- 1Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States

- 2Charles Schwab Corporation, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 3EDHEC Business School, Nice, France

In complete markets there are risky assets and a riskless asset. It is assumed that the riskless asset and the risky asset are traded continuously in time and that the market is frictionless. In this paper, we propose a new method for hedging derivatives assuming that a hedger should not always rely on trading existing assets that are used to form a linear portfolio comprised of the risky asset, the riskless asset, and standard derivatives, but rather should design a set of specific, most-suited financial instruments for the hedging problem. We introduce a sequence of new financial instruments best suited for hedging jump-diffusion and stochastic volatility market models. The new instruments we introduce are perpetual derivatives. More specifically, they are options with perpetual maturities. In a financial market where perpetual derivatives are introduced, there is a new set of partial and partial-integro differential equations for pricing derivatives. Our analysis demonstrates that the set of new financial instruments together with a risk measure called the tail-loss ratio measure defined by the new instrument’s return series can be potentially used as an early warning system for a market crash.

1. Introduction

In complete markets there are risky assets (such as stocks) and a riskless asset (such as government-guaranteed bond). The risky asset and the riskless asset are traded continuously in time and the market is assumed to be frictionless. These assets are referred to as “basic assets”. Given a derivative with underlying assets being the risky and riskless asset, the derivative price is spanned over the risky asset’s prices and the riskless asset’s price. That is, contingent pricing theory tells us that the derivative price process is replicated by the price process of a self-financing portfolio consisting of these existing assets.

In this paper we introduce new risky assets which we propose as trading assets (i.e., available for trade continuously in time). The proposed new risky assets will be new assets if they are accepted by the market as tradable assets. These new assets are perpetual options (i.e., options with perpetual maturities). Because the proposed perpetual derivatives incorporate information about the underlying risky asset, a riskless asset, and the underlying risky asset’s volatility, they could potentially be of greater interest to market participants than the underlying asset itself. In a way, our perpetual financial instruments are portfolios driven by the underlying risky asset, and we suggest it as a potentially tradable product. We believe that introducing this new set of financial instruments will contribute to enhancing market efficiency. Since real markets are not complete, the introduction of the proposed financial instruments would benefit real financial markets.

Of course, a natural question is that in complete markets there are already contingent claims traded (calls and puts), so why is it necessary to have new financial instruments for spanning? The answer is simple. This is because existing traded options have a time to maturity and their value depends critically on the time to maturity. A preferred hedging instrument should only depend on 1) the current time, 2) current value of the underlying asset, 3) the prevailing riskless interest rate, and 4) the current value of the asset’s volatility. It should not depend on the option’s time to maturity. That is the critical feature of the set of new financial instruments we propose here, options with infinite maturity. We believe that the new financial instruments we propose in this paper will motivate market participants to recommend to exchanges to design such contracts to help facilitate more efficient trading.

In creating the new financial instruments, we use the basic framework that any asset in a complete market can be replicated by existing assets. In the classical Black-Scholes-Merton (BSM) model (see Refs. 1 and 9), the price of a risky asset is driven by geometric Brownian motion and the riskless asset. In the classical BSM model, one set of basic assets is the riskless asset and the underlying risky asset. In this paper, we will show that our new financial instrument is a basic asset. The new financial instrument, together with the riskless asset and the underlying risky asset, span any derivative in the BSM model.

So our new financial instrument can and should be replicated by basic assets. Thus, if the new financial instrument is available for trade as is the underlying asset, the seller of our perpetual derivative can form a replicating portfolio so that a trader is constantly able to hedge the risk exposure by investing in the risky asset. That is why we view our new financial instrument (as any risky asset in a complete market) both as an asset to be bought (taking a long position) and at the same time to be sold (and thus replicated using a perfect hedged replicating portfolio).

Extensions of the classical BSM framework allow for stochastic volatility and jump risk in the price process which make the market incomplete. For example, Merton [10] introduces a jump-diffusion model and uses a short cut by averaging the jump risk noting that his model is not equivalent to an equilibrium model. Yet, we show that Merton’s model becomes complete if we introduce a special bond with a maturity being the first arrival (default time) of a Poisson process jump. In our paper we continue Merton’s line of research by discussing how this new special bond should be used for hedging and in doing so we derive a new partial differential equation for any contingent claim that will make the market complete.

With respect to volatility markets, such markets are incomplete markets in the sense that they too introduce two sets of risk: price risk and volatility risk. However, if the volatility of the asset is traded, the local volatility market becomes complete. Furthermore, if the volatility of volatility is traded, then we have four traded assets (underlying risks asset, volatility, volatility of volatility, and riskless asset) forming a complete market within the local volatility market model. Currently market participants employ the CBOE’s VIX1 (as volatility of SPDR2) and VVIX3 (as volatility of VIX) as traded assets (assets available for trade). In our paper we derive the partial differential equations for derivatives that will make the market complete.

Our general methodology, namely, to search for hedging instruments that are most suited for hedging problems is applied to three classical problems associated with option pricing models. First, we apply our model to continuous-time BSM markets. We derive a new set of perpetual derivatives which can be as a potentially tradable product. We also extend this approach to multi-asset markets (following general multivariate Itô processes). Further, we explain and evaluate market risk before and during the recent distressed market period by using the new perpetual derivative. We demonstrate that the new perpetual derivative, together with a risk measure which we refer to as the tail-loss ratio (TLR), was capable of explaining and evaluating market risk before and during the potential distressed market period. We present the TLR index for the new perpetual derivative and the SPDR S&P 500 index for the period from 2000–2018. We assess the forecasting performance of the new perpetual derivative by comparing the TLR index with the TLR index for the SPDR S&P 500 index. Our empirical evidence suggests that the TLR derived by the new financial instrument we propose performs well in predicting a real-world market crash.

The second problem associated with option pricing models that we tackle in this paper deals with hedging in Merton’s jump-diffusion option pricing model (see Ref. 10). Here the classical approach is to use a riskless asset and the stock, but since these two instruments cannot be used to hedge jump risk, this risk is left unhedged. Now we again apply our general framework to answer the following question: What kind of tradable (possibly non-linear) financial instrument is best suited for designing a hedging strategy to eliminate jump risk? Following the approach by Ref. 13; we answer the question and thus derive an analogue of Merton’s partial integro-differential equation (PIDE) for the derivative price of a fully hedged portfolio.

Our third application of the proposed approach is hedging in the presence of stochastic volatility. Here there are two sources of uncertainty: market risk and volatility risk. Although market risk is readily hedged by trading the underlying asset, attempting to hedge volatility risk requires an additional derivative with a longer maturity than the option that the hedger seeks to hedge. This approach creates a vicious circle in that the hedger is trying to hedge an option using another option for which the hedger does not know its contract value. Thus, an analogue of the market risk premium is introduced (generally understood as the volatility risk premium), which now enters the model as a parametric function which should be potentially calibrated. Instead, following the approach suggested by Ref. 4; we take a different approach by posing the question of the most suitable tradable instrument for that hedging problem and describe the nature of the volatility risk premium by applying the Consumption Capital Asset Pricing Model (CCAPM) formulated by Ref. 2.

This is the essence of our methodology: in an incomplete market, we do not leave the risk premia from different risk factors as unknown functions (which should be eventually estimated or calibrated). Rather we select the best suited financial instruments, that should be introduced as publicly traded assets. These new assets should make the underlying market complete. Furthermore, even if the market is complete, we identify various spanning bases of assets, best suitable for the hedging problem under consideration.

We can sum up our methodology based on the following idea: Every hedging problem has its own set of most-suited (“ideal”) set of hedging instruments. There is no universal hedging instrument, as there is no universal hedging problem.4 Furthermore, ideal hedging instruments cannot make a bad model good; an intrinsically bad model cannot be made acceptable with any enhancements.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we introduce a new set of perpetual derivatives that will serve as the basis assets in hedging portfolios. In Section 3, we apply our general methodology to determine what kind of tradable financial instrument is best suited for the problem of eliminating the jump risk in Merton’s jump-diffusion model. The solution is to use a new financial instrument, which can be viewed as an interest-bearing bond where the interest payments occurr at Poisson arrivals. The next application of the general method is hedging within a stochastic volatility model. In Section 4 we show that volatility indexes should be used as desirable hedging instruments. In all applications, the corresponding analogues of the Black-Scholes and Merton’s equations are derived. In Section 5 the TLR indices of the new perpetual derivative and SPDR S&P 500 (an exchange-traded fund) index are presented and the results then compared. The proofs are given in the Appendix.

2. A Class of “Ideal” Perpetual Derivatives

Consider the classical Black-Scholes-Merton BSM-framework.

a) a risky asset (stock) with price dynamics given by

on a stochastic basis

b) a riskless bond given by

where r is the risk-free rate;

c) A European contingent claim (ECC) with price process

Under the equivalent martingale measure (EMM)

Proposition 2.1. Let

We note that the assumption that

Of interest is the perpetual derivative

Consider now the multidimensional case7:

on a stochastic basis

is assumed complete.

Proposition 2.2 Assume that Eqs 4 and 5 hold. Let

3. Eliminating Jump Risk in Merton’s Jump-Diffusion Pricing Model

Consider Merton’s jump diffusion model [10] in which there is a stock and riskless bank account with stock price dynamics

defined on a stochastic basis

• a standard Brownian motion

• a homogeneous Poisson process

• independent of

where

Consider a ECC with a contract value

Proposition 3.1. [10]:

We derive Eq. 8 by applying the CCAPM as a simple illustration of the methodology that we will apply in more general cases as shown in the Appendix. We believe that this proof is well-known, but could not find it in the literature.

In Proposition 3.1 the jump-risk is left unhedged. This is because Merton’s jump-diffusion framework lacks a security that is publicly available for trading (designated as

Here we again illustrate our approach to achieving market completeness: i) find the most suitable hedge instruments in the market for the hedging problem under consideration, and ii) if the market does not provide such special hedging instruments, then introduce them as publicly traded assets and let the market price them.

In the context of asset price models, Ref. 13 showed that completed market models with a unique martingale measure are complete also in the sense of hedging, if there are only a finite number of marks for the jumping component (there is a finite number of sources of randomness). However, if there are an infinite number of marks (an infinite number of sources of randomness), Ref. 13 showed that the completed market models with a unique martingale measure are only approximately complete in the sense of hedging.

Following the approach in Ref. 13; we introduce the dynamic price process of

We view

Having the bond, the stock and the new asset

Consider then an ECC written against the stock, with price process

Proposition 3.2. Under assumptions Eqs 6, 8, and 9,

For

As a corollary of Proposition 3.2, it follows that asset

A natural extension of Merton’s model is to assume that the jump dynamics can be potentially dependent on the stock price itself

defined on a stochastic basis

Consider a ECC with price process

Proposition 3.3. Under the assumptions (11), (12), and (12),

4. Hedging Volatility Risk in a Stochastic Volatility Option Pricing Model

To demonstrate how to hedge the volatility risk in a stochastic volatility option pricing model, we use the same setting as in Section 2. However, in this case we assume that he publicly traded stock price dynamic are determined by a stochastic volatility model with mean-reverting Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process given by9

where

Let

for all

The objective in this section is to derive a PDE for the price of an ECC in which together with market risk, volatility risk is also expressed in tradeable volatility indexes, and thus the function

Next, we follow our basic approach of introducing an additional security as a publicly traded asset to achieve market completeness. Following the approach by Ref. 4; we assume that in the stochastic volatility market model, defined by Eqs 15–17, and consisting of a stock and riskless bond, an additional security

A trader, having available a traded asset, the bond, the stock and

First, for a better understanding of the stochastic volatility model we shall prove Eq. 18 using the CCAPM:

where

Proposition 4.1. Under the assumptions Eqs 15–1719–21, the ECC-price process

where

First, it should be noted, that if the stock’s volatility is a security

with

Proposition 4.2 [4]. Under the assumptions Eqs 15–17, 23, and 24, the ECC-price process

The proof of the proposition follows the same arguments as Proposition 3.311 and thus is omitted.

Within the stochastic volatility model suggested by Ref. 7; if

Proposition 4.1 leads to the following generalization of the stochastic volatility model. Let us remark here that trading volatility options is gaining popularity, and involves models for volatility options in which the “volatility of the volatility” (designated as vol-of-vol, or shortly,

The

Let

Following standard no-arbitrage arguments leads to the PDE for the ECC-price process:

Next we can extend the example of the use of CCAPM in the previous section by applying CCAPM not only to the stock, derivative, and the volatility security

Applying the same arguments as in the previous section results in the following PDE:

where

It is natural to seek an extension of stochastic volatility models Eq. 30 allowing for jumps in the stock price. We suggest the following one:

The triplet

The riskless bond dynamics are given by Eq. 2.

Then following the definitions of the new publicly traded assets introduced in this and the previous section, we define a hedging portfolio with the following dynamics:

where

The corresponding PDE for

5. Empirical Analysis

In this section we apply the new trading instrument we proposed in this paper to explain and evaluate market risk before and during an actual distressed market period. A standard risk measure must be employed to measure financial industries and market risk. The two measures we selected are Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional VaR (CVaR) because they are the two most popular risk measures used in the finance industry. CVaR, also called expected tail risk, is the average of VaRs less than the VaR for a given tail probability. CVaR satisfies all attributes of a coherent risk measure and is consistent with performance relations of risk-averse investors (see Ref. 11).

TLR has been adapted as the risk measure to determine financial market behavior before and during the high volatility period we study later in this paper. For a given tail probability α, we define TLR

The idea of the tail-loss ratio is that the tail behavior of the return-distribution measured by the tail-loss can be used as a predictor of future market crashes. Ref. 8 discussed a particular dynamic model, ARMA (1,1)-GARCH (1,1) with tempered stable innovations (ARMA-GARCH-TS), for the stock price. They defined tail loss as the differences between

Of interest is the perpetual derivative

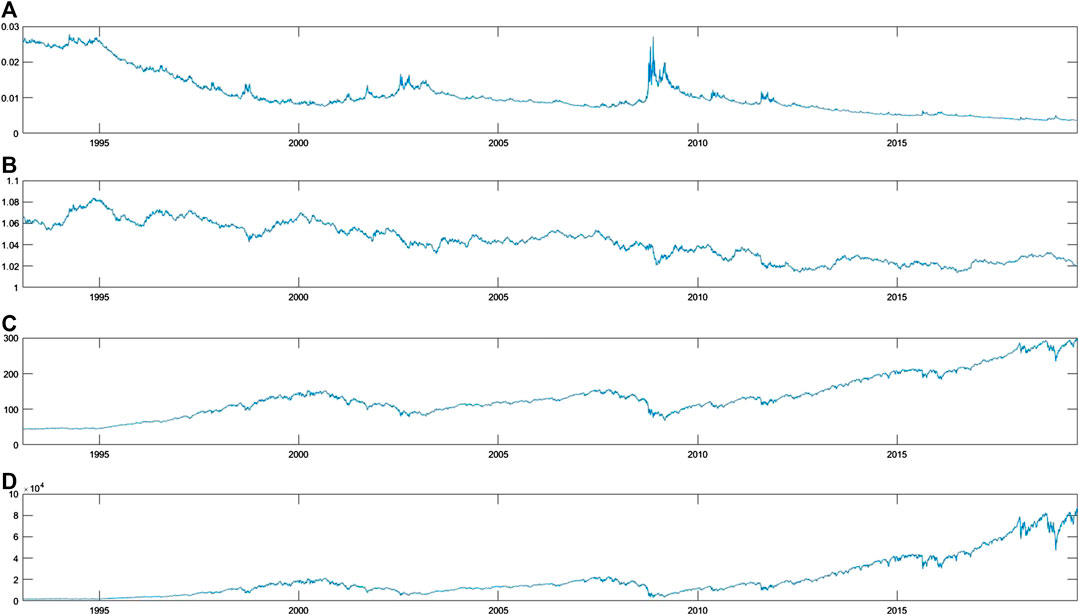

In Figure 1 the price process of the perpetual derivative

FIGURE 1. Daily time series process for the period from January 1993 to June 2019 for (A)

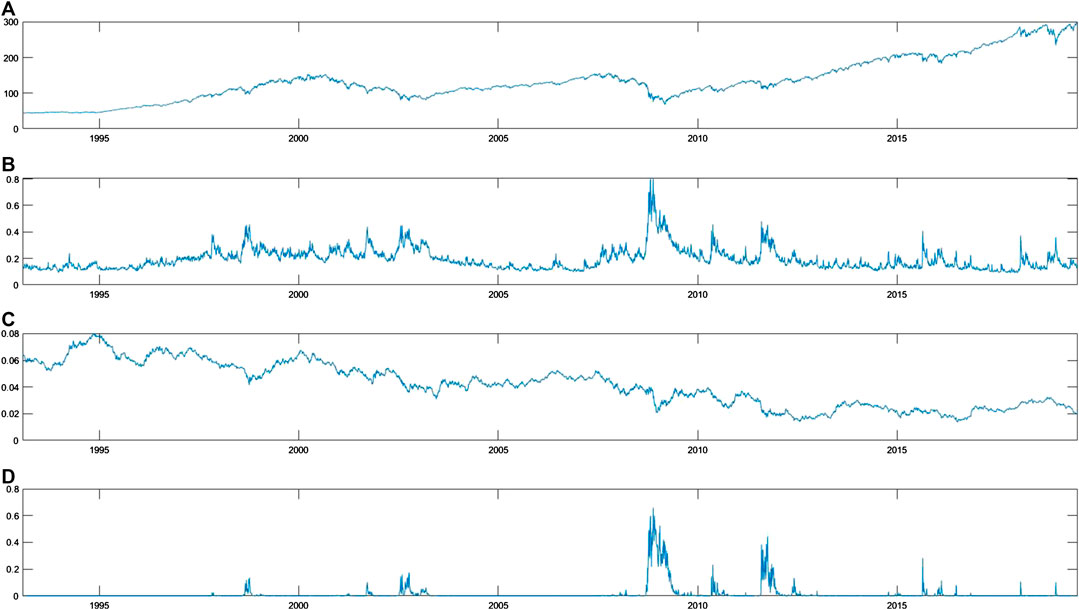

Figure 2 shows the time series price process of

FIGURE 2. Daily time series process for the period from January 1993 to June 2019 for (A) the SPDR S&P 500 index closing price

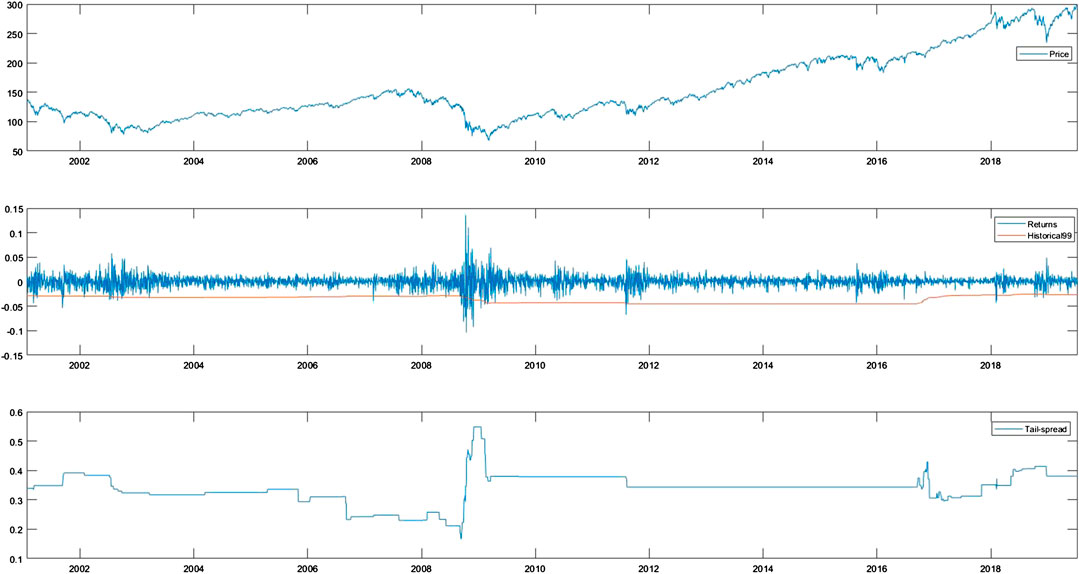

Next we calculate CVaR and VaR at

Empirical daily VaR and CVaR are estimated by using rolling windows time series analysis for a time period of eight years (i.e., 2016 trading days). Then, the TLR index for the daily log-return of

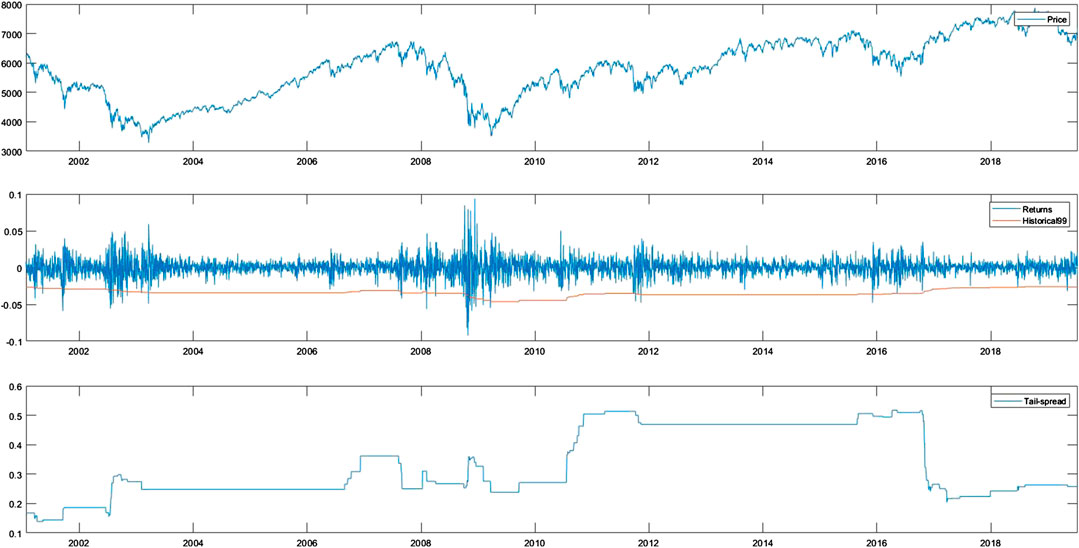

FIGURE 3. Daily time series process for the period from January 2001 to June 2019 for (A) the price process of SPDR S&P 500 index; (B) the log-return of SPDR S&P 500 index with emperical VaR(0.99), and; (C) the TLR index for SPDR S&P 500 index.

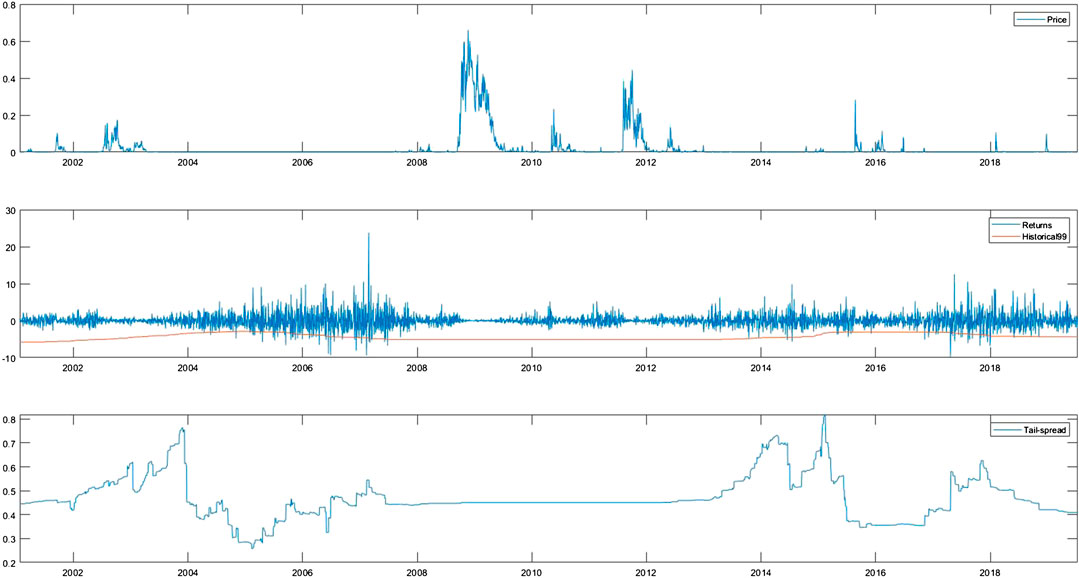

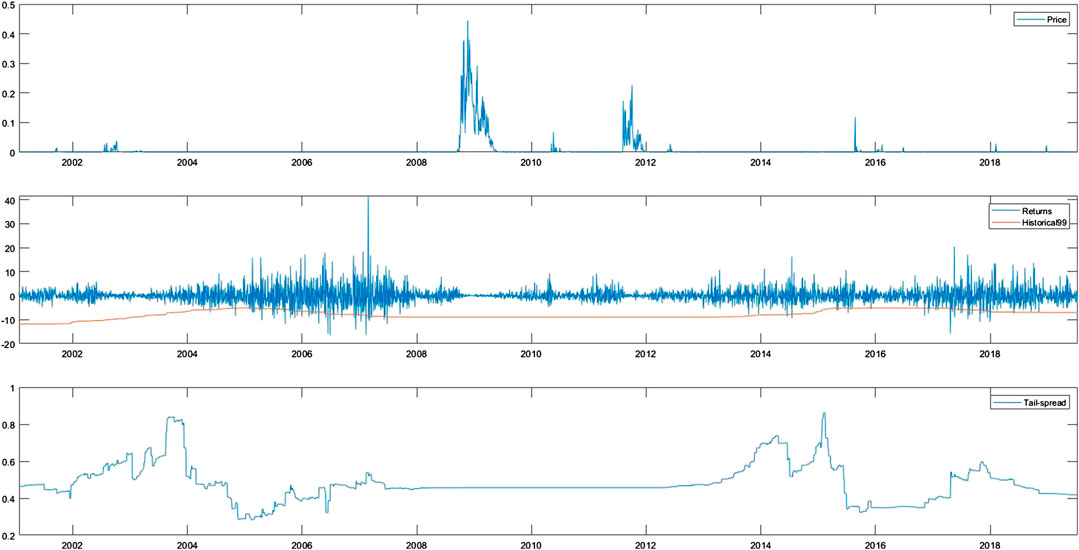

FIGURE 4. Daily time series process for the period from January 2001 to June 2019 for (A) the price process of the perpetual derivative index; (B) the log-return of the perpetual derivative index with emperical VaR(0.99), and; (C) the TLR index for the perpetual derivative index.

Comparing Figures 3, 4, one can graphically check the difference between the two TLR indices. In particular, the TLR index of

The TRS index of

As further empirical support of the predictive power of the TLR index for

FIGURE 5. Daily time series process for the period from January 2001 to June 2019 for (A) the price process of FTSE 100 index; (B) the log-return of FTSE 100 index with emperical VaR(0.99), and; (C) the TLR index for FTSE 100 index.

FIGURE 6. Daily time series process for the period from January 2001 to June 2019 for (A) the FTSE 100 price process of the perpetual derivative index; (B) the log-return of the FTSE 100 perpetual derivative index with emperical VaR(0.99), and; (C) the TLR index for the FTSE 100 perpetual derivative index.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we developed a novel approach to hedging derivatives by proposing the creation of a set of specially designed (“ideal”) publicly available perpetual derivatives. The set of new proposed assets - perpetual options - allow the option writer to form a hedging portfolio which 1) reduces the trading costs in markets with frictions; 2) removes the jump risk when the underlying price process is a jump-diffusion process, and; 3) removes the volatility risk when the underlying price process exhibits stochastic volatility. The corresponding PIDE and PDE for the derivative price processes are derived. The tail-loss ratio is used as the risk measure to determine financial market behavior prior to the market high volatility period we study in this paper. We demonstrate that the new financial instruments, together with the tail-loss ratio, have potential power in predicting and evaluating market risk before a distressed market period. Our findings suggest that the tail-loss ratio can be potentially used as a metric for an early warning system.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://finance.yahoo.com/.

Author Contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at Social Science Research Network [14] and arXiv [15].

APPENDIX

A.1. Proof of Proposition 2.1

Let

A.2. Proof of Proposition 2.2

For simplicity of the exposition we will consider the bivariate case only. First let us recall the Black-Scholes Equation in the bivariate case: The stocks dynamics is given by

Equating the terms for

A.3. Proof of Proposition 3.1

Applying CCAPM and making use of Merton’s assumption.

we have two expressions for

and

A.4. Proof of Proposition 3.2

Consider the self-financing trading strategy

A.5. Proof of Proposition 3.3

We seek a self-financing portfolio of the form

with similar expressions for

A.6. Proof of Proposition 4.1

Combining the expressions for.

and

with

which proves the proposition.

Footnotes

1VIX is an index created by the CBOE, representing 30-day implied volatility calculated from S&P500 options (see http://www.cboe.com/vix).

2See SPDR S&P 500 ETF Indices, https://us.sprdrs.com/.

3The VVIX is an index created by the CBOE (see http://www.cboe.com/products/vix-index-volatility/volatility-on-stock-indexes/the-cboe-vvix-index/vvix-whitepaper). It is a volatility of volatility (vol-of-vol) measure, and represents 30-day implied volatility calculated from VIX options.

4It is interesting to note that the renowned Russian mathematician Andrey N. Kolmogorov used to comment that every approximation problem in functional analyses and probability theory requires a specially designed distance measure (best-suited metric) in its solution [12]. Similarly, in hedging problems, the choice of the hedging instruments should not necessarily be the standard ones (the stock and the riskless asset), but the ones that best reflect the nature of the hedging problem.

5

6We denote

7See Sections 5.I and 6.I in Ref. 5 for the regularity and market completeness conditions.

8

10This approach was initially used in Refs. 1 and 5, Section 6.D).

12We view VIX (an index created by the CBOE, representing 30-day implied volatility calculated from S&P 500 options) as a proxy for publicly traded security

13See https://www.londonstockexchange.com/indices/ftse-100?lang=en.

References

1. Black, F, and Scholes, M. The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. J Polit Econ (1973). 81:637–54. doi:10.1086/260062.

2. Breeden, DT. An intertemporal asset pricing model with stochastic consumption and investment opportunities. J Financ Econ (1979). 7:265–96. doi:10.1016/0304-405x(79)90016-3.

4. Davis, M. Complete-market models of stochastic volatility. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci (2004). 460:11–26. doi:10.1098/rspa.2003.1233.

5. Duffie, D. Dynamic asset pricing theory. 3rd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2001).

6. Fouque, J, Papanicolaou, G, and Sircar, KR. Derivatives in financial markets with stochastic volatility. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press (2000). 222 p.

7. Heston, SL. A closed-form solution for options with stochastic volatility with applications to bond and currency options. Rev Financ Stud (1993). 6:327–43. doi:10.1093/rfs/6.2.327.

8. Kim, YS, Rachev, ST, Bianchi, ML, Mitov, I, and Fabozzi, FJ. Time series analysis for financial market meltdowns. J Bank Finance (2011). 35:1879–91. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.12.007.

9. Merton, RC. An intertemporal capital asset pricing model. Econometrica (1973). 41:867–87. doi:10.2307/1913811.

10. Merton, RC. Option pricing when underlying stock returns are discontinuous. J Financ Econ (1976). 3:125–44. doi:10.1016/0304-405x(76)90022-2.

11. Pflug, GC. Some remarks on the value-at-risk and the conditional value-at-risk In: Uryasev SP, editor Probabilistic constrained optimization. Nonconvex optimization and its applications. Vol. 49. New York, NY: Springer (2000). p 272–81.

12. Rachev, S, Klebanov, L, Stoyanov, S, and Fabozzi, F. The method of distances in the theory of probability and statistics. New York, NY: Springer (2013). 616 p.

13. Runggaldier, W. Jump diffusion models In: Rachev S, editor Handbook of heavy tailed distributions in finance. North-Holland, Netherlands: Elsevier (2003). p 169–209.

14. Shirvani, A, Stoyanov, SV, Rachev, ST, and Fabozzi, FJ. A new set of financial instruments. (2019). Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3486655.

15. Shirvani, A, Stoyanov, SV, Rachev, ST, and Fabozzi, FJ. A new set of financial instruments. Preprint repository name [Preprint] (2019). Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1612.00828

Keywords: option pricing, hedging, Merton’s jump diffusion model, stochastic volatility model, tail-loss ratio risk measure

Citation: Shirvani A, Stoyanov SV, Rachev ST and Fabozzi FJ (2020) A New Set of Financial Instruments. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 6:606812. doi: 10.3389/fams.2020.606812

Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020;

Published: 26 November 2020.

Edited by:

Young Shin Aaron Kim, Stony Brook University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Shirvani, Stoyanov, Rachev and Fabozzi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abootaleb Shirvani, YWJvb3RhbGViLnNoaXJ2YW5pQHR0dS5lZHU=

Abootaleb Shirvani

Abootaleb Shirvani Stoyan V. Stoyanov2

Stoyan V. Stoyanov2 Svetlozar T. Rachev

Svetlozar T. Rachev