94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 15 April 2020

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00270

This article is part of the Research Topic Toward Comprehensive Understanding of the Suicidal Phenomenon View all 21 articles

Background: To determine differences in the incidence and risks of suicide attempt (SA) and suicidal drug overdose (SDO) between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with and without comorbid depression by using data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database.

Methods: We analyzed the data of patients aged ≥20 years who had received a COPD diagnosis between 2000 and 2012. These COPD patients were divided into those with and without depression, and they were compared against a cohort from the general population. We calculated adjusted hazard ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for SA and SDO in the three cohorts after adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

Results: Until the end of 2012, 5.81% of patients with COPD developed depression. The incidence of SA and SDO in COPD patients with and without depression was 29.7 and 4.69 per 10,000 person-years and 71.2 and 20.9 per 10,000 person-years, respectively. COPD patients with depression had 13.6- and 10.0-fold higher risks of SA and SDO, respectively, than did controls. Particularly, an increased risk of SA caused by the enhancement effects of depression on COPD was noted in patients aged less than 50 years.

Conclusion: SA and SDO risks are extremely high in Taiwanese COPD patients with depression. Our findings suggest that clinicians should be aware that for COPD patients with comorbid depression, prescribing a large amount of medications may be associated with SA risk through SDO.

Globally, more than 800,000 people commit suicide every year, and the prevalence of completed suicide has progressively increased over the past decades (1). The annual prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt (SA) has been estimated to be 2.3% and 0.4% in Austria and 3.7% and 0.5% in the United States, respectively (2, 3). In European countries, the estimated rate of suicidal lethality is much higher in men than in women (13.9% vs. 4.1%) (4). The main possible reason for this sex difference is the different methods of SA adopted by men and women; violent methods are more common among men, and self-intoxication or suicidal drug overdose (SDO) is the most frequently chosen method among women (5). Therefore, we believe that adequately identifying individuals at a high risk of SA and interrupting their SA are urgently required for preventing suicide (6).

Depression is a well-established predictor of suicidal behaviors (7, 8). Researchers have investigated interactions between suicidality and medical conditions for years; however, only few researchers have conducted population-based studies on this topic (9, 10). In a recent large population-based cross-national study, Scott et al. reported several physical conditions that are potential independent risk factors for suicidality (10). Whether the probability of suicide is high in patients with chronic medical conditions or whether it is noted only in patients with specific disorders remains controversial (11). Sanna et al. reported an association between suicidality and several medical disorders; however, no association was noted between suicidality and pulmonary disease (12).

The Taiwanese government established the National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 1995, which covers approximately 99% of the residents of Taiwan for the past 2 decades (13). Both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and depression are common chronic disorders in the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Furthermore, pneumonia and COPD were the third and seventh causes of death in 2018 in Taiwan. As COPD is one of the major chronic physical disorders among elderly people, we believe that SA and SDO risks should be different between the general population and COPD patients with and without comorbid depression. Investigating these differences might be beneficial for the medical care systems in both Taiwan and other East Asian countries due to similarities in their ethnicity and cultural heritage (14).

The NHIRD of Taiwan is maintained by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan. It contains comprehensive NHI records of almost 99% of the population of Taiwan (13). The database includes the de-identified medical records of inpatients and outpatients and their prescription drug and other medical service records. Only patients with hospitalization records were included in this study. Diagnoses were defined based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. The Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan approved the study (CMUH104-REC2-115-CR4).

To assess the differences in SA and SDO risks between COPD patients with and without depression, 4 cohorts were defined in this study: the total COPD cohort comprising patients aged ≥20 years diagnosed with COPD (ICD-9-CM codes 491, 492, 494, and 496), the COPD with depression cohort comprising COPD patients with depression (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2, 296.3, 296.82, 300.4, and 311), the COPD without depression cohort comprising COPD patients without depression, and the comparison cohort comprising individuals without COPD and depression during 2000–2012. The index date was the date of COPD diagnosis. Controls (individuals without COPD and depression) were frequency matched based on sex, age, and index year at a ratio of 1:2. The primary outcome was the occurrence of SA (ICD-9-CM codes E950–E959) and SDO in NHIRD records. SDO was defined based on an emergency department visit, a clinic visit, or hospitalization with the ICD-9-CM codes 960-979 but without E codes. The study excluded patients aged <20 years and patients with SA or SDO before the index date. The same exclusion criteria were applied for the comparison cohort.

Comorbidities comprised several mental-health-associated diseases such as schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295), alcohol-related illness (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 303, 305.00, 305.01, 305.02, 305.03, 571.0, 571.1, 571.3, 790.3, and V11.3), anxiety (ICD-9-CM code 300.00), mental disorders (ICD-9-CM codes 290-319), and insomnia (ICD-9-CM codes 307.4 and 780.5), and these comorbidities with at least one hospitalization record before the index date were included in the analysis. The end date of the follow-up period was the date of SA or SDO occurrence, patient death, patient withdrawal from the NHI program, or December 31, 2012, whichever occurred first.

Categorical and continuous variables in this study are presented by number (%) and mean ± standard deviation, respectively. The chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables were performed to examine the differences in these variables among the cohorts. Incidence rates of SA and SDO were calculated by dividing SA and SDO events by person-years (every 10,000 person-years). Cumulative incidence curves of SA and SDO in the cohorts were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and log-rank tests were applied to test the differences in the curves. Hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted HRs (aHRs), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of SA and SDO were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the risks of SA and SDO among the cohorts. The level of significance was set at.05. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

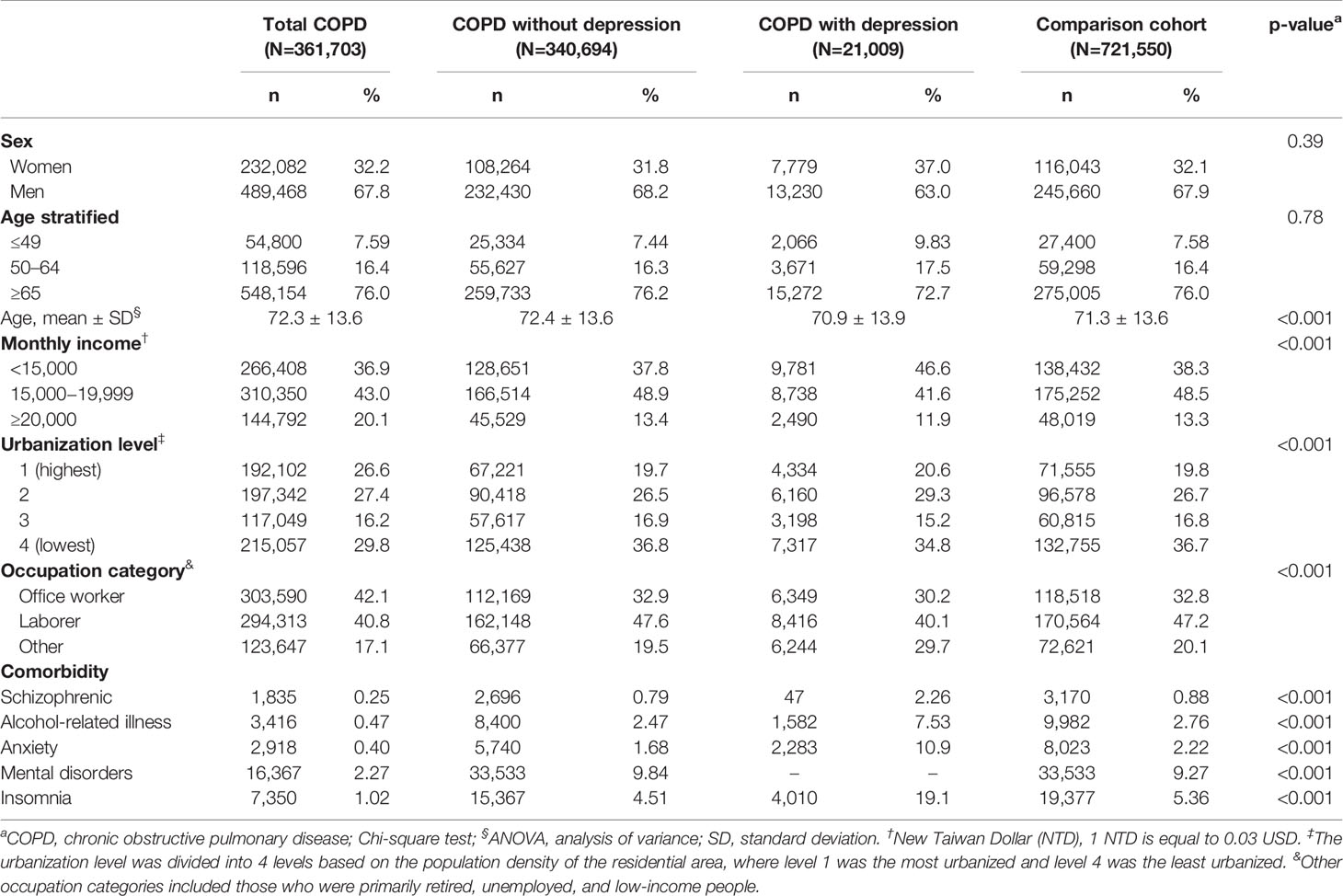

Four cohorts were defined in this study: total COPD (n = 361,703), COPD without depression (n = 340,694), COPD with depression (n = 21,009), and comparison (n = 721,550; without COPD and depression) cohorts. Because sex, age, and index year were frequency matched, no significant differences were found in sex (P =.39) and age (P =.78) among the cohorts. Significant differences were observed in monthly income, urbanization level, occupation category, and comorbidities among these cohorts (P < .001; Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of demographic characteristics and comorbidities among COPD cohorts and the comparison cohort.

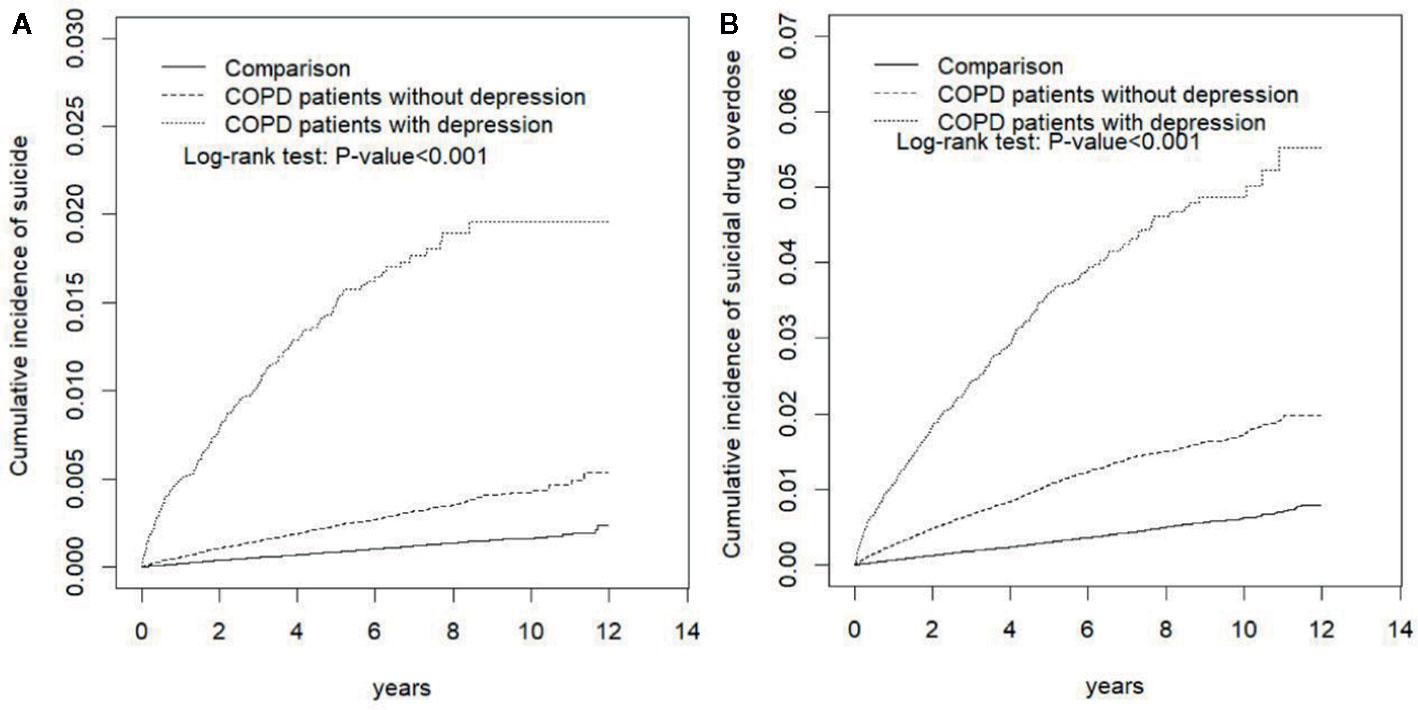

Figure 1 displays the cumulative incidence of SA and SDO. The figure indicates significant differences in the cumulative incidence rates of SA and SDO among the COPD with and without depression cohorts and the comparison cohort. Table 2 presents the incidence rates of and HRs of SA across different demographic characteristics. Compared with the reference group for each variable, a significantly high SA risk was observed after adjustment for demographic characteristics and comorbidities in COPD patients (aHR, 3.06; 95% CI, 2.72–3.45), COPD patients without depression (aHR, 2.49; 95% CI, 2.19–2.82), and COPD patients with depression (aHR, 13.6; 95% CI, 11.3-16.4) as well as in patients aged <50 years (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.11–1.69), with monthly incomes of New Taiwan Dollar (NTD) < 15,000 (aHR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.19–1.87) and NTD15,000–19,999 (aHR, 1.48, 95% CI, 1.19–1.83), living in a residential area with a low urbanization level (level 2: aHR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.14–1.62; level 3: aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.08–1.61; and level 4: aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.11–1.59), who worked as laborers (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16–1.62), with alcohol-related illness (aHR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.64–2.79), and with anxiety (aHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.02–1.87) (Table 2).

Figure 1 Comparison of the Cumulative Incidence of (A) Suicide Attempt and (B) Suicidal Drug Overdose Among COPD Patients With Depression, COPD Patients Without Depression, and the Normal Population. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

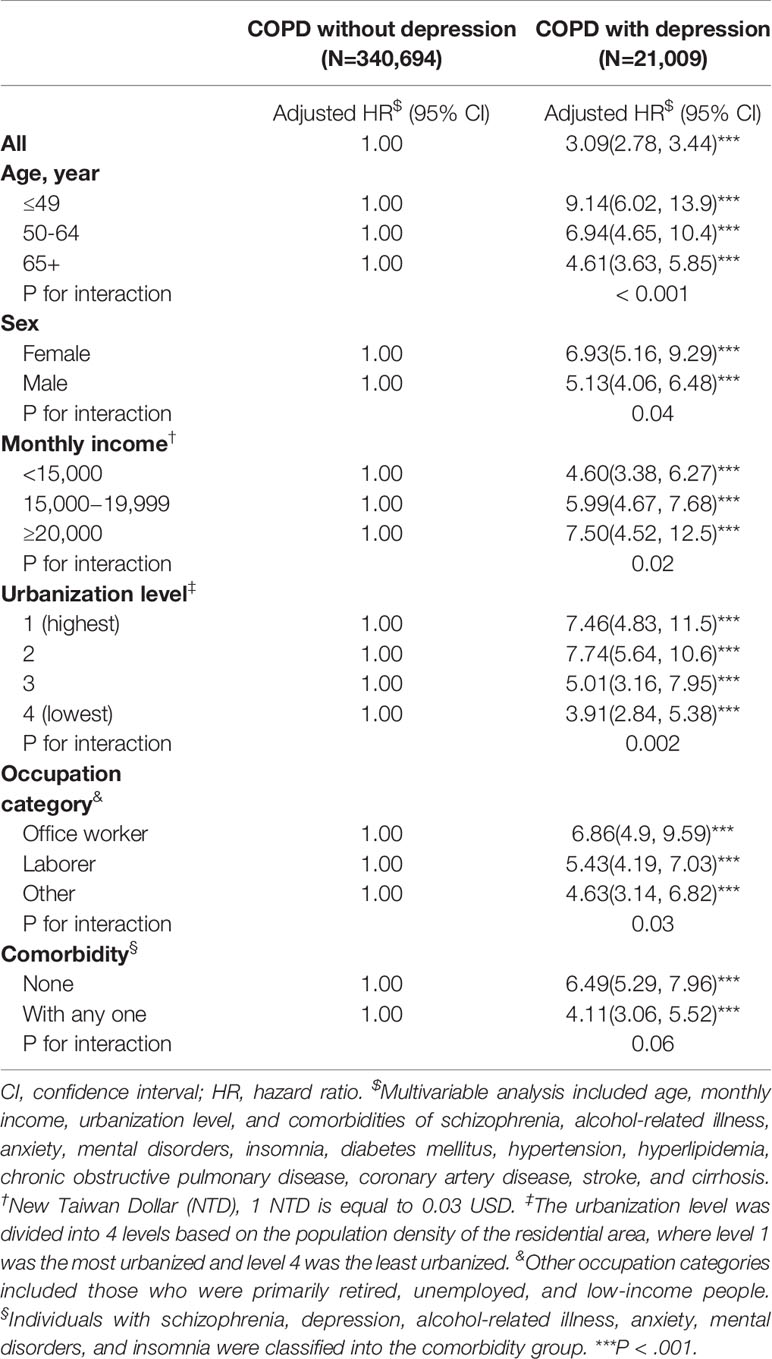

Table 3 presents that compared with COPD patients without depression, a significantly high SA risk was observed in COPD patients with depression (aHR, 3.09; 95% CI, 2.78–3.44) as well as in patients aged <50 years (aHR, 9.14; 95% CI, 6.02–13.9), 50–64 years (aHR, 6.94; 95% CI, 4.65–10.4), and >65 years (aHR, 4.61; 95% CI, 3.63–5.85); female (aHR, 6.93; 95% CI, 5.16–9.29) or male patients (aHR, 5.13; 95% CI, 4.06–6.48); patients with monthly incomes of NTD <15,000 (aHR, 4.60; 95% CI, 3.38–6.27), 15,000–19,999 (aHR, 5.99; 95% CI, 4.67–7.68), and >20,000 (aHR, 7.50; 95% CI, 4.52–12.5); patients living in areas with urbanization level 1 (aHR, 7.46; 95% CI, 4.83–11.5), level 2 (aHR, 7.74; 95% CI, 5.64–10.6), level 3 (aHR, 5.01; 95% CI, 3.16–7.95), and level 4 (aHR, 3.91; 95% CI, 2.84–5.38); patients employed as office workers (aHR, 6.86; 95% CI, 4.90–9.59), laborers (aHR, 5.43; 95% CI, 4.19–7.03), and other types of workers (aHR, 4.63; 95% CI, 3.14–6.82); patients without any comorbidity (aHR, 6.49; 95% CI, 5.29–7.96); and patients with any one of the comorbidities (aHR, 4.11; 95% CI, 3.06–5.52) (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison of incidence and hazard ratio of suicide attempt stratified based on age, sex, and comorbidities between copd patients with and without depression.

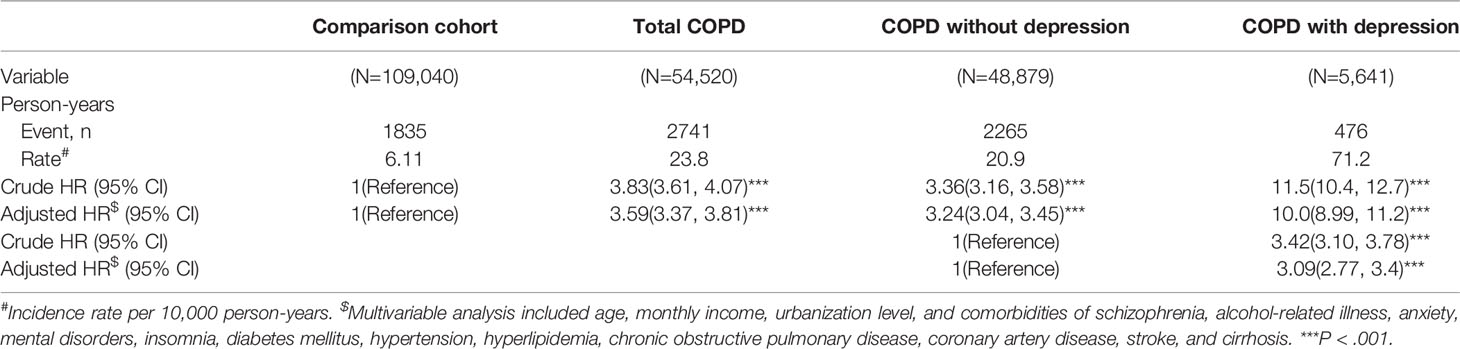

The event numbers, incidence rates, and HRs of SDO of COPD patients with and without depression are shown in Table 4. Patients with COPD (aHR: 3.59; 95% CI, 3.37–3.81), COPD patients without depression (aHR, 3.24; 95% CI, 3.04–3.45), and COPD patients with depression (aHR, 10.0; 95% CI, 8.99–11.2) had a significantly higher SDO risk than controls. Specifically, COPD patients with depression had a higher incidence (71.2 per 10,000 person-years) and risk of SDO than COPD patients without depression (aHR, 3.09; 95% CI, 2.77–3.40) (Table 4).

Table 4 Overall incidence of suicidal drug overdose (per 10,000 person-years) and estimated hazard ratio according to copd patients with or without depression through the cox method.

Moreover, to evaluate whether patients with COPD and depression might have higher SA and SDO risks than patients with depression without COPD, we further compared COPD patients with depression (n = 19,725) with non-COPD patients with depression who were frequency matched based on sex, age, and index year (Supplementary Tables). COPD patients with depression had a moderately high risk of SA (aHR, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.85–4.52) and SDO (aHR, 4.97; 95% CI, 4.20–5.88) than non-COPD patients with depression.

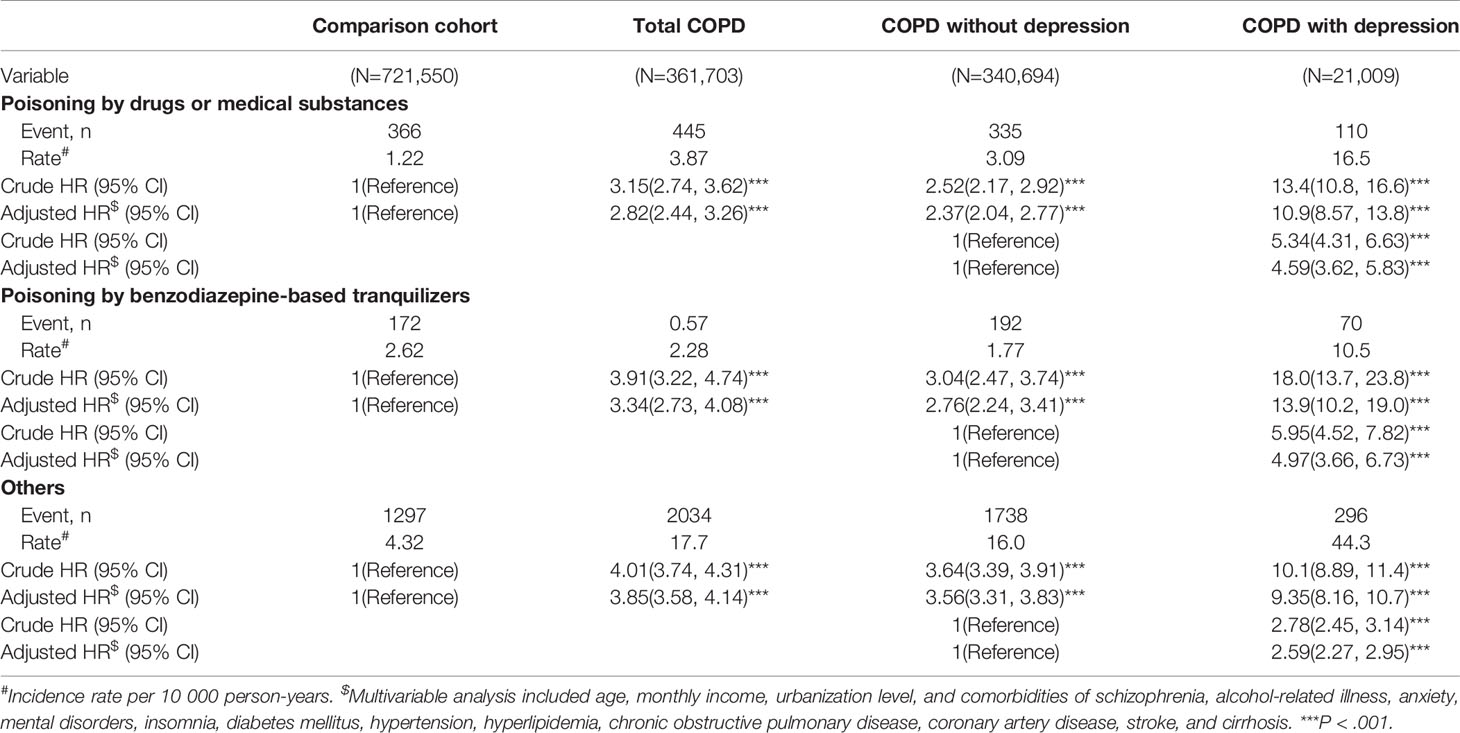

To assess the incidence and risk of different SDO types, patients with SDO were classified based on the different methods of suicide (Table 5), such as poisoning through drugs or medical substances, benzodiazepine-based tranquilizers, and other methods. Compared with controls, patients with COPD (aHR, 2.82; 95% CI, 2.44–3.26), COPD patients without depression (aHR, 2.37; 95% CI, 2.04–2.77), and COPD patients with depression (aHR, 10.9; 95% CI, 8.57–13.8) had a significantly high risk of poisoning through drugs or medicinal substances. Specifically, COPD patients with depression had a higher incidence (16.5 per 10,000 person-years) and risk of poisoning through drugs or medical substances (aHR, 4.59; 95% CI, 3.62–5.83) than those without depression.

Table 5 Overall incidence with different methods of suicidal drug overdose (per 10 000 person-years) and estimated hazard ratio according to copd patients with or without depression through the cox method.

Compared with controls, patients with COPD (aHR, 3.34; 95% CI, 2.73–4.08), COPD patients without depression (aHR, 2.76; 95% CI, 2.24–3.41), and COPD patients with depression (aHR, 13.9; 95% CI, 10.2–19.0) had a significantly high risk of poisoning through benzodiazepine-based tranquilizers. Specifically, COPD patients with depression had a higher incidence (10.5 per 10,000 person-years) and risk of poisoning through benzodiazepine-based tranquilizers (aHR, 4.97; 95% CI, 3.66–6.73) than those without depression.

Compared with controls, a significantly high risk of poisoning through other methods was observed in patients with COPD (aHR, 3.85; 95% CI, 3.58–4.14), COPD patients without depression (aHR, 3.56; 95% CI, 3.31-3.83), and COPD patients with depression (aHR, 9.35; 95% CI, 8.16–10.7). Specifically, a significantly higher risk of poisoning through other methods was observed in COPD patients with depression (aHR, 2.59; 95% CI, 2.27–2.95) than in those without depression (Table 5).

Despite the urgency and necessity of reducing suicidality worldwide, several developed countries have not invested sufficient resources in SA research and prevention (5). An obvious imbalance exists between the magnitude of the suicide problem and the knowledge required to address it. The present study involved a 13-year follow-up of patients aged ≥20 years, and the results revealed that 5.81% of patients with COPD developed depression. One of our previous studies with a similar design showed that the incidence of SA and SDO in patients with depression was 3.76 and 6.97, respectively, per 10,000 person-years (15). The current study revealed that the incidence of SA and SDO in COPD patients with depression was 29.7 and 71.2 per 10,000 person-years, respectively. COPD patients with depression had a 13.6- and 3.09-fold higher SA risk than did controls and COPD patients without depression, respectively. Furthermore, COPD patients with depression had a 10.0- and 3.09-fold higher SDO risk than did controls and COPD patients without depression, respectively. Contrary to the belief that COPD moderately increases SA and SDO risks in patients with depression, this large-scale study revealed enhancement of SA and SDO risks in COPD patients with coexisting depression. Furthermore, regardless of the confounding effects of socioeconomic factors such as monthly income, urbanization level, and occupation category, age less than 50 years is a specifically high risk factor for SA in COPD patients that interact with depression. Moreover, no differences were observed in SA risk between male and female patients in this study when considering the overwhelming enhancement effects of depression on COPD.

We usually evaluate suicidality using self-reported passive and active death-related thoughts collected through a questionnaire with a binary (yes/no) response. Using this method, suicidal ideation can be investigated; however, valid methods for assessing suicidal behavior, SA, and suicidal death risk are unavailable. Moreover, in the United Kingdom, 1 of 5 adults considers suicide; however, only one in 15 attempts suicide (6). Another study reported that only a small proportion of individuals who exhibit suicidal ideation actually attempt suicide (16). Our study showed proportionally extreme increases in SA and SDO risks resulting from the effects of comorbid depression on COPD. Compared with the annual SA prevalence of 0.4%–0.5% in Western countries (2, 3), the prevalence in our patients with COPD and depression was lower than expected. However, as a nonviolent method of SA, SDO is frequently noted in Taiwanese patients with COPD and depression. Although more than 95% of the people who attempt SDO could eventually survive in Europe (17), SDO causes considerable burden in Asian countries; hence, SA through SDO should be effectively prevented (18, 19). Our results implied that COPD patients could be dangerously abuse prescribed medicines and tranquilizers for attempting suicide through overdose, especially when these patients have comorbid depression. This study reiterates that medicines and tranquilizers used for self-poisoning are highly accessible in Taiwan, because of the restricted access to firearms in Taiwan, similar to most Asian countries. Therefore, careful and long-term accurate assessment should be performed before prescribing multiple medicines or tranquilizers to COPD patients with depression. Moreover, rather than focusing on their suicidal ideation only, awareness of the relationships of different physical disorders with depression would help identify patients at a high SA risk, thereby preventing suicidal death.

However, depression mediates the relationship between value strain, deprivation strain, aspiration strain, coping strain, and suicidality (8). Psychological strain may cause suicidal behaviors or impulsive suicide in patients with a lack of social support/coping capacities (20), poor functional status (21, 22), and disorders of subjective perception including anxiety, panic, or other mental disorders (23, 24). Those might partially explain the enhancement of depression on suicidal behaviors in COPD patients. Nonetheless, the actual interactions between COPD and depression on suicidality warrant additional investigational studies. Given the neuro-psychological pathology of COPD, considerable biological evidence has demonstrated that chronic inflammation, such as that in COPD, may increase the pathologies over the blood–brain barrier, glutamate regulation, microglia activation, and autoimmune response (25, 26). These can affect patients’ physical endurance, sleep, chronic cognition, and associated psychosocial sequelae, thereby contributing to patients’ suicidality. Furthermore, oxidative stress in COPD could decrease serotonin synthesis owing to the effects of hypoxemia on tryptophan hydroxylase, and oxidative stress could cause depression and suicidality (27). These findings revealed a notably bidirectional relationship between depression and COPD that increases suicidality in affected patients.

Our findings proved that depression is an extreme factor enhancing suicidal behaviors in patients with COPD. However, this study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study that used NHIRD claims data with hospitalization records related to COPD and depression during the study period. Although the accuracy of inpatient data is assured because of severe penalty associated with providing incorrect data, identifying SA, SDO, COPD, and depression based on the ICD-9-CM coding system is still associated with a possibility of underdiagnosis and underestimation. Minor SA and SDO in patients with COPD might not require medical services, resulting in the underestimation of SA and SDO risks. Second, we could not directly contact patients to determine the severity of COPD and depression, their actual taken medications, or treatments for their disorders because patients’ identities were anonymized in the NHIRD. These details may confound their suicidality. Finally, even though our study design controlled for numerous confounders to the best of our knowledge, some unmeasured or unknown confounders may remain. Further large-scale studies are necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of suicidality in patients with COPD with and without depression; such studies would help establish an effective prevention system in Taiwan and worldwide.

COPD and depression increase the risk of suicidality individually and synergistically. COPD patients with depression have increased SA and SDO risks. Specifically, COPD patients with depression aged less than 50 years have high SA risk. Our findings provide crucial information for suicide prevention for clinicians and the governments of Taiwan and other Asian countries. In COPD patients with depression, long-term medicines or tranquilizers should be prescribed and dispensed with caution.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan approved the study (CMUH104-REC2-115-CR4). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Study conception/design: TH, C-HK. Provision of study material and patients: C-HK. Collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript: all authors.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This study was supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW109-TDU-B-212-114004), MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 108-2321-B-039-003-), and Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00270/full#supplementary-material

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NHI, National Health Insurance; NHIRD, National Health Insurance Research Database; NTD, New Taiwan Dollar; HR, hazard ratio; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; SA, suicide attempt; SDO, suicidal drug overdose.

1. World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; (2014).

2. Johnston AK, Pirkis JE, Burgess PM. Suicidal thoughts and behaviours among Australian adults: findings from the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2009) 43:635–43. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970874

3. Crosby AE, Han B, Ortega LA, Parks SE, Gfroerer J. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged ≥18 years- United States, 2008-2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2011) 60:1–22.

4. Mergl R, Koburger N, Heinrichs K, Székely A, Tóth MD, Coyne J, et al. What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? An epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PloS One (2015) 10:e0129062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129062

6. Large MM, Ryan CJ, Carter G, Kapur N. Can we usefully stratify patients according to suicide risk? BMJ (2017) 2017;359:j4627. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4627

7. Jiang Z, Liu Y, Zhang J, Lamis DA. The Role of depressive symptoms in suicide attempt in rural China. J Nerv Ment Dis (2019) 207:561–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001006

8. Kang N, You J, Huang J, Ren Y, Lin MP, Xu S. Understanding the pathways from depression to suicidal risk from the perspective of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav (2019) 49:684–94. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12455

9. Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, Kopp A, Redelmeier DA. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med (2004) 164:1179–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179

10. Scott KM, Hwang I, Chiu WT, Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Angermeyer M, et al. Chronic physical conditions and their association with first onset of suicidal behavior in the world mental health surveys. Psychosom Med (2010) 72:712–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e3333d

11. Webb RT, Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Qin P, Creed F, Kapur N. Suicide risk in primary care patients with major physical diseases: a case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2012) 69:256–64. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1561

12. Sanna L, Stuart AL, Pasco JA, Kotowicz MA, Berk M, Girardi P, et al. Suicidal ideation and physical illness: does the link lie with depression? J Affect Disord (2014) 152-154:422–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.008

13. Database NHIR. Taiwan [cited 2017]. Available from: http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/index.html. (Accessed March 8, 2019).

14. Ying YW, Han M. Cultural orientation in Southeast Asian American young adults. Cultur. Divers Ethn Minor Psychol (2008) 14:29–37. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.29

15. Harnod D, Harnod T, Lin CL, Shen WC, Kao CH. Increased risks of suicide attempt and suicidal drug overdose following admission for head injury in patients with depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16:pii: E3524. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193524

16. Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Oquendo MA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Grant BF, et al. Estimating risk for suicide attempt: are we asking the right questions? Passive suicidal ideation as a marker for suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord (2011) 134:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.026

17. Mergl R, Koburger N, Heinrichs K, Székely A, Tóth MD, Coyne J, et al. What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? an epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PloS One (2015) 10:e0129062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129062

18. Verma V, Paul S, Ghose A, Eddleston M, Konradsen F. Treatment of self-poisoning at a tertiary-level hospital in Bangladesh: cost to patients and government. Trop Med Int Health (2017) 22:1551–60. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12991

19. Chang CH, Chen SJ, Liu CY, Tsai HC. Suicidal drug overdose following stroke in elderly patients: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat (2018) 14:443–50. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S157494

20. Marusic A, Goodwin RD. Suicidal and deliberate self-harm ideation among patients with physical illness: the role of coping styles. Suicide Life Threat Behav (2006) 36:323–8. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.323

21. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, Newsom JT. Physical illness, functional limitations, and suicide risk: a population-based study. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2007) 77:56–60. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.56

22. Tao YX, Wang L, Dong XY, Zheng H, Zheng YS, Tang XY, et al. Psychometric properties of the physical activity scale for the elderly in Chinese patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2016) 12:105–14. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S120700

23. Dong XY, Wang L, Tao YX, Suo XL, Li YC, Liu F, et al. Psychometric properties of the anxiety inventory for respiratory disease in patients with COPD in China. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2016) 12:49–58. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S117626

24. Olfson M, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Farber L. Suicidal ideation in primary care. J Gen Intern Med (1996) 11:447–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02599038

25. Rosenblat JD, Cha DS, Mansur RB, McIntyre RS. Inflamed moods: a review of the interactions between inflammation and mood disorders. Prog Neuro-psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2014) 53:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.01.013

26. Kayser MS, Dalmau J. The emerging link between autoimmune disorders and neuropsychiatric disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci (2011) 23:90–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.23.1.90

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, National Health Insurance, suicide, suicidal drug overdose

Citation: Lin C-Y, Harnod T, Lin C-L and Kao C-H (2020) Suicide Attempt and Suicidal Drug Overdose in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients With or Without Depression. Front. Psychiatry 11:270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00270

Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 19 March 2020;

Published: 15 April 2020.

Edited by:

Alberto Forte, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Liliana Dell’Osso, University of Pisa, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Lin, Harnod, Lin and Kao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomor Harnod, dG9tb3JoYUB5YWhvby5jb20udHc=; Chia-Hung Kao, ZDEwMDQwQG1haWwuY211aC5vcmcudHc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.