94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anim. Sci., 11 November 2022

Sec. Animal Welfare and Policy

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2022.991042

This article is part of the Research TopicInsights in Animal Welfare and Policy: 2021View all 5 articles

Nature of reform to animal welfare legislation in Australia has commonly been attributed to increasing alignment with the ‘communities’ expectations’, implying that the community has power in driving legislative change. Yet, despite this assertion there has been no publicly available information disclosing the nature of these ‘expectations’, or the methodology used to determine public stance. However, based on previous sociological research, as well as legal reforms that have taken place to increase maximum penalties for animal welfare offences, it is probable that the community expects harsher penalties for offences. Using representative sampling of the Australian public, this study provides an assessment of current community expectations of animal welfare law enforcement. A total of 2152 individuals participated in the survey. There was strong support for sentences for animal cruelty being higher in magnitude (50% support). However, a large proportion (84%) were in favour of alternate penalties such as prohibiting offenders from owning animals in the future. There was also a belief that current prosecution rates were too low with 80% of respondents agreeing to this assertion. Collectively, this suggests a greater support for preventing animal cruelty through a stronger enforcement model rather than punishing animal cruelty offenders through harsher sentences. This potentially indicates a shift in public opinion towards a more proactive approach to animal welfare, rather than a reactive approach to animal cruelty.

As sentient beings (Mellor, 2019), animals are afforded legal protection through animal welfare legislation. Underpinning this protection are societal values which deem that animals’ interests in avoiding pain and suffering are morally relevant and worthy of consideration (Ohl and van der Staay, 2012). In practice, this means governments will generally legislate in the public interest when it comes to animal welfare (Nurse, 2016), making community expectations and opinions a major driver for legislative change. This has been observed in a number of Western countries, with several countries in the European Union reforming animal welfare legislation to align with public opinion (Bennett et al., 2002; Veissier et al., 2008; Vecchio et al., 2020), along with the United States (Mayer, 2002; MacArthur Clark et al., 2019) and the United Kingdom (Nurse, 2016) as some examples. These reform efforts are in concert with increasing public concern regarding matters of animal welfare, implying that policy makers are cognizant of changing public attitudes and willing to consider these attitudes when making domestic legislative decisions (Stimson, 1999; Erikson et al., 2002; Stimson, 2004). In line with this global trend, there have been a range of recent reforms to the state-based animal welfare acts (AWAs) in Australia. At least one driver for reform in this area appears to be a desire to align the objectives of the legislation with the expectations of the community (Geysen et al., 2010; Morton et al., 2018). This is evident from the referrals to public opinion made during the consultation process for animal welfare law reform efforts, some examples include:

“Extensive consultation took place with the general public and relevant organizations over the suggested amendments to this bill to ensure that appropriate measures for the welfare of animals were enforced through the proposed legislation … The proposed changes to this bill reflect the public’s concerns” (South Australian Legislative Council, 2007).

“The Bill is necessary to meet community expectations and provide a modern legislative framework for dealing with animal welfare issues … Such legislation is one means of demonstrating to the community that Queensland meets community and market expectations in relation to animal welfare” (Queensland Government, 2001b).

The state of Victoria has entered the early stages of a reform proposal for the relevant animal welfare act, with one goal being to “meet community expectations” (p.9; (Victorian Government, 2020b). Yet, in spite of these referrals to community expectations or concerns, the Australian jurisdictions often fail to disclose the nature of these expectations (Geysen et al., 2010), and when community engagement reports are released they often fail to divulge information on sampling and recruitment, making it impossible to assess the representativeness of the data from the community’s perspective, as an example see the Victorian Government’s engagement summary report (Victorian Government, 2021). In addition, findings from such reports are likely heavily subjected to social desirability bias, whereby the public provide responses they believe will be favored by others (Lai et al., 2021). Furthermore, in the absence of direct request to do an engagement survey, only a relatively small proportion of citizens will contact their local government representative (also known as Members of Parliament) when concerned about matters of animal welfare, with those that do often feeling most strongly about the need for legislative change (Tiplady et al., 2013). This leads to a further potential bias around the nature of community expectations.

A key focus of animal welfare law reform has been on penalties within acts, with referral to public opinion being cited as responsible for substantial increases to maximum penalties for offences in some state-based AWAs (Queensland Government, 2001a; South Australian Government, 2008; Victorian Government, 2012; Australian Capital Territory Government, 2019; Northern Territory Government, 2020; Victorian Government, 2020a). In spite of the previous criticism, this particular trend does align with community opinion found from sociological research conducted in the last two decades which has established that the community are largely in favor of harsher penalties, often in the form of custodial sentences (Allen et al., 2002; Taylor and Signal, 2009). Maximum penalties, in the forms of custodial sentences and monetary fines, have been argued to provide insight into the legislative intent behind AWA reforms enaction (Morton et al., 2020) in that reform efforts resulting in higher maximum penalties implies the intention of parliaments to “get tough” on animal welfare offenders, and sends a message to the community that animal cruelty will not be tolerated (Morgan, 2002; Sankoff, 2005). However, based on the limited case analyses in Australia it is likely that the maximum penalty increases are failing to translate into increased court sentences (Morton et al., 2018). Parliamentary setting of maximum penalties and sentencing in court are two separate processes; parliamentarians set the maximum penalties laid out in acts, and the court system, through judicial officers, will determine the specific sentence within the set penalty range. Therefore, on the surface it would appear that the court system is failing to consider the legislative intent, hence failing to meet ‘community expectations’. Yet on deeper analysis the complexities of case sentencing become apparent. Courts are bound by rules; they are bound by previous court determinations, known as the doctrine of precedent (Cook et al., 2009), and must adhere to sentencing principles outlined in sentencing legislation (Schreiner, 2005). These rules prevent the overuse of the publicly favored prison sentences (through sentencing legislation) and favor an incremental and slow progression in change to penalties (through the doctrine of precedent), thus generally preventing large increases to the magnitude of penalties handed down for offences. Hence, the complexities of case sentencing make it impossible to produce the immediate jump in penalties that the community may be expecting.

There is evidence that judicial officers are aware of legislative intent behind increasing maximum penalties, for example a South Australian Magistrate commented regarding sentencing for the case of RSPCA SA v Crisp (2010):

“…where the maximum financial penalty was raised from $10,000 to $20,000, the fact that Parliament did that reflects the concern of the community as to the ill treatment of animals. It is a matter which the community … regard as being something that should be severely punished”

However, as suggested by a New South Wales Magistrate, the potential of alignment between community expectations and court determinations is debatable (Schreiner, 2005). The criminal justice system will likely always lag behind community expectations. Given this lag, as Sankoff (2008) noted it is important to measure a social justice movement’s progress to ensure its foundations are still applicable to today’s society. Considering there is no publicly available information on the exact nature of the Australian communities’ expectations, upon which parliamentarians have come to rely, this study herein assumes that the ‘expectations’ relate to harsher penalties for animal cruelty offences. This will practically be reflected in increases in the length of custodial sentences and the monetary value of fines. Using representative sampling of the Australian public, this study provides quantitative data on current community opinions towards penalties for animal welfare offences. As a secondary aim, given the uniqueness of the AWA enforcement model whereby a non-governmental organization (NGO) carries the bulk of the enforcement burden (Morton et al., 2020) in lieu of individual government-funded agencies (ie. state or federal police forces), we also gathered public opinion on multiple components of this enforcement model. This included public reporting of animal cruelty and inspectorate investigation of reports. The findings of this research allow us to gauge alignment between AWA reform efforts and current community expectations and provide information on the Australian public’s viewpoints to inform policy makers in the future.

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide (H-2020-241) and conducted in accordance with the provisions of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Health and Medical Research Council, Updated July 2018). All participants provided informed consent prior to taking the survey and had the option to withdraw their responses prior to completion.

An online survey was developed and distributed nationally throughout Australia using the software and distribution company, Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants were recruited from Qualtrics’ actively managed research panels, whereby they were invited to participate via email or opted to involve themselves after signing into a panel portal. Email invitations were kept general without the inclusion of specific details about the survey’s content to avoid any self-selection bias. All invitations included an anonymous link to the online survey, as well as informing the participants that the survey was for research purposes only and the approximate length of time for completion of the survey.

A representative sample size of the adult (18 years old and over) Australian population was calculated based on a population estimate of 20 million with a 95% confidence interval and a 2.0% margin of error. This equated to a sample size of 2401 participants. In order to obtain a representative sample of the Australian population, participants were selected and balanced based on predetermined demographic quotas relative to the overall Australian adult population for age, gender and location from each state and territory in Australia. Participants were only eligible to participate if they were over the age of 18 years and a current Australian resident. Data collection spanned eight weeks from 18 June 2021 to 20 August 2021. A total of 2534 responses were collected and reviewed by Qualtrics for completeness and authenticity, which deemed 2152 responses suitable for analysis. The completion rate of the survey was 84.9%.

The survey questionnaire was designed to investigate public opinion towards discrete components of the animal welfare law enforcement process, beginning with the reporting stage and ending with prosecution outcomes. The survey was broken into four components (refer Supplementary file). The first component included 13 screener questions, which included detail of respondents’ age, gender, state/territory location within Australia, ethnic origin, education and occupation, experience in the legal field and animal ownership status. The remaining survey components contained 22 opinion-based questions on the animal law enforcement process, these questions were separated into three discrete components: reporting of animal cruelty, case investigation, and the court process.

Questions pertaining to reporting cruelty focused on public opinion on common terminology used in AWAs such as ‘animal’ and ‘cruelty’, as well as ranking their overall confidence in reporting to the correct authority. Investigation related questions considered public opinion of enforcement authorities, educational interventions in lieu of prosecution, and overall opinion on nationwide investigation and prosecution rates from RSPCA Australia’s 2019/2020 annual statistics (RSPCA, 2021). Finally, the court process questions focused on public opinion surrounding the imposition of penalties, the seriousness of animal cruelty per utility group (companion, farm, native and pest), prohibition orders and overall opinion regarding sentencing outcomes. Questions were designed to elicit public opinion, rather than knowledge, and were presented in the form of multiple-choice questions or Likert scale responses. Time to complete the survey averaged 8.5 minutes.

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Data were cleaned to remove any incomplete responses. Descriptive statistics were used to visualize spread of responses. Chi-squared tests were used to examine associations between responses and demographic groups for categorical data. Normality tests identified the continuous data as non-parametric. For this reason Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U tests were used to examine the association between reporting confidence responses and demographic groups (age, gender, location, and animal ownership). As there were more than two categorical independent groups within age demographics, a Kruskal-Wallis test was applied, whereas Mann Whitney U tests were utilized for the remaining demographic variables as there were only two groups within each. Participants that responded with ‘prefer not to say’ for any of the demographic questions were removed from the dataset when analyzing for demographic associations, hence each variable has a different sample size.

A total of 2152 individuals participated in the survey, with 53.5% identifying as female, 44.1% as male, and 2.4% as a third gender or other. Participant age ranges were 18-34 years old (35.8%), 35-44 years old (17.9%), 45-54 years old (15.0%) and 55+ years old (31.3%). The majority of participants lived with or owned an animal (66.0%) and described their residential location as urban (74.1%), with the remainder as rural (20.5%) or undisclosed (5.4%). This survey collected data from all Australian states and territories, with 32.0% of responses from New South Wales, 26.0% from Victoria, 20.1% from Queensland, 9.5% from Western Australia, 7.3% from South Australia, and the remaining 5.1% combined between Tasmania, Northern Territory, and Australian Capital Territory.

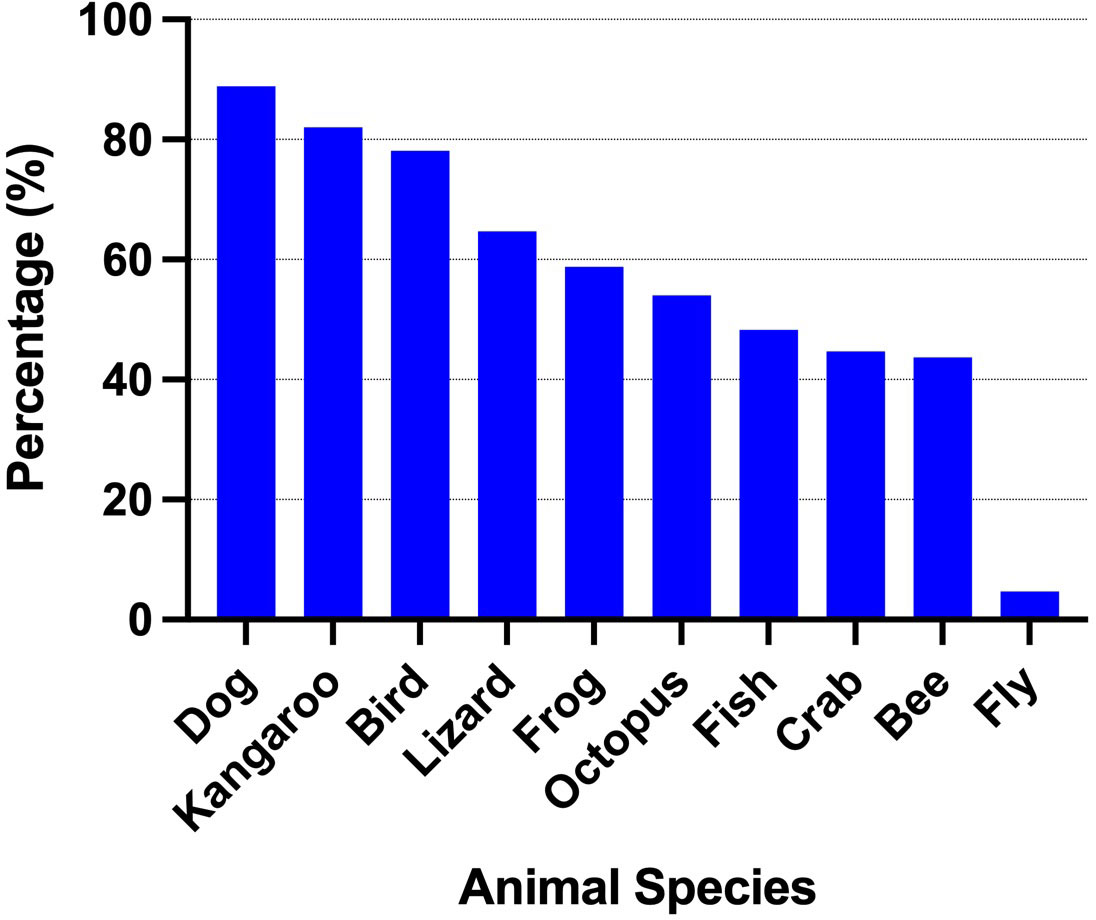

From the entire sample (n=2152), 87.5% of participants when asked at the commencement of the survey believed animal cruelty was illegal, whereas 6.8% believed it was not illegal and 5.7% did not know. When asked what species of animals should be awarded legal protection from cruelty (Figure 1), the most common responses included the mammalian species, being dogs (88.9%) and kangaroos (82.0%). Birds (78.1%), reptiles (lizards; 64.7%) and amphibians (frogs; 58.8%) were common responses, followed by aquatic species, being cephalopods (octopuses; 54.0%), fish (48.3%) and crustaceans (crabs; 44.7%). The two invertebrate species included in the question evoked vastly different responses, with 43.7% agreeing bees should be protected from cruelty, in comparison to the 4.7% who selected flies. Participants were not informed that animal welfare laws commonly define ‘animal’ as any member of the vertebrate family (excluding human beings), with variable inclusion of fish, cephalopods and crustaceans dependent on the jurisdiction (Morton et al., 2021).

Figure 1 Percentage of respondents that believed named species should be awarded protection from cruelty. As multiple response options were available for participants, “all the above” responses were removed from the sample, giving a sample size of n=954. “Which of the following species do you think should be protected from cruelty?”.

Participants believed it was most important for the criminal justice system to take animal cruelty seriously when the victim was a companion animal (65.0% extremely important; 22.8% very important) (Figure 2). Native animal cruelty was also ranked highly within the sample (61.8% extremely important; 23.0% very important), followed by farm animal cruelty (49.5% extremely important; 29.2% very important). Australian pest species (e.g., rats and camels) ranked lowest (25.8% extremely important; 25.6% very important), with a cumulative percentage of 27.9% participants selecting it was of minimal importance to take cruelty towards them seriously (14.4% slightly important; 13.5% not at all important).

Figure 2 Percentage ranking of importance for the legal system to take cruelty seriously based on animal species involved (n=2152). “How important do you think it is for the legal system to take animal cruelty seriously when the animal is a [companion, native, farm, or pest animal]?”.

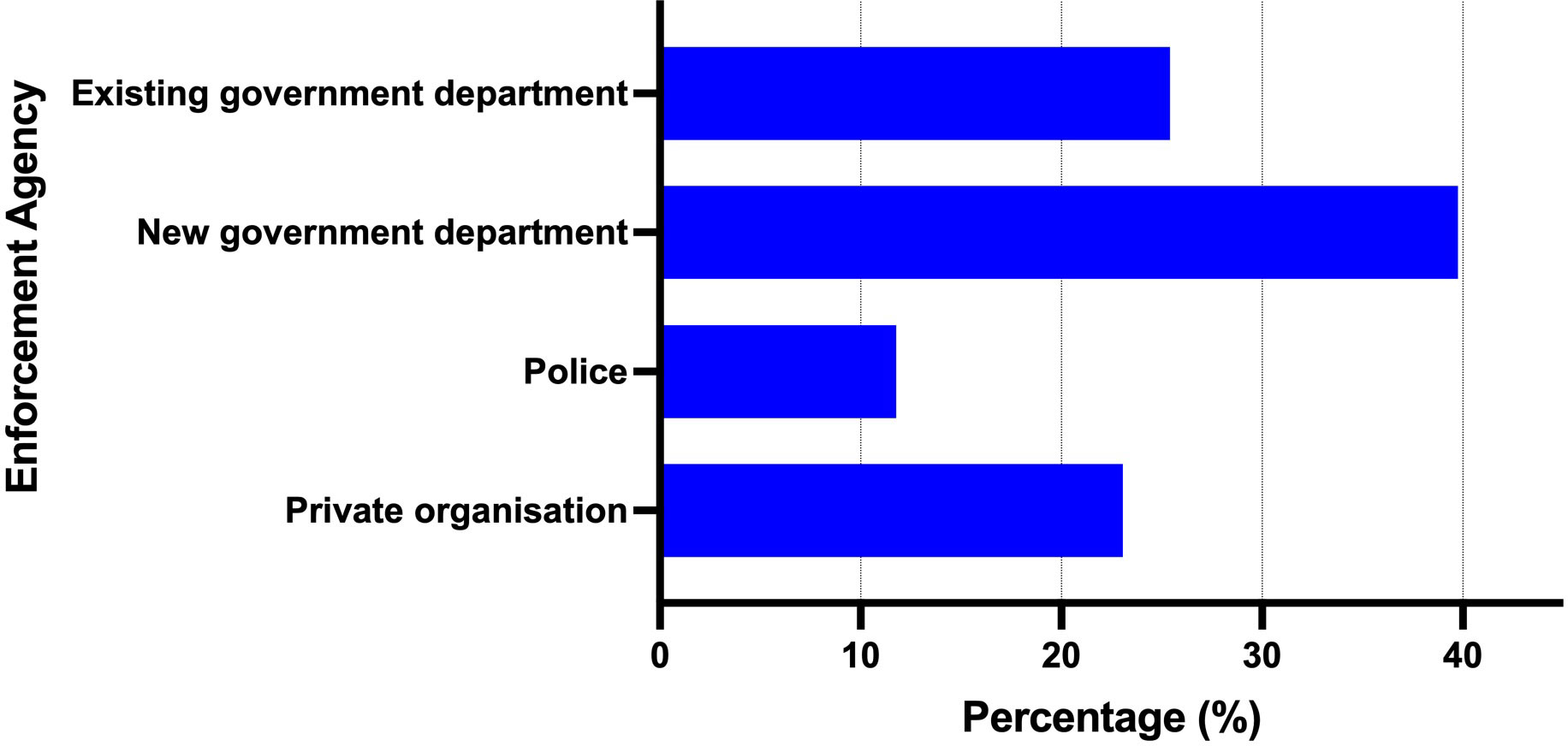

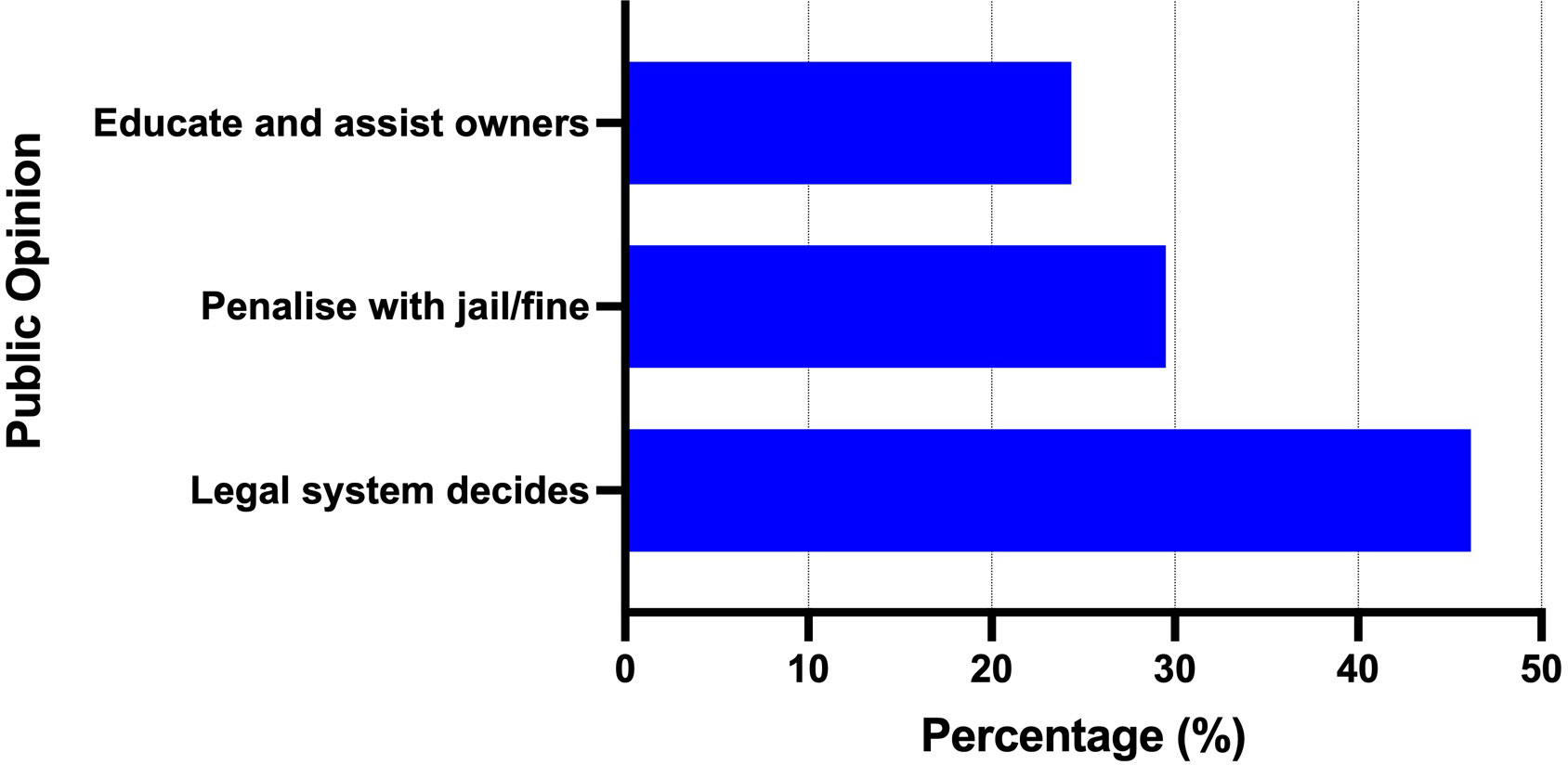

When asked which enforcement agency would be best suited to enforce animal welfare law (Figure 3), the most common response from participants was a new government department dedicated solely to animal welfare enforcement (39.8%). There was a slight difference between preference for an existing government agency (25.4%) or a private charitable organization (23.0%) to carry out enforcement. Police were the least selected option (11.8%). The questionnaire did not inform participants that the common enforcement agency in Australia is a private charitable organization. In terms of acceptable outcomes in the event of cruelty, the majority of participants believed that officers of the legal system should decide the outcome of the case (46.1%), rather than having a direct preference towards punitive action in the form of custodial sentences or monetary fines (29.5%) (Figure 4). Participants also had the option to select an educative response, where the enforcement agency works with the owners to improve the situation, rather than proceeding with prosecution (24.4% response).

Figure 3 Enforcement agency preferences of respondents (n=2152). “In your opinion, which organization should enforce animal welfare law?”.

Figure 4 Percentages of responses towards alternative enforcement outcomes for animal cruelty investigations (n=2152). “Do you think owners should be educated or punished when animal welfare issues occur (e.g. not taking your sick animal to the vet)?”.

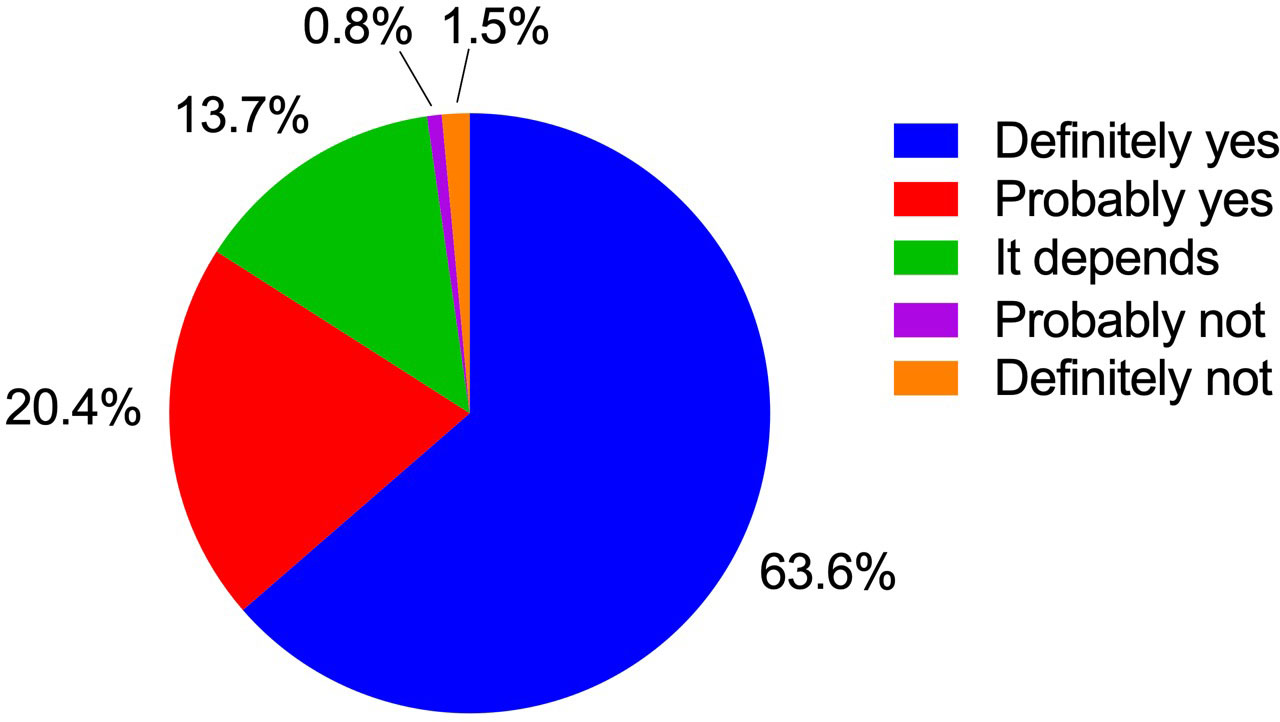

Participant responses towards the use of court orders prohibiting persons found guilty of animal cruelty from owning animals were positive (Figure 5), with the majority of participants (63.6%) strongly in favor of prohibition orders. A large percentage of participants (20.4%) were also in favor of prohibition orders; however, they selected the less strongly worded answer being ‘probably yes’, rather than ‘definitely yes’. A smaller group (13.7%) believed that prohibition order use should depend on the specific case of animal cruelty, whilst cumulatively 2.3% of participants were not in favor of prohibition orders. Participants were not informed that prohibition orders are commonly used at the discretion of the sentencing court in Australia for offenders found guilty of an animal welfare offence.

Figure 5 Reponses (%) towards ban of animal ownership when offenders are found guilty of animal cruelty (n=2152). “If someone was found guilty of animal cruelty, do you believe they should be banned from owning animals?”.

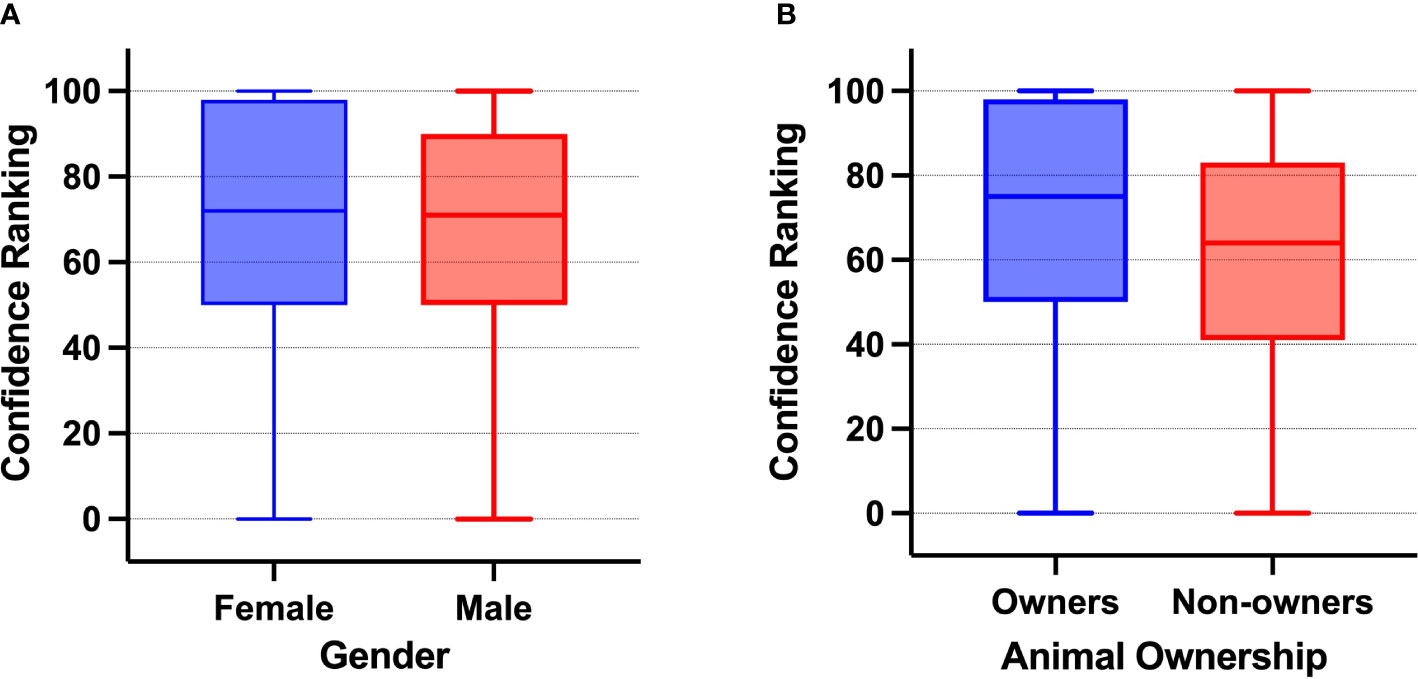

Participants ranked their confidence in reporting animal cruelty to the appropriate agency on a 100-point scale (with 0 being not confident at all and 100 being extremely confident). Given the non-parametric nature of the data, the median ranking was 71, with an interquartile range of 42 (Q1 = 50; Q3 = 92). Confidence rankings were analyzed against demographic variables age, gender, location, and animal ownership (Table 1), where participant gender and animal ownership status had a significant relationship with reporting confidence.

A Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to determine if there were differences between genders (male/female), location (urban/rural) and animal ownership (yes/no). The level of confidence of participants in reporting animal cruelty was highly significant between participants that owned an animal compared to those that didn’t (P<0.001) (Figure 6A). The median responses differed greatly between owners (median = 75; IQR = 48) and non-owners (median = 64; IQR = 42). Animal owners selected rankings of 100 more frequently than non-owners causing an increased interquartile range. Gender was significant (p-value = 0.046), and the median responses between males (median = 71) and females (median = 72) only differed by a single ranking score (Figure 6B). The interquartile range for the female responses (IQR = 48) was slightly higher in comparison to the males (IQR = 40), which was due to a greater number of females selecting ranking scores of 100, in comparison to males. There was no significant difference between those respondents that live in an urban or rural location (P=0.404).

Figure 6 Box plots showing the significant relationship between reporting confidence and the demographic variables of gender (A) and animal ownership (B); p-value < 0.05. “Do you feel confident that you know how and where to report animal cruelty?”.

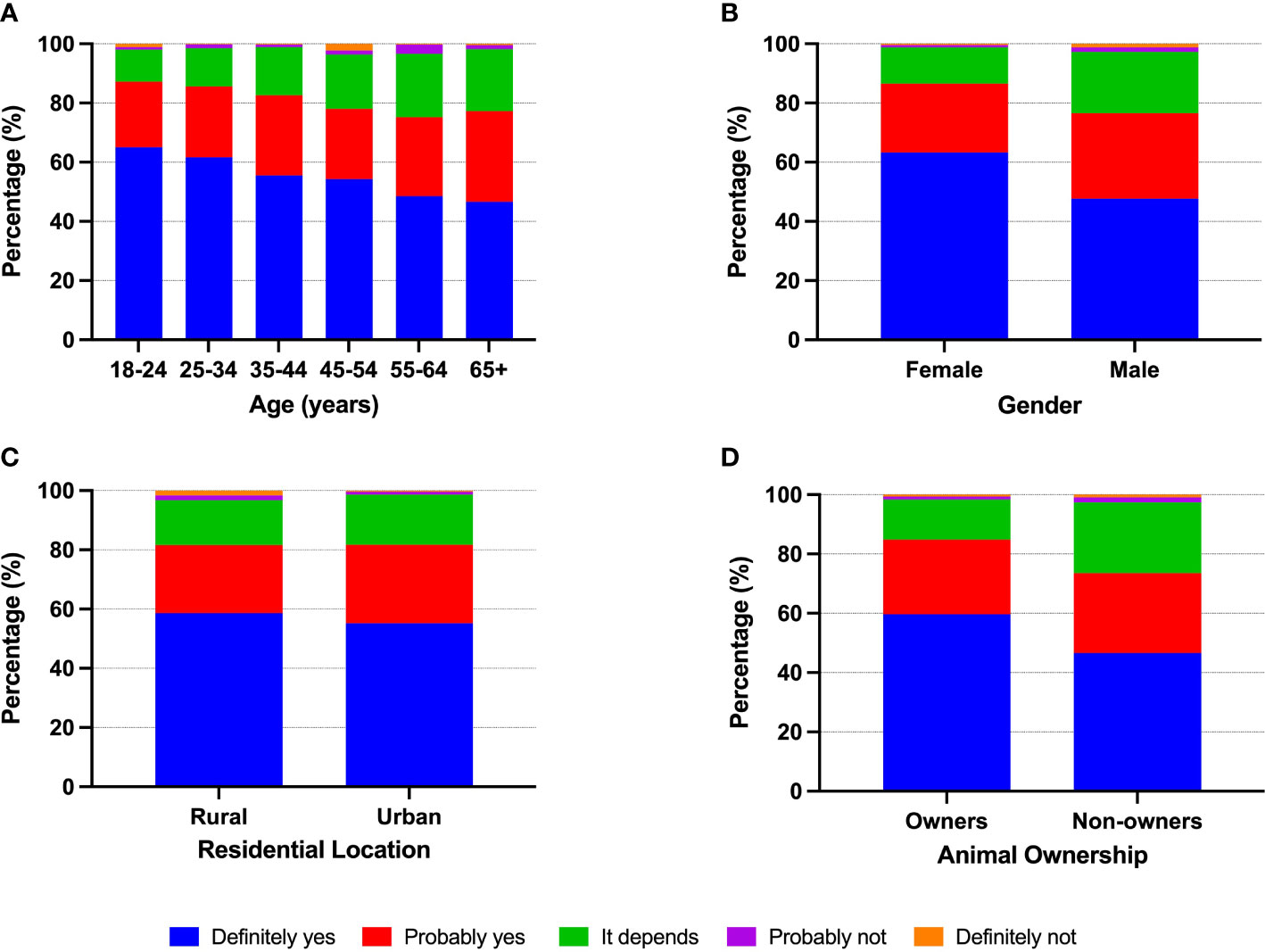

Overall, 79.6% of participants believed that more investigations of animal cruelty should be prosecuted in court, whilst 17.2% believed it depended on the circumstances of the case and 3.2% responding with no change was needed. Participants were informed that in the 2019/2020 financial year a total of 58,487 investigations were conducted nationally in Australia by state-based RSPCAs and of those investigations 376 prosecutions were finalized in court. This information was based on the RSPCA Australia’s 2019/2020 annual statistics (RSPCA, 2021). Reponses were analyzed against demographic variables with the finding that all variables had a significant relationship with a desire for prosecution (Table 2). The nature of the associations are elaborated on below (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Percentages showing the significant relationship between opinion on prosecution rates and the demographic variables of age (A), gender (B), residential location (C) and animal ownership (D); p-value < 0.05. “In your opinion do you think more animal welfare investigations should go to court?” based on a 0.6% prosecution rate from 2019/2020 financial year data.

A chi-square test of association was conducted to determine whether there was a significant association between prosecutorial action, and age, gender, location and animal ownership. Gender differences around prosecutorial opinion were found to be highly significant (Table 2; P < 0.001; Figure 7B), with females responding more commonly with ‘definitely yes’ (female 63.3%; male 47.7%) and males responding more neutrally with ‘it depends’ (female 12.3%; male 20.8%). There was a statistically significant association with age group where the 18-24 year age group had the highest percentage of ‘definitely yes’ (65.0%), whilst ages 65+ years had the lowest percentage (46.6%). However, when comparing the ‘definitely yes’ and ‘probably yes’ responses, all ages had a response rate of approximately 80%. A response of ‘it depends’ was more common amongst older participants, whilst all ages only had a small proportion of ‘no’ responses (approximately 2.0% of each age range). Finally, animal owners responded more strongly (definitely yes 59.7%) than non-owners (definitely yes 46.6%), and non-owners had a high proportion of ‘it depends’ responses (owners 13.5%; non-owners 23.9%).

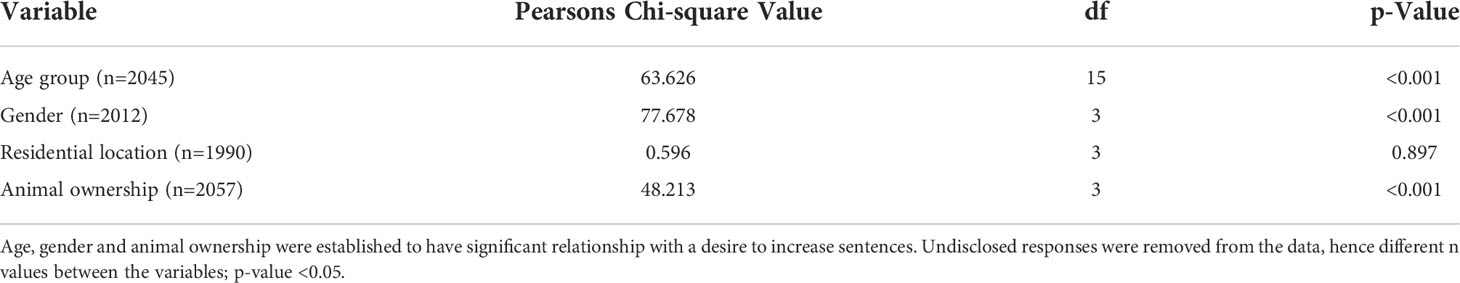

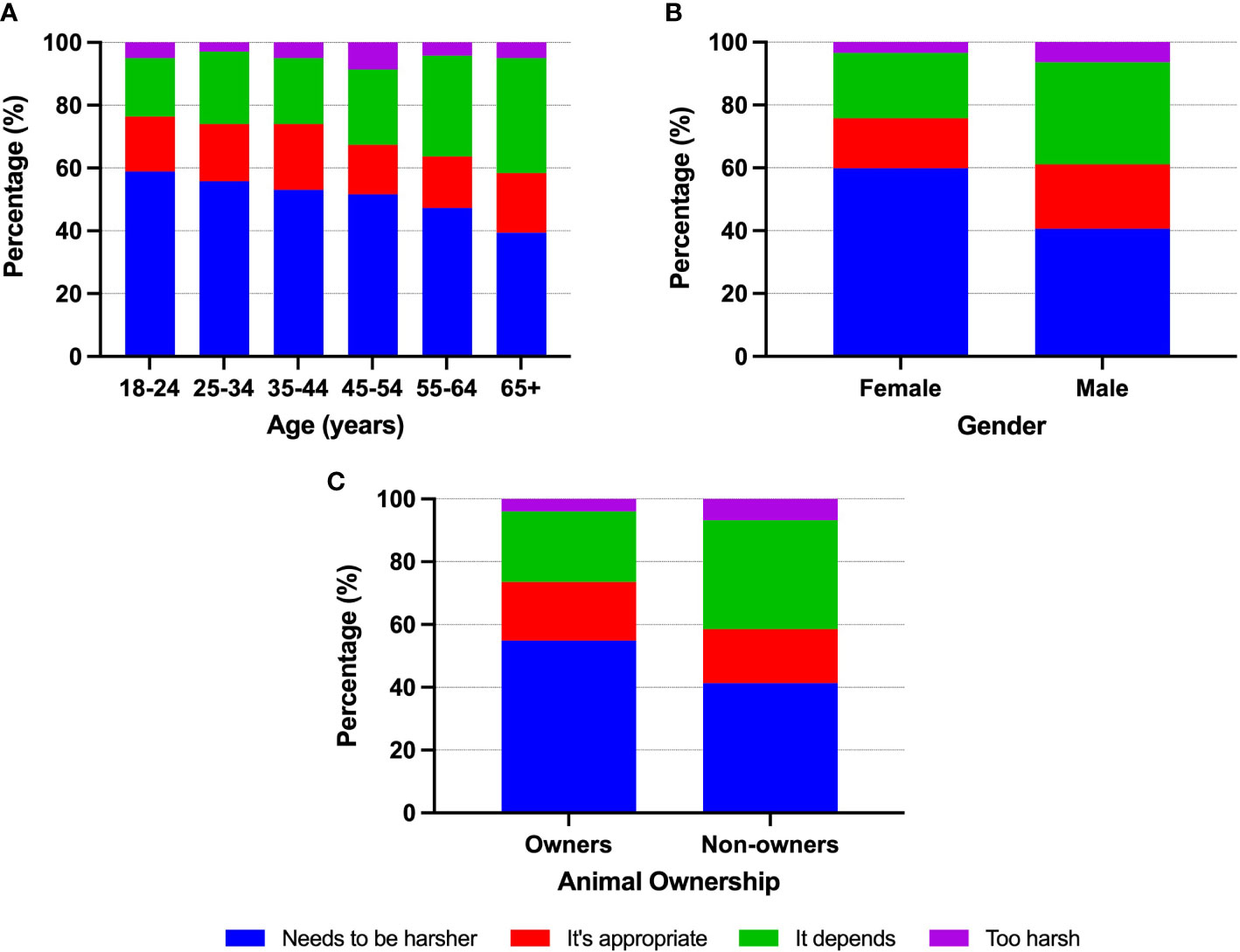

In total, 49.8% of participants believed the penalties handed down in court for animal cruelty offences needed to be harsher, whilst 27.2% believed that the sentence should depend on the individual circumstance of the case, 17.8% believed that the current sentences are appropriate, and 5.2% thought they were too harsh. Participants were informed that previous South Australian research has shown that on average 10% of the maximum penalties are used in court, which would equate to approximately a 4 month imprisonment sentence (Morton et al., 2018). Relationship between responses and demographic variables is shown in Table 3, where gender, age and animal ownership were found to be significant factors (p-value <0.000) and residential location had no significant relationship with response.

Table 3 Association between demographic variables and opinion on sentences for deliberate animal cruelty.

The significant associations between age (A), gender (B) and animal ownership (C) and responses toward sentencing outcomes are shown in Figure 8. A higher proportion of females believed that the penalties needed to be harsher (59.9%) in comparison to males (40.6%). There were no differences between the proportion of males and female who believed that the penalties were appropriate. However, a higher proportion of males believed that the penalties should depend on the individual circumstance (32.5%) in comparison to females (20.7%). Younger participants commonly believed penalties should be harsher in comparison to older participants. Whilst responses of ‘it depends’ were more common amongst older participants. There were minimal differences between the proportions of ‘it’s appropriate’ responses. The 45-54 year age group had a higher proportion (8.6%) of ‘too harsh’ responses. Participants who owned animals responded more commonly with ‘needs to be harsher’ (54.9%) in comparison to non-owners (41.3%), and non-owners had a high proportion of ‘it depends’ responses (34.7%) in comparison to animal owners (22.5%).

Figure 8 Response percentages showing the significant relationship between opinion on sentences for animal cruelty and the demographic variables of age (A), gender (B) and animal ownership (C); p-value < 0.05. “Previous research has shown that the average penalty for this type of offence [deliberate animal cruelty causing serious harm] is 4 months imprisonment; do you think this is appropriate and sufficient?”.

This study aimed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the undisclosed, yet heavily referred to “community expectations” around animal welfare law objectives in Australia. In contrast to previous research, which suggests that the community view harsher penalties as favorable, our results suggest that the community favors increasing the number of prosecutions, rather than the magnitude of sentences. When considered with our other findings that there is some degree of trust in the legal system to make decisions on penalties and that there is strong support for prohibiting offenders found guilty of AWA offences from owning animals, the implications are that the Australian public care more about the prevention of animal cruelty through a strong enforcement model, rather than an inflexible punitive approach after cruelty has occurred. Thus, public opinion could be shifting towards a more proactive approach to animal welfare enforcement rather than a reactive, punitive approach to animal cruelty. The remainder of this paper will discuss these findings in line with previous research and provide further commentary about what these expectations could mean for the Australian animal welfare legal system specifically, and common law countries more generally.

Much of our findings are in line with previous research identifying that the Australian public are supportive of harsher sentences for animal welfare offences. The previous survey of Taylor and Signal (2009) found that approximately 60% of respondents believed the current penalties for deliberate companion animal cruelty were not strong enough. However, there are some differences in design between the two studies, with Taylor and Signal (2009) not defining whether ‘penalties’ relate to the maximum penalties written in legislation or the penalties handed down for offences in court (as we have referred to as ‘sentences’), which in practice are vastly different. In the federated Australian system, each state and territory has set differing maximum penalties for both duty of care breaches and deliberate cruelty. However focusing solely on deliberate animal cruelty the maximum ranges from 2 years in prison to 5 years (see Morton et al. (2021) for a detailed account of all custodial and monetary maximums in each Australia jurisdiction). However, the sentenced penalty is often significantly lower. Our previous research analyzing case sentences in South Australia has shown that on average 10% of the maximum penalties are being used in court (Morton et al., 2018). Furthermore, Taylor and Signal (2009)’s study specifically focused on companion animal cruelty, whilst ours remains more general. In our study, fifty percent of respondents believed that the current sentences for deliberate animal cruelty were not harsh enough. However, the 50% remainder then either believed that the current sentences handed down for offences were appropriate, or that they should depend on the circumstances of the case. This finding may reflect an appreciation for the complexity of sentencing and the nuanced approach applied by the courts. Paired with the finding that a higher proportion of our sample believed that the legal system should decide the outcome of the case, rather than having a direct preference towards punishment in the form of custodial sentences or monetary fines, this is suggestive that the Australian public have a level of trust in the criminal justice system around sentencing in this area of law.

Given the complexity of case sentencing (Markham, 2009), this purported trust in the legal system is likely favorable for society; as expressed by a New South Wales Magistrate:

“If the courts were to adopt a populist approach and seek to satisfy the community outrage as often whipped up by various arms of the media at the expense of doing justice, then the community as a whole suffer” (Schreiner, 2005).

However, this does make the common referral to reform being based on community expectations perplexing as this would suggest that the arms of government may be out of step with each other. Alternatively, there could be political reasons at play. Political science literature suggests that policy makers who fail to declare themselves tough on crime are taking big electoral risks (Hough, 2003), thus by publicly announcing that ‘community expectations’ are driving the AWAs increased punitive power, it creates popularity for parliamentarians and increases their chances of re-election. This potentially makes the AWA reform efforts largely ‘symbolic gestures’, rather than practical tools to increase sentences in court (Morton et al., 2021), and tends to direct blame towards the court system rather than the parliamentary process. In addition, policy makers are more interested in generalized, aggregated trends in public preferences, rather than specific preferences relating to targeted policy areas (Stimson, 1999; Erikson et al., 2002; Stimson, 2004). In other words, policy makers are leading the public “in particulars by following [it] in general” (Stimson, 1999), likely meaning that specific ‘community expectations’ relating to animal welfare law are not driving the increases to AWA’s maximum penalties, instead a generalized public desire toward greater punitiveness in law is being considered (Pickett, 2019).

Public criticism of fines and imprisonment sentences for criminal offences likely stems from a lack of understanding of the criminal justice system (Pickett et al., 2015), and the alternative forms of penalties available. In addition, access to information on sentencing, usually delivered by various sectors of the media, further consolidates public opinion that sentencing is too lenient (Hough, 2003). Consequently, this makes fines and imprisonment the easiest forms of punishment to envision by the public (Bernuz Beneitez and María, 2022), and criticize when unhappy with a court’s determination. In reality, court determinations are driven by weighing of evidence, consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors, precedents, judicial discretion, as well as principles set through sentencing legislation. However, in the absence of such understanding, criminology literature has suggested that public opinion towards harsher penalties is unreliable (Cullen et al., 2000; Drakulich and Kirk, 2016) and stems from an overestimation of the lenience of the system (Frost, 2010), consequently creating the “myth of the punitive public” (Thielo et al., 2016). Further evidence being that when provided with accurate information about criminal punishment (through fact sheets, videos, or seminars) public support towards harsher penalties reduces (Hough and Park, 2002; Bohm and Vogel, 2004; Indermaur et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2012). Unsurprisingly, the information on animal welfare law enforcement portrayed through the media is substantially negative and tends to focus on the worst cases of cruelty (Arluke et al., 2002; Hampton et al., 2020; Morton et al., 2022), painting a picture that cruelty is worse than it seems to the public, augmenting their need for greater punitiveness.

Support of greater punitiveness for animal cruelty specifically and criminal acts more generally is not exclusive to Australia. For example support for prison sentences has also been observed in studies from the United States (Sims et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2016). However, a recent Spanish study has challenged this widespread viewpoint by identifying that support for alternative forms of penalties was high. Bernuz Beneitez and María (2022) identified public support towards rehabilitative programs based on anger management was equally balanced against support for imprisonment sentences. This support for less punitive, alternative sentencing outcomes is gratifying given that previous commentators have suggested that fines and imprisonment are not the most effective way to rehabilitate animal cruelty offenders (Livingston, 2001; Sharman, 2002; Morton et al., 2018). Scholarly support for alternative penalties is derived from the knowledge that fines or imprisonment sentences meet very few of the punishment theory aspects, being deterrence, retribution, rehabilitation, restitution, and incapacitation (Escamilla-Castillo, 2010; Zaibert, 2012; Bregant et al., 2016; Sylvia, 2016). Ghasemi (2015) has suggested that the fundamentals of criminal acts should be considered by legal systems to apply strategies to “solve the problem” for the offender rather than just penalizing them. This way, the court determination could be more effective in reducing recidivism, which our findings indicate is highly regarded by the public, more so than harsher sentences. Proposed alternative penalties focus on the rehabilitative aspect of punishment theory and often include court-mandated counselling and non-violent-conflict resolution training (Sharman, 2002). As noted by Holoyda (2018), the type of counselling best suited for the treatment of animal cruelty is unknown as there are no models which have undergone any sort of study or peer review. However, consideration for alternative penalties is important for starting discussions and building traction in this area of law, especially considering any public support for less punitive outcomes (i.e., rehabilitation) may be overlooked by policy makers when generalized public perceptions are trending toward greater punitiveness (Shapiro, 2011; Lax and Phillips, 2012). This means that although public opinion may be shifting towards a more proactive, less punitive approach to animal welfare, policy makers will likely maintain a reactive punitive approach. Fortunately, there are means available to achieve this proactive approach which do not rely on policymakers’ buy-in.

Firstly, to achieve a proactive approach to animal welfare law enforcement a strong enforcement model is needed. Currently, the bulk of the enforcement burden in Australian jurisdictions is given to non-governmental organizations (NGOs), with some sharing of responsibility with government departments (Morton et al., 2020). Although this model differs strikingly from that of the general criminal law where individual government-funded agencies (i.e., state or federal police forces) carry the burden, this enforcement model for animal welfare law has an extensive history in Australia (Caulfield, 2008), as in many other countries like Canada (Coulter and Campbell, 2020; Coulter, 2022), United Kingdom (Hughes and Lawson, 2011), New Zealand (Rodriguez Ferrere et al., 2019) and most European countries outside of Scandinavia (Coulter and Fitzgerald, 2019). Furthermore, it has been recommended as the most appropriate model by parliamentary inquiries in the Australian states of Western Australia and Victoria (Easton et al., 2015; Comrie, 2016) (with the other states yet to have an inquiry into this matter). Whilst, select NGOs receive annual financial support from the relevant state or territory government to cover the costs of enforcement (Morton et al., 2020), there is speculation within the literature about whether the funding supplied is sufficient to enforce the legislation to its full capacity (Ellison, 2009; Duffield, 2013). It is important to acknowledge however that resourcing constraints are purely speculated, with a lack of information publicly available either to support or refute this claim.

Our findings indicate that the community believe the current prosecution rates to be too low, suggesting the enforcement model is not strong enough to meet the communities’ expectations. One reason for low prosecution rates may be that there are insufficient resources to investigate and prosecute reported cases. Additionally, if there is a resource gap enforcement authorities will be persuaded to only take cases to court that ‘are a sure win’, for example where evidence is strong and substantial, as a way of saving resources by reducing the risk of adverse cost orders (Ellison, 2009; Duffield, 2013). This also precludes the bringing of test cases, exploring new areas of law, to court. As a result, statutory law reform remains the main way for animal law to progress and this process, requires a substantial level of support, is retrospective and often lengthy (Cook et al., 2009). As we have seen, these statutory reform efforts are the main vehicle to align what is happening in practice with community expectations. However, as Schreiner (2005) noted, the likelihood of creating any degree of alignment is improbable simply due to the retrospective nature of legislative reforms. Thus, the expansion of the common law through increased court caseload, could advance and expedite application of animal welfare law by creating incremental improvements to its interpretation in court. This may lead to faster alignment of practice with community expectations than waiting for the groundswell of support policy makers require for legislative reforms. If any criticism relating to resourcing holds merit, it could mean resources are a limiting factor for increasing the numbers of investigations resulting in prosecution. Therefore, funding allocations would require further consideration by state governments in order to accurately align legislation to the community expectations. This makes the question posed by South Australian parliamentarian, the Honourable Mark Parnell in 2007 still valid 15 years later.

“What is the point of increasing penalties if we do not increase the resources that are used to investigate cases of animal cruelty?” (South Australian Legislative Council, 2007).

Alternately, there may be adequate resourcing and alternate reasons why prosecution rates are perceived to be low. Firstly, there is a suggestion that public belief of what constitutes good welfare may be higher than the AWAs threshold for an offence (Victorian Legislative Assembly Committee, 2017). This could lead to higher reporting of alleged animal cruelty with the cases having no substance. Rectification of this issue is likely best achieved through public education campaigns that not only focus on the identity of the relevant enforcement authority in each jurisdiction, but also make clear the types of incidents that may constitute a legal act of cruelty. However, as noted by Glanville et al. (2021) due to the complexity and diversity of community attitudes towards animal cruelty, education programs that have the greatest chance of success are likely those that directly target the relevant audience. These may be aimed at particular demographic groups. To date education programs in this area have tended to be generalized education campaigns delivered through mainstream information sources. Given the findings of a number of previous studies (Paul, 2000; Taylor and Signal, 2006a; Taylor and Signal, 2006b; Phillips et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2012; Glanville et al., 2021), as well as the current study, which show that there are associations between community opinion and the demographic factors of gender and age, where females and younger adults tend to support harsher penalties and are most in favor of legislative change, these demographic groups may be a logical first focus when planning these education campaigns. Additionally, further improvements to address underreporting could include the mandated reporting by veterinary professionals of suspected cruelty whilst protecting them from liability if reporting in good faith. This has already been implemented in some Canadian provinces (Marion, 2015). This may be especially relevant to the Australian scenario given that there is suggestion that the Australian public already believe this to be the case (Acutt et al., 2015). On this note, Hanrahan and Chalmers (2020) have argued that animal welfare issues require a greater focus in the realm of social work services. They argue that the lack of service coordination and cross-sector reporting between social work agencies and animal welfare authorities fails to acknowledge the established link between interpersonal violence and animal cruelty (Walton-Moss et al., 2005; Volant et al., 2008; DeGue and DiLillo, 2009; Flynn, 2011; Febres et al., 2014; Levitt et al., 2016; Newberry, 2017; Macias-Mayo, 2018). Hence, as with mandated veterinary reporting there is the potential to mandate reporting for social workers, especially considering these professionals likely have greater insight into human-animal relations, and access into private homes, compared to the general public.

Secondly, there may be challenges in meeting the evidential burden to satisfy the court that the offence elements have been met. This may stem from less developed forensic technology for animals (Ledger and Mellor, 2018), the time taken to detect and initiate an investigation, or innate challenges with maintaining an evidence chain of custody where multiple animals may be involved (i.e., individual identification of animals to link with evidence of harm). Thirdly, there could be a deficit in the written law such that animal cruelty is occurring but has not advanced to the stage where a breach of an act provision has occurred. For example, the threshold of animal welfare offences often requires the animal to suffer before an offence is committed (Morton et al., 2021), which is in direct contradiction to the objective of the AWAs nationally since the legislation is not able to “promote animal welfare” (Australian Capital Territory Government, 2022; New South Wales Government, 2022; Northern Territory Government, 2022; Queensland Government, 2022; South Australian Government, 2022; Tasmanian Government, 2022; Victorian Government, 2022; Western Australian Government, 2022) if it requires evidence of harm. Previously we have suggested amending the wording for some offences to include “likely to cause harm” to provide options for intervention prior to the animal experiencing any degree of harm or suffering (Morton et al., 2021), which could bring the threshold of an offence closer to community expectations. In reality, all of these factors are likely to be contributors towards the attrition in numbers from cruelty report to prosecution, and thus the perception of low prosecution rates. This misalignment between community expectations and the current outcomes of the legal system has been referred to as an ‘enforcement gap’ in animal welfare law (Morton et al., 2020). This concept recognizes the many stakeholders involved in this process and how their interests need to be balanced against one another – the community being one key stakeholder. The way animal law enforcement is viewed by the community is affected by public understanding and attitudes (Ohl and van der Staay, 2012), meaning that further education on animal law enforcement and its limitations would likely aid in reducing the perception that greater punitive measures are needed (Hough and Park, 2002; Bohm and Vogel, 2004; Indermaur et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2012).

While our recruitment for this survey was representative, as it was also voluntary there is the potential for bias towards people who are more concerned about or engaged with animal-related issues. Being anonymous the risk of social desirability bias was reduced, as participants feel more comfortable responding truthfully instead of providing responses considered ‘favorable’ when they know their responses will not be shared with others (Lai et al., 2021). Finally, due to the lack of research in this area, there is little empirical data against which comparisons can be drawn. Whilst we have taken the utmost care to provide informed assumptions based on previous research, parliamentary statements and history, our discussions on prosecution rates and resourcing limitations are only speculative and require validation. In addition, our methodological approach focused solely on public opinion, rather than the public’s knowledge of animal welfare law enforcement. Whilst we provided the respondents with some basic information in order to gauge their opinions on adequacy of the law, the information provided was limited in scope and depth. This approach of assessing opinion rather than knowledge was taken since policymakers cite community opinions and perceptions in their discussion on legal reform in this area. However, we do acknowledge there is likely a connection between knowledge and opinion, as knowledge will likely guide and shape opinion (Erian and Phillips, 2017). Indeed, it is for this reason that we excluded legal and law enforcement professionals from recruitment. Further research is required to understand the depth of public knowledge on animal law enforcement, and the effect that increasing knowledge of the process has on opinions more generally.

The Australian public surveyed supported a move towards higher prosecution rates and use of prohibition orders, rather than punishment of offenders through harsher penalties. These findings could suggest that the public are shifting their stance on animal welfare law towards a more proactive, educative approach rather than a reactive, punitive focus. However, in order to increase investigation and/or prosecution rates, there is likely to be a need for extra resources. In addition, with a larger number of cases entering the court system there will be increased opportunities for common law to progress, and thus the availability of increased precedent around statutory interpretation on provisions will guide future decisions. Thus, although greater resources may be initially required to increase enforcement power, the improvements in common law may reduce the need for legislative reforms, which likely would reduce the resources required during parliamentary inquiries and debates. However, this approach requires further consideration with the use of current data on enforcement and prosecution statistics.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RM, AW, MH, and RA, conceptualization and methodology. RM and MH, formal analysis. RM, writing – original draft preparation. RM and AW, writing – review and editing. AW, MH, and RA, supervision. AW, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Contracting of Qualtrics for data collection was funded by a grant received from The Australian Federation of University Women – South Australia (AFUW-SA) Inc. Trust Fund.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2022.991042/full#supplementary-material

Acutt D., Signal T., Taylor N. (2015). Mandated reporting of suspected animal harm by Australian veterinarians: Community attitudes. Anthrozoös 28 (3), 437–447. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.1052276

Allen M., Hunstone M., Waerstad J., Foy E., Hobbins T., Wikner B., et al. (2002). Human-to-Animal similarity and participant mood influence punishment recommendations for animal abusers. Soc. Anim. 10 (3), 267–284. doi: 10.1163/156853002320770074

Arluke A., Frost R., Patronek G., Luke C., Messner E., Nathanson J., et al. (2002). Press reports of animal hoarding. Soc. Anim. 10 (2), 113–135. doi: 10.1163/156853002320292282

Australian Capital Territory Government (2019) Animal welfare legislation amendment act 2019. Available at: https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/View/a/2019-35/20191017-72390/PDF/2019-35.PDF (Accessed 1 February 2022).

Australian Capital Territory Government (2022) Animal welfare act 1992. section 4A. Available at: https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/View/a/1992-45/current/PDF/1992-45.PDF (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Bailey S. K. T., Sims V. K., Chin M. G. (2016). Predictors of views about punishing animal abuse. Anthrozoös 29 (1), 21–33. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.1064217

Bennett R. M., Anderson J., Blaney R. J. P. (2002). Moral intensity and willingness to pay concerning farm animal welfare issues and the implications for agricultural policy. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 15 (2), 187–202. doi: 10.1023/A:1015036617385

Bernuz Beneitez M. J., María G. A. (2022). Public opinion about punishment for animal abuse in Spain: Animal attributes as predictors of attitudes toward penalties. Anthrozoös 35 (4), 559–576. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2021.2012341

Bohm R. M., Vogel B. L. (2004). More than ten years after: The long-term stability of informed death penalty opinions. J. Crim. Justice 32 (4), 307–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.04.003

Bregant J., Shaw A., Kinzler K. D. (2016). Intuitive jurisprudence: Early reasoning about the functions of punishment. J. Empi. Legal Stud. 13 (4), 693–717. doi: 10.1111/jels.12130

Caulfield M. (2008). Animal cruelty law and intensive animal farming in south Australia - light at the end of the tunnel? Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 1, 36–44.

Comrie N. (2016) Independent review of the RSPCA Victoria inspectorate - transformation of the RSPCA Victoria inspectorate (RSPCA Victoria). Available at: https://www.rspcavic.org/documents/RSPCA_IndependantReview_final.pdf (Accessed 8 February 2022).

Cook C., Creyke R., Geddes R., Hamer D. (2009). “Case law and precedent,” in Laying down the law, 7th ed (Chatswood, NSW: LexisNexis Butterworths), 57–93.

Coulter K. (2022). The organization of animal protection investigations and the animal harm spectrum: Canadian data, international lessons. Soc. Sci. 11 (1), 22. doi: 10.3390/socsci11010022

Coulter K., Campbell B. (2020). Public investment in animal protection work: Data from Manitoba, Canada. Animals 10 (3), 516. doi: 10.3390/ani10030516

Coulter K., Fitzgerald A. (2019). The compounding feminization of animal cruelty investigation work and its multispecies implications. Gender work Organ. 26 (3), 288–302. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12230

Cullen F. T., Fisher B. S., Applegate B. K. (2000). “Public opinion about punishment and corrections,” in Crime and justice: A review of research. Ed. Tonry M. (Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press), 1–79.

DeGue S., DiLillo D. (2009). Is animal cruelty a “Red flag” for family violence? J. Interperson. Violence 24 (6), 1036–1056. doi: 10.1177/0886260508319362

Drakulich K. M., Kirk E. M. (2016). Public opinion and criminal justice reform: Framing matters. Criminol. Public Policy 15 (1), 171–177. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12186

Duffield D. (2013). The enforcement of animal welfare offences and the viability of an infringement regime as a strategy for reform. New Z. Univer. Law Rev. 25 (5), 897–937. doi: 10.3316/agispt.20140915

Easton B., Warbey L., Mezzatesta B., Mercy A. (2015) Animal welfare review. Available at: https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/sites/gateway/files/Animal%20Welfare%20Review%20-%20October%20%202015.pdf (Accessed 8 February 2022).

Ellison P. C. (2009). Time to give anticruelty laws some teeth - bridging the enforcement gap. J. Anim. Law Ethics 3, 1–6.

Erian I., Phillips C. J. C. (2017). Public understanding and attitudes towards meat chicken production and relations to consumption. Animals 7 (3), 20. doi: 10.3390/ani7030020

Erikson R. S., Mackuen M. B., Stimson J. A. (2002). The macro polity (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Escamilla-Castillo M. (2010). The purposes of legal punishment. Ratio Juris 23 (4), 460–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9337.2010.00465.x

Febres J., Brasfield H., Shorey R. C., Elmquist J., Ninnemann A., Schonbrun Y. C., et al. (2014). Adulthood animal abuse among men arrested for domestic violence. Violence Against Women 20 (9), 1059–1077. doi: 10.1177/1077801214549641

Flynn C. P. (2011). Examining the links between animal abuse and human violence. Crime Law Soc. Change 55 (5), 453–468. doi: 10.1007/s10611-011-9297-2

Frost N. A. (2010). Beyond public opinion polls: Punitive public sentiment and criminal justice policy. Sociol. Compass 4 (3), 156–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00269.x

Geysen T.-L., Weick J., White S. (2010). Companion animal cruelty and neglect in Queensland: Penalties, sentencing and “Community expectations”. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 4, 46–63.

Ghasemi M. (2015). Visceral factors, criminal behavior and deterrence: Empirical evidence and policy implications. Eur. J. Law Econom. 39 (1), 145–166. doi: 10.1007/s10657-012-9357-9

Glanville C., Ford J., Cook R., Coleman G. J. (2021). Community attitudes reflect reporting rates and prevalence of animal mistreatment. Front. Vet. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.666727

Hampton J. O., Jones B., McGreevy P. D. (2020). Social license and animal welfare: Developments from the past decade in Australia. Animals 10 (12), 1–11. doi: 10.3390/ani10122237

Hanrahan C., Chalmers D. (2020). “Animal-informed social work: A more than critical practice,” in Critical clinical social work: Counterstorying for social justice. Eds. Brown C., MacDonald J. (Toronto, Ontario: Canadian Scholars Press), 195–224.

Holoyda B. J. (2018). Animal maltreatment law: Evolving efforts to protect animals and their forensic mental health implications. Behav. Sci. Law 36 (6), 675–686. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2367

Hough M. (2003). Modernization and public opinion: Some criminal justice paradoxes. Contemp. Politics 9 (2), 143–155. doi: 10.1080/1356977032000106992

Hough M., Park A. (2002). “How malleable are attitudes to crime and punishment? findings from a British deliberative poll,” in Changing attitudes to punishment: Public opinion, crime and justice. Eds. Roberts J. V., Hough M. (Willan: Portland, OR), 163–183.

Hughes G., Lawson C. (2011). RSPCA And the criminology of social control. Crime Law Soc. Change 55 (5), 375–389. doi: 10.1007/s10611-011-9292-7

Indermaur D., Roberts L., Spiranovic C., Mackenzie G., Gelb K. (2012). A matter of judgement: The effect of information and deliberation on public attitudes to punishment. Punishment Soc. 14 (2), 147–165. doi: 10.1177/1462474511434430

Lai Y., Boaitey A., Minegishi K. (2021). Behind the veil: Social desirability bias and animal welfare ballot initiatives. Food Policy 106, 102184. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102184

Lax J. R., Phillips J. H. (2012). The democratic deficit in the states. Am. J. Political Sci. 56 (1), 148–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00537.x

Ledger R. A., Mellor D. J. (2018). Forensic use of the five domains model for assessing suffering in cases of animal cruelty. Animals 8 (7), 101. doi: 10.3390/ani8070101

Levitt L., Hoffer T. A., Loper A. B. (2016). Criminal histories of a subsample of animal cruelty offenders. Aggress. Violent Behav. 30, 48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.05.002

Livingston M. (2001). Desecrating the ark: Animal abuse and the law's role in prevention. Iowa Law Rev. 87, 1–1649.

MacArthur Clark J., Clifford P., Jarrett W., Pekow C. (2019). Communicating about animal research with the public. ILAR J. 60 (1), 34–42. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilz007

Macias-Mayo A. R. (2018). The link between animal abuse and child abuse. Am. J. Family Law 32 (3), 130.

Markham A. (2009). “Animal cruelty sentencing in Australia and new Zealand,” in Animal law in Australasia: A new dialogue. Eds. Sankoff P. J., White S. W. (Sydney: Federation Press).

Mayer H. (2002). “Animal welfare verification in Canada: A discussion paper,” in Discussion papers 18123 (St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis).

Mellor D. J. (2019). Welfare-aligned sentience: Enhanced capacities to experience, interact, anticipate, choose and survive. Animals 9 (7), 440. doi: 10.3390/ani9070440

Morgan N. (2002) Sentencing trends for violent offenders in Australia (University of Western Australia: Crime Research Centre). Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/sentencing-trends-violent-offenders-australia (Accessed 13 July 2022).

Morton R., Hebart M. L., Ankeny R. A., Whittaker A. L. (2021). Assessing the uniformity in Australian animal protection law: A statutory comparison. Animals 11 (1), 35. doi: 10.3390/ani11010035

Morton R., Hebart M. L., Whittaker A. L. (2022). Portraying animal cruelty: A thematic analysis of Australian news media reports on penalties for animal cruelty. Animals 12 (21), 2918. doi: 10.3390/ani12212918

Morton R., Hebart M. L., Whittaker A. L. (2018). Increasing maximum penalties for animal welfare offences in south Australia–has it caused penal change? Animals 8 (12), 236. doi: 10.3390/ani8120236

Morton R., Hebart M., Whittaker A. (2020). Explaining the gap between the ambitious goals and practical reality of animal welfare law enforcement: A review of the enforcement gap in Australia. Animals 10 (3), 482. doi: 10.3390/ani10030482

National Health and Medical Research Council (2018) National statement on ethical conduct in human research (Australian Government). Available at: https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018 (Accessed 9 October 2018).

Newberry M. (2017). Pets in danger: Exploring the link between domestic violence and animal abuse. Aggress. Violent Behav. 34, 273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.11.007

New South Wales Government (2022) Prevention of cruelty to animals act 1979. section 3. Available at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1979-200 (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Northern Territory Government (2020) Animal protection act 2018. Available at: https://dpir.nt.gov.au/primary-industry/animal-welfare-branch/animal-protection-bill-2018 (Accessed 1 February 2022).

Northern Territory Government (2022) Animal welfare act 1999. section 3. Available at: https://legislation.nt.gov.au/Legislation/ANIMAL-WELFARE-ACT-1999 (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Nurse A. (2016). Beyond the property debate: Animal welfare as a public good. Contemp. Justice Rev. 19 (2), 174–187. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2016.1169699

Ohl F., van der Staay F. J. (2012). Animal welfare: At the interface between science and society. Vet. J. 192 (1), 13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.05.019

Paul E. S. (2000). Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös 13 (4), 194–202. doi: 10.2752/089279300786999699

Phillips C., Izmirli S., Aldavood J., Alonso M., Choe B., Hanlon A., et al. (2011). An international comparison of female and Male students' attitudes to the use of animals. Animals 1 (1), 7–26. doi: 10.3390/ani1010007

Phillips C. J. C., Izmirli S., Aldavood S. J., Alonso M., Choe B. I., Hanlon A., et al. (2012). Students' attitudes to animal welfare and rights in Europe and Asia. Anim. Welfare 21 (1), 87–100. doi: 10.7120/096272812799129466

Pickett J. T. (2019). Public opinion and criminal justice policy: Theory and research. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 2 (1), 405–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-011518-024826

Pickett J. T., Mancini C., Mears D. P., Gertz M. (2015). Public (Mis)understanding of crime policy: The effects of criminal justice experience and media reliance. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 26 (5), 500–522. doi: 10.1177/0887403414526228

Queensland Government (2001a) Animal care and protection act 2001. legislative history. Available at: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2001-064/lh (Accessed 1 February 2022).

Queensland Government (2001b) Animal care and protection bill 2001 explanatory notes. Available at: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/bill.first.exp/bill-2001-741 (Accessed 17 January 2022).

Queensland Government (2022) Animal care and protection act 2001. section 3. Available at: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2016-07-01/act-2001-064 (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Roberts J., Hough M., Jackson J., Gerber M. M. (2012). Public opinion towards the lay magistracy and the sentencing council guidelines: The effects of information on attitudes. Br. J. Criminol. 52 (6), 1072–1091. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azs024

Rodriguez Ferrere M. B., King M., Mros Larsen L. (2019) Animal welfare in new Zealand: Oversight, compliance and enforcement (report). Available at: https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10523/9276/Animal%20Welfare%20in%20New%20Zealand%20%20Oversight%2c%20Compliance%20and%20Enforcement%20%28Final%29.pdfsequence=8&isAllowed=y (Accessed 11 October 2022).

RSPCA (2021) Annual statistics 2019-2020. Available at: https://www.rspca.org.au/sites/default/files/RSPCA%20Australia%20Annual%20Statistics%202019-2020.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2021).

Sankoff P. (2005). Five years of the new animal welfare regime: Lessons learned from new zealand's decision to modernize its animal welfare legislation. Anim. Law 11, 7–38.

Schreiner S. (2005). “Sentencing animal cruelty,” in Cruelty to animals: A human problem (Canberra, Australia: Proceedings of the 2005 RSPCA Australia Scientific Seminar), 41–45.

Shapiro R. Y. (2011). Public opinion and American democracy. Public Opin. Q. 75 (5), 982–1017. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfr053

Sharman K. (2002). Sentencing under our anti-cruelty statutes: Why our leniency will come back to bite us. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 13 (3), 333–338. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2002.12036239

Sims V. K., Chin M. G., Yordon R. E. (2007). Don't be cruel: Assessing beliefs about punishments for crimes against animals. Anthrozoös 20 (3), 251–259. doi: 10.2752/089279307X224791

South Australian Legislative Council (2007) Bills: Prevention of cruelty to animals (Animal welfare) amendment bill - 13/11/2007. Available at: http://hansardpublic.parliament.sa.gov.au/Pages/HansardResult.aspx#/docid/HANSARD-10-282 (Accessed 17 January 2022).

South Australian Government (2008) Animal welfare act 1985. legislative history. Available at: https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/A/ANIMAL%20WELFARE%20ACT%201985/CURRENT/1985.106.AUTH.PDF (Accessed 1 February 2022).

South Australian Government (2022) Animal welfare act 1985. long title. Available at: https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/:legislation/lz/c/a/animal%20welfare%20act%201985/current/1985.106.auth.pdf (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Stimson J. A. (1999). Public opinion in America: Moods, cycles, and swings (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

Stimson J. A. (2004). Tides of consent: How public opinion shapes American politics (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Sylvia R. (2016). Corporate criminals and punishment theory. Can. J. Law Jurisprudence 29, 97–245. doi: 10.1017/cjlj.2016.4

Tasmanian Government (2022) Animal welfare act 1993. long title. Available at: https://www.legislation.tas.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/act-1993-063 (Accessed 1 March 2022]).

Taylor N., Signal T. D. (2006a). Attitudes to animals: Demographics within a community sample. Soc. Anim. 14 (2), 147–157. doi: 10.1163/156853006776778743

Taylor N., Signal T. D. (2006b). Community demographics and the propensity to report animal cruelty. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 9 (3), 201–210. doi: 10.1207/s15327604jaws0903_2

Taylor N., Signal T. D. (2009). Lock ‘em up and throw away the key? community opinions regarding current animal abuse penalties. Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 3, 33–52.

Thielo A. J., Cullen F. T., Cohen D. M., Chouhy C. (2016). Rehabilitation in a red state: Public support for correctional reform in Texas. Criminol. Public Policy 15 (1), 137–170. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12182

Tiplady C. M., Walsh D.-A. B., Phillips C. J. C. (2013). Public response to media coverage of animal cruelty. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 26 (4), 869–885. doi: 10.1007/s10806-012-9412-0

Vecchio Y., Pauselli G., Adinolfi F. (2020). Exploring attitudes toward animal welfare through the lens of subjectivity–an application of q-methodology. Animals 10 (8), 1–14. doi: 10.3390/ani10081364

Veissier I., Butterworth A., Bock B., Roe E. (2008). European Approaches to ensure good animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 113 (4), 279–297. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2008.01.008

Victorian Government (2012) Prevention of cruelty to animals act 1986. table of amendments. Available at: https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/in-force/acts/prevention-cruelty-animals-act-1986/096 (Accessed 1 February 2022).

Victorian Government (2020a) A new animal welfare act for Victoria. Available at: https://engage.vic.gov.au/new-animal-welfare-act-victoria (Accessed 3 July 2022).

Victorian Government (2020b) A new animal welfare act for victoria. directions paper. Available at: https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/hdp.au.prod.app.vic-engage.files/4616/0275/7674/AW_Directions_Paper.pdf (Accessed 17 August 2022).

Victorian Government (2021) A new animal welfare act for victoria. engagement summary report. Available at: https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/hdp.au.prod.app.vic-engage.files/1416/1961/8270/Engagement_Summary_Report.pdf (Accessed 24 January 2022).

Victorian Government (2022) Prevention of cruelty to animals act 1986. section 1. Available at: https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/in-force/acts/prevention-cruelty-animals-act-1986/096 (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Victorian Legislative Assembly Committee (2017) Transcript - inquiry into the RSPCA Victoria. Available at: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/committees/SCEI/RSPCA/Transcripts/FINAL-RSPCA.pdf (Accessed 9 February 2022).

Volant A. M., Johnson J. A., Gullone E., Coleman G. J. (2008). The relationship between domestic violence and animal abuse: An Australian study. J. Interperson. Violence 23 (9), 1277–1295. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314309

Walton-Moss B., Manganello J., Frye V., Campbell J. (2005). Risk factors for intimate partner violence and associated injury among urban women. Publ. Health Promotion Dis. Prev. 30 (5), 377–389. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-5518-x

Western Australian Government (2022) Animal welfare act 2002. section 3. Available at: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/statutes.nsf/main_mrtitle_50_homepage.html (Accessed 1 March 2022).

Keywords: animal welfare, animal cruelty, law enforcement, animal law, public opinion, Australia, penalties

Citation: Morton R, Hebart ML, Ankeny RA and Whittaker AL (2022) An investigation into ‘community expectations’ surrounding animal welfare law enforcement in Australia. Front. Anim. Sci. 3:991042. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2022.991042

Received: 11 July 2022; Accepted: 24 October 2022;

Published: 11 November 2022.

Edited by:

Linda Jane Keeling, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenReviewed by:

Randall Lockwood, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), United StatesCopyright © 2022 Morton, Hebart, Ankeny and Whittaker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rochelle Morton, cm9jaGVsbGUubW9ydG9uQGFkZWxhaWRlLmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.