94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 18 December 2018

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00697

This article is part of the Research Topic Cognition in Mood Disorders View all 17 articles

Background and Objective: The default mode network (DMN) may be an important component involved in the broad-scale cognitive problems seen in patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression. Nevertheless, information is scarce regarding the changes in network homogeneity (NH) found in the DMN of these patients. Therefore, in this study, we explored the NH of the DMN in patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression.

Methods: The study included 66 patients and 74 control participants matched by age, gender, educational level and health status who underwent resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) and the attentional network test (ANT). To assess data, the study utilizes NH and independent component analysis (ICA). Additionally, Spearman's rank correlation analysis is performed among significantly abnormal NH in depression patients and clinical measurements and executive control reaction time (ECRT).

Results: In comparison with the control group, patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression showed lower NH in the bilateral angular gyrus (AG), as well as increased NH in the bilateral precuneus (PCu) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Likewise, patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression had longer ECRT. No significant relation was found between abnormal NH values and the measured clinical variables.

Conclusions: Our results suggest patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression have abnormal NH values in the DMN. This highlights the significance of DMN in the pathophysiology of cognitive problems in depression. Our study also found alterations in executive functions in patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression.

Depression is a frequent complex disorder of unclear pathogenesis which is typically characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest, reduced energy, a pervasive loss of pleasure, cognitive impairment, and vegetative symptoms (1, 2). Depression is currently known to affect a large number of people globally (http://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression), being one of the main causes for disability worldwide and having a substantial socio-economic burden (3). Currently available treatments for depression are far from ideal due to high recurrence rates along with frequent and intolerable side-effects (4).

Increasing evidence has shown depression may be regarded as a disorder of neural networks (5, 6). In particular, the default mode network (DMN) has received growing attention. Previous research has found that the DMN is significantly involved in the neurobiology of depression and has been proposed as a biomarker for treatment response, as DMN activity appears to predict levels of depressive rumination (2, 7–9). The DMN comprises several structures: the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), the precuneus (PCu), the anterior/posterior cingulate cortex (A/PCC), and the medial, lateral and inferior parietal cortex (10–13). Recently, the lateral temporal gyrus and the cerebellar crus 1 and 2 have been found to participate in DMN connectivity(13, 14). DMN activity is usually higher at rest and decreases during task-related cognitive processes (15). The DMN has been correlated with monitoring external environments, keeping self-consciousness, producing spontaneous thinking, self-related feelings, memory, the process of cognition, negative ruminations, complex self-referential stimuli, and some special mind-states (16–20).

Previous investigation on depression has demonstrated abnormal resting state connectivity in the DMN; however, findings remain inconsistent on whether connectivity is increased (21–23), decreased (24, 25) or even both (26, 27). Recently, a study reported no correlation between the MPFC and the PCC (28). These discrepancies may be due to several aspects. Furthermore, differences in methodology and limited sample sizes can significantly affect results. Factors such as drugs, treatment methods, illness duration and severity can also contribute to DMN abnormalities. For example, antidepressants can reduce functional connectivity in the DMN (29, 30), while both electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation have been observed to change functional connectivity in the DMN (31, 32). Hence, studies on first-episode treatment-naive subjects with depression may have the advantage of lessening confounders.

Network homogeneity (NH) has been widely studied in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, somatization, schizophrenia, and their unaffected siblings (6, 33–40). This method studies a given network without specifying the requirement of localization of network abnormalities. Thus, it assesses the homogeneity of a whole network, an aspect of intrinsic network organization that has long been overlooked. As a voxel-wise measurement approach, NH correlates with all other voxels in a provided interest network. For a given voxel, its average correlation is regarded as an NH value. Homogeneity is defined as the time series comparability for a provided voxel or others in a given network. DMN is associated with cognitive functioning, especially executive function. When the brain is performing tasks, the DMN is negatively activated. Based on studies of DMN abnormalities in patients with depression (40), we hypothesizes that patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression show abnormal DMN homogeneity, which may be related to clinical variables such as illness severity and executive control reaction time (ECRT).

All subjects signed the written informed consent before participating in this investigation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Guangxi Medical University and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

This study included 66 patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression and 74 control participants, all of them recruited from the Department of Neurology, Psychology and Radiology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. Patients were diagnosed following criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), by independent assessments from two psychiatrists. We used the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) to evaluate depression severity. All patients had total scores ≥17 in the HRSD-17 on the day of MRI evaluation. The exclusion criteria were: left-handedness; family history of neurological disorders, severe physical illnesses and substance abuse; pregnancy; findings of abnormal cerebral structures after the initial MRI scanning, and the presence of other psychiatric disorders, such as personality disorders or schizophrenia and related disorders. In total, 74 individuals were included in the control group, matched for age, gender, educational status and overall health, and it is noteworthy that exclusion standards are the same for depression patients.

The attentional network test (ANT) was designed by Fan et al. (41), which was presented using Eprime and E-Studio software (Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The standard procedures for ANT were followed (https://www.sacklerinstitute.org/cornell/assays_and_tools/ant/jin.fan/). In the central testing screen, a “+” sign was placed and regarded as the fixation point. A stimulus signal could be generated above or below the central screen in the form of a target → or a foil *. Four situations involved foils: No foil, one foil in the central part, one foil above the central screen and another one below it, and one foil either above or below the central screen. Arrows could appear in the following ways: A single arrow, five arrows in a direction, and five arrows in different directions. Subjects were required to assure target orientation correctly and quickly. ECRT was calculated by subtracting the consistent arrow direction reaction time (RT) from the inconsistent arrow direction RT. Longer ECRT represents lower efficiency of the executive control network.

An Achieva 3TMRI scanner (Philips, Netherlands) was utilized for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI). Patients were asked to lie down and close their eyes but remain awake. A prototype quadrature birdcage head coil filled with foam was used to minimize head movement. Functional imaging had the following parameters: ratio of repetition time to echo time (TR/TE) (2,000/30 ms), slice thickness (5 mm), pitch (1 mm), field of view (240 × 240 mm) and flip angle (90°). On the structural scan (T1-weighted), the following settings were used: spin-echo sequence, repetition time (TR) = 20 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.5 ms, slice thickness = 1 mm, and field of view (FOV) = 24 × 24 cm.

Imaging data from the rs-fMRI was preconditioned using the data processing assistant for resting-state fMRI (DPARSF) software (42) in Matlab. The first 10 time points were removed, and slice time and head motion were rectified to adjust the time series of images so that the brain is in the same position in every image (43, 44). No participants had more than 2 mm of maximal displacement in the x, y, or z axes and more than 2° of maximal rotation. The structure of each patient was registered to its functional image. The structure of each patient was divided, and a template was created to normalize the structures of the patients after they were defined according to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard template, the standardization process of the spatial deformation of the modulation and the structure of the voxel size using 1 × 1 × 1 mm. Finally, the use of the structure of each patient to the function of the conversion matrix was also standardized to the MNI space. During the process of functional image normalization, head motion parameters, white matter signal, and cerebrospinal fluid signal were used as removal covariates (Nuisance regression), and voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm was used as functional covariate. The obtained images were subsequently smoothed with an 8 mm full width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel, band pass filtered (0.01–0.1 Hz), and linearly detrended to lessen the effect of low-frequency drifts and physiologic high frequency noise. Several spurious covariates were removed, including a signal from a region centered in the white matter, 6 head motion parameters obtained by rigid body correction, and a signal from a ventricular ROI. The global signal removal may introduce artifacts into the data and distort resting-state connectivity patterns. Furthermore, the regression of the global signal may significantly distort results when studying clinical populations. Therefore, the global signal was preserved (45, 46).

Independent component analysis (ICA) was performed using the Group ICA utility to remove DMN components in templates from the GIFT fMRI toolbox (http://mialab.mrn.org/software/#gica) (46). Three procedures from the GIFT toolbox were utilized for ICA analysis: data reduction, separation of independent components and back rebuilding. On the consideration of every component, the voxel-wise one-sample t-test set a statistical map and a threshold. Based on Gaussian random field (GRF) theory, p < 0.01 represents a significant statistical modification of multiple comparisons. Voxel significance meets requirements at values of p < 0.01, and cluster significance values for p < 0.01. The study created masks for the parts included in the DMN. Finally, after combination, the DMN masks were utilized in the NH analysis.

The results of NH analysis were computed through the application of an in-house script in Matlab (33, 34). The DMN masks showed correlation coefficients between a provided voxel and all others. There is a definition of the correlation coefficient in average as the homogeneity of the provided voxel. Then, the averaged correlation coefficients were converted into z values through z-transformation, promoting normal distribution. The resultant values generated the NH map that finally underwent z-transformation for group comparison.

The study computed demographic information such as age, gender, and education degree, as well as imaging data from the patient and control groups. The two-sample t-test was applied for the comparison of continuous variables, while the chi-square test was employed to compare categorical data by using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software. With the purpose of measuring the discrepancies in the NH regional group, the two-sample t-test assisted the individual-level NH map into one group-level voxel wise t-test analysis. Later, in the DMN mask, through voxel-wise cross-subject statistics, the two-sample t-test was employed to analyze the NH maps. GRF theory is applied into the modification of significance level (p < 0.01) for multiple comparisons. (GRF corrected, voxel significance: P < 0.001; cluster significance: P < 0.01).

NH values are withdrawn from abnormal values in brain regions. After the evaluation of data normality, Pearson correlations can be found among the variables with p < 0.05 in statistics using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software.

Demographic information of the study participants is presented in Table 1. There were no significant discrepancies among the three groups regarding gender, age, and education years. ECRT was longer in the patient group.

By employing ICA, DMN masks were removed from the control group. The parts involved in the DMN included the bilateral PCC/PCu, MPFC, ventral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), lateral temporal cortex, parietal lobes (medial, lateral, and inferior), and cerebellum Crus 1 and Crus 2 (Figure 1).

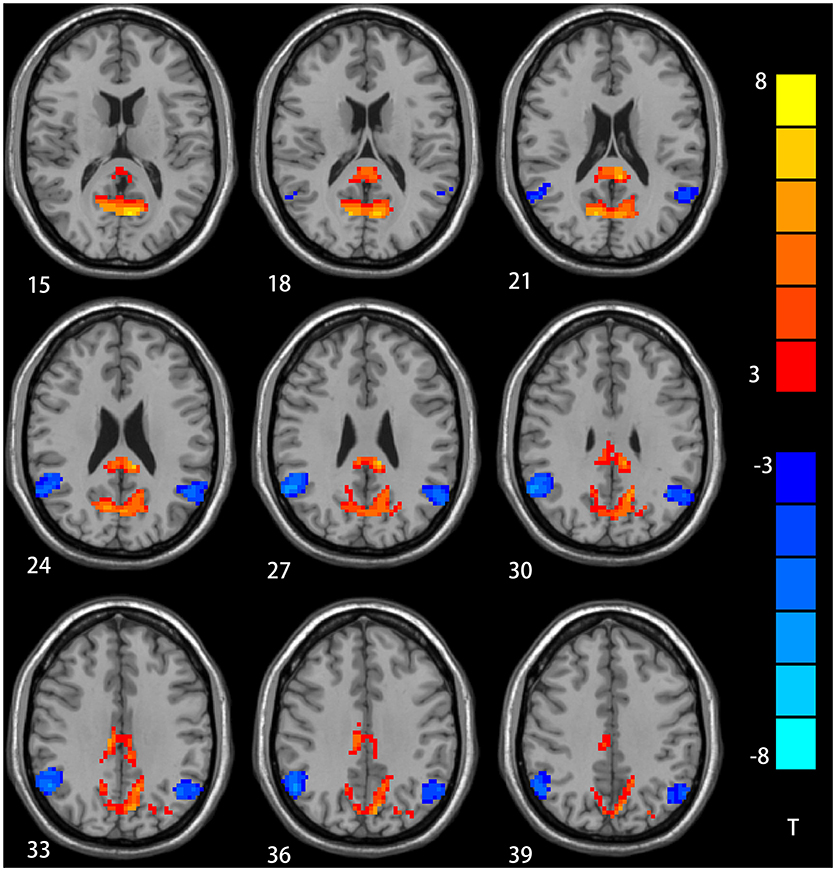

The two-sample t-test showed significant group discrepancies of NH values between patients and controls within the DMN masks. In comparison with the controls, patients with depression had lower NH in the bilateral AG and significantly higher NH in the bilateral PCC and PCu (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. NH differences in the bilateral angular gyrus, enhanced NH in the bilateral precuneus (PCu) and bilateral postal cingulum cortex (PCC) between depression group and control group in statistical maps (Blue denotes lower NH and red denotes higher NH. Meanwhile, color bars point T values obtained from two-sample t-test. NH is the abbreviation of network homogeneity).

Significant group discrepancies were found in the six regions where the averaged NH values were withdrawn (bilateral AG, bilateral PCC, and PCu). In the patient group, Pearson linear correlation analysis was implemented to explore the correlations among NH, ECRT, and illness severity. The results showed no significant correlations of NH with those clinical variables.

In this paper, NH was studied on the DMN of patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression. The latter showed significantly lower NH in the bilateral AG and significantly higher NH in the bilateral PCC and PCu compared to controls. These patients also had longer ECRT. However, no significant correlations were found among NH and illness severity or ECRT in any of the regions.

The cingulate gyrus is an important area where the frontal cortex, insula, amygdala, and hypothalamus interconnect. As a part of the limbic system, it participates in emotion regulation, cognitive function and self-control. PCC represents a core hub for the DMN and plays a key role in integrating self-relative information, retrieval of episodic memory, and autobiographical search. As reported by Maddock (47), unpleasant words can cause significant activation of PCC by task state-fMRI. On the other hand, Hagmann et al. (48) found that PCC can integrate information across the cerebral cortex through a graph theoretic analysis method. According to Marchetti et al. (49), lower fractional anisotropy (FA) values are found in PCC in major depressive disorder. PCC volume is significantly reduced in patients with depression (50, 51). The average metabolic rate of PCC appears to be increased in patients with depression, and can be reduced significantly by antidepressant treatment (52). In addition, a meta-analysis reported the PCC is reliably involved in autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation and theory of mind (53). On the other hand, many studies have observed that functional connectivity decreases in PCC in patients suffering with depression (21–24). One possible interpretation for this paradox is that there is a possible compensatory mechanism. However, some hold that increased PCC is an intrinsic characteristic of depression (54). Our findings suggest the increased NH in the bilateral PCC could contribute to depression.

The PCu—situated in the posterior DMN—intervenes in memory and processing of self-references, while its deactivation has been related to consciousness (55). Abnormal PCu activity can enhance self-references, which favors sleep disorders (56). In this study, we found that increased NH in bilateral PCu demonstrates decreased interaction with the DMN. At least two studies have found that abnormal PCu activity may be related to the genetic risk of depression (57, 58). Therefore, we surmise that increased NH values in the bilateral PCu might be associated with depression.

The AG, in the posterior of the inferior parietal lobe, is regarded as a main hub for various subsystems (59). The AG is involved in handling semantics, reading and comprehending words, dealing with numbers, retrieving memory, attention and spatial cognition, social cognition and inference (60). Mulders et al. (32) observed DMN coherence is significantly decreased in the AG in patients with depression. Similarly, Chen et al. found decreased connectivity in the AG within DMN inpatients suffering with first-episode, treatment-naive major depressive disorder, which is associated with higher autobiographical memory scores (61). Patients with depression are thought to have slower thinking and memory loss, which is associated with decreased NH values in bilateral AG.

It is universally acknowledged that the DMN is associated with executive functions, presenting increased activity at rest and decreased activity during the execution of oriented cognitive tasks (62, 63). Therefore, depression patients usually display functional executive impairment and longer ECRT. This parameter is measured by the ANT designed by Fan et al. (41). This test has been applied in the research of other conditions such as Parkinson's disease (64). Longer ECRT represents lower efficiency of the prompt executive control network. Damaged PCC/PCu can affect frontal lobe activity and disrupt execution functions (65). Based on these speculations, abnormal NH, ECRT and illness severity are assumed to be correlated. However, we found no correlations among these factors. This may be because the abnormal NH values in the DMN belong to a characteristic variety for those patients who are not limited by these factors or alternatively are due to the sample size.

Our study had a few limitations. The influence of physiological noises such as cardiac and respiratory rhythm cannot be completely removed. The sample size was notably restricted. Finally, our study focused only on alterations in the DMN, possibly neglecting significant changes in other brain regions.

Despite these limitations, our study results corroborate the importance of DMN in the pathophysiology of depression by highlighting the presence of abnormal NH values in the DMN of patients with first-episode treatment-naive depression. In addition, we have posited a method for the assessment of NH, which may improve the comprehension of the pathophysiology of depression in future studies.

YG designed experiment and wrote this article. MW, RY, YL, YY, and XC collected and analyzed these data. JZ guided the experiment and revised the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The investigation was supported by the grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81560223). The authors thank all individuals who served as study subjects as well as the reviewers for their proposals and criticisms.

1. Lebedeva AK, Westman E, Borza T, Beyer MK, Engedal K, Aarsland D, et al. MRI-based classification models in prediction of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in late-life depression. Front Aging Neurosci. (2017) 9:13. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00013

2. Bartova L, Meyer BM, Diers K, Rabl U, Scharinger C, Popovic A, et al. Reduced default mode network suppression during a working memory task in remitted major depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2015) 64:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.025

3. Michaud CM, Murray JL, Bloom BR. Burden of disease–implications for future research. JAMA (2001) 285:535–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.5.535

4. Smith GS, Kramer E, Hermann C, Ma Y, Dhawan V, Chaly T, et al. Serotonin modulation of cerebral glucose metabolism in depressed older adults. Biol Psychiatry (2009) 66:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.012

5. Hamilton JP, Chen MC, Gotlib IH. Neural systems approaches to understanding major depressive disorder: an intrinsic functional organization perspective. Neurobiol. Dis. (2013) 52C:4. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.015

6. Guo W, Liu F, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Yu L, Liu J, et al. Abnormal default-mode network homogeneity in first-episode, drug-naive major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e91102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091102

7. Mulders PC, van Eijndhoven PF, Schene AH, Beckmann CF, Tendolkar I. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depressive disorder: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 56:330–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.07.014

8. Hamilton JP, Chen G, Thomason ME, Schwartz ME, Gotlib IH. Investigating neural primacy in major depressive disorder: multivariate granger causality analysis of resting-state fMRI time-series data. Mol Psychiatry (2011) 16:763–72. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.46

9. Simon R, Engström M. The default mode network as a biomarker for monitoring the therapeutic effects of meditation. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:776. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00776

10. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2001) 98, 676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676

11. Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100

12. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage (2007) 37:1083–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041

13. Guo W, Liu F, Xue Z, Gao K, Liu Z, Xiao C, et al. Abnormal resting-state cerebellar-cerebral functional connectivity in treatment-resistant depression and treatment sensitive depression. Progr Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2013) 44:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.01.010

14. Krienen FM, Buckner RL. Segregated fronto-cerebellar circuits revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Cerebr Cortex (2009) 19:2485–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp135

15. Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME, et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2005) 102:9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102

16. Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron (2010) 65:550–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005

17. Spreng RN, Grady CL. Patterns of brain activity supporting autobiographical memory, prospection, and theory of mind, and their relationship to the default mode network. J Cogn Neurosci. (2010) 22:1112. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21282

18. Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:4259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071043098

19. Mason MF, Norton MI, Van Horn JD, Wegner DM, Grafton ST, Macrae CN. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science (2007) 315:393–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1131295

20. Cabeza R, Dolcos F, Graham R, Nyberg L. Similarities and differences in the neural correlates of episodic memory retrieval and working memory. Neuroimage (2002) 16:317–30. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1063

21. Eyre HA, Yang H, Leaver AM, Van Dyk K, Siddarth P, Cyr NS, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity in late-life depression: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2016) 189:126. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.011

22. Cha DS, De Michele F, Soczynska JK, Woldeyohannes HO, Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Carvalho AF, et al. The putative impact of metabolic health on default mode network activity and functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets (2014) 13:1750–8.

23. Guo W, Liu F, Xue Z, Gao K, Liu Z, Xiao C, et al. Decreased interhemispheric coordination in treatment-resistant depression: a resting-state fMRI study. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e71368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071368

24. Andreescu C, Tudorascu DL, Butters MA, Tamburo E, Patel M, Price J, et al. Resting state functional connectivity and treatment response in late-life depression. Psychiatry Res. (2013) 214:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.08.007

25. van Tol MJ, Li M, Metzger CD, Hailla N, Horn DI, Li W, et al. Local cortical thinning links to resting-state disconnectivity in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:2053–65. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002742

26. Abbott CC, Lemke NT, Gopal S, Thoma RJ, Bustillo J, Calhoun VD, et al. Electroconvulsive Therapy Response in Major Depressive Disorder: A Pilot Functional Network Connectivity Resting State fMRI Investigation. Frontiers in Psychiatry (2013) 4:10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00010

27. Wu QZ, Li DM, Kuang WH, Zhang TJ, Lui S, Huang XQ, et al. Abnormal regional spontaneous neural activity in treatment-refractory depression revealed by resting-state fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. (2011) 32:1290–9. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21108

28. Wise T, Marwood L, Perkins AM, Herane-Vives A, Joules R, Lythgoe DJ, et al. Instability of default mode network connectivity in major depression: a two-sample confirmation study. Transl Psychiatry (2017) 7:e1105. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.40

29. Qin J, Wei M, Liu H, Chen J, Yan R, Yao Z, et al. Altered anatomical patterns of depression in relation to antidepressant treatment: Evidence from a pattern recognition analysis on the topological organization of brain networks. J Affect Disord (2015) 180:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.059

30. Gudayolferré E, Perócebollero M, Guàrdiaolmos J. Changes in brain connectivity related to the treatment of depression measured through fMRI: a systematic review. Front Hum Neurosci. (2015) 9:582. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00582

31. Liston C, Chen AC, Zebley BD, Drysdale AT, Gordon R, Leuchter B, et al. Default mode network mechanisms of transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Biol Psychiatry (2014) 76:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.023

32. Mulders PC, van Eijndhoven PF, Pluijmen J, Schene AH, Tendolkar I, Beckmann CF. Default mode network coherence in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder during electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. (2016) 205:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.059

33. Uddin LQ, Kelly AM, Biswal BB, Margulies DS, Shehzad Z, Shaw D, et al. Network homogeneity reveals decreased integrity of default-mode network in ADHD. J Neurosci Methods (2008) 169:249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.11.031

34. Guo W, Liu F, Yao D, Jiang J, Su Q, Zhang Z, et al. Decreased default-mode network homogeneity in unaffected siblings of schizophrenia patients at rest. Psychiatry Res. (2014) 224:218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.08.014

35. Guo W, Liu F, Chen J, Wu R, Li L, Zhang Z, et al. Olanzapine modulates the default-mode network homogeneity in recurrent drug-free schizophrenia at rest. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2017) 51:1000–9. doi: 10.1177/0004867417714952

36. Guo W, Yao D, Jiang J, Su Q, Zhang Z, Zhang J, et al. Abnormal default-mode network homogeneity in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia at rest. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2014) 49:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.021

37. Wei S, Su Q, Jiang M, Liu F, Yao D, Dai Y, et al. Abnormal default-mode network homogeneity and its correlations with personality in drug-naive somatization disorder at rest. J Affect Disord. (2016) 193:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.052

38. Guo W, Liu F, Yu M, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Liu J, et al. Decreased regional activity and network homogeneity of the fronto-limbic network at rest in drug-naive major depressive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2015) 49:550–6. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577978

39. Zhang D, Wang Y, Lu P, Wang P, Yuan X, Yan J, et al. REST regulates the cell cycle for cardiac development and regeneration. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:1979. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02210-y

40. Cui X, Guo W, Wang Y, Yang TX, Yang XH, Wang Y, et al. Aberrant default mode network homogeneity in patients with first-episode treatment-naive melancholic depression. Int J Psychophysiol. (2017) 112:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.12.005

41. Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. J Cogn Neurosci. (2002) 14:340–7. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886

42. Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for “pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci (2010) 4:13. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00013

43. Nichols TE, Das S, Eickhoff SB, Evans AC, Glatard T, Hanke M, et al. Best practices in data analysis and sharing in neuroimaging using MRI. Nat Neurosci. (2017) 20:299–303. doi: 10.1038/nn.4500

44. Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Douaud G, Nichols TE, Smith SM. Faster permutation inference in brain imaging. Neuroimage (2016) 141:502–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.068

45. Saad ZS, Gotts SJ, Murphy K, Chen G, Jo HJ, Martin A, et al. Trouble at rest: how correlation patterns and group differences become distorted after global signal regression. Brain Connect. (2012) 2:25–32. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0080

46. Hahamy A, Calhoun V, Pearlson G, Harel M, Stern N, Attar F, et al. Save the global: global signal connectivity as a tool for studying clinical populations with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Connect (2014) 4:395–403. doi: 10.1089/brain.2014.0244

47. Maddock RJ, Garrett AS, Buonocore MH. Posterior cingulate cortex activation by emotional words: fMRI evidence from a valence decision task. Hum Brain Mapp. (2010) 18:30–41. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10075

48. Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Meuli R, Honey CJ, Wedeen VJ, et al. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. Plos Biol. (2012) 6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159

49. Marchetti I, Koster EH, Sonuga-Barke EJ, De Raedt R. The default mode network and recurrent depression: a neurobiological model of cognitive risk factors. Neuropsychol Rev. (2012) 22:229–51. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9199-9

50. Caetano SC, Kaur S, Brambilla P, Nicoletti M, Hatch JP, Sassi RB, et al. Smaller cingulate volumes in unipolar depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry (2006) 59:702–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.011

51. Peng J, Liu J, Nie B, Li Y, Shan B, Wang G, et al. Cerebral and cerebellar gray matter reduction in first-episode patients with major depressive disorder: A voxel-based morphometry study. Eur J Radiol. (2011) 80:395. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.04.006

52. Drevets WC, Bogers W, Raichle ME. Functional anatomical correlates of antidepressant drug treatment assessed using PET measures of regional glucose metabolism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2002) 12:527–44. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(02)00102-5

53. Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim SN. The Common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. MIT Press. (2009) 21, 489–510. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21029

54. Bonavita S, Sacco R, Esposito S, d'Ambrosio A, Della Corte M, Corbo D, et al. Default mode network changes in multiple sclerosis: a link between depression and cognitive impairment? Eur J Neurol. (2017) 24:27–36. doi: 10.1111/ene.13112

55. Maddock RJ, Garrett AS, Buonocore MH. Remembering familiar people: the posterior cingulate cortex and autobiographical memory retrieval. Neuroscience (2001) 104:667–76. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00108-7

56. Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain (2006) 129:564–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004

57. Gong X, Lu W, Kendrick KM, Pu W, Wang C, Jin L, et al. A Brain-wide association study of DISC1 genetic variants reveals a relationship with the structure and functional connectivity of the precuneus in schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. (2014) 35:5414–30. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22560

58. Jang JH, Jung WH, Choi JS, Choi CH, Kang DH, Shin NY, et al. Reduced prefrontal functional connectivity in the default mode network is related to greater psychopathology in subjects with high genetic loading for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2011) 127:58. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.022

59. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Association between functional connectivity hubs and brain networks. Cerebr Cortex (2011) 21:2003. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq268

60. Seghier ML. The angular gyrus: multiple functions and multiple subdivisions. Neuroscientist (2013) 19:43–61. doi: 10.1177/1073858412440596

61. Liu P, Yang W, Yuan X, Bi C, Chen A, Huang X. Individual alerting efficiency modulates time perception. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00386

62. Carhart-Harris RL, Erritzoe D, Williams T, Stone JM, Reed LJ, Colasanti A, et al. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:2138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119598109

63. Sämann PG, Wehrle R, Hoehn D, Spoormaker VI, Peters H, Tully C, et al. Development of the brain's default mode network from wakefulness to slow wave sleep. Cereb Cortex (2011) 21:2082–93. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq295

64. Boord P, Madhyastha TM, Askren MK, Grabowski TJ. Executive attention networks show altered relationship with default mode network in PD. Neuroimage Clin. (2017) 13:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.11.004

Keywords: depression, default mode network, network homogeneity, attentional network test, rest-fMRI

Citation: Gao Y, Wang M, Yu R, Li Y, Yang Y, Cui X and Zheng J (2018) Abnormal Default Mode Network Homogeneity in Treatment-Naive Patients With First-Episode Depression. Front. Psychiatry 9:697. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00697

Received: 05 June 2018; Accepted: 30 November 2018;

Published: 18 December 2018.

Edited by:

Catherine Harmer, Warneford Hospital, United KingdomReviewed by:

Andrea Aguglia, University of Genova, ItalyCopyright © 2018 Gao, Wang, Yu, Li, Yang, Cui and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinou Zheng, MTgyMTk2MzYzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.