94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Anim. Sci., 09 May 2022

Sec. Animal Physiology and Management

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2022.890914

This article is part of the Research TopicMinimally Invasive Monitoring of Stress in Farm Animals, Volume IView all 8 articles

Stress in Merino sheep can cause a reduction in the quantity and quality of fine wool production. Furthermore, it has been found that environmental stress during pregnancy can negatively affect the wool follicles of the developing fetus. This study was part of a larger field investigation on the effects maternal shearing frequency on sheep reproductive and productivity outcomes. For this study, we investigated the intra- and inter- sample variation in wool cortisol levels of weaner lambs. We conducted two experiments, the first was to determine the intra- and inter- sample variation in wool samples taken from the topknot of weaned lambs, and the other aim was to determine any difference between maternal shearing treatment (single or twice shearing) on absolute wool cortisol levels of weaned lambs. In the first experiment, topknot wool was collected from 10 lambs, and each sample was further divided into four subsamples, leading to a total of 40 wool subsamples. For the second experiment, we collected the topknot from the 23 lambs produced by the shearing frequency treatment ewes (once or twice shorn). The samples were then extracted and analyzed using a commercially available cortisol enzyme-immunoassay in order to determine the concentration of cortisol in each of the samples. Statistical analysis for the first experiment showed that there was no significant difference between the subsamples of each topknot wool sample taken from each lamb (p = 0.39), but there was a statistical difference between samples (p < 0.001), which was to be expected. In the second experiment, there was a significant difference between the lambs born to the one shearing and two shearing treatments (p = 0.033), with the lambs of the twice sheared ewes having higher average wool cortisol levels [2.304 ± 0.497 ng/g (SE); n = 14] than the ones born to once shorn ewes [1.188 ± 0.114 ng/g (SE), n = 8]. This study confirms that the topknot wool sampling can be a reliable method adapted by researchers for wool hormonal studies in lambs. Second, ewes shorn mid-pregnancy gave birth to lambs with higher cortisol concentrations than ewes that remained unshorn during pregnancy. This result warrants further investigation in a controlled study to determine if maternal access to nutrition (feed and water) may impact on the HPA-axis of lambs.

In order to improve the wool quality and quantity produced by Merino sheep selective breeding has been used extensively by commercial producers (Ansari-Renani and Hynd, 2001; Thompson et al., 2007; McDowall et al., 2011). Environmental conditions, nutrition, disease, and management of the animals, as well as genetics all contribute to achieve overall wool quality output. However, due to genetic variation, some individuals may cope better with their environment than others in the same herd and be more productive as a result (Oddy, 1999; Macé et al., 2019). One of the factors that is known to affect the wool quality and quantity output is stress, which was found to negatively affect the growth rate of wool was decreased and to cause a higher incidence of fiber shedding and breakage (Scobie and Hynd, 1995; Ansari-Renani and Hynd, 2001; Thompson et al., 2007; Gonzalez et al., 2020). Stress during pregnancy leads to an increased cortisol concentration in ewes, which is known to cause a reduction in wool follicle density emergence in the developing fetus (Thompson et al., 2007; McDowall et al., 2011). An experiment by Kelly et al. (1996) showed that lambs that were born to ewes that were under nutritional restrictions during mid to late pregnancy produced less wool. Specifically, the lambs born to ewes on a caloric deficit during pregnancy had a wool production of 140 g less per animal on each shearing compared to lambs born to mothers that were kept on maintenance weight throughout the pregnancy (Kelly et al., 1996). As such, farmers would benefit financially from providing adequate nutrition for ewes during pregnancy (Kelly et al., 1996; Sawyer et al., 2021).

Traditionally, blood plasma sampling, saliva, urine, and feces have been used to determine the circulating glucocorticoids in animals, however recently hair has been used as a better alternative (Hargreaves and Hutson, 1990; Morrow et al., 2002; Davenport et al., 2006; Nejad et al., 2014, 2020; Hernández-Cruz et al., 2016; Sawyer et al., 2021; Weaver et al., 2021). It has been found that steroids circulating in the blood stream are gradually integrated to the hair shaft while it grows, and as such analyzing the hair or wool of the animal can give a long-term record of the changes in steroids, such as cortisol, in the animal (Davenport et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2014; Nejad et al., 2014, 2020; Sawyer et al., 2019, 2021; Weaver et al., 2021). Since steroids are incorporated to the hair/wool shaft at a slow rate, it is not affected by the daily fluctuations of the hormones and it can be used to measure chronic stress, since it can store the steroid changes of weeks or even months, depending on the species (Davenport et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2014; Nejad et al., 2014, 2020; Sawyer et al., 2019, 2021; Weaver et al., 2021). A study by Nejad et al. (2014) that used both blood and wool samples in order to measure cortisol in sheep under heat stress and water restrictions concluded that cortisol in wool was a more accurate method of measuring stress in the animals used (Nejad et al., 2014; Sawyer et al., 2021). To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure wool cortisol in Merino lambs.

In this study, we used the topknot wool samples from lambs in order to measure their cortisol concentration, as it has been found that steroids get slowly incorporated into the hair shaft and can provide reliable long-term data (Davenport et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2014; Nejad et al., 2014, 2020; Sawyer et al., 2019, 2021; Weaver et al., 2021). The primary aim of this research is to determine whether there was a difference in the cortisol concentration in the wool of those lambs born to mothers in different shearing treatments.

The first research experiment aims to validate the topknot wool collection method by assessing the intra-sample variation within lamb samples, and the second research experiment assesses the differences in cortisol concentration between the lambs born from the different shearing treatments. Firstly, it is hypothesized that there will not be any significant intra-sample variation of cortisol concentration between the sub-samples of the same wool sample. Secondly, it is hypothesized that cortisol concentration will not be different between lambs born from mothers that were shorn while pregnant compared to lambs born from mothers that were not shorn during the pregnancy.

This research was originally approved by Western Sydney University ACEC Protocol (A12610) which was later ratified by The University of Queensland ACEC Approval Protocol (SAFS/544/19).

The lambs used in this study were born from a commercial flock located in a Merino sheep farm in Cattai NSW 2756 (-33.560171405989955, 150.90633541637254). For this study, the topknot wool was collected from the lambs, as it was been found to be an effective and convenient method of wool collection of a small research sample (Sawyer et al., 2021).

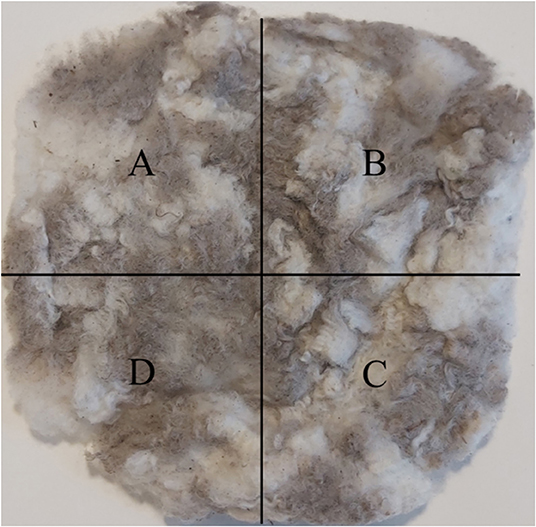

For intra-sample variation analysis, ten wool samples were selected at random. Each wool sample was divided into 4 equal sized blocks using a mm ruler, as shown in Figure 1, and sub-samples were taken out of each marked area, which resulted in 40 sub-samples. As the wool samples were chosen randomly, some belonged to either of the two sheering trials and some were from the rest of the flock.

Figure 1. Frozen wool sample collected for intra-sample variation analysis were divided into four areas, (A–D) from which sub-samples were taken.

Forty-eight mixed-age Merino ewes were used for the shearing experiment, with 24 ewes assigned into the Once shorn treatment and the other 24 in the Twice shorn treatment. Of those that successfully gave birth, only some could be successfully matched with their biological offspring. The 23 of those 25 lambs, presented in Table 1, were used for the second experiment of this study, as samples 22 and 29 could not be found at the time of processing. Ewe genetics, physiological and behavioral data and lamb wool quality data has been submitted in another published manuscript (Narayan et al., 2022).

Table 1. A summary of information of the ewes, the shearing treatment they were assigned to, the pregnancy diagnosis status, and the ID of the lambs used in this study.

The topknot wool samples from the crown (head) of the lambs was collected for this study. All collected samples were wrapped in aluminum foil and placed into Ziplock bags labeled with the sheep's identification number, site name, wool extraction type, and collection date. The samples were then frozen and stored at −20°C until processing.

All of the wool samples were processed and analyzed by the Stress Lab, Gatton Campus, The University of Queensland. From every sample 0.05 ± 0.02 g (Mean, SEM) of wool was collected, washed with 3 mL of 100% isopropanol and then left to dry overnight in a desiccator. Each washed sample was then cut into very small pieces and put in a labeled Eppendorf tube with 1 mL of 100% methanol and stored in a refrigerator overnight. Using a micropipette, 500 μL was extracted from the tubes and put into new labeled Eppendorf tubes and then left in a fume hood to dry overnight. The samples were then reconstituted by adding 25 μL of 100% methanol and 475 μL of ELISA assay buffer. The assay buffer used in the reconstitution was prepared by diluting 1:5 the assay buffer concentrate provided in the ELISA kit with distilled water. The reconstituted samples were vortexed and then the assay protocol of a DetectX® Cortisol Immunoassay Kit was followed, in order to determine the cortisol concentration of each sample.

First, seven standards were prepared using a cortisol standard at 32,000 pg/mL. Then 50 μL of each standard and sample was placed into a well of a clear 96-well plate, each of which was already coated with goat anti-mouse IgG as part of the kit. The standards and samples were run in duplicates in order to minimize error. For the non-specific binding (NSB) wells 75 μL of assay buffer was used and 50 μL of assay buffer for the maximum binding wells (0). With the help of a repeater pipet, 25 μL of DetectX® Cortisol Conjugate was placed in every well and 25 μL of DetectX® Cortisol Antibody was place in all wells except the three NSB wells.

The plate was then covered with a plate sealer and left shaking at 900 rpm in an automated plate shaker (BioTek, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, each well was washed 4 times with 300 μL of washed buffer by an automated plate washer (BioTek, USA). The wash buffer was prepared in advance by diluting the Wash Buffer Concentrate with distilled water in a 1:20 ratio. After the wash, the plate was tapped on a towel in order to dry, and then 100 μL of TMB Substrate was added to each well. The plate was re-sealed and left to incubate at room temperature for 30 min, after which 50 μL of Stop Solution was added to each well. The plate was then read at 450 nm in a microplate reader (BioTek, USA), and the cortisol concentrations were calculated and displayed in ng/g.

Data were analyzed using Minitab Statistical Software v.20.3.0.0. In order to test for difference in the cortisol concentration between the samples and the sub-samples in Experiment 1, a General Linear Model with fixed and random factors was used. In Experiment 2, sample 56 had a value of 6631.868 pg/well, however, the upper and lower limits of the assay were 4142.133 pg/well and 57.526 pg/well respectively, so the sample was removed from the dataset and not used in further analysis. In the remaining samples, visual inspection suggested deviation from normality for the Twice shorn group. Anderson-Darling test confirmed that although the Once shorn group conformed to a normal distribution (A2 = 0.195, p = 0.835), the Twice Shorn group was not normally distributed (A2 = 1.606, p < 0.005). The variances were considered to be approximately equal by a Levene test (W = 1.82, p = 0.192). A log10 transformation was applied, and there was no deviation from normality for either the Once shorn group (A2 = 0.177, p = 0.885) or the Twice shorn group (A2 = 0.541, p = 0.135). The variances were considered to be equal by a Levene test (W = 2.05, p = 0.168), so a t test assuming equal variances was appropriate to test for differences in the cortisol concentration (ng/g) between the two groups.

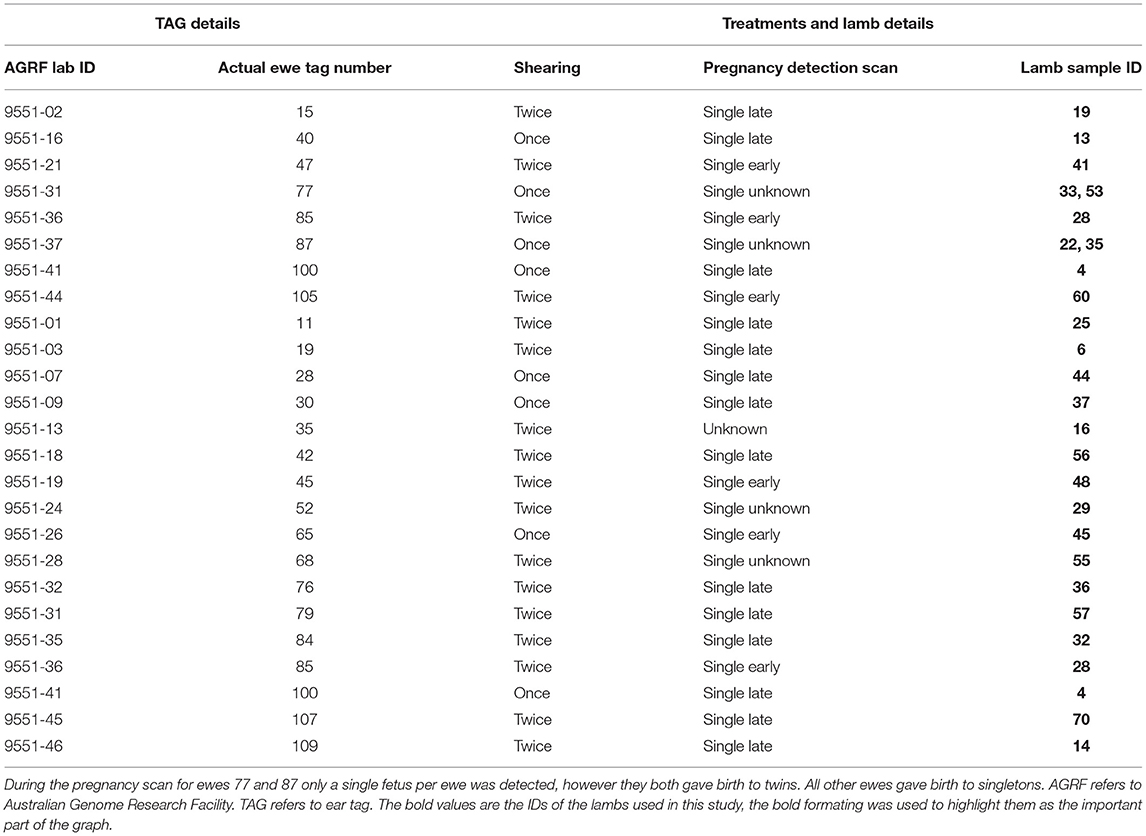

Due to time and space availability the samples were spread over three assays conducted between May and July, 2021, and as such the experiments were not conducted in parallel. The standard curves from all the assays are presented in Figure 2, and the coefficients of variation was 4.491% for Assay 1, 5.196% for Assay 2, 6.667% for Assay 2, and the average was 5.451%.

Figure 2. The cortisol standard curves from the assays conducted on (A) the 27th of May 2021, (B) 24th of June 2021, and (C) 27th of July 2021.

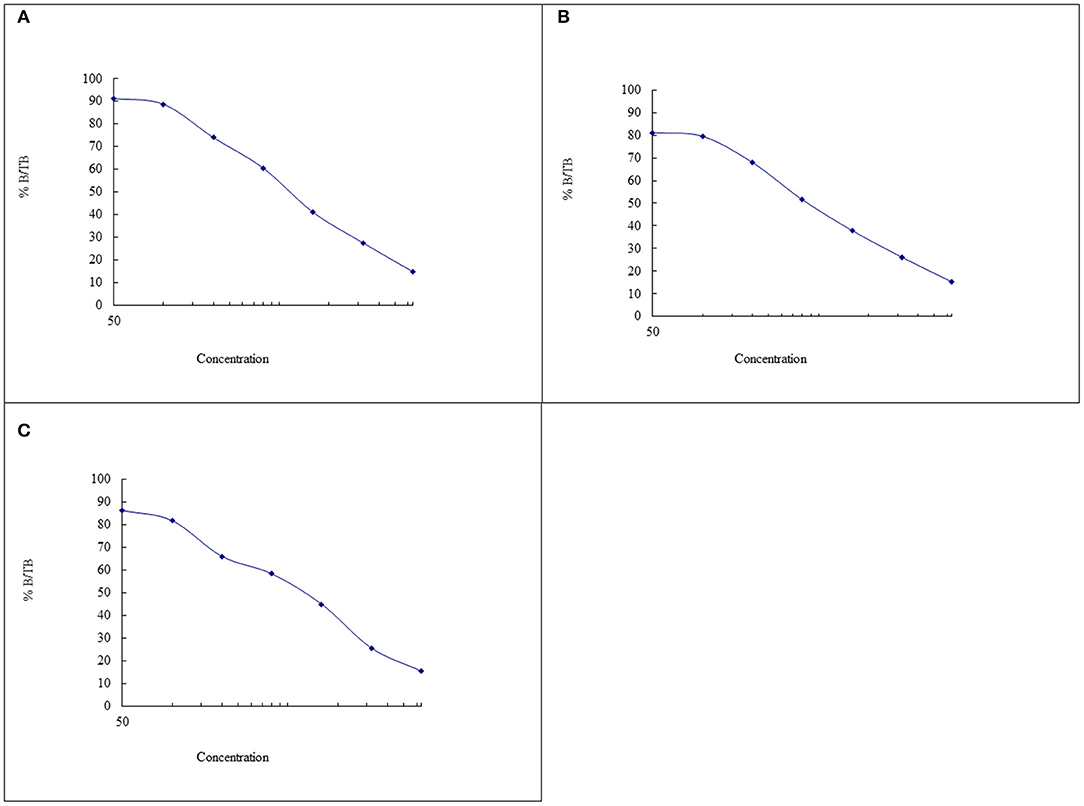

There was no significant difference in the mean cortisol concentration (ng/g) between the 4 sub-samples of every sample [ANOVA, F(3,27) = 1.04, p = 0.390], but there was a significant difference between the 10 wool samples [ANOVA, F(9,27) = 11.03, p < 0.001], as shown on Figure 3. The wool cortisol concentration ranged between 0.562 and 4.093 ng/g, and the overall average cortisol concentration was 2.058 ng/g.

Figure 3. Visual representation of the intra-variance cortisol concentration between the subsamples for every sample. Each number on the x-axis represents a wool sample and the sub-samples from that sample are on the same y-axis line based on the different cortisol concentration detected on each sub-sample. There is no significant difference between subsamples but there is between samples from different individuals.

Statistical analysis was conducted on the cortisol concentrations of the remaining 19 samples, presented in Table 2.

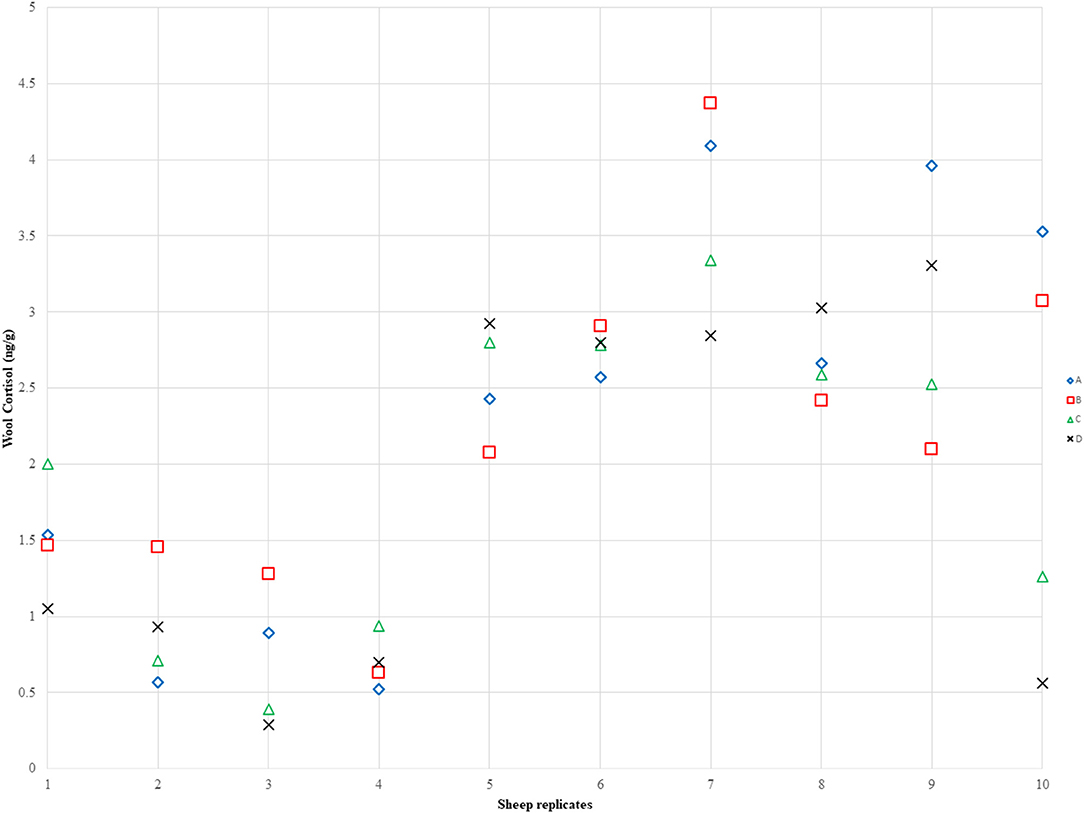

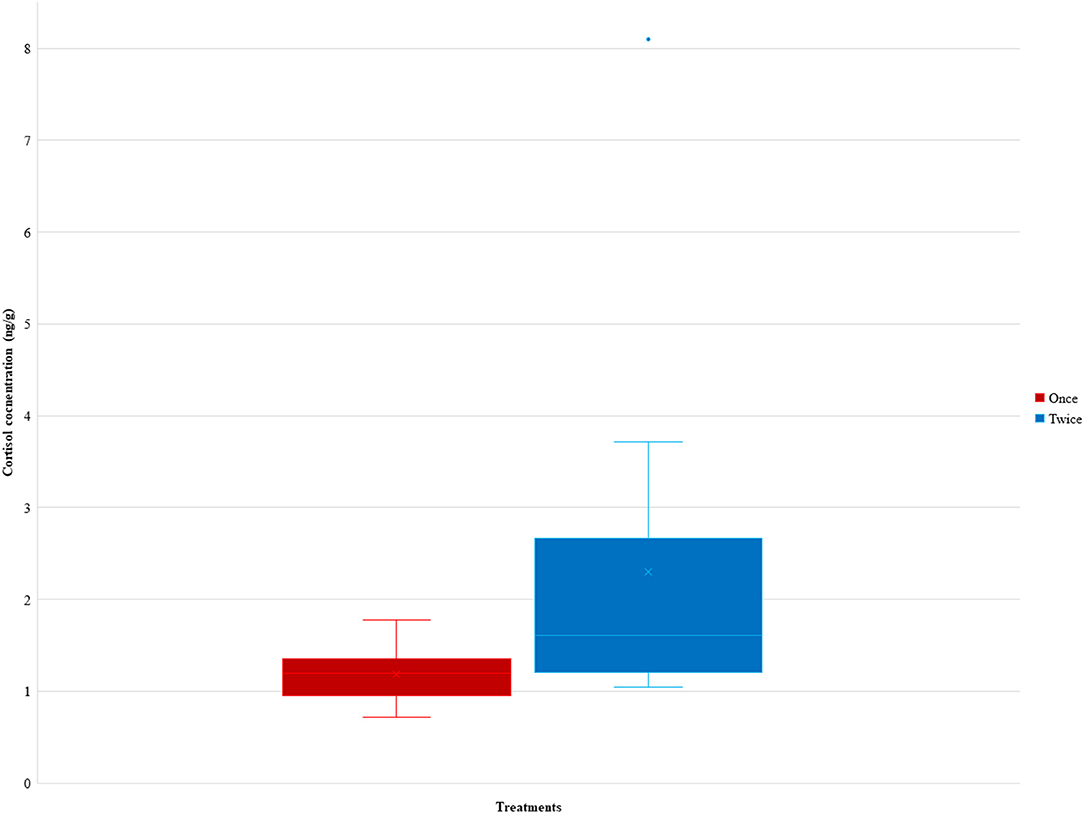

It was found that there was significant difference in the mean ng/g of the lambs between the Once and Twice shorn groups (t = −2.29, d.f. = 20, p = 0.033). As illustrated in Figure 4, the cortisol concentration of the lambs in the once shorn treatment was on average 1.188 ± 0.114 ng/g (SE) with a range of 0.716–1.773 ng/g, for those in the twice shorn treatment it was on average 2.304 ± 0.497 ng/g (SE) with a range 1.041–8.096 ng/g, and the overall average was 1.746 ng/g.

Figure 4. The ranges and average cortisol concentrations (ng/g) between the Once and Twice shorn groups of the 19 samples. The ranges and average cortisol concentrations (ng/g) between the Once and Twice shorn groups of the 19 samples. Level of significant difference was p = 0.03.

This is the first study to our knowledge that uses the topknot of Merino lambs to assess their absolute wool cortisol concentrations. In agreement with intra-sample variance experiments in feces (Scherpenhuizen, 2015), the results of the first experiment indicate that it did not matter which part of the same sample each subsample was collected from, as there was no statistical difference between subsamples, and therefore, only a small (handful) wool sample would be required in future studies in wool embedded cortisol, as long as it is collected from the same location on each animal. There was a significant difference in cortisol concentrations between samples, which was to be expected as cortisol concentrations vary between individuals mostly due to intra-specific metabolic variability (Mormède et al., 2011; Guindre-Parker, 2020).

In the second experiment, the results of the shearing experiment showed that there was a statistical difference in the cortisol concentrations between the offspring of the shearing treatments, with the lambs born to the twice shorn females having on average slightly higher levels compared to the lambs born to the ewes in the once shorn treatment. It is not clear whether the slightly higher cortisol would benefit or hinder the lambs later in life, however, different studies have shown that animals with higher cortisol concentrations in response to a stimulus tended to be more resilient, and in young animals in particular, higher cortisol levels have been shown to aid in survival (Leenhouwers et al., 2002; Michel et al., 2007; Knott et al., 2008; Mormède et al., 2011). It is important to note that the cortisol concentrations of the first and second experiment did not differ substantially, so further studies in cortisol in lambs should be conducted, which was also recommended by a recent study investigating different ways of measuring cortisol in lamb wool (Peric et al., 2020).

It should be noted that the crosstalk between the maternal-fetal axis is complex and the timing of exposure to cortisol from the placenta to fetus is important in gestation and birthing. The literature indicates that during pregnancy the crosstalk between the maternal and fetal HPA-axis continually operates to achieve homeostasis (Connor et al., 2009; Davis and Sandman, 2010). Early on during pregnancy, the enzyme 11Beta Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase 2 (11β-HSD2) converts cortisol to cortisone (Connor et al., 2009; Davis and Sandman, 2010). Excessive increases in cortisol in early pregnancy can be harmful to the fetus, however, in-situ cortisol production toward parturition is important for fetal development of crucial organ systems (e.g., lungs) (Hacking et al., 2001; Connor et al., 2009; Davis and Sandman, 2010). Therefore, toward the third trimester there is a sharp drop in 11β-HSD2 enabling higher proportions of maternal cortisol to reach to the fetus (Giannopoulos et al., 1982; Murphy et al., 2006; Connor et al., 2009; Davis and Sandman, 2010). The fetus is capable of producing endogenous cortisol and responding to exogenous cortisol during gestation, but not during the period of 90–120 days of gestation, during which high concentrations of external glucocorticoids has been shown to negatively impact the growth, organ development, and survival chances of the fetus (Wintour et al., 1995). Therefore, the timing of the exposure of maternal cortisol to the fetus plays an important role in the reproduction outcome in term of fetal development and health (Lowy et al., 1994; Uno et al., 1994; Welberg and Seckl, 2001; Connor et al., 2009; Davis and Sandman, 2010). More detailed review of the HPA-axis withregards to sheep reproduction is available in these papers (Bates et al., 1999; Tilbrook et al., 1999a,b; Möstl and Palme, 2002; Tilbrook and Clarke, 2006; McDowall et al., 2013; Wojtas et al., 2014; Ralph et al., 2016; Burnard et al., 2017; Narayan and Parisella, 2017; Narayan et al., 2018; Tilbrook and Ralph, 2018; Narayan, 2019; Sawyer and Narayan, 2019; McManus et al., 2020).

Previous studies in other infant animals (calves, foals, macaques, piglets) have shown that there were higher levels of cortisol in their fur, which have been associated with the elevated levels of cortisol in the mother during the late gestation phase, which may be why the lambs in the twice shearing treatment had a higher average cortisol concentration than the once in the single shearing treatment group (Montillo et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2017; Heimbürge et al., 2020). In addition, it has been found that juvenile animals have lower levels of corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG) and higher levels of plasma cortisol levels, which stabilize later in life, and could also be a contributing factor for the elevated cortisol levels in the lambs of this study (Grant et al., 2017; Heimbürge et al., 2020).

One of the major limitations of this study was the limited sample size, which was the result of several factors, and resulted in eight lambs been identified as part of the once shorn treatment and 15 lambs on the twice shorn treatment. If this experiment was to be replicated, a significantly larger number of ewes should be used and monitored more extensively, in order for every lamb to be successfully tagged immediately after birth. This would ensure that more lambs are matched with their biological mothers, and therefore with the treatment group the ewes are allocated to. In a future improved experiment of this nature, it would be interesting to monitor the cortisol levels and wool quality of the lambs born under the different treatments throughout their lives. If benefits were observed on the offspring of ewes that were sheared once before and once during gestation, it would then be interesting to conduct this experiment through several generations of sheep.

Our findings are consistent with those of Sawyer et al. (2021) as to the use of the topknot for wool cortisol analysis, as we did not find any cortisol variation between samples of the same sub-sample. Additionally, lambs whose mothers were shorn both before and during gestation had higher average cortisol concentration than lambs whose mothers were shorn only once before gestation, which according to studies in other young animals, may aid in their survival. We recommend that further research is conducted in the effects of maternal factors on lamb stress, as well as on normal cortisol ranges for young lambs.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

This research was originally approved by Western Sydney University ACEC Protocol (A12610) which was later ratified by The University of Queensland ACEC Approval Protocol (SAFS/544/19).

EN conceptualized the research and collaborated with GS and AT to supervise G-CH. G-CH conducted the lab work under the supervision of EN. G-CH wrote the original manuscript with expert comments from EN, AT, and GS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Australian Wool Education Trust scholarship for Undergraduate Projects and Masters by Coursework and Australian Wool Innovation research funding and NSW Stud Merino Breeders Association Funding to EN.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Many thanks to colleagues Harsh Pahuja and Dr. Vincent Mellor for their help during the research and data analysis of this project.

Ansari-Renani, H. R., and Hynd, P. I. (2001). Cortisol-induced follicle shutdown is related to staple strength in Merino sheep. Livestock Prod. Sci. 69, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(00)00253-0

Bates, E. J., Penno, N. M., and Hynd, P. I. (1999). Wool follicle matrix cells: culture conditions and keratin expression in vitro. Br. J. Dermatol. 140, 216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1999.02652.x

Burnard, C., Ralph, C., Hynd, P., Hocking Edwards, J., and Tilbrook, A. (2017). Hair cortisol and its potential value as a physiological measure of stress response in human and non-human animals. Anim. Prod. Sci. 57, 401–414. doi: 10.1071/AN15622

Connor, K. L., Challis, J. R., Van Zijl, P., Rumball, C. W., Alix, S., Jaquiery, A. L., et al. (2009). Do alterations in placental 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11betaHSD) activities explain differences in fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) function following periconceptional undernutrition or twinning in sheep? Reprodu. Sci. 16, 1201–1212. doi: 10.1177/1933719109345162

Davenport, M. D., Tiefenbacher, S., Lutz, C. K., Novak, M. A., and Meyer, J. S. (2006). Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 147, 255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.01.005

Davis, E. P., and Sandman, C. A. (2010). The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associated with human infant cognitive development. Child Dev. 81, 131–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01385.x

Giannopoulos, G., Jackson, K., and Tulchinsky, D. (1982). Glucocorticoid metabolism in human placenta, decidua, myometrium and fetal membranes. J. Steroid Biochem. 17, 371–374. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(82)90628-8

Gonzalez, E. B., Sacchero, D. M., and Easdale, M. H. (2020). Environmental influence on Merino sheep wool quality through the lens of seasonal variations in fibre diameter. J. Arid Environ. 181, 104248. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104248

Grant, K. S., Worlein, J. M., Meyer, J. S., Novak, M. A., Kroeker, R., Rosenberg, K., et al. (2017). A longitudinal study of hair cortisol concentrations in Macaca nemestrina mothers and infants. Am. J. Primatol. 79, e22591. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22591

Guindre-Parker, S. (2020). Individual variation in glucocorticoid plasticity: considerations and future directions. Integr. Comp. Biol. 60, 79–88. doi: 10.1093/icb/icaa003

Hacking, D., Watkins, A., Fraser, S., Wolfe, R., and Nolan, T. (2001). Respiratory distress syndrome and antenatal corticosteroid treatment in premature twins. Arch. Dis. Child. 85, F77–F78. doi: 10.1136/fn.85.1.F75g

Hargreaves, A. L., and Hutson, G. D. (1990). Changes in heart rate, plasma cortisol and haematocrit of sheep during a shearing procedure. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 26, 91–101. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(90)90090-Z

Heimbürge, S., Kanitz, E., Tuchscherer, A., and Otten, W. (2020). Within a hair's breadth – factors influencing hair cortisol levels in pigs and cattle. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 288, 113359. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.113359

Hernández-Cruz, B. C., Carrasco-García, A. A., Ahuja-Aguirre, C., López-Debuen, L., Rojas-Maya, S., and Montiel-Palacios, F. (2016). Faecal cortisol concentrations as indicator of stress during intensive fattening of beef cattle in a humid tropical environment. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 48, 411–415. doi: 10.1007/s11250-015-0966-5

Kelly, R., MacLeod, I., Hynd, P., and Greeff, J. (1996). Nutrition during fetal life alters annual wool production and quality in young Merino sheep. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 36, 259–267. doi: 10.1071/EA9960259

Knott, S. A., cummins, L. J., Dunshea, F. R., and Leury, B. J. (2008). Rams with poor feed efficiency are highly responsive to an exogenous adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) challenge. Domest. Anima. Endocrinolo. 34, 261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2007.07.002

Leenhouwers, J. I., Knol, E. F., De Groot, P. N., Vos, H., and Van Der Lende, T. (2002). Fetal development in the pig in relation to genetic merit for piglet survival1. J. Anim. Sci. 80, 1759–1770. doi: 10.2527/2002.8071759x

Lowy, M. T., Wittenberg, L., and Novotney, S. (1994). Adrenalectomy attenuates kainic acid-induced spectrin proteolysis and heat shock protein 70 induction in hippocampus and cortex. J. Neurochem. 63, 886–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030886.x

Macé, T., González-García, E., Carrière, F., Douls, S., Foulqui,é, D., Robert-Granié, C., et al. (2019). Intra-flock variability in the body reserve dynamics of meat sheep by analyzing BW and body condition score variations over multiple production cycles. Animal 13, 1986–1998. doi: 10.1017/S175173111800352X

McDowall, M. L., Edwards, N. M., and Hynd, P. I. (2011). The effects of short-term manipulation of thyroid hormone status coinciding with primary wool follicle development on fleece characteristics in Merino sheep. Animal 5, 1406–1413. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111000383

McDowall, M. L., Watson-Haigh, N. S., Edwards, N. M., Kadarmideen, H. N., Nattrass, G. S., Mcgrice, H. A., et al. (2013). Transient treatment of pregnant Merino ewes with modulators of cortisol biosynthesis coinciding with primary wool follicle initiation alters lifetime wool growth. Anim. Prod. Sci. 53, 1101–1111. doi: 10.1071/AN12193

McManus, C. M., Faria, D. A., Lucci, C. M., Louvandini, H., Pereira, S. A., and Paiva, S. R. (2020). Heat stress effects on sheep: are hair sheep more heat resistant? Theriogenology 155, 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.05.047

Meyer, J., Novak, M., Hamel, A., and Rosenberg, K. (2014). Extraction and analysis of cortisol from human and monkey hair. J. Vis. Exp. 24:e50882. doi: 10.3791/50882

Michel, V., Peinnequin, A., Alonso, A., Buguet, A., Cespuglio, R., and Canini, F. (2007). Decreased heat tolerance is associated with hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenocortical axis impairment. Neuroscience 147, 522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.035

Montillo, M., Comin, A., Corazzin, M., Peric, T., Faustini, M., Veronesi, M. C., et al. (2014). The effect of temperature, rainfall, and light conditions on hair cortisol concentrations in newborn foals. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 34, 774–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2014.01.011

Mormède, P., Foury, A., Terenina, E., and Knap, P. W. (2011). Breeding for robustness: the role of cortisol*. Animal 5, 651–657. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110002168

Morrow, C. J., Kolver, E. S., Verkerk, G. A., and Matthews, L. R. (2002). Fecal Glucocorticoid metabolites as a measure of adrenal activity in dairy cattle. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 126, 229–241. doi: 10.1006/gcen.2002.7797

Möstl, E., and Palme, R. (2002). Hormones as indicators of stress. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 23, 67–74. doi: 10.1016/S0739-7240(02)00146-7

Murphy, V. E., Smith, R., Giles, W. B., and Clifton, V. L. (2006). Endocrine regulation of human fetal growth: the role of the mother, placenta, and fetus. Endocr. Rev. 27, 141–169. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0011

Narayan, E. (2019). “Introductory chapter: applications of stress endocrinology in wildlife conservation and livestock science,” in Comparative Endocrinology of Animals, ed E. Narayan (London: IntechOpen).

Narayan, E., and Parisella, S. (2017). Influences of the stress endocrine system on the reproductive endocrine axis in sheep (Ovis aries). Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 16, 640–651. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2017.1321972

Narayan, E., Sawyer, G., Fox, D., Smith, R., and Tilbrook, A. (2022). Interplay between stress and reproduction: Novel epigenetic markers in response to shearing patterns in Australian Merino sheep (Ovis aries). Front. Vet. Sci, 9, 830450. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.830450

Narayan, E., Sawyer, G., and Parisella, S. (2018). Faecal glucocorticoid metabolites and body temperature in Australian merino ewes (Ovis aries) during summer artificial insemination (AI) program. PLoS ONE 13, e0191961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191961

Nejad, J. G., Lohakare, J. D., Son, J. K., Kwon, E. G., West, J. W., and Sung, K. I. (2014). Wool cortisol is a better indicator of stress than blood cortisol in ewes exposed to heat stress and water restriction. Animal 8, 128–132. doi: 10.1017/S1751731113001870

Nejad, J. G., Park, K.-H., Forghani, F., Lee, H.-G., Lee, J.-S., and Sung, K.-I. (2020). Measuring hair and blood cortisol in sheep and dairy cattle using RIA and ELISA assay: a comparison. Biol. Rhythm Res. 51, 887–897. doi: 10.1080/09291016.2019.1611335

Oddy, V. (1999). Genetic variation in protein metabolism and implications for variation in efficiency of growth. Recent Adv. Anim. Nutr. Aust. 12, 23–29.

Peric, T., Comin, A., Corazzin, M., Montillo, M., and Prandi, A. (2020). Comparison of AlphaLISA and RIA assays for measurement of wool cortisol concentrations. Heliyon 6, e05230. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05230

Ralph, C. R., Lehman, M. N., Goodman, R. L., and Tilbrook, A. J. (2016). Impact of psychosocial stress on gonadotrophins and sexual behaviour in females: role for cortisol? Reproduction 152, R1–R14. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0604

Sawyer, G., Fox, D. R., and Narayan, E. (2021). Pre- and post-partum variation in wool cortisol and wool micron in Australian Merino ewe sheep (Ovis aries). PeerJ 9, e11288. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11288

Sawyer, G., and Narayan, E. J. (2019). “A review on the influence of climate change on sheep reproduction,” in Comparative Endocrinology of Animals, ed E. Narayan (London: IntechOpen). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.86799

Sawyer, G., Webster, D., and Narayan, E. (2019). Measuring wool cortisol and progesterone levels in breeding maiden Australian Merino Sheep (Ovis aries). PLoS ONE 14, e0214734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214734

Scherpenhuizen, J. M. (2015). Non-Invasive Evaluation of Physiological Stress in Sheep (Ovis aries): Intra-Sample Variation, Metabolite Stability and Responses to Environmental Stressors. School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, NSW, Wagga wagga, Australia.

Scobie, D. R., and Hynd, P. I. (1995). Reduction of mitotic rate in the wool follicle by cortisol. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 46, 319–331. doi: 10.1071/AR9950319

Thompson, A. C. T., Hebart, M. L., Penno, N. M., and Hynd, P. I. (2007). Perinatal wool follicle attrition coincides with elevated perinatal circulating cortisol concentration in Merino sheep. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 58, 748–752. doi: 10.1071/AR06327

Tilbrook, A. J., Canny, B. J., Serapiglia, M. D., Ambrose, T. J., and Clarke, I. J. (1999a). Suppression of the secretion of luteinizing hormone due to isolation/restraint stress in gonadectomised rams and ewes is influenced by sex steroids. J. Endocrinol. 160, 469–481. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600469

Tilbrook, A. J., Canny, B. J., Stewart, B. J., Serapiglia, M. D., and Clarke, I. J. (1999b). Central administration of corticotrophin releasing hormone but not arginine vasopressin stimulates the secretion of luteinizing hormone in rams in the presence and absence of testosterone. J. Endocrinol. 162, 301–311. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1620301

Tilbrook, A. J., and Clarke, I. J. (2006). Neuroendocrine mechanisms of innate states of attenuated responsiveness of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis to stress. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 27, 285–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.06.002

Tilbrook, A. J., and Ralph, C. R. (2018). Hormones, stress and the welfare of animals. Anim. Prod. Sci. 58, 408–415. doi: 10.1071/AN16808

Uno, H., Eisele, S., Sakai, A., Shelton, S., Baker, E., Dejesus, O., et al. (1994). Neurotoxicity of glucocorticoids in the primate brain. Horm. Behav. 28, 336–348. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1030

Weaver, S. J., Hynd, P. I., Ralph, C. R., Hocking Edwards, J. E., Burnard, C. L., Narayan, E., et al. (2021). Chronic elevation of plasma cortisol causes differential expression of predominating glucocorticoid in plasma, saliva, fecal, and wool matrices in sheep. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 74, 106503. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2020.106503

Welberg, L. A., and Seckl, J. R. (2001). Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of the brain. J. Neuroendocrinol. 13, 113–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2001.00601.x

Wintour, E. M., Crawford, R., Mcfarlane, A., Moritz, K., and Tangalakis, K. (1995). Regulation and function of the fetal adrenal gland in sheep. Endocr. Res. 21, 81–89. doi: 10.3109/07435809509030423

Keywords: sheep, stress, wool, individual variation, reproduction, shearing, welfare

Citation: Hantzopoulou G-C, Sawyer G, Tilbrook A and Narayan E (2022) Intra- and Inter-sample Variation in Wool Cortisol Concentrations of Australian Merino Lambs Between Twice or Single Shorn Ewes. Front. Anim. Sci. 3:890914. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2022.890914

Received: 07 March 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Vishwajit S. Chowdhury, Kyushu University, JapanReviewed by:

Jalil Ghassemi Nejad, Konkuk University, South KoreaCopyright © 2022 Hantzopoulou, Sawyer, Tilbrook and Narayan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Edward Narayan, ZS5uYXJheWFuQHVxLmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.