- Centre for Gender and Development Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

Concerns over women's marginalization and invisibility in Africa policy-making, remains a fervent international discourse. These concerns are likely due to restrictive laws, cultural diversities and practices, institutional barriers, as well as disproportionate access to quality education, healthcare, and resources. Reversing these discriminatory practices is not impossible, and can be achieved by implementing the right mechanisms across the continent. The process toward increasing the visibility of women in decision-making across the continent, requires an understanding of the progress made so far, the challenges faced and the way forward. As a consequence, this paper conducted a review of literature to determine the key decision-making organs in Africa, the current status of African women and women's organizations in decision-making, existing institutional policies demanding female involvement in decision-making and the progress made in the continent so far. This paper will also provide recommendations to accelerate the way forward in view of Agenda 2030.

Introduction

The African continent is one of the largest and most populous on earth (Abu-Aisha and Elamin, 2010). It is ~11.7 square miles (30.3 million km2) including its adjoining islands. The continent covers 6% of the earth's surface which attributes to 22% of the world's total mass. Its northern part is the world's hottest desert. The Nile River, which runs through 11 different countries; and Lake Victoria, is located in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. Karinen et al. (2008) affirmed that Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest point (about 19,340 feet) and Lake Asal, Djibouti is the lowest point (about 502 feet below the sea level) on the continent. The Continent is surrounded by: the Atlantic Ocean in the West; the Indian Ocean in the East; the Southern Ocean in the South; as well as the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea in the North.

Africa has 55 countries, nine territories, two individual states, varied ethnicities, and vast cultures and languages (Barth, 1998). It has the highest level of multilingualism in the world and consist of many different native groups and over a thousand languages. It is also rich in history, geographic diversity, economic, and governmental systems. Globally the continent has the largest population of youth, while women, with economic, social, and cultural diversity, account for approximately half of the population of the African continent (Shisana et al., 2009).

Despite its rich heritage and numerous natural resources (Viljoen and Reimold, 1999), Africa is the poorest and most underdeveloped continent globally (Mazrui, 1980). On average, it is the poorest continent on earth (Crook, 2003; Deaton, 2006; Fox, 2010). Women minimally participate in decision-making and mostly bear the brunt of poverty across the continent. According to Chatterjee and Pramanik (2015) Africa has 25 nations of the poorest nations in the world. A large number of people in Africa are affected by poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition, inadequate water supply, poor sanitation and poor health (Chen and Ravallion, 2008). Each African region and country is independent of each other and do not fall into the African economical stereotype. Braithwaite and Mont (2009) and Chen and Ravallion (2010) claimed that efforts geared toward reducing poverty are the least successful in west and central Africa. The people in this sub-region live on only 70 cents a day (Chen and Ravallion, 2008).

Nigeria, for example, is still classified as a poor nation (Olawole and Alao) despite numerous government policies and resources, committed to alleviate poverty (Omotola, 2008). Many Nigerians lack access to good shelter, potable water, healthcare, and sanitation (Omotola, 2008). Nigeria has a steady increase in slum development and over populated labor market (Omotola, 2008) due to poor governance (Sanusi, 2011).

The continent has been destroyed by politics, bad governance, corruption, and gender imbalance in decision-making, for over a decade. This has culminated in serious abuses and violations of human rights, failed governance, poor health care, high levels of illiteracy, ineffective utilization of foreign aids, political instability, as well as frequent tribal and military conflict (Sandbrook and Barker, 1985). Deaton (2006) specifically noted that not only do African nations need to deal with extreme poverty, they also have lower life expectancy and a low chance of obtaining an education, which rings particularly true for women.

The foundation for the current status of African women, was laid by an Eurocentric educational system inherited from colonialism. This system, designed around formal education, was designed to nurture male dominance in paid employment, leadership, politics, governance, and decision-making. Thus, fostering gender discrimination in decision-making in Africa. To break these discriminatory trends in Africa, both Uganda (since 2001) and South Africa (since 1999) advanced the participation of a larger number of women in formal politics. Despite these accomplishment, Uganda's parliament is one quarter female, while women's presence in South African's parliament is approximately one third (Goetz and Hassim, 2003). McEwan (2003) also reported the underrepresentation of women within South African local government structures.

In view of this, this study will conduct a review of literature to determine the key decision-making organs in Africa, the current status of African women and women's organizations in decision-making, existing institutional policies demanding female involvement in decision-making, and barriers to women's involvement in the decision-making process in Africa.

Theoretical Approaches on Women's Visibility in Decision–Making

There are several approaches on female participation in decision-making in Africa. First is the women's human rights approach, which claims that since women are about half of the entire population in Africa, they have a right to be represented in decision-making (Boserup et al., 2013). Next is the critical mass theory, which claims that women would achieve solidarity of purpose for their interests and welfare if represented in decision-making (Oliver and Marwell, 1988; Fraser, 1990).

At the policy level, feminist theorists advancing a theory of congresswomen's impact on women's issues, suggest that women are a homogenous group who need to be represented in discussions that result in policy-making and implementation, as their experiences are unique and different from those of men (Young, 1989; Swers, 2002). This implies that women conduct politics differently from men. Feminists theorists also claim that women's interests differ from men's (Pateman, 2005), and therefore, should be represented in institutions to articulate their interests. From a mentor and role model perspective, feminist theorists state that female role models will enhance female involvement and engagement in politics, while equal representation of women and men in politics will results in democratization of governance at a national and international level (Campbell and Wolbrecht, 2006).

Conceptual Framework for Women's Involvement in Decision-Making in Africa

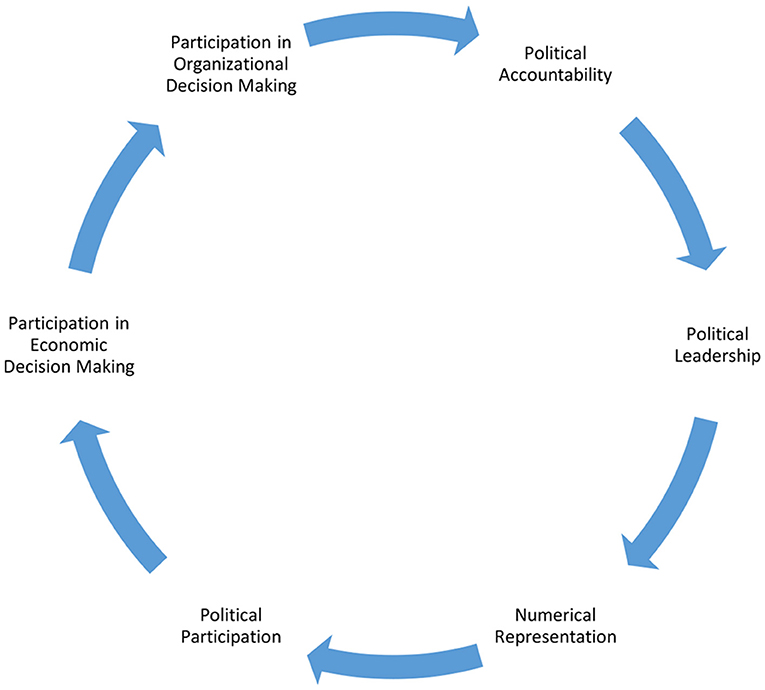

As shown in Figure 1 below, the conceptual framework refers to the cycle of women's empowerment and involvement in decision-making.

Below follows the inter-related conceptual framework for gender equity in decision-making processes:

a) Political Participation: This entails the development of political agendas and operational planning, detailing activities such as discussion, debate, lobbying, and activism that will engender women's equal participation in politics (Stokes, 2005).

b) Numerical Representation: In Nigeria, this may infer the utilizations of gender quotas for women's representation in decision-making based on a variety of dimensions such as constituency interests and ascribed interests such as ethnicity, religion, and ideological interests (Connerley and Pedersen, 2005).

c) Political Leadership: This entails women's participation and representation in appointive and elective party leadership.

d) Political Accountability and Commitment to GEWE issues: This refers to the visible implementation of gender equity and women's empowerment issues clearly stated in political parties' manifestoes.

e) Participation in Economic Decision-Making: This refers to women's participation in domestic or institutional financial decision-making.

f) Participation in organizational Decision-Making: This refers to women's participation in formulating and executing decisions concerning organizations.

Research Questions

1. What are the key decision-making organs in Africa?

2. What is the current status of African women and women's organizations in decision-making?

3. What are the existing institutional policies demanding female participation in decision-making in Africa?

4. What are the barriers to women's participation in the decision-making process in Africa?

5. What is the way forward?

Methodology

This study reviewed literature on the invisibility of female participation in decision making in Africa using Google scholar.

Results

Key Decision-Making Organs in Africa

The African Union (AU), bringing nations together and keeping them in check, emerged from the twentieth century processes of decolonization (Nathan, 2005), and is the current key decision-making organ across the continent (Franck, 1992). The Union, with headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is a federation of all African states (Mbeki, 2002).

Essentially, the Constitutive Act of the African Union (Kuwali and Viljoen, 2013) aims at transforming the African Economic Community into a state under established international conventions (Mbeki, 2002). The Constitutive Act states that all member States should have a 50 percent representation of women commissioners (Kuwali and Viljoen, 2013). Other mandates of the African Union include promotion and protection of human and peoples' rights as well as the interpretation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (African Union, 2003). The Commission also has six (6) special rapporteurs, eight (8) working groups, two (2) committees, and one study group that monitor, investigate, and report on specific human rights issues (Evans and Murray, 2008). Regardless of the existence of these decision-making organs in Africa, the lack of women's participation in decision-making as well as violations and abuses of women's human rights still persist (Mutua, 2013) in countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Côte d'Ivoire (Bulto, 2010).

The Status of African Women in the Decision-Making Processes

Many gender equality and women empowerment (GEWE) missionaries, non-governmental organizations, women's groups, and individuals have worked together in various national, international and transnational contexts to bring women and women's interests into government affairs (Ross, 2002; Rai, 2003; Devlin and Elgie, 2008) through efforts geared toward achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Agenda 2030 (Basu, 2018). Between 1995 and 2005, there was an upsurge in the visibility of women's involvement in leadership and decision-making in Africa. Zubeyr et al. (2013) claimed that the implementation of a gender quota system, resulted in an upsurge of the number of women who participated in public decision-making in Mozambique (34.8%), South Africa (32.8%), Tanzania (30.4%), Uganda, Burundi (30.5%), Rwanda (48.8%), Namibia (26.9%), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Rwanda, for example, has the highest percentage (48.8%) of women's parliamentary representation across the globe. Women's organizations in the Congo successfully lobbied the government to include the principle of a 50–50 parity representation, in the constitution in 2006 (Sow, 2012). In Burundi, the government included a quota for a 30 percent representation of women in the 2005 constitution and to the electoral code in 2009 (Sow, 2012). In Mali, Niger, and Cape Verde, priority funding was awarded to political parties with large female representation which ensured the nomination of at least 10% female candidates for either elective or appointive positions (Boakye Yiadom and Musa, 2010; Krook, 2015). In Sub-Saharan Africa, some female legislators were elected through gender quotas, which is a system of reserved seats (Yoon, 2001).

Despite these efforts and achievements in some African nations, variations in the degree of women's visibility in decision-making across the continent, ranging from <5% in Egypt to over 40% in South Africa remains (Yoon, 2001; Kunovich and Paxton, 2005). Similarly, Bawa and Sanyare (2013) observed a steady decline in women's involvement in public life and politics in nations such as Ghana. This decline is most likely sustained by gender insensitive ideologies which denote the private domestic sphere as the female domain and the public and political sphere as the male terrain (Geisler, 1995).

International Policy Framework

The need to visibly engender women's participation in decision-making became a growing global concern through the CEDAW—the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (United Nation General Assembly, 1979; Bareiro-Bobadilla et al., 2010) and its Article 7 which specifically requested State parties “to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the political and public life of the country” (Kathree, 1995). The 1997 Committee on CEDAW also put State parties under the obligation to ensure that their constitution and legislation complied with the principles of the Convention to achieve equal representation of women in political and public life (Lucia, 2006).

In 1995, the Beijing Fourth World Conference on Women, focused on the persistent exclusion of women from formal politics and decision-making. The Beijing Platform of Action (BPoA) (Declaration, 1995b) questioned the achievements of any form of effective democratic transformation in Africa, which violated women's rights to vote and be elected. The BPoA indicated that democratic institutions who lacked women's representation in political decision-making, cannot achieve gender equality in terms of representation, policy agenda setting and accountability. This implies that women's equal participation in decision-making is a necessary condition for women's interests to be taken into account (Declaration, 1995b). Without the perspective of women at all levels of decision-making, the goals of equality, development, and peace cannot be achieved. Thus, attainment of sustainable development in Africa will require the provision of equal access to and full participation of women in power structures and decision-making (Declaration, 1995b). The BPoA therefore proposed the following measures that could be adopted to accelerate women's organizations' visible engagement in decision-making for sustainable development in Africa:

a) Establishing gender-balanced governmental bodies, committees, public administration and judiciary, through specific targets and a positive action policy; integrating women into elective positions in political parties; promoting and protecting women's political rights; and reconciling work and family responsibilities for both men and women (Declaration, 1995a); and

b) Conducting leadership and gender awareness training; developing transparent criteria for decision-making positions; and creating a mentoring system (Declaration, 1995b).

The need for equal participation and fully involving women and women's organizations in conflict resolution and peacebuilding, were affirmed by the Security Council in resolution 1325 (2000) (Hill et al., 2003; Cohn et al., 2004; Tryggestad, 2009). In the same way, the 2003 United Nation General Assembly resolution 58/142 on women's political participation (Baetiong; Deliver et al; World Health Organization., 2005) also mandated governments, the UN system, NGOs and others, to develop a comprehensive set of policies and programmes geared toward increasing women's participation in decision-making, pertaining to conflict resolution and peace processes. This mandate was also further supported by the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) seeking equal participation of both women and men in politics, leadership, and decision-making (Krook and True, 2012).

Challenges

The following are some of the challenges faced in women's participation in decision–making processes in Africa:

a. Socio-demographic Barriers: These are factors such as age restrictions, gender norms and cultural practices which prevent women from participating in decision-making. Nzomo (1997) tied Kenyan women's limited participation in the competitive world of politics, to great responsibilities and heavy workloads associated with a woman's reproductive, domestic, and productive role.

b. Economic Barriers: Many African women usually lack the economic power necessary to fully participate in decision-making. Ballington and Matland (2004) suggested that women often lack the financial resources needed to fully participate in leadership and decision-making. Goetz and Hassim (2003) noted that circumstances of capitalist market relationships in poor countries have left women with little time and few resources for political participation.

c. Time Factors: Kiamba (2008) indicated that for many women, the time demands of such positions, conflict with the demands of the family and this in itself is a barrier.

d. Structural Barriers: There are also other international, local resistance and structural barriers to women's participation in decision-making (Kiamba, 2008).

e. Gender Stereotypes: This implies entrenched societal and systemic gender stereotypes, which often prevent women from participating in decision-making. Zimbabwe, for example, had the 1992 Gender Affirmative Action Policy, the 1999 Nziramasanga Commission, and the National Gender Policy of 2004, advancing gender equality and removing of all forms of gender-based discrimination in the nation. However, Chabaya et al. (2009) still found gender stereotypes and a lack of support at home and in the workplace, as some of the major causes of persistent under-representation of women in school leadership and decision-making.

f. Male Resistance: Men's resistance and non-preparedness to share political power and decision-making processes with women is a global phenomenon (Schein, 2001).

Recommendations

There is a dire need for substantive representation of women in decision-making positions in Africa, especially in the formulation of GEWE related policies and the mainstreaming of gender into existing policies, as well as plans and programmes aimed at explicitly advancing the gender equality agenda of the SDGs across the continent. Substantive presence of women is also needed as key decision-makers in policy formulation, aimed at achieving gender equality in development, sustainable peace, and good governance within African sub-regions.

There is also a need to visibly engage women's organizations in decision-making and transform partnering them with GEWE projects. Women's participation and representation in decision-making bodies in Africa should not only be a numerical enhancement of presence, but their empowerment for political leadership and accountability at all levels.

At national levels, state actors must be obligated to establish legal frameworks for the GEWE. Non-state contexts such as trade unions, political parties, interest groups, professional associations, and the businesses/private sector should also be involved in policy decision-making. There should also be an evolution of trans-national women social movements and engagement with the GEWE. In addition to decision-making, there is also the need for women to influence policies and strategies geared toward women's increased access to economic opportunities and effective participation in politics.

Conclusions

African women have only been marginally involved in decision-making. Creating opportunities for the institutionalization of women's visible involvement in decision-making in Africa will strengthen the acceleration of sustainable developmental goals on the continent. Consequently, governments of individual nations in Africa are expected to create an enabling policy environment and engagement strategies for the institutionalization of women's visible involvement in decision-making at all levels—families, communities, state wide and on national levels. There is also the need for international agencies to continue to support women's organizations' visible engagement in decision-making in Africa.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with the author OOI.

References

Abu-Aisha, H., and Elamin, S. (2010). Peritoneal dialysis in Africa. Peritoneal Dialys Int. 30, 23–28. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2008.00226

African Union (2003). Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People's Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa. Available online at: http://197.220.255.230:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/213/2/Protocol_Rights%20women%20in%20Africa.pdf.

Baetiong, A. Equitable Representation of Women and Minorities in Government. Available online at: http://munfw.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/MUNFW-65-HRC.pdf.

Ballington, J., and Matland, R. E. (2004). Political Parties and Special Measures: Enhancing Women's Participation in Electoral Processes. Paper presented at the documento preparado para. United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women (OSAGI), Expert Group Meeting on “Enhancing Women's Participation in Electoral Processes in Post-Conflict Countries.

Bareiro-Bobadilla, O., Jahan, I., and Helena, M. (2010). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Available online at: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/CEDAW/docs/CEDAW.SP.2010.4_en.pdf

Barth, F. (1998). Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Waveland Press. Available online at: http://www.bylany.com/kvetina/kvetina_etnoarcheologie/literatura_eseje/2_literatura.pdf.

Basu, A. (2018). The Challenge of Local Feminisms: Women's Movements in Global Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bawa, S., and Sanyare, F. (2013). Women's participation and representation in politics: perspectives from Ghana. Int. J. Public Administr. 36, 282–291. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2012.757620

Boakye Yiadom, B., and Musa, R. (2010). Creating Spaces and Raising Voices. Available online at: http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/34%20/ http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/34/http://www.awdflibrary.org/handle/123456789/34

Boserup, E., Tan, S., Toulmin, C., and Kanji, N. (2013). Woman's Role in Economic Development. London: Routledge.

Braithwaite, J., and Mont, D. (2009). Disability and poverty: a survey of World Bank poverty assessments and implications. ALTER-Eur. J. Disab. Res. 3, 219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.alter.2008.10.002

Bulto, T. S. (2010). “The indirect approach to promote justiciability of socio-economic rights of the African charter on human and peoples' Rights. (March 4, 2010),” in Human Rights Litigation And The Domestication of International Human Rights Standards in Africa. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1896127

Campbell, D. E., and Wolbrecht, C. (2006). See Jane run: women politicians as role models for adolescents. J. Polit. 68, 233–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00402.x

Chabaya, O., Rembe, S., and Wadesango, N. (2009). The persistence of gender inequality in Zimbabwe: Factors that impede the advancement of women into leadership positions in primary schools. South Afr. J. Educ. 29, 235–251

Chatterjee, D., and Pramanik, A. K. (2015). Tuberculosis in the African continent: a comprehensive review. Pathophysiology 22, 73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2014.12.005

Chen, S., and Ravallion, M. (2008). The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4703. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.168.949&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Chen, S., and Ravallion, M. (2010). The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty. Q. J. Econ. 125, 1577–1625. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.4.1577

Cohn, C., Kinsella, H., and Gibbings, S. (2004). Women, peace and security resolution 1325. Int. Femin. J. Polit. 6, 130–140. doi: 10.1080/1461674032000165969

Connerley, M. L., and Pedersen, P. B. (2005). Leadership in a Diverse and Multicultural Environment: Developing Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills. Thousand Oaks; London; New Delhi: Sage Publications. Available online at: https://books.google.com.ng/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Mzx2AwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Connerley,+M.+L.,+%26+Pedersen,+P.+B.+(2005).+Leadership+in+a+diverse+and+multicultural+environment:+Developing+awareness,+knowledge,+and+skills:+Sage+Publications.&ots=zc8YEYS0fY&sig=CHP-jqvWdqhBbMQkOittg9tdHcc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Connerley%2C%20M.%20L.%2C%20%26%20Pedersen%2C%20P.%20B.%20(2005).%20Leadership%20in%20a%20diverse%20and%20multicultural%20environment%3A%20Developing%20awareness%2C%20knowledge%2C%20and%20skills%3A%20Sage%20Publications.&f=false.

Crook, R. C. (2003). Decentralisation and poverty reduction in Africa: the politics of local–central relations. Public Administr. Dev. 23, 77–88. doi: 10.1002/pad.261

Deaton, A. (2006). “Measuring poverty,” in Understanding Poverty, eds A. V. Banerjee, R. Benabou, and D. Mookherjee (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 3–15

Declaration, B. (1995a). Platform for Action. Paper presented at the Fourth World Conference on Women.

Declaration, B. (1995b). Platform for Action (BPA). Paper presented at the 4th World Conference on Women.

Deliver, W., DeVoe, M., Dunn, L., Iversen, K., Malter, J., Papp, S., et al. Strengthen Women's Political Participation Decision-Making Power. Available online at: http://womendeliver.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Good_Campaign_Brief_8_092016.pdf

Devlin, C., and Elgie, R. (2008). The effect of increased women's representation in parliament: the case of Rwanda. Parliament. Affairs 61, 237–254. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsn007

Evans, M., and Murray, R. (2008). The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights: The System in Practice 198–2006. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Fox, A. M. (2010). The social determinants of HIV serostatus in sub-Saharan Africa: an inverse relationship between poverty and HIV? Pub. Health Rep. 125(4_suppl), 16–24. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S405

Franck, T. M. (1992). The emerging right to democratic governance. Am. J. Int. Law 86, 46–91. doi: 10.2307/2203138

Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: a contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Soc. Text 25/26, 56–80. doi: 10.2307/466240

Geisler, G. (1995). Troubled sisterhood: women and politics in southern Africa: case studies from Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana. African Affairs 94, 545–578. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098873

Goetz, A.-M., and Hassim, S. (2003). No Shortcuts to Power: African Women in Politics and Policy Making Vol. 3. Zed Books.

Hill, F., Aboitiz, M., and Poehlman-Doumbouya, S. (2003). Nongovernmental organizations' role in the buildup and implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325. Signs 28, 1255–1269. doi: 10.1086/368321

Karinen, H., Peltonen, J., and Tikkanen, H. (2008). Prevalence of acute mountain sickness among Finnish trekkers on Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: an observational study. High Altitude Med. Biol. 9, 301–306. doi: 10.1089/ham.2008.1008

Kathree, F. (1995). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. South Afric. J. Hum. Rights 11, 421–437. doi: 10.1080/02587203.1995.11827574

Kiamba, J. M. (2008). Women and leadership positions: social and cultural barriers to success. Wagadu 6, 5. Available online at: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-1657657541/women-and-leadershippositions-social-and-cultural

Krook, M. L. (2015). Gender and Elections: Temporary Special Measures Beyond Quotas. Social Science Research Council. Working paper. Availble online at: http://webarchive.ssrc.org/working-papers/CPPF/WomenInPolitics/04/Krook.pdf.

Krook, M. L., and True, J. (2012). Rethinking the life cycles of international norms: the United Nations and the global promotion of gender equality. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 18, 103–127. doi: 10.1177/1354066110380963

Kunovich, S., and Paxton, P. (2005). Pathways to power: the role of political parties in women's national political representation. Am. J. Sociol. 111, 505–552. doi: 10.1086/444445

Kuwali, D., and Viljoen, F. (2013). Africa and the Responsibility to Protect: Article 4 (h) of the African Union Constitutive act. London: Routledge. Available online at: http://debate.uvm.edu/idastraining2012/Resources/International%20Organizations/African%20Union%20Doc%201.pdf.

Mazrui, A. A. (1980). The African Condition: A Political Diagnosis. Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

McEwan, C. (2003). ‘Bringing government to the people’: women, local governance and community participation in South Africa. Geoforum 34, 469–481. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7185(03)00050-2

Mutua, M. (2013). Human Rights NGOs in East Africa: Political and Normative Tensions. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Nathan, L. (2005). Consistency and inconsistencies in South African foreign policy. Int. Affairs 81, 361–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00455.x

Nzomo, M. (1997). “Kenyan women in politics and public decision making,” in African Feminism: The Politics of Survival in Sub-Saharan Africa, ed G. Mikell (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pensylvania Press), African feminism: The politics of survival in sub-Saharan Africa, 232–256.

Olawole, O., and Alao, D. O. The Millenium Development Goals the Challenges of Anti-poverty Policies in Nigeria. Millennium Development Goals (MDGS) as Instruments for Development in Africa, 211. Available online at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/31078779/2.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1543623411&Signature=hXHhqod%2FU2PDTQEIJnmB7Lpq44g%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DLinking_the_Millennium_Development_Goals.pdf#page=221

Oliver, P. E., and Marwell, G. (1988). The paradox of group size in collective action: a theory of the critical mass. Am. Sociol. Rev. 53, 1–8. doi: 10.2307/2095728

Omotola, J. S. (2008). Combating poverty for sustainable human development in Nigeria: the continuing struggle. J. Poverty 12, 496–517. doi: 10.1080/10875540802352621

Pateman, C. (2005). “Equality, difference, subordination: the politics of motherhood and women's citizenship,” in Beyond Equality and Difference, (Routledge), 22–35.

Rai, S. M. (2003). Institutional Mechanisms for the Advancement of Women: Mainstreaming Gender, Democratizing the State? Mainstreaming Gender, Democratizing the State, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 15–39.

Ross, K. (2002). Women's place in ‘male’space: Gender and effect in parliamentary contexts. Parliament. Affairs 55, 189–201. doi: 10.1093/parlij/55.1.189

Sandbrook, R., and Barker, J. (1985). The Politics of Africa's Economic Stagnation. Cambridge, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sanusi, W. (2011). Effect of poverty on participation in non-farm activity in Ibarapa local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Apicul. Res. 7, 86–95.

Schein, V. E. (2001). A global look at psychological barriers to women's progress in management. J. Soc. Issues 57, 675–688. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00235

Shisana, O., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L., Zuma, K., and Jooste, S. (2009). South African National HIV Prevalence Incidence Behaviour and Communication Survey 2008: A Turning Tide Among Teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Sow, N. (2012). Women's political participation and economic empowerment in post-conflict countries: lessons from the great Lakes region in Africa. London: International Alert/Eastern Africa Sub-Regional Support Initiative for the Advancement of Women, 1–47. Avaiable onlinen at: http://www.internationalalert.org/sites/default/files/publications/201209WomenEmpowermentEN_0.pdf.

Swers, M. L. (2002). The Difference Women Make: The Policy Impact of Women in Congress. University of Chicago Press.

Tryggestad, T. L. (2009). Trick or Treat? The UN and implementation of security council resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security. Global Governance 15, 539–557. doi: 10.5555/ggov.2009.15.4.539

United Nation General Assembly (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Viljoen, M., and Reimold, W. (1999). An Introduction to South Africa's Geological and Mining Heritage. Randburg: The Geological Society of South Africa and Mintek.

World Health Organization. (2005). United Nations Road Safety Collaboration: A Handbook of Partner Profiles. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yoon, M. Y. (2001). Democratization and women's legislative representation in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization 8, 169–190. doi: 10.1080/714000199

Young, I. M. (1989). Polity and group difference: a critique of the ideal of universal citizenship. Ethics 99, 250–274. doi: 10.1086/293065

Keywords: Africa, decision-making, visibility, participation, women

Citation: Ilesanmi OO (2018) Women's Visibility in Decision Making Processes in Africa—Progress, Challenges, and Way Forward. Front. Sociol. 3:38. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00038

Received: 09 May 2018; Accepted: 14 November 2018;

Published: 11 December 2018.

Edited by:

Tolulope Jolaade Adeogun, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South AfricaReviewed by:

Robert Kelvin Perkins, Norfolk State University, United StatesFernando Salinas-Quiroz, National Pedagogic University, Mexico

Copyright © 2018 Ilesanmi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oluwatoyin Olatundun Ilesanmi, dG95dHVuZHVuQGVrc3UuZWR1Lm5n; dG95dHVuZHVuQGFvbC5jb20=

Oluwatoyin Olatundun Ilesanmi

Oluwatoyin Olatundun Ilesanmi