- 1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, Yufu, Japan

- 2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences, Oita University, Oita, Japan

Objectives: Recently, a 4-week mindfulness-based intervention followed by a 4-week existential approach was found to be as effective for increasing self-compassion as an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention. The purpose of the present study was to identify the factors that predicted change in self-compassion during the 8-week mindfulness-based intervention.

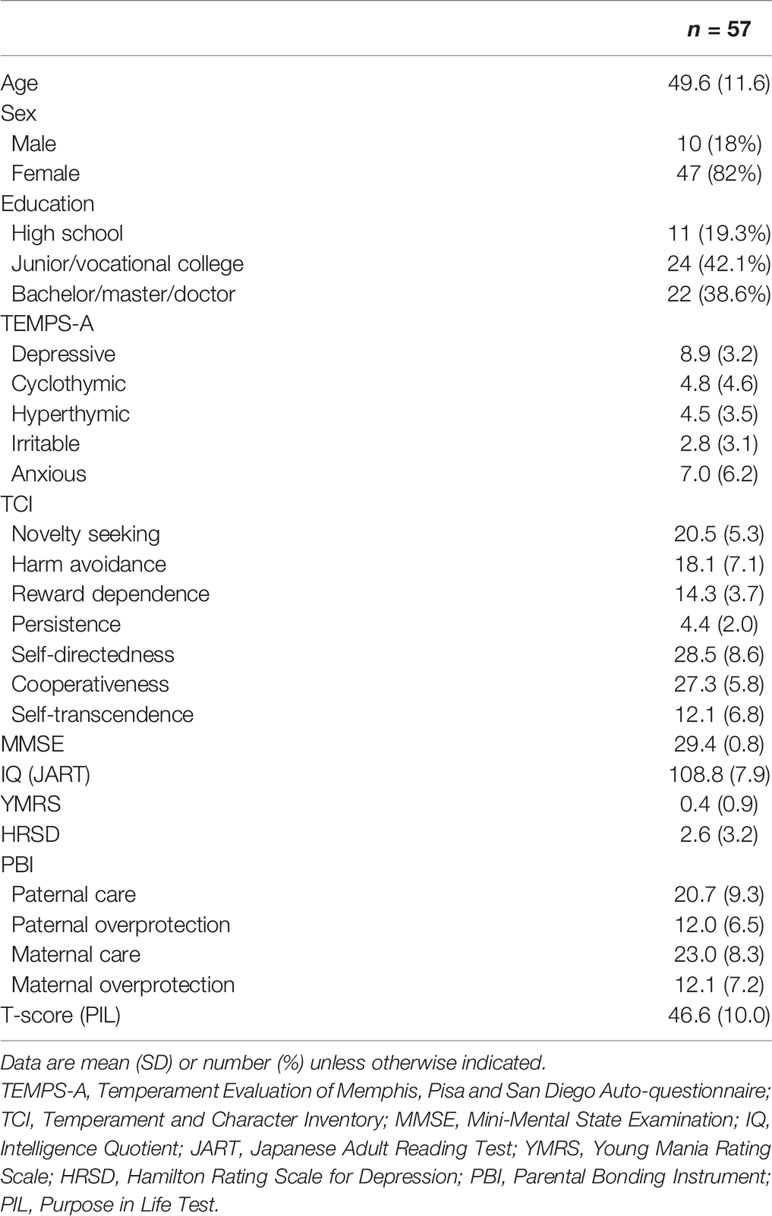

Methods: Fifty-seven of the 61 completers of the 8-week mindfulness-based intervention provided baseline, 4-week, and 8-week self-compassion scale scores. The mean age of the 47 females and 10 males was 49.6 years. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were generated on the associations between the change of total self-compassion scale scores from baseline to 8 weeks with age; gender; and the baseline scores on the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa and San Diego Auto-questionnaire, Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI), Mini-Mental State Examination, Japanese Adult Reading Test, Young Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Parental Bonding Instrument, and purpose in life (PIL). Multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of the change in total self-compassion scale scores.

Results: Novelty seeking (TCI) was significantly and negatively associated with the change in total self-compassion scale scores, whereas the PIL scores were significantly and positively associated with the change in total self-compassion scale scores. Novelty seeking was not significantly associated with baseline, 4-week, or 8-week total self-compassion scale scores, whereas the PIL scores were significantly and positively associated with baseline, 4-week, and 8-week total self-compassion scale scores. The limitation of the present study was a relatively small number of subjects which deterred a more sophisticated analysis of the pathways involved.

Conclusions: The present findings suggest that more PIL and less novelty seeking predict improvements in self-compassion during mindfulness-based interventions, although novelty seeking might substantially predict the improvement but self-compassion scale and PIL might somewhat conceptually overlap.

Introduction

Recently, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine whether a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and an existential approach could be sequentially combined and whether they operated antagonistically or cooperatively. In that study, apparently healthy participants were first assigned to a wait-listed group and, then, they were randomized into the 8-week MBI group or the 4-week MBI followed by 4-week existential approach (EXMIND) group. The main outcome variable was self-compassion measured on a self-compassion scale with total scores assessed at 0, 4, and 8 weeks during the interventions or waiting period. Both intervention groups had significantly increased total self-compassion scale scores compared to those of the waiting group, suggesting that EXMIND was not antagonistic and might have cooperative effects with the mindfulness approach, and that EXMIND might be a useful treatment (1).

As we described in the previous paper (1), mindfulness is the process of acknowledging subjective experience, and it has emotional regulation process, which is broader than attentional control. Although attention is a key component of mindfulness practice, mindfulness also incorporates an openness to experience, which reflects a non-judgmental acceptance strongly linked to improved health. MBIs can be traced back to the late 1970s. A mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program was begun in 1979 in the basement of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (2), where Kabat-Zinn (3) initially reported that mindfulness meditation produced significant pain reduction in chronic pain patients. Since then, numerous treatment protocols based on MBSR, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), have been developed. MBSR and MBCT are two of the most widely used MBIs. Their positive effects on mental health and quality of life have been reported in diverse clinical and non-clinical populations (4–6).

In our study (1), during the first half (4 weeks), both the MBI and EXMIND groups attended the same MBI sessions which included raisin exercise, mindful breathing, body scan, walking meditation, and sitting meditation. Participants received explanatory notes at every session. Homework including both formal and informal training was encouraged for participants to train themselves for mindfulness reskilling. During the second half (4 weeks), the MBI group continued to perform meditation and homework, and thereafter discussed their experiences during individual instruction; at session 5, sitting meditation and individual instructions for an openness to experience and non-judgmental acceptance during meditation; at session 6, sitting meditation and individual instructions for a gap between thought and fact, making a meditation plan, and recording achievement as homework; at session 7, sitting meditation and individual instructions for widening opportunities for selection, and resolution of the gap between meditation plan and achievement; and at session 8, sitting meditation, individual instructions for utilizing mindfulness for daily life, and seeking triggers to remind of mindfulness. Therefore, we believe that the MBI in tour study resemble MBSR and MBCT in many ways.

Nonetheless, the factors that predict MBI have not been determined. For example, comorbid personality disorders might predict non-completion of MBCT (7) whereas openness and agreeableness might predict greater use of MBSR (8). Men or highly extraverted individuals experience considerably lower MBCT effectiveness (9), and the same author found that neuroticism predicted benefits of MBSR (10). High educational attainment predicted a decrease in depressive symptoms by MBCT (11). Greater depressive severity was associated with higher levels of mind-wandering (in contrast to mindfulness) and lower levels of self-compassion (12). The interaction between low conscientiousness and MBSR and that between high neuroticism and MBSR each predicted significantly lower levels of depression and distress at 12-month follow-up compared to women who were higher in conscientiousness or lower in neuroticism (13). The practice of mindfulness meditation was positively related to openness and extraversion and negatively related to neuroticism and conscientiousness (14). Both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were negatively associated with total mindfulness (15). Although MBCT was associated with significant increases in trait positive affect and momentary positive cognition (16), in a systematic review, two found no association between mindfulness interventions and cognitive function, two found improvement that was not sustained at the follow-up, and another two found sustained improvement at 2- or 6-months (17). We could not find any report showing cognition as a predictor of MBI responses. As for purpose in life (PIL; or life’s meaning), patients’ search for life’s meaning was the only significant predictor of willingness to participate in MBSR in cancer patients (18). Also, cancer patients endorsing higher levels of dispositional mindfulness were more likely to pay attention to positive experiences, a tendency which was associated with positive reappraisal of stressful life events. Moreover, patients who engaged in more frequent positive reappraisal had a greater sense of meaning in life (19). Finally, a meta-analysis showed that small and statistically significant pooled effects of MBIs on combined measures of psychological distress were found at post-intervention and follow-up, and that larger effects of MBIs on psychological distress were found in studies (a) adhering to the original MBI manuals, (b) with younger patients, (c) with passive control conditions, and (d) shorter time to follow-up (20). Overall, the literature suggests that people who are open to new experiences and extraverted, have a positive mood and have a greater PIL engage well in mindfulness behavioral intervention.

Therefore, it seems possible that gender, temperament, personality, education, cognition, mental state, parental bonding, and PIL may affect the effects of MBI. Considering these possibilities, in the present study, it was hypothesized that the effects of MBI may be associated with these factors.

The present study was performed to test the above hypothesis. In other words, in the previous study (1), MBI improved self-compassion of apparently healthy volunteers in the form of a group therapy at the first half and an individual therapy at the last half in a city hall. Therefore, the rationale of the present study was the effects of MBI on self-compassion in apparently healthy individuals and the purpose of the study was to determine which type of apparently healthy people can increase self-compassion via MBI.

Materials and Methods

This study used data derived from our previous study (1) that, in brief, was a randomized controlled trial at the Oita city hall (Horuto-Hall Oita), Japan. Participants were recruited in Oct 1, 2016 and June 30, 2018. The Institutional Review Board of Oita University Faculty of Medicine approved the trial on Sep 14, 2016 (number B16-023). All participants provided informed written consent. The protocols of the primary study conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Oita University Ethics Committee. Because the purpose of the present study was one of the purposes of the primary study, permission to use the secondary data use was assumed.

In advance, to detect changes in self-compassion scale scores, J score by MBI or EXMIND, considering the effect size of MBI may be 0.5 at a p-value of less than 0.05 with 80% power, 60 participants per group were estimated to be needed, allowing for 20% loss to follow-up (1). However, the effect size of 0.5 might have been overestimated. Fifty-seven of the 61 completers in the MBI group had baseline, 4-week, and 8-week self-compassion scale scores (21). The mean age of the 47 females and 10 males was 49.6 years. We investigated change over time in the total self-compassion scale scores using repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests and, when statistically significant, Tukey’s post hoc comparison tests were performed. Statistical relationships were tested (Pearson’s correlations) between the difference in total self-compassion scale scores from baseline to 8 weeks (Δself-compassion scale scores) and age; gender; the baseline scores of the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa and San Diego Auto-questionnaire (TEMPS-A) (22), Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (23), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (24), Japanese Adult Reading Test (JART) (25), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (26), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (27), Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) (28), and PIL (29), all of which were performed just before the MBI intervention. In addition, because high educational attainment predicted a decrease in depressive symptoms by MBCT (11), we investigated the association of educational level (1 = high school or less, 2 = college, and 3 = university or more) with Δself-compassion scale scores. Finally, a multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of the improvement in total self-compassion scale scores.

Results

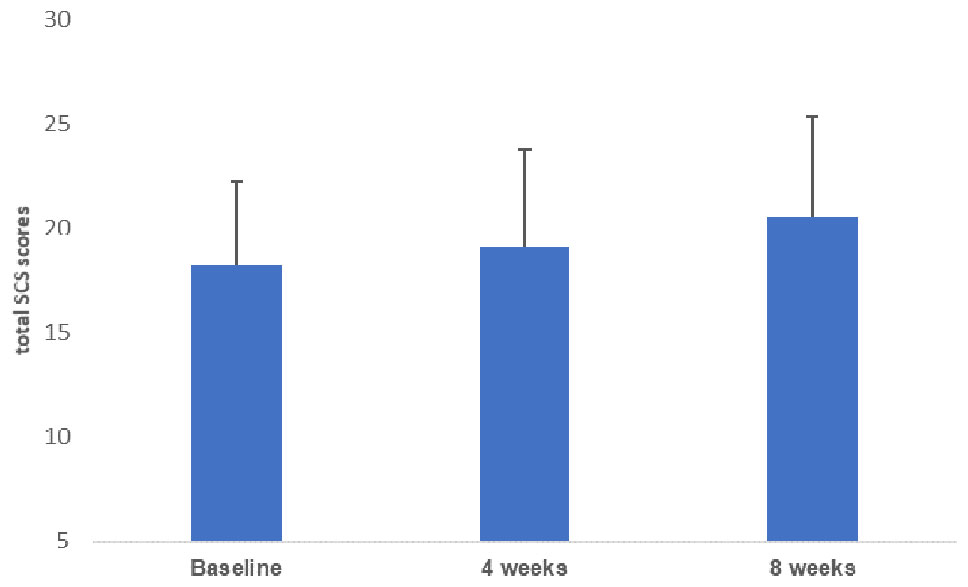

Table 1 shows the demographic variables and baseline scores of the psychological tests. Figure 1 depicts the change in the mean of total self-compassion scale scores over time [mean = 18.3 (SD = 4.0) at baseline, 19.1 (4.7) at 4 weeks, and 20.6 (4.8) at 8 weeks], and there was a significant change across time (F = 23.3, p = 0.0001) with a significant difference between baseline and 8 weeks (Tukey’s post hoc test, p = 0.02).

Figure 1 Changes in total self-compassion scale (SCS) scores from baseline to 8 weeks. The mean total self-compassion scale scores improved significantly from baseline to 8 weeks post-MBI. MBI, mindfulness-based intervention.

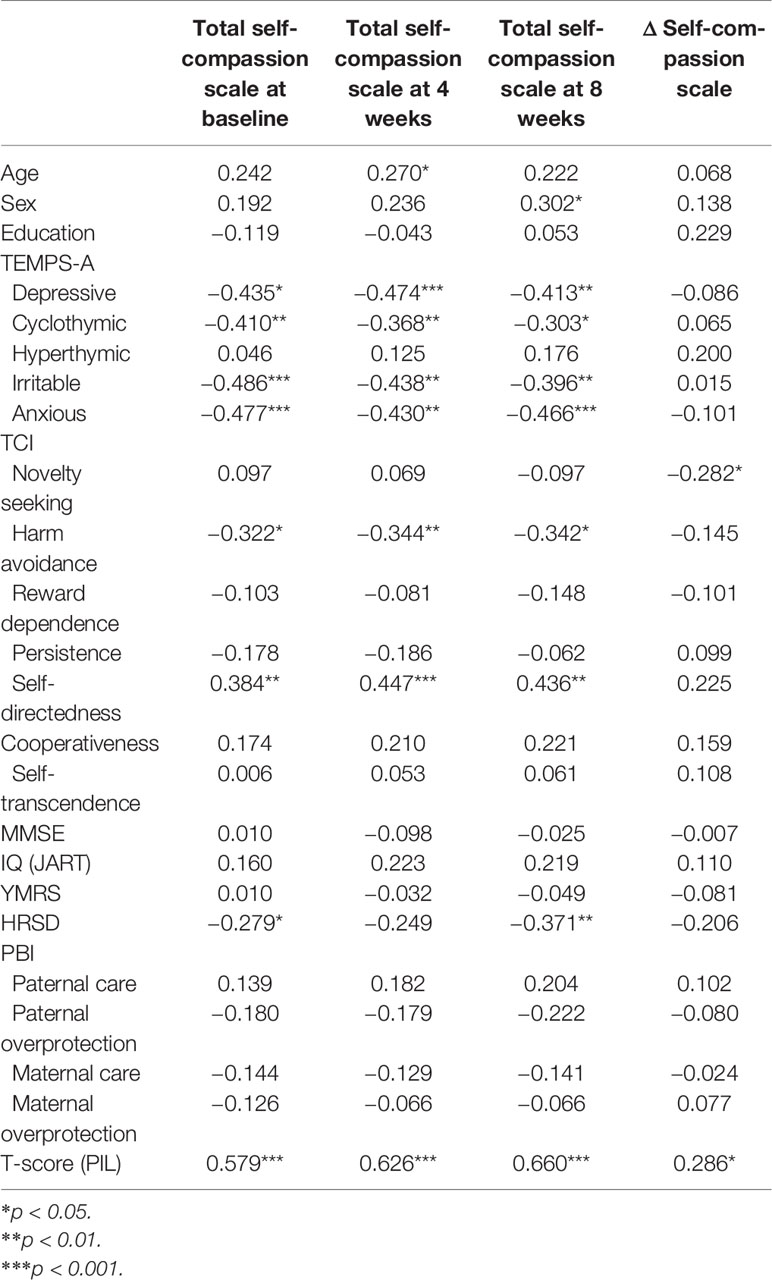

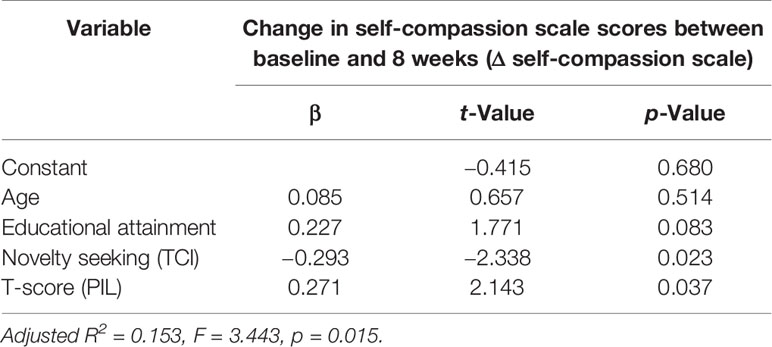

Table 2 shows the associations between the change between baseline and 8 weeks in total self-compassion scale scores (Δself-compassion scale scores) and age, gender, and the scores on TEMPS-A, TCI, MMSE, IQ (JART), YMRS, HRSD, PBI, and the T-scores (PIL). As shown in Table 2, novelty-seeking (TCI) was significantly and negatively associated with Δself-compassion scale scores (r = −0.282, p = 0.035) and the T-scores (PIL) significantly and positively associated with Δself-compassion scale scores (r = 0.286, p = 0.033). Educational attainment was not significantly associated with Δself-compassion scale scores (r = 0.229, p = 0.087). The multiple regression analysis with Δself-compassion scale scores as the dependent variable and novelty seeking (TCI), T-scores (PIL), age, and educational attainment as independent variables revealed that Δself-compassion scale scores were significantly and negatively associated with novelty seeking (TCI) (β = −0.293, p = 0.023) and significantly and positively associated with T-scores (PIL) (β = 0.271, p = 0.037). However, the associations with age and educational attainment were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3 Multiple regression analysis showing the effects of age, educational attainment, novelty seeking, and purpose in life score on change in self-compassion during an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention (n = 57).

As shown in Table 2, novelty seeking was not significantly associated with the baseline, 4-week, or 8-week total self-compassion scale scores, whereas the T-scores (PIL) significantly and positively associated with the baseline, 4-week, and 8-week total self-compassion scale scores.

As sub-analyses, we calculated the percentage changes as ‘(self-compassion score at baseline minus self-compassion score at 8 weeks)/self-compassion score at baseline’ and performed correlation with novelty seeking (r = −0.249, p = 0.064) and PIL (r = 0.145, p = 0.285) by Pearson’s coefficient. Moreover, multiple regression analyses were performed with adjustment factors which were associated the percentage changes (p < 0.3). As a result, the percent changes were significantly and inversely associated with novelty seeking (β = −0.454, p = 0.003), but not with PIL (β = −0.079, p = 0.648), although this multiple regression analysis included 9 independent factors which were too many for 57 subjects to draw a conclusion. In any case, it should be noted that the correlation of the simple subtraction and the percent changes was highly significant in our subjects (r = 0.958, p = 0.0001).

Discussion

These findings indicate that self-compassion significantly improved after the 8-week MBI and that improvement was significantly predicted by less novelty seeking and more PIL, suggesting that novelty seeking and PIL predict changes in self-compassion during this MBI. It should be noted that the novelty-seeking scores were not associated with total self-compassion scale scores, whereas the T-scores (PIL) were significantly and positively associated with the baseline, 4-week, and 8-week total self-compassion scale scores. This finding most likely means that self-compassion is closely related to PIL, but weakly related to novelty seeking. In concrete terms, because several of the self-compassion scale and PIL questionnaire items seem similar, self-compassion scale and PIL might somewhat conceptually overlap, partly explaining the significant positive association between the baseline and the 8 weeks post-MBI self-compassion scale scores. However, less novelty seeking is likely to actually predict Δself-compassion scale scores because the novelty-seeking scores were not associated with the baseline, 4-week, or 8-week total self-compassion scale scores.

With regard to the association between novelty seeking, mindfulness, and self-compassion, there is a report showing that individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) had lower mindfulness and higher novelty seeking whereas those without ADHD had higher mindfulness and lower novelty seeking (30), suggesting a possibility that individuals with novelty seeking find it harder to disengage from spontaneous thoughts during a mindfulness exercise even if they do not suffer from ADHD, and that they may obtain less self-compassion as an effect of mindfulness.

The TEMPS-A and other character/personality scores of TCI (except novelty seeking) did not significantly predict the effects of MBI. In particular, hyperthymic temperament and cyclothymic temperament are widely accepted as premorbid temperaments of bipolar disorder, and the present findings suggest that such bipolarity do not predict the effects of an MBI, at least measured via change in self-compassion. Regarding educational attainment, in contrast to our previous report (1), the effects of MBI were not significantly predicted in our relatively small sample. The p-value of 0.083 implies the possibility that educational attainment might be a significant predictor for larger samples of participants.

It should be noted that we did not measure openness as a predictor of the responses to MBI. Since openness has been reported to be associated with more use of MBSR (8) and more mindfulness meditation (14), there remains a possibility that openness might have been selected as a predictor in this study if we measured it.

The limitation of the present study was a relatively small number of subjects which deterred a more sophisticated analysis of the pathways involved. Another limitation may be the likelihood of false positive effects due to multiple comparison and the exploratory nature of the analyses.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that more PIL and less novelty seeking predict improvements in self-compassion during MBIs., and that apparently healthy individuals with more PIL and/or less novelty seeking can increase their self-compassion with the training of MBIs.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Oita University Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MA, TT, NK, and AS planned this study. MA, NK, and AS were actual working research team members. KH, MS, HH, KK, and NI discussed the results with the actual working members. MA and TT mostly wrote the manuscript; the other authors supported the study and checked the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the study’s participants for their cooperation.

References

1. Sakai A, Terao T, Kawano N, Akase M, Hatano K, Shirahama M, et al. Existential and mindfulness-based intervention to increase self-compassion in apparently healthy subjects (the EXMIND Study): a randomised controlled trial. Front Psychiatry (2019) 10:538. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00538

2. Cullen M. Mindfulness-based interventions: an emerging phenomenon. Mindfulness (2011) 2:186–93. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0058-1

3. Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (1982) 4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

4. Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev (2013) 33:763–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

5. Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med (2014) 174:357–68. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed. 2013.13018.

6. Demarzo MMP, Montero-Marin J, Cuijpers P, Zabaleta-del-Olmo E, Mahtani KR, Vellinga A, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in primary care: a meta-analytic review. Ann Fam Med (2015) 13:57–82. doi: 10.1370/afm.1863

7. Kim B, Cho SJ, Lee KS, Lee JY, Choe AY, Lee JE, et al. Factors associated with treatment outcomes in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for panic disorder. Yonsei Med J (2013) 54(6):1454–62. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.6.1454

8. Barkan T, Hoerger M, Gallegos AM, Turiano NA, Duberstein PR, Moynihan JA. Personality predicts utilization of mindfulness-based stress reduction during and post-intervention in a community sample of older adults. J Altern Complement Med (2016) 22(5):390–5. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0177

9. Nyklíček I, van Son J, Pop VJ, Denollet J, Pouwer F. Does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy benefit all people with diabetes and comorbid emotional complaints equally? moderators in the DiaMind trial. J Psychosom Res (2016) 91:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.10.009

10. Nyklíček I, Irrmischer M. For whom does mindfulness-based stress reduction work? moderating effects of personality. Mindfulness (2017) 8(4):1106–16. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0687-0

11. Tovote KA, Schroevers MJ, Snippe E, Emmelkamp PMG, Links TP, Sanderman R, et al.What works best for whom? cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes. PloS One (2017) 12(6):e0179941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179941

12. Greenberg J, Datta T, Shapero BG, Sevinc G, Mischoulon D, Lazar SW. Compassionate hearts protect against wandering minds: self-compassion moderates the effect of mind-wandering on depression. Spiritual Clin Pract (Wash D C ) (2018) 5(3):155–69. doi: 10.1037/scp0000168

13. Jagielski CH, Tucker DC, Dalton SO, Mrug S, Würtzen H, Johansen C. Personality as a predictor of well-being in a randomized trial of a mindfulness-based stress reduction of Danish women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol (2020) 38:4–19. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2019.1626524

14. van den Hurk PA, Wingens T, Giommi F, Barendregt HP, Speckens AE, van Schie HT. On the relationship between the practice of mindfulness meditation and personality-an exploratory analysis of the mediating role of mindfulness skills. Mindfulness (N Y). (2011) 2:194–200. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0060-7

15. Stevenson JC, Emerson LM, Millings A. The relationship between adult attachment orientation and mindfulness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness (N Y) (2017) 8:1438–55. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0733-y

16. Garland EL, Geschwind N, Peeters F, Wichers M. Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Front Psychol (2015) 6:15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00015

17. Cifu G, Power MC, Shomstein S, Arem H. Mindfulness-based interventions and cognitive function among breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. (2018) 18:1163. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5065-3

18. Garland SN, Stainken C, Ahluwalia K, Vapiwala N, Mao JJ. Cancer-related search for meaning increases willingness to participate in mindfulness-based stress reduction. Integr Cancer Ther (2015) 14:231–9. doi: 10.1177/1534735415580682

19. Garland EL, Thielking P, Thomas EA, Coombs M, White S, Lombardi J, et al. Linking dispositional mindfulness and positive psychological processes in cancer survivorship: a multivariate path analytic test of the mindfulness-to-meaning theory. Psychooncology (2017) 26:686–92. doi: 10.1002/pon.4065

20. Cillessen L, Johannsen M, Speckens AEM, Zachariae R. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychological and physical health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology (2019) 28:2257–69. doi: 10.1002/pon.5214

21. Arimitsu K. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Self-compassion scale. Jap J Psychol (2014) 85:50–9. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.85.50

22. Matsumoto S, Akiyama T, Tsuda H, Miyake Y, Kawamura Y, Noda T, et al. Reliability and validity of TEMPS-A in a Japanese non-clinical population: application to unipolar and bipolar depressives. J Affect Disord (2005) 85(1-2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.001

23. Kijima NL, Tanaka E, Suzuki N, Higuchi H, Kitamura T. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Temperament and Character Inventory. Psychol Rep (2000) 86(3, Pt. 1):1050–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.86.3.1050

24. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini- Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatri Res (1975) 12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

25. Matsuoka K, Kim Y, Hiro H, Miyamoto Y, Fujita K, Tanaka K, et al. Development of Japanese Adult Reading Test (JART) for predicting premorbid IQ in mild dementia (Japanese). Clin Psychiatry (2002) 44(5):503–11. doi: 10.11477/mf.1405902639

26. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry (1978) 133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429

27. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1960) 23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

28. Ogawa M. A study of the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the PBI (Parental Bonding Instrument) (Japanese). Jap J Psychiatri Treat (1991) 6:1193–201. doi: 10.11501/3105318

29. Sato F, Yamaguchi H, Saito S. Validity and reliability of Japanese Version of PIL (Purpose-in-Life Test) (Japanese). Artes Liberals (1993) 52:85–97. doi: 10.15113/00013523

Keywords: psychotherapy, mindfulness, self-compassion, novelty seeking, purpose in life

Citation: Akase M, Terao T, Kawano N, Sakai A, Hatano K, Shirahama M, Hirakawa H, Kohno K and Ishii N (2020) More Purpose in Life and Less Novelty Seeking Predict Improvements in Self-Compassion During a Mindfulness-Based Intervention: The EXMIND Study. Front. Psychiatry 11:252. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00252

Received: 15 August 2019; Accepted: 16 March 2020;

Published: 03 April 2020.

Edited by:

Rakesh Pandey, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Warren Mansell, University of Manchester, United KingdomPreethi Premkumar, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Akase, Terao, Kawano, Sakai, Hatano, Shirahama, Hirakawa, Kohno and Ishii. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takeshi Terao, dGVyYW9Ab2l0YS11LmFjLmpw

Mari Akase

Mari Akase Takeshi Terao

Takeshi Terao Nobuko Kawano1,2

Nobuko Kawano1,2 Akari Sakai

Akari Sakai Koji Hatano

Koji Hatano Masanao Shirahama

Masanao Shirahama Hirofumi Hirakawa

Hirofumi Hirakawa Kentaro Kohno

Kentaro Kohno Nobuyoshi Ishii

Nobuyoshi Ishii