- 1Guangdong Key Laboratory for Urbanization and Geo-simulation, School of Geography and Planning, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

According to the United Nations, the proportion of the older population is increasing at a faster rate than all other age groups. Hence, the well-being of older adults is a mounting concern worldwide in the current century. Using a single greenery metric, previous studies linked greenness to residents' well-being. This study aims to extend this field by focusing on the mental and physical well-being of older adults by using remote sensing and streetscape metrics in evaluating neighborhood greenness. We selected 20 residential neighborhoods in Guangzhou City, China as the cross-sectional case study areas. We investigated neighborhood normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) collected using remote sensing images, streetscape greenery, and PM2.5 via field surveys. We assessed the health condition of 972 senior residents selected by multi-stage stratified probability proportionate to population size sampling technique (PPS) using a questionnaire survey. We adopted the structural equation model (SEM) in analyzing the pathways that link neighborhood greenness and the mental and physical health of older adults. We found that neighborhood greenness has a positive association with the physical activity by older adults that is positively linked to their physical health. Moreover, neighborhood greenness is positively related to regular social interactions among older adults that is positively linked to their mental health. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies. However, we obtained new results that were unique to China. We found that neighborhood greenness has no significant direct relationship with the physical and mental health of older adults and that social interactions of low-income senior groups are more substantially related to neighborhood greenness than the other groups. Therefore, community planning should emphasize the development of neighborhood greenness, such as parks and street trees, to provide natural spaces for social interactions and places for physical activities among older residents.

Introduction

The 21st century is an era characterized by aging and urbanization, and these characteristics are more prominent in developing countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the proportion of seniors (aged 60 years and older) to the global population will reach 22% in 2050 (1). Both the aging rate (Proportion of Population ages 65 and above) (2) and urbanization rate (Proportion of Urban Population) (3) in China, are higher than the global average. Improving the physical and mental health of the older adults in urban areas has become an important issue in China.

Numerous studies conducted in developed countries have demonstrated that greenspace exposure is related to wide-ranging health benefits, including better mental health and physical health (4–15). In terms of mental well-being, exposure of residents to greenspaces may enhance their feelings of happiness and relieve their stress from negative events (16, 17). In terms of physical well-being, exposure to greenspaces has an active role in reducing morbidity from multiple diseases (18–20). Several studies that focused on greenspaces in China explored the relationship between neighborhood environment and residents' well-being (21–25), which reported positive relationship between neighborhood greenspaces and residents' well-being, especially in terms of mental health.

Overall, most studies associating greenspaces and health have been conducted in developed countries. By contrast, other studies in developing countries, such as China, have focused particularly on relationship between greenspaces and residents' mental health using just a single greenness metrics, which could have possibly resulted in biased estimations of indicators (26). In addition, in the face of growing older population, research on the association between neighborhood greenery and older adults' mental and physical well-being is relatively lacking.

This study aimed to address this gap and conducted a cross-sectional empirical research using survey data collected from 20 neighborhoods in Guangzhou City, China, a highly populated city characterized by rapid urbanization and a large proportion of immigrant populations (27), to explore the pathways that link neighborhood greenspaces and older individuals' physical and mental well-being. This study makes the following contributions to knowledge on this topic. First, it focused particularly on older adults in China and used multidimensional survey questions to assess older adults' mental and physical health status to disentangle the aging issues from neighborhood greenspace perspective. Second, both neighborhood normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) from bird's eye-view and streetscape greenery from human eye-level metrics were measured to quantify neighborhood greenery well. Third, it adopted the multigroup structural equation model in exploring the differences in pathways among older adults with different demographic backgrounds.

Literature Review

The pathway mechanism between greenspaces and health includes direct and mediating pathways that may be different among individuals with different sociodemographic backgrounds.

Numerous studies have revealed the pathway that greenspace exposure directly relates to residents' mental and physical health. In terms of physical health, green in the middle of the color spectrum is more beneficial to human health, especially to the brain and the nervous system than the other colors (28). Moreover, empirical research have shown that natural environments can effectively alleviate headaches by 52% (29). In terms of mental health, visually seeing greenery or green plants alone can help relieve tension and anxiety, and inhaling plants' essential oils can induce changes in psychological state, thereby affecting the psychological stability of the human body (30–33). Given that natural environments are less complicated than urban environments, greenery is conducive in reducing an individual's stress levels and in restoring attention (34–37). These findings have been verified by multiple empirical studies in China (21, 22) and in other developed countries, such as the Netherlands (38) and the United States (39).

In terms of mediating pathways, mediators, such as air pollution, social interactions, and physical activities, also mediate the association between neighborhood greenspaces and residents' well-being. Air pollution, such as nitrogen dioxide, fine particulate matter (such as PM2.5), and ozone, has negative health effects, and many studies have demonstrated the negative association between surrounding greenspaces and air pollution (40–42). Greenspaces can help in mitigating urban microclimates and effectively reducing urban environmental pollution and filtering health-threatening air pollutants by sticking wind-blown particulates, such as PM2.5 and PM10, to plant leaves and stems (43–45). Meanwhile, long-term exposure to air pollution such as PM2.5 is related to increased all-cause and cardiopulmonary mortality (46, 47), as well as mental disorders (48, 49). An empirical research conducted in Toronto, Canada showed that green roofs on downtown buildings contribute positively to the health of citizens via the air pollution mitigation (50). In summary, greenspaces can effectively improve air quality, and thereby ameliorating residents' health.

The second mediating pathway is via physical activities. Neighborhood greenspaces can be used as a space for physical activities, such as walking, jogging, or cycling, for residents. Greenspaces positively link to individuals' healthy behavior by encouraging them to do physical activities (51, 52). Meanwhile, physical activities benefits health and well-being of individuals from all ages (53). Furthermore, physical exercises performed in greenspaces may produce more health benefits than when done in other environments (54, 55), and limited greenspaces are positively related to sedentary lifestyle, which increases the risks of cardiovascular diseases due to obesity (56). Therefore, the greenspaces could positively link to positive health outcomes via physical exercise.

The third mediating pathway is associated with social interactions. Studies have shown that exposure to greenery may facilitate neighborhood social interactions that may foster the residents' well-being (21, 38, 57). Since greenspace may function as a place for social interactions, it may act as an intermediary variable that links the green environment to residents' health, promote social cohesion by providing a meeting place where people can engage in community activities (58, 59), and help residents obtain social support and reduce feelings of loneliness, thereby reducing stress and fatigue. Such spaces have an indirect positive relationship with mental health (60). Neighborhood greenspaces are particularly essential to aging generation because seniors are generally less mobile and have limited activity spaces and smaller social networks than the other age groups (59). In addition, harmonious social relationships, especially good neighborhood relationships, can promote residents' physical well-being (61, 62).

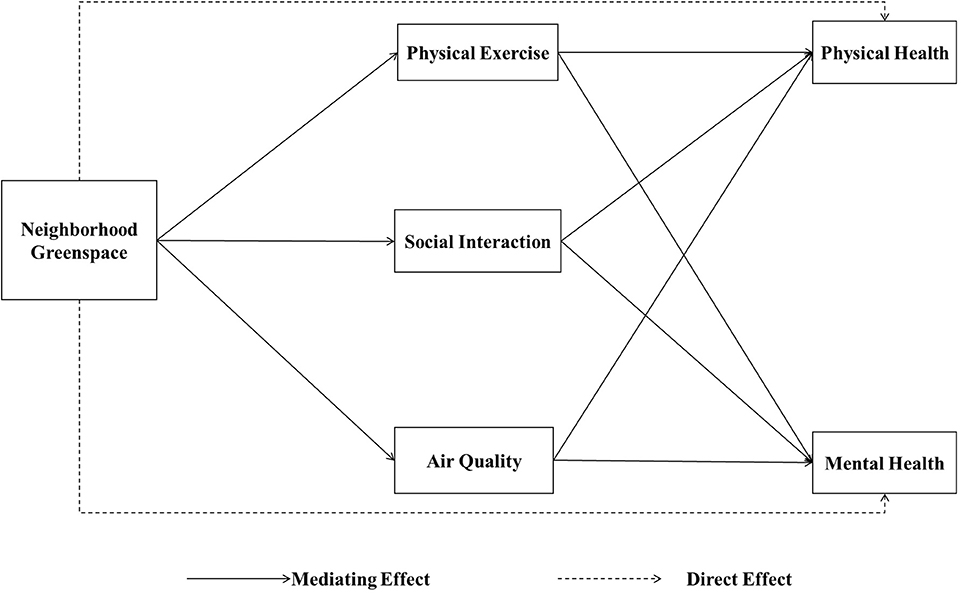

Based on this literature review, the hypothesis of this study is that neighborhood greenspaces have a direct or indirect linking path with the physical and mental health of the older adults. On the one hand, neighborhood greenspaces directly associate with older adults' physical and mental health. On the other hand, neighborhood greenspaces positively relate to older adults' physical and mental health via neighborhood air quality and older adults' physical exercise and social interaction.

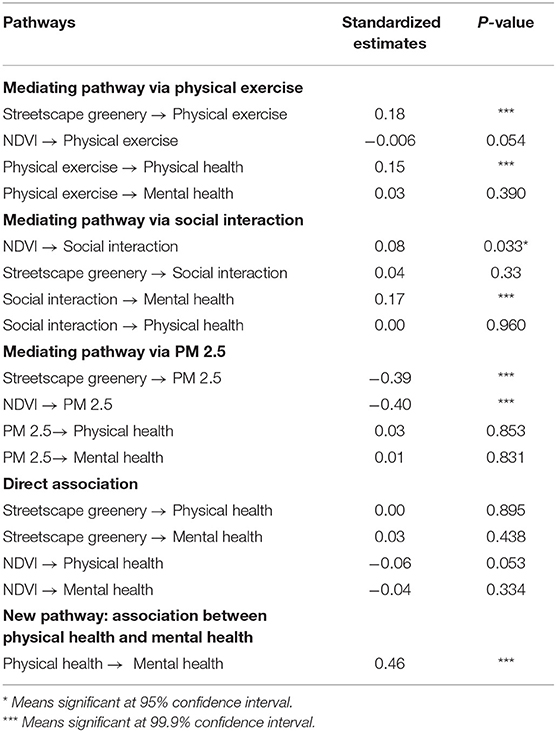

The theoretical structural equation model below was built on the basis of these hypotheses (Figure 1).

However, this association between neighborhood greenspace and health may differ among individuals with different socio-demographic characteristics, since they have various opportunities and motivations to access greenspace (60). In terms of income, studies have shown that low-income individuals are more sensitive to greenspace exposure (63), since low-income communities are more likely to have limited access to green spaces (64). As for the age, multiple researches have shown that the health status and health related behaviors of older adults are relatively more related to neighborhood greenspace than other age groups (19, 65, 66), since they tend to spend more time in the communities (67). Regarding gender, since there are gender differences in perceptions and usage of urban green spaces, the health of female individuals are more related to greenspaces than males (68). However, there are few studies focused on the association differences among individuals with different marriage and registered residence status (hukou).

Study Design

Data Source and Characteristics

Study Area and Survey Data

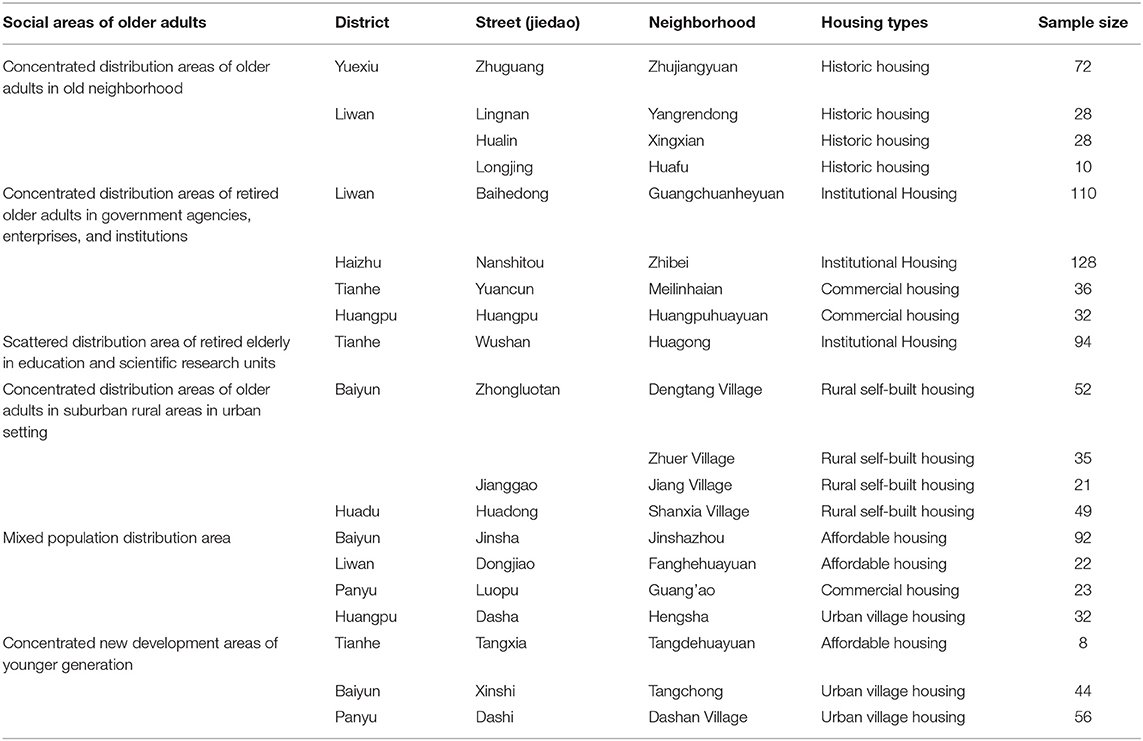

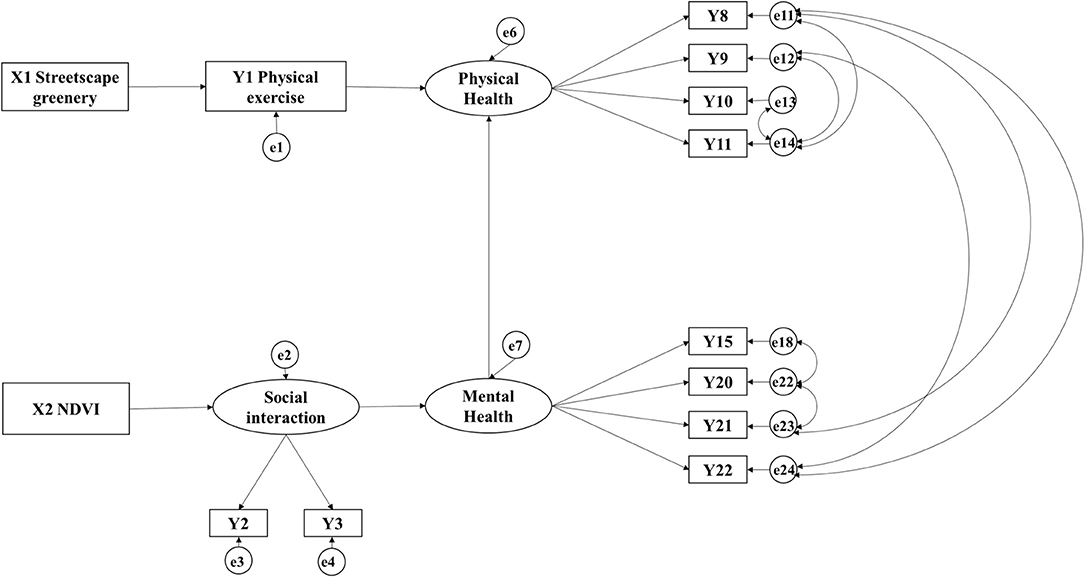

A multi-stage stratified probability proportionate to population size sampling technique (PPS) was adopted to select respondents. First, on the basis of the Sixth National Population Census data in China and previous research (69), Guangzhou was divided into six types of social areas of older adults as shown in Table 1. Subsequently, 19 streets (jiedao) from these six social areas were selected, focusing on areas with the highest score on factors of interest, and 20 case study neighborhoods were chosen with more than 10% elderly populations (aged 60 and older). The neighborhoods covered six different housing types in Guangzhou City: historic housing, institutional housing, affordable housing, rural self-built housing, commercial housing, and urban village housing (Table 1, Figure 2). Second, with the number of questionnaires in each neighborhood based on the percentage of its older adults population, a total of 972 valid questionnaire surveys of randomly selected residents who had lived in Guangzhou for over 6 months and aged 60 and older were conducted by a trained interviewer via face-to-face interview from December 2018 to April 2019. All respondents involved in this study gave their informed consent, and our study has been approved by institutional review board of school of geography and planning, Sun Yat-sen University. The questionnaire covered information on individuals' economic and social attributes, physical and mental health status, physical activity, and social interactions.

Figure 2. Locations and administrative boundaries of the 20 neighborhoods in Guangzhou City, China sampled in this study.

Greenspace Data

We acquired streetscape greenery data and NDVI to measure the amount of greenery from street and overhead views in each neighborhood, respectively. The streetscape greenery data were gathered via field surveys in these neighborhoods from March 2019 to April 2019. The data were from obtained from digital photographs taken from sampling points and calculated using the “Maoyanxiangxian” streetscape greenery calculation application. The sampling points were 20 m apart and identified along roads and alleys in and around the neighborhoods from 0, 90, 180, and 270°facing north at a normal view of a human (1.6 m) (70, 71). A total of 2,544 street view images were collected from 636 sampling points.

The satellite-based NDVI (72) of each neighborhood was calculated on the basis of 1,000 m buffer around the boundary of the administrative district of Guangzhou Community Neighborhood Committee and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager Thermal Infrared Sensor satellite remote sensing image at a 30 × 30 m spatial resolution in October 2017 with only 0.05 cloud cover using Formula 1 from Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn) (73). NDVI was calculated as follows:

Mediators

Data on mediators, including degree of air pollution in each neighborhood physical activity and social interactions, of older adults are were acquired via field surveys and questionnaires.

The level of physical activity of each older adult was determined by the average time spent on physical exercises, such as walking, per day from the questionnaire survey. The unit of measurement was hour.

Social cohesion can be defined in several ways. In this study, we focused on relatively weak social ties of community network. The level of social interaction was determined by asking each senior on what level they agree with the statements that “I know many people in the community” and “I am willing to communicate with community members.” The five categories of responses were “Strongly agree,” “Agree,” “Not decided,” “Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree” and coded into 5–1, respectively. The social interaction variable was treated as a latent variable.

We used PM2.5 concentrations obtained in each neighborhood to assess the seniors' exposure to air pollution and recorded at the same sampling points with streetscape greenery. The outcome was calculated from the average of PM2.5 concentration in each neighborhood.

Analysis Method

Multiple studies explored the pathway between greenery and residents' health by adopting multi-quantitative research methods, such as the structural equation model adopted cross-sectional study (27, 71) and the multilevel linear regression adopted in longitudinal study (5). This present cross-sectional study adopted the structural equation model in Amos 21.0 based on maximum likelihood estimates to test if the theoretical pathways (Figure 1) fit the elderly population in Chinese context and explore the pathways between neighborhood greenspaces and older adults' physical and mental health.

To evaluate the reliability of questionnaire data, we conducted reliability analysis on the same type of questionnaire data by using SPSS 21.0. Cronbach's alpha coefficients of social interaction and physical and mental health status as calculated by SPSS were 0.738, 0.912, and 0.939, respectively, indicating that similar questions in the questionnaire had high consistency, good reliability, and substantial research value. In terms of validity, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of the selected data was 0.904 (greater than 0.9) and thus passed the Bartlett sphericity test at the 99.9% confidence level, suggesting that the selected questionnaire data structure had good validity.

Results

Descriptions of the Study Population and Greenery Measures

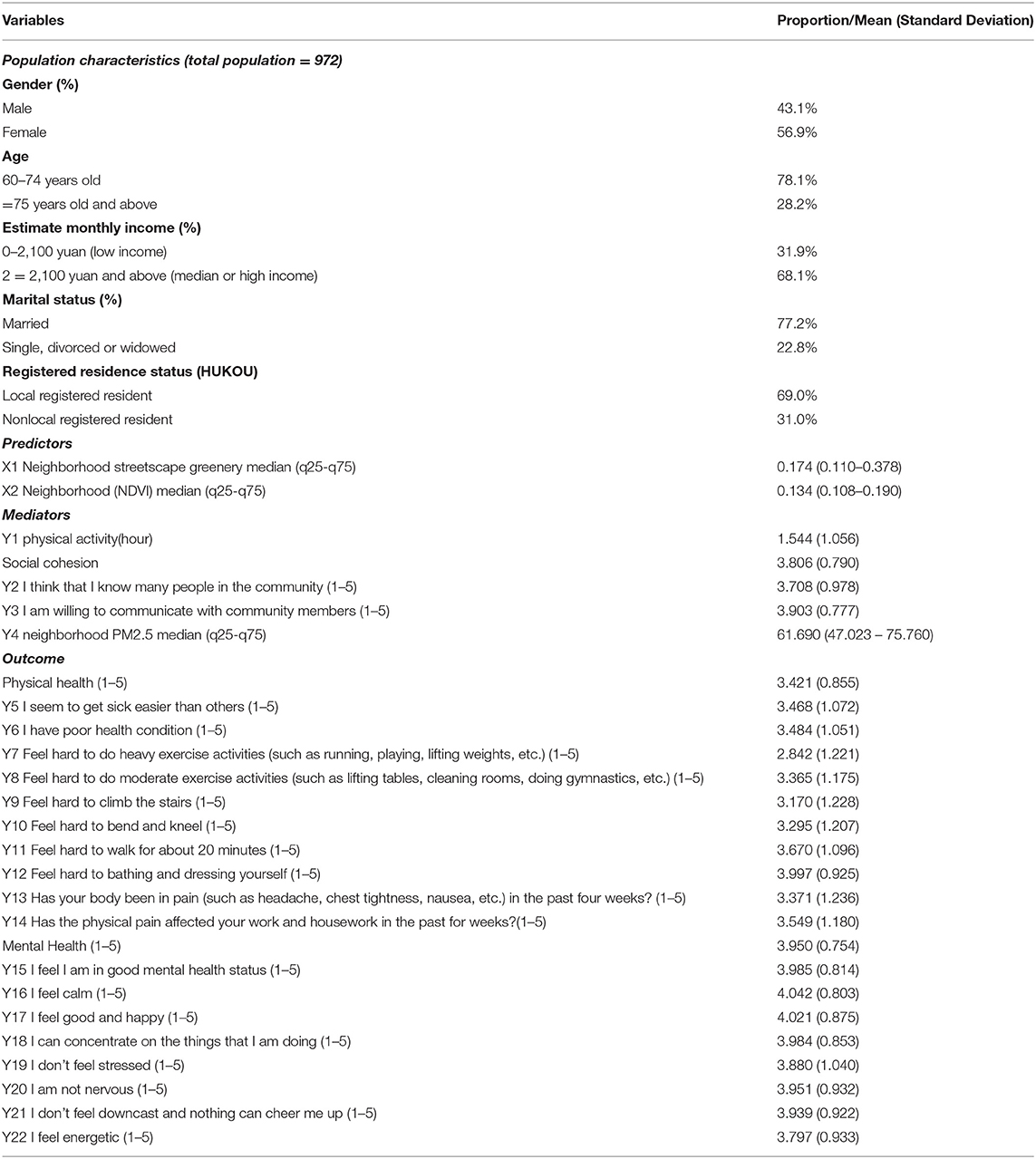

The characteristics of the neighborhoods and study populations are summarized in Table 2 without any missing value. Almost half of the respondents were male (43.1%), and 78.1% were young seniors (60–74 years old). About one third (31.9%) of the respondents with the monthly income below 2,100 yuan (according to the minimum wage standard in Guangzhou) belong to low-income group; 77.2% were married, and 69.0% had consistent registered residence status (hukou) with their living address, which means they are local residents.

The median scores for neighborhood streetscape greenery and NDVI were 0.174 and 0.134, respectively. No statistical correlation was observed between these variables (r = 0.035, p = 0.4314), which justifies using them as two separate observable indicators in the structural equation model (Figure 3). The standard deviation (SD) and 25–75 quantile represent variation and the dispersion degree of the data. In terms of mediators, the average time spent on physical exercise of all respondents are about one and half hours, with a standard deviation of 1.056 h, indicating a relatively large variance. The average social interaction score and the median neighborhood PM2.5 concentration were 3.806 (SD = 0.790) and 61.690 μg/m3 respectively, which is higher than WHO air quality guideline for PM2.5 24-h concentrations (25 μg/m3) (74). With regard to health outcomes, the average scores of physical and mental health were 3.421 (SD: 0.855) and 3.950 (SD: 0.754), respectively, indicating relatively good overall health status among the respondents.

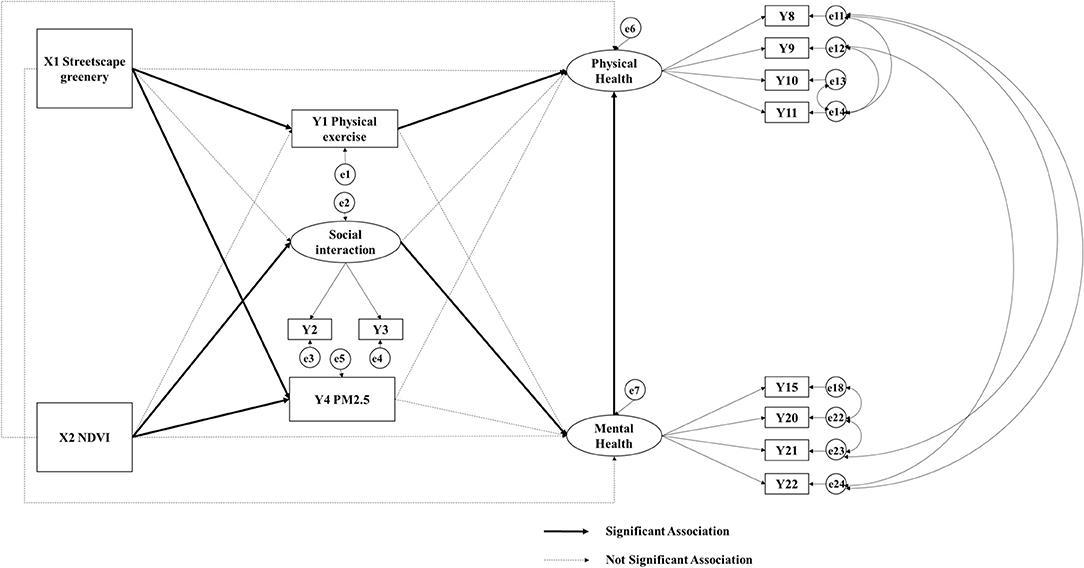

Model Modifications and Fit

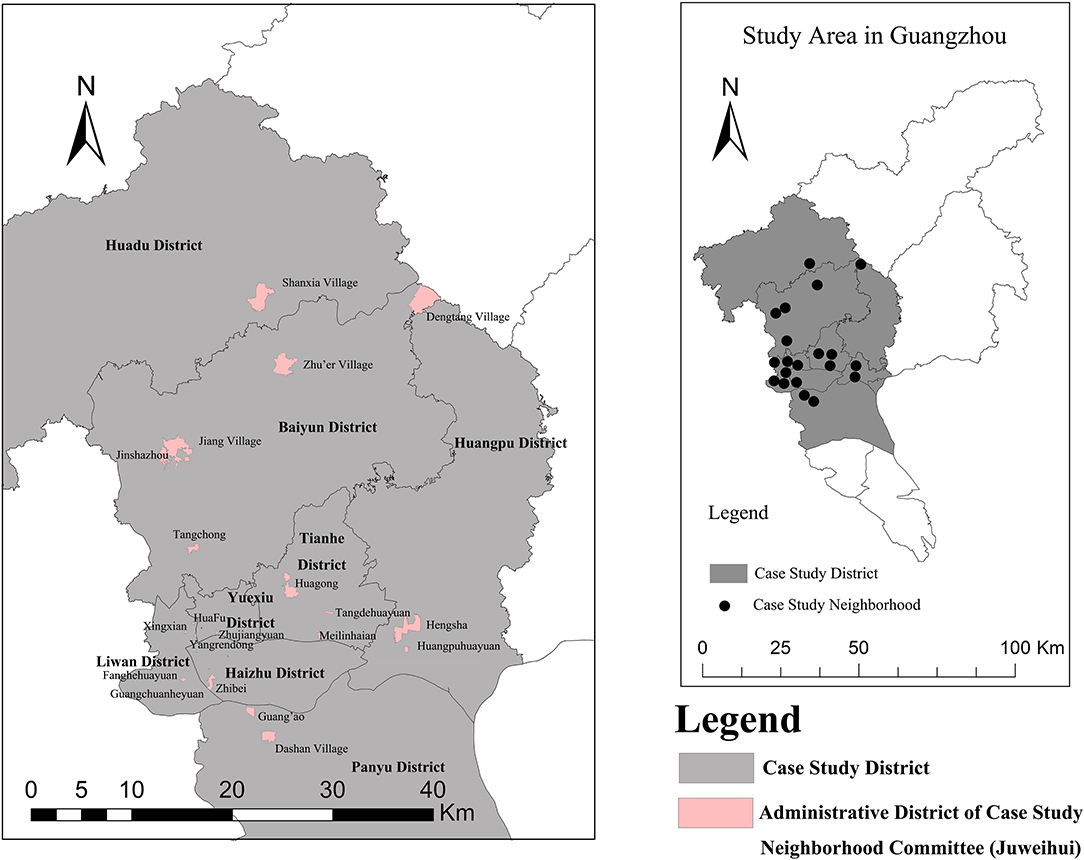

The RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) value of the initial theoretical structural equation model was exceptionally high. On the basis of the revised index MI and t values suggested by the Amos software, modifications of the model were made separately and once a time. The model was analyzed to determine whether the corrections were reasonable by comparing the model fitness index and the Chi-square value before and after the corrections and by ensuring that the model had practical theoretical importance. The modifications involved increasing notable impact paths, such as the impact path between mental and physical health, and deleting observation variables and their paths that do not make a meaningful contribution and remained the loads of the observed variable loading factors of mental and physical health were higher than 0.71. After modifications, the SEM showed a sufficiently good fit to the data: GFI (Goodness-of-fit index) = 0.978 (>0.9) and RMSEA = 0.039 (<0.05). The results and modification are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Model Results

In terms of direct relationships, neighborhood NDVI was not statistically significantly associated with older adults' neither the physical nor mental health at the 95% confidence level. With regard to mediating associations, neighborhood streetscape greenery was positively related to older adults' average time spent on physical activity but negatively related to neighborhood PM2.5 concentrations at the 99.9% confidence interval. Neighborhood NDVI was positively related to older adults' social interaction at the 95% confidence interval but negatively related to neighborhood PM2.5 concentrations at the 99.9% confidence interval. Older adults' physical activity and level of social interaction were positively associated with their physical and mental health, respectively, at the 99.9% confidence level. Moreover, older adults' mental health was positively related to their physical health at the 99.9% confidence level.

The significant positive association pathways which are consistent with hypothesis includes “streetscape greenery—physical exercise—physical health,” “neighborhood NDVI—social interaction—mental health,” and the positive association between mental and physical health is newly found. The next step is to analyze the difference of these association pathways among elderly individuals with various socio-demographic characteristics.

Multigroup Analysis

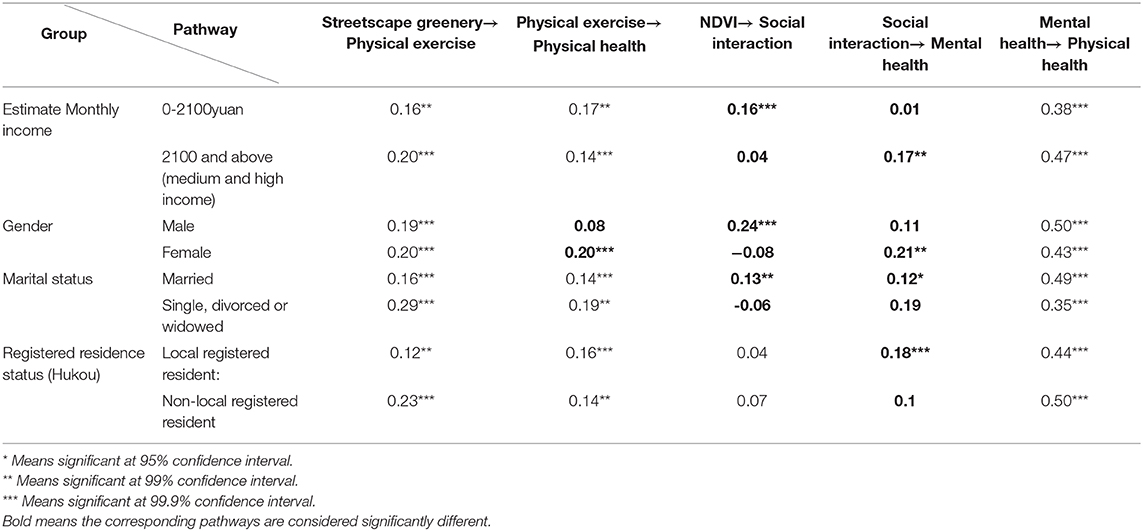

On the basis of the SEM developed above, which is applicable to the entire older adults' group, the less significant (p > 0.05) pathways were deleted with only meaningful pathways remained (Figure 4). Control variables of different incomes, gender, marital status and registered residence status (hukou) were grouped as the same criteria (Table 4) to perform multigroup SEM analysis (Multi-Group Analysis) and further explore differences in the pathways between two corresponding groups.

Table 4. Standardized estimates and the significance level of unconstrained model of multigroup analyses.

Four models, namely, unconstrained model, measurement weights restricted model, structural weights restricted model, and measurement residuals restricted model, were calculated and fitted well (GFI > 0.9, RMESA < 0.05). A significant difference (p < 0.05) in Chi-square value between the unrestricted and measurement residuals restricted models denotes differences between two corresponding groups. The Chi-square value of the unrestricted and restricted models significantly increased (p < 0.05) regarding income, gender, marital status, and registered residence status (hukou), indicating that these variables had a significant regulating effect.

In comparing the pathways between two corresponding groups of significant difference, critical ratios for differences between parameters are used for comparison when both paths are significant. When the critical ratio for difference between parameters was <1.96 (at the 95% confidence interval and higher), the two corresponding pathways were considered equal and vice versa. If one pathway is significant (p < 0.05) while the corresponding one is not (p ≥ 0.05), these pathways are considered different. If two corresponding pathways are considered different in either way mentioned above, they are marked in bold in Table 4. In terms of income, the results showed that the level of social interactions of individuals belonging to low-income groups was more strongly associated with neighborhood NDVI, but it had no association with their mental health status. In terms of gender, the physical and mental health of female older adults were more significantly related to average time spent on physical exercise and level of social interaction than that of male elderly. With regard to marital status, the level of social interaction of married older adults showed a significant relationship with neighborhood greenery (at the 99% confidence interval) and significant linkage to mental health (at the 95% confidence interval). By contrast, the social interaction level in unmarried older adults' group showed neither significant association with neighborhood greenery indicators nor exhibited significant association with their mental health. With regard to registered residence status (hukou), the level of social interaction of local groups showed no significant relationship with neighborhood greenery metrics but exhibited significant association with their mental health. Among non-local groups, the level of social interaction was neither significantly positively linked to neighborhood streetscape greenery nor to their mental health.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies, the present study confirmed that the mediating pathways where neighborhood greenspaces have a positive relationship physical and mental health via physical exercise and social interactions, respectively (55, 60, 75). By adopting the research methods including establishing a theoretical SEM on the basis of the results of previous studies and modifying it accordingly to achieve good model fit. We used the modified model to explore and analyze the internal logical relationships and pathways between greenspaces and the physical and mental health of the older adults in 20 residential neighborhoods in China. We conducted a multigroup analysis to explore whether and how the relationships between neighborhood greenspaces and the well-being of the older adults was different among five control groups. The results of the present study extend the knowledge on this topic in the following aspects. First, this study was the first to systematically investigate the pathways that link neighborhood greenspaces and the physical and mental health of the older adults in a densely populated Chinese city. Second, this study investigated differences in pathways among various control groups of older adults. Third, the study made a methodological contribution by adopting both bird's-eye view NDVI and human-scale streetscape greenery to measure neighborhood greenness.

The Association Between Neighborhood Greenspace and Older Adults' Well-Being

Neighborhood greenspaces are positively related to older adults' physical health via physical activity. Existing research generally agrees that neighborhood greenspaces encourage residents to engage in physical activities (such as walk, run, bike, and other sports) and provide more opportunities for people to exercise, thereby increasing the average time they spend on physical activities (60). Numerous studies conducted in developed countries support the positive association between greenspaces and physical activity among adults (76–78) and children (75). For example, a study in the UK suggested the urban greenspaces are valuable resources to encourage physical activity among children (75). A study in Europe found that large expanses of greenery in residential environments promote more physical activities among adults (77). The present study expands these conclusions to the order residents possibly because they no longer work and spend more time in their neighborhoods. Hence, the association between neighborhood greenspaces with their level of physical activity is more prominent. Older adults who are willing to do physical exercises often participate in morning exercises, group dancing, and other sports in open neighborhood greenspaces, but those who do not participate in such activities still walk around the neighborhood. Trees beside neighborhood lanes provide shade and make their walk enjoyable, thereby promoting physical exercise. Some suburban seniors still work as farmers, which is also a form of physical exercise. Previous studies also suggested that high levels of physical exercise are associated with good physical and mental health (79, 80). The present study proved this theory in terms of physical health: the longer the older adults exercise frequently has better physical health than those who are mostly sedentary. Studies have shown that physical activities among older adults can preserve muscle mass and reduce age-related decrease in metabolic rate (81), which can potentially result in reducing morbidity and mortality and postponing disability (82). However, the present study found no statistically significant relationships between the elderly's physical activity and their mental health. A possible explanation is that different intensities of physical activity may have a different relationship with older adults' mental health, and intense activity may lead to mood variation and mental deterioration which are more related to the construct of depression (83). However, this study did not consider of the intensity of activity.

Neighborhood greenspaces are positively associated with older adults' mental health via social interactions. Multiple empirical studies in both developed and developing countries have demonstrated that neighborhood greenspaces, as a meeting place for social interactions, have a positive relation to social cohesion (58, 59). Some of these studies were conducted in the Netherlands that covered all age groups above 12 years old (57) and aging populations aged 60 years and older (59). A similar study was conducted in Australia that focused on age groups between 20 and 65 years old (84). Another study was performed in China that concentrated on adults (21). Other works also found a positive relationship between social cohesion and mental health (85) and physical health (62). The present study reaffirmed this pathway to mental health in the context of the older adults in China. In Guangzhou City, most seniors walk together to chat or drink tea almost every day, and the street greenery makes their walks more comfortable, especially during the summer. They meet with friends to acquaint each other in greenspaces where the conditions are cooler. These are places where they play cards and chess. Old tall trees serve as their shade from the sun. The old adults from suburban areas flock in greenspaces to share their experiences at work. Social interactions can positively affect the older adults' perception of their aging status and their own sense of value in their neighborhoods, thereby promoting their mental health (86). Moreover, social interactions can alleviate the older adults' emotional problems through continuous and meaningful interactions with social members. These interactions increase their feelings of positive emotions and thus positively associates with their mental health (87). However, the present study did not find significant linkages between social contacts and physical health among older adults. A possible explanation behind this result is that the definition of social contacts in this study was slightly different from the concept of social cohesion in terms of strength of social ties (88). In addition, social interaction may have detrimental effects, since more interaction may result in more confliction than the counterparts (89).

The hypothesis that neighborhood greenspaces are positively associated with the older adults' physical and mental health by reducing air pollution was not supported because the results showed that neighborhood greenspaces were negatively related to neighborhood PM2.5 concentrations, but this parameter exhibited no significant linkage to older adults' physical and mental health. This result contradicted that of several theoretical (10, 90) and empirical studies (71, 91). Especially for older adults, existing studies suggest that PM2.5 concentration is significantly related to their respiratory system (92) and elderly is a susceptible population to PM2.5 associated diseases (93–95) and PM2.5 related depressive and anxiety symptoms (96). A possible reason for this contradiction is that the association between health and air pollution could only be demonstrated after a relatively long-term exposure (97–99), and certain diseases, including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease such as asthma, and cancer (92, 100, 101), which takes a while to manifest, while this study is cross-sectional. Moreover, both the mental and physical health status acquired in this study was self-rated. Another possible explanation is that PM2.5 concentrations are varying over time. The data obtained in this study only reflected the status of air quality during measurement; thus, the short period of air quality measurement led to bias in data collection.

The present study did not observe strong and significant direct association between neighborhood greenspaces and older adults' well-being. This result contradicted that of previous studies (21). According to the literature, neighborhood greenery is positively related to an individual's physical (102, 103) and mental health (21). A possible reason behind this inconsistency is that the association between short-term effects of exposure to greenspaces and long-term physical and mental health of older adults is not significant. Most existing studies focused on the association between greenspaces and a specific health aspect instead of overall health status. For example, a study that examined short-term changes in vascular risk factors found a positive relationship between urban green environments and health (102). This cross-sectional study had a smaller scope and encompassed a shorter time period. Another possible explanation is that not all plants can have beneficial effects on residents' health, and some plants that are toxic, attract insects, or easily become allergens actually have negative effects on their residents (104).

An unexpected result was obtained by the present study: the mental health of older adults was positively associated with their physical health. An empirical study in Australia showed that positive attitudes to aging are associated with positive self-reported physical health status (105). Older adults with strong mental health status and positive self-recognition are more likely to have excellent physical health.

The Association Pathway Among Older Adults With Different Sociodemographic Characteristics

We performed a multigroup analysis to explore the differences among older adults with different sociodemographic characteristics. Overall, the “neighborhood greenspace—physical exercise—physical health” pathway is significant in all older adults' group except male group. While the “neighborhood greenspace—social interaction—mental health” pathway is dramatically different among the corresponding groups. The level of social interaction of individuals belonging to low-income group was more significantly associated with neighborhood greenspaces probably because of limited expendable funds they have to pay for social activities outside their neighborhoods and unfamiliarity to their external environment, indicating that they are more dependent on freely accessible neighborhood greenspaces. However, the social interaction parameter was not significantly associated with their mental health status probably results from social exclusion due to their disadvantaged social status. As for female older adults, their mental and physical health are more significantly associated with social interaction physical exercise, respectively, than those of male elderly. While the social interaction level of the male group is more significantly linked to the neighborhood NDVI than the female group, probably because most male older adults communicate with friends within the neighborhood greenspace than female. With regard to unmarried elderly, the association of neighborhood green spaces on their level of social interaction was not significant because their interactions with close friends is not necessarily limited to neighborhood greenspaces and they tend to have more freedom to go outside the neighborhood. In terms of registered residency status, the level of social interaction of the non-local groups was neither significantly related to neighborhood greenery nor to their mental health. A possible explanation is that the social network of these non-local older adults remains in their former residence, and the neighborhood network here seems foreign to them. In general, older adults, especially those who belong to low-income group, have limited spaces for activities and socializing that is why they are more dependent on neighborhood greenspaces, a supposition consistent with that of previous studies (106, 107).

Strengths and Limitations

The present study was one of the first to examine the association pathways between neighborhood greenspaces and older adults' physical and mental health in a Chinese city. This study has two main strengths. First, we adopted two metrics of neighborhood greenery, namely, bird's-eye view and human view, to minimize statistical bias. Second, we concentrated on older adults with different sociodemographic characteristics to identify differences among groups and focus on vulnerable groups.

This study has several limitations that must be addressed in a future work. First, it is a study based on cross-sectional data and research design, which may overestimate the association make it difficult to infer causation between neighborhood greenspace and older adults' well-being. Second, streetscape and PM2.5 data were collected via field surveys and with relatively limited sample sizes. Hence, the data may lack accuracy. Other data acquisition methods, such as calculating the average annual air pollution concentration from secondary data sources (71), extracting street view images from maps (27, 70) and focusing on the respiratory morbidity of older adults, may improve the accuracy and find meaningful result. Third, the health outcomes were determined from subjective questionnaire surveys. Objective health outcomes, such as BMI and morbidity, may be more reliable. Moreover, the greenspace accessibility analysis as well as the association pathways analysis among communities with different housing nature could be also taken into consideration in the future research with larger sample size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

On the basis of review of literature on greenspaces and residents' well-being, we constructed an SEM linking neighborhood greenspaces and older adults' physical and mental health status. We obtained primary data from 972 urban and rural elderly populations and streetscape greenery and PM2.5 concentration data from field surveys of 20 residential neighborhoods in Guangzhou City from 2018 to 2019. We also gathered secondary data from neighborhood committee level NDVI data from 2017 Landsat image. We found that neighborhood greenspaces have a positive relationship with older adults' physical exercise, thereby positively associates with their physical health. Moreover, greenspaces have a positive linkage with older adults' social interaction. Thus, greenspaces are positively associated with their mental health. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies. However, we found that neighborhood greenspaces have no significant direct association with older adults' physical and mental health. Furthermore, we found that the level of social interaction is more significantly related to neighborhood greenspaces among low-income groups, and mental health is more significantly linked to the level of social interaction among local and unmarried groups. Based on the findings, we suggest that urban planners should design neighborhood greenspaces where the older adults can exercise and communicate with each other. They can also plant trees along sidewalks to provide desirable walking environment for seniors, and recreational infrastructures under shaded trees to increase community interactions among the older adults. Finally, they can develop greenspaces in communities with a high proportion of vulnerable elderly, especially for those that belong to low-income groups.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of institutional copyright issues. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Yuan Yuan, yuanyuan@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Geography and Planning, Sun Yat-sen University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YY contributed to the conception and design of the study and is in charge of the project. YZ, YC, and SL contributed to data preparation, collection, and organization. YZ performed the statistical analysis, structured, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YY, YZ, and YC contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51678577 and 41871161), by the Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (201804010241), by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Urbanization and Geo-simulation and by the Guangdong Provincial Technical Innovation Program for the Top Young Talents.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. WHO. Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. Available online at: https://www.who.int/ageing/projects/age-friendly-cities-communities/en/ (accessed April 10, 2020).

2. Population ages 65 and above, total | Data. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO (accessed April 11, 2020).

3. Urban population (% of total population) - World | Data. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=1W (accessed April 11, 2020).

4. Gascon M, Mas MT, Martínez D, Dadvand P, Forns J, Plasència A, et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:4354–79. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404354

5. Astell-Burt T, Mitchell R, Hartig T. The association between green space and mental health varies across the lifecourse. a longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2014) 68:578–83. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203767

6. Cohen-Cline H, Turkheimer E, Duncan GE. Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: a twin study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2015) 69:523–9. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204667

7. Triguero-Mas M, Donaire-Gonzalez D, Seto E, Valentín A, Martínez D, Smith G, et al. Natural outdoor environments and mental health: stress as a possible mechanism. Environ Res. (2017) 159:629–38. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.08.048

8. Grahn P, Stigsdotter UA. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For Urban Green. (2003) 2:1–18. doi: 10.1078/1618-8667-00019

9. Haaland C, van den Bosch CK. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban For Urban Green. (2015) 14:760–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009

10. Hartig T, Mitchell R, de Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and Health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2014) 35:207–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

11. Kaczynski AT, Henderson KA. Environmental correlates of physical activity: a review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leis Sci. (2007) 29:315–54. doi: 10.1080/01490400701394865

12. Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Greenspace and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. (2011) 12:e183–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00827.x

13. Lee ACK, Maheswaran R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J Public Health (Bangkok). (2011) 33:212–22. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq068

14. Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, Chudnovsky A, Hystad P, Dzhambov AM, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. (2017) 158:301–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028

15. Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res. (2018) 166:628–37. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.030

16. van den Berg AE, Maas J, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 70:1203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002

17. Wells NM, Evans GW. Nearby nature: a buffer of life stress among rural children. Environ Behav. (2003) 35:311–30. doi: 10.1177/0013916503035003001

18. Maas J, Verheij RA, De Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P, Schellevis FG, Groenewegen PP. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2009) 63:967–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079038

19. de Vries S, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Natural environments—healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ Plan A. (2003) 35:1717–31. doi: 10.1068/a35111

20. van Dillen SME, de Vries S, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Greenspace in urban neighbourhoods and residents' health: adding quality to quantity. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2012) 66:e8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.104695

21. Liu Y, Wang R, Grekousis G, Liu Y, Yuan Y, Li Z. Neighbourhood greenness and mental wellbeing in Guangzhou, China: What are the pathways? Landsc Urban Plan. (2019) 190:103602. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103602

22. Wang R, Helbich M, Yao Y, Zhang J, Liu P, Yuan Y, et al. Urban greenery and mental wellbeing in adults: cross-sectional mediation analyses on multiple pathways across different greenery measures. Environ Res. (2019) 176:108535. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108535

23. Dong H, Qin B. Exploring the link between neighborhood environment and mental wellbeing: a case study in Beijing, China. Landsc Urban Plan. (2017) 164:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.04.005

24. Feng J, Tang S, Chuai X. The impact of neighbourhood environments on quality of life of elderly people: evidence from Nanjing, China. Urban Stud. (2018) 55:2020–39. doi: 10.1177/0042098017702827

25. Zhang L, Kwan MP, Chen F, Lin R, Zhou S. Impacts of individual daily greenspace exposure on health based on individual activity space and structural equation modeling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2323. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102323

26. Yang L, Xian G, Klaver JM, Deal B. Urban land-cover change detection through sub-pixel imperviousness mapping using remotely sensed data. Photogramm Eng Remote Sensing. (2003) 69:1003–10. doi: 10.14358/PERS.69.9.1003

27. Liu Y, Wang R, Lu Y, Li Z, Chen H, Cao M, et al. Natural outdoor environment, neighbourhood social cohesion and mental health: using multilevel structural equation modelling, streetscape and remote-sensing metrics. Urban For Urban Green. (2020) 48:126576. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126576

28. Fang C, Wang C, Guo E, Qie G. Relationship between urban green space and health of urban residents. Journal of Northeast Forestry University. (2010) 38:114–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-5382.2010.04.034

29. Hansmann R, Hug SM, Seeland K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and parks. Urban For Urban Green. (2007) 6:213–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2007.08.004

30. Bringslimark T, Hartig T, Patil GG. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: a critical review of the experimental literature. J Environ Psychol. (2009) 29:422–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.05.001

31. Sugawara Y, Hara C, Tamura K, Fujii T, Nakamura KI, Masujima T, et al. Sedative effect on humans of inhalation of essential oil of linalool: sensory evaluation and physiological measurements using optically active linalools. Anal Chim Acta. (1998) 365:293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(97)00639-9

32. Hongratanaworakit T, Buchbauer C. Evaluation of the harmonizing effect of ylang-ylang oil on humans after inhalation. Planta Med. (2004) 70:632–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827186

33. Angioy AM, Desogus A, Barbarossa IT, Anderson P, Hansson BS. Extreme sensitivity in an olfactory system. Chem Senses. (2003) 28:279–84. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.4.279

34. Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD, Fiorito E, Miles MA, Zelson M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol. (1991) 11:201–30. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

35. Ulrich RS. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. Behav Nat Environ. (1983) 6:85–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4

36. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. (1995) 15:169–82. doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

37. Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York, NY: CUP Archive (1989).

38. De Vries S, van Dillen SME, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 94:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030

39. Kuo FE. Coping with poverty. Impacts of environment and attention in the inner city. Environ Behav. (2001) 33:5–34. doi: 10.1177/00139160121972846

40. Su JG, Jerrett M, de Nazelle A, Wolch J. Does exposure to air pollution in urban parks have socioeconomic, racial or ethnic gradients? Environ Res. (2011) 111:319–28. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.002

41. Wang R, Xue D, Liu Y, Liu P, Chen H. The relationship between air pollution and depression in China: is neighbourhood social capital protective? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1160. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061160

42. Wang R, Liu Y, Xue D, Yao Y, Liu P, Helbich M. Cross-sectional associations between long-term exposure to particulate matter and depression in China: the mediating effects of sunlight, physical activity, and neighborly reciprocity. J Affect Disord. (2019) 249:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.007

43. Makhelouf A. The effect of green spaces on urban climate and pollution. Iran J Environ Heal Sci Eng. (2009) 6:35–40. Available online at: https://ijehse.tums.ac.ir/index.php/jehse/rt/metadata/190/0

44. Klingberg J, Broberg M, Strandberg B, Thorsson P, Pleijel H. Influence of urban vegetation on air pollution and noise exposure – A case study in gothenburg, Sweden. Sci Total Environ. (2017) 599–600:1728–39. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.051

45. Hosker RP, Lindberg SE. Review: atmospheric deposition and plant assimilation of gases and particles. Atmos Environ. (1982) 16:889–910. doi: 10.1016/0004-6981(82)90175-5

46. Kan H, Gu D. Association between long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and mortality in China: a cohort study. Epidemiology. (2011) 22:S29. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000391747.54172.4b

47. Hoek G, Krishnan RM, Beelen R, Peters A, Ostro B, Brunekreef B, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio-respiratory mortality: a review. Environ Health. (2013) 12:43. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-43

48. Power MC, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Hart JE, Okereke OI, Laden F, Weisskopf MG. The relation between past exposure to fine particulate air pollution and prevalent anxiety: observational cohort study. BMJ. (2015) 350:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1111

49. Wu Z, Chen X, Li G, Tian L, Wang Z, Xiong X, et al. Attributable risk and economic cost of hospital admissions for mental disorders due to PM2.5 in Beijing. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 718:137274. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137274

50. Currie BA, Bass B. Estimates of air pollution mitigation with green plants and green roofs using the UFORE model. Urban Ecosyst. (2008) 11:409–22. doi: 10.1007/s11252-008-0054-y

51. Hadavi S. Direct and indirect effects of the physical aspects of the environment on mental well-being. Environ Behav. (2017) 49:1071–104. doi: 10.1177/0013916516679876

52. van den Berg MM, van Poppel M, van Kamp I, Ruijsbroek A, Triguero-Mas M, Gidlow C, et al. Do physical activity, social cohesion, and loneliness mediate the association between time spent visiting green space and mental health? Environ Behav. (2019) 51:144–66. doi: 10.1177/0013916517738563

53. Manley AF. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Diane Publishing (1996).

54. Mitchell R. Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc Sci Med. (2013) 91:130–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.012

55. Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol. (2011) 45:1761–72. doi: 10.1021/es102947t

56. Storgaard RL, Hansen HS, Aadahl M, Glümer C. Association between neighbourhood green space and sedentary leisure time in a danish population. Scand J Public Health. (2013) 41:846–52. doi: 10.1177/1403494813499459

57. Maas J, van Dillen SME, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Heal Place. (2009) 15:586–95. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.006

58. Holtan MT, Dieterlen SL, Sullivan WC. Social life under cover: tree canopy and social capital in baltimore, Maryland. Environ Behav. (2015) 47:502–25. doi: 10.1177/0013916513518064

59. Kemperman A, Timmermans H. Green spaces in the direct living environment and social contacts of the aging population. Landsc Urban Plan. (2014) 129:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.05.003

60. Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Towards A better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: development of a theoretical framework. Landsc Urban Plan. (2013) 118:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.10.012

61. Nieminen T, Martelin T, Koskinen S, Aro H, Alanen E, Hyyppä MT. Social capital as a determinant of self-rated health and psychological well-being. Int J Public Health. (2010) 55:531–42. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0138-3

62. Rios R, Aiken LS, Zautra AJ. Neighborhood contexts and the mediating role of neighborhood social cohesion on health and psychological distress among hispanic and non-hispanic residents. Ann Behav Med. (2012) 43:50–61. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9306-9

63. Mitchell R, Popham F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. Lancet. (2008) 372:1655–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61689-X

64. Taylor WC, Floyd MF, Whitt-Glover MC, Brooks J. Environmental justice: a framework for collaboration between the public health and parks and recreation fields to study disparities in physical activity. J Phys Act Health. (2007) 4 (Suppl. 1):S50–S63. doi: 10.1123/jpah.4.s1.s50

65. Takano T, Nakamura K, Watanabe M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens' longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2002) 56:913–18. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.913

66. Kweon B-S, Sullivan WC, Wiley AR. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environ Behav. (1998) 30:832–58. doi: 10.1177/001391659803000605

67. Kaczynski AT, Potwarka LR, Smale BJA, Havitz MF. Association of parkland proximity with neighborhood and park-based physical activity: variations by gender and age. Leis Sci. (2009) 31:174–91. doi: 10.1080/01490400802686045

68. Richardson EA, Mitchell R. Gender differences in relationships between urban green space and health in the United Kingdom. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:568–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.015

69. Zhou C, Tong X, Wang J, Lai S. Spatial differentiation and the formation mechanism of population aging in guangzhou in 2000 - 2010. Geogr Res. (2018) 37:103–18. doi: 10.11821/dlyj201801008

70. Helbich M, Yao Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Liu P, Wang R. Using deep learning to examine street view green and blue spaces and their associations with geriatric depression in Beijing, China. Environ Int. (2019) 126:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.013

71. Wang R, Yang B, Yao Y, Bloom MS, Feng Z, Yuan Y, et al. Residential greenness, air pollution and psychological well-being among urban residents in Guangzhou, China. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 711:134843. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134843

72. Tucker CJ. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens Environ. (1979) 8:127–50. doi: 10.1016/0034-4257(79)90013-0

73. Geospatial Data Cloud. Available online at: http://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed April 11, 2020).

74. WHO. Air Quality Guidelines for Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide. Geneva: WHO Press (2006).

75. Lachowycz K, Jones AP, Page AS, Wheeler BW, Cooper AR. What can global positioning systems tell us about the contribution of different types of urban greenspace to children's physical activity? Heal Place. (2012) 18:586–94. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.01.006

76. Coombes E, Jones AP, Hillsdon M. The relationship of physical activity and overweight to objectively measured green space accessibility and use. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 70:816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.020

77. Ellaway A, Macintyre S, Bonnefoy X. Graffiti, greenery, and obesity in adults: secondary analysis of European cross sectional survey. Br Med J. (2005) 331:611–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38575.664549.F7

78. Mytton OT, Townsend N, Rutter H, Foster C. Green space and physical activity: an observational study using health survey for England data. Heal Place. (2012) 18:1034–41. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.003

79. Pate RR, Macera CA, Pratt M, Heath GW, Blair SN, Bouchard C, et al. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American college of sports medicine. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. (1995) 273:402–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290054029

80. Pretty J, Peacock J, Hine R, Sellens M, South N, Griffin M. Green exercise in the UK countryside: effects on health and psychological well-being, and implications for policy and planning. J Environ Plan Manag. (2007) 50:211–31. doi: 10.1080/09640560601156466

81. Evans WJ. Effects of aging and exercise on nutrition needs of the elderly. Nutr Rev. (2009) 54:S35–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03785.x

82. Christmas C, Andersen RA. Exercise and older patients: guidelines for the clinician. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2000) 48:318–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02654.x

83. Peluso MAM, Guerra de Andrade LHS. Physical activity and mental health: the association between exercise and mood. Clinics (São Paulo). (2005) 60:61–70. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322005000100012

84. Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, Owen N. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2008) 62:6–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064287

85. Echeverría S, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Borrell LN, Jackson S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Heal Place. (2008) 14:853–65. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.004

86. Wang J, Yang X. The influence of social interaction on the mental health of the elderly : the mediation effect of aging attitude : Relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms among resident physicians : mediating effect of resilience. In: 21st National Psychological Academic Conference, (Beijing) 1369–70.

87. Gu R, Song H, Li J. Investigation and correlation analysis of social support and mental health in community-dwelling elderly people. Chinese Gen Pract. (2019) 22:570–4. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462010005000028

88. Kazmierczak A. The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landsc Urban Plan. (2013) 109:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.007

89. Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. (2004) 59:676–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

90. Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Khreis H, Triguero-Mas M, Gascon M, Dadvand P. Fifty shades of green. Epidemiology. (2017) 28:63–71. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000549

91. Yang BY, Markevych I, Heinrich J, Bloom MS, Qian Z, Geiger SD, et al. Residential greenness and blood lipids in urban-dwelling adults: the 33 communities Chinese health study. Environ Pollut. (2019) 250:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.128

92. Xing YF, Xu YH, Shi MH, Lian YX. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J Thorac Dis. (2016) 8:E69–E74. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.19

93. Wang C, Tu Y, Yu Z, Lu R. PM2.5 and cardiovascular diseases in the elderly: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:8187–97. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120708187

94. Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. (2010) 121:2331–78. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1

95. Sacks JD, Stanek LW, Luben TJ, Johns DO, Buckley BJ, Brown JS, et al. Particulate matter-induced health effects: who is susceptible? Environ Health Perspect. (2011) 119:446–54. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002255

96. Pun VC, Manjourides J, Suh H. Association of ambient air pollution with depressive and anxiety symptoms in older adults: results from the NSHAP study. Environ Health Perspect. (2017) 125:342–8. doi: 10.1289/EHP494

97. Pope CA III, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Thurston GD. Lung cancer,cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. J Am Med Assoc. (2002) 287:1132–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132

98. Miller KA, Siscovick DS, Sheppard L, Shepherd K, Sullivan JH, Anderson GL, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. (2007) 356:447–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054409

99. Ostro B, Lipsett M, Reynolds P, Goldberg D, Hertz A, Garcia C, et al. Long-term exposure to constituents of fine particulate air pollution and mortality: results from the California Teachers Study. Environ Health Perspect. (2010) 118:363–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901181

100. Andersen ZJ, Bønnelykke K, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, Ketzel M, Loft S, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and asthma hospitalisations in older adults: a cohort study. Thorax. (2012) 67:6–11. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200711

101. Pun VC, Kazemiparkouhi F, Manjourides J, Suh HH. Long-term PM2.5 exposure and respiratory, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in older US adults. Am J Epidemiol. (2017) 186:961–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx166

102. Lanki T, Siponen T, Ojala A, Korpela K, Pennanen A, Tiittanen P, et al. Acute effects of visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: a field experiment. Environ Res. (2017) 159:176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.07.039

103. Dzhambov AM, Markevych I, Lercher P. Greenspace seems protective of both high and low blood pressure among residents of an Alpine valley. Environ Int. (2018) 121:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.044

104. Yao Y, Li S. Review on research of Urban green space based on public health. Chinese Landsc Archit. (2018) 34:118–24. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6664.2018.01.029

105. Bryant C, Bei B, Gilson K, Komiti A, Jackson H, Judd F. The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental health in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. (2012) 24:1674–83. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000774

106. Schwanen T, Páez A. The mobility of older people - an introduction. J Transp Geogr. (2010) 18:591–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.06.001

107. Rantanen T, Portegijs E, Viljanen A, Eronen J, Saajanaho M, Tsai LT, et al. Individual and environmental factors underlying life space of older people - study protocol and design of a cohort study on life-space mobility in old age (LISPE). BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:1018. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1018

Keywords: neighborhood greenspace, physical health, mental health, older adult, structual equation model, Guangzhou

Citation: Zhou Y, Yuan Y, Chen Y and Lai S (2020) Association Pathways Between Neighborhood Greenspaces and the Physical and Mental Health of Older Adults—A Cross-Sectional Study in Guangzhou, China. Front. Public Health 8:551453. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.551453

Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 14 August 2020;

Published: 22 September 2020.

Edited by:

Zhonghua Gou, Griffith University, AustraliaCopyright © 2020 Zhou, Yuan, Chen and Lai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuan Yuan, yuanyuan@mail.sysu.edu.cn

Yuquan Zhou

Yuquan Zhou Yuan Yuan

Yuan Yuan Yujie Chen

Yujie Chen Shulin Lai

Shulin Lai