- 1Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 2Hospital de Magalhães Lemos, Porto, Portugal

- 3Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry (WHO Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Services Development), Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom

Background: In Portuguese law, police officers are the link between security and the treatment of people with serious mental disorders who require compulsory admission. The perceptions of police officers are in part based on their individual characteristics, and may influence their capability in managing patients they are transporting. However, little is known about police officers experience of this process.

Methods: In-depth semi-structured interviews explored the experiences and per- ceptions of police officers from Porto Police Department in Portugal. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and analyzed through thematic analysis.

Results: Ten police officers agreed to take part in this study. The interviewed police officers consisted of nine men and one woman, had an average length service of 22.6 years and all had more than 10 years of service. The interviews highlighted that the activity of the police under the Mental Health Law is shaped by whether the person who they are transporting has a mental health disorder and requires psychiatric admission. The police officers reportedly adjusted their behavior to give patients more attention, comfort and empathy. However, they describe these interactions as one of the most time consuming and challenging activities for the police. Importantly, they acknowledged family members as crucial for police officers to be able to gain direct access to patients and knowledge about them. Police officers showed to perceive people with mental illness as unpredictable, dangerous and without discernment, and identified some aspects of the process that could be improved, such as hospital admission waiting times. Police officers felt they required more skilled support to deal with unwell patients.

Conclusions: This study highlights the perceptions and experiences of police officers about the process of compulsory admission, and identifies areas of unmet needs. These findings help to raise awareness of their needs, improving this process, and ensuring a more humane and effective approach.

Introduction

Compulsory admission and treatment is a topic of intense debate in psychiatry. This is due to the effects such policies have on people's lives, given that it involves detaining them against their wishes and restricting their individual liberty (1). Compulsory treatment is ethically challenging, often associated with fear, exclusion and loss of self-determination (2, 3). The process is based on the assumption that the person is incapable of recognizing that their mental health has deteriorated and there is an urgent need for adequate treatment (4). The majority of mental health professionals disapproves coercive medical measures, but recognizes the impact upon patients' adherence to treatment (5). Some research has also found that a majority of patients understand that they were acutely unwell at the time of their admission and that coercive interventions enabled their recovery (6). However, some patients perceive their admission as a negative experience (6, 7), entailing an intrusion into their physical integrity and their liberty (3). These diverse views raise awareness to patients' potential feelings of ambivalence toward compulsory admissions.

Police officers are one of the first professionals to interact with people requiring compulsory admission due to their mental health. Research in North America (6, 8–12) and European countries (13), has highlighted that the approach adopted by the police officers is crucial to patient's cooperation (10, 14). Police officers' experience and personal characteristics play an important role in their own capacity in doing this task (15). Police officers with a higher level of education (12 years of education or more) appear to perceive people with mental disorders as less unpredictable and dangerous, and capable of having a family (16). Equally, police officers who performed more than six compulsory admission transportations used less physical force during them (16). Thus, the level of education and experience that police officers have in dealing with people with mental illness influences their behavior and perceptions about them (17). For that reason, education and contact should be effective strategies for changing police officers perceptions and attitudes toward people with serious mental disorders (18, 19). However, some police officers report that they do not feel properly trained to deal with a person with a serious mental disorder (9, 14), feeling unable to identify symptoms of mental illness or deal with psychotic or hostile behavior (6, 11).

Police officers see value in obtaining training to avoid potential bad practices (17). However, as a result of their lack of training some encounters between police officers and people with serious mental disorders result in abuse of force, precipitation of violent acts and sometimes even death (15, 20, 21). In the United States in 2015 about 23% (251 deaths) of the total number of deaths (n = 1099) resulted from police interactions with people with mental illness (22). The complexity of these interactions magnified the need for implementing standardized educational and training programs, as well as special police teams selected, trained and motivated to help people with serious mental disorders in crises (10, 23). These teams have demonstrated less aggressive interactions with people in crises when compared to police officers who did not receive such training (24). This complex reality has reinforced the need of more assistance from other groups (e.g., special medical local authorities), and a faster access to mental health services during this process (16, 25).

The procedural justice approach is seen as the main pathway to promote police legitimacy, and thus citizens' cooperation (26). This approach is grounded in two components (27): (i) the quality of the decision-making procedures (i.e., citizens participation in the proceedings before the authority's decision, giving citizens a voice, as well as the neutrality of such decision), and (ii) the quality of the treatment (i.e., the dignity and respect in which people are treated, and if the authorities' motives are perceived as trustworthy) (26, 28). These two components emerge into four key constructs that shape police encounters: (i) voice, (ii) trustworthy motives, (iii) dignity and respect, and (iv) neutrality in the decision making (26).

In Portugal, the Mental Health Law (Law n. ° 36/98, July 24th, 1998) aims to establish the main principles of Portuguese mental health policies and rules the compulsory admission for people with serious mental disorders (29). Although the Fundamental Health Law (Law n. °. 48/90, August 24th, 1990) establishes the patient's rights and duties in the Portuguese services (30), the mental health patients are endowed by the Portuguese Mental Health Law with more rights and duties. This illustrates the legal recognition of the idiosyncratic nature of mental illness, and its repercussions on the self-determination capacities of the person with a serious mental disorder, as well as the specific implications of psychiatric treatment, which obligates to ensure other rights and duties. Thus, the Mental Health Law is a crucial and nuclear framework declaration of mental health rights in Portuguese legal order (31). Its principles are more connected to guardianship and protection rather than medical or social care. This means that the juridical model prevails over the therapeutic model (32), as the assessment of the legal status of people with mental illness is governed by constitutional principles and norms, leading by equality and non-discrimination (33).

The Portuguese Mental Health Law (on 23rd article, urgent admission) gives a special role to the police officers who are responsible for the transportation of people with serious mental disorders to the psychiatric emergency service closest to their residence (29), and are the link between the security and treatment of these patients. Between 1999 and 2007 the percentage of compulsory admissions in Portugal at the Hospital de Magalhães Lemos, Porto, rose significantly. In 1999, 1 year after the implementation of the law, compulsory admissions represented 1.5% of all the admissions, whereas in 2007 this percentage rose to 7.2%. The same tendency is observed in Hospital Júlio de Matos, Lisbon, where in 1999 the amount of compulsory admissions represented 5.53% of all admissions compared to 15.31% in 2007 (34). Of utmost importance is the article cited to begin the process, because this determines whether the police are involved or not (e.g., in non-urgent situations). Between 2008 and 2010, 93.2% of all compulsory admissions at these two hospitals occurred following the article of urgent admission (35).

It is therefore clear the importance of police officers in compulsory admissions and in the delivery of involuntary mental health treatment. However, their interactions with people with serious mental disorders under the compulsory treatment procedure has not been studied. The lack of knowledge in this area requires attention as it is of public interest and would arguably lead to improvements in the mental health care, to ensure it is delivered with dignity and justice.

Methods

Settings and Participants

The study was conducted in six police departments of PSP (Polícia de Segurança Pública), in Porto, which were selected as they were those with higher number and frequency of compulsory admissions, covering a broad geographical area of Porto metropolitan police department (Matosinhos, Ribeira, Santo Tirso, Maia, Foz, Lagarteiro), and thus giving us some meaningful insight into the topic of the study. An information sheet with information about the study was distributed to all police officers in the department. Further to that, the main researcher approached the police officers in each department, providing them with information about the researchers, the scope of the study, a brief description of the method, and the contact details of the main researcher for any further questions.

The only inclusion criteria were that police officers had completed at least one compulsory admission under the Mental Health Law.

Data Collection and Analysis

A semi-structured interview topic guide was developed in consultation with a senior police officer (see Supplementary Material). The first author conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews exploring the experiences and perceptions of police officers of the compulsory admission process, and collected socio-demographic information (see Supplementary Material). All interviews were audio recorded using a digital voice recorder (Olympus WS- 853) and were transcribed verbatim. Contextual data relating to the approved police departments were also collected (e.g., a general description of the interview room like the climate conditions, natural light presence, and if there was any physical barrier between the interviewer and the interviewee).

Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts was conducted following the Braun and Clarke's (36) approach, and using the Nvivo 12 software. Police officers' names were replaced with numbers to protect their privacy. Initial codes were generated and then sorted into broader themes, with similar codes placed under the same theme. A theme was determined on the basis of significance to the research question. Themes were then revised and refined to ensure codes within each theme were greatly associated, and that each theme was distinctive. Themes were then named. Procedural consistency was guaranteed using a double-coding approach (by RS and MPC), with cross-checking between coders to ensure consistency.

Results

Twelve police officers were approached, and ten agreed to take part. The police officers interviewed from Porto Police department consisted of nine males and one female, all caucasians, with a mean age of 46.4 years (age range from 34 to 58). The interviews ranged in duration from 25 to 57 min. All were ungraduated police officers, with an average length of service of 22.6 years and all had more than 10 years of service. None of them described having history of mental illness themselves. Although all departments did several compulsory admissions per year, the volume of compulsory admissions differed across police departments, ranging from one intervention per month to several, according to seasons (spring/autumn), festive dates, and vacations periods. All of them reported that they had no specific training to deal with people with serious mental disorders.

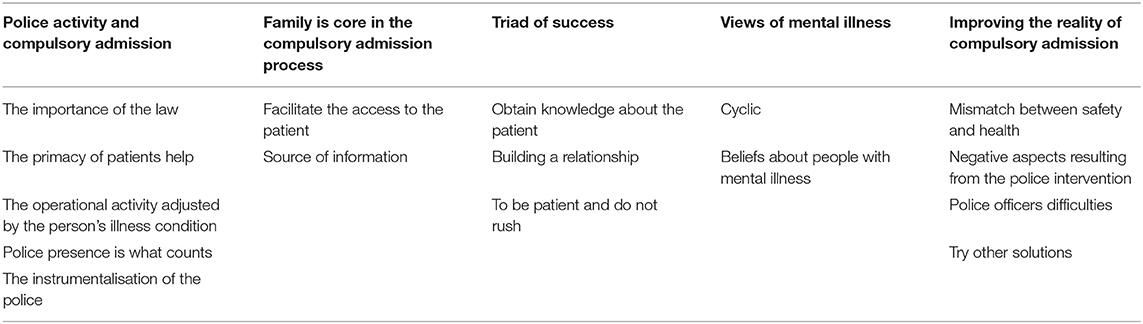

Five themes emerged from the analysis of the data: “Police activity and compulsory admission,” “Family is core in the compulsory admission process,” “Triad of success,” “Views of mental illness,” and “Improving the reality of compulsory admission.” (Table 1).

Police Activity and Compulsory Admission

Police activity inherent in compulsory admissions requires very specific characteristics of police officers. Police activity is ruled by a Mental Health Law which determines the exact form and range of their actions. Yet, they are required to deal with the behavior of a person that has not committed a crime, but who may require urgent care for their mental illness. Police officers are therefore placed in a very challenging situation where they have to balance the law, dealing sensitively with an acutely ill person and fulfilling their duty (Table 2).

The Importance of the Law

The existence of a Law that regulates the compulsory admission is the cornerstone of the police activity. It gives them the ability and legitimacy to deprive someone's freedom in order to take them to a hospital to be seen by a doctor. Police officers in this study highlighted this legal legitimacy as a key factor, as in its absence they are unable to protect and help the person. Another important consideration for the police officers is they guarantee freedom “deprivation” rather than a “detention.” This entails the difference between a criminal detainee and a mentally ill person who has to be deprived of their freedom to seek medical support. This legal difference is well-recognized by the police officers and is enforced in their interventions.

The Primacy of Patients Help

The intervention of the police in mental health is shaped by the principle of helping others. In this case they are helping a person who suffers from a mental disorder and does not have the ability to recognize they are ill and need treatment. This is the starting point of the police approach to compulsory admission and is essential to a humanized interaction. Understanding mental illness and how it influences a person's cognitions and behaviors supports a more empathic interaction rather than what is seen as the typical authoritative police approach in which criminal people are detained. This understanding that a person's behavior is just the expression of their illness and a way to express the need of help shapes their whole operation and individual conduct.

The Operational Activity Adjusted by the Person's Condition

The existence of mental illness is a conditioner of the police officers' attitudes toward a person with mental illness subject to police transportation. Police officers seek a low profile approach, avoiding using instruments of authority (such as their police uniform, the police vehicle cage or handcuffs), in order to respect the patient's privacy.

The Presence of the Police Is What Counts

Police officers recognize that simply their presence, without any active control measure, has a positive impact on the person's behavior. The police escort results in the patients having a more controlled, submissive and respectful behavior, which maintains everyone's safety.

The Instrumentalisation of the Police

Despite the core role of police officers in the compulsory admission process and their privileged access to the patient's social background, police officers emerge and perceive their importance only as a law's tool, where their function is to fulfill their task: escort the patient to the hospital.

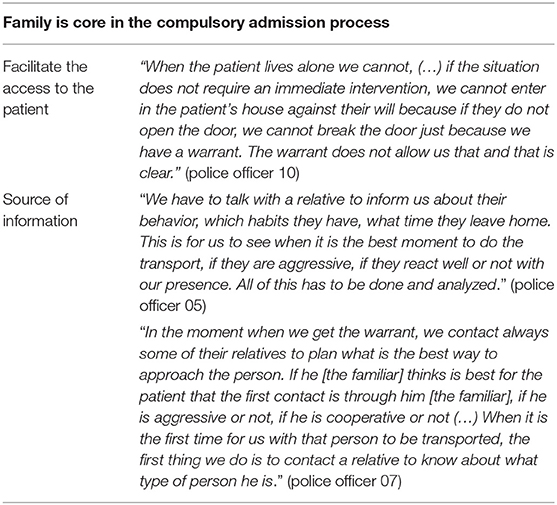

Family Is Core in the Compulsory Admission Process

Family plays an important role for police intervention in the compulsory admission process, as they provide detailed and present information about the patient. This information is very important for police officers when preparing for their interactions with the person who is unwell. Family members can also provide direct access to the physical space of the patient (Table 3).

Facilitate the Access to the Patient

The Portuguese legal framework on compulsory admission does not allow police officers to force the entrance on a patient's home. This means that the involvement of significant others of the patient are crucial to gain access to them, typically a relative. Without access to the patient's home, the police officers have to wait until the patient is on a public highway in order to transport them to the hospital.

Source of Information

The amount of information that is provided to the police officers about the patient is usually scant. Patient's family or friends are a rich source of information about patient's personality, emotional state on that day, and informs their decision about when best to execute the warrant.

The involvement of family in the compulsory admission process is crucial to reach the person in a more effective manner, and to reduce the risk of any injuries or the need for physical force.

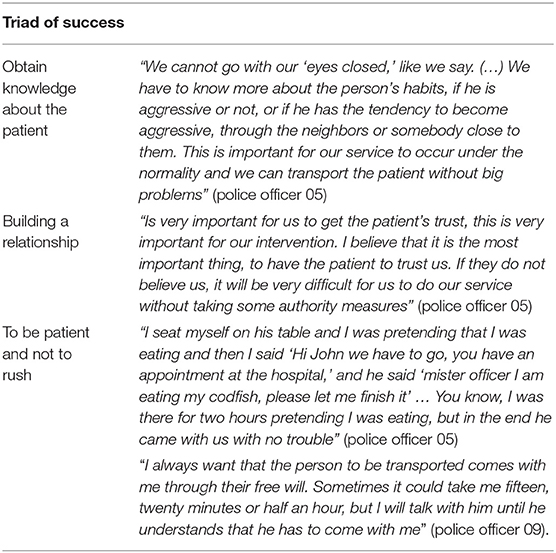

Triad of Success

Transporting someone for compulsory admission is a challenging process given the complex symptoms exhibited by these patients and their social situation. Police officers are faced with unknown circumstances, and so adopt strategies to minimize the risks to themselves and to ensure an effective intervention (Table 4).

Obtain Knowledge About the Patient

The knowledge that they obtain about the patient is very important for the success of their intervention. This includes gathering information about the patient's behavior, habits, people that they live with and factors that will shape the way that the person will react to their approach. Police officers often obtain information from family members, however some patients live alone or do not have family. In these occasions, police officers have to use all the other resources available to get some insight into the person.

Building a Relationship

Since the first moment that police officers approach the patient, their objective is to build a rapport with the patient. This relationship building process and sense of patient's trust in the police officer is very time consuming. Nevertheless, for police officers this is a crucial factor in their intervention, and without it the trust in their approach can be compromised.

To Be Patient and Do Not Rush

The complex layout of the police activity under compulsory admission tasks requires a lot of sensitivity, patience and good communication skills from police officers. This police intervention is the most time consuming operation for Portuguese police officers who often are rushed in to solve challenging situations. Yet, in these cases, patience and dialogue are their only tool and can help them come across more as peers, which differs to their usual demeanor in the other types of police work they do. Establishing a conversation with a person with a serious mental disorder can be challenging, but also gives the police a sense of control over the situation. This is their strategy to understand the patient and gain their trust, allowing them to co-operate and accept that they need to leave with the police. This makes police officers more confident about dealing with the process.

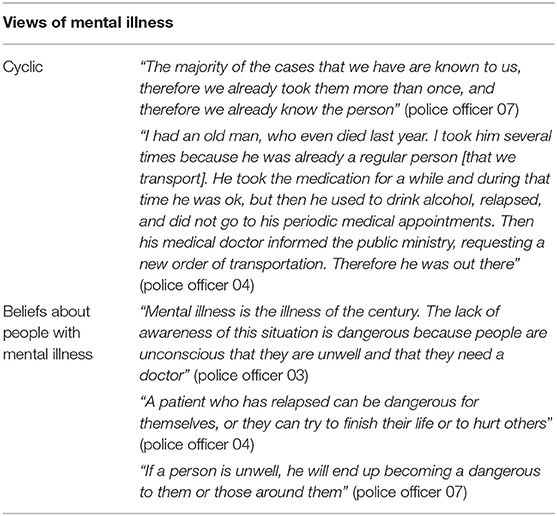

Views of Mental Illness

Police perceptions and beliefs about mental illness and about people with serious mental disorders facilitate better understanding of the patients' behavior and attitudes (Table 5).

Cyclic

Mental illness is perceived by police officers as cyclic, as they often transport the same patients in different periods (or relapses) of their illness. This cycle, characteristic of compulsory admissions, means police officers become an active agent of patient's treatment, although in a reactionary form during a crisis.

Beliefs About People With Mental Illness

Portuguese police officers see people with mental disorders as unpredictable, dangerous and with lack of insight about their illness and the need of treatment.

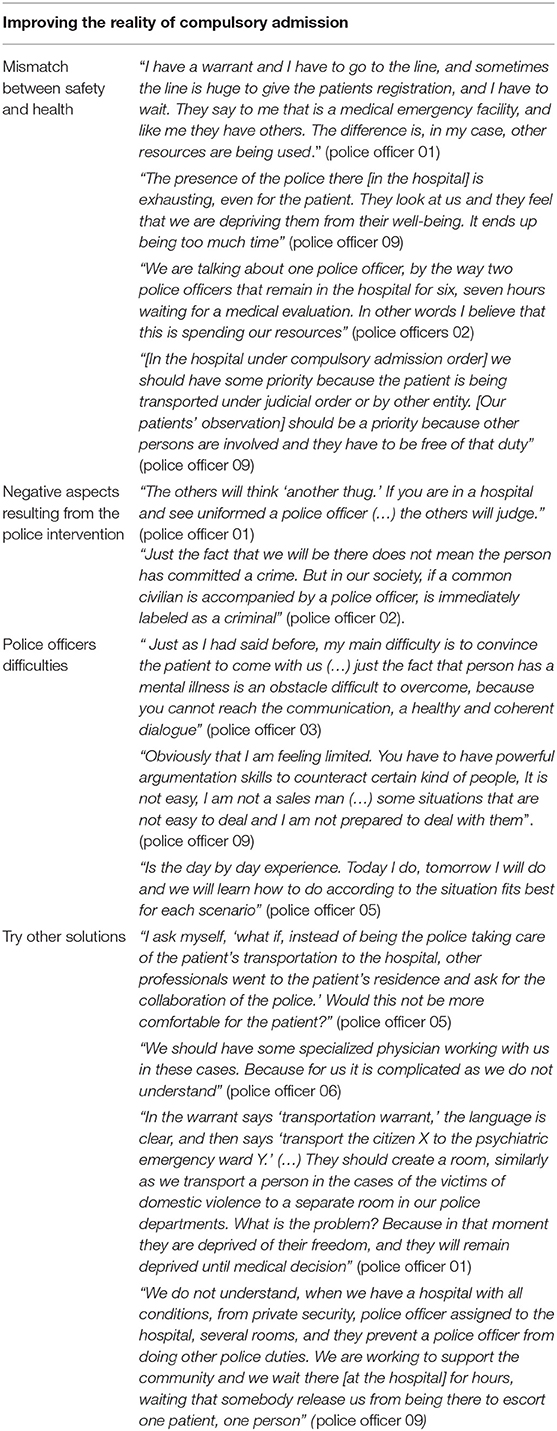

Improving the Reality of Compulsory Admission

Police officers take responsibility for the patients' transportation until they reach the nearest psychiatric emergency ward for medical evaluation. Once there, police officers are responsible for the patient's deprivation of freedom and restitution (if required). This means that police officers have to remain with these patients and be present in almost all stages of a patient's compulsory admission. Therefore, police officers are able to provide a valuable insight into what could be improved in this process (Table 6).

Mismatch Between Safety and Health

The controversy of compulsory admission for police officers is the shift from providing security to medical support. The hospital interaction is perceived by police officers as resource and time consuming. They strongly felt that patients under compulsory admission should have priority over other patients because they are there under a judicial order. The presence of the police in the hospital is perceived by the police officers to have a negative impact on the patient, being an expenditure of police resources, with many experiencing it like being detained.

Negative Aspects Resulting From the Police Intervention

Despite the care that police officers have when dealing with a person with mental illness, using a powerful institution which deals with the criminal world (i.e., the police), could have a negative impact upon the person that is being transported for medical evaluation.

Police Officers Difficulties

The interaction between police officers and people with mental disorders involves a special dynamic. Police officers have to transport the patient to the nearest psychiatric emergency service without any incident, which involves the person following their orders ideally in their own free will. The communication process is not easy, and police officers feel poorly prepared to do this.

These feelings of poor preparation can result from police officers' misunderstanding and/or lack of training on the behavior of people with mental illness. On the other hand, compulsory admission is not the core of police activity and the numbers of such admissions are low. Police officers learn how to deal with these patients from their own experiences.

Try Other Solutions

Police officers give suggestions to improve the compulsory admission process, which does not involve excluding police officers from the equation or discharging their responsibilities as police. They instead focus on patients' care improving their access to the mental health system. Their suggestions especially focused on police officers presence in hospital, which they express indignation with as it is a misuse of their resources and impacts their wider police duties.

Discussion

Key Findings

This study has raised awareness to the perceptions of police officers in dealing with compulsory treatment. Police officers felt confident about using Mental Health Law to approach these patients, which empowered them to help manage patients' behavior. However, they felt unprepared when dealing with the patients' behavior when this became challenging for them. Furthermore, police officers perceived patients as people who are unwell and require treatment. Police officers expressed that having an empathic approach, keeping a low profile, having a respectful interaction (e.g., using dialogue, patience and information about the person) was their main strategy. This demonstrates that police officers take special care when transporting patients against their will. Although they understand how mental illness can influence a person's cognition and behavior, they showed their own perceptions about mental illness and such patients (perceived as unpredictable, dangerous and without the capacity to judge their health status). Finally, our findings highlight their desire for increased support from other mental health professionals, for the process to be more efficient, and use less police resources. This would allow a balance between security and medical assistance, prioritizing the latter.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge this is the first study in Portugal that has focused on police officers and their interactions with people with serious mental disorders under compulsory admission, and therefore these findings add to a very limited literature base and hopefully set grounds for further work. The setting of this study is another strength as it included a wide range of police departments and police officers that perform compulsory admissions in Porto, including police officers with vast experience in this field. The geographical coverage of the study is also a strength, since different geographical areas may represent different social frameworks and provides us with rich and detailed information about the phenomena.

The study had however some limitations. Firstly, the sample of police officers interviewed was relatively small and did not allows us to explore and compare the differences in police officers views toward compulsory treatment, and whether this varied on the number of compulsory treatments they had previously carried out or their personal characteristics. Secondly, the sample targeted Porto's police departments and there is a possibility that in other areas of Portugal, with different characteristics, the experience of police officers may be different. Finally, our study only involved PSP (Policia de Segurança Pública) police officers. Other police officers from different police forces, like GNR (Guarda Nacional Republicana) who receive military training, may experience the compulsory admission process in a different way.

Comparison With the Literature

In our study, police officers in Portugal expressed special care and understanding of patient's medical needs, promoting a collaborative relationship in what is an asymmetrical power relationship by nature, using tools, such as dialogue, patience, building a positive rapport and gathering information about the patient beforehand. This emotional bond with a person with a mental disorder has also been shown in research in other countries, such as with police officers in the United Kingdom (UK), where they express the desire to help and to have empathy and understanding of people with mental disorders (25). A gentle communicative style is required to gain trust, rapport and compliance from the person under compulsory admission (37). The strategy of using dialogue and giving time to patients to explain themselves is perceived by people with a serious mental disorder as a more humane treatment (38, 39). For patients, being treated as humans is crucial to perceive the interaction as positive and for that, factors, such as communication style, being listened to, gentle handling, putting them at ease and not rushing things are key (37, 39). This procedural justice activity framework is crucial for the patient's cooperation and influences perceptions of police legitimacy. When the police intervention is grounded in a procedural justice approach, the quality of police-citizens interaction is enhanced (26) and people voluntarily comply with the police (8). Procedural fairness may assume an important role in maintaining the person's identity in the community, enhancing the person's value, and may facilitate their involvement in the treatment with future repercussions in treatment adherence (8).

Furthermore, our results in this study show that the involvement of the family in this process has emerged as a core feature in this police intervention, given that it is a useful source of information about the patient and a relevant link and resource in the process. Certainly, family and social support is a cornerstone of the Portuguese mental health care, especially in the case of people with serious mental disorders (40). This is in line with the findings from previous research, which had already highlighted the importance of family, as having a central role in recovery. Its involvement is seen as a valuable and qualified resource, responsible for assisting with the care provision (41). Importantly, the way in which a family starts a compulsory admission process has an effect on how individuals consider the first days of admission and is decisive in the patient's whole experience (42). It has been emphasized already that working in partnership and having discussions between the staff and the family members contributes to the development of best practice (43), to deliver safe and effective interventions (41). Despite the importance of family in mental health care, some families in London reported that they are treated as an irrelevant and troublesome part by the British mental health system (44).

In Portugal, seeking further information about the patients and the family involvement in the process is current practice in Portuguese police compulsory admission interventions and seems to be one strategy to a successful intervention. From a patient' perspective, it is also important that police officers have access to some personal information prior to their arrival to the scene, in order to know how to handle the person, how to communicate and to keep the situation under control. Yet, this amount of information should be properly handled by appropriately trained police (45). Without this, patients could be put at a high level of risk (38).

Our findings indicate that police officers in Portugal acknowledged that their presence has a positive impact on the person's behavior, resulting in a more controlled, submissive and respectful attitude. On the other hand, some police officers perceived that their presence could have a negative impact upon the person that is being transported for medical evaluation.

Hospital admission represents a significant event in the lives of people with serious mental disorders (3). It is reported by many as a traumatic process, and signifies a loss of patient's autonomy (42). However, “objective” coercive measures do not seem to be related with reduced satisfaction in people who are deprived of their freedom to receive medical treatment (46), but “perceived” coercion seems to be (47). This suggests that measures engaged to promote patient's self-control, such as providing explanations and involving them in the decision-making (42), may decrease the level of perceived coercion in the process of compulsory admission, and may increase the patient's satisfaction with their care and the treatment overall (46). Improving patients' satisfaction with care during the compulsory admission process is important not only to provide the highest quality and humane service to patients who require care, but also because low satisfaction levels are linked with poor engagement with services and repeated involuntary admissions (48, 49).

Importantly, the literature reveals that to be in police custody can be experienced as shocking, humiliating, intense or forceful, especially if the patient was not violent, and even if the police officers were kind and gentle during the process (37). In fact, a long period of time in custody, especially in suicidal patients, might increase their mental distress (44). Police officers in the UK acknowledge that a person with mental health problems may be traumatized by the police intervention and that, as police officers, they were frequently perceived as a threat by such patients (25). Regardless of this, police officers did not want to cause or prolong distress for these people, but felt they were frequently placed in situations where they were the only service available to help people in crisis (25). This is perceived by police officers (25) and patients (50) as a consequence of the failure of health services, and the fact that they are not mental health specialists (51).

The idea that police officers should not be responsible for mental health patients in crises is shared by police officers in Greece (16), and in the UK (25). Particularly in the UK they emphasize that they are put far beyond the initial crises stage and that police and medical professionals should work together to get a positive outcome, instead of unnecessary arrests (25). Police officers reported dissatisfaction with the process of getting a person into a treatment facility (52), due to concerns about police time and resources consumption (16, 53). Feeling unsupported is not only about lack of medical support or about the services provided, it is also about the background information about the person, and the feedback on the situation (53).

Although Portuguese police officers feel that the health system does not respond appropriately to the police force and to the patients' requirements, they express disappointment especially for the negative consequences this has on police officers wider duties and patients distress.

Implications of the Findings for Practice, Polices, and Research

Our study shows that interventions for police officers are still necessary in order to improve the compulsory admission process, such as: (i) providing adequate formal training and education on mental health that can help change the police misperceptions about people with serious mental illness, preparing the police officers to deal with patients' challenging behavior; (ii) improve communication and cooperation between the police, the medical community and social service providers, considering alternatives to improve their work and most importantly patients' care; and (iii) improve the conditions at the hospital emergency departments, so that patients referred compulsorily, are assessed as soon as possible.

Police officers expressed in this study that the existence of a law can give them legitimacy to deprive a person's freedom, although this is not a detention. This legal difference is well-recognized by police officers and is enforced in their interventions. Consequently, the police approach a person with mental illness by explaining that their function is not to arrest them, but instead to take them to a hospital for medical evaluation with an order determined by law. In this way the legitimacy of the intervention is legally guaranteed and police officers remain neutral in the decision-making process of compulsory admission. This has an important role in the patients' behavior and in the police confidence in managing this. In fact, the impact of the legislation in the patients' behavior and their perceptions of compulsory admission should be further studied. It seems that patients awareness of the legal order and of police officers responsibilities (i.e., once the patients realize that it is a legal order and that the police are just doing their job), they tend to improve cooperation and their experience (39).

Using the police to transport mentally unwell people in crisis represents a major expenditure of police resources, occasionally with some negative impact upon the patients, given their lack of preparation and the lack of support from mental health professionals. Therefore, it is important to sensitize police officers to the importance of their task and actively engage them to collaborate with mental health professionals. In general, police officers share the belief that it is not their responsibility to deal with mentally ill people in crises. It is imperative to change this to guarantee a more effective response in the compulsory admission process and a faster access of patients to the mental health services. A more efficient approach would reduce the time that police officers are away from their other usual duties, since the time that they spend during this task was their biggest complaint. The creation of joint task forces between police and mental health professionals could be highly beneficial, responding faster and reducing stigma/discrimination (51). A multi-agency strategy approach could also enhance the legitimacy of the intervention and contribute to the procedural fairness of the compulsory admission process (26). This suggests the need to further study the effectiveness of different approaches. Possibly that could lead to a change in the Portuguese mental health legal framework, where frontline medical provision is supported by police officers, if required, and social services. Future qualitative research with larger samples of police officers, and from different police forces, could further explore and compare the differences in their views toward compulsory treatment, and whether this is affected by the number of compulsory treatments they had done, by their background and/or personal characteristics.

Finally, our findings show that the police officers in Portugal approach compulsory admission as a help call, with full understanding that there is a person who needs medical attention and has to be treated with empathy, dignity and respect. They seek a humane interaction using all the means at their disposal to do the transport with minimal negative effects on them, and without use of force. Creating a rapport and trust are highlighted as crucial to enhance a relationship with a patient. For this, Portuguese police officers use dialogue as a strategy, but this can be too time consuming and a challenging process which they can experience as a major difficulty. For a better interaction, formal and standardized training and educational programs should be implemented to help increase the confidence levels of police officers during their interactions with people with mental disorders (52). Although they express that they rarely have to use force in these processes, Portuguese police officers perceive people with serious mental disorders as unpredictable, dangerous and without the capacity to evaluate their mental state. Their perceptions about mental illness may also result from their lack of knowledge and experience. The way police officers perceive people with mental illness is of major concern since insufficient mental health education could put people with serious mental disorders at risk (38), and enhance the chances of physical confrontation, as it may result in a situation where both parties misunderstand each other (14). Therefore, it is vital to further assert in the difficulties, concerns and beliefs of police officers across the country and beyond, and complement this research with further studies focusing on patients' perceptions about this police intervention. This input from different sectors is imperative to the development of formal and standardized education and training programs that would help police officers: (i) reducing the use of measures that may increase perceived coercion; (ii) changing their misperceptions about people with serious mental disorders; and (iii) helping them to determine the best strategy to provide the best care.

Conclusion

This study illustrates Portuguese police officers experiences and perceptions during the process of compulsory admission, providing more information about this understudied area. It also highlights their efforts for a humane and empathic treatment that they provide when transporting people for compulsory admissions. Some aspects of the police intervention should be further developed for an improved and swifter process when transporting patients, and to promote a more humane and effective approach.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee (203/2017) of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar (ICBAS) of the University of Porto and a favorable authorization was obtained from the National Formation Department of PSP (3F05-2017), prior to the interviews. Invited participants received information about the purpose of the study and the research method verbally and through information sheets prior to the interview. The contact details of the researcher were given to the interviewees for any further questions prior or after the interview. They were also informed about their right to withdraw their consent and withdraw from the study without any penalties and that confidentiality would be maintained. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the interviews.

Author Contributions

RS and MPC conceived the study. RS made all the contacts with the police, performed the interviews and led the analytic process. RS and MPC analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support received in the Master on Legal Medicine at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar (ICBAS) at the University of Porto. This article reports the research's Master work of RS under the supervision of MPC.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00187/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Salize HJ, Dreßing H, Peitz M. Compulsory Admission and Involuntary Treatment of Mentally Ill Patients-Legislation and Practice in EU-Member States. Central Institute of Mental Health Research Project Final Report, Mannheim, Germany. (2002). p. 15.

2. Rights F-EUAfF. Involuntary Placement and Involuntary Treatment of Persons With Mental Health Problems Vienna: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2012).

3. Wyder M, Bland R, Crompton D. The importance of safety, agency and control during involuntary mental health admissions. J Mental Health. (2016) 25:338–42. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1124388

4. Molodynski A, Turnpenny L, Rugkasa J, Burns T, Moussaoui D. Coercion and compulsion in mental healthcare-an international perspective. Asian J Psychiatry. (2014) 8:2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.08.002

5. Valenti E, Banks C, Calcedo-Barba A, Bensimon CM, Hoffmann KM, Pelto-Piri V, et al. Informal coercion in psychiatry: a focus group study of attitudes and experiences of mental health professionals in ten countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2015) 50:1297–308. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1032-3

6. Katsakou C, Rose D, Amos T, Bowers L, McCabe R, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric patients' views on why their involuntary hospitalisation was right or wrong: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:1169–79. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0427-z

7. Katsakou C, Priebe S. Patient's experiences of involuntary hospital admission and treatment: a review of qualitative studies. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. (2007) 16:172–8. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00004802

8. Watson AC, Angell B. Applying procedural justice theory to law enforcement's response to persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. (2007) 58:787–93. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.787

9. Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Ottati V. Police responses to persons with mental illness: does the label matter? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. (2004) 32:378–85.

10. Hails J, Borum R. Police Training and specialized approaches to respond to people with mental illnesses. Crime Delinq. (2003) 49:52–61. doi: 10.1177/0011128702239235

11. Iacobucci F. Police encounters with people in crisis. In: Service TP, editor. (2014). Available online at: https://www.torontopolice.on.ca/publications/ (accessed September 12, 2018).

12. Brink J, Livingston J, Desmarais S, Michalak E, Verdun-Jones S, Maxwell V, et al. A Study of How People with Mental Illness Perceive and Interact with the Police. Calgary, AB: Mental Health Comission of Canada (2011).

13. Moore R. European Police and Persons With Mental Illnesses. Policing and the Mentally Ill. Advances in Police Theory and Practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (2013). p. 39–62.

14. Ruiz J, Miller C. An exploratory study of Pennsylvania Police Officers' perceptions of dangerousness and their ability to manage persons with mental illness. Police Q. (2004) 7:359–71. doi: 10.1177/1098611103258957

15. Green TM. Police as frontline mental health workers. The decision to arrest or refer to mental health agencies. Int J Law Psychiatry. (1997) 20:469–86. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2527(97)00011-3

16. Psarra V, Sestrini M, Santa Z, Petsas D, Gerontas A, Garnetas C, et al. Greek police officers' attitudes towards the mentally ill. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2008) 31:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.11.011

17. Oxburgh L, Gabbert F, Milne R, Cherryman J. Police officers' perceptions and experiences with mentally disordered suspects. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2016) 49:138–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.08.008

18. Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. (2002) 1:16–20.

19. Corrigan PW, Bink AB. The stigma of mental illness. In: Friedman HS, editor. Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2nd ed. Oxford: Academic Press (2016). p. 230–4. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00170-1

20. Burkhardt BC, Akins S, Sassaman J, Jackson S, Elwer K, Lanfear C, et al. University Researcher and Law Enforcement Collaboration: lessons from a study of justice-involved persons with suspected mental illness. Int J Offen Ther Comp Criminol. (2015) 61:508–25. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15599393

21. Kesic D, Thomas SD, Ogloff JR. Mental illness among police fatalities in Victoria 1982–2007: case linkage study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2010) 44:463–8. doi: 10.3109/00048670903493355

22. Saleh AZ, Appelbaum PS, Liu X, Scott Stroup T, Wall M. Deaths of people with mental illness during interactions with law enforcement. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2018) 58:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.03.003

23. Watson AC, Morabito MS, Draine J, Ottati V. Improving police response to persons with mental illness: a multi-level conceptualization of CIT. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2008) 31:359–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.06.004

24. Compton MT, Demir Neubert BN, Broussard B, McGriff JA, Morgan R, Oliva JR. Use of force preferences and perceived effectiveness of actions among Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) police officers and non-CIT officers in an escalating psychiatric crisis involving a subject with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:737–45. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp146

25. Mclean N, Marshall LA. A front line police perspective of mental health issues and services. Crim Behav Mental Health. (2010) 20:62–71. doi: 10.1002/cbm.756

26. Mazerolle L, Bennett S, Davis J, Sargeant E, Manning M. Procedural justice and police legitimacy: a systematic review of the research evidence. J Exp Criminol. (2013) 9:245–74. doi: 10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

27. Tyler T. Procedural justice and policing: a rush to judgment? Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. (2017) 13:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113318

28. Tyler TR. Enhancing police legitimacy. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. (2004) 593:84–99. doi: 10.1177/0002716203262627

29. Lei de Saúde Mental 36/98 de 24 de julho (1998). Emissor:Assembleia da República; Diploma Type:Lei. Number: 36/98; 3544–3550. Diário da República n.° 169/1998, Série I-A de 1998-07-24. Available online at: https://data.dre.pt/eli/lei/36/1998/07/24/p/dre/pt/html

30. Lei de Bases da Saúde 48/90 de 24 de agosto (1990). Emissor:Assembleia da República; Diploma Type:Lei. Number:48/90; 3452–3459. Diário da República n. 195/1990, Série I de 1990-08-24.

31. Mota JL. Discurso na sessão de encerramento. A Lei de Saúde Mental e o Internamento Compulsivo. Coimbra: Coimbra Editores (2000). p. 133–40.

32. Figueiredo D. Palavras finais do Prof. Doutor Jorge De Figueiredo Dias à conferência do Procurador-Geral da República. A Lei de Saúde Mental e o Internamento Compulsivo. Coimbra: Coimbra Editora (2000). p. 61.

33. Cunha R. Sobre o estatuto jurídico das pessoas afetadas de anomalia psíquica A Lei de Saúde Mental e o Internamento Compulsivo. Coimbra: Coimbra Editora (2000). p. 19–52.

34. Almeida F, Marques I, Castro S, Coelho C, Palha J, Leonor C, et al. Internamentos compulsivos no Hospital de Magalhães Lemos. Psiquiatr Just. (2008) 2:87–102.

35. Almeida F, Moreira D, Silva V, Cardoso A. Internamento compulsivo. Psiquiatr Psicol Just. (2012) 5:49–66.

36. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research–A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE Publications Ltd (2013). p. 382.

37. Bradbury J, Hutchinson M, Hurley J, Stasa H. Lived experience of involuntary transport under mental health legislation. Int J Mental Health Nurs. (2016) 26:580–92. doi: 10.1111/inm.12284

38. Boscarato K, Lee S, Kroschel J, Hollander Y, Brennan A, Warren N. Consumer experience of formal crisis-response services and preferred methods of crisis intervention. Int J Mental Health Nurs. (2014) 23:287–95. doi: 10.1111/inm.12059

39. Watson AC, Angell B, Morabito MS, Robinson N. Defying negative expectations: dimensions of fair and respectful treatment by police officers as perceived by people with mental illness. Adm Pol Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. (2008) 35:449–57. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0188-5

40. Almeida J. A saúde mental dos portugueses. Lisbon: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos (2018). p. 123.

41. Begum R, Riordan S. Nurses experiences of working in Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Teams with its additional gatekeeping responsibilities. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. (2016) 23:45–53. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12276

42. McGuinness D, Murphy K, Bainbridge E, Brosnan L, Keys M, Felzmann H, et al. Individuals' experiences of involuntary admissions and preserving control: qualitative study. BJPsych Open. (2018) 4:501–9. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.59

43. Ness O, Karlsson B, Borg M, Biong S, Hesook SK. A crisis resolution and home treatment team in Norway: a longitudinal survey study Part 1. Patient characteristics at admission and referral. Int J Mental Health Syst. (2012) 6:18. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-6-18

44. Adebowale L. Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing Report. Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing (2013). Available online at: https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/independent-commission-mental-health-and-policing-report (accessed October 28, 2018).

45. Livingston JD, Desmarais SL, Verdun-Jones S, Parent R, Michalak E, Brink J. Perceptions and experiences of people with mental illness regarding their interactions with police. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2014) 37:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.003

46. Bainbridge E, Hallahan B, McGuinness D, Gunning P, Newell J, Higgins A, et al. Predictors of involuntary patients' satisfaction with care: prospective study. BJPsych Open. (2018) 4:492–500. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.65

47. Strauss JL, Zervakis JB, Stechuchak KM, Olsen MK, Swanson J, Swartz MS, et al. Adverse impact of coercive treatments on psychiatric inpatients' satisfaction with care. Commun Mental Health J. (2013) 49:457–65. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9539-5

48. van der Post LF, Peen J, Visch I, Mulder CL, Beekman AT, Dekker JJ. Patient perspectives and the risk of compulsory admission: the Amsterdam Study of Acute Psychiatry V. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2014) 60:125–33. doi: 10.1177/0020764012470234

49. Setkowski K, van der Post LF, Peen J, Dekker JJ. Changing patient perspectives after compulsory admission and the risk of re-admission during 5 years of follow-up: The Amsterdam Study of Acute Psychiatry IX. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2016) 62:578–88. doi: 10.1177/0020764016655182

50. Highet N, G McNair B, Thompson M, Davenport T, Hickie I. Experience With Treatment Services for People With Bipolar Disorder. Sydney: The Medical Journal of Australia (2004). p. S47–51.

51. Kirubarajan A, Puntis S, Perfect D, Tarbit M, Buckman M, Molodynski A. Street triage services in England: service models, national provision and the opinions of police. BJPsych Bull. (2018) 42:253–7. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2018.62

52. Wells W, Schafer JA. Officer perceptions of police responses to persons with a mental illness. Policing. (2006) 29:578–601. doi: 10.1108/13639510610711556

Keywords: law, experience, mental illness, police officers, coercion, compulsory, treatment, Portugal

Citation: Soares R and Pinto da Costa M (2019) Experiences and Perceptions of Police Officers Concerning Their Interactions With People With Serious Mental Disorders for Compulsory Treatment. Front. Psychiatry 10:187. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00187

Received: 04 January 2019; Accepted: 14 March 2019;

Published: 18 April 2019.

Edited by:

Christian Huber, University Psychiatric Clinic Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Edwina Light, University of Sydney, AustraliaLaura Farrugia, University of Sunderland, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2019 Soares and Pinto da Costa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruben Soares, cnViZW5zb2FyZXpAZ21haWwuY29t

Ruben Soares

Ruben Soares Mariana Pinto da Costa

Mariana Pinto da Costa