- 1Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Institute of Psychology, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany

- 2Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Institute of Psychology and Education, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany

- 3Department of Clinical, Neuro- & Developmental Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 4GET.ON Institute, Hamburg, Germany

Background: Farmers show high levels of depressive symptoms and mental health problems in various studies. This study is part of a nationwide prevention project carried out by a German social insurance company for farmers, foresters, and gardeners (SVLFG) to implement internet- and tele-based services among others to improve mental health in this population. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the (cost-)effectiveness of personalized tele-based coaching for reducing depressive symptom severity and preventing the onset of clinical depression, compared to enhanced treatment as usual.

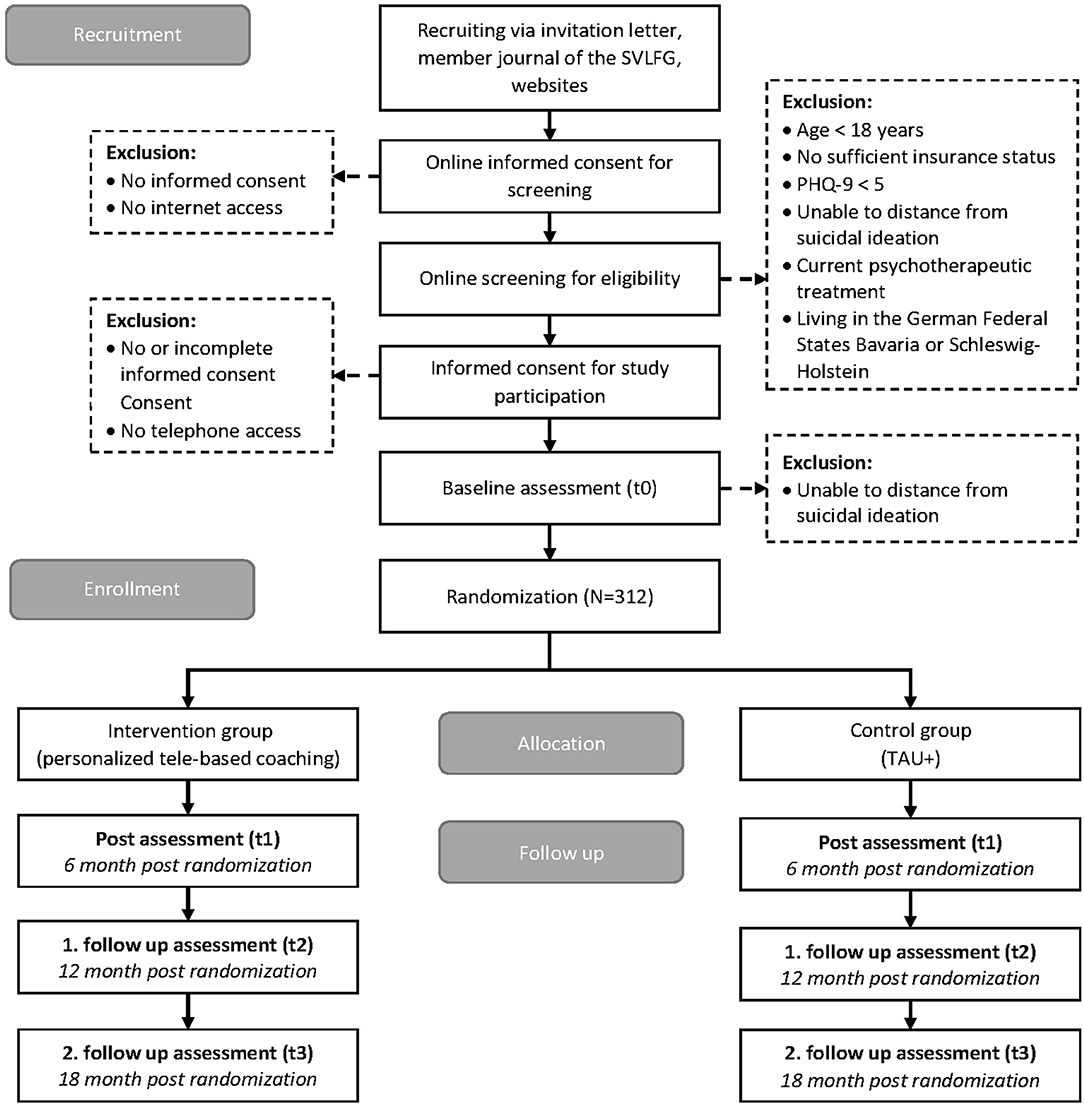

Methods: In a two-armed, pragmatic randomized controlled trial (N = 312) with follow-ups at post-treatment (6 months), 12 and 18 months, insured farmers, foresters, and gardeners, collaborating family members and pensioners with elevated depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) will be randomly allocated to personalized tele-based coaching or enhanced treatment as usual. The coaching is provided by psychologists and consists of up to 34 tele-based sessions for 25–50 min delivered over 6 months. Primary outcome is depressive symptom severity at post-treatment. Secondary outcomes include depression onset, anxiety, stress, and quality of life. A health-economic evaluation will be conducted from a societal perspective.

Discussion: This study is the first pragmatic randomized controlled trial evaluating the (cost-)effectiveness of a nationwide tele-based preventive service for farmers. If proven effective, the implementation of personalized tele-based coaching has the potential to reduce disease burden and health care costs both at an individual and societal level.

Clinical Trial Registration: German Clinical Trial Registration: DRKS00015655.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent condition with lifetime prevalence rates estimated between 10.6 and 19.8% (1). Moreover, MDD is associated with substantial individual and societal burden due to functional impairment (2), increased mortality (3) as well as high socioeconomic costs (4, 5).

Despite the availability of effective treatments like psychotherapy and psychopharmacological interventions (6, 7), depression remains under-recognized and under-treated in primary care (8). Moreover, even in a scenario of full coverage of and compliance to evidence-based treatments, estimates suggest that only approximately one-third of the total MDD-related disease burden could be averted (9, 10). Therefore, prevention of MDD evokes global interest (11). Recent meta-analytic evidence suggests that psychological interventions could prevent or at least delay the onset of MDD by targeting individuals at elevated risk (e.g., selective prevention) or individuals with subclinical depression (e.g., indicated prevention) (12).

A large population-based study on anxiety and depression showed that male farmers and workers in related occupations had the highest level of depression of all 10 occupational groups of the Classification of Occupations (e.g., armed forces, legislators/managers, professionals including teachers, technicians, craft, and trade workers) (13). The Norwegian HUNT study found a doubled risk for farm-workers compared to their non-farming siblings to report depressive symptoms (14). Risk factors for depression associated with working in agriculture include: work-related stress (15, 16), additional jobs off the farm (15) and financial instability (17) paired with attitudinal barriers for help-seeking especially in male farmers (18, 19). Considering these risk factors, effective, and accessible preventive measures for these individuals are highly warranted and have the potential to greatly improve the well-being of this vulnerable group.

Face-to-face as well as internet-based psychological interventions have been shown to be effective at treating subthreshold depression and in preventing MDD onset (12, 20–22). However, both delivery modes possess certain limitations [e.g., low participation rates (23) or less use of online services in general and more adverse attitudes toward internet use (24)]. Even though access to the internet has greatly increased in Germany over recent years, rural areas still struggle with regards to the use of internet services (24, 25). Therefore, tele-based coaching might be a feasible adjunct to existing preventive interventions for depression, especially in rural communities.

Additionally, some evidence suggests that tele-based coaching is, compared to treatment-as-usual, effective in reducing depressive symptom severity in mildly to moderately depressed individuals with between-group effect sizes ranging from 0.60 at a 4-month follow-up in an intention-to-treat sample (26) to 0.44 at 12-month follow-up based on study completer-only data (27). However, the clinical and cost-effectiveness of tele-based coaching in the prevention of MDD remains understudied.

Thus, the present trial will evaluate whether personalized tele-based coaching is (cost-)effective in reducing depressive symptom severity and preventing the onset of clinical depression. This study is embedded in an evaluation project of a nationwide rollout of preventive services called “With us in balance,” carried out by the German social insurance for farmers, foresters, and gardeners (www.svlfg.de). The project aims to implement personalized tele-based coaching and internet-based interventions in conjunction with established, on-site prevention group workshops aimed to improve mental health amongst farmers, foresters, and gardeners.

The following research questions will be investigated in this pragmatic randomized controlled trial:

- Is personalized tele-based coaching effective in reducing depressive symptom severity compared to enhanced treatment as usual (TAU+) at post-treatment (primary outcome) and follow-ups (secondary outcome)?

- Is personalized tele-based coaching effective in preventing the onset of major depressive episodes as compared to TAU+ at follow-up?

- Is personalized tele-based coaching effective in reducing the severity of various mental health outcomes (e.g., stress, anxiety, insomnia) compared to TAU+?

- Is personalized tele-based coaching preferable to TAU+ in terms of costs and utilities in reducing depressive symptom severity?

- Which variables moderate and mediate the effects of personalized tele-based coaching on mental health outcomes?

- What is the level of satisfaction with, adherence to and acceptance of personalized tele-based coaching?

- Are there reported negative effects associated with personalized tele-based coaching?

Methods and Analysis

Study Design

The study is designed as a two-armed pragmatic randomized controlled trial comparing the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a personalized tele-based coaching provided by IVPNetworks (intervention group, IG) to a control group (CG) receiving enhanced treatment-as-usual (enhanced = e-mailed psychoeducation on stress, depression and information about access to regular care, TAU+). Assessments will take place at baseline (T0), post-treatment (6-month, T1) and at follow-ups at 12-month (T2) and 18-month (T3) after enrolment.

This clinical trial has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg (No. 345_18 B) and is registered in the German clinical trial register under DRKS00014000. The results will be reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 Statement and extension for reporting pragmatic trials (28–30).

Participants and Procedure

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study participants

We will include farmers, foresters, and gardeners in Germany who (a) are insured by the SVLFG, (b) are an entrepreneur, collaborating spouse, assisting family member or pensioner, (c) are 18 years or older, (d) show elevated symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 5), (e) have internet (for online assessments) and telephone access (for coaching), and (f) are willing to provide informed consent. Persons will be excluded if they (a) currently receive psychotherapy or (b) are not willing to sign a non-suicide contract in case of suicidal ideation as indicated by a score of one or greater on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) item 9 (“I feel I would be better off dead”) or a PHQ-9 total score of 20 or greater, or (c) primarily live in the German Federal States Bavaria or Schleswig-Holstein, since national roll-out into routine care started in these two states. As this is a pragmatic trial, we did not exclude comorbidities and current medication usage.

IVPNetwork coaches

Written informed consent to participate in online assessments will be obtained from coaches assigned to study participants. There are no specific eligibility criteria for participating coaches. Coaches are either self-employed or employed by IVPNetworks.

Recruitment

Invitation letters including information about the study procedures are sent to 120,000 randomly selected policyholders via postal mailings by the insurance company. The study is also listed on associated websites and in the member journal of the SVLFG (reaching 1.3 million policyholders). Interested individuals can respond to the study invitation via mail, e-mail, fax, and/or telephone, or can directly access the screening assessment through a URL or QR-Code. The study flow is visualized in Figure 1.

Assessment of Eligibility and Randomization

Study eligibility is assessed with an online screening questionnaire. Persons who fulfill the inclusion criteria will receive detailed study information by e-mail along in addition to information on data security and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. After providing informed consent, participants will be invited to complete the baseline assessment (T0). If any of the inclusion criteria are not fulfilled but the person has a valid insurance status, the person will be redirected to the SVLFG call center for preventive services.

Randomization will take place at an individual level. Participants will be randomly allocated to the intervention or control condition consecutively after completing baseline assessment. A randomization list was created before the start of the study with the web-based program Sealed Envelope (www.sealedenvelope.com) by using permuted block randomization with randomly arranged block sizes (4, 6, 8, 12) and an allocation ratio of 1:1. A person not otherwise involved in the study will independently carry out the randomization procedure. Study participants cannot be blinded in this trial design but data collectors will be blinded to group allocation. The coaches providing the tele-based coaching are aware of treatment allocation; however, the coaches are not otherwise involved in the study. Participants will be informed about group allocation via e-mail.

Intervention

All participants in the study will have unrestricted access to treatment-as-usual (e.g., general practitioner). The German S3-Guideline/National Disease Management Guideline Unipolar Depression (31) recommends a stepped care model in which more intensive treatments (i.e., cognitive behavioral therapy, antidepressant medication) are only provided if depressive symptoms intensify (i.e., diagnosed major depressive disorder). TAU was not protocolized in this pragmatic trial but will be monitored with the TiC-P (see Assessments) in order to provide an accurate description of the TAU utilized.

Intervention Condition

The personalized tele-based coaching is offered by IVPNetworks, which is a provider of integrated care in Germany. As evaluator, the study team has no influence on the design and content of the intervention. Even though the tele-based intervention does not focus on depression specifically but more general on mental health problems, it will be evaluated as part of a depression prevention program.

Participants assigned to the intervention group are registered with their contact details on the IVPNetworks management and documentation platform (IVPnet 2.0., www.ivpnet.de). A case manager assigns participants to their personal coach before the coach schedules the first session. The coaching consists of three major phases. (1) A beginning phase in which the first coaching session serves as an assessment of the participants' individual situation and provides time for mutual goal setting for the coaching. The individual goals guide the coaching process and are used to monitor participants' progress. Furthermore, building of a working alliance is emphasized in this first phase. (2) In the working phase, the coaching is intended to support participants in recognizing and understanding conflict patterns so that they can effectively cope with them by activating their own resources. Thus, the coaching focuses on the individual participant's personal situation and stressors (e.g., financial burden, family problems, work-related stress). (3) In the final phase of the coaching, the focus is on transferring learnt skills to everyday life and if needed further supporting offers (e.g., support groups or on-site group offers) are discussed and initiated to maintain coaching effects.

Personalized coaching implies that there are no fixed procedures or standardized manuals for the individual coaching process. Methods used during the coaching vary depending on the coach's therapeutic background. Coaches are qualified psychologists with at least a master's degree in psychology and completed a training in cognitive behavioral therapy, systemic therapy, psychodynamic therapy, hypnotherapy or other therapeutic trainings. All coaches, presumably 20–30, are managed by IVPNetworks and are either self-employed or employed by IVPNetworks. Licensed psychotherapists are available for supervision at any time. Furthermore, prior to interacting with any study participant, the coaches receive an introduction into common problems faced by farmers, foresters, and gardeners. The tele-based coaching intervention comprises a maximum of 34 sessions lasting for 25 or 50 min each over a 6 months period (maximum 850 min in total). The coaching duration and frequency are adapted to the participants' needs based on the individual coach's assessment. Theoretically, the coaching can be prolonged up to 9 months (resulting in up to an additional 150 min) after a new needs assessment has been done. If indicated, participants are supported in finding on-site social and health care services to complement the tele-based coaching (e.g., socioeconomic consultants, agricultural family counseling).

Alternatively, on-site coaching can be arranged if a participant no longer prefers tele-based coaching. In the case that a participant's depressive symptoms worsen at any time during the coaching, the participant will be stabilized and further supporting steps are arranged.

Control Condition

Participants in the control group (enhanced treatment as usual, TAU+) will receive psychoeducation materials via e-mail. Moreover, they will receive a link to an audiobook on how to deal with stress as well as a link to a platform for preventive services (https://17358.zentrale-pruefstelle-praevention.de/kurse/) in routine care in order to facilitate access to service use.

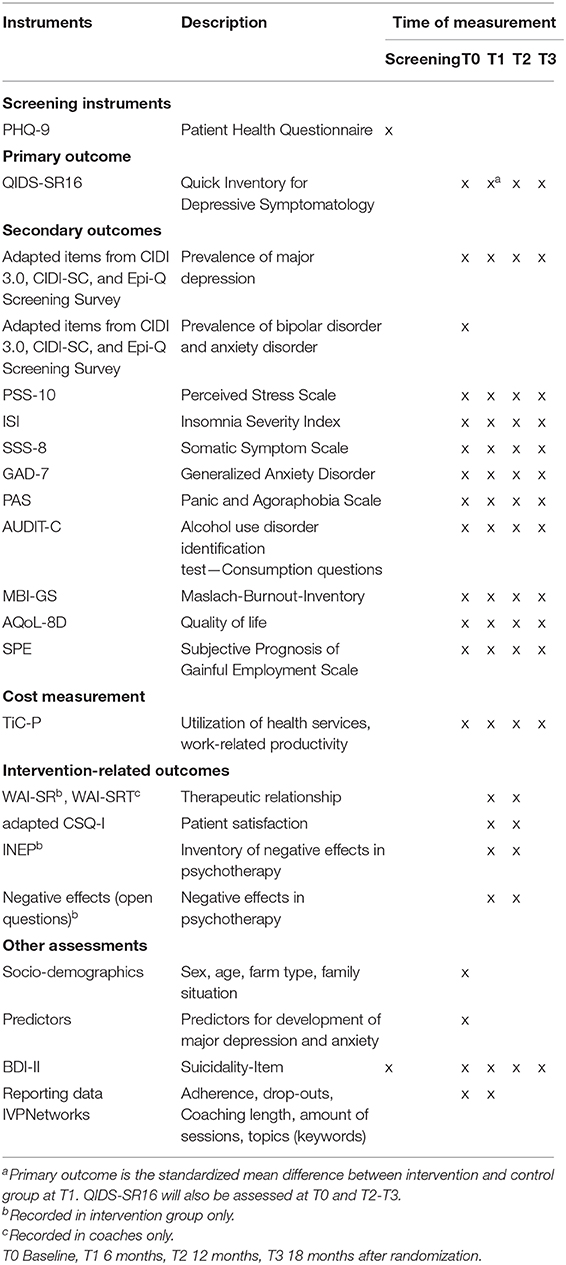

Assessments

Assessments at screening, baseline (T0), post-treatment (T1), and follow-up (T2–T3) will be conducted via a secured online platform (www.unipark.de). For an overview of instruments, see Table 1. Participants in both study conditions will receive €15 for each completed post-treatment or follow-up assessment as an incentive to continue study participation, resulting in a total of €45 for study completion.

Screening

The preliminary screening assesses sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, gender, residence, employment relationship, insurance status), current psychotherapy status and depressive symptomology to validate eligibility for participation.

Depressive symptomology is assessed using the German Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (32). The screening inventory consists of nine items on a 4-point-scale with a rating scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = “not at all,” 1 = “several days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” 3 = “nearly every day”) with each item assessing one symptom criterion domain of MDD. Total score ranges from 0 to 27 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Scores from 0 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and 20 to 27 indicate minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression severity, respectively (33). An additional item assesses severity of daily life limitations associated with depressive symptoms. The computerized version of the PHQ-9 (α = 0.88) and the paper-pencil version (α = 0.89) show equally high internal consistency (34).

Additionally, the suicide item of BDI-II (35) will be applied to screen for suicidal ideation if the suicidal item of PHQ-9 is greater than or equal to one. Participant's contact information is recorded in order to monitor suicidal ideation independent of eligibility for study participation. Lastly, to better understand recruitment tactics, participants are asked which recruitment activity made them aware of the study.

Outcome Measurements

Primary outcom

Depressive symptom severity at post-treatment (T1). Depressive symptom severity (primary outcome) at post-treatment (T1), is assessed with the German Version of the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomology (QIDS-SR16) (36). With 16 items (4-point-scale ranging between 0 and 3), the self-report inventory covers all nine DSM-5 symptom criterion domains of MDD. When analyzing scores, only the highest rated item for sleep, weight, and psychomotor activity is included leading to total scores ranging between 0 and 27, with a higher score indicating more depressive symptom severity. Scores between 0 and 5, 6 and 10, 11 and 15, 16 and 20, and >20, indicate normal health status, or mild, moderate, severe, or very severe depressive symptom severity, respectively (36). Compared to current and lifetime diagnosis based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID), the QIDS-SR16 proved to be a reliable screening instrument for a diagnosis of clinical depression (37) with good in (α = 0.86) (36).

Secondary outcomes

Depressive symptom severity at follow-up (T2 - T3). Additionally, depressive symptom severity at follow-up assessments at 12-months (T2) and 18-months (T3) will be measured with the QIDS-SR16.

Onset of ICD-10 major depressive episode and bipolar disorder. The onset of major depressive episodes and bipolar disorder, are assessed with adapted items from the web version of the Composite International Diagnosis Interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) and Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) (38) and the Epi-Q Screening Survey (39) as used in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project (40). Bipolar disorder will be assessed at baseline (T0), while depressive episodes will be assessed at all time points (T0–T3).

In addition, the QIDS-SR16 is used to identify possible clinically relevant cases of depression. A total score of 13 and greater is defined as cut-off for possible cases of clinical depression for all time points (T0–T3). This value was selected as it yield best results for sensitivity (76.5%) and specificity (81.8%) and resulted in a correct classification of over 80% of participants (37).

Perceived stress. Perceived stress is assessed with the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) in which ten items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (41, 42). The German Version of the perceived stress scale assess perceived stress in the past week and is reported with good internal consistency (α = 0.84) (42, 43).

Insomnia severity. The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (44) is used to measure insomnia severity in participants. The questionnaire has been validated to identify cases of clinical insomnia. The ISI has adequate discriminative validity of the individual items and a high internal consistency (α = 0.90–0.92). The self-report questionnaire consists of seven items on a 5-point Likert scale (45, 46). Examination of the German version of the ISI in three cross-sectional studies in different target groups revealed acceptable to good internal consistency (α = 0.76–0.81) (47)

Somatic symptom burden. Somatic symptom burden will be assessed with the Somatic Symptom Scale, the short version of the PHQ-15 questionnaire (48). In 8 items (5-point Likert scale), eight symptoms common in primary care and relevant for mental health are assessed (gastrointestinal symptoms, pain, fatigue, cardiopulmonary symptoms). Additionally, a study in a German sample of participants reported good reliability (α = 0.81) and correlation with depression and other health outcomes (49).

Generalized anxiety disorder. The GAD-7 (50), a 7-item self-report questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale, is used for screening and severity measuring of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Previous studies have found that the internal consistency of this instrument is only slightly lower in a German sample (α = 0.89) (51) compared to a sample in the United States (α = 0.92) (50). The GAD-7 is considered a reliable screening instrument for GAD (50, 51)

Additionally, the presence of GAD at baseline is assessed with adapted items from the Composite International Diagnosis Interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0), Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) (38) and the Epi-Q Screening Survey (39).

Panic and agoraphobia scale. The panic and agoraphobia scale (52, 53) will be assessed to measure severity of panic and agoraphobic symptoms.

Twelve items with a 5-point Likert scale assess five individual subscales: regarding panic attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, anticipatory anxiety, daily life limitations, and health concerns. An additional item (6-point Likert scale) differentiates between unexpectedness vs. expectedness of panic attacks and is not included in the calculation of the total score (52). Additionally, situations in which individuals believe panic attack are likely to occur are recorded. Good internal consistency is reported for the panic and agoraphobia scale (α = 0.88) (52).

Alcohol consumption. Alcohol consumption will be assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) (54). As previous research has shown, the first three items of the AUDIT can be used as a reliable stand-alone screening of risky alcohol consumption (AUDIT-C) (55). Good internal consistency is reported for the German version of the AUDIT-C (α = 0.80) (56). In the present study, the German version of the AUDIT-C, as distributed by the German Medical Association (https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/AlkAUDITCFragebogen.pdf) is administered.

Burnout. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (57) is used to record burnout symptomology. The Inventory assess the three dimensions of burnout including “Emotional Exhaustion,” “Cynicism,” and “Professional Efficacy” with 22 items and a 7-point Likert scale. The reliability (α = 0.71–0.88 for subscales) has been proven acceptable in cross-national comparison (58)

Quality of life. The self-report questionnaire Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL-8D) will be used to assess health-related quality of life. With 35 items (5-point Likert scale) three physical dimensions (“independent living,” “pain,” and “senses”) as well as the five psycho-social dimensions (“mental health,” “happiness,” “coping,” “relationships,” and “self-worth”) are assessed, yielding two distinct sum scores (59). The questionnaire is reported with excellent reliability (α = 0.96) and good psychometric properties (59).

Subjective capacity to work. The participants subjective capacity to work will be measured using the 3-item Subjective Prognosis of Gainful Employment Scale (60). The short self-report scale showed high internal consistency (Guttman scaling: rep = 0.99) and validity for assessment of subjective endangerment and prognosis of capacity to work (60).

Cost measures. For cost evaluation, the German version of the Dutch cost questionnaire “Trimbos Institute and Institute of Medical Technology Questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric Illness” (TiC-P) (61) was adapted to specifically assess farmers, foresters, and gardeners. The self-report questionnaire assesses direct medical costs (e.g., use of health care services, visits to the general practitioner, use of medications, sessions with psychotherapists or psychiatrists, inpatient hospital care), direct non-medical costs (e.g., patient and family costs), and indirect costs (e.g., productivity losses due to absenteeism and presenteeism). The German version has been widely used in health economic outcome evaluations alongside clinical trials (62–65).

Intervention-related outcomes

As part of the evaluation, the process and content of the tele-based coaching will be documented and reported in detail during the intervention phase and at the end of the coaching (e.g., amount of completed sessions and their duration, common topics in coaching sessions, compliance of participants, referrals to onsite services). The qualification of coaches will be assessed with a sociodemographic questionnaire. In addition, to gain deeper insights the coaching procedure and methods, interviews in a subsample of coaches will be conducted.

Intervention satisfaction. At post-treatment (T1) and the first follow-up (T2) participants' satisfaction with the personalized tele-based coaching is measured using a German Version of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8, adapted version for internet interventions: CSQ-I) (66–68). In the IG, the CSQ-I will be adapted for telephone coaching (the original CSQ-8 is validated only in face-to-face contexts). The CSQ-8 as well the CSQ-I consist of eight items (4-point Likert scale) and report a high internal consistency (α = 0.87 and 0.93) (67, 68). An adapted version of the CSQ-I will be used for the assessment of participant's satisfaction with the information material received in the CG.

Working alliances. The therapeutic alliance between participants and coaches will be addressed with the German short version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-SR) (69). The three subscales “agreement on tasks,” “agreement on goals,” and “development of an affective bond” are assessed with 12 items on a 5-point Likert scale. The internal consistencies for the German version are between α = 0.81 and α = 0.91 for the subscales and between α = 0.90 and α = 0.93 for the total score (69, 70). The WAI-SR will be applied in the IG at T1 and T2, respectively. Furthermore, the coaches will be asked to complete the 10-item therapist version (WAI-SRT, developed by Adam O. Horvath, wai.profhorvath.com) at the same time. This approach provides the opportunity to evaluate the therapeutic relationship from two different points of view (i.e., the participant and the coach) and to report a differentiated and comprehensive picture of the experienced working alliance. The WAI-SR and the WAI-SRT were adapted for the current trial to assess coaching in a prevention setting. The items were adjusted to refer to “coaches” instead of therapists and to “telephone coaching” instead of therapy.

Side effects of the intervention. Side effects of the intervention will be assessed with a version of the Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects of Psychotherapy (71) adapted to the tele-based setting of the intervention. This 22-item questionnaire assesses whether any negative changes were experienced during or after the tele-based coaching that are causally attributed to the intervention. Furthermore, open-ended questions will be included for qualitative assessments of possible negative side effects of the personalized tele-based coaching. Symptom deterioration will be assessed using the Reliable Change Index based on QIDS at post-treatment and follow-ups.

Other assessments

Covariates. Variables that could potentially moderate the expected effects, including sociodemographic as well as information about the agricultural business (e.g., farm size, area cultivated, number of workers) and the overall family and work situation (e.g., financial situation, number of relatives living and working together, general work load), will be assessed at baseline (T0).

Furthermore, we will explore variables associated with depression (72–74) or that have shown to predict treatment outcome for depression and anxiety (75). Clinical characteristics that shall be investigated include depressive symptom severity (76), lifetime history of MDD or any mental disorder (77–80), past or present suicidal thoughts or plans (35, 79–81), experience with psychotherapy (82), treatment motivation (83), treatment preference (84–86), family history of mental illness (77, 87–89) (chronic) illness, self-perceived health and energy (61, 78, 90–95), traumatic or adverse childhood experience (abuse, parental death, or divorce) (80, 87, 88, 96–101), body satisfaction and eating disorder (94, 102–107), sleep quality (44, 90, 94, 108, 109), and accidents and injuries (15, 110).

Personality characteristics include smoking (82, 94, 111), alcohol consumption and drug use (77, 91, 94), relationship quality (91, 112, 113) (partner) violence experience (96, 112, 114–116), threatening life events in the past 12 months (79, 80, 91, 117–120), physical activity and sedentary behavior (94, 106, 111, 121–123), stress (15, 43, 79, 124, 125), need for affect, emotional avoidance (126–128), anxiety sensitivity (129–131), sense of mastery, internal locus of control (79, 132–135), worry (136–138), self-worth (100, 104, 139–141), and loneliness (142–145).

Sociodemographic variables that shall be examined include age (76, 77, 111, 146, 147), sex (82, 92, 104, 110, 111, 117, 118, 146–149), origin country (148), migration (150–153), ethnicity, minority (111, 147, 154), discrimination (103, 155, 156), education level (92, 96, 109–111, 148), employment status (88, 111, 125), relationship status, living situation (88, 92, 111, 146), parenthood (82), caregiving living situation (94, 157, 158), economic status (90, 91, 118, 159), and social status (94, 160, 161).

Safety monitoring. Suicidal ideation will be screened in all assessments using PHQ-9 (screening) or QIDS-SR16 (T0–T3). If the suicide item of PHQ-9 or QIDS-SR16 has a score of one or greater, the BDI-II (35) suicide item will additionally be assessed.

A score of one or greater on the BDI-II suicide item or a PHQ-9 score of 20 greater / QIDS-SR16 score of 16 or greater [indicating severe depressive symptoms (36)] will result in a standardized suicide protocol. Participants will receive e-mails with detailed information on 24/7 health services and are advised to seek professional help if symptoms persist or increase. The wording of this information is adapted to the severity of the indicated suicidality as given in the BDI-II Item or PHQ-9/QIDS-16 scores. In cases of a BDI-II scores of 2 or 3, and/or severe depressive symptoms, the persons are called by a psychologist or a psychotherapist (licensed or in training) within 3 days for evaluation of suicidal ideation severity and dissociation. The suicide protocol is developed and closely monitored by a licensed psychotherapist.

As part of the suicide protocol, at screening and baseline, all participants with suicidal ideation and/or severe depressive symptoms are asked to return a signed non-suicide contract if they are able to distance themselves from suicidal ideation (inclusion criteria). Participants are reminded that the coaching is not designed for persisting suicidal ideation and are provided necessary resources (as discussed previously).

Statistical Analyses

Sample Size/Power Calculation

The estimated effect size of d = 0.35 used for this study is based on the findings of the meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al. (20) regarding the effect of psychological interventions on subclinical depression (g = 0.35, 95%-CI: 0.23–0.47) and effect sizes commonly observed in studies on health outcomes (162).

Power calculation conducted with G*Power (Version 3.1.9.2) for a two-sided T-Test (α = 0.05, β = 0.80, d = 0.35) resulted in N = 260. In order to account for dropouts during the 18-month follow-up, we calculated an extra 20% of participants, taking into account reported dropout rates between 20 and 23% from studies with telephone coaching in different settings (27, 163). Accounting for drop-outs resulted in the final N = 312.

Clinical Analyses

Clinical analysis will be performed using R statistic software (164). All statistical analyses will be performed based on intention-to-treat principle. Missing data will be imputed using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo multivariate imputation algorithm. Group difference between pre- (T0) and post-assessment (T1) in the primary outcome will be analyzed using generalized linear modeling adjusting for baseline depressive symptom severity. Within- and between-group Cohen's d effect sizes [and their 95% CIs according to Hedges and Olkin (165)] controlling for baseline data (i.e., calculating change scores divided by the pooled standard deviation of change scores) will be reported. Improvements in the primary outcome at individual level will be examined by assessing the number of participants who displayed a treatment response defined by the Reliable Change Index as proposed by Jacobson and Truax (166) and a close-to-symptom-free status (e.g., QIDS ≤ 5). Close-to-symptom-free status will only be evaluated in the subgroup of participants who reported at least mild depressive symptom severity at baseline. Group differences in depression onset will be assessed using Poisson regression models in the subset of participants who did not meet the diagnostic depression status at baseline as assessed with the self-report web version of the adapted CIDI. Group differences in diagnostic status in the subset of participants who did not meet depression diagnosis criteria at baseline will be analyzed using logistic regression models. In sensitivity analyses, we will assess the influence of objective measures, such as therapeutic background of coaches and length of coaching, on intervention outcomes. Other secondary outcomes like anxiety, perceived stress, sleep quality, and quality of life will be analyzed as the primary outcome. Additionally, moderation and mediation analyses will be performed.

Economic Evaluation

We will conduct and report the health economic evaluation in agreement with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement (167) and the guidelines from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) (168). The health-economic evaluation will involve a combination of a cost-effectiveness analysis and a cost-utility analysis (169). The economic evaluation will be performed from a societal perspective and from the perspective of the social insurance company with a time horizon of 18 months. In the cost-effectiveness analysis, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) will be calculated by dividing incremental costs (e.g., cumulative per-participant costs) by the unit of effect gained (e.g., reliably improved case or quality-adjusted life years based on the AQoL-8D). The corresponding equation is ICER = (CostsIG – CostsCG) / (EffectsIG – EffectsCG), with IG representing the intervention group and CG the control group (169). To handle sampling uncertainty, we will bootstrap the seemingly unrelated regression equations model (SURE model) to generate 2,500 simulations of cost and effect pairs while allowing for correlated residuals of the cost and effect equations and adjusting for potential confounding variables (170). Based on the bootstrapped SURE model, bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals will be obtained for incremental costs and effects while 95% confidence intervals around ICERs will be obtained by the bootstrap acceptability method as proposed by Glick et al. (171). The bootstrapped cost and effect pairs will be plotted in a cost-effectiveness plane. The cost-effectiveness plane is used to visually represent the differences in costs and health outcomes between the tele-based coaching and TAU+ in two dimensions. Health outcomes (effects) are plotted on the x-axis and costs on the y-axis. TAU+ is plotted at the origin, and so the x and y values represent incremental health outcomes and incremental costs vs. routine care. The cost-effectiveness plane is divided into four quadrants: the north-east (NE) quadrant, in which new interventions generate more health gains but at higher costs; the south-east (SE) quadrant, in which new interventions costs less and create higher health effects (e.g., the new intervention dominates the alternative); the north-west (NW) quadrant, in which new interventions produce less health effects at higher costs (e.g., the new intervention is dominated by the alternative) and the south-west (SW) quadrant, in which new interventions costs less but also generate less health effects (169). To disclose the probability that the intervention is cost-effective for a range of willingness-to-pay ceilings (e.g., the maximum a decision maker is willing to pay for a unit of effect), the bootstrapped cost and effect pairs will also be shown in a cost-effective acceptability curve (172). To test the robustness of the base-case findings, multi-way sensitivity analyses will be completed. The analysis will be performed using StataCorp (173).

Discussion

This study will be the first pragmatic randomized controlled trial to examine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of personalized tele-based coaching for farmers, foresters, and gardeners in Germany. The intervention is meant to prevent clinical depression and reduce depressive symptom severity in farmers, foresters, and gardeners.

The study is embedded in a large scale nationwide prevention project which does not only aim at the evaluation of the (cost-)effectiveness but also target nation-wide implementation at the same time. Stepwise national rollout of the intervention runs parallel to this randomized controlled trial. Confounding is controlled for via recruitment activities and eligibility criteria. Therefore, if proven effective, the personalized tele-based coaching will be sustainably introduced into regular care in Germany, which can be seen as a strength of this trial since most studies in the field of depression prevention lack a sustainable integration in the health care system (174, 175). Study findings can therefore directly contribute to improving the preventive service of the SVLFG.

Another major strength of tele-based coaching compared to face-to-face psychological interventions or mental health workshops is that delivery over the telephone greatly reduces the time and effort associated with people affected in the rural area (e.g., no travel time to visit a therapist).

Some limitations of the study should also be mentioned. First, the assumed advantage of tele-based coaching compared to internet-based interventions that telephone coaching does not rely on internet access and might therefore be more accessible in rural areas, cannot be verified with this study. Participants are only enrolled in the study if they are able to complete the online-based assessments and therefore require internet access for study participation. Nevertheless, participants in IG and CG will be asked about their preferences for treatment of mental health problems (e.g., face-to face, online, telephone, combined delivery modes) in order to get first insights in setting preferences.

Second, the operationalization of the personalized tele-based coaching intervention itself is difficult. As Ammentorp et al. (176) claims, detailed descriptions of coaching interventions and methods used are crucial in order to improve the field of life coaching research and its impact on (mental) health outcomes. Although this intervention is highly personalized with regard to contact duration, frequency, and covered coaching topics, we will be able to give a detailed and comprehensive description of the intervention by routine data documentation in addition to data collected from coaches and participants. Thereby, we will add to this growing field of research by providing strongly needed evidence from a randomized controlled trial regarding preventive coaching interventions. The information gained could also be used in the development of standardized coaching manuals.

Third, as mentioned earlier, previous research does not provide profound evidence about estimates regarding effect sizes and drop-out rates. We accounted for possible drop out by increasing the target sample by 20%. Nevertheless, we are at a risk to over- or underestimate dropout. Reporting effect sizes and drop-out rates will help researchers calculate target sample sizes in future studies.

To sum up, this pragmatic trial leads to a robust estimation of the (cost-)effectiveness of personalized tele-based coaching in the target population. Therefore, results from the study can be generalized to farmers, foresters, and gardeners in Germany and comparable coaching situations.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg (no. 345_18 B). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Trial Status

The recruitment of participants started in December 2018 and has been finished in April 2019 while the first draft of this paper was composed. Data collection is still ongoing and no analyses have been performed, yet.

Author Contributions

DE, HB, and MB obtained funding for this study. DE, IT, CB, JT, and HB contributed to the study design. CB contributed to the design of the economic evaluation study. JT drafted the manuscript, supervised by CB, and is responsible for recruitment and coordination of the trial. JF and LB contributed to the acquisition of data and managing of recruitment. IT and CB are supervising the recruitment and trial management. All authors provided critical revision of the article and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The German insurance company SVLFG provided a financial contribution to the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and Ulm University as expense allowance. SVLFG had no role in study design, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript. SVLFG will not be involved in data collection, analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of future papers regarding the study.

Conflict of Interest

DE has served as a consultant to/on the scientific advisory boards of Sanofi, Novartis, Minddistrict, Lantern, Schoen Kliniken, Ideamed, and German health insurance companies (BARMER, Techniker Krankenkasse) and a number of federal chambers for psychotherapy. DE and MB are stakeholders of the Institute for health training online (GET.ON), which aims to implement scientific findings related to digital health interventions into routine care. HB reports to have received consultancy fees and fees for lectures/workshops from chambers of psychotherapists and training institutes for psychotherapists in the e-mental-health context. IT reports to have received fees for lectures/workshops in the e-mental-health context from training institutes for psychotherapists. She is implementation lead and project lead for the EU-project ImpleMent. All at the Institute for health training online (GET.ON).

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Friederike Dietz for the creation of the Unipark surveys and the support in data security questions. Further, authors thank Sarah Banellis, Merle Bloom, Hanna Böckeler, Albina Chafisuf, and Tomris Ohloff for their engagement in enrolling and supporting the participants throughout the study and Lukas Fuhrmann and Marvin Franke for carrying out the randomization. Authors thank the IVPNetworks staff who provided details on their intervention and Allison Grace for proofreading the manuscript as well.

Abbreviations

AQoL-8D, Assessment of Quality of Life; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test—Consumption Questions; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; CG, control group; CIDI, Composite International Diagnosis Interview; CSQ, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; ICER, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IG, intervention group; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; MDD, Major depressive disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; QIDS-SR16, Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomology; SVLFG, Social Insurance for Agriculture, Forestry and Horticulture; TAU, Treatment as usual; TiC-P, Trimbos Institute and Institute of Medical Technology Questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric Illness; WAI, Working Alliance Inventory.

References

1. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

2. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

3. Gilman SE, Sucha E, Kingsbury M, Horton NJ, Murphy JM, Colman I. Depression and mortality in a longitudinal study: 1952-2011. CMAJ. (2017) 189:1304–10. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170125

4. Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. (2015) 76:155–62. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298

5. Vos T, Haby MM, Barendregt JJ, Kruijshaar M, Corry J, Andrews G. The burden of major depression avoidable by longer-term treatment strategies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004) 61:1097–103. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1097

6. DGPPN, BÄK KBV, AWMF (Hrsg.) für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression. S3-AWMF-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression – Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Version 5. (2015). doi: 10.6101/AZQ/000364

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in Adults: Recognition and Management. Clin Guidel 90. (2009) Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 (accessed July 17, 2019).

8. Lotfi L, Flyckt L, Krakau I, Mårtensson B, Nilsson GH. Undetected depression in primary healthcare: occurrence, severity and co-morbidity in a two-stage procedure of opportunistic screening. Nord J Psychiatry. (2010) 64:421–7. doi: 10.3109/08039481003786378

9. Andrews G, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Corry J, Lapsley H. Utilising survey data to inform public policy: comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders Record Status Study population. Br J Psychiatry. (2004) 184:526–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.526

10. Chisholm D, Sanderson K, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Saxena S. Reducing the global burden of depression: population-level analysis of intervention cost-effectiveness in 14 world regions. Br J Psychiatry. (2004) 184:393–403. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.393

11. Muñoz RF, Cuijpers P, Smit F, Barrera AZ, Leykin Y. Prevention of major depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2010) 6:181–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132040

12. van Zoonen K, Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Smit F, Reynolds CF, Beekman AT, et al. Preventing the onset of major depressive disorder: a meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Int J Epidemiol. (2014) 43:318–29. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt175

13. Sanne B, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Moen BE, Tell GS. Occupational differences in levels of anxiety and depression: The Hordaland Health Study. J Occup Environ Med. (2003) 45:628–38. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000069239.06498.2f

14. Torske MO, Bjørngaard JH, Hilt B, Glasscock D, Krokstad S. Farmers' mental health: a longitudinal sibling comparison - The HUNT study, Norway. Scand J Work Environ Heal. (2016) 42:547–56. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3595

15. Onwuameze OE, Paradiso S, Peek-Asa C, Donham KJ, Rautiainen RH. Modifiable risk factors for depressed mood among farmers. Ann Clin Psychiatry. (2013) 25:83–90.

16. Logstein B. Predictors of mental complaints among norwegian male farmers. Occup Med. (2016) 66:332–7. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqw019

17. Simkin S, Hawton K, Fagg J, Malmberg A. Stress in farmers: a survey of farmers in england and wales. Occup Environ Med. (1998) 55:729–34. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.11.729

18. Judd F, Jackson H, Fraser C, Murray G, Robins G, Komiti A. Understanding suicide in Australian farmers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2006) 41:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0007-1

19. Hull MJ, Fennell KM, Vallury K, Jones M, Dollman J. A comparison of barriers to mental health support-seeking among farming and non-farming adults in rural South Australia. Aust J Rural Health. (2017) 25:347–53. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12352

20. Cuijpers P, Koole SL, van Dijke A, Roca M, Li J, Reynolds CF, III. Psychotherapy for subclinical depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2014) 205:268–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138784

21. Ebert DD, Cuijpers P, Muñoz RF, Baumeister H. Prevention of mental health disorders using internet- and mobile-based interventions: a narrative review and recommendations for future research. Front Psychiatry. (2017) 8:116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00116

22. Sander L, Rausch L, Baumeister H. Effectiveness of internet-based interventions for the prevention of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment Heal. (2016) 3:e38. doi: 10.2196/mental.6061

23. Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Van Rooy MJ. Recruiting participants for interventions to prevent the onset of depressive disorders: possibile ways to increase participation rates. (2010) 10:181. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-181

24. Initiative D21. D21-Digital-Index 2018/2019. (2019). Available online at: https://initiatived21.de/publikationen/d21-digital-index-2018-2019/ (accessed May 7, 2019).

25. Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur. Aktuelle Breitbandverfügbarkeit in Deutschland (Stand Mitte 2018). (2018). Available online at: https://www.bmvi.de/SharedDocs/DE/Publikationen/DG/breitband-verfuegbarkeit-mitte-2018.html?nn=12830 (accessed May 7, 2019).

26. Lerner D, Adler DA, Rogers WH, Chang H, Greenhill A, Cymerman E, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a telephone depression intervention to reduce employee presenteeism and absenteeism. Psychiatr Serv. (2015) 66:570–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400350

27. Schröder S, Fleckenstein J, Wunderlich M. Effektivität eines telefonbasierten coaching-programms für patienten mit einer depressiven erkrankung. Monit Versorgungsforsch. (2017) 10:65–8. doi: 10.24945/MVF.04.17.1866-0533.2022

28. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. (2010) 340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332

29. Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. (2008) 337:a2390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390

30. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. (2010) 340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869

31. Bundesärztekammer B, Fachgesellschaften. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Unipolare Depression. (2015). Available online at: www.depression.versorgungsleitlinien.de (accessed May 31, 2019).

32. Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. (2004) 81:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8

33. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

34. Erbe D, Eichert HC, Rietz C, Ebert DD. Interformat reliability of the patient health questionnaire: validation of the computerized version of the PHQ-9. Internet Interv. (2016) 5:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.006

35. Kühner C, Bürger C, Keller F, Hautzinger M. Reliabilität und Validität des revidierten Beck-Depressionsinventars (BDI-II). Befunde aus deutschsprachigen Stichproben. Nervenarzt. (2007) 78:651–6. doi: 10.1007/s00115-006-2098-7

36. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2003) 54:573–83. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8

37. Lamoureux BE, Linardatos E, Fresco DM, Bartko D, Logue E, Milo L. Using the QIDS-SR16 to identify major depressive disorder in primary care medical patients. Behav Ther. (2010) 41:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.12.002

38. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2004) 13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168

39. Kessler R, Farley P, Gruber M, Harshaw Q, Jewell M, Sampson N, et al. Concordance of computerized self-report measures of DSM-IV-TR mood and anxiety disorders compared to gold standard clinical assessments in primay care. Value Heal. (2010) 13:118. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)72567-5

40. Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Ebert DD, et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders WHO WMH-ICS collaborators. Am Psychol Assoc. (2018) 127:623–38. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362

41. Naik AD, White CD, Robertson SM, Armento MEA, Lawrence B, Stelljes LA, et al. Behavioral health coaching for rural-living older adults with diabetes and depression: an open pilot of the HOPE Study. BMC Geriatr. (2012) 12:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-37

42. Reis D, Lehr D, Heber E, Ebert DD. The German Version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): evaluation of dimensionality, validity, and measurement invariance with exploratory and confirmatory bifactor modeling. Assessment. (2017) 26:1246–59. doi: 10.1177/1073191117715731

43. Klein EM, Brähler E, Dreier M, Reinecke L, Müller KW, Schmutzer G, et al. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale – psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9

44. Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. (2001) 2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4

45. Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. (2011) 34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601

46. Gagnon C, Belanger L, Ivers H, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. (2013) 26:701–10. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130064

47. Gerber M, Lang C, Lemola S, Colledge F, Kalak N, Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al. Validation of the German version of the insomnia severity index in adolescents, young adults and adult workers: results from three cross-sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:174. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0876-8

48. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:258–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008

49. Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, Spangenberg L, Zenger M, Brähler E, et al. The Somatic Symptom Scale−8 (SSS-8). JAMA Intern Med. (2014) 174:399–407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179

50. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

51. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

52. Bandelow B. Assessing the efficacy of treatments for panic disorder and agoraphobia. II. The Panic and Agoraphobia Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (1995) 10:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199506000-00003

53. Bandelow B, Hajak G, Holzrichter S, Kunert HJ, Rüther E. Assessing the efficacy of treatments for panic disorder and agoraphobia. I. Methodological problems. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (1995) 10:83–93. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199506000-00004

54. Dybek I, Bischof G, Grothues J, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, Hapke U, et al. The reliability and validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in a German general practice population sample. J Stud Alcohol. (2006) 67:473–81. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.473

55. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. (1998) 158:1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

56. Rumpf HJ, Wohlert T, Freyer-Adam J, Grothues J, Bischof G. Screening questionnaires for problem drinking in adolescents: performance of AUDIT, AUDIT-C, CRAFFT and POSIT. Eur Addict Res. (2013) 19:121–7. doi: 10.1159/000342331

57. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, editors. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press (1997). p. 191–218.

58. Aguayo R, Vargas C, de la Fuente EI, Lozano LM. A meta-analytic reliability generalization study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. (2011) 11:343–61.

59. Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient Patient Centered Outcomes Res. (2014) 7:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0036-x

60. Mittag O, Raspe H. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der subjektiven Prognose der Erwerbstätigkeit: Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung an 4279 Mitgliedern der gesetzlichen Arbeiterrentenversicherung zu Reliabilität (Guttman-Skalierung) und Validität der Skala. Rehabilitation. (2003) 42:169–74. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40095

61. Bouwmans C, De Jong K, Timman R, Zijlstra-Vlasveld M, Van der Feltz-Cornelis C, Tan SS, et al. Feasibility, reliability and validity of a questionnaire on healthcare consumption and productivity loss in patients with a psychiatric disorder (TiC-P). BMC Health Serv Res. (2013) 13:217. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-217

62. Ebert DD, Kählke F, Buntrock C, Berking M, Smit F, Heber E, et al. A health economic outcome evaluation of an internet-based mobile-supported stress management intervention for employees. Scand J Work Environ Heal. (2018) 44:171–82. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3691

63. Buntrock C, Berking M, Smit F, Lehr D, Nobis S, Riper H, et al. Preventing depression in adults with subthreshold depression: health-economic evaluation alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of a web-based intervention. J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6587

64. Nobis S, Ebert DD, Lehr D, Smit F, Buntrock C, Berking M, et al. Web-based intervention for depressive symptoms in adults with types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: a health economic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 212:199–206. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.10

65. Ebert DD, Lehr D, Boß L, Riper H, Cuijpers P, Andersson G, et al. Efficacy of an internet-based problem-solving training for teachers: results of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Heal. (2014) 40:582–96. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3449

66. Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Eval Program Plann. (1982) 5:233–7. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X

67. Schmidt J, Wittmann WW. Fragebogen zur messung der patientenzufriedenheit. In: Brähler E, Schumacher J, Strauß B. Diagnostische Verfahren in der Psychotherapie. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing GmbH (2002). p. 392–6.

68. Boß L, Lehr D, Schaub MP, Castro RP, Riper H, Berking M, et al. Efficacy of a web-based intervention with and without guidance for employees with risky drinking: results of a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Addiction. (2018) 113:635–46. doi: 10.1111/add.14085

69. Wilmers F, Munder T, Leonhart R, Herzog T, Plassmann R, Barth J, et al. Die deutschsprachige Version des Working Alliance Inventory-short revised (WAI-SR)-Ein schulenübergreifendes, ökonomisches und empirisch validiertes Instrument zur Erfassung der therapeutischen Allianz. Klin Diagnostik u Eval. (2008) 1:343–58.

70. Munder T, Wilmers F, Leonhart R, Linster HW, Barth J. Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised (WAI-SR): psychometric properties in outpatients and inpatients. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2010) 17:231–9. doi: 10.1002/cpp.658

71. Ladwig I, Rief W, Nestoriuc Y. Welche risiken und nebenwirkungen hat psychotherapie? - Entwicklung des Inventars zur Erfassung Negativer Effekte von Psychotherapie (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie. (2014) 24:252–63. doi: 10.1159/000367928

72. Nigatu YT, Liu Y, Wang JL. External validation of the international risk prediction algorithm for major depressive episode in the US general population: The PredictD-US study. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0971-x

73. King M, Bottomley C, Bellón-Saameño JA, Torres-Gonzalez F, Švab I, Rifel J, et al. An international risk prediction algorithm for the onset of generalized anxiety and panic syndromes in general practice attendees: predict A. Psychol Med. (2011) 41:1625–39. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002400

74. Liu Y, Sareen J, Bolton J, Wang J. Development and validation of a risk-prediction algorithm for the recurrence of panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. (2015) 32:341–8. doi: 10.1002/da.22359

75. Kessler RC, Van Loo HM, Wardenaar KJ, Bossarte RM, Brenner LA, Cai T, et al. Testing a machine-learning algorithm to predict the persistence and severity of major depressive disorder from baseline self-reports. Mol Psychiatry. (2016) 2:1366–71. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.198

76. Støen Grotmol K, Gude T, Moum T, Vaglum P, Tyssen R. Risk factors at medical school for later severe depression: a 15-year longitudinal, nationwide study (NORDOC). J Affect Disord. (2013) 146:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.047

77. Hölzel L, Härter M, Reese C, Kriston L. Risk factors for chronic depression - a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2011) 129:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.025

78. Bromberger JT, Schott L, Kravitz HM, Joffe H. Risk factors for major depression during midlife among a community sample of women with and without prior major depression: are they the same or different? Psychol Med. (2015) 45:1653–64. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002773

79. Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Seeley JR. Adolescent psychopathology: IV. Specificity of psychosocial risk factors for depression and substance abuse in older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1995) 34:1221–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00021

80. Ebert DD, Buntrock C, Mortier P, Auerbach R, Weisel KK, Kessler RC, et al. Prediction of major depressive disorder onset in college students. Depress Anxiety. (2019) 36:294–304. doi: 10.1002/da.22867

81. Barkow K, Maier W, Üstün TB, Gänsicke M, Wittchen H-U, Heun R. Risk factors for new depressive episodes in primary health care: an international prospective 12-month follow-up study. Psychol Med. (2002) 32:595–607. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702005263

82. Yanzón de la Torre A, Oliva N, Echevarrieta PL, Pérez BG, Caporusso GB, Titaro AJ, et al. Major depression in hospitalized Argentine general medical patients: prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. (2016) 197:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.066

83. Zuroff D, Koestner R, Moskowitz DS, McBride C, Marshall M, Bagby M. Autonomous motivation for therapy: a new common factor in brief treatments for depression. Psychother Res. (2007) 17:137–48. doi: 10.1080/10503300600919380

84. Johansson R, Nyblom A, Carlbring P, Cuijpers P, Andersson G. Choosing between Internet-based psychodynamic versus cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a pilot preference study. BMC Psychiatry. (2013) 13:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-268

85. Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. J Clin Psychol. (2011) 67:155–65. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20759

86. Renn BN, Hoeft TJ, Lee HS, Bauer AM, Areán PA. Preference for in-person psychotherapy versus digital psychotherapy options for depression: survey of adults in the U.S. NPJ Digit Med. (2019) 2:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0077-1

87. Vousoura E, Verdeli H, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Baily CDR. Parental divorce, familial risk for depression, and psychopathology in offspring: a three-generation study. J Child Fam Stud. (2012) 21:718–25. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9523-7

88. Heslin M, Desai R, Lappin JM, Donoghue K, Lomas B, Reininghaus U, et al. Biological and psychosocial risk factors for psychotic major depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2016) 51:233–45. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1131-1

89. Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Paradis AD. General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2000) 39:223–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00023

90. Chan MF, Zeng W. Exploring risk factors for depression among older men residing in Macau. J Clin Nurs. (2011) 20:2645–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03689.x

91. Salokangas RKR, Poutanen O. Risk factors for depression in primary care findings of the TADEP project. J Affect Disord. (1998) 48:171–80. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00171-7

92. Anstey KJ, Von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2007) 15:497–505. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8

93. Joo Y, Roh S. Risk factors associated with depression and suicidal ideation in a rural population. Environ Health Toxicol. (2016) 31:e2016018. doi: 10.5620/eht.e2016018

94. Chang SC, Pan A, Kawachi I, Okereke OI. Risk factors for late-life depression: a prospective cohort study among older women. Prev Med. (2016) 91:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.014

95. Wang JL, Sareen J, Patten S, Bolton J, Schmitz N, Birney A. A prediction algorithm for first onset of major depression in the general population: development and validation. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2014) 68:418–24. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202845

96. Blanco C, Rubio J, Wall M, Wang S. Risk factors for anxiety disorders: common and specific effects in a national sample. Depress Anxiety. (2014) 31:756–64. doi: 10.1002/da.22247

97. Wilson S, Vaidyanathan U, Miller MB, McGue M, Iacono WG. Premorbid risk factors for major depressive disorder: are they associated with early onset and recurrent course? Dev Psychopathol. (2014) 26:1477–93. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414001151

98. Berg L, Rostila M, Hjern A. Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults – a national cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. (2016) 57:1092–8. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12560

99. Appel CW, Frederiksen K, Hjalgrim H, Dyregrov A, Dalton SO, Dencker A, et al. Depressive symptoms and mental health-related quality of life in adolescence and young adulthood after early parental death. Scand J Public Health. (2018) 47:782–92. doi: 10.1177/1403494818806371

100. Pelkonen M, Marttunen M, Kaprio J, Huurre T, Aro H. Adolescent risk factors for episodic and persistent depression in adulthood. A 16-year prospective follow-up study of adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2008) 106:123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.001

101. Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Mensebach C, Grabe H, Hill A, Gast U, et al. Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): erste befunde zu den psychometrischen kennwerten. Psychother Psychosom Medizinische Psychol. (2010) 60:442–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247564

102. Brausch AM, Gutierrez PM. The role of body image and disordered eating as risk factors for depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Suicide Life Threatening Behav. (2009) 39:58–71. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.58

103. Robinson E, Sutin A, Daly M. Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective relation between obesity and depressive symptoms in U.S. and U.K. adults. Heal Psychol. (2017) 36:112–21. doi: 10.1037/hea0000426

104. Czeglédi E, Urbán R. Risk factors and alteration of depression among participants of an inpatient weight loss program. Psychiatr Hung. (2012) 27:361–78.

105. Riquin E, Lamas C, Nicolas I, Dugre Lebigre C, Curt F, Cohen H, et al. A key for perinatal depression early diagnosis: the body dissatisfaction. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.032

106. Hoare E, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Millar L, Allender S. Associations between obesogenic risk factors and depression among adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2014) 15:40–51. doi: 10.1111/obr.12069

107. Hilbert A, de Zwaan M, Braehler E. How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? Norms of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e29125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029125

108. Ogawa S, Kitagawa Y, Fukushima M, Yonehara H, Nishida A, Togo F, et al. Interactive effect of sleep duration and physical activity on anxiety/depression in adolescents. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 273:456–60. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.085

109. Zhou X, Bi B, Zheng L, Li Z, Yang H, Song H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for depression symptoms in a rural Chinese sample population. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e99692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099692

110. Tang B, Liu X, Liu Y, Xue C, Zhang L. A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-623

111. Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Balluz LS, Gonzalez O, Crider R, Berry JT, et al. Depression and anxiety in the United States: findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Psychiatr Serv. (2015) 59:1383–90. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1383

112. Bernard O, Gibson RC, McCaw-Binns A, Reece J, Coore-Desai C, Shakespeare-Pellington S, et al. Antenatal depressive symptoms in Jamaica associated with limited perceived partner and other social support: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194338

113. Kliem S, Job A-K, Kröger C, Bodenmann G, Stöbel-Richter Y, Hahlweg K, et al. Entwicklung und Normierung einer Kurzform des Partnerschaftsfragebogens (PFB-K) an einer repräsentativen deutschen Stichprobe. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. (2012) 41:81–9. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443/a000135

114. Han K-M, Jee H-J, An H, Shin C, Yoon H-K, Ko Y-H, et al. Intimate partner violence and incidence of depression in married women: a longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.041

115. Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM. Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e51740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051740

116. Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, Schimmenti A, Bifulco A, Kaess M. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2016) 190:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006

117. Nakulan A, Sumesh TP, Kumar S, Rejani PP, Shaji KS. Prevalence and risk factors for depression among community resident older people in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. (2017) 57:262–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166640

118. Kounali D, Zammit S, Wiles N, Sullivan S, Cannon M, Stochl J, et al. Common versus psychopathology-specific risk factors for psychotic experiences and depression during adolescence. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:2557–66. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000026

119. Rajapakshe OBW, Sivayogan S, Kulatunga PM. Prevalence and correlates of depression among older urban community-dwelling adults in Sri Lanka. Psychogeriatrics. (2019) 19:202–11. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12389

120. Brugha TS, Cragg D. The list of threatening experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1990) 82:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01360.x

121. Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Hallgren M, Firth J, Richards J, Schuch F, et al. Physical activity and anxiety: a perspective from the World Health Survey. J Affect Disord. (2017) 208:545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.028

122. Blough J, Loprinzi PD. Experimentally investigating the joint effects of physical activity and sedentary behavior on depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. (2018) 239:258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.019

123. Schilling R, Schärli E, Fischer X, Donath L, Faude O, Brand S, et al. The utility of two interview-based physical activity questionnaires in healthy young adults: comparison with accelerometer data. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0203525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203525

124. Owens SA, Helms SW, Rudolph KD, Hastings PD, Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. Interpersonal stress severity longitudinally predicts adolescent girls' depressive symptoms: the moderating role of subjective and HPA axis stress responses. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2019) 47:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0483-x

125. Yeoh SH, Tam CL, Wong CP, Bonn G. Examining depressive symptoms and their predictors in malaysia: stress, locus of control, and occupation. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01411

126. Sydenham M, Beardwood J, Rimes KA. Beliefs about emotions, depression, anxiety and fatigue: a mediational analysis. Behav Cogn Psychother. (2017) 45:73–8. doi: 10.1017/S1352465816000199

127. Brockmeyer T, Kulessa D, Hautzinger M, Bents H, Backenstrass M. Differentiating early-onset chronic depression from episodic depression in terms of cognitive-behavioral and emotional avoidance. J Affect Disord. (2015) 175:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.045

128. Appel M, Gnambs T, Maio GR. A short measure of the need for affect. J Pers Assess. (2012) 94:418–26. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.666921

129. Kashdan TB, Zvolensky MJ, McLeish AC. Anxiety sensitivity and affect regulatory strategies: individual and interactive risk factors for anxiety-related symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. (2008) 22:429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.011

130. Hovenkamp-Hermelink JHM, van der Veen DC, Oude Voshaar RC, Batelaan NM, Penninx BWJH, Jeronimus BF, et al. Anxiety sensitivity, its stability and longitudinal association with severity of anxiety symptoms. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39931-7

131. Kemper CJ, Ziegler M, Taylor S. Überprüfung der psychometrischen qualität der deutschen version des angstsensitivitätsindex-3. Diagnostica. (2009) 55:223–33. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924.55.4.223

132. Crowe L, Butterworth P. The role of financial hardship, mastery and social support in the association between employment status and depression: results from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009834

133. Slotman A, Snijder MB, Ikram UZ, Schene AH, Stevens GWJM. The role of mastery in the relationship between perceived ethnic discrimination and depression: the HELIUS study. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. (2017) 23:200–8. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000113

134. Pahlevan Sharif S. Locus of control, quality of life, anxiety, and depression among Malaysian breast cancer patients: the mediating role of uncertainty. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2017) 27:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.01.005

135. Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. (1978) 19:2–21. doi: 10.2307/2136319

136. Young CC, Dietrich MS. Stressful life events, worry, and rumination predict depressive and anxiety symptoms in young adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. (2015) 28:35–42. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12102

137. Gorday JY, Rogers ML, Joiner TE. Examining characteristics of worry in relation to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and attempts. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 107:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.004

138. Topper M, Emmelkamp PMG, Watkins E, Ehring T. Development and assessment of brief versions of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and the Ruminative Response Scale. Br J Clin Psychol. (2014) 53:402–21. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12052

139. MacPhee AR, Andrews JJW. Risk factors for depression in early adolescence. Adolescence. (2006) 41:435–66.

140. Muris P, Meesters C, Pierik A, de Kock B. Good for the self: self-compassion and other self-related constructs in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-clinical youths. J Child Fam Stud. (2016) 25:607–17. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0235-2

141. von Collani G, Herzberg PY. Eine revidierte fassung der deutschsprachigen skala zum selbstwertgefühl von rosenberg [A revised version of the german adaptation of rosenberg's self-esteem scale]. Zeitschrift Differ Diagnostische Psychol. (2003) 24:3–7. doi: 10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.3

142. Li J, Theng YL, Foo S. Depression and psychosocial risk factors among community-dwelling older adults in Singapore. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2015) 30:409–22. doi: 10.1007/s10823-015-9272-y

143. Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Odgers CL, Ambler A, Moffitt TE, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2016) 51:339–48. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7