95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Public Health , 11 June 2019

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 7 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00152

This article is part of the Research Topic Methods and Applications in Implementation Science View all 20 articles

Elizabeth L. Budd1*

Elizabeth L. Budd1* Xiangji Ying2

Xiangji Ying2 Katherine A. Stamatakis3

Katherine A. Stamatakis3 Anna J. deRuyter2

Anna J. deRuyter2 Zhaoxin Wang4

Zhaoxin Wang4 Pauline Sung5

Pauline Sung5 Tahna Pettman6

Tahna Pettman6 Rebecca Armstrong6

Rebecca Armstrong6 Rodrigo Reis2,7

Rodrigo Reis2,7 Ross C. Brownson2

Ross C. Brownson2Background: Understanding the contextual factors that influence the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based chronic disease prevention (EBCDP) interventions in public health settings across countries could inform strategies to support the dissemination and implementation of EBCDP interventions globally and more effectively prevent chronic diseases. A survey tool to use across diverse countries is lacking. This study describes the development and reliability testing of a survey tool to assess the stage of dissemination, multi-level contextual factors, and individual and agency characteristics that influence the dissemination and implementation of EBCDP interventions in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States.

Methods: Development of the 26-question survey included, a narrative literature review of extant measures in EBCDP; qualitative interviews with 50 chronic disease prevention practitioners in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States; review by an expert panel of researchers in EBCDP; and test-retest reliability assessment.

Results: A convenience sample of practitioners working in chronic disease prevention in each country completed the survey twice (N = 165). Overall, this tool produced good to moderately reliable responses. Generally, reliability of responses was higher among practitioners from Australia and the United States than China and Brazil.

Conclusions: Reliability findings inform the adaptation and further development of this tool. Revisions to four questions are recommended before use in China and revisions to two questions before use in Brazil. This survey tool can contribute toward an improved understanding of the contextual factors that public health practitioners in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States face in their daily chronic disease prevention work related to the dissemination and implementation of EBCDP interventions. This understanding is necessary for the creation of multi-level strategies and policies that promote evidence-based decision-making and effective prevention of chronic diseases on a more global scale.

Chronic diseases are a threat to global health, in developed and developing countries alike, accounting for 60% of deaths worldwide (1). The medical costs and loss of productivity related to chronic diseases are a great financial burden to individuals and economies (1). Evidence-based chronic disease prevention (EBCDP) interventions are effective tools for preventing chronic diseases (2). However, studies among U.S. and European public health practitioners indicate that only 56–64% of chronic disease prevention interventions currently in use are evidence-based (3, 4), while estimates of use of EBCDP interventions in lower and middle income countries are unknown. Studies in Australia and the United States have identified multi-level contextual factors that influence the dissemination and implementation (D&I) of EBCDP interventions. Examples of these contextual factors include individual- and agency-level capacity characterized by the training, structure, material and human resources at hand that hinder or facilitate the use of EBCDP interventions (2, 5–7). Additional work has addressed some of the contextual barriers by training practitioners on the evidence-based decision-making process, specifically clarifying the reasons for selecting EBCDP interventions and outlining how to find the interventions and resources to support effective implementation and quality improvement (3, 4, 7). These studies report increases in the D&I of EBCDP interventions among practitioners who attended the trainings. Research on Canadian public health departments has identified tailored messaging as an effective method for promoting the D&I of evidence-based interventions (8), and examined the pathways through which evidence is shared through organizational systems (9). These contextually specific findings inform next steps in addressing barriers and promoting evidence-based decision-making across the Canada. Little is known about these contextual factors that influence the D&I of EBCDP interventions in developing countries, nor the similarities and differences of contextual factors across countries. Several studies call for global strategies to improve the D&I of EBCDP interventions in order to more effectively reduce chronic diseases around the world (10–12). Reviews of measures used to assess the contextual factors that influence the D&I of EBCDP interventions highlight a lack of psychometric testing of the existing measures and room for improvement among those that have been tested (13–15). To assess cross-country contextual factors and inform globally-focused recommendations for facilitating the D&I of EBCDP interventions, a single survey tool that can be used across multiple, diverse countries is needed.

This study provides a detailed overview of the development and test-retest reliability of a survey tool to measure the stage of dissemination, multi-level contextual factors, and individual and agency characteristics that influence the D&I of EBCDP interventions in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States. These countries were chosen for several reasons including, their leadership in distinct regions of the world (16–20), differences on contextual variables of interest (e.g., sociocultural, political/economic) (21), and high prevalence of chronic diseases (22). The World Health Organization reports from 2014 showed that the large majority of deaths in each of the four countries was due to chronic diseases (91% in Australia, 88% in the United States, 87% in China, and 74% in Brazil) (22). Further, based on the few studies of the D&I of EBCDP from Brazil and China (23, 24), compared with the many from Australia and the United States (25–29), Brazil, and China were selected as countries likely in earlier stages of dissemination of EBCDP than Australia and the United States.

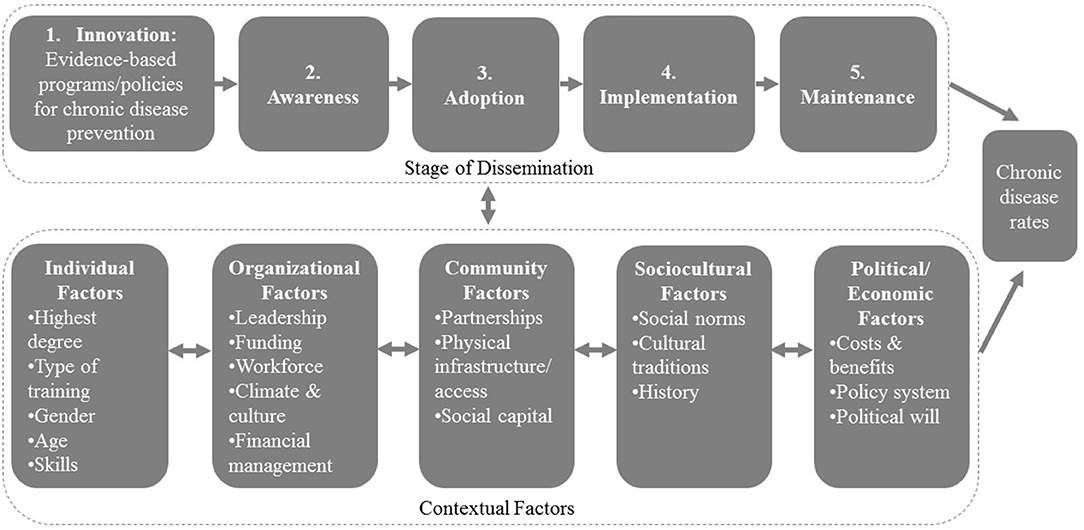

Development of the 26-question survey occurred in several stages. First, a guiding framework was developed based on previous work (30, 31) of the research team (see Figure 1). This framework informed subsequent stages of survey tool development, ensuring that qualitative interview questions and initial survey drafts were literature-based and comprehensive from the outset.

Figure 1. Factors affecting the stages of dissemination of evidence-based programs and policies for chronic disease prevention.

Second, a narrative literature review of extant measures in EBCDP was carried out in order to identify relevant questions and gaps in the D&I of EBCDP literature (2, 6, 31–35). Third, between February and July 2015 semi-structured interviews of public health practitioners in Australia (n = 13), Brazil (n = 9), China (n = 16), and the United States (n = 12) were conducted by trained researchers. Practitioners were identified through purposive sampling based on their employment at agencies responsible for the prevention of chronic disease in each country, including community health services, regional health departments, and non-government organizations (Australia); the ministry of health and local health departments (Brazil); hospitals, community health centers, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (China); and local health departments (United States). The interviews were performed in English, Chinese, or Portuguese, audio recorded, transcribed, translated to English by two bi-lingual research team members (n = 25) when appropriate, and analyzed using deductive, hierarchical coding in NVivo version 10.

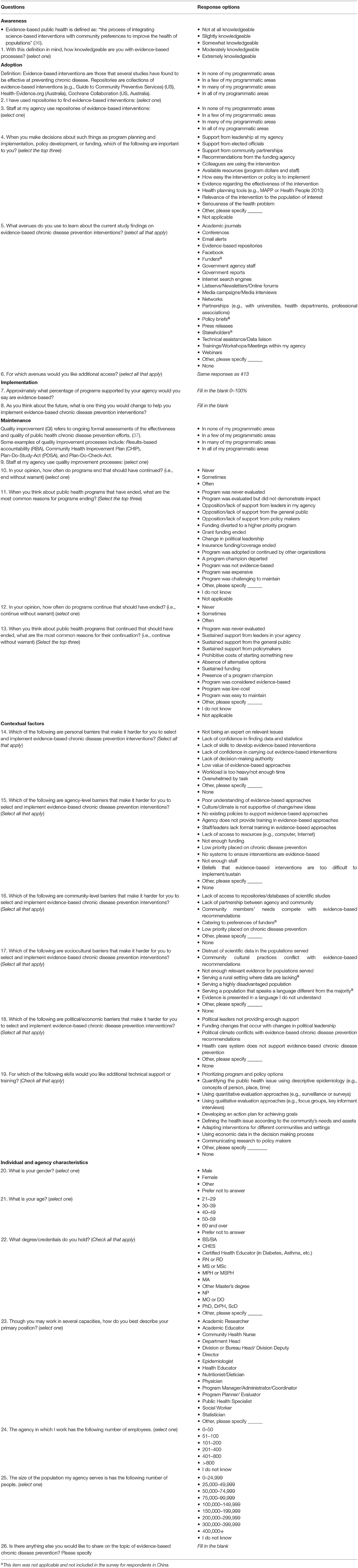

Forth, drafts of the survey underwent expert review by 13 chronic disease prevention researchers and were translated forward and backward to Chinese and Portuguese from English. Survey questions were organized into one of the five stages of dissemination or as multi-level contextual factors seen in Figure 1. Individual and agency characteristics were also included. Seven response items were deemed non-applicable or inappropriate for China contexts, but were included in the survey for the other three countries. These response items and the resulting tool can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Factors influencing the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based chronic disease prevention across four countries: a survey tool.

Fifth, research team members in each country recruited public health practitioners working in chronic disease prevention, primarily on the local and regional levels, in each of the four countries to complete the survey. Samples of practitioners from various regions of each country were identified through national databases and networks of chronic disease prevention practitioners between November 2015 and April 2016. Public health systems across countries varied so much that there was no equivalent sampling method that worked for all four countries. In the United States, a stratified (by region) random sample of chronic disease prevention practitioners from a national database received up to three emails and two follow-up telephone calls requesting participation in the electronic survey (58% response rate). In Australia, up to two emails requesting participation in the electronic survey were sent to all chronic disease practitioners in a national registry (18% response rate). In Brazil, the same protocol as was followed in the United States was used, but with an additional follow-up telephone call (46% response rate). In China, a convenience sample of practitioners working within a network of community hospitals received one email and one follow-up telephone call requesting participation in the electronic survey (87% response rate). All surveys were delivered by an email embedded link and completed electronically. Upon completion of the survey, all respondents were asked to re-take the survey two to three weeks later for test-retest reliability testing purposes. This process was repeated until each respondent to the survey had been contacted twice, requesting them to retake the survey. Calculating Cohen's kappa and Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.50 to 0.70 require a sample size of 25–50 test-retest pairs, respectively (38), thus 25 pairs were the minimum, but 50 pairs were the goal. During data collection, political events in Brazil affected the work lives of many Brazilian chronic disease practitioners and made recruitment of Brazilian practitioners extraordinarily difficult (39, 40). The data collection period was extended for research team investigators in Brazil in order to reach the minimum sample size.

This study was carried out in accordance with the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki with informed consent from all subjects. After reading the electronic informed consent document, subjects indicated their consent by selecting a radial button at the bottom of the informed consent document that read, “I consent to participate in this research study.” Additional written documentation of consent was waived and the protocol was approved by The University of Melbourne Human Ethics Committee, Pontifica Universidade Catolica do Parana Research Ethics Committee, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Human Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health and Social Science, and Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board.

Test-retest reliability was examined on the survey questions, excluding open-ended questions and individual and agency characteristics. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated for questions with ordinal response options (questions 1 through 3, 9, 10, and 12; see Table 1). “I don't know” and “not applicable” response options were not included in the ICC calculations. Each response item for questions 4, 5, 11, and 13 through 19 was dichotomized to reflect whether a respondent selected the response option or not. Cohen's kappa was run for each of these response options individually. The mean of all of the Cohen's kappas for each question's set of response options was calculated. Cut-points for ICC and mean kappa (excellent: ≥0.801; good: 0.601–0.80; moderate: 0.401–0.60; poor: ≤0.40) were selected based on recommendations (41, 42), and to aid in the interpretation of the results. Percentage agreement was also calculated for all of the aforementioned questions, excluding question 7, which asked respondents to provide a percentage. Questions for which mean kappa was calculated, mean percentage agreement was also calculated. Cut-points for percentage agreement included: excellent: 89.5–100%; good: 74.5–89.4%; moderate: 60–74.4%; and poor: <60%. All analyses were conducted in Stata version 14.

There were 400 survey respondents total and 165 of them took the survey twice for test-retest reliability purposes (N = 39 from Australia; N = 27 from Brazil; N = 45 from China; N = 54 from the United States). The test-retest respondents were all public health practitioners (e.g., nutritionist/dietician, coordinator, community health nurse) working in chronic disease prevention. Public Health Specialist was added as a primary employment position option post hoc, in order to capture a common “other” response provided by practitioners from Brazil. Respondents were primarily female (79%) between 30 and 49 years old (53%). The mean survey completion time varied by country, with Brazil having the longest (33.2 min ± 27.8), followed by the United States (17.72 min ± 13.4), Australia (16.6 min ± 10.0), and China (13.8 min ± 10.5). The mean number of days between test and retest was greatest in Brazil (46.4 ± 28.5), followed by Australia (39.0 ± 2.8), China (23.7 ± 7.6) and the United States (21.0 ± 9.1). Table 2 shows frequency counts for each response option by country, the first time respondents completed the survey. Item responses vary in prevalence from zero endorsements to endorsement from a large majority of a county's sample.

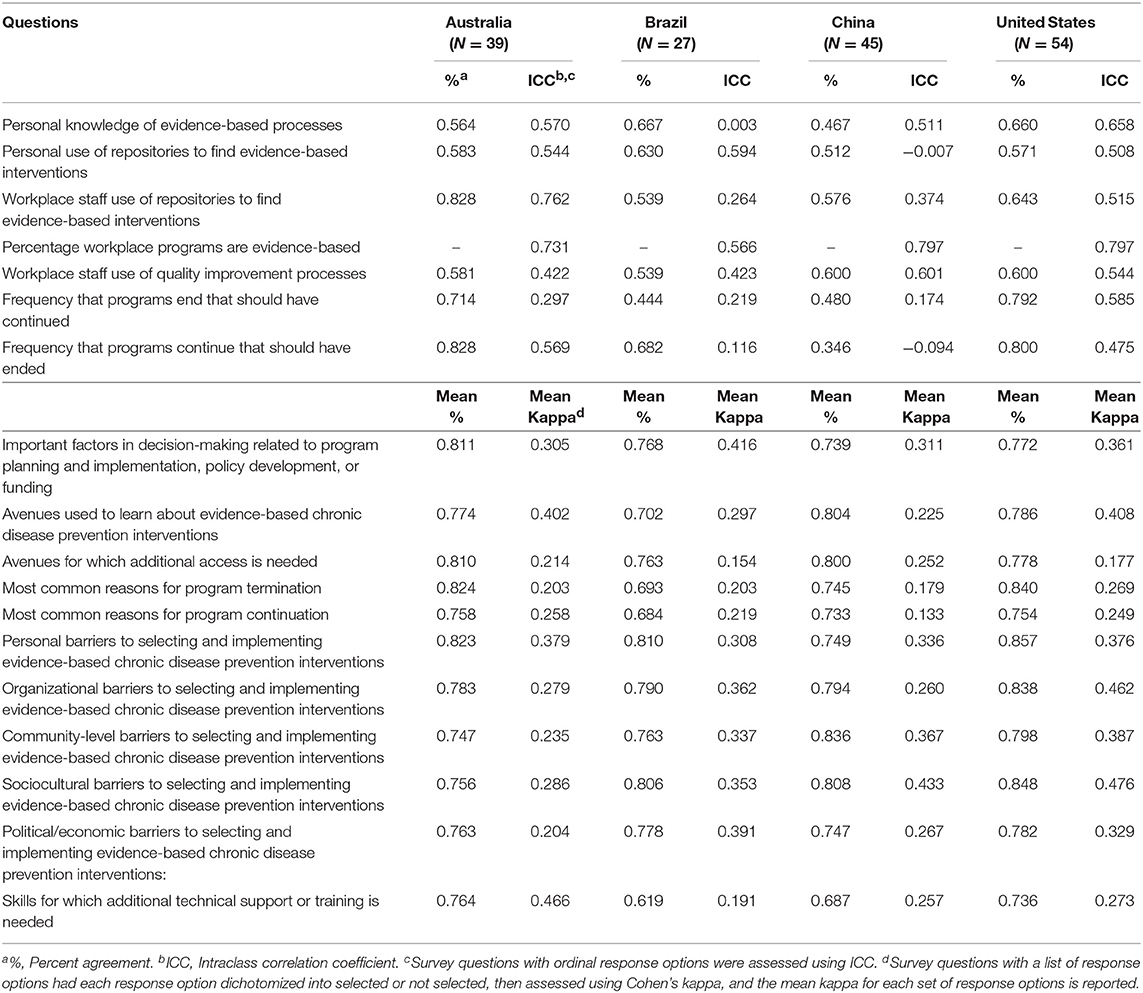

The test-retest reliability coefficients and percentage agreement by question and country appear in Table 3. Of the seven questions with ordinal response options assessed using ICC, six and seven demonstrated good to moderate reliability among practitioners from Australia and the United States, respectively, whereas three questions among practitioners from Brazil and China demonstrated good to moderate reliability. Six of those seven questions were also assessed using percentage agreement. Six and five of the questions demonstrated good to moderate percentage agreement among practitioners from Australia and the United States, respectively, whereas three questions among practitioners from Brazil and one among practitioners from China demonstrated moderate percentage agreement at best.

Table 3. Test-retest percent agreement and reliability coefficients by question and country (N = 165).

Of the 11 questions whose response options were dichotomized and assessed using mean Cohen's kappa, few questions among practitioners across all four countries showed moderate mean reliability at best (Australia, N = 2; Brazil, N = 1; China, N = 1; United States, N = 3). Mean percentage agreement told a different story for these 11 questions. All but one question showed good mean percentage agreement among practitioners from Australia and the United States. Seven and five questions showed good mean percentage agreement among practitioners from Brazil and China, respectively. The remaining of the 11 questions across the countries showed moderate mean percentage agreement.

The following four questions produced less than moderately reliable responses based on both ICC and percentage agreement among practitioners in China: Personal use of repositories to find evidence-based interventions; Workplace staff use of repositories to find evidence-based interventions; Frequency that programs end that should have continued; and Frequency that programs continue that should have ended. Two of those questions (Workplace staff use of repositories to find evidence-based interventions, and Frequency that programs end that should have continued) produced less than moderately reliable responses among practitioners from Brazil based on both measures of reliability as well.

The development and reliability testing of this survey tool are important early steps toward facilitating population-level research that can increase our knowledge of country-specific and cross-country contextual factors that influence the D&I of EBCDP interventions and, in turn, begin to inform more global strategies for improving the D&I of EBCDP. This study, novel in its common methods across countries, showed that the measurement tool produced moderate to good reliability of responses, with at least one measure of reliability, among 14 of the 18 questions across all four countries.

Reliability findings inform the adaptation and further development of this tool. For example, the authors recommend revising the four questions pertaining to personal and workplace staff use of repositories for finding evidence-based interventions and frequency that programs end or continue without warrant before further use among practitioners in China and Brazil. The poor reliability of responses produced from these questions among practitioners from Brazil and China reflect a difference in how they relate to the content of the questions, compared with practitioners from Australia and the United States. This difference may highlight meaningful differences within contexts with respect to D&I processes and structures. For instance, practitioners in countries for which EBCDP is in an earlier stage of dissemination tend to be less knowledgeable about key concepts of EBCDP, making the questions conceptually more difficult and in turn negatively influencing the reliability of their responses (43). Another potential contributing factor to the lower reliability among responses from practitioners in Brazil and China is that the survey tool had to be translated from English to Chinese and Portuguese. Tanzer and Sim review international guidelines on translating and adapting measures across cultural contexts, and this study reflects well the best practices for developing a relevant survey tool for use in the four intended countries (44). For instance, bilingual researchers from each of the four cultural perspectives, as well as public health practitioners working in the chronic disease prevention context in each country were involved in the development of the questions, response options, translations, and reliability testing. Despite steps that the research team took to minimize mis-translation, the meaning of each question and response option becomes one layer removed from its original, intended meaning after translation. Next steps for informing further adaptation of the survey tool should include validity testing among chronic disease prevention practitioners in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States, ideally in representative samples (45).

There was low prevalence (N <5) for many response options and the items with low prevalence varied by country. According to Sim and Wright, low prevalence has stifling effects on Cohen's kappa coefficients, but inflating effects on percentage agreement (46). Low prevalence likely contributed to the low kappa coefficients and comparatively higher percentage agreement found in this study. A larger sample of practitioners across all four countries with more diversity of experiences may improve the variability of responses and the accuracy of reliability findings. Response items with low prevalence of endorsements may also reflect response items that are less applicable to practitioners' experiences in that particular country. Use of this survey tool in a larger, randomly selected sample of chronic disease practitioners in each country would clarify this conjecture.

This study responds well to a U.S. federal report that called for additional research focused on the experiences and perspectives of key stakeholders in evidence-based intervention delivery, in order to better facilitate the sustainability of interventions (47). The questions within this survey tool reflect critical contextual factors based on the literature, qualitative interviews of public health practitioners, and expert review (2, 5, 6). This survey tool allows researchers to proceed with research on the D&I of EBCDP interventions on a more global scale than was previously available. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind that used common methods across four countries. The research team had particular trouble recruiting retest respondents in Brazil due to significant political unrest that affected public health practitioners at the time of the request (39, 40). This contributed to the longer duration between test and retest and the smaller sample from Brazil compared with the other three countries. Additionally, his survey tool demonstrated lower reliability of responses among practitioners from Brazil and China compared with those from Australia and the United States. Lastly, a convenience sampling approach was carried out in some of the countries to recruit chronic disease prevention practitioners serving local or regional jurisdictions. Such a sampling method introduces potential selection bias and is unlikely to produce representative samples of all chronic disease prevention practitioners in each country. However, the intention of the present study was not to test hypotheses or provide prevalence estimates, which would have required using methods to address sampling error (46). Acknowledging these limitations of the sampling approach, the researcher team ensured that the selected sample included practitioners from various regions of each country, and provided distributions of all survey responses as well as demographic characteristics of the sample.

This survey tool allows cross-country data collection that can contribute toward an improved understanding of the contextual factors that public health practitioners in Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States face in their daily chronic disease prevention work. This understanding is necessary for the creation of multi-level strategies and policies that promote evidence-based decision-making and effective prevention of chronic diseases on a global scale.

This study was carried out in accordance with the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki with informed consent from all subjects. After reading the electronic informed consent document, subjects indicated their consent by selecting a radial button at the bottom of the informed consent document that read, I consent to participate in this research study. Additional written documentation of consent was waived and the protocol was approved by The University of Melbourne Human Ethics Committee, Pontifica Universidade Catolica do Parana Research Ethics Committee, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Human Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health and Social Science, and Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board. Reasons for waived written documentation of consent: Electronic documentation of informed consent was deemed sufficient for this study because of the non-sensitive nature of the questions and the participants' locations in four different countries. The following groups agreed on this decision: The University of Melbourne Human Ethics Committee, Pontifica Universidade Catolica do Parana Research Ethics Committee, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Human Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health and Social Science, and Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board.

EB contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and drafting of the full manuscript. XY and AdR contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the Statistical Analyses. KS and RB contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and drafting of the Discussion. ZW, PS, TP, RA, and RR contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (1R21CA179932-01A1).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Adeyi O, Smith O, Robles S. Public Policy and the Challenge of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases. Washington, DC. (2007). Available online at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPH/Resources/PublicPolicyandNCDsWorldBank2007FullReport.pdf

2. Allen P, Sequeira S, Jacob RR, Hino AA, Stamatakis KA, Harris JK, et al. Promoting state health department evidence-based cancer and chronic disease prevention: a multi-phase dissemination study with a cluster randomized trial component. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:141. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-141

3. Gibbert WS, Keating SM, Jacobs JA, Dodson E, Baker E, Diem G, et al. Training the workforce in evidence-based public health: an evaluation of impact among US and international practitioners. Prev Chronic Dis. (2013) 10:E148. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130120

4. Dreisinger M, Leet TL, Baker EA, Gillespie KN, Haas B, Brownson RC. Improving the public health workforce: evaluation of a training course to enhance evidence-based decision making. J Public Heal Manag Pr. (2008) 14:138–43. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000311891.73078.50

5. Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, Anderson L, Moore L, Petticrew M, et al. Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: intervention design and implementation plan. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-121

6. Jacobs JA, Dodson EA, Baker EA, Deshpande AD, Brownson RC. Barriers to evidence-based decision making in public health: a national survey of chronic disease practitioners. Public Health Rep. (2010) 125:736–42. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500516

7. Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Green LW. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annu Rev Public Health. (2018) 39:3.1–3.27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth

8. Dobbins M, Hanna SE, Ciliska D, Manske S, Cameron R, Mercer SL, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of knowledge translation and exchange strategies. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-61

9. Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Brouwers M, Wakefield P. Information seeking for making evidence- informed decisions: a social network analysis on the staff of a public health department in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-118

10. McMichael C, Waters E, Volmink J. Evidence-based public health: what does it offer developing countries? J Public Health. (2005) 27:215–21. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi024

11. Alwan A, Maclean DR, Riley LM, d'Espaignet ET, Mathers CD, Stevens GA, et al. Monitoring and surveillance of chronic non-communicable diseases: progress and capacity in high-burden countries. Lancet. (2010) 376:1861–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61853-3

12. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. (2011) 377:1438–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0

13. Chor KH, Wisdom JP, Olin SC, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM. Measures for predictors of innovation adoption. Adm Policy Ment Heal. (2015) 42:545–73. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0551-7

14. Ibrahim S, Sidani S. Fidelity of intervention implementation: a review of instruments. Health. (2015) 7:1687–95. doi: 10.4236/health.2015.712183

15. Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SY. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. (2008) 65:379–436. doi: 10.1177/1077558708317802

16. Arnson C, Sotero P. Brazil as a Regional Power: Views from the Hemisphere. Washington, DC. (2010). Available online at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/brazil-regional-power-views-the-hemisphere

18. Limb M. Living with the giants. Time. 2005. Available online at: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1051243,00.html

19. Louden R. Great+power. The World We Want. United States of America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2007).

21. Cuijpers P, de Graaf I, Bohlmeijer E. Adapting and disseminating effective public health interventions in another country: towards a systematic approach. Eur J Public Heal. (2005) 15:166–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki124

22. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles. (2014). Available online at: http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/en/#U (accessed August 8, 2017).

23. Lacerda RA, Egry EY, da Fonseca RM, Lopes NA, Nunes BK, Batista Ade O, et al. [Evidence-based practices published in Brazil: identification and analysis studies about human health prevention]. Rev Esc Enferm USP. (2012) 46:1237–47. doi: 10.1590/S0080-62342012000500028

24. Carneiro M, Silva-Rosa T. The use of scientific knowledge in the decision making process of environmental public policies in Brazil. J Sci Commun. (2011) 10:A03. doi: 10.22323/2.10010203

25. Glasgow RE, Marcus AC, Bull SS, Wilson KM. Disseminating effective cancer screening interventions. Cancer. (2004) 101 (Suppl. 5):1230–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20509

26. Mangham L, Hanson K. Scaling up in international health: what are the key issues? Heal Policy Plan. (2010) 25:85–96. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp066

27. Brownson RC, Colditz G, Proctor E. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2012).

28. Kerner J. Integrating science with service in cancer control: closing the gap between discovery and delivery. In: Elwood M, Sutcliffe S, editors. Cancer Control. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2010). p. 81–100.

29. Kerner J, Rimer B, Emmons K. Introduction to the special section on dissemination: dissemination research and research dissemination: how can we close the gap? Heal Psychol. (2005) 24:443–6. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.443

30. Dreisinger ML, Boland EM, Filler CD, Baker EA, Hessel AS, Brownson RC. Contextual factors influencing readiness for dissemination of obesity prevention programs and policies. Heal Educ Res. (2011) 27:292–306. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr063

31. Brownson RC, Ballew P, Brown KL, Elliott MB, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, et al. The effect of disseminating evidence-based interventions that promote physical activity to health departments. Am J Public Health. (2007) 97:1900–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090399

32. Jacobs JA, Clayton PF, Dove C, Funchess T, Jones E, Perveen G, et al. A survey tool for measuring evidence-based decision making capacity in public health agencies. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:57. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-57

33. Leeman J, Teal R, Jernigan J, Reed JH, Farris R, Ammerman A. What evidence and support do state-level public health practitioners need to address obesity prevention. Am J Heal Promot. (2014) 28:189–96. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120518-QUAL-266

34. Harris JK, Allen P, Jacob RR, Elliott L, Brownson RC. Information-seeking among chronic disease prevention staff in state health departments: use of academic journals. Prev Chronic Dis. (2014) 11:E138. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140201

35. Erwin PC, Harris JK, Smith C, Leep CJ, Duggan K, Brownson RC. Evidence-based public health practice among program managers in local public health departments. J Public Heal Manag Pr. (2014) 20:472–80. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000027.Evidence-based

36. Kohatsu ND, Robinson JG, Torner JC. Evidence-based public health. Am J Prev Med. (2004) 27:417–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.019

37. NACCHO. Quality Improvement. (2015). Available online at: https://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/performance-improvement/quality-improvement (accessed July 7, 2017).

38. Dunn G. Design and analysis of reliability studies: the statistical evaluation of measurement errors. Stat Med. (1992) 1:123–57.

39. Angelo C. Brazil's scientists battle to escape 20-year funding freeze. Nature. (2016) 539:480. doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.21014

40. Tollefson J. Political upheaval threatens Brazil's environmental protections. Nature. (2016) 539:147–8. doi: 10.1038/539147a

41. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. (1977) 33:159–74.

42. Mcgraw K, Wong S. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. (1996) 1:30–46.

44. Tanzer NK, Sim CQ. Adapting instruments for use in multiple languages and cultures: a review of the ITC guidelines for test adaptations. Eur J Psychol Assess. (1999) 15:258–69.

45. Cheung FM, Cheung SF. Measuring personality and values across cultures: imported versus indigenous measures measuring personality and values across cultures: imported versus. Online Readings Psychol Cult. (2003) 4:1–12. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1042

46. Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. (2005) 85:257–68. doi: 10.1093/ptj/85.3.257

47. Council NAMH. The Road Ahead: Research Partnerships to Transform Services. Bethesda, MD (2006). Available online at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/advisory-boards-and-groups/namhc/reports/road-ahead_33869.pdf

Keywords: chronic disease, reliability, evidence-based practice, implementation, international health

Citation: Budd EL, Ying X, Stamatakis KA, deRuyter AJ, Wang Z, Sung P, Pettman T, Armstrong R, Reis R and Brownson RC (2019) Developing a Survey Tool to Assess Implementation of Evidence-Based Chronic Disease Prevention in Public Health Settings Across Four Countries. Front. Public Health 7:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00152

Received: 26 December 2017; Accepted: 24 May 2019;

Published: 11 June 2019.

Edited by:

Marcelo Demarzo, Federal University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Iffat Elbarazi, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesCopyright © 2019 Budd, Ying, Stamatakis, deRuyter, Wang, Sung, Pettman, Armstrong, Reis and Brownson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth L. Budd, ZWJ1ZGRAdW9yZWdvbi5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.