- 1Department of Radiological and Surgical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

- 2Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Cell Biology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

Sepsis is the leading cause of critical illness and mortality in human beings and animals. Neutrophils are the primary effector cells of innate immunity during sepsis. Besides degranulation and phagocytosis, neutrophils also release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), composed of cell-free DNA, histones, and antimicrobial proteins. Although NETs have protective roles in the initial stages of sepsis, excessive NET formation has been found to induce thrombosis and multiple organ failure in murine sepsis models. Since the discovery of NETs nearly a decade ago, many investigators have identified NETs in various species. However, many questions remain regarding the exact mechanisms and fate of neutrophils following NET formation. In humans and mice, platelet-neutrophil interactions via direct binding or soluble mediators seem to play an important role in mediating NET formation during sepsis. Preliminary data suggest that these interactions may be species dependent. Regardless of these differences, there is increasing evidence in human and veterinary medicine suggesting that NETs play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of intravascular thrombosis and multiple organ failure in sepsis. Because the outcome of sepsis is highly dependent on early recognition and intervention, detection of NETs or NET components can aid in the diagnosis of sepsis in humans and veterinary species. In addition, the use of novel therapies such as deoxyribonuclease and non-anticoagulant heparin to target NET components shows promising results in murine septic models. Much work is needed in translating these NET-targeting therapies to clinical practice.

Introduction

Despite recent advances in medicine, sepsis remains one of the leading causes of death in critically ill people and animals (1–3). Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection (4). Multiple organ dysfunction, associated with increased mortality and morbidity, is a common manifestation of sepsis (1, 5). Factors such as virulence of the invading organisms, co-morbidities, and the host immunocompetence dictate the progression and outcome of sepsis (3, 6, 7).

Neutrophils are short-lived granulocytes that play a pivotal role in the initial defense against invading pathogens in mammals. Neutrophils, recruited to the site of infection, effectively kill microorganisms by phagocytosis, degranulation, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (8). In certain conditions, neutrophils enhance their antimicrobial properties by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), composed of extracellular chromatin decorated with histones and numerous granular proteins (9). Many of these granular components like myeloperoxidase (MPO), α-defensins, elastase (NE), cathepin G, and lactoferrin, have bactericidal activities capable of eliminating microorganisms and/or their virulence factors. Uncontrolled inflammatory response during sepsis is the proposed underlying cause of excessive NET formation (10, 11). Increasing experimental and clinical evidence indicates that overzealous NET formation during sepsis can lead to the development of multiple organ dysfunction highlighting the pathophysiological role of NETs in sepsis (12–15). This review aims to summarize the recent knowledge on the underlying mechanisms of NET formation in varied species, as well as, the beneficial and detrimental effects of NETs found in various septic animal models.

Mechanism of NETosis

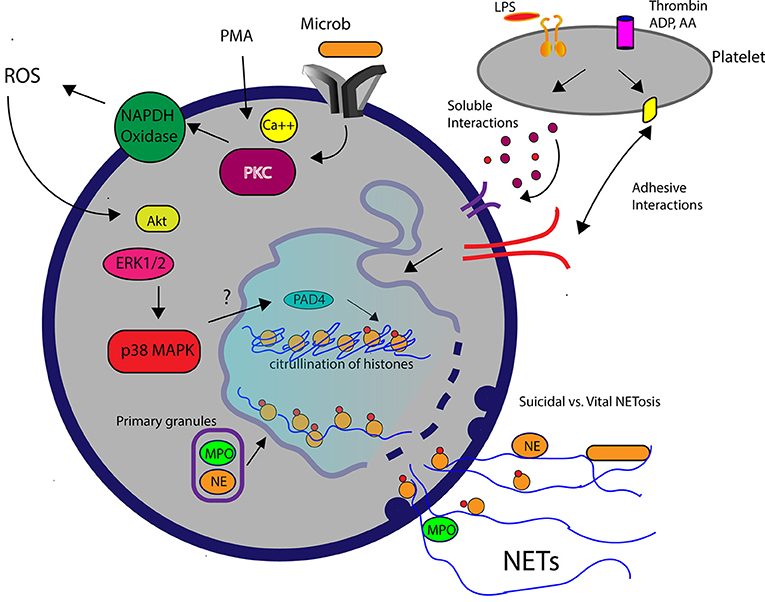

As sentinel cells of innate immunity, neutrophils can respond to many pathogens or their associated molecular patterns by releasing NETs. “NETosis” is the term commonly used to describe the sequence of cellular events leading up to the active release of NETs (9, 16). Similar to other forms of cell death such as apoptosis or programmed cell death and necroptosis, a regulated form of necrosis, NETosis is a highly regulated process. Dysregulation of NETosis found in many disease states like sepsis, can result in collateral damage to the host. The cellular mechanisms mediating the release of NETs, however, remain poorly understood. Brinkmann et al. and Fuchs et al. first documented in vitro NETosis in human neutrophils using the potent protein kinase C activator, phorbal 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (17, 18). Following PMA stimulation, human neutrophils undergo morphological changes including chromatin decondensation, loss of nuclear envelope, mixing of nuclear contents and cytoplasmic granular proteins, loss of membrane integrity and, ultimately, release of cell free DNA (cfDNA) (18). A recent ex vivo study by the authors documented similar morphological changes in PMA-activated canine neutrophils indicating that dog neutrophils may undergo suicidal NETosis (19). Cell death is inevitable in neutrophils undergoing suicidal NETosis as they are unable to maintain a constant intracellular environment without an intact cell membrane. For that reason, some investigators describe this type of NETosis as “lytic” or “suicidal” (16). Table 1 is a summary of microorganisms known to induce NETosis in various species.

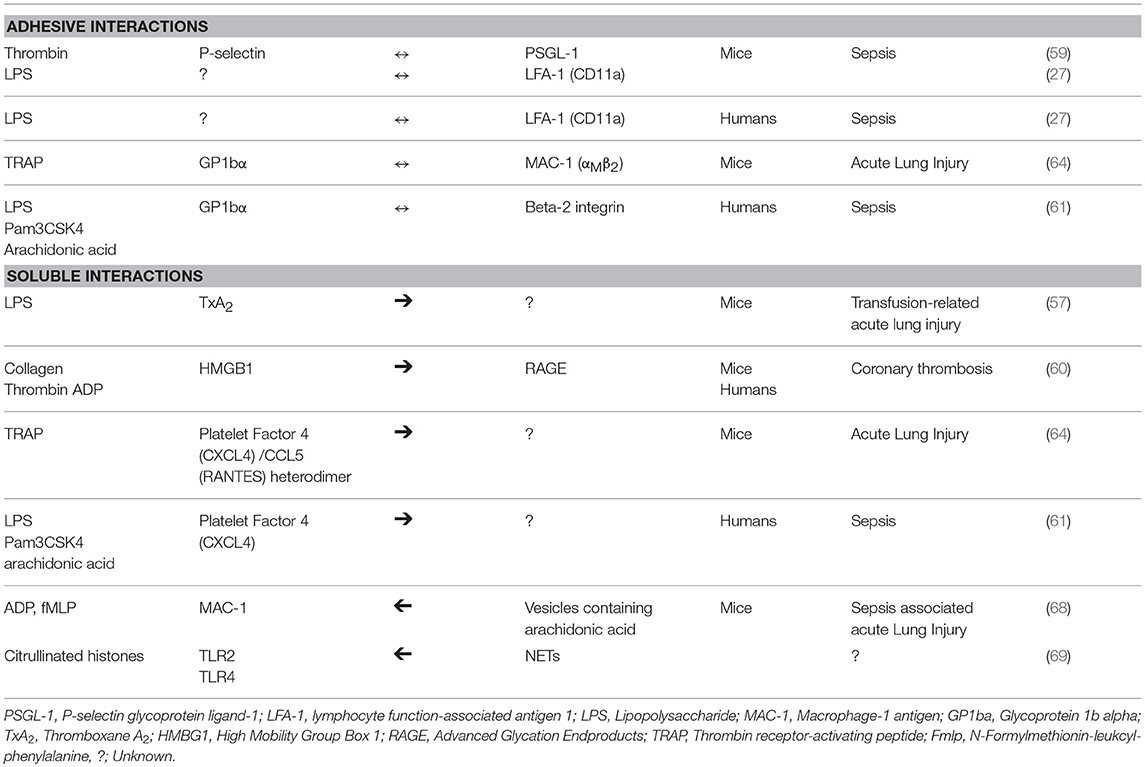

Table 1. Summary of mechanisms of microorganisms-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation in various species.

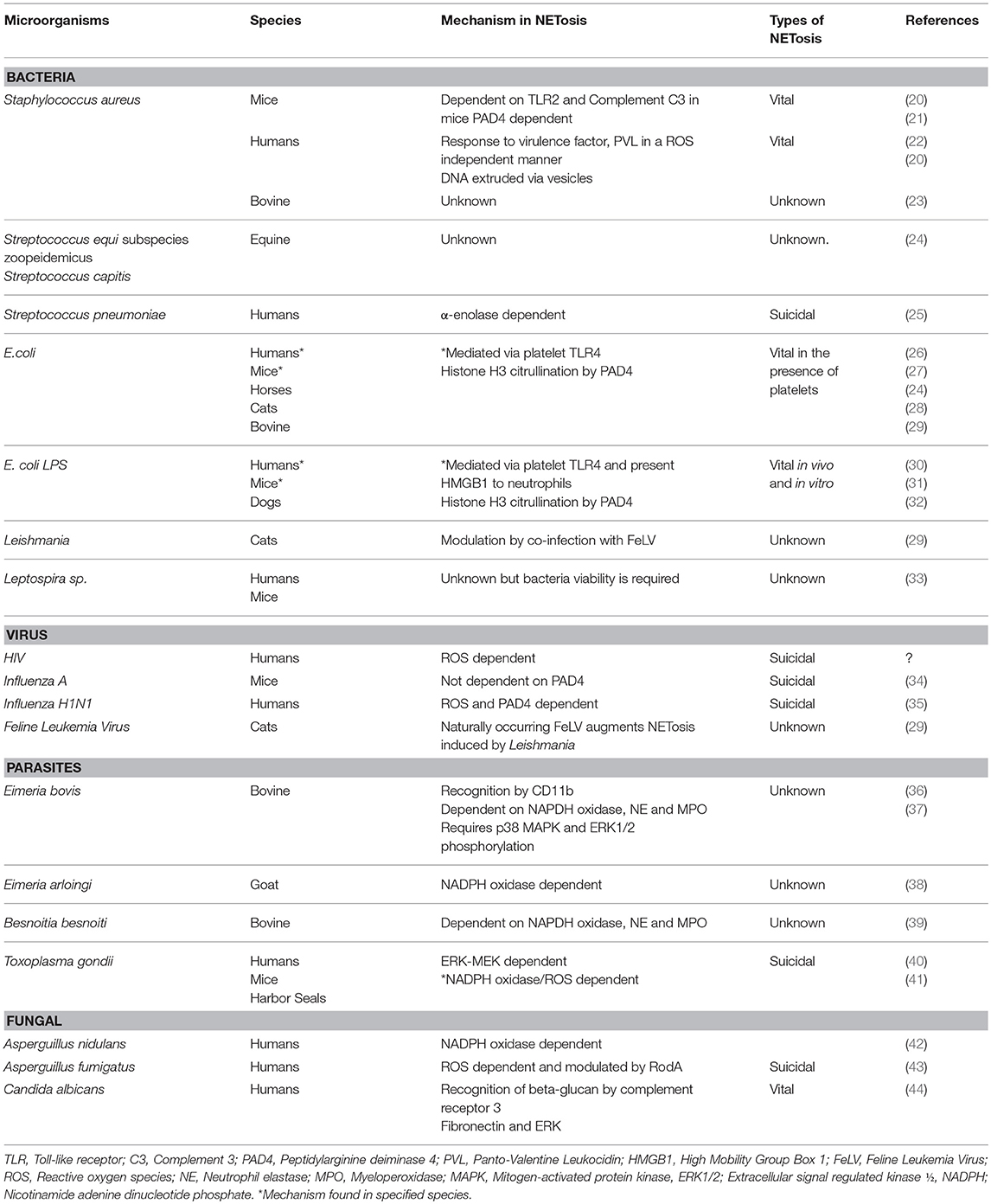

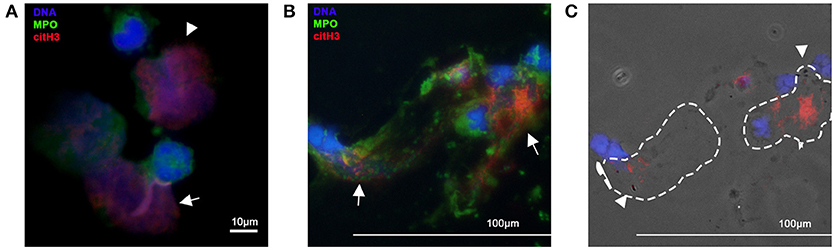

The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by NAPDH oxidase is an integral, but not essential, cellular process in NETosis. Suicidal NETosis induced by PMA and pathogens such as Aspergillus fumigatus and Toxoplasma gondii are dependent on ROS generation, which occurs upstream of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation (45, 46) (Figure 2). Interestingly, although PMA-activated neutrophils in horses undergo ROS generation, PMA is considered a weak trigger of ex vivo NETosis, suggesting that the role of ROS in NETosis may vary among species (24, 47) (Figure 1A). It is not yet clear how ROS generation and its downstream effects ultimately lead to chromatin decondensation and the release of cfDNA. Papyannopoulos et al. found that the translocation of both neutrophil elastase (NE) and myeloperoxidase granules from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is essential for chromatin decondensation during PMA-mediated NETosis. This process appears to be independent of the enzymatic activities of NE but the exact molecular mechanism responsible for this translocation is unclear (48).

Figure 1. Immunofluorescent imagines of equine and canine neutrophils. Neutrophils were fixed, permeabilized and stained for citrullinated histone H3 (red) and myeloperoxidase (MPO). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue) (A) Isolated equine neutrophils were incubated with the calcium ionophore, A23187, for 2 h. Note the intracellular expression of citH3 in neutrophils (arrow heads) and release of NETs decorated with MPO and citH3 (arrow). Original 100x magnification (B) Cells collected from endotracheal wash from a dog with aspiration pneumonia. Note the extent of cell-free DNA and colocalization of MPO and citH3 (NETs) (arrows) (C) In the respective phase contrast image, bacteria (arrow heads) can be detected within NETs (dotted outline). Original 40x magnification.

Figure 2. A schematic diagram demonstrating the molecular pathways involved in NETosis. Elevation of intracellular calcium in the presence of phorbal 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or microbial interaction WITH pathogen recognition receptors on neutrophils subsequently activates protein kinase C (PKC) and NAPDH oxidase. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by NADPH oxidase leads to downstream signaling mediated by Akt, extracellular signal regulated kinsase (ERK1/2) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Decondensation of chromatin requires translocation of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and neutrophil elastase (NE) into the nucleus and histone citrullination (citH3), facilitated by the enzyme, peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4). Activated platelets in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or agonists such as thrombin stimulate neutrophils to produced NETs via soluble or adhesive interations.

Many critics question the physiological relevance of PMA-mediated NETosis (49, 50). First, NETosis induced by PMA in vitro requires hours to occur, whereas neutrophils in vivo normally undergo phagocytosis and degranulation within minutes after encountering microorganisms. Second, some investigators consider PMA-induced NETosis “suicidal,” given that PMA-activated neutrophils can no longer maintain normal cell function following NETosis. To better understand the relevance of NETosis in vivo, Yipp et al. directly visualized the behaviors of neutrophils within Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) skin infections in mice and human beings using intravital microscopy. They found that neutrophils undergo chromatin decondensation and DNA release within minutes after encountering S. aureus while maintaining an intact cell membrane. Interestingly, the NETosing neutrophils, now anuclear, continued to chemotax to and phagocytize nearby bacteria (20). This unique mechanism of NETosis, termed “vital” NETosis, was later confirmed in septic murine models using either lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or E. coli. Besides maintaining their functional capacity following vital NETosis, neutrophils must somehow release their DNA while preserving the integrity of the cell membrane. The Kubes laboratory answered this question by demonstrating that in the presence of S. aureus human neutrophils form budding DNA-containing vesicles from the nuclear envelop, which later, fuse with the plasma membrane to release DNA to the extracellular space (22) (Figure 2). In horses, ex vivo exposure of neutrophils to endometritis causing bacteria, also results in rapid NET formation but the viability and functional capacity of those neutrophils remain unknown (24). To date, how neutrophils commit to one form of NETosis over the other remains unclear, but some investigators believe that it may be stimulus-dependent (11, 16).

Studies in murine, human, and canine neutrophils demonstrated that NETosis and the release of histones and DNA require histone post-translational modification (30, 51, 52). Histone citrullination, catalyzed by the enzyme, peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4), results in a net loss of positive charge of histones. This, in turn, obliterates electrostatic interactions between DNA and histones causing chromatin decondensation and release of cfDNA during NETosis (53–55). Induction of PAD4 activation in neutrophils appears to be stimuli dependent. The proinflammatory cytokine, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, hydrogen peroxide and molecular patterns like LPS and lipoteichoic acid have been shown to induce PAD4 activation and histone citrullination (19, 30, 32, 55). The elevation of citrullinated histones in clinical septic patients suggest that ongoing activation of PAD4 occurs during sepsis.

NETosis and Platelet-Neutrophil Interaction

In addition to being the primary effector cells of hemostasis, recent evidence indicates that murine, human and canine platelets play a direct role in innate immunity by directly interacting with pathogens or recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Platelets also augment innate immunity by facilitating NETosis via platelet-neutrophil interaction (26). In ex vivo systems, human, murine, and canine neutrophils undergo a limited degree of NETosis in response to LPS (19, 31, 56). But in the presence of LPS-activated platelets, murine and human neutrophils release substantial amounts of NETs, indicating that sepsis-associated NETosis is highly dependent on platelet-neutrophil interaction. Clark et al. first discovered that platelet-mediated NETosis induced by LPS in humans is dependent on platelet Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (26). Subsequent studies in mouse sepsis models showed that intravascular NETosis under shear conditions is highly dependent on platelet-neutrophil interaction. McDonald et al. found that LPS-treated mice not only had increased platelet-neutrophil aggregates but also NETs within their liver sinusoids. However, this process does not occur in platelet-depleted mice treated with the same doses of LPS (27). In addition to LPS, platelets activated by the agonists, thrombin, ADP, and arachidonic acid also stimulate NETosis in humans and mice (57). The exact mechanism of platelet-mediated NETosis, however, is not clearly understood and, likely, differs among species.

In general, platelet-neutrophil interactions can be broadly divided into 2 mechanisms: adhesive and soluble. Regardless of the mechanisms involved, platelet activation induced by pathogens, damage-associated molecular patterns, or classic agonists must occur in order for secretion of soluble mediators and expression/activation of adhesion molecules to occur. Platelet activation by stimulants results in inside-out signaling that leads to the expression of P-selectin and a conformational change in the extracellular domains of the integrin, αIIbβ3, increasing its affinity for ligands. The binding of platelet P-selectin to its neutrophil receptor, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is shown to be essential in inducing NETosis in mice with sepsis and transfusion-induced acute lung injury (58, 59). However, treatment of activated human platelets with anti-P-selectin function blocking antibodies does not attenuate NETosis suggesting that P-selectin/PSGL-1-mediated NETosis may be species dependent (60, 61). In mice and humans, platelet-neutrophil interaction and NETosis also are mediated by the binding of αMβ2 (MAC-1), a neutrophil integrin, to its counterreceptor, glycoprotein 1bα (GP1bα), a heterodimeric glycoprotein on platelets (62–64).

Upon activation, platelets secrete a variety of soluble mediators like high mobility group box-1 (HMBG-1) and platelet factor 4 (PF4), known to modulate NETosis. Platelet factor 4 or CXCL4 and CCL5 (RANTES), released by LPS-activated platelets, are platelet-derived chemokines that can activate neutrophils to undergo adhesion. In mice, thrombin-stimulated platelets release both CXCL4 and CCL5, which induce NETosis via the neutrophil G-protein coupled receptors. The heterodimerization of platelet-derived CXCL4 and CCL5 are found to enhance NETosis (64). LPS or the synthetic lipopeptide, Pam3CSK4, also stimulates platelets via TLR 4 or 2, respectively, to release CXCL4 enhancing NETosis in human neutrophils (61). Platelet-derived HMGB-1, a damage-associated molecular pattern, secreted by activated platelets, stimulates human and mouse neutrophils to undergo NETosis by binding to receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE). The role of HMGB1-RAGE signaling pathway in the formation of NETs is unclear but downstream pathways of RAGE have been shown to facilitate autophagy, an essential cellular event during NETosis (60, 65–67). Activated neutrophils also contribute to this cellular cross-talk by shuttling arachidonic acid containing extracellular vesicles to platelets, in which arachidonic acid is synthesized to thromboxane A2 by cyclooxygenase-1 for further platelet activation (68). It is important to note that the adhesive and soluble interactions between platelets and neutrophils synergistically mediate NETosis since inhibition of either type of interaction inhibits NET formation. Table 2 summarizes the molecular interactions between neutrophils and platelets during NETosis.

Beneficial Role of NETs in Sepsis

Microbial Trapping and Prevention of Dissemination

In a mouse model of necrotizing fasciitis, PAD4 knockout mice with the decreased ability to produce NETs were more susceptible to Staphylococcus (S.) aureus infection strongly suggesting that NETs have protective roles in the defense against invading organisms (21). NETs have been shown to exert antimicrobial activities by physically trapping or directly killing microorganisms. The earliest evidence of the antimicrobial properties of NETs was gathered using high-definition scanning electron microscopy. Microorganisms including: Shigella flexneri, S. aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans, and Leishmania were observed to be physically attached onto the structural elements of NETs. The ability of NETs to trap bacteria was confirmed by Buchanan et al., who utilized group A Streptococcus that expresses deoxyribonuclease (DNase), in a mouse model of necrotizing fasciitis. The group found that mice treated with the strain that expresses DNase had more substantial skin lesions and bacterial dissemination indicating that NETs not only enhance the killing of bacteria but also ensnare bacteria to hinder their spread (70). This was further confirmed by McDonald et al. who utilized fluorescently labeled E. coli to document in vivo trapping of bacteria within the liver sinusoids in LPS-treated mice (27). The group also found that NETs within the liver sinusoids potentiate the ability of the liver to entrap bacteria once the Kupffer cells are overwhelmed by extensive bacteremia. As expected, microorganisms that possess the ability to rapidly breakdown DNA are more virulent. For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae, a Gram-positive bacteria commonly found in the human respiratory tract, can express the virulence factor, endA, which degrades DNA, allowing for bacteremia and sepsis to occur (71). We recently demonstrated that NETs within the septic foci of clinical septic dogs can bind directly to bacteria suggesting that entrapment of bacteria by NETs may occur in dogs (Figures 1B,C) (72).

Direct Antimicrobial Activity

In theory, NETs should possess antimicrobial properties since NET components like histones, cathepsin G, and MPO can exert bactericidal activities. However, the direct antimicrobial activity of NETs in vivo is controversial. The conflicting published data likely reflects the different methods used to measure the antimicrobial properties of NETs (73). The most direct way of evaluating the microcidal properties of NETs in vitro is by culturing microbes and assessing their viability after incubation with NET-forming neutrophils. Using this method, studies found that NETs dismantled by DNase digestion allowed for the growth of entrapped S. aureus and Candida albicans (74). One plausible explanation for this, is that granular proteases released into the extracellular space are rapidly inactivated by plasma alpha1-proteinase inhibitor. Proteases like NE must, therefore, be shielded from nucleic acids in order to carry out its proteolytic and microcidal activities. Another method used by investigators is to assess the viability of microbes in the presence of neutrophils that are unable to produce NETs. By using neutrophils from human patients with chronic granulomatous disease, a familial disease caused by mutations of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase gene, Bianchi et al. showed that the lack of NETosis was associated with growth of Aspergillus nidulans (42). Since PAD4 is required for NETosis, Li et al. found that neutrophils from PAD4 knockout mice had limited abilities to kill Shigella flexneri when phagocytosis was inhibited demonstrating that killing of Shigella flexneri is mediated by NETs (21). NET components also can minimize the pathogenicity of microbes by inactivating their virulence factors. For example, NE found within NETs inactivates the virulence factors IpaB and Ipac A in S. flexneri making the invasion into the colonic mucosa and escape from phagocytic vacuoles more difficult (17, 75).

Detrimental Role of NETs in Sepsis

While NETs protect the host by limiting microbial growth and dissemination, excessive NETosis during sepsis can be detrimental to the host. Recent discoveries in in vitro experiments and animal models demonstrated the crucial role of NETs in the pathogenesis of intravascular thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and multiple organ dysfunction, all of which can increase morbidity and mortality in sepsis (1, 5).

NETs and Thrombosis in Sepsis

Systemic inflammation and release of proinflammatory cytokines during sepsis can result in abnormal activation of the coagulation system. Excessive thrombosis is normally prevented by concurrent activation of the anticoagulant pathways involving tissue factor pathway inhibitor, antithrombin, thrombomodulin, and protein C. Ongoing activation of the coagulation pathways during sepsis can overwhelm the anticoagulant systems leading to excessive intravascular thrombosis. Ultimately, overconsumption of platelets and coagulation proteins result in consumptive coagulopathy or DIC. Advanced DIC in septic patients usually presents as hemorrhage or multiple organ failure. Recent evidence in humans and dogs demonstrates that NETs and their components can exacerbate DIC by directly enhancing ex vivo clot formation, activating platelets, as well as, inhibiting anticoagulant pathways (76–78). Observational studies have shown that human or canine septic patients have aberrant amounts of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which can influence the dynamics of thrombus formation in several ways (12, 79). Studies in human patients found that cfDNA concentration in plasma from septic humans correlates positively with the rate and extent of thrombin generation (76). Oligonucleotides of double-stranded DNA-hairpins can bind to both factor XII and high molecular weight kininogen (HMWK) thus accelerating the activation of factor XII and prekallikrein, both critical in initiating the contact pathway of coagulation (80, 81). cfDNA not only impairs fibrinolysis by inhibiting tissue plasminogen activator, it also fortifies thrombus ultrastructure by creating a scaffold for the binding of red blood cells, platelets, fibrin and coagulation factors (82). Besides cfDNA, other NET components also exert procoagulant properties. Extracellular histones can induce platelet activation, platelet aggregation, and thrombin generation via platelet TLR2 and TLR4 (69). Extracellular histones also dose-dependently inhibit the generation of activated protein C in the presence of thrombomodulin (83). Neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G can proteolytically degrade tissue factor pathway inhibitor bound on human endothelial cells in vitro (84). The pathophysiological relevance of NETs-induced thrombosis has been further explored in septic mouse models. Intravital imaging of organs of LPS-treated mice demonstrated entrapment of cfDNA within pulmonary capillaries and post-capillary venules where formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates impedes blood flow in microvessels (85).

The Role of NETs in Sepsis Associated Multiple Organ Failure

Studies in human septic patients have shown that aberrant amounts of circulating NET components, including cfDNA and histones, are associated with poor outcome and multiple organ failure (86). cfDNA has a short half-life of 0–15 min in circulation due to enzymatic degradation by endogenous DNases and hepatic clearance. In sepsis, elevated levels of circulating cfDNA could be due to increased NETosis, apoptosis, necrosis or decreased clearance. Several in vivo studies in septic mouse models have shown improved survival and attenuation of organ injury by increasing cfDNA clearance using exogenous DNase (14, 15). The exact mechanisms of how cfDNA contributes to organ dysfunction are not clear. It is possible that degradation of cfDNA likely reduces the formation of microthrombi, and thereby, alleviating microvascular occlusion and tissue hypoxia. The immune modulatory effects of exogenous DNase seen in the septic mice also suggest that cfDNA may play a role in inflammation. Cell-free DNA from serum has been demonstrated to induce TNF-α mRNA expression in human monocytes and the telomeric sequence of cfDNA is potentially involved in the fine tuning of inflammation (87). Besides playing a key role in chromatin remodeling and gene transcription, histones, once released into the vascular space, can function as damage-associated molecular patterns. Extracellular histones can induce organ damage by functioning as a chemokine to promote proinflammatory cytokine release, induce apoptosis of leukocytes or nearby cells and incite direct cytotoxicity. Findings from in vitro studies of human endothelial cells suggest that extracellular histones may directly cause endothelial dysfunction by inducing cytotoxicity and increasing ROS to modulate nitric oxide production. Nitric oxide, generated by nitric oxide synthase, is important for maintaining vasodilation and normal tissue perfusion in health and disease (88, 89). Activation of endothelial cells further promote adhesion and transmigration of leukocytes to tissues. In mice, ischemic reperfusion injury can result in elevation of extracellular histones triggering the production of proinflammatory cytokines (90). in vivo histone injection into the renal arteries of mice induces acute kidney injury by directly causing renal tubular cell necrosis and expression of IL-6 and TNF-α via TLR2 and 4 (91).

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier resulting in increased permeability of the endothelial and epithelium leading to protein-rich edema and subsequent respiratory failure. Migration of neutrophils from the vasculature into the interstitium and bronchoalveolar space is a key feature of ARDS in sepsis. NETs in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collected from septic people and dogs with ARDS have recently been documented indicating that transmigrated neutrophils undergo NETosis in naturally occurring ARDS (56, 57, 72, 92). Serine proteases released via NETosis can have a direct pathophysiological role in the progression of ARDS. For example, proteinase-3, cathepsin G and NE can degrade surfactant D and A, both of which are important in the clearance of inflammatory cells and attenuation of residual inflammation (93, 94). in vitro studies have shown that NE increases alveolar epithelial permeability by altering the actin cytoskeleton of epithelial cells (95). Extracellular histones released via NETosis also may exacerbate neutrophil accumulation migration and elicit direct destruction of the alveolar epithelium leading to disruption of the alveolar permeability barrier.

Potential Therapeutic Targets

Since the outcome in sepsis depends heavily on early recognition and interventions, clinical assessment of NETs may serve as a valuable biomarker for the early diagnosis of sepsis. Direct visualization and quantification of NETs using immunofluorescence microscopy in clinical samples can be challenging since this technique is labor intensive and requires advanced training in microscopy. Preliminary studies using flow cytometry and advanced sequencing to quantify surrogates of NETosis like cfDNA, histones and nucleosomes in serum or plasma have shown promising results as these methods are more objective, reliable and repeatable than microscopy(96). Because overzealous production of NETs causes organ dysfunction and mortality, therapeutic interventions that target NET production or individual NET components present novel treatment strategies for sepsis. As mentioned previously, elevated levels of cfDNA released from NETosing neutrophils can have detrimental effects by activating the coagulation system and inflammation. One study showed that delayed systemic treatment of recombinant DNase in a mouse sepsis model reduces organ damage and bacterial dissemination, while early administration (2 h after cecal ligation) yields the opposite effects suggesting that NET-targeted therapy may be time-dependent (14). Interestingly, findings from a different study showed that early and concurrent treatment with DNase and antibiotics resulted in improved survival, reduced bacteremia and organ dysfunction(15). This indicates that combined therapies that incorporate conventional treatments such fluid therapy, antibiotics and NET-targeted drugs can potentially optimize treatment efficacy and outcome in clinical septic patients. To the authors' knowledge, there are no clinical trials to date evaluating the use of systemic DNase in clinical sepsis.

Treatment of PAD4 is a suitable therapeutic target because of its essential role in sepsis-mediated NETosis. In a mouse model of lupus, systemic treatment with the PAD4 inhibitor, BB-Cl-amidine, protects mice from developing NET-mediated vascular damage, endothelial dysfunction and kidney injury (97, 98). Sepsis models utilizing PAD4 knockout mice demonstrated that PAD4 deficiency improves survival and decreases the severity of organ dysfunction without exacerbating bacteremia (99, 100). Nonetheless, since the long-term physiologic consequences of systemic PAD4 inhibition are unknown, developing a suitable targeted therapy for PAD4 can be challenging.

Given its proinflammatory, cytotoxic and prothrombotic properties, citrullinated histone H3 (citH3) is a potential molecular target in sepsis. By neutralizing circulating citH3 in a septic mouse model, Li et al. found that blockade of citH3 significantly improves survival (101). Non-anticoagulant heparin, which binds to extracellular histones with minimal affinity to antithrombin, has been shown to reduce histone-mediated cytotoxicity, attenuate endotoxin-mediated lung injury and improve survival in septic mice (102). Although citrullinated histones have been found in canine and equine NETs, further studies are needed to characterize their effects in these species (Figure 1) (30). Activated protein C, a natural anticoagulant, cleaves extracellular histones abolishing the ability of histones to induce ex vivo platelet activation and potentially its cytotoxic and proinflammatory properties (69). However, large-scale randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of recombinant protein C for human septic patients did not demonstrate any clinical benefits of protein C, ultimately, leading to its withdrawal (103).

Because platelet activation and platelet-neutrophil interaction are crucial for NETosis to occur, antiplatelet therapy may attenuate NETosis and its detrimental effects in sepsis. Recent studies in human and canine platelets have shown that endotoxin-mediated platelet activation requires excessive production of eicosanoids like thromboxane A2 (104, 105). In a mouse model of endotoxin-triggered acute lung injury, pretreatment of mice with acetylsalicylic acid or aspirin, which prevents thromboxane A2 generation, decreases intravascular NET formation and the degree of lung injury (57). Inhibition of the platelet ADP receptor, P2Y12, may also attenuate platelet-neutrophil interaction and NETosis, as endotoxin-mediated platelet activation is dependent on ADP in canine and equine platelets (19). Interestingly, prehospital administration of antiplatelet therapy has been shown in several observational studies, to be associated with improved outcome in human clinical patients with sepsis(106, 107). A large-scale clinical trial evaluating the benefits of aspirin therapy in sepsis is currently underway (108).

Conclusion

Evidence in the literature indicates that NETosis is a highly conserved mechanism of innate immunity among numerous species. Research in mice and people demonstrates that the dysregulation of NETosis caused by sepsis can have detrimental effects resulting in inflammation, thrombosis and multiple organ failure. NETs may play a similar pathophysiological role in other species. NETosis and NET components are potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of sepsis.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the conception of this review. RL drafted it and FT and RL revised it critically. All authors approved the final version of this review.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; cfDNA, Cell free DNA; citH3, Citrullinated histone H3; Deoxyribonuclease, Dnase; HMGB-1, High mobility group box-1; NET, Neutrophil extracellular trap; NE, Neutrophil elastase; PAD, Peptidylarginine deiminase; PMA, Phorbal 12-myristate 13-acetate; ROS, Reactive oxygen species.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Morris Animal Foundation for funding the corresponding author (D15CA-907), as well as, the Center for Companion Animal Health (2016–24-F), the Oak Tree Racing Association and contributions by private donors (University of California, Davis, Center for Equine Health).

References

1. Kenney EM, Rozanski EA, Rush JE, Delaforcade-Buress AM, Berg JR, Silverstein DC, et al. Association between outcome and organ system dysfunction in dogs with sepsis: 114 cases (2003-2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2010) 236:83–7. doi: 10.2460/javma.236.1.83

2. Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, Townsend SR, Schorr CA, Beale R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med. (2015) 43:3–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000723

3. Babyak JM, Sharp CR. Epidemiology of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis in cats hospitalized in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2016) 249:65–71. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.1.65

4. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). J Am Med Assoc. (2016) 315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

5. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. (1996) 22:707–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751

6. De Gaudio AR, Rinaldi S, Chelazzi C, Borracci T. Pathophysiology of sepsis in the elderly: clinical impact and therapeutic considerations. Curr Drug Targets (2009) 10:60–70. doi: 10.2174/138945009787122879

7. Artero A, Zaragoza R, Camarena JJ, Sancho S, Gonzalez R, Nogueira JM. Prognostic factors of mortality in patients with community-acquired bloodstream infection with severe sepsis and septic shock. J Crit Care (2010) 25:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.12.004

8. Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. (2006) 6:173–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1785

9. Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Beneficial suicide: why neutrophils die to make NETs. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2007) 5:577–82. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1710

10. Keshari RS, Jyoti A, Dubey M, Kothari N, Kohli M, Bogra J, et al. Cytokines induced neutrophil extracellular traps formation: implication for the inflammatory disease condition. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e48111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048111

11. Delgado-Rizo V, Martinez-Guzman MA, Iniguez-Gutierrez L, Garcia-Orozco A, Alvarado-Navarro A, Fafutis-Morris M. Neutrophil extracellular traps and its implications in inflammation: an overview. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:81. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00081

12. Dwivedi DJ, Toltl LJ, Swystun LL, Pogue J, Liaw KL, Weitz JI, et al. Prognostic utility and characterization of cell-free DNA in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care (2012) 16:R151. doi: 10.1186/cc11466

13. Kaplan MJ, Radic M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol. (2012) 189:2689–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201719

14. Mai SH, Khan M, Dwivedi DJ, Ross CA, Zhou J, Gould TJ, et al. Delayed but not early treatment with DNase reduces organ damage and improves outcome in a murine model of sepsis. Shock (2015) 44:166–72. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000396

15. Czaikoski PG, Mota JM, Nascimento DC, Sonego F, Castanheira FV, Melo PH, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce organ damage during experimental and clinical sepsis. PLoS ONE (2016) 11:e0148142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148142

16. Yipp BG, Kubes P. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood (2013) 122:2784–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-457671

17. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science (2004) 303:1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385

18. Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. (2007) 176:231–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027

19. Li RHL, Ng G, Tablin F. Lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation in canine neutrophils is dependent on histone H3 citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminase. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2017) 193–194:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2017.10.002

20. Yipp BG, Petri B, Salina D, Jenne CN, Scott BN, Zbytnuik LD, et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat Med. (2012) 18:1386–93. doi: 10.1038/nm.2847

21. Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. (2010) 207:1853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239

22. Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, Fahey C, Yipp BG, Sibley CD, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. (2010) 185:7413–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675

23. Lippolis JD, Reinhardt TA, Goff JP, Horst RL. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation by bovine neutrophils is not inhibited by milk. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2006) 113:248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.05.004

24. Rebordao MR, Carneiro C, Alexandre-Pires G, Brito P, Pereira C, Nunes T, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formation by bacteria causing endometritis in the mare. J Reprod Immunol. (2014) 106:41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.08.003

25. Mori Y, Yamaguchi M, Terao Y, Hamada S, Ooshima T, Kawabata S. Alpha-Enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae induces formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287:10472–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280321

26. Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. (2007) 13:463–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1565

27. McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. (2012) 12:324–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011

28. Grinberg N, Elazar S, Rosenshine I, Shpigel NY. Beta-hydroxybutyrate abrogates formation of bovine neutrophil extracellular traps and bactericidal activity against mammary pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. (2008) 76:2802–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00051-08

29. Wardini AB, Guimaraes-Costa AB, Nascimento MT, Nadaes NR, Danelli MG, Mazur C, et al. Characterization of neutrophil extracellular traps in cats naturally infected with feline leukemia virus. J Gen Virol. (2010) 91:259–64. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014613-0

30. Li RHL, Ng G, Tablin F. Lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation in canine neutrophils is dependent on histone H3 citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminase. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2017) 193–194:29–37.

31. Pieterse E, Rother N, Yanginlar C, Hilbrands LB, Van Der Vlag J. Neutrophils discriminate between lipopolysaccharides of different bacterial sources and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:484. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00484

32. Neeli I, Khan SN, Radic M. Histone deimination as a response to inflammatory stimuli in neutrophils. J. Immunol. (2008) 180:1895–902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1895

33. Scharrig E, Carestia A, Ferrer MF, Cedola M, Pretre G, Drut R, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are involved in the innate immune response to infection with leptospira. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9:e0003927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003927

34. Hemmers S, Teijaro JR, Arandjelovic S, Mowen KA. PAD4-mediated neutrophil extracellular trap formation is not required for immunity against influenza infection. PLoS ONE (2011) 6:e22043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022043

35. Tripathi S, Verma A, Kim EJ, White MR, Hartshorn KL. LL-37 modulates human neutrophil responses to influenza A virus. J Leukoc Biol. (2014) 96:931–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A1113-604RR

36. Munoz-Caro T, Mena Huertas SJ, Conejeros I, Alarcon P, Hidalgo MA, Burgos RA, et al. Eimeria bovis-triggered neutrophil extracellular trap formation is CD11b-, ERK 1/2-, p38 MAP kinase- and SOCE-dependent. Vet Res. (2015) 46:23. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0155-6

37. Behrendt JH, Ruiz A, Zahner H, Taubert A, Hermosilla C. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation as innate immune reactions against the apicomplexan parasite Eimeria bovis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2010) 133:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.06.012

38. Silva LM, Caro TM, Gerstberger R, Vila-Vicosa MJ, Cortes HC, Hermosilla C, et al. The apicomplexan parasite Eimeria arloingi induces caprine neutrophil extracellular traps. Parasitol Res. (2014) 113:2797–807. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3939-0

39. Munoz-Caro T, Silva LM, Ritter C, Taubert A, Hermosilla C. Besnoitia besnoiti tachyzoites induce monocyte extracellular trap formation. Parasitol Res. (2014) 113:4189–97. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4094-3

40. Abi Abdallah DS, Lin C, Ball CJ, King MR, Duhamel GE, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun. (2012) 80:768–77. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05730-11

41. Reichel M, Munoz-Caro T, Sanchez Contreras G, Rubio Garcia A, Magdowski G, Gartner U, et al. Harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) PMN and monocytes release extracellular traps to capture the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Dev Comp Immunol. (2015) 50:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.02.002

42. Bianchi M, Hakkim A, Brinkmann V, Siler U, Seger RA, Zychlinsky A, et al. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood (2009) 114:2619–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606

43. Bruns S, Kniemeyer O, Hasenberg M, Aimanianda V, Nietzsche S, Thywissen A, et al. Production of extracellular traps against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in infected lung tissue is dependent on invading neutrophils and influenced by hydrophobin RodA. PLoS Pathog. (2010) 6:e1000873. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000873

44. Byrd AS, O'brien XM, Johnson CM, Lavigne LM, Reichner JS. An extracellular matrix-based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Candida albicans. J Immunol. (2013) 190:4136–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202671

45. Itakura A, McCarty OJ. Pivotal role for the mTOR pathway in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps via regulation of autophagy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2013) 305:C348–354. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00108.2013

46. Keshari RS, Verma A, Barthwal MK, Dikshit M. Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of ERK and p38 MAPK mediates PMA-induced NETs release from human neutrophils. J Cell Biochem. (2013) 114:532–40. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24391

47. Cote O, Clark ME, Viel L, Labbe G, Seah SY, Khan MA, et al. Secretoglobin 1A1 and 1A1A differentially regulate neutrophil reactive oxygen species production, phagocytosis and extracellular trap formation. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e96217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096217

48. Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol (2010) 191:677–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052

49. Konig MF, Andrade F. A critical reappraisal of neutrophil extracellular traps and netosis mimics based on differential requirements for protein citrullination. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00461

50. Yousefi S, Simon HU. NETosis - does it really represent nature's “Suicide Bomber”? Front Immunol. (2016) 7:328. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00328

51. Li Y, Liu B, Fukudome EY, Lu J, Chong W, Jin G, et al. Identification of citrullinated histone H3 as a potential serum protein biomarker in a lethal model of lipopolysaccharide-induced shock. Surgery (2011) 150:442–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.003

52. Lewis HD, Liddle J, Coote JE, Atkinson SJ, Barker MD, Bax BD, et al. Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol. (2015) 11:189–91. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1735

53. Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, Correll S, Li P, Wang D, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. (2009) 184:205–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072

54. Leshner M, Wang S, Lewis C, Zheng H, Chen XA, Santy L, et al. PAD4 mediated histone hypercitrullination induces heterochromatin decondensation and chromatin unfolding to form neutrophil extracellular trap-like structures. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:307. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00307

55. Rohrbach AS, Slade DJ, Thompson PR, Mowen KA. Activation of PAD4 in NET formation. Front Immunol (2012) 3:360. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00360

56. Liu S, Su X, Pan P, Zhang L, Hu Y, Tan H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are indirectly triggered by lipopolysaccharide and contribute to acute lung injury. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:37252. doi: 10.1038/srep37252

57. Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, Nguyen JX, Marques MB, Monestier M, et al. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:2661–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI61303

58. Sreeramkumar V, Adrover JM, Ballesteros I, Cuartero MI, Rossaint J, Bilbao I, et al. Neutrophils scan for activated platelets to initiate inflammation. Science (2014) 346:1234–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1256478

59. Etulain J, Martinod K, Wong SL, Cifuni SM, Schattner M, Wagner DD. P-selectin promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in mice. Blood (2015) 126:242–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-624023

60. Maugeri N, Campana L, Gavina M, Covino C, De Metrio M, Panciroli C, et al. Activated platelets present high mobility group box 1 to neutrophils, inducing autophagy and promoting the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Thromb Haemost. (2014) 12:2074–88. doi: 10.1111/jth.12710

61. Carestia A, Kaufman T, Rivadeneyra L, Landoni VI, Pozner RG, Negrotto S, et al. Mediators and molecular pathways involved in the regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation mediated by activated platelets. J Leukoc Biol. (2016) 99:153–62. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0415-161R

62. Diacovo TG, Roth SJ, Buccola JM, Bainton DF, Springer TA. Neutrophil rolling, arrest, and transmigration across activated, surface-adherent platelets via sequential action of P-selectin and the beta 2-integrin CD11b/CD18. Blood (1996) 88:146–57.

63. Konstantopoulos K, Neelamegham S, Burns AR, Hentzen E, Kansas GS, Snapp KR, et al. Venous levels of shear support neutrophil-platelet adhesion and neutrophil aggregation in blood via P-selectin and beta2-integrin. Circulation (1998) 98:873–82. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.9.873

64. Rossaint J, Herter JM, Van Aken H, Napirei M, Doring Y, Weber C, et al. Synchronized integrin engagement and chemokine activation is crucial in neutrophil extracellular trap-mediated sterile inflammation. Blood (2014) 123:2573–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-516484

65. Dyer MR, Chen QW, Neal MD, Vogel S. HMGB1 expression on platelet-derived microparticles promotes deep vein thrombosis. J. Am College Surg. (2016) 223:S153. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.06.331

66. Dyer MR, Chen QW, Haldeman S, Yazdani H, Hoffman R, Loughran P, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in mice is regulated by platelet HMGB1 through release of neutrophil-extracellular traps and DNA. Sci Rep. 8:2068 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20479-x

67. Zhou H, Deng MH, Liu YJ, Yang CX, Hoffman R, Zhou JJ, et al. Platelet HMGB1 is required for efficient bacterial clearance in intra-abdominal bacterial sepsis in mice. Blood Adv. (2018) 2:638–48. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017011817

68. Rossaint J, Kuhne K, Skupski J, Van Aken H, Looney MR, Hidalgo A, et al. Directed transport of neutrophil-derived extracellular vesicles enables platelet-mediated innate immune response. Nat. Commun. (2016) 7:13464. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13464

69. Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood (2011) 118:1952–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061

70. Buchanan JT, Simpson AJ, Aziz RK, Liu GY, Kristian SA, Kotb M, et al. DNase expression allows the pathogen group A Streptococcus to escape killing in neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. (2006) 16:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.039

71. Beiter K, Wartha F, Albiger B, Normark S, Zychlinsky A, Henriques-Normark B. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. (2006) 16:401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056

72. Li RHL, Johnson LR, Kohen C, Tablin F. A novel approach to identifying and quantifying neutrophil extracellular trap formation in septic dogs using immunofluorescence microscopy. BMC Vet Res. 14:210. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1523-z

73. Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? J Cell Biol. (2012) 198:773–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203170

74. Menegazzi R, Decleva E, Dri P. Killing by neutrophil extracellular traps: fact or folklore? Blood (2012) 119:1214–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364604

75. Weinrauch, Y, Drujan, D, Shapiro, SD, Weiss, J, and Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil elastase targets virulence factors of enterobacteria. Nature (2002). 417:91–4. doi: 10.1038/417091a

76. Gould TJ, Vu TT, Swystun LL, Dwivedi DJ, Mai SH, Weitz JI, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2014) 34:1977–84. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304114

77. Gould TJ, Vu TT, Stafford AR, Dwivedi DJ, Kim PY, Fox-Robichaud AE, et al. Cell-free DNA modulates clot structure and impairs fibrinolysis in sepsis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2015) 35:2544–53. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306035

78. Jeffery U, Levine DN. Canine neutrophil extracellular traps enhance clot formation and delay lysis. Vet Pathol. 55:116–23. doi: 10.1177/0300985817699860

79. Letendre JA, Goggs R. Measurement of plasma cell-free DNA concentrations in dogs with sepsis, trauma, and neoplasia. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (2017) 27:307–14. doi: 10.1111/vec.12592

80. Schmaier AH, McCrae KR. The plasma kallikrein-kinin system: its evolution from contact activation. J Thromb Haemost. (2007) 5:2323–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02770.x

81. Gansler J, Jaax M, Leiting S, Appel B, Greinacher A, Fischer S, et al. Structural requirements for the procoagulant activity of nucleic acids. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e50399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050399

82. Martinod K, Wagner DD. Thrombosis: tangled up in NETs. Blood (2014) 123:2768–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-463646

83. Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Xu J, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J Thromb Haemost. (2011) 9:1795–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04422.x

84. Steppich BA, Seitz I, Busch G, Stein A, Ott I. Modulation of tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor-1 by neutrophil proteases. Thromb Haemost. (2008) 100:1068–75. doi: 10.1160/TH08-05-0293

85. Tanaka K, Koike Y, Shimura T, Okigami M, Ide S, Toiyama Y, et al. in vivo characterization of neutrophil extracellular traps in various organs of a murine sepsis model. PLoS ONE 9:e111888 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111888

86. Hirose T, Hamaguchi S, Matsumoto N, Irisawa T, Seki M, Tasaki O, et al. Presence of neutrophil extracellular traps and citrullinated histone H3 in the bloodstream of critically ill patients. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e111755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111755

87. Zinkova A, Brynychova I, Svacina A, Jirkovska M, Korabecna M. Cell-free DNA from human plasma and serum differs in content of telomeric sequences and its ability to promote immune response. Sci. Rep. (2017) 7:2591. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02905-8

88. Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. (2009) 15:1318–21. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053

89. Perez-Cremades D, Bueno-Beti C, Garcia-Gimenez JL, Ibanez-Cabellos JS, Hermenegildo C, Pallardo FV, et al. Extracellular histones disarrange vasoactive mediators release through a COX-NOS interaction in human endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med. (2017) 21:1584–92. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13088

90. Allam R, Darisipudi MN, Tschopp J, Anders HJ. Histones trigger sterile inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Er J. Immunol. (2013) 43:3336–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243224

91. Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darisipudi MN, Mulay SR, Hagele H, Lichtnekert J, et al. Histones from dying renal cells aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2012) 23:1375–88. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111077

92. Yildiz C, Palaniyar N, Otulakowski G, Khan MA, Post M, Kuebler WM, et al. Mechanical ventilation induces neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Anesthesiology (2015) 122:864–75. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000605

93. Rubio F, Cooley J, Accurso FJ, Remold-O'donnell E. Linkage of neutrophil serine proteases and decreased surfactant protein-A (SP-A) levels in inflammatory lung disease. Thorax (2004) 59:318–23. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.014902

94. Cooley J, McDonald B, Accurso FJ, Crouch EC, Remold-O'donnell E. Patterns of neutrophil serine protease-dependent cleavage of surfactant protein D in inflammatory lung disease. J Leukoc Biol. (2008) 83:946–55. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007684

95. Peterson MW, Walter ME, Nygaard SD. Effect of neutrophil mediators on epithelial permeability. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (1995) 13:719–27. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576710

96. Lee KH, Cavanaugh L, Leung H, Yan F, Ahmadi Z, Chong BH, et al. Quantification of NETs-associated markers by flow cytometry and serum assays in patients with thrombosis and sepsis. Int J Lab Hematol. (2018) 40:392–9. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12800

97. Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, O'dell AA, Yalavarthi S, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. (2013) 123:2981–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI67390

98. Knight JS, Subramanian V, O'dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis. (2015) 74:2199–206. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205365

99. Martinod K, Fuchs TA, Zitomersky NL, Wong SL, Demers M, Gallant M, et al. PAD4-deficiency does not affect bacteremia in polymicrobial sepsis and ameliorates endotoxemic shock. Blood (2015) 125:1948–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587709

100. Biron BM, Chung CS, Chen Y, Wilson Z, Fallon EA, Reichner JS, et al. PAD4 deficiency leads to decreased organ dysfunction and improved survival in a dual insult model of hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. J Immunol. (2018) 200:1817–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700639

101. Li Y, Liu Z, Liu B, Zhao T, Chong W, Wang Y, et al. Citrullinated histone H3: a novel target for the treatment of sepsis. Surgery (2014) 156:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.009

102. Wildhagen KC, Garcia De Frutos P, Reutelingsperger CP, Schrijver R, Areste C, Ortega-Gomez A, et al. Nonanticoagulant heparin prevents histone-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro and improves survival in sepsis. Blood (2014) 123:1098–101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-514984

103. Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Lathyris D, Cardona AF. Human recombinant activated protein C for severe sepsis. Cochr Database Syst Rev. (2012) CD004388. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004388

104. Li RHL, Nguyen N, Tablin F. Dog platelets express functional TLR4: platelet agonists upregulate platelet surface TLR4 and facilitate LPS-induced platelet activation in dogs (abstract). J Vet Emerg Crit Care (2017) 26, S1–S15. doi: 10.1111/vec.12645

105. Nocella C, Carnevale R, Bartimoccia S, Novo M, Cangemi R, Pastori D, et al. Lipopolysaccharide as trigger of platelet aggregation via eicosanoid over-production. Thromb Haemost. (2017) 117:1558–70. doi: 10.1160/TH16-11-0857

106. Eisen DP, Reid D, McBryde ES. Acetyl salicylic acid usage and mortality in critically ill patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:1761–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246b9df

107. Chen W, Janz DR, Bastarache JA, May AK, O'neal HR. Jr, Bernard GR, et al. Prehospital aspirin use is associated with reduced risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients: a propensity-adjusted analysis. Crit Care Med. (2015) 43:801–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000789

Keywords: citrullinated histones, acute respiratory distress syndrome, veterinary critical care, immunothrombosis, platelet-neutrophil interaction

Citation: Li RHL and Tablin F (2018) A Comparative Review of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Sepsis. Front. Vet. Sci. 5:291. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00291

Received: 27 August 2018; Accepted: 31 October 2018;

Published: 28 November 2018.

Edited by:

Soren R. Boysen, University of Calgary, CanadaReviewed by:

Iain Keir, Allegheny Veterinary Emergency Trauma and Specialty, United StatesJo-Annie Letendre, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, United States

Copyright © 2018 Li and Tablin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ronald H. L. Li, cmhsaUB1Y2RhdmlzLmVkdQ==

Ronald H. L. Li

Ronald H. L. Li Fern Tablin2

Fern Tablin2