- 1The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Menzies Centre for Health Policy, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3O'Brien Institute of Public Health, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Electronic or digital monitoring systems could promote the visibility of health promotion and disease prevention programs by providing new tools to support the collection, analysis, and reporting of data. In clinical settings however, the benefits of e-monitoring of service delivery remain contested. While there are some examples of e-monitoring systems improving patient outcomes, the smooth introduction into clinical practice has not occurred. Expected efficiencies have not been realized. The restructuring of team work has been problematic. Most particularly, knowledge from research has not advanced sufficiently because the meaning of e-monitoring has not been well theorized in the first place. As enthusiasm for e-monitoring in health promotion grows, it behooves us to ensure that health promotion practice learns from these insights. We outline the history of program monitoring in health promotion and the development of large-scale e-monitoring systems to track policy and program delivery. We interrogate how these technologies can be understood, noticing how they inevitably elevate some parts of practice over others. We suggest that progress in e-monitoring research and development could benefit from the insights and methods of improvement science (the science that underpins how practitioners attempt to solve problems and promote quality) as conceptually distinct from implementation science (the science of getting particular evidence-based programs into practice). To fully appreciate whether e-monitoring of program implementation will act as an aid or barrier to health promotion practice we canvass a wide range of theoretical perspectives. We illustrate how different theories draw attention to different aspects of the role of e-monitoring, and its impact on practice.

Introduction

The air-conditioning unit in the portable office shudders, then dies. It's 6pm and 40°C. The health promotion practitioner groans but doesn't look up from her computer. She's rushing to record today's work before the end-of-month deadline for her supervisor, located 200kms away. While the documentation system loads, she shuffles in her bag, through health pamphlets and educational aids, to locate the participant satisfaction evaluations from today's health fair. Clicking through drop-down lists across multiple screens, she inputs the scores. She then tallies and enters the number of people who registered for her nutrition newsletter. Logging out, she creates a reminder in her phone to follow-up with the cancer council about next week's smoking cessation program. Before leaving she handwrites a sticky-note for her colleague: “Low turnout–Hot! Probably won't meet our targets this month. PS. The aircon is dead – again :(”1

Background

The growing sophistication of digital technologies has generated wide interest among the public health practice sector for monitoring the delivery of health-promoting services and policies. Governments and non-government organizations have invested in digital technologies in the form of digital monitoring systems to track and oversee the quality and delivery of health promotion services—primarily evidence-based policies and programs (1, 2). Digital monitoring systems are able to collect, record, analyse and communicate real-time data about program and policy implementation, for multiple stakeholders located across vast distances (3).

Despite the promise of these systems to improve communication and practice, there are growing examples of failed digital monitoring systems from both clinical and health promotion settings (2, 4–6). Digital monitoring technologies in the clinical sector, e.g., electronic patient records, promised to improve service delivery, lower costs, and improve health, however, this promise has not been fully realized. Some systems have failed to produce, or even worsened, health outcomes (4, 5). Others have floundered when faced with the complex day-to-day intricacies of practice (2), or failed to maintain relevance in response to program shifts (6). This is despite many billions of dollars of investment in the design and roll-out of digital monitoring systems (7).

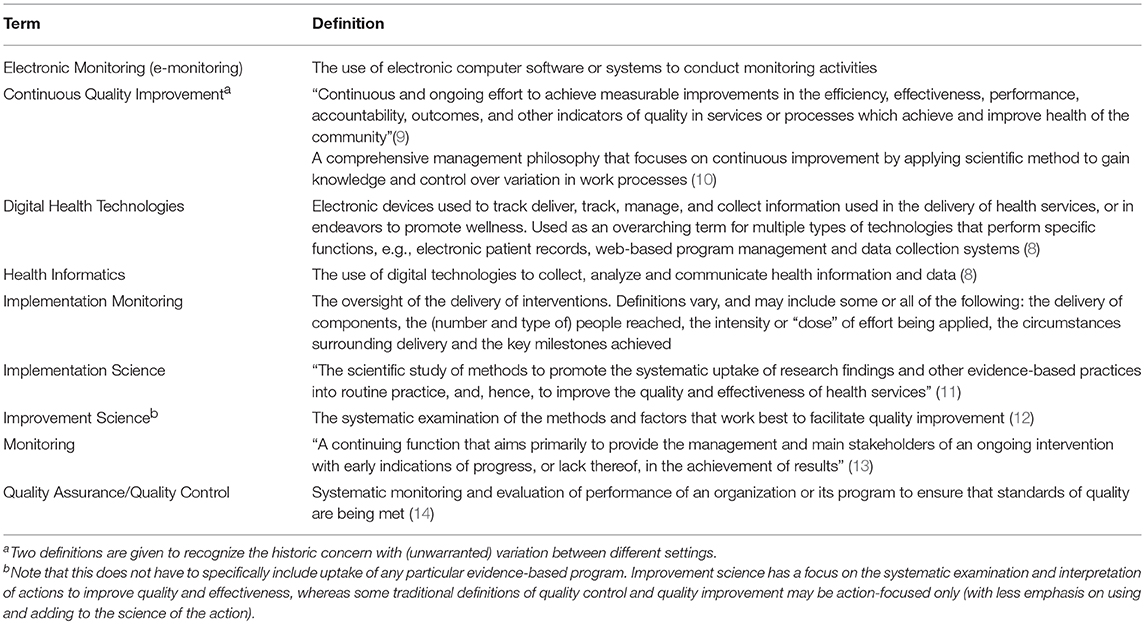

Nevertheless, the use of e-monitoring systems to oversee the implementation and delivery of health promotion programs is growing. The opening scenario of this paper will be common place to many readers who are already using such e-monitoring systems, or who may have developed their own digital systems for tracking the delivery and reach of programs and activities. These technologies can be classified as “health informatics,” a type of digital health technology to which electronic patient records are also a member (8) (see Table 1 for a glossary of terms used throughout this article). While electronic patient records monitor the delivery of healthcare to individuals, in the context of health promotion, electronic monitoring systems (hereafter referred to as “e-monitoring”) are used to track the delivery of preventive health programs, services, and activities to populations and settings, for example, communities, schools, or work places. However, information about the design, use, and impact of these systems has received little attention in the academic literature. As enthusiasm for e-monitoring systems grows, it behooves the field of health promotion to consider the phenomenological and epistemological questions about the use of digital technologies that have arisen in other sectors (8). For example, how do e-monitoring systems change the actions and relationships of practitioners? How are concepts of population health and health promotion challenged or reinforced through the design of e-monitoring systems and the data they capture? What are the implications for knowledge and power dynamics between communities, practitioners, and policy-makers? The purpose of this paper is to consider how e-monitoring technologies might impact the field of health promotion, and to suggest areas for future research. We do so by (1) providing examples of how key e-monitoring systems have developed and are currently used in health promotion practice, (2) reviewing the role of monitoring in health promotion, (3) examining whether e-monitoring systems might facilitate or hinder the act of monitoring, and (4) anticipating and articulating different theoretical lenses we may use to detect the intended and unintended impact of e-monitoring.

Examples of E-Monitoring Systems in Health Promotion Practice

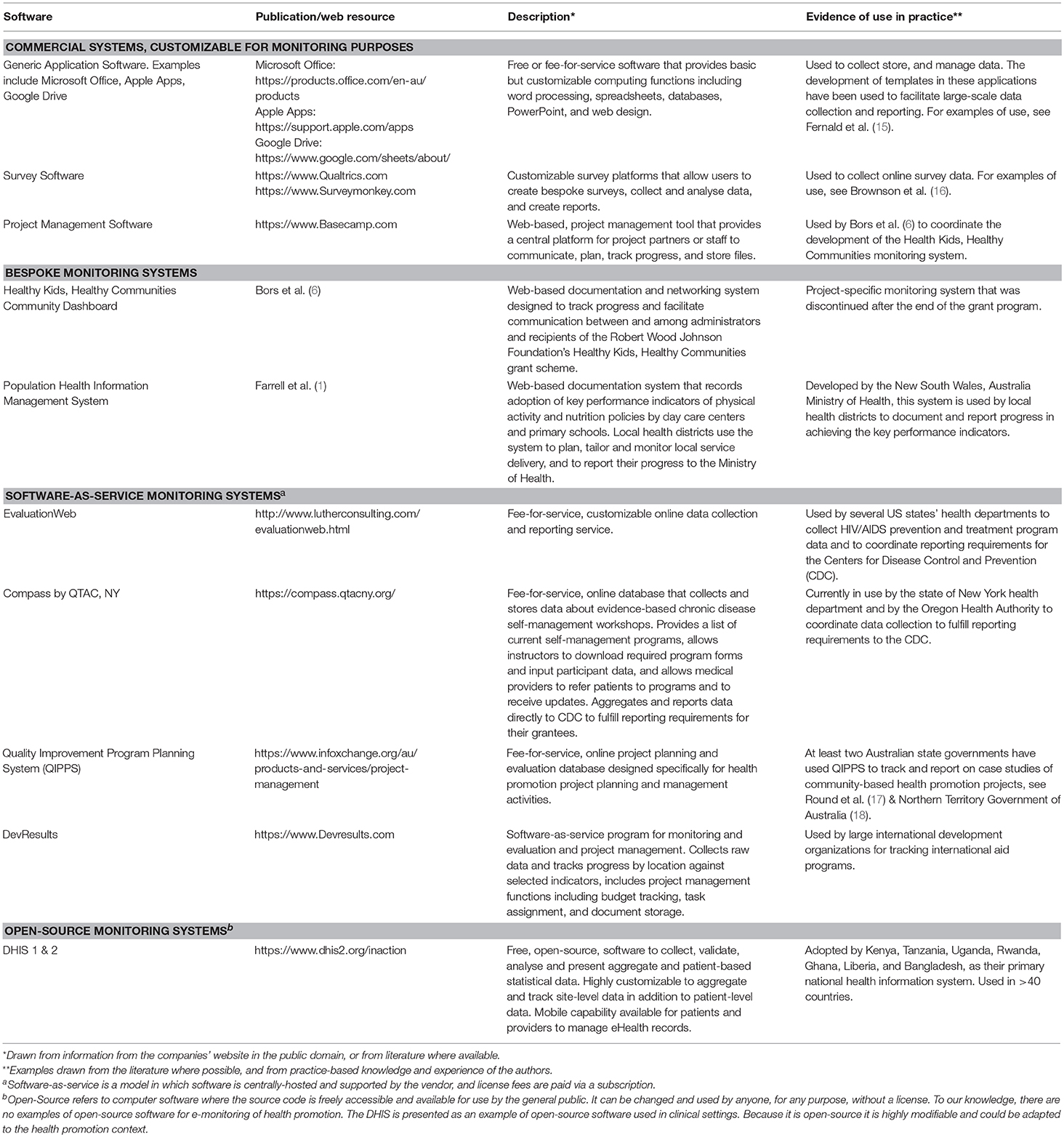

The earliest application of e-monitoring systems to monitor the delivery of health promotion programs and activities used generic software applications—e.g., word processors, spreadsheets and database software. Significant resources were spent in developing bespoke templates and protocols using these applications to collect monitoring data across sites and to train users (15). In Table 2, we provide examples of types of e-monitoring systems that are currently in use in the health promotion context.

Table 2. Examples of software systems in use to support e-monitoring of health promotion implementation.

Overtime, there was a push to streamline data collection and reporting into online data-management systems funded in part by health promotion infrastructure, e.g., governments and large organizations (1, 2). Commercial software companies began to offer adaptable data management systems capable of data analysis, project management, and real-time reporting functions. The advent of open-source software gave rise to free software systems that can be customized by local computer scientists to fit local needs for health monitoring. Both commercial and open-source systems are regularly used by health promotion researchers and practitioners to collect and present data about reach and facilitate workflow and collaboration between stakeholders (6, 16).

Despite the increased sophistication of software tools and their use in health promotion, few are sufficiently described in the academic literature. This is particularly true of bespoke systems that are developed for internal use. Often, software is created, used and abandoned or morphed into new systems without a record of the purpose it served, the lessons learned from its use, or the reasons for its failure (19). For example, the Program Evaluation and Monitoring System (PEMS) developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was meant to facilitate monitoring and assessment of the national HIV/AIDS prevention program in the United States (2). PEMs was meant to standardize reporting about HIV/AIDS counseling interventions and client details (e.g., risk behaviors and service use) delivered by local agencies across the USA. The burden of data entry, however, met with strong resistance from community organizations (20), and despite the expense dedicated to its development, PEMS never fully launched. The reasons for this, however, are not described in the literature.

Information about the development, use, success and failure of e-monitoring systems is needed to guide practitioners who wish to develop or purchase software to facilitate monitoring. Lyon et al. (21), recognized there was a gap between commercially-developed health software, and academic research on the topic. They developed a methodology for evaluating “measurement feedback systems,” or digital systems that routinely monitor outcomes in the health service sector. This methodology seeks to bridge commercial computer industries and academics by providing a tool with which researchers can identify and evaluate the capabilities of different computer monitoring systems for use in monitoring clinical outcomes. A similar but adapted methodology is needed in health promotion.

One example of e-monitoring in health promotion is illustrated by Brennan et al. (22) who developed a web-based computer system to monitor the activities of 49 funded community partnerships across the United States. They developed a typology of implementation that weighted the dose of intervention delivery to reflect the scale of reach, quality of implementation, and the potential impact of interventions undertaken across the communities. The utility of the e-monitoring system among users, however, was not as beneficial as it was to researchers, and it was disbanded after the end of the grant program (6). This highlights one of the key problems in the design of e-monitoring systems for health promotion: what role is e-monitoring expected to play in practice, and whose needs does it meet? To answer, we must consider what monitoring is, and what it is intended to do.

The Role of Program Monitoring in Health Promotion

Throughout the history of health promotion, monitoring activities and their outcomes has been part of practitioners' day-to-day practice. In some cases, years before clinicians were being asked to engage in evidence-based practice (23), health promotion practitioners were doing needs-based planning and designing logic-models for interventions (24). They were designing evaluations of process (e.g., reach, implementation, satisfaction and quality) (24, 25), assessing short term effects (impact evaluation) and achievement of long term goals (outcome evaluation). The ability of practitioners to plan, track and adjust their approach to practice was enshrined as a professional competency (26–28). Programs were monitored, targets of change (i.e., risk factors) were monitored, and even some of the behind-the-scenes work of practitioners in capacity building and the creation of inter-organizational collaborations came to be measured, though not as part of routine surveillance (29). As outcome evaluations of programs accumulated, meta-syntheses produced recommendations for best practice (30) as well as impetus to design monitoring systems to ensure effective programs were being implemented with fidelity, and reaching their intended audience (31).

The emphasis on monitoring fidelity, however, highlights a perennial tension that has existed throughout health promotions' history between “top-down” vs. “bottom-up” approaches to best practice (32). Top-down approaches, led by policy makers, identify best practice through research and then devise ways to diffuse, facilitate and incentivize the faithful delivery of best practice programs by practitioners. Bottom-up approaches assume that the best approaches to achieving health gains are discovered through the trial-and-error learning methods of practice now enshrined in models like the “plan-do-study-act” cycles (33). While many scholars saw the inevitability and even the benefit of this tension (34), they also foresaw that increased monitoring could exaggerate it. This would happen when one side (usually the top-down) developed stronger monitoring capacity than the other, and prioritized measuring phenomena seen as antithetical to, or not sufficiently representative of, what local practice might wish to achieve (35, 36).

Ottoson (37) has argued that top-down approaches to health promotion are heavily influenced by knowledge utilization theory and particular types of transfer theories which use fidelity of form as the criterion for success. In other words, with top-down approaches (and monitoring systems designed to support this), ideally the program or policy is unchanged by context. By contrast a bottom-up approach takes a more political and social understanding of change, where adaptation to context is a driver of success (37). Hence monitoring systems would have to accommodate (indeed encourage) the recording of diversity in practice. Expressed in the terminology of complexity, with bottom-up approaches, the agents in the system are viewed as problem solvers with power and decision making abilities that are seen to appropriately eclipse pre-determined or standardized solutions. By contrast, top-down approaches see the health promotion “system” as complicated -not complex- and its various parts expected to be faithfully reproduced.

In the real world, there are probably no such absolutes. But the insights are helpful for navigating current debates and distinctions between implementation science and improvement science (38, 39). Implementation is the science of getting particular evidence-based programs into practice (11); it tends to focus on the faithful replication of core components of programs (38). By contrast, improvement is the science that underpins how practitioners attempt to solve problems and promote quality (12). Improvement science is about sensitizing practitioners to discrepancies between “what is” and “what should be” and building strategies of action to meet desired goals (39). “What should be” can include more faithful adoption of evidence-based programs, but it can also extend to other activities, such as the restructuring of organizational culture to create more opportunities to reflect on performance (40).

The current day distinction between implementation science and improvement science is reminiscent of earlier-day distinction made by Stephenson and Weil (41) between systems of practice which rely on the replication of “dependent capability” (people working on familiar problems in familiar contexts) in contrast to practice systems which foster “independent capability” (ability to deal with unfamiliar problems in unfamiliar contexts). The former fits with implementation science. The latter aligns with improvement science. Add to this now the real-time ability of e-monitoring systems to privilege one type of practice process over the other, with fast collating monitoring systems that amplify differences in approach. Health promotion is thus left to ponder the question of what type of knowledge generation do we wish to advance and therefore, capture and enshrine in the design of subsequent e-monitoring systems? One narrowed to measuring the transfer and impact of particular programs only? Or one that recognizes that, at the local level, there may be a diversity of actions and innovations, some of which worth capturing and developing further?

How Might E-Monitoring Systems Enhance or Impede the Purpose of “Monitoring”?

A clear advantage of e-monitoring systems is that they potentially offer health promotion increased visibility at high bureaucratic levels, in a health sector currently dominated by clinical services. E-monitoring systems may bestow more authority to health promotion (1). Their use could signal a step out of the margin and into the mainstream. More than that, the systems provide high-level decision makers new information that potentially shines a favorable light on health promotion. Viewed alongside statistics on surgical waiting lists, or the growing size of the pharmaceutical costs, e-monitoring systems can tabulate the number of schools tackling obesity or the number of childcare centers with active play policies.

However, the design of an e-monitoring system will also determine what activities and practices get recognized. The competing priorities of different stakeholders raises potential concerns. Practitioners likely need different information to inform their immediate work (e.g., practical information about managing a task) than their managers at a government level (e.g., information about reach and target achievement). For example, in the opening scenario of this paper some of the most important pieces of information were written by hand on a sticky note—not entered into the e-monitoring system. The inherent complexity of health promotion in practice (42) requires monitoring systems that maintain confidence at high bureaucratic levels, while simultaneously enabling candid exchange of information at the practice-level. Indeed, practice-level information, e.g. uncertainties encountered, relationships formed and lost, frustrations, time wasted, could be (mistakenly) interpreted as indicative of goal slippage.

There is also a strong literature in capacity building for health promotion which indicates the importance of investing in generic activities that lead to multiple benefits (43). This means that the time a health promotion practitioner invests in building relationships with local organizations to deliver on nutrition targets could simultaneously be drawn-upon to address problems regarding tobacco or social inclusion issues. It follows that e-monitoring systems designed to entrench the tracking of high-priority health problems may ultimately crowd and compete with each other in a space where practitioners invest their time in ways that cannot be reliably attributed to any particular silo anyway (43).

The risk then is that e-monitoring systems meant only to track spending or count deliverables will likely fail to detect and fail to recognize key health promotion activities. In doing so, e-monitoring systems could not only reduce the value of health promotion work to a series of pre-defined, quantifiable measures, but also shift practice toward achieving these measures and away from continuous quality improvement and innovation. Maycock and Hall (36) caution against the development of a “tick-the-box mentality” in performance monitoring, with practitioners being “locked into and rewarded for current behavior patterns rather than creatively looking for alternative methods of improving outcomes” (p. 60). This statement marks the difference between passive performance monitoring and active processes of continuous quality improvement (CQI). In CQI, practitioners use the data reflexively to interrogate their work and innovate, hence reshaping the nature of their practice. Program delivery tracking and target assessment can still occur, but hopefully in a way that will not counteract more broadly focused CQI processes.

It is not a limitation of e-monitoring systems that they preference the collection and reporting of quantifiable, “tick box” indicators. It is simply a characteristic, and one that continues to change as technology increasingly enables the collation and visual representation of data. But no matter how well-designed, an e-monitoring system is simply a tool that facilitates the collection, management, and communication of data. Like any other tool, its optimal utility is achieved only when its design is appropriately matched to both task and user, and its function is clear. The design of the various e-monitoring systems described in Table 1 likely reflect their original purposes; the use of these systems will naturally pull practice toward some activities more than others. The actual application of these systems will differ in practice, depending on how and for what the user uses them. So while the design of e-monitoring is critical, of primary importance is articulating the purpose the act of e-monitoring is intended to perform.

How Theory Answers the Question: Will E-Monitoring Stifle or Enhance Practice?

Theory underlies “all human endeavors,” including endeavors of quality improvement (44). Yet often, the theories that underlie improvement efforts are not explicitly stated and go unrecognized. Articulating the theory that underlies an improvement effort enables us to uncover contradictory assumptions or incoherent logic in a program of action (44). Therefore, it is necessary to explicitly state the how e-monitoring is intended to facilitate improvement.

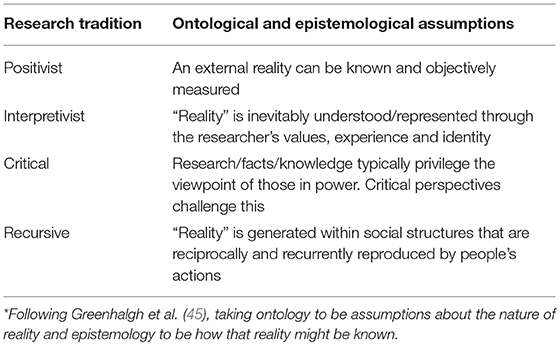

Previous scholars have illustrated the importance of making explicit the theoretical paradigm that underpin research processes used to investigate the act of e-monitoring. For example, work by Greenhalgh and colleagues illustrates how different types of knowledge about EPRs were generated via the application of different research paradigms (see Table 3) (45). This field is of interest to health promotion as the EPR can be thought of as the clinical analog of a health promotion program record. It records descriptive data about the patient as well as what advice, services and procedures have been dispensed to the patient. During a landmark synthesis on EPR literature, Greenhalgh and colleagues classified previous studies according to nine meta-narratives, each stemming from different historical and philosophical roots. The results reflected a wide range in how EPR research had been conceptualized, conducted, and ultimately, informed the current direction of EPR use and subsequent research. Of particular interest is their idea that the EPR studies reflected a tension between two framings (45). In one framing, technology is considered to have inherent properties that will perform certain tasks and improve processes and outcomes in more or less predictable ways across different settings. In the other, technology has a social meaning derived from the context of how it is used in practice. The important implication is that the ability to understand the range of impacts that e-monitoring can have on practice will depend on the research paradigm(s) used to detect it.

Table 3. Different philosophical research traditions observed to underpin electronic patient record research*.

Ultimately, it is through the use of theory that we may answer the question posited in our title: How will we know if e-monitoring of policy and program implementation stifles or enhances practice? In short, the answer depends on how we theorize what practice is and how a particular e-monitoring system's logic-of-action then fits with practice. In other words, we must articulate the mechanisms by which e-monitoring is intended to bring about change and improve practice so that assumptions can be verified, and the relationship between the act of e-monitoring and its intended outcome(s) can be tested.

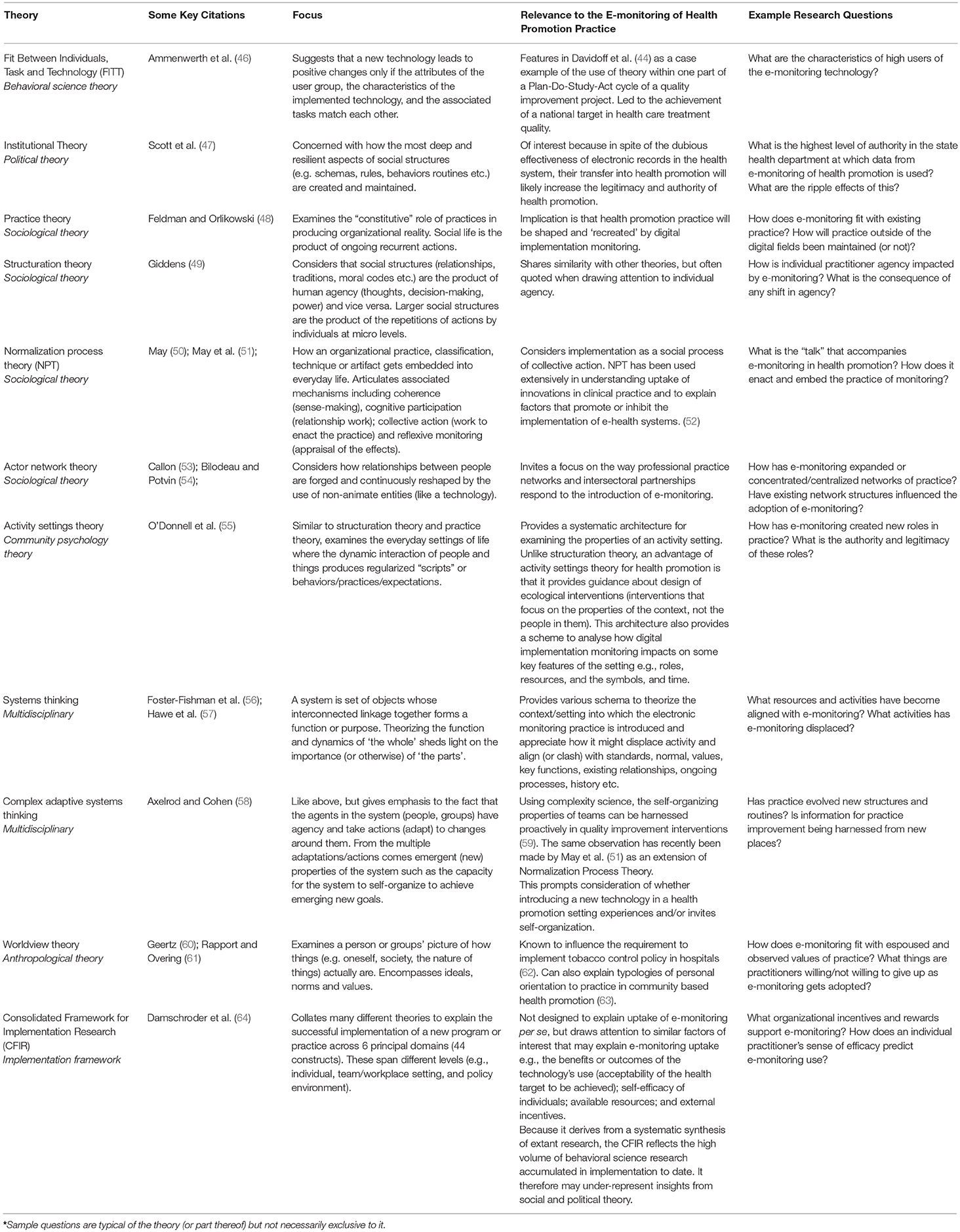

In Table 4 we illustrate some key theories we think are relevant for determining what we might glean about the act of e-monitoring. Note these theories concern the act of e-monitoring itself, not the programs or policies being monitored. Each theory challenges what the act of e-monitoring means, and in what ways it may impact practice. For example, Worldview Theory would invite consideration of what the e-monitoring system asks a practitioner to do, and whether this clashes with core practice values. Patterson and colleagues used Worldview theory to show how no-smoking policies in hospitals are stymied by the security staff who were meant to enforce them when these staff were unwilling to go against a higher order value of protecting the “downtime” (and private smoking behaviors) of nurses and doctors whom they held with the highest regard (62). In the health promotion context, an e-monitoring system which embeds siloed practices aimed at particular “risk factors” might not be well used if it clashes with more traditional “bottom up” practice values.

On the more ecological side, Activity Settings Theory is about the dynamics of settings—spaces where people come together and carry out particular regularized actions (55). Activity Settings Theory invites an analysis of the act of e-monitoring in terms of whether it enriches, reconfigures, or strips the practice setting in terms of professional roles and resources (informational, relational, material, emotional, affirmational), or sets up time constraints or dynamics that enhance or impede other important functions of the practice system. It also invites interrogation of the visible symbols introduced into the setting by e-monitoring and whether they align or clash with the existing cultural norms. So, on the up side, does a person's ability to troubleshoot the software (a role) create new relationships? On the downside, do computers, software and graphic displays create workplace hierarchies that were not there previously? Do signs of officialdom start to crowd out the welcome messiness of everyday interaction? The theories tune researchers into what to look for and how it might matter. If there are not enough meaningful roles to be shared among the people in a setting, then alienation ensues. Alternatively, too many roles per person (meaningful or not) leads to exhaustion (65). Understanding these dynamics potentially leads to interventions that can be more effective and sustainable. So, e-monitoring could be crafted to create a dynamic that moves workplace wellbeing and effectiveness forward, through the use of some particular theory.

Collectively, these theories invite research that expands the questions asked about new technologies—beyond questions about whether technologies improve a particular health outcome—to issues that may be more important to the long-term strength and sustainability of the field of health promotion. That is, how are digital technologies intended to improve and support best practice?

Concluding Remarks

The lure of e-monitoring is that a practitioner can capture, store, analyse and communicate data in real time across geographical settings at the click of a button. The advantages of such systems, however, must be weighed against potential disadvantages. The onus turns to researchers in partnership with practitioners to design innovative studies to fully illuminate the experience of e-monitoring of health promotion practice and the full insights of what is being learned. A researcher-policy maker-practitioner partnership is currently undertaking an ethnography of an e-monitoring technology being used to track childhood obesity prevention programs in New South Wales, Australia (66). Likewise, future studies might usefully locate themselves within particular theoretical perspectives so that knowledge and understanding can be more easily identified, interpreted, extended and/or revised. This is critical if insight from research on e-monitoring from one context is to be used in another. For example, if an innovation is theorized to be purely technical and tested using a positivist orientation only (e.g., does use of the technology lead to increased physical activity in schools?) then such research will not explain the immediate disuse of the technology once the research process is over [as was the experience of Bors et al. (6)]. Nor will such research provide insights to overcome social resistance to the use of the technology in another setting.

Indeed, by far the biggest threat (or opportunity) accompanying the increasing uptake of e-monitoring of implementation in health promotion is the imperative placed on us to articulate practice itself and how good practice will be defined, supported and recognized. The point of distinction is whether we conceptualize good practice as a context of discovery (i.e., improvement science), or simply a context of program or practice delivery (i.e., implementation science) (39, 40). In terms of e-monitoring, an implementation science perspective might encourage teams to adopt and use a particular system whereas an improvement science perspective might consider how to design or use such systems in ways that facilitate practitioners' agency to “re-invent” programs and processes for local use (67). This idea of practice as re-invention aligns with May's assertion that practitioners “seek to make implementation processes and contexts plastic: for to do one thing may involve changing many other things” (50).

We therefore invite more improvement-science-oriented research to give shape to knowledge which reciprocally improves both e-monitoring and practice to foster inbuilt capability and innovation. We encourage developers of e-monitoring systems to share their learnings with the field, and to integrate programs of research into the roll out and implementation of e-monitoring systems. Finally, we join other colleagues in calling for future research to make clear the theoretical underpinning of research questions and approaches, and to consider a broad array of user perspectives into the impact and value of e-monitoring systems. Some time ago, health promotion researchers urged recognition that dissemination is a two-way process, insisting that knowledge from practice be given more consideration alongside getting knowledge into practice (68). Advancement of practice may not fully occur if e-monitoring acts to privilege one knowledge source more than the other. Fortunately, health promotion has never had a moment in history with better infrastructure to address this challenge, to represent what practice is, what practice can achieve, and how it can evolve meaningfully in the digital age.

Author Contributions

KC and PH co-conceptualized this manuscript. KC led the initial draft and PH co-wrote sections of the paper. Both contributed to the final drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) through its Partnership Centre grant scheme (grant GNT9100001). NSW Health, ACT Health, the Australian Government Department of Health, the Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia and the HCF Research Foundation have contributed funds to support this work as part of the NHMRC Partnership Centre grant scheme. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the individual authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC or funding partners.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank members of the Monitoring Health Promotion Practice group who read and commented on earlier drafts of this manuscript. This includes Victoria Loblay, Sisse Groen, Andrew Milat, Amanda Green, Jo Mitchell, Sarah Thackaway, Christine Innes-Hughes, Lina Persson, and Mandy Williams. We also wish to thank Priscilla Boucher and Nikki Percival for drawing our attention to the QIPPS health promotion system referenced in Table 2.

Footnotes

1. ^This illustrative story is a composite narrative drawn from practice experience.

References

1. Farrell L, Lloyd B, Matthews R, Bravo A, Wiggers J, Rissel C. Applying a performance monitoring framework to increase reach and adoption of children's healthy eating and physical activity programs. Public Health Res Pract. (2014) 25:e2511408. doi: 10.17061/phrp2511408

2. Thomas C, Smith B, Wright-DeAguero L. The program evaluation and monitoring system: a key source of data for monitoring evidence-based HIV prevention program processes and outcomes. AIDS Educ Prev. (2006) 18(4 Suppl. A):74–80. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.74

3. Lumpkin JR, Magnuson JA. History and Significance if Information Systems in Public Health. Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. London: Springer (2013). p. 19–36.

4. Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, Anandan C, Cresswell K, Bokun T, et al. The impact of ehealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med. (2011) 8:e1000387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000387

5. Payne TH. Electronic health records and patient safety: should we be discouraged? BMJ Qual Saf. (2015) 24:239–40. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004039

6. Bors PA, Kemner A, Fulton J, Stachecki J, Brennan LK. HKHC community dashboard: design, development, and function of a web-based performance monitoring system. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. (2015) 21(Suppl. 3):S36–44. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000207

7. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Payment and Registration Report for the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program. Electronic Health Records Incentive Program (2017). Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/March2017_Summary-Report.pdf

8. Lupton D. Critical perspectives on digital health technologies. Sociol Compass (2014) 8:1315–97. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12226

9. Riley WJ, Moran JW, Corso LC, Beitsch LM, Bialek R, Cofsky A. Defining quality improvement in public health. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. (2010) 16:5–7. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181bedb49

10. Tindill B, Stewart D. Integration of total quality and quality assurance. In: Al-Assaf A, Schmele J, editors. The Textbook Of Total Quality in Healthcare. Delray Beach, FL: St. Lucie Press (1993). p. 209–20.

11. Eccles M, Mittman B. Welcome to implementation science. Implement. Sci. (2006) 1:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

12. The Health Foundation. Improvement Science. The Health Foundation (2011). Available online at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/ImprovementScience.pdf

13. United Nations Development Program Evaluation Office. Handbook on Monitoring and Evaluating for Results (2002). Available online at: http://web.undp.org/evaluation/handbook/documents/english/pme-handbook.pdf (Accessed June 01, 2018).

14. Lesneski C, Massie S, Randolph G. Continuous quality improvement in U.S. public health organizations: moving beyond quality assurance. In: Burlington M, editor. Continuous Quality Improvement in Health Care. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Publishers Incz (2013). p. 453–80.

15. Fernald D, Harris A, Deaton EA, Weister V, Pray S, Baumann C, et al. A standardized reporting system for assessment of diverse public health programs. Prev Chronic Dis. (2012) 9:120004. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120004

16. Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health (2013) 103:1693–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301165

17. Round R, Marshall B, Horton K. Planning For Effective Health Promotion Evaluation. Victorian government department of human services. (2005).

18. Northern Territory Government of Australia. Health Promotion (2017). Available online at: https://health.nt.gov.au/professionals/health-promotion/health-promotion

19. Komakech G. A Conceptual Model For A Programme Monitoring and Evaluation Information System. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University (2013).

20. Majic S. Protest by Other Means? Sex Workers, Social Movement Evolution and the Political Possibilities Of Nonprofit Service Provision. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University (2010).

21. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Melvin A, Boyd M, Nicodimos S, Liu FF, et al. Health information technologies—academic and commercial evaluation (HIT-ACE) methodology: description and application to clinical feedback systems. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:128. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0495-2

22. Brennan LK, Kemner AL, Donaldson K, Brownson RC. Evaluating the implementation and impact of policy, practice, and environmental changes to prevent childhood obesity in 49 diverse communities. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2015) 21 (Suppl. 3):S121–34. doi: 10.1097/phh.0000000000000256

23. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. J Am Med Assoc. (1992) 268:2420–5.

24. Hawe P, Degeling D, Hall J. Evaluating Health Promotion: A Health Worker's Guide. Sydney, NSW: MacLennan & Petty (1990).

25. Flay BR. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Prev Med. (1986) 15:451–74. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90024-1

26. Pan-Canadian Committee on Health Promoter Competencies. Pan-Canadian Health Promoter Competencies. Health Promotion Canada (2015). Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/52cb0336e4b0e90fb28b6088/t/56cc604707eaa037daaf6247/1456234567617/2015-HPComp-Statements.pdf (Accessed Feb 3, 2017).

27. Australian Health Promotion Association. Core Competencies For Health Promotion Practitioners. Australian Health Promotion Association (2009). Available online at: http://healthpromotionscholarshipswa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/core-competencies-for-hp-practitioners.pdf (Accessed Feb 3, 2017).

28. Barry MM, Battel-Kirt B, Davidson H, Dempsey C, Parish R, Schipperen M, et al. The CompHP Project Handbooks. International Union for Health Promotion and Education (2012). Available online at: http://www.fundadeps.org/recursos/documentos/450/CompHP_Project_Handbooks.pdf. (Accessed June 6, 2017).

29. Wickizer TM, Von Korff M, Cheadle A, Maeser J, Wagner EH, Pearson D, et al. Activating communities for health promotion: a process evaluation method. Am J Public Health (1993) 83:561–7.

30. Mullen PD, Green LW, Persinger GS. Clinical trials of patient education for chronic conditions: a comparative meta-analysis of intervention types. Prev Med. (1985) 14:753–81.

31. Catford J. Advancing the 'science of delivery' of health promotion: not just the 'science of discovery'. Health Promt Int. (2009) 24:1–5. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap003

32. Laverack G, Labonte R. A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Policy Plan (2000) 15:255–62. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.255

33. Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. (2007) 82:735–9. doi: 10.4065/82.6.735

34. Hubbard LA, Ottoson JM. When a bottom-up innovation meets itself as a top-down policy. Sci. Commun. (1997) 19:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1075547097019001003

35. Kahan B, Goodstadt M. Continuous quality improvement and health promotion: can CQI lead to better outcomes? Health Promt Int. (1999) 14 83–91. doi: 10.1093/heapro/14.1.83

36. Maycock B, Hall SE. The quality management and health promotion practice nexus. Promt Educ. (2003) 10:58–63. doi: 10.1177/175797590301000201

37. Ottoson JM. Knowledge-for-action theories in evaluation: knowledge utilization, diffusion, implementation, transfer, and translation. New Dir Eval. (2009) 2009:7–20. doi: 10.1002/ev.310

38. Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. (2015) 3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

39. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Parry GJ. Seven propositions of the science of improvement: exploring foundations. Qual Manag Health Care. (2013) 22:170–86. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31829a6a15

40. Leviton LC. Reconciling complexity and classification in quality improvement research. BMJ Qual Saf. (2011) 20(Suppl. 1):i28–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046375

41. Stephenson J, Weil L. Quality In Learning: A Capability Approach In Higher Education. London: Kogan Page (1992).

42. Tremblay M-C, Richard L. Complexity: a potential paradigm for a health promotion discipline. Health Promt Int. (2014) 29:378–88. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar054

43. Hawe P, King L, Noort M, Gifford SM, Lloyd B. Working invisibly: health workers talk about capacity-building in health promotion. Health Promt Int. (1998) 13:285–95. doi: 10.1093/heapro/13.4.285

44. Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. (2015) 24:228–38. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627

45. Greenhalgh T, Potts HWW, Wong G, Bark P, Swinglehurst D. Tensions and paradoxes in electronic patient record research: a systematic literature review using the meta-narrative method. Milbank Q. (2009) 87:729–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00578.x

46. Ammenwerth E, Iller C, Mahler C. IT-adoption and the interaction of task, technology and individuals: a fit framework and a case study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. (2006) 6:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-3

47. Scott RW, Ruef M, Mendel P, Caronna CA. Insititutional Change And Healthcare Organizations: From Professional Dominance To Managed Care. Chicago, IL; London: The University of Chicago Press (2000).

48. Feldman MS, Orlikowski WJ. Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Org Sci. (2011) 22:1121–367. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0612

50. May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:18. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-18

51. May C, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:141. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3

52. Mair FS, May C, O'Donnell C, Finch T, Sullivan F, Murray E. Factors that promote or inhibit the implementation of e-health systems: an explanatory systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. (2012) 90:357–64. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099424

53. Callon M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. Soc Rev. (1984) 32: 196–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x

54. Bilodeau A, Potvin L. Unpacking complexity in public health interventions with the actor-network theory. Health Promt Int. (2016) 33:173–81. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daw062

55. O'Donnell CR, Tharp RG, Wilson K. Activity settings as the unit of analysis: a theoretical basis for community intervention and development. Am J Community Psychol. (1993) 21:501–20. doi: 10.1007/bf00942157

56. Foster-Fishman PG, Nowell B, Yang H. Putting the system back into systems change: a framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am J Community Psychol. (2007) 39:197–215. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0

57. Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. (2009) 43:267–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9

59. Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Taylor BS, McCannon CJ, Lindberg C, Lester RT. How complexity science can inform scale-up and spread in health care: understanding the role of self-organization in variation across local contexts. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 93:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.040

60. Geertz C. Ethos, World View, and the Analysis of Sacred Symbols. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc (1973). p. 126–41.

61. Rapport N, Overing J. Social And Cultural Anthropology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge (2000).

62. Patterson PB, Hawe P, Clarke P, Krause C, van Dijk M, Penman Y, et al. The worldview of hospital security staff: implications for health promotion policy implementation. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. (2009) 38:336–57. doi: 10.1177/0891241608318012

63. Riley T, Hawe P. A typology of practice narratives during the implementation of a preventive, community intervention trial. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:80. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-80

64. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

65. Barker RG, Gump PV. Big School, Small School: High School Size And Student Behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (1964).

66. Conte KP, Groen S, Loblay V, Green A, Milat A, Persson L, et al. Dynamics behind the scale up of evidence-based obesity prevention: protocol for a multi-site case study of an electronic implementation monitoring system in health promotion practice. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:146. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0686-5

67. Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA (2003) 289:1969–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969

Keywords: implementation, health information technology, health promotion, quality improvement, accountability, innovation, program monitoring

Citation: Conte KP and Hawe P (2018) Will E-Monitoring of Policy and Program Implementation Stifle or Enhance Practice? How Would We Know? Front. Public Health 6:243. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00243

Received: 01 June 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018;

Published: 11 September 2018.

Edited by:

Shane Andrew Thomas, Shenzhen International Primary Healthcare Research Institute, ChinaReviewed by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaArmin D. Weinberg, Baylor College of Medicine, United States

Copyright © 2018 Conte and Hawe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kathleen P. Conte, a2F0aGxlZW4uY29udGVAc3lkbmV5LmVkdS5hdQ==

Kathleen P. Conte

Kathleen P. Conte Penelope Hawe

Penelope Hawe