- 1Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California, San Diego, CA, United States

- 3Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders, Shanghai, China

Methamphetamine (MA) has become one of the most widely used illicit substances in China and the rest of the world as well. Relapse, incarceration or death was observed after compulsory rehabilitation. However, the knowledge of recovery patterns among MA-dependent patients, early or late occurrence of these negative consequences, is limited. The aims were to explore the long-term recovery patterns and associated factors among MA-dependent patients in Shanghai, China. MA-dependent patients discharged from Shanghai compulsory rehabilitation facilities in 2009–2012 were recruited in a baseline survey. The baseline data of 232 patients were then linked with their long-term follow-up data from official records. Group-based trajectory modeling was applied to identify distinctive trajectories of the occurrence of negative consequences (incarceration, or readmission to compulsory rehabilitation, or death). Patients with monthly status data were found recovering with three distinctive trajectories: rare, late, and early occurrence groups. Multinomial logistic regression showed that having alcohol use history was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group. Having opioid use history was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the early occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group. In addition, being female was associated with decreased likelihood of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group.

Introduction

While ranking second in the share of the global burden of disease attributable to drug use disorders after opioids, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) are the most frequently used class of illicit drugs in China, and people using opioids also gradually switched to ATS (1, 2). Methamphetamine (MA) is the primary drug used among ATS. MA dependence has a relapse rate of 30%–90%, and a study in 2014 showed that 61% of the MA users relapsed within 1 year following treatment discharge (3–5). MA use is also linked to crime, such as drug dealing, property crime, fraud or violent crime, especially acquisitive crime (6–9).

Relapse is associated with more than a single factor. Previous studies found that both biological and sociocultural characteristics of patients could influence relapse (10, 11). It was revealed that some demographic factors such as age, gender and education level related to relapse among ATS users (12, 13). Meanwhile, patients’ mental comorbidities, having psychotic symptoms and polydrug use, were risk factors or protective factors (13–15). Crime is also related to a combination of drug use and sociocultural characteristics (12). It was found that frequent drug and alcohol use were risk factors for incarceration among Thai MA users (16). Furthermore, there was a picture of mutual influence between relapse and crime. Among Japanese patients with MA use disorder, history of incarceration was associated with treatment retention (13).

In China, there is a compulsory treatment program, according to the Chinese narcotic control law, for patients who fail to remain abstinent from drug use in the community. The compulsory rehabilitation program is an enforced residential drug treatment. Thus, participants in this study maintained abstinence from entrance to discharge. It is conducted by a judicial office, and the patient who has an addiction to illicit drugs may be sent to obtain a compulsory treatment, which is usually for 2 years. This compulsory treatment program aimed for comprehensive recovery of physical health (daily physical exercise), from drug dependence and of social functioning, which includes medication or physical rehabilitation, psychotherapy and vocational skills training and anti-relapse education. In this program, they received no medications related to drug dependence. When the compulsory treatment program is completed, there are social worker networks to prevent relapse and crime and promote social functioning recovery (17). Patients who are discharged from the compulsory treatment program are assigned to participate in the community-based drug rehabilitation program that serves at their place of residence. After the compulsory treatment program, patients will participate in the community-based drug rehabilitation program, and social workers could provide psychological counseling, vocational training and social welfare consultation, which is funded by the government (18). Therefore, to assess the comprehensive recovery of patients after the treatment using the Chinese model, we define negative consequences (NC) (including incarceration, readmission to compulsory rehabilitation and death) to assess rehabilitation, which was used in our previous study among heroin patients (19).

In community-based rehabilitation, patients have different recovery trajectories. Some patients have NC, while others abstinence. The time points of NC occurrence were different, which range from a few months to years in our observation. However, a few research has indicated how the trajectory develops and what factors affect rehabilitation trajectories. Recently, there was a nationwide systematic multicenter survey of the characteristics of drug use behaviors in club drug users and associated high-risk sexual behavior in China, which showed that the pursuit of euphoria was the main reason for drug use. High-risk sexual behaviors were common in these users. The factors of polydrug use, long use history and severe acute intoxication after drug use were associated with risky sexual behaviors. With this survey, this study has required part of the baseline data to explore the recovery trajectories (20). We investigated recovery patterns of MA-dependent patients and associated risk factors, based on an electronic monthly summary record system of persons using illicit drugs in Shanghai, China. This follow-up database, which was established by Shanghai Municipal Narcotics Control Committee, provided us a unique opportunity to describe the recovery patterns among MA-dependent patients. We used group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) to identify distinctive trajectories of the presence of NC after patients were discharged from compulsory rehabilitation programs.

Methods

Design

This study was a cohort study. The baseline data were collected from the project “Research on mathematical model for AIDS epidemic trend assessment and prediction in China” (20). After the baseline assessment, our participants were passively followed up: participants’ long-term outcomes were ascertained from the electronic monthly summary record system, which was managed by social workers. Unique ID numbers were used to link baseline data to follow-up data.

This study was approved by the institutional Review Boards in Shanghai Mental Health Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures were in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Participants

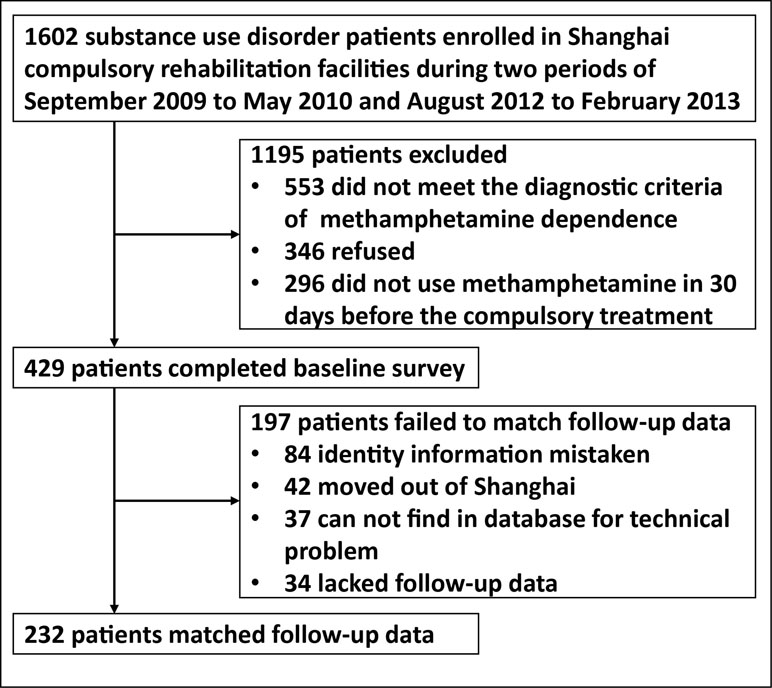

At baseline, we used convenience sampling to recruit 429 MA-dependent patients from two compulsory rehabilitation centers in Shanghai from September 2009 to May 2010 and from August 2012 to February 2013. Patients who met the inclusion criteria should: a) have MA dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition diagnostic criteria; b) be at the age of 18 and above; c) have used MA in 30 days (by urinalysis) before the mandatory drug rehabilitation; and d) have the ability of informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: a) serious physical or neurological illness that required pharmacological treatment; b) other Axis I disorder of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria, such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression and substance dependence (other than nicotine and MA) within the past 5 years; and c) neurological diseases, such as stroke, seizure, migraine, and head trauma. The process is displayed in Figure 1.

Measurements

At baseline, a commonly used Chinese version of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was used to assess patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and drug use history, including age, sex, employment, marriage, alcohol/drug usage and so on (21, 22).

The follow-up data of participants after compulsory rehabilitation programs were derived from the electronic monthly summary record system from 2009 to 2017. Shanghai Municipal Narcotics Control Committee established this database in March 2007. Social workers who are employed by the Shanghai government are responsible for managing this administrative database, while helping the patients with drug dependence recover in the community. The following categories of drug-related information were recorded each month in chronological order, including incarceration, readmission to compulsory rehabilitation programs, death, methadone maintenance treatment participation, etc. These events were recorded as binary variables (happened or not).

For the present study, recovery outcomes were classified into four monthly outcomes: incarceration, readmission to compulsory rehabilitation programs, death, and the rest (not encoded as any of other cases). Our outcome variable of interest, negative consequences, is defined as having incarceration, readmission to compulsory rehabilitation programs or death. According to the Anti-drug Law in China (17), patients who were discharged from compulsory rehabilitation programs should participate in a long-term community-based rehabilitation program. During the community-based rehabilitation program, using illicit drugs could lead to readmission into compulsory rehabilitation programs. Readmission was only triggered by seriously violating the community-based recovery agreement or reusing drugs, which means those readmission cases relapsed. According to clinical observation, we hypothesized the recovery patterns of patients, which can be divided to the following: 1) NC happened in a relatively short time after compulsory rehabilitation programs (early occurrence group); 2) NC happened long after compulsory rehabilitation programs (late occurrence group); and 3) NC rarely happened (rare occurrence group).

Statistical Analyses

Group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) was used to analyze the patient’s recovery trajectories. GBTM is a specialized application of finite mixture modeling. In this study, GBTM identifies clusters of individuals with similar recovery trajectory and explores heterogeneity across groups. The monthly repeated measures of NC were estimated by a polynomial relationship as below:

Where i, j, and t indicate subjects, latent group, and time, respectively, and ε is a disturbance normally distributed with a zero mean and a constant residual variance.

The shape of trajectory for each group determined β0, β1 and β2, which represent the intercept, linear and quadratic parameters, respectively. (23, 24). We used ‘traj’ plugin in Stata release 12 for analysis (25–27). Corresponding to the binary variables of the recovery data, the Logistic Model was used. A series of models were fitted with an increasing number of trajectory groups. The goodness of fit model was evaluated with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (28). The best fitting model was chosen with a reasonably low absolute value of BIC and sufficient number of subjects (10% of total sample or more) in each group (29).

For the subgroups with separated trajectories, multinomial logistic regression was used to explore the relationship between one’s recovery pattern and baseline factors.

Results

Attrition and Characteristics of Patients

Among 429 participants, 232 patients’ follow-up data were found in the official database and were linked to their baseline data. The rest of the participants’ follow-up data were not found due to mistaken identity, those who moved out of Shanghai or technical problems (see Figure 1). Among all 429 patients, 68.2% were male; 46.9% were unemployed or had spent time in prison in the 3 years prior to the baseline interview; over half (60.3%) were not currently married; they had, on average, a 3.1 ± 2.6-year history of MA use, and in 30 days before compulsory rehabilitation, they had 15.0 ± 12.0 times of drug use on average (see Supplementary Table 1).

Status During 30 Months of Follow-Up and Recovery Patterns

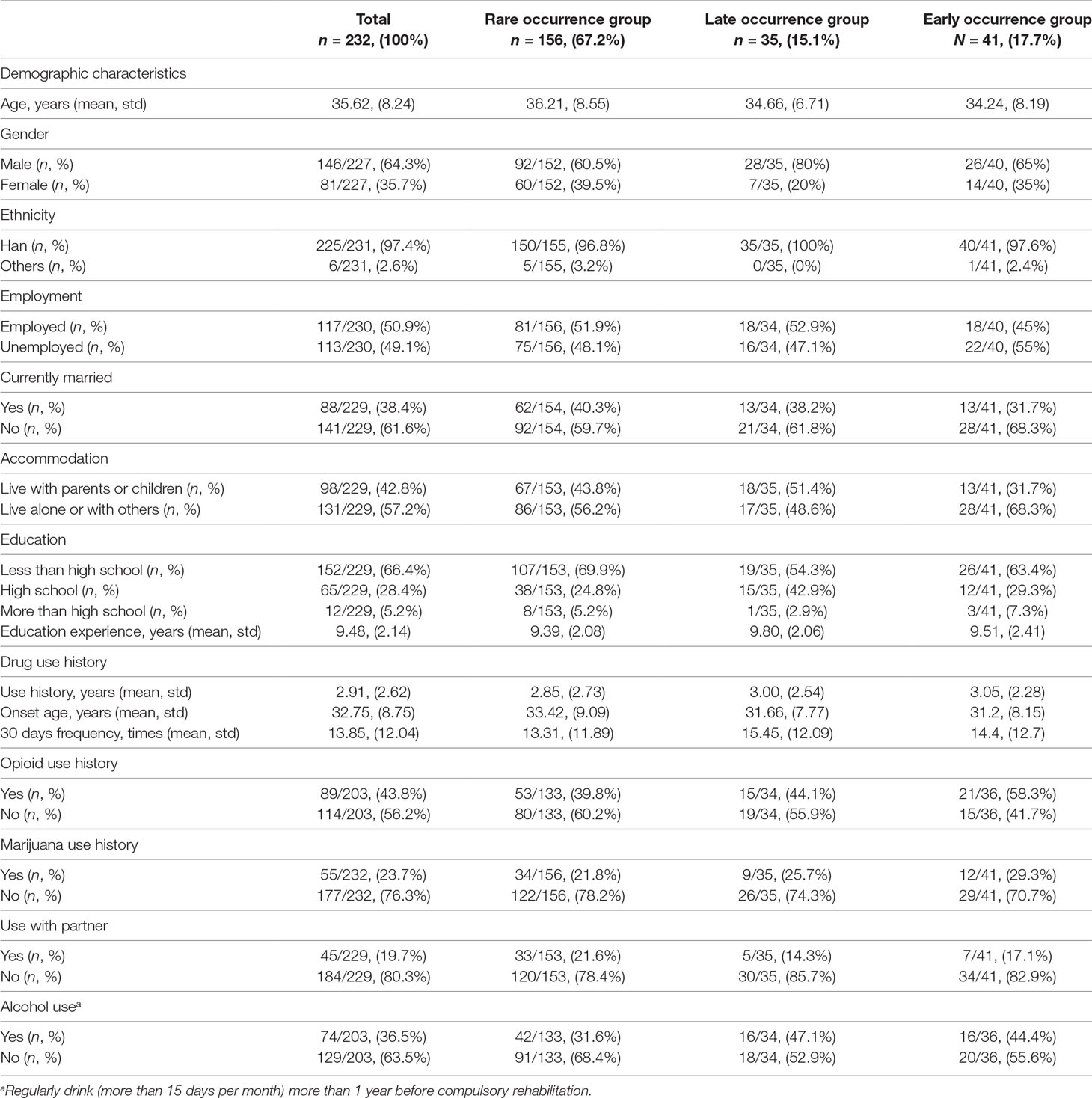

As participants were discharged at different time, our follow-up data ranged from 30 to 86 months. Thus, we truncated the first 30 months after compulsory rehabilitation programs for analysis. The monthly prevalence of each NC and incidence rates of all NC after compulsory rehabilitation are graphically displayed in Figure 2. Incidence rates were calculated by person-time methods, dividing the number of NC by the number of NC and in community monthly. Two peaks of NC were observed. Thus, we confirmed our hypothesis that the recovery patterns of patients can be divided as early occurrence group, late occurrence group and rare occurrence group.

Figure 2 Recovery status of methamphetamine patients after completed the compulsory rehabilitation program in Shanghai, China.The line displayed the incidence rate (per 100 person months) and the area in the figure showed the monthly prevalence of each negative consequence (incarceration, readmission to compulsory treatment and death). There was no death case that happened during this period.

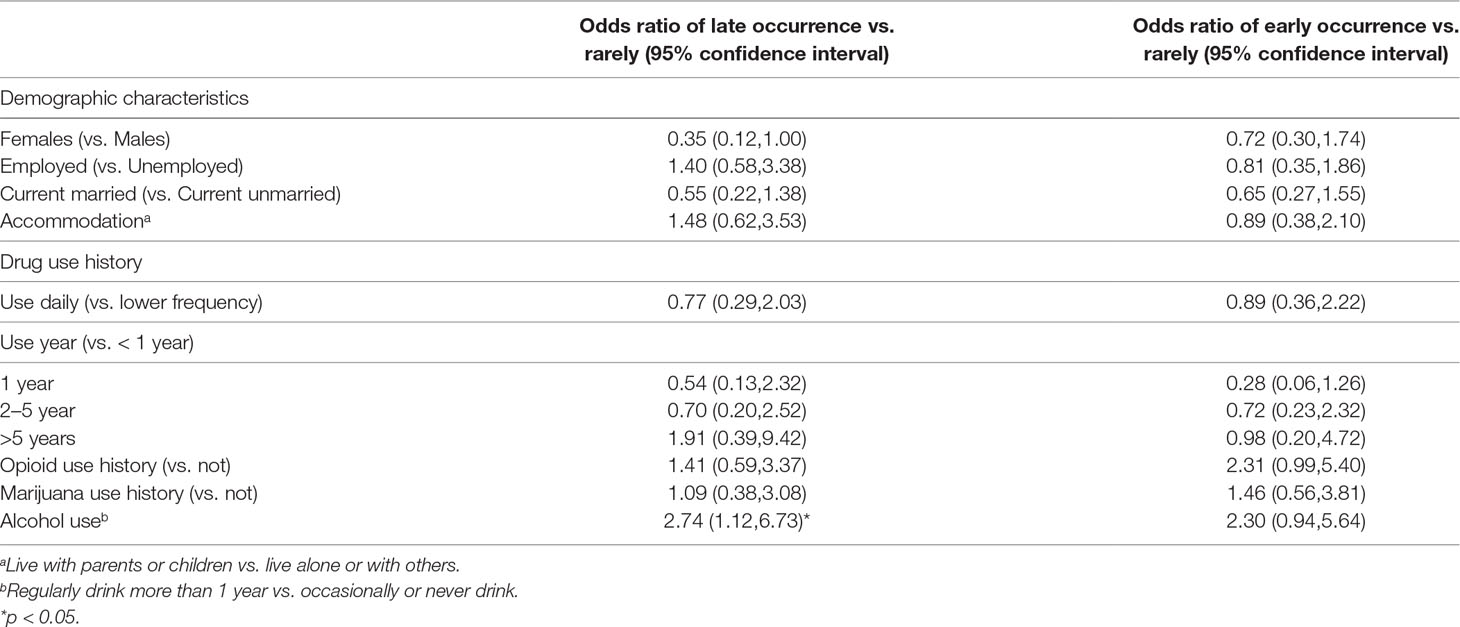

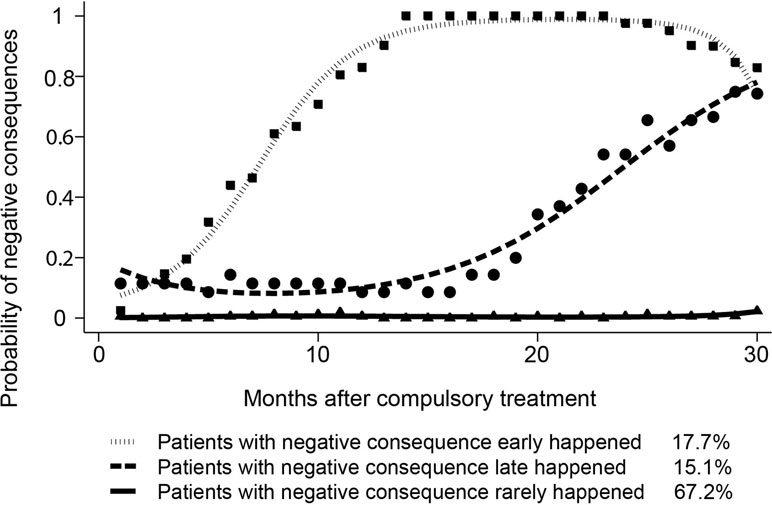

A series of group-based trajectory models, from a two- to five-trajectory pattern, were fitted to identify the optimal model. The BIC values (BIC = −1,538.40) in the two-trajectory model, three (BIC =−1,236.76), four (BIC = −1,145.07) and five (BIC = −1,046.75) were used for model evaluation. To evaluate class separation, the relative entropy of the posterior probability distribution was calculated and had a value of 0.8, indicating the acceptable separation between classes (30). When the relatively low absolute value of BIC and the sufficient number of subjects in each group and clinical interpretability were considered, the three-trajectory model was selected as potential optimal models. The trajectories and baseline characteristics are displayed in Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively.

Figure 3 Trajectories as defined by group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) analysis of recovery status over time.Three-trajectory group-based trajectory modeling was used to fit the recovery data of methamphetamine patients and predict possibility of negative consequences. Negative consequences included incarceration, readmission to compulsory treatment and death.

Associated Factors of Negative Consequences

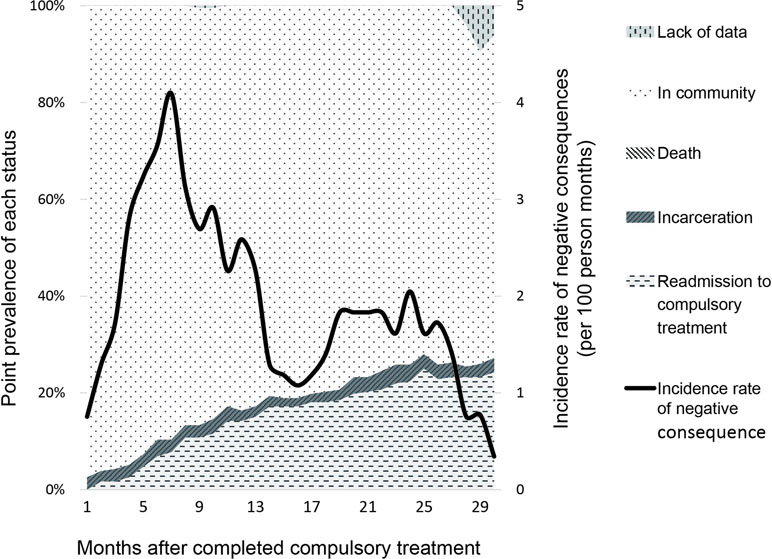

When distinct trajectories were identified by GBTM, multinomial logistic regression was used to explore the relationship between one’s recovery pattern and baseline characteristics. Regression results are presented in Table 2. Having alcohol use history (use more than 15 days per month) was associated with the increased likelihood (OR = 2.74, p = 0.027) of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group. Having opioid use history was associated with increased likelihood (OR = 2.35, p = 0.053) of being in the early occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group, although the estimation association was marginally significant. In addition, being female was associated with the decreased likelihood (OR = 0.37, p = 0.051) of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group, and the association was also marginally significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining recovery patterns among MA-dependent patients after compulsory rehabilitation programs in China. Our findings extended our knowledge of long-term recovery trajectories of MA-dependent patients and associated factors. By using GBTM, we identified three groups among MA-dependent patients: early occurrence group, late occurrence group, and rare occurrence group. Alcohol use history, opioid use history and being female might be associated with patients’ recovery trajectories.

We found that baseline alcohol use history was associated with increased likelihood of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group, and baseline opioid use history was associated with increased likelihood of being in the early occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group. These findings were consistent with previous studies showing that drug use disorders were closely associated with alcohol use (31). In addition, heavy alcohol consumption increased the risk of violent behaviors, and alcohol use accounted for 12–18% of the violence risk related to MA use (32). Violent behaviors might result in incarceration, which is another aspect of NC. Moreover, brain image research of functional links in valuation networks demonstrated that heroin abstinence could influence functional connectivity and resulted in impulsive behaviors (33). A recent animal study showed that the sensitivity to opioids, which involved the mu-opioid receptor (MOP-r) regulated systems, has a negative genetic correlation with MA consumption in mice (34). This indicated that opioid sensitivity and MA intake were genetically associated, and opioid-mediated pathways influence MA use. Previous studies found that in long-term opiate abusers, the function of the MOP-r is altered in response to its ligands (35–37). It is also observed that MA use was a problem in patients in methadone maintenance treatment (38, 39). Furthermore, in patients with severe alcoholism, a neuroadaptation to an alcohol-induced release of endogenous ligands appeared to reduce MOP-r (40). The change of MOP-r might be related to the higher risk of relapse, the main part of NC. It would be interesting to explore in future research whether what we found in the current study that alcohol and opioid use history predicted the occurrence of NC was related to the severity of MOP-r dysfunction. Our findings also suggested that being female was associated with decreased likelihood of being in the late occurrence group relative to the rare occurrence group. This was consistent with our previous study with heroin-dependent patients, which was found that female patients were less likely to experience negative outcomes than male patients (19).

In our results, when opioid and alcohol use affected the occurrence of NC, social and family factors did not seem to have a critical impact on it. This suggests that neurobiological changes caused by poly-substance use may have a greater impact on long-term rehabilitation. Therefore, the experience of pharmacotherapy in alcohol and opioid dependence could enlighten long-term NC prevention in MA dependence (41, 42), and it might be necessary to address the problem of poly-substance use that shares the similar neurobiological change.

Our study had several limitations. First, although NC might be better than considering relapse or crime separately in assessing recovery trajectory, readmission in NC could cause underestimation of relapse because we could not directly measure patients’ relapse. Thus, our outcome of readmission might not be an ideal proxy for relapse, as patients may relapse but were not found by social workers or readmitted to a compulsory rehabilitation center. In addition, we did not have data on patients’ mental health, healthcare obtained, and other characteristics that changed with time, which might also impact on patients’ recovery trajectory. Furthermore, our results might not be generalized to MA-dependent patients in other areas of China, considering regional variations across China, or those who were not admitted to compulsory rehabilitation programs.

In conclusion, MA-dependent patients presented various recovery patterns after being discharged from compulsory rehabilitation programs in Shanghai, China. When caring for MA-dependent patients, healthcare providers should take patients’ alcohol use problem into consideration to prevent the occurrence of NC. Future prevention and early intervention of NC should also consider more about patients with the history of poly-substance use.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study will not be made publicly available because the authors do not have permission to share data.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of name of guidelines, name of committee with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the name of committee.

Author Contributions

MZ and HJ designed this study, and all the authors participated in this process. NZ, YZ and ZC collected the data, and HT and DL analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All the authors edited the paper.

Funding

The authors thank the sponsors of National Key R&D Program of China [2017YFC1310400], Natural Science Foundation of China [81601164, U1502228, 81771436], Clinical Research Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine [DLY201818], Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality [18411961200], Municipal Human Resources Development Program for Outstanding Young Talents in Medical and Health Sciences in Shanghai [2017YQ013], Shanghai Mental Health Center Flyer Plan [2016FX003], Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader [17XD1403300], Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders [13dz2260500] and Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission (2017ZZ02021).

Conflict of Interests Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00398/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Annual National Narcotic Control Report 2017, Beijing, China: The Office of National Narcotics Control Commission; 2017.

2. World Drug Report 2016, United Nations Publication, Vienna United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2016.

3. He J, Xie Y, Tao J, Su H, Wu W, Zou S, et al. Gender differences in socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of methamphetamine inpatients in a Chinese population. Drug Alcohol Depend (2013) 130:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.014

4. Brecht ML, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Predictors of relapse after treatment for methamphetamine use. J Psychoactive Drugs (2000) 32:211–20. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400231

5. Brecht ML, Herbeck D. Time to relapse following treatment for methamphetamine use: a long-term perspective on patterns and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend (2014) 139:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.702

6. McKetin R, Najman JM, Baker AL, Lubman DI, Dawe S, Ali R, et al. Evaluating the impact of community-based treatment options on methamphetamine use: findings from the Methamphetamine Treatment Evaluation Study (MATES). Addiction (Abingdon, England) (2012) 107:1998–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03933.x

7. Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Brecht ML, Li L. Comparing the dynamic course of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use over 10 years. Addict behav (2008) 33:1581–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.024

8. McKetin R, Dunlop AJ, Holland RM, Sutherland RA, Baker AL, Salmon AM, et al. Treatment outcomes for methamphetamine users receiving outpatient counselling from the Stimulant Treatment Program in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev (2013) 32:80–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00471.x

9. Wilkins C, Sweetsur P. The association between spending on methamphetamine/amphetamine and cannabis for personal use and earnings from acquisitive crime among police detainees in New Zealand. Addiction (Abingdon, England) (2011) 106:789–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03241.x

10. Brecht ML, Anglin MD, Dylan M. Coerced treatment for methamphetamine abuse: differential patient characteristics and outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse (2005) 31:337–56. doi: 10.1081/ADA-200056764

11. Moeeni M, Razaghi EM, Ponnet K, Torabi F, Shafiee SA, Pashaei T. Predictors of time to relapse in amphetamine-type substance users in the matrix treatment program in Iran: a Cox proportional hazard model application. BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:265. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0973-8

12. Brecht ML, Greenwell L, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Two-year outcomes of treatment for methamphetamine use. J Psychoactive Drugs (2006) 38 (Suppl 3), 415–26. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10400605

13. Kobayashi O, Matsumoto T, Otsuki M, Endo K, Okudaira K, Wada K, et al. Profiles associated with treatment retention in Japanese patients with methamphetamine use disorder: preliminary survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2008) 62:526–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01845.x

14. Hillhouse MP, Marinelli-Casey P, Gonzales R, Ang A, Rawson RA. Predicting in-treatment performance and post-treatment outcomes in methamphetamine users. Addiction (Abingdon, England) (2007) 102 Suppl 1:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01768.x

15. Tziortzis D, Mahoney J. J. 3rd, Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, De La Garza R. 2nd. Pharmacol Biochem Behav (2011) 98:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.12.022

16. Sherman SG, Sutcliffe CG, Srirojn B, German D, Thomson N, Aramrattana A, et al. Predictors and consequences of incarceration among a sample of young Thai methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Rev (2010) 29:399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00146.x

17. National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Anti-Drug Law of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China (2007).

18. Rong C, Jiang HF, Zhang RW, Zhang LJ, Zhang JC, Zhang J, et al. Factors associated with relapse among heroin addicts: evidence from a two-year community-based follow-up study in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2016) 13:177. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020177

19. Haifeng J, Di L, Jiang D, Haiming S, Zhikang C, Liming F, et al. Gender differences in recovery consequences among heroin dependent patients after compulsory treatment programs. Sci Rep (2015) 5:17974. doi: 10.1038/srep17974

20. Bao YP, Liu ZM, Li JH, Zhang RM, Hao W, Zhao M, et al. Club drug use and associated high-risk sexual behaviour in six provinces in China. Addiction (Abingdon, England) (2015) 110 Suppl 1:11–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12770

21. Zhao M, Li X, Hao W, Wang Z, Zhang M, Xu D, et al. A preliminary study of the reliability and validity of the addiction severity index. J Tradit Chin Med (2004) 4:679–80.

22. Luo W, Zhu W, Wei X, Jia W, Zhang Q, Li L. Chinese assimilation of the fifth edition of addiction severity index scale and the evaluations on its applications in addiction status investigation. Chin J Drug Depend (2007) 16:373–76. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9718.2007.05.014

23. Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2010) 6:109–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413

24. Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res (2001) 29:374–93. doi: 10.1177/0049124101029003005

25. Press S. Stata longitudinal/panel data reference manual release 10 [M]. Stata Press (2007). ISBN:1597180319 9781597180313

26. Jones BL, Nagin DS. A note on a Stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociol Methods Res (2013) 42:608–13. doi: 10.1177/0049124113503141

27. Jones BL. traj: group-based modeling of longitudinal data. <http://www.contrib.andrew.cmu.edu/∼bjones/>

28. Schwarz G, Schwartz GJ, Schwarz G, Schwarz GE. Estimating the dimension for a model. Ann Stat (1978) 6:461–64.. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344136

29. Du J, Sun H, Huang D, Jiang H, Zhong N, Xu D, et al. Use trajectories of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) in Shanghai, China. Drug Alcohol Depend (2014) 143:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.031

30. Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth Mixture Modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Int J Behav Dev (2009) 33:565–76. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765

31. Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan W, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73:39–47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132

32. McKetin R, Lubman DI, Najman JM, Dawe S, Butterworth P, Baker AL. Does methamphetamine use increase violent behaviour? Evidence from a prospective longitudinal study. Addiction (Abingdon, England) (2014) 109:798–806. doi: 10.1111/add.12474

33. Zhai T, Shao Y, Chen G, Ye E, Ma L, Wang L, et al. Nature of functional links in valuation networks differentiates impulsive behaviors between abstinent heroin-dependent subjects and nondrug-using subjects. NeuroImage (2015) 115:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.060

34. Eastwood EC, Phillips TJ. Opioid sensitivity in mice selectively bred to consume or not consume methamphetamine. Addict Biol (2014) 19:370–9. doi: 10.1111/adb.12003

35. Keller B, La Harpe R, Garcia-Sevilla JA. Upregulation of IRAS/nischarin (I1-imidazoline receptor), a regulatory protein of mu-opioid receptor trafficking, in postmortem prefrontal cortex of long-term opiate and mixed opiate/cocaine abusers. Neurochem Int (2017) 108:282–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.04.017

36. Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol (2008) 154:384–96. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.100

37. Kim JA, Bartlett S, He L, Nielsen CK, Chang AM, Kharazia V, et al. Morphine-induced receptor endocytosis in a novel knockin mouse reduces tolerance and dependence. Current biology (2008) 18:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.057

38. Wang R, Ding Y, Bai H, Duan S, Ye R, Yang Y, et al. Illicit heroin and methamphetamine use among methadone maintenance treatment patients in Dehong Prefecture of Yunnan Province, China. PloS One (2015) 10:e0133431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133431

39. Alam-Mehrjerdi Z, Abdollahi M. The Persian methamphetamine use in methadone treatment in Iran: implication for prevention and treatment in an upper-middle income country Vol. 23. Daru: journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (2015). 51. doi: 10.1186/s40199-015-0134-5

40. Hermann D, Hirth N, Reimold M, Batra A, Smolka MN, Hoffmann S, et al. Low mu-opioid receptor status in alcohol dependence identified by combined positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology (2017) 42:606–14. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.145

41. Runarsdottir V, Hansdottir I, Tyrfingsson T, Einarsson M, Dugosh K, Royer-Malvestuto C, et al. Extended-release injectable naltrexone (XR-NTX) with intensive psychosocial therapy for amphetamine-dependent persons seeking treatment: a placebo-controlled trial. J Addict Med (2017) 11:197–204. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000297

Keywords: long-term follow-up, recovery pattern, negative consequences, trajectory, methamphetamine

Citation: Tan H, Liang D, Zhong N, Zhao Y, Chen Z, Zhao M and Jiang H (2019) History of Alcohol and Opioid Use Impacts on the Long-Term Recovery Trajectories of Methamphetamine-Dependent Patients. Front. Psychiatry 10:398. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00398

Received: 09 March 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2019;

Published: 07 June 2019.

Edited by:

Christian Beste, Dresden University of Technology, GermanyReviewed by:

Mercedes Lovrecic, National Institute for Public Health, SloveniaDomenico De Berardis, Azienda Usl Teramo, Italy

Copyright © 2019 Tan, Liang, Zhong, Zhao, Chen, Zhao and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Min Zhao, ZHJtaW56aGFvQHNtaGMub3JnLmNu; Haifeng Jiang, ZHJhZ29uamhmQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Haoye Tan1†

Haoye Tan1† Zhikang Chen

Zhikang Chen Haifeng Jiang

Haifeng Jiang