95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 28 February 2020

Sec. Plant Breeding

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00189

This article is part of the Research Topic Wild Plants as Source of New Crops View all 23 articles

Juan P. Renzi1,2*

Juan P. Renzi1,2* Guillermo R. Chantre2,3

Guillermo R. Chantre2,3 Petr Smýkal4

Petr Smýkal4 Alejandro D. Presotto2,3

Alejandro D. Presotto2,3 Luciano Zubiaga1

Luciano Zubiaga1 Antonio F. Garayalde5

Antonio F. Garayalde5 Miguel A. Cantamutto1,2,3

Miguel A. Cantamutto1,2,3Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa ssp. villosa Roth) is native of Europe and Western Asia and it is the second most cultivated vetch worldwide. Hairy vetch is used as forage species in semiarid environments and as a legume cover crop in sub-humid and humid regions. Being an incompletely domesticated species, hairy vetch can form spontaneous populations in a new environment. These populations might contain novel and adaptive traits valuable for breeding. Niche occupancy based on geographic occurrence and environmental data of naturalized populations in central Argentina showed that these populations were distributed mainly on disturbed areas with coarse soil texture and alkaline-type soils. Low rainfall and warm temperatures during pre- and post-seed dispersal explained the potential distribution under sub-humid and semiarid conditions from Pampa and Espinal ecoregions. Conversely, local adaptation along environmental gradients did not drive the divergence among recently established Argentinian (AR) populations. The highest genetic diversity revealed by microsatellite analysis was observed within accessions (72%) while no clear separation was detected between AR and European (EU) genotypes, although naturalized AR populations showed strong differentiation with the wild EU accessions. Common garden experiments were conducted in 2014–16 in order to evaluate populations’ germination, flowering, and biomass traits. European cultivars were characterized by low physical seed dormancy (PY), while naturalized AR accessions showed higher winter biomass production. Detected variation in the quantitative assessment of populations could be useful for selection in breeding for traits that convey favorable functions within specific contexts.

The Vicia genus, of the Fabaceae family, includes several winter annual legumes, generically grouped as “vetches.” Within this complex, Vicia villosa ssp. villosa Roth, commonly known as hairy vetch (HV), is a relevant member. It is native in Europe and West Asia, being introduced as a crop or weed worldwide to temperate climate regions. Hairy vetch is considered a cosmopolitan species due to its high capacity to naturalize under different conditions. It is present in the flora of both South and North Americas, including Argentina (Van de Wouw et al., 2001; Bryant and Hughes, 2011).

Hairy vetch is the second most important vetch in agricultural systems worldwide (Francis et al., 1999). Generally, it is grown for forage, consumed under direct or indirect grazing, or for green manure. In conservation agriculture, the use of HV as cover crop is increasing. Hairy vetch displays high tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Francis et al., 1999). It is one of the recommended cover crop in organic or conservation farming, mainly because it enhances soil nitrogen content by biological fixation (Vanzolini, 2011). Due to its valuable traits, HV could help to improve soil structure, reduce soil erosion, and enhance weed suppression (Clark, 2007; Wayman et al., 2016; Frasier et al., 2017). Typically, HV produces between 2.6 and 6.2 ton ha−1 of above-ground dry biomass (Lawson et al., 2015; Mirsky et al., 2017; Ackroyd et al., 2019).

Hairy vetch shows the capacity to form spontaneous populations in ruderal habitats of cultivated areas (Aarssen et al., 1986; Renzi and Cantamutto, 2013). Under natural conditions, the ability to regenerate populations from the soil seed bank is associated with primary combinational seed dormancy (i.e., physical plus physiological dormancy, PY+PD) (Renzi et al., 2014). These naturalized populations can be useful as a genetic resource for breeding. However, despite the high potential agronomic value, HV is an incompletely domesticated species and only a few improved varieties exist. Likewise, HV cover crops are often unreliable in terms of establishment, performance and biomass production (Wilke and Snapp, 2008; Aapresid, 2018). Altogether these drawbacks frequently limit HV adoption by farmers (Maul et al., 2011). Studies concerning geographic distribution and climatic requirements of this species are scarce (Aarssen et al., 1986). The study of the ecological niches of natural HV populations would improve our understanding of its potential adaptation to different environmental factors.

The most important breeding goals of HV include high early vigor, high winter, and spring biomass production and low level of seed dormancy (mainly due to the physical component of primary dormancy). Rapid growth under low temperatures is especially important when HV is used to produce biomass at the end of winter (i.e., cover crop). The time-window for HV growth control (by desiccation or mechanical methods) during early spring, depends on the planting date of the subsequent summer crop. As the growth rate of HV accelerates with the spring advance the adjustment of the control intervention is critical to determine the cover crop performance. Moreover, HV spring biomass production largely determines the amount of nitrogen supplied to subsequent cash crops (Vanzolini, 2011). An additional challenge of HV is seed dormancy control, which can lead to incomplete emergence after seeding (Jacobsen et al., 2010; Maul et al., 2011). On the contrary, in agroecosystems of semiarid regions, HV natural reseeding capacity is a desirable trait reducing establishment costs (Renzi et al., 2017; Renzi et al., 2019), especially when used as forage crop by livestock farmers.

HV was introduced in Argentina more than a century ago (Manganaro, 1919). Since then, several naturalized populations have been established in ruderal habitats surrounding agricultural areas. These populations are considered an unexplored genetic resource for breeding. However, to confirm their potential value as a genetic resource, it is imperative to collect and characterize such material, by comparison, to currently registered cultivated accessions.

The objectives of this study are: i) to describe the natural habitats of naturalized HV populations from Argentina, ii) to assess the phenotypic variability of naturalized populations compared with a set of 41 introduced accessions of HV (including wild and cultivars), and iii) to study the genetic structure using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers.

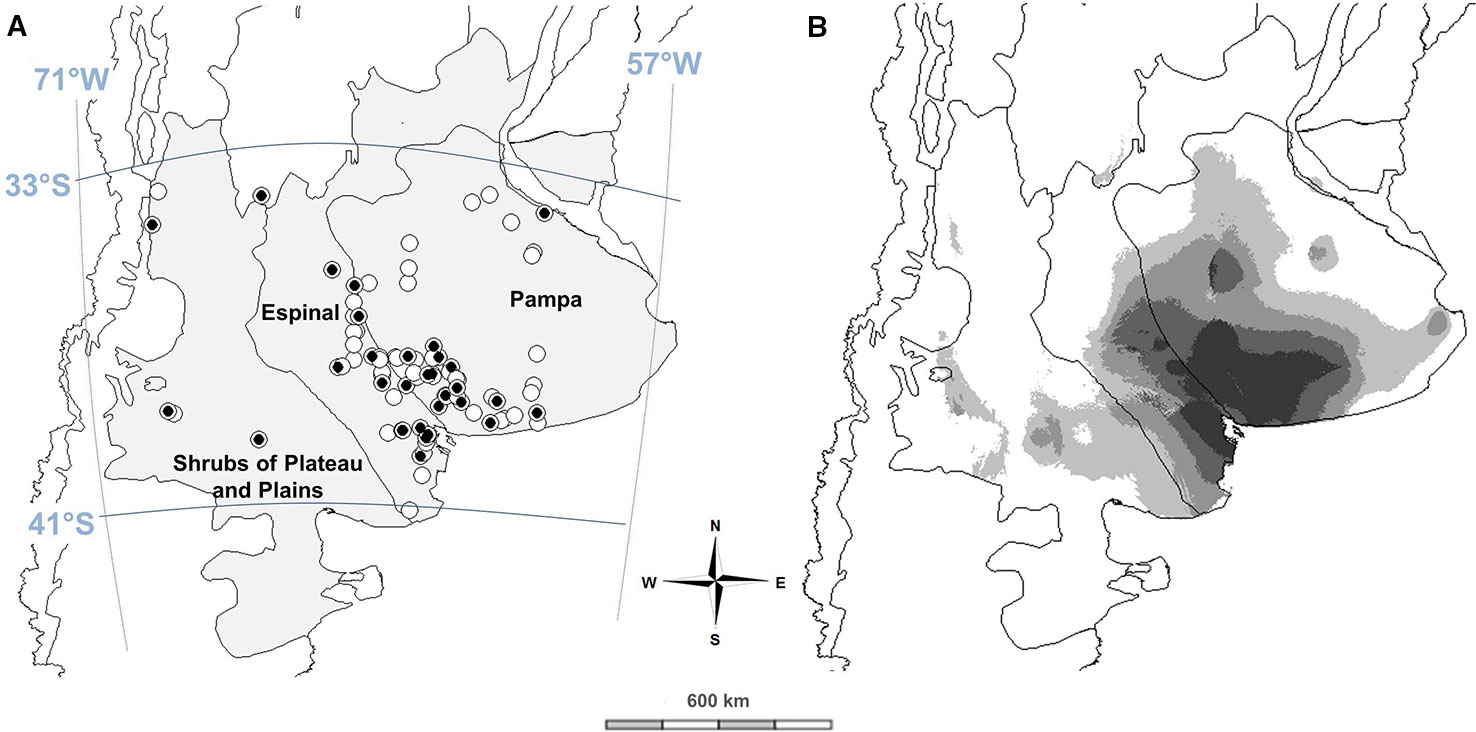

The study area comprised nine provinces: Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Río Negro, Neuquén, Mendoza, Córdoba, San Luis, Santa Fe, and Entre Ríos, belonging to three eco-regions: Pampa, Espinal, and Shrubs of Plateau and Plains (Figure 1A). Three exploration trips were accomplished during December 2013-2015, covering a total of 21.400 km. The survey on HV populations was based on specialized systematic bibliography (Burkart, 1952), and voucher specimens deposited at Instituto de Botánica Darwinion (http://www2.darwin.edu.ar) and Museo de La Plata (http://www.museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar). To be considered, studied HV populations must be observed for at least two different years at the same locality, and they must contain more than 50 individuals. Recorded information of collection site consisted of i) ecological region, ii) latitude, longitude and altitude, iii) environment (soil and climate) and plant community (dominance of co-occurring plant species) characterized by family, iv) life cycle and origin (Marzocca, 1994). Global positioning system (GPS) coordinates of 63 naturalized populations were recorded (Table S1).

Figure 1 Spatial distribution and seed collection sites (circles) of naturalized hairy vetch populations in Argentina. Gray area shows studied regions and black circles indicate the populations used for phenotypic characterization in the common garden (A). Predicted potential distribution of HV populations in central Argentina based on climatic niche modeling results (B). Lighter colors correspond to lower probabilities of occurrence while darker colors correspond to higher probabilities of occurrence (created with MaxEnt 3.4.1k).

The WorldClim (http://worldclim.org) version 2.0 database was used to extract information about the climate (period 1970–2000). Data were extracted using DIVA-GIS software from ESRI grids with a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds (~ 1 km) in the WGS-84 (EPSG: 4326). Bioclimatic variables (BIO1–BIO19) were derived from monthly temperature and rainfall values (Fick and Hijmans, 2017). To avoid over-parameterization, 10 bioclimatic variables were selected to represent annual trends and extreme conditions of temperature and precipitation: annual mean temperature (BIO1), maximum temperature of the warmest month (BIO5), minimum temperature of the coldest month (BIO6), mean temperature of warmest quarter (BIO10), mean temperature of coldest quarter (BIO11), annual precipitation (BIO12), precipitation of the wettest month (BIO13), precipitation of the driest month (BIO14), precipitation of wettest quarter (BIO16), and precipitation of driest quarter (BIO17) (Hijmans et al., 2005). In addition to the bioclimatic variables, edaphic variables related to soil texture, pH, and bulk density were obtained from soil databases (FAO/IIASA/ISSCAS/JRC, 2012) using WGS84 and spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds. For details, including basic descriptive statistics of each environmental variable see Table S1.

Soil samples (at depth of 0–15 cm) were collected at each site to assess the data obtained from soil databases. Soil samples were air-dried and sieved to < 2 mm. pH was measured using a glass electrode pH-meter (soil: water, 1:2.5). Texture analysis (% clay, silt, sand) on HCl and H2O2 treated and chemically [0.05 M (NaPO3)6 and 0.15 M Na2CO3] dispersed samples was carried out by a combination of sieving and pipette methods (Cantamutto et al., 2008; Santos et al., 2017). Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient was performed between soil databases and samples using the InfoStat software (Di Rienzo et al., 2013).

Ecological niche models were constructed using the geographic locations of HV naturalized populations. Maxent (version 279 3.4.1, Phillips et al., 2018) at default conditions, a maximum-entropy based machine learning method was used for modeling purposes. Maxent showed better performance than other methods when samples sizes are small (Hernandez et al., 2006) and it estimates the potential niche instead of the realized distribution of the modeled entity (Phillips et al., 2006; Hradilová et al., 2019). As environmental predictors, bioclimatic and soil variables at a resolution of 2.5 arc minutes were used. Logistic output with suitability values ranging from 0 (unsuitable habitat) to 1 (optimal habitat) was used. Occurrence points (75%) were used to calibrate the model. The remaining (25%) occurrence points were used for model evaluation. Model strength was quantified using the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operator generated within Maxent (Zhu et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2018).

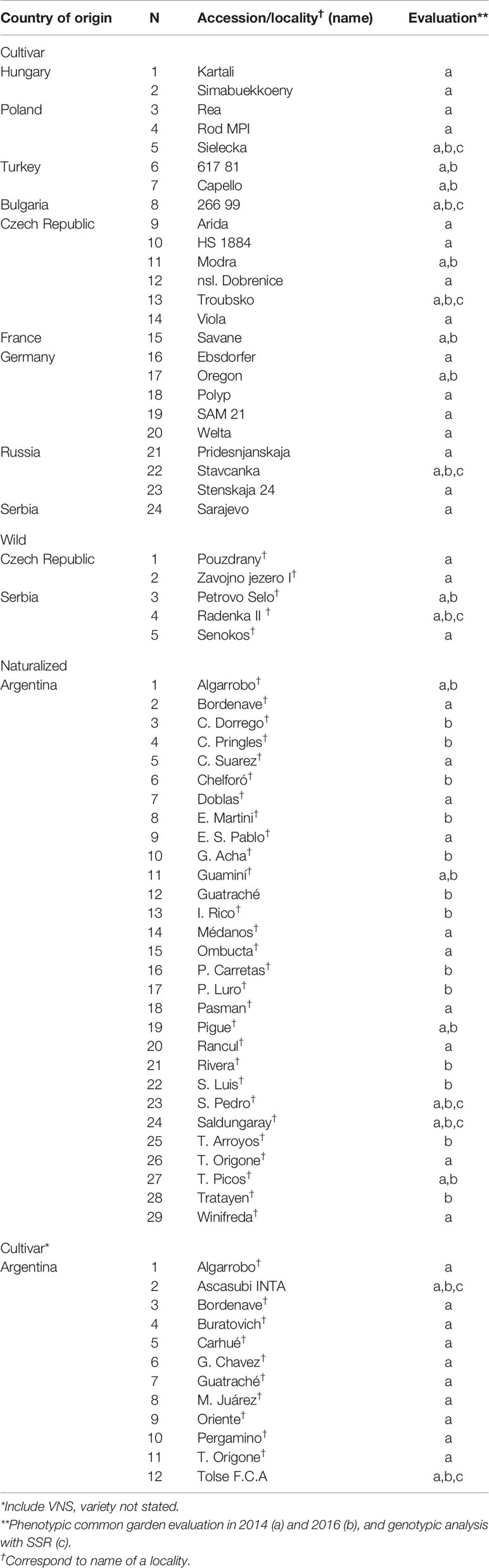

In order to determine the biodiversity of studied naturalized populations (Figure 1A, Table S1), we compared accessions originating from Argentina (AR) and Europe (EU). Twenty-nine naturalized populations were evaluated in a common garden (2014 and/or 2016) experiment (Table 1). They were selected based on the amount of available collected seed stock (> 30 g) and wide distribution (Figure 1A). Cultivated germplasm from AR consisted of 10 varieties (landraces) maintained by farmers (Table 1) and two registered cultivars (Tolse F.C.A and Ascasubi INTA) (www.inase.gov.ar).

Table 1 Country, improvement status (cultivar, wild, and naturalized), and name of hairy vetch accessions included in the phenotypic and genotypic studies.

Wild (n = 5) and cultivated germplasm (n = 24) of HV from EU was represented by 29 accessions (Table 1). Origin and accession name of each cultivar were provided by the Research Institute of Crop Production (CRI) of the Czech Republic (Table 1; for more information see https://grinczech.vurv.cz/gringlobal/search.aspx) (Renzi et al., 2016).

Plants (Table 1) were cultivated at the Experimental Agricultural Station (EEA) of Hilario Ascasubi (Buenos Aires, Argentina; 62°37′W, 39°23′S) during 2014 and 2016 growing seasons. The predominant climate in this location is semiarid-temperate with 489 mm mean annual precipitation and 14.8°C mean annual temperature (EEA H. Ascasubi, 1966–2018). The soil was an entic haplustoll, sandy loam, slightly alkaline (pH ≈ 7.5), high in phosphorus (P) content (≈ 22 ppm P Bray & Kurtz) and low organic matter content (≈ 1.6%) at 20 cm (Renzi et al., 2016). Weather data from each year were registered at the nearby meteorological station (less than 500 m) (http://inta.gob.ar/documentos/informes-meteorologicos).

The accessions were arranged in row plots in a randomized complete block design, with three replications. Each experimental unit consisted of a row of 2.50 meters sown with 30 seeds on 10th April 2014 and 27th April 2016. Original collected seeds were used in 2014 and 2016 experiments. Seeds were inoculated with commercial inoculum (Rhizobium leguminosarum bv viciae) immediately before sowing (Deaker et al., 2004).

To determine the number of days from sowing to 50% flowering, the growing stage was recorded twice a week. After 50% flowering, leaf length (mm), leaflets per leaf, and the number of flowers per raceme were measured on 10 randomly selected individual stems in each plot. For foliar observations, the leaf of the third upper node of the stem and the basal leaflet of the leaf were chosen. Above-ground total dry matter was measured at end of winter (mid-September) and late spring (mid-December) by cutting plant shoots at ground level in a 0.50 m row in each plot. The biomass of each accession, in each year, was expressed in relation to the average biomass per year. Maturity was defined by the presence of 75% ripe pods, approximately at the beginning of summer. Seeds from mature pods were immediately harvested and threshed by hand, on 21st December 2014 and 26th December 2016, for physical (PY) testing. Moisture content at harvest was ≤ 14% (Renzi and Cantamutto, 2013).

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) considering a randomized complete block, between improvement status (EU Cultivar, Wild, AR Cultivar, Naturalized; Table 1) and between accessions for each improvement status, were performed using InfoStat software. Accessions and improvement status means were compared by Fisher’s least significant difference test. Correlations between quantitative traits were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Canonical variate analysis (CVA) was performed with all phenotypic traits based on Euclidean distance through InfoStat software.

After the harvest from the common garden experiment, seeds were cleaned and seed weight was estimated, in a sample of 100 seeds in 2014 (n = 1) or 50 seeds in 2016 (n = 3). PY seeds (i.e., “hard” or impermeable) were determined by an imbibition test performed at 20 ± 2°C for 3 days (Baskin and Baskin, 2014). Intact non-germinated seeds of each replication were placed on moist filter paper in Petri dishes and watered daily with tap water. Imbibed seeds showed a visible change in its size/volume ratio, and were easily distinguished from non-imbibed ones (Renzi et al., 2014). Seed viability of non-germinated seeds was assessed by slicing longitudinally with razor and immersion in a 0.5% (wt/vol) tetrazolium chloride (2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride) (Sigma-Aldrich) solution for 24 h at 30°C in the dark (ISTA, 2019). Seeds with pink or red-stained embryos were considered viable. The total number of viable seeds consisted of germinated plus stained one (Renzi et al., 2016).

For all accessions, PY break dynamics as a function of storage time (38 days) and temperature (20°C) under wet conditions were analyzed using the area under the curve (AUC) calculated by GraphPad Prism Software (GraphPad, San Diego, California, USA). Where AUC = 1 indicates seed without PY (Initial non-PY seeds = 100%) and AUC = 0 indicate PY seed (final non-PY seeds = 0%) (Renzi et al., 2016). Accessions were grouped by improvement status and further compared by Fisher’s least significant difference test using InfoStat software.

To assess relationships between phenotypic traits in 16 and 20 naturalized populations of Argentina (2014 and 2016) and both geographic and environmental distances, six matrices were prepared and examined using the Mantel test (Smouse et al., 1986). The physical distance between naturalized populations was estimated using geographic distance (GGD) for latitude (x)/longitude (y) values: (Peakall and Smouse, 2006; Garayalde et al., 2011). The geographic matrix contained pairwise geographical distances while phenotypic distance was calculated as Euclidean distances between populations. All environmental variables were standardized and were calculated using soil and climatic variables (“environmental”). The significance of the normalized Mantel coefficient was calculated using a two-tailed Monte Carlo permutation test with 1,000 permutations using InfoStat software.

Three representative naturalized populations (n = 3) were contrasted with AR cultivar (n = 2), EU cultivar (n=4), and wild accession (n = 1) (Table 1). Seeds were sown in a common garden at the Experimental Agricultural Station (EEA) of Hilario Ascasubi. Leaf material from 10 randomly selected plants from each accession was collected at the vegetative stage (August 2016). Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) method (Hoisington et al., 1994) from leaf tissue dried on silica gel.

The five most polymorphic SSR markers were chosen (Table S2) from set of 36 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers developed by Raveendar et al. (2015) for common vetch (Vicia sativa subsp. sativa) (Chung et al., 2013) and being applicable for HV genotyping analysis. Amplification reactions were performed in 17 μl volumes containing: 0.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), 1 mM MgCl2, 1.1 pmol of primers, 1 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 30 ng of genomic DNA template. The optimum annealing temperature was determined for each primer set: KF008505 (55°C), KF008507 (59°C), KF008512 (59°C), KF008526 (59°C), and KF008536 (60°C). Amplifications were initially checked on 1.5% agarose gels. PCR products were analyzed on 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, 1×TBE electrophoresis buffer at 60 W for 75 min and the bands were visualized by silver staining and scanned (modified from Tang et al., 2003 and Garayalde et al., 2011). The size of each SSR allele was estimated using a 100 bp molecular weight marker. Each DNA fragment was considered as an allele of a single co-dominant locus.

The amplified SSR loci were scored for 10 accessions. Homozygous and heterozygous genotypes were inferred from the band patterns and allele frequencies (pi) calculated accordingly. The absence of band (null allele) was scored as missing data. Mean expected heterozygosity values (He) and the percentage of polymorphic loci (P%) were calculated: , where pi is the frequency of the ith allele, Lp is the number of polymorphic loci, and LT is the total number of loci. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested using chi-squared test , where Oi is the observed number of individuals of the ith genotype, Ei is the expected number under equilibrium hypothesis, and K is the total number of genotypes. Degrees of freedom for the chi-squared test were calculated as d.f. = [Na(Na–1)]/2, where Na is the number of alleles at the locus (following Garayalde et al., 2011).

The calculation of genetic distances (GD) followed the method of Peakall et al. (1995) and Smouse and Peakall (1999). For the analysis of a SSR single-locus, the first step involves the calculation of the vector by additive genotype scoring convention per individuals. Subsequently, the squared distance (d2) between any two genotypes is one-half the Euclidean distance between their respective pair of vectors as follows: , where i and j are the genotypes and k is the scoring character. Squared distances range from 0, when individuals share the same alleles, to 4 when individuals are homozygous for different alleles. Genetic distance matrices for each locus were summed across loci under the assumption of independence. At population level, a ØPT (analogue of FST) obtained from analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used as an estimate of population genetic differentiation with SSR markers. Principal coordinate analyses (PCO) were performed on GD matrices. The correlation between genetic distance and phenotypic matrix was analyzed by the Mantel test (see Garayalde et al., 2011).

The individual pairwise GD matrices were subjected to AMOVA. Total genetic variation was partitioned into three levels: within and between accessions and between origin (AR and EU). Variation was summarized both as the proportion of the total variance and as Ø-statistics (Excoffier et al., 1992). Genetic variability measures, distance metrics, PCO analysis, correlation analysis, and AMOVA were analyzed using GenAlEx 6 (Peakall and Smouse, 2006).

Naturalized populations of hairy vetch were found in the three monitored regions (Figure 1A), corresponding to Pampa, Espinal, and Shrubs of Plateau and Plains. In the central temperate region of Argentina, annual rainfall varies from semi-arid to arid conditions with only 200 mm, to sub-humid and humid environments with approximately 1,000 mm. The vegetation changes in all three regions, from arid steppes in the west (Shrubs of Plateau and Plains) to grass steppes without woody species in the east (Pampa). The Espinal is an intermediate savannah, with grasses and scarce xeric trees, mainly of the Prosopis genus.

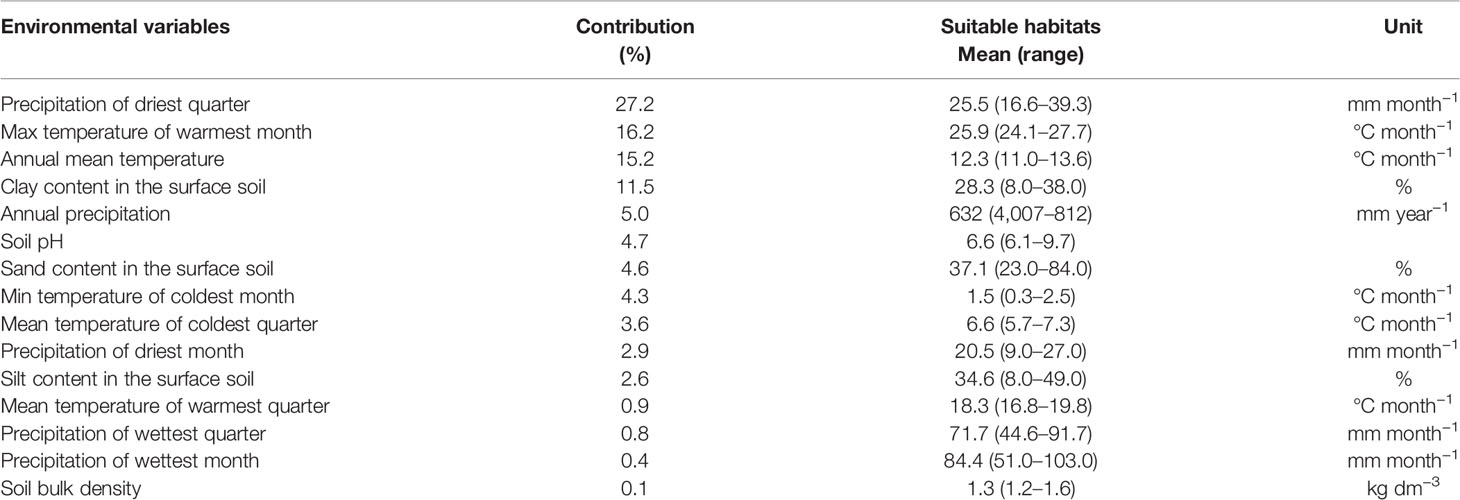

The proposed niche modeling explained most of the variation in HV geographical distribution. The area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) score of MaxEnt models, both training and test AUC values, were 0.957 and 0.956, respectively, indicating that most climatically suitable areas predicted by MaxEnt were highly correlated with the occurrence of natural HV populations. The distribution was significantly affected by precipitation amount of the driest quarter (BIO17), max temperature of the warmest month (BIO5), annual mean temperature (BIO1), and clay content in the soil surface (t_clay, Table 2). The main suitable habitats for HV are distributed in the southeast of Espinal and southwest of the Pampa region, characterized by sub-humid and semiarid temperate climates, with warm-dry summers and cold-wet winters (Figure 1B).

Table 2 Contribution (%) of the bioclimatic and soil variables in the MaxEnt models, and suitable habitats of naturalized hairy vetch populations from Argentina.

Plant communities associated with HV comprised of 63 species (Table S1). Most frequent species were cosmopolitan weeds, including Avena fatua, Cynodon dactylon, Sorghum halepense (Poaceae), Carduus sp., and Centaurea solstitialis (Asteraceae) and natural communities of the perennial pasture Festuca arundinacea (Poaceae). Table 3 presents the life cycles and origins of the 20 species frequently associated with naturalized HV populations in the explored region, considered as the dominant community species. Exotic species represent 85% of the co-occurring vegetation.

Registered rainfall in EEA Hilario Ascasubi during HV growing season (from April to December) was 50% higher in 2014 (498 mm) and 21% lower (264 mm) in 2016, compared to historical long-term means (331 mm). Mean daily air temperature values were slightly higher in 2014 (13.5°C) compared to 2016 (12.8°C) growing season. All AR accessions performed well, except for Tolse F.C.A in 2014. However, nine out of the twenty-four EU tested cultivars (nr. 1, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 and 19; Table 1) and two out of the five wild populations (1 and 2) did not produce pods during 2014.

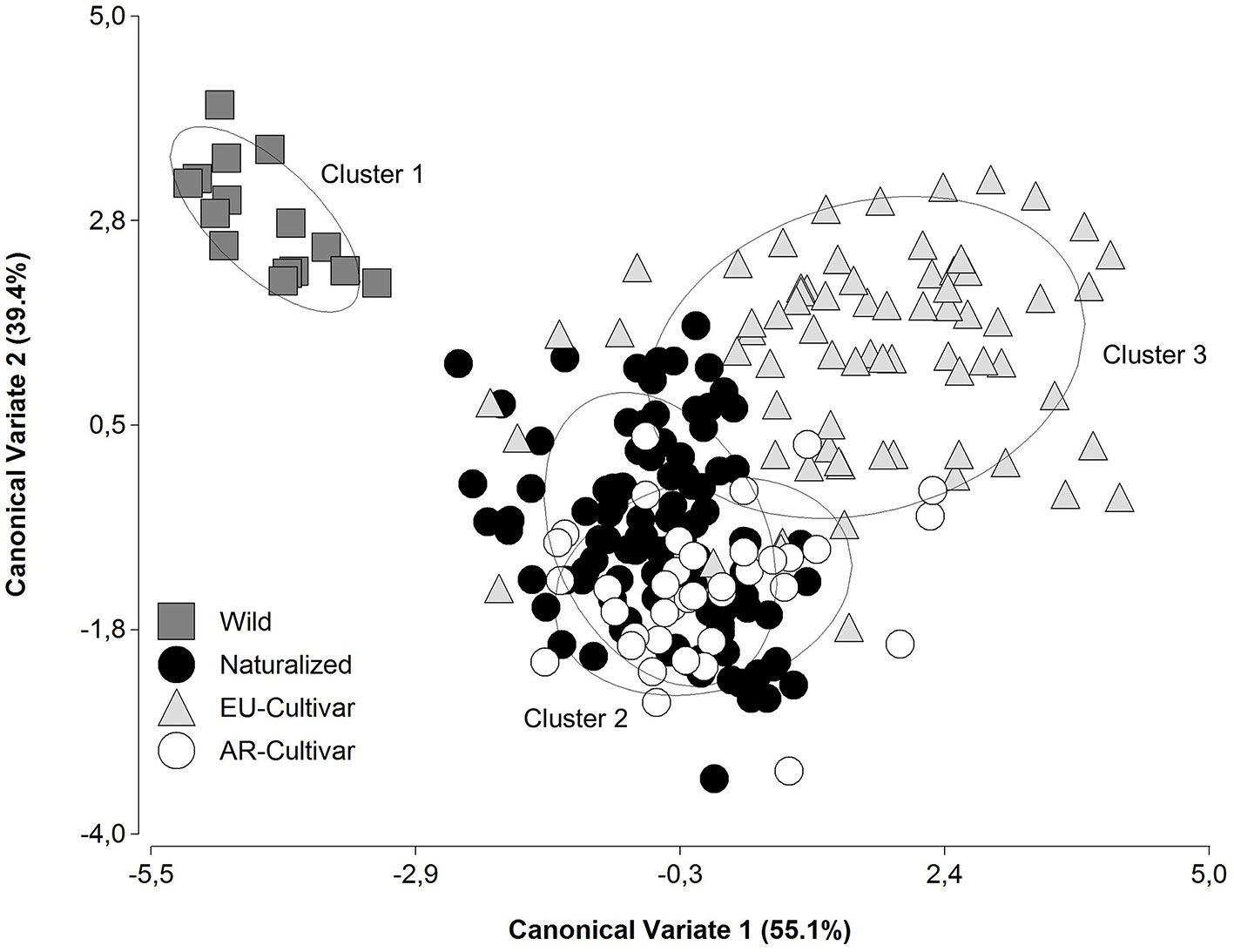

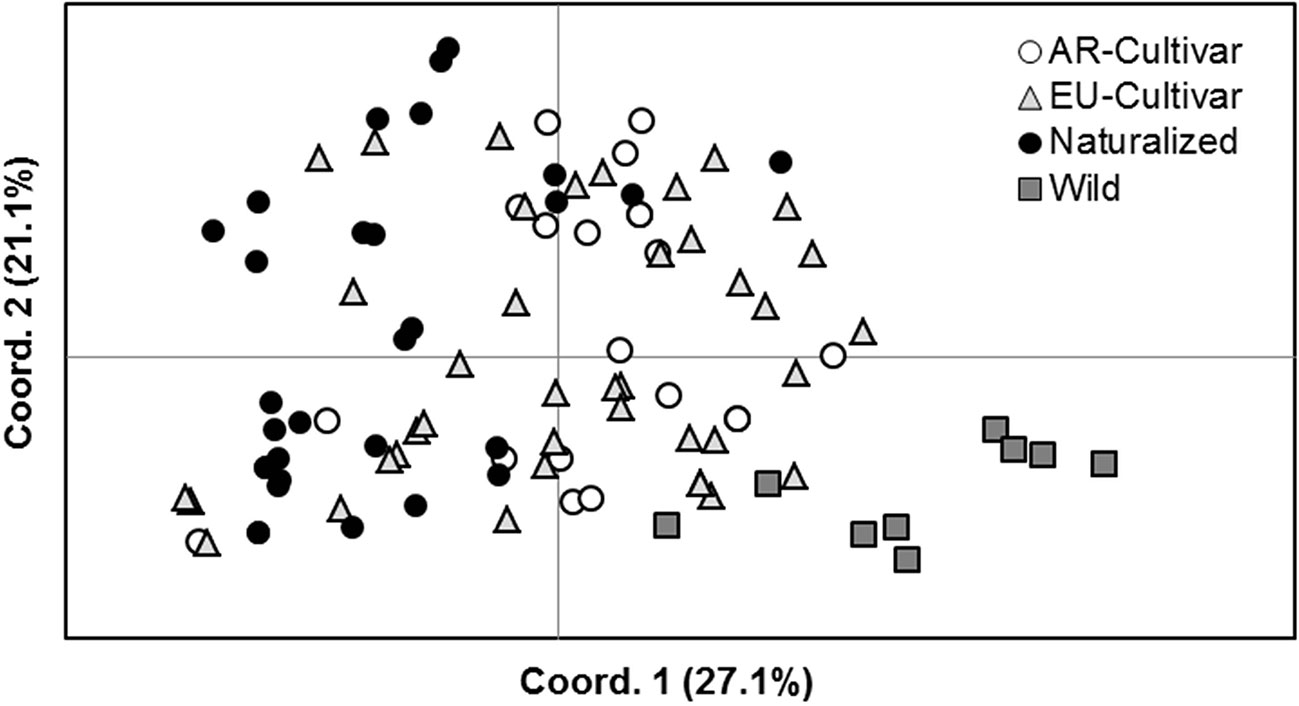

Using canonical discriminant analysis with the phenotypic traits, the accessions were grouped in three clusters (Figure 2). These corresponded to improvement status and origin. Cluster 1 consisted predominantly of wild populations, cluster 2 consisted accessions of AR origin, and in cluster 3 were EU cultivars.

Figure 2 Scatterplot of the four improvement status groupings on the two canonical discriminant functions based on phenotypic traits in a common garden during 2014 and 2016.

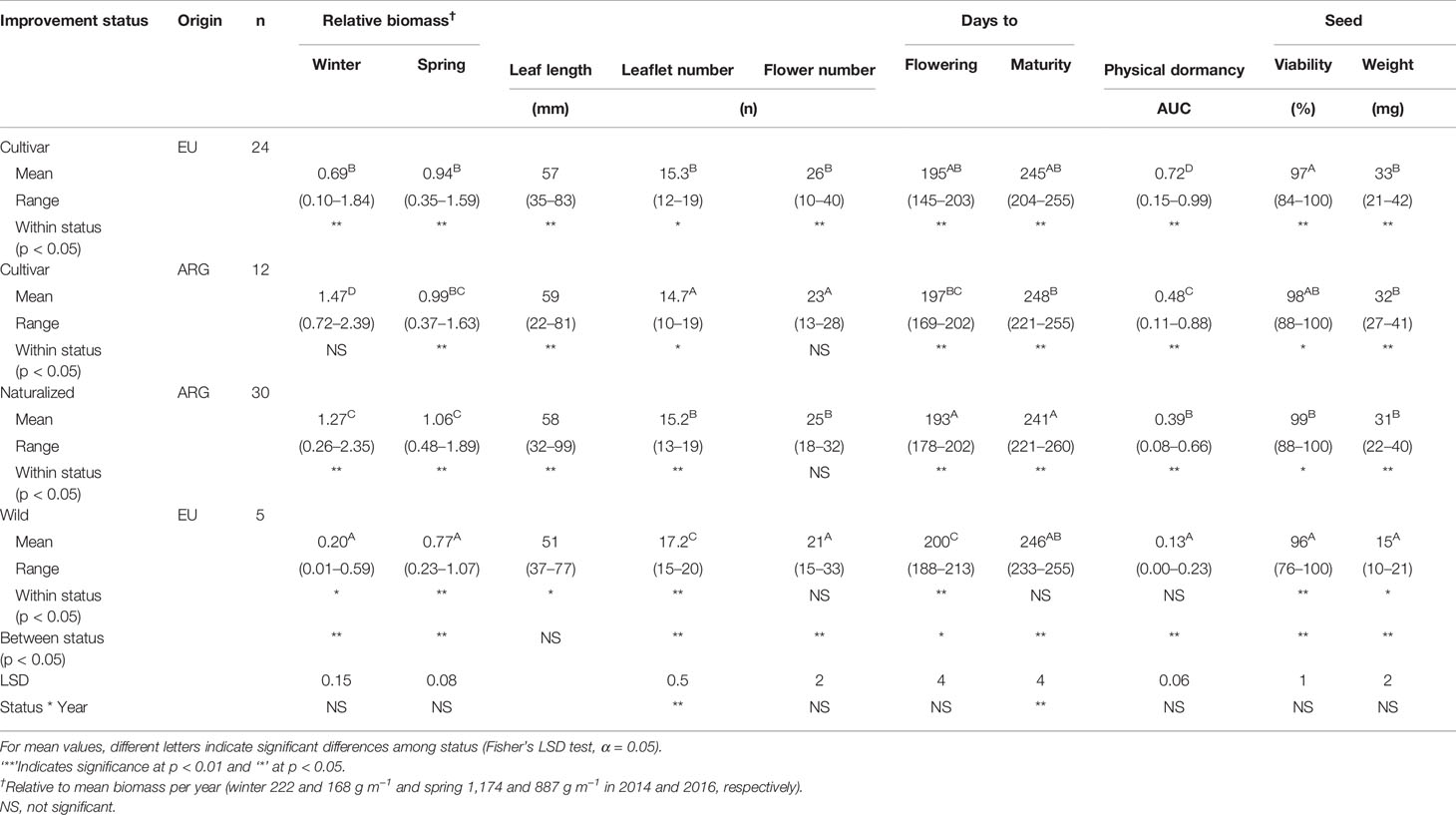

AR accessions showed higher winter biomass production compared to EU cultivars and wild genotypes (Table 4). Biomass in spring was less variable between improvement status. Over the total data set, HV winter biomass was negatively correlated to the number of leaflets per leaf (r = -0.20; P < 0.01), and the spring biomass was positively correlated with the leaf length (r = 0.74; P < 0.001). There was strong positive correlation between winter and spring biomass (r = 0.40; P < 0.001). Variations in the days to flowering among improvement status were narrow (≤ 7 days) but statistically significant within status (Table 4).

Table 4 Phenotypic variability of hairy vetch (HV) for each improvement status and origin (means and range) grown in a common garden during 2014 and 2016 in Experimental Agricultural Station (EEA) Hilario Ascasubi.

Seed viability was over 80% in all cases. The area under the curve (AUC), showing the following dormancy gradient rank: EU cultivars < AR cultivars < naturalized < wild genotype. No significant interaction between improvement status x year was found in the AUC (Table 4). Wild genotypes had a smaller seed weight (Table 4).

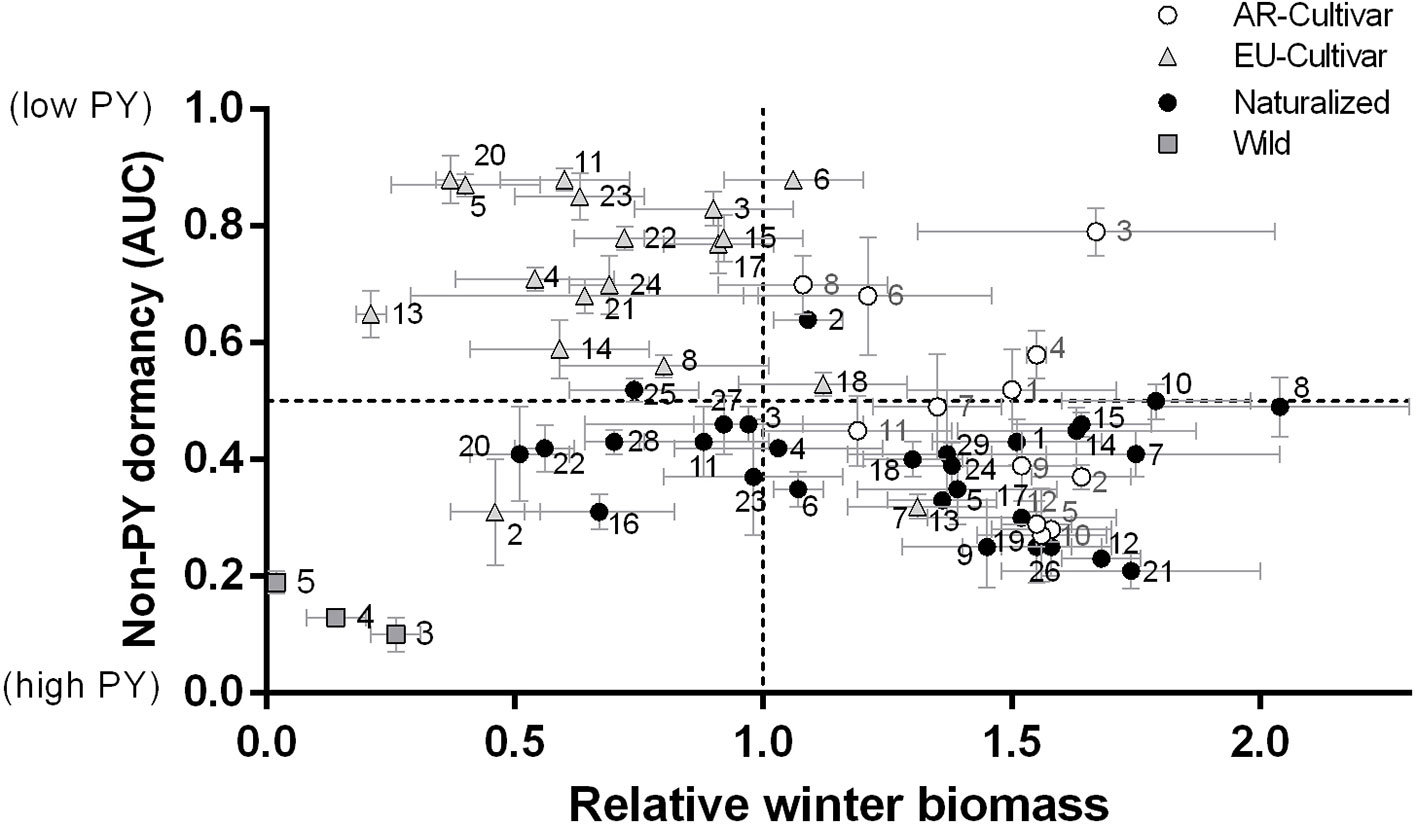

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the main evaluated traits (winter biomass and seed dormancy), in order to identify the more suitable genotypes for breeding programs. Accessions number 9, 12, 19, 21, 26 of naturalized populations and 2, 5, 10, 12 of AR cultivars showed better potential for winter biomass with high PY. While the genotypes number 3, 6, 8 for AR cultivars, 2 for naturalized populations and 6 for EU cultivar showed better potential for both winter biomass and low PY.

Figure 3 Relationship between relative winter biomass and physical (PY) dormancy [area under the curve (AUC)] for each genotype (mean and standard error) evaluated in common garden during 2014 and 2016. For number references see Table 1.

The five selected polymorphic SSR loci produced altogether 24 alleles in 100 tested individuals. The mean number of alleles per locus (N) was 4.8 ± 0.9 ranging from 3 to 8 among the five loci. The mean expected heterozygosity (He) was 0.667 ± 0.03.

Differences in variability were observed between improvement status, being higher in EU cultivars (He = 0.64 ± 0.03; N = 4.4 ± 1.0) and naturalized populations (He = 0.63 ± 0.05; N = 4.6 ± 0.9) compared to AR cultivars (He = 0.57 ± 0.06; N = 3.8 ± 0.9) and wild (He = 0.30 ± 0.09; N = 2.2 ± 0.4) genotypes. The lower value of variability in wild ones might be due to the smaller number of analyzed individuals (n = 10). Two private alleles were found only in naturalized populations. Equilibrium tests were significant in the 68% of cases, indicating non-random mating within populations (Table S3). AMOVA showed a significant differentiation between improvement status, which explained around 19.1% of the variance. Naturalized populations differed from the wild accession (a genetic differentiation of 46.7%) and also from EU (8.3%) and AR (14.3%) cultivars. Lower differentiation was found between AR and EU cultivars (4.3%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Principal coordinate analyses (PCO) plots based on the individual simple sequence repeat (SSR) distance matrix.

AMOVA for the total marker data set is shown in Table 5. Genetic diversity was high within accessions. Between-accession estimated variance was significant and around 25% of the total variation. A small but significant portion of variance (3%) was found attributable to differences between AR and EU genotypes.

Environmental distance matrices were significantly correlated with geographic distance matrices (Mantel test; environment: r2014 = 0.61, P < 0.01; r2016 = 0.78, P < 0.01), suggesting that environmental (climatic + soil) conditions diverge with increasing geographic distance. However, geographic (r2014 = 0.19, P = 0.16; r2016 = 0.10, P = 0.20) nor environmental (r2014 = -0.04, P = 0.54; r2016 = 0.15, P = 0.10) distances were not significantly correlated with phenotypic distance.

Genetic and phenotypic distance matrices of naturalized populations showed a positive but non-significant statistical correlation (Mantel test; r = 0.19, P = 0.21).

Argentinian hairy vetch populations occur on a transitional zone between two defined ecological regions, Pampas with sub-humid climate and Espinal with semiarid conditions (Figure 1). HV was used as a forage species in Buenos Aires province before 1900 (Manganaro, 1919). Thereafter, it probably escaped from cultivation (Aarssen et al., 1986) and became naturalized. As HV natural seed dispersal potential is very limited (Jannink et al., 1997), seed spillage due to handling and transportation was probably the most important distribution method. Human-mediated dispersal is the most likely explanation of establishment and subsequent naturalization of HV into further suitable habitats (Horvitz et al., 2017; Pascher et al., 2017).

After its introduction in Argentina, HV spread over the areas which met the appropriate conditions, following a patchy distribution. HV showed adaptation in broad geographic (33–41°S, latitude, 60–66°W longitude) and climatic range (400–800 mm rainfall; 11–13.6°C annual mean temperature; Table 2). Duke (1981) mentioned that HV is well adapted to a greater range of annual mean temperatures between 4.3–21°C. In this study, low rainfall and warm temperatures during summer months explained HV potential distribution of natural populations (Table 2). HV was generally associated with neutral-alkaline (range 6.1–9.7 pH), sandy or sandy loam soils. However, it could occur on most soil types with sufficient drainage capacity (Duke, 1981). Clark (2007) stated that HV preferred neutral (pH 6.0–7.0) soils with tolerance to alkalinity (Duke, 1981). Conversely, low pH (< 6.2) can decrease the rate growth, nodulation, and nitrogen fixation (Aarssen et al., 1986).

The ability of HV to produce PY+PD dormant seeds and their subsequent germination and emergence are important factors that influence natural population dynamics and persistence (Kimball et al., 2010). During the period of seed formation, dry and warm conditions could shorten the species life cycle due to rapid thermal-time accumulation (Petraityte et al., 2007) as well as favor a decrease on seed moisture content. In HV, the acquisition of PY is initiated only when the moisture content of the seeds is ≤14% (Hyde, 1954). Furthermore, HV is a cross-pollinated species where bees play an important role (Zhang and Mosjidis, 1995; Renzi et al., 2017), thus dry and warm weather is favorable for the activity of pollinating insects (Petraityte et al., 2007; Al-Ghzawi et al., 2009).

In the humid central region of Argentina, the spread of naturalized populations of HV would be limited by a negative combination of two main factors. First, the abundant rainfall stimulates the virulence of foliar fungal diseases (e.g., Ramularia sphaeroidea Sacc. and Ascochyta viciae Lib.), which reduce photosynthetic leaf area thus limiting seed formation (Petraityte et al., 2007; Renzi and Cantamutto, 2013). In addition, high humidity conditions enhance HV indeterminate growth, non-uniform maturity and extended growing season favoring a biennial behavior (Duke, 1981). These consequently limit the seed formation, drying, and acquisition of PY, and can cause a sharp reduction of seed bank persistence and consequent natural regeneration, similar to observations of Toser and Ooi (2014) in Acacia saligna.

After the seed dispersal, warm summer temperatures are required for seed dormancy release (Renzi et al., 2014; Renzi et al., 2016). Seed dormancy acquisition, release, and seedling emergence requirements are important fitness traits determining ecological niches of HV (Figure 1B). These adaptive traits seem to have evolved in Mediterranean-like environments, where hot and dry summer conditions regulate seed dormancy alleviation while cool and wet winters contribute to enhance vegetative growth providing safe-sites for seedling recruitment (Van Assche and Vandelook, 2010; Picciau et al., 2019).

Two cultivars of woolly-pod vetch (Capello and Tolse F.C.A) were found among AR and EU cultivars. This subspecies (V. v. ssp varia) is characterized by shorter leaves (29.8 ± 6 vs. 47.8 ± 9.3 mm in HV, P < 0.01), fewer leaflets (12.3 ± 1.9 vs. 15.2 ± 1.1, P < 0.01); and flowers (20.1 ± 7.7 vs. 26.9 ± 3.4, P < 0.01), early flowering and maturity (more than 2 week before, P < 0.01), higher winter (Figure 3) but lower spring biomass in relation to HV (≈ 60%, P < 0.01). On the other hand, Jannink et al. (1997) found that accessions of HV were more winter-hardy than woolly-pod vetch, and late flowering may be positively genetically correlated with winter hardiness (Maul et al., 2011). The susceptibility of HV to low-temperature increases with more advanced phenological stages (Brandsaeter et al., 2002) while slow growth during winter can be an adaptation attribute to avoid frost damage (Loi et al., 1993). Prompt maturity is a desirable trait for earlier biomass production as well as N accumulation in regions with a shorter growing season. Also, flowering timing can greatly influence the capacity for weed-suppression as a cover crop (Mischler et al., 2010; Maul et al., 2011). Therefore, woolly-pod vetch could be a source of desirable genes for breeding program seeking early flowering cultivars for cover crop usage in mild winter zones. Notably, most of the genotypes characterized as early flowering by Maul et al. (2011) corresponded to woolly-pod vetch (https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/search.aspx).

Quantitative traits evaluated among accessions resembled a continuous probability distribution, although the difference between improvement status was statistically significant (Table 4). AR accessions showed higher winter biomass accumulation compared to EU, probably due to a greater adaptation to Argentinian ecological conditions.

Seed dormancy is largely genetically determined but also depends on the environmental conditions experienced by the mother plant (maternal effect) and the subsequent degree of seed dehydration (Hudson et al., 2015; Finch-Savage and Footitt, 2017). HV seeds were collected from mature pods with seed moisture content less than 14% (determined as a critical value for PY acquisition, Hyde, 1954), and the environmental effect between years was not detected on AUC of PY (Table 4). PY was variable among genotypes and could act mainly as an adaptive trait (Hudson et al., 2015; Long et al., 2015). EU cultivars had lower PY values compared to AR cultivars and naturalized accessions. PY is a highly heritable trait (Hudson et al., 2015) thus it could be useful germplasm for both breeding and artificial (or natural) selection for higher or lower levels of dormancy (Lacerda et al., 2007). It is probable that observed differences between accessions could be explained by genetic adaptations of HV to the local environment (Baskin and Baskin, 2014) as shown in pea (Hradilová et al., 2019) or by selection for improved genotypes (Fuller and Allaby, 2009; Kluyver et al., 2013; Renzi et al., 2016).

Observed large variability within available germplasm could be used by breeders to select parental accessions for HV improvement breeding program that maximizes the winter-spring biomass with low PY for cover crops (Wilke and Snapp, 2008; Wayman et al., 2016), or with high PY for ´ley farming´ systems (Loi et al., 2005; Renzi et al., 2017; Renzi et al., 2018). No significant correspondence was found between the geographic distance matrix and the phenotypic distance matrix (P > 0.15) among the naturalized AR populations and these results differ from Medicago polymorpha L., in which a correspondence between collection site and phenotypic traits (Loi et al., 1993; Helliwell et al., 2018) was observed.

Among the measured traits there was a significant correlation between winter and spring biomass. The latter was also highly correlated with the length of the leaf as described in Vicia sativa (De La Rosa et al., 2002). Leaf size is related to the photosynthetic rates which in turn affect growth and could be potentially maximized with water availability (Carlson et al., 2016). Thus, leaf size would be an indirect selection trait for biomass that improves breeding program efficiency.

There is scarce information on genetic diversity of HV and therefore the knowledge of genetic variability is useful for other studies. Our data showed low genetic differentiation between AR and EU cultivars, but strong differentiation between wild EU and naturalized AR populations. Similarly to other outcrossing species, variation between accessions was small in comparison with the variance found within populations (Table 5), which is expected for an obligate cross-pollinated species (Hamrick and Godt, 1989). Maul et al. (2011) reported similar results, with 93% of genetic diversity within populations.

The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was not stable within populations (Table S3) and this can be attributed to mutations, natural selection, non-random mating, genetic drift, and gene flow. As mentioned above, a lack of geographical signature in the pattern of population variation, as occurs with other allogamous species (Garayalde et al., 2011), can also be explained by human activities on seed dispersal and genetic drift (Knapp and Rice, 1998). Cultivated populations are open-pollinated and highly heterogeneous and would be subject to natural selection and genetic drift throughout the cycles (Wiering et al., 2018). These results are consistent with observed in the phenotypic traits.

This study increases the understanding of the value of naturalized hairy vetch populations in agroecosystems of Argentina. Naturalized populations showed good soil adaptation in disturbed areas and neutral response to alkaline soil niches from central Argentina. Low rainfall and warm temperatures during pre- and post-dispersal seem to explain and regulate the potential distribution of HV populations. Within this ecological context, dry and warm climate may be considered as favorable environmental conditions to increase seed dormancy and timing of germination-triggering. Considering HV genetic variability and agro-ecological adaptation, naturalized populations could be considered as a source of potential adaptive traits for breeding. The AR germplasm constitutes an important reservoir of genes for high winter and spring biomass production. On the other hand, high levels of innate seed dormancy of HV accessions from Argentina reduce its possible use as a cover crop. In this sense, dedicated crosses with more domesticated EU cultivars will serve to reduce the seed dormancy.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

JR and MC conceived the topic. JR and LZ performed the experiments. JR and AG analyzed all statistical data. JR, GC, and AP wrote the manuscript. PS and MC revised the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (PE-E6-I146). Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica. MINCyT (PICT-2017-0473 and PICT-2016-1575) and Universidad Nacional del Sur (PGI 24/A223 and PGI 24/A225).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge V. Holubec of the Department of Gene Bank of the Crop Research Institute (CRI), for providing the cultivars of hairy vetch used in this study, and T. Vymyslický of the Research Institute for Fodder Crops, for performing taxonomic identification of the Serbian accessions. We would like to thank the personnel at CRF-INIA, in particular to M.T. Marcos Prado for help in the niche analysis. Appreciation is extended to O. Reinoso, J. Castillo and M. Bruna, agricultural specialists at the EEA Hilario Ascasubi, for assistance in establishing the field experiments.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00189/full#supplementary-material

Aapresid (2018). Cultivos de cobertura en Argentina. Qué se está haciendo y qué falta? https://www.aapresid.org.ar/rem/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2018/03/Analisis-encuesta-sobre-CC-web.pdf.

Aarssen, L. W., Hall, I. V., Jensen, K. I. N. (1986). The biology of Canadian weed: Vicia angustifolia L., V. cracca L., V. sativa L., V. tetrasperma (L.) Schreb. and V. villosa Roth. Can. J. Plant Sci. 66, 711–737. doi: 10.4141/cjps86-092

Ackroyd, V. J., Cavigelli, M. A., Spargo, J. T., Davis, B., Garst, G., Mirsky, S. B. (2019). Legume cover crops reduce poultry litter application requirements in organic systems. Agron. J. 111, 1–9. doi: 10.2134/agronj2018.09.0622

Al-Ghzawi, A. A., Samarah, N., Zaitoun, S., Alqudah, A. (2009). Impact of bee pollinators on seed set and yield of V. villosa spp. dasycarpa (Leguminosae) grown under semiarid conditions. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 8, 65–74. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2009.65

Baskin, C. C., Baskin, J. M. (2014). Seeds: Ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. 2nd ed. (San Diego: Academic Press).

Brandsaeter, L. O., Olsmo, A., Tronsmo, A. M., Fykse, H. (2002). Freezing resistance of winter annual and biennial legumes at different developmental stages. Crop Sci. 42, 437–443. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2002.4370

Bryant, J. A., Hughes, S. G. (2011). “Vicia,” in Wild crop relatives: Genomic and breeding resources legume crops and forage. Ed. Kole, C. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 273–289.

Burkart, A. (1952). Las leguminosas Argentinas: Silvestres y cultivadas. 2nd ed. (Argentina. Acme Agency: Buenos Aires).

Cantamutto, M., Poverene, M., Peinemann, N. (2008). Multi-scale analysis of two annual Helianthus species naturalization in Argentina. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 123, 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2007.04.005

Carlson, J. E., Adams, C. A., Holsinger, K. E. (2016). Intraspecific variation in stomatal traits, leaf traits and physiology reflects adaptation along aridity gradients in a South African shrub. Ann. Bot. 117, 195–207. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcv146

Chung, J. W., Kim, T. S., Suresh, S., Lee, S. Y., Cho, G. T. (2013). Development of 65 novel polymorphic cdna-ssr markers in common vetch (Vicia sativa subsp sativa) using next generation sequencing. Molecules 18, 8376–8392. doi: 10.3390/molecules18078376

Clark, A. (2007). Managing Cover Crops Profitably. 3rd ed. Handbook series (College Park, MD: SARE).

De La Rosa, L., Lázaro, A., Varela, F. (2002). Utilización en mejora de la variabilidad morfo-agronómica de Vicia sativa L (Almería, España: Congreso de Mejora Genética de Plantas), 319–324.

Deaker, R., Roughley, R. J., Kennedy, I. R. (2004). Legume seed inoculation technology – a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 1275–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.04.009

Di Rienzo, J. A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M. G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., Robledo, C. W. (2013). InfoStat version 2013 Grupo InfoStat, FCA (Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba).

Duke, J. A. (1981). Handbook of legumes of world economic importance (New York and London: Plenum Press), 345 pp.

Excoffier, L., Smouse, P. E., Quattro, J. M. (1992). Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 131, 479–491.

FAO/IIASA/ISSCAS/JRC. (2012). Harmonized World Soil Database (version 1.2) (Rome, Italy and IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria: FAO).

Fick, S. E., Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. doi: 10.1002/joc.5086

Finch-Savage, W. E., Footitt, S. (2017). Seed dormancy cycling and the regulation of dormancy mechanisms to time germination in variable field environments. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 843–856. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw477

Francis, C. M., Enneking, D., Abd El Moneim, A. (1999). “When and where will vetches have an impact as grain legumes?” in Linking research and marketing opportunities for pulses in the 21st Century. Proceedings of the Third International Food Legume Research Conference" Adelaide, S. Aust., 1997. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture. Vol. 34. Ed. Knight, R. (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 671–683.

Frasier, I., Noellemeyer, E., Amiotti, N., Quiroga, A. (2017). Vetch-rye biculture is a sustainable alternative for enhanced nitrogen availability and low leaching losses in a no-till cover crop system. Field Crops Res. 214, 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.08.016

Fuller, D. Q., Allaby, R. (2009). “Seed Dispersal and Crop Domestication: shattering, germination and seasonality in evolution under cultivation,” in Fruit Development and Seed Dispersal. Ed. Ostergaard, L. (Blackwell: Oxford), 238–295.

Garayalde, A. F., Poverene, M., Cantamutto, M., Carrera, A. D. (2011). Wild sunflower diversity in Argentina revealed by ISSR and SSR markers: an approach for conservation and breeding programmes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 158, 305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2011.00465.x

Hamrick, J. L., Godt, M. J. W. (1989). “Allozyme diversity in plant species,” in Plant Population Genetics, Breeding and Genetic Resources. Eds. Brown, A. H. D., Clegg, M. T., Kahler, A. L., Weir, B. S. (Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates), 43–63.

Helliwell, E., Faber-Hammond, J., Lopez, Z. C., Garoutte, A., von Wettberg, E., Friesen, M. L., et al. (2018). Rapid establishment of a flowering cline in Medicago polymorpha after invasion of North America. Mol. Ecol. 27, 4758–4774. doi: 10.1111/mec.14898

Hernandez, P. A., Graham, C. H., Master, L. L., Albert, D. L. (2006). The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography 29, 773–785. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04700.x

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G., Jarvis, A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978. doi: 10.1002/joc.1276

Hoisington, D., Khairallah, M., González de León, D. (1994). Laboratory Protocols: CIMMYT Applied Molecular Genetics Laboratory. 2nd edn. (México, DF, Mexico: CIMMYT).

Horvitz, N., Wang, R., Wan, F.-H., Nathan, R. (2017). Pervasive human-mediated large-scale invasion: analysis of spread patterns and their underlying mechanisms in 17 of China’s worst invasive plants. J. Ecol. 105, 85–94. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12692

Hradilová, I., Duchoslav, M., Brus, J., Pechanec, V., Hýbl, M., Kopecký, P., et al. (2019). Variation in wild pea (Pisum sativum subsp. elatius) seed dormancy and its relationship to the environment and seed coat traits. PeerJ 7, e6263. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6263

Hudson, A. R., Ayre, D. J., Ooi, M. K. J. (2015). Physical dormancy in a changing climate. Seed Sci. Res. 25, 66–81. doi: 10.1017/S0960258514000403

Hyde, E. O. C. (1954). The function of the hilum in some Papilionaceae in relation to the ripening of the seed and the permeability of the testa. Ann. Bot. 11, 241–256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a083393

International Seed Testing Association (2019). International Rules for Seed Testing (Zürich: ISTA), 300. doi: 10.15258/istarules.2019.F

Jacobsen, K. L., Gallagher, R. S., Burnham, M., Bradley, B. B., Larson, Z. M., Walker, C. W., et al. (2010). Mitigation of seed germination impediments in hairy vetch. Agr. J. 102, 1346–1351. doi: 10.2134/agronj2010.0002n

Jannink, J. L., Merrick, L. C., Liebman, M., Dyck, E. A., Corson, S. (1997). Management and winter hardiness of hairy vetch in Maine. Tech. Bull. 167, 35. Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station.

Kimball, S., Angert, A. L., Huxman, T. E., Venable, D. E. (2010). Contemporary climate change in the Sonoran Desert favors cold-adapted species. Glob Chang Biol. 16, 1555–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02106.x

Kluyver, T. A., Charles, M., Jones, G., Rees, M., Osborne, L. P. (2013). Did greater burial depth increase the seed size of domesticated legumes? J. Exp. Bot. 64, 4101–4108. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert304

Knapp, E. E., Rice, K. J. (1998). Comparison of isozymes and quantitative traits for evaluating patters of genetic variation in purple needlegrass (Nassella pulchra). Conserv. Biol. 12, 1031–1041. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.97123.x

Lacerda, D. R., Lemos Filho, J. P., Goulart, M. F., Ribeiro, R. A. (2007). Seed-dormancy variation in natural populations of two tropical leguminous tree species: Senna multijuga (Caesalpinoideae) and Plathymenia reticulata (Mimosoideae). Seed Sci. Res. 14, 127–135. doi: 10.1079/SSR2004162

Lawson, A., Cogger, C., Bary, A., Fortuna, A.-M. (2015). Influence of seeding ratio, planting date, and termination date on rye-hairy vetch cover crop mixture performance under organic management. PloS One 10 (6), e0129597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129597

Loi, A., Howieson, J. G., Cocks, P. S., Caredda, S. (1993). The adaptation of Medicago polimorpha to a range of edaphic and environmental conditions: effect of temperature on growth, and acidity stress on nodulation and nod gene induction. Aust. J. Exp. Agr. 33, 25–30. doi: 10.1071/EA9930025

Loi, A., Howieson, J. G., Nutt, B. J., Carr, S. J. (2005). A second generation of annual pasture legumes and their potential for for inclusion in Mediterranean-type farming systems. Aust. J. Exp. Agr. 45, 289–299. doi: 10.1071/EA03134

Long, R. L., Gorecki, M. J., Renton, M., Scott, J. K., Colville, L., Goggin, D. E., et al. (2015). The ecophysiology of seed persistence: a mechanistic view of the journey to germination or demise. Biol. Rev. 90, 31–59. doi: 10.1111/brv.12095

Manganaro, A. (1919). “Leguminosas bonaerenses,” in Anales de la Sociedad Científica Argentina. Eds. Carrete, E., Lizer, C. (Buenos Aires), 77–264.

Maul, J., Mirsky, S., Emche, S., Devine, T. (2011). Evaluating a germplasm collection of the cover crop hairy vetch for use in sustainable farming systems. Crop Sci. 51, 2615–2625. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2010.09.0561

Mirsky, S., Ackroyd, V. J., Cordeau, S., Curran, W. S., Hashemi, M., Reberg-Horton, S. C., et al. (2017). Hairy vetch biomass across the Eastern United States: effects of latitude, seeding rate and date, and termination timing. Agron. J. 109, 1–10. doi: 10.2134/agronj2016.09.0556

Mischler, R., Duiker, S. W., Curran, W., Wilson, D. (2010). Hairy vetch management for no-till organic corn production. Agron. J. 102, 355–362. doi: 10.2134/agronj2009.0183

Pascher, K., Hainz-Renetzeder, C., Gollmann, G., Schneeweiss, G. M. (2017). Spillage of viable seeds of oilseed rape along transportation routes: ecological risk assessment and perspectives on management efforts. Front. Ecol. Evol. 5, 104. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00104

Peakall, R., Smouse, P. E. (2006). GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 6, 288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x

Peakall, R., Smouse, P. E., Huff, D. R. (1995). Evolutionary implications of allozyme and RAPD variation in diploid populations of buffalograss Buchloe dactyloides. (Nutt. Engelm.). Mol. Ecol. 4, 135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1995.tb00203.x

Petraityte, N., Sliesaravicius, A., Dastikaite, A. (2007). Potential reproduction and real seed productivity of Vicia villosa L. Biologija 53, 48–51.

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., Schapire, R. E. (2006). Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model 190, 231–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Phillips, S. J., Dudík, M., Schapire, R. E. (2018). Maxent software for modeling species niches and distributions (Version 3.4.1). http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/opensource/maxent/. Accessed on 2018-10-05.

Picciau, R., Pritchard, H. W., Mattana, E., Bacchetta, G. (2019). Thermal thresholds for seed germination in Mediterranean species are higher in mountain compared with lowland areas. Seed Sci. Res. 29, 44–54. doi: 10.1017/S0960258518000399

Raveendar, S., Lee, G. A., Jeon, Y. A., Lee, Y. J., Lee, J. R., Cho, G. T., et al. (2015). Cross-amplification of Vicia sativa subsp. sativa microsatellites across 22 other Vicia species. Molecules 20, 1543–1550. doi: 10.3390/molecules20011543

Renzi, J. P., Cantamutto, M. A. (2013). Vicias: Bases agronómicas para el manejo en la Región Pampeana (Vicias: Agronomic bases for management in the Pampas) (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ediciones INTA), 299.

Renzi, J. P., Chantre, G. R., Cantamutto, M. A. (2014). Development of a thermal-time model for combinational dormancy release of hairy vetch (Vicia villosa ssp. villosa). Crop Pasture Sci. 65, 470–478. doi: 10.1071/CP13430

Renzi, J. P., Chantre, G. R., Cantamutto, M. A. (2016). Effect of water availability and seed source on physical dormancy break of Vicia villosa ssp. Villosa. Seed Sci. Res. 26, 254–263. doi: 10.1017/S096025851600012X

Renzi, J. P., Chantre, G. R., Cantamutto, M. A. (2017). Self-regeneration of hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) as affected by seedling density and soil tillage method in a semi-arid agroecosystem. Grass Forage Sci. 72, 535–544. doi: 10.1111/gfs.12255

Renzi, J. P., Chantre, G., Cantamutto, M. A. (2018). Vicia villosa ssp. villosa Roth field emergence model in a semiarid agroecosystem. Grass Forage Sci. 73, 146–158. doi: 10.1111/gfs.12295

Renzi, J. P., Chantre, G. R., González-Andújar, J. L., Cantamutto, M. A. (2019). Development and validation of a simulation model for hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) self-regeneration under different crop rotations. Field Crops Res. 235, 79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2019.02.020

Santos, D. J., Wilson, M. G., Ostinelli, M. M. (2017). Metodología de muestreo de suelos y ensayos a campo (Entre Ríos, Argentina: Ediciones INTA).

Smouse, P. E., Peakall, R. (1999). Spatial autocorrelation analysis of individual multiallele and multilocus genetic structure. Heredity 82, 561–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6885180

Smouse, P. E., Long, J. C., Sokal, R. R. (1986). Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the Mantel test of matrix correspondence. Syst. Zool. 35, 627–632. doi: 10.2307/2413122

Tang, S., Kishore, V. K., Knapp, S. J. (2003). PCR-multiplexes for a genome-wide framework of simple sequence repeat marker loci in cultivated sunflower. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 6–19. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1233-0

Toser, M. G., Ooi, M. K. J. (2014). Humidity-regulated dormancy onset in the Fabaceae: a conceptual model and its ecological implications for the Australian wattle Acacia saligna. Ann. Bot. 114, 579–590. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu144

Van Assche, J. A., Vandelook, F. (2010). Combinational dormancy in winter annual Fabaceae. Seed Sci. Res. 20, 237–242. doi: 10.1017/S0960258510000218

Van de Wouw, M., Enneking, D., Robertson, L. D., Maxted, N. (2001). “Vetches (Vicia L.),” in Plant genetic resources of legumes in the Mediterranean. Eds. Maxted, N., Bennett, S. J. (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer), 132–157.

Vanzolini, J. I. (2011). La vicia villosa como cultivo de cobertura: efectos de corto plazo sobre el suelo y la productividad del maíz bajo riego en el Valle Bonaerense del río Colorado (Universidad Nacional del Sur, Buenos Aires, Argentina: MScThesis).

Wayman, S., Kissing Kucek, L., Mirsky, S. B., Ackroyd, V., Cordeau, S., Ryan, M. R. (2016). Organic and conventional farmers differ in their perspectives on cover crop use and breeding. Renew Agr. Food Syst. 32, 376–385. doi: 10.1017/S1742170516000338

Wiering, N. P., Flavin, C., Sheaffer, C. C., Heineck, G. C., Sadok, W., Ehlke, N. J. (2018). Winter hardiness and freezing tolerance in a hairy vetch collection. Crop Sci. 58, 1594–1604. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2017.12.0748

Wilke, B. J., Snapp, S. S. (2008). Winter cover crops for local ecosystems: Linking plant traits and ecosystem function. J. Sci. Food Agric. 88, 551–557. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3149

Zhang, X., Mosjidis, J. A. (1995). Breeding systems of several Vicia species. Crop Sci. 35, 1200–1202. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1995.0011183X003500040049x

Keywords: Vicia villosa genotypes, naturalized population, niche-modeling, genetic resource, phenotypic characterization, microsatellites

Citation: Renzi JP, Chantre GR, Smýkal P, Presotto AD, Zubiaga L, Garayalde AF and Cantamutto MA (2020) Diversity of Naturalized Hairy Vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) Populations in Central Argentina as a Source of Potential Adaptive Traits for Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 11:189. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00189

Received: 07 October 2019; Accepted: 07 February 2020;

Published: 28 February 2020.

Edited by:

Laurent Gentzbittel, National Polytechnic Institute of Toulouse, FranceReviewed by:

Hamid Khazaei, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaCopyright © 2020 Renzi, Chantre, Smýkal, Presotto, Zubiaga, Garayalde and Cantamutto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan P. Renzi, cmVuemlwdWduaS5qdWFuQGludGEuZ29iLmFy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.