- 1School of Health Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 2Affiliated Mental Health Center, Tongji Medical College of Huazhong, University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

Objective: To explore the attitudes and factors in seeking professional psychological help among a Chinese community-dwelling population in order to promote positive help-seeking behaviors and better utilization of mental health services.

Methods: Using system and simple random sampling with Kish selection table methods, 912 community-dwelling residents were included in this study and asked about their attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, depression symptoms, family function, depression literacy, help-seeking intention, and stigma.

Results: Scores on the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale (ATSPPH-SF) indicated a neutral attitude toward openness to seeking treatment for psychological problems and a negative attitude toward the value and need to seek treatment with a negative total score. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that gender, age, social support (employment status and family function), depression literacy, stigma, and help-seeking intention are significantly associated with attitude toward seeking professional psychological help.

Conclusion: The overall attitude toward seeking professional psychological help is not optimistic, thus, more efforts are needed to enhance understanding. Effective interventions including mental health education, training of mental health professionals, and popularizing the use of mental health services are essential, especially for the at-risk population.

Introduction

Mental disorders have become a serious problem worldwide, with over 300 million (4.4%) and 264 million (3.6%) people experiencing depression and anxiety disorders respectively (1). A recent large-scale survey in China showed that the lifetime prevalence of depression and anxiety was 6.9 and 7.6%, respectively (2). Mental disorders can cause high rates of disability and mortality as well as increase the burdens of other diseases and related health care costs (3–5) and suicide is the most serious consequence (6, 7). A majority of individuals (76–85%) with mental disorders receive no treatment in low- and middle-income countries compared with 35–50% in high-income countries (8). A low rate of help-seeking behaviors (9–11) and delayed help-seeking (12) are barriers to receiving timely and effective treatment for persons with mental disorders. Professional help-seeking (e.g. from mental health professionals, physicians) is more effective in the prevention and management of mental health problems and protects individuals against suicide (13, 14).

Currently, the outlook is not optimistic regarding the use of professional help-seeking behaviors for mental health issues in many countries, especially China (15, 16). In Canada, one in 10 young people had consulted professionals for their problems (17). In another study across four Chinese provinces, it was found that only 11 (7.3%) of the suicide decedents (151) and four (3.3%) of those who attempted (120) had previously sought psychological or medical treatment for psychological problems (18). A recent study indicated that 7.9% of participants with depressive symptoms had sought help from mental health professionals (MHPs) and 3.7% from general physicians (19).

Based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (20), attitude can indirectly influence help-seeking behavior via intention (21), and it is a precursor to help-seeking intention and actual help behaviors (22). Thus, improving help-seeking attitude is the first step in promoting further help-seeking behaviors.

Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help (ATSPPH) vary by geographic location. The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) of the USA conducted in 1990–1992 showed that one-third of respondents would definitely seek professional help (23). A study in Saudi Arabia (24) noted that 43.5% of participants would use professional assistance for serious emotional problems. In Europe, over 69% of survey participants had a more open attitude toward seeking professional help and approximately 50% recognized the value of professional help (25). In the Western Pacific region, participants had a poor attitude compared with results in the US and Europe (26). A 40-year review from 1968 to 2008 showed that the ATSPPH has become increasingly negative over time (27). In China, most research about help-seeking attitude has focused on college students (28–30). One study found that 40.4% of Chinese university students expressed willingness to seek help from a psychiatrist if they had suicidal ideation. And they preferred to seek informal social networks rather than professionals to solve their mental health issues (31). Currently, research about ATSPPH in the Chinese community-dwelling population is lacking.

Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help can be affected by various factors such as gender (32), age (25), educational level (33), marital status (34), work status (35); sociological and cultural factors such as culture prejudice (36), social support (37), mental health literacy (38); individual factors such as stigma related to mental problems (39), help-seeking intention (40), the experience of mental problems (17), knowledge about the role of health professionals (41), and personality traits (42). Based on the above findings, this study aimed to further explore significant correlates in the Chinese community-dwelling population which have been neglected in previous studies.

Materials and Methods

Sample Size and Sample Design

This study was a population-based, cross-sectional survey conducted between January 2017 and December 2017 in Wuhan, a major city in central China (43). A stratified random sampling method was applied in the whole sampling process, which was divided into three stages to select target communities, households, and individuals. First, 20 communities from seven central districts of Wuhan were selected using an Excel generate random number table. Second, a systematic sampling method was used by coding all households in each community with a random number from an Excel generated random number table, and identifying 50 target households in each community according to the sampling interval K (the total number of households in the community divided by 50). Finally, in Kish selection table method, one of eight codes (A, B1, B2, C, D, E1, E2, F) was assigned to the target households; a family registration form (including name, age, gender, member number) was used to assign additional codes to individual family members. This allowed for the use of a Kish code for every household to determine the target individuals. This Kish selection table method is usually used to determine target individuals from every family in a household survey (44). A total of 1,000 questionnaires were distributed; 923 questionnaires were returned (response rate: 92.3%) and 912 questionnaires were valid (effective callback rate: 91.2%). Inclusion criteria were: minimum age of 15 years and able to read and write in Mandarin. Participants with severe somatic illness or other psychosis and related disorders, dementia, and mental impairment due to substance dependence were excluded.

Institutional Review Board of Wuhan University School of Medicine granted approval for this study. Based on the principle of voluntary participation and withdrawal from the study at any time, participants signed informed consent prior to participation. Privacy rights were protected by using coded anonymous questionnaires and the security of these questionnaires was maintained. Small gifts were provided in gratitude for an individual’s participation.

Measures

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Participants completed a general demographic questionnaire indicating their gender, age, religion, education level, parents’ and spouse’s education level, employment, and marital status.

Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale—Short Form (ATSPPH-SF)

The ATSPPH-SF was developed by Fischer and Farina (45), translated into Chinese in 2017 and revised for cultural applicability after communicating with the original authors. The original questionnaire was translated by two individuals, an assistant professor in mental health nursing with a doctoral degree and having expertise in mental health and concepts used in the scale and a doctoral student majoring in teaching the Chinese language. The researchers then compared and synthesized the differences and modifications in the two translations to develop a preliminary version of the scale. It was submitted for review to two experts who have been engaged in mental health research for 10 years. In addition, two individuals with no experience using the scale were invited separately to do back-translations. One was a nursing professor who is bilingual and has worked in an English-speaking country for at least 10 years and the other was a master’s student in English. The researchers compared the back-translation versions with the original scale, discussed and reviewed it with four translators to develop a Chinese version of the original scale.

The scale was used to measure participants’ ATSPPH and included two dimensions: openness to seeking professional help for emotional problems (items 1, 3, 5, 6, 7) with item scores ranging from zero (disagree) to three (agree); value and need in seeking professional help (items 2, 4, 8, 9, 10) with items scored in reverse (zero = agree and three = disagree). The total score of the scale ranges from zero to 30 with higher scores indicating a better help-seeking attitude. The cut-off score on the scale is greater than 20 points and for each dimension is greater than 10 points; otherwise, the attitude is deemed to be negative.

In the original study of college students, the short version of the scale demonstrated internal consistency ranging from 0.82 to 0.84, a one-month test–retest reliability of 0.80; and, a correlation of 0.87 with the longer scale (45). It had good validity and could distinguish whether they were willing to seek professional psychological help (46). In the current study, internal consistency was shown with a Cronbach’s α for the entire scale and the two subscales of 0.681, 0.714 and 0.657, respectively. The test-retest reliability was 0.895 for the entire scale, 0.781 for the openness scale and 0.827 for the value and need scale. The Chinese version of the ATSPPH-SF is suggested to be valid and reliable. The item content validity (I-CVI) was 0.833–1.000, and the scale content validity index (S-CVI) was 0.932. The result of exploratory factor analysis showed that the cumulative contribution rate of the two common factors was 45.346%, the correlation coefficient between each dimension and the total score of the scale was 0.755–0.772, and the correlation coefficient of the two dimensions was 0.167, both of which were statistically significant (P < 0.01). The KMO value was 0.783, Bartlett’s test χ2 = 1505.611, P < 0.01. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that each indicator fit well (χ2/df = 2.53, RMR = 0.035, RMSEA = 0.054, NFI = 0.927, CFI = 0.938) (47). Thus, the use of a two-factor analysis model in this study was found to be robust.

Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D scale (48) has 20 items with a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no or hardly) to 3 (almost always) (49), which is used to screen for participants’ weekly depressive symptoms. The total score ranges from zero to 60 with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.873.

Family APGAR Index

To measure an individual’s satisfaction with family functioning, the current study used the Family APGAR Index developed by Smilkstein (50). It consists of five items standing for Adaptation, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolution and uses a three-point Likert scoring from 0 (hardly ever) to 2 (almost always). The total score ranges from zero to 10 with higher scores indicating better family function. Good reliability was shown in this study with a Cronbach’s α of 0.889.

Depression Stigma Scale (DSS)

This scale was used to measure personal and public stigma toward depression (51) and had good reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.814. It consists of 18 items with two subscales: personal stigma (personal attitude on depression) and public stigma (attitudes toward others’ views on depression). Each subscale includes nine items using a five-point Likert scoring, which ranges from 4 (strongly agree) to 0 (strongly disagree). Total scores on each of the two subscales ranges from zero to 36 points with a higher score representing increased personal and public stigma.

Depression Specific Self-Management (DSSM) Scale

To measure the depressive knowledge of a community-dwelling population, the current study selected the first dimension of this scale: specific knowledge of depression (items one to four) (52). This scale uses a five-point Likert scoring with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression knowledge. The Cronbach’s α was 0.542 in the current study.

General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ)

The community residents’ help-seeking intention for psychological problems was measured by the GHSQ which includes informal and professional help-seeking sources (53). The latter was used to measure the professional help-seeking intention. It uses a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 7 (extremely likely) with higher scores indicating greater help-seeking intention. Reliability was good with a Cronbach’s α of 0.618.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze variables. Frequency, means, and standard deviations were used to describe participants’ characteristics and ATSPPH-SF scores. To better understand the difference in the ATSPPH between China and other different regions, independent sample t-tests were performed. Independent sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA tests were conducted to assess ATSPPH-SF scores with categorical variables. Pearson correlation analysis was to explore the relationship between continuous variables (e.g. age, family function, stigma, help-seeking intention, depressive symptoms, and depression knowledge) and help-seeking attitude. Variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) based on a one-way ANOVA test, independent sample t-test, and Pearson correlation analysis were entered into a multiple linear regression model, which was used to explore the significant correlates of help-seeking attitude. The multicollinearity was tested using SPSS when conducting the multiple linear regression analyses, which confirmed that there were no issues of multicollinearity (VIF ranged from 1.016 to 1.670). The pattern of missing data per variable was missing completely at random (Little’s MACR test: Chi-square = 51.947, df = 44, P = 0.192). Respondents with four or more missing values on the included variables were excluded. When a questionnaire lacked ≤4 item responses, the mean score of non-missing items was used in place of the scores of the missing items. Results were considered statistically significant with a level of P < 0.05.

Results

Sample Characteristics

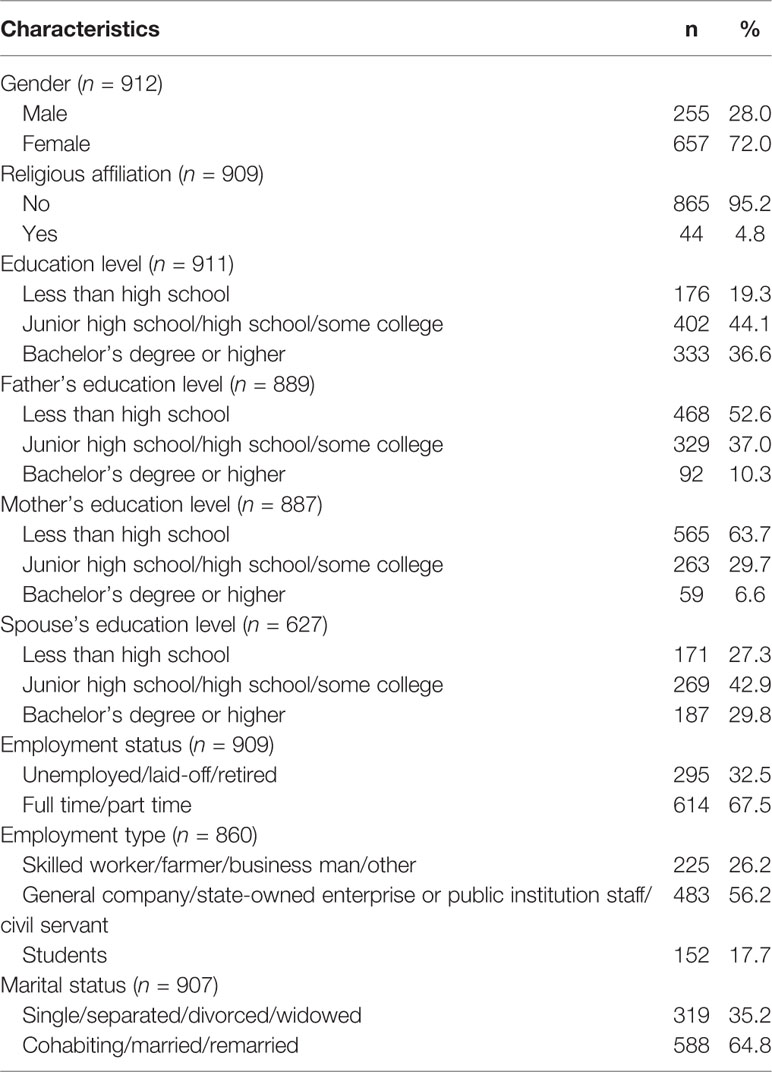

There were 912 participants included: 255 were male (27.9%) and 657 were female (72.1%). The average age was 38.66 ± 17.34 years (see Table 1). In addition, the score of the Family APGAR Index ranged from 0 to 10 (Mean = 7.20, SD = 3.01), indicating participants had good family function on average. The score of personal stigma ranged from 2 to 36 (M = 19.22, SD = 5.04) and public stigma ranged from 5 to 36 (M = 21.94, SD = 5.02). The score of depression knowledge ranged from 4 to 20 (M = 14.14, SD = 2.35) and the score of help-seeking intention from professionals ranged from 9 to 63 (M = 22.09, SD = 13.97).

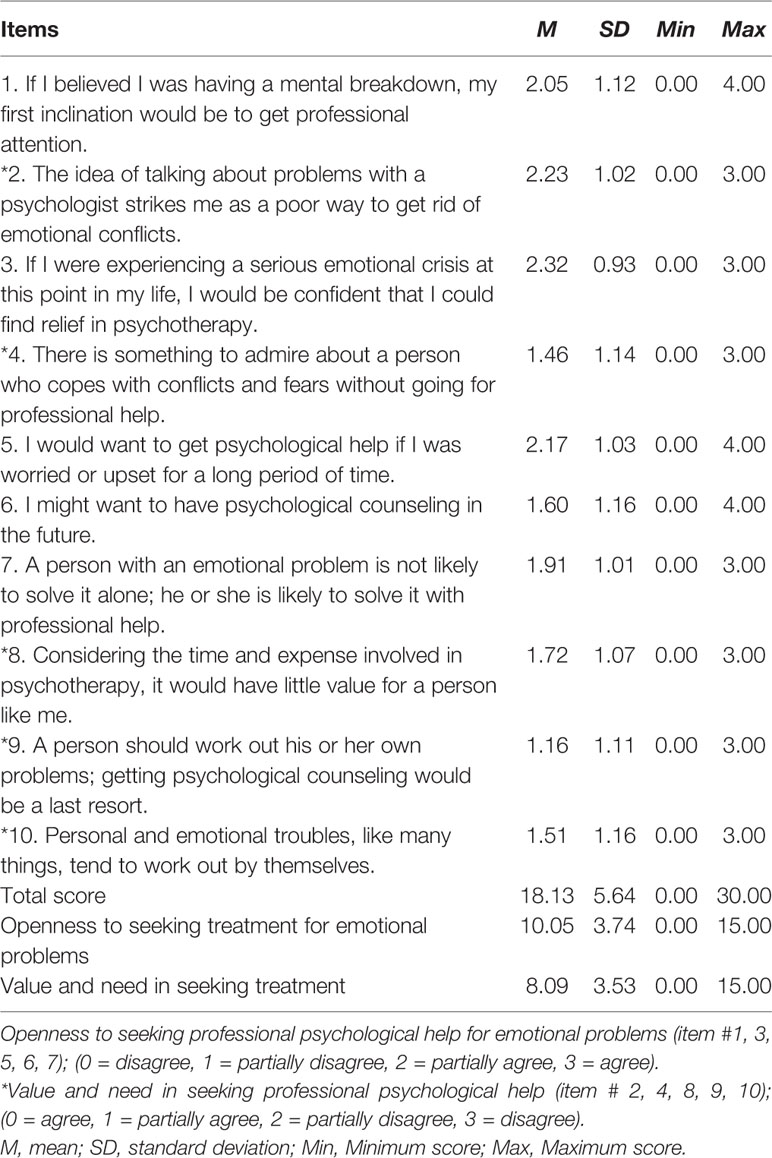

Scores of the ATSPPH-SF

The total score on the ATSPPH-SF was less than 20 (M = 18.13, SD = 5.63) indicating that overall attitude was negative. The score on openness was near the critical value of 10 (M = 10.05, SD = 3.74) indicating a neutral attitude and the score on value and need was less than 10 points (M = 8.09, SD = 3.53) indicating a negative attitude. Participants were in greatest agreement on the third item “If I were experiencing a serious emotional crisis at this point in my life, I would be confident that I could find relief in psychotherapy” having the highest score (M = 2.32, SD = 0.93) and with the ninth item “Each person should solve their own problem and not seek psychological consultation unless absolutely necessary” having the lowest score (M = 1.46, SD = 1.14) on reverse scoring. Items of least agreement among the participants were the sixth item “I might want to have psychological counseling in the future” (M = 1.60, SD = 1.16) and the second item “The idea of talking about problems with a psychologist strikes me as a poor way to get rid of emotional conflicts” (M = 2.23, SD = 1.02) (see Table 2).

Table 2 Scores on the attitude toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form (ATSPPH-SF).

An investigation of ATSPPH in western Pacific regions showed that a lower score was found in the Philippines (M = 16.83, SD = 4.13, t = 2.759, P = 0.006), but there were no significant differences in Fiji (M = 18.47, SD = 7.76, t = −0.644, P = 0.520) and Cambodia (M = 18.69, SD = 3.47, t = −1.182, P = 0.238) (26).There were also lower average scores (M = 17.4, SD = 5.5, t = 3.602, P < 0.001) in Europe including Germany (M = 17.2, SD = 4.4, t = 4.405, P < 0.001), Hungary (M = 13.9, SD = 4.3, t = 18.555, P < 0.001), Ireland (M = 18.4, SD = 5.4, t = −1.070, P < 0.001), and Portugal (M = 20.0, SD = 5.7, t = −7.222, P < 0.001) which had a higher score than the results of this study (M = 18.13, SD = 5.63) (25). Higher scores were also found in the USA (M = 20.45, SD = 5.51, t = −5.226, P < 0.001) (54).

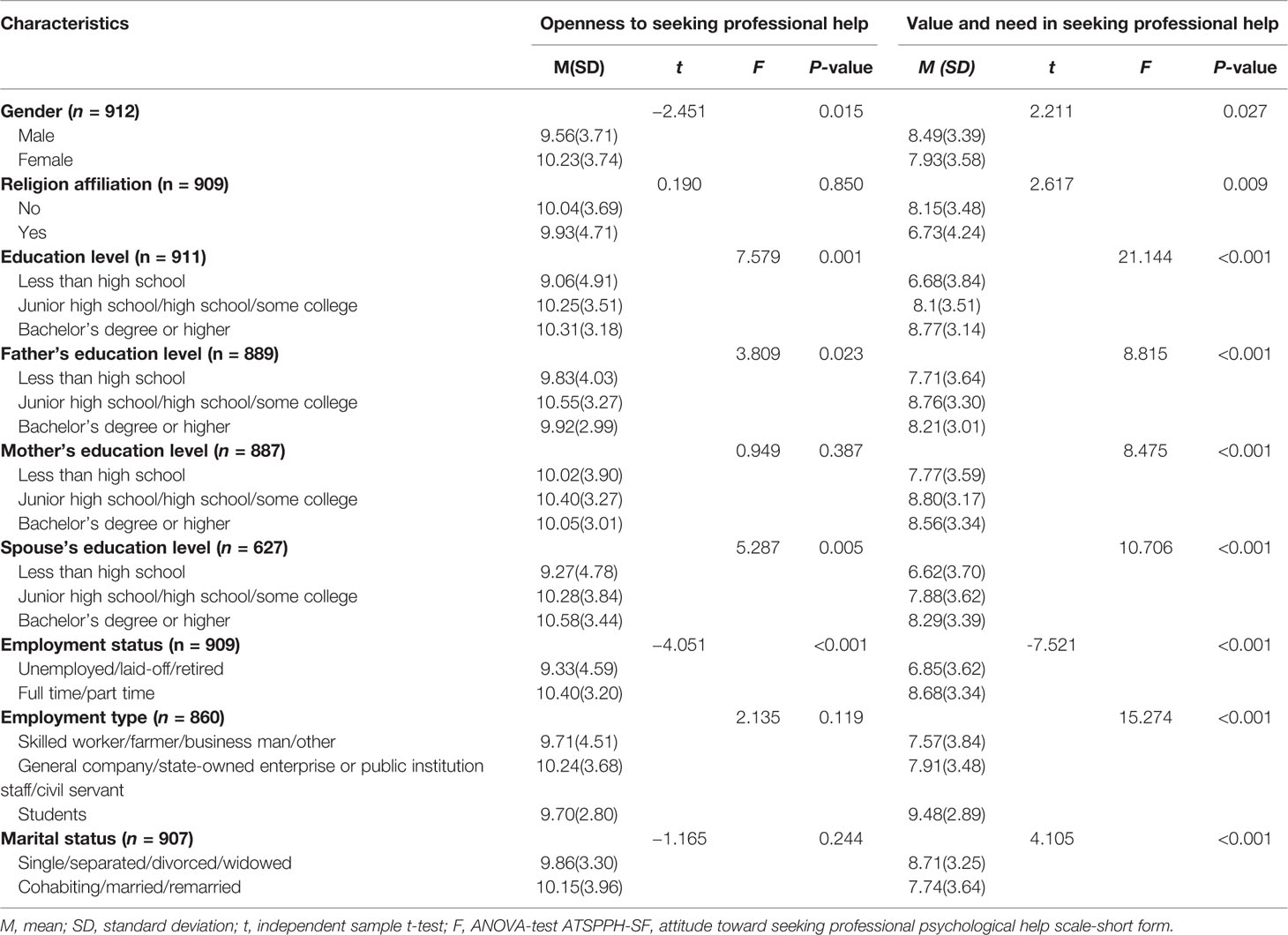

Differences in the ATSPPH Scores According to Participants’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The results of ANOVA-test and t-test indicated that there were significant differences in gender, education level, father’s and spouse’s education level, employment, and marital status related to openness to seeking professional psychological help. Gender, religion, education level, parents’ and spouses’ education level, employment, and marital status had statistically significant differences related to value and need in seeking professional help (see Table 3).

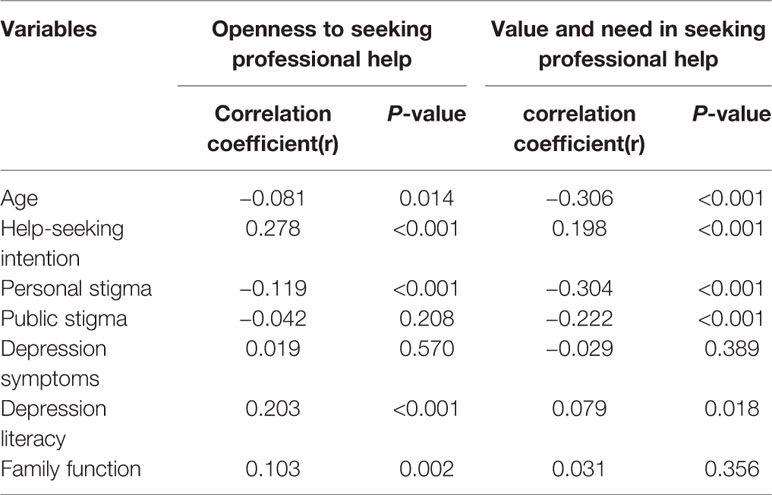

Pearson Correlation Analysis Between ATSPPH and Continuous Variables

Table 4 shows that age, family function, depression literacy, and help-seeking intention positively correlated to “openness” to help-seeking. Of these, age, depression literacy, and help-seeking intention were positively correlated to “value and need” of professional psychological help. In addition, personal stigma was negatively related to help-seeking attitude on “openness” and “value and need.” Public stigma was also negatively related to help-seeking attitude on “value and need” (see Table 4).

Table 4 Correlation between age, help-seeking intention, stigma, depressive symptoms, depression literacy, family function, and ATSPPH.

Influencing Factors on the ATSPPH

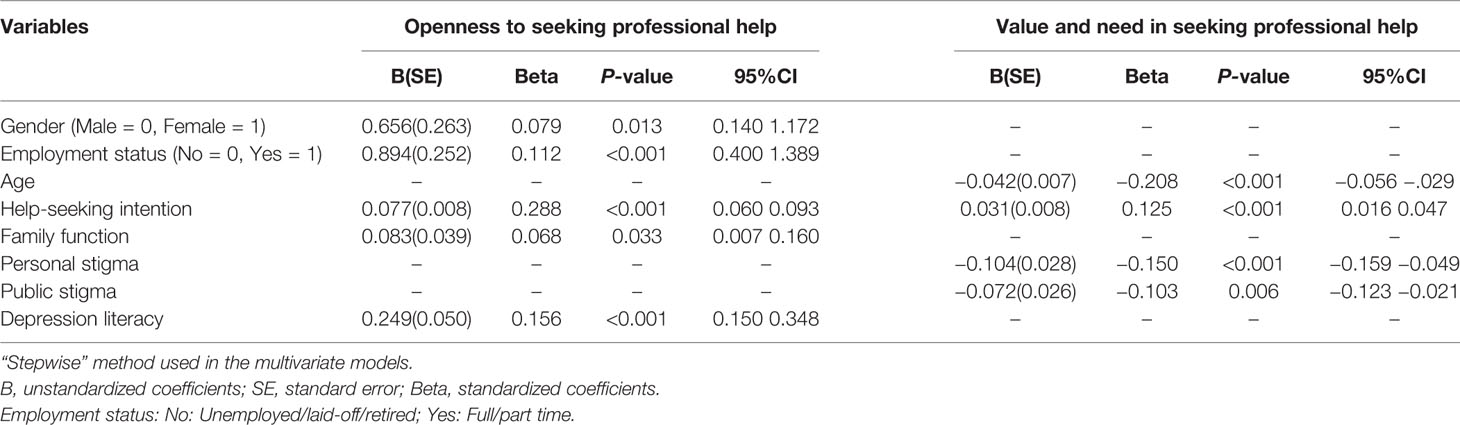

Two multiple linear regression models were both statistically significant, F openness = 30.616, P < 0.001, with a R-square value (R2) of 0.149; F valueandneed = 39.412, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.153. Results showed that participants who were female (Beta = 0.079; 95%CI: 0.140, 1.172), were employed (Beta = 0.112; 95%CI: 0.400, 1.389), had better family function (Beta = 0.068; 95%CI: 0.007, 0.160), as well as increased help-seeking intention (Beta = 0.288; 95%CI: 0.060, 0.093) and depression literacy (Beta = 0.156; 95%CI: 0.150, 0.348) were significantly associated with higher scores in openness to seeking professional help for emotional problems. Older participants (Beta = −0.208; 95%CI: −0.056, −0.029), those having personal (Beta = −0.150; 95%CI: −0.159, −0.049) and public stigma (Beta = −0.103; 95%CI: −0.123, −0.021) were significantly associated with lower “value and need in seeking professional help,” while those with increased help-seeking intention (Beta = 0.125; 95%CI: 0.016, 0.047) had a more positive attitude (see Table 5).

Table 5 Correlates of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help (ATSPPH) conducted by multiple linear regression.

Discussion

ATSPPH

The ATSPPH was negative in this Chinese community-dwelling population (M = 18.13, SD = 5.63). Compared with the findings in different regions, it can be seen that the ATSPPH in China is more positive than in the Philippines (M = 16.83, SD = 4.13) (26) and most European regions (M = 17.4, SD = 5.5) such as Germany (M = 17.2, SD = 4.4) and Hungary (M = 13.9, SD = 4.3) (25). However, there are still gaps, compared with the more positive help-seeking attitude in the USA (M = 20.45, SD = 5.51) (54) and Portugal (M = 20.0, SD = 5.7) (25), Thus, there is a need to focus on improving understanding of and attitudes regarding professional psychological support in China.

There are several reasons from a cultural, social, and individual point of view to explain this negative help-seeking attitude. Culturally, some Chinese perceive psychotherapy as an inefficient and impractical way of dealing with problems affected by traditional beliefs (55). They may be reluctant to discuss their emotions openly with others to save face (56). In addition, some Chinese believe mental illness is caused by emotional disharmony or by evil spirits (56). People who have cultural prejudice would link mental illness to personal shortcomings and reinforce their stigma (57, 58). Hence, they prefer to solve distress on their own by repressing their emotional problems instead of seeking help from others (32).

Socially, mental health literacy is low in the general population and the spread of psychological education is insufficient (59). For instance, some people regard their psychological distresses as normal and these distresses can go away (60). There is a lack of mental health services in China (61) and the number of qualified community MHPs is very low (62), especially in rural regions. There is evidence that one reason for not seeking help is that members of the community do not know where to go to seek professional help (32).

From the individual’s perspective, their ATSPPH may be affected by the severity and complexity of their psychological problems. People with less severe mental disorders are more likely to choose informal help (11); but unfortunately, those with severe mental disorders do not seek help due to a lack of insight (63). It is suggested that a negative perception of psychological professionals is also a barrier to seeking professional help (10), for instance, being skeptical about the effectiveness of psychological help or the competence of MHPs (64) or having had an unpleasant experience with professionals (63).

Factors Related to ATSPPH

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Participants in this study had an increasingly negative attitude toward value and need in seeking professional psychological help with increasing age. Older persons may tend to seek help from family or friends rather than professional resources (65). They are rich in life experience and more deeply influenced by Chinese culture (66), making them feel that they have abilities to solve problems and are not willing to seek help. This perspective contrasts with that of younger people who suffer from more mental problems caused by various stresses related to maladaptation, so their demand for professional psychological help is higher than that of older people (67, 68). Moreover, younger people easily obtain more information about mental health from school, the workplace, or the Internet, thus they have a better attitude toward the value of professional help (34).

Consistent with most studies, men had a more negative ATSPPH (32, 33, 69). Masculinity including masculine norms and alexithymia may limit men’s ability to express grief (69). They feel shamed talking about emotional problems (70) and fear damaging the ideal image of the male when seeking help from others (41). In addition, men have alternative solutions to alleviate pain such as alcohol, drugs, and aggressive behaviors (41). These explain why they do not actively seek professional help.

Social Support

This study found that people who have good social support (relative to employment status and good family function) have a better ATSPPH. There is evidence that employment status is positively associated with psychological openness (35). Individuals who are employed have more opportunities for communication and interaction with others in their work setting, could solve problems more effectively and have a greater sense of self-worth; thus, they are more open to seek mental health professionals when encountering psychological problems (35). In addition, having a source of income also provides financial support to facilitate help-seeking actions (26).

Good family function had a positive effect on help-seeking attitude. In China, family plays a vital role in providing affective support and psychological comfort (71, 72). Family members can offer advice and share guidelines on problem-solving (73) and decision making (74) and they are always the first source of help-seeking when a family member encounters emotional distress (19, 26, 65).

Depressive Literacy

Consistent with previous research, having greater depressive knowledge was significantly associated with a positive attitude toward professional help-seeking (26, 32, 36). People with greater knowledge may diminish the stigma related to mental disorders, and they are more willing to seek professional help according to their need (26, 33, 75).

Stigma and Help-Seeking Intention

Consistently, stigma was cited as a negative factor affecting professional psychological help-seeking attitude (10, 76, 77). On one hand, people with personal stigma may hide their thoughts to avoid addressing emotional problems, as they would feel uncomfortable, ashamed, and embarrassed to talk about these with professionals (67). Another issue is related to how the public labels individuals with mental disorders as “sick, neurotic,” so individuals are fearful of being laughed at and discriminated against when seeking professional psychological help (78).

Notably, a significant finding of this study revealed that increased help-seeking intention is positively associated with help-seeking attitude. As previously known, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) confirmed that the more positive an individual’s attitude, the stronger an individual’s intention would be (20). However, a confirmatory study found that changing a person’s intention can result in a change of attitude in turn (40), that is, the greater the intention, the better the attitude.

It is worth noting that the R-square values for the two regression models were both small. However, a low R-square value does not negate the importance of any significant variables (79). The theory of planned behavior (TPB) (20) suggests that attitudes can be affected by behavioral beliefs and attitudes can predict behaviors by indirectly affecting intentions. The theory of knowledge-attitude-practice (KAP) (80) espouses that knowledge can change one’s attitude. Based on these theories, this study explored the relationship between ATSPPH and help-seeking intention, stigma, social support, and depression literacy. And the results showed that these factors were significantly associated with ATSPPH though they might not account for more variance. This provides a reference for further exploration of help-seeking attitudes, intention, and behaviors in future research. Moreover, it can be seen that regression models in psycho-social studies (including the studies of help-seeking attitude) usually had small R-square values. For example, one study about the help-seeking attitude found that the factors accounted for 11.4% of the variance in the multiple regression model (81) and another study had an R-square value of 0.16 (82).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this research which derived from a large-scale survey. First, this is a cross-sectional survey, so a causal relationship between help-seeking attitude and its influencing factors cannot be drawn. Second, the use of self-rating scales focused on depressive symptoms, personal and public stigma related to depression, and help-seeing intention may result in bias as participants may respond in a socially desirable manner. Third, this study was completed in one city in central China, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other areas of the country. While this study identified statistically significant predictors for the ATSPPH score, the clinical implications and characteristics related to these findings should be considered due to the low beta coefficient values.

Conclusions and Implications

In general, the Chinese attitude toward seeking professional assistance with mental health issues is not positive. Positive factors affecting this attitude include being female, of a younger age, having social support and help-seeking intention, while the negative factor is stigma. More attention should be paid to vulnerable groups (e.g. older adults, males, and the unemployed).

Based on the current research findings, it is important to consider methods to promote better help-seeking attitudes in the general population by eliminating cultural bias and reducing stigma associated with mental health issues and educating the public about the importance of mental health. The focus of these efforts should be centered on older adults and males. Emphasis should be placed on the use of social media channels to spread relevant information to increase mental health literacy. Government programs focused on mental health education and services should be expanded to close the gap between urban and rural areas and increase accessibility to these programs for the community-dwelling population. In addition, there is a need to strengthen education and training of mental health professionals to promote greater trust between those who seek services and the providers.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article.

Ethics Statement

Institutional Review Board of Wuhan University School of Medicine granted approval for this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author Contributions

BY, XW and PC designed the study and wrote the research protocol. PC, XL, BY, XW, ZL and JR did the literature review, managed the field survey, quality control, and statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript draft. XW and BY contributed to the revisions in depth for the manuscript. ZL, XW, BY and JR supervised the survey and checked the data. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We appreciate the grant support provided by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1314600), Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education in China (20YJCZH204), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.71503192) and Wuhan Health and Family Planning Commission Research Fund (No. WX17B16).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks are given to Dr. Sharon R. Redding (EdD, RN, CNE) for assistance in editing. We also thank Dr. Edward Fischer for his permission to translate and undertake cultural adaptation of the ATSPPH-SF and for his assistance in this process.

References

1. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders (Global Health Estimates). (2017). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/ [Accessed November 10, 2019].

2. Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiat. (2019) 6(3):211–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

3. Boonstra N, Klaassen R, Sytema S, Marshall M, De Haan L, Wunderink L, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms–a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Schizophr Res (2012) 142(1-3):12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.017

4. Dell’Osso B, Glick ID, Baldwin DS, Altamura AC. Can long-term outcomes be improved by shortening the duration of untreated illness in psychiatric disorders? A conceptual framework. Psychopathology (2013) 46(1):14–21. doi: 10.1159/000338608

5. World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. (2013). https://www.afro.who.int/publications/mental-health-action-plan-2013-2020 [Accessed November 10, 2019].

6. Hawton K, Carolina CIC, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord (2013) 147(1-3):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

7. Li H, Luo X, Ke X, Dai Q, Zheng W, Zhang C, et al. Major depressive disorder and suicide risk among adult outpatients at several general hospitals in a Chinese Han population. PloS One (2017) 12(10):e0186143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186143

8. World Health Organization. Mental disorders. (2018). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders [Accessed November 10, 2019].

9. Brandstetter S, Dodoo-Schittko F, Speerforck S, Apfelbacher C, Grabe HJ, Jacobi F, et al. Trends in non-help-seeking for mental disorders in Germany between 1997-1999 and 2009-2012: a repeated cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2017) 52(8):1005–13. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1384-y

10. Savage H, Murray J, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Evans-Lacko S, Brown JS. Exploring professional help-seeking for mental disorders. Qual. Health Res (2016) 26(12):1662–73. doi: 10.1177/1049732315591483

11. Brown J, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry (2014) 14(1):275. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0275-y

12. Hui CLM, Tang JYM, Wong GHY, Chang WC, Chan SKW, Lee EHM, et al. Predictors of help-seeking duration in adult-onset psychosis in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2013) 48(11):1819–28. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0688-9

13. Reynders A, Kerkhof AJFM, Molenberghs G, Van Audenhove C. Attitudes and stigma in relation to help-seeking intentions for psychological problems in low and high suicide rate regions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2014) 49(2):231–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0745-4

14. Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust e-J. Adv Ment Health (2005) 4(3):218–51. doi: 10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

15. Bifftu BB, Takele WW, Guracho YD, Yehualashet FA. Depression and its help seeking behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community survey in Ethiopia. Depress Res Treat (2018) 2018:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2018/1592596

16. Chong SA, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Kwok KW, Subramaniam M. Where do people with mental disorders in Singapore go to for help? Ann Acad Med Singapore (2012) 41(4):154–60. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0153-x

17. Findlay LC, Sunderland A. Professional and informal mental health support reported by Canadians aged 15 to 24. Health Rep (2014) 25(12):3–11.

18. Tong Y, Phillips MR, Yin Y. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in individuals who die by suicide or attempt suicide in China based on independent structured diagnostic interviews with different informants. J Psychiatr Res (2018) 98:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.12.003

19. Fang S, Wang XQ, Yang BX, Liu XJ, Morris DL, Yu SH. Survey of Chinese persons managing depressive symptoms: help-seeking behaviours and their influencing factors. Compr Psychiatry (2019) 95:152127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152127

20. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec. (1991) 50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

21. Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help-seeking intentions for depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2009) 259(5):298–306. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0870-y

22. Hantzi A, Anagnostopoulos F, Alexiou E. Attitudes towards seeking psychological help: an integrative model based on contact, essentialist beliefs about mental illness, and stigma. J Clin Psychol Med Settings (2019) 26(2):142–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9573-8

23. Mojtabai R, Evans-Lacko S, Schomerus G, Thornicroft G. Attitudes toward mental help seeking as predictors of future help-seeking behavior and use of mental health treatments. Psychiatr Serv (2016) 67(6):650–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500164

24. Abolfotouh MA, Almutairi AF, Almutairi Z, Salam M, Alhashem A, Adlan AA, et al. Attitudes toward mental illness, mentally ill persons, and help-seeking among the Saudi public and sociodemographic correlates. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2019) 12:45–54. doi: 10.2147/prbm.s191676

25. Coppens E, van Audenhove C, Scheerder G, Arensman E, Coffey C, Costa S, et al. Public attitudes toward depression and help-seeking in four European countries baseline survey prior to the OSPI-Europe intervention. J Affect Disord (2013) 150(2):320–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.013

26. Ho GWK, Bressington D, Leung SF, Lam KKC, Leung AYM, Molassiotis A, et al. Depression literacy and health-seeking attitudes in the Western Pacific region: a mixed-methods study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2018) 53(10):1039–49. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1538-6

27. Mackenzie CS, Erickson J, Deane FP, Wright M. Changes in attitudes toward seeking mental health services: a 40-year cross-temporal meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev (2014) 34(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.001

28. Chang H. Depressive symptom manifestation and help-seeking among Chinese college students in Taiwan. Int J Psychol (2007) 42(3):200–6. doi: 10.1080/00207590600878665

29. Han J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Wu Y, Xue J, van Spijker BAJ. Development and pilot evaluation of an online psychoeducational program for suicide prevention among university students: a randomised controlled trial. Internet Interv. (2018) 12:111–20. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.11.002

30. Zhou Y, Lemmer G, Xu J, Rief W. Cross-cultural measurement invariance of scales assessing stigma and attitude to seeking professional psychological help. Front Psychol (2019) 10:1249. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01249

31. Han J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Ma J. Seeking professional help for suicidal ideation: a comparison between Chinese and Australian university students. Psychiatry Res (2018) 270:807–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.080

32. Yu Y, Liu ZW, Hu M, Liu HM, Yang JP, Zhou L, et al. Mental health help-seeking intentions and preferences of rural Chinese adults. PloS One (2015) 10(11):e0141889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141889

33. Roskar S, Bracic MF, Kolar U, Lekic K, Juricic NK, Grum AT, et al. Attitudes within the general population towards seeking professional help in cases of mental distress. Int J Soc Psychiatry (2017) 63(7):614–21. doi: 10.1177/0020764017724819

34. Picco L, Abdin E, Chong SA, Pang S, Shafie S, Chua BY, et al. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: factor structure and socio-demographic predictors. Front Psychol (2016) 7:547. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00547

35. Zalat MM, Mortada EM, El Seifi OS. Stigma and attitude of mental health help-seeking among a sample of working versus non-working Egyptian women. Community Ment Health J (2019) 55(3):519–26. doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0298-9

36. Waldmann T, Staiger T, Oexle N, Rüsch N. Mental health literacy and help-seeking among unemployed people with mental health problems. J Ment Health (2019) 1–7. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1581342

37. Santesteban-Echarri O, MacQueen G, Goldstein BI, Wang J, Kennedy SH, Bray S, et al. Family functioning in youth at-risk for serious mental illness. Compr Psychiatry (2018) 87:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.08.010

38. Wong F, Li J. Cultural influence on Shanghai Chinese people’s help-seeking for mental health problems: implications for social work practice. Brit. J Soc Work (2014) 44(4):868–85. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcs180

39. Amarasuriya SD, Jorm AF, Reavley NJ. Predicting intentions to seek help for depression among undergraduates in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry (2018) 18(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1700-4

40. Sussman R, Gifford R. Causality in the theory of planned behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull (2019) 45(6):920–33. doi: 10.1177/0146167218801363

41. Lynch L, Long M, Moorhead A. Young men, help-seeking, and mental health services: exploring barriers and solutions. Am J Mens. Health (2018) 12(1):138–49. doi: 10.1177/1557988315619469

42. Perenc L, Radochonski M. Psychological predictors of seeking help from mental health practitioners among a large sample of Polish young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2016) 13(11):1049. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111049

43. Yang F, Yang BX, Stone TE, Wang XQ, Zhou Y, Zhang J, et al. Stigma towards depression in a community-based sample in China. Compr Psychiatry (2020) 97:152152. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152152

44. Munyogwa MJ, Mtumwa AH. The prevalence of abdominal obesity and its correlates among the adults in dodoma region, tanzania: a community-based cross-sectional study. Adv Med (2018) 2018:6123156. doi: 10.1155/2018/6123156

45. Fischer EH, Farina A. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychologial help: a shortened form and considerations for research. J Coll Stud Dev (1995) 36(4):368–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01740304

46. Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM. Reliability and validity of the Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form. Psychiatry Res (2008) 159(3):320–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.020

47. Fang S, Yang BX, Yang F, Zhou Y. Study on reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form for community population in China. Chin Nurs Res (2019) 33(14):2410–4. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2019.14.009

48. Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

49. Winkens LHH, van Strien T, Brouwer IA, Penninx BWJH, Visser M, Lähteenmäki L. Associations of mindful eating domains with depressive symptoms and depression in three European countries. J Affect Disord (2018) 228:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.069

50. Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam. Pract (1978) 6(6):1231–9.

51. Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Predictors of depression stigma. BMC Psychiatry (2008) 8(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-8-25

52. Ludman E, Katon W, Bush T, Rutter C, Lin E, Simon G, et al. Behavioural factors associated with symptom outcomes in a primary care-based depression prevention intervention trial. Psychol Med (2003) 33(6):1061–70. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300816x

53. Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, Rickwood D. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Can J Couns. (2005) 39(1):15–28. doi: 10.1037/t42876-000

54. Elhai JD, Voorhees S, Ford JD, Min KS, Frueh BC. Sociodemographic, perceived and objective need indicators of mental health treatment use and treatment-seeking intentions among primary care medical patients. Psychiatry Res (2009) 165(1-2):145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.12.001

55. Fang K, Pieterse AL, Friedlander M, Cao J. Assessing the psychometric properties of the Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form in mainland China. Int J Adv Couns. (2011) 33(4):309–21. doi: 10.1007/s10447-011-9137-1

56. Kramer EJ, Kwong K, Lee E, Chung H. Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans. West J Med (2002) 176(4):227–31. doi: 10.1620/tjem.198.55

57. Segal DL, Coolidge FL, Mincic MS, O’Riley A. Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: a cross-sectional study. Aging Ment Health (2005) 9(4):363–7. doi: 10.1080/13607860500131047

58. Staiger T, Waldmann T, Oexle N, Wigand M, Rüsch N. Intersections of discrimination due to unemployment and mental health problems: the role of double stigma for job- and help-seeking behaviors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2018) 53(10):1091–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1535-9

59. Gong AT, Furnham A. Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders in mainland China. Psych J (2014) 3(2):144–58. doi: 10.1002/pchj.55

60. Choudhry FR, Mani V, Ming LC, Khan TM. Beliefs and perception about mental health issues: a meta-synthesis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat (2016) 12:2807–18. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s111543

61. Xu X, Li XM, Xu D, Wang W. Psychiatric and mental health nursing in China: past, present and future. Arch Psychiatr Nurs (2017) 31(5):470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.06.009

62. Xiang YT, Ng CH, Yu X, Wang G. Rethinking progress and challenges of mental health care in China. World Psychiatry (2018) 17(2):231–2. doi: 10.1002/wps.20500

63. Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, Wells JE, Al-Hamzawi A, Borges G, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med (2014) 44(6):1303–17. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713001943

64. ten Have M, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Vilagut G, Kovess V, Alonso J. Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? Results from the European study of epidemiology of mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2010) 45(2):153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0050-4

65. Picco L, Abdin E, Chong SA, Pang S, Vaingankar JA, Sagayadevan V, et al. Beliefs about help seeking for mental disorders: findings from a mental health literacy study in Singapore. Psychiatr Serv (2016) 67(11):1246–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500442

66. Tieu Y, Konnert CA. Mental health help-seeking attitudes, utilization, and intentions among older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Aging Ment Health (2014) 18(2):140–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.814104

67. Coates D, Saleeba C, Howe D. Mental health attitudes and beliefs in a community sample on the central coast in Australia: barriers to help seeking. Community Ment Health J (2019) 55(3):476–86. doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0270-8

68. Park SK, Rhee MK, Barak MM. Job stress and mental health among nonregular workers in Korea: what dimensions of job stress are associated with mental health? Arch Environ Occup Health (2016) 71(2):111–8. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2014.997381

69. Call JB, Shafer K. Gendered manifestations of depression and help seeking among men. Am J Mens. Health (2018) 12(1):41–51. doi: 10.1177/1557988315623993

70. Vogel DL, Heimerdinger-Edwards SR, Hammer JH, Hubbard A. “Boys don’t cry”: examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. J Couns. Psychol (2011) 58(3):368–82. doi: 10.1037/a0023688

71. Cheng Y, Zhang L, Wang F, Zhang P, Ye B, Liang Y. The effects of family structure and function on mental health during China’s transition: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Fam. Pract (2017) 18(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0630-4

72. White M, Casey L. Helping older adults to help themselves: the role of mental health literacy in family members. Aging Ment Health (2017) 21(11):1129–37. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1206513

73. Zhang Y. Family functioning in the context of an adult family member with illness: a concept analysis. J Clin Nurs (2018) 27(15–16):3205–24. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14500

74. Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Toumbourou JW, Lubman DI. Parent and family factors associated with service use by young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Early Interv. Psychiatry (2015) 9(6):433–46. doi: 10.1111/eip.12211

75. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med (2015) 45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/s0033291714000129

76. Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, Schultze-Lutter F. Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry (2017) 210(4):261–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464

77. Vally Z, Cody BL, Albloshi MA, Alsheraifi SNM. Public stigma and attitudes toward psychological help-seeking in the United Arab Emirates: the mediational role of self-stigma. Perspect Psychiatr Care (2018) 54(4):571–9. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12282

78. Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Aust N. Z. J Psychiatry (2006) 40(1):51–4. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01741.x

79. Freund RJ, Wilson WJ, Mohr DL. Chapter 8-Multiple Regression. In: Freund RJ, Wilson WJ, Mohr DL, editors. Statistical Methods, 3rd ed. Boston: Academic Press (2010). p. 408–9.

80. Banwari G, Mistry K, Soni A, Parikh N, Gandhi H. Medical students and interns’ knowledge about and attitude towards homosexuality. J Postgrad. Med (2015) 61(2):95–100. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.153103

81. Fung K, Wong YLR. Factors influencing attitudes towards seeking professional help among East and Southeast Asian immigrant and refugee women. Int J Soc Psychiatry (2007) 53(3):216–31. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074541

Keywords: attitude, Chinese, community-dwelling population, help-seeking behaviour, professional psychological help

Citation: Chen P, Liu XJ, Wang XQ, Yang BX, Ruan J and Liu Z (2020) Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Among Community-Dwelling Population in China. Front. Psychiatry 11:417. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00417

Received: 19 November 2019; Accepted: 23 April 2020;

Published: 14 May 2020.

Edited by:

Paul R. Courtney, University of Gloucestershire, United KingdomReviewed by:

Yuen Yu Chong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaPhilip Batterham, Australian National University, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Chen, Liu, Wang, Yang, Ruan and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao Qin Wang, eGlhb3Fpbl93YW5nNzhAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Bing Xiang Yang, eWFuZ2Jpbmd4aWFuZzgyQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Pan Chen

Pan Chen Xiu Jun Liu

Xiu Jun Liu Xiao Qin Wang

Xiao Qin Wang Bing Xiang Yang

Bing Xiang Yang Juan Ruan

Juan Ruan Zhongchun Liu

Zhongchun Liu