94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Appl. Math. Stat., 29 May 2017

Sec. Dynamical Systems

Volume 3 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fams.2017.00007

This article is part of the Research TopicFrontiers in Dynamical Systems: Invited ContributionsView all 5 articles

In this paper we present an overview of the results concerning dynamics of a piecewise linear bimodal map. The organizing principles of the bifurcation structures in both regular and chaotic domains of the parameter space of the map are discussed. In addition to the previously reported structures, a family of regions closely related to the so-called U-sequence is described. The boundaries of distinct regions belonging to these structures are obtained analytically using the skew tent map and the map replacement technique.

Various bifurcation scenarios have always been in focus of many researchers from different theoretical and applied fields. It is know that bifurcation sequences often differ for piecewise smooth (PWS) systems with respect to smooth ones (see, e.g., [1]). In particular, this happens due to border collision bifurcations (BCB). This specific notion was initially introduced Nusse and Yorke in [2], but similar phenomena were also investigated earlier in Leonov [3] and Feigin [4] (see also [5, 6] and references therein). Recall that due to a BCB an attracting fixed point may be translated to an attracting cycle of any period or even to cyclic chaotic intervals. The simplest example of such behavior is the skew tent map, whose bifurcation scenarios are completely described due to intensive studies [7–10]. Therefore, the skew tent map is often used as a BCB normal form when studying a generic 1D continuous PWS map [5, 11–13]. Another peculiar situation for PWS maps can happen when an eigenvalue (or a conjugate pair of complex eigenvalues) of a cycle crosses the unit circle. Because of certain degeneracy of the map at the bifurcation value, the standard theorems for flip, fold, or Neimark-Sacker bifurcations cannot be applied, and moreover, the result of such a crossing can be atypical. For example, an eigenvalue of a fixed point becomes −1, but after the bifurcation one observes not a 2-cycle, but a chaotic attractor [14]. Further, the bifurcation structure of the skew tent map also illustrates such a phenomenon as robustness of chaotic attractors [15]. That is, in the parameter space there exist connected domains that are characterized by chaotic attractors, that never happens in smooth maps.

In the present paper we continue studying the bifurcation structure of the parameter space of a generic 1D continuous piecewise linear bimodal map f. In our previous works basic families of regions related to regular and chaotic dynamics were investigated. In Panchuk et al. [16] we disclosed three basic bifurcation structures related to attracting cycles: the skew tent map (STM) structure, the period adding (PA) structure, and the fin structure. The STM structure concerns cycles whose points are located on the two adjacent branches only (the left and the middle or the middle and the right). The PA structure is composed by regions associated with cycles placed on the two outermost branches (the left and the right). The fin structure is related to periodicity regions having one common boundary with a PA-region.

In Panchuk et al. [17] we described certain parameter regions corresponding to chaotic attractors (chaoticity regions) and related bifurcation structures. These chaoticity regions neighbor PA and fin regions, and their boundaries are given by homoclinic bifurcations of repelling cycles. In general, if a cycle has negative multiplier, then a merging bifurcation occurs, and the number of pieces of a chaotic attractor is halved. If a cycle has positive multiplier, an expansion bifurcation occurs, and one observes an abrupt increase in size of the attractor with uneven density of points after the bifurcation. For more details see, e.g., [18].

In the current paper we summarize the results of previous works and describe new family of periodicity regions observed in the parameter space of the bimodal map. They emerge from the border that separates the parameter region D1/D2 where asymptotic dynamics is associated with two adjacent branches (STM structure) from the region D0 where all three branches can be involved. For parameters belonging to D1/D2 symbolic sequences of the cycles form the so-called U-sequence (see, e.g., [19, 20]), among which only basic cycles can be stable while all others are unstable. For parameters in D0 every cycle with symbolic sequence belonging to U-sequence has a new complementary cycle (whose symbolic sequence differs by one symbol) having a single point on the third branch. If the slope of the third branch is small enough, this new cycle is stable. We refer to this situation as the “stabilization” of a U-sequence cycle.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we introduce the main definitions and notations used throughout the paper. In Section 3 we recall how the STM structure is formed. Section 4 is devoted to PA and fin regions related to attracting cycles. In Section 5 we explain the phenomena that occur when the invariant absorbing interval involving only one border point collides with the second border point and expands over the third branch. In Section 6 the chaoticity regions surrounding the PA and the fin structures are studied. Section 7 concludes.

All results described are obtained in form of explicit analytic expressions, which can be used for various applied problems. For such a practical usage see, for instance, [21, 22].

Let us consider a family of 1D continuous piecewise linear maps f : ℝ → ℝ such that

Here the slopes , , , the offsets , , , and the border points are real parameters, and we suppose that . By using the conditions (2) any two of eight parameters can be eliminated, but for the sake of generality, we keep all of them.

In Panchuk et al. [16, 17] the regular and chaotic dynamics of map (1) is studied in the cases (i) and (ii) , . In the present work we consider the case , .

Let us first introduce the notations used throughout the paper.

• We denote by p a point in the parameter space of the map f.

• The values of f at the border points, and , are called (following the tradition of French school on Iteration Theory [23]) critical points. Successive images of ℓ and r are denoted as and , i ⩾ 1.

• The term partition refers to the intervals , , and . With each partition we associate the corresponding symbol, , , and , respectively. That is, every point x ∈ Is is coupled with the symbol s, where .

• A cycle of f is associated with the symbolic sequence σ = s0 … si … sn−1, |σ| = n, . The cycle is denoted by .

• Consider a cycle . Clearly, any cyclic shift of σ: σi = si … sn−1s0 … si−1 corresponds to the same cycle . Resting on the sequence σi one can construct a function composition . Then every point xi satisfies fσi(xi) = xi: = xσi. For instance, the points of the 3-cycle {x0, x1, x2} with , , can be written as , , . Clearly, in the main notation for the cycle any σi can be used, and we choose either the shortest one or the most suitable for a particular purpose.

• νσ denotes the multiplier of , given by .

• The periodicity region associated with the stable cycle is denoted by .

• Besides fixed points and cycles the map (1) can also have attracting n-cyclic chaotic intervals denoted as . Hereby every Ji is a closed interval such that (i) fn is chaotic on Ji, and (ii) f(Ji) = Ji+1, , f(Jn−1) = J0. For convenience, J0 refers to the leftmost interval.

• The symbol denotes a region in the parameter space related to . We also refer to as a chaoticity region.

The regions and are confined by boundaries related to certain bifurcations. The boundaries of periodicity regions are usually associated with one of the following bifurcations: a border collision bifurcation (BCB) occurring when a point of a cycle collides with one of the border points; a degenerate flip bifurcation (DFB) which occurs when the multiplier of a cycle equals minus one; a degenerate +1 bifurcation (DB1) associated with the multiplier being equal plus one. For details on these bifurcations we refer to Sushko and Gardini [14], Nusse and Yorke [2], Banerjee et al. [5], and Zhusubaliyev and Mosekilde [6].

The boundaries of chaoticity regions are often related, besides BCBs and DFBs, to homoclinic bifurcations of a repelling cycle located at the immediate basin boundary of the attractor. For instance, a merging bifurcation or an expansion bifurcation leads to changing the number of intervals of a chaotic attractor. Whereas a final bifurcation (known also as a boundary crisis) implies a transformation from a chaotic attractor to a chaotic repeller (see, e.g., [18]). A homoclinic bifurcation is always associated with an unstable cycle and is defined by the condition cj = xσi, where xσi is the appropriate point of and , c ∈ {ℓ, r}, is the critical point of the proper rank j ⩾ 0.

For the bifurcation boundaries of periodicity and chaoticity regions we use the following notations:

• denotes a BCB of the cycle , which occurs when xσi = d with .

• ησ and θσ are used for a DFB and a DB1 boundaries, respectively, associated with νσ = −1 and νσ = +1.

• , and refer to homoclinic bifurcations: a merging bifurcation, an expansion bifurcation, and a final bifurcation, respectively.

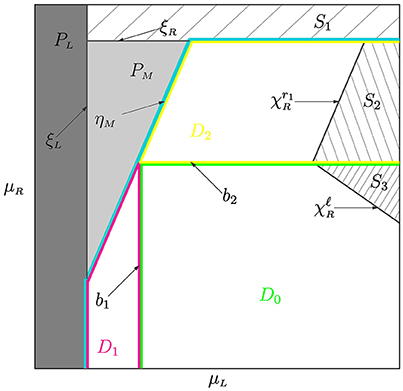

At first we describe the regions characterized by simple dynamics, that is, either an attracting fixed point or divergence to infinity. Then a brief description of regions related to more complex behavior follows (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The parameter plane of the map f for and . The regions , are related to stable fixed points. The regions S1, S2, S3 are related to diverging orbits. The regions D1, D2, and D0 are associated with asymptotic orbits located in , , and , respectively.

The function f can have at most three fixed points1, one in each partition Is, . A fixed point , , given by xs = μs/(1 − as) appears/disappears through collision with the border point ds. The related bifurcation boundary is

Notice that the upper index ds is omitted in the notation ξs because it is clear that at the collision occurs with while at it occurs with . Below, for shortness, we drop upper indices in notations for BCB boundaries whenever it is clear which border point is involved in the bifurcation (namely, when the first symbol of σ is or the related border point is or , respectively).

From 0 ⩽ as < 1 the stability regions of and are obtained:

The stability region is separated from the divergence region by the boundary as = 1, where

(see Figure 1 where and are shown).

The region

associated with the attracting fixed point given by , is confined by three boundaries. Namely, the BCB boundary , the BCB boundary , and the DFB boundary

related to the condition .

The rest of parameter space is occupied by the region

which is marked by blue line in Figure 1. First, we notice that for certain parameter values asymptotic orbits of f are located only on the two adjacent branches. Namely,

1. If then only and are relevant for asymptotic dynamics of f. Hence, the surfaces , , and b1 (defined from the condition ) confine the region

(outlined red in Figure 1). The related bifurcation structure—skew tent map (STM for short) structure—is described in Section 3.

2. Similarly, the condition holds in the region

(outlined yellow in Figure 1). This region, also having the STM structure, is confined by , , and the boundary b2 corresponding to the condition . For p ∈ D2 only and are relevant for asymptotic dynamics of f (see Section 3).

Finally, the conditions and define the region

delineated green in Figure 1). For parameter values belonging to D0, orbits of f are located on either and , or involve all three partitions. Two basic bifurcation structures observed in the region D0 are period adding (PA for short) structure and fin structure, described in Section 4.

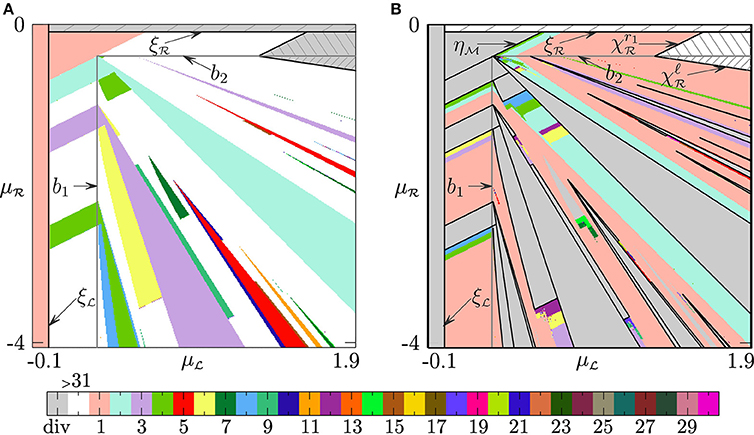

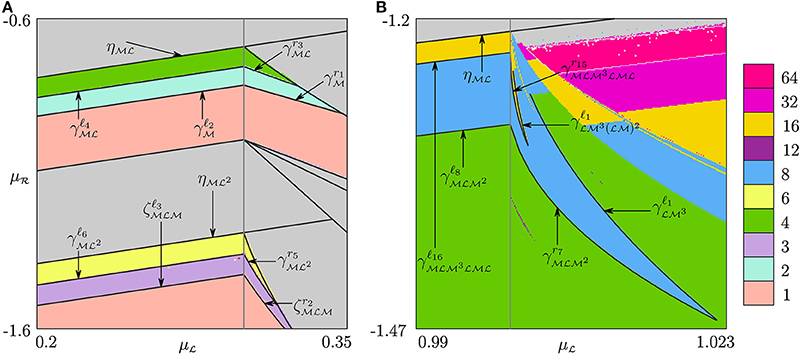

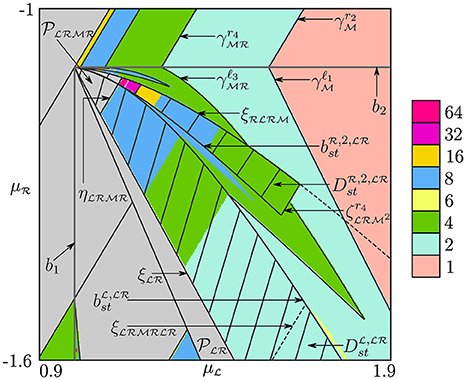

Figure 2A presents an example of the typical bifurcation structure related to regular dynamics in the parameter plane of the map f (the colors correspond to periods of cycles as indicated in the color bar). In Figure 2B, on the contrary, colored zones correspond to chaoticity regions related to chaotic attractors with different number of intervals (colors correspond to the number of intervals), while periodicity regions are painted gray.

Figure 2. Bifurcation structure of the -parameter plane of f. (A) Regular dynamics: colors correspond to periods of related cycles, while gray hatched areas are associated with diverging orbits. (B) Chaotic dynamics: periodicity regions are shown in gray, while chaoticity regions related to chaotic attractors with different number of intervals are shown with different colors. Parameters: .

In the following sections we characterize different bifurcation structures observed in the parameter space of the map (1).

Let p ∈ D1 or p ∈ D2, then asymptotic dynamics of the map (1) is associated with two adjacent partitions only. In such a case the map f is locally topologically conjugate to the famous skew tent map, which was extensively studied already three decades ago (see e.g., [7–10]). Below we summarize main facts concerning this bifurcation structure, which we refer to as the skew tent map (STM) structure.

Let us consider the skew tent map family gα,β,μ

with αβ < 0. All maps from this family with μ > 0 (μ < 0) are topologically equivalent to gα,β,1 (gα,β,−1). Moreover, gα,β,−1 is topologically equivalent to gβ,α,1. Hence, to describe the STM structure it is enough to fix μ = 1. Non-trivial dynamics in this case is observed for α > 0, β < 0. Below, for shortness, we drop the indices denoting the parameters and refer to the skew tent map simply as g.

Any point x < 0 is associated with the symbol , while a point x > 0 corresponds to the symbol . The critical point is denoted as c := g(0) and its images as .

The stability region of the fixed point is confined by the DB1 boundary and the DFB boundary .

The only possible stable cycles of g are the basic n-cycles , n ⩾ 2. Each periodicity region is confined by the BCB boundary and the DFB boundary

(see Figure 3 where the boundaries and are marked). The BCB boundary is particular, because it coincides with the DFB boundary . For every n ⩾ 3 the boundary corresponds to the fold BCB leading to the appearance of the basic cycle and its complementary cycle which is necessarily unstable. The boundary , n ⩾ 3, is related to the DFB of the cycle , which leads to the appearance of 2n-cyclic chaotic intervals . The DFB of the fixed point and the 2-cycle are particular as described below.

The chaoticity region , n ⩾ 3, associated with , is the area restricted between , , and . The latter one is related to the first homoclinic bifurcation of the cycle . This bifurcation occurs when

The condition (14) holds for

Crossing the bifurcation boundary leads to the transition , which is also called the merging bifurcation. The existence region for n-cyclic chaotic intervals is confined by , boundary , and the boundary corresponding to the first homoclinic bifurcation of the cycle . This homoclinic bifurcation occurs when

which gives

Crossing the boundary leads to the transition , which is also called the expansion bifurcation. For more detailed description of merging and expansion bifurcations we refer to Avrutin et al. [18]. In Figure 3 the boundaries and are marked.

Cases n = 1 and n = 2 differ from the others. The DFB of the fixed point leads either to an attracting 2-cycle or to 2m-cyclic chaotic intervals, where m ⩾ 1 depends on particular parameter values. As for the 2-cycle , when it loses stability due to DFB, there can appear 2m-cyclic chaotic intervals , where m ⩾ 2 depends on α, β. Every region is adjacent to from one side and to from the other side. The boundary separating and is associated with the first homoclinic bifurcation of the 2m-cycle whose symbolic sequence is the m-th harmonic of . Recall that to obtain the k-harmonic ρk of one has to apply concatenation operator iteratively as follows:

where differs from ρk−1 only by the last symbol. For example, , , , and so on. Notice that according to the rule (18) it is possible to define harmonics of an arbitrary cycle provided that xσ is the rightmost point of the cycle. For instance, in the condition (14) for the first homoclinic bifurcation of the symbolic sequence is the first harmonic of .

The condition for the first homoclinic bifurcation of the 2m-cycle is

that holds for

where , m ⩾ 1. As mentioned above this bifurcation leads to the transition , The case m = 0 (i.e., the merging bifurcation ) is related to the first homoclinic bifurcation of the fixed point leading to the transition . For m → ∞ the curves in the (α, β)-plane crowd the point (α, β) = (1, −1) (see Figure 3).

The region related to diverging orbits (hatched in Figure 3) is confined by the boundary related to the first homoclinic bifurcation of the fixed point , which occurs when :

At this bifurcation the absorbing interval J = [c1, c] collides with a boundary of its basin of attraction (given by and its preimage) and for the interval J is no longer absorbing causing a typical orbit to diverge. Such bifurcation is also called a final bifurcation.

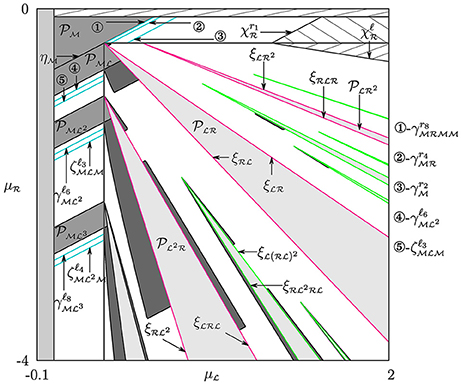

For p ∈ D1 or p ∈ D2 the original map f is locally topologically conjugate to g with , or , respectively, and μ = 1 in the neighborhood of or , respectively. Thus, to get the boundaries of STM-regions in the parameter space of f it is enough to substitute or , respectively, instead of and instead of . In Figure 4 the STM-regions in the parameter plane associated with attracting cycles are colored with moderate gray, while for chaoticity regions only their boundaries are shown (blue lines). The hatched region in D2 is related to diverging orbits.

Figure 4. Bifurcation structure of the -parameter plane of map f: periodicity regions of the STM structure, as well as the PA and the fin structures are shown moderate gray, light-gray, and dark-gray, respectively. For chaoticity regions of the STM structure their boundaries are shown with blue lines. For PA regions of the first complexity level their boundaries are plotted red, while green color corresponds to the second complexity level. The parameters are as in Figure 2.

Let us briefly recall how other two periodicity structures are formed in the parameter space of f for p ∈ D0.

Consider a cycle of the map f with , such that all its points belong only to . Consequently, σ consists only of the symbols and . Then the related periodicity region is a part of the so-called period adding structure (PA structure). Such structures are also known as Arnold tongues or mode-locking tongues and often appear in the parameter space of a certain class of circle maps, 1D discontinuous maps, two- and higher-dimensional maps near a Neimark-Sacker bifurcation boundary, etc. (see, for example [3, 24–27]). We recall that the regions belonging to PA structure are located in the parameter space according to a specific order based on Farey summation rule. Namely, consider two cycles of period n1 and of period n2 with σi containing mi symbols . Suppose also that the fractions m1/n1 and m2/n2, called also rotation numbers, are Farey neighbors, that is, |m1n2 − m2n1| = 1. Then in the parameter space between the two regions related to and there is a region related to a cycle of periodicity n1 + n2 with σ3 having m1 + m2 symbols , and thus, the rotation number of is (m1 + m2)/(n1 + n2). Notice that the cycles , i = 1, 2, 3, are not necessarily attracting.

In Figure 4 the regions composing the PA structure are shown light-gray.

If then any PA-cycle is globally attracting inside the region of its existence. Indeed, in this case for p ∈ D0 there always exists an invariant absorbing interval J = [r, ℓ], and hence, there are no divergent orbits. Moreover, we consider an arbitrary PA-cycle and immediately get that its multiplier is , where m is the number of 's in σ.

However, if one of the slopes is greater than one, while the other is between zero and one, the inequality νσ < 1 is satisfied only if , so that not all PA-cycles are attracting. There can also be divergent orbits since there is an unstable fixed point on the branch whose slope is greater than one. Furthermore, the interval J is no longer absorbing after the final bifurcation corresponding to the first homoclinic bifurcation of this unstable fixed point. The related bifurcation boundary confines the region in the parameter space in which a typical orbit diverges. For instance, for , (as in Figure 4) the final bifurcation occurs when , and thus, for any all orbits go to infinity.

To simplify calculation of analytic expressions for PA-region boundaries we use the so-called map replacement technique [28]. At first we group symbolic sequences of PA-cycles into infinite number of families complying with their complexity level (as in [3]). For example, two families related to basic cycles form the first complexity level:

Notice that both families contain the common sequence .

To construct the rest of symbolic sequence families we introduce the following symbolic replacements:

Application of a symbolic replacement to a symbolic sequence σ means that each symbol in σ is replaced by and each symbol by . Similarly, application of means replacing all 's by and all 's by .

Symbolic sequences of higher complexity levels are obtained by iterative application of and . More precisely, applying and to Σ1,1 we get the families

And then applying and to Σ2,1 we obtain

The four families Σi,2, , compose the second complexity level. Notice that the families Σ1,2 and Σ3,2 contain the common sequence with n1 = n2 = 1, while Σ2,2 and Σ4,2 share the sequence with n1 = n2 = 1.

In short the applied procedure can be written as

Further, applying the replacements (23) with m = n3 to four families of the second complexity level, we obtain 23 families Σj,3, , of the third complexity level, and so on. In this way all symbolic sequences of PA-cycles are obtained.

Now let us identify the PA-regions in the parameter space of the map f. Each such region has two boundaries corresponding to BCBs of the related cycle. For the basic cycles , n1 ⩾ 1, these boundaries are obtained directly from the relevant BCB conditions giving

where

with

For , n ⩾ 1, their boundaries are obtained from (27) by interchanging and . So that, the basic PA-regions are defined as

Further, using the map replacement technique we obtain periodicity regions associated with cycles whose symbolic sequences belong to the families Σ1,2 and Σ2,2, given in (24). The trick is as follows. Any symbolic sequence τ ∈ Σ1,2 can be written as with certain n2 ⩾ 1 and σ ∈ Σ1,1 with particular n1 ⩾ 1. Then to get the BCBs and we take the expressions (27) for and and substitute the parameters , , , by , , , :

Recall that , and , denote, respectively, the coefficients of the following composite (auxiliary) functions

Schematically, we summarize the applied procedure as follows:

Clearly, the coefficients , , , depend on , , , , and hence, the equalities in (33) can be solved with respect to , implying the PA-region related to to be

where Ψ1,2, Φ1,2 are certain functions (see [16] where expressions for Ψ1,2, Φ1,2 are given in explicit form).

Similarly, any symbolic sequence τ ∈ Σ2,2 can be written as with n2 ⩾ 1 and σ ∈ Σ1,1. To get the expressions for the boundaries of we perform analogous trick replacing in (27) the parameters , , , with the coefficients , , , of the related (auxiliary) composite functions. The resulting new equalities can be resolved with respect to , and the related PA-region is

with certain Ψ2,2, Φ2,2.

As for the cycles whose symbolic sequences belong to the families Σ3,2 and Σ4,2 (25), boundaries of the related periodicity regions are obtained by interchanging the indices and and changing the inequality signs to the opposite ones in (36) and (35), respectively.

Similarly, having expressions for the boundaries of periodicity regions of the (k − 1)-th complexity level and using this replacement technique, we can compute the related expressions for periodicity regions of the k-th complexity level (for more detail see [16]).

In Figure 4 for the regions of the first complexity level their boundaries are colored red, while for those of the second complexity level they are green.

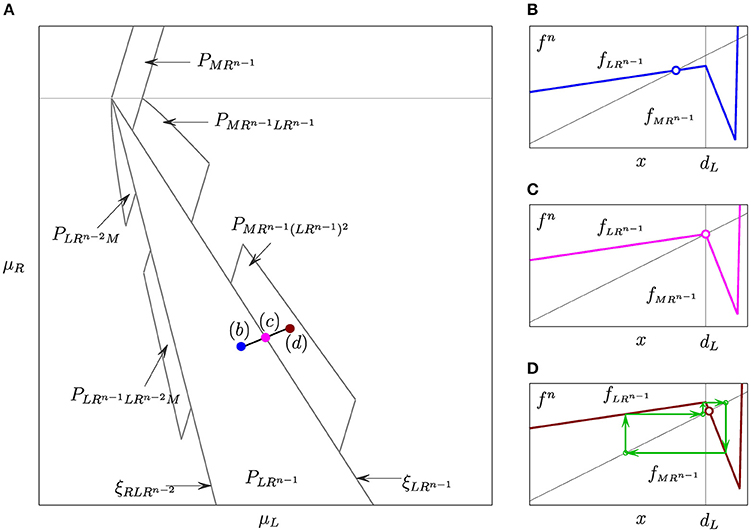

In Figure 2 or in Figure 4 one can notice that some PA-regions have other (smaller) periodicity regions attached to them, which resemble to certain extent fish fins. Every such fin-like region is associated with a stable kn-cycle, where n is the period of the related PA-cycle and k ⩾ 1. To explain briefly how these regions appear, let us consider the n-th iterate of f.

For the map fn every point of the PA-cycle, say , of the period n is a fixed point. Suppose that the parameter point moves outside the region crossing transversally, for instance, the boundary (see Figure 5). Near the BCB the map fn is locally topologically conjugate in the neighborhood of to a skew tent map gα,β,μ (12) with , (l is the number of symbols in σ) and μ < 0 before, μ = 0 at, and μ > 0 after the bifurcation. In other words, the skew tent map is used as the BCB normal form, and the result of such a bifurcation is completely defined by the values of α and β (see, e.g., [5, 10, 11]). In particular, for certain combination of , and , a stable k-cycle for fn appears after the BCB. In terms of the original map f, after the BCB of a stable n-cycle there occurs a stable kn-cycle, say, . Crossing the boundary is treated likewise with the only difference that (for details see [16]).

Figure 5. (A) The left and the right 1 · n-, 2 · n-, and 3 · n-fins of the PA-region shown schematically in the -parameter plane. (B–D) Plots of fn at the corresponding parameter points marked in (A).

We refer to / as the k · n-fin cycle/region, and to / as the trunk cycle/region. For clarity sake, the region is called the left/right k · n-fin if it is attached to the boundary of that is related to collision of with the left/right border point /. Furthermore, the complexity level of the trunk region defines the complexity level of its fins.

Let us consider , n ⩾ 2, of the first complexity level. Its left k · n-fin regions, k ⩾ 1, correspond to cycles whose symbolic sequences are

while symbolic sequences of the cycles associated with right k · n-fin regions are

As for the trunk region its k · n-fins correspond to cycles whose symbolic sequences are obtained from (37) and (38) by interchanging symbols and . Whether a trunk region has fins on both sides or none of them is present depends on the parameters.

Every fin region , , k ⩾ 2, obviously has a common BCB boundary with the related trunk region. At most has three more bifurcation boundaries that correspond to two other BCB's and the DFB of the associated cycle. Analytic expressions for the BCB boundaries are obtained by using the skew tent map as border collision normal form. The DFB boundary is given by condition , where l is the number of symbols in . For left fins the expressions are (see [16])

where Φ1,1 is introduced in (28). Notice that the symbolic sequence of the 1 · n-fin cycle is , and hence, the related periodicity region is confined by only three boundaries: (39), (40), and (42).

Similarly, the bifurcation boundaries confining the right k · n-fin , contiguous to , are

where Ψ1,1 is given in (29). Again the symbolic sequence of the 1 · n-fin cycle is , and consequently, the periodicity region is confined by (39), (40), and (42).

In Figure 5 the region and its fins are shown schematically.

The boundaries of fins contiguous to trunk regions can be obtained by interchanging the indices and in (39–45). The expressions for the boundaries of fin regions attached to trunk regions of higher complexity levels can be obtained using the map replacement technique mentioned in Section 4.1 (see [16] for details).

The present section describes the phenomena that occur when the parameter point p crosses the boundary b1/b2 entering D0. As mentioned above, for p ∈ D1/D2 the invariant absorbing interval J (if it exists) involves only one border point / and is located in two partitions only. At the boundary b1/b2 the interval J collides with the second border point and expands into the third partition. This implies modification of bifurcation boundaries confining periodicity and chaoticity regions.

Recall that for p ∈ D1 asymptotic orbits of the map f are located in only. If additionally either , or and , then there exists invariant absorbing interval . Consequently, all bifurcation boundaries in D1 engage only the left border point and the critical point ℓ (including its images). Similarly, for p ∈ D2 the bifurcation conditions are related to the right border point and the critical point r only. Conversely, for p ∈ D0 the absorbing interval J (if existent) extends over all three partitions. Hence, a bifurcation may be associated with any border or critical point.

Let us consider first chaoticity regions , existing after the DFB of the attracting cycle , n ⩾ 3 (generic case). We describe how their boundaries change when the parameter point p enters D0 crossing the border b1 (see, for instance, the regions and shown Figure 6A). As described in Section 3, for p ∈ D1 the DFB of leads to appearance of 2n-cyclic chaotic intervals , and thus, the corresponding region is confined by and . However, the part of located in D0 is confined by the other two boundaries. The first one is the fold BCB boundary , associated with the collision of the fin cycle with . The second boundary is an extension of to D0, which we refer to as its D0-prolongation. This boundary is associated as well with a homoclinic bifurcation of , but its condition differs from the one for , as we show below.

Figure 6. Bifurcation structures associated with D0-prolongations of the boundaries of the chaoticity regions belonging to the STM structure in D1. Parameters: (A) , , , . (B) , , , .

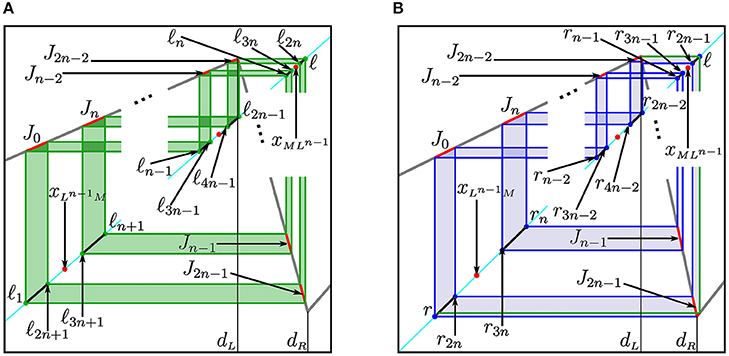

Figure 7A is a schematic representation of 2n-cyclic chaotic intervals for . It can be shown that the intervals Ji, , are bounded by ℓi+1 and ℓi+2n+1 and the interval J2n − 1 by ℓ2n and ℓ. Hence, for p ∈ D1 the homoclinic bifurcation corresponding to the merging can be defined by the following condition:

(cf. (14)). For p ∈ b1, the condition holds, and hence ℓ1 = r, ℓi+1 = ri, i ⩾ 1. Therefore, the intervals Ji, , constituting are bounded by ℓi+1 = ri and ℓi+2n+1 = ri+2n, while the interval J2n − 1 is given by . Hence, the condition (47) becomes

Figure 7. Schematic representation of function f and 2n-cyclic chaotic intervals before the merging bifurcation of for (A) p ∈ D1; (B) p ∈ D0.

As soon as the point p enters the region D0 by crossing b1, the absorbing interval J spreads over all three partitions , , and . For it means that with (see Figure 7B). By definition f(J2n − 1) = J0. If p is close to b1, the value of ℓ is greater than the value of , but it is still close to , and thus,

It entails that , while ℓ1 ∈ J0. As a result, only the right boundary of J2n − 1 is given by ℓ, and its left boundary, as well as the boundaries of the intervals Ji, , are given by the images of r (of the same rank as for p ∈ b1). Thus, for p ∈ D0 the condition for the homoclinic bifurcation leading to the transition coincides with (48). In such a way the D0-prolongation of is the merging bifurcation boundary

Similarly, we deduce that the chaoticity region consists of two parts, one of which is located in D1 and the other one in D0 (see Figure 6A for a sample of ). The part of located in D1 is confined by the merging bifurcation boundary and the expansion bifurcation boundary . The part of located in D0 is bounded by , (49) and the D0-prolongation of , which is associated with the expansion bifurcation as well and leads to the transition . To obtain the condition related to the mentioned D0-prolongation we recall that for p ∈ b1 there holds . There follows that

Hence, for p ∈ D0 the expansion occurs at

Now we turn to chaotic attractors existing after the DFB of or . Although these cases are particular they are treated likewise. The DFB of a stable 2-cycle or a fixed point implies appearance of intervals where m ⩾ 1 depends on parameters. Then there exists a cascade of merging bifurcations ending by the parameter region for that the whole absorbing interval represents a one-piece chaotic attractor. Each boundary for p ∈ D1 has its D0-prolongation

related to the transition . Here ρm is the m-th harmonic of (cf. (18) with and ), and such that is (m + 1)-th harmonic of .

In Figure 6B we observe the D0-prolongations and , while and are visible in Figure 6A.

To summarize, we state

Proposition 1 ([17]). Consider a merging bifurcation boundary related to the transition , where |σ| = n, n ⩾ 1, xσ is the rightmost point of the cycle . Then the D0-prolongation of is given by the homoclinic bifurcation condition fω(r) = xσ where ω is obtained from the first harmonic of σ by dropping the first symbol .

An expansion bifurcation boundary , n ⩾ 3, and its D0-prolongation are related in a similar way.

Further, let us consider an arbitrary chaoticity region , m ⩾ 2, which extends from D1 to D0. As it was shown above, when p ∈ D1 the boundaries of intervals Ji, , constituting the chaotic attractor are defined by the images of ℓ only (see Figure 7A). When p ∈ D0 but still close to b1, the rightmost interval is given by . The intervals Ji, , are confined by the images of r, in particular, . Moreover, , and therefore ℓ1 ∈ J0 (see Figure 7B). Then, if p moves away from b1, the values ℓ and ℓ1 increase, and eventually . Consequently, when p moves further away from b1 the leftmost interval of becomes J0 = [r, ℓ1].

Hence, additionally to (which is related to r) another homoclinic bifurcation of the 2m-cycle related to ℓ may occur. This homoclinic bifurcation defines an additional boundary of and occurs when the leftmost point of coincides with ℓ1, that is, at the boundary

where with (thus, is the leftmost point of ). In Figure 6B the boundaries and are shown.

We remark that the homoclinic bifurcation of type (52) can happen only if the corresponding cycle has at least one point in . This is not true for the fixed point , and thus, the region does not have this additional bifurcation boundary.

In such a way we can formulate

Proposition 2 ([17]). Suppose that for p ∈ D0 (in a certain neighborhood of b1) there exists a D0-prolongation of , m ⩾ 1, associated with the transition . Then there exists a neighborhood such that for there exists a boundary , where is such that is the leftmost point of the cycle . The boundary is associated with the same transition and related to a homoclinic bifurcation of the cycle colliding with an image of the critical point ℓ.

As for chaoticity regions located in D2, to derive expressions for their D0-prolongations it is enough to swap 's and 's, as well as change r to ℓ in (49–51). Similarly, for p ∈ D0 in a certain neighborhood of b2, a chaoticity region , m ⩾ 1, has an additional boundary related to a homoclinic bifurcation, whose expression can be derived from (52) by swapping 's and 's and replacing ℓ1 by r1.

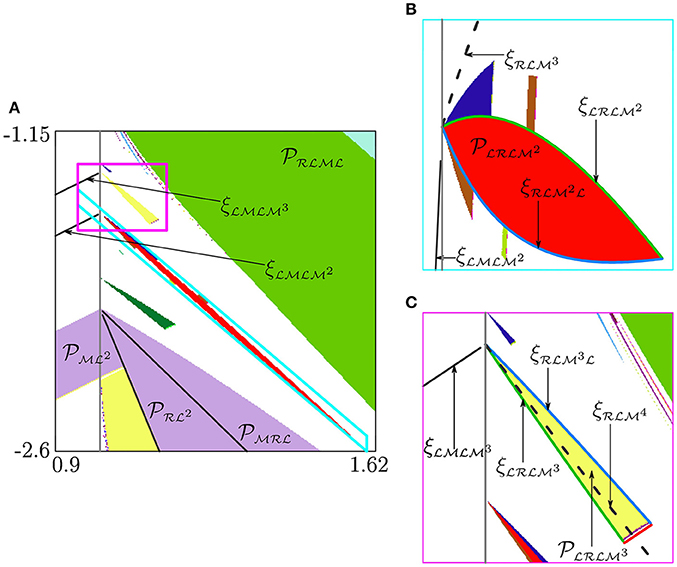

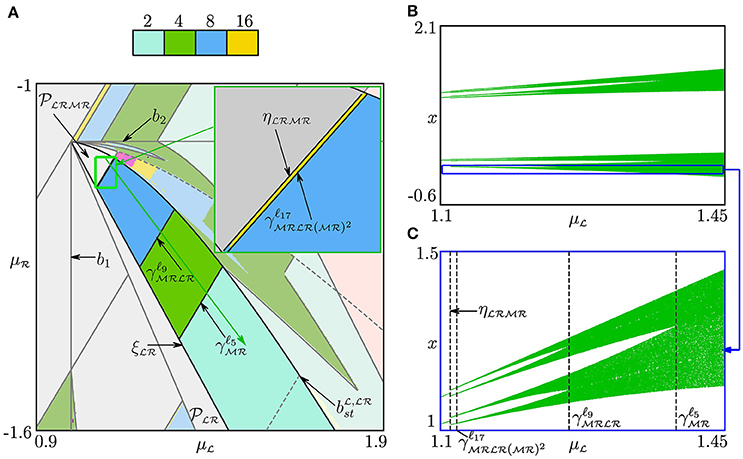

In the previous section we described how the boundaries of chaoticity regions forming the STM structure change when the parameter point p enters D0 by crossing b1 or b2. Every merging or expansion bifurcation boundary existent in D1/D2 has its D0-prolongation. So does every region related to cyclic chaotic intervals. However, the dynamics of the map f for the parameter values p ∈ D0 in the neighborhood of b1/b2 is not limited to D0-prolongations of the STM regions. For instance, in Figure 8 between the right 2 · 2-fin of and the left 1 · 3-fin of one observes several tongues related to n-cycles with small values of n, e.g., with n = 5, 6, 7, 10. At the first site the origin of these tongues is unclear. In this section we explain the reason why such regions appear in the neighborhood of b1. All stated below can be generalized in the obvious way for b2.

Figure 8. Stabilization of U-sequence cycles. Panels (B,C) are the enlargements of the areas marked in (A) by blue and magenta lines, respectively. The parameters are , , , .

To discover the origin of the tongues that are not D0-prolongations of the STM structure, recall that for the skew tent map (12) even if the dynamics converges to a chaotic attractor, there exist also many periodic solutions that are unstable. These cycles appear due to BCBs or DFBs and according to a certain universal order with decreasing β. Namely, the symbolic sequences of these cycles form the so-called U-sequence where “U” stands for “universal,” since this order is common for a wide class of unimodal maps [19, 20]. Notice that usually U-sequence is described in terms of kneading sequences associated with superstable cycles (in the symbolic representation of which the symbol C related to the extremum of the function is omitted). The skew tent map obviously cannot have superstable cycles, and by using the term “U-sequence” we mean the order of appearance of the cycles in terms of their complete symbolic representation.

Another peculiarity of the skew tent map is that some blocks of the U-sequence appear simultaneously. For instance, crossing the DFB boundary (or when α > 1) with decreasing β leads to immediate appearance of cycles with symbolic sequences being harmonics of , defined in (18). Similar statement is true for a basic cycle , n ⩾ 3, that is, all its harmonics appear at the same parameter values (at the boundary ).

In general, the U-sequence is constructed according to a certain iterative procedure and includes also the basic cycles. Detailed description of this construction procedure, as well as explanation of its peculiarities related to the skew tent map, is beyond the scopes of the current paper. Here we only explain how an unstable cycle whose symbolic sequence belongs to U-sequence may be “stabilized” when p enters D0 crossing b1 or b2. For shortness we refer below to such cycles as U-sequence cycles.

Consider, for example, the region related to the 5-cycle observed in Figure 8A (see also the enlargement in Figure 8B). For p ∈ D1 the line denotes the fold BCB, at which two unstable 5-cycles are born: the cycle and its complementary cycle . The condition related to this bifurcation is

In fact, (53) defines two different BCB conditions which are equivalent due to the continuity of f, that is, . This explains why the two cycles (which coincide at the bifurcation moment) appear simultaneously and why their symbolic sequences after the bifurcation differ by a single symbol.

For the condition (53) can be rewritten taking into account that :

since . Applying f one more time to (54), and using again the continuity property of f, we get

Similarly to (53), the equalities (55) define four BCB conditions that, nevertheless, are equivalent for . Notice that in (55) the BCB conditions depend on , in contrast to (53) where they depend on . This is similar to how conditions of homoclinic bifurcations change when the parameter point p moves from D1 to D0 (as described in Section 5).

Now, for p ∈ D0 not all the BCB conditions (55) remain equivalent. Moreover, the two cycles and do not appear simultaneously for p ∈ D0. Instead, each of them creates a complementary pair with one of the two new cycles having a single point in (and, thus, existing only for p ∈ D0). Namely, the cycle is now complementary to , while is complementary to . Clearly, the BCB conditions for the two cycles making a pair are equivalent, that is,

However, the related bifurcation is not necessarily fold BCB.

Let us describe in more detail the BCBs related to four mentioned 5-cycles. With decreasing (for the other parameter values as in Figure 8) they appear in the following order. First, the two unstable cycles and are born due to the fold BCB (dashed curve). Then there occurs the BCB (green curve), at which the point of moves from the middle partition to the left one . Hence, the stable cycle appears. Finally, the point of located in the right partition moves to the middle partition due to the other BCB creating the unstable cycle . The region is then confined by and . For being below the two unstable cycles and continue to exist.

We also remark that the region has fins similarly to PA-regions. The mechanism of their creation is the same. Indeed, at the BCB boundary of related to collision of the cycle with /, the map f5 is locally (in the neighborhood of /) topologically equivalent to the skew tent map gα,β,1 with and /. Crossing transversally this BCB boundary may lead to appearance of a stable 5k-cycle, k ⩾ 1 (cf. Section 4.2). Existence of fins and their number depends on the parameter values.

The scenario due to that the region occurs corresponds to what we call the “stabilization” of a U-sequence cycle. That is, for p ∈ D1 the U-sequence cycle is unstable (except for the basic cycles , n ⩾ 2, which can be stable). When p crosses b1 entering D0 a new cycle (among the others) is born. The symbolic sequence σ′ differs from σ by a single symbol. Namely, the symbol corresponding to the rightmost point of is replaced by in σ′. If the slope is small enough, the cycle is stable.

The region related to a 6-cycle observed as well in Figure 8A has the same origin, though it looks somewhat unlike . Let us consider it in more detail and explain why it has different form. For p ∈ D1 due to the BCB the two unstable 6-cycles and appear. Similarly to the case considered above (of the 5-cycle), for p ∈ D0 there are two more 6-cycles: (stable) and (unstable). However, in contrast to the previous case, the sequence of bifurcations occurring with decreasing is different. First, the fold BCB occurs giving rise to the stable cycle and the unstable one . Next, the two unstable cycles and appear due to the fold BCB . Finally, (stable) and (unstable) disappear at . Notice that the region (differently from ) has one more boundary that corresponds to the DFB of the related cycle.

The other regions emerging from b1 and not belonging to PA or fin structures are of the same nature as the two regions described above. Notice that, for a U-sequence cycle , the higher is its period, the more of its points are located in . Thus, to observe for p ∈ D0 the region corresponding to the “stabilized” version of , the value should be small enough. In the limit case , for every U-sequence cycle there exists the related periodicity region in D0 (see Figure 9), since the multiplier of equals zero. Clearly, all these regions have only BCB boundaries and extend to infinite values of , .

Figure 9. Periodicity regions related to “stabilized” versions of U-sequence cycles in the limit case .

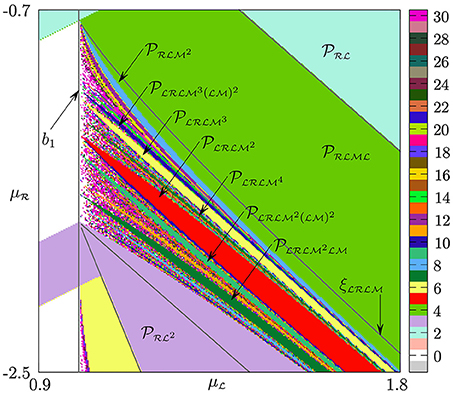

In Section 4.1 we have recalled how to obtain boundaries of PA-regions. There are chaoticity regions adjacent to them, and now we discuss how their boundaries can be derived using the skew tent map. As an example, Figure 10 shows the structure of chaoticity regions close to the BCB boundary of the PA-region . One can observe here two hatched domains. The first one, denoted , is contiguous to the PA-region along the boundary . For the map f2 is locally topologically conjugate to the skew tent map. Hence, the bifurcation structure can be described by applying directly the results known for the skew tent map.

Figure 10. Bifurcation structure related to chaoticity regions associated with the PA-region and its left 2 · 2-fin . The regions and are shown dashed.

In general, in the neighborhood of the boundary / of every PA-region associated with an n-cycle , there exist domains denoted /, respectively, such that for related parameter values the iterate fn is locally (in the neighborhood of /) topologically conjugate to the skew tent map.

The second hatched domain in Figure 10, denoted , is located in the neighborhood of the boundary of the left 2 · 2-fin region . In general, let us consider an arbitrary PA-region , related to the n-cycle , and its left/right k · n-fin . In the neighborhood of the BCB boundary /, respectively, there exists a domain / such that the restriction of fkn to its absorbing interval is topologically conjugate to the skew tent map.

We consider first the trunk region and sub-domain contiguous to it along the boundary . Clearly, both points of the 2-cycle are fixed points for the second iterate f2, and at the point collides with . The resulting dynamics caused by this collision depends on the slopes of f2 at both sides of at the bifurcation moment. In the neighborhood of the border point the map f2 is defined as (see Figure 11)

where , . If the condition

is satisfied, then f2 has a local absorbing interval , on which f2 is topologically conjugate to the skew tent map (12) with and . The parameter region for that the conjugacy takes place is given as

It is located between two boundaries, namely, and

which follows from the equality .

For expressions for all bifurcation boundaries are derived directly from the related expressions known for the skew tent map (cf. Section 3).

Similarly, for an arbitrary PA-region related to an n-cycle , n = |σ|, let , where the symbolic sequences σ1 and σ2 are such that the point / collides with / at the BCB boundary /, respectively. For consider the map fn, for which every point of is a fixed point. Close to the boundary , two branches of fn joining at the border point are

Here and are preimages of , such that and . As before it can be shown that as long as

there exists a local absorbing interval

such that the restriction is topologically conjugate to the skew tent map g with the slopes and . Here and are the slopes of the composite functions and , respectively. Such a conjugacy persists until the parameter point p crosses the border given by the condition , which is equivalent to , i.e.,

Hence, we can state the following

Proposition 3 ([17]). For , where the region

is confined by and given in (62), the expressions for boundaries of periodicity regions (fins) and chaoticity regions can be obtained from the related expressions known for the skew tent map (62) substituting α by and β by .

For instance, we consider the left k · n-fin , , k ⩾ 3, of the PA-region . This fin region represents the area located between three BCB boundaries: , (the point xτi of the cycle collides with ), (the point xτj of the cycle collides with ), and the DFB boundary ητ. We remark that the boundaries and ητ emerge from , as well as the boundaries between chaoticity regions adjacent to .

Analytic expressions for all these boundaries are derived by using the skew tent map. Boundaries of the fin region, and ητ, are given in (41) and (40), respectively. Let us consider the merging and the expansion bifurcation boundaries confining chaoticity regions and . They can be obtained by applying map replacement technique to expressions for (15) and (17).

Namely, in (15) we substitute all symbols with symbolic sequence , all symbols with symbolic sequence , critical point c with , slope α with , and β with . Recall that and are the slopes of the composite functions and , respectively. Expressing and in terms of the original parameters , , we obtain the merging bifurcation boundary related to transition . Likewise, by applying the same replacement to (17) one gets the expansion bifurcation boundary . In short this procedure can be represented by the following scheme:

For sake of shortness schemes of such kind are used below to describe similar replacement procedures.

To sum up we can state

Proposition 4 ([17]). Let the parameter point p move along the BCB boundary starting from nk-fin region , k ⩾ 3. Then p first crosses the DFB boundary (40) leading to 2kn-cyclic chaotic intervals , then the merging bifurcation boundary (64a) implying the transition , and finally, the expansion bifurcation boundary (64b) leading to .

The case k = 2 is particular. Since a 2n-fin cycle corresponds to the 2-cycle of the skew tent map g, its DFB leads to the appearance of 2m·n-cyclic chaotic intervals, where m ⩾ 2 depends on , . The cascade of the subsequent merging bifurcations is obtained from (20) applying the same replacement as in (64). In Figure 12 an example of this cascade observed inside the domain is shown, located close to the left 2 · 2-fin region of the trunk region . One can see three merging bifurcation boundaries, namely, , , and leading to the transitions , respectively. To get the expression for the following replacement

can be used. In this way we obtain

The expressions for the other two boundaries

can be obtained by the same replacement.

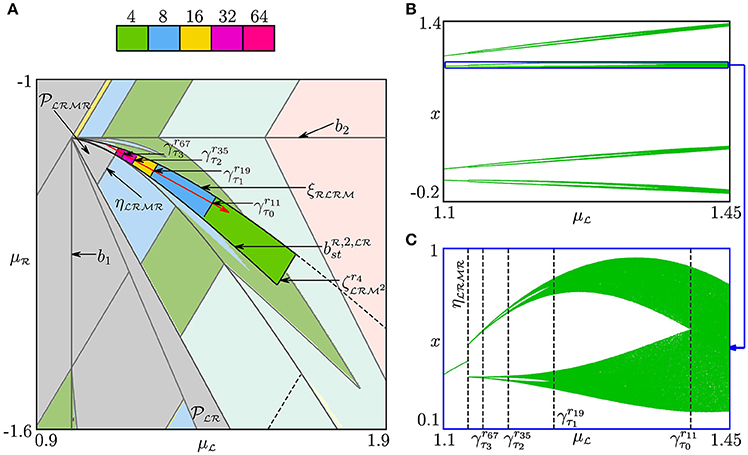

Figure 12. (A) Bifurcation structure of the region . Bifurcation diagram (B) along the arrow shown green in (A) and its enlargement (C).

We have described above bifurcations of cyclic chaotic intervals and the related boundaries in the neighborhood of of a PA-region . To obtain similar bifurcation boundaries in the neighborhood of one can swap symbols and as well as interchange the critical points ℓ and r in all analytic expressions.

In this section we describe another parameter domain , mentioned above, which is located in the neighborhood of an arbitrary left fin region of a PA-region . To describe bifurcation structure of we again use conjugacy with skew tent map and map replacement technique.

As the first example let us consider the left 2 · 2-fin region of the trunk region (see Figure Figures 12A). As explained in Section 4.2 the fin region has the BCB boundary related to the collision of the cycle with the border .

In Figure 13 we show the plot of f4 on the interval including the border point for parameter values located in the neighborhood of . The two linear pieces of f4 adjoining at are defined as

where , . If the conditions

are held, then there exists a local absorbing interval

for f4. The restriction is topologically conjugate to the skew tent map g with the slopes and .

Taking into account that , , and , the conditions (67) can be written as

The conjugacy between and g holds in the parameter region confined by the BCB boundary , the boundary

and the boundary

Note that for the map f the boundary (71) corresponds to an expansion bifurcation leading from to . Thus, the region is defined as

Figure 14A presents the region , where one can observe chaoticity regions , . The bifurcation boundaries separating these regions are related to transitions . To get expressions for these boundaries we use map replacement technique. Namely, we take the corresponding formulae (20) known for the skew tent map and apply the following replacement:

Here the symbolic sequence τj, j ⩾ 0, is derived from the harmonic ρj (18) by substituting instead of and instead of .

Figure 14. (A) Bifurcation structure of the region . Bifurcation diagram (B) along the arrow shown red in (A) and its enlargement (C).

Summing up we can describe in the following way. The region consists of t + 1 chaoticity regions , , where t ⩾ 1 depends on , . If the parameter point p crosses the boundary between the chaoticity regions and , given by

then the merging bifurcation takes place. Here . In Figure 14A the merging bifurcation boundaries , , , and are shown. See also 1D bifurcation diagrams in Figures 14B,C.

In a similar way we characterize the region , related to the boundary of the left k · n-fin , , of the trunk region , k ⩾ 2, n ⩾ 2. In order to determine the branches of fkn which are adjacent to one another at the border point, we rewrite the symbolic sequence associated with the fin cycle as follows:

Here the underlined symbols and are associated with the points , such that collides with at , while collides with at . We introduce the abbreviation

and rewrite the symbolic sequence (74) as . Then the points and become and , respectively. Then in the neighborhood of the iterate fkn is given by

Here and are the preimages of such that

The map fkn has in the neighborhood of a local absorbing interval

whenever the conditions

are held. The restriction is topologically conjugate to the skew tent map g with

Taking into account that , , and , the conditions (77) can be rewritten as

Therefore, the region in which the asymptotic dynamics of f can be studied by using the skew tent map g with the slopes given in (78), is confined by the BCB boundary , the border

and the expansion bifurcation boundary

Accordingly, the region is given by

To sum up we state

Proposition 5 ([17]). The region consists of t+1 chaoticity regions , , where t ⩾ 1 depends on , . Each pair of contiguous chaoticity regions and is separated by the merging bifurcation boundary which is derived from (20) applying the following replacement

where τj is obtained from the harmonic ρj (18) by replacing with and with .

As before, to describe bifurcation structure of the parameter domain , located in the neighborhood of an arbitrary right fin region of a PA-region , one can interchange and as well as the critical points ℓ and r in all analytic expressions.

As one can see in Figure 10, between the regions and there are more bifurcation boundaries related to some homoclinic bifurcations. In contrast to the previous two sections, where chaotic intervals were associated with only one border point, or , here we consider the case when chaotic intervals include both border points. This makes impossible direct usage of the results known for the skew tent map.

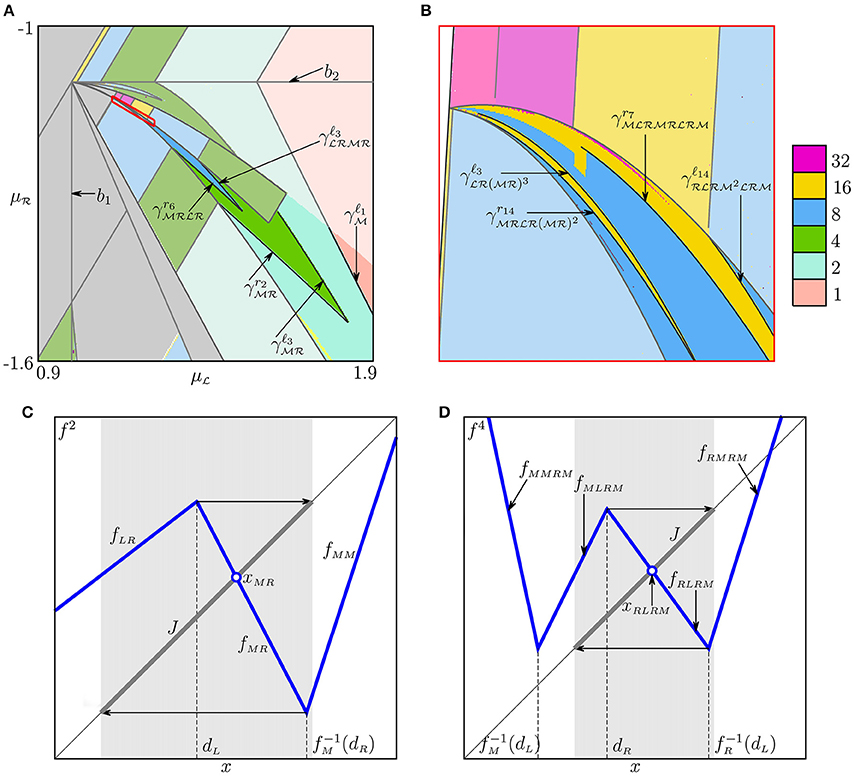

In Figures 15A,B we show the area between the regions and . As one can observe there are several bifurcation boundaries issuing from the curves (59) and (70). Right below we briefly describe how these bifurcation boundaries can be derived.

Figure 15. (A) Chaoticity regions located between and ; In (B) the region outlined red in (A) is shown enlarged. (C) Local absorbing interval of f2 including for immediately after crossing . (D) Local absorbing interval of f4 including for immediately after crossing .

First, recall that is related to the condition . Until (that is, inside ), the local absorbing interval J of f2 includes only a single kink point . Hence, is defined by only two branches and . When there holds the opposite inequality , the absorbing interval J spreads over another kink point (to the right of ) and becomes

(see Figure 15C). Then consists of three branches: , , and . This transformation is similar to the one described in Section 5.1 for the original map f, where the parameter point p crosses the border b1. Hence, the bifurcation boundaries emerging from are of the same sort as D0-prolongations. Applying the replacement

to (51), one obtains the related analytic expressions for the mentioned boundaries.

Then we apply the replacement

to the additional boundary (52). Here the sequences τm and are obtained from the sequences ρm and , respectively, by replacing with and with . Recall, that ρm consists of the symbols and and is the m-th harmonic of [see (18) with and ], while is obtained from ρm by shifting the first symbol to the end of the symbolic sequence. Note that in (83), r must be replaced by the value which coincides with r, and that is why the replacement for r is not necessary.

To illustrate the described procedure let us consider the boundary shown in Figure 15A which corresponds to the transition . For f2 this transition is associated with the merging of 2-cyclic chaotic intervals into a single chaotic interval. Thus, we can apply the replacement (83) to the expression for the D0-prolongation [i.e., (51) with m = 0] obtaining

Likewise, we derive the expression for the boundary , which is associated with the transition , by using the expression for the D0-prolongation [i.e., (51) with m = 1]:

The other boundary associated with the same transition is derived from the boundary (52), m = 1, corresponding to another homoclinic bifurcation of . Applying (84) to we obtain

In Figure 15B one can also see the boundaries and , which correspond to the transition . Setting m = 2 and applying the replacement (83) to (51) and the replacement (84) to (52) we get

which implies

Analogously we consider the case where the parameter point p leaves the region crossing . When the condition is satisfied and the local absorbing interval J of f4 in the neighborhood of includes only two linear branches. Otherwise, the interval J spreads over the third branch and becomes

See Figure 15D. Thus, for f4 crossing the border is similar to crossing b1 for f. Consequently, the associated boundaries of chaoticity regions for can be derived as well from (51) and (52).

For example, the transition occurs at the boundaries and . We use the expressions for (51) and (52) with m = 2 to compute these mentioned boundaries. It is enough to apply the following replacements:

In this way we obtain

Regarding the merging bifurcation boundaries and marked in Figure 15A, it can be shown that is the D0-prolongation of , and is the D0-prolongation of .

So far all bifurcation boundaries of the regions , , and related to the transitions are fully described. However, in Figure 15B one can see that the region has further boundaries different from those described above. We can suggest that the regions , m ⩾ 4, have much more complicated form and may have other boundaries, whose description falls beyond the scopes of the current paper.

The above example can be generalized. That is, for an arbitrary PA-region we consider the are located between the regions and , k ⩾ 2. The bifurcation boundaries inside this area are derived in a similar way by using the relevant replacements (for details see [17]).

In this work we carry on studying asymptotic dynamics of a 1D continuous bimodal PWL map f with the two outermost slopes being positive. Previously we have described certain bifurcation structures related to regular as well as to chaotic dynamics of f. Three basic bifurcation structures have been identified: the skew tent map (STM) structure, the period adding (PA) structure, and the fin structure. In case of STM structure the points of a typical orbit are located on two neighbor branches only, so that f is reduced to the skew tent map. In case of PA structure the orbits belong to the outermost branches only, so that the results known for the discontinuous map defined on two partitions with positive slopes can be used. The fin structure is constituted by periodicity regions that have a common boundary with PA-regions. The analytic expressions for bifurcation boundaries defined by BCBs, DFBs, as well as homoclinic bifurcations (such as merging and expansion) have been obtained.

In the current paper we have summarized the earlier results and described another family of tongues associated with regular dynamics observed in the parameter space of f. They emerge from the boundary b1/b2 that separates the parameter region D1/D2 where f is locally topologically conjugated to the skew tent map (STM structure) from the region D0 where all three branches can be involved in asymptotic dynamics. These tongues are closely related to the cycles whose symbolic sequences form the U-sequence. For parameters belonging to D1/D2 these cycles are located in the two adjacent partitions and are unstable (except for the basic cycles having one point in the middle partition, which can be stable). However, for parameters in D0 every such cycle has a new complementary cycle with a single point on the third branch. If the slope of the third branch is small enough, this new cycle is stable and one observes the related region in the parameter space of f. In the limit case when the third branch is horizontal (the slope is zero), for every U-sequence cycle from D1/D2 there exists the related periodicity region in D0. We refer to this situation as the “stabilization” of a U-sequence cycle.

The paper is the result of joint research, the contribution of every author is comparable to the others.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The work of AP and IS has been performed under the auspices of COST Action IS1104 “The EU in the new complex geography of economic systems: models, tools and policy evaluation.” The work of VA was partially supported by the German Research Foundation within the scope of the project “Organizing centers in discontinuous dynamical systems: bifurcations of higher codimension in theory and applications.”

1. ^Except the case where the left/the right branch lies on the main diagonal. In this particular situation every point / is a fixed point and has a stable set consisted of all its preimages, if they exist.

1. Avrutin V, Sushko I. A gallery of bifurcation scenarios in piecewise smooth 1d maps. In: Bischi GI, Chiarella C, Sushko I, editors, Global Analysis of Dynamic Models in Economics, Finance and the Social Sciences. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer (2012). p. 369–95.

2. Nusse HE, Yorke JA. Border-collision bifurcations including period two to period three for piecewise smooth systems. Phys D (1992) 57:39–57. doi: 10.1016/0167-2789(92)90087-4

4. Feigin MI. Doubling of the oscillation period with c-bifurcations in piecewise-continuous systems. Prikl Math Mekh. (1970) 34:861–9. doi: 10.1016/0021-8928(70)90064-x

5. Banerjee S, Karthik MS, Yuan G, Yorke JA. Bifurcations in one-dimensional piecewise smooth maps—theory and applications in switching circuits. IEEE Trans Circ Syst I (2000) 47:389–94. doi: 10.1109/81.841921

6. Zhusubaliyev ZT, Mosekilde E. Bifurcations and Chaos in Piecewise-Smooth Dynamical Systems. Singapore: World Scientific (2003).

7. Ito S, Tanaka S, Nakada H. On unimodal transformations and chaos II. Tokyo J Math. (1979) 2:241–59. doi: 10.3836/tjm/1270216321

8. Takens F. Transitions from periodic to strange attractors in constrained equations. In: Camacho MI, Pacifico MJ, Takens F, editors, Dynamical Systems and Bifurcation Theory. New York, NY: Longman Scientific and Techical (1987), p. 399–421.

9. Maistrenko YL, Maistrenko VL, Chua LO. Cycles of chaotic intervals in a time-delayed Chua's circuit. Int J Bif Chaos (1993) 3:1557–72.

10. Sushko I, Avrutin V, Gardini L. Bifurcation structure in the skew tent map and its application as a border collision normal form. J Differ Equ Appl. (2016) 22:582–629. doi: 10.1080/10236198.2015.1113273

11. Nusse HE, Yorke JA. Border-collision bifurcations for piecewise smooth one-dimensional maps. Int J Bif Chaos (1995) 5:189–207. doi: 10.1142/S0218127495000156

12. Sushko I, Agliari A, Gardini L. Bifurcation structure of parameter plane for a family of unimodal piecewise smooth maps: border-collision bifurcation curves. Chaos Solitons Fract. (2006) 29:756–70. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2005.08.107

13. Matsuyama K, Sushko I, Gardini L. Revisiting the model of credit cycles with Good and Bad projects. J Econ Theor. (2016) 163:525–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jet.2016.02.010

14. Sushko I, Gardini L. Degenerate bifurcations and border collisions in piecewise smooth 1D and 2D maps. Int J Bif Chaos (2010) 20:2045–70. doi: 10.1142/S0218127410026927

15. Banerjee S, Yorke JA, Grebogi C. Robust chaos. Phys Rev Lett. (1998) 80:3049–52. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.3049

16. Panchuk A, Sushko I, Schenke B, Avrutin V. Bifurcation structures in a bimodal piecewise linear map: Regular dynamics. Int J Bif Chaos (2013) 23:1330040. doi: 10.1142/S0218127413300401

17. Panchuk A, Sushko I, Avrutin V. Bifurcation structures in a bimodal piecewise linear map: chaotic dynamics. Int J Bif Chaos (2015) 25:1530006. doi: 10.1142/S0218127415300062

18. Avrutin V, Gardini L, Schanz M, Sushko I. Bifurcations of chaotic atttractors in one-dimensional piecewise smooth maps. Int J Bif Chaos (2014). 24:1440012. doi: 10.1142/S0218127414400124

19. Metropolis N, Stein ML, Stein PR. On finite limit sets for transformations on the unit interval. J Comb Theory (1973) A15:25–44. doi: 10.1016/0097-3165(73)90033-2

20. Hao BL. Elementary Symbolic Dynamics and Chaos in Dissipative Systems. Singapore: World Scientific (1989).

21. Agliari A, Gardini L, Sushko I. Bifurcation structure in a model of monetary dynamics with two kink points. In: Dieci R, He T, Hommes CH, editors, Nonlinear Economic Dynamics and Financial Modelling: Essays in Honour of Carl Chiarella. Festschrift for Carl Chiarella's 70th birthday. Cham: Springer (2014), p. 65–81.

22. Foroni I, Avellone A, Panchuk A. Sudden transition from equilibrium stability to chaotic dynamics in a cautious tâtonnement model. J Phys Conf Ser. (2016) 692:012005. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/692/1/012005

23. Gumovsky I, Mira C. Recurrences and Discrete Dynamical Systems, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag (1980).

24. Keener JP. Chaotic behavior in piecewise continuous difference equations. Trans Am Math Soc (1980) 261:589–604. doi: 10.1090/S0002-9947-1980-0580905-3

25. Gardini L, Tramontana F, Avrutin V, Schanz M. Border-collision bifurcations in 1D piecewise-linear maps and Leonov's approach. Int J Bif Chaos (2010) 20:3085–104.

26. Avrutin V, Schanz M, Gardini L. Calculation of bifurcation curves by map replacement. Int J Bif Chaos (2010) 20:3105–35. doi: 10.1142/S0218127410027581

27. Gardini L, Tramontana F. Border collision bifurcation curves and their classification in a family of 1D discontinuous maps. Chaos Solitons Fract. (2011) 44:248–59. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2011.02.001

Keywords: bimodal piecewise linear map, border collision bifurcation, border collision normal form, degenerate bifurcation, homoclinic bifurcation

Citation: Panchuk A, Sushko I and Avrutin V (2017) Bifurcation Structures in a Bimodal Piecewise Linear Map. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 3:7. doi: 10.3389/fams.2017.00007

Received: 24 June 2016; Accepted: 12 April 2017;

Published: 29 May 2017.

Edited by:

Fabio Lamantia, University of Calabria, ItalyReviewed by:

Elisabetta Michetti, University of Macerata, ItalyCopyright © 2017 Panchuk, Sushko and Avrutin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anastasiia Panchuk, YW5hc3Rhc2lpYS5wYW5jaHVrQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.