- 1National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology, College of Plant Science and Technology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Horticultural Plant Biology (Ministry of Education), College of Horticulture and Forestry Sciences, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China

Drought is a major threat to plant growth and crop productivity. Reduced level of the gibberellin would result in increased drought tolerance, but the underlying mechanism is still unclear. In Brassica napus, there are four BnaRGA genes that code for DELLA proteins, negative regulators of GA signaling. Among them, expression of BnaA6.RGA was greatly induced by drought and abscisic acid (ABA). Previously, we created the gain-of-function mutant of BnaA6.RGA, bnaa6.rga-D, and the loss-of-function quadruple mutant, bnarga by CRISPR/Cas9, respectively. Here we show that bnaa6.rga-D displayed enhanced drought tolerance, and its stomatal closure was hypersensitive to ABA treatment. By contrast, bnarga displayed reduced drought tolerance and was less sensitive to ABA treatment, but there is no difference in drought tolerance between single BnaRGA mutant and WT, suggesting a functional redundancy between the BnaRGA genes in this process. Furthermore, we found that BnaRGAs were able to interact physically with BnaA10.ABF2, an essential transcription factor in ABA signaling. The BnaA10.ABF2-BnaA6.RGA protein complex greatly increased the expression level of the drought responsive gene BnaC9.RAB18. Taken together, this work highlighted the fundamental roles of DELLA proteins in drought tolerance in B. napus, and provide desirable germplasm for further breeding of drought tolerance in rapeseed.

Introduction

Drought is a major stress that causes decreases in crop yield. Genetic engineering by regulating drought responsive genes are the effective approach for enhancing crop drought tolerance, which increases agricultural productivity to meet the food demand of expanding population (Zhu, 2016). Rapeseed (Brassica napus L., AACC, 2n = 38) is cultivated worldwide to produce edible oil, animal feed and biodiesel, making it an agriculturally important crop. B. napus is very sensitive to water deficits from germination to seed set (Zhu et al., 2016). Thus, there is a tremendous need and interest in understanding the physiology and molecular mechanism underlying of rapeseed to cope with drought stress.

The plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays essential roles during drought responses (Zhu, 2002; Chaves et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2020), and its level increases under water-deficit conditions. The identification of ABA receptors PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1)/PYR1-LIKE (PYL)/REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTORS (RCAR) revealed the core of the ABA-signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). In the absence of ABA, subclass III SNF1-related protein kinases (SnRK2.2/2.3/2.6) are dephosphorylated through interactions with a group A protein phosphatase type 2C (PP2C) to remain inactive (Soon et al., 2012). In the presence of ABA, the PYL receptors bind with ABA and form a PYL-ABA-PP2C complex, which inhibits the phosphatase activities of PP2C (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). As a consequence, SnRK2s are released from the SnRK2-PP2C complex and become activated through autophosphorylation. These activated SnRK2s can then phosphorylate downstream transcription factors to increase drought tolerance (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). Among these transcription factors, the bZIP group of ABA response element (ABRE)-binding factors (ABFs) play important roles in ABA signaling transduction (Zhu, 2002). In Arabidopsis, there are four ABFs, ABF1-4, and their expression levels are greatly induced by drought and ABA in vegetative tissues (Fujita et al., 2005). These ABFs bind to the ABRE cis-elements in the promoters of downstream genes, such as RAB18, RD29A, and RD29B (Fujita et al., 2005). The overexpression of ABF2 significantly increases drought tolerance in rice and tomato (Hossain et al., 2010; Hirano et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2016), and the constitutive expression of peanut ABF2 in Arabidopsis can also enhance drought tolerance (Li et al., 2013), suggesting that ABF2 is a master regulator of the ABA-dependent pathway.

The growth-promoting hormone gibberellin (GA) may also be involved in drought tolerance (Magome et al., 2008; Colebrook et al., 2014; Nir et al., 2014, 2017; Vishal and Kumar, 2018). GA levels are significantly reduced under drought conditions (Nelissen et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, the GA deficient mutants ga20ox1/2 and ga3ox1/2 are more resistant to drought (Colebrook et al., 2014). Tomato plants overexpressing GA METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (GAMT), which encodes a GA methyltransferase, also have enhanced tolerance levels to water-deficit stress (Nir et al., 2014). DELLA proteins are the key repressors of GA signaling (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis, the DELLA protein family includes five members, REPRESSOR OF ga1-3 (RGA), GIBBERELLIC ACID INSENSITIVE and RGA-LIKE 1-3 (Hirsch and Oldroyd, 2009). Recently, a mutant of tomato PROCERA, which encodes a DELLA protein, displayed a rapid water loss under water-deficit conditions, while its activity increased after the removal of 17 amino acids inside the DELLA motif, reducing the water loss. In Arabidopsis, gain-of-function mutant gai-1 also increases drought tolerance (Wang et al., 2020). This indicated that DELLA proteins play positive roles in drought tolerance (Nir et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020).

DELLA proteins belong to the GRAS transcription factor family, which lack a DNA-binding domain (Yoshida et al., 2014). Thus, DELLA proteins usually form complexes with DELLA-interacting proteins (DIPs) to regulate gene expression at the transcriptional level (Van De Velde et al., 2017). A majority of the DIPs are transcription factors or transcriptional regulators. DELLA proteins can form complexes with DIPs, such as PIFs and BZR1, to prevent them from binding to the promoters of downstream genes (de Lucas et al., 2008; Bai et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014), or JAZ and MYC2, to prevent them from interacting with other proteins (Hou et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2013). In the crosstalk with ABA signaling, DELLA proteins interact with other transcription factors, such as ABI3 and ABI5, to promote the expression levels of ABA-responsive genes that inhibit seed germination (Lim et al., 2013). Thus, DELLA proteins play roles in GA-regulated biological processes or the crosstalk of GAs with other pathways through the activation or sequestration of different DIPs.

Brassica napus is a relatively recent allopolyploid originating from the hybridization of Brassica rapa (2n = 20, AA) with Brassica oleracea (2n = 18, CC) (Chalhoub et al., 2014). When B. napus is exposed to drought at the vegetative stage, both osmotic adaptive proteins, such as macromolecules, including late embryogenesis-abundant proteins, and small metabolites, including proline and trehalose, are greatly induced (Good and Zaplachinski, 1994; Dalal et al., 2009; Müller et al., 2012). Additionally, ABA rapidly accumulates in the leaves (Qaderi et al., 2006), which triggers stomatal closure (Zhu et al., 2010). Sequence analyses identified all the ABA biosynthesis and signaling components in B. napus, indicating that this pathway is conserved in this species (Zhu et al., 2016). Moreover, ABA pathway genes, as well as some other stress-responsive genes, are also up-regulated by drought stress in B. napus (Li et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2010). The overexpression of the B. napus ABF2 gene BnaA10.ABF2 in Arabidopsis dramatically enhances drought tolerance (Zhao et al., 2016). However, the molecular basis of drought tolerance in B. napus is still largely unknown.

Because B. napus is an allotetraploid species (Chalhoub et al., 2014), it possesses 10 DELLA genes, including four homologs of RGA, BnaA6.RGA, BnaC7.RGA, BnaA9.RGA, and BnaC9.RGA. Previously, mutants of these BnaRGAs were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Yang et al., 2017). Here, we demonstrated that BnaA6.RGA acts as a positive regulator of drought tolerance by promoting stomatal closure through increased ABA sensitivity and subsequently by reducing water loss in response to a water deficit. Moreover, BnaA6.RGA regulated the expression of drought-responsive genes by directly interacting with BnaA10.ABF2, the ortholog of Arabidopsis ABF2. Our findings provide novel insights into the crosstalk between GA and ABA signaling pathways, and provide a useful germplasm for improving rapeseed drought tolerance.

Results

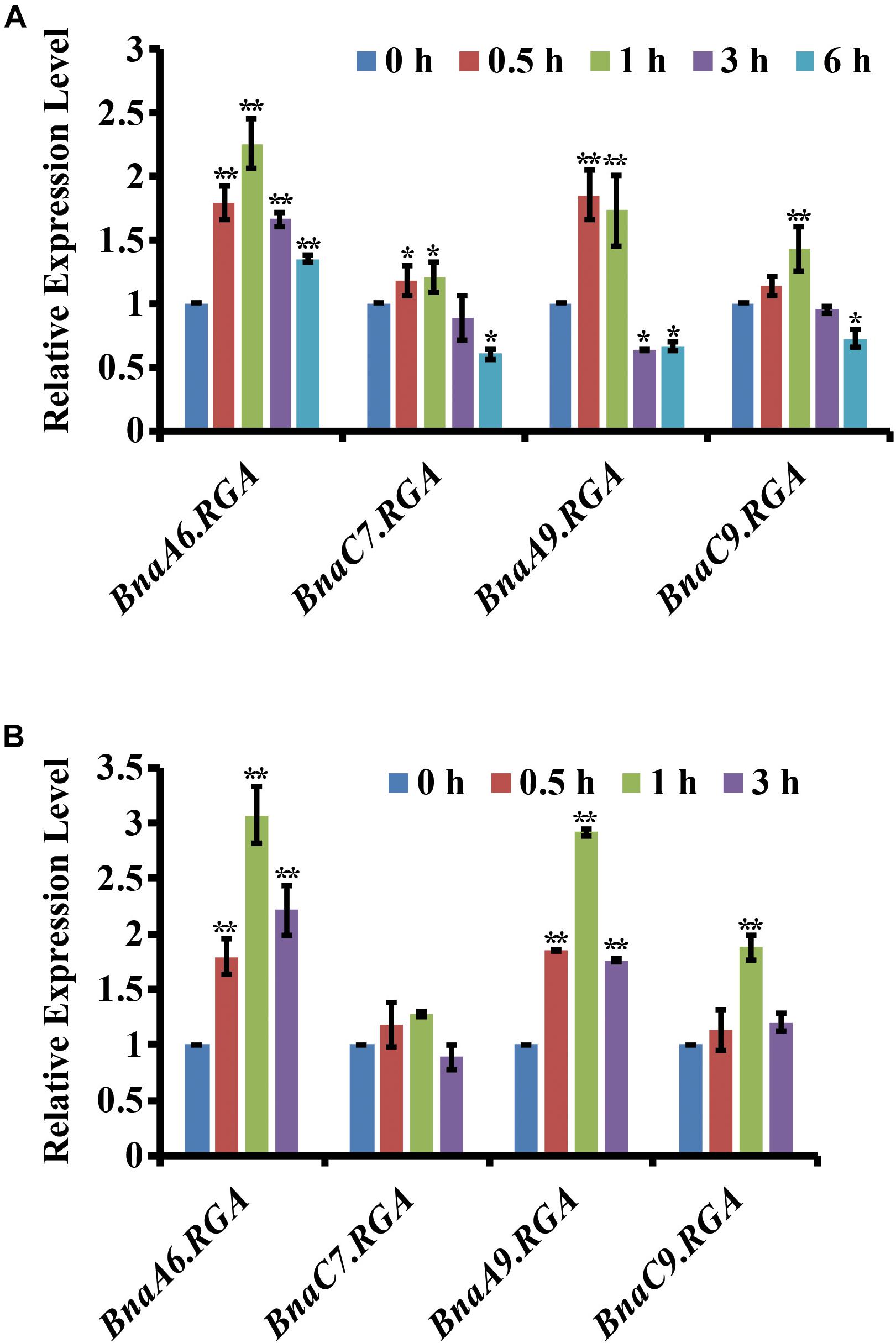

BnaA6.RGA Was Greatly Induced by Drought and Abscisic Acid

Drought tolerance is promoted by reducing the endogenous GA level in plants (Colebrook et al., 2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that the negative regulators of GA signaling, the DELLA proteins, may also play important roles in the drought tolerance of B. napus. In B. napus, there are four BnaRGAs (B. napus REPRESSOR OF ga1-3) homologs of Arabidopsis RGA gene (Zhao et al., 2017). To identify RGA genes that are responsive to drought and ABA, we examined their expression patterns under drought or ABA conditions using quantitative RT-PCR. After the drought treatment, the expression of BnaA6.RGA was greatly induced at 1 h, being three times higher than in the untreated tissue, and then its level slightly decreased at 3 h (Figure 1A). Compared with BnaA6.RGA, the expression levels of the BnaA9.RGA and BnaC9.RGA genes were also induced by drought, but the BnaC7.RGA was not significant changed (Figure 1A). Similarly, the expression of BnaA6.RGA was also greatly induced by an exogenous application of ABA, reaching its highest level at 1 h (Figure 1B), which was almost same drought treatment. In addition, the expressions of other BnaRGAs were up-regulated by the ABA treatment, although to a lesser extent than that of BnaA6.RGA (Figure 1B). Thus, the expression of BnaA6.RGA is more sensitive than those of other DELLA genes in response to drought and ABA treatments, which suggests that BnaA6.RGA plays more important roles in the drought tolerance of B. napus.

Figure 1. Expression of the four BnaRGAs in response to drought and ABA treatment. (A) Expression of the four BnaRGAs in response to drought treatment in WT analyzed by qRT-PCR. (B) Expression of the four BnaRGAs in response to ABA (100 μM) treatment in WT analyzed by qRT-PCR. These genes’ expression levels at 0 h were set as 1. BnaGAPDH was used as the internal control. Data are means ± SD obtained from three biological replicates. Asterisks show that the values are significantly different between the 0 h and different time point. The data were analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range tests in the ANOVA program of SPSS (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

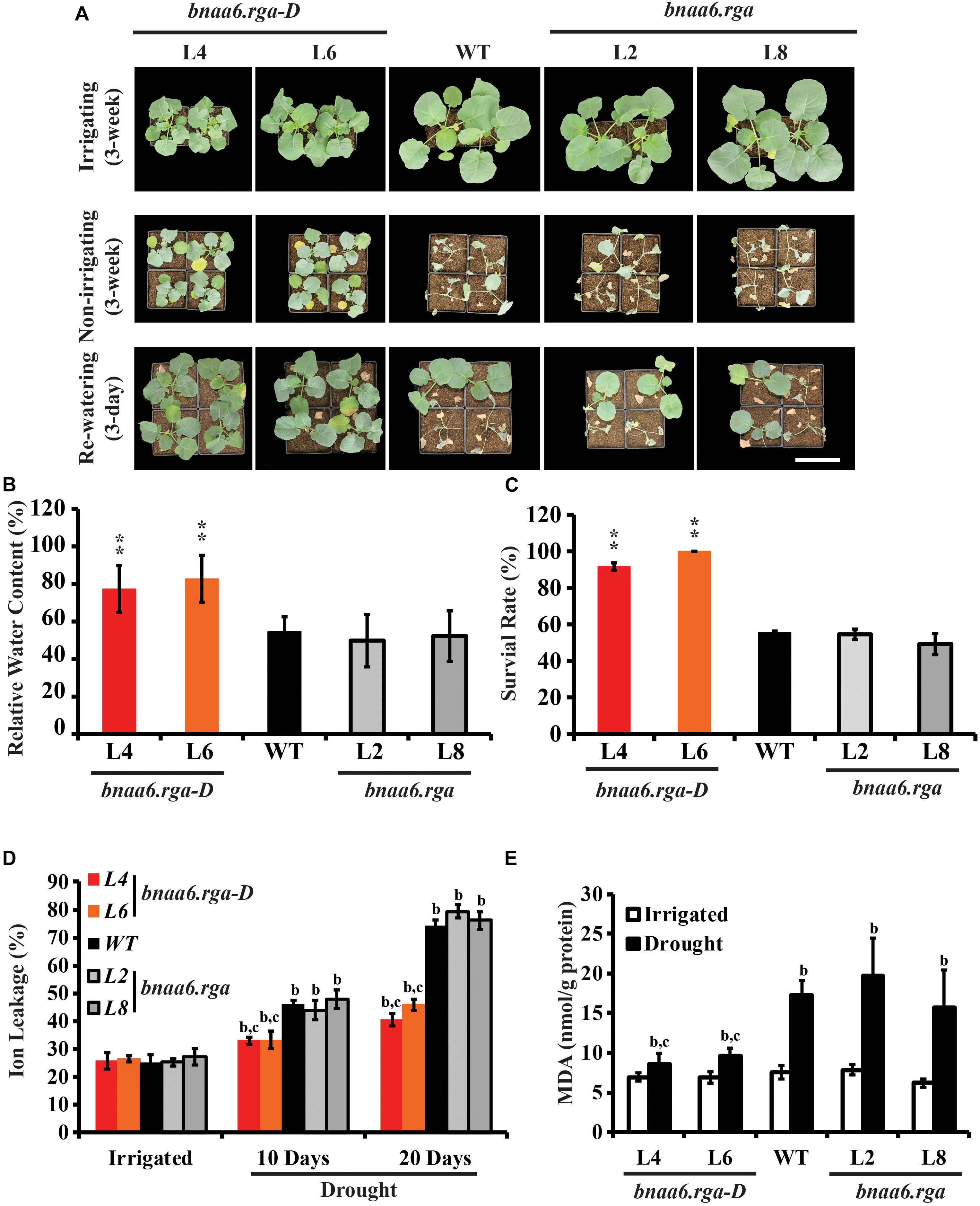

BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA Played Positive Roles in Drought Tolerance

Then, the genome editing of BnaRGAs was performed using CRISPR/Cas9 (Yang et al., 2017). Two types of mutants were generated among the transgenic plants according to the genotyping results. L4 and L6 are gain-of-function mutants of BnaA6.RGA, designated bnaa6.rga-D. In L4, there was a 6-nt deletion at the sgRNA2 target site that caused a two-amino acid deletion in the TVHYNP motif (Yang et al., 2017). In L6, there were both a 9-nt deletion at the sgRNA1 target site that caused a three-amino acid deletion in the DELLA motif and a 12-nt deletion at the sgRNA2 target site that caused a four-amino acid deletion in the TVHYNP motif (Yang et al., 2017). All the other lines possessed loss-of-function mutations. For example, there was a 118-nt deletion in L2 and 1-nt insertion in L8 at the sgRNA1 target site that caused frameshifts in BnaA6.RGA, designated bnaa6.rga. These mutations in bnaa6.rga also reduced the transcript level of BnaA6.RGA significantly (Supplementary Figure S1). These mutants provided precious materials for investigating BnaA6.RGA’s roles in drought tolerance in B. napus.

To determine whether BnaA6.RGA regulates drought resistance, 3-week-old wild type (WT; Westar), and bnaa6.rga and bnaa6.rga-D mutants, grown in pots were subjected to drought stress by withholding water for 20 days and then re-watering the plants for 3 days. After 20 days of water deprivation, the relative soil water content was almost the same in each pot (Supplementary Figure S2). We found almost half of the WT plants wilted, but the bnaa6.rga-D plants remained turgid (Figure 2A). The leaf relative water content (RWC) was consistent with the drought phenotype, being 77.3–82.7% in bnaa6.rga-D plants, which was greater than in WT (54.6%) (Figure 2B). After 3 days of re-watering, bnaa6.rga-D plants recovered well, and the survival rates of the two bnaa6.rga-D lines reached 91.7 and 100%. In contrast, the WT survival rate was only 55.6% (Figure 2C), which suggested that bnaa6.rga-D is more tolerant to drought stress. However, the survival rate and leaf RWC of bnaa6.rga were not significantly different from those of WT (Figures 2A–C).

Figure 2. Drought tolerance phenotypes of bnaa6.rga and bnaa6.rga-D. (A) Images showing the phenotypes of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaa6.rga in response to progressive drought stress. Images were taken for well-watered plants, at 20 days without irrigation, and at 3 days after rehydration. (B) Bar graph showing the leaf relative water content of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaa6.aga under water-deficit conditions in (A). (C) Bar graph showing the survival rates of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaa6.aga under water-deficit conditions followed by re-watering. (D) Bar graph showing the ion leakage of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaa6.aga in response to progressive drought stress. (E) Bar graph showing the MDA content of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaa6.aga before and after drought treatment. In (B) and (C) data are means ± SD (n = 10–15) obtained from three biological experiments. Asterisks show that the values are significantly different between the WT and different mutants at the same time point. The data were analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range tests in the ANOVA program of SPSS (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). In (D) and (E) letters indicate statistically significant differences between b: drought treatment vs control WT and c: drought treatment of mutants vs drought treatment of WT at P < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range tests). In (A–E) L4 and L6: two individual bnaa6.rga-D lines; L2 and L8: two individual bnaa6.rga lines; WT: Westar.

Ion leakage is an important indicator of cell injury. Then, the ion leakage was measured in irrigated versus water-deprived WT, bnaa6.rga-D and bnaa6.rga leaves. Under irrigated condition, no significant differences were found between the different lines (Figure 2D). After 10 days without irrigation, the ratio of ion leakage of bnaa6.rga-D was about 33.9%, which was less than WT (46.2%) (Figure 2D). After 20 days, the differences of ratio of ion leakage between bnaa6.rga-D and WT were much greater (Figure 2D), suggesting that membrane damage of WT was more serious than bnaa6.rga-D. Meanwhile, at the same drought condition, the ion leakage of bnaa6.rga was no different from WT (Figure 2D). Then, malondialdehyde (MDA) was measured in WT, bnaa6.rga-D and bnaa6.rga leaves, before or after the drought treatment. Compared to the WT, the MDA was less accumulated in bnaa6.rga-D, following exposure to the same drought condition (Figure 2E). These results indicated that bnaa6.rga-D could enhance the drought tolerance in B. napus.

Previously, the gain-of-function mutants of BnaC7.RGA, ds-3, was obtained by screening rapeseed EMS library (Zhao et al., 2017). A substitution of proline to leucine was identified in ds-3 in the conserved VHYNP motif, which is essential for GA-dependent interaction between GA receptor GID1 and DELLA proteins (Zhao et al., 2017). Then, we also tested the ds-3 in response to drought. ds-3 and WT (Huashang5, HS5) were subjected to the same drought treatment. Like bnaa6.rga-D, ds-3 plants remained turgid (Supplementary Figure S3A) after 3-week without watering, and the leaf RWC was about 95% (Supplementary Figure S3B). After 3 days of re-watering, ds-3 plants recovered well, and the survival rates was about 100% (Supplementary Figure S3C). The ion leakage and MDA content of ds-3 were less than WT (Supplementary Figures S3D,E). In contrast, the HS5 survival rate was almost 0% (Supplementary Figure S3C), which suggested that ds-3 is more tolerant to drought stress. Although BnaC7.RGA was not significant induced by drought or ABA, the gain-of-function mutants of BnaC7.RGA also showed strong drought tolerance, indicating that RGA proteins play the same functions in rapeseed drought tolerance.

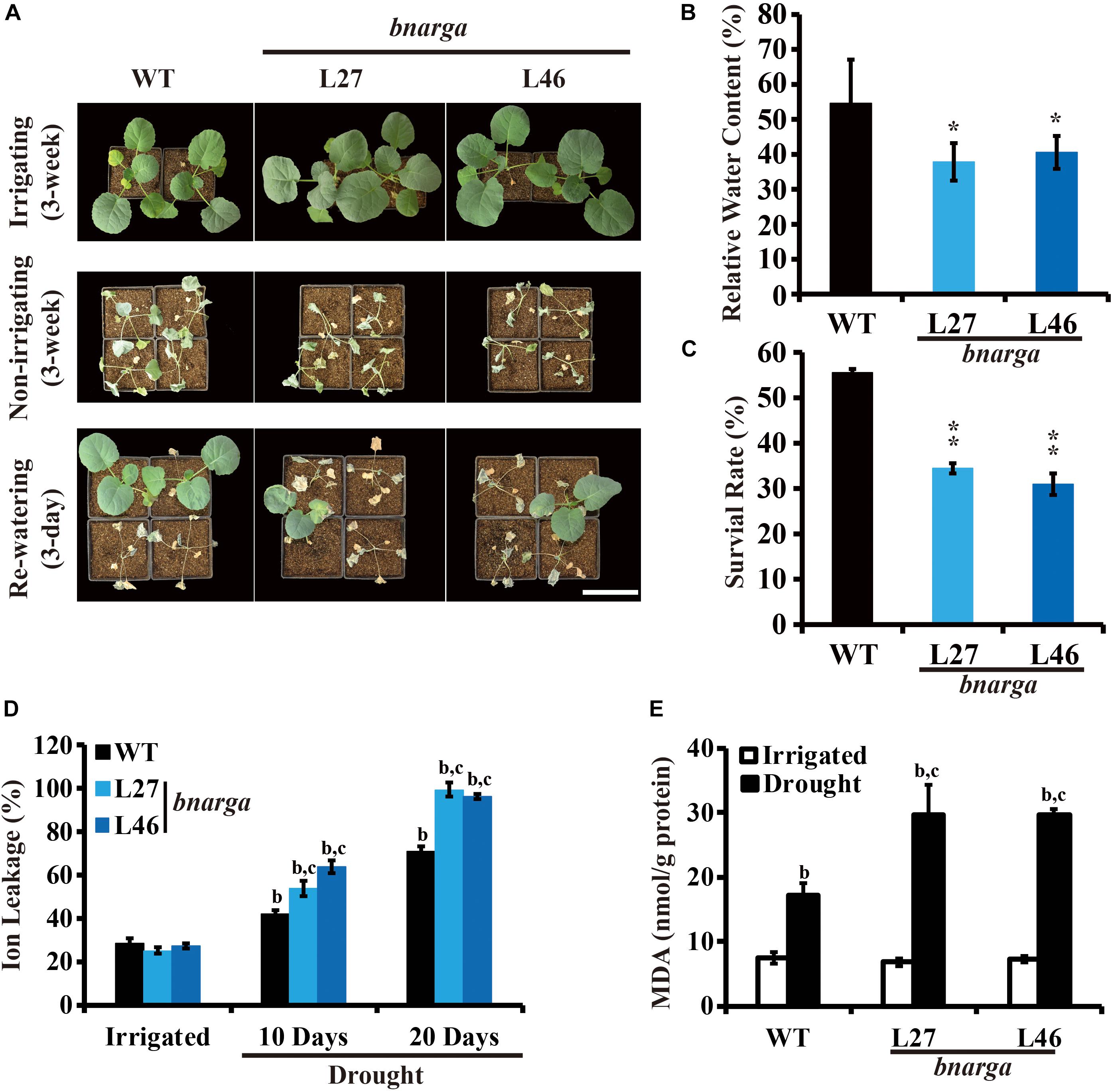

BnaRGAs Played Redundant Roles in Drought Tolerance

Because there are four BnaRGAs, we hypothesized that the other BnaRGA genes may act redundantly during drought tolerance. To test this hypothesis, single mutants of the other BnaRGAs (bnac7.rga, L7; bnaa9.rga, L5 and L16; and bnac9.rga, L3) and the quadruple mutant bnarga, L27 and L46 (Yang et al., 2017), were subjected to the same drought treatment. Like bnaa6.rga, the survival rates were similar among the single mutants and WT (Supplementary Figure S4). In contrast, a majority of the bnarga plants wilted after three weeks without watering (Figure 3A). The leaf RWCs of bnarga plants ranged from 37.9 to 40.6% (Figure 3B), which was lower range than that of the WT. After re-watering, the two lines of bnarga plants, L27 and L46, recovered poorly, with survival rates of only 34.4 and 31.0%, respectively, indicating that bnarga is more sensitive to drought stress than WT (Figure 3C). After 10 days without irrigation, the ratio of ion leakage of bnarga was about 55–60%, which was more than WT (46.2%) (Figure 3D). After 20 days, the differences of ratio of ion leakage between bnarga and WT were much greater (Figure 3D), suggesting that membrane damage of bnarga was more serious than WT. The MDA was more accumulated in bnarga, following exposure to the same drought condition (Figure 3E). Thus, BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA positively regulates drought tolerance in B. napus, while other BnaRGAs have redundant functions in this process.

Figure 3. Drought tolerance phenotypes of bnarga. (A) Images showing the phenotypes of WT, and bnarga in response to progressive drought stress. Images were taken for well-watered plants, at 20 days without irrigation, and at 3 days after rehydration. (B) Bar graph showing the leaf relative water content of WT, bnaaga under water-deficit conditions in (A). (C) Bar graph showing the survival rates of WT and bnarga under water-deficit conditions followed by re-watering. (D) Bar graph showing the ion leakage of WT, and bnaaga in response to progressive drought stress. (E) Bar graph showing the MDA content of WT, and bnaaga before and after drought treatment. In (B) and (C) data are means ± SD (n = 10–15) obtained from three biological experiments. Asterisks show that the values are significantly different between the WT and different mutants at the same time point. The data were analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range tests in the ANOVA program of SPSS (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). In (D) and (E) letters indicate statistically significant differences between b: drought treatment vs control WT and c: drought treatment of mutants vs drought treatment of WT at P < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range tests). In (A–E) L27 and L46: two individual bnarga lines; WT: Westar.

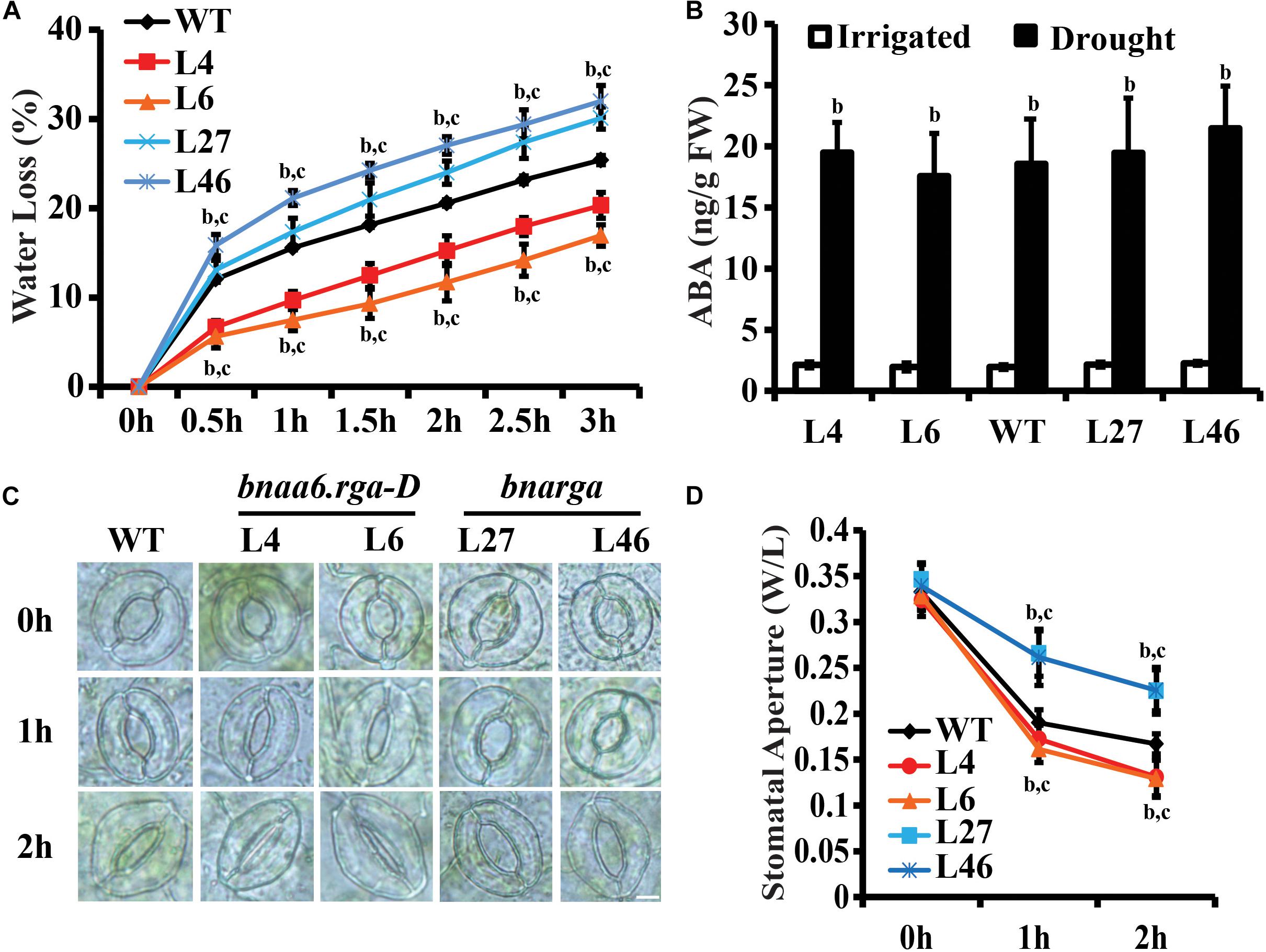

BnaRGA Promoted Stomatal Closure in Response to Abscisic Acid

Reducing water loss is a key determinant of drought tolerance (Xiong et al., 2002). The BnaRGA mutants exhibited different sensitivities to drought stress. To uncover the underlying causes, weights of the detached leaves from these mutants were measured every half hour for 3 h after detachment. The bnarga quadruple mutants displayed significantly greater water loss rate, while bnaa6.rga-D and ds-3 showed a significantly lower water loss rate in comparison to that of WT (Figure 4A, Supplementary Figure S5A). Thus, the expression of BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA appears to reduce drought-induced water loss.

Figure 4. Water loss of detached leaves and stomatal aperture after ABA treatment of bnaa6.rga-D and bnarga. (A) Water loss of detached leaves of bnaa6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT. Leaves at similar developmental stages were excised and weighed at the indicated time after detachment. The proportion of fresh weight losses was calculated on the basis of the initial weight of the leaves. (B) Bar graph showing the ABA content of WT, bnaA6.rga-D, and bnaaga in response to progressive drought stress. (C) Images of the representative stomata of bnaa6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT at 0, 1, and 2 h with or without ABA (1 μM) treatment. Scale bars: 10 μm. (D) Line graph showing the stomatal apertures measured from (C). In (A), (B), and (D) data are means ± SD [n = 5–6 for (A) and (B); n = 150–200 for (D)] obtained from three biological experiments. In (A), (B), and (D) letters indicate statistically significant differences between b: drought (or ABA) treatment vs control WT and c: drought (or ABA) treatment of mutants vs drought (or ABA) treatment of WT at P < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range tests). In (A–D) L4 and L6: two individual bnaa6.rga-D lines; L2 and L8: two individual bnaa6.rga lines; L27 and L46: two individual bnarga lines; WT: Westar.

The drought stress induces ABA biosynthesis (McAdam and Brodribb, 2016), which, in turn, promotes stomatal closure. We first analyzed ABA levels in well-watered versus water-deprived WT, bnaa6.rga-D, and bnarga leaves. After 10 days without irrigation, the soil RWC of all plants reached round 40%. Under irrigation, no significant differences in ABA content were found between the different lines (Figure 4B). While the water deficit treatment increased ABA levels in all lines, which was no significant differences in different lines (Figure 4B). These results suggest that BnaRGAs does not promote ABA accumulation in B. napus leaves.

Measuring ABA-induced stomatal closure is a well-established assay for studying plant responses to drought stress (Mustilli et al., 2002). To evaluate whether BnaRGAs affects stomatal response to ABA, we treated peeled abaxial epidermal strips taken from bnaa6.rga-D, ds-3, bnarga, and their relative wildtype leaves with ABA treatment and monitored stomatal closure. The stomata of WT (Westar), bnaa6.rga-D and bnarga were induced to be wide open before the ABA treatment (Figures 4C,D). After the ABA treatment, the stomatal apertures of all these plants decreased; however, bnaa6.rga-D was more sensitive than WT, while the bnarga plants were less sensitive (Figures 4C,D). Specifically, 1 h after the ABA treatment, the average stomatal aperture (width/length) of the WT was 0.19, while those of the two bnaa6.rga-D were 0.16 to 0.17, and that of bnarga was 0.26 (Figures 3C,D, P < 0.01). At 2 h after the ABA treatment, the differences between stomatal apertures were much greater (Figures 4C,D). The same pattern was found between ds-3 and HS5 (Supplementary Figures S5A–C). Thus, the stomatal closures of the BnaRGA mutants in response to the ABA treatment were consistent with the wilting phenotypes under drought-stress conditions.

BnaRGAs Physically Interacted With BnaA10.ABF2

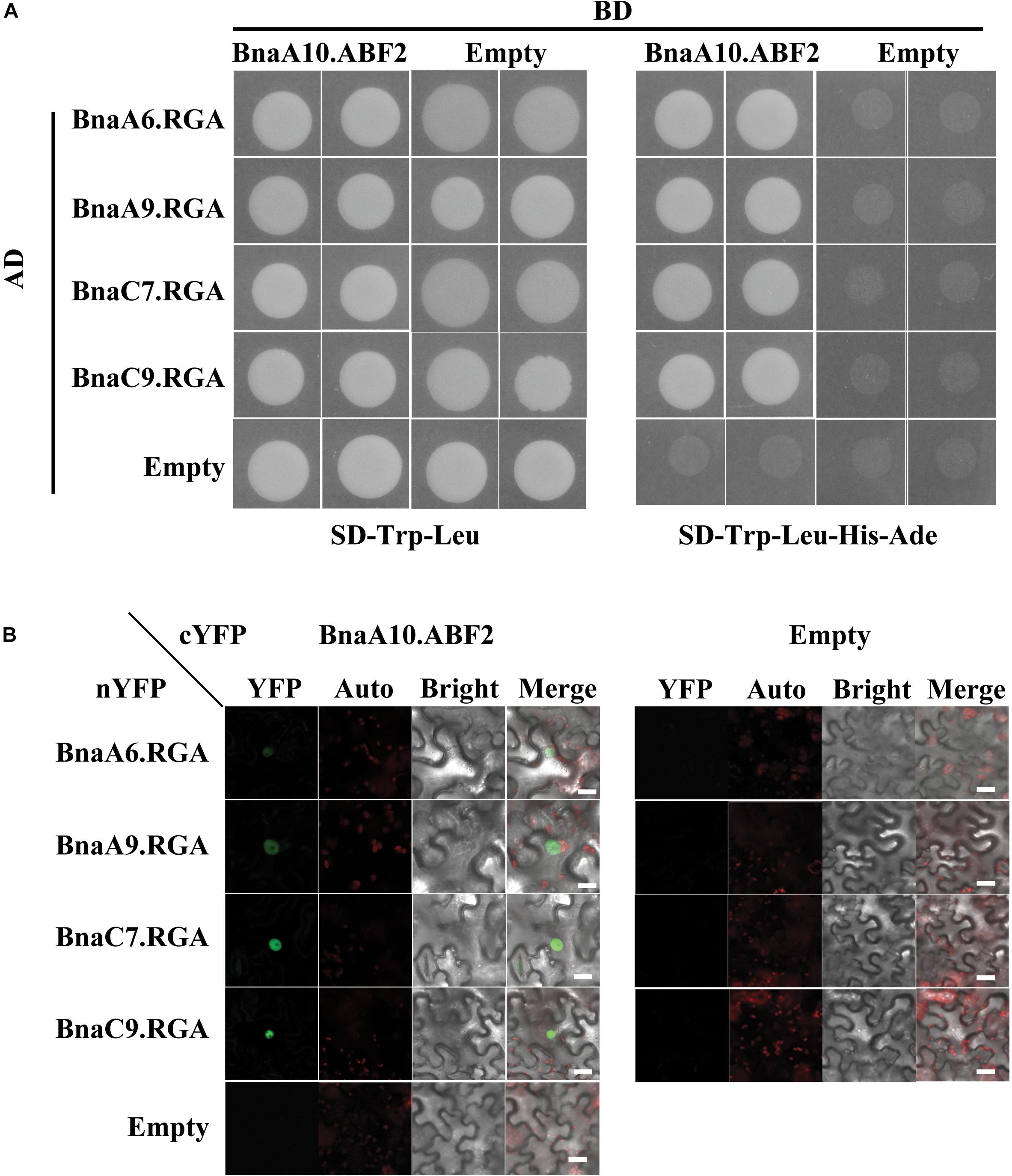

DELLA proteins usually play roles by interacting with other transcription factors (Van De Velde et al., 2017). In Arabidopsis, RGA can interact with the bZIP transcription factor ABI5 to regulate seed germination (Lim et al., 2013). The bZIP transcription factor BnaA10.ABF2 positively regulates plant drought tolerance when transformed into Arabidopsis (Zhao et al., 2016). Thus, we hypothesized that BnaA6.RGA might directly interact with BnaA10.ABF2. We used a yeast two-hybrid system to test this possibility, and it indicated that these two proteins interact (Figure 5A). A phylogenetic analysis revealed that the BnaA10.ABF2 protein belongs to the ABF2 clade of the ABRE family along with three other paralogs (Supplementary Figure S6). Three other BnaRGA proteins could also physically interact with BnaA10.ABF2 (Figure 5A). Then, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) was performed to examine the interactions between BnaA10.ABF2 and the four BnaRGA proteins. The YFP fluorescence occurred specifically in the nucleus only when BnaA10.ABF2-cYFP and each BnaRGA-nYFP were expressed simultaneously in tobacco leaves (Figure 5B). Without the GRAS domain, BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA could not interact with BnaA10.ABF2 (Supplementary Figure S7). These results suggest that BnaA10.ABF2 physically interacted with BnaRGAs to form a protein complex.

Figure 5. Each of the four BnaRGAs physically interact with BnaA10.ABF2. (A) Each of the four BnaRGAs interacted with BnaA10.ABF2 in the Y2H assay. (B) Each of the four BnaRGAs interacted with BnaA10.ABF2 in the BiFC assay performed in the N. benthamiana leaves. Scale bars: 50 μm. Images were acquired by confocal microscope using the identical settings. YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; auto, chloroplast auto fluorescence; bright, bright field; merge, the figure merged by YFP, auto, and bright.

BnaRGA-BnaA10.ABF2 Complex Enhances the Expression of BnaC9.RAB18

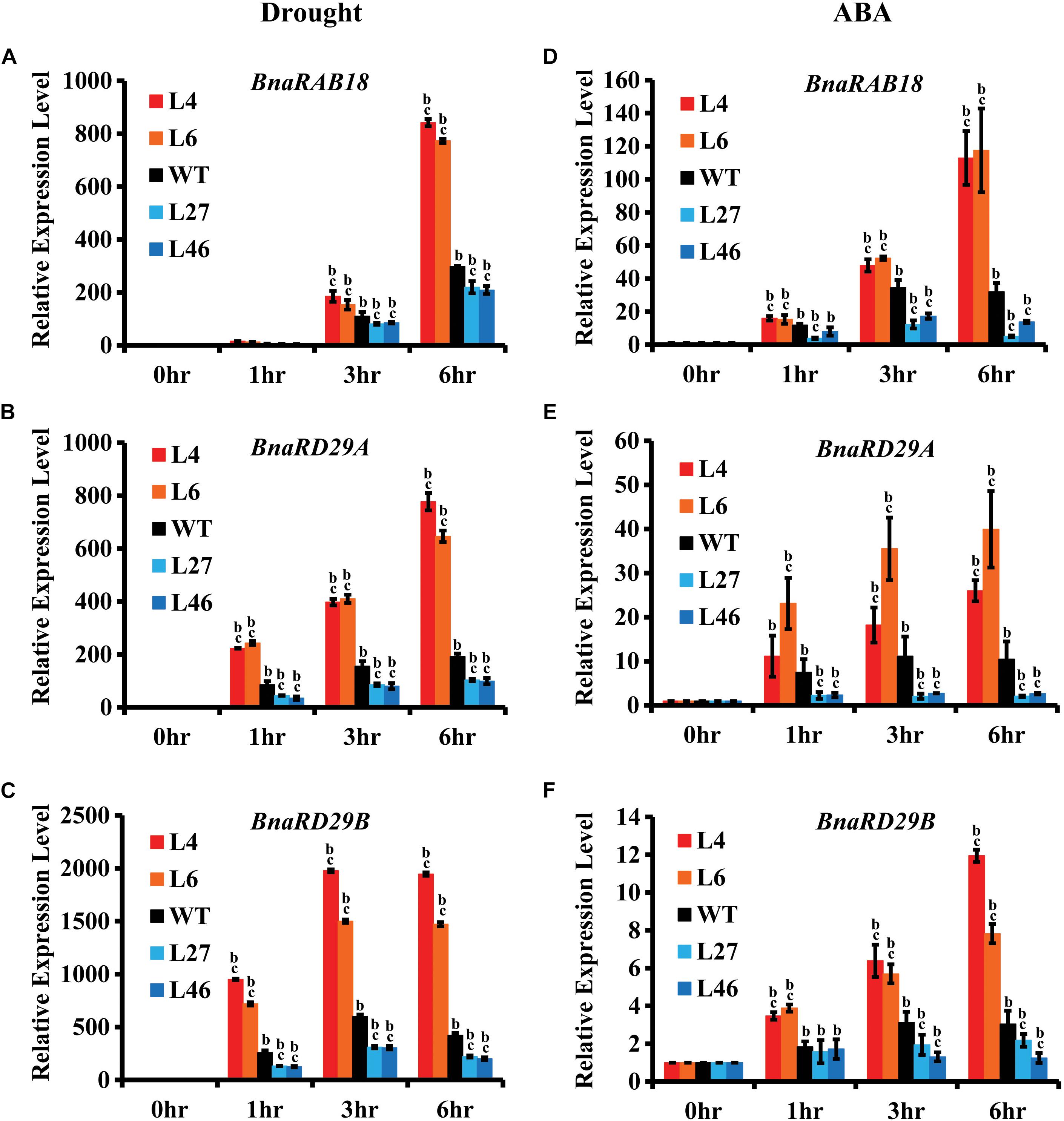

Because BnaRGA proteins physically interact with BnaA10.ABF2, we speculated that BnaRGAs may affect the expression of ABF2’s downstream genes. To investigate this possibility, the expression levels of its downstream genes were examined in bnaA6.rga-D, bnarga and WT after the drought or ABA treatment. After the drought treatment, the expression of BnaRAB18 was about 12.8–841.8 times induced in bnaa6.rga-D (Figure 6A), which was much greater than in WT. Under the same conditions, the expression of BnaRAB18 was induced to a lesser extent in bnarga (Figure 6A). Similarly, BnaRD29A and BnaRD29B were also significantly up-regulated in bnaa6.rga-D and up-regulated to a lesser extent in bnarga compared with WT (Figures 6B,C). After the ABA treatment, these three downstream genes were all greatly induced in bnaa6.rga-D, but were induced to a significantly lesser extent in bnarga (Figures 6D–F). The same results were observed in ds-3 after drought treatment (Supplementary Figures S8A–C). Thus, BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA may promote drought tolerance by enhancing the expression of BnaA10.ABF2’s downstream genes.

Figure 6. Expression of BnaRAB18, BnaRD29A, and BnaRD29B in bnaa6.rga-D and bnarga in response to drought and ABA treatment. (A–C) Expression levels of BnaRAB18 (A), BnaRD29A (B), and BnaRD29B (C) in bnaa6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT after drought treatment examined by qRT-PCR. (D–F) Expression levels of BnaRAB18 (D), BnaRD29A (E), and BnaRD29B (F) in bnaa6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT after ABA treatment examined by qRT-PCR. The expressions level of each gene at 0 h was set as 1. BnaGAPDH was used as the internal control. Data are means ± SD obtained from three biological replicates. In (A–F) letters indicate statistically significant differences between b: drought (or ABA) treatment vs control WT and c: drought (or ABA) treatment of mutants vs drought (or ABA) treatment of WT at P < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range tests). In (A–F) L4 and L6: two individual bnaa6.rga-D lines; L2 and L8: two individual bnaa6.rga lines; L27 and L46: two individual bnarga lines; WT: Westar.

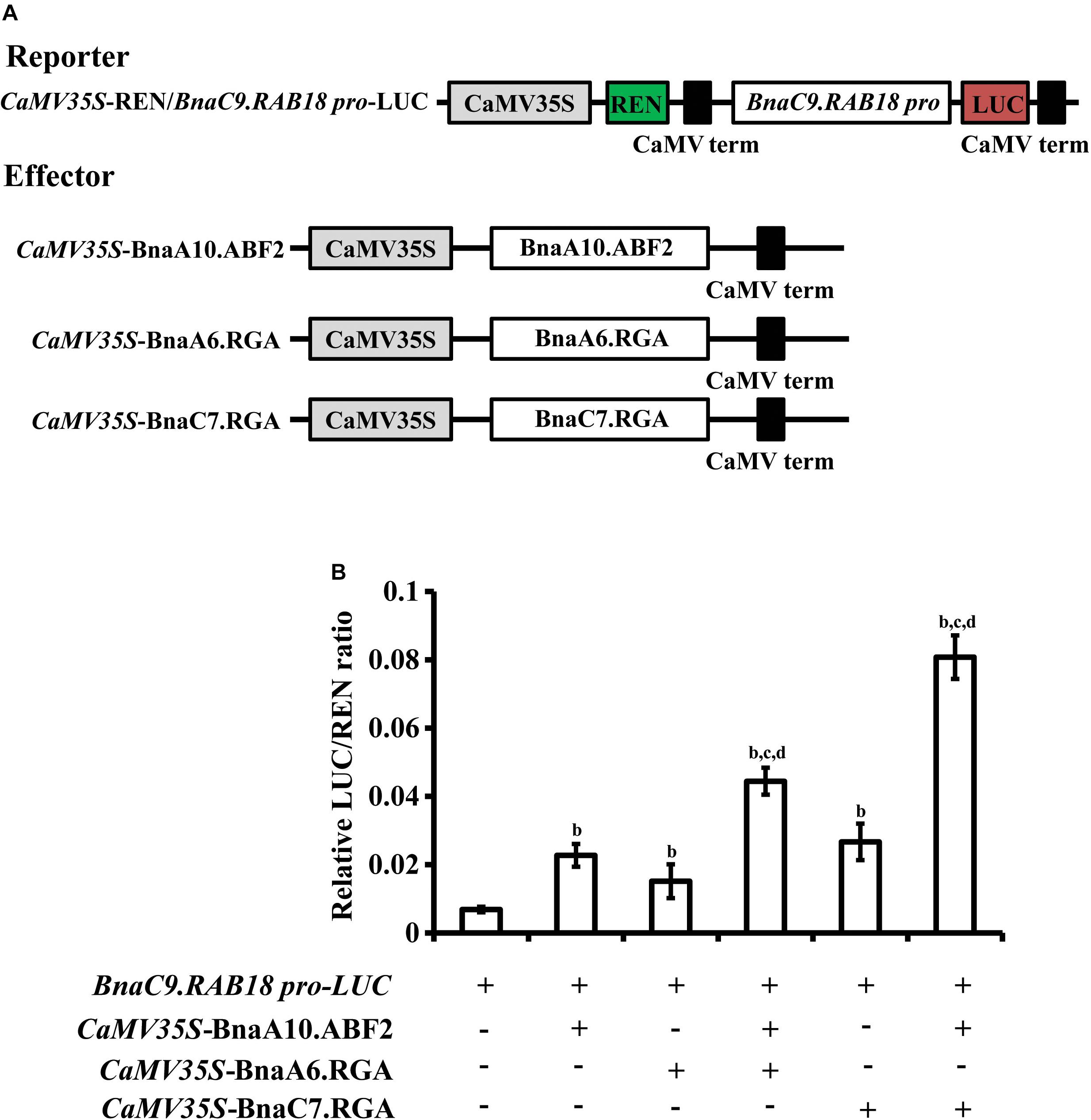

In Arabidopsis, ABF2 activates expression of RAB18 (Fujita et al., 2005). Therefore, we used the dual luciferase reporter assay to determine whether BnaA10.ABF2 could promote the expression of BnaRAB18 in B. napus. The reporter vector contained a firefly luciferase gene driven by the BnaC9.RAB18 promoter and a renilla luciferase (REN) gene driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. BnaA6.RGA, BnaC7.RGA and BnaA10.ABF2 were each driven by the CaMV 35S promoter in independent effector vectors (Figure 7A). The LUC activity was measured for different combinations. Compared with the expression of pBnaC9.RAB18-LUC only, the LUC enzyme’s activity level was 3.7 times greater when BnaA10.ABF2 was co-expressed (Figure 7B). Furthermore, when BnaA6.RGA or BnaC7.RGA was expressed together with BnaA10.ABF2, the activity of pBnaC9.RAB18-LUC was increased by 6.5 or 11.8 times, respectively (Figure 7B). Without the GRAS domain, BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA could not interact with BnaA10.ABF2, and the expression levels of the reporter genes were less enhanced (Supplementary Figure S9). Collectively, these results suggested that BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA may form a complex with BnaA10.ABF2 to promote the expression of BnaC9.RAB18.

Figure 7. Transcriptional regulation of BnaC9.RAB18 by BnaA10.ABF2 was enhanced by BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA, respectively. (A) Schematic representation of the constructs used for the dual-luciferase assay. The reporter construct contains the firefly luciferase driven by BnaC9.RAB18 promoter, and the Renilla luciferase (REN) driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The effector constructs contain BnaA6.RGA, BnaC7.RGA, and BnaA10.ABF2 driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, respectively. (B) Bar graph showing the LUC/REN ratios in the dual-luciferase assay. In (B) letters indicate statistically significant differences between b: co-infiltrated effectors with reporters (BnaC9.RAB18p-LUC) vs reporters only, c: co-infiltrated effectors (BnaA6.RGA + BnaA10.ABF2, or BnaC7.RGA + BnaA10.ABF2) with reporters vs co-infiltrated effectors (BnaA10.ABF2) with reporters, and d: co-infiltrated effectors (BnaA6.RGA + BnaA10.ABF2, or BnaC7.RGA + BnaA10.ABF2) with reporters vs co-infiltrated effectors (BnaA6.RGA, or BnaC7.RGA) with reporters at P < 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple range tests).

In Arabidopsis, the RGA protein promotes the expression of XERICO, an E3 ligase, which promotes destabilization of the ABA catabolic gene to antagonize GA effects (Zentella et al., 2007). After the drought treatment, the expression of BnaXERICO was 6.1 to 18.2 times induced in bnaa6.rga-D (Supplementary Figure S10A), which was much greater than in WT. Under the same conditions, the expression of BnaXERICO was not significantly induced in bnarga (Supplementary Figure S10A). Similarly, BnaA10.ABF2 and BnaC6.ABF2 (a paralog of BnaABF2) were also significantly up-regulated in bnaa6.rga-D and up-regulated to a lesser extent in bnarga (Supplementary Figure S10B). Thus, DELLA proteins appear to positively regulate ABA metabolic- and signaling-related genes.

The Expression Levels of GA Signaling Genes Were Suppressed by Drought

In plants, DELLA proteins are degraded by GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 (GID1)-mediated pathways (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007). Therefore, we speculated that these GA signaling genes would be responsive to drought. To investigate this possibility, the expression levels of GA signaling genes were examined in bnaA6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT after the drought treatment. At 1 h after the drought treatment, the expression levels of BnaGID1a, and BnaGID1c, and BnaSLY1 were greatly reduced, and then increased (Supplementary Figure S11), suggesting that GA negatively regulates plant drought tolerance by decreasing the stabilities of DELLA proteins. The expression of BnaGID1a was about 1.5–6.9 times induced in bnaa6.rga-D after drought treatment (Supplementary Figure S11A), which was much greater than in WT. Under the same conditions, the expression of BnaGID1a was repressed in bnarga (Supplementary Figure 11A). Similarly, BnaGID1b were also significantly up-regulated in bnaa6.rga-D and suppressed in bnarga compared with WT (Supplementary Figure S11B). However, the expression pattern of BnaSLY1 was no difference among bnaA6.rga-D, bnarga, and WT after the drought treatment (Supplementary Figure S11C). The expression levels of BnaGID1a and BnaGID1c were suppressed, and then increased, indicating that the feedback regulation between DELLA and GID1 could promote the latter’s transcription.

Discussion

BnaA6.RGA Plays Important Roles in Controlling the Drought Tolerance of B. napus

Under water-deficit conditions, ABA and other small molecules rapidly accumulate, which confers drought tolerance in B. napus (Zhu et al., 2010). Sequence analyses have identified all the ABA biosynthesis and signaling components in B. napus, indicating that this pathway is conserved in this species (Zhu et al., 2016). Although ABA pathway genes, as well as some other stress responsive genes, are up-regulated by drought stress in B. napus (Li et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2010), whether these genes play important roles during drought tolerance remains obscure owing to the lack of genetic evidences. Here, our results indicated that BnaRGA proteins, key repressors of GA signaling, promoted drought tolerance by interacting with BnaABF2 in B. napus. The identification of these GA genes provided us insights into the regulatory mechanisms of drought resistance in B. napus.

The Gibberellin Pathway Mediates the Regulation of Drought Tolerance

Gibberellin mediates various developmental processes throughout the life cycle of the plant, and a GA deficiency results in severe dwarfism (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007). In addition to promoting plant growth and development, GA biosynthesis or signaling is involved in modulating plant abiotic resistance to stresses, such as drought, salinity, and other environmental stimuli (Magome et al., 2008; Colebrook et al., 2014; Nir et al., 2014, 2017). Specifically, the GA deficient mutants ga20ox1/2 and ga3ox1/2 are more resistant to drought in Arabidopsis (Colebrook et al., 2014). Overexpressing the GAMT gene, which encodes a GA methyltransferase, enhances tolerance to water-deficit stress in tomato (Nir et al., 2014). The loss of DELLA encoding genes, such as the mutant procera in tomato (Nir et al., 2017), results in rapid water loss under water-deficit conditions, and the daily transpiration level is decreased in the tomato GID1 double mutant (Illouz-Eliaz et al., 2019). Although GA is critical for stress responses in Arabidopsis and tomato, there are no reports on its roles in B. napus. We found that gain-of-function of BnaA6.RGA and BnaC7.RGA mutants (bnaa6.rga-D and ds-3) were more tolerant to drought. However, the loss of the four BnaRGA genes (bnarga) led to a hypersensitivity to drought (Figure 3), suggesting that the functions of GA pathway genes in plant drought tolerance are conserved.

DELLA family proteins are key repressors in GA signal transduction (Van De Velde et al., 2017). When the GA level is increased, DELLA proteins interact with GID1 and are degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway to promote the expression of GA-responsive genes (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007). The expression levels of the positive regulators of GA signaling, such as GA receptor (GID1a/c) and F-box (SCFSLY1/2) genes, were greatly reduced by drought treatments, consistent with the results in Arabidopsis (Kilian et al., 2007), which might stimulate DELLA protein accumulation. However, expression levels of GID1 were first reduced and then increased, which was depended on BnaRGA (Supplementary Figure S11), indicating that the feedback regulation between DELLA and GID1 could promote the latter’s transcription, as reported in Arabidopsis (Zentella et al., 2007). Therefore, we speculate that GA negatively regulates plant drought tolerance by suppressing the stability levels of DELLA proteins.

As an allotetraploid species, a majority of genes in B. napus are present in multiple copies that share high sequence similarities. BnaA6.RGA, BnaA9.RGA, and BnaC9.RGA were induced by drought and ABA (Figure 1), suggesting that other DELLA proteins regulate drought responses together with BnaA6.RGA. Consistent with this hypothesis, no significant differences were found between the single mutants of the four BnaRGAs and WT after the drought treatment, while the quadruple mutant bnarga significantly decreased the sensitivity of stomatal closure. These findings indicate that RGA proteins function redundantly in enhancing drought tolerance in B. napus. Although the expression pattern was quite different among the four paralogs of BnaRGA after the drought treatment, protein interaction assay indicated that all four BnaRGAs could interact with BnaA10.ABF2, and ds-3 also displayed more drought tolerance than WT, suggesting different BnaRGA-BnaA10.ABF2 complex might co-activate drought related genes in different tissues or at the different time point.

BnaRGA Directly Interacted With the Abscisic Acid-Signaling Component BnaABF2 to Regulate Drought Tolerance

Abscisic acid plays important roles in drought tolerance. ABA-mediated stomatal closure is involved in drought tolerance (Xiong et al., 2002). The ABA-induced stomatal closure rate was accelerated in bnaa6.rga-D, suggesting that ABA’s response was enhanced. However, the effects of DELLA on stomatal aperture are strongly suppressed in ABA-deficient mutants (Nir et al., 2017), indicating that these functions are ABA-dependent. DELLA proteins belong to a subgroup of the GRAS transcription factor family, which lack a DNA-binding domain (Yoshida et al., 2014). Thus, DELLA proteins usually function by interacting with other DNA-binding proteins to regulate the transcriptional activity of downstream genes (Van De Velde et al., 2017). In this way, DELLA proteins not only promote ABA biosynthesis (Zentella et al., 2007; Piskurewicz et al., 2008) but also the signaling components (Lim et al., 2013). Here, BnaA10.ABF2 interacted directly with each of the four BnaRGAs (Figure 4), providing a direct link between the ABA and GA signaling pathways during drought tolerance. Moreover, this protein interaction enhanced the expression of downstream drought-responsive genes (Figure 7). These results revealed a regulatory mechanism underlying drought tolerance in B. napus.

In Arabidopsis, the RGA protein promotes the expression of XERICO which destabilized the ABA catabolic genes (Zentella et al., 2007). Similarly, we found that the expression of BnaXERICO was up-regulated in bnaa6.rga-D and down-regulated in bnarga (Supplementary Figure S10A). Additionally, the ABA signaling genes BnaA10.ABF2 and BnaC6.ABF2 were also induced in bnaa6.rga-D (Supplementary Figure S10B). These results suggested that DELLA proteins positively regulate stomatal movement by up-regulating ABA signaling-related genes and down-regulating ABA catabolic genes. After the long-term drought treatment, drought induces similar levels of ABA accumulation in bnaa6.rga-D and bnarga lines, indicating that drought induced ABA accumulation might include BnaRGA-dependent and -independent way.

The N-terminal DELLA domain is important for the degradation of these proteins. Plants constitutively expressing a truncated DELLA, lacking the DELLA or TVHYNP motif, have growth defects that mimic a GA shortage, such as severe dwarfism, which is significantly reduced the crop yield (Fleet and Sun, 2005; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2017). There are several strategies have been developed for generating transgenic plants which is improved one agronomic trait without affecting others. For example, expression levels of PRO driven by guard cell-specific promoters greatly increase tomato drought tolerance but have no obvious effects on plant growth (Nir et al., 2017). The other strategy uses CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing toolkits to generate diverse cis-regulatory alleles that provide beneficial quantitative variation for breeding (Rodriguez-Leal et al., 2017). These reports provide new strategies to generate drought-tolerant crops and speed up molecular breeding in the future.

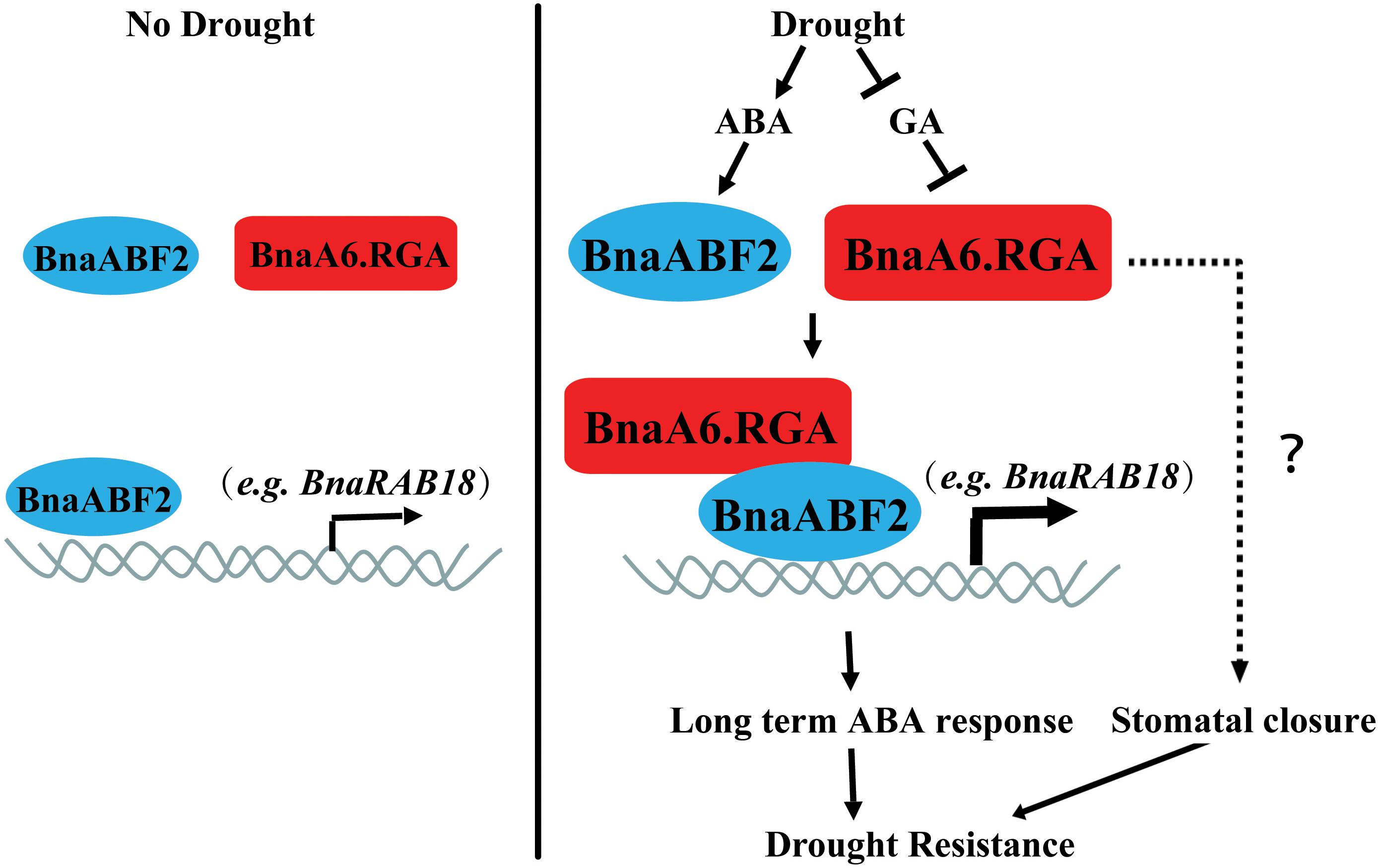

In summary, our findings indicate that BnaRGA proteins play important roles in plant adaptation to water-deficit stress. We proposed a working model for BnaA6.RGA-mediated drought tolerance in B. napus (Figure 8). Drought leads to an ABA accumulation and a GA reduction, which induces the expression of ABF2 and promotes the RGA accumulation. The BnaA6.RGA-BnaABF2 complex enhances the expression of drought responsive genes (such as BnaRAB18), resulting in enhanced ABA signaling, which then increases the plant’s drought resistance. In addition, the accumulated BnaA6.RGA might enhance guard cell sensitivity to ABA by an unknown mechanism, which leads to rapid stomatal closure. Both long term and short term of ABA responses enhance plant drought resistance (Figure 8). Our findings provide novel insights into the crosstalk between GA and ABA signaling pathways, and the editing resources obtained in our study provide desirable germplasm for further breeding of drought tolerance in rapeseed.

Figure 8. Working model for the regulatory mechanism of BnaA6.RGA in the drought stress responses. Drought leads to an ABA accumulation and a GA reduction, which induces the expression of ABF2 and promotes the RGA accumulation. The BnaA6.RGA-BnaABF2 complex positively regulate drought responsive genes (such as BnaRAB18) expression levels, resulting in enhanced ABA signaling, which then increases the plant’s drought resistance. In addition, the accumulated BnaA6.RGA might enhance guard cell sensitivity to ABA by an unknown mechanism, which leads to rapid stomatal closure. Both long term and short term of ABA responses enhance plant drought resistance.

Experimental Procedures

Plant Materials and Growth Condition

The single mutants, bnaa6.rga, bnac7.rga, bnaa9.rga, bnac9.rga, quadruple mutant bnarga, and gain-of-function mutant bnaa6.rga-D were generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 technology in B. napus (Westar) (Yang et al., 2017). The gain-of-function mutants of BnaC7.RGA, ds-3, was obtained by screening rapeseed EMS library (Zhao et al., 2017). To germinate, the seeds were soaked in water for 7 days and then placed in soil. All plants were cultivated in a growth room under a light intensity of 120 μmol m–2 s–1 with a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod (23 ± 1°C and 60–70% RH).

Plasmid Construction

Each gene was amplified from the B. napus cDNA library by PCR using gene-specific primers. For the yeast two hybrid assay, the BnaA10.ABF2 coding region was cloned into the vector pGBKT7 as the bait (Clontech, United States), while the constructs of pGADT7-BnaA6/A9/C7/C9.RGA serving as the prey were obtained from the previous report (Zhao et al., 2017). For the BiFC assay, the full-length coding regions of BnaRGAs, and the N terminus of BnaA6.RGA (1–148 amino acid)/BnaC7.RGA (1–132 amino acid), and the C terminus of BnaA6.RGA (149–572 amino acid)/BnaC7.RGA (133–556 amino acid) were cloned into the vector pFGC-YN173 fused with the N terminus of YFP, and BnaA10.ABF2 was inserted into the vector pFGC-YC155 fused with the C terminus of YFP. For the dual luciferase assay, the full-length coding regions of BnaA6.RGA, BnaC7.RGA, BnaA10.ABF2, and the N terminus of BnaA6.RGA (1–148 amino acid)/BnaC7.RGA (1–132 amino acid) were inserted into the vector pRI101-GFP as the effectors, while the 1,496 bp promoter of BnaC9.RAB18 was cloned into the vector pGreenII 0800-LUC as the reporter. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Measurement of Water Loss

To measure the water loss, the leaves were detached from 3-week-old plants and placed in a petri dish on a laboratory bench (23 ± 1°C and 30–40% RH), and the weight of the detached leaves was then measured every 0.5 h for a period of 3 h. The experiment was repeated three times. For each repeat, at least five leaves from different plants of each genotype were used. Water loss was presented as the percentage of the fresh weight (FW) loss.

Drought Treatment and Relative Water Content

One-week-old plants were transferred from the Hoagland medium to the same weight of water-saturated soil for growing in the greenhouse for 2 weeks, and then deprived of water for 20 days. Each pot contained 130 ± 0.1 g (dry weight, DW) of soil and one plant. The pots were irrigated with water to saturation, allowed to drain, and then weighted to obtain the initial weight, after which they were subjected to drought for different time periods. The relative soil water content (SWC) was calculated as: SWC = (final FW − DW)/(initial weight − DW) × 100. Subsequently, the survival rates of plants were determined after three days of re-watering (rehydration).

The RWC of fully expanded leaves from 3-week-old plants grown in pots was measured after 3 weeks of drought treatment. Frist, leaves were removed and immediately weighted to obtain the FW. The leaves were then placed into petri dishes filled with ddH2O. After 24 h, the leaves were blotted to remove external water, and then weighted to obtain the leaf turgid weight (TW). Finally, leaves were dried to a constant weight at 60°C and then weighted to obtain the leaf DW. The RWC of leaves was calculated as: RWC = (FW − DW)/(TW − DW) × 100.

Measurement of Stomatal Aperture

Stomatal assays were performed as previously described (Desikan et al., 2002). In brief, five fully expanded leaves were harvested from different 3-week-old plants for each genotype and incubated in the MES-KCl buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MES-KOH, pH 6.15) under light at 22°C for 3 h. Once the stomata were fully open, leaves were incubated in the MES-KCl buffer with 1 μM of ABA or DMSO (control). After 1–2 h of treatment, the epidermal strips were immediately peeled from the abaxial side of leaves. After that, 30–40 stomata from one leaf were measured, adding up to 150–200 stomata for each genotype. The pictures were taken by microscope equipped with a digital camera (AxioCam ICc5, Zeiss). Stomatal aperture was analyzed using the software Image J. Three independent repeats were performed.

Abscisic Acid Assay

Abscisic acid contents were measured as previously described (Ding et al., 2011). In brief, leaves were harvested from plants that were irrigated or non-irrigated for 10 days. The leaves (about 200 mg) were ground in liquid N2 and homogenized in 90% (v/v) methanol containing 200 mg L–1 of diethydithiocarbamic acid sodium salt. The extracts were then incubated overnight in darkness at 4°C, followed by a 8,000 × g centrifugation at 4°C. The methanolic supernatant was vacuumed centrifuge at 4°C to evaporate the supernatant, and the residue was dissolved by methanolic Tris buffer (10% methanol, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl). An ELISA kit was used for the determination of ABA following the manufacturer’s instructions (Agdia1). Three independent repeats were performed.

Measurement of Ion Leakage and Malondialdehyde

The membrane ion leakage was measured as described previously with slight modifications (Lee et al., 2011). In brief, five fully expanded leaves, that were irrigated or non-irrigated for 10 or 20 days, were harvested from bnaa6.rga-D, ds-3, bnarga, and their relative wild-type plants. Then, a hole puncher was used to obtain 60 leaf disks from each leaf. The leaf disks were transferred to glass test tubes filled with 10 mL of ddH2O, and vacuumed until the leaf disks were submerged by water. After that, the tubes were shaken on an oscillator for 1 h. Electrical conductivity was measured in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (BANTE, China). The initial conductivity was measured as R1. Total conductivity was determined after boiling for 10 min as R2. The relative ion leakage was calculated by using the following formula: R1/R2 × 100%.

Malondialdehyde content, expressed as units/mg protein, was measured using analytical kits (Cat#A003-2, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). In all experiments, three independent repeats were performed.

RNA Extraction and Reverse-Transcription PCR

For transient ABA or drought treatment, the 3-week-old seedlings were transferred into Hoagland medium supplemented with 100 μM ABA or placed in a petri dish on a laboratory bench, respectively. Then the samples were collected at indicated time point, and were frozen immediately by liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using a Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China, No. SK8631) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 1 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using a PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan, Cat#RR047A). For qPCR, a total volume of 10 μL reaction mixture was used containing 5 μL of 2 × SYBR Green Master Mix (BioRad, United States), 0.5 μL of 5 × diluted cDNA, 0.25 μL of each primer, and 4 μL of ddH2O. Amplification was performed using a CFX ConnectTM system (Bio-rad, United States). The amplification program consisted of one cycle of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s. The fluorescent product was detected at the third step of each cycle. The expression level of each gene was calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All analyses were repeated three times using biological replicates. The gene BnaGAPDH (BnaC05g12400D) was used as the internal control. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Yeast Two Hybrid

The yeast Gal4 system was employed for two-hybrid analysis of BnaRGAs and BnaA10.ABF2 protein interactions following the yeast transformation handbook (Yeast Transformation System 2; Clontech, United States). In brief, a single colony of yeast AH109 was incubated at 30°C overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in 25 mL ddH2O. Then the cell pellets were dissolved into 1.5-mL sterile 1 × Tris/LiAc solution to make the competent cells. For the yeast two-hybrid assay, the bait (0.5 μg) and/or prey (0.5 μg) plasmids with 0.1 mg of carrier DNA were co-transformed into the yeast-competent cells using polyethylene glycol/LiAc solution. After incubation at 30°C for 30 min, 70 μL DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) was added and incubation continued at 42°C for 15 min. The cells were centrifuged and washed using ddH2O. The presence of transgenes in yeast cells was confirmed by growing these cells on plates containing solid synthetic defined (SD) medium lacking Leu and Trp (SD/−2). To assess protein–protein interactions, transformed yeast cells were re-suspended in ddH2O to an optical density at OD600 of 1.0. Samples (5 μL) of suspended yeast cells were spread on plates containing SD medium lacking Ade, His, Leu, and Trp (SD/−4). To detect protein–protein interactions, plates were examined after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. For each experiment, a total of 10 clones were selected and tested.

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation

The BiFC assay was performed as previously described (Koo et al., 2017). In brief, the Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101) cells containing the desired constructs were injected into the 4- to 5-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves with the buffer (10 mM MES, pH = 5.7, 10 mM MgCl2, and 150 μM acetosyringone). The final concentrations of the bacteria were adjusted to an OD600 = 0.2 for each construct. The transiently transformed leaves were analyzed at 48 h after injection. The YFP fluorescence (excitation/emission wavelength: 514 nm/527 nm) was observed under a fluorescence microscope (SPX8, Leica).

Dual-Luciferase Assay

Dual-luciferase assays were performed by using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, United States). All reagents were prepared as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, the agrobacteria harboring the reporter and effector vectors were injected into the tobacco leaves. After 3 days, leaf disks in a diameter of 2 cm were harvested and ground, and dissolved into 100 μL of Passive Lysis Buffer. After 30 s, a 50 μL aliquot was used for luminescence measurements with the SPARK® MULTIMODE MICROPLATE (TECAN, Swiss). The following steps were used for luminescence measurements: 50 μL of the firefly luciferase reagent (LARII) was added to the test sample, with a 10 s equilibration time and measurement of luminescence with a 10 s integration time, followed by addition of 50 μl of the REN reagent and firefly quenching (Stop and GlowTM buffer), 10 s equilibration time, and measurement of luminescence with a 10 s integration time. The data are represented as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity (Fluc/Rluc). Each data point consisted of at least three biological replicates, and 10 repeats were performed for each assay.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The protein sequences were obtained from the website2 (Jin et al., 2017). The sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega.3 An unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA74 (Kumar et al., 2016) with the neighbor-joining statistical method and bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed to determine significant differences between genotypes, using Duncan’s multiple range tests in the ANOVA program of SPSS (IBM SPSS 22). at P values <0.05 or <0.01.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Brassica napus Genome database (https://plants.ensembl.org/Brassica_napus/Info/Index) under the following accession numbers: BnaA10.ABF2 (BnaA10g28780D), BnaC9.RAB18 (BnaC09g08130D), BnaRD29A (BnaC03g15510D), BnaRD29B (BnaA03g12660D), BnaA9.RGA (BnaA09g18700D), BnaC7.RGA (BnaC07g20900D), BnaA6.RGA (BnaA06g34810D), BnaC9.RGA (BnaC09g52270D), BnaC6.ABF2 (BnaC06g00420D), BnaABA1 (BnaA09g07610D), BnaABA2 (BnaC06g41140D), BnaGID1a (BnaA05g32040D), BnaGID1c (BnaA09g20650D), BnaSLY1 (BnaA01g13690D), BnaSLY2 (BnaC02g38380D), BnaGAPDH (BnaC05g12400D).

Author Contributions

CD and JW designed the research. JW, ZD, GY, and ZW performed the experiments. KL, LG, JT, JS, BY, TF, and CM provided lab support. CD, JW, and GY analyzed the data. CD, CK, JW, and ZD wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100803) to CM and the Natural Key Research Program of China (No. 202018ZX08020001) to CD. We thank Dr. Lesley Benyon, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00577/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.agdia.com

- ^ http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php

- ^ http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo

- ^ http://www.megasoftware.net/

References

Bai, M. Y., Shang, J. X., Oh, E., Fan, M., Bai, Y., Zentella, R., et al. (2012). Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 14, 810–817. doi: 10.1038/ncb2546

Chalhoub, B., Denoeud, F., Liu, S., Parkin, I. A., Tang, H., Wang, X., et al. (2014). Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435

Chaves, M., Maroco, J., and Pereira, J. (2003). Understanding plant responses to drought - From genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 30, 239–264.

Chen, K., Li, G. J., Bressan, R. A., Song, C. P., Zhu, J. K., and Zhao, Y. (2020). Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol 62, 25–54. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12899

Colebrook, E. H., Thomas, S. G., Phillips, A. L., and Hedden, P. (2014). The role of gibberellin signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 67–75. doi: 10.1242/jeb.089938

Dalal, M., Tayal, D., Chinnusamy, V., and Bansal, K. C. (2009). Abiotic stress and ABA-inducible Group 4 LEA from Brassica napus plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. J. Biotechnol. 139, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.09.014

de Lucas, M., Daviere, J. M., Rodriguez-Falcon, M., Pontin, M., Iglesias-Pedraz, J. M., Lorrain, S., et al. (2008). A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451, 480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06520

Desikan, R., Griffiths, R., Hancock, J., and Neill, S. (2002). A new role for an old enzyme: nitrate reductase-mediated nitric oxide generation is required for abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16314–16318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252461999

Ding, Y., Avramova, Z., and Fromm, M. (2011). The Arabidopsis trithorax-like factor ATX1 functions in dehydration stress responses via ABA-dependent and ABA-independent pathways. Plant J. 66, 735–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04534.x

Fleet, C. M., and Sun, T. P. (2005). A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.015

Fujita, Y., Fujita, M., Satoh, R., Maruyama, K., Parvez, M. M., Seki, M., et al. (2005). AREB1 is a transcription activator of novel ABRE-dependent ABA signaling that enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 3470–3488. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035659

Good, A. G., and Zaplachinski, S. T. (1994). The effects of drought stress on free amino acid accumulation and protein synthesis in Brassica napus. Physiol. Plant. 90, 9–14.

Hirano, K., Kouketu, E., Katoh, H., Aya, K., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., and Matsuoka, M. (2012). The suppressive function of the rice DELLA protein SLR1 is dependent on its transcriptional activation activity. Plant J. 71, 443–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05000.x

Hirsch, S., and Oldroyd, G. E. (2009). GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 698–700. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.8.9176

Hossain, M. A., Cho, J. I., Han, M., Ahn, C. H., Jeon, J. S., An, G., et al. (2010). The ABRE-binding bZIP transcription factor OsABF2 is a positive regulator of abiotic stress and ABA signaling in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.05.008

Hou, X., Lee, L. Y., Xia, K., Yan, Y., and Yu, H. (2010). DELLAs modulate jasmonate signaling via competitive binding to JAZs. Dev. Cell. 19, 884–894. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.024

Illouz-Eliaz, N., Ramon, U., Shohat, H., Blum, S., Livne, S., Mendelson, D., et al. (2019). Multiple gibberellin receptors contribute to phenotypic stability under changing environments. Plant Cell 31, 1506–1519. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00235

Jin, J., Tian, F., Yang, D. C., Meng, Y. Q., Kong, L., Luo, J., et al. (2017). PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1040–D1045. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw982

Kilian, J., Whitehead, D., Horak, J., Wanke, D., Weinl, S., Batistic, O., et al. (2007). The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 50, 347–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03052.x

Koo, J. C., Lee, I. C., Dai, C., Lee, Y., Cho, H. K., Kim, Y., et al. (2017). The protein trio RPK1-CaM4-RbohF mediates transient superoxide production to trigger age-dependent cell death in Arabidopsis. Cell Rep. 21, 3373–3380. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.077

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Lee, I. C., Hong, S. W., Whang, S. S., Lim, P. O., Nam, H. G., and Koo, J. C. (2011). Age-dependent action of an ABA-inducible receptor kinase, RPK1, as a positive regulator of senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 651–662. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr026

Li, F., Wu, X., Tsang, E., and Cutler, A. J. (2005). Transcriptional profiling of imbibed Brassica napus seed. Genomics 86, 718–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.07.006

Li, X. Y., Liu, X., Yao, Y., Li, Y. H., Liu, S., He, C. Y., et al. (2013). Overexpression of Arachis hypogaea AREB1 gene enhances drought tolerance by modulating ROS scavenging and maintaining endogenous ABA content. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 12827–12842. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612827

Lim, S., Park, J., Lee, N., Jeong, J., Toh, S., Watanabe, A., et al. (2013). ABA-insensitive3, ABA-insensitive5, and DELLAs Interact to activate the expression of SOMNUS and other high-temperature-inducible genes in imbibed seeds in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 4863–4878. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.118604

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Ma, Y., Szostkiewicz, I., Korte, A., Moes, D., Yang, Y., Christmann, A., et al. (2009). Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324, 1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1172408

Magome, H., Yamaguchi, S., Hanada, A., Kamiya, Y., and Oda, K. (2008). The DDF1 transcriptional activator upregulates expression of a gibberellin-deactivating gene, GA2ox7, under high-salinity stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 56, 613–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03627.x

McAdam, S. A. M., and Brodribb, T. J. (2016). Linking turgor with ABA biosynthesis: implications for stomatal responses to vapor pressure deficit across land plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 2008–2016. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00380

Müller, T., Lentzsch, P., and Müller, M. E. H. (2012). Carbohydrate dynamics in leaves of rapeseed (Brassica napus) under drought. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 198, 207–217.

Mustilli, A. C., Merlot, S., Vavasseur, A., Fenzi, F., and Giraudat, J. (2002). Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell 14, 3089–3099. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007906

Nakamura, H., Xue, Y. L., Miyakawa, T., Hou, F., Qin, H. M., Fukui, K., et al. (2013). Molecular mechanism of strigolactone perception by DWARF14. Nat. Commun. 4:2613. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3613

Nelissen, H., Sun, X.-H., Rymen, B., Jikumaru, Y., Kojima, M., Takebayashi, Y., et al. (2018). The reduction in maize leaf growth under mild drought affects the transition between cell division and cell expansion and cannot be restored by elevated gibberellic acid levels. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 615–627. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12801

Nir, I., Moshelion, M., and Weiss, D. (2014). The Arabidopsis gibberellin methyl transferase 1 suppresses gibberellin activity, reduces whole-plant transpiration and promotes drought tolerance in transgenic tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 113–123. doi: 10.1111/pce.12135

Nir, I., Shohat, H., Panizel, I., Olszewski, N., Aharoni, A., and Weiss, D. (2017). The tomato DELLA protein PROCERA acts in guard cells to promote stomatal closure. Plant Cell 29, 3186–3197. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00542

Park, S. Y., Fung, P., Nishimura, N., Jensen, D. R., Fujii, H., Zhao, Y., et al. (2009). Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324, 1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1173041

Piskurewicz, U., Jikumaru, Y., Kinoshita, N., Nambara, E., Kamiya, Y., and Lopez-Molina, L. (2008). The gibberellic acid signaling repressor RGL2 inhibits Arabidopsis seed germination by stimulating abscisic acid synthesis and ABI5 activity. Plant Cell 20, 2729–2745. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061515

Qaderi, M. M., Kurepin, L. V., and Reid, D. M. (2006). Growth and physiological responses of canola (Brassica napus) to three components of global climate change: temperature, carbon dioxide and drought. Physiol. Plant. 128, 710–721.

Rodriguez-Leal, D., Lemmon, Z. H., Man, J., Bartlett, M. E., and Lippman, Z. B. (2017). Engineering quantitative trait variation for crop improvement by genome editing. Cell 171, 470.e8–480.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.030

Soon, F. F., Ng, L. M., Zhou, X. E., West, G. M., Kovach, A., Tan, M. H., et al. (2012). Molecular mimicry regulates ABA signaling by SnRK2 kinases and PP2C phosphatases. Science 335, 85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1215106

Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Nakajima, M., Katoh, E., Ohmiya, H., Asano, K., Saji, S., et al. (2007). Molecular interactions of a soluble gibberellin receptor, GID1, with a rice DELLA protein, SLR1, and gibberellin. Plant Cell 19, 2140–2155. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043729

Van De Velde, K., Ruelens, P., Geuten, K., Rohde, A., and Van Der Straeten, D. (2017). Exploiting DELLA signaling in cereals. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 880–893. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.07.010

Vishal, B., and Kumar, P. P. (2018). Regulation of seed germination and abiotic stresses by gibberellins and abscisic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 9:838. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00838

Wang, Z., Liu, L., Cheng, C., Ren, Z., Xu, S., and Li, X. (2020). GAI functions in the plant response to dehydration stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:819. doi: 10.3390/ijms21030819

Xiong, L., Schumaker, K. S., and Zhu, J. K. (2002). Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress. Plant Cell 14(Suppl.), S165–S183. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000596

Yang, H., Wu, J. J., Tang, T., Liu, K. D., and Dai, C. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing efficiently creates specific mutations at multiple loci using one sgRNA in Brassica napus. Sci. Rep. 7:7489. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23161-4

Yoshida, H., Hirano, K., Sato, T., Mitsuda, N., Nomoto, M., Maeo, K., et al. (2014). DELLA protein functions as a transcriptional activator through the DNA binding of the indeterminate domain family proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 7861–7866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321669111

Zentella, R., Zhang, Z. L., Park, M., Thomas, S. G., Endo, A., Murase, K., et al. (2007). Global analysis of della direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999

Zhang, D., Jing, Y., Jiang, Z., and Lin, R. (2014). The chromatin-remodeling factor PICKLE integrates brassinosteroid and gibberellin signaling during skotomorphogenic growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2472–2485. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121848

Zhao, B., Li, H., Li, J., Wang, B., Dai, C., Wang, J., et al. (2017). Brassica napus DS-3, encoding a DELLA protein, negatively regulates stem elongation through gibberellin signaling pathway. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130, 727–741. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2846-4

Zhao, B. Y., Hu, Y. F., Li, J. J., Yao, X., and Liu, K. D. (2016). BnaABF2, a bZIP transcription factor from rapeseed (Brassica napus L.), enhances drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Bot. Stud. 57:12. doi: 10.1186/s40529-016-0127-9

Zhu, J. K. (2002). Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329

Zhu, J. K. (2016). Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167, 313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029

Zhu, M., Monroe, J. G., Suhail, Y., Villiers, F., Mullen, J., Pater, D., et al. (2016). Molecular and systems approaches towards drought-tolerant canola crops. New Phytol. 210, 1169–1189. doi: 10.1111/nph.13866

Keywords: GA, DELLA protein, BnaRGA, ABA, BnaA10.ABF2, Brassica napus

Citation: Wu J, Yan G, Duan Z, Wang Z, Kang C, Guo L, Liu K, Tu J, Shen J, Yi B, Fu T, Li X, Ma C and Dai C (2020) Roles of the Brassica napus DELLA Protein BnaA6.RGA, in Modulating Drought Tolerance by Interacting With the ABA Signaling Component BnaA10.ABF2. Front. Plant Sci. 11:577. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00577

Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 17 April 2020;

Published: 14 May 2020.

Edited by:

László Szabados, Biological Research Centre, Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA), HungaryReviewed by:

Salomé Prat, Centro Nacional de Biotecnología, SpainAgata Cieśla, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland

Copyright © 2020 Wu, Yan, Duan, Wang, Kang, Guo, Liu, Tu, Shen, Yi, Fu, Li, Ma and Dai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chaozhi Ma, eXVhbmJlYXV0eUBtYWlsLmh6YXUuZWR1LmNu; Cheng Dai, Y2RhaUBtYWlsLmh6YXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jiajing Wu1†

Jiajing Wu1† Chunying Kang

Chunying Kang Liang Guo

Liang Guo Kede Liu

Kede Liu Jinxing Tu

Jinxing Tu Jinxiong Shen

Jinxiong Shen Bin Yi

Bin Yi Xia Li

Xia Li Chaozhi Ma

Chaozhi Ma Cheng Dai

Cheng Dai