- 1Department of Plant Protection, Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA), Madrid, Spain

- 2Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas (CIB)-Margarita Salas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid, Spain

Monilinia laxa is a necrotrophic plant pathogen able to infect and produce substantial losses on stone fruit. Three different isolates of M. laxa were characterized according to their aggressiveness on nectarines. M. laxa 8L isolate was the most aggressive on fruit, 33L isolate displayed intermediated virulence level, and 5L was classified as a weak aggressive isolate. Nectarine colonization process by the weak isolate 5L was strongly delayed. nLC-MS/MS proteomic studies using in vitro peach cultures provided data on exoproteomes of the three isolates at equivalent stages of brown rot colonization; 3 days for 8L and 33L, and 7 days for 5L. A total of 181 proteins were identified from 8L exoproteome and 289 proteins from 33L at 3 dpi, and 206 proteins were identified in 5L exoproteome at 7 dpi. Although an elevated number of proteins lacked a predicted function, the vast majority of proteins belong to OG group “metabolism”, composed of categories such as “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” in 5L, and “energy production and conversion” most represented in 8L and 33L. Among identified proteins, 157 that carried a signal peptide were further examined and classified. Carbohydrate-active enzymes and peptidases were the main groups revealing different protein alternatives with the same function among isolates. Our data suggested a subset of secreted proteins as possible markers of differential virulence in more aggressive isolates, MlPG1 MlPME3, NEP-like, or endoglucanase proteins. A core-exoproteome among isolates independently of their virulence but time-dependent was also described. This core included several well-known virulence factors involved in host-tissue factors like cutinase, pectin lyases, and acid proteases. The secretion patterns supported the assumption that M. laxa deploys an extensive repertoire of proteins to facilitate the host infection and colonization and provided information for further characterization of M. laxa pathogenesis.

Introduction

Brown rot is an economically important fungal disease on stone and pome fruit in Europe caused by Monilinia fructicola, Monilinia fructigena, and Monilinia laxa (Byrde and Willetts, 1977; Oliveira Lino et al., 2016). Monilinia spp. are necrotrophic fungi, which acquire nutrients and establish the disease from dead cells through toxic molecules and lytic enzymes (Garcia-Benitez et al., 2018). Cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDE) and toxins are virulence factors that necrotrophic fungi exploit to infect and colonize host plants (Ma et al., 2019). Accordingly, the polygalacturonase family (Chou et al., 2015) and MfCUT1 cutinase (Lee et al., 2010) have also captured significant attention due to their essential roles in the pathogenesis of M. fructicola. Polygalacturonase, pectin and pectate lyase, rhamnogalacturonan acetyl esterase, rhamnogalacturonan hydrolase, and α-L-rhamnosidase gene families related to pectin degradation have been identified from M. laxa (Baró-Montel et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Pires et al., 2020). The application of transcriptomics to Monilinia spp. (De Miccolis Angelini et al., 2018), and the genome availability of two strains of M. laxa, including 8L strain under study in this work (Naranjo-Ortíz et al., 2018; Landi et al., 2020) provides the information to decipher the key factors underlying Monilinia spp. pathogenicity mechanisms.

Pathogenic strategies have been more intensely studied in other fungal genera of Sclerotiniaceae family than in the case of Monilinia spp. (van Kan, 2006; Andrew et al., 2012). Some defined virulence factors are involved in different phases of Botrytis cinerea pathogenesis process, such as cutinases, polygalacturonases, cellulases, among other lytic and cell wall degrading activities. Cutinases are presumably necessary for penetration through the cuticle, namely cutB was only expressed in the presence of plant lipids (Leroch et al., 2013), but cutA was not essential for penetration in tomato (van Kan et al., 1997). Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes such as endo- and exo-polygalacturonases had a significant role in pectin breakdown, being BcPG1 the most host-widely expressed (Ten Have et al., 2001; Blanco-Ulate et al., 2014). On the other hand, the pectin methyl esterases seem to be a host-dependent virulence function (Valette-Collet et al., 2003; Kars et al., 2005). Regarding cellulose and hemicellulose lytic enzymes, several CAZymes families were expressed in different hosts in addition to pectinases (Blanco-Ulate et al., 2014), some of which may have more than just enzymatic activity. For example, beyond the putative xylanase activity of BcXyn11A, this protein contributed to B. cinerea pathogenesis with necrotizing activity and was required for full virulence (Brito et al., 2006; Noda et al., 2010). Toxins and phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins produced by B. cinerea during its host progress colonization were also included as virulence factors (Collado et al., 2000; Schouten et al., 2008; Dalmais et al., 2011). Several of the virulence factors mentioned above were also described to be produced by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, such as polygalacturonases (Li et al., 2004), cutinase (Zhang et al., 2014), and Nep proteins (Dallal Bashi et al., 2010). In the Sclerotiniaceae family, in addition to CWDEs, other lytic enzymes such as peptidases could play an essential role in nutrition and defense against antifungal compounds (Billon-Grand et al., 2002; Ten Have et al., 2010).

Since their emergence, proteomic techniques have been applied in plant pathology, although more slowly and not as extensively as in other research topics (Ashwin et al., 2017; Vincent et al., 2020). Proteomics was a powerful tool to evaluate samples containing a large number of proteins generated in diverse biological states (El-Akhal et al., 2013; Loginov and Šebela, 2016). The proteome has been used to determine proteins related to pathogenesis (El-Bebany et al., 2010; Ismail and Able, 2016) and in plant-based interactions (Shah et al., 2012). In this sense, a great effort has been made in the closely necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea to understand molecular mechanisms from a proteomic view, such as conidial germination (Espino et al., 2010; González-Rodríguez et al., 2014), modulation of protein secretion patterns under different carbon sources (Fernández-Acero et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2009b) and plant-based elicitors (Shah et al., 2009a; Fernández-Acero et al., 2010). Furthermore, how B. cinerea responded to non-nutritional changes such as pH (Li et al., 2012) and the involvement of membrane proteins in signal transduction cascades (Escobar-Niño et al., 2019). Besides, protein profiling focused on virulence-related functions between wild-type strains and B. cinerea mutants (Müller et al., 2018; de Vallée et al., 2019).

However, a few proteomic studies have been reported to date applied to Monilinia spp. Essentially, the group of Bregar et al. (2012) using LC-MS/MS determined host specificity proteins between M. laxa isolates obtained from apricots and apples. In this work, we proceeded to identify possible key proteins produced by the fungus in contact with lyophilized peaches. For this purpose, we used proteomic analyses from diverse M. laxa isolates, with confirmed different virulence levels on nectarines in order to identify potential virulence factors and to understand M. laxa brown rot development.

Materials and Methods

Fungal Isolates and Virulence Characterization

Three single-spore isolates of Monilinia laxa (namely 5L, 8L, and 33L) were used in this study. All of them were isolated from mummified plum fruit (cv. Sungold) from a commercial orchard in Lagunilla (Salamanca, Spain), and belong to the culture collection of the Plant Protection Department of INIA (Madrid, Spain). M. laxa 8L was also deposited in the Spanish Culture Type Collection (CECT 21100). The isolates were identified as M. laxa using their growth characteristics and PCR (Gell et al., 2007) and maintained as conidial suspensions in 20% glycerol at −80°C for long-term storage or as cultures on potato dextrose agar (Difco) at 4°C for short-term storage. For conidia production, M. laxa strains were grown on potato dextrose agar amended with 20% of tomato pulp at 22°C for 7 to 9 days with a 12-h photoperiod.

The virulence of M. laxa isolates was tested on nectarines (cv. Big Top) harvested at commercial maturity from Ebro Valley (Spain) previously described in Villarino et al. (2016) with some modifications. The nectarines were surface disinfected (Sauer and Burroughs, 1986) and dried in a laminar flow cabinet. Experiments were carried out with five fruit for each isolate and three unwounded points, with 15 μl droplet of 103 conidia ml−1 of aqueous conidial suspension. Fruit were incubated in a humidity chamber at 25°C for 12 days (16 h photoperiod). Each fruit was daily evaluated for symptoms of brown rot (incidence and incubation period), the onset of sporulation (latency period), and lesion diameter was measured at each inoculation point (Villarino et al., 2016). The complete experiment was repeated three times. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (Snedecor and Cochran, 1967). When the F test was significant at P ≤ 0.05, the means were compared by the Student–Newman–Keuls multiple range test.

Protein Isolation

Freshly harvested conidia from M. laxa isolates, produced as described above, were collected with sterile distilled water by filtration through Miracloth. Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 ml of 1% lyophilized peach in water were inoculated with the conidial suspension of each isolate to a final concentration of 105 conidia ml−1 and incubated in an orbital shaker at 120 rpm and 22°C. For preparing lyophilized peach, peaches were first lyophilized for 48 to 72 h using a Cryodos-50 lyophilizer (Telstar, Spain). The lyophilized peach was then made into a powder by bead beating using a tissue homogenizer (FastPrep®-24, MP Biomedicals) two times for 30 s at 4 m/s. Culture media (exoproteome) were harvested by filtration through two Whatman 1 filters (Cat No 1001 090) after 3 days post-inoculation (dpi) for aggressive isolates (8L and 33L) and 7 dpi for weak aggressive isolate (5L). Visual inspection using a microscope ensured the absence of conidia or hyphae as contaminants in culture media. Proteins present in 100 ml of culture media were precipitated by adding trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 10% (Hernández-Ortiz and Espeso, 2013). Samples were incubated on ice for 20 min, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to collect precipitated proteins. The pellets were washed firstly with 1 ml of ethanol-ethyl ether (1:1), centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and then secondly with 1 ml of ethanol-ethyl ether (1:3) followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Protein pellets from exoproteome were dried at room temperature and then dissolved in 50 μl Laemmli cracking buffer and maintained at −20°C until use for nLC-MS/MS.

nLC-MS/MS Proteomics

The procedures for nLC-MS/MS were previously described in Manoli and Espeso (2019). A 20-μl aliquot of extracellular protein precipitate was loaded onto a 10% polyacrylamide gel and allowed to run 1 cm into the resolving gel. The piece of the gel was excised and proteins were treated with trypsin (Cristobo et al., 2011). Digested samples were analyzed on a nano Easy nLC 1000 (Proxeon) coupled to an LTQ–Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were loaded onto Acclaim PepMap 100 (Thermo Scientific) trap column and eluted onto Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 3 μm (Thermo Scientific, 75 μm x 25 cm). A 110-min gradient was run at 250 nl/min flow rate using gradients from 0% to 35% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) 90 min, from 45% to 95% buffer B 10 min, 95% buffer B 9 min and 10% buffer B 1 min. Mass spectra analyses were conducted on an LTQ–Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific) in positive mode, full scan MS spectra (m/z 400–2000) at a resolution of 60,000. The top 15 most intense ions were selected and fragmented using collision-induced dissociation (CID) in the ion tramp with 35% normalized collision energy, and a dynamic exclusion time of 45 s was applied. Exoproteome of each isolate sample raw files were searched with Sequest through Proteome Discoverer version 1.4.1.14 against M. laxa 8L proteome (Naranjo-Ortíz et al., 2018) with peptide tolerance of 10 ppm and fragment tolerance of 0.5 Da. Cysteine carbamidomethylation and methionine oxidation were considered fixed modifications. False discovery rate calculations were generated using Percolator at q ≤ 0,01 (Käll et al., 2007).

Protein Annotation and Classification

Functional annotation of LC-MS/MS identified proteins from each isolate was carried out with Blast2GO v5.0 and BLASTp from NCBI1. BLASTp search was performed against the fungi non-redundant protein database of NCBI with a threshold e-value <10−5. All identified proteins from each sample were classified into main metabolic pathways using the OG classification against the EggNog database (Huerta-Cepas et al., 2018), and classification into gene ontology analysis of candidates was carried out using Blast2go v5.0. Furthermore, the subcellular location of identified proteins was firstly predicted based on SignalP 5.0 (Almagro Armenteros et al., 2019) and DeepLoc (Almagro Armenteros et al., 2017). Proteins with positive extracellular hits were secondly considered for targeting domains prediction TMHMM2 and GPI (Fankhauser and Mäser, 2005). Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZymes3) and peptidases were identified using dbCAN2 (Yin et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2018) and the MEROPS4 database respectively.

Results

Characterization of Several M. laxa Isolates Virulence on Nectarines

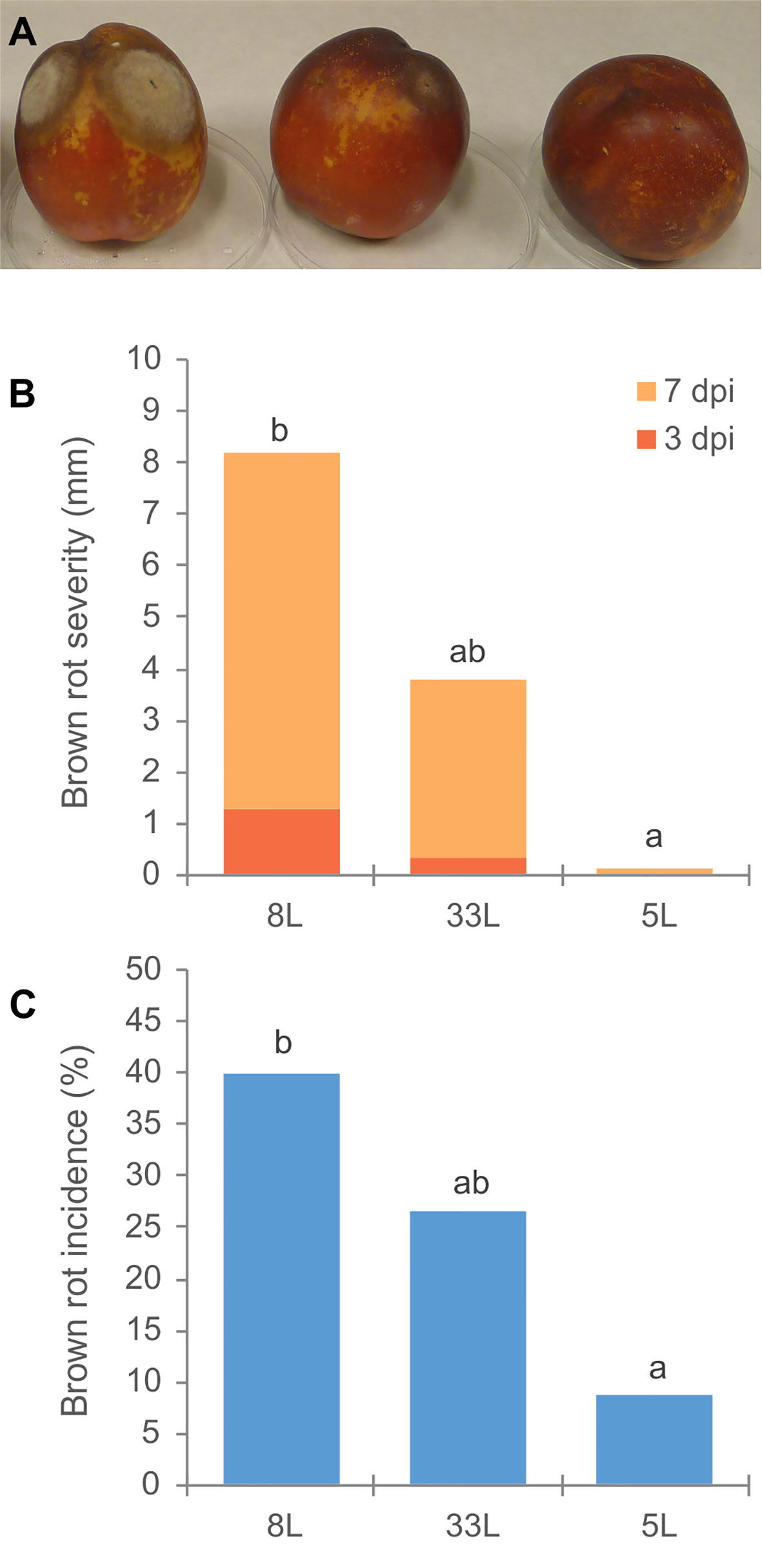

Virulence of M. laxa isolates 5L, 8L, and 33L (see Materials and Methods) were compared. Significantly virulence differences were observed among three M. laxa isolates. Brown rot severity caused by M. laxa 8L isolate at 3 and 7 days after inoculation on nectarine fruit, and its brown rot incidence at the end of assays were always higher than those recovered with 5L isolate (Figure 1). However, the virulence levels of 33L isolate were in an intermediate position between the most aggressive isolate (8L) and the weak aggressive isolate (5L). Brown rot severity caused by the weak pathogenic isolate (5L) at 7 days of incubation was similar to that caused by the most pathogenic isolate (8L) after only 3 days of incubation (Figure 1). The first sign of sporulation in nectarines inoculated by 8L and 33L was recorded after 6 days. However, no sporulation was observed on nectarines inoculated by 5L at the end of the assay.

Figure 1 (A) Disease assessment of unwounded nectarine fruit cv. `Big Top´; in order 8L, 33L and 5L M. laxa isolate. (B) Brown rot severity (mm) caused by M. laxa isolates at 3 and 7 days after inoculation on nectarine fruit cv. Big Top´. (C) Brown rot incidence (%) by M. laxa isolates 12 days after inoculation. Data represent the mean of three experiments with three inoculations per fruit, and five fruit per isolate and experiment. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance, means values with the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) according Student–Newman–Keuls multiple range test.

Characterization of Exoproteomes From Virulent and Weak Virulent Isolates

We used an nLC-MS/MS approach to analyze the extracellular proteins produced by M. laxa isolates with different virulence when growing in liquid media containing 1% freeze-dried peach. Due to the strong colonization differences between the weak isolate 5L and the more virulent isolates 8L and 33L we decided to investigate equivalent times of infection among isolates, 3 days for 8L and 33L and 7 days for 5L. Extracellular protein samples were taken after 3 days for strains 8L and 33L, and 7 days for strain 5L and a total of 181 proteins were identified from 8L exoproteome and 289 proteins from 33L at 3 dpi, and 206 proteins were identified in 5L exoproteome at 7 dpi. Details of the whole identified proteins and peptides are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

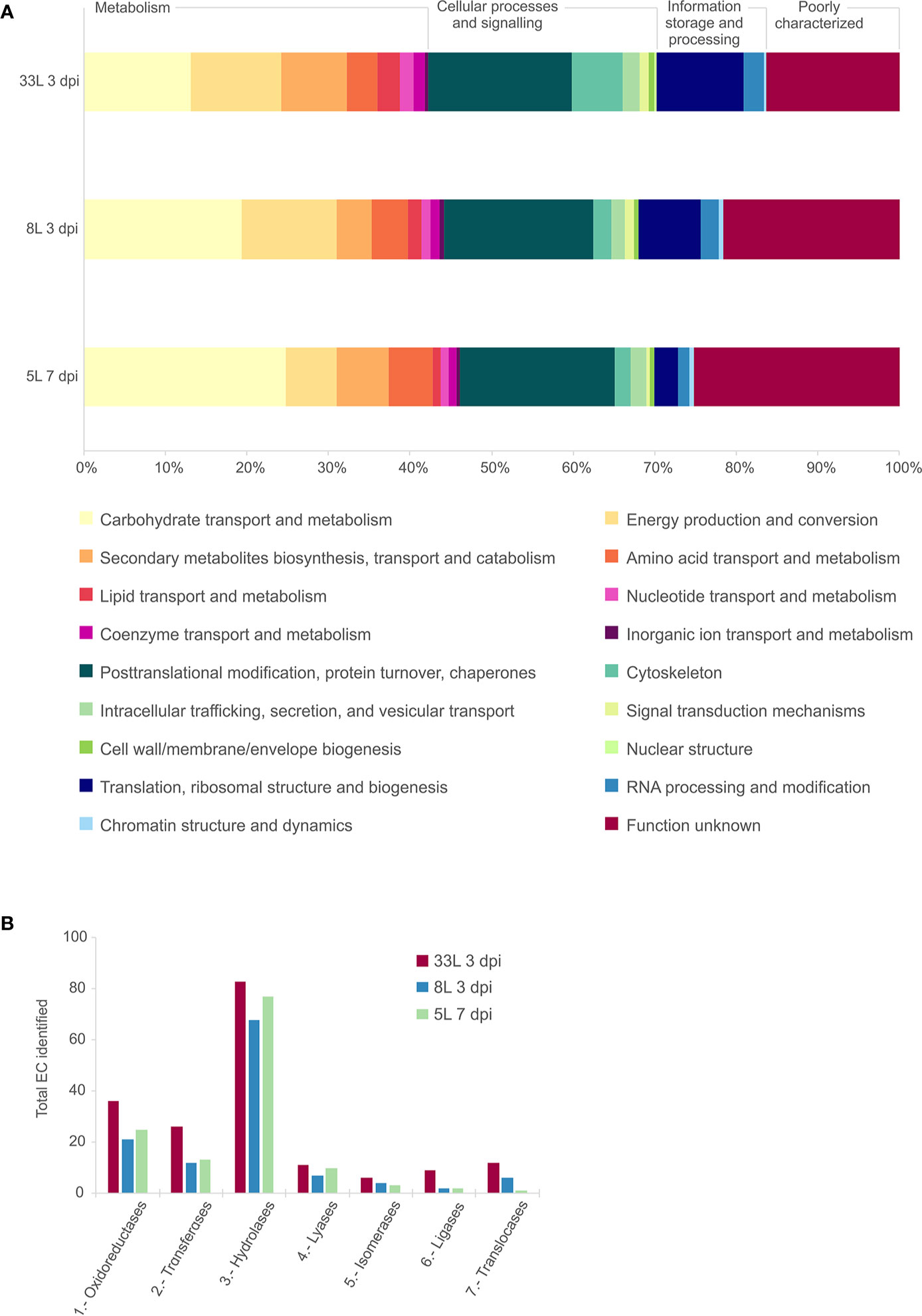

The detected proteins of each sample were categorized into main functional categories using the OG classification (clusters of Orthologous Group). The identified proteins were classified into 18 functional OG categories within 4 groups, among which the most represented group with similar proportion for all the isolates was the “metabolism” group (Figure 2A). Within the group of metabolism, we found differences in some functional categories, “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” was higher in 5L, and “energy production and conversion” most represented in 8L and 33L. Concerning “information storage and processing,” 8L and 33L at 3 dpi present a higher proportion than 5L at 7 dpi, due to differences in “translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis.” It is noteworthy the fraction of proteins classified as “function unknown” in all isolates (Figure 2A). Similarly, the three isolates had a relatively high number of enzymes that belong to hydrolase, followed by oxidoreductase and transferase protein families (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 Comparative analysis of the identified proteins in exoproteome of M. laxa isolates for 3 days post-inoculation (dpi) in 8L and 33L virulent isolates, and 7 dpi in 5L weak virulent. (A) Category abundance of identified proteins in exoproteome grouped into 18 functional categories using OG classification for 5L, 8L and 33L M. laxa isolates. (B) Enzyme distribution of identified proteins for M. laxa isolates represented as total number of proteins identified in each EC class.

Identification of Potential Secreted Enzymatic Activities Among Virulent Isolates at 3 dpi and Weak Isolate at 7 dpi

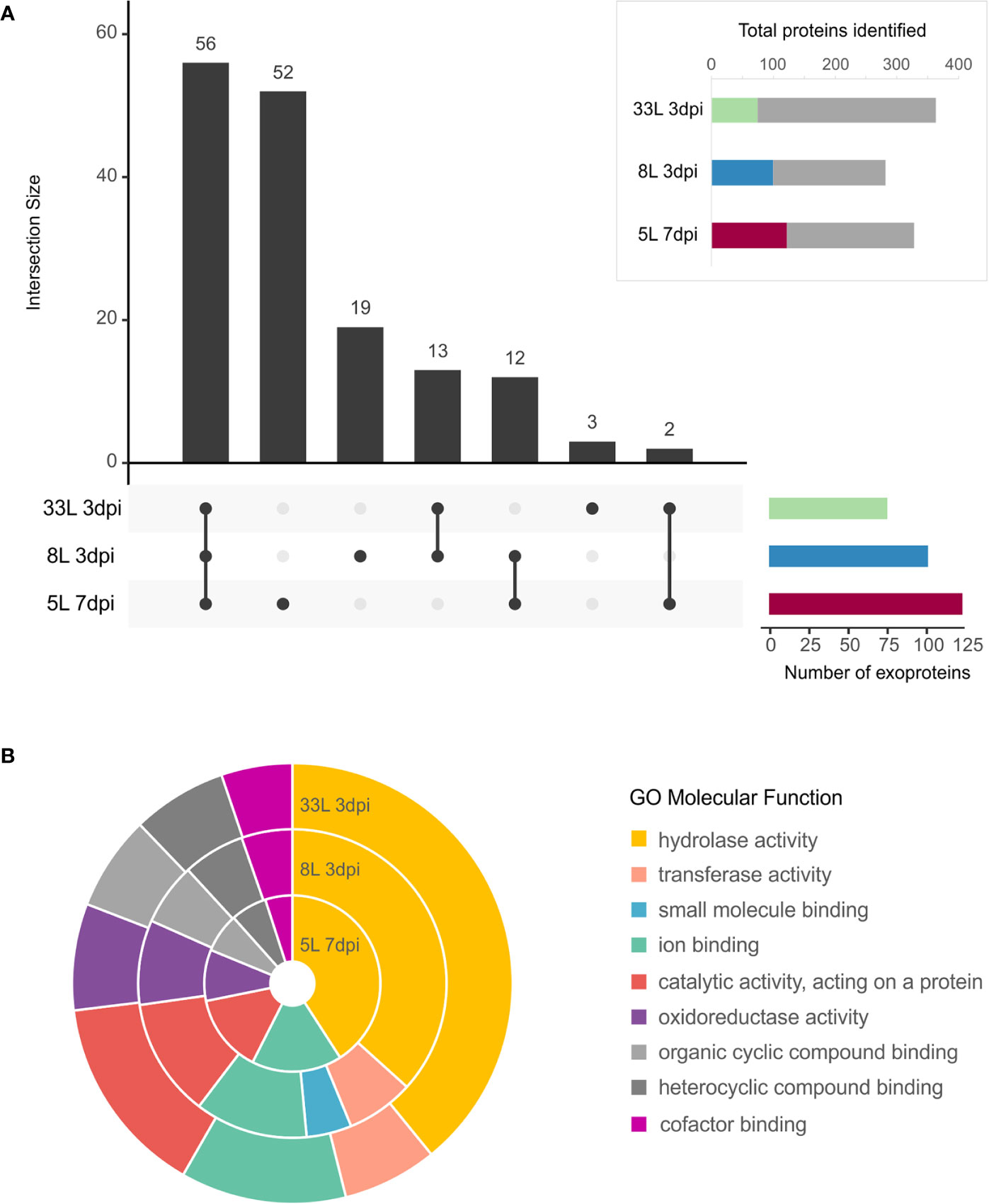

All the proteins identified in exoproteome, either 7 dpi or 3 dpi, were further analyzed using the SignalP tool for the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide (Figure 3A, box). Also, their possible cellular/extracellular locations were predicted by DeepLoc tool (Supplementary Table 2). Focusing our attention only on those proteins that carried a signal peptide (SP), 157 different proteins carrying an SP were found among the M. laxa isolates. In total, 74 SP-proteins were identified in 33L and 100 SP-proteins for 8L both after 3 days, while 122 SP-proteins were found in 5L at 7 dpi (Figure 3A box). All the possible combinations of the SP positive proteins found in the selected exoproteomes were drawn by an UpSet plot (Figure 3A). Fifty-six proteins were present across the three isolates, besides 14 proteins shared between at least one of virulent isolates with the weak virulent isolate (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 3). Apart from that, 35 SP-proteins were explicitly identified in 8L or 33L and both (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 4). It is worth noting the detection of 52 SP-proteins only present in 5L at 7 dpi (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 5). Classification of identified SP-proteins, based on GO analysis for molecular function, revealed a similar proportion in almost all categories (Figure 3B). The largest proportion of SP-proteins was involved in hydrolase activity and catalytic activity acting on a protein. Compared with 5L, 8L and 33L presented transferase activity, and only in 8L the small-molecule-binding GO function was present (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Exoproteome of M. laxa isolates. (A, box) Proportion of identified M. laxa proteins with potential signal peptides detected in exoproteome for an early and late time point (3 and 7 dpi, respectively) in 8L and 33L virulent isolates, and late time point (7 dpi) in 5L weak virulent isolate. (A) UpSet plot of intersecting sets of SignalP positive proteins found in exoproteomes. Total identifications for each sample (left bar chart), were 74 proteins for 33L and 100 proteins for 8L at 3 dpi, and 122 for 5L at 7 dpi. The connected dots among protein sets shown in the lower panel and numbers indicated in the top bar chart represent the group of proteins shared between exoproteome samples. (B) Classification of SignalP positive proteins based on GO molecular function. Shown is the percentage (%) of proteins in exoproteome samples attributed to each GO group at level 3.

Cazymes

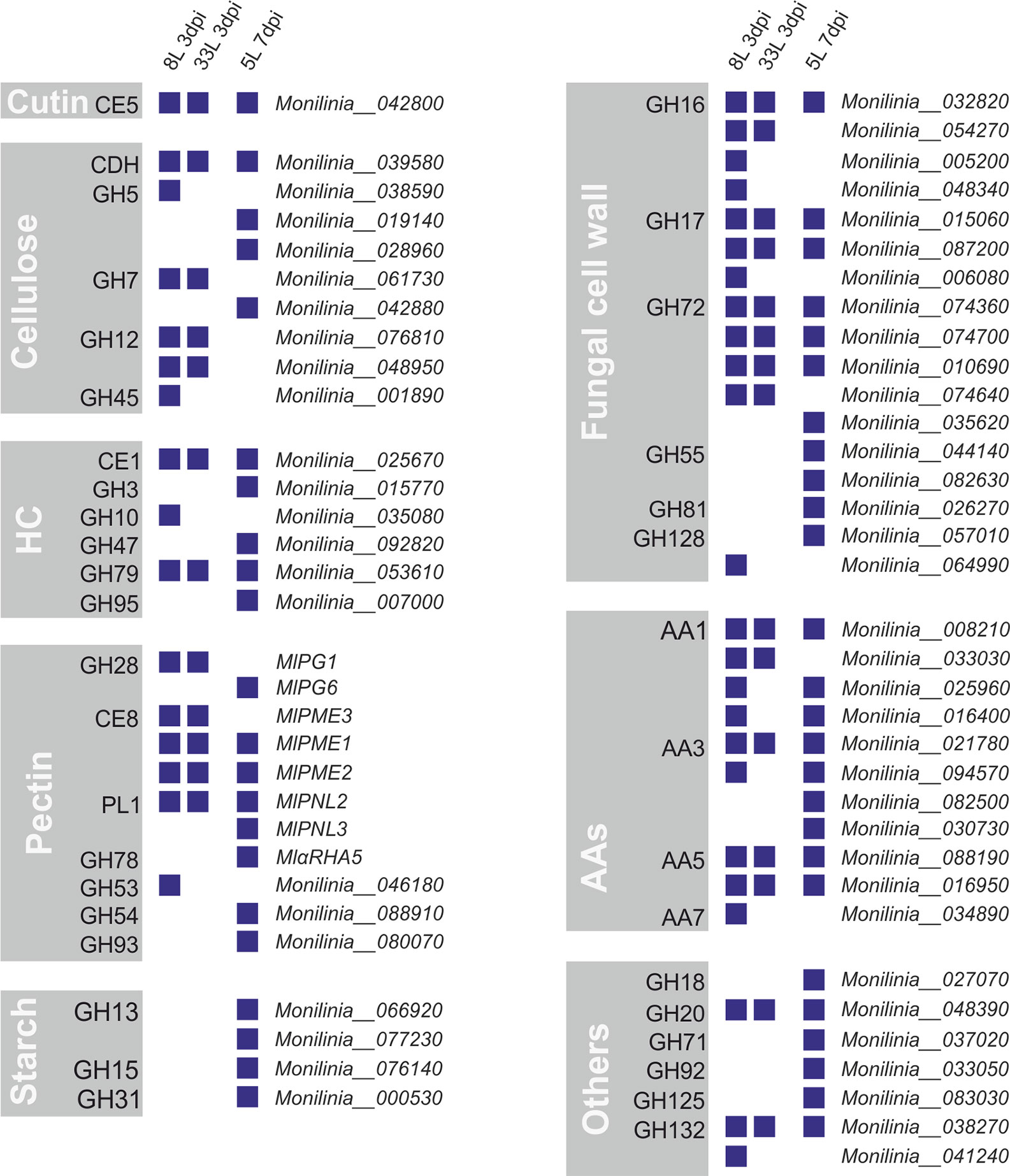

Out of the 157 proteins that carry an N-terminal possibly secretory signal peptide, 66 proteins were identified as carbohydrate-active enzymes or CAZymes by at least two prediction tools through the dbCAN meta server (Supplementary Tables 3–5). Among the identified CAZymes, by far the most abundant class was glycoside hydrolases (GHs), followed by auxiliary activities (AAs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs), and polysaccharide lyases (PL). Many of these classes include well-known protein families that were related to plant cell-wall disassembly, such as cellulases, hemicellulases, and pectinases. Thus, the identified CAZymes in M. laxa exoproteomes were classified regarding their possible plant cell targets and those involved in remodeling fungal cell wall (Figure 4).

Figure 4 CAZymes identified from exoproteomes of virulent M. laxa isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and weak virulent 5L at 7 dpi. Each group depicts a plant cell wall target, including auxiliary activities (AAs), CAZymes related to the fungal cell wall and a miscellaneous group indicated as others. Positive identification of a protein in each isolate proteome is presented as a blue square. On the right is indicated the corresponding protein unique identification number.

Among eight groups of CAZymes, many differences were observed between proteins present in virulent isolates at 3 dpi and weak virulent isolate at 7 dpi (Figure 4). The highest differences observed between virulent and weak virulent isolates was cellulose group (89% of different proteins), followed by pectin group (73% of different proteins), hemicellulose (67% of different proteins), fungal cell wall group (65% of different proteins), and another group (71% of different proteins). Specially, four related with cellulose degradation (GH5, GH7, GH12, and GH45), the MlPG1 (GH28), MlPME3 (CE8), and GH53 associated with pectin disassembly, as well as one laccase (AA7), GH10, and four involved in fungal cell wall remodeling (some of GH16, GH17, GH72, and GH128) were only recovered from the most virulent isolates (Figure 4). Only one cutinase (MlCUT1) was recovered from exoproteome of three isolates. Moreover, AAs group showed a 64% similarity between virulent and weak virulent isolates. Concerning cellulose degradation, ten proteins belonging to six CAZyme families were found associated with cellulose, with only cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH) being detected in all isolates. Regarding the hemicellulose plant target, 6 proteins belonging each one to a different family were identified, a member of CE1 and another of GH79 group were present in the three exoproteomes. Notably, three members of the GH72 family were found in common in the three M. laxa isolates together with two of GH17 and one in GH16 families (Figure 4).

On the other hand, only the weak isolate showed the presence of an activity related to starch metabolism (Figure 4), and recovered MlPG6 (GH28), MlPNL3 (PL1), MlαRHA5, GH54, and GH93 associated with pectin disassembly, as well as one laccase (AA3), GH3, GH47, GH95, and four involved in fungal cell wall remodeling (GH55, GH81, and some of GH72, and GH128).

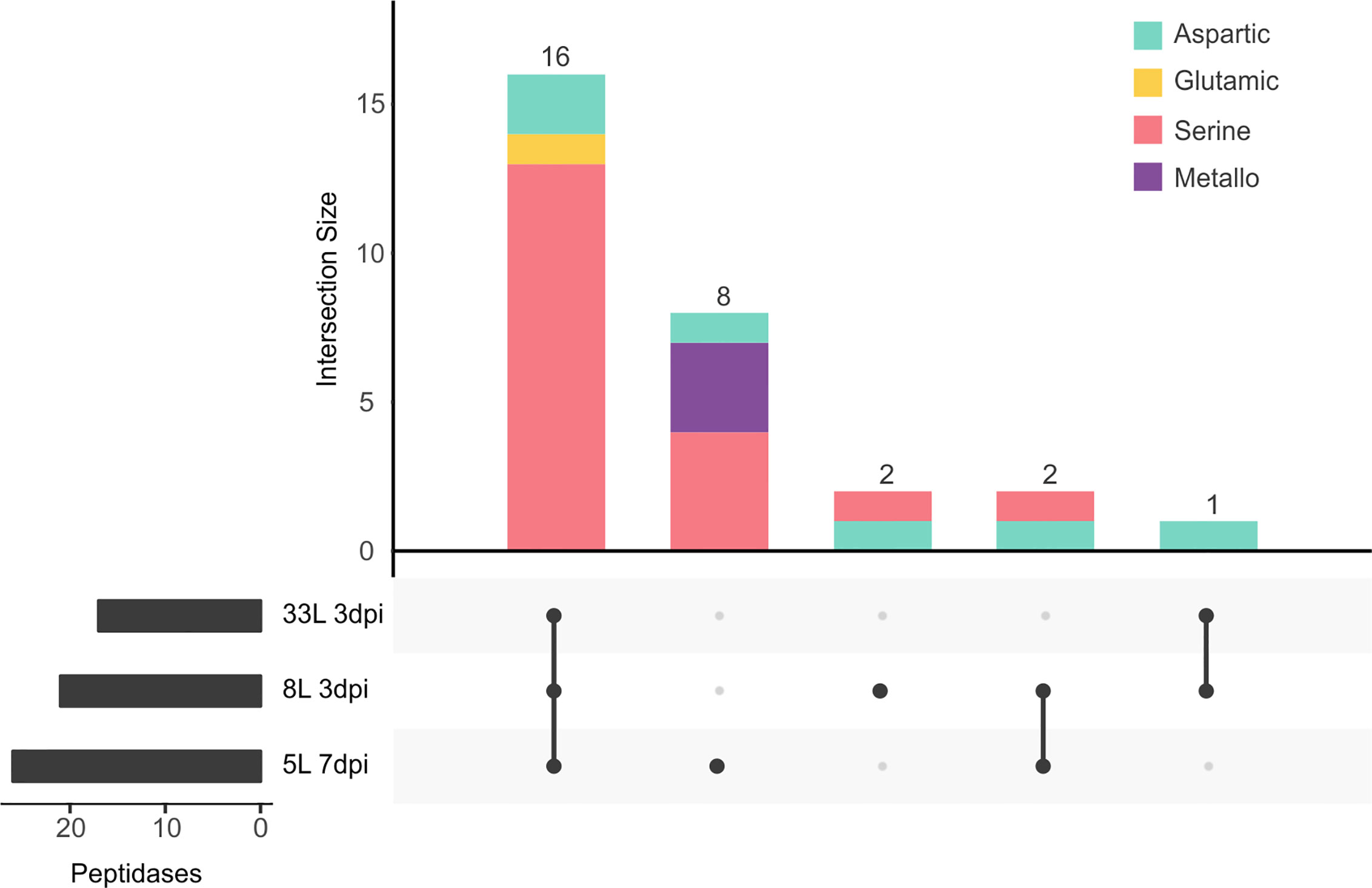

Peptidases

The second most represented class in the exoproteome was that of peptidases, with 18.5% (29 proteases) among the three isolates (Figure 5). Of proteases, the largest group identified was the serine-peptidases that contain tripeptidyl peptidases and carboxypeptidases, which were detected in the cultures of 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, as well as in 5L at 7 dpi (Supplementary Tables 3–5). Also, one G1 glutamic (formerly A4) and six aspartic peptidases were detected in the tree exoproteomes. However, metallopeptidases were only found in 5L at 7 dpi (Figure 5), among which two zinc carboxypeptidases were identified. In contrast to the significant number of specific proteases found in 5L (8), only two were found in 8L and none in 33L.

Figure 5 UpSet plot of intersecting sets of peptidase proteins found in exoproteomes. Total identifications for each sample (left bar chart), were 17 proteins for 33L and 21 proteins for 8L at 3 dpi, and 26 for 5L at 7 dpi. The connected dots among protein sets shown in the lower panel and numbers indicated in the top bar chart represent the group of proteins shared between exoproteome samples. The intersecting set (top bar chart) also classified the different peptidases according to the chemical mechanism as aspartic (green), glutamic (yellow), serine (pink), and metallo (purple) catalytic type.

Discussion

M. laxa isolates 5L, 8L, and 33L were classified by their virulence factors and characterized their protein patterns, comparing their protein profiles showed a core proteome and differences that could be associated with their respective virulence levels. The fact that exoproteomes from 8L and 33L at 3 dpi and 5L at 7 dpi showed a similar pattern was in agreement with the reduced growth rate of the weak virulence isolate (5L). Differences among protein profiles had already been associated with the pathogenicity of necrotrophic fungi in different special forms of Fusarium oxysporum (Fang and Barbetti, 2014; Li et al., 2015; Manikandan et al., 2018), Verticillium dahlie (El-Bebany et al., 2010), and B. cinerea (Fernández-Acero et al., 2007). We hypothesize that brown rot infection and colonization process by weak isolate 5L might be delayed.

Exoproteomes from 8L and 33L at 3 dpi showed high content in lytic enzymes, as described for 5L at 7 dpi. These proteins harbor a signal peptide suggesting they were actively secreted. Secreted protein enrichment had been reported when studying exoproteomes in other fungal phytopathogens (Yajima and Kav, 2006; Cobos et al., 2010; González-Fernández et al., 2014). The analysis of the 157 SP positive proteins revealed a core exoproteome of 56 proteins shared among M. laxa isolates, which could imply a common strategy among them. Similar strategies have been described studying secretomes in B. cinerea (González-Fernández et al., 2014) and Pyrenophora teres f. teres (Ismail and Able, 2016). An increase of secreted proteins has been reported in B. cinerea when growing in nutritionally rich media compared to more simple media (Shah et al., 2009a; Espino et al., 2010) or with complex carbon sources like pectin as has been described in M. laxa (Shah et al., 2009b; Rodríguez-Pires et al., 2020). The higher percentage of secreted proteins, as well as their possible target function in proteins and structural carbohydrates, supports a specialization of M. laxa exoproteome towards peach degradation. The production of extracellular enzymes by necrotrophic fungi has an essential role in plant infection in part due to the efficient degradation of plant tissues as a source of carbon and nitrogen (Kim et al., 2007; Blanco-Ulate et al., 2014). Accordingly, multiple proteins with a putative role in carbohydrate or protein degradation had been identified in exoproteomes of 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and the weak aggressive 5L at 7 dpi.

Similarly, MlCUT1 (Monilinia_042800) was detected at 3 dpi in 8L and 33L, and also identified in 5L at 7 dpi. The cuticle is the first area of interaction between Monilinia and its host. Cutinase (MfCUT1) of M. fructicola was an infection marker with early expression since 5 h post-inoculation on petals (Lee et al., 2010) and an essential virulence factor in the absence of wounds (Lee and Bostock, 2006; Lee et al., 2010). Previous data and this work show that the M. laxa orthologous protein MlCUT1 (Monilinia_042800) was also early expressed during mycelial growth (6 hpi, in vitro cultures (Rodríguez-Pires et al., 2020)). Notably, MlCUT1 was detected at 7 dpi on the weak virulent strain 5L, supporting the conclusion that the delay in the development of virulence symptoms by 5L isolate must be caused by an inadequate pattern of exoproteins at 7 dpi.

The comparative biological status of 3 dpi in virulent isolates and 7 dpi in weak virulent revealed a core-proteome with several CAZys and peptidases. Some enzymes related to hemicellulose breakdown were also found in all isolates such as acetyl xylan esterase (CE1) and β-glucuronidase (GH79) (Glass et al., 2013). Few differences were recorded among the content of AAs class from the three M. laxa isolates. AAs class included redox enzymes that act in conjunction with CAZymes as ligninolytic or lytic polysaccharide oxygenases (CAZy database3). The most abundant, AA1 family was functionally annotated as laccases, that could oxidize a wide range of phenols and non-aromatic compounds and are involved in melanin synthesis, delignification, detoxify host antifungal compounds, and fungal virulence (Quidde et al., 1998; Mayer and Staples, 2002; Schouten et al., 2002; Coman et al., 2013). De Miccolis Angelini et al. (2018) described a laccase2 (Monilinia_025960 ortholog) one of the most differently expressed genes in M. laxa, although their possible plant-pathogen role had not been studied in Monilinia spp. its possible biotechnological applications had been considered (Bao et al., 2012; Demkiv et al., 2020). Proteins involved in the modification of fungal cell walls played an essential role in growth, survival, and also plant-fungi interaction in phytopathogens (Free, 2013; Geoghegan et al., 2017; Patel and Free, 2019). As reported to S. sclerotiorum proteome (Liu and Free, 2016), we found in the exoproteomes of the three M. laxa isolates members of GH16, GH17, and GH72 families. These families have been proved to be essential for cell wall cross-linking in model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Neurospora crassa (Patel and Free, 2019). Highlight the possible role in the pathogenesis of β‐1,3‐glucanosyltransferases or Gels/Gas (GH17) described in Magnaporthe oryzae during appressorium‐mediated plant infection (Samalova et al., 2016) or the role of gas1 in Fusarium oxysporum on tomato infection (Caracuel et al., 2005).

The presence of proteases in the three M. laxa exoproteomes was also noteworthy being the second most abundant group with 29 proteins. A high percentage of peptidases were shared among the three isolates. Peptidases could play a nutritional function, as reported in the closely M. fructigena that produced an unidentified acid protease activity (Hislop et al., 1982). Although, they could be involved in pathogenesis as well as a defense against antifungal compounds produced by the hosts, such as secreted serine protease in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Jashni et al., 2015). The most represented protease family was serine peptidase in M. laxa isolates, similar to proteomic early secretome in B. cinerea (Espino et al., 2010). The glutamic family represented with one protein (Monilinia_077490) and shared by the three isolates was orthologous to an acid protease previously studied Ssacp1 in S. sclerotiorum (Poussereau et al., 2001) and Bcacp1 in B. cinerea (Rolland et al., 2009). Both secreted proteases, Ssacp1 and Bcacp1, were only expressed under acidic conditions during infection despite the different possible strategies in sunflower colonization (Poussereau et al., 2001; Billon-Grand et al., 2002; Rolland et al., 2009).

Differences were found in the content of proteomes of the three M. laxa isolates, especially among CAZymes, the most extensive protein group identified in M. laxa exoproteomes (42%). Among lytic enzymes required for degradation of the major components of the plant cell wall (i.e., cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin), several activities have been only detected from proteomes of the most virulent isolates. In this way, four alternative proteins of β-1,4-endoglucanases (GH5, GH12, GH45), and cellobiohydrolases (GH7) related with cellulose degradation, MlPG1, MlPME3, and endo-β-1,4-galactanase (GH53) associated with pectin disassembly, as well as one laccase, an endo-1,4-beta-xylanase (GH10), and four involved in fungal cell wall remodeling. Although previous studies on M. laxa have not reported cellulase activity (Garcia-Benitez et al., 2018) or differential expression of their genes (De Miccolis Angelini et al., 2018), it was expected that the presence of these proteins were involved in their degradation. Xylanases, in addition to its activity described in Monilinia spp (Garcia-Benitez et al., 2018), were also present in the B. cinerea proteome (Shah et al., 2009a; Espino et al., 2010; Fernández-Acero et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2012), which may have a role beyond its degrading function as a necrosis inducer like Xyn11A of B. cinerea (Noda et al., 2010). In agreement with the high pectin content in peach fruit, 11 pectinase degrading enzymes were identified. Interestingly, the virulent factor MlPG1 was detected in the virulent ones but not in the weak virulent 5L, but this isolate produced MlPG6 which has no defined function in pathogenesis. Although in M. fructicola an over-expression of MfPG1 has been associated with smaller lesions (Chou et al., 2015), upregulation of M. laxa MlPG1 and protein identification had been reported with pectin as carbon source (Rodríguez-Pires et al., 2020). Likewise, PG1 was the most widely identified polygalacturonase in B. cinerea (Shah et al., 2009a; Shah et al., 2009b; Espino et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2012; González-Fernández et al., 2014). Among pectin lyases (PNLs), MlPNL1 was not detected, MlPNL3 was only identified in 5L, while the occurrence of MlPNL2 was in all of them. Pectin methyl esterases played a role in de-esterification in pectin breakdown, and particular MlPME2 had been described as a possible virulence factor in fruit (Baró-Montel et al., 2019), and highly expressed concerning other Monilinia spp (De Miccolis Angelini et al., 2018). The presence of some PME seems to be constitutive when M. laxa grew in pectin or glucose culture (Rodríguez-Pires et al., 2020), but here MlPME3 was absent in the weak virulent 5L.

In this context, another possible virulence factor NEP-like protein was only identified in the exoproteomes of most virulent isolates. The putative necrosis and ethylene inducing peptide (Monilinia_016550) were found in the 8L and 33L at 3 dpi. Necrosis and ethylene-inducing peptides of B. cinerea and S. sclerotiorum promote plant cell death during the early stages of lesion expansion being indispensable SsNep2 in S. sclerotiorum (Dallal Bashi et al., 2010). However, they did not seem to be essential individually in B. cinerea (Cuesta Arenas et al., 2010).

In this study, we have characterized three M. laxa isolates depending on their virulence degree. Isolate 5L is less aggressive than the other two, 8L and 33L. Exoproteomes of these three M. laxa isolates with different degrees of virulence have been evaluated, and their analyses provided new insights into how exoproteome could contribute to the necrotrophic infection. Firstly, our data shows the existence of a core exoproteome of 56 common proteins. Many of these identified proteins are hydrolytic enzymes highlighting the role of a common framework towards peach degradation among isolates with different virulence such as cutinase, laccases, and acid peptidase were identified as some examples, which could constitute a broad disease control target. In addition, a subset of secreted proteins were specifically identified in exoproteomes of virulent isolates, MlPG1 MlPME3, NEP-like or endoglucanase proteins, which we consider as possible markers of differential virulence in more aggressive isolates. We suspect that 5L isolate is delayed in its pathogenicity program. Further studies to analyze and compare 5L strain with other highly virulent isolates may assist in deciphering the genetic basis for regulating this time-related process of M. laxa pathogenicity on stone fruit.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD019758.

Author Contributions

AC and EE proposed this research line. AC, PM and EE searched for funding. AC and EE conceived and supervised the experiments, which were carried out by SR-P. AC, EE and SR-P wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by grants AGL2014-55287-C2-1-R, BFU2015-66806-R, RTI2018-094263-B-I00 and AGL2017-84389-C2-2-R from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU, Spain), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, EU). SR-P received a Ph.D. fellowship from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Spain).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Castillo for her technical support, and to V. de los Rios from the CIB’s Proteomics and Genomics facility for her assistance in improving peptide determinations and database searches.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.01286/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Details of the whole identified proteins and peptides through LC-MS/MS in exoproteome of virulent Monilinia laxa isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and weak virulent isolate 5L at 7 dpi.

Supplementary Table 2 | Total proteins identified in exoproteome of virulent Monilinia laxa isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and weak virulent 5L at 7 dpi.

Supplementary Table 3 | Common accumulated proteins identified in exoproteome of virulent Monilinia laxa isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and weak virulent isolate 5L at 7 dpi.

Supplementary Table 4 | Common accumulated proteins identified in exoproteome of virulent Monilinia laxa isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi, and absent in weak virulent isolate 5L at 7 dpi.

Supplementary Table 5 | Accumulated proteins identified in exoproteome of weak virulent Monilinia laxa isolate 5L at 7 dpi, and absent in virulent isolates 8L and 33L at 3 dpi.

Footnotes

- ^ https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

- ^ https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?TMHMM-2.0

- ^ http://www.cazy.org

- ^ https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/

References

Almagro Armenteros, J. J., Kaae Sønderby, C., Kaae Sønderby, S., Nielsen, H., Winther, O. (2017). DeepLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics 33, 3387–3395. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx431

Almagro Armenteros, J. J., Tsirigos, K. D., Sønderby, C. K., Petersen, T. N., Winther, O., Brunak, S., et al. (2019). SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z

Andrew, M., Barua, R., Short, S. M., Kohn, L. M. (2012). Evidence for a common toolbox based on necrotrophy in a fungal lineage spanning necrotrophs, biotrophs, endophytes, host generalists and specialists. PloS One 7, e29943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029943

Ashwin, N. M. R., Barnabas, L., Ramesh Sundar, A., Malathi, P., Viswanathan, R., Masi, A., et al. (2017). Advances in proteomic technologies and their scope of application in understanding plant-pathogen interactions. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 26, 371–386. doi: 10.1007/s13562-017-0402-1

Bao, W., Peng, R., Zhang, Z., Tian, Y., Zhao, W., Xue, Y., et al. (2012). Expression, characterization and 2,4,6-trichlorophenol degradation of laccase from Monilinia fructigena. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 3871–3877. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1166-7

Baró-Montel, N., Vall-llaura, N., Usall, J., Teixidó, N., Naranjo-Ortíz, M. A., Gabaldón, T., et al. (2019). Pectin methyl esterases and rhamnogalacturonan hydrolases: weapons for successful Monilinia laxa infection in stone fruit? Plant Pathol. 68, 1381–1393. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13039

Billon-Grand, G., Poussereau, N., Fèvre, M. (2002). The extracellular proteases secreted in vitro and in planta by the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Phytopathol. 150, 507–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0434.2002.00782.x

Blanco-Ulate, B., Morales-Cruz, A., Amrine, K. C. H., Labavitch, J. M., Powell, A. L. T., Cantu, D. (2014). Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of Botrytis cinerea genes targeting plant cell walls during infections of different hosts. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 435. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00435

Bregar, O., Mandelc, S., Celar, F., Javornik, B. (2012). Proteome analysis of the plant pathogenic fungus Monilinia laxa showing host specificity. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 50, 326–333.

Brito, N., Espino, J. J., González, C. (2006). The endo- β -1 , 4-xylanase Xyn11A is required for virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 19, 25–32. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0025

Byrde, R. J. W., Willetts, H. J. (1977). The brown rot fungi of fruit: their biology and control (London: Pergamon Press).

Caracuel, Z., Martínez-rocha, A. L., Pietro, A., Madrid, M. P., Roncero, M., II (2005). Fusarium oxysporum gas1 encodes a putative β -1, 3-glucanosyltransferase required for virulence on tomato plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18, 1140–1147. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1140

Chou, C. M., Yu, F., Yu, P. L., Ho, J. F., Bostock, R. M., Chung, K. R., et al. (2015). Expression of five endopolygalacturonase genes and demonstration that MfPG1 overexpression diminishes virulence in the brown rot pathogen Monilinia fructicola. PloS One 10, e0132012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132012

Cobos, R., Barreiro, C., Mateos, R. M., Coque, J.-J. R. (2010). Cytoplasmic- and extracellular-proteome analysis of Diplodia seriata: a phytopathogenic fungus involved in grapevine decline. Proteome Sci. 8, 46. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-46

Collado, I., Aleu, J., Hernandez-Galan, R., Duran-Patron, R. (2000). Botrytis species: an intriguing source of metabolites with a wide range of biological activities. Structure, chemistry and bioactivity of metabolites isolated from Botrytis species. Curr. Org. Chem. 4, 1261–1286. doi: 10.2174/1385272003375815

Coman, C., Moţ, A. C., Gal, E., Pârvu, M., Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R. (2013). Laccase is upregulated via stress pathways in the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Fungal Biol. 117, 528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.05.005

Cristobo, I., Larriba, M. J., de los Ríos, V., García, F., Muñoz, A., Casal, J., II (2011). Proteomic analysis of 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 action on human colon cancer cells reveals a link to splicing regulation. J. Proteomics 75, 384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.08.003

Cuesta Arenas, Y., Kalkman, E. R., II, Schouten, A., Dieho, M., Vredenbregt, P., Uwumukiza, B., et al. (2010). Functional analysis and mode of action of phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins of Botrytis cinerea. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 74, 376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2010.06.003

Dallal Bashi, Z., Hegedus, D. D., Buchwaldt, L., Rimmer, S. R., Borhan, M. H. (2010). Expression and regulation of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum necrosis and ethylene-inducing peptides (NEPs). Mol. Plant Pathol. 11, 43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00571.x

Dalmais, B., Schumacher, J., Moraga, J., Le Pêcheur, P., Tudzynski, B., Collado, I. G., et al. (2011). The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 564–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x

De Miccolis Angelini, R. M., Abate, D., Rotolo, C., Gerin, D., Pollastro, S., Faretra, F. (2018). De novo assembly and comparative transcriptome analysis of Monilinia fructicola, Monilinia laxa and Monilinia fructigena, the causal agents of brown rot on stone fruits. BMC Genomics 19, 436. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4817-4

de Vallée, A., Bally, P., Bruel, C., Chandat, L., Choquer, M., Dieryckx, C., et al. (2019). A similar secretome disturbance as a hallmark of non-pathogenic Botrytis cinerea ATMT-mutants? Front. Microbiol. 10, 2829. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02829

Demkiv, O. M., Gayda, G. Z., Broda, D., Gonchar, M. V. (2020). Extracellular laccase from Monilinia fructicola: isolation, primary characterization and application. Cell Biol. Int. 00, 1–13. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11316

El-Akhal, M. R., Colby, T., Cantoral, J. M., Harzen, A., Schmidt, J., Fernández-Acero, F. J. (2013). Proteomic analysis of conidia germination in Colletotrichum acutatum. Arch. Microbiol. 195, 227–246. doi: 10.1007/s00203-013-0871-0

El-Bebany, A. F., Rampitsch, C., Daayf, F. (2010). Proteomic analysis of the phytopathogenic soilborne fungus Verticillium dahliae reveals differential protein expression in isolates that differ in aggressiveness. Proteomics 10, 289–303. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900426

Escobar-Niño, A., Liñeiro, E., Amil, F., Carrasco, R., Chiva, C., Fuentes, C., et al. (2019). Proteomic study of the membrane components of signalling cascades of Botrytis cinerea controlled by phosphorylation. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46270-0

Espino, J. J., Gutierrez-Sanchez, G., Brito, N., Shah, P., Orlando, R., Gonzalez, C. (2010). The Botrytis cinerea early secretome. Proteomics 10, 3020–3034. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000037

Fang, X., Barbetti, M. J. (2014). Differential protein accumulations in isolates of the strawberry wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. fragariae differing in virulence. J. Proteomics 108, 223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.05.023

Fankhauser, N., Mäser, P. (2005). Identification of GPI anchor attachment signals by a Kohonen self-organizing map. Bioinform. Orig. Pap. 21, 1846–1852. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti299

Fernández-Acero, F. J., Jorge, I., Calvo, E., Vallejo, I., Carbú, M., Camafeita, E., et al. (2007). Proteomic analysis of phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea as a potential tool for identifying pathogenicity factors, therapeutic targets and for basic research. Arch. Microbiol. 187, 207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0188-3

Fernández-Acero, F. J., Colby, T., Harzen, A., Cantoral, J. M., Schmidt, J. (2009). Proteomic analysis of the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea during cellulose degradation. Proteomics 9, 2892–2902. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800540

Fernández-Acero, F. J., Colby, T., Harzen, A., Carbú, M., Wieneke, U., Cantoral, J. M., et al. (2010). 2-DE proteomic approach to the Botrytis cinerea secretome induced with different carbon sources and plant-based elicitors. Proteomics 10, 2270–2280. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900408

Free, S. J. (2013). Fungal cell wall organization and biosynthesis. Adv. Genet. 81, 33–82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407677-8.00002-6

Garcia-Benitez, C., Melgarejo, P., Sandin-España, P., Sevilla-Morán, B., De Cal, A. (2018). Degrading enzymes and phytotoxins in Monilinia spp. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 154, 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-01657-z

Gell, I., Cubero, J., Melgarejo, P. (2007). Two different PCR approaches for universal diagnosis of brown rot and identification of Monilinia spp. in stone fruit trees. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 2629–2637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03495.x

Geoghegan, I., Steinberg, G., Gurr, S. (2017). The role of the fungal cell wall in the infection of plants. Trends Microbiol. xx, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.015

Glass, N. L., Schmoll, M., Cate, J. H. D., Coradetti, S. (2013). Plant cell wall deconstruction by Ascomycete fungi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67, 477–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150044

González-Fernández, R., Aloria, K., Valero-Galván, J., Redondo, I., Arizmendi, J. M., Jorrín-Novo, J. V. (2014). Proteomic analysis of mycelium and secretome of different Botrytis cinerea wild-type strains. J. Proteomics 97, 195–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.06.022

González-Rodríguez, V. E., Liñeiro, E., Colby, T., Harzen, A., Garrido, C., Cantoral, J. M., et al. (2014). Proteomic profiling of Botrytis cinerea conidial germination. Arch. Microbiol. 197, 117–133. doi: 10.1007/s00203-014-1029-4

Hernández-Ortiz, P., Espeso, E. A. (2013). Phospho-regulation and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of CrzA in response to calcium and alkaline-pH stress in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 532–551. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12294

Hislop, E. C., Paver, J. L., Keon, J. P. R. (1982). An acid protease produced by Monilinia fructigena in vitro and in infected apple fruits, and its possible role in pathogenesis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128, 799–807. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-4-799

Huerta-Cepas, J., Szklarczyk, D., Heller, D., Hernández-Plaza, A., Forslund, S. K., Cook, H., et al. (2018). eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 309–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1085

Ismail, I. A., Able, A. J. (2016). Secretome analysis of virulent Pyrenophora teres f. teres isolates. Proteomics 16, 2625–2636. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500498

Jashni, M. K., Dols, I. H. M., Iida, Y., Boeren, S., Beenen, H. G., Mehrabi, R. (2015). Synergistic action of a metalloprotease and a serine protease from Fusarium oxysporum cleaves chitin-binding tomato chitinases. Mol. Plant Microbes Interact. 28, 996–1008. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-15-0074-R

Käll, L., Canterbury, J. D., Weston, J., Noble, W. S., MacCoss, M. J. (2007). Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat. Methods 4, 923–925. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1113

Kars, I., McCalman, M., Wagemakers, L., Van Kan, J. A. L. (2005). Functional analysis of Botrytis cinerea pectin methylesterase genes by PCR-based targeted mutagenesis: Bcpme1 and Bcpme2 are dispensable for virulence of strain B05.10. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6, 641–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00312.x

Kim, Y., Nandakumar, M. P., Marten, M. R. (2007). Proteomics of filamentous fungi. Trends Biotechnol. 25, 395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.008

Landi, L., Pollastro, S., Rotolo, C., Romanazzi, G., Faretra, F., de Miccolis Angelini, R. M. (2020). Draft genomic resources for the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia laxa. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 33, 145–148. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-19-0225-A

Lee, M. H., Bostock, R. M. (2006). Induction, regulation, and role in pathogenesis of appressoria in Monilinia fructicola. Phytopathology 96, 1072–1080. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-1072

Lee, M. H., Chiu, C. M., Roubtsova, T., Chou, C. M., Bostock, R. M. (2010). Overexpression of a redox-regulated cutinase gene, MfCUT1, increases virulence of the brown rot pathogen Monilinia fructicola on Prunus spp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 176–186. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-2-0176

Leroch, M., Kleber, A., Silva, E., Coenen, T., Koppenhöfer, D., Shmaryahu, A., et al. (2013). Transcriptome profiling of Botrytis cinerea conidial germination reveals upregulation of infection-related genes during the prepenetration stage. Eukaryot. Cell 12, 614–626. doi: 10.1128/EC.00295-12

Li, R., Rimmer, R., Buchwaldt, L., Sharpe, A. G., Séguin-Swartz, G., Hegedus, D. D. (2004). Interaction of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum with Brassica napus: Cloning and characterization of endo- and exo-polygalacturonases expressed during saprophytic and parasitic modes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 754–765. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.03.002

Li, B., Wang, W., Zong, Y., Qin, G., Tian, S. (2012). Exploring Pathogenic Mechanisms of Botrytis cinerea Secretome under Different Ambient pH Based on Comparative Proteomic Analysis. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4249–4260. doi: 10.1021/pr300365f

Li, E., Ling, J., Wang, G., Xiao, J., Yang, Y., Mao, Z., et al. (2015). Comparative proteomics analyses of two races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. conglutinans that differ in pathogenicity. Sci. Rep. 5, 13663. doi: 10.1038/srep13663

Liu, L., Free, S. J. (2016). Characterization of the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum cell wall proteome. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 985–995. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12352

Loginov, D., Šebela, M. (2016). Proteomics of survival structures of fungal pathogens. N. Biotechnol. 33, 655–665. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2015.12.011

Ma, H., Zhang, B., Gai, Y., Sun, X., Chung, K. R., Li, H. (2019). Cell-wall-degrading enzymes required for virulence in the host selective toxin-producing necrotroph Alternaria alternata of citrus. Front. Microbiol. 10:2514. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02514

Manikandan, R., Harish, S., Karthikeyan, G., Raguchander, T. (2018). Comparative proteomic analysis of different isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici to exploit the differentially expressed proteins responsible for virulence on tomato plants. Front. Microbiol. 9, 420. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00420

Manoli, M., Espeso, E. A. (2019). Modulation of calcineurin activity in Aspergillus nidulans: the roles of high magnesium concentrations and of transcriptional factor CrzA. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 1283–1301. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14221

Mayer, A. M., Staples, R. C. (2002). Laccase: new functions for an old enzyme. Phytochemistry 60, 551–565. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00171-1

Müller, N., Leroch, M., Schumacher, J., Zimmer, D., Könnel, A., Klug, K., et al. (2018). Investigations on VELVET regulatory mutants confirm the role of host tissue acidification and secretion of proteins in the pathogenesis of Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 219, 1062–1074. doi: 10.1111/nph.15221

Naranjo-Ortíz, M. A., Rodríguez-Pires, S., Torres, R., De Cal, A., Usall, J., Gabaldón, T. (2018). Genome sequence of the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia laxa. Genome Announc. 6, 1–2. doi: 10.1128/genomea.00214-18

Noda, J., Brito, N., González, C. (2010). The Botrytis cinerea xylanase Xyn11A contributes to virulence with its necrotizing activity, not with its catalytic activity. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-38

Oliveira Lino, L., Pacheco, I., Mercier, V., Faoro, F., Bassi, D., Bornard, I., et al. (2016). Brown rot strikes Prunus fruit: an ancient fight almost always lost. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 4029–4047. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00104

Patel, P. K., Free, S. J. (2019). The genetics and biochemistry of cell wall structure and synthesis in Neurospora crassa, a model filamentous fungus. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2294. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02294

Poussereau, N., Gente, S., Rascle, C., Billon-Grand, G., Fèvre, M. (2001). aspS encoding an unusual aspartyl protease from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is expressed during phytopathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 194, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00500-0

Quidde, T., Osbourn, A. E., Tudzynski, P. (1998). Detoxification of α-tomatine by Botrytis cinerea. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 52, 151–165. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.1998.0142

Rodríguez-Pires, S., Melgarejo, P., De Cal, A., Espeso, E. A. (2020). Pectin as carbon source for Monilinia laxa, exoproteome and expression profiles of related genes. Mol. Plant Microbes Interact. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-20-0019-R

Rolland, S., Bruel, C., Rascle, C., Girard, V., Billon-Grand, G., Poussereau, N. (2009). pH controls both transcription and posttranslational processing of the protease BcACP1 in the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Microbiology 155, 2097–2105. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.025999-0

Samalova, M., Mélida, H., Vilaplana, F., Bulone, V., Soanes, D. M., Talbot, N. J., et al. (2016). The β-1,3-glucanosyltransferases (Gels) affect the structure of the rice blast fungal cell wall during appressorium-mediated plant infection. Cell. Microbiol. 19, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12659

Sauer, D. B., Burroughs, R. (1986). Disinfection of seed surfaces with sodium hypochlorite. Phytopathology 76, 745–749. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-745

Schouten, A., Wagemakers, L., Stefanato, F. L., van der Kaaij, R. M., Kan, J. A. L. (2002). Resveratrol acts as a natural profungicide and induces self-intoxication by a specific laccase. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 883–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02801.x

Schouten, A., Van Baarlen, P., Van Kan, J. A. L. (2008). Phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins from the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea associate with membranes and the nucleus of plant cells. New Phytol. 177, 493–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02274.x

Shah, P., Atwood III, J., Orlando, R., El Mubarek, H., Podila, G. K., Davis, M. R. (2009a). Comparative proteomic analysis of Botrytis cinerea secretome. J. Proteome Res. 8, 1123–1130. doi: 10.1021/pr8003002

Shah, P., Gutierrez-Sanchez, G., Orlando, R., Bergmann, C. (2009b). A proteomic study of pectin-degrading enzymes secreted by Botrytis cinerea grown in liquid culture. Proteomics 9, 3126–3135. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800933

Shah, P., Powell, A. L. T., Orlando, R., Bergmann, C., Gutierrez-Sanchez, G. (2012). A proteomic analysis of ripening tomato fruit infected by Botrytis cinerea. J. Proteome Res. 11, 2178–2192. doi: 10.1021/pr200965c

Ten Have, A., Breuil, W. O., Wubben, J. P., Visser, J., Van Kan, J. A. L. (2001). Botrytis cinerea endopolygalacturonase genes are differentially expressed in various plant tissues. Fungal Genet. Biol. 33, 97–105. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2001.1269

Ten Have, A., Espino, J. J., Dekkers, E., Van Sluyter, S. C., Brito, N., Kay, J., et al. (2010). The Botrytis cinerea aspartic proteinase family. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.10.008

Valette-Collet, O., Cimerman, A., Reignault, P., Levis, C., Boccara, M. (2003). Disruption of Botrytis cinerea pectin methylesterase gene Bcpme1 reduces virulence on several host plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 16, 360–367. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.4.360

van Kan, J. A. L., van’t Klooster, J. W., Wagemakers, C. A. M., Dees, D. C. T., van Der Vlugt-Bergmans, C. J. B. (1997). Cutinase A of Botrytis cinerea is expressed, but not essential, during penetration of gerbera and tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10, 30–38. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.1.30

van Kan, J. A. L. (2006). Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005

Villarino, M., Melgarejo, P., De Cal, A. (2016). Growth and aggressiveness factors affecting Monilinia spp. survival peaches. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 227, 6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.01.023

Vincent, D., Rafiqi, M., Job, D. (2020). The multiple facets of plant–fungal interactions revealed through plant and fungal secretomics. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1626. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01626

Yajima, W., Kav, N. N. V. (2006). The proteome of the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Proteomics 6, 5995–6007. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600424

Yin, Y., Mao, X., Yang, J., Chen, X., Mao, F., Xu, Y. (2012). dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W445–W451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks479

Zhang, H., Wu, Q., Cao, S., Zhao, T., Chen, L., Zhuang, P., et al. (2014). A novel protein elicitor (SsCut) from Sclerotinia sclerotiorum induces multiple defense responses in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 86, 495–511. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0244-3

Keywords: brown rot, necrotrophic fungi, pathogenesis, carbohydrate degrading enzymes, peptidases, Monilinia laxa, exoproteome

Citation: Rodríguez-Pires S, Melgarejo P, De Cal A and Espeso EA (2020) Proteomic Studies to Understand the Mechanisms of Peach Tissue Degradation by Monilinia laxa. Front. Plant Sci. 11:1286. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01286

Received: 03 June 2020; Accepted: 06 August 2020;

Published: 20 August 2020.

Edited by:

Paulo José Pereira Lima Teixeira, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Elena Baraldi, University of Bologna, ItalyJose Valero Galvan, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, Mexico

Copyright © 2020 Rodríguez-Pires, Melgarejo, De Cal and Espeso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonieta De Cal, Y2FsQGluaWEuZXM=

Silvia Rodríguez-Pires

Silvia Rodríguez-Pires Paloma Melgarejo

Paloma Melgarejo Antonieta De Cal

Antonieta De Cal Eduardo A. Espeso

Eduardo A. Espeso