- 1Soil and Crop Science Department, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2Soil and Crop Sciences Department, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi, TX, United States

Herbicide-resistant Amaranthus palmeri poses a significant threat to cotton production in the US. Tillage, cover crops, crop rotations, and dicamba-based herbicide programs can individually provide effective control of A. palmeri, but there is a lack of research evaluating the above tactics in a system for its long-term management. Field trials were conducted near College Station and Thrall, TX (2019–2021) to evaluate the efficacy of dicamba-based herbicide programs under multiple cropping sequences and tillage types in a systems approach for A. palmeri control in dicamba-resistant cotton. The experimental design used was a split–split plot design. The main plots were no-till cover cropping, strip tillage, and conventional tillage. The subplots were cotton:cotton:cotton (CCC) and cotton:sorghum:cotton (CSC) sequences for 3 years within each tillage type, and sub-subplots were a weedy check (WC), a weed-free check (WF), a low-input program without residual herbicides (LI), and a high-input program with residual herbicides (HI). Using HI under the CSC sequence was the only system that provided >90% control of A. palmeri for 3 years across all tillage types and locations. By 2021, A. palmeri densities in the CSC sequence at College Station (4,156 plants ha−1) and Thrall (4,006 plants ha−1) are significantly low compared to the CCC sequence (31,364 and 9,867 plants ha−1, respectively) when averaged across other factors. Similarly, A. palmeri densities in HI at College Station (9,867 plants ha−1) and Thrall (1,016 plants ha−1) are significantly low compared to LI (25,653 and 13,365 plants ha−1, respectively) when averaged across other factors. We also observed that the CSC sequence reduced A. palmeri seed bank by at least 40% compared to the CCC sequence at both College Station and Thrall when averaged across other factors. Over 3 years, we did not observe significant differences between LI and HI for cotton yields at College Station (1,715–3,636 kg ha−1) and Thrall (1,569−1,989 kg ha−1). However, rotating cotton with sorghum during 2020 improved cotton yields by 39% under no-till cover cropping in 2021 at Thrall. These results indicate that using dicamba-based herbicide programs with residual herbicides and implementing crop rotations can effectively manage A. palmeri in terms of seasonal control, densities, and seed bank buildup across tillage types and environments.

Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) is an important commercial crop in the United States (US) in terms of both internal revenue and exports valued at more than US$21 billion (USDA ERS, 2023a). Approximately 50% of the US upland cotton was planted in Texas during 2022, of which more than 90% contained herbicide-resistant traits (USDA ERS, 2023b). Dicamba-resistant cotton was introduced into the US market in 2017 and was planted on >50% cotton acres in the southern US by 2020 (USDA Agricultural Marketing Service - Cotton and Tobacco Program Memphis, 2020). It facilitated the growers with the use of over-the-top postemergence (POST) applications of dicamba alone or combined with glyphosate and glufosinate for weed control in cotton (Merchant et al., 2013; Cahoon et al., 2015; Inman et al., 2016). Amaranthus palmeri is reported as the most common and troublesome weed in the US cotton production systems (Van Wychen, 2019), affecting yield and quality, especially during the early stage of crop growth. A. palmeri densities as low as 0.4 and 0.9 plants m−2 can reduce cotton yields by 67% and 92%, respectively (Rowland et al., 1999a; Webster and Grey, 2015). A. palmeri densities of 8 plants m−1 row can decrease cotton yield by 91% when weed and crop emerge simultaneously (Massinga et al., 2001; Bensch et al., 2003). Furthermore, with each increase of 1 plant 9.1 m−1 row at the two-leaf stage of cotton, yield can be reduced by 10.7%–11% (Rowland et al., 1999b). Similarly, yields can be reduced by 0.9% with every A. palmeri increase by 1 m2 at the three- and nine-leaf stages of cotton (MacRae et al., 2013).

The competitive abilities of A. palmeri can be attributed to high fecundity, extended germination periods, aggressive growth, and prolific seed production (Keeley et al., 1987; Ward et al., 2013). Outcrossing abilities within and between Amaranthus spp. (Franssen et al., 2001), increase the probability of finding a resistant individual under heavy selection pressure. A. palmeri can recover up to 78% of initial growth in just 21 days after initial foliage is removed (Browne et al., 2020) and produce up to 28,000 seeds when chopped 3 cm above the ground (Sosnoskie et al., 2014). It has an extended germination period from March to October (Keeley et al., 1987), which covers the entire cotton growing season in the southern US. Furthermore, the C4 photosynthetic mechanism helps to adapt to lower levels of light (Jha et al., 2008), thereby managing the constraints associated with strategies like cover cropping. A. palmeri can tolerate water stress conditions using osmotic adjustment as a drought tolerance mechanism (Ehleringer, 1983). Through these adjustments, stomata can stay open and continue carbon fixation (Ehleringer, 1985) in water-stress environments.

A. palmeri evolved resistance to most of the PRE and POST herbicides used in cotton in the US (Vulchi et al., 2022). A population of A. palmeri resistant to six different modes of action has been reported in Kansas (Shyam et al., 2021). In Texas, A. palmeri is resistant to glyphosate and atrazine has been reported (Heap, 2021). Gene amplification, a target site resistance mechanism (Chahal et al., 2017; Dominguez-Valenzuela et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2018; Chaudhari et al., 2020), reduced absorption, and impaired translocation, a nontarget site resistance mechanism, were discovered as mechanisms of resistance to glyphosate in A. palmeri (Gaines et al., 2010; Nakka et al., 2017; Palma-Bautista et al., 2019; Koo et al., 2021). Enhanced metabolism, a nontarget site resistance mechanism has been discovered as the mechanism of atrazine resistance in A. palmeri recently (Nakka et al., 2017; Chahal et al., 2019). Additionally, nontarget site resistance mechanisms were responsible for synthetic auxin resistance in weeds (Shyam et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2023).

With A. palmeri evolving both target and nontarget site resistance mechanisms to the commonly used herbicides in cotton, it is important to diversify the available weed management strategies by combining chemical and nonchemical strategies to achieve sustainable long-term weed control (Norsworthy et al., 2012). Dicamba-based herbicide programs have shown promise in providing long-term weed control in cotton (Oreja et al., 2022). Multiple POST applications of dicamba provide greater A. palmeri control compared to a single POST application (Cahoon et al., 2015). Residual herbicides, when applied at PRE and POST timings with dicamba, provide greater A. palmeri control than dicamba applications without residual herbicides (Inman et al., 2016). PRE + POST herbicide programs of dicamba, when combined with high cover crop biomass, provide greater A. palmeri control (Wiggins et al., 2017; Hand et al., 2021; Grint et al., 2022). However, reduced sensitivity to dicamba has been reported recently in A. palmeri populations of the High Plains regions of Texas (Garetson et al., 2019). A. palmeri has the ability to evolve resistance to a full dose of dicamba in three generations when exposed to sub-lethal doses (Tehranchian et al., 2017), and, agreeing with that, reduced control of A. palmeri was observed in East Texas in a grower field with dicamba-only use history from the past 3 years (S. Nolte, personal communication, January 11, 2023). On the other hand, nonchemical strategies like cover crops (Wiggins et al., 2017; Palhano et al., 2018; Denton et al., 2023), crop rotations (Ball, 1992; Liebman and Dyck, 1993; Martin and Felton, 1993), and tillage practices (Refsell and Hartzler, 2009; Farmer et al., 2017) can influence A. palmeri germination and its composition in the weed communities. When combined with herbicide programs, they can be effective in managing GR A. palmeri (Aulakh et al., 2012; Aulakh et al., 2013). Therefore, this study was conducted to provide Texas cotton growers with sustainable weed control solutions by evaluating combinations of dicamba based herbicide programs, cropping sequences, and tillage types in a systems approach looking at long-term GR A. palmeri management and crop yields.

Materials and methods

Field experiments were conducted from 2019 to 2021 at Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Farm near College Station, TX (30°30′40.3″N 96°25′06.7″W) and Stiles Farm near Thrall, TX (30°36′04.4″N 97°18′06.5″W). The soil texture is belked clay with a pH of 8.1, 18% sand, 29% silt, 53% clay, and 1.5% organic matter at College Station, and Branyon clay with a pH of 6.0 18% sand, 35% silt, 47% clay, and 2.5% organic matter at Thrall (USDA - NRCS, 2022). Both locations share cation exchange capacity values of 30–45 meq 100 g−1 of soil, indicating their ability to retain more cations and salinity of 0–2 mmhos cm−1 of soil, indicating low electrical conductivity (USDA - NRCS, 2022). The location at College Station had overhead linear irrigation (Valley® Linears, A Valmont Industries Inc, NE 68064 USA), whereas Thrall was a rainfed/dryland environment. The experimental design was a randomized complete block design with a split–split plot arrangement of treatments. The main factors included no-till cover cropping, strip tillage, and conventional tillage blocks, each measuring 24.4 m wide and 36.6 m long. The ‘Expresso’ spring wheat variety was planted as the cover crop in 2019 and 2021, and the ‘LCS Trigger’ spring wheat variety was planted in 2020. These varieties were planted at 115 kg ha−1 under irrigated conditions and at 65–75 kg ha−1 under dryland conditions using a no-till seed drill following the forage seeding rates for wheat in Texas. Glyphosate (Roundup PowerMax, Bayer Crop Sciences, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 1.54 kg ai ha−1 rate was used to terminate the cover crop 4 weeks before planting main crops. One strip tillage activity was carried out from 2019 to 2021 near College Station. No strip tillage activity was carried out in 2019 due to earlier wet conditions near Thrall, but one strip tillage activity was carried out during the 2020 and 2021 cropping seasons. Only one disking activity was carried out in a conventional tillage block in 2019 due to earlier wet conditions during spring. However, two disking activities were carried out in 2020 and 2021, one during late fall and another within a week before planting, according to local practices.

The cropping sequence served as the split–plot factor, with half of each tillage type practiced under cotton:cotton:cotton (CCC) sequence and the other half under cotton:sorghum:cotton (CSC) sequence over the 3 years. Each split plot measured 12.2 m wide and 36.6 m long. Dicamba-resistant cotton variety DP 1646 B2XF and grain sorghum variety DK57-07 were planted at a targeted population of 112,000 plants ha−1 and 170,000 plants ha−1, respectively. Herbicide programs served as the split–split plot factor. A weedy check (WC), weed-free check (WF), low input herbicide program (LI), and a high input herbicide program (HI) were applied to four rows of cotton or sorghum measuring 3 m wide and 9.1 m long in each cropping sequence and replicated four times. In both cotton and sorghum, HI included a preemergence application (PRE) at planting, a mid-postemergence (MPOST) application, and a lay-by as postdirected (PDIR) application; LI included an early-postemergence (EPOST) application and a late-postemergence (LPOST) application; WF were maintained using herbicide applications and hand weeding; WC did not receive any form of weed management. MPOST, PDIR in HI, and EPOST, LPOST in LI are hereafter referred to as the first (POST 1) and second (POST 2) postemergence applications, respectively. POST applications in both herbicide programs were applied based on the A. palmeri densities every year and not by the growth stage of the main crop. All herbicide applications were made using a CO2-propelled backpack sprayer with a six-nozzle boom delivering 140 L ha−1 at 234 kPa. PRE applications were made using Drift Guard (DG)11002 nozzles, POST applications were made using Turbo TeeJet Induction (TTI) 11002 nozzles, and PDIR applications were made using TTI 9504E nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Springfield, IL, USA).

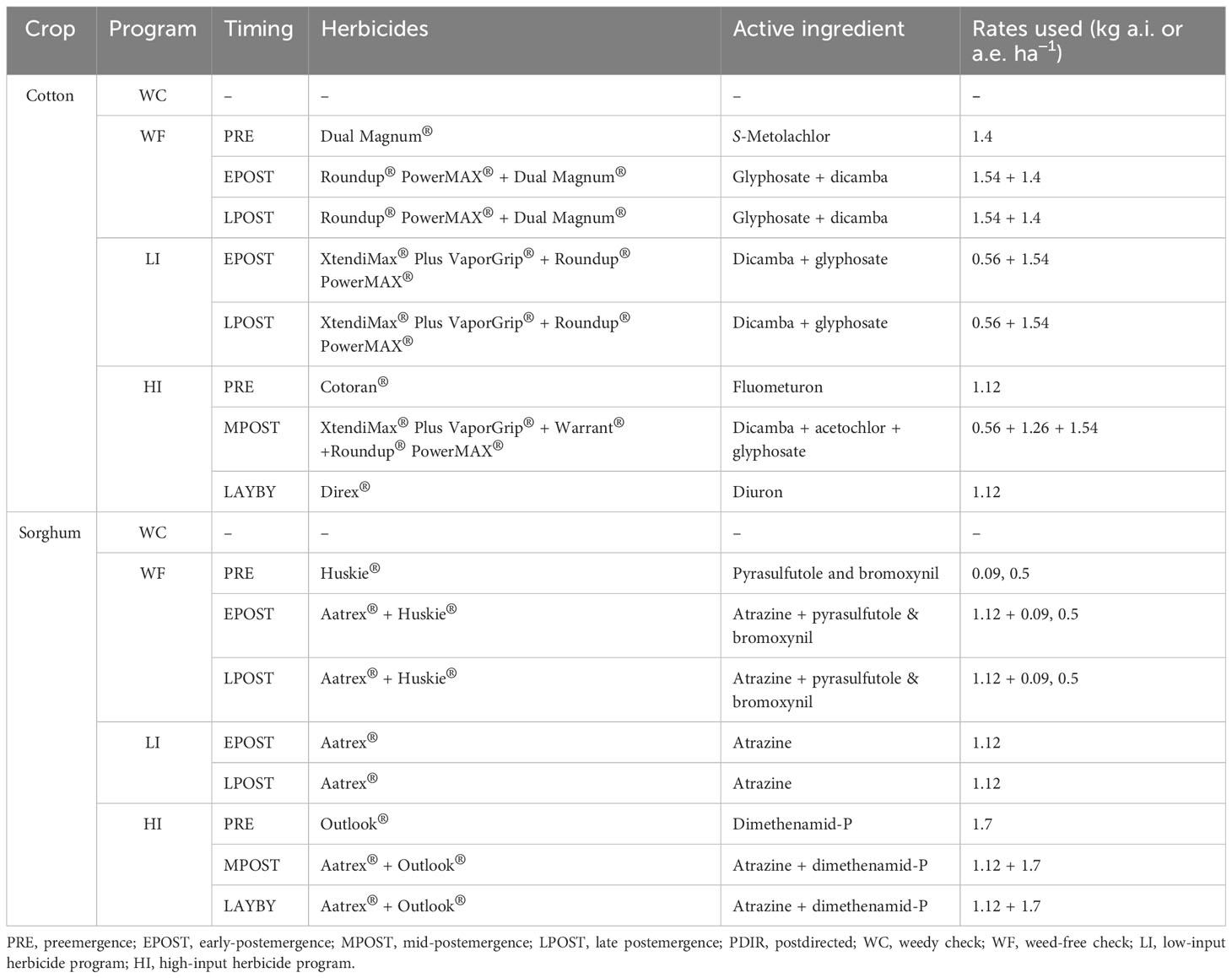

The timeline of activities from planting cover crops to harvesting main crops is listed in the Supplementary Data. Herbicide programs, active ingredients, application timing, and rates applied are listed in Table 1. Along with the natural seed bank, a known population of at least 1,000 GR A. palmeri seeds were broadcast in each herbicide plot prior to planting in 2019 and were allowed to go to seed at the end of each year at both locations. All treatments were applied to the same area for 3 years to evaluate the compounding effect of treatments for seasonal and long-term A. palmeri control, densities, seed bank, cotton, and sorghum yields. Visual A. palmeri control was rated from 0 to 100, where 0 is no control and 100 is complete control (Frans, 1986). Except during 2019 in College Station, when cotton plots were harvested using a four-row cotton stripper, a sub-sample from 0.004 ha (1/100th acre) area in each cotton plot was hand-harvested at College Station and Thrall from 2019 to 2021. Grain sorghum was harvested from the middle two rows using a Wintersteiger plot combine (Wintersteiger Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, USA) at both locations. When cotton stripper was used, 7.6 m of the middle two rows of each four-row plot were harvested. All the sub-samples in each plot were interpolated to per-hectare yields for statistical analysis. Harvested seed cotton was ginned on a 20-saw table to calculate the lint percentages separately. Cover crop biomass was randomly harvested from the middle of each plot using three 0.25 m2 quadrats on the day of termination in 2020 and 2021. Biomass samples were oven-dried at 55°C for 24 h before dry weights were collected. Similarly, A. palmeri densities were recorded from three randomly selected 0.25 m2 areas in the middle of two rows of each plot during 2020 and 2021.

Table 1 Herbicides, application timings, active ingredients, and rates in respective herbicide programs used in cotton and sorghum used from 2019 to 2021 in College Station and Thrall, TX.

A. palmeri seed bank data collection

Ten 5-cm-wide, 15-cm-long soil cores were collected from LI and HI plots within a week after harvest from 2019 to 2021 at both locations. A total of 480 (2 herbicide programs × 2 cropping sequences × 3 tillage types × 4 replications × 10 soil cores) soil cores were collected each year using a probe truck. A. palmeri seeds were separated from soil in the cores by running water through the soil using fabric organza bags at the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture at Texas A&M University, College Station. Later, the seeds were collected, counted under a microscope, and stored at −10°C. Though density and seed bank data were not collected from the WC plots, comparing LI to HI can provide an understanding of the relative effectiveness of these strategies.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Percent A. palmeri control, seed bank data, seed cotton, and grain sorghum yields were collected from 2019 to 2021. Additionally, A. palmeri densities at 28 DA POST 2 timing in 2020 and 2021 were recorded. Weed control data were collected at 28 DA PRE, POST 1, POST 2, and a week before harvest at both locations. Data were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model, PROC GLIMMIX (Statistical Analysis Systems, version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Tillage, cropping sequence, herbicide programs, and locations were considered fixed variables. Years and replications nested within a location were considered random variables. Effects and interaction means were separated using Tukey’s LSD at p(α) = 0.05.

Results

A. palmeri control

Location, rating timing, year, tillage, cropping sequence, herbicide programs, and their two-way, three-way, four-way, and five-way interactions were significant for A. palmeri control (Supplementary Data). Therefore, data were separated by location, tillage, year, and rating timing to understand the influence of cropping sequence and herbicide programs on A. palmeri control in each tillage type at College Station and Thrall (Supplementary Data).

College Station

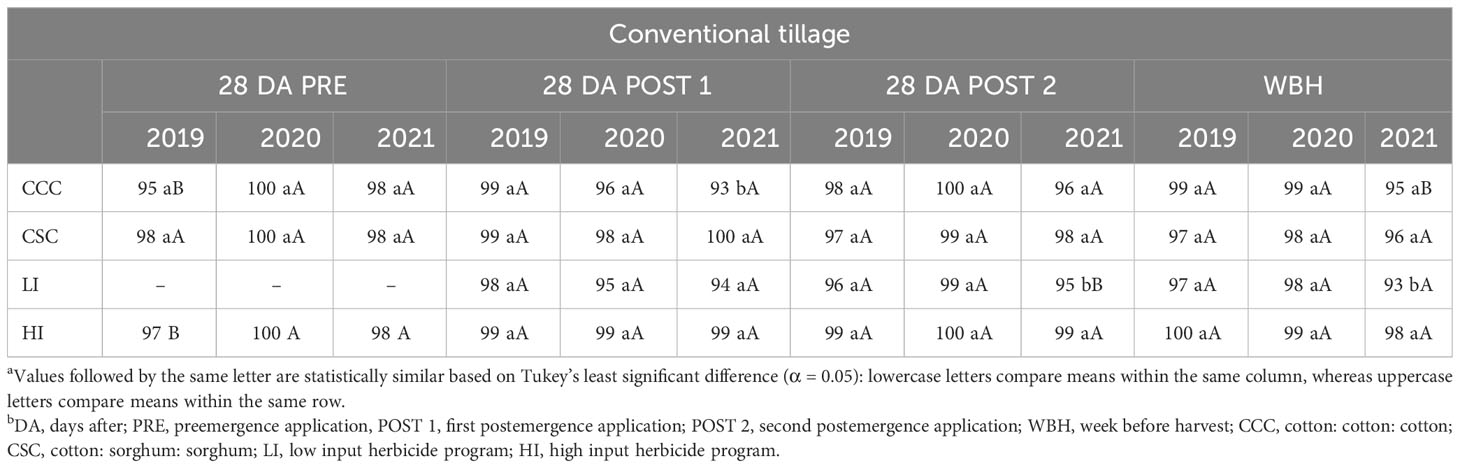

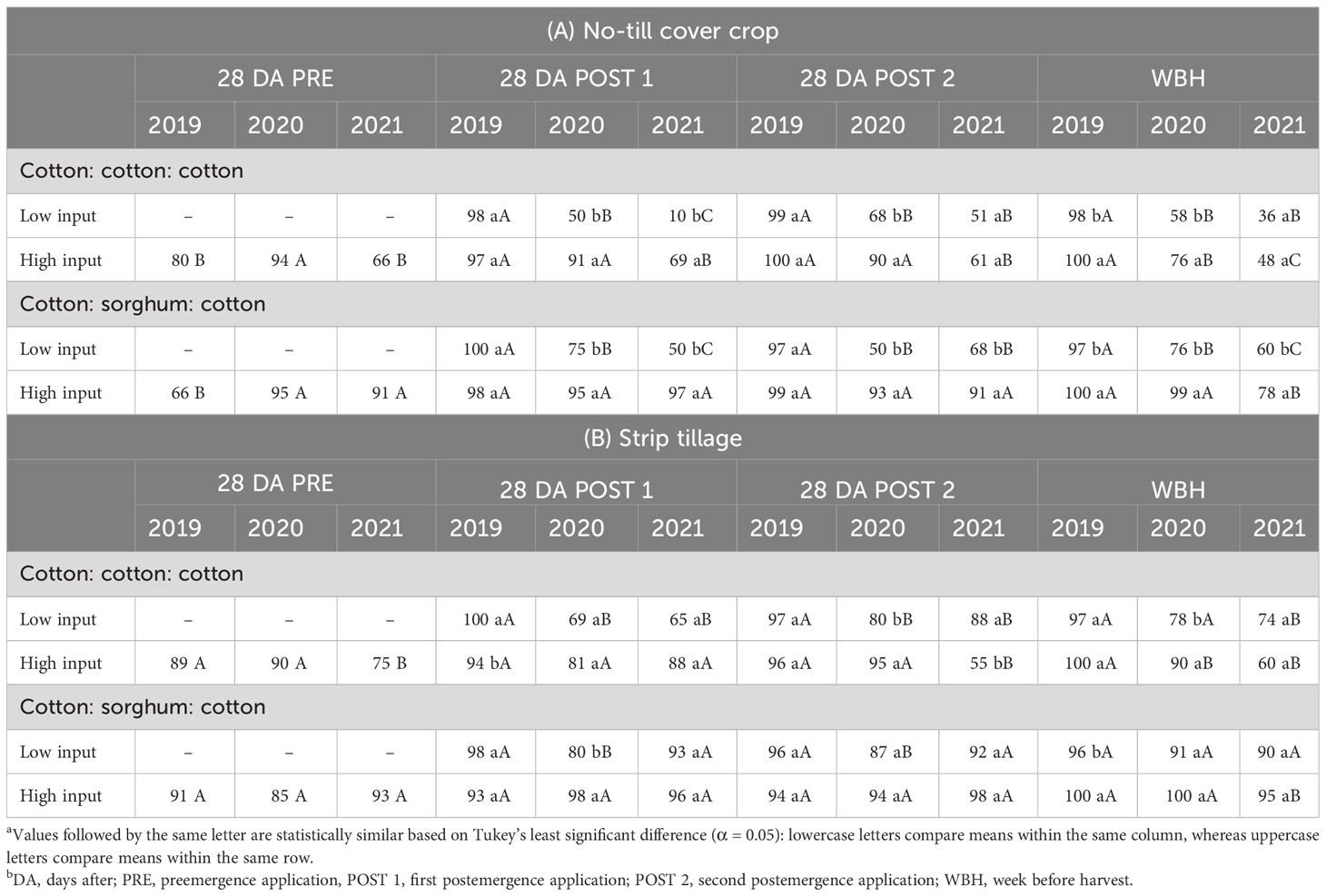

In conventional tillage, significant differences were not detected between herbicide programs, cropping sequences, or their interaction for A. palmeri control in 2019 and 2020. Greater than 95% A. palmeri control was observed until a week before harvest during the first 2 years, averaged across herbicide programs and cropping sequences. In 2021, HI plots that received residual herbicides at PRE and POST timings for 3 consecutive years resulted in ≥98% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest in both cropping sequences (Table 2). In no-till cover cropping, we observed ≥97% A. palmeri control in both herbicide programs until a week before harvest in 2019. In 2020, at least 90% A. palmeri control was recorded in HI plots in both cropping sequences until 28 DA POST 2. However, POST 1 application in LI failed to provide >75% control in both cropping sequences, which compounded until harvest (Table 3A). Low cover crop biomass content of 1,841 kg ha−1 (Supplementary Data), absence of overlapping residuals, and high early season A. palmeri densities resulted in a drastic reduction of A. palmeri control in LI plots during 2020. Additionally, POST 1 application in LI plots in cotton during 2020, is overall the third POST application of dicamba after the research began in 2019. Previous research reported the potential of A. palmeri populations evolving resistance to dicamba after three generations (Tehranchian et al., 2017). In 2021, >90% A. palmeri control was observed only in HI plots under CSC sequence up to 28 DA POST 2 application. By a week before harvest, only HI plots under the CSC sequence provided >75% A. palmeri control while, other herbicide program × cropping sequence combinations provided only ≤60% control. In LI plots under the CCC sequence, control dropped from 100% in 2019 to 36% in 2021 (Table 3A). This dramatic reduction in A. palmeri control can be attributed to lower levels of cover crop biomass, the use of only two modes of action for 3 years, and the compounded annual increase in A. palmeri densities. Overall, HI under the CSC sequence, the system that used seven different herbicide modes of action over 3 years provided >90% control up to 28 DA POST 2 applications for 3 years (Table 3A). In strip tillage, both herbicide programs provided ≥90% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest in 2019. In 2020, PRE-fb two POST applications in HI in both cropping sequences provided >90% control until a week before harvest (Table 3B). Similar to no-till cover cropping, POST applications in LI under the CCC sequence provided ≤80% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest. In 2021, both herbicide programs under the CSC sequence provided >90% control until a week before harvest, and two POST applications in LI under the CCC sequence provided 88% control until 28 DA POST 2 (Table 3B). Overall, using HI under the CSC system provided at least 90% control throughout the season from 2019 to 2021, and control in LI plots under the CCC sequence reduced from 97% in 2019 to 74% in 2021 (Table 3B). Poor control was observed in HI plots under the CCC sequence in both no-till cover cropping (48%) and strip tillage (60%), a week before harvest in 2021. In the 4 weeks after the layby application of diuron in 2021, College Station received 15 cm of precipitation (data not shown), which could have accounted for the poor control in these plots. Previous research (Whitaker et al., 2011; Houston et al., 2019) documented reduced A. palmeri control of up to 61% when more than a 12-cm precipitation was recorded after diuron application.

Table 2 Percent A. palmeri control as influenced by cropping sequence and herbicide programs at different timings in conventional tillage at College Station, TXa,b.

Table 3 Percent A. palmeri control as a function of significant interaction between cropping sequence and herbicide program in no-till cover cropping (A) and Strip tillage (B) in College Station, TXa,b.

Thrall

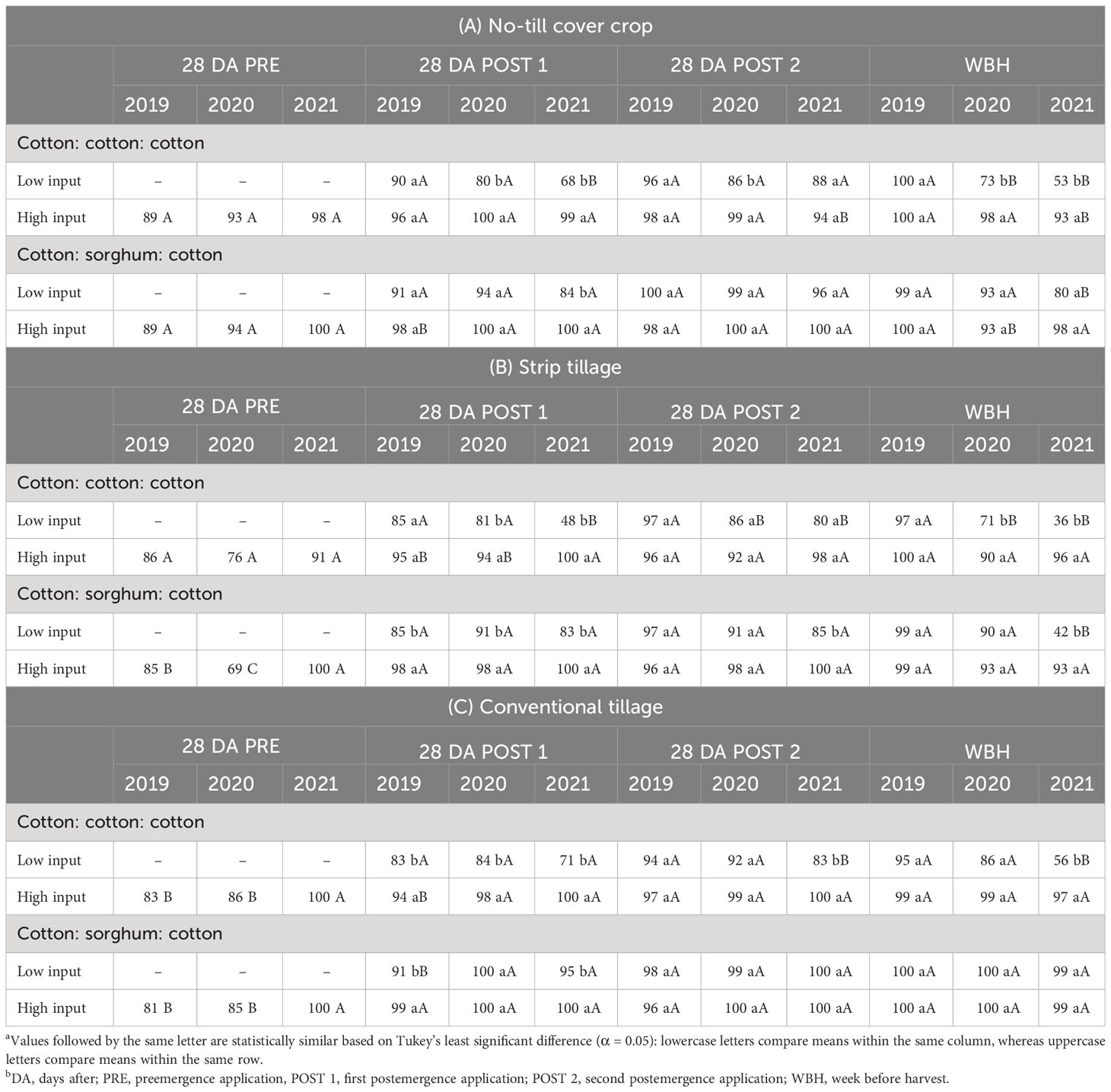

In conventional tillage, both herbicide programs provided >94% control after POST 2 application until a week before harvest in 2019 (Table 4C). In 2020 and 2021, both herbicide programs in the CSC sequence and HI in the CCC sequence provided ≥97% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest (Table 4C). A decline in control was observed from 95% in 2019 to 56% in 2021 a week before harvest in LI plots under the CCC sequence in 3 years (Table 4C). In no-till cover cropping, we observed ≥99% control in both herbicide programs until a week before harvest in 2019 (Table 4A). In 2020, both herbicide programs in the CSC sequence and HI in the CCC sequence provided ≥93% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest. However, LI provided only 73% control in CCC a week before harvest in 2020 (Table 4A). In 2021, HI provided ≥93% A. palmeri control in both cropping sequences until a week before harvest, while control was reduced to 53% in LI under the CCC sequence a week before harvest (Table 4A). In 3 years, A. palmeri control in LI plots under the CCC sequence reduced from 100% to 53% a week before harvest (Table 4A). In strip tillage, >95% A. palmeri control was recorded in both herbicide programs after the POST 2 application in 2019 (Table 4B). In 2020, both herbicide programs under the CSC sequence and the HI CCC sequence provided >90% A. palmeri control until a week before harvest. In 2021, HI provided ≥93% A. palmeri control compared to <50% control by LI in both cropping sequences a week before harvest (Table 4B). Overall, A. palmeri control was consistently >90% in HI plots in both cropping sequences, while control reduced from 97% to 36% in LI plots under the CCC sequence and from 99% to 42% in LI plots under the CSC sequence in 3 years (Table 4B).

Table 4 Percent A. palmeri control as a function of significant interaction between cropping sequence and herbicide program in no-till cover cropping (A) and strip tillage (B) and conventional tillage (C) in Thrall, TXa,b.

A. palmeri densities 28 DA POST 2

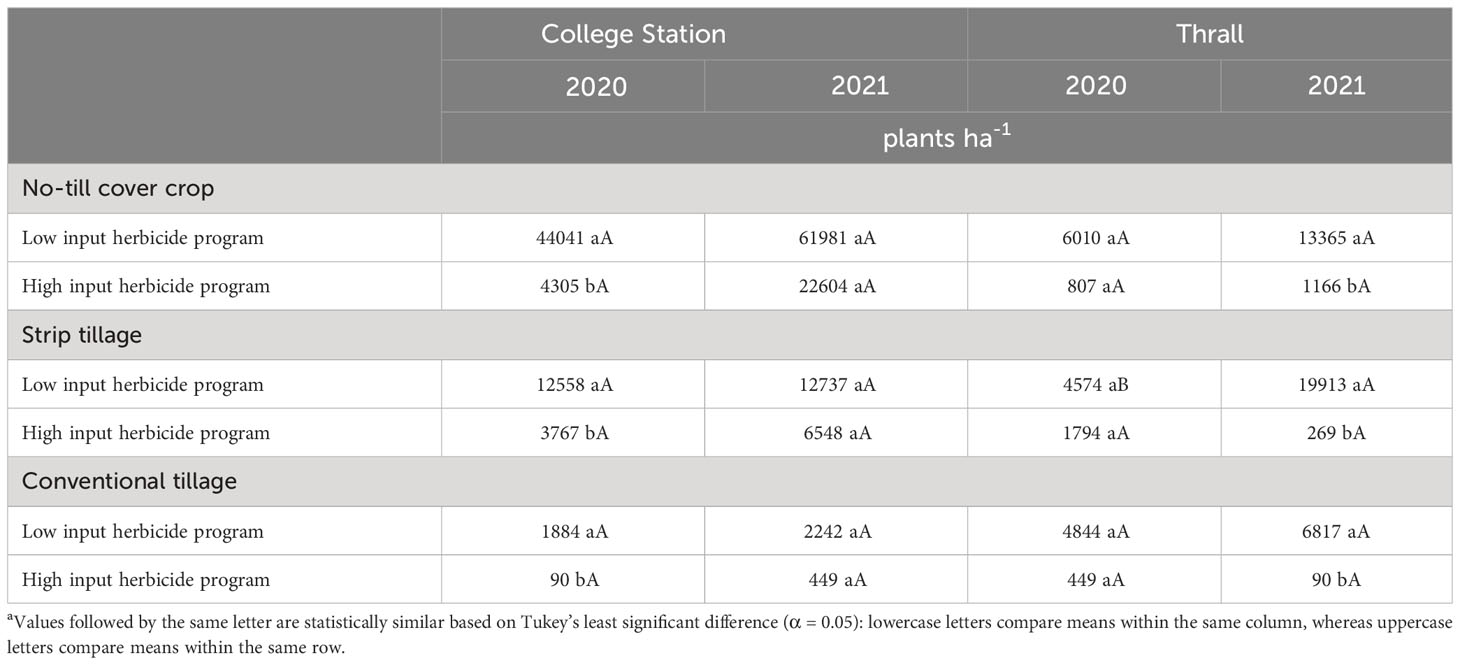

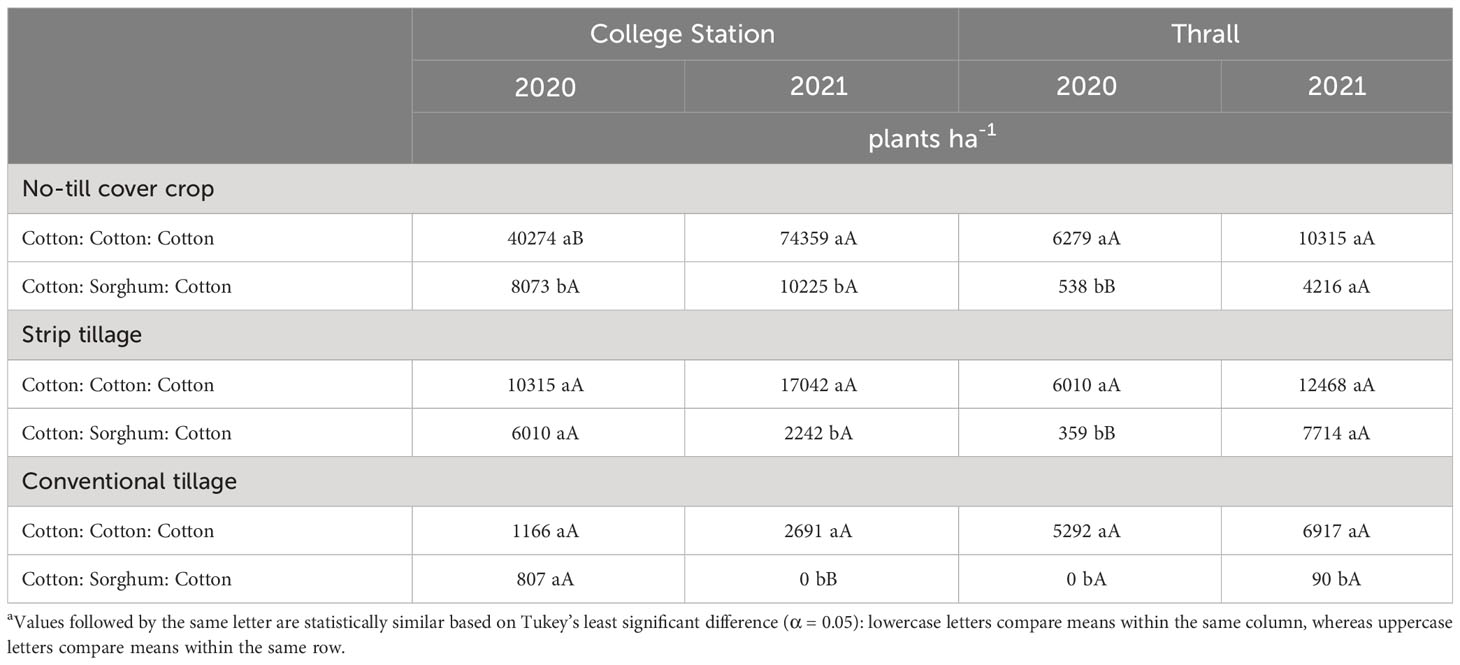

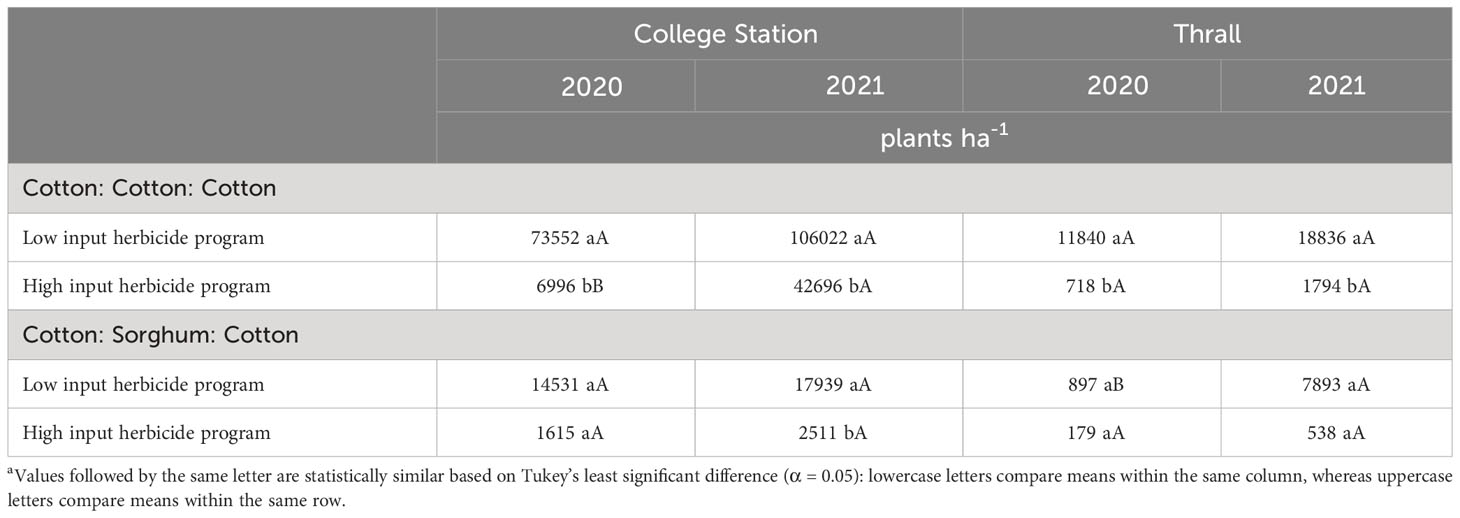

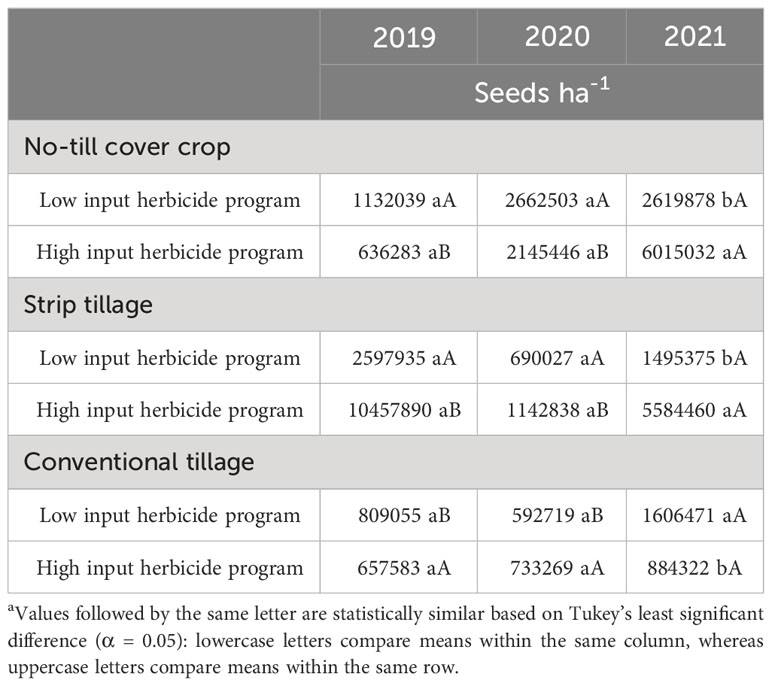

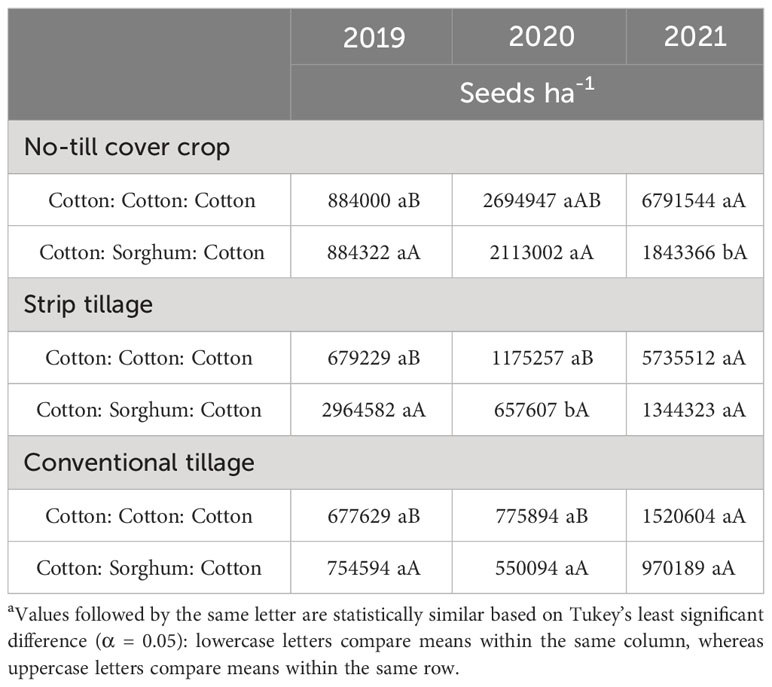

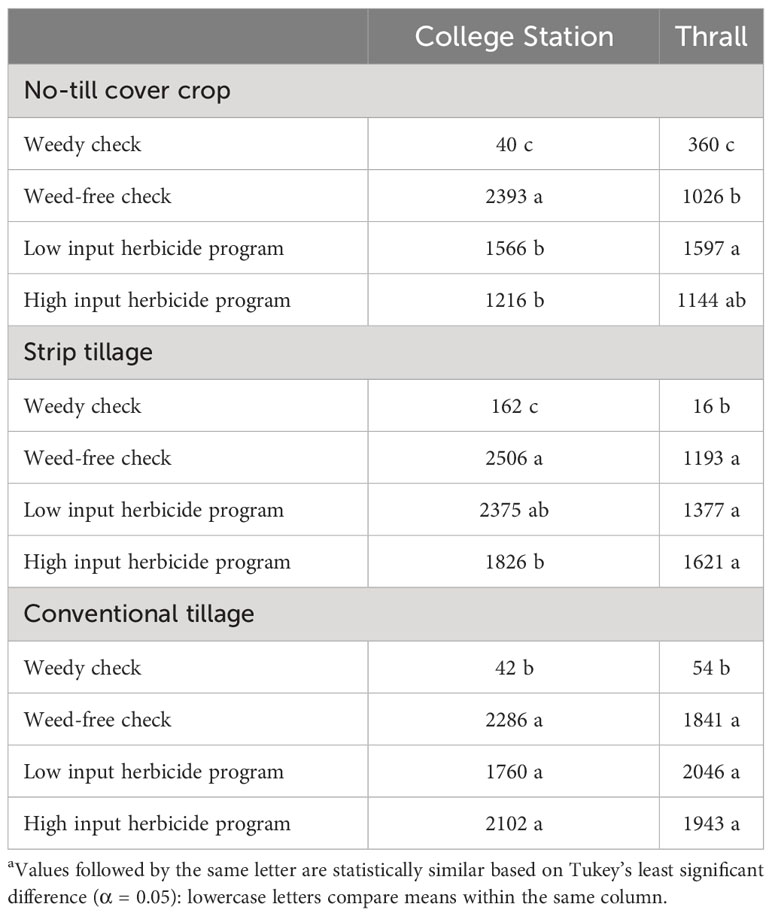

In 2020 and 2021, the cropping sequence and herbicide program influenced A. palmeri densities in all tillage types at both locations (Supplementary Data). Influence of tillage × herbicide program, tillage × cropping sequence, and cropping sequence × herbicide program on A. palmeri densities near College Station and Thrall are listed in Tables 5–7, respectively.

Table 5 A. palmeri densities as a function of significant interaction between tillage and herbicide program in 2020, 2021 at College Station and Thrall, TXa.

Table 6 A. palmeri densities as a function of significant interaction between tillage and cropping sequence in 2020, 2021 at College Station and Thrall, TXa.

Table 7 A. palmeri densities as a function of significant interaction between cropping sequence and herbicide program in no-till cover cropping in 2020, 2021 at College Station and Thrall, TXa.

College Station

In conventional tillage, A. palmeri densities in LI plots were at least 20 times higher compared to HI plots averaged across cropping sequences in 2020 (Table 5). Our results corroborate with Aulakh et al., (2012; 2013) who observed a >90% reduction in A. palmeri germination in plots that received a PRE + POST herbicide application in the inversion tillage over 3 years. In 2021, A. palmeri densities in the CCC sequence were 2,691 plants ha−1 compared to ~0 plants ha−1 in the CSC sequence averaged across herbicide programs (Table 6). In no-till cover cropping, A. palmeri densities increased significantly only in HI under the CCC sequence in 2 years, and densities were significantly higher in LI plots compared to HI plots during both years. Densities did not increase significantly over time in either herbicide program under the CSC sequence; however, densities of A. palmeri in LI plots were at least eight times higher than compared of HI plots under the CCC sequence in 2021 (Table 7). In strip tillage, A. palmeri densities in LI plots were at least two times higher than those in HI plots, averaged across cropping sequences in 2020 (Table 5). In 2021, A. palmeri densities in the CCC sequence were at least six times higher than those in the CSC sequence averaged across herbicide programs (Table 6). Previous research by Aulakh et al. (2012); Price et al. (2016); Wiggins et al. (2017); Palhano et al. (2018), and Hand et al. (2021) reported that high residue cover crops combined with residual herbicides provide the greatest suppression of A. palmeri and corroborate with our results. Failure to produce high biomass content in no-till cover cropping and the absence of soil cover in strip tillage, combined with a lack of residual herbicides, led to the increase in A. palmeri densities over time in LI plots. Significantly lower densities in CSC compared to the CCC sequence in 2021 were due to the thick mat of sorghum biomass from the previous year acting like a cover crop, preventing the germination of A. palmeri. Negative influences of crop diversification on weed seed germination have been previously reported by Weisberger et al. (2019) and Sharma et al. (2021).

Thrall

In conventional tillage, A. palmeri densities in LI plots were 74 times higher than those in HI plots averaged across cropping sequences in 2021. Though statistically insignificant, HI provided at least a 10-fold reduction in densities in 2020, while in 2021 a clear statistical separation was observed between HI and LI for A. palmeri densities (Table 5). Also, rotating cotton with sorghum during 2020 resulted in extremely low A. palmeri densities (0–100 plants ha−1) in 2020 and 2021 averaged across herbicide programs (Table 6). In no-till cover cropping, HI reduced A. palmeri densities by at least 15 times compared to LI under the CCC sequence in 2020 and by at least 10 times averaged across both cropping sequences in 2021 (Table 5). We observed a significant increase in A. palmeri densities from 2020 to 2021 in LI in the CSC sequence (Table 7). In strip tillage, A. palmeri densities in the CCC sequence were at least 15 times higher than those in the CSC sequence averaged across herbicide programs in 2020 (Table 6). During 2021, A. palmeri densities in LI plots were at least 74 times higher than those in HI plots averaged over cropping sequences (Table 5). We observed a significant increase in A. palmeri densities in LI plots (Table 5) and CSC sequence (Table 6) from 2020 to 2021.

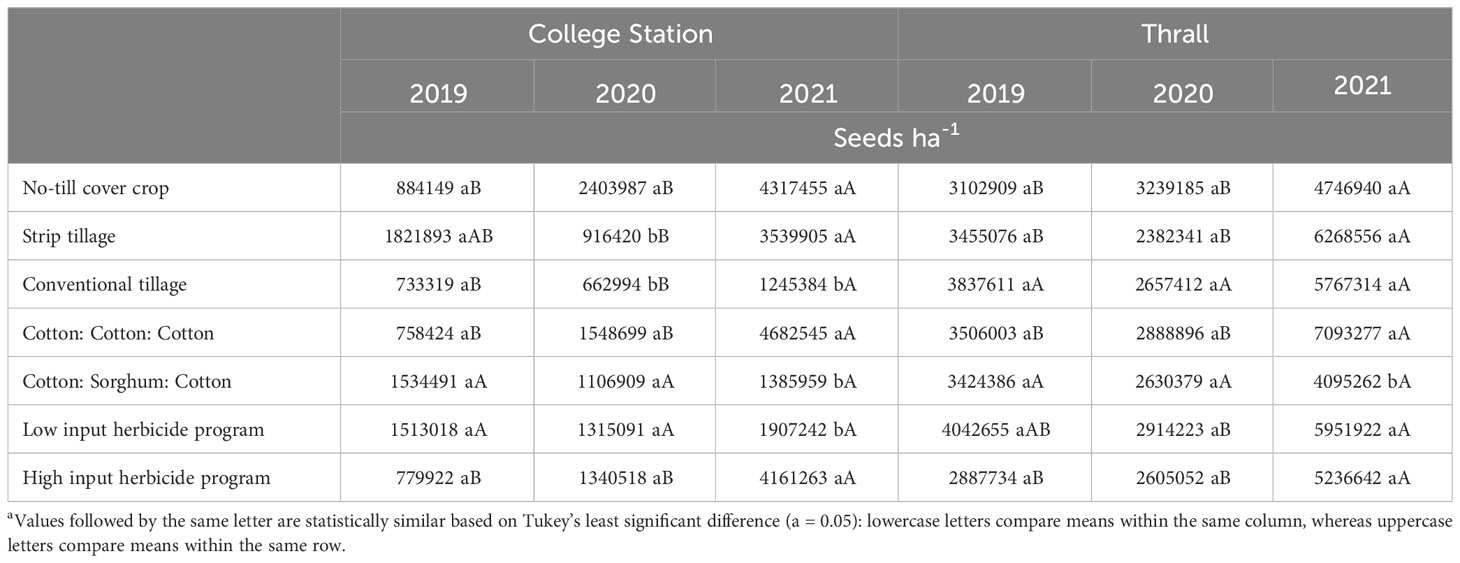

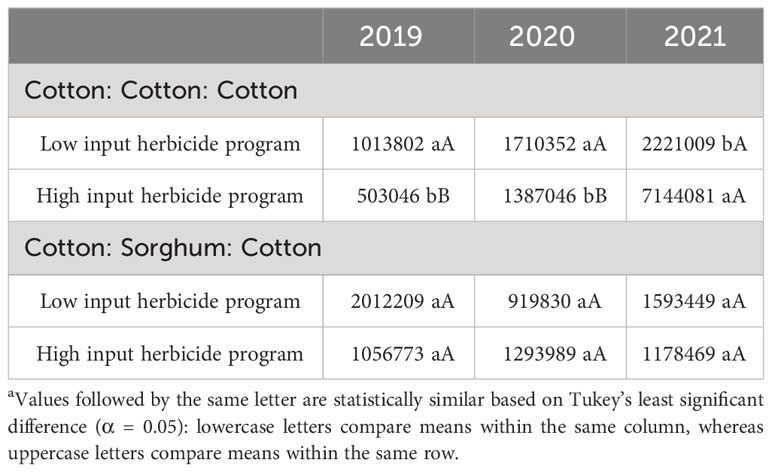

A. palmeri seed bank

College Station

None of the factors influenced A. palmeri seed bank during 2019. Tillage, cropping sequence, herbicide programs, and their interactions influenced A. palmeri seed bank in 2020 and 2021 (Supplementary Data). In 3 years, A. palmeri seedbanks in no-till cover cropping and strip tillage were at least 1.5 times higher than conventional tillage when averaged over other factors (Table 8). CSC sequence had only 33% of the seed bank CCC sequence in 3 years when averaged over other factors. Surprisingly, we observed a 50% higher seed bank in HI plots compared to LI plots, averaged over other factors (Table 8). Therefore, we evaluated tillage × herbicide program interaction in 2021 to understand this pattern more accurately (Table 9). In 3 years, HI plots accumulated at least two times the seed bank in LI plots under no-till cover cropping and in strip tillage. However, under conventional tillage, LI plots accumulated approximately two times the seed bank of HI plots (Table 9). Though the densities in HI plots were significantly lower than those in LI plots in no-till cover cropping and strip tillage, escapes were relatively large in size with numerous seed heads, which could explain the anomalously higher seed bank numbers. Also, no significant differences in seed banks were observed between cropping sequences in strip tillage and conventional tillage (Table 10). However, in no-till cover cropping, the CCC sequence accumulated three times more seed banks compared to the seed bank in the CSC sequence (Table 10). Also, using HI under the CSC sequence reduced the seed bank by three times compared to using it under the CCC sequence in all tillage types (Table 11). Increased A. palmeri densities along with reduced weed control at the end of each year could have possibly led to seed bank accumulation in no-till cover cropping and strip tillage.

Table 8 A. palmeri seedbank (ha-1) affected by tillage, cropping sequence and herbicide program in College Station and Thrall from 2019-21.

Table 9 A. palmeri seedbank (ha-1) as a function of significant interaction between tillage and herbicide program from 2019-21 at College Station, TXa.

Table 10 A. palmeri seedbank as a function of significant interaction between tillage and cropping sequence from 2019-21 at College Station, TXa.

Table 11 A. palmeri seedbank as a function of significant interaction between cropping sequence and herbicide program from 2019-21 at College Station, TXa.

Thrall

A. palmeri seed bank at Thrall was not influenced by tillage types, cropping sequences, or herbicide programs during 2019 and 2020. During 2021, only the cropping sequence influenced the A. palmeri seed bank (Supplementary Data). The CSC sequence reduced the seed bank by more than two million seeds per hectare (40% less) compared to the CCC sequence in 3 years. We also observed a 100% increase in A. palmeri seed bank in the CCC sequence from 2019 to 2021. Similarly, there was at least a 50% increase in A. palmeri seed bank in no-till cover cropping and strip tillage in 3 years (Table 8).

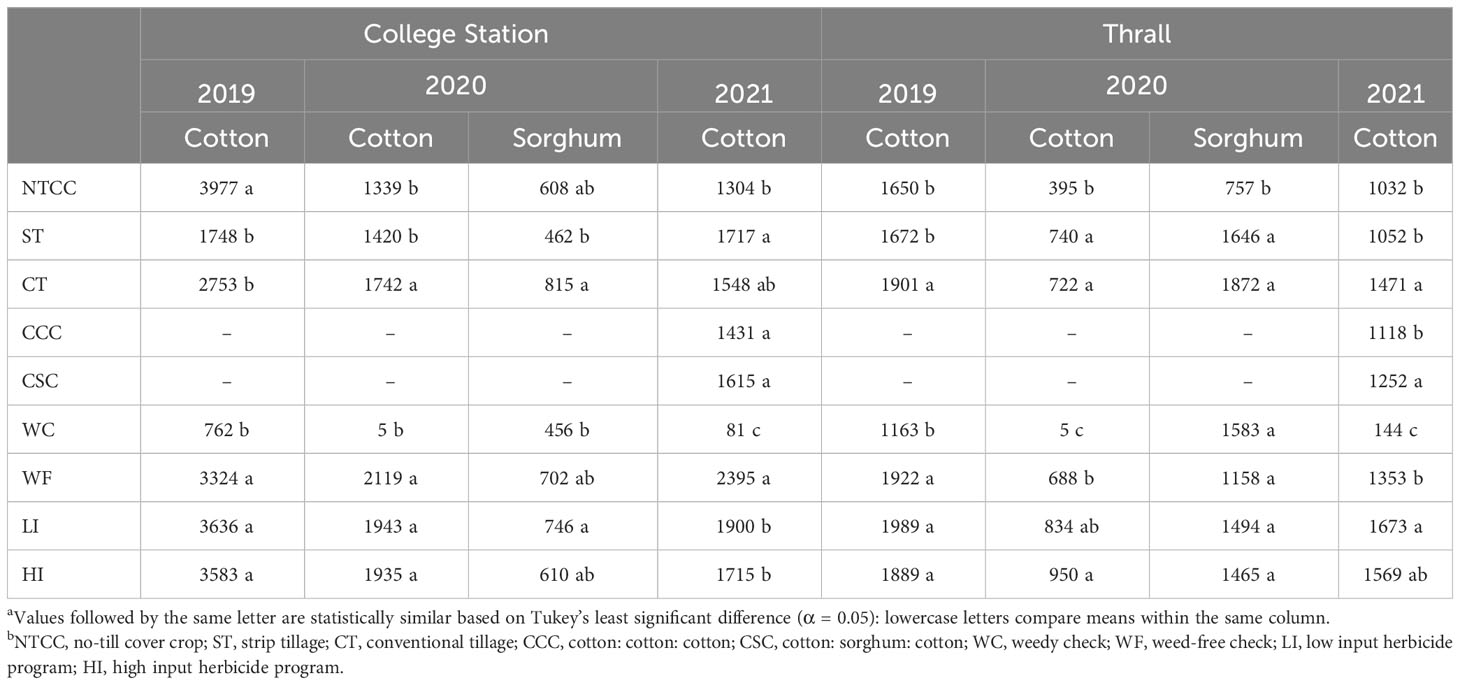

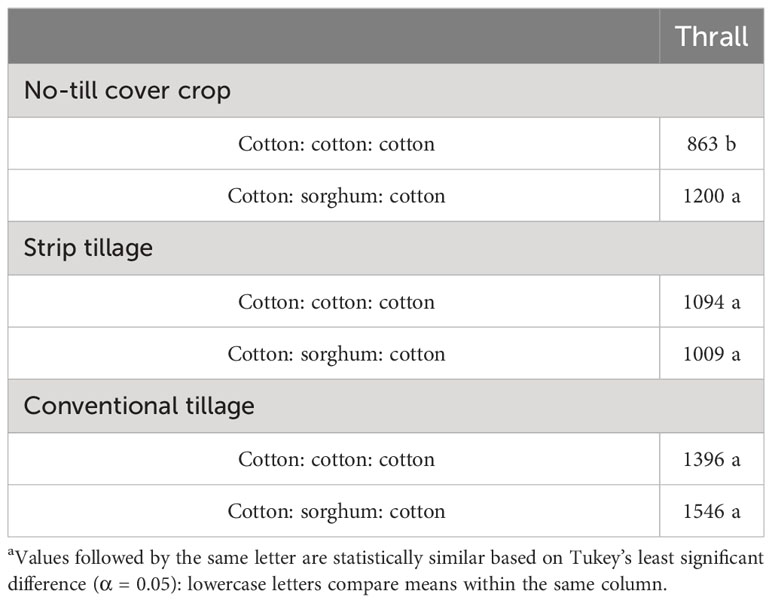

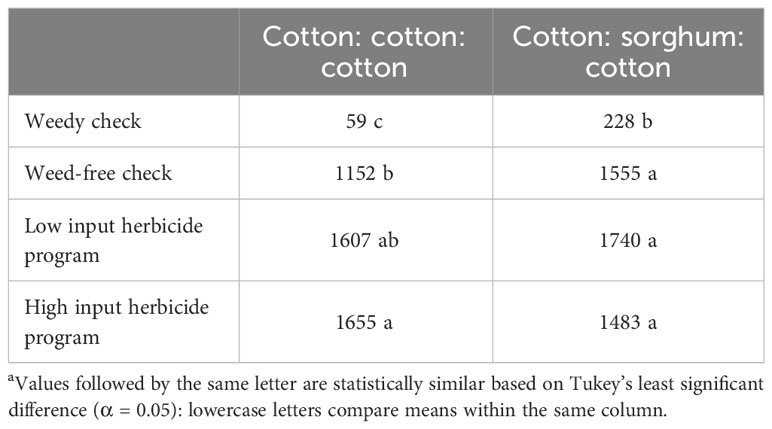

Cotton and sorghum yields

College Station

Tillage and herbicide programs influenced crop yields from 2019 to 2021. Tillage × herbicide program interaction was significant in 2021. The cropping sequence did not influence cotton yield in 2021 (Supplementary Data). Annual cotton yield from 2019 to 2021 and sorghum yield during 2020 were influenced by tillage type. In 2019, cotton yield in no-till cover cropping was 125% higher than strip tillage and 45% higher than conventional tillage averaged across herbicide programs (Table 12). In 2020, cotton yield in conventional tillage was 30% higher than no-till cover cropping and 23% higher than strip tillage averaged across herbicide programs (Table 12). Similarly, conventional tillage provided 34% higher sorghum yield than no-till cover cropping and 77% higher than strip tillage (Table 12). In 2021, strip tillage provided 11% higher cotton yield than conventional tillage and 14% higher than no-till cover cropping, averaged across cropping sequences and herbicide programs (Table 12). No significant differences were identified between LI plots and HI plots for cotton and sorghum yields from 2019 to 2021. Only in 2021, WF plots provided 40% and 26% higher cotton yields than HI plots and LI plots, respectively, in no-till cover cropping (Table 13).

Table 12 Seed cotton and grain sorghum yields as affected by tillage, cropping sequences and herbicide programs in College Station, Thrall TXa,b.

Table 13 Cotton yields (kg ha-1) in 2021 as a function of significant interaction between tillage and herbicide program at College Station and Thralla.

Thrall

In 2019 and 2020, tillage and herbicide programs influenced cotton yield, while only tillage level differences were observed for sorghum yield in 2020. In 2021, tillage, cropping sequence, herbicide programs, and their two-way interactions were significant (Supplementary Data). In 2019, conventional tillage provided cotton yields 15% higher than no-till cover cropping and 14% higher than strip tillage when averaged over herbicide programs (Table 12). No significant differences were observed in cotton yields between LI, HI, and WF plots averaged across tillage types (Table 12). In 2020, no significant differences were observed between strip tillage and conventional tillage for cotton and sorghum yields when averaged over herbicide programs (Table 12). Each of them provided at least 80% higher cotton yields and 110% higher sorghum yields compared to no-till cover cropping (Table 12). Sorghum yields did not vary significantly between herbicide programs averaged across tillage types (Table 12). In 2021, conventional tillage provided at least 40% higher cotton yield compared to strip tillage and no-till cover cropping, which averaged across other factors (Table 12). No significant differences were identified between LI plots and HI plots in strip tillage and conventional tillage, but they produced at least 11% higher cotton yields compared to WF plots in no-till cover cropping (Table 13). CSC provided 39% higher cotton yields compared to the CCC sequence under no-till cover cropping, while the yields were comparable under strip tillage and conventional tillage (Table 14). No significant differences were observed between LI plots and HI plots for cotton yield under the CSC sequence, but HI provided at least 43% higher yield compared to WF plots under the CCC sequence (Table 15).

Table 14 Cotton yields (kg ha-1) in 2021 as a function of significant interaction between tillage and cropping sequence at Thralla.

Table 15 Cotton yields (kg ha-1) in 2021 as a function of significant interaction between cropping sequence and herbicide program at Thralla.

Summary

In this study, we observed long-term A. palmeri control as a function of multiple factors, including the number of MOAs used over time. HI under the CSC sequence, which used seven different herbicide MOAs over 3 years, provided ≥90% A. palmeri control consistently across all tillage types and environments. On the contrary, A. palmeri control in LI under the CCC sequence, which used only two different herbicide MOAs over 3 years, reduced up to 36% by the end of the third year depending on the tillage type at both locations. These results indicate that the combination of overlapping residual herbicides applied PRE and POST, foliar applications with multiple MOAs over time, and introducing a higher biomass rotational grass crop can together prevent seasonal A. palmeri densities, and consequently reduce the soil seed bank. However, >90% control for HI under the CSC sequence provided a different understanding of each tillage type from A. palmeri densities point of view. At the end of the third year, A. palmeri densities were <1,000 plants ha−1 under conventional tillage compared to >8,000 plants ha−1 under strip tillage and no-till cover cropping. These findings not only indicate tillage as an effective tool for seasonal and long-term A. palmeri management, but also the potential for increased herbicide use in no-till systems, especially during times when cover crop establishment can be challenging. We believe continuing this research into the future could provide additional data and variability to observe separation in yields at the sub-sub-plot level. Especially with increasing densities and seed banks in LI plots under CCC cropping sequence in all tillage types, crop yields could be further reduced in subsequent cropping seasons. Alternatively, future research could address the longevity of best-performing weed control systems in this research by increasing the scale to a grower field level. Also, understanding how time-consuming and expensive long-term multi-location field experiments are, weed control data from this research can be used to build herbicide resistance prediction models similar to those developed by Neve et al. (2003). With the multitude of factors involved in this study that could have influenced weed control, developing economic models looking at net returns instead of only yields can give a better understanding of these weed control systems and their grower adoption potential. Combining the herbicide resistance prediction models with economic models can provide insights into which systems can be more sustainable for weed control from an economic point of view. Overall, crop rotations and herbicide programs with multiple MOAs provide greater weed control under conservation tillage systems, and tillage has additional weed control benefits.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RV: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. SN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JM: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources. BM: Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Bayer CropScience.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Extension Weed Science group at College Station and the farm crew at College Station, Thrall, and Corpus Christi for the technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fagro.2023.1277054/full#supplementary-material

References

Aulakh J. S., Price A. J., Enloe S. F., van Santen E., Wehtje G., Patterson M. G. (2012). Integrated Palmer amaranth management in glufosinate-resistant cotton: I. Soil-inversion, high-residue cover crops and herbicide regimes. Agronomy 2, 295–311. doi: 10.3390/agronomy2040295

Aulakh J. S., Price A. J., Enloe S. F., Wehtje G., Patterson M. G. (2013). Integrated Palmer amaranth management in glufosinate-resistant cotton: II. Primary, secondary and conservation tillage. Agronomy 3, 28–42. doi: 10.3390/agronomy3010028

Ball D. A. (1992). Weed seedbank response to tillage, herbicides, and crop rotation sequence. Weed Sci. 40, 654–659. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500058264

Bensch C. N., Horak M. J., Peterson D. (2003). Interference of redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri), and common waterhemp (A. rudis) in soybean. Weed Sci. 51, 37–43. doi: 10.1614/0043-1745(2003)051[0037:IORPAR]2.0.CO;2

Browne F. B., Li X., Price K. J., Langemeier R., Jauregui A.S.-S. d, McElroy J. S., et al. (2020). Sequential applications of synthetic auxins and glufosinate for escaped palmer amaranth control. Agronomy 10, 1425. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10091425

Cahoon C. W., York A. C., Jordan D. L., Everman W. J., Seagroves R. W., Culpepper A. S., et al. (2015). Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) management in dicamba-resistant cotton. Weed Technol. 29, 758–770. doi: 10.1614/WT-D-15-00041.1

Chahal P. S., Jugulam M., Jhala A. J. (2019). Mechanism of atrazine resistance in atrazine-and HPPD inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Wats.) from Nebraska. Can. J. Plant Sci. 99, 815–823. doi: 10.1139/cjps-2018-0268

Chahal P. S., Varanasi V. K., Jugulam M., Jhala A. J. (2017). Glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in Nebraska: confirmation, EPSPS gene amplification, and response to POST corn and soybean herbicides. Weed Technol. 31, 80–93. doi: 10.1614/WT-D-16-00109.1

Chaudhari S., Varanasi V. K., Nakka S., Bhowmik P. C., Thompson C. R., Peterson D. E., et al. (2020). Evolution of target and non-target based multiple herbicide resistance in a single Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) population from Kansas. Weed Technol. 34, 447–453. doi: 10.1017/wet.2020.32

Denton S., Raper T. B., Stewart S., Dodds D. (2023). Cover crop termination timings and methods effect on cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) development and yield. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 9, e20206. doi: 10.1002/cft2.20206

Dominguez-Valenzuela J. A., Gherekhloo J., Fernández-Moreno P. T., Cruz-Hipolito H. E., Alcántara-de la Cruz R., Sánchez-González E., et al. (2017). First confirmation and characterization of target and non-target site resistance to glyphosate in Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) from Mexico. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 115, 212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.03.022

Ehleringer J. (1983). Ecophysiology of Amaranthus palmeri, a Sonoran Desert summer annual. Oecologia 57, 107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00379568

Ehleringer J. (1985). Annuals and perennials of warm deserts (Physiological ecology of North American plant communities (Springer), 162–180. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-4830-3_7

Farmer J. A., Bradley K. W., Young B. G., Steckel L. E., Johnson W. G., Norsworthy J. K., et al. (2017). Influence of tillage method on management of Amaranthus species in soybean. Weed Technol. 31, 10–20. doi: 10.1614/WT-D-16-00061.1

Frans R. (1986). Experimental design and techniques for measuring and analyzing plant responses to weed control practices. Res. Methods Weed Sci., 29–46.

Franssen A. S., Skinner D. Z., Al-Khatib K., Horak M. J., Kulakow P. A. (2001). Interspecific hybridization and gene flow of ALS resistance in Amaranthus species. Weed Sci. 49, 598–606. doi: 10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0598:IHAGFO]2.0.CO;2

Gaines T. A., Zhang W., Wang D., Bukun B., Chisholm S. T., Shaner D. L., et al. (2010). Gene amplification confers glyphosate resistance in Amaranthus palmeri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 1029–1034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906649107

Garetson R., Singh V., Singh S., Dotray P., Bagavathiannan M. (2019). Distribution of herbicide-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in row crop production systems in Texas. Weed Technol. 33, 355–365. doi: 10.1017/wet.2019.14

Grint K. R., Arneson N. J., Arriaga F., DeWerff R., Oliveira M., Smith D. H., et al. (2022)Cover crops and preemergence herbicides: An integrated approach for weed management in corn-soybean systems in the US Midwest (Accessed May 1, 2023).

Hand L. C., Randell T. M., Nichols R. L., Steckel L. E., Basinger N. T., Culpepper A. S. (2021). Cover crops and residual herbicides reduce selection pressure for Palmer amaranth resistance to dicamba-applied postemergence in cotton. Agron. J. 113, 5373–5382. doi: 10.1002/agj2.20886

Houston M. M., Norsworthy J. K., Barber T., Brabham C. (2019). Field evaluation of preemergence and postemergence herbicides for control of protoporphyrinogen oxidase-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson). Weed Technol. 33, 610–615. doi: 10.1017/wet.2019.37

Hwang J.-I., Norsworthy J. K., Piveta L. B., Souza M. C., de C. R., Barber L. T., et al. (2023). Metabolism of 2,4-D in resistant Amaranthus palmeri S. Wats. (Palmer amaranth). Crop Prot. 165, 106169. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2022.106169

Inman M. D., Jordan D. L., York A. C., Jennings K. M., Monks D. W., Everman W. J., et al. (2016). Long-term management of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in dicamba-tolerant cotton. Weed Sci. 64, 161–169. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-15-00058.1

Jha P., Norsworthy J. K., Riley M. B., Bielenberg D. G., Bridges W. (2008). Acclimation of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) to shading. Weed Sci. 56, 729–734. doi: 10.1614/WS-07-203.1

Keeley P. E., Carter C. H., Thullen R. J. (1987). Influence of planting date on growth of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). Weed Sci. 35, 199–204. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500079054

Koo D.-H., Sathishraj R., Friebe B., Gill B. S. (2021). Deciphering the mechanism of glyphosate resistance in amaranthus palmeri by cytogenomics. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 161, 578–584. doi: 10.1159/000521409

Liebman M., Dyck E. (1993). Crop rotation and intercropping strategies for weed management. Ecol. Appl. 3, 92–122. doi: 10.2307/1941795

MacRae A. W., Webster T. M., Sosnoskie L. M., Culpepper A. S., Kichler J. M. (2013). Cotton yield loss potential in response to length of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) interference. J. Cotton Sci. 17, 227–232.

Martin R. J., Felton W. L. (1993). Effect of crop rotation, tillage practice, and herbicides on the population dynamics of wild oats in wheat. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 33, 159–165. doi: 10.1071/EA9930159

Massinga R. A., Currie R. S., Horak M. J., Boyer J. (2001). Interference of Palmer amaranth in corn. Weed Sci. 49, 202–208. doi: 10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0202:IOPAIC]2.0.CO;2

Merchant R. M., Sosnoskie L. M., Culpepper A. S., Steckel L. E., York A. C., Braxton L. B., et al. (2013). Weed response to 2, 4-D, 2, 4-DB, and dicamba applied alone or with glufosinate. J. Cotton Sci. 17, 212–218.

Nakka S., Thompson C. R., Peterson D. E., Jugulam M. (2017). Target site–based and non–target site based resistance to ALS inhibitors in palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). Weed Sci. 65, 681–689. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2017.43

Neve P., Diggle A. J., Smith F. P., Powles S. B. (2003). Simulating evolution of glyphosate resistance in Lolium rigidum II: past, present and future glyphosate use in Australian cropping. Weed Res. 43, 418–427. doi: 10.1046/j.0043-1737.2003.00356.x

Norsworthy J. K., Ward S. M., Shaw D. R., Llewellyn R. S., Nichols R. L., Webster T. M., et al. (2012). Reducing the risks of herbicide resistance: best management practices and recommendations. Weed Sci. 60, 31–62. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-11-00155.1

Oreja F. H., Inman M. D., Jordan D. L., Vann M., Jennings K. M., Leon R. G. (2022). Effect of cotton herbicide programs on weed population trajectories and frequency of glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). Weed Sci. 70, 587–594. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2022.41

Palhano M. G., Norsworthy J. K., Barber T. (2018). Cover crops suppression of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in cotton. Weed Technol. 32, 60–65. doi: 10.1017/wet.2017.97

Palma-Bautista C., Torra J., Garcia M. J., Bracamonte E., Rojano-Delgado A. M., Alcántara-de la Cruz R., et al. (2019). Reduced absorption and impaired translocation endows glyphosate resistance in Amaranthus palmeri harvested in glyphosate-resistant soybean from Argentina. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 1052–1060. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06105

Price A. J., Monks C. D., Culpepper A. S., Duzy L. M., Kelton J. A., Marshall M. W., et al. (2016). High-residue cover crops alone or with strategic tillage to manage glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in southeastern cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). J. Soil Water Conserv. 71, 1–11. doi: 10.2489/jswc.71.1.1

Refsell D. E., Hartzler R. G. (2009). Effect of tillage on common waterhemp (Amaranthus rudis) emergence and vertical distribution of seed in the soil. Weed Technol. 23, 129–133. doi: 10.1614/WT-08-045.1

Rowland M. W., Murray D. S., Verhalen L. M. (1999a). Full-season Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) interference with cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 47, 305–309. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500091815

Rowland M. W., Murray D. S., Verhalen L. M. (1999b). Full-season Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) interference with cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 47, 305–309. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500091815

Sharma G., Shrestha S., Kunwar S., Tseng T.-M. (2021). Crop diversification for improved weed management: A review. Agriculture 11, 461. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11050461

Shyam C., Borgato E. A., Peterson D. E., Dille J. A., Jugulam M. (2021)Predominance of metabolic resistance in a six-way-resistant palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) population (Accessed September 15, 2023).

Shyam C., Peterson D. E., Jugulam M. (2022). Resistance to 2,4-D in Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) from Kansas is mediated by enhanced metabolism. Weed Sci. 70, 390–400. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2022.29

Singh S., Singh V., Lawton-Rauh A., Bagavathiannan M. V., Roma-Burgos N. (2018). EPSPS gene amplification primarily confers glyphosate resistance among Arkansas Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) populations. Weed Sci. 66, 293–300. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2017.83

Sosnoskie L. M., Webster T. M., Grey T. L., Culpepper A. S. (2014). Severed stems of Amaranthus palmeri are capable of regrowth and seed production in Gossypium hirsutum. Ann. Appl. Biol. 165, 147–154. doi: 10.1111/aab.12129

Tehranchian P., Norsworthy J. K., Powles S., Bararpour M. T., Bagavathiannan M. V., Barber T., et al. (2017). Recurrent sublethal-dose selection for reduced susceptibility of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) to dicamba. Weed Sci. 65, 206–212. doi: 10.1017/wsc.2016.27

USDA Agricultural Marketing Service - Cotton and Tobacco Program Memphis (2020). Cotton Varieties Planted 2020 Crop. Available at: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/n870zq82k?locale=en.

USDA ERS (2023a) Cotton Wool. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/cotton-and-wool/ (Accessed May 3, 2023).

USDA ERS (2023b) Adopt. Genet. Eng. Crops US. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/adoption-of-genetically-engineered-crops-in-the-u-s/ (Accessed May 3, 2023).

USDA - NRCS (2022) Web Soil Survey. Available at: https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/ (Accessed 09-11-2022).

Van Wychen L. (2019). WSSA survey Ranks Most Common and Most Troublesome Weeds in Broadleaf Crops, Fruits and Vegetables.

Vulchi R., Bagavathiannan M., Nolte S. A. (2022). History of herbicide-resistant traits in cotton in the US and the importance of integrated weed management for technology stewardship. Plants 11, 1189. doi: 10.3390/plants11091189

Ward S. M., Webster T. M., Steckel L. E. (2013). Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri): a review. Weed Technol. 27, 12–27. doi: 10.1614/WT-D-12-00113.1

Webster T. M., Grey T. L. (2015). Glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) morphology, growth, and seed production in Georgia. Weed Sci. 63, 264–272. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-14-00051.1

Weisberger D., Nichols V., Liebman M. (2019). Does diversifying crop rotations suppress weeds? A meta-analysis. PloS One 14, e0219847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219847

Whitaker J. R., York A. C., Jordan D. L., Culpepper A. S., Sosnoskie L. M. (2011). Residual herbicides for Palmer amaranth control. J. Cotton Sci. 15, 89–99.

Keywords: dicamba-based herbicide programs, crop rotation, no-till cover cropping, strip tillage, conventional tillage, Palmer amaranth, seedbank, densities

Citation: Vulchi R, Nolte S, McGinty J and McKnight B (2023) Herbicide programs, cropping sequences, and tillage-types: a systems approach for managing Amaranthus palmeri in dicamba-resistant cotton. Front. Agron. 5:1277054. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2023.1277054

Received: 13 August 2023; Accepted: 29 September 2023;

Published: 24 October 2023.

Edited by:

Simerjeet Kaur, Punjab Agricultural University, IndiaReviewed by:

Navjot Brar, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, IndiaChandrima Shyam, Bayer, United States

Copyright © 2023 Vulchi, Nolte, McGinty and McKnight. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Scott Nolte, c2NvdHQubm9sdGVAYWcudGFtdS5lZHU=

Rohith Vulchi

Rohith Vulchi Scott Nolte

Scott Nolte Joshua McGinty2

Joshua McGinty2