- Research Training Group “Doing Transitions”, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt, Germany

With the aging of the “Baby Boomer” cohort, more and more adults are transiting from work into retirement. In public discourse, this development is framed as one of the major challenges of today's welfare societies. To develop social innovations that consider the everyday lives of older people requires a deeper theoretical understanding of the retiring process. In age studies, retiring has been approached from various theoretical perspectives, most prominently disengagement perspectives (retirement as the withdrawal from social roles and responsibilities) and rational choice perspectives (retiring as a rational decision based on incentives and penalties). Whereas, the former have been accused of promoting a deficient image of aging, the latter are criticized for concealing the socially stratified constraints older people experience. This paper proposes a practice-theoretical perspective on retiring, understanding it as a processual, practical accomplishment that involves various social practices, sites, and human, as well as non-human, actors. To exemplify this approach, I draw upon data from the project “Doing Retiring” that follows 30 older adults in Germany from 1 year before to 3 years after retirement. Results depict retiring as a complex process of change, assembled by social practices that are scattered across time, space, and carriers. Practice sequences and constellations differ significantly between older adults who retire expectedly and unexpectedly, for example through sudden job loss or illness. However, even among those who envisaged retiring “on their own terms,” the agency to retire was distributed across the network of employers, retirement schemes, colleagues, laws, families, workplaces, bodies and health, and the future retiree themselves. Results identified a distinct set of sequentially organized practices that were temporally and spatially configured. Many study participants expressed an idea about a “right time to retire” embedded in the imagination of a chrononormative life-course, and they often experienced spatio-temporal withdrawal from the workplace (e.g., reduction of working hours) which entailed affective disengagement from work as well. In conclusion, a practice-theoretical perspective supports social innovations that target more than just the retiring individual.

Introduction

With the aging of the “Baby Boomer” cohort, more and more adults are—and will, in the next decade, be—transiting into retirement. In public discourse, this development is framed as one of the major challenges of today's welfare societies that call for social innovations. To develop innovations that not only address the economic and political level but also take into consideration the everyday lives of older people themselves, I argue, requires a deeper theoretical understanding of the retiring process than currently exists in retirement research.

As one of the major transitions in the institutionalized life-course (Kohli, 1985, 2007), the transition from work to retirement marks the beginning of the stage of later life. As such, it can be framed as a rite de passage (van Gennep, 1960) that can be divided into three broad phases: separation, liminality, and incorporation. In the first phase, people disengage from their current status and prepare for the upcoming separation. In regard to retirement, the separation phase encompasses the period in which older persons are not yet formally retired; hence, they are often still working and, when they retire on their own terms, preparing to leave their workplaces1. The subsequent liminal phase is a stage between statuses, i.e., between working and being retired. The incorporation stage, finally, completes the transition, providing a person with new roles, practices, and a new identity as a retiree. Applying this, admittedly rough, framework for analytic purposes, this paper focuses on the separation stage, namely the stage in which retirement preparations are taking place up to the time when people claim and receive their pension benefits2.

In age studies, retiring has been approached from various theoretical perspectives, most prominently disengagement perspectives (retirement as the withdrawal from social roles and responsibilities; cf. Crawford, 1971) and rational choice perspectives (retiring as a rational decision based on incentives and penalties, cf. Wang and Shultz, 2010). Whereas, the former have been accused of promoting a deficient image of aging, the latter are criticized for concealing the socially stratified constraints in the contexts within which people are embedded. This paper proposes a practice-theoretical perspective on retiring, understanding it as a processual, practical accomplishment that involves various social practices, sites, and human, as well as non-human, actors (cf. Schatzki, 2002; Shove et al., 2012). It focuses on the separation stage (cf. van Gennep, 1960) of the transition, studying what happens between working and not working anymore. To exemplify this approach, I draw upon data from the project “Doing Retiring—The Social Practices of Transiting into Retirement and the Distribution of Transitional Risks” (2017–2021). Methodologically, the project follows 30 older adults in Germany from 1 year before to 3 years after retirement, combining episodic interviews, activity and photo diaries, and participant observations.

The paper is structured into four parts: the first part portrays two major theoretical perspectives deployed in retirement research and introduces practice theories as an innovative perspective that can prove fruitful for retirement research. The second part introduces the German “Doing Retiring” project and the data analyzed in this paper. In the third part, results are presented, which are then discussed in the fourth part. Finally, the paper concludes with practical implications that can be drawn from a practice-theoretical analysis of the retiring process.

Theoretical perspectives in retirement research

The field of retirement studies can be divided into those studies that address retirement as the dependent variable and those that address it as the independent variable for various outcomes like life satisfaction, health, or mortality. Studies of the former type dominate the field of research and will also be in the focus of this paper (Ekerdt, 2010). Reviewing retirement research published since 1986, Wang and Shultz (2010) identify four theoretical perspectives in the field: (1) retirement as a form of decision-making, (2) retirement as an adjustment process, (3) retirement as a career development stage, and (4) retirement as a part of human resource management (p. 175). Whereas, the latter two are more prominent in management studies, gerontology has traditionally been concerned with the former. Understanding retirement as a form of decision-making focuses research on the rationality of the retirement decision and its circumstances, whereas understanding retirement as an adjustment process calls for investigating its functional and longitudinal mechanisms. While the former approaches emphasize the beginning of the retirement process, marked by the decision to retire, the latter are more often deployed to explain how people adjust to changes that have already happened. Disengagement theories, as one specific form of adjustment theories, however, focus on the separation process in particular.

Disengagement Perspectives on Retiring

“Retirement scholarship addresses, directly or indirectly, withdrawal from work in later life on the part of individuals, groups, or populations” (Ekerdt, 2010, p. 70). Since the 1960s and 1970s, disengagement theories have been heavily influential in researching retirement processes. First formulated by Elaine Cumming and colleagues in the early 1960s (Cumming et al., 1960), theories within the disengagement paradigm (cf. Cumming, 1964; Henry, 1964; Crawford, 1971; Hochschild, 1975) assume that later life is characterized by an overall disengagement from all (or, in later revisions, some) social spheres. Society is gradually releasing a person from their social roles, and the individuals themselves give up these roles—they are disengaging from work when they (have to) retire, from their parenting role when their children move out, from sexuality and social networks and from the public sphere. Disengagement theories, thus, frame later life as a stage of transition from being a functional and productive member of a society to being societally dispensable. Disengagement is functional as it facilitates the “retirement” of a person from society without leaving too much of a gap for either (Powell, 2001). These perspectives thus presume a double-sided withdrawal—the individual withdraws “voluntarily” from social roles, and society offers individuals the “permission” to withdraw (Hochschild, 1975). It has been used for studying retirement as one of the major realms from which older people are institutionally guided to withdraw.

“[…] withdrawal may be accompanied from the outset by an increased preoccupation with himself: certain institutions may make it easy for him.” (Cumming and Henry, 1979, p. 14)

It is not precarious to suggest that disengagement theories relied on and reinforced deficient images of aging, which also provoked criticism. One is that disengagement was originally framed as universal, inevitable, and irreversible. Looking at retirement, all of those assumptions may be questioned today. First, not everyone retires. There are—still predominantly women—who are not eligible for pension benefits, or whose pensions would be too small to afford to retire. On the other side of the social stratum, certain professionals (like artists, priests, or professors) do not retire because they deliberately seem to choose not to. Second, the emergence of various post-retirement transitions, including bridge employment and second/third careers, question whether re-entering the workforce is impossible (cf. Henkens et al., 2017).

In her 1971 study “Retirement and disengagement,” Marion Crawford found that disengagement and retirement do not necessarily go hand in hand for all social groups. In her sample, one group equated retirement with loss of meaningful life space, however involuntarily and not double-sided. Other groups also viewed retirement as disengagement, but only from the working sphere, thus offering opportunities to re-engage or re-align in other spheres of life. However, her research focused on perceptions, and not practices, of retiring. Arlie Russell Hochschild (1975) later reformulated disengagement as a process that varies by (1) kind of disengagement (social or normative), (2) macro-societal factors (e.g., in pre or post-industrial societies), and (3) social position of the retiring individual (e.g., between men and women).

According to Crawford (1971), disengagement from work is viewed in a positive light when the decision is framed as voluntary and in a negative light when individuals feel forced into leaving work. To perceive retiring as involuntary is more likely to occur when people's retirement age deviates strongly from an age viewed as “normal” retirement age (van Solinge and Henkens, 2007). In a study on mainly working-class men, Goodwin and O'Connor found that “indeed the central tenet of disengagement theory, that disengagement from the labor market is a voluntary decision, had little currency amongst this group” (Goodwin and O'Connor, 2014, p. 584).

In the decades following the 1980s, disengagement theories became less and less widespread in retirement research and were increasingly replaced with theories that focused on exactly the choice and voluntariness aspect discussed above: rational choice theories.

Rational Choice Perspectives on Retiring

When conceptualizing retiring as an outcome of informed decision-making, researchers often resort to rational choice theories3. Rational choice perspectives on retirement have been taken on by psychologists (cf. Wang, 2013), economists (cf. Hatcher, 2003; Adams and Rau, 2011) and gerontologists (cf. Ekerdt et al., 2001). They assume that individuals have sufficient information regarding their situation, their work environment and the predictions they can make for future consequences; that they weigh these factors; and that they evaluate the overall utility of retirement before they decide whether to retire or not (Wang and Shultz, 2010).

From a rational choice perspective, decisions of any kind are composed of three parts: first, there is more than one possible alternative; second, the decision maker can form expectations concerning future outcomes of these decisions; and third, they can assess the consequences associated with the possible outcomes, and link them to their personal goals and values (Hastie and Dawes, 2010). Hence, decisions presume a (1) intentional, rational and relatively self-determined individual in (2) relatively unconstrained situations that offer at least two alternatives to choose from, and (3) life-worlds in which futures are stable and certain enough to be predicted—all of which is not necessarily the case (cf. Moffatt and Heaven, 2017).

From a purely economic rational choice perspective, working individuals will retire only when they feel that their financial resources and future economic forecast allow them to support their consumption needs in retirement (Hatcher, 2003). This rather simplistic perspective has been elaborated in retirement research, developing more processual than eventful perspectives and acknowledging the constraints people face in decision-making. Feldman and Beehr (2011), for example, model retirement decision-making as a psychological process that consists of several sequential and discrete decision-making stages. This process may start with informal planning and lead to more formal planning (Wang and Shultz, 2010). Wang and Shultz, however, acknowledge that “retirement decisions are often made in the face of incomplete and imperfect information, which renders a sense of uncertainty in the decision-making process” (p. 1986), which has not yet been integrated into rational choice frameworks on retiring.

However, the choices available to future retirees are always framed within different discourses and structures. Studies have elaborated, first, on the role of public policy and institutional arrangements in structuring possible retirement alternatives (cf. Fasang, 2010) and shaping norms for a “right” retirement age (cf. Jansen, 2018); second, on the role of organizational contexts (Phillipson et al., 2018); and third, on social inequalities. Inequalities have been widely observed in regard to gendered retirement transitions (cf. Moen et al., 2001) and social class (cf. Phillipson, 2004). Inequalities have grown more severe with the closure of many early retirement pathways in Germany, which have been an important exit route for lower-skilled workers who are now forced to work longer due to financial need (Hofäcker and Naumann, 2015).

Both continuing to work and transiting into retirement are often not perceived as voluntary. Based on European Social Survey (ESS) data, Steiber and Kohli (2017) found that, in the majority of the European countries they analyzed, 30 per cent and more of retirees retired involuntarily, meaning that they would have preferred to continue working but had to retire due to legal, employer-based or health reasons. Older adults who had precarious careers across their life-courses or experienced job losses and phases of unemployment were more likely to retire involuntarily, as well as women who worked in higher-status occupations and those who worked part-time.

However, beyond putting limits to the assumptions of rational choice perspective, some studies have found that many older workers do not engage in retirement planning and conscious decision-making at all (Ekerdt et al., 2001; Adams and Rau, 2011). With the recent and future changes in the work-retirement landscape, the explanatory power of rational choice approaches might diminish even further, as individuals may experience a loss in the agency on retiring. 2005, p. 92) call this development “individualization of retirement,” resulting in an increased range of risks instead of increased retirement transition alternatives. Hence, researchers have called for a shift in attention to actual experiences of retirement transitions and planning and called for qualitative studies (Vickerstaff and Cox, (2013). As Moffatt and Heaven (2017) argue, age studies can gain a much more realistic understanding of retirement planning through focusing on retiring practices which can be understood “no longer [as] discrete events but are diverse, disrupted and socially structured” (p. 894).

Practice-Theoretical Perspectives on Retiring

With increasing changes in the work-retirement landscape, research is confronted with the need for, and opportunity to, re-think theories on the transition from work to retirement (Phillipson, Jex and Grosch, 2018). Departing from the criticism of functionalist disengagement theories and individualist rational choice theories, this paper proposes a critical practice-theoretical perspective on the retirement process. From such a perspective, retiring can be framed as a process that is assembled by social practices which unfold scattered across time, space, and carriers. This perspective contradicts both the notion that retiring is a universal process of disengagement and the notion that retiring is the outcome of individual, rational decision-making. Instead, it opens the researchers' perspective to see the multiple human and non-human actors that are part of the retirement process, how retiring is a practical accomplishment and the decision to retire is a situated practice within this process

Social practices can be described as “temporally and spatially dispersed nexus[es] of doings and sayings” (Schatzki, 1996, p. 89) “which consist of several elements interconnected to one other” (Reckwitz, 2002, p. 249), including bodily and mental activities, artifacts and things, knowledge, attitudes, and emotions (cf. Reckwitz, 2002; Shove et al., 2012, p. 289) defines social practices as (i) bundles of doings and sayings that are (ii) bound by a kind of practical know-how incorporated in human bodies and artifacts and (iii) intelligible and typologized. Whereas, the term “action” is strongly linked to an actor, practices highlight the embedded, decentralized qualities of doings. Social practices are thus doings without clearly demarcated actors—they are collective practices instead of individual practices (Shove et al., 2012). From a critical practice-theoretical perspective, consequently, everything that the social sciences might treat as an attribute of a person becomes a practical accomplishment—not something people are, but something they do (cf. “doing gender”: West and Zimmerman, 1987; Butler, 2004; “doing age”: Laz, 1998; Schröter, 2012).

As social practices stretch in time and space, they form bundles, complexes, and constellations. They are always woven into a nexus of other practices—the life-course, for example, can hence be viewed as one gigantic constellation of social practices, and life-course transitions as a temporally smaller segment within this constellation. Social phenomena, consequently, are slices or features of practice-arrangement nexuses (Schatzki, 2010, p. 139). This nexus of practices, as well as slices of it, are organized by practical knowledge, norms and teleoaffective structures, temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed (Schatzki, 1996, p. 89). One such organizational principle that is of particular importance for life-course transitions is chrononormativity. Chrononormativity refers to the “interlocking temporal schemes necessary for genealogies of descent and for the mundane workings of everyday life” (Freeman, 2010, p. xxii) that “may include (but are not exclusive to) ideas about the “right” time for particular life stages” (Riach et al., 2014, p. 1678), like retiring. Krekula et al. (2017) translate this life-course concept into an everyday life level, emphasizing the interconnections between temporality and normality that are being practiced though subtle everyday practices. In contrast to chrononormativity, they call this everyday making of temporal normality norma-/temporality.

A critical practice-theoretical perspective on life-course transitions consequently leads us to ask the following questions:

(i) How are transitions being done? What social practices do they involve?

(ii) How are these practices scattered across time, space, and carriers?

(iii) What are the underlying structures that organize the transition process?

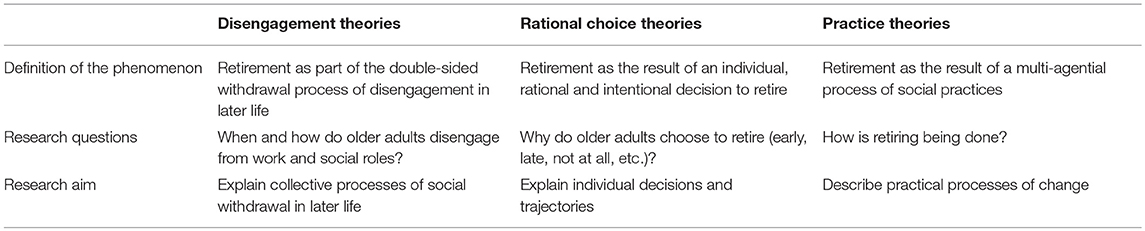

Concluding, the critical potential of practice theories lies not only in its shift in focus (to social practices), but in its challenging of positivist, functionalist, and rational choice approaches. A practice-theoretical approach toward studying retirement understands retiring as a multi-agential process of social practices that is neither universal nor inevitable, neither intentional nor rational. From this perspective, there is neither a societal function of disengagement nor a rational, individual decision to retire that initiates this process. Instead, the flow of social practices that may—but not necessarily does—lead to retiring is variable and contingent; it is prone to change; and the decision to retire is just one out of many situated practices. Table 1 summarizes the main differences between disengagement, rational choice, and practice-theoretical approaches.

Table 1. Comparison of disengagement theories, rational choice theories, and practice theories in regard to retiring.

The “Doing Retiring” Project

Data analyzed in this paper stems from the project “Doing Retiring—The Social Practices of Transiting into Retirement and the Distribution of Transitional Risks” (2017–2021) in which the author is involved. The project is part of the DFG-funded (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) interdisciplinary research training group “Doing Transitions—The Formation of Transitions over the Life Course,” located at Goethe University Frankfurt am Main and Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Germany. It seeks to complement transition research by analyzing how transitions emerge, focusing on the interrelation between discourses on transitions, institutional regulation and pedagogical action, as well as individual processes of learning, education and coping4.

Data and Methods

Methodologically, the project “Doing Retiring” deploys a mixed-methods research design, combining both qualitative and quantitative methods. It follows 30 older adults in a qualitative longitudinal study from before retiring to 3 years after that. In the course of this period, yearly episodic interviews are conducted and participants are asked to keep an activity and photo diary for 7 days per data collection wave (resp. per year). Qualitative data is complemented with secondary analysis from two quantitative datasets: the German Transitions and Old Age Potential (TOP) dataset and German Time Use Survey (GTUS) data. This paper will focus on results from the first wave of data collection of the qualitative panel study, hence focusing on the “separation stage” or period within the retiring process before persons receive old age pension benefits and are thus formally retired.

Sampling

The first wave of data collection took place from September 2017 to April 2018. Participants were recruited through an information brochure with the header “Are you retiring?” Selection criteria stated in the brochure comprised age—starting at age 555 without an upper age limit—and the precondition of planning to stop working within the upcoming 12 months or claiming old age pension benefits within the upcoming 12 months6.

“Retiring” is, however, not quite easy to define, as there are multiple, potentially overlapping criteria that define the retirement status: cessation of work, reduced work effort, receipt of pension benefits, or self-definition (Szinovacz and DeViney, 1999). For the sampling of this study, retiring was defined as either the moment in time when people planned to stop working and not continue anymore, regardless of whether they were eligible for pension benefits yet, or the moment in time when people planned to receive their old-age pension benefits, regardless of whether they would continue to work (in marginal, part-time or full-time employment). The brochure also stated clearly that persons who are retiring out of non-employment, i.e., from unemployment or domestic work, were being sought. All participants would receive an incentive of € 50 for each wave of completing an interview and 7 days of activity and photo diaries.

The brochure was distributed across different channels, ranging from Goethe University (to recruit retiring professors) to different professional associations, including the association of waste collectors and the association of craftsmen in Hessen, the University of the Third Age in Frankfurt am Main, job agencies targeting older persons, NGOs supporting low-income persons, and among personal contacts.

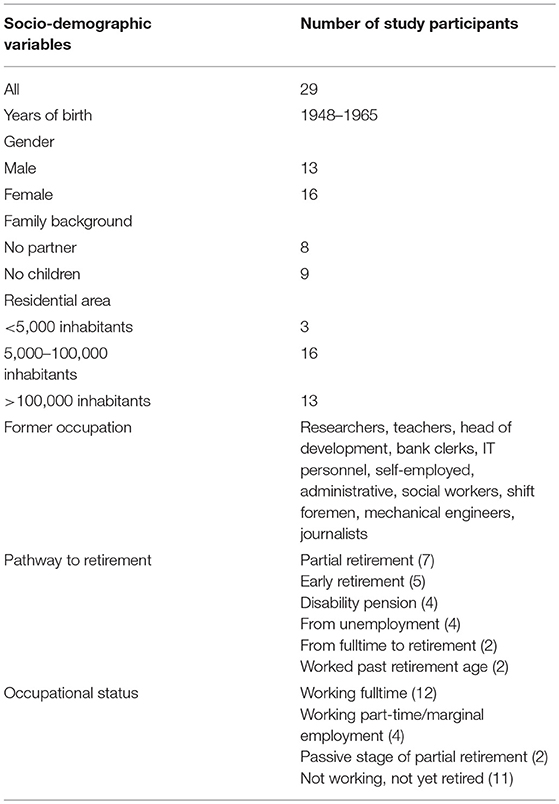

Beyond the formal selection criteria, an equal gender balance, as well as heterogeneity in regard to marital status and childlessness, educational attainment, former occupations, and pathways to retirement (e.g., from unemployment, partial retirement) were considered. As this paper focuses on the first wave of data collection that took place before respondents were formally retired the interviewed persons did not yet receive an old age pension. However, more than one third of them were not working anymore due to becoming unexpectedly unemployed, being offered a “golden handshake” or being on the pathway of partial retirement (see below). Table 2 portrays the characteristics of the final sample of 29 useable interviews.

Pathways to Retirement in the German Pension System at a Glance

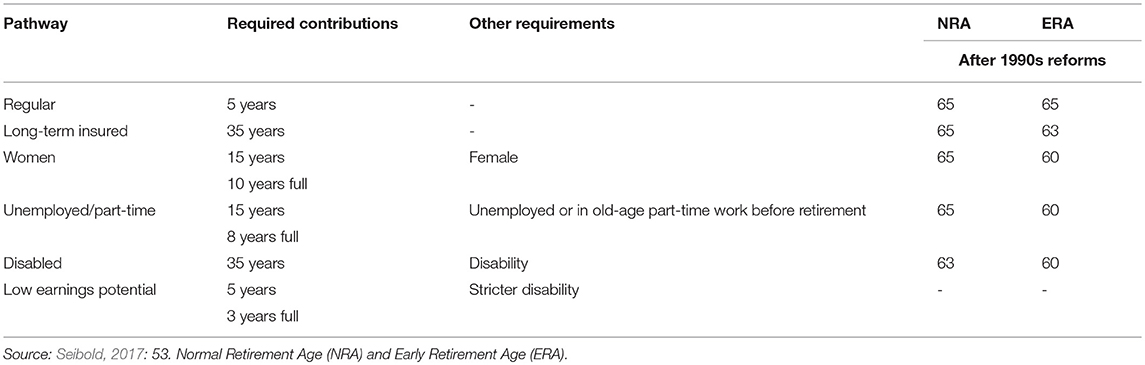

To understand the different pathways to retirement found among the sample, I will provide a brief overview about the German pension system and its legal retirement routes.

German retirement legislation has undergone partly paradoxical developments. In Germany, the public pension system covers the vast majority of the labor force, as enrollment is mandatory for private-sector employees. Most self-employed and civil servants are exempt. Benefits are defined according to a point system based on lifetime contributions. The major and long pension reform process that started in 1992 has radically changed the provisioning of public pensions, moving from a defined benefit scheme to a defined contribution scheme (Bonin, 2009). One of the final vital components of this process was the lifting of the statutory retirement age to 67 years until 2029, which, together with the closures of many early exit options, has increased involuntarily extended working lives (cf. Hofäcker and Naumann, 2015).

Different pathways to the public pension system exist, as portrayed in Table 3 in the appendix (source: Seibold, 2017, p. 53). The earliest possible age to receive retirement benefits is 63. Whereas, some routes to retirement have been closed, others are being opened: On the one hand, the closure of early exit options comprises, for example, also partial retirement, which ran out in 2009; however, companies may still offer this option to their employees. In Germany, two kinds of partial retirement pathways existed—one in which persons would gradually decrease their working hours over the period of 6 years, and one in which persons would continue to work fulltime for 3 years and not work at all but receive 80% of their former income for the subsequent 3 years. On the other hand, the recently introduced “Flexirentengesetz” (flexible retirement law) has broadened the range of retirement options before and after statutory retirement age, again with the aim to create individualized retiring transitions (OECD, 2017b). This is predicted to increase pension inequality in the future (OECD, 2017a) as in Germany, no basic or minimum pensions exist. The pension gap between men and women (46%) is largest in Germany from all OECD countries and the poverty rate among 65+ year old women 11.5% compared to 6.8% among men.

Data Collection and Analysis

The first wave of data collection comprised a face-to-face interview and 7 days of activity and photo diaries that the participants kept after the interview and sent back by mail or e-mail. The face-to-face interviews were mostly narrative but based upon a guideline that provided rough orientation questions. The interviews would begin with an open narrative-biographical invitation to elaborate on their occupational histories, starting—as work trajectories were the focus of the interview—with their education (however, many people did refer to their childhood and parents, as well as to their private lives in the course of the interviews). After this narrative period, which would last for ~45 min, participants were asked more specifically about retiring—including questions on how and when they first thought about retiring, what they think will change when they retire, what they plan to do in their retirement, which retiring processes they observe among their peers and what they would advise others who think about retiring to do and consider, as well as what a typical week in their lives looked like.

Interviews lasted between 60 and 180 min, with 90 min being the average duration. Participants would choose the interview location, resulting in altogether 20 interviews that were conducted at the university, 6 at the participants' homes and 2 that were conducted at the participants' workplaces.

This paper draws on the fully coded interview material of the first data collection wave, hence comprising persons in their pre-retirement stage. Data were coded using data analysis software MAXQDA 12. Data analysis was conducted based upon the documentary method for one-on-one interviews (Nohl, 2017) that was developed to interpret interviews on a practice-theoretical foundation, reflecting routine, and implicit knowledge involved in everyday practices (Bohnsack, 2014). The method involves two steps of data interpretation: first, the formulating interpretation aims at establishing what the interview text is about; second, the reflecting interpretation is concerned with how something is developed and presented (modus operandi). The analyses presented in this paper are mainly based upon the first step of data interpretation.

Results

The results portrayed in the following are divided into two sections according to the above-listed questions that a practice-theoretical perspective guides us to ask. They address the question of how retiring is being done and which social practices it involves for which groups of persons. The results section will address the questions

(i) How is retiring being done? What social practices does it involve?

(ii) How are these practices scattered across time, space, and carriers?

(iii) What are the underlying structures that organize the retirement transition process?

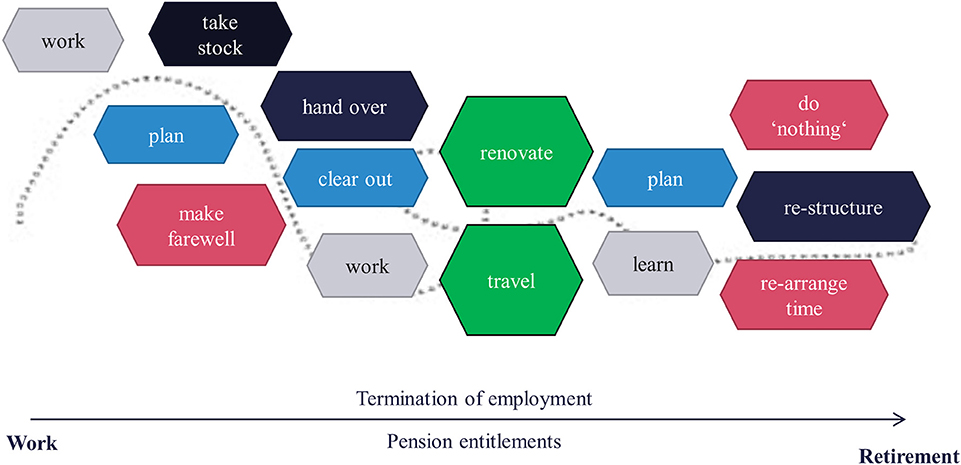

Targeting the first of these questions, my interview partners experienced a distinct set of sequentially organized practices that marked the beginning of their retiring process: taking stock, finding a successor, cleaning out their workplaces, organizing farewell celebrations and planning for retirement (Figure 1).

These practices and their spread across time, space, and carriers shall be discussed in detail in the following sections.

Re-mapping Everyday Lives: Changing Time-Spaces in the Retirement Process

Retiring is a transition that implies changes in the temporal and spatial structuration of everyday lives, away from workplaces and working hours. Despite retiring via different pathways, many participants stated to have reduced working hours before retiring. This reduction took place for different reasons both on the side of the employer and the employee, ranging from care-dependent relatives to illnesses and rehabilitation, to forms of partial retirement pathways in which a continuous reduction of working time was part of the regulation. Marie-Kristine, a social education worker, took 1 day a week off when her youngest son went through a difficult time in adolescence. She said that reducing her working hours by just 1 day “made a huge difference. I developed a more distanced perspective on work.” Monica, a legal expert, was diagnosed with cancer and had to stop working while she was doing chemotherapy. She told how she returned to work after rehabilitation, saying “But by that time I had taken a step back from work, realizing that leisure is, of course, an important asset” (Monica, *1959).

Besides reducing working hours, some participants reduced the time they would be physically present at their firms by working increasingly from their homes, which lead to a certain affective disengagement from work as well. Some participants who went on partial retirement described working “on call” from their homes. Petra, an accounting clerk in her active period of partial retirement, said: “I had talked to the director, he said, I said,' how many people have you called at in the past?'; he said,' Not a single one (laughs)” (Petra, *1955).

On the contrary, participants talked about former colleagues who would show up at the workplace all too often after they had been retired, who would still use the canteen or hang around the company building. This was often frowned upon and labeled as “not healthy.” Hence, the retiring sequence also implied a clear spatial sequencing: one could legitimately be less present at the workplace before retiring, but one would definitely have to stop being present at the workplace after retiring, implying a normative temporal-spatial structure of retiring practices.

Reducing working hours or doing home office would often lead to affective disengagement from work without participants having anticipated this effect. Other practices, however, were deliberately planned to mark the disengagement from work and the boundary between work and retirement. Those practices would often also imply a change in space: Many participants would materially mark the end of working life by planning to refurbish their homes or even move. Others planned to go on a longer vacation right after they would retire, often leading them to far-away places like Australia or New Zealand, if they could afford to go. Tess, working in a tourism agency, told me about her retirement journey plans:

“When I will have stopped working, 8th of December will be my last day of work (.), and on the 16th of December I will fly to Lanzarote and be there for 7 ½ weeks (laughs) […] to a small finca in a nature reserve […] I will completely seclude myself!” (Tess, *1956)

Those traveling plans were framed as celebrations of future retirement and are thus transformative practices. They would often be observed with one's partner, children, or friends, so that we can understand retiring practices as not only temporally and spatially dispersed, but also involve more than the retiring individual.

Retiring as Collective Accomplishment

Many of those practices suggest that retiring is not only a practical accomplishment, but a collective practical accomplishment that involved a variety of persons—from family members to colleagues, friends and successors. Tom, a design engineer, describes the thoughts that went through his head when he started thinking about retiring as follows:

“When are the children moving out, when can you do what you want to do, how old is your wife, what's next, what do you want to do with your life? Do you want to start new things at some point? And if you can afford to quit working, I mean, that was the easiest of all, to calculate that.” (Tom, *1958)

Among the study participants, it was particularly the men who expressed worries about how their wives would react when they retired, often packing those thoughts into jokes—like Harald (*1955), who talked about his wife retiring prior to him: “(laughs) She said (.): You keep working, I want a rest from you!” Others were talking more seriously about it, as Jessica, a bank clerk, asked herself: “What does it mean when both (.) who have been working the whole day and then suddenly one gets an offer to stop working early, what does it do to the other person?” Herbert, however, told how his wife pressured him to finally retire, and argued with him based on others in his circle of acquaintances, saying: “Well, my wife kept arguing: HE is already at home, HE only had to work until 4 p.m. each day anyway, YOU always work until 7 […] Why don't you finally retire, too?” (Herbert, *1954).

Whereas, partners were more often framed as factors involved in retiring earlier, children were usually referred to as a reason to continue working—often because they had not finished school yet, were studying and needed financial support. Others also mentioned that they would not want their children to worry about them, once they would not “do anything anymore.” Anna, a school teacher working past statutory retirement age, had lost her husband to cancer and explained:

“For a long time I was still thinking, I wanted to prove to my children, now that my husband isn't there anymore, that I could continue to work. That life consists (laughs) of work and not of lingering around. That was important to me. […] that they saw, our mother, she still has a purpose. She's still going to school.” (Anna, *1949)

Beyond family, the companies—supervisors and colleagues—played central roles in the practices of retiring. When he signed up for a partial retirement scheme, Tom was invited to a retirement counseling seminar organized by his company. In this seminar, 20 people from all across different departments that planned to retire came together to discuss their situations, plans, and fears.

“It makes you see, I am not alone in this situation, which I knew I wasn't, but it gets a different meaning when you experience it live. Well, they are all from the same company, but from completely different corners of course, right? You see, the people are completely different but we all share the same situation. We're going towards a transition to a different, new stage of life, yes…” (Tom, *1958)

Another core practice that constituted the retiring process was finding and establishing a successor. This was a task many persons described as a year-long process that had started long before other retiring practices. Sometimes, successors were found and built up, and then left the company again before the study participant was retired, starting the successorship process all over again. Sometimes participants chose and tried to establish a successor, but failed, because a new supervisor would establish a different person, or the study participants would learn that their position would not be filled after their retirement. This was a painful experience for those who went through it. If establishing a preferred successorship worked out, however, it turned out to be a huge motivational factor for employees at the end of their working lives. Roland, born 1953 and owning a small sales shop, had already “emotionally retired,” he said, when his son suddenly decided to take over the family business.

“Well, as I was 56, 57 (.) before my son entered the business […] I was thinking, well, you can get the next couple of years over with somehow. (.) Well, a little demotivated I would say […] And when he [note: his son] entered and, say, seriously wanted to take over the business, that breathed new life into me and motivated me a little more, to, um, actively go about certain things.” (Roland, *1953)

Farewell practices were another set of important collective practices in the retiring process. Dana, a middle school teacher, was currently planning her farewell party together with several colleagues who would retire the same year when I interviewed her. She referred to it as “Kick-Off” and said: “Yes, sure, we'll celebrate. We'll have a well-planned finish” (Dana, *1954). For others, if they worked in bigger enterprises, the firm would organize a relatively standardized farewell, often including a wine reception at an event room in the company building. Ulrich, who works at a big software firm, referred to it as “the usual” (Ulrich, *1955). Tina, who works at a marketing firm, described her farewell in a similar way that many others at bigger companies did:

“I didn't want one [a farewell celebration], not at all. But I have a supervisor, (.) yes (.), who is significantly younger than me. She wanted it by all means. She says, no, we have to do that. And then (.) they arrange a, such a reception, at noon, at twelve (.), they serve snacks and there are speeches and no alcohol, that's not allowed […] and the managers come and hand you cards and flowers. The colleagues collect money for a present (laughs). […] I have been through this when others retired, that's how I know, yes. I did bid farewell to colleagues and I held farewell speeches, yes.” (Tina, *1955)

However, not all participants were able to process through those stages. Particularly those who were dismissed at short notice or who suddenly stopped working for other reasons did not engage in the above-mentioned practices. They often suffered from not being given the chance to have a farewell ritual with their colleagues or prepare for the end of their working lives in other ways. This implies that there is a chrononormative sequencing of retiring practices that makes retiring “normally” a highly exclusive accomplishment.

The “Right Time to Retire” in the Chronormative Life Course

How do practice sequences “hang together” in the retiring process? Parts of the links and underlying structurations of retiring can be revealed by reconstructing practices and events that felt significant to future retirees in the separation stage. When asked about how and when they first started thinking about retiring, participants answered by reference to (a) chronological age, (b) life-course time or (b) lifetime left until death. Some participants could tell an exact chronological age by which they wanted to retire, or a number of years they would still have to work to afford retirement—even though those plans did not always work out. Harald, working in data processing, described how he had made a plan with his wife for when both of them would retire:

[…] our, my goal had always been to retire with 55, then she'd be (.) just over 60, so she's five (.) six years older (deep breath). That has always been my goal. Well, she finally did it with 62 (deep breath), and I was still working at 55.” (Harald, *1955)

Others claimed they had been thinking about retiring for all their working lives. Ulrich, a software engineer, said:

“I have been thinking about it [retiring] all my life (laughs). I used to have such, such, such a joke […] I told my colleagues: I will work ten, fifteen more years, and then I'll stop. (.) Well, that turned out to be illusionary, but […] in so far it didn't happen overnight…” (Ulrich, *1955)

Instead of referring to chronologically timed and expected “events” like reaching a certain age, some study participants linked their retiring thoughts to specific practices, events and situations that they framed as “happening” to them. Even though not all of these events were related to time, a surprisingly common story among the participants went like this: originally, they had not considered retiring (early), but then a person in their circle of friends and acquaintances died at a rather young age, and thus did not have time to realize all the plans they had had for retirement. This, then, got the participants thinking about how much time they had left in their lives, and if they wanted to spend that time working or self-determined. Dana talked about deaths and illnesses she had observed among her social contacts like this:

“[…] I've had diverse (.) experiences in my social environment. An (…) acquaintance, she's not a friend, but a good acquaintance, (.) that also went until the end [note: until statutory retirement age]. And she was retired for three months, (.) and developed (.) cancer. (.) And half a year later, in March, (.) we (.) buried her. Yes, this does something inside you, to get you thinking: Gosh, who can ensure me that I will live to be 90 years old, like my mother? It can happen to me as well; an extremely healthy woman, organic lifestyle, everything, yes. (.) And, um (.), yes, there is (.) another colleague, a similar thing happened to him. He was retired for two, three years and developed a chronic illness. (.) A year later (.) he was gone. (.) And that got me thinking: okay, you can feel well now at work, (.) but (.) what happens when an illness takes you by surprise and then you cannot enjoy your retirement the way I envision it?” (Dana, *1954)

Life-course time, time left, and chronological age, hence, were referred to in the retiring process, constructing chrononormativity through a “right time to retire.” This “rightness” was defined by chronologically locating oneself in an imagined linear life-course, hence assessing the time “behind' and “in front of” this location. However, some participants deviated from this chrononormativity of the life course and could, consequently, not participate in the chrononormative sequential structuration of retiring.

Deviating From Chrononormativity—A Closer Look

Many of the study participants could not plan for the end of their working lives, as they were dismissed at short notice or were suddenly diagnosed with a severe illness.

For example, Robert, born in 1953, was a former shift foreman who lost his job in his 50s because he had been attacked by a drunken colleague and complained to his supervisor about it, who, in turn, dismissed him. At first, Robert was confident he would find another job because he had managed with different petty employment positions throughout his entire life. He said he tried hard and would have taken any job he could get, but finally, he went on welfare and received Hartz IV7. In 2007, he started to take psychotherapy to cope with feeling “dehumanized and degraded.” At one point, he says, he could not stand it any longer and “faked” a burn-out to become eligible for disability pension.

“[…] and at this time I just simply got this (.) so-called burn-out (.), more or less willingly or also partly, uhm (.) constructed (…). This was accompanied by an external examination that was commissioned by the unemployment agency at that time (.) meaning that I was (.) examined (.) even though today I wouldn't be able to remember his name (.) of the man who did that (.) but to whom I played convincingly that he was positive that I am not able (.) to work more than three hours a day (…) and that was the trigger that made the unemployment agency say you have two possibilities: either you apply for a disability pension or we do it for you […]” (Robert, *1953)

Hence, Robert was caught in a status in-between not working anymore and not yet being retired. This “liminal phase” felt unbearable to him and had him initiate an event that would transit him into retirement and out of liminality. In “faking” a burn-out to claim disability pension benefits, he tinkered with chrononormativity and “fast-forwarded” to his retirement.

Whereas, the stage of being “in-between” felt unbearably long for Robert, it was surprisingly short for others, often in more privileged positions than Robert. Many of them were aghast when they received a letter or phone call offering them an early retirement scheme. Herbert, born in 1954 and CEO of a big company, was offered a “golden handshake” by his company when he turned 60, and felt this offer was not to be declined.

“And, ugh, so, well, ugh, when I turned 60, there was a restructuring at [company name] (.) where the put the next generation, in their forties, in power. (.) And, uhm, in this context they offered the possibility, uhm, of accepting, uhm, early exit arrangements…” (Herbert, *1954)

Jessica, the bank clerk, describes how her company was going through a restructuring process, pushing digitalization, and decreasing personal customer contact. In this process, all birth cohorts between 1956 and 1958 were offered partial retirement. They had received a letter from human resources, inviting them to an information evening for which the company invited counselors from the German pension insurance and prepared the partial retirement contracts that employees should sign right away. Even though this process seemed rather forced than voluntary, Jessica explained that she had had thoughts about retiring before, and that these thoughts were being “stimulated” by invitation. Others who had made similar experiences would do the same, framing the offer as a “trigger” or “eye opener” to embrace the option of early retirement.

But deviating from chrononormativity did not necessarily cause surprise or suffering among the study participants. Charlotte, born in 1957, was a trained biochemist who monitored clinical trials for pharmaceuticals as a freelancer. She grew increasingly frustrated with her work, and, with different legislative reforms, it got harder and harder for her to receive direct assignments as a freelancer, as many companies turned to temporary employment agencies instead. Asked about when and how it came that she retired, Charlotte replied:

“Um, I mean, I hadn't thought about it really. I would just have continued working. My plan was to definitely continue until I reached my 60s. (.)And, um, I simply didn't receive any direct assignments anymore and then I, I don't know, I started beekeeping (laughs) (.) And, um, that felt so good, because I was somehow totally relaxed and, um, became a completely different person, well (…)And (…) yes, I did continue to search for work in the beginning. […] And then I counted the dough and realized it's enough. And I thought, so, you take this as a present for yourself now.” (Charlotte, *1957)

Just like Robert, Charlotte became unemployed without realizing this might mark the beginning of her retirement. In the stage in-between working and being retired, she started other activities that made her feel better than her work did. At some point in this process it became apparent to her that she would not continue to work anymore. When the interview was conducted, she did not yet receive pension benefits, but she had subjectively come to terms with the status of being retired, and experienced this subjective change of status as a gift.

So even though there might be a shared notion of a “right time to retire” in the chronormative life course, deviations from this chronormativity were rather widespread. How these perceptions were assessed and expressed, however, and how the liminal stage of being between working and retired was experienced, differed greatly. Often it was even hard to tell when the separation phase of retiring had actually started, making retiring a process with blurring boundaries.

Discussion and Practical Implications

With increasing changes in the work-retirement landscape, research is confronted with the need for, and opportunity to, re-think theories on the transition from work to retirement (Phillipson, 2018). This paper does so by proposing a practice-theoretical perspective on the retiring process. Such a perspective, I argued, critically challenges core assumptions of both disengagement and rational choice theories. It understands disengagement from work as a practical accomplishment and choice as a situated practice in that process. Approaching the retirement transition from a practice-theoretical perspective implies (a) viewing it as a process of change that is (b) assembled by social practices that are (c) scattered across time, space, and carriers. Results from the “Doing Retiring” project exemplify these practices and their temporal, spatial and social distribution.

This paper has focused on the beginning resp. separation stage of the retiring process (cf. van Gennep, 1960), asking which social practices constitute the retiring process, how they are scattered across time, space, and carriers, and how they are organized. Now what does a practice-theoretical approach toward this topic makes us see that other approaches, like disengagement and rational choice perspectives, don't? At this moment, results can only provide a basis to formulate sensitizing concepts that suggest directions along which to look, and which may further be tested, improved, and refined (cf. Blumer, 1954). First, practice theories sensitize us for the fact that retiring is a process that is much more complex than is often depicted in existing theories. It involves a whole re-structuration of everyday lives.

Second and accordingly, the beginning of retiring can be traced to practices of temporal and spatial withdrawal, like reducing working hours or working in home office. Such practices that involve temporal and spatial changes are often transformative. This means that they contribute to a shift in personal identification from being part of the workforce to being a retiree. They may do so through affective disengagement or marking a boundary between working and retiring, as is the case with traveling and refurbishing. A transformative practice within a transitional sequence of practices, hence, is a practice with a specific “teleoaffective structure” (Schatzki, 1996). According to Schatzki, such teleoaffective structures comprise the aims (telos) a practice unfolds toward and the affects it activates to reach this aim. This is not to be confused with intentionality of a person, but is inherent part of a social practice. The teleoaffective structure of transformative practices in transition processes consequently aims to transfer its participants from the separation stage to the liminal stage and, finally, the incorporation stage of a transition. In the case of the retirement transition, reduction in working hours can have this transformative function when it leads to affective disengagement and subjective estrangement from work, and so can a longer vacation, which might itself mark the beginning of liminality.

Third, retiring is a collective accomplishment, involving many more actors than the retiring individual. Retiring as a collective practical process engages family members and employers, colleagues and friends, and collective practices like farewell celebrations or finding and establishing a successor. Retiring can, hence, be understood as a multi-agential, practical process, and the agency to retire is always distributed across this network (Latour, 2005) that makes up retiring: workplaces, companies, colleagues, partners, children, finances, homes, hobbies, friends and acquaintances, imaginaries and discourses on retiring, health and illness, pension insurances, employment agencies, etc. Once initiated, the practical process of retiring unfolds among this network.

Fourth, retiring practices are molded by a specific spatio-temporal ordering—they are situated in time and space and signify “normality” and deviance through their right or wrong placing and sequencing. Just as there are normalized and legitimized retiring ages, there are normalized and legitimized spaces in which working and retired persons are allowed to dwell (e.g., the workplace being a space exclusive to the present workforce). As Riach et al. (2014) suggest, it is, however, particularly fruitful for research to focus on those who “violate” chrononormative life course expectations, like Charlotte and Robert. Their stories reveal ways in which chrononormativity might be “undone,” offering the potential for resistance. However, they also clearly depict how being denied a farewell from working life that was perceived and framed to be double-sided and “normally” located in time and space can lead to the “undoing” of participants' identities themselves, by being marginalized, excluded and rejected (cf. Butler, 2004).

Exploring deviations from chronormativity from a practice-theoretical perspective can also help to re-conceptualize voluntariness and choice in the retiring process. It involves, I argue, several shifts in perspective: First, retiring is neither a binary variable of “voluntary” nor of “involuntary,” as it is often treated in quantitative research (cf. Dorn and Sousa-Poza, 2010), but in/voluntariness represents a continuum. This continuum becomes visible when we compare transition processes of different individuals, like that of Robert and Charlotte, who were not able to find work anymore despite wanting to, with that of Jessica, who was offered early retirement by her company, or that of Anna, who continued working to be a good role model for her two children. However, we can also find aspects of in/voluntariness in the transition process of one individual person. Jessica, for example, framed the (involuntary) offer of an early retirement scheme by her company as a trigger that initiated her wish to retire in the first place. Consequently, what is being described in retrospect as “voluntary” or “involuntary” is labeled as such in the narrative practices of—in this case—an interview. These narrative practices, in turn, construct life-courses in retrospect and older-age identities for the future retirement stage. Herbert, whose wife wanted him to retire, poses another example for the mixture of in/voluntary practices within one and the same retirement experience. Understanding retiring as a collective accomplishment, the decision to retire must consequently be seen as shared among various actors.

From this follow clear, practical implications that aim to prevent retirement (identity) scarring (Hetschko et al., 2014) of older workers. These implications target both employers and non-profit organizations and call for a process-oriented transition management that starts at the separation stage. Such a kind of transition management may include the following aspects: First, possibilities for fading out of work (e.g., reducing hours, working from home) should be diversified and made more easily accessible to a wider range of employees, as these seem to smooth over the transition process. Second, successorship processes should be facilitated by supervisors and working teams; and the retiring person should be actively involved in these processes. Third, understanding retirement as multi-agential calls for the establishment of communities of practice through, for example, retirement counseling groups across one or more companies (cf. Lave and Wenger, 1991). Finally, farewell celebrations should be supported as transitional rituals (cf. Prescher and Walther, 2018).

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of name of guidelines, name of committee with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Frankfurt, Department for Educational Sciences.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank my colleagues at the research training group Doing Transitions as well as the researchers at the DEMAND Centre, Lancaster University, for countless fruitful discussions on this work.

Footnotes

1. ^There are not few exceptions to this depiction, which I will go into more detail in the course of this paper.

2. ^See more on the retirement definition used in this paper and its problems in section Discussion.

3. ^Other decision-based theories, like the theory of planned behavior (cf. Ajzen, 1991), will, for reasons of simplification, be subsumed under the rational choice paradigm here.

4. ^http://www.doingtransitions.org

5. ^In the end, one person aged 53 years was also included in the study due to the specificities of his retiring process.

6. ^This criterion was actually hard to meet, as it turned out that the point of time at which people felt they retired did not always match with the formal definition, and constellations between working and receiving pension benefits were quite diverse (see Results section below).

7. ^Hartz IV is the common term for a form of unemployment benefit in Germany paid after the first 12–18 months of unemployment, which has been heavily criticized for providing only for the lowest level of living conditions.

References

Adams, G. A., and Rau, B. L. (2011). Putting off tomorrow to do what you want today: planning for retirement. Am. Psychol. 66, 180–192. doi: 10.1037/a0022131

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision Proc. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Bohnsack, R. (2014). “Documentary method and group discussions,” in Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research, eds R. Bohnsack, N. Pfaff, and W. Weller (Opladen: Budrich), 99–124.

Bonin, H. (2009). 15 Years of Pension Reform in Germany: Old Successes and New Threats. IZA Policy Papers 11, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Available online at: http://ftp.iza.org/pp11.pdf (Accessed August 08, 2018).

Crawford, M. P. (1971). Retirement and disengagement. Hum. Relat. 24, 255–278. doi: 10.1177/001872677102400305

Cumming, E., Dean, L. R., Newell, D. S., and McCaffrey, I. (1960). Disengagement-A tentative theory of aging. Sociometry 23, 23–35. doi: 10.2307/2786135

Cumming, M. E. (1964). “New thoughts on the theory of disengagement,” in New Thoughts on Old Age, ed R. Kastenbaum (Heidelberg: Springer), 3–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-38534-0_1

Dorn, D., and Sousa-Poza, A. (2010). “Voluntary” and “involuntary” early retirement: an international analysis. Appl. Econ. 42, 427–438. doi: 10.1080/00036840701663277

Ekerdt, D. J. (2010). Frontiers of research on work and retirement. J. Gerontol. Series B 65B, 69–80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp109

Ekerdt, D. J., Hackney, J., Kosloski, K., and DeViney, S. (2001). Eddies in the Stream. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 56, S162–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.3.S162

Fasang, A. E. (2010). Retirement: institutional pathways and individual trajectories in Britain and Germany. Soc. Res. Online 15, 1–16. doi: 10.5153/sro.2110

Feldman, D. C., and Beehr, T. A. (2011). A three-phase model of retirement decision making. Am. Psychol. 66, 193–203. doi: 10.1037/a0022153

Freeman, E. (2010). Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Perverse Modernities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1215/9780822393184

Goodwin, J., and O'Connor, H. (2014). Notions of fantasy and reality in the adjustment to retirement. Ageing Soc. 34, 569–589. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12001122

Hastie, R., and Dawes, R. M. (2010). Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Hatcher, C. B. (2003). “The economics of the retirement decision,” in Retirement: Reasons, Processes, and Results, eds G. A. Adams and T. A. Beehr (New York, NY: Springer), 136–158.

Henkens, K., van Dalen, H. P., Ekerdt, D. J., Hershey, D. A., Hyde, M., Radl, J., et al. (2017). What we need to know about retirement: pressing issues for the coming decade. Gerontologist 58, 805–812. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx095

Henry, W. E. (1964). “The theory of intrinsic disengagement,” in Age with a Future, ed P. F. Hansen (Philadelphia, PA: Davis), 415–418.

Hetschko, C., Knabe, A., and Schöb, R. (2014). Changing identity: retiring from unemployment. Econ. J. 124, 149–166. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12046

Hochschild, A. R. (1975). Disengagement theory: a critique and proposal. Am. Soc. Rev. 40, 553–569. doi: 10.2307/2094195

Hofäcker, D., and Naumann, E. (2015). The emerging trend of work beyond retirement age in germany: increasing social inequality? Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 48, 473–479. doi: 10.1007/s00391-014-0669-y

Jansen, A. (2018). Work-retirement cultures: a further piece of the puzzle to explain differences in the labour market participation of older people in Europe? Ageing Soc. 38, 1527–1555. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17000125

Jex, S. M., and Grosch, J. (2013). “Retirement decision making,” in The Oxford Handbook of Retirement, ed M. Wang (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 267–279

Kohli, M. (1985). Die Institutionalisierung des Lebenslaufs. Historische Befunde und theoretische Argumente. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 37, 1–29.

Kohli, M. (2007). The institutionalization of the life course: looking back to look ahead. Res. Hum. Dev. 4, 253–271. doi: 10.1080/15427600701663122

Krekula, C., Arvidson, M., Heikkinen, S., Henriksson, A., and Olsson, E. (2017). On gray dancing: constructions of age-normality through choreography and temporal codes. J. Aging Stud. 42, 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2017.07.001

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Moen, P., Kim, J. E., and Hofmeister, H. (2001). Couples' work/retirement transitions, gender, and marital quality. Soc. Psychol. Q. 64, 55–71. doi: 10.2307/3090150

Moffatt, S., and Heaven, B. (2017). “Planning for uncertainty”: narratives on retirement transition experiences. Ageing Soc. 37, 879–898. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X15001476

Nohl, A. (2017). Interview und Dokumentarische Methode. Anleitungen für die Forschungspraxis. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-16080-7

OECD (2017a). Preventing Ageing Unequally. OECD Publishing. Available online at: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/preventing-ageing-unequally_9789264279087-en

OECD (2017b). Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators. OECD Pensions at a Glance. OECD. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/pensions-at-a-glance-2017_pension_glance-2017-en

Phillipson, C. (2004). Work and retirement transitions: changing sociological and social policy contexts. Soc. Policy Soc. 3, 155–162. doi: 10.1017/S1474746403001611

Phillipson, C. (2018). “Fuller” or “extended” working lives? critical perspectives on changing transitions from work to retirement. Ageing Soc. 1–22. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X18000016

Phillipson, C., Shepherd, S., Robinson, M., and Vickerstaff, S. (2018). Uncertain futures: organisational influences on the transition from work to retirement. Soc. Policy Soc. 1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1474746418000180

Powell, J. (2001). Theorising social gerontology: the case of social philosophies of age. Internet J. Inter Med. 2, 1–10.

Prescher, J., and Walther, A. (2018). Jugendweihefeiem im Peerkontext. Ethnografische Erkundungen zur Gestaltung eines Übergangsrituals am Beispiel des Rundgangs am Jugendabend. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung 3, 307–320. doi: 10.3224/diskurs.v13i3.04

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: a development in culturalist theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theor. 5, 243–263. doi: 10.1177/13684310222225432

Riach, K., Rumens, N., and Tyler, M. (2014). Un/doing chrononormativity: negotiating ageing, gender and sexuality in organizational life. Organ. Stud. 35, 1677–1698. doi: 10.1177/0170840614550731

Schatzki, T. (1996). Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511527470

Schatzki, T. (2002). The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Univ. Press.

Schatzki, T. (2010). Materiality and social life. Nat. Cult. 5, 123–149. doi: 10.3167/nc.2010.050202

Schröter, K. R. (2012). “Altersbilder als Körperbilder: doing age by bodyfication,” in Individuelle und Kulturelle Altersbilder: Expertisen zum Sechsten Altenbericht der Bundesregierung, eds F. Berner, J. Rossow, and K.-P. Schwitzer (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 153–229.

Seibold, A. (2017). Statutory Ages as Reference Points for Retirement: Evidence from Germany. London School of Economics. Available online at: http://www.iipf.org/papers/Seibold-Statutory_Ages_as_Reference_Points_for_Retirement-440.pdf (Accessed August 08, 2018).

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., and Watson, M. (2012). The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and Ho' It Changes. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781446250655.n1

Steiber, N., and Kohli, M. (2017). You can't always get what you want: actual and preferred ages of retirement in Europe. Ageing Soc. 37, 352–385. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X15001130

Szinovacz, M. E., and DeViney, S. (1999). The retiree identity: gender and race differences. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 54B, S207–S218.

van Solinge, H., and Henkens, K. (2007). Involuntary retirement: the role of restrictive circumstances, timing, and social embeddedness. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 62, 295–303. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.5.S295

Vickerstaff, S., and Cox, J. (2005). Retirement and risk: the individualisation of retirement experiences? Soc. Rev. 53, 77–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00504.x

Wang, M, and Shultz, K. S. (2010). Employee retirement: a review and recommendations for future investigation. J. Manag. 36, 172–206. doi: 10.1177/0149206309347957

Wang, M. (ed.). (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Retirement. Oxford Library of Psychology. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Keywords: retirement, transition, practice theories, critical gerontology, chrononormativity

Citation: Wanka A (2019) Change Ahead—Emerging Life-Course Transitions as Practical Accomplishments of Growing Old(er). Front. Sociol. 3:45. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00045

Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 20 December 2018;

Published: 14 January 2019.

Edited by:

Andrzej Klimczuk, Warsaw School of Economics, PolandReviewed by:

Benjamin W. Kelly, Nipissing University, CanadaStefanie König, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Copyright © 2019 Wanka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna Wanka, d2Fua2FAZW0udW5pLWZyYW5rZnVydC5kZQ==

Anna Wanka

Anna Wanka