:10.1002/ep.11849

Xu, Y., Alvey, R., Byrne, P., Graham, J., Shen, G., and Bryant, D. (2011). “Expression of genes in Cyanobacteria: adaptation of endogenous plasmids as platforms for high-level gene expression in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002,” in Photosynthesis Research Protocols, ed. R. Carpentier (New York, NY: Humana Press), 273–293.

Xu, Y., Guerra, T. L., Li, Z., Ludwig, M., Dismukes, G. C., and Bryant, D. A. (2013). Altered carbohydrate metabolism in glycogen synthase mutants of Synechococcus sp. 7002: cell factories for soluble sugars. Metab. Eng. 16, 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2012.12.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, S., and Bryant, D. A. (2011). The tricarboxylic acid cycle in cyanobacteria. Science 334, 1551–1553. doi:10.1126/science.1210858

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, X., Li, M., Agrawal, A., and San, K.-Y. (2011). Efficient free fatty acid production in Escherichia coli using plant acyl-ACP thioesterases. Metab. Eng. 13, 713–722. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2011.09.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhu, Y., Graham, J. E., Ludwig, M., Xiong, W., Alvey, R. M., Shen, G., et al. (2010). Roles of xanthophyll carotenoids in protection against photoinhibition and oxidative stress in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 504, 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2010.07.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: cyanobacteria, turbidostat photobioreactor, fatty acid secretion, metabolic overflow, organic acids, glgC, nitrogen deprivation, dodecanoic acid

Citation: Work VH, Melnicki MR, Hill EA, Davies FK, Kucek LA, Beliaev AS and Posewitz MC (2015) Lauric acid production in a glycogen-less strain of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 3:48. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00048

Received: 20 September 2014; Paper pending published: 06 October 2014;

Accepted: 25 March 2015; Published online: 24 April 2015.

Edited by:

Anne M. Ruffing, Sandia National Laboratories, USAReviewed by:

Xinyao Liu, Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC), Saudi ArabiaCopyright: © 2015 Work, Melnicki, Hill, Davies, Kucek, Beliaev and Posewitz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew C. Posewitz, Department of Chemistry and Geochemistry, Colorado School of Mines, 1500 Illinois Street, Golden, CO 80401, USA e-mail:bXBvc2V3aXRAbWluZXMuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.