94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 30 April 2020

Sec. Infectious Diseases – Surveillance, Prevention and Treatment

Volume 8 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181

This article is part of the Research TopicCoronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Management and Public Health ResponseView all 400 articles

Background: Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging public health problem threatening the life of over 2.4 million people globally. The present study sought to determine knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) of health care workers (HCWs) toward COVID-19 in Makerere University Teaching Hospitals (MUTHs) in Uganda.

Methods: An online cross sectional, descriptive study was undertaken through WhatsApp Messenger among HCWs in four MUTHs. HCWs aged 18 years and above constituted the study population. KAP toward COVID-19 was assessed by using a pre-validated questionnaire. Bloom's cut-off of 80% was used to determine sufficient knowledge (≥80%), positive attitude (≥4), and good practice (≥2.4). All analyses were performed using STATA 15.1 and GraphPad Prism 8.3.

Results: Of the 581 HCWs approached, 136 (23%) responded. A vast majority of the participants were male (n = 87, n = 64%), with a median age of 32 (range: 20–66) years. Eighty-four (62%) were medical doctors and 125 (92%) had at least a bachelor's degree. Overall, 69% (n = 94) had sufficient knowledge, 21% (n = 29) had positive attitude, and 74% (n = 101) had good practices toward COVID-19. Factors associated with knowledge were age >40 years (aOR: 0.3; 95% CI: 0.1–1.0; p = 0.047) and news media (aOR: 4.8; 95% CI: 1.4–17.0; p = 0.015). Factors associated with good practices were age 40 years or more (aOR: 48.4; 95% CI: 3.1–742.9; p = 0.005) and holding a diploma (aOR: 18.4; 95% CI: 1–322.9; p = 0.046).

Conclusions: Continued professional education is advised among HCWs in Uganda to improve knowledge of HCWs hence averting negative attitudes and promoting positive preventive and therapeutic practices. We recommend follow up studies involving teaching and non-teaching hospitals across the country.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 also known as COVID-19 is a rapidly expanding pandemic caused by a novel human coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) previously known as 2019-nCov (1, 2). COVID-19 was first reported in December 2019 among patients with viral pneumonia symptoms in Wuhan, China (3, 4). They were found to be related with the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, in the Hubei province of China, where other non-aquatic animals were also being sold before the outbreak (5). As of 20th April 2020, over 2.4 million cases and 165,000 deaths have been reported globally (6, 7). Europe is the most affected with over 50% of cases and 60% of deaths reported in this region (8). United States of America has the highest number of cases globally (695,350 cases) and the highest number of deaths (32,427 deaths) (8). African region is the least affected with 13,892 cases and 628 deaths, but the numbers are increasing (8). Uganda has so far confirmed 55 cases of COVID-19 as of 20th April 2020 (7, 8).

SARS-COV-2 is transmitted from person-to-person through inhalation of aerosols from an infected individual (3). Old age and patients with pre-existing illnesses (like hypertension, cardiac disease, lung disease, cancer, or diabetes) have been identified as potential risk factors for severe disease and mortality (9, 10). To date, there is no antiviral curative treatment or vaccine that has been recommended for COVID-19 (11). More information about its distribution, transmission, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention are being studied. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends prevention of human-to-human transmission by protecting close contacts and health care workers from being infected and stopping infections from animal sources (8). Primary preventive measures include regular hand washing, social distancing, and respiratory hygiene (covering mouth and nose while coughing or sneezing) (12, 13).

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at the frontline of COVID-19 pandemic response and are exposed to dangers like pathogen exposure, long working hours, psychological distress, fatigue, occupational burnout and stigma, and physical violence (14). A poor understanding of the disease among HCWs can result in delayed identification and treatment leading to rapid spread of infections. Over 100 health workers have lost their lives to COVID−19, a tragedy to the world and a barrier to fight against the disease (15). Guidelines for healthcare workers and online refresher courses have been developed by WHO, CDC, and various governmental organizations in various countries to boost the knowledge and prevention strategies (16). There is paucity of literature on KAPs of HCWs toward the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a study with majorly Asian HCWs and medical students revealed that they had insufficient knowledge about COVID-19 but had a positive attitude toward prevention of COVID-19 transmission (17). To our knowledge, no study has been done in sub-Saharan Africa to assess KAPs toward COVID-19 specifically among HCWs. The purpose of the study was to assess the KAPs of HCWs in Uganda toward COVID-19.

An online cross-sectional study was conducted in the first week of April 2020 at four (4) teaching hospitals of Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS), Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, i.e., Mulago National Referral Hospital, Mulago Specialized Women and Neonatal Hospital, Kiruddu National Referral Hospital (Directorate of Medicine), and Kawempe National Referral Hospital (Directorate of Obstetrics and Gynecology). The hospitals are components of Mulago Hospital Complex, the largest public hospital in Uganda. The total bed capacities of these hospitals are estimated at 1,800 as of April 2020. There are ~1,300–1,500 healthcare workers.

HCWs (nurses, midwives, internship doctors, medical officers, senior house officers, and specialists) practicing in any of the four MakCHS teaching hospitals who were aged 18 years and above were included in the study after an informed consent. HCWs who were too ill to participate were excluded.

Due to the country's lockdown at the time of data collection, we opted to use WhatsApp Messenger (Facebook, Inc., California, USA) for enrolling potential participants. We identified all the existing HCWs WhatsApp groups of the four MaKCHS teaching hospitals. A total of 581 HCWs who were members in the several WhatsApp groups were approached to participate in the study. An online data collection tool was designed and executed using Google Forms (via docs.google.com/forms). The Google Form link to the questionnaire was sent to the enrolled participants via the identified WhatsApp groups.

HCWs are defined as all people engaged in activities whose primary intention is to improve health (18). For the purpose of this study, healthcare professionals in primary contact with patients were enrolled. These included nurses, midwives, intern doctors, medical officers, senior house officers, and specialists.

Demographic details which include sex, age, academic qualification, highest level of education, and sources of information on COVID-19.

Knowledge, attitude and practices toward COVID-19.

Knowledge was assessed using a 11-item questionnaire adapted from Zhong et al. (19) and modified to suit HCWs, each correct answer weighing one point. The questions were about clinical presentations, transmission, prevention and control of COVID-19. Each correct response weight 1 point and 0 for incorrect responses. The higher the points, the more knowledgeable the HCW is.

Attitudes were assessed using 5 Likert-item questions that have been adopted from Goni et al. (20) and modified appropriately for COVID-19 by the authors. The responses were; strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and strongly agree each weighing 1–5 respectively for each positive statement. Some questions were reversed to eliminate biases of giving a single similar response in all the items.

Practices were assessed using five Likert-item questions that have been developed from the WHO and Ministry of Health Uganda recommended practices for prevention of COVID-19 transmission i.e., hand washing, avoiding crowded places, keeping social distance (1 meter apart), avoiding touching of face, and avoiding handshakes. The responses were; always, occasional, and never each weighing 3, 2, and 1 point respectively for a good practice. The link to the questionnaire can be accessed in the Supplementary Material section below.

Fully completed questionnaires were extracted from Google Forms and exported to a Microsoft Excel 2016 for cleaning and coding. The cleaned data was exported to STATA version 15.1 and GraphPad 8.3 for analyses. Numerical data was summarized as means and standard deviations or median and range as appropriate. Categorical data was summarized as frequencies and proportions. Bloom's cut-off of 80% was used to determine sufficient knowledge (≥80%), positive attitude (≥4), and good practice (≥2.4) (21). Associations between independent variables and dependent variables were assessed using multivariate analysis in STATA 15.1 software. Kruskalis-Wallis and One-Way Analysis of Variance using GraphPad Prism 8.3 was done to compare KAPs across groups. A p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. The data set can be accessed via a link provided in the Supplementary Materials section.

Of the 581 HCWs approached, total of 136 HCWs responded (response rate = 23%). A vast majority of the participants were male (n = 87, 64%), with a mean age of 34 (SD: 7.9) years and below 40 years of age (n = 107, 79%). Majority of the participants were practicing in Mulago National Referral Hospital (n = 73, 54%) and a minority in Mulago Women and Neonatal Hospital (n = 8, 6%). Eighty-four (62%) participants were medical doctors, 15 (11%) were nurses, and 7 (5) were midwives. Of the 136 participants, 125 (92%) had at least a bachelor's degree and a minority had an ordinary diploma or a certificate. The main sources of information about COVID-19 among participants were information from international health organizations like the CDC and WHO, Ministry of Health, Uganda media sites, News Media and social media such as WhatsApp and Facebook. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

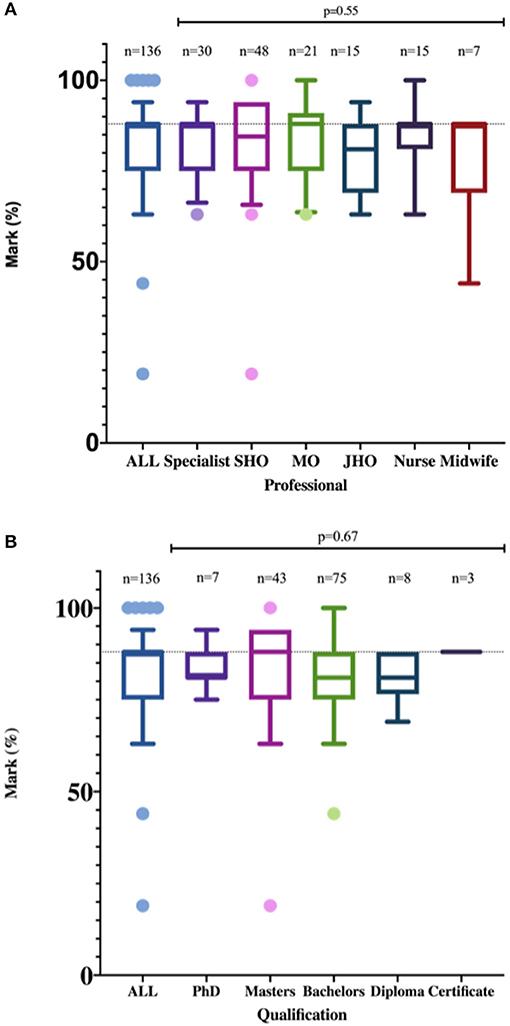

The mean knowledge score was 82.4 (SD: 11.2) percent. Sixty-nine percent (n = 94) of the participants scored 80% or more and were considered to have sufficient knowledge. Only two participants scored below 50%. Factors associated with knowledge were age >40 (aOR: 0.3; 95% CI: 0.1–1.0; p = 0.047) and news media (aOR: 4.8; 95% CI: 1.4–17.0; p = 0.015, Table 4). The mean knowledge score of male participants was higher than those of female participants (83.2 vs. 80.9%), However this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.38). The level of knowledge among the healthcare workers were similar irrespective of the cadre (p = 0.55) or academic qualifications (p = 0.67, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Level of Knowledge of healthcare workers stratified by profession (A) and qualifications (B). There was no statistically significant difference in the level of knowledge about COVID-19 among health care workers in Uganda irrespective of their professions or qualifications.

The mean attitude score 3.4 (SD: 0.6). Overall, there was poor attitude among HCWs toward COVID-19. Only 21% (n = 29) of the participants had a good attitude toward COVID-19. Of these, 59% (n = 17) and 62% (n = 18) were males and from Mulago National Referral Hospital, respectively. Ten percent (n = 13) reported that black race is protective against COVID-19 and only 44% (n = 60) were confident that they would participate in the management of a patient with COVID-19 (Table 2). When asked about the preparedness of Uganda, up to 29% (n = 40) believed that Uganda was not in a good position to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 2 shows the frequency of the responses and Table 3 shows the mean attitude scores and percentage of HCWs with good attitude. In Table 4, multivariate analysis revealed that HCWs who used mainstream media like television to access information on COVID-19 were four times more likely to have a good attitude, this was however not statistically significant (aOR = 3.7, 95% CI = 0.8–16.8, p = 0.085). There was no statistically significant correlation between attitude and the sociodemographic variable (sex, age, hospital, qualification, and level of education) at (p < 0.05, Table 4.)

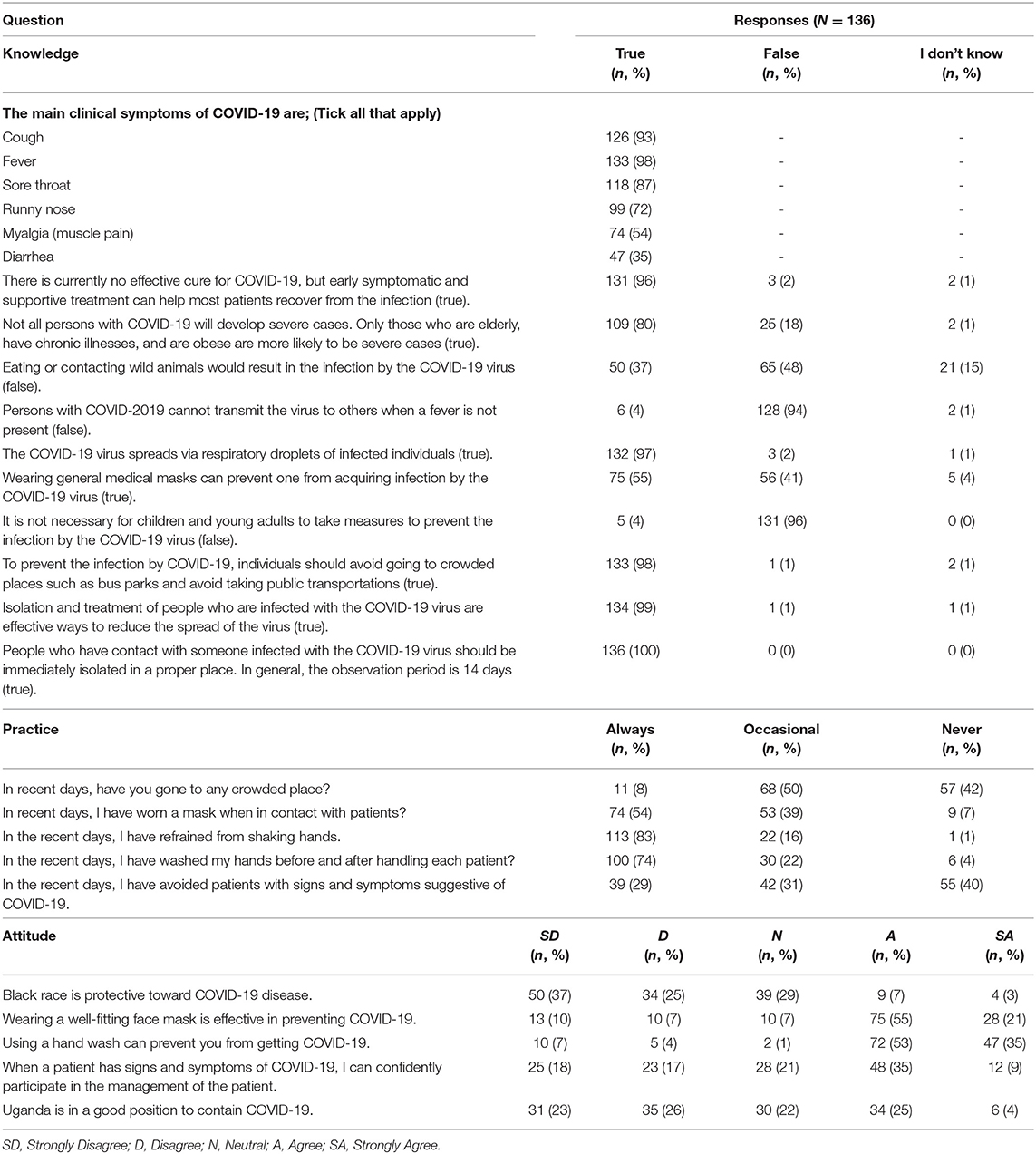

Table 2. Knowledge, attitude and practices of healthcare workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals toward COVID-19.

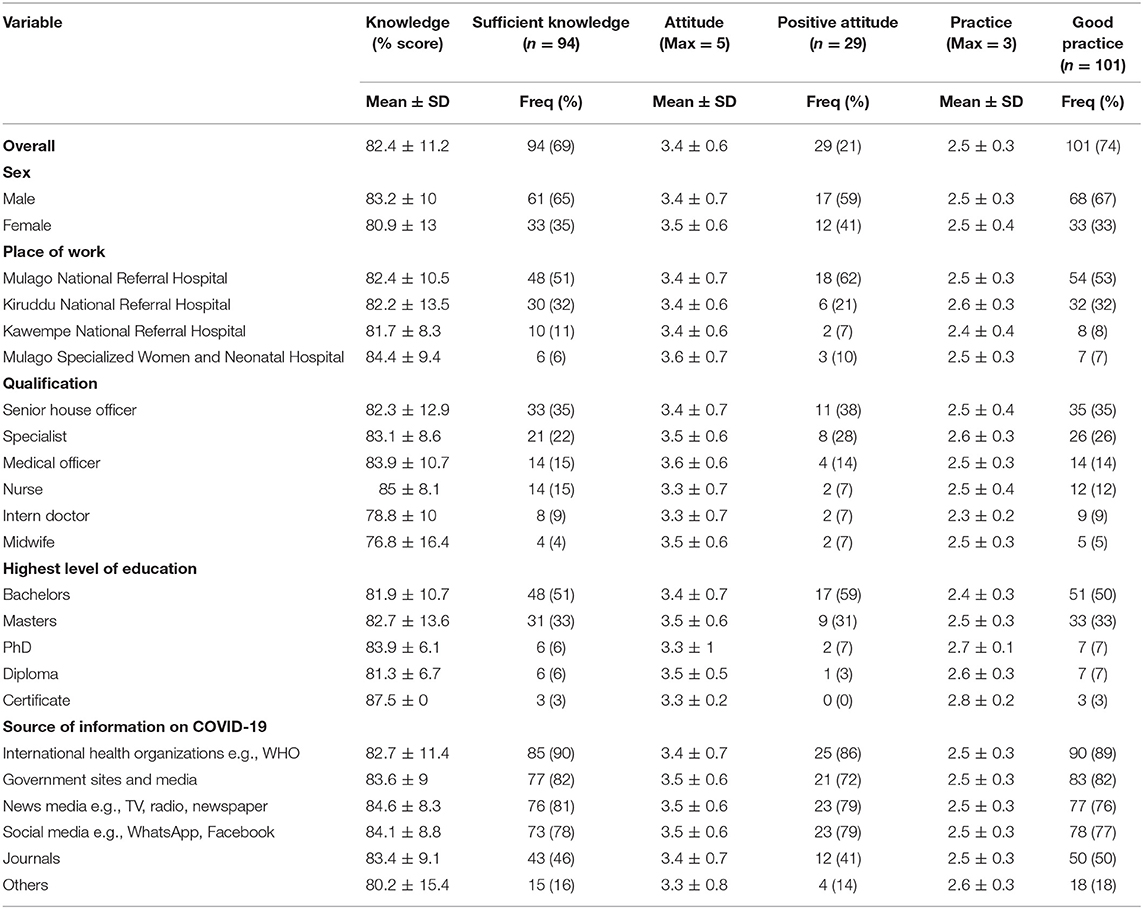

Table 3. Knowledge, attitude and practices among healthcare workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals.

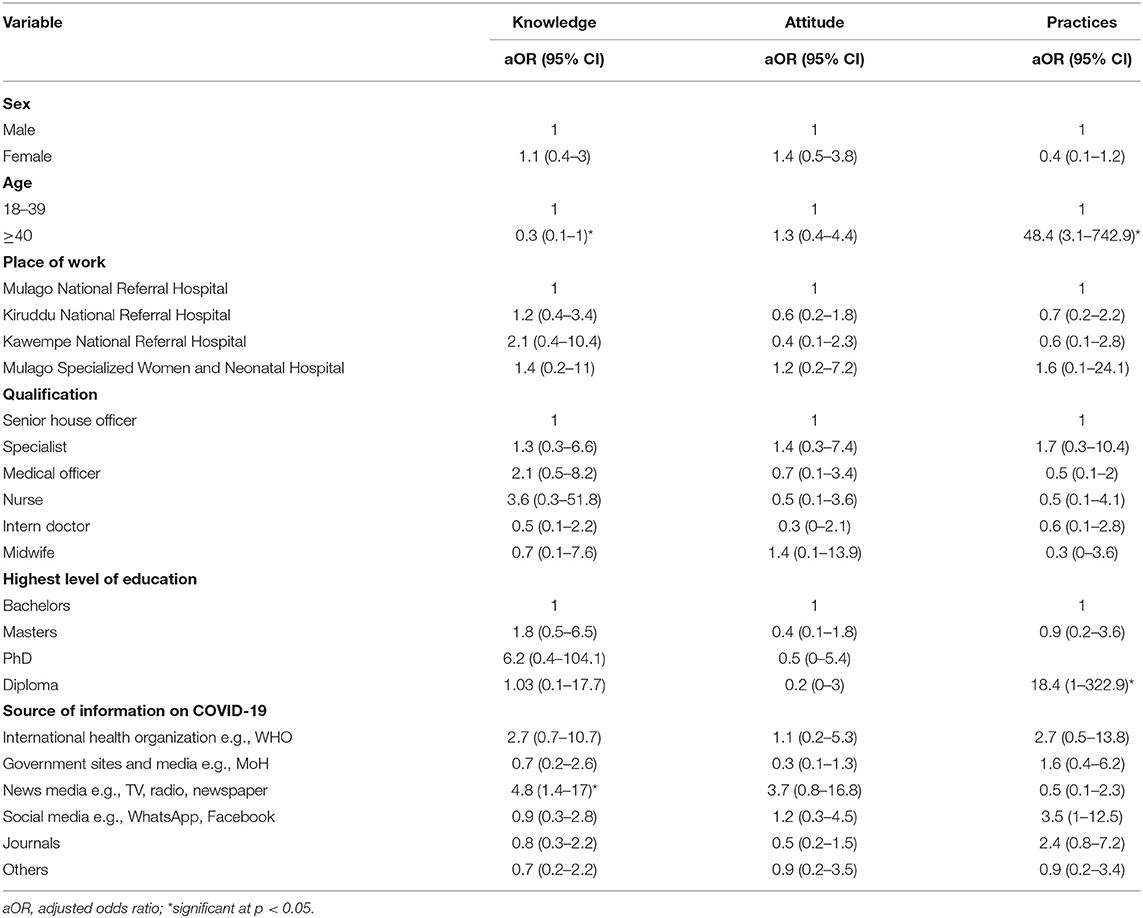

Table 4. Factors associated with knowledge, attitude and practices among healthcare workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals.

Some 54% (n = 74) of the HCWs always wore a mask when coming into contact with the patients and up to 96% (n = 130) washed their hands before and after touching each patient. Unfortunately, as high as 60% (n = 81) of the participants had avoided patients with symptoms similar to those of COVID-19 (Table 2). Overall, up to 74% (n = 101) of the participants had good practices (mean score ≥ 2.4, Table 3). Age ≥ 40 and HCWs with diploma were significantly (p < 0.05) more likely to have good practices (Table 4).

COVID-19 is an emerging, rapidly changing global health challenge affecting all sectors (22, 23). HCWs are not only at the forefront of the fight against this highly contagious infectious disease but are also directly or indirectly affected by it and the likelihood of acquiring this disease is higher among HCWs compared to the general population (15). It is therefore of paramount importance that HCWs across the world have adequate knowledge about all aspects of the disease from clinical manifestation, diagnosis, proposed treatment, and established prevention strategies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Uganda and the sub-Saharan Africa to assess the KAPs of HCWs toward COVID-19. There are also very limited studies that document KAPs among HCWs globally. In the present study, we were able to demonstrate that about seven in 10 of the HCWs had sufficient knowledge about COVID- 19. Among these HCWs, the level of knowledge about COVID-19 was similar irrespective of the age, sex, academic qualification or profession of the HCW.

From our study, a mean knowledge score of 82.4% was obtained on questions about knowledge indicating good knowledge among HCWs at MaKCHS Teaching Hospitals. However, this score is much lower than that reported in Chinese general population (90%) (19) but slightly higher than the KAP toward COVID-19 among US residents (80%) (24). This is possibly because the Chinese and the US studies assessed COVID-19 symptoms using one direct question rather than asking the participants to choose from multiple options. Generally, majority of the HCWs had sufficient knowledge about COVID-19 which is in line with findings in Vietnam about COVID-19 (25). In contrast, it is conflicting to surveys by Bhagavathula et al. on COVID-19 (17), a baseline study among nurses in Gabon on Ebola (26) and HCWs in Ethiopia on Ebola (27) who all reported poor knowledge. From our study, 69% of HCW had sufficient knowledge about COVID-19 which is lower than values reported by Huynh et al. where 88.4% had sufficient knowledge on COVID-19 (25). Further education and training through continuous professional education and journal clubs, particularly on symptoms and transmission are essential in improving the knowledge of HCW about COVID-19 in our setting.

In our study, most of the participants used information from international and governmental media (websites and verified social media pages). Our study suggests that knowledge on COVID-19 was significant among HCWs who used news media such as televisions. This suggests that such media should be frequently used to disseminate information on COVID-19 by the stakeholders. Younger HCW (<40 years) were more likely to have knowledge about COVID-19 unlike in Vietnam where age did not predict knowledge (25). This age difference may be partly due to the diversity of the sources of information frequently used by younger HCW.

About 17% of HCW believed that wearing general medical masks was not protective against COVID-19 contrary to findings by Ng et al. which showed adequate protection (28). However, an ideal mask for the prevention of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is an area of current research. Our study reveals that majority of HCWs at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals have a negative attitude toward COVID-19 which is in congruence with a KAPs study on Ebola in Ethiopia among HCWs (27) but in contrast to Giao's study on COVID-19 (25). Only 44% of the HCWs in our study agreed that they could confidently participate in the management of patients with COVID-19 which implies that adequate information on COVID-19 case management should be provided to the HCWs. However, attitude was not significantly determined by knowledge.

Our study shows that HCWs in Makerere University Teaching Hospitals have good COVID-19 prevention practices similar to findings by Alfahan et al. on coronaviruses (29), Raab et al. on Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea (30) and in the general population of the Chinese on COVID-19 (19). Majority of the HCWs are following infection prevention and control practices recommended by the Ministry of Health Uganda and WHO. These include regular hand hygiene, social distancing and wearing a face mask when in high risk situations. Ninety-three percent and 96% of HCWs reported wearing a face mask when in contact with patients and washing hands before/after handling patients. These are very vital practices to prevent transfer of COVID-19 from patients to patients and to the HCWs themselves. However, up to 60% of HCWs admitted having avoided patients with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19. This can be attributed to shortage of personal protective equipment which has become a global problem (31–33).

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, no standardized tool for assessing KAPs on COVID-19 has been previously validated. We have however adapted and modified a previously published tool for assessment of KAP toward prevention of respiratory tract infections; and a tool used to assess KAP among Chinese residents (19, 20). The questions have been formulated from WHO and CDC guidelines and reports on COVID-19 (12). Secondly, only HCWs in Makerere University Teaching Hospitals were surveyed and the results of this study may not reflect the KAPs of HCWs in the entire country. However, this is the first study to assess KAPs, can be used to formulate targeted Continuing Medical Education (CME) for HCWs and enrolled in a countrywide survey and training on COVID. A similar study may be extended to the community. The study also had a low response rate (23%), which has been documented in web-based surveys especially among professionals (34) and this limits the survey's generalization.

In conclusion, we found that more than two-third of HCWs in Makerere University Teaching Hospitals have sufficient knowledge on the transmission, diagnosis and prevention of the transmission of COVID-19. Knowledge on COVID-19 was significantly higher among HCWs who used news media such as televisions and newspapers and those aged 18–39 were more knowledgeable about COVID-19. There was no statistically significant difference in the level of knowledge about COVID-19 among health care workers in Uganda irrespective of their professions or qualifications. About four-fifth of the respondents had poor attitude toward COVID-19 and just over 70% of the HCWs had good practices toward COVID-19 especially those aged 40 years or more. Continued professional education is advised among HCWs in Uganda to improve knowledge of HCWs hence averting negative attitudes and promoting positive preventive and therapeutic practices. We recommend follow up studies involving teaching and non-teaching hospitals across the country.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

The proposal has been cleared by Mulago Hospital Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) Protocol Number MHREC 1866. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants signed a written informed consent.

RO and FB designed the study protocol and analyzed the data and drafted the original manuscript. RO, FB, GC, GW, and DN participated in data collection. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We acknowledge the following for helping with data collection; Dr. Darius Owachi, Dr. Gloria Owomugisha, Dr. Sarah Nakubuulwa, Dr. Bazil Ogik-Koma, Dr. Setih Taremwa, and Mr. Edward Kakooza.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181/full#supplementary-material

Questionnaire:

doi: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12162045

Dataset:

doi: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12161910

1. World Health Organisation. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 51. Geneva: WHO. (2020). Available online at: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed March 18, 2020).

2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

3. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

4. Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:401–2. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678

5. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, DiNapoli R. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19) [Updated 2020 Apr 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2020).

6. John Hopkins University. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). (2020). Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed April 20, 2020).

7. Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Dover, Delaware: Worldometers.info. (2020). Available online at: www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed April 20).

8. World Health Organisation. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 90. Geneva: WHO. (2020). Available online at: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed April 20, 2020).

9. Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:425–34. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4

10. Tian S, Hu N, Lou J, Chen K, Kang X, Xiang Z, et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect. (2020) 80:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018

11. Sahin AR, Erdogan A, Agaoglu PM, Dineri Y, Cakirci AY, Senel ME, et al. 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a review of the current literature. EJMO. (2020) 4:1–7. doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2020.12220

12. World Health Organisation. Infection Prevention and Control During Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection is Suspected, World Health Organization: Geneva (2020).

13. World Health Organisation. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. (2020). Available online at: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed April 01, 2020).

14. World Health Organisation. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak: Rights, Roles and Responsibilities of Health Workers, Including Key Considerations for Occupational Safety and Health. (2020). Available online at: www.who.int/publications-detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-outbreak-rights-roles-and-responsibilities-of-health-workers-including-key-considerations-for-occupational-safety-and-health (accessed April 05, 2020).

15. MedScape. In Memoriam: Healthcare Workers Who Have Died of COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927976 (accessed April 06, 2020).

16. World Health Organisation. Emerging Respiratory Viruses, Including COVID-19: Methods for Detection, Prevention, Response and Control. (2020). Available online at: www.openwho.org/courses/introduction-to-ncov (accessed March 18, 2020).

17. Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, Mahabadi MA, Bandari DK. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions: a survey on healthcare workers. medRxiv. [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.2196/19160

18. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2006).

19. Zhong B-L, Luo W, Li H-M, Zhang Q-Q, Liu X-G, Li W-T, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1745–52. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221

20. Goni MD, Naing NN, Hasan H, Wan-Arfah N, Deris ZZ, Arifin WN, et al. Development and validation of knowledge, attitude and practice questionnaire for prevention of respiratory tract infections among Malaysian Hajj pilgrims. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:189. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8269-9

21. Kaliyaperumal K. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS illumination. (2004) 4:7–9. Available online at: http://v2020eresource.org/content/files/guideline_kap_Jan_mar04.pdf

22. Kassema J. J. COVID-19 outbreak: is it a health crisis or economic crisis or both? Case of African Counties. SSRN Electr J. (2020) 9:4–14. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3559200

23. McKibbin WJ, Fernando R. The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: seven scenarios. SSRN Electr J. (2020) 20–24. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3547729

24. Clements JM. Knowledge and behaviors toward COVID-19 among US residents during the early days of the pandemic. medRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.31.20048967

25. Giao H, Han NTN, Van Khanh T, Ngan VK, Van Tam V, Le An P. Knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 among healthcare workers at District 2 Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 13:3–5. doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.280396

26. Rehman H, Ghani M, Rehman M. Effectiveness of basic training session regarding the awareness of Ebola virus disease among nurses of public tertiary care hospitals of Lahore. JPMA J Pakistan Med Assoc. (2020) 70:477. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.15677

27. Abebe TB, Bhagavathula AS, Tefera YG, Ahmad A, Khan MU, Belachew SA, et al. Healthcare professionals' awareness, knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and beliefs about Ebola at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health Africa. (2016) 7:570. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2016.570

28. Ng K, Poon BH, Kiat Puar TH, Shan Quah JL, Loh WJ, Wong YJ, et al. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Ann Intern Med. (2020). doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [Epub ahead of print].

29. Alfahan A, Alhabib S, Abdulmajeed I, Rahman S, Bamuhair S. In the era of corona virus: health care professionals' knowledge, attitudes, and practice of hand hygiene in Saudi primary care centers: a cross-sectional study. J Commun Hospital Int Med Perspect. (2016) 6:32151. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v6.32151

30. Raab M, Pfadenhauer LM, Millimouno TJ, Hoelscher M, Froeschl G. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards viral haemorrhagic fevers amongst healthcare workers in urban and rural public healthcare facilities in the N'zérékoré prefecture, Guinea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8433-2

31. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Livingston EH. Conserving Supply of personal protective equipment-a call for ideas. JAMA. (2020). doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4770

32. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages-the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. (2020). doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006141

33. World Health Organization. Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Interim Guidance. Geneva: WHO (2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, Uganda, KAPs, healthcare workers, Makerere University Teaching Hospitals

Citation: Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR and Bongomin F (2020) Coronavirus Disease-2019: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Health Care Workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front. Public Health 8:181. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181

Received: 10 April 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020;

Published: 30 April 2020.

Edited by:

Zisis Kozlakidis, International Agency for Research On Cancer (IARC), FranceReviewed by:

Jeffrey G. Chipman, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Olum, Chekwech, Wekha, Nassozi and Bongomin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ronald Olum, b2x1bS5yb25hbGRAZ21haWwuY29t; Felix Bongomin, ZHJib25nb21pbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Ronald Olum orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-0111

Felix Bongomin orcid.org/0000-0003-4515-8517

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.