- 1Hermiston Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Oregon State University, Hermiston, OR, United States

- 2United States Department of Agriculture, Prosser, WA, United States

- 3Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, United States

Developing plant germplasm that contains genetic resistance to insect pests is a valuable component of integrated pest management programs. In the last several decades, numerous attempts have been made to identify genetic sources of resistance to Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). This review focuses on compiling information regarding general L. decemlineata biology, ecology, and management focusing on discussing biochemical and morphological potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) plant traits that might be responsible for providing resistance; the review ends discussing past efforts to identify genetic material and highlights promising new strategies that may improve the efficiency of evaluation and selection of resistant material. Measurement strategies, that begin with field screening of segregating populations or wild germplasm to narrow research focus can be useful. Identifying particularly resistant or susceptible germplasm, will help researchers focus on studying the mechanisms of resistance in much greater detail which will help the development of long-term sustainable management program.

Introduction

Hundreds of crop varieties are released every year to improve crop productivity, enhance nutritional value, and expand consumer choice (Everson and Gollin, 2002); crops are also improved to repel, prevent, block, or eliminate pests (Mohammed et al., 2000; Rondon et al., 2009). Clearly, crop improvement is one of the drivers of crop production and extensive studies have evaluated the contributions of plant breeding to production enhancement in association with marketing and utilization (Douches et al., 1996). However, when we manage pests including insects, diseases, or nematodes, the limitations of biological and other control tactics have pushed producers to rely on the use of pesticides as we will discuss below (Mitkowski and Abawi, 2003; Ramirez et al., 2009; Maharijaya and Vosman, 2015).

In commercial potato, Solanum tuberosum L., the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), is well-known for rapidly evolving resistance to insecticides (Alyokhin et al., 2008; Schoville et al., 2018), which reinforces its status as one of the most important potato pests (Weber, 2003). Over 300 documented cases of insecticide resistance are listed in the literature coming from Asia, Europe, and North America (Whalon and Mota-Sanchez, 2017; Brevik et al., 2018a,b). Interestingly enough, populations of L. decemlineata do not respond equivalently to pesticides; some researchers argue that it may be due to evolutionary differences in how L. decemlineata interacts with potatoes within the landscape (Whitaker, 1994; Wierenga and Hollingworth, 1994; Crossley et al., 2019a,b). Others suggest a moderate variation at the nuclear loci level (Hawthorne, 2001; Izzo et al., 2018). Remarkably, in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington which together produce close to 56% of United States fresh and frozen potatoes in the market, L. decemlineata populations have largely remained susceptible to insecticides (Haegele and Wakeland, 1932; Johnston and Sandvol, 1986; Olson et al., 2000; Alyokhin et al., 2015; Crossley et al., 2018; Dively et al., 2020). According to Lynch and Walsh (1998), populations with lower genetic variance are expected to adapt more slowly, and L. decemlineata in the Northwestern United States exhibits lower genetic diversity than elsewhere which may explain its susceptibility to pesticides. In comparison, populations in other areas like east of the Rocky Mountains, L. decemlineata has historically developed pesticide resistance (Grafius, 1995; Grafius and Douches, 2008). Hence, the need to add novel tools in the pest management toolbox to help potato producers manage this pest problem remains and the availability of L. decemlineata potato resistant varieties could complement existing management practices.

Host Range and Distribution of Leptinotarsa decemlineata

Leptinotarsa decemlineata is largely considered a pest of Solanaceous crops (Foster, 1876). Solanum is a large and diverse genus, including important economic crops with a wide geographical range such as potato, tomato (S. lycopersicum L.), and eggplant (S. melongena L.) (Whalen, 1979). Hitchner et al. (2008) and Li et al. (2013) studied the host preference of L. decemlineata comparing potato to crops such as tomato or eggplant, observing a clear affinity for potatoes. Leptinotarsa decemlineata is widespread in North America feeding on several plant species already described above in addition to Solanaceous weeds such as S. angustifolium Miller, S. rostratum L., and S. eleagnifolium Cav., several species of nightshades (S. dulcamara L., S. sarrachoides L., including hairy nightshade (S. nitidibaccatum Bitter; a.k.a. S. sarrachoides Sendt or S. physalifolium Rusby), and horse nettle (S. carolinense L.) (Tower, 1906; Latheef and Harcourt, 1974; Hsiao, 1978, 1981; Hare, 1983, 1990; Hare and Kennedy, 1986; Horton et al., 1988; Jacques, 1988; Weber et al., 1995; Xu and Long, 1995; Mena-Covarrubias et al., 1996). Anecdotical observations that need further investigation suggest that Solanaceous weeds co-exist or overlap with cultivated potatoes in the Northwestern US; however, L. decemlineata has a strong preference for cultivated potatoes.

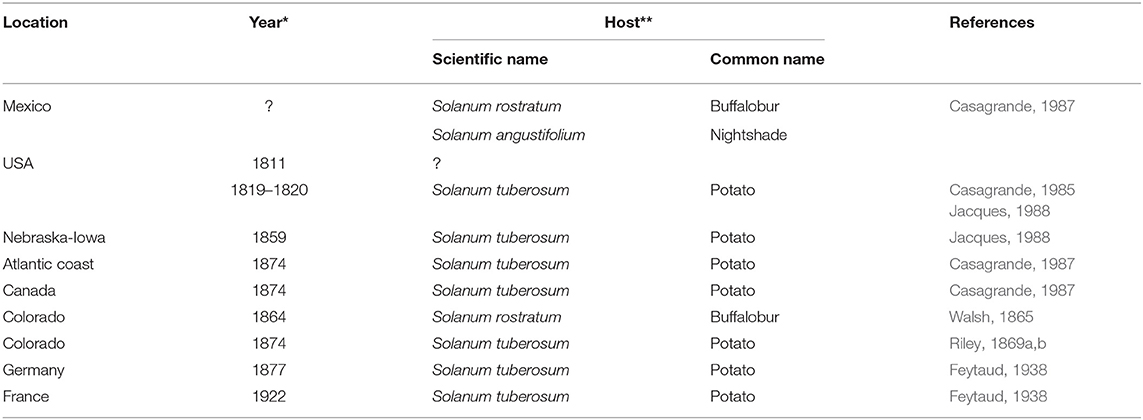

In the US, L. decemlineata was first associated with Solanaceous plants around 1859, when it was reported on S. rostratum in Omaha, Nebraska, near the Iowa border (Casagrande, 1985). By 1859, L. decemlineata was found on S. tuberosum (Walsh, 1866), and by 1874, L. decemlineata spread rapidly eastward reaching the Atlantic coast (Tower, 1906; Hsiao, 1978; Logan et al., 1987; Jacques, 1988; Alyokhin, 2009; Zhao et al., 2013; and Izzo et al., 2018). Member of the genus Leptinotarsa have been long known to feed on S. rostratum in central Mexico, suggesting Mexico as the center of distribution of L. decemlineata. Historically, as the Solanaceous weed geographical range expanded northward, so did L. decemlineata distribution (Table 1). Worldwide, by the end of the 20th century, L. decemlineata was well-established in Europe, Asia Minor, Iran, Central Asia including China (Jolivet, 1991; Weber, 2003; Alyokhin, 2009). In Europe, L. decemlineata became established near Bordeaux, France in 1922, and spread throughout the French potato production regions, although it went undetected until 1935 (Hurst, 1975). Hurst (1975) reported three invasions (1876, 1901, 1914) in Great Britain that were “aggressively” (chemically) controlled. Crossley et al. (2017) reported that currently in Europe there are two clades: a western clade (French, Spanish, and Italian) and an eastern one (Poland, Estonia, Finland, and Russia). This information suggests multiple arrivals of L. decemlineata in Europe but could also be explained by adaptation to regional environment/hosts or genetic drift within isolated populations. Moving to Asia, L. decemlineata populations reached western China by 1993 and now it can be found in several Chinese potato regions (Zhang et al., 2013).

Recently, Izzo et al. (2018) used mitochondrial DNA and nuclear loci to examine the origin of L. decemlineata lineages. Authors suggested a genetically heterogenous L. decemlineata population which may contribute with contemporary populations. Schoville et al. (2018) used L. decemlineata as a model species for agricultural pest genomics that provides a better understanding of the insect and its host information that can be used for future genetic and evolutionary studies.

Life History of Leptinotarsa decemlineata

Adults and larvae of L. decemlineata are voracious defoliators of S. tuberosum. Ferro et al. (1985) report that approximately 40 and 10 cm2 of potato leaves are consumed by larvae and adults during their lifetime, respectively. Once leaf tissue is gone, L. decemlineata begins feeding on stems and tubers (Weber and Ferro, 1993), before moving into the soil to overwinter.

Coupling insect-host relationships and abiotic factors, L. decemlineata can be found in a diverse range of climates (Grapputo et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014). Temperature and humidity during the spring are important for the survival of overwintering populations (Izzo et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014). Pelletier (1995) and Pelletier (1998) indicated that high temperatures thresholds for larvae, pupae, and adults are 49, 61, and 57°C, respectively. Mail and Salt (1933), Hurst (1975), Hiiesaar et al. (2006), Izzo et al. (2014), Li et al. (2014) reported lethal tempertures of −10 to −4°C. Moreover, overwintering survival can be as high as 90% in absence of snow cover (Gibson et al., 1925; Ushatinskaya, 1978; Hiiesaar et al., 2006; Huseth and Groves, 2013). Overwintering may be as short as 30 days (Capinera, 2001), although Biever and Chauvin (1990) observed that 16% of L. decemlineata populations could remain in diapause for 2–3 winters in Washington State, while Tauber and Tauber (2002) reported 2.3% of L. decemlineata populations overwintering in New York after a 10-year study. After emerging in the spring, L. decemlineata disperse by walking or flying (Voss and Ferro, 1990; Follett et al., 1996; Noronha and Cloutier, 1999; Boiteau et al., 2003). Surviving overwintering adults feed, reproduce, lay eggs, and die.

The life cycle consists of an egg stage, four larval stages, pupal, and adult stages. Adults are polygamous, performing multiple copulations (Alyokhin et al., 2015). Depending on temperature, females deposit masses of 20–60 yellowish-orange eggs (Isely, 1935; Hare, 1983, 1990). Each female may lay up to 800 eggs during her lifetime (Brown et al., 1980; Ferro et al., 1985). Eggs are attached to plant tissue, although recently we have observed that certain potato varieties inhibit this process. All eggs hatch simultaneously, and larvae immediately feed until reaching the pupal stage (Hazzard et al., 1991) (Figure 1). Pupation occurs in the soil (Hare, 1983), and adults emerge 5–7 days later, depending on temperature. They then start a new cycle of dispersing, feeding, mating, and egg laying. Life cycle last 30 days depending on temperatures. Depending on geographical location and climatic conditions, 2–3 generations per year are completed (Walgenbach and Wyman, 1984; Ferro et al., 1985; Xu and Long, 1997).

Current Management Practices

Core management of L. decemlineata focuses on chemical, cultural, and biological control.

Chemical control has been largely studied (Grafius, 1995, 1997; Wustman and Carnegie, 2000; Zabel et al., 2002; Stankovik et al., 2004; Alyokhin et al., 2008; Grafius and Douches, 2008; Alyokhin, 2009; Sladam et al., 2012; Szendrei et al., 2012; Piiroinen et al., 2014; Clements et al., 2016). Although insecticides are effective, resistance has been an issue in many populations (Casagrande, 1987; Kennedy and Farrar, 1987; Helm et al., 1990; Grapputo et al., 2005; Alyokhin et al., 2006, 2008; Szendrei et al., 2012; Kaplanoglu et al., 2017; Clements et al., 2018; Crossley et al., 2018), while other populations have largely remained susceptible to insecticides (Haegele and Wakeland, 1932; Johnston and Sandvol, 1986; Olson et al., 2000; Alyokhin et al., 2015; Crossley et al., 2018; Dively et al., 2020).

Crop rotation (Lashomb and Ng, 1984; Weisz et al., 1994; Speese Iii and Sterrett, 1998; Sexson and Wyman, 2005; Sexson et al., 2005; Huseth et al., 2012), the use of plastic-lined trenches (Boiteau and Vernon, 2001), straw mulch (Stoner et al., 1996; Stoner, 1997), trap cropping (Hunt and Whitfield, 1996; Hoy et al., 2000), thermal control (Rifai et al., 2004), and electromagnetic control (Colpitts et al., 1992) are a few examples of cultural, mechanical and physical control options. Interestingly, combining the dispersal behavior of L. decemlineata, which despite their ability to fly mainly disperse by walking, and the rotation of potato fields with non-host crops can reduce adult abundance (Follett et al., 1996; Hough-Goldstein and Whalen, 1996; Sexson and Wyman, 2005). More recently, Crossley et al. (2017, 2019a,b) discussed the effect of land cover composition influencing the efficacy of crop rotation such as higher wheat land in the Northwest and forest field edges in the Central Sands of the US. These studies suggest the importance of land coverage in L. decemlineata movement and distribution and further studies are currently underway in the Northwest.

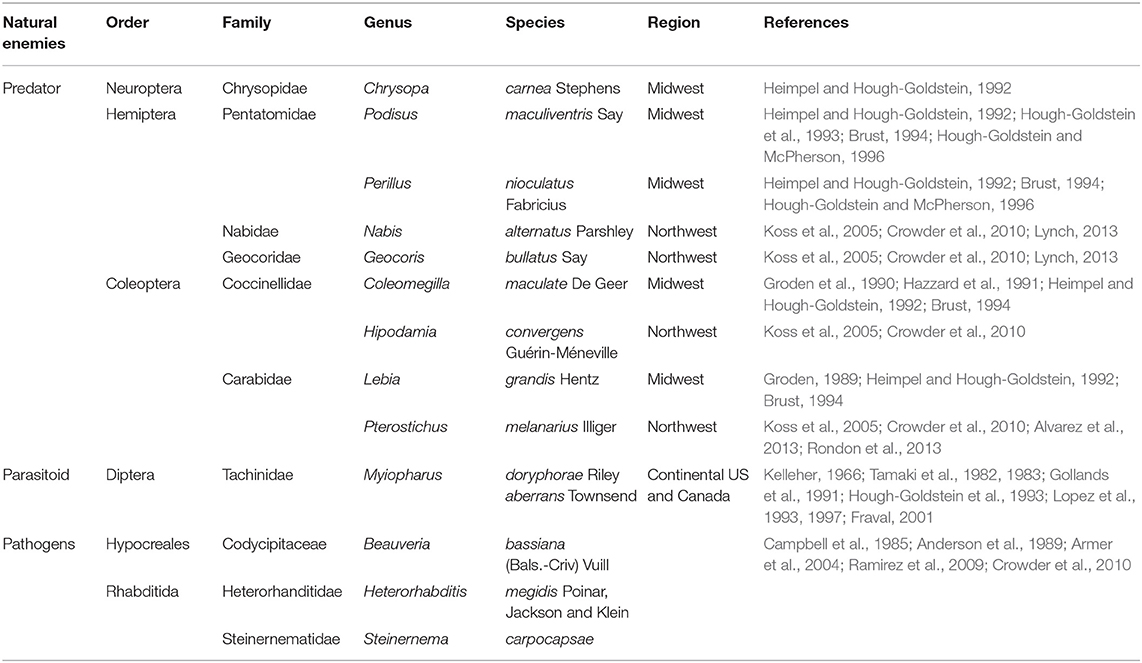

Some field studies suggest that natural enemies have minimal effect (Chang and Snyder, 2004; Koss et al., 2004, 2005). However, predators such as the Carabidae Pterostichus melanarius Illiger (Alvarez et al., 2013, Rondon et al., 2013) and the Chrysopidae Chrysoperla carnea Stephens (Sablon et al., 2013) were found feeding on L. decemlineata. Two Tachinidae parasitic flies, Myiopharus aberrans L. and M. doryphorae Riley (Figure 2) were found to parasitize L. decemlineata with relative success (Kelleher, 1966; Tamaki et al., 1982, 1983; Gollands et al., 1991; Lopez et al., 1993, 1997). Several species of Bacillus including B. pumilus L., B. cereus Frankland and Frankland, B. megaterium de Bary (Ertürk et al., 2008), and B. thuringiensis Berliner (Walker et al., 2003; Whalon and Wingerd, 2003; Gassmann et al., 2009; Wraight and Ramos, 2015) were found to cause L. decemlineata mortality. Although the real impact of natural enemies controlling L. decemlineata is unknown, studies by Snyder and Clevenger (2004) and Lynch (2013) exploring the consumption by two generalist predators in potatoes using molecular gut content analysis and behavioral studies could provide new insights into host selection and role of microbiota into L. decemlineata fitness and sucess. For additional information about natural enemies see Table 2.

Host Selection by L. decemlineata: The Need for “Wild Relatives”

In herbivores, chemical signals have an important role in host plant selection (Fürstenberg-Hägg et al., 2013; Sablon et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2019). Volatiles like trans-2-hexen-1-ol-hexanol, cis 3-hexen-1-ol, trans-2 hexenal, and linalool, methyl salicylate, and z-3-hexenyl acetate have been reported as key cues for L. decemlineata (Visser et al., 1979; Dickens, 2000, 2002; Martel et al., 2005). Moreover, damaged leaves potentially produced and releases additional chemicals that may attract L. decemlineata (Boiteau et al., 2003). Stimulants, or essential dietary components produced by potato plants, released by potato plants such as sterols (e.g., cholesterol, b-sitosterol, stigmasterol) and sucrose, melezitose, glucose and fructose, amino acids, phospholipids, and chlorogenic acid (Hsiao, 1969) act as feeding stimulants (Szafranek et al., 2008); conversely, flowers of tansy (Tanacetum vulgare L.) which contain high levels of camphor and umbellulone, act as feeding deterrents (Yencho et al., 1994, 1996, 2000; Pelletier and Dutheil, 2006; Maharijaya and Vosman, 2015). Based on this information, manipulation of chemical cues which may affect “normal” behavioral choices of L. decemlineata potentially could be deployed via plant breeding to regulate feeding behavior and manipulate their control. A summary of current efforts will be discussed below.

Plant Breeding

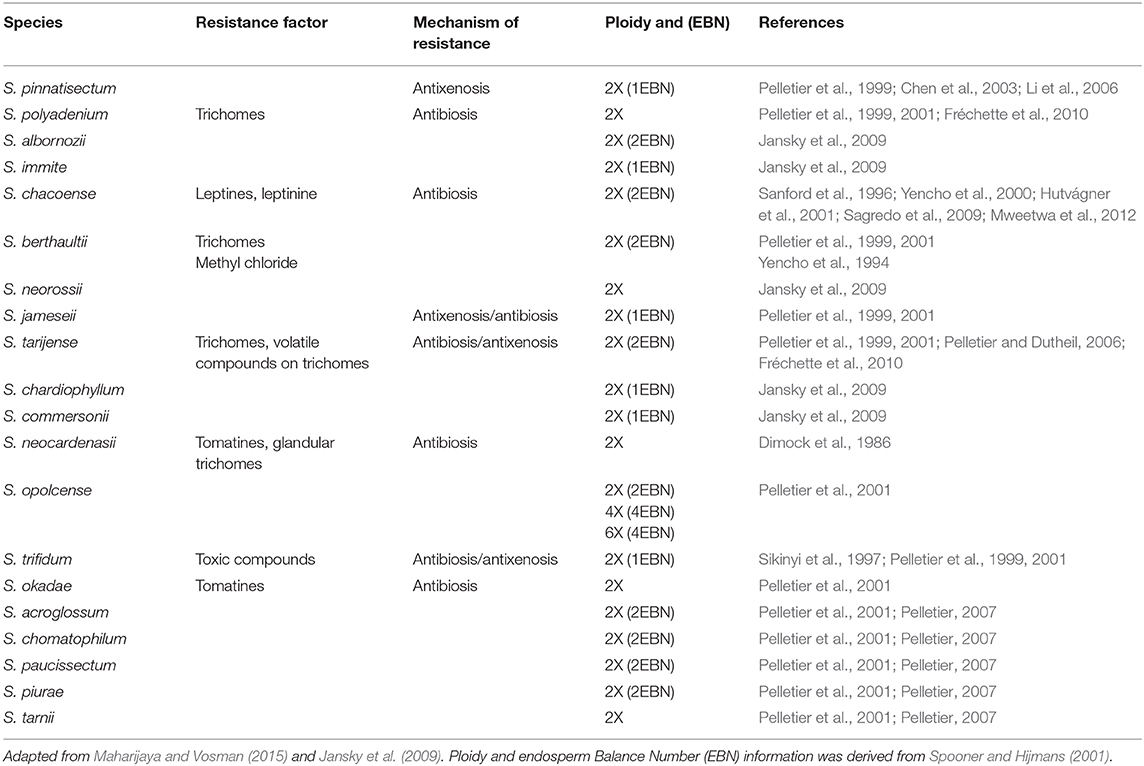

Plant breeding is a powerful tool that can contribute to pest management. The notion of utilizing variation in L. decemlineata host preference between potato varieties (Torka, 1950; Horton et al., 1997; Metspalu et al., 2000) for breeding has been considered since the late 19th century (Saunders and Reed, 1871; Chavez et al., 1988). However, the potential to improve insect resistance by breeding within domesticated potato alone is limited due to potato narrows genetic base (Hardigan et al., 2017; Jansky and Spooner, 2018). Fortunately, the germplasm pool of approximately 107 Solanum spp. related to potato comprises one of the deepest and most accessible sources of pest resistant alleles among all major crops (Spooner and Bamberg, 1994; Jansky et al., 2013; Spooner et al., 2014; Bethke et al., 2017) (Table 3). Systematic field screens aimed at identifying crop wild relatives that exhibit L. decemlineata resistance have been performed on large scales by several investigators since the early 1930s (Torka, 1950), with the efforts of Carter (1987), Flanders et al. (1992), and Jansky et al. (2009) all making major contributions to our knowledge on this topic at a species and accession level (Pelletier et al., 2011).

Foliar production of phytochemical insect toxins (often glycoalkaloids) is one major mechanism of L. decemlineata resistance found in potato wild relatives (Buhr et al., 1958; Andersson, 1999). Total foliar concentration of α-solanine and α-chaconine, the primary glycoalkaloids found in domesticated potato, are poor predictors of plant L. decemlineata resistance (Barbour and Kennedy, 1991; Flanders et al., 1992; Metspalu et al., 2000; Dinkins et al., 2008; Navarre et al., 2016) likely because they are not accumulated in high enough concentrations to inhibit insect feeding (Sinden et al., 1980; Friedman et al., 1997). Instead, insect resistance has often been linked with the production by lower abundance glycoalkaloids found in wild potato relatives (Tingey, 1984; Kowalski et al., 1999, 2000) that exhibit structural differences in their nitrogen containing 27-carbon cholestane aglycone backbone and variation of the hydrophilic carbohydrate side chain attached to 3-OH position of the aglycone molecule (Friedman et al., 1997; Milner et al., 2011). In total, more than 90 structurally unique steroidal alkaloids have been identified from roughly 350 wild potato species (Friedman et al., 1997; Pelletier et al., 2001; Shakya and Navarre, 2008; Milner et al., 2011; Mweetwa et al., 2012; Tai et al., 2014).

The significance of leptine class glycoalkaloids as a feeding deterrent has long been recognized as a potential source of L. decemlineata resistance (Sinden et al., 1986a,b). Leptines I and II are triose glycosides derived from a solanidane precursor which are differentially acetylated to contain either an acetoxy or hydroxyl moiety the C23 position of the aglycone backbone (Friedman et al., 1997; Ginzberg et al., 2009; Milner et al., 2011; Pelletier et al., 2011). Leptine molecules are only found in a few accessions of S. chacoense and are perceived to deter insect feeding through cholinesterase inhibition and cell membrane disruption within the insect (Sinden et al., 1986a, 1988; Wierenga and Hollingworth, 1994; Sanford et al., 1997; Rangarajan et al., 2000; Yencho et al., 2000; Lorenzen et al., 2001). Introgression of leptine biosynthesis into domesticated potato is an attractive breeding objective as leptines are only produced in foliar tissues and do not accumulate within tubers (Sinden et al., 1986a; Sanford et al., 1996; Mweetwa et al., 2012).

Breeding work on this trait has largely focused on mapping of resistance found in the diploid S. chacoense accession USDA8380-1 (Sinden et al., 1986a; Ronning et al., 1998; Hutvágner et al., 2001; Boluarte-Medina et al., 2003; Kaiser et al., 2020) and a few tetraploid S. tuberosum introgression lines (Lorenzen et al., 2001). Leptine content segregates as a multi-locus, additive trait in both diploid and tetraploid backgrounds. Contemporary studies that leverage the power of molecular genotyping tools in biparental linkage mapping populations have identified major QTL associated with leptine abundance on chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 (Ronning et al., 1998; Hutvágner et al., 2001; Boluarte-Medina et al., 2003; Manrique-Carpintero et al., 2014; Kaiser et al., 2020). Somewhat surprisingly the proportion of variance attributed to major QTL located on chromosome 1 (Ronning et al., 1999; Hutvágner et al., 2001; Boluarte-Medina et al., 2003; Manrique-Carpintero et al., 2014) and chromosome 2 (Sagredo et al., 2009; Kaiser et al., 2020) have varied by study. This may be attributed to the structure of the linkage mapping population or due to genetic epistasis between genomic backgrounds.

Other glycoalkaloid compounds are also known to play prominent roles in plant defense against L. decemlineata, but less is understood regarding inheritance of pathway components at a molecular genetics level. Dehydrocommersonine and solanidenol-chacotriose concentration has been demonstrated to play opposing roles in L. decemlineata resistance when inherited from S. oplocense (Tai et al., 2015; Paudel et al., 2019). Selective genotyping of a S. oplocense × S. tuberosum F1 population have mapped a QTL associated with production of these molecules to a location on chromosome 1 (Paudel et al., 2019) also identified in a S. berthaultii × S. tuberosum F1 population by Yencho et al. (1998). Correlative evidence supporting association between L. decemlineata resistance of wild species and other glycoalkaloid molecules found in potato is intriguing but less direct in so far as proven causation.

The structure and abundance of glandular trichomes are another biological characteristic that contributes to insect resistance in Solanum spp. (Gibson, 1971; Gibson and Turner, 1977; Tingey and Gibson, 1978; Tingey and Sinden, 1982; Kennedy and Sorenson, 1985; Dimock et al., 1986; Gregory et al., 1986; Lapointe and Tingey, 1986; Carter et al., 1989; Tingey, 1991; Pelletier et al., 1999; Pelletier and Dutheil, 2006; Tian et al., 2012). This mechanism of resistance reduces the mobility of insects (both adults and larvae) on the leaf surface through trichome secretion (Gibson, 1971; Gibson and Turner, 1977; Tingey and Gibson, 1978; Dimock and Tingey, 1987) or discharge of metabolites after mechanical disruption of trichomes (Tingey and Laubengayer, 1981; Ryan et al., 1982). Trichome-mediated resistance has been found in several wild potato species (Flanders et al., 1992; Pelletier et al., 1999) including S. neocardenasii (Dimock et al., 1986), S. polyadenium (Tingey and Gibson, 1978), S. tarijense (Gibson, 1971) but a majority of our knowledge is derived from experimentation focused on S. berthaultii accessions and introgression lines (Wright et al., 1985; Groden and Casagrande, 1986; Dimock and Tingey, 1987; Neal et al., 1989; Bonierbale et al., 1994; Yencho et al., 1998).

Trichome-associated resistance to L. decemlineata in S. berthaultii is conditioned by the presence of two types of trichomes on leaves and stems of the plant. Type A trichomes are the smaller of the two, exhibiting length between 120 and 210 μm and possess a tetralobulate head with a diameter of 50 to 70 μm (Gregory et al., 1986). When ruptured by mechanical disruption, Type A trichomes release polyphenol oxidase enzyme (PPO) which rapidly polymerizes the substrates contained within the trichome head (Ryan et al., 1982; Kowalski et al., 1992). The accretion of hardened, polymerized exudate adheres to the tarsi and mouthparts of insects which reduces their mobility and can trap smaller insects, like aphids, to the leaf surface (Gibson and Turner, 1977; Tingey and Gibson, 1978). Type B trichomes are much larger (600–950 μm) and secrete a viscous fluid droplet on the tip of each stalk (diameter 45 μm). Exudates from type B trichomes contain fatty acid esters of sucrose, that vary by the number (and position) of linkages and fatty acid chain length across accessions (King et al., 1986, 1987a,b). Solvent removal of exudates or mechanical removal of trichomes does not attenuate the repellent effect of S. berthaultii leaves in choice assays but leads to increased feeding and decreased mortality of larvae relative to S. tuberosum (Dimock and Tingey, 1988; Neal et al., 1989; Yencho and Tingey, 1994). Evidence from Neal et al. (1989) suggests that type A trichomes are a fundamental requirement for L. decemlineata resistance but the presence of type B trichomes may have a synergistic effect; whereas Yencho and Tingey (1994) concluded that both mechanical and chemical mechanisms likely contribute to L. decemlineata resistance in S. berthaultii.

From a breeding perspective, trichome mediated insect resistance is attractive as it may provide durable resistance (França and Tingey, 1994) to multiple insect species simultaneously (Gregory et al., 1986). At the genetic level, trichome mediated resistance can be introgressed into domesticated potato (Mehlenbacher et al., 1983; Wright et al., 1985; Plaisted et al., 1992), and behaves as a quantitatively inherited trait (Mehlenbacher et al., 1983). Introgression of resistance from S. berthaultii has resulted in the release of several potato clones from the breeding program at Cornell University NYL 235-4, Q174-2, and NYL 123 (Plaisted et al., 1992; de Souza et al., 2006; Malakar-Kuenen and Tingey, 2006). Quantitative genetic studies support an additive, multigene inheritance model, where L. decemlineata resistance is associated with trichome characteristics including density and chemical composition (Bonierbale et al., 1994; Yencho et al., 1996).

Complimentary studies aimed at characterizing the inheritance of trichome related traits and L. decemlineata resistance in reciprocal S. berthaultii × S. tuberosum hybrid backcross populations indicate that traits exhibits some shared and some unique features to their genetic architecture (Bonierbale et al., 1994; Yencho et al., 1996). Inheritance of insect resistance is clearly a multi-locus trait that exhibit differences in penetrance based upon how trait values are skewed differentially between backcross parent (Bonierbale et al., 1994; Yencho et al., 1996). The number of type A trichomes is largely controlled by the inheritance of S. berthaultii alleles on chromosome 6 (dominant) and 10 (recessive), which combine to describe up to 63% of variation in a S. berthaultii backcross population (Bonierbale et al., 1994). PPO concentration is also a multi-locus trait with QTL on chromosomes 2, 5, 8, and 11 potentially contributed to enzyme abundance (Bonierbale et al., 1994). Inheritance of type B trichomes is clearly recessive as type B trichomes are not observed in S. tuberosum backcross populations derived from S. berthaultii × S. tuberosum hybrids (Bonierbale et al., 1994). The presence of sucrose ester droplets and abundance of type B trichomes are controlled by a major QTL located on chromosome 5 and additional QTL located on chromosome 1, 2, and 4 (Bonierbale et al., 1994). These plant characteristics seem to directly relate with L. decemlineata feeding and reproductive presence in backcross populations, which are influenced by no fewer than four QTL located on chromosomes 1, 5, 8, and 10 (Yencho et al., 1996). When the results of both Bonierbale et al. (1994) and Yencho et al. (1996) were overlaid, L. decemlineata resistance as measured by Yencho et al. (1996) exhibited QTL located on 1, 5, 10 in a S. berthaultii backcross population whereas QTL associated with type A trichome characteristics (Bonierbale et al., 1994) were associated with QTL 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 11 in the same population. Whereas, in a S. tuberosum backcross population fewer QTL were identified and the only major overlapping QTL was associated with PPO activity on chromosome 8 (Yencho et al., 1996). Largely due to the thoroughness of these investigations (Bonierbale et al., 1994; Yencho et al., 1996), it is suspected that chemical resistance also may play a role due to segregation of glycolalkaloid content associated with the S. berthaultii background (Yencho et al., 1998).

Although great strides have been made toward the identification, introgression, and genetic mapping of L. decemlineata resistance mechanisms into breeding lines, there is still much work to be done. Currently no L. decemlineata resistant cultivars have been widely accepted and planted on large acreage (Grafius and Douches, 2008). Linkage mapping is an indispensable tool for mapping quantitative traits, but other complimentary methods including genome-wide association studies (Sharma et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019) or quantitative evolutionary genetic methods (Hardigan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018) can have a great impact identifying major allelic variants within populations/species groups. Comparative genomics with other Solanum spp. has long been perceived as a method to leverage our knowledge of biochemical genes across species (Cárdenas et al., 2015) and has been used to identify shared components responsible for glycoalkaloid biosynthesis (Itkin et al., 2011; Cárdenas et al., 2016).

Little is understood about the mechanisms of resistance present in other species outside of S. chacoense and S. berthaultii or the genetics underlying these traits. This is particularly apparent for germplasm from the endosperm balance number 1 clade in potato (Carter, 1987; Flanders et al., 1992; Jansky et al., 2009; Pelletier et al., 2011). Consistently high levels of resistance in field screens but the mechanisms responsible of this quality are less tractable to breeders focused on cultivated S. tuberosum due to crossing barriers. Bridge crosses (Yermishin et al., 2014) and somatic hybridization (Jansky et al., 1999) are tools that researchers have used to introduce these traits into backgrounds compatible with cultivated potato (Jansky, 2006).

Transgenic potatoes thru genetic engineering has focus on pest resistance (Michaud et al., 1993; Alyokhin and Ferro, 1999; Grafius and Douches, 2008; Šmid et al., 2013). In 2013, Cooper et al. (2004) combined genetic engineering and traditional breeding testing feeding, biomass accumulation, and mortality on three populations of L. decemlineata including a Bt cry 3A-selected population which apparently conferred elevated resistance in potatoes. Mi et al. (2015) also reported excellent results expressing cry3A genes. However, L. decemlineata adapts quickly (Zhu-Salzman and Zeng, 2015). Jin et al. (2015) developed large-scale tests of natural refuge for delaying cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera Hüber) resistance to transgenic Bt crops that could be used for L. decemlineata. Li et al. (2017) also studied the function and effectiveness of natural refuge in Insecticide Resistance Management strategies for Bt crops but more studies are still needed. Ma et al. (2020) reviewed the benefits of RNA interference (RNAi) tested for L. decemlineata where target genes, efficiency, and factors affecting RNAi efficiency against this pest were discussed.

Current Breeding Efforts: Northwest Case Study

Maharijaya and Vosman (2015) suggest that breeding potato for resistance against L. decemlineata will benefit from information obtained using new, higher throughput screening methods. This has proven true in row crops, particularly as it relates to quantitative genetics and marker assisted selection. Improvement of crops using quantitative genetics requires identifying biological association between the plant phenotype of interest (insect resistance) and genetic or biochemical markers that can be used to select for that trait (Bernardo, 2019; Paudel et al., 2019).

Oftentimes the number of measurements required for genetic mapping, particularly in field studies, substantially outnumber the resources that can be allocated to perform this task by any single research group. In such cases, collaborative efforts between domain experts (entomology, breeding, remote sensing, analytical chemistry etc.) can be hugely beneficial. Small scale field studies can help us assess our ability to evaluate insect preference. Such information is critical for understanding both the insect pressure at a given trial location and how the aggressiveness of foliar consumption varies between field seasons.

Human index scoring of insect mediated defoliation is a relatively quick and accurate measurement, however as the clone number within a trial and number of field sites increases, our ability to accurately record this data becomes limiting. Data collection using multispectral sensors fixed to sUAS have been proposed as a scalable method to estimate insect damage in numerous crops (Puig et al., 2015; Mahlein, 2016; Vanegas et al., 2018) including potato (Hunt et al., 2016; Hunt and Rondon, 2017; Théau et al., 2020). When combined with ground truth measurements, multispectral data collected using sUAS can provide high-resolution, quantitative data on plant performance on larger scales and at greater frequency than could possibly achieved by human observation alone (White et al., 2012). This sort of standardized measurement is particularly attractive for multi-location field trials where scoring of insect mediated defoliation must be measured by members of different research groups and with high spatiotemporal resolution. Unfortunately, spectral measurements can be influenced by many confounding factors including, plant genotype, plant developmental stage, management practices within the trial, and environmental variables across time (White et al., 2012; Hunt et al., 2016; Khot et al., 2016; Chivasa et al., 2020; Théau et al., 2020). So, more research is needed to ascertain how reliable these measurements are at measuring insect damage specifically, across locations and field seasons.

We believe that multiscale measurement strategies, that begins with field screening of segregating populations or wild germplasm to narrow research focus can be useful and are an efficient use of resources. Identifying particularly resistant or susceptible germplasm, will help researchers focus on studying the mechanisms of resistance in much greater detail though application of some of the more difficult, expensive, and time demanding assays described in this article.

Author Contributions

SR and MF planned the idea of the review and wrote entire manuscript. SR designed the framework of the review. AT contributed with the writing and editing and providing information for Table 3. TO provided editing and organized literature citation. GS contributed on editing and organizing of literature citation. All authors contributed with the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported but the Oregon State University Irrigated Agricultural Entomology program, Agricultural Research Foundations, and USDA-ARF program funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alvarez, J. M., Srinivasan, R., and Cervantes, F. A. (2013). Occurrence of the carabid beetle, Pterostichus melanarius (Illiger), in potato ecosystems of Idaho and its predatory potential on the Colorado potato beetle and aphids. Am. J. Potato Res. 90, 83–92. doi: 10.1007/s12230-012-9279-7

Alyokhin, A. (2009). Colorado potato beetle: management on potatoes, current challenges and future prospects. Fruit. Veg. Cereal Sci. Biotech. 3, 10–19.

Alyokhin, A., Baker, M., Mota-Sanchez, D., Dively, G., and Grafius, E. (2008). Colorado potato beetle resistance to insecticides. Am. J. Potato Res. 85, 395–413. doi: 10.1007/s12230-008-9052-0

Alyokhin, A., Dively, G., Patterson, M., Mahoney, M., Rogers, D., and Wollam, J. (2006). Susceptibility of imidacloprid-resistant Colorado potato beetle s to non-neonicotinoid insecticides in the laboratory and field trials. Am. J. Potato Res. 83, 485–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02883509

Alyokhin, A., Mota-Sanchez, D., Baker, M., Snyder, W. E., Menasha, S., Whalon, M., et al. (2015). The red queen in a potato field: integrated pest management versus chemical dependency in Colorado potato beetle control. Pest Manag. Sci. 71, 343–356. doi: 10.1002/ps.3826

Alyokhin, A. V., and Ferro, D. N. (1999). Modifications in dispersal and oviposition of Bt-resistant and Bt-susceptible Colorado potato beetles as a result of exposure to Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. tenebrionis Cry3A toxin. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 90, 93–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.1999.00426.x

Anderson, T. E., Hajek, A. E., Roberts, D. W., Preisler, H. K., and Robertson, L. (1989). Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): effects of combinations of Beauveria bassiana with insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol. 82, 83–89. doi: 10.1093/jee/82.1.83

Andersson, C. (1999). “Glycoalkaloids in tomatoes, eggplants, pepper and two Solanum species growing wild in the Nordic countries,” in Tema Nord. Vol. 599. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Armer, C. A., Berry, R. E., Reed, G. L., and Jepsen, S. J. (2004). Colorado potato beetle control by application of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis marelata and potato plant alkaloid manipulation. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 111, 47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-8703.2004.00152.x

Barbour, J. D., and Kennedy, G. G. (1991). Role of steroidal glycoalkaloid α-tomatine in host-plant resistance of tomato to Colorado potato beetle. J. Chem. Ecol. 17, 989–1005. doi: 10.1007/BF01395604

Bernardo, R. N. (2019). Breeding for Quantitative Traits in Plants. 3rd Edn. Woodbury, MN: Stemma Press.

Bethke, P. C., Halterman, D. A., and Jansky, S. (2017). Are we getting better at using wild potato species in light of new tools? Crop Sci. 57, 1241–1258. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2016.10.0889

Biever, K. D., and Chauvin, R. L. (1990). Prolonged dormancy in a Pacific Northwest population of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Can. Entomol. 122, 175–177. doi: 10.4039/Ent122175-1

Boiteau, G., Alyokhin, A., and Ferro, D. N. (2003). The Colorado potato beetle in movement. Can. Entomol. 135, 1–22. doi: 10.4039/n02-008

Boiteau, G. A., and Vernon, R. S. (2001). “Physical barrier for the control of insect pests,” in Physical Control Methods in Plant Protecion, eds C. Vincent, B. Panneton, and F. Fleurat-Lessard (Berlin: Springer), 224–227.

Boluarte-Medina, T., Fogelman, E., Chani, E., Miller, A., Levin, I., Levy, D., et al. (2003). Identification of molecular markers associated with leptine in reciprocal backcross families of diploid potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106, 1533–1533. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1288-y

Bonierbale, M. W., Plaisted, R. L., Pineda, O., and Tanksley, S. D. (1994). QTL analysis of trichome-mediated insect resistance in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 87, 973–987. doi: 10.1007/BF00225792

Brevik, K., Lindström, L., McKay, S. D., and Chen, Y. H. (2018a). Transgenerational effects of insecticides - implications for rapid pest evolution in agroecosystems. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 26, 34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.12.007

Brevik, K., Schoville, S. D., Mota-Sanchez, D., and Chen, Y. H. (2018b). Pesticide durability and the evolution of resistance: a novel application of survival analysis. Pest Manag. Sci. 74, 1953–1963. doi: 10.1002/ps.4899

Brown, J. J., Jermy, T., and Butt, B. A. (1980). The influence of an alternate host plant on the fecundity of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 73, 197–199. doi: 10.1093/aesa/73.2.197

Brust, G. E. (1994). Natural enemies in straw-mulch reduce Colorado potato beetle populations and damage in potato. Biol. Control. 4, 163–169. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1994.1026

Buhr, H., Toball, R., and Schreiber, K. (1958). Die wirkung von einigen pflanzlichen sonderstoffen, insbesondere von alkaloiden, auf die entwicklung der larven des kartoffelkafers (Leptinotarsa decemlineata SAY). Entomol. Exp. Appl. 3, 209–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1958.tb00025.x

Campbell, R. K., Anderson, T. E., Semel, M., and Roberts, D. W. (1985). Management of the Colorado potato beetle using the entomogenous fungus Beauveria bassiana. Am. Potato J. 62, 29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02871297

Cárdenas, P. D., Sonawane, P. D., Heinig, U., Bocobza, S. E., Burdman, S., and Aharoni, A. (2015). The bitter side of the nightshades: genomics drives discovery in Solanaceae steroidal alkaloid metabolism. Phytochemistry 113, 24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.12.010

Cárdenas, P. D., Sonawane, P. D., Pollier, J., Vanden Bossche, R., Dewangan, V., Weithorn, E., et al. (2016). GAME9 regulates the biosynthesis of steroidal alkaloids and upstream isoprenoids in the plant mevalonate pathway. Nat. Commun. 7:10654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10654

Carter, C. D. (1987). Screening Solanum germplasm for resistance to Colorado potato beetle. Am. Potato J. 64, 563–568. doi: 10.1007/BF02853756

Carter, C. D., Gianfagna, T. J., and Scalis, J. N. (1989). Sesquiterpenes in glandular trichomes of a wild tomato species and toxicity to the Colorado potato beetle. J. Agri. Food Chem. 37, 1425–1428. doi: 10.1021/jf00089a048

Casagrande, R. A. (1985). The “Iowa” potato beetle, its discovery and spread to potatoes. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 31, 27–29. doi: 10.1093/besa/31.2.27

Casagrande, R. A. (1987). The Colorado potato beetle: 125 years of mismanagement. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 33, 142–150. doi: 10.1093/besa/33.3.142

Chang, G. C., and Snyder, W. E. (2004). The relationship between predator density, community composition, and field predation of Colorado potato beetle eggs. Biol. Control. 31, 453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.07.009

Chavez, R., Schmiediche, P. E., Jackson, M. T., and Raman, K. V. (1988). The breeding potential of wild potato species resistant to the potato tuber moth Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller). Euphytica 39, 123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00039864

Chen, Q., Kawchuk, L. M., Lynch, D. R., Goettel, M. S., and Fujimoto, D. K. (2003). Identification of late blight, Colorado potato beetle, and blackleg resistance in three Mexican and two South American wild 2x (1EBN) Solanum species. Am. J. Potato Res. 80, 9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02854552

Chivasa, W., Mutanga, O., and Biradar, C. (2020). UAV-based multispectral phenotyping for disease resistance to accelerate crop improvement under changing climate conditions. Remote Sens. 12:2445. doi: 10.3390/rs12152445

Clements, J., Sanchez-Sedillo, B., Bradfield, C. A., and Groves, R. L. (2018). Transcriptomic analysis reveals similarities in genetic activation of detoxification mechanisms resulting from imidacloprid and chlorothalonil exposure. PLoS ONE 13, 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205881

Clements, J., Schoville, S., Peterson, N., Lan, Q., and Groves, R. L. (2016). Characterizing molecular mechanisms of imidacloprid resistance in select populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata in the Central Sands region of Wisconsin. PLoS ONE 11, 1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147844

Colpitts, B., Pelletier, Y., and Cogswell, S. (1992). Complex permitivity measurements of the Colorado potato beetle using coaxial probe thecnique. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Enery 27, 175–182. doi: 10.1080/08327823.1992.11688187

Cooper, S. G., Douches, D. S., and Grafius, E. J. (2004). Combining genetic engineering and traditional breeding to provide elevated resistance in potatoes to Colorado potato beetle. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 112, 37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-8703.2004.00182.x

Crossley, M. S., Chen, Y. H., Groves, R. L., and Schoville, S. D. (2017). Landscape genomics of Colorado potato beetle provides evidence of polygenic adaptation to insecticides. Mol. Ecol. 26, 6284–6300. doi: 10.1111/mec.14339

Crossley, M. S., Rondon, S. I., and Schoville, S. D. (2018). A comparison of resistance to imidacloprid in Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) populations collected in the Northwest and Midwest U.S. Am. J. Potato Res. 95, 495–503. doi: 10.1007/s12230-018-9654-0

Crossley, M. S., Rondon, S. I., and Schoville, S. D. (2019a). Patterns of genetic differentiation in Colorado potato beetle correlate with contemporary, not historic, potato land cover. Evol. Appl. 12, 804–814. doi: 10.1111/eva.12757

Crossley, M. S., Rondon, S. I., and Schoville, S. D. (2019b). Effects of contemporary agricultural land cover on Colorado potato beetle genetic differentiation in the Columbia Basin and Central Sands. Ecol. Evol. 9, 9385–9394. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5489

Crowder, D. W., Northfield, T. D., Strand, M. R., and Snyder, W. E. (2010). Organic agriculture promotes evenness and natural pest control. Nature 466, 109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature09183

de Souza, V. Q., Pereira, A. S., Silva, G. O., and Carvalho, F. I. F. (2006). Correlations between insect resistance and horticultural traits in potatoes. Crop. Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 6, 278–284. doi: 10.12702/1984-7033.v06n04a04

Dickens, J. C. (2000). Oreintation of Colorado potato beetle to natural and synthetic blends of volatiles emited by potato plants. Agric. For. Entomol. 2, 167–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-9563.2000.00065.x

Dickens, J. C. (2002). Behavioral responses of larvae of Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata to host plant volatile blends atractive to adults. Agrci. For. Entomol. 4, 309–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-9563.2002.00153.x

Dimock, M. B., Lapointe, S. L., and Tingey, W. M. (1986). Solanum neocardenasii: a new source of potato resistance to the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 79, 1269–1275. doi: 10.1093/jee/79.5.1269

Dimock, M. B., and Tingey, W. M. (1987). Mechanical interaction between larvae of the Colorado potato beetle and glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii Hawkes. Am. Potato J. 64, 507–515. doi: 10.1007/BF02853718

Dimock, M. B., and Tingey, W. M. (1988). Host acceptance behaviour of Colorado potato beetle larvae influenced by potato glandular trichomes. Physiol. Entomol. 13, 399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1988.tb01123.x

Dinkins, C. L. P., Peterson, R. K., Gibson, J. E., Hu, Q., and Weaver, D. K. (2008). Glycoalkaloid responses of potato to Colorado potato beetle defoliation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46, 2832–2836. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.023

Dively, G. P., Crossley, M. S., Schoville, S. D., Steinhauer, N., and Hawthorne, D. J. (2020). Regional differences in gene regulation may underlie patterns of sensitivity to novel insecticides in Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Pest Manag. Sci. 76, 4278–4285. doi: 10.1002/ps.5992

Douches, D. S., Mass, D., Jastrzebski, and Chase, R. W. (1996). Assessment of potato breeding progress in the USA over the last century. Crop Sci. 36, 1544–1552. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1996.0011183X003600060024x

Ertürk, O., Yaman, M., and Aslam, I. (2008). Effects of four Bacillus spp. of soil origin on the Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say). Entomol. Res. 38, 135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5967.2008.00150.x

Everson, R. E., and Gollin, D. (2002). Crop Variety Improvement and Its Effect on Productivity. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing.

Ferro, D. N., Logan, J. A., Vos, R. H., and Elkinston, J. S. (1985). Colorado potato beetle temperature depended growth and feeding rates. Environ. Entomol. 14, 343–348. doi: 10.1093/ee/14.3.343

Flanders, K. L., Hawkes, J. G., Radcliffe, E. B., and Lauer, F. I. (1992). Insect resistance in potatoes: sources, evolutionary relationships, morphological and chemical defenses, and ecogeographical associations. Euphytica 61, 83–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00026800

Follett, P. A., Cantelo, W. W., and Roderick, G. K. (1996). Local dispersal of overwintered Colorado potato beetle. Environ. Entomol. 25, 1304–1311. doi: 10.1093/ee/25.6.1304

Foster, G. E. (1876). “The Colorado potato beetle,” in Sixth Annu. Rep. Board Agric, ed J. O. Adams (Concord, NH: Edward A. Jenks), 233–240.

França, F. H., and Tingey, W. M. (1994). Solanum berthaultii Hawkes affects the digestive system, fat body and ovaries of the Colorado potato beetle. Am. Potato J. 71, 405–410. doi: 10.1007/BF02849403

Fréchette, B., Bejan, M., Lucas, É., Giordanengo, P., and Vincent, C. (2010). Resistance of wild Solanum accessions to aphids and other potato pests in Quebec field conditions. J. Ins. Sci. 10:161. doi: 10.1673/031.010.14121

Friedman, M., McDonald, G. M., and Filadelfi-Keszi, M. (1997). Potato glycoalkaloids: chemistry, analysis, safety, and plant physiology. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 16, 55–132. doi: 10.1080/07352689709701946

Fürstenberg-Hägg, J., Zagrobelny, M., and Bak, S. (2013). Plant defense against insect herbivores. Int. J. Mol. Sci.14, 10242–10297. doi: 10.3390/ijms140510242

Gassmann, A. J., Carrière, Y., and Tabashnik, B. E. (2009). Fitness costs of insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 54, 147–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090518

Gibson, A., Gorham, R. P., Hudson, H. F., Flock, J. A., and Motherwell, H. W. R. (1925). The Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say in Canada. Can. Dep. Agric. Bull. 52, 1–31.

Gibson, R. W. (1971). Glandular hairs providing resistance to aphids in certain wild potato species. Ann. Appl. Biol. 68, 113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1971.tb06448.x

Gibson, R. W., and Turner, R. H. (1977). Insect-trapping hairs on potato plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 23, 272–277. doi: 10.1080/09670877709412450

Ginzberg, I., Tokuhisa, J. G., and Veilleux, R. E. (2009). Potato steroidal glycoalkaloids: biosynthesis and genetic manipulation. Potato Res. 52, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11540-008-9103-4

Gollands, B., Tauber, M. J., and Tauber, C. A. (1991). Seasonal cycles of Myiopharus aberrans and M. doryphorae (Diptera: Tachinidae) parasitizing Colorado potato beetles in Upstate New York. Biol. Control. 1, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/1049-9644(91)90114-F

Grafius, E. J. (1995). Is local selection followed by dispersal a mechanism for rapid development of multiple insecticide resistance in the Colorado potato beetle? Am. Entomol. 41, 104–109. doi: 10.1093/ae/41.2.104

Grafius, E. J. (1997). Economic impact of insecticides resistance in the Colorado potato beetle on the Michigan potato industry. J Econ Entomo. 90, 1144–1151. doi: 10.1093/jee/90.5.1144

Grafius, E. J., and Douches, D. (2008). “The present and future role of insecticide-resistant genetically modified potato cultivars,” in IPM. Integration of Insect-Resistant Genetically Modified Crops Within IPM Programs, Vol.5, eds J. Romeis, A. Sheldon, and A. Kennedy (Dordrecht: Springer), 195–221.

Grapputo, A., Boman, S., Lindström, L., Lyytinen, A., and Mappes, J. (2005). The voyage of an invasive species across continents : genetic diversity of North American and European Colorado potato beetle populations. Mol. Ecol. 14, 4207–4219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02740.x

Gregory, P., Tingey, W. M., Ave, D. A., and Bouthyette, P. Y. (1986). “Potato glandular trichomes: a physicochemical defense mechanism against insects,” in Natural Resistance of Plants to Pests, Vol. 296, eds M. B. Green and P. A. Hedin (Washington, DC: American Chemical Society), 160–167.

Groden, E. (1989). Natural Mortality of the Colorado Potato Beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Ph.D. thesis), Michigan State University, Michigan (Say), 0841.

Groden, E., and Casagrande, R. A. (1986). Population dynamics of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), on Solanum berthaultii. J. Econ. Entomol. 79, 91–97. doi: 10.1093/jee/79.1.91

Groden, E., Drummond, F. A., Casagrande, R. A., and Haynes, D. L. (1990). Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): its predation upon the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and its incidence in potatoes and surrounding crops. J. Econ. Entomol. 83, 1306–1315. doi: 10.1093/jee/83.4.1306

Haegele, R. W., and Wakeland, C. (1932). Control of the Colorado Potato Beetle, Univ. Idaho, Coll. Agric. Ext. Circ. No. 42. Old Extension Publication.

Hardigan, M. A., Laimbeer, F. P. E., Newton, L., Crisovan, E., Hamilton, J. P., Vaillancourt, B., et al. (2017). Genome diversity of tuber-bearing Solanum uncovers complex evolutionary history and targets of domestication in the cultivated potato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E9999–E10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714380114

Hare, D. J. (1983). Seasonal Variation in Plant-Insect Associations : Utilization of Solanum dulcamara by Leptinotarsa decemlineata Author (s): J. Daniel Hare. Oxford: Wiley on behalf of the Ecological Society of America.

Hare, J. D. (1990). Ecology and management of the Colorado potato beetle. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 35, 81–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.000501

Hare, J. D., and Kennedy, G. G. (1986). Genetic variation in plant/insect associations: survival of Leptinotarsa decemlineata populations on Solanum carolinense. Evolution 40, 1031–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1986.tb00570.x

Hawthorne, D. J. (2001). AFLP based genetic linkage map of the Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata: sex chromosoma and a pyrethrois resistance candidate gene. Genetics 158, 695–700.

Hazzard, R. V., Ferro, D. N., Van Driesche, R. G., and Tuttle, A. F. (1991). Mortality of eggs of Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) from predation by Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Environ. Entomol. 20, 841–848. doi: 10.1093/ee/20.3.841

Heimpel, G. E., and Hough-Goldstein, J. A. (1992). A survey of arthropod predators of Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) in Delaware potato fields. J. Agric. Entomol. 9, 137–142.

Helm, D. C., Kennedy, G. G., and Van Duyn, A. W. (1990). Survey of insecticide resistance among North Carolina Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) populations. J. Econ. Entomol. 83, 1229–1235. doi: 10.1093/jee/83.4.1229

Hiiesaar, K., Metspalu, L., Joudu, J., and Jogar, K. (2006). Over-wintering of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) in field conditions and factors affecting its population density in Estonia. Agron. Res. 4, 21–30.

Hitchner, E. M., Kuhar, T. P., Dickens, J. C., Youngman, R. R., Schultz, R. R., and Pfeiffer, D. G. (2008). Host plant choice experiments of Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Virginia. J. Econ. Entomol. 101, 859–865. doi: 10.1093/jee/101.3.859

Horton, D. R., Capinera, J. L., and Chapman, P. L. (1988). Local differences in host use by two populatons of the Colorado potato beetle. Ecology 69, 823–831. doi: 10.2307/1941032

Horton, D. R., Chauvin, R. L., Hinojosa, T., Larson, D., Murphy, C., and Biever, K. D. (1997). Mechanisms of resistance to Colorado potato beetle in several potato lines and correlation with defoliation. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 82, 239–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.1997.00136.x

Hough-Goldstein, J., and McPherson, D. (1996). Comparison of Perillus bioculatus and Podisus maculiventris (Hemiptera:Pentatomidae) as potential control agents of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 89, 1116–1123. doi: 10.1093/jee/89.5.1116

Hough-Goldstein, J. A., Heimpel, G. E., Bechmann, H. E., and Mason, C. E. (1993). Arthropod natural enemies of the Colorado potato beetle. Crop Prot. 12, 324–334. doi: 10.1016/0261-2194(93)90074-S

Hough-Goldstein, J. A., and Whalen, J. (1996). Relationship between crop rotation distance from previous potatoes and colonization and population density of Colorado Potato Beetle. J. Agric. Entomol. 13, 293–300.

Hoy, C. W., Vaught, T. T., and East, D. A. (2000). Increasing the effectiveness of spring trap crops for Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 96, 193–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2000.00697.x

Hsiao, T. H. (1969). Chemical basis of host selection and plant resistance in oligophagous insects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 12, 777–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1969.tb02571.x

Hsiao, T. H. (1978). Host plant adaptations among geographic populations of the Colorado potato beetle. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 24, 237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1978.tb02804.x

Hsiao, T. H. (1981). “Ecophysiological adaptations among geographic populations of the Colorado potato beetle in North America,” in Advances in Potato Pest Management (Stroudsburg, PA: Hutchinson Ross Publ. Co.), 69–85.

Hunt, D. W. A., and Whitfield, G. (1996). Potato trap crops for control of Colorado potato beetle in tomatoes. Can. Entomol. 128, 407–412. doi: 10.4039/Ent128407-3

Hunt, E. R., and Rondon, S. I. (2017). Detection of potato beetle damage using remote sensing from small unmanned aircraft systems. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 11:026013. doi: 10.1117/1.JRS.11.026013

Hunt, E. R., Rondon, S. I., Hamm, P. B., Turner, R. W., Bruce, A. E., and Brungardt, J. J. (2016). “Insect detection and nitrogen management for irrigated potatoes using remote sensing from small unmanned aircraft systems,” in Autonomous Air and Ground Sensing Systems for Agricultural Optimization and Phenotyping, eds J. Valasek and J. A. Thomasson (International Society for Optics and Photonics), 98660N.

Huseth, A. S., Frost, K. E., Knuteson, D. L., Wyman, J. A., and Groves, R. L. (2012). Effects of landscape composition and rotation distance on Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) abundance in cultivated potato. Environ. Entomol. 41, 1553–1564. doi: 10.1603/EN12128

Huseth, A. S., and Groves, R. L. (2013). Effect of insecticide management history on emergence phenology and neonicotinoid resistance in Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 106, 2491–2505. doi: 10.1603/EC13277

Hutvágner, G., Bánfalvi, Z., Milánkovics, I., Silhavy, D., Polgár, Z., Horváth, S., et al. (2001). Molecular markers associated with leptinine production are located on chromosome 1 in Solanum chacoense: Theor. Appl. Genet. 102, 1065–1071. doi: 10.1007/s001220000450

Isely, D. (1935). Variations in the seasonal history of the Colorado potato beetle. J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 8, 142–145.

Itkin, M., Rogachev, I., Alkan, N., Rosenberg, T., Malitsky, S., Masini, L., et al. (2011). glycoalkaloid metabolism1 is required for steroidal alkaloid glycosylation and prevention of phytotoxicity in Tomato. Plant Cell 23, 4507–4525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088732

Izzo, V. M., Chen, Y. M., Schoville, S. D., Wang, C., and Hawthorne, D. J. (2018). Origin of pest lineages of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera : Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 111, 868–878. doi: 10.1093/jee/tox367

Izzo, V. M., Hawthorne, D. J., and Chen, Y. H. (2014). Geographic variation in winter hardiness of a common agricultural pest, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, the Colorado potato beetle. Evol. Ecol. 28, 505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10682-013-9681-8

Jacques, R. I. (1988). “The potato beetles: the genus Leptinotarsa in North America (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae),” in Flora and Fauna Handbook, ed E. J. Brill (New York, NY), 145.

Jansky, S. (2006). Overcoming hybridization barriers in potato. Plant Breed 125, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01178.x

Jansky, S., Austin-Philips, S., and McCarthy, C. (1999). Colorado potato beetle resistance in somatic hybrids of diploid interespecificis Solanum clones. HortScience 34, 922–927. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.34.5.922

Jansky, S. H., Dempewolf, H., Camadro, E. L., Simon, R., Zimnoch-Guzowska, E., Bisognin, D. A., et al. (2013). A case for crop wild relative preservation and use in potato. Crop Sci. 53, 746–754 doi: 10.2135/cropsci2012.11.0627

Jansky, S. H., Simon, R., and Spooner, D. M. (2009). A Test of taxonomic predictivity: resistance to the Colorado potato beetle in wild relatives of cultivated potato. J. Econom. Entomol. 102, 422–431. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0155

Jansky, S. H., and Spooner, D. M. (2018). “The Evolution of potato breeding,” in Plant Breeding Reviews, ed I. Goldman (Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 169–214.

Jin, L., Zhang, H., Lu, Y., Yang, Y., Wu, K., Tabashnik, B. E., et al. (2015). Large-scale test of the natural refuge strategy for delaying insect resistance to transgenic Bt crops. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 169–174. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3100

Johnston, R. L., and Sandvol, L. E. (1986). Susceptibility of Idaho populations of Colorado potato beetle to four classes of insecticides. Am. Potato J. 63, 81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02853686

Jolivet, P. (1991). The Colorado potato beetle menaces Asia (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say 1824). L'Entomologiste 47, 29–48.

Kaiser, N., Manrique-Carpintero, N. C., DiFonzo, C., Coombs, J., and Douches, D. (2020). Mapping Solanum chacoense mediated Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) resistance in a self-compatible F2 diploid population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 33, 2583–2603. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03619-8

Kaplanoglu, E., Chapman, P., Scott, I. M., and Donly, C. (2017). Overexpression of a cytochrome P450 and a UDP-glycosyltransferase is associated with imidacloprid resistance in the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Sci. Rep. 7:1762. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01961-4

Kelleher, J. S. (1966). The parasite Doryphorophaga doryphorae (Diptera: Tachinidae) in relation to populations of the Colorado potato beetle in Manitoba. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 59, 1059–1061. doi: 10.1093/aesa/59.6.1059

Kennedy, G. G., and Farrar, R. R. (1987). Response of insecticide-resistant and susceptible Colorado potato beetles, Leptinotarsa decemlineata to 2-tridecanone and resistant tomato foliage: the absence of cross resistance. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 45, 187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1987.tb01080.x

Kennedy, G. G., and Sorenson, C. F. (1985). Role of glandular trichomes in the resistance of Lycopersicum hirsutum to Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera; Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 78, 547–551. doi: 10.1093/jee/78.3.547

Khot, L. R., Sankaran, S., Carter, A. H., Johnson, D. A., and Cummings, T. F. (2016). UAS imaging-based decision tools for arid winter wheat and irrigated potato production management. Int. J. Remote Sens. 37, 125–137. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2015.1117685

King, R., Pelletier, Y., Singh, R., and Calhoun, L. (1986). 3, 4-0-isobutyryl-6-0-caprylsucrose: The major component of a novel sucrose ester complex from the type B glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii Hawkes (PI 473340). Chem. Comm. 1986, 1078–1079. doi: 10.1039/c39860001078

King, R. R., Singh, R. P., and Boucher, A. (1987a). Variation in sucrose esters from the type B glandular trichomes of certain wild potato species. Am. J. Potato Res. 64, 529–534. doi: 10.1007/BF02853751

King, R. R., Singh, R. P., and Calhoun, L. A. (1987b). Isolation and characterization of 3,3′,4,6-tetra- O -acylated sucrose esters from the type B glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii Hawkes (PI 265857). Carbohydr. Res. 166, 113–121. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(87)80048-4

Koss, A. M., Chang, G. C., and Snyder, W. E. (2004). Predation of green peach aphids by generalist predators in the presence of alternative, Colorado potato beetle egg prey. Biol. Control. 31, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.04.006

Koss, A. M., Jensen, A. S., Schreiber, A., and Pike, K. S. (2005). Comparison of predator and pest communities in Washington potato fields treated with broad-spectrum, selective, or organic insecticides. Environ. Entomol. 34, 87–95. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-34.1.87

Kowalski, S. P., Domek, J. M., Deahl, K. L., and Sanford, L. L. (1999). Performance of Colorado potato beetle larvae, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say), reared on synthetic diets supplemented with Solanum glycoalkaloids. Am. J. Potato Res. 76, 305–312. doi: 10.1007/BF02853629

Kowalski, S. P., Domek, J. M., Sanford, L. L., and Deahl, K. L. (2000). Effect of α-tomatine and tomatidine on the growth and development of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): studies using synthetic diets. J. Entomol. Sci. 35, 290–300 doi: 10.18474/0749-8004-35.3.290

Kowalski, S. P., Eannetta, N. T., Hirzel, A. T., and Steffens, J. C. (1992). Purification and characterization of polyphenol oxidase from glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii. Plant Physiol. 100, 677–684. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.677

Lapointe, S. L., and Tingey, W. M. (1986). Glandular trichomes of Solanum neocardenasii confer resistance to green peach aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol. 79, 1264–1268. doi: 10.1093/jee/79.5.1264

Lashomb, J. H., and Ng, Y. (1984). Colonization by Colorado potato beetles, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), in rotated and nonrotated potato fields. Environ. Entomol. 13, 1352–1356. doi: 10.1093/ee/13.5.1352

Latheef, M. A., and Harcourt, D. G. (1974). The dynamics of Leptinotarsa decemlineata populations on tomato. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 17, 67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1974.tb00319.x

Li, C., Cheng, D., Guo, W., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., and Sun, J. (2013). Atraction effect of different host-plant to Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Shengtai Xuebao Acta Ecol. Sin. 33, 2410–2415. doi: 10.5846/stxb201203130338

Li, C., Liu, H., Huang, F., Cheng, D., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., et al. (2014). Effect of temperature on the occurrence and distribution of Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in China. Environ. Entomol. 43, 511–519. doi: 10.1603/EN13317

Li, H. Y., Chen, Q., Beasley, D., Lynch, D. R., and Goettel, M. (2006). Karyotypic evolution and molecular cytogenetic analysis of Solanum pinnatisectum, a new source of resistance to late blight and Colorado potato beetle in potato. Cytologia 71, 25–33. doi: 10.1508/cytologia.71.25

Li, Y., Colleoni, C., Zhang, J., Liang, Q., Hu, Y., Ruess, H., et al. (2018). Genomic Analyses yield markers for identifying agronomically important genes in potato. Molecular Plant. 11, 473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.01.009

Li, Y., Gao, Y., and Wu, K. (2017). Function and effectiveness of natural refuge in IRM strategies for Bt crops. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 21, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.04.007

Logan, P. A., Casagrande, R. A., Hsiao, T. H., and Drummond, F. A. (1987). Collections of natural enemies of Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Mexico. Entomoph. 32, 249–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02373247

Lopez, E. R., Ferro, D. N., and Van Driesche, R. G. (1993). Direct measurement of host and parasitoid recruitment for assessment of total losses due to parasitism in the Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and Myiopharus doryphorae (Riley) (Diptera: Tach. Biol. Control. 3, 85–92. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1993.1014

Lopez, E. R., Roth, L. C., Ferro, D. N., Hosmer, D., and Mafra-Neto, A. (1997). Behavioral ecology of Myiopharus doryphorae (Riley) and M. aberrans (Townsend), tachinid parasitoids of the Colorado potato beetle. J. Insect Behav. 10, 49–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02765474

Lorenzen, J. H., Balbyshev, N. F., Lafta, A. M., Casper, H., Tian, X., and Sagredo, B. (2001). Resistant potato selections contain leptine and inhibit development of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 94, 1260–1267. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-94.5.1260

Lynch, C. A. (2013). Exploring Consumption by Two Generalist Predators in Potatoes Using Molecular Gut Content Analysis and Behavioral Studies (PhD thesis), Washington State University.

Lynch, M., and Walsh, B. (1998). Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits, Vol. 1 (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer), 535–557.

Ma, M.-Q., He, W. W., Xu, S. J., Xu, L. T., and Zhang, J. (2020). RNA interference in Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata): a potential strategy for pest control. J. Integrative Ag. 19, 428–437. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62702-4

Maharijaya, A., and Vosman, B. (2015). Managing the Colorado potato beetle; the need for resistance breeding. Euphytica 204, 487–501. doi: 10.1007/s10681-015-1467-3

Mahlein, A.-K. (2016). Plant Disease Detection by imaging sensors – parallels and specific demands for precision agriculture and plant phenotyping. Plant Dis. 100, 241–251. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-15-0340-FE

Mail, G. A., and Salt, R. W. (1933). Temperature as a possible limiting factor in the northern spread of the colorado potato beetle. J. Econ. Entomol. 26, 1068–1075. doi: 10.1093/jee/26.6.1068

Malakar-Kuenen, R., and Tingey, W. M. (2006). Aspects of tuber resistance in hybrid potatoes to potato tuber worm. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 120, 131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00435.x

Manrique-Carpintero, N. C., Tokuhisa, J. G., Ginzberg, I., and Veilleux, R. E. (2014). Allelic variation in genes contributing to glycoalkaloid biosynthesis in a diploid interspecific population of potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 391–405. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2226-2

Martel, J. W., Alford, A. R., and Dickens, J. C. (2005). Synthetic host volatiles increase efficancy of trap cropping for management of Colorado potato beetle Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say). Agric. For. Entomol. 7, 79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-9555.2005.00248.x

Mehlenbacher, S. A., Plaisted, R. L., and Tingey, W. M. (1983). Inheritance of glandular trichomes in crosses with Solanum berthaultii. Am. J. Potato Res. 60, 699–708. doi: 10.1007/BF02852841

Mena-Covarrubias, J., Drummond, F. A., and Haynes, D. L. (1996). Population dynamics of the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on horsenettle in Michigan. Environ. Entomol. 25, 68–77. doi: 10.1093/ee/25.1.68

Metspalu, L., Mitt, S., and Eesti Põllumajandusülikool International Conference on Development of environmentally friendly plant protection in the Baltic Region. (2000). Development of Environmentally Friendly Plant Protection in the Baltic Region: Proceedings of the International Conference, Tartu Estonia, September 28-29, 2000. Tartu University Press.

Mi, X., Ji, X., Yang, J., Liang, L., Si, H., Wu, J., Zhang, N., and Wang, D. (2015). Transgenic potato plants expressing cry3A gene confer resistance to Colorado potato beetle. Comptes Rendus Biol. 338, 443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2015.04.005

Michaud, D., Nguyen-Quoc, B., and Yelle, S. (1993). Selective inhibition of Colorado potato beetle cathepsin H by oryzacystatins I and II. FEBS Lett. 331, 173–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80320-T

Milner, S. E., Brunton, N. P., Jones, P. W. O.', Brien, N. M., Collins, S. G., and Maguire, A. R. (2011). Bioactivities of glycoalkaloids and their aglycones from Solanum species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 3454–3484. doi: 10.1021/jf200439q

Mitkowski, N. A., and Abawi, G. S. (2003). Root-knot nematodes. Plant Health Instruct. doi: 10.1094/PHI-I-2003-0917-01

Mohammed, A., Douches, D. S., Pett, W., Grafius, E., Coombs, J., Linswidowati, L., et al. (2000). Evaluation of potato tubermoth (Lepidoptera: gelechiidae) resistance in tubers of Bt-cry5 transgenic potato lines. J. Econ. Entomol. 93, 472–476. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-93.2.472

Mweetwa, A. M., Hunter, D., Poe, R., Harich, K. C., Ginzberg, I., Veilleux, R. E., et al. (2012). Steroidal glycoalkaloids in Solanum chacoense. Phytochemistry 75, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.003

Navarre, D. A., Shakya, R., and Hellmann, H. (2016). “Vitamins, phytonutrients, and minerals in potato,” in Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology (Amsterdam: Academic Press), 117–166.

Neal, J. J., Steffens, J. C., and Tingey, W. M. (1989). Glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii and resistance to the Colorado potato beetle. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 51, 133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1989.tb01223.x

Noronha, C., and Cloutier, C. (1999). Ground and aerial movement of adult Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomeliae) in a univoltine population. Can. Entomol. 131, 521–538. doi: 10.4039/Ent131521-4

Olson, E. R., Dively, G. P., and Nelson, J. O. (2000). Baseline susceptibility to imidacloprid and cross resistance patterns in Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) populations. J. Econ. Entomol. 93, 447–458. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-93.2.447

Paudel, J. R., Gardner, K. M., Bizimungu, B., De Koeyer, D., Song, J., and Tai, H. H. (2019). Genetic mapping of steroidal glycoalkaloids using selective genotyping in potato. Am. J. Pot. Res. 96, 505–516. doi: 10.1007/s12230-019-09734-7

Pelletier, Y. (1995). Effects of temperature and relative humidity on water loss by the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say). J. Insect Physiol. 41, 235–239. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(94)00103-N

Pelletier, Y. (1998). Determination of the lethal high temperature for the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Can. Agric. Eng. 40, 185–189.

Pelletier, Y. (2007). Level and genetic variability of resistance to the colorado potato beetle [Leptinotarsa decemlineata (say)] in wild solarium species. Am. J. Potato Res. 84, 143–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02987137

Pelletier, Y., Clark, C., and Tai, G. C. (2001). Resistance of thee wild tuber-bearing potatoes to the Colorado potato beetle. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 100, 31–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2001.00845.x

Pelletier, Y., and Dutheil, J. (2006). Behavioral responses of the Colorado potato beetle to trichomes and lead surface chemicals of Solanum tarijense. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 120, 125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00432.x

Pelletier, Y., Grondin, G., and Mathias, P. (1999). Mechanism of resistance to the Colorado potato beetlein wild Solanum species. J. Econ. Entomol. 92, 708–713. doi: 10.1093/jee/92.3.708

Pelletier, Y., Horgan, F. G., and Pompom, J. (2011). Potato resistance to insects. Am. J. Pot. Sci. 5, 37–51.

Piiroinen, S., Boman, S., Lyytinen, A., Mappes, J., and Lindström, L. (2014). Sublethal effects of deltamethrin exposure of parental generations on physiological traits and overwintering in Leptinotarsa decemlineata. J. Appl. Entomol. 138, 149–158. doi: 10.1111/jen.12088

Plaisted, R. L., Tingey, W. M., and Steffens, J. C. (1992). The germplasm release of NYL 235–4, a clone with resistance to the Colorado potato beetle. Am. J. Potato Res. 69, 843–846. doi: 10.1007/BF02854192

Puig, E., Gonzalez, F., Hamilton, G., and Grundy, P. (2015). “Assessment of crop insect damage using unmanned aerial systems: a machine learning approach,” in MODSIM2015, 21st International Congress on Modelling and Simulation. 21st International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM2015), eds T. Weber, M. J. McPhee, and R. S. Anderssen.

Ramirez, R. A., Henderson, D. R., Riga, E., Lacey, L. A., and Snyder, W. E. (2009). Harmful effects of mustard bio-fumigants on entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol. Control. 48, 147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.10.010

Rangarajan, A., Miller, A. R., and Veilleux, R. E. (2000). Leptine glycoalkaloids reduce feeding by Colorado potato beetle in diploid Solanum sp. hybrids. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 125, 689–693 doi: 10.21273/JASHS.125.6.689

Rifai, N. M., Astatlie, T., Lacko-Bartosova, M., and Otepka, P. (2004). Evaluation of thermal, pneumatic and biological methods for controlling Colorado potato beetles (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say). Potato Res. 47, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02731967

Riley, C. V. (1869a). First Annual Report on the Noxious, Beneficial and Other Insects, of the State of Missouri - Part 2. Jefferson City, MO: Ellwood Kirby.

Riley, C. V. (1869b). “First annual report on the noxious, beneficial and other insects of the State of Missouri,” in 4th Annu. Rep. State Bd. Agric, 80–81.

Rondon, S. I., Hane, D. C., Brown, C. R., Vales, M. I., and Dogramaci, M. (2009). Resistance of potato germplasm to the potato tuberworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 102, 1649–1653. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0432

Rondon, S. I., Pantoja, A., Hagerty, A., and Horneck, D. A. (2013). Ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) populations in commercial organic and conventional potato production. Fla. Entomol. 96, 1492–1499. doi: 10.1653/024.096.0430

Ronning, C. M., Sanford, L. L., Kobayashi, R. S., and Kowalsld, S. P. (1998). Foliar leptine production in segregating F1, Inter-F1, and backcross families of Solanum chacoense bitter. Am. J. Pot. Res. 75, 137–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02895848

Ronning, C. M., Stommel, J. R., Kowalski, S. P., Sanford, L. L., Kobayashi, R. S., and Pineada, O. (1999). Identification of molecular markers associated with leptine production in a population of Solanum chacoense bitter: Theor. Appl. Genet. 98, 39–46. doi: 10.1007/s001220051037

Ryan, J. D., Gregory, P., and Tingey, W. M. (1982). Phenolic oxidase activities in glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii. Phytochemistry 21, 1885–1887. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(82)83008-2

Sablon, L., Haubruge, E., and Verhegeen, F. J. (2013). Consumption of immature stages of Colorado potato beetle by Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) larvae in the laboratory. Am. J. Pot. Res. 90, 51–57. doi: 10.1007/s12230-012-9275-y

Sagredo, B., Balbyshev, N., Lafta, A., Casper, H., and Lorenzen, J. (2009). A QTL that confers resistance to Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata [Say]) in tetraploid potato populations segregating for leptine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 1171–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1118-y

Sanford, L. L., Kobayashi, R. S., Deahl, K. L., and Sinden, S. L. (1996). Segregation of leptines and other glycoalkaloids in Solanum tuberosum (4x) x S. chacoense (4x) crosses. Am. J. Pot. Res. 73, 21–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02849301

Sanford, L. L., Kobayashi, R. S., Deahl, K. L., and Sinden, S. L. (1997). Diploid and tetraploid Solanum chacoense genotypes that synthesize leptine glycoalkaloids and deter feeding by Colorado potato beetle. Am. J. Pot. Res. 74, 15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02849168

Saunders, W., and Reed, E. (1871). Report on the Colorado potato beetle. Can. Entomol. 3, 41–51. doi: 10.4039/Ent341-3

Schoville, S. D., Chen, Y. H., Andersson, M. N., Benoit, J. B., Bhandari, A., Bowsher, J. H., et al. (2018). A model species for agricultural pest genomics: the genome of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Sci. Rep. 8:1931. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20154-1

Sexson, D. L., and Wyman, J. A. (2005). Effect of crop rotation distance on populations of Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): development of areawide Colorado potato beetle pest management strategies. J. Econ. Entomol. 98, 716–724. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-98.3.716

Sexson, D. L., Wyman, J. A., Ratcliffe, E. B., Hoy, C. J., Ragsdale, D. W., and Dively, G. P. (2005). in Vegetable Insect Management, eds G. P. Dively, R. Foster, and B. Floods (Willoughby: Meister Publishing), 92–107.

Shakya, R., and Navarre, D. A. (2008). LC-MS analysis of solanidane glycoalkaloid diversity among tubers of four wild potato species and three cultivars (Solanum tuberosum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 6949–6958. doi: 10.1021/jf8006618

Sharma, S. K., MacKenzie, K., McLean, K., Dale, F., Daniels, S., and Bryan, G. J. (2018). Linkage disequilibrium and evaluation of genome-wide association mapping models in tetraploid potato. G3 8, 3185–3202. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200377

Sikinyi, E., Hannapel, D. J., Imerman, P. M., and Stahr, H. M. (1997). Novel mechanism for resistance to Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in wild Solanum species. J. Econ. Entomol. 90, 689–696.

Sinden, S. L., Sanford, L. L., Cantelo, W. W., and Deahl, K. L. (1986b). Leptine glycoalkaloids and resistance to the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Solanum chacoense. Environ. Entomol. 15, 1057–1062. doi: 10.1093/ee/15.5.1057