- Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

The euclidean path integral remains, in spite of its familiar problems, an important approach to quantum gravity. One of its most striking and obscure features is the appearance of gravitational instantons or wormholes. These renormalize all terms in the Lagrangian and cause a number of puzzles or even deep inconsistencies, related to the possibility of nucleation of “baby universes.” In this review, we revisit the early controversies surrounding these issues as well as some of the more recent discussions of the phenomenological relevance of gravitational instantons. In particular, wormholes are expected to break the shift symmetries of axions or Goldstone bosons non-perturbatively. This can be relevant to large-field inflation and connects to arguments made on the basis of the Weak Gravity or Swampland conjectures. It can also affect Goldstone bosons which are of physical interest in the context of the strong CP problem or as dark matter.

1. Introduction

It is reasonable to think that a consistent theory of quantum gravity has to allow for topology change. Indeed, if the euclidean path integral has any relevance at all, then it appears unnatural to forbid 4-manifolds with non-trivial topology. After all, they are locally indistinguishable from ℝ4. Further evidence in favor of topology change comes, for example, from string theory: String interactions and loops rely entirely on topology change in the worldsheet theory, the latter being a relatively well-understood examples of 2d quantum gravity. In addition, 10d supergravity theories with their stringy UV completion involve controlled examples of topology change. These occur if one dynamically moves through special loci in Calabi-Yau moduli space, e.g., through a conifold point.

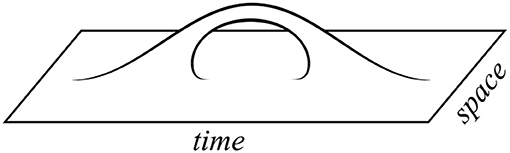

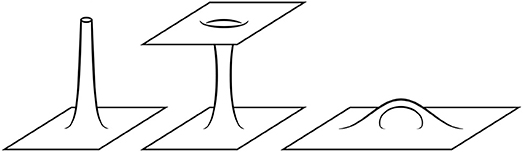

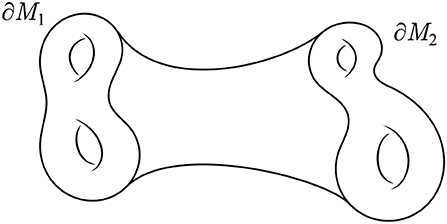

However, our point of departure will be more simple minded, focusing on topology change in 4d effective quantum gravity. Consider the evolution of 3d spatial manifolds in time. It is natural to think that in the course of this evolution an ℝ3 can transit to an ℝ3 plus an S3 “baby universe,” which subsequently reunite becoming again an ℝ3 (cf. Figure 1). This can be viewed as a tunneling transition, which gains quantitative support from the existence of a corresponding euclidean solution—the Giddings-Strominger wormhole (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a). While topology change has been discussed before (Wheeler, 1955; Regge, 1961; Hawking, 1978, 1987, 1988; Ellis et al., 1984; Lavrelashvili et al., 1987), the Giddings-Strominger solution (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a) and especially the application to the cosmological constant problem suggested by Coleman (1988c) led to an enormous spike of activity (Coleman, 1988a; Giddings and Strominger, 1988b, 1989b; Grinstein and Wise, 1988; Hawking and Laflamme, 1988; Lee, 1988; Rubakov, 1988; Abbott and Wise, 1989; Brown et al., 1989; Burgess and Kshirsagar, 1989; Choi and Holman, 1989; Coleman and Lee, 1989, 1990a,b; Duff, 1989; Fischler and Susskind, 1989; Gilbert, 1989; Grinstein, 1989; Grinstein and Hill, 1989; Klebanov et al., 1989; Nielsen and Ninomiya, 1989; Polchinski, 1989b; Preskill, 1989; Preskill et al., 1989; Rey, 1989; Tamvakis, 1989; Carlip and De Alwis, 1990; Grinstein and Maharana, 1990; Grinstein et al., 1990; Hawking, 1990a,b, 1991a,b; Hawking and Page, 1990; Tamvakis and Vayonakis, 1990; Lyons and Hawking, 1991; Linde, 1992; Twamley and Page, 1992; Kaplunovsky, unpublished; see Coleman et al., 1991 for an early overview).

As part of these investigations, severe problems in the resulting picture of a macroscopic spacetime surrounded by baby universes were uncovered (Fischler and Susskind, 1989; Kaplunovsky, unpublished; Polchinski, 1989b; Hawking, 1990b). While the interest has then subsided, important results have continued to appear over the years (Kallosh et al., 1995; Nirov and Rubakov, 1995; Barcelo et al., 1996; Gibbons et al., 1996; Rubakov and Shvedov, 1996a,b; Green and Gutperle, 1997; Rey, 1999; Gutperle and Sabra, 2002; Bergshoeff et al., 2004, 2005; Maldacena and Maoz, 2004; Collinucci, 2005; Bergshoeff et al., 2006; Dijkgraaf et al., 2006; Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b; Bergman and Distler, 2007; Chiodaroli and Gutperle, 2009a,b; Cortes and Mohaupt, 2009; Mohaupt and Waite, 2011; Betzios et al., 2018). It has, however, neither been shown that wormholes and baby universe are unphysical nor has a satisfactory overall picture been developed. Thus, euclidean wormholes or gravitational instantons have remained a lurking fundamental issue in our understanding of quantum gravity. We emphasize that this issue is not easily dismissed as a problem of the UV completion. On the contrary, large wormholes tend to be as puzzling as small ones, such that the problems appear to be there even in the low-energy effective theory1.

More recently, the interest in wormholes has been renewed in the context of large-field inflation, axion-physics, and the widespread excitement (see e.g., Cheung and Remmen, 2014; Brown et al., 2015, 2016; de la Fuente et al., 2015; Hebecker et al., 2015; Heidenreich et al., 2015; Montero et al., 2015; Rudelius, 2015; Bachlechner et al., 2016; Choi and Kim, 2016; Junghans, 2016; Kaloper et al., 2016; Kappl et al., 2016; Kooner et al., 2016; Klaewer and Palti, 2017) about the Weak Gravity Conjecture and the Landscape/Swampland paradigm (Vafa, 2005; Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007a; Ooguri and Vafa, 2007, 2016; Brennan et al., 2017). This is natural since wormholes have the potential to break global symmetries, such as the shift symmetry of the axion. In addition, they may be considered the macroscopic, gravitational version of instantons in pretty much the same way as charged black holes are the macroscopic version of charged particles. Thus, the interest in the Weak Gravity Conjecture and its implications for phenomenology naturally lead to an enhanced interest in (euclidean) wormholes (Hebecker et al., 2015; Montero et al., 2015; Heidenreich et al., 2016; Harlow, 2016; Alonso and Urbano, 2017; Hebecker et al., 2017; Hertog et al., 2017; Ruggeri et al., 2018; Shiu and Staessens, 2018).

Our review is motivated in several ways: First, as just explained, it is timely to reconsider the wormhole issue in view of the growing interest in generic quantum gravity constraints on effective field theories. Second, the unsolved problems from the 90's are, in our opinion, as important as ever. Additionally, one of the main phenomenological targets in the otherwise rather theory-driven wormhole debate have always been axions2. Since axions are becoming more and more central in Beyond-the-Standard-Model research, scrutinizing their generic features is of particular importance. Finally, we believe that the post-90's theoretical developments of AdS/CFT, holography and (gravitational) entanglement have not yet been fully exploited in the context of euclidean wormholes. Thus, significant technical progress may be expected concerning the fundamental issues raised by those objects.

In the long run, we can think of two different outcomes: On the one hand, wormhole effects may turn out to be absent from certain theories, in particular from the 4d quantum gravity describing the real world. This would solve many puzzles. Advocates of this possibility have to address a number of questions. In particular, what is the specific mechanism behind this “wormhole censorship”? As we will argue, it appears difficult to imagine such a mechanism which would not also forbid topology change in general. This, of course, would be a radical step. Related to this: How can we forbid wormholes in 4d while maintaining their central role in the 2d quantum gravity known as string theory? Furthermore, if wormholes are forbidden, what is the generic gravitational effect responsible for the breaking of global shift symmetries of axions? On the other hand, if wormholes exist, they represent a radical departure from standard interpretations of effective field theories. As we will describe, the correct understanding of their effects requires solving numerous fundamental problems. In the hope that these questions can be successfully addressed in the near future, we consider it worthwhile summarizing the state of the art and describing the main puzzles and open issues posed by wormholes.

We start in section 2 by recalling how instantons (of either gauge-theoretic or stringy nature) generate a potential for any scalar to which they are minimally coupled. We then describe the famous Giddings-Strominger solution (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a), which corresponds to a throat with cross section S3, connecting two points in ℝ4 (cf. Figure 1). The throat is supported by H3 flux, and the dual of H3 is the field strength of an axion. This axion then naturally couples to the two wormhole ends, which can locally be interpreted as instanton and anti-instanton. The axionic shift symmetry is potentially broken by a “dilute gas” of such wormholes. We also briefly comment on dilatonic instantons as they generically arise in string theory, emphasizing that it has by now been established that wormhole solutions do really arise in string-derived models (Tamvakis, 1989; Bergshoeff et al., 2005; Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b; Hertog et al., 2017).

Next, in section 3, we discuss how the low-energy effective action is corrected by wormholes (of Giddings-Strominger type and, more generally, by any “spacetime handles” of the form displayed in Figure 1). We follow the pioneering work by Coleman (1988c) and Preskill (1989). Crucially, in contrast to instantons, wormholes induce a bilocal action, which has the potential to break locality or even quantum coherence. However, the bilocal correction can be turned into a local one by introducing appropriate auxiliary integration variables (α parameters). Alternatively, this can be captured by thinking in terms of a “state of baby universes,” the absorption and emission of which is described by operators a† and a. In this language, the α parameters are simply the eigenvalues of . If the (infinitely many) α parameters take definite and not excessively large values, effective 4d locality and the dilute gas approximation are maintained. However, exact predictivity for Lagrangian parameters on the basis of some underlying microscopic theory is lost.

Section 4 is devoted to phenomenological applications. The early literature focuses on the indeterminacy of effective coupling constants. In particular, Coleman argued that the cosmological constant is statistically driven to zero value by the distribution of α parameters and their interplay with large-scale 4d gravity (Coleman, 1988c). The violation of axionic shift symmetries and other global symmetries has also been studied from the beginning (see e.g., Rey, 1989). More recently, the shift symmetry of a large-f axion has been discussed in the context of wormholes and their interplay with the Weak Gravity Conjecture (Hebecker et al., 2015; Montero et al., 2015; Heidenreich et al., 2016). We review some of this discussion, pointing out in particular difficulties in making strong, generic arguments against large-field axionic inflation (Hebecker et al., 2017). Additionally, we discuss possible wormhole effects on axions with f < MP (including but not limited to the QCD axion) following (Alonso and Urbano, 2017). These may be relevant to ultralight dark matter, axion stars and black hole superradiance.

Open conceptual issues are the main subject of section 5. There are many of those, making the whole subject interesting but at the same time very difficult. We start with the FKS catastrophe (Fischler and Susskind, 1989; Kaplunovsky, unpublished), which turns Coleman's cosmological constant calculation into an argument for an overdensity of large wormholes. We go on to briefly discuss the generic problems of euclidean quantum gravity and, in particular, the negative-mode problems possibly affecting the Giddings-Strominger solution (Rubakov and Shvedov, 1996a; Alonso and Urbano, 2017; Hertog et al., 2017). Finally, we discuss the quantum cosmology involving macroscopic universes and a baby universe state. This can be relatively well undestood in a 1d toy model, but becomes already rather complicated in 2d quantum gravity. The latter case has of course received particular attention since its “large universe” may be the worldsheet of a fundamental string, while the baby universe state is represented by the dynamical target space of string theory. Finally, we analyse the Wheeler-DeWitt perspective as well as issues arising in the AdS/CFT paradigm. We conclude in section 6.

2. From Instantons to Wormholes

In this section we describe the simplest wormhole configurations, extrema of the euclidean action of Einstein gravity coupled to axionic fields (and possibly dilatons). We start with a brief description of the related but much better understood case of flat spacetime, where instantons arise as euclidean saddle points of gauge theories.

2.1. Instantons

Let us start by recalling the familiar case of a 4d gauge theory with

For simplicity the gauge group is taken to be SU(2). The euclidean path integral necessarily involves certain finite action configurations (instantons) for which the field strength is non-zero in the vicinity of some point and falls off quickly as |x − x0| → ∞. Moreover, the value of

is integer, with n = ±1 characterizing a single instanton or anti-instanton (see e.g., Coleman, 1979; Vainshtein et al., 1982; Tong, 2005; Bianchi et al., 2008; Vandoren and van Nieuwenhuizen, 2008). The minimal action for such n = ±1 configurations is

The underlying solutions have 8 moduli: the components of x0, a size modulus, and three zero modes associated to global SU(2) transformations.

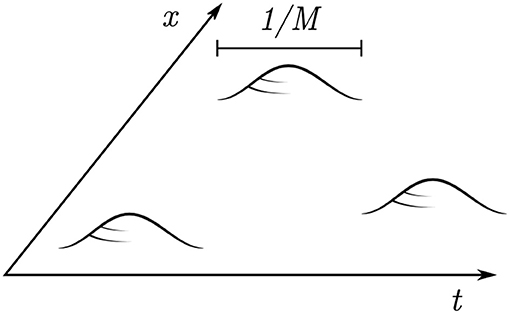

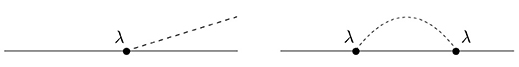

In calculating the partition function of the theory, one has to sum over any number of such instanton or anti-instanton configurations and integrate over all their moduli. This can be done very explicitly (see below) in the so-called dilute instanton gas approximation, i.e., assuming that the regions where F is significantly non-zero are much smaller than their distance. Unfortunately, this clashes with the fact that a large contribution comes from very extended instantons, making the calculation e.g., in the practically interesting case of QCD non-trivial. A relevant toy model can however be obtained by Higgsing the gauge theory at M≫Λ, with Λ the confinement scale. The largest instantons now have size ~1/M and the dilute gas approximation can be parametrically controlled (cf. Figure 2).

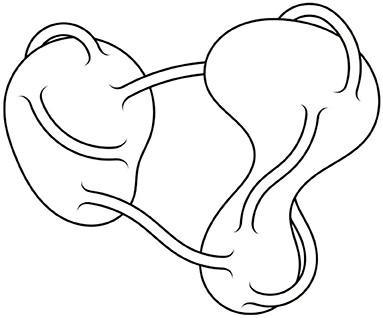

Another equally familiar case is that of stringy or exotic instantons. To recall this case, start with the toy model of a 5d gauge theory on ℝ1, 3×S1. Clearly, if charged particles exist, this theory has tunneling processes in which a particle-anti-particle pair emerges from the vacuum and annihilates after passing around the S1 in opposite directions (cf. Figure 3). In the euclidean theory, this corresponds to a 0-brane wrapped on the S1 at some point . The generalization to string compactifications with appropriate Dp-branes (or Ep-branes, with “E” for euclidean) wrapped on (p+1)-cycles of the compact space is obvious (for reviews see e.g., Akerblom et al., 2007; Blumenhagen et al., 2009; Ibanez and Uranga, 2012).

Figure 3. Euclidean brane instanton as particle-antiparticle fluctuation wrapping the compact space.

Crucially, in both of the above examples a shift symmetric, periodic scalar coupling to the instantons is naturally expected to be present. In the first case, it is the analog of the QCD axion, coupling through

In the second case, it is the “Wilson-line” scalar descending from the 5d gauge field or, more generally, the 4d scalar descending from the Ramond-Ramond Cp+1-form field dimensionally reduced on the appropriate (p+1) cycle.

For us, the above prelude serves only to motivate the following model theory of generic (or fundamental) instantons: It is defined by the partition function

which can of course be extended to a prescription for calculating Greens functions in the usual way. In this theory, the instantons are fundamental, zero-dimensional objects coupling to the axion-like field (just axion from now on) in the mathematically natural way: The axion is interpreted as a zero-form gauge potential which simply has to be evaluated at the position of the charged object (in the stringy language a D(−1) brane)3. Furthermore, ϕ stands for all other fields in the model and SI is the instanton action. It arises (together with the typical instanton scale M) as the tunneling suppression factor , which can also be interpreted as the instanton density.

Famously, the instanton and anti-instanton sum exponentiate and the two exponents involving θ combine to produce a cosine. This gives

We emphasize that, apart from possible corrections to the dilute gas approximation, this is exact. Furthermore, it can be easily extended to situations in which the instantons couple, in addition to the necessary topological coupling to the zero-form θ, to other fields. For example, SI may depend on the background values of some of the degrees of freedom denoted by ϕ.

2.2. Giddings-Strominger Solution

At the end of the previous section, we advertised the point of view that instantons coupled to axions are a limiting case of the general concept of a p-form gauge theory: In this case p = 0 and the charged object is zero-dimensional. By analogy to the gauge theory, one then expects the existence of objects akin to black branes. In other words, there might exist purely gravitational solutions charged under the axion which represent the continuation of instantons into the high-mass (or high-tension) regime.

An object which fulfills such an expectation at least partially is the Giddings-Strominger wormhole (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a), sometimes also referred to as a gravitational instanton. It is based on the euclidean action (MP = 1)

Equivalently, one can use the dual formulation in terms of a 2-form gauge theory with field strength H3 = dB2:

At the classical level, the duality relation is simply H = f2*dθ. However, the equivalence of the two theories extends, of course, to the full quantum systems. To see this, the dualization must be done under the path integral and care must be taken to get the signs of the kinetic terms right. The outcome is that, both in the euclidean and in the lorentzian versions, the fields have standard (non-ghostlike) kinetic terms on both sides of the duality (see Burgess and Kshirsagar, 1989; Collinucci, 2005; Bergshoeff et al., 2006; Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b; Hebecker et al., 2017 for details). The wormhole solution to be discussed momentarily exists only in the euclidean theory, but both in the 0-form and 2-form formulation. However, while the B2/H3 fields are real, the corresponding values of θ/dθ are imaginary.

Now, the relevance of an “instanton-like” euclidean solution is, of course, that it defines a saddle point of the path integral and hence a very specific, easily quantifiable contribution to the partition function. For the B2 path integral, the Giddings-Strominger saddle point is then right in the standard integration domain, i.e., “on the real axis” of field space. By contrast, in the θ path integral the corresponding saddle point is “on the imaginary axis,” requiring the deformation of the contour and raising the question whether such complex saddles contribute. Complex saddles are certainly known to contribute in certain cases (for a toy model relevant to the present setting see Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b). Thus, while we favor the (real) B2 formulation for obvious reasons in what follows, there is nothing wrong in principle with the θ formulation4.

After these preliminaries, let us describe the solution (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a). It can be motivated by starting from a field theory instanton and including gravitational backreaction: If an instanton couples to an axion θ, the dual theory carries non-zero 3-form flux,

on any sphere containing n instantons (or an instanton of charge n). Placing the instanton(s) at the origin and assuming spherical symmetry, it is immediately clear that one must have

Here ϵ is defined as the volume form of S3 in the description of ℝ4 as .

The above H automatically satisfies the Bianchi identity dH = 0 and the equation of motion d*H = 0 (for any spherically symmetric metric). It induces a non-zero energy momentum tensor and the corresponding Einstein equation is solved by

Here denotes the round metric on the unit sphere.

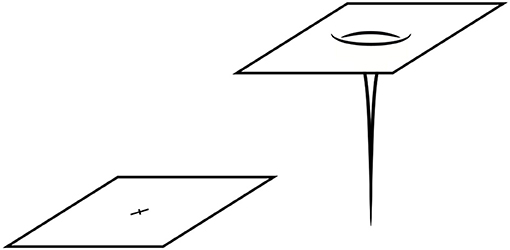

This geometry is asymptotically flat for r → ∞ and has a coordinate singularity at . The space given by restricting r∈[r0, ∞) forms what is often termed a semiwormhole (see Figure 4). Gluing two such solutions at the 3-spheres defined by r = r0, one obtains a smooth wormhole connecting two flat universes (see Figure 4). A topologically distinct, approximate solution can be obtained if the two asymptotically flat regions of Figure 4 are interpreted as distant parts of the same universe—cf. Figure 4. One then has a wormhole joining two regions of the same large universe. This becomes exact in the limit that the two wormhole ends are infinitely far apart.

Figure 4. Wormholes: A semiwormhole (Left), a wormhole connecting two distinct large asymptotically flat universes (Center) and a wormhole on a single universe (Right).

The wormhole action is particularly easy to compute using the trace of the Einstein equation:

Notice the factor 2 appearing because a wormhole consists of two solutions of the form of (11), each restricted to r > r0.

The most straightforward interpretation of this is as follows: Suppressed by an overall factor exp(−Sw), the partition function includes processes in which an S3 baby universe supported by H3-flux “bubbles off” at some space-time point x and is absorbed later on at y (x, y∈ℝ4). From the low-energy perspective, this is equivalent to an instanton (of charge n and action Sw/2~|n|/f) at x and a corresponding anti-instanton at y. Calculational control in semiclassical gravity requires . This should then give rise to a cosine potential for θ and further instanton-induced operators. It has, however, been argued that, in contrast to the instantonic situation, no such potential is induced because of the unavoidable pairing of instanons and anti-instantons (Heidenreich et al., 2016). Counterarguments have been given (Hebecker et al., 2017), based essentially on the intuition that local physics is ignorant of the overall constraint on instantons vs. anti-instantons in a very large space-time (recall that the action stays finite as |x−y| → ∞). However, this debate is overshadowed by a much deeper issue which will permeate the rest of this review: Once one allows for wormholes, one has effectively allowed for baby-universes propagating between points x and y. But then such baby universes must also be allowed to be part of the initial and final states of any process. More generally, there exits a “baby-universe state” in addition to our space-time and any wormhole effects (such as the naive cosine potential) depend on it.

2.3. Dilatonic Wormholes

Before coming to the physical effects of wormholes and baby universes, we want to briefly comment on generalizations of the Giddings-Strominger solution which involve a dilaton (Giddings and Strominger, 1988a, 1989b; Bergshoeff et al., 2006; Heidenreich et al., 2016; Hebecker et al., 2017). This is important since such dilatons are always present in the simplest stringy models allowing for wormholes.

Consider an action in which the axionic kinetic term depends on a further massless scalar field ϕ,

or equivalently

with ≡1/(3!). As before, spherical symmetry ensures that the equation of motion for H is automatically satisfied. A new, non-trivial differential equation for the radial profile of ϕ arises. Remarkably, the differential equation for grr (the only non-trivial part of the Einstein equation) decouples and the metric (11) remains a solution5. We will not discuss the solution ϕ(r) in any detail. It is, however, interesting to note that, switching from H3/B2 to dθ/θ for the moment, the common trajectory {ϕ(r), θ(r)} describes a geodesic in field space. This generalizes to the case of several axionic and several non-axionic scalars (cf. Footnote 5 and Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b).

Motivated by stringy and supergravity examples, we now restrict attention to the special case

Without loss of generality one can assume β≥0. Three different classes of solutions can be distinguished: First, as long as , the Giddings-Strominger wormhole continues to exist (metric of 11 with C < 0). This is the case of our main interest. Second, there is the extremal gravitational instanton, corresponding to C = 0. The geometry is a flat space-time with the origin removed, but ϕ diverges as one approaches r = 0. Third, there are “cored gravitational instantons,” corresponding to C < 0. In this case one has a curvature singularity at r = 0 (cf. Figure 5). The last two cases have the significant drawback that they are not fully controlled within the low-energy effective theory and we will hence not discuss them further (see however Bergshoeff et al., 2006; Heidenreich et al., 2016; Hebecker et al., 2017).

In the simplest (usually highly supersymmetric) string compactifications, axions are always accompanied by a dilatonic scalar or saxion, as above. However, the simplest models do not allow for . Naively, one may then hope that wormholes do not arise in consistent theories of quantum gravity. But it turns out that the problem with the allowed β range can be overcome (Tamvakis, 1989; Bergshoeff et al., 2005; Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007b; Hertog et al., 2017). The underlying idea is simple: A wormhole can be charged under several axions, each with its own saxion with a certain β. The trajectory which the solution follows in the saxionic field space involves all the axions and can be characterized by a single effective β. The latter can be in the desired range even if the β-values of the ingredients were not6. Thus, one can by now be certain that Giddings-Strominger wormholes exist in the euclidean version of supergravity theories coming from string theory. This makes all the puzzles to be discussed below even more troubling7.

3. The Effect of Wormholes

Two results of the previous section are essential for what follows. First, a dilute gas of instantons can be resummed (or “integrated out”) to obtain a correction to the effective action. Second, a very similar contribution to the path integral arises in gravitational theories with an axion. The objects to be summed over are wormholes or gravitational instantons. The main novelty is that they couple to the low-energy degrees of freedom (including the background metric) at two spacetime points rather than just at one. We now want to discuss the correction to the effective action arising in this second case following (Coleman, 1988c; Preskill, 1989; Coleman and Lee, 1990b). We note that, while the specific Giddings-Strominger solution discussed above may be the simplest and best understood euclidean wormhole, the following analysis does not rely on any of its details. What matters is that the euclidean path integral includes contributions from topologies like that of Figure 4 (on the right). All that we will use is that they are exponentially suppressed by a sufficiently large euclidean action and that the coupling to soft field modes occurs at two uncorrelated points (Hawking, 1988, 1990b).

3.1. The Bilocal Action

We begin with a heuristic derivation of the bilocal action which captures the effect of wormholes at the semi-classical level. For this, we first recall the field theoretic partition function with instantons, Equation (5), and restrict it to the one-instanton sector for notational simplicity:

Here the prefactor M4 has been reabsorbed in the instanton action. (To be careful, one should then either work in Planck units or at least choose x dimensionless.)

The above is unnecessarily explicit in that θ has been separated from all the other fields ϕ. At the same time, it is oversimplified in that only the dependence of the instanton action on θ has been kept: SI[θ]≡SI+iθ. A more general version, in which θ is just one of the many fields denoted by ϕ, reads

Here SI[x, ϕ] is the single-instanton tunneling action for the space-time point x in a background field ϕ. It is clear that obtaining this action in a concrete model is highly non-trivial: One would have to find the analog of the well-known instanton or wrapped-euclidean-brane solution in an, in general non-constant, background of all fields in the theory. However, we are satisfied with an approximation: the fields ϕ are restricted to be soft relative to the instanton scale M. The action can then be expanded in terms of local operators:

Here SI is the instanton action on the unperturbed background, say at ϕ≡0. With this, the transition to wormholes is simple.

Indeed, the wormhole analog of (18) is

Here ∫Dg stands for the integral over all soft (relative to the wormhole size) metrics on the topologically trivial background universe into which the wormhole is inserted. In addition, ϕ stands for all further fields, including the axion or the dual 2-form8. As before, appealing to our restriction to soft fields and metric configurations, the wormhole action can be written as a series of local operators at x and y:

For simplicity terms depending on a non-trivial metric background have not been displayed. It is clear that such terms, involving various curvature invariants at x and at y as well as products thereof, will also be present. The crucial novelty compared to the instanton case is that one is dealing with a double functional Taylor expansion and that products of local operators involving all fields will in general arise. Thus, one generically has the bilocal expression

or, equivalently,

In the last expression, the exponential has been expanded and the suppression factor exp(−Sw) has been absorbed in the new coefficients Δij:

Finally, one inserts (23) in (20) and writes down analogous expressions for any number of wormholes. In doing so, the dilute gas approximation is used, i.e., that typical distances between wormhole ends are much larger than the wormhole diameter. The sum exponentiates, exactly as in the instanton case, giving

with the bilocal action

3.2. Local Action Involving αParameters

Following Coleman (1988c) and Preskill (1989), one can give the action I a local form at the expense of introducing a set of auxiliary parameters αi. Up to some irrelevant normalization factor, one has

It is natural to write the original action S of our physical system using the basis of local operators as in the wormhole action I above:

Here λi are the coupling constants. For example, λ1, λ2, and λ3 could be the cosmological constant, the coefficient of the Einstein-Hilbert term, and of the R2-term, respectively. To minimize the notational complexity, we suppress the dependence on the non-metric fields ϕ here and below. Of course, all of the above holds with as many further fields as one needs.

Comparing (27) and (28), one sees that the effect of wormholes amounts to shifting the coupling constants of the original action: λi → λi−αi. Put differently, one can use the “shifted” action S[g; λ−α], remembering of course to integrate over the α parameters. The partition function with wormhole effects included (see Equation 25 and recall that we suppress ϕ) now reads

with the gaussian weighting factor. In the above, we also use the somewhat sloppy notation Dα for the integration over all αi, in spite of the fact that the index i is discrete.

In the last expression in (29), one recognizes the familiar partition function without wormholes inside the square brackets. The wormhole effect is reduced to shifting the coupling constants of that theory by αi. Since these α parameters are constants in space and time, one can take the point of view that they simply have to be measured and no relevance should be ascribed to the gaussian weight factor governing their distribution. By contrast, one may argue that statistical predictions for their values are possible, which of course involves this weight factor. This is a multiverse-type situation, discovered (and discussed by many authors) long before the string theory multiverse entered the stage.

3.3. Baby Universes

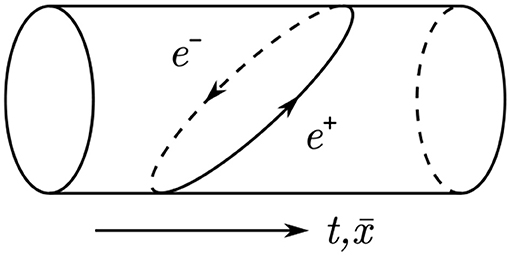

The physics behind α parameters becomes more lucid if one thinks of the wormholes in terms of S3 baby universes which are emitted and absorbed by our macroscopic space-time (left hand side of Figure 6). To derive the corresponding formulae, one considers the situation with a single operator and hence a single α parameter for notational simplicity. Equation (27) then reads

obtained after rescaling and introducing the normalization factor for later convenience.

Figure 6. The effective action considered as an amplitudes (Left) and an amplitude including semiwormholes (Right).

Equation (30) can be viewed as a power series in (x) encoding the sum of process in which baby universes are created and annihilated at locations corresponding to the various values taken by x. All of this has of course to be inserted under the Dg integral over soft background metrics. To make this manifest, one defines baby universe creation and annihilation operators a†, a satisfying the usual commutation relation [a, a†] = 1. The state with no baby universes |0〉 is referred to as the baby universe vacuum. The normalized state with n baby universes is then given by

The analogs of the conventional position operator of the harmonic oscillator and its eigenstates are defined as

Since the ground state obeys |0〉~∫dαexp(−α2/4)|α〉, one immediately sees that

This allows one to rewrite (30) according to

where is an abbreviation for .

Equation (34) can be considered a convenient formal expression for a power series in . But it is much more than that: It formalizes the interpretation of the partition function and of the process depicted on the left hand side of Figure 6 in terms of a baby universe Hilbert space. Equation (34) calculates the amplitude relating two spatial slices of the parent universe, allowing for any number of wormholes to be insterted between initial and final time.

The most important point here is that, in this approach, it is both easy and obviously necessary to allow for more general initial and final states: There is simply no reason to treat those as baby universe vacua. For example, one can also consider the transition amplitude between states with n1 and n2 baby universes:

In fact, arbitrary states ψ1 and ψ2 can be considered, another relevant case being that of so-called α-vacua:

Here we ignore the divergent prefactor related to the δ-function normalization of “momentum eigenstates.”

It is easy to see that, for an arbitrary number of operators and arbitrary initial and final states, the above amplitude generalizes to

Here, a basis of local operators has been chosen such that the matrix Δij is diagonal. The and ai carry the same index as the local operators and create or annihilate baby universes of type i. If everything is based on the Giddings-Strominger solution of lowest charge, one may think of these baby universes as of transverse spheres S3 in a perturbed wormhole geometry (or some appropriate quantum superposition thereof).

The Hamiltonian was first derived by Coleman (1988a) by summing explicitly over all possible wormhole and semiwormhole configurations. For completeness, we now briefly explain this computation, for the case of a single type of wormhole for simplicity. Consider a 4-manifold M of the type shown in the right hand side of Figure 6. The initial boundary consists of a large 3-manifold parent universe and n1 incoming baby universes. Of those, n1−r later on merge with M. The final boundary consists again of a large 3-manifold and n2 outgoing baby universes, n2−r of which emerged from M. Thus, r baby universes simply travel from the initial to the final boundary without interacting with the parent universe. Furthermore m baby universes form complete wormholes on M. The path integral sums over all such configuration:

As before, one assumes that each semiwormhole attached to the parent universe contributes a factor . Taking into account the combinatorics and carrying out the summation over m yields

Here the second equality follows by applying Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff in the form exp[(a+a†)Õ] = exp(a†Õ)exp(aÕ)exp(Õ2/2) and inserting the identity operator written as a sum over |r〉〈r|. Thus, the language of a and a† introduced earlier is nothing but a convenient way of counting wormhole topologies.

3.4. The Perspective of α-Vacua and the Wormhole Density

It is clear that the appearance of α parameters in the path integral has the potential to change physics dramatically: Since these parameters are space-time independent, the whole universe (including its time evolution) can be thought of as a superposition of independent universes, each with a specific set of fixed α parameters.

This has become even more apparent in the last subsection, when the baby universe state characterized by the α parameters was introduced. Since all effective operator coefficients or couplings are shifted according to λi → λi−αi, the baby universe state determines the 4d low-energy effective field theory. A whole landscape of such theories, equivalent to the space of α-vacua, exists. At this level, every hope of predicting coupling constants from some fundamental theoretical principle appears to be lost.

The situation might not be, however, quite as bad: for transitions among baby universe vacua an integral over the α parameters with a very specific measure arises. This makes sense in a compact euclidean universe, for example for a large 4-sphere (or a set of large 4-spheres), where no initial or final baby universe state is required. Specifically a 4-sphere geometry is reminiscent of the Hartle-Hawking definition (Hartle and Hawking, 1983) of the Wheeler-DeWitt wave function of the universe (DeWitt, 1967; Wheeler, 1967). Thus, one may think of the integral over α parameters (with the concrete measure derived earlier) as of a preferred wave function of the baby universe state. This point of view allows for at least a statistical prediction of effective coupling constants.

It is essential that the α-parameters are eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian governing the interaction of our large-scale 4d world with the baby-universe state. This was derived above and it can also be seen intuitively: one can not distinguish in principle whether a wormhole attached at a given position x corresponds to a baby universe being absorbed or being created. Hence one always encounters the combination in the effective Hamiltonian. When an operator coefficient is measured, one is projected to a subsector of the theory belonging to a certain eigenvalue α. Further dynamical evolution can not change this value.

As a consistency check one can estimate the density of wormhole ends following Preskill (Preskill, 1989). This is crucial to understand the validity of the dilute gas approximation. Returning to the perspective of the bilocal action, section 3.1, one can focus on a single operator, the cosmological constant. According to (26), the effect of wormhole insertions is then encoded in

where and . Here the n-th order term corresponds to n wormholes. The dominant contribution to the sum comes from terms with , such that the wormhole density in typical configurations is

One arrives at the disturbing conclusion that this density grows with the volume V4.

Fortunately, the result changes if one considers physics at fixed α. According to (36) the wormhole sum is now encoded in

This sum is dominated by terms with . A non-divergent density of wormhole ends in spacetime follows:

Thanks to the suppression factor , this density is expected to be very small for large wormholes with a correspondingly large euclidean action. The problem encountered above in the vacuum-to-vacuum amplitude, |0〉 → |0〉, appears to have been resolved. Technically, the reason is that the sum has been re-organized by combining events where a wormhole is absorbed and created at the same point: a, a† → (a+a†). However, together with the suppression factor comes, of course, the unknown parameter α. In the integration over α, the problem of an overdensity of wormhole ends can in principle reappear. This is the subject of section 5.1

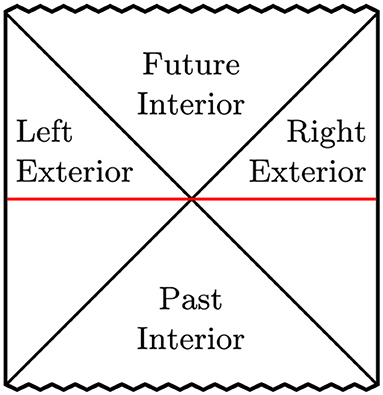

3.5. Multiple Large Universes

Only the case of one large parent universe with many small-scale wormholes attached has been considered so far. It is, however, completely logical to allow for multiple large universes. Wormholes can connect one large universe to itself or to another large universe, cf. Figure 7. When all wormholes are integrated out, the large universes become disconnected.

Figure 7. Large universes connected by wormholes—figure adapted from Fischler and Susskind (1989).

Following Fischler and Susskind (1989) and Preskill (1989), one can single out one particular large universe and consider the expectation value of an observable in that universe. Keeping the values of the α parameters (which are common to all large universes) fixed for the moment, one has

Here Dgd (with “d” for disconnected) stands for the integration over all large-scale metrics, including a summation over manifolds with many components. Making this summation over the number of disconnected components explicit,

Here, in the first line, g is the metric on the distinguished large universe and gn are the metrics on the other disconnected components. The second line used the fact that the sum over disconnected geometries exponentiates, introducing the variable g′ for the metric on a generic such component.

Reinstating the α-integration gives

with the probability distribution

In the calculation of the partition function, i.e., without the insertion of a local operator, no connected component is singled out. The sum over topologies then exponentiates without the need to split of one of the factors:

As discussed later, the double exponential P(α) is responsible both for the initial excitement in wormhole physics (Coleman's solution to the cosmological constant problem Coleman, 1988c) as well as for a particularly serious conceptual problem (the FKS catastrophe Fischler and Susskind, 1989; Kaplunovsky, unpublished).

4. Phenomenological Applications

4.1. Random Values of Couplings and the Cosmological Constant Problem

If one accepts that euclidean wormholes contribute to the path integral, one may clearly be concerned that all of the familiar local physics will break down. The reason is that the action of the wormhole contributions does not grow with the separation of the two points where they attach to our macroscopic spacetime. The possible loss of quantum coherence has also been initially discussed in this context. However, it has quickly been established (Coleman, 1988a; Giddings and Strominger, 1988b) that a local effective field theory description can be recovered by introducing α parameters in the path integral or, equivalently, α vacua in the canonical approach (cf. the discussion in the last chapter).

The implications of this are nevertheless quite dramatic: All coupling constants depend on the α vacuum, i.e., on the a priori unknown baby universe state. This state is an unavoidable additional piece of information which has to come on top of the quantum-field-theoretic initial conditions given on a Cauchy surface of our spacetime manifold. By measuring couplings one is effectively determining some of the infinitely many α parameters. There seems to be no hope of predicting these couplings on the basis of a unique theory of everything, even if the latter was known to us. From a modern point of view, this is of course very similar to the situation which has anyway been widely accepted after the advent of the string theory landscape (Bousso and Polchinski, 2000; Giddings et al., 2002; Kachru et al., 2003; Susskind, 2003; Denef and Douglas, 2004). In fact, both ways of randomizing coupling constants may be at work simultaneously. The familiar deep issue of the measure problem of enternal inflation (the leading candidate mechanism for populating the landscape) has a cousin in the form of the measure on or the dynamics of the baby universe state.

The above situation may be viewed as the generic phenomenological implication of euclidean wormholes or gravitational instantons. For the initial popularity of this paradigm, it was crucial that an apparently very successful attempt was made early on to derive a statistical prediction for one of the couplings—the cosmological constant (Coleman, 1988c) (for early applications of wormholes to other phenomenologically relevant couplings see Grinstein and Wise, 1988; Choi and Holman, 1989; Gilbert, 1989; Nielsen and Ninomiya, 1989; Preskill et al., 1989). In fact, a distribution infinitely peaked at zero was found, making the prediction exact. Subsequently many caveats were discovered such that the “cosmological constant prediction” is not viewed as a central motivation for wormhole physics at present. Nevertheless, because of its intrinsic interest and its immense historical importance we review the argument in the remainder of this subsection (for reviews discussing this as well as other early approaches to the cosmological constant problem see Weinberg, 1989; Carroll et al., 1992).

The argument is due to Coleman (1988c) and can be given using just the leading terms of the bare gravitational action:

Here λ1 = Λ and characterize the cosmological constant and the Planck scale. As discussed before, including the effects of wormholes and allowing for multiple large parent universes (as in Figure 7) leads to the partition function (cf. Equation 48)

Since wormholes have been integrated out, the relevant metric in the above expression refers to a single parent universe. As argued in Coleman (1988c), this expression is dominated by values of α which correspond to Λeff = λ1−α1>0. Furthermore, the sum over topologies is dominated by spheres. The path integral over metrics can then be estimated in the saddle point approximation:

where and the sum is restricted to i, j = 1, 2. Thus, all one needs is the action of a 4-sphere solution with the above effective Planck scale and cosmological constant. Given that a 4-sphere of radius r has volume and scalar curvature R = 12/r2, this action is

This gives

where α1 was redefined α1 → −α1.

The key point of this result is the double exponential enhancement of the measure governing the α-parameter integration at the point where the effective cosmological constant vanishes.

As already emphasized, serious caveats exist and the above logic is nowadays generally not considered a valid solution to the cosmological constant problem. First, the measured value of the cosmological constant is not any more consistent with zero. Second, firm evidence exists for cosmological inflation, and it is not clear how such an early quasi-de-Sitter period fits in the argument for vanishing Λ. Finally, as we will discuss in detail in sections 5.1 and 5.2, the above argument may run into problems with an overdensity of wormholes (the FKS catastrophe) and the sign or negative-mode problem of euclidean quantum gravity.

Nevertheless, reinterpretations of Coleman's mechanism have recently been explored in the context of the cosmological constant and other fine tuning problems of the Standard Model (Kawai and Okada, 2011, 2012; Hamada et al., 2014, 2015). The authors take a Lorentzian approach to the dynamics of multiple large universes connected by wormholes. Such a real-time formulation avoids the problems of the euclidean path integral of gravity, but at the same time modifies the conclusions obtained by Coleman. The analysis is based on the Wheeler-DeWitt wave function for a system of multiple large universes emerged in an evolving baby universe gas. By tracing out the unobserved large and baby universes, a density matrix ρ describing our large universe is derived. The dependence of ρ on the universe volume z and on the couplings of the effective action, i.e., on the wormhole-induced α parameters, is studied. A problematic feature is the divergence of integrals over universe volumes z arising in the density matrix calculation. It is treated by an IR cutoff zIR corresponding to a maximum universe size. Under these assumptions, it is argued that the density matrix ρ peaks at vanishing cosmological constant, as in Coleman's mechanism, albeit with a much milder power-law dependence. This is interpreted as a prediction for a vanishing effective cosmological constant at asymptotically large times.

4.2. Axion Potentials From Wormholes

The main current phenomenological interest in wormholes lies in their interplay with axions. Axions have been an important ingredient in models of particle physics and cosmology since they were first proposed as solutions to the strong CP problem, and have found much wider applications ever since, e.g., as components of dark matter or as inflaton candidates. From a top-down perspective, axions are among the most generic outcomes of string compactifications, and are hence extremely well motivated (see e.g., Arvanitaki et al., 2010).

Axions enjoy a global shift symmetry ϕ → ϕ+ϵ that prevents the appearance of a potential at the perturbative level. It is only non-perturbative effects such as charged instantons and wormholes that can break these symmetries and give axions a mass. In fact, the explicit example of the Giddings-Strominger wormhole arises in the presence of axions and carries a corresponding charge given by (9). This is precisely the type of object required to generate an axion potential, as we review next following Rey (1989) (see also Alonso and Urbano, 2017).

Recall the discussion of section 3.3 on the wormhole correction I[g, ϕ] to the low energy effective action of a large parent universe propagating in a plasma of baby universes. It is given by the effective Hamiltonian (37), which can be written in the form Rey (1989)

Here, the exponential factor has been extracted from the matrix Δmn, making the dependence on it explicit. The remainder is denoted by Kn. The states |ψi〉 live in the Fock space of baby universes on which the parent universe propagates. Correspondingly, an and represent baby universe annihilation and creation operators.

Baby universes associated to Giddings-Strominger wormholes carry an axionic charge given by (9). That is, they satisfy [Q, an] = −nan and , where Q generates the U(1) axionic shift symmetry. This charge is the reason why the combination appears in (54), generalizing Equation (37): it is impossible for an observer in the parent universe to distinguish between the annihilation of a baby universe of charge n, and the creation of a baby universe of charge −n. These two processes hence generate the same local perturbation . Total charge conservation implies that the effective operators must be charged as well , i.e., they transform as under the axionic shift ϕ → ϕ+ϵf. From this one can deduce that the local operators must be of the form , where is a singlet.

One can explicitly evaluate (54) by choosing the baby universes to be in an α-eigenstate (introduced in section 3.3), i.e., |ψ1〉 = |ψ2〉 = |α〉, with .9 The correction to the low energy action of a large parent universe propagating in such a background is hence given by

where . Of course, it is easy to consider propagation between more general baby universe states. For example, |ψ1〉 = |ψ2〉 = |0〉 would lead to an integral of (55) over αn with a Gaussian measure analogous to (34).

The operator can be expanded in a set of singlet operators, e.g., . Of these, the most interesting one is the unit operator, which leads to a potential for the axion. Taking into account only wormholes with charge n = ±1 the induced potential is of the form

The coefficient of the potential is hard to calculate in general. In most cases (in particular for f<MP) its precise value is not very relevant due to the dominant exponential suppression . In the following, whenever an explicit estimate is needed, we will follow (Alonso and Urbano, 2017) and use the wormhole neck radius as in (56). At this stage, if no other potential exists, the phase δ≡δ1 is unphysical and could be absorbed by a shift in the axion field. Generically, in the presence of other terms in the potential, there is no reason why δ1 should not appear. The dimensionless parameter |α1| depends on the baby universe state and is not predicted by the theory. For explicit evaluations one can assume that |α1| is an order one parameter (Alonso and Urbano, 2017). A possible justification could be the expectation value of order one. It is not unreasonable to use the Gaussian distribution since the latter appears when considering propagation between baby universe |0〉-vacua. In principle, however, the α-parameters could take any value.

4.3. Superplanckian Axions

4.3.1. Large Field Excursions and Inflation

One of the most interesting applications of axions is inflation (see e.g., Baumann, 2011; Baumann and McAllister, 2015; Westphal, 2015 for reviews with emphasis on stringy contexts). The perturbative shift symmetry that axions enjoy makes them ideal inflaton candidates in models of large field inflation. In these constructions, the inflaton traverses distances in field space larger than the Planck scale, Δϕ≳MP. Generically, such large field displacements imply a high UV sensitivity of the model since higher-order terms in the potential, , become relevant (here μUV≲MP is a UV cutoff scale). This may clash with the slow-roll requirement of a smooth potential. Successful models of large field inflation hence demand a fine control of UV corrections, as it is indeed provided by axions.

One of the main reasons for the current interest in large field models is their prediction of observable primordial tensor modes in the CMB. These are parametrized by the tensor-to-scalar ratio r. Under mild assumptions, the Lyth bound (Lyth, 1997) relates r to the inflaton field displacement,

The current experimental bounds (Ade et al., 2015, 2016b,a) are r < 0.07 (95% confidence level, Planck, BICEP2/Keck-Array combined), with near future experiments expected to strengthen this bound significantly. The combination of these searches with the Lyth bound and the UV sensitivity of large field inflation provides an ideal playground for testing UV features of effective field theories and possibly quantum gravity.

As already emphasized, the main challenge facing large field models is the control of UV corrections. Symmetries are required to avoid a drastic tuning of higher dimension operators. This is naturally realized by axions since, due to the shift symmetry ϕ → ϕ+ϵ, the axion potential vanishes automatically. This symmetry is mildly broken by non-perturbative effects, such as instantons and wormholes, which generate a periodic potential of the form

Here Λ is a typical UV scale and n-dependent non-exponential prefactors have been suppressed. As discussed previously, gauge instantons and axionic wormholes induce such potentials (Equations (6) and (56), respectively). Different harmonics correspond to instantons/wormholes of different instanton number/axionic charge n.

The idea of natural inflation (Freese and Kinney, 2015) is to use the n = 1 term in (58). Neglecting higher harmonics is justified in many cases due to the expectation that for n>1. Slow roll inflation then requires f>MP (notice that the maximum field displacement of the canonically normalized axion is 2πf). In this simplest form, models of natural inflation are disfavored by Planck (Ade et al., 2015, 2016a,b). However, this can be remedied by small corrections, e.g., from higher harmonics. More importantly, natural inflation continues to play the role of a “benchmark model” exemplifying in the simpest way the interplay between UV theory constraints and observations. Our considerations also have applications in models of axion monodromy (Silverstein and Westphal, 2008; McAllister et al., 2010).

One might try to use wormholes to generate the inflationary potential, but one immediately runs into difficulties. Semiclassically, the charge-n wormhole action is Sn~nMP/f. In the regime of interest, f≳MP, higher harmonics are not sufficiently suppressed, , at least for terms with n≲f/Mp. Thus, there is no hierarchy between the first few terms in the series (58) and hence no perturbative control.

A closely related and more profound issue is the fact that the lowest charge instantons are microscopic and subject to strong corrections. The spectrum of microscopic instantons does not need to resemble the classical spectrum of macroscopic wormholes (just like the spectrum of charged elementary particles does not resemble the spectrum of Reissner-Nordstrom black holes). This suggests that the dominant axion potential will be generated by some microscopic non-perturbative effect, over which one has little control, and macroscopic wormholes will only induce higher corrections. The ideal situation for inflation would then take the form

Here Λinf is the scale of the inflationary potential, generated by a microscopic instanton. The sum is only over macroscopic wormholes, i.e., those whose radius of curvature is larger than the cutoff lenght.

Given this setup, one may ask how important the wormhole contribution is Montero et al. (2015) and Hebecker et al. (2015). To have a successful model of inflation, it should be subdominant:

Because of the exponential dependence, this constraint is highly sensitive to the wormhole action . The dependence on the prefactor Λw is much milder and one can, as in (56), write , where rn is the radius of the S3 at the neck of the wormhole. The constraint (60) becomes

This bound takes its tightest form for the wormholes with lowest charge. One should, however, only consider those which are controlled in effective field theory, i.e., whose neck radius rn is larger than a UV cutoff scale . This condition defines nc in (59). The constraint can now be further rewritten in terms of the cutoff (Hebecker et al., 2015, 2017)

One sees that, parametrically, inflation is in trouble in theories with a high cutoff, μUV~MP. The reason is that one has an (1) number in the exponent, hence an (1) numerator, and a parametrically small denominator. However, taking into account the surprisingly large numerical prefactor 3π3/2 and the value relevant for phenomenological large field inflation, the conclusion changes dramatically. One finds that the inequality (62) is saturated at μUV≃2.5MP (corresponding to rn≃0.4MP). Thus, even the smallest controlled wormhole solutions appear to be harmless (Hebecker et al., 2017).10

4.3.2. The Weak Gravity Conjecture (WGC)

The inflationary potential (59) is perfectly acceptable from a (bottom-up) effective field theory perspective. As just discussed, macroscopic wormholes do not affect this potential significantly. However, one may be concerned that the contribution from smaller wormholes was removed by hand, and this is, at least naively, the dominant one. To argue for generic constraints coming from this regime, where one loses semiclassical control, one has to resort to ideas about the quantum gravity swampland.

The concept of the swampland (Vafa, 2005) refers to the set of apparently consistent low-energy effective field theories which are, nevertheless, inconsistent with a UV completion in quantum gravity. It arises most naturally in string theory, where it represents the complement, in the space of effective field theories, of the vast landscape of string compactifications. Effective theories in the swampland are those that cannot arise from a UV-complete fundamental theory, and in particular from string theory.

Several criteria have been conjectured to discern whether a given theory belongs to the swampland. Most of them refer to properties of the spectra of operators charged under gauge symmetries. The simplest and perhaps most solidly founded of the swampland conjectures are the statements that every symmetry must be local and that the whole lattice of corresponding gauge charges consistent with charge quantization must be populated (see e.g., Banks and Seiberg, 2011). That is, for every symmetry there must exist a gauge potential (Aμ in the case of a one-form), and there must exist states carrying every possible set of charges (every integer charge for a single U(1) with an appropriate normalization).

A more stringent, albeit more speculative conjecture is the WGC (Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007a): It states that at least some of the charged states must be super-extremal, that is, their charge-to-mass ratio must be larger than that of the corresponding extremal gravitational solution:

This is generally described as the statement that “gravity is always the weakest force,” since when (63) is satisfied, the gauge repulsion of two distant equal-charge objects dominates their gravitational attraction. In case of a single U(1), the extremal object corresponds to an extremal Reissner-Nordstrom black hole, which in appropriate units satisfies .11 Since macroscopic gravitational solutions cannot be super-extremal (super-extremal black holes contain a naked singularity, violating cosmic censorship), one expects (63) to be satisfied by microscopic objects. For such states, quantum corrections can become relevant, pushing them away from extremality.

Now, what does all of this have to do with axions, wormholes and inflation? In general, abelian gauge theories arise from p-form gauge fields under which p-dimensional objects (i.e., whose world-volumes are p-dimensional) are charged. The swampland conjectures, and in particular the WGC, are expected to hold for all possible p (Arkani-Hamed et al., 2007a). The case of particles with electric charge corresponds to p = 1, strings coupled to a two-form field to p = 2 and, most relevant for our interests, axions can be understood as p = 0 gauge fields, to which “zero-dimensional” instantons/wormholes couple. This interpretation can be made manifest by considering a standard one-form gauge field in 5d, reduced on a circle to 4d. The component of the gauge field along the circle, the Wilson line, becomes a periodic axion in 4d, whose periodicity reflects the higher dimensional gauge symmetry. In this way, one can relate the mass m and charge q of a 5d particle to the action Sn and axionic charge n of a 4d instanton, respectively. The WGC (63), when applied to axions is hence expected to read

Just like extremal black holes satisfy M/Q~eMP with e the gauge coupling, one generally expects extremal instantons to satisfy SN/N~Mp/f. If the WGC (64) is satisfied by the instanton of lowest charge n = 1, this means that S1f≲MP. This is incompatible with the basic requirements of large field natural inflation (f≳MP) in regimes of perturbative control, Sinst≳1.12 Setups in which the instanton that satisfies the WGC is not the one of lowest charge have been proposed as a loophole to this strong constraint (Rudelius, 2015; Brown et al., 2015, 2016) and are being actively investigated (Hebecker et al., 2015)13.

The main difficulty in making the requirement (64) more precise is to properly identify what one means by an extremal instanton/wormhole. In setups where the axion arises from a 5d gauge field, one can see that the higher dimensional extremal black holes correspond to the extremal instantons introduced in section 2.3. However, these setups always involve a dilaton field (the radius of the compactification circle) for which the coupling parameter β of Equation (16) is . Recall from section 2.3 that wormhole solutions only exist for . Since the main interest (at least for inflation) is in the case where the dilaton has been stabilized and disappears from the low energy theory, i.e., β = 0, the relation to higher dimensional black holes is lost, along with a rigorous notion of an extremal instanton/wormhole.

Hence, with our current understanding, some amount of guesswork is required to properly interpret (64) in a pure axion-Einstein theory. Following Hebecker et al. (2017), we will assume that, on the right hand side of the bound, one needs to use the classical action of a macroscopic wormhole. With this interpretation, the WGC states that some microscopic “wormhole” has a charge-to-action ratio larger than its macroscopic counterpart, i.e., that .

Finally, we return to the effective model of natural inflation (59). As discussed before, the sum over macroscopic wormholes is generically suppressed strongly enough to be ignored. Ideally, one could hope that the uncontrolled microscopic wormholes somehow disappear from the low energy theory. However, the WGC implies14 quite the opposite, namely that (at least some) microscopic wormholes/instantons are less suppressed than their macroscopic counterparts and inflation is strongly affected.

A possible caveat to this conclusion is the implicit assumption that all instantons enter the potential with (1) prefactors. This, however, is not in principle required by the WGC. The smoothness of the inflationary potential may be preserved if the coefficients of dangerous corrections vanish or are highly suppressed, i.e., if (see de la Fuente et al., 2015 for a model potentially realizing this possibility).

To discuss this point more generally, one can split the correction to the potential according to

with α>0. Here ΔV1 comes from macroscopic instantons or wormholes and is harmless, as explained above. By contrast, ΔV2 comes from their microscopic counterparts and is dangerous according to the WGC. The reason is that small, low-charge instantons are not exponentially suppressed, for n ~ (1). However, the prefactor of those instantons can be smaller than the naively expected . This has been has been parametrized by including a factor .

As an example, let the microscopic instantons be gauge instantons of some non-abelian 4d gauge theory. The presence of charged fermions of mass m does not affect the contribution of large instantons (relative to 1/m). By contrast, the contribution of small instantons is suppressed by with α proportional to the number of fermions (as in the lower line in (65)). An analogous suppression can arise in the case of brane-instantons due to the presence of fermionic zero-modes. These are generally lifted by the SUSY breaking required for inflation. The formula (65) is grossly oversimplified in that just a single threshold, μUV, occurs. It is only intended to illustrate how the smallness of corrections could in principle come about. Indeed, one sees that may be satisfied (for appropriate α) together with H≲μUV≪MP. Finding specific implementations of such a mechanism remains challenging.

To summarize: effects of macroscopic wormholes in the low energy Einstein-axion theory are in general not strong enough to constrain models of natural inflation. Nevertheless, expectations based on the WGC place potentially strong bounds on such models. In particular, trans-Planckian axion decay constants are expected to arise only in regimes where perturbative control is lost, e.g., where microscopic wormholes/instanton spoil slow-roll conditions. Several possible ways around such constraints exist and are being actively studied. Whether such loopholes can be implemented in specific (string theory) setups is the subject of ongoing research.

4.4. Subplanckian Axions and Goldstone Bosons

Sub-Planckian axions f<MP are not suitable to accommodate inflation but they are extremely interesting in other phenomenological setups. Again, it is their shift symmetry and the resulting exponential suppression of their masses that makes them stand out among the plethora of fields relevant at low energy.

Let us repeat here for convenience the wormhole induced axion potential (56):

The mass induced by this potential is given by

In contrast to trans-Planckian axions, for a decay constant smaller than the Planck scale the wormhole contribution is strongly suppressed through the exponential . This ensures that the axion is very light, making it suitable for many phenomenological applications. The exponential dependence implies that small changes in f drastically change the value of m, allowing for a wide range of values for the mass. This observation will be a recurring theme in the following.

Another feature specific to sub-Planckian axions is that even wormholes of unit charge are macroscopic, in the sense that the size of their throat r0 is larger than the Planck scale. This is a rather peculiar property, but it is necessary for (66) to be trustworthy. More in general, in an effective theory with UV cutoff μUV, the validity of (66) requires . If the cutoff scale becomes too low, one may expect sizeable corrections to the action of the wormholes with lowest charge.15 The results described in this section assume the validity of (66), with Sw taking its classical value. The important caveat just mentioned should nevertheless be taken into account when interpreting these results.

We proceed now to review potential phenomenological applications of axions with an induced wormhole potential of the form (66). Significant parts of our discussion follows (Alonso and Urbano, 2017)16.

4.4.1. Black Hole Superradiance and Bosenovas

As just explained, axions play a special role in testing quantum gravity, especially wormhole or baby universe effects. The reason is their extremely suppressed potential. Furthermore, assuming that the relevant α parameters take their natural (1) value, the potential and hence the mass are predicted in terms of the decay constant.

However, a generic (in particular non-QCD) axion is hard to observe. One classical possibility is black hole superradiance (Damour et al., 1976; Zouros and Eardley, 1979; Detweiler, 1980). This term characterizes the energy deposition by a spinning black hole into a light scalar field, not-necessarily an axion, of suitable mass. The relevance for the discovery of axions has been emphasized in the context of the “string axiverse” (Arvanitaki et al., 2010) and continues to receive much attention (see e.g., Arvanitaki et al., 2015, 2017; Brito et al., 2017a,b; Cardoso et al., 2018). A recent discussion in the wormhole context appears in Alonso and Urbano (2017).

The dependence of superradiance on the most important physics parameters are easily explained. Consider a spinning black hole with mass M, angular momentum J and typical radius . One generally uses the spin parameter a = J/M to characterize its rotation, with a = R correspnding to extremality.17 Superradiance is a classical instability which draws energy from the black hole and deposits it in the field oscillations of a light scalar, localized in a spherical region outside the horizon. Very roughly, one may think in terms of (classical analogs of) electron shells of an atom being populated by this scalar. The effect relies on the black hole being near extremality and on the Compton wavelength of the axion being comparable to the black hole radius, R~1/m.

It is instructive to consider what happens if this latter condition is not met (Arvanitaki et al., 2010): For an extremal black hole and R≫1/m, the instability time scale is given by Zouros and Eardley (1979)

In this regime, the Compton wave length is small and only modes with a large angular excitation superradiate. But such modes experience a high and thick centrifugal barrier, leading to an exponential suppression of the rate 1/τ. For subcritical a the exponential suppression is even stronger. In the opposite regime R≪1/m, one has (Detweiler, 1980)

In this limit, low modes are available for superradiance. However, the potential well is now very wide and the modes spread out. One may say that the scalar's Compton wavelength is too large such that the small overlap with the black holes induces a suppression.

Efficient superradiance hence requires a relation between the black hole mass and the axion Compton wavelength. Stellar black holes (2−100M⊙) correspond to axion masses of 10−13−10−10eV and supermassive black holes () to 10−19−10−16eV. The crucial signal for an axion in one of these regions would be gaps in the spectrum of rotating black holes. At present, spin and mass observations of stellar black holes exclude the range (Arvanitaki et al., 2015)

Note that a detection of axion-induced superradiance is also possible through gravitational waves. The gravitational wave signals from, e.g., axion annihilation or axion transitions may be detected by future experiments at LIGO, VIRGO and at LISA (Arvanitaki et al., 2015, 2017; Brito et al., 2017a,b; Cardoso et al., 2018).

In our context, i.e., for a pure-quantum-gravity potential, the relation (67) between mass and decay constant may in principle provide information beyond the generic axion case. Of course, the mass is subject to the uncertainties from the α parameter and fluctuation determinant. However, as can be seen by solving (67) for f,

the sensitivity to these uncertainties is extremely week. Indeed, for |α1| = 1 the above excluded mass window corresponds to the surprisingly narrow range 1.23 × 1016GeV≲f≲1.28 × 1016GeV. Thus, under the above assumptions, an axion discovery at the edge of the present mass window would imply a very precise determination of f. Similarly, the mass window 10−19eV≲m≲10−16eV accessible via supermassive black holes translates to 1.06 × 1016GeV≲f≲1.13 × 1016GeV. However, the key question is then whether an independent measurement of f for such a “quantum gravity axion” is conceivable.

It turns out that the answer to this question is positive: To measure the mass, it suffices to study superradiance at linear order. However, to get independent information about f, higher-order terms in the cos(ϕ/f) potential have to be probed. This is possible, for example, in the context of the so-called bosenova. The term derives from analogous condensed matter phenomena (Donley Elizabeth et al., 2001). In a bosenova, the self-interactions of the growing axion cloud around the black hole lead to a dynamical collapse: Part of the extracted energy is ejected and the rest returned to the black hole. This may happen multiple times until enough spin has been extracted from the black hole and superradiance (at least for the given level) is lost (Yoshino and Kodama, 2012).

Among the observable effects are a continuous gravitational wave signal as well as bursts of gravitational waves. For the continuous case, an analysis based on a possible axion cloud of the stellar black hole Cygnus X-1 was reported in Yoshino and Kodama (2015a). Assuming that the LIGO upper limit is similar to that for gravitational waves from rotating distorted neutron stars, an expected exclusion range was derived. For 1.1 × 10−12eV < m < 2.5 × 10−12eV, it restricts f to lie below 1015–1016GeV. This can be understood intuitively since, as f grows, the bosenova cuts off the superradiance instability at higher axion densities, leading to larger signals. Notice that the bound on f is in the range relevant for wormhole induced potentials as discussed above. Realistic detection prospects exist also for gravitational wave bursts (Yoshino and Kodama, 2015b). Present limitations of the theoretical analysis are related to the need for including backreaction and extending certain parts of the numerics from the Schwarzschild to the Kerr solution (for details see e.g., Yoshino and Kodama, 2015b).

4.4.2. QCD Axion

For the QCD axion an interesting observation can be made (Alonso and Urbano, 2017). The total potential, including the contribution from the usual QCD instantons, is given by

where the axion ϕ is defined such that the QCD instanton induced potential is minimized at ϕ = 0. The phase δ is redefined accordingly and is generically non-zero since there is no obvious reason for the two terms in the potential to have the same minimum. Furthermore, the |α1| parameter has been set to one.

The dependence of the axion mass on the decay constant is interesting. With increasing f, the QCD contribution decreases while the wormhole one grows. Hence, the axion mass features a minimum as a function of f. It is not unreasonable to expect, on theoretical grounds, that gravitational effects are subdominant with respect to gauge contributions. This requires that f≲1.4 × 1016GeV. This bound can also be derived from phenomenological considerations. The the phase of the wormhole contribution implies a shift of the minimum of the potential and hence a non-zero QCD θ-parameter θeff. The experimental bound coming from the neutron electric dipole moment constrains the wormhole contribution. Specifically, assuming , one finds a bound on the decay constant f≲1.2 × 1016GeV. One might have suspected that the tight requirement would lead to a stronger bound on f. This is not the case, however, due to the strong exponential dependence of the wormhole contribution.

In the regime of small wormhole corrections, one can expand the potential (72) and obtain the axion mass and effective θeff parameter as functions of f, ΛQCD and MP:

The minimal mass obtained from (73) is m≳4 × 10−9eV. Notice that the bound coming from superradiance described above is irrelevant in this case.

4.4.3. Axions as Dark Matter

Despite its success on scales larger than 10kpc, the scale of stellar distributions in typical galaxies, it is not clear yet if the cosmological ΛCDM model is consistent with observations at smaller distances (Weinberg et al., 2015). The tension arises from the cuspy halo cores and an abundance of satellite galaxies predicted by numerical simulations but incompatible with observations. Using an extremely light scalar field with mass 10−22−10−21eV, it is possible to construct a model of dark matter with the same large scale predictions as CDM, in which, however, these problems are absent. The key idea here is that the large Compton wavelength of a light particle can suppress the formation of structures on sufficiently small scales. This dark matter model goes by the name of Fuzzy Dark Matter (FDM) (Hu et al., 2000).

Because of its extreme lightness, an axion with the induced potential (66) is an ideal candidate for FDM. Information about the possible values of f can be obtained by reproducing the observed relic abundance via the misalignment mechanism (Abbott and Sikivie, 1983; Preskill et al., 1983; Dine and Fischler, 1983). Assuming an initial misalignment angle of order one θi = ϕi/f≈1, the axion contribution to today's energy density (normalized by the critical energy density) is given by Arvanitaki et al. (2010) and Kim and Marsh (2016) (see also Hui et al., 2017)