94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 21 November 2019

Sec. Plant Systematics and Evolution

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01477

Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (Melastomataceae) comprises ca. 50 genera, two thirds of which occur in Southeast Asia. Phylogenetic relationships within this clade remain largely unclear, which hampers our understanding of its origin, evolution, and biogeography. Here, we explored the use of chloroplast genomes in phylogenetic reconstruction of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, by sampling 138 species and 23 genera in this clade. A total of 151 complete plastid genomes were assembled for this study. Plastid genomic data provided better support for the backbone of the Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae phylogeny, and also for relationships among most closely related species, but failed to resolve the short internodes likely resulted from rapid radiation. Trees inferred from plastid genome and nrITS sequences were largely congruent regarding the major lineages of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. The present analyses recovered 15 major lineages well recognized in both nrITS and plastid phylogeny. Molecular dating and biogeographical analyses indicated a South American origin for Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae during late Eocene (stem age: 34.78 Mya). Two dispersal events from South America to the Old World were detected in late Eocene (33.96 Mya) and Mid Oligocene (28.33 Mya) respectively. The core Asian clade began to diversify around early Miocene in Indo-Burma and dispersed subsequently to Malesia and Sino-Japanese regions, possibly promoted by global temperature changes and East Asian monsoon activity. Our analyses supported previous hypothesis that Medinilla reached Madagascar by transoceanic dispersal in Miocene. In addition, generic limits of some genera concerned were discussed.

The Southeast Asia (SEA) is known for its complex geological history (Turner et al., 2001) and unique and rich biota (Mittermeier et al., 1999; Sodhi et al., 2004). This region, although covering only 4% of the earth’s land area, harbors approximately 20%–25% of the higher plant species on the planet (Woodruff, 2010; Corlett, 2014). According to Myers et al. (2000), SEA includes three out of the world’s eight hottest biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. However, how these diverse plants originate, disperse, and evolve remains largely unanswered. Phylogenetic and integrated systematic research, often even the basic taxonomic work (descriptions and revisions) which serve as the basis of conservation, are far from sufficient for many groups of organisms in SEA (Sodhi and Liow, 2000; Jin et al., 2018). The pantropical Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae complex, with its distribution centered in SEA, is one of such groups. Sonerileae (Melastomataceae) was originally circumscribed as including mainly paleotropical herbaceous species (Triana, 1865, Triana, 1871). Most authors followed Triana’s classification (Cogniaux, 1891; Krasser, 1893; Diels, 1932; Li, 1944; Chen, 1984a), but Van Vliet et al. (1981) and Renner (1993) proposed a wider circumscription of Sonerileae to include also the paleotropical Oxysporeae (shrubby) and the neotropical Bertolonieae (herbaceous). Recent molecular phylogenetic studies revealed that Sonerileae and Oxysporeae were nested with Dissochaeteae forming a well-supported Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae clade that showed no close relationship with core Bertolonieae (Clausing, 1999; Clausing et al., 2000; Clausing and Renner, 2001a; Clausing and Renner, 2001b; Renner et al., 2001; Fritsch et al., 2004; Goldenberg et al., 2012; Michelangeli et al., 2014; Veranso-Libalah et al., 2017; Veranso-Libalah et al., 2018; Bacci et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae comprises over 1000 species in ca. 50 genera, two thirds of which occur in SEA.

Generic delimitation and phylogenetic relationships within Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae are poorly understood, and many of the genera are of doubtful taxonomic validity, especially for those endemics of SEA (Cellinese, 1997; Clausing and Renner, 2001a). One prominent example would be Phyllagathis Blume, which contains approximately 70 species distributed from southern China, Indo-Burma to Sundaland (Cellinese, 2002; Chen and Renner, 2007; Wangwasit et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2015; Mathew et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2017; Vu et al., 2017). Transfers of species have been made between Phyllagathis and various genera, viz. Anerincleistus Korth. (Hansen, 1982; Maxwell, 1982; Cellinese, 2002), Bredia Blume (Li, 1944; Chen, 1984b), Cyphotheca Diels (Hu, 1952), Plagiopetalum Rehder (Chen, 1984b), Scorpiothyrsus H.L. Li (Li, 1944), and Stapfiophyton H.L. Li (= Fordiophyton Stapf) (Chen, 1984b). Publications of some small genera morphologically related to Phyllagathis had made the generic boundaries even more obscure (Chen, 1979; Chen, 1984b; Hansen, 1990; Hansen, 1992; Renner, 1993; Cellinese, 2002; Cellinese, 2003). Renner et al. (2001) and Clausing and Renner (2001a) represented the first comprehensive molecular studies of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, within which 29 species from 18 genera of this clade were sampled. Phylogenetic analyses confirmed the nesting of Sonerileae s.l. (including Oxysporeae) within Dissochaeteae, however, limited sampling of species prevent any discussion of generic limit in this clade. Zeng et al. (2016a,2016b), Zhou et al. (2018), Veranso-Libalah et al. (2018), and Bacci et al. (2019) focused mainly on Fordiophyton, Bredia, Melastomateae, and Bertolonieae respectively, sampling even fewer genera of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. Zhou et al. (2019) analyzed 109 species from 19 genera. This study clearly demonstrated the chaotic generic delimitation and succeeded in identifying a dozen of major lineages within Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. However, the backbone phylogeny of this complex remained largely unresolved in all the above studies, severely hindering taxonomic revisions.

The estimated age and biogeographical history of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae also remain controversial. Several studies have explored these issues using fossil-calibrated phylogeny based on DNA sequences of one or a few regions (ndhF, rbcL, rpl16, accD-psaI, psbK-psbL, nrITS, ETS, 18S, 26S) (Renner et al., 2001; Morley and Dick, 2003; Renner, 2004a; Renner, 2004b; Berger et al., 2016; Veranso-Libalah et al., 2018). The stem age of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae was estimated to be 19 Mya (Renner et al., 2001), 38 Mya (Berger et al., 2016), 39.63 Mya (Veranso-Libalah et al., 2018), or 73 Mya (Morley and Dick, 2003). Previous authors had proposed three competing hypotheses on the biogeographical history of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae: (1) diversification in SEA during Miocene and subsequent trans-oceanic dispersal of two sublineages from SEA to Madagascar and Africa; (2) dispersal from South America to Africa ca. 74 Mya ago followed by diversification and rafting on the Indian Plate to SEA (“Indian Ark” hypothesis); and (3) trans-Atlantic dispersal from South America to Africa during Late Eocene. The merit of these hypotheses needs further testing.

Previous studies were based on sequence data of nuclear ribosomal ITS (nrITS) and/or a few chloroplast markers (trnV-trnM, ndhF, rbcL, rpl16), both of which have their own limitations. nrITS, although proven useful in phylogenetics of Melastomateae (Michelangeli et al., 2012; Veranso‐Libalah et al., 2017; Veranso‐Libalah et al., 2018), failed to resolve the backbone of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. Chloroplast DNA sequences have been extensively used in phylogenetic analyses of angiosperms because of their conserved structure, high copy numbers, and uniparental inheritance (Birky, 1995). However, the use of only a few chloroplast genes is often insufficient to resolve genera or species level relationships due to low mutation rate (Shaw et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2014). The advent of next-generation sequencing technologies offers a cost-effective means to obtain chloroplast genomic data, which have been successfully used to tackle difficult phylogenetic questions of plants from deep to shallow taxonomic level (Ma et al., 2014; Stull et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Heckenhauer et al., 2018; Niu et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2018). A chloroplast phylogenomic approach may help to better elucidate the relationships and biogeography of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae.

This paper aims to (1) reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, (2) infer the divergence times and biogeographical history, and (3) reassess the current generic delimitations based on the resulted phylogeny. To this end, we include in this study 138 species representing 23 genera in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, with a special emphasis on the widely distributed Phyllagathis.

For phylogenomic analyses, 171 plastid genomes (152 species and five varieties) were included, representing one genus from Myrtaceae, and 42 genera from major lineages of Melastomataceae [Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (23), Astronieae (1), Bertolonieae (1), Blakeeae (1), Cyphostyleae (1), Henrietteeae (1), Kibessieae (1), Marcetieae (1), Melastomateae (3), Memecyleae (1), Merianieae (2), Merianthera Group (1), Miconieae (2), Microlicieae (1), Rhexieae (1), Trioieneae (1)]. Twenty plastid genomes were obtained from previous reports (Reginato et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2019), while the remaining were newly sequenced. For the highly polyphyletic Phyllagathis, 42 species were sampled from China, Vietnam, Malaysian Peninsula, and Borneo to cover its morphological and geographical range. A list of the taxa sampled in chloroplast phylogenomic analyses, their sampling locations, voucher information, and GenBank accession numbers were provided in Table S1.

Two phylogenomic datasets were assembled. (1) The Melastomataceae dataset, which contained all chloroplast genomes available in the family, was assembled for phylogenomic analysis. The resulted tree was also used as input tree in divergence time estimation and ancestral range reconstruction. The dataset was pre-analyzed using an outgroup from Myrtaceae (Eucalyptus grandis W. Mill ex Maiden). The most basal clade of Melastomataceae, Memecylon-Pternandra, was then selected as outgroup for this dataset. (2) The Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae dataset, which was used for comparison of phylogenies generated by chloroplast genome and nrITS sequence data. It comprised the chloroplast genomes of this clade and Blakea schlimii (Naudin) Triana (Blakeeae), with the latter selected as an outgroup.

To facilitate discussion, two additional datasets were assembled. An nrITS dataset parallel to the Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae genomic dataset (excluding Opisthocentra clidemioides Hook.f. as its nrITS sequence was not available) was analyzed for comparison. Another dataset of five concatenated plastid regions (rbcL, rpl16, ndhF, psbK-psbL, accD) (hereafter referred to as cp-5 gene dataset) with partially missing data was constructed to test the phylogenetic position of those African and South American species without available plastid genomic data. Please see Table S2 for detailed sampling list and GenBank accession numbers for nrITS and plastid markers.

Total DNA was extracted from silica-gel dried leaves or fresh leaf tissue (when available) using the modified CTAB procedure (Doyle and Doyle, 1987) or using HiPure Plant DNA Mini Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Libraries were prepared from the total genomic DNA of 151 samples using Next Ultra II DNA Library Construction Kit (NEB, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Shotgun sequencing was then performed on an Illumina HiSeq™ 2500 platform (150 bp paired-end reads) at Vazyme (Nanjing, China)/Novogene (Beijing, China).

The nrITS region was amplified and sequenced using universal primers (White et al., 1990) or assembled and extracted from our genomic shotgun sequencing reads. For polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing, we followed the same procedure described in Zou et al. (2017). A mapping-based method was used to extract nrITS sequences from NGS sequencing data. First, nrITS sequences of most closely related species were applied as references to construct a BWA index (Li and Durbin, 2010). Short reads were then mapped to the reference with BWA-MEM. The resulting aligned SAM file were sorted and converted to BAM format. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels calling were conducted by SAMtools mplieup (Li et al., 2009) and BCFtools (https://github.com/samtools/bcftools). Finally, BCFtools was used to replace corresponding positions of reference with SNP information using consensus option, resulting in a FASTA sequence for a synthetic sequence of nrITS. Eighty nrITS sequences were newly generated.

To assemble the chloroplast genome of 151 samples, the total sequencing output, approximately 13 Gb of paired-end (PE z= 150 bp) sequence data per sample, was used as input into NOVOPlasty v1.2.4 (Dierckxsens et al., 2017). The partial sequence of rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit) of Melastoma candidum D. Don (GenBank accession number GQ436728) was adopted as the seed sequence in the seed-and-extend algorithm implemented in NOVOPlasty v1.2.4 (Dierckxsens et al., 2017). Annotation of the chloroplast genome was performed using the DOGMA online tool (Wyman et al., 2004) and then manually checked with the start/stop codons and junctions between introns and exons. The circular chloroplast genome maps were drawn with OGDRAW v1.3 (Lohse et al., 2007).

Chloroplast genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.042 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) with default settings. Only one copy of the IRs was used in the final alignment to avoid overrepresentation of duplicated sequences. Dubiously aligned regions may bias phylogenetic inferences (Misof and Misof, 2009) and previous phylogenetic analyses of Melastomataceae based on plastid genome showed that among all the analytical schemes explored, only the non-coding regions without filtering of ambiguous aligned base pairs resulted in conflicting topology (Reginato et al., 2016). Therefore, we removed the poorly aligned regions from all phylogenomic datasets before subsequent analyses using trimAl v1.2 with “-gappyout” mode (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). Sequences of nrITS and the five plastid markers were aligned using SeqMan v7.1.0 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA) and manually adjusted.

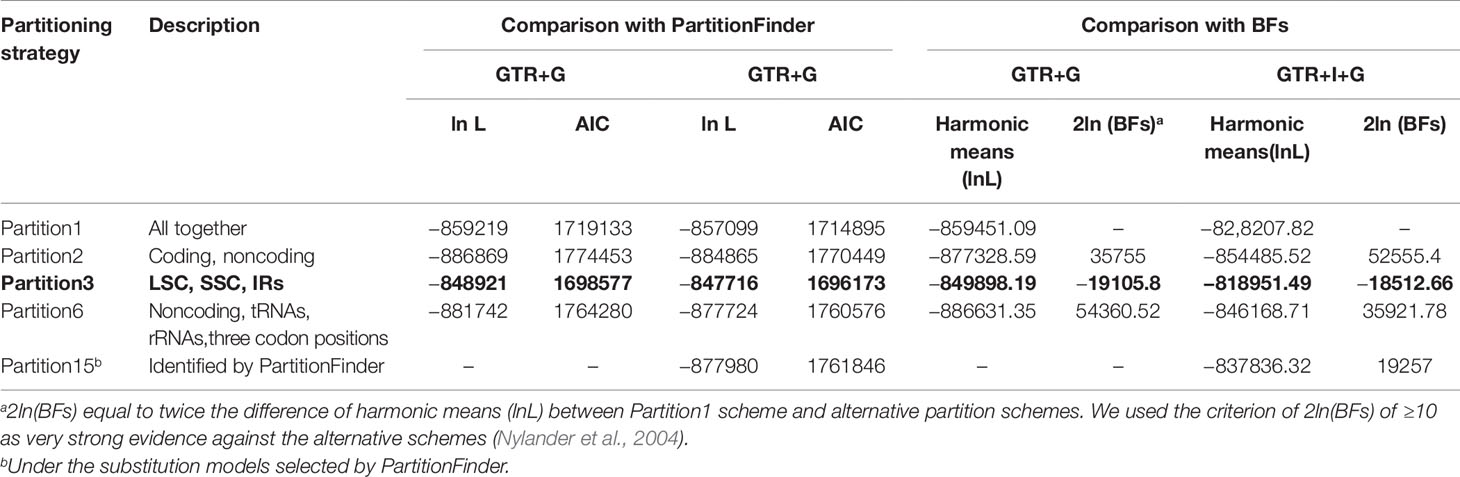

We explored the issue of data partitioning using the Melastomataceae phylogenomic dataset. Five partitioning schemes were employed in the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian analyses: (1) no partitions, (2) two partitions, coding and noncoding sequences, (3) three partitions corresponding to large single copy (LSC) region, small single copy (SSC) region, and inverted repeat region (IR), (4) six partitions, viz. protein coding genes divided by three codon positions, tRNAs, rRNAs, and noncoding sequences, and (5) 15 partitions, which was determined as the best-fit partition scheme by PartitionFinder v2.1.1 (Lanfear et al., 2012), based on the following strategy. Firstly all protein coding genes were divided into 12 clusters by function as shown in Figure S1 (each cluster was colored uniquely). For two of these clusters, “other genes” (accD, ccsA, and cemA) and “hypothetical chloroplast reading frame” (ycf1, ycf2, ycf3, and ycf4), which comprised several genes with different or unknown functions, each gene was further treated as a separate cluster. Each of the above 17 gene clusters was then divided into three subsets by codon position. With noncoding sequences, rRNA genes and tRNA genes treated as another three subsets, the Melastomataceae phylogenomic dataset was splitted into 54 subsets in total and then these subsets were assigned as input into PartitionFinder to select best-fit partitioning scheme and corresponding nucleotide substitution models.

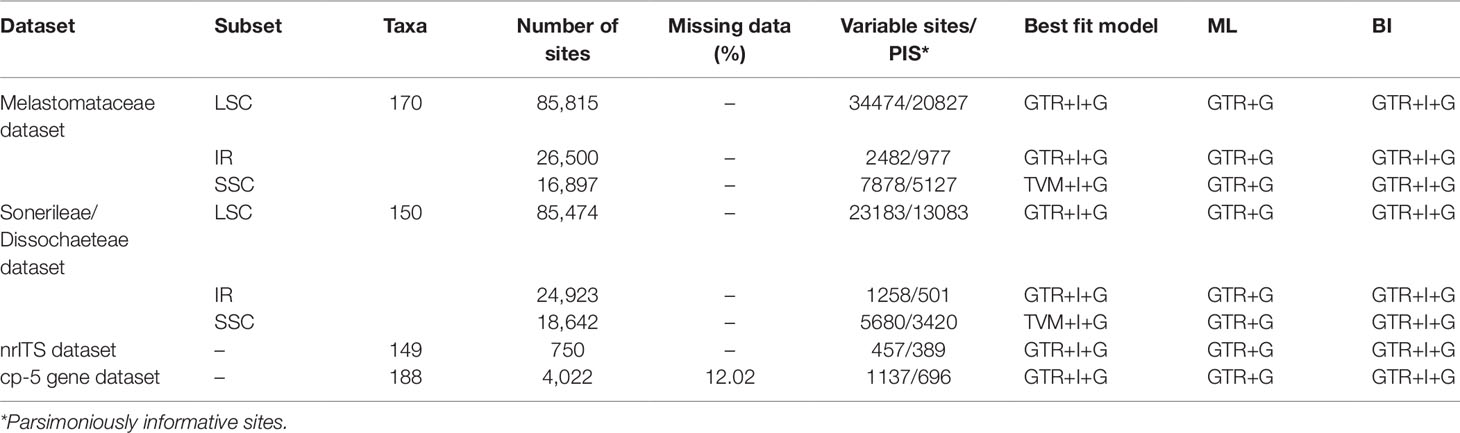

The best-fitting models for each partition in the first four partitioning schemes as well as for nrITS dataset and cp-5 gene dataset were determined using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Posada and Buckley, 2004) in Modeltest version 3.7 (Posada and Crandall, 1998). For the fifth partitioning scheme, model for each partition is determined using PartitionFinder. For a summary of the model selection, see Table S3.

Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were carried out in MrBayes 3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001) on the CIPRES cluster (Miller et al., 2010). When the model selected by Modeltest was not available in MrBayes, a more parameterized model was used (TVM was replaced by GTR, Table 2 and Table S3). A recent empirical study has demonstrated that in certain situations, using both parameters I and G to accommodate rate variation across sites could lead to non-optimal values for both parameters (Moyle et al., 2012). Therefore, we also ran a parallel analysis replacing the selected model GTR+I+G with GTR+G and compared the results to detect potential parameter interaction. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were run each with four simultaneous chains (three heated and one cold) for 3,000,000 generations with the temperature parameter set to 0.08. Trees were sampled every 100 generations, with the first 7,500 trees (25%) discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to construct a 50% majority-rule consensus tree with Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP). Convergence was considered reached when the average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01. The effective sample sizes (ESS) were also assessed for all parameters and statistics using Tracer v1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). All ESS were obtained with values higher than 200, indicating that all parameters were sampled sufficiently for all chains to converge.

Maximum likelihood analyses were conducted in RAxML version 8.2.10 (Stamatakis, 2014) using the GTR+G model as recommended by the author. Node support was estimated with 1000 bootstrap replicates using a fast bootstrapping algorithm in RAxML (Stamatakis et al., 2008).

To compare the five partitioning strategies employed, we calculated marginal likelihood and Bayes factor (the ratio of marginal likelihoods from two competing models) using Tracer v1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018) as described in Ma et al. (2014). We also used PartitionFinder to choose the best partition scheme by constraining the substitution model to GTR+G/GTR+I+G. The partition scheme with lowest AIC was considered to be the most fitting one. The best partition scheme was then applied to the final analyses of the two plastid phylogenomic datasets.

Three dating priors were utilized, one secondary calibration from a recent study of Myrtales (Berger et al., 2016), and two fossils of Melastomataceae widely used in previous biogeographical studies of the family (Renner and Meyer, 2001; Morley and Dick, 2003; Renner, 2004a; Renner, 2004b; Veranso‐Libalah et al., 2018). The secondary calibration from Berger et al. (2016) is used to constrain the age of Melastomataceae s.l. (including Memecylon, node a) at 64.5 Ma [74.8–56.1 Ma, 95% highest posterior density (HPD)]. An Eocene fossil leaf from North America (Hickey, 1977) had the basic venation of Melastomataceae s.s. (excluding Memecylon). Conservatively, we used it to constrain the age of node b (excluding the most basal clade Memecylon-Pternandra) at 53 Ma. Another fossil prior is Miocene seed characteristic of Melastomateae and Rhexieae (Collinson and Pingen, 1992; Renner and Meyer, 2001). It was used to constrain the Melastomateae-Marcetieae-Rhexieae node (node c) at 26–23 Ma.

Divergence time estimation was performed in BEAST 2.5.2 (Bouckaert et al., 2014), using an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock with a birth-death speciation process (Kendall, 1948; Nee et al., 1994; Gernhard, 2008). Due to limited computational budget, sequences of nine protein coding genes (atpB, matK, ndhF, psaB, psbB, rbcL, rpl2, rpoC2, rps4; aligned length: 15984 bp) from nine gene clusters were extracted from the Melastomataceae dataset and assembled into a combined matrix as input alignment to BEAST. For the secondary calibration, we used a normal distribution with a standard deviation equivalent to the 95% HPD estimate of Berger et al. (2016). For the two fossil priors, a lognormal distribution with a mean of 1.5 and a standard deviation of 1 was adopted to allow for the possibility that the nodes are older than the fossils themselves (Sauquet, 2013; Berger et al., 2016). We ran two independent MCMC analyses, each of 350,000,000 generations sampling every 1,000 generations. The effective sampling of all parameters and convergence of independent chains were examined using Tracer version 1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). The obtained parameters and distribution of effective priors were broadly similar to those of corresponding specified priors, indicating that the calibration strategy was relatively reliable (Figure S2). LogCombiner v.2.4.5 (Bouckaert et al., 2014) was then used to combine the output files of independent runs, after the removal of 10% of samples as burn-in. Finally, estimated divergence time information was annotated to a constrained ML tree generated by the Melastomataceae dataset under best partition scheme using TreeAnnotator v.2.4.5 (Bouckaert et al., 2014).

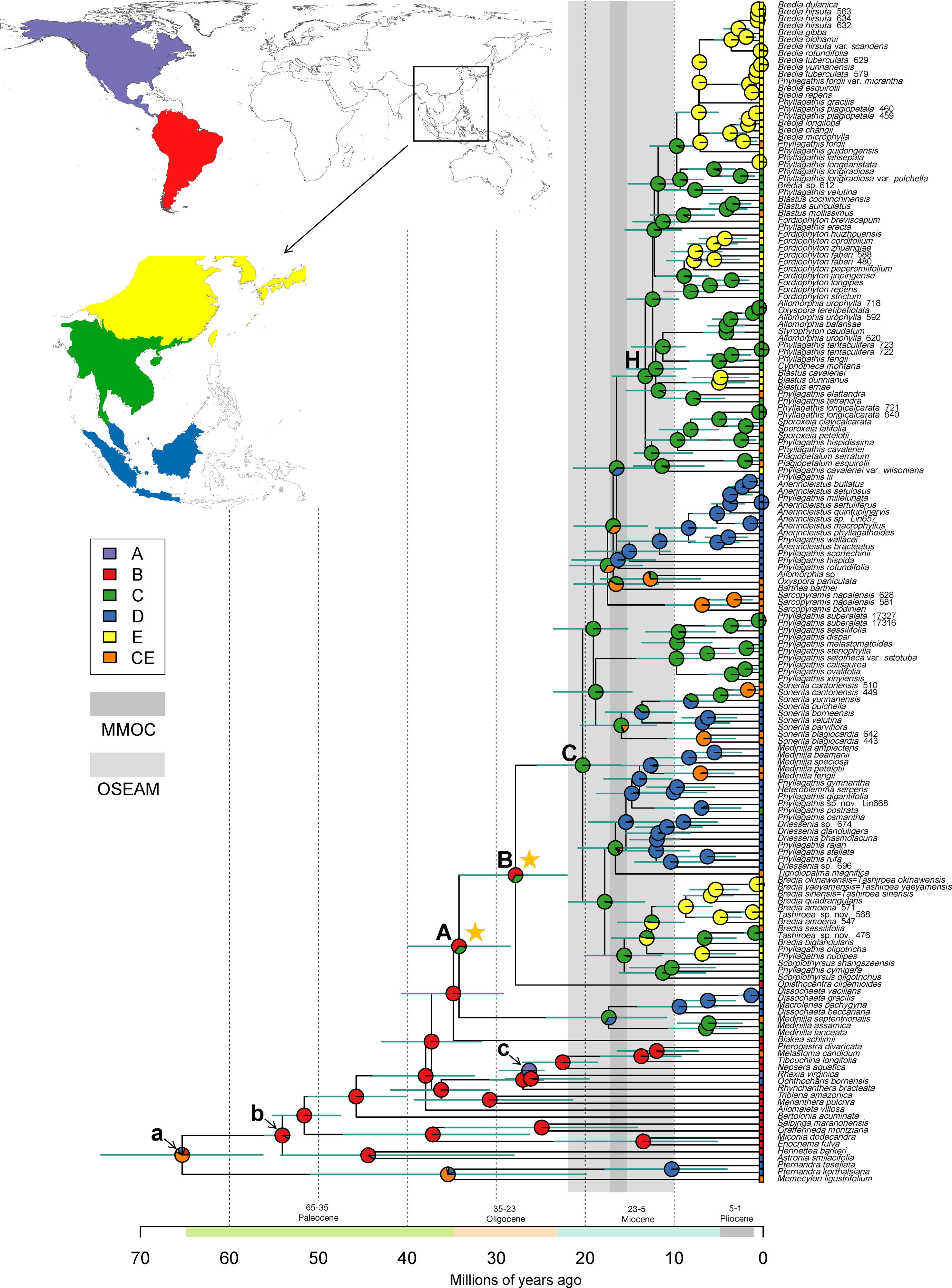

Ancestral range estimation was carried out using RASP (Yu et al., 2015). We used the annotated tree generated from BEAST analysis as input of the ancestral range estimation (ARE). The best-fit model Bayarealike+j was selected from the six models implemented in the software based on the AIC and likelihood ratio test results. We identified five geographical areas modified from Good (1974), Myers et al. (2000), and recent studies (Berger et al., 2016; Veranso‐Libalah et al., 2018): (A) North America; (B) South America; (C) Indo-Burma, also including part of southern and western Yunnan, southernmost Guangxi and Guangdong, and Hainan Island; (D) Sundaland; and (E) Sino-Japanese region, including most of central and southern mainland China, Taiwan, and Ryukyu. All the species in the dataset were coded as present or absent for each of the five areas (Table S4) based on herbarium specimens, literature (Chen, 1984a; Chen, 1984b; Hansen, 1985; Maxwell, 1989; Regalado, 1990; Cellinese, 2002; Cellinese, 2003; Chen and Renner, 2007; Kartonegoro and Veldkamp, 2010; Lin et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2017), and online database (Global Biodiversity Information Facility, http://www.gbif.org). No dispersal scenario and ancestral areas were assumed a priori for the analysis. In RASP we allowed the inferred ancestor to occupy up to two areas, corresponding to the maximum number of areas occupied by any extant species.

One hundred and fifty-one complete chloroplast genomes in Melastomataceae were newly sequenced and assembled in this study (Table S1). All newly obtained genomes are evolutionally conservative and similar to the ones previously published in Melastomataceae (Reginato et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017, Tan et al., 2019). Their genome sizes range from 153,291 to 158,960 bp with an average length of 155,986 bp. A total of 129 genes were annotated, viz. 84 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA, and 8 rRNA, in all chloroplast genomes except that the rpoC1 gene of Sonerila cantonensis Stapf (Liu 510) is pseudogenized. A gene map for the chloroplast genome of Phyllagathis rotundifolia (Jack) Blume is shown in Figure S1 as a representative.

For each of the five partitioning schemes, trees generated by ML and BI analyses were broadly similar irrespective of the model used (GTR+G and GTR+I+G). Generally, BI analyses under selected GTR+I+G model recovered higher supported relationships than under GTR+G model (data not shown). Also, partition3 with best fit GTR+I+G model was favored over other partition schemes in both comparisons of AIC value and Bayes Factors (Table 1). Therefore, we applied partition3 to the final analyses of the two plastid phylogenomic datasets. For BI analyses, all three subsets (LSC, IR, and SSC) in partition3 scheme were analyzed with GTR+I+G (Table 2).

Table 1 Comparison of partitioning strategies used for the Melastomataceae dataset. The best partition scheme selected is indicated in bold.

Table 2 Data characteristics, substitution model selected and used in ML/BI analysis for the four datasets used in this study.

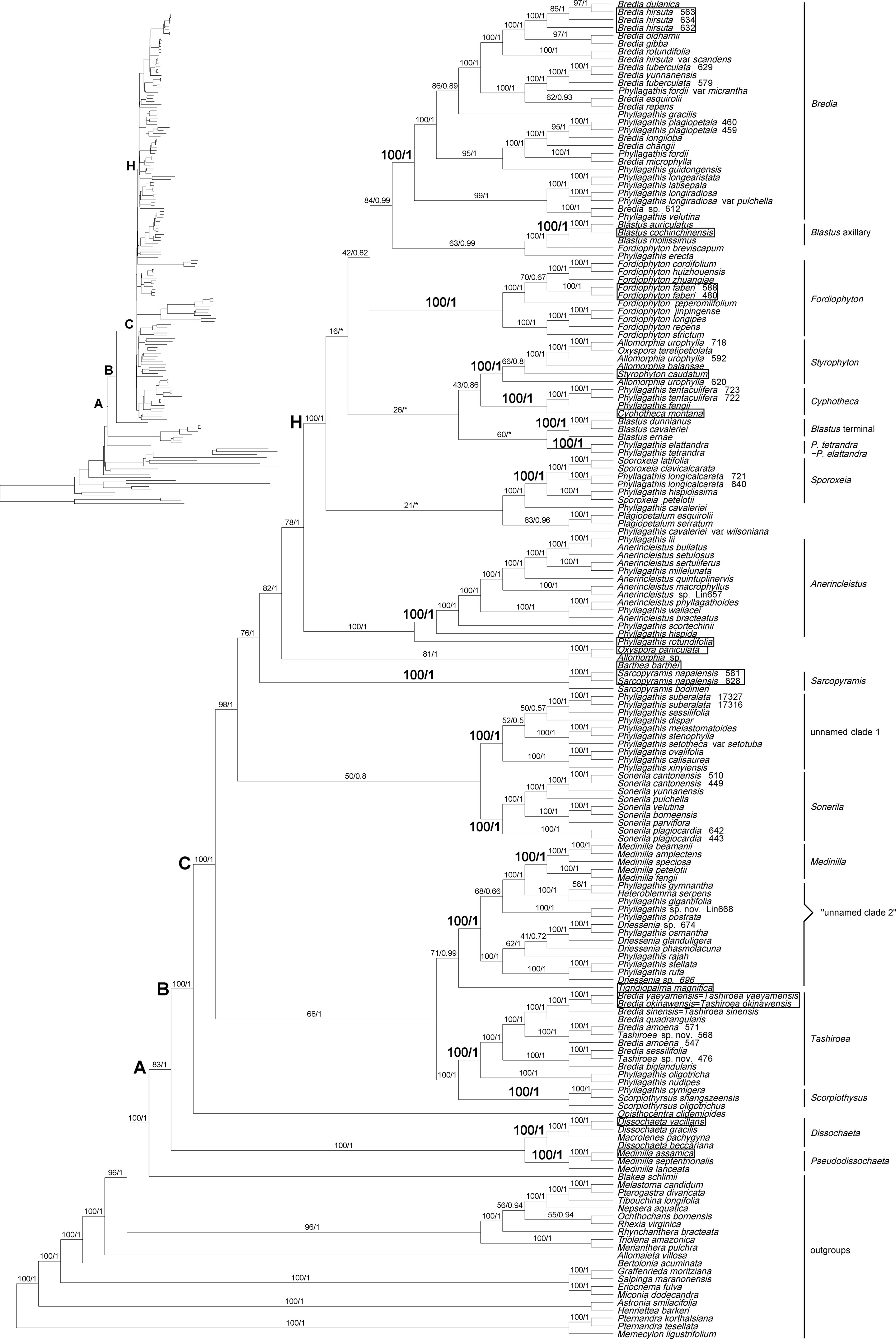

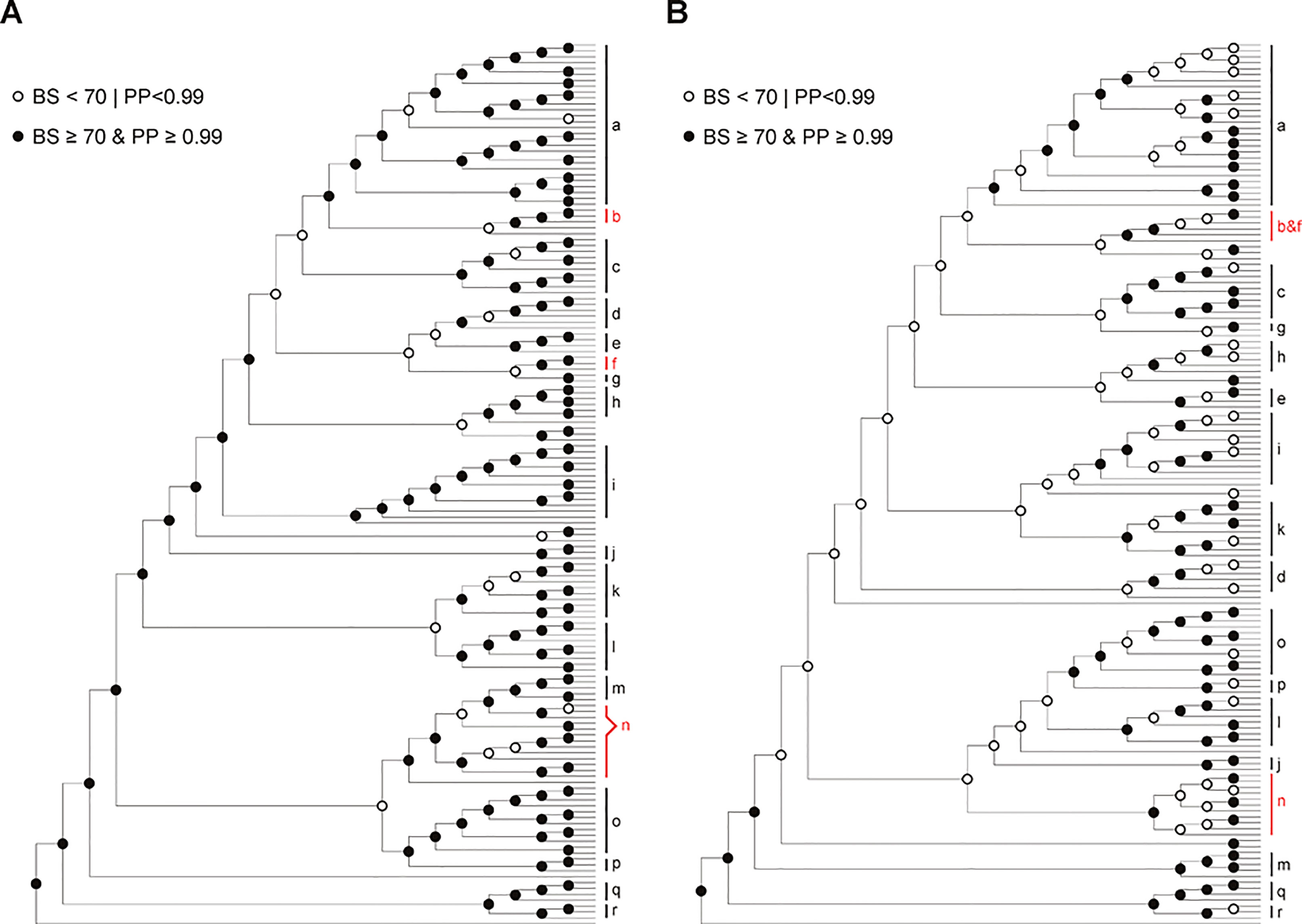

Statistics of sequences sampled in Melastomataceae and Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae phylogenomic datasets are summarized in Table 2. Trees generated by BI and ML analyses had nearly identical topology, except that four/three nodes with weak support in ML analyses collapsed in BI analyses. The ML trees resulting from analyses of the two datasets are shown in Figures 1 and S3, with Bayesian PP and ML bootstrap support values (BS) indicated on the branches. We considered a certain clade as resolved when BS was ≥70%, and PP was ≥0.99.

Analyses of the Melastomataceae dataset revealed that all genera sampled in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, except Ochthocharis Blume, formed a strongly supported clade (PP = 1.00, BS = 83%) (Figure 1). Ochthocharis, previously placed in Sonerileae, showed closer relationship with Rhexieae, Marcetieae, Melastomateae, and Microlicieae instead of other genera in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. Phylogenetic relationships within Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae inferred from the two chloroplast phylogenomic datasets were nearly identical (Figures 1 and S3). The Asian Dissochaeta-Pseudodissochaeta (PP = 1.00, BS = 100%) was recovered as the most basal clade in the complex, followed by a split (PP = 1.00, BS = 100%) between the South American Opisthocentra Hook.f. and a large clade consisting of the remaining Asian species (PP = 1.00, BS = 100%) (Figures 1 and S2). As shown in Figure 1, 17 species clusters were recovered in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. The backbone phylogenies of the complex were only partially supported. Relationships among major lineages in node H remained unresolved (Figure 1). The details of trees based on the nrITS and cp-5 gene datasets were shown in Table 2 and Figures S4 and S5.

Figure 1 Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree of Melastomataceae based on chloroplast genome sequences with 112 genes included shown as a cladogram (phylogram inset). Bootstrap values obtained from ML analyses (left) and Bayesian posterior probabilities resulting from Bayesian inference (BI) (right) are given on the branches. An asterisk denotes a branch collapsed in BI. The types of the genera sampled in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae are indicated with boxes. Clades A, B, C, and H represent the nodes discussed in the text. “Unnamed clade 2” denotes a group of species which comprised the unnamed clade 2 in the nrITS tree (Figure S4).

The dated phylogeny obtained from the BEAST analysis is shown in Figure 2. Divergence time estimates suggested that the Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae complex originated during late Eocene (stem age: 34.78 Mya; 95% HPD: 29.07–40.53 Mya). The most basal clade in the complex, Dissochaeta-Pseudodissochaeta, diverged around 33.96 Mya (late Eocene; 95% HPD: 28.33–39.8 Mya). The subsequent split of the South American Opisthocentra and Asian clades (node C) was estimated to be around 27.79 Mya (Mid Oligocene; 95% HPD: 21.91–33.94 Mya). The Asian clade (node C) began to diversify during early Miocene (crown age: 20.25 Mya; 95% HPD: 15.71–25.24 Mya). Divergence time estimations and respective 95% HPD intervals for nodes of interest were listed in Table 3.

Figure 2 Constrained maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Melastomataceae annotated with estimated divergence time and ancestral range obtained from BEAST and RASP analyses (see Materials and methods). Mean divergence times are shown with their 95% highest posterior density (HPD: green bars). Clades A, B, C, and H represent nodes discussed in the text, whereas node a, b, and c indicate the calibration points. Pie charts represent the area probability inferred for each node. The inset map shows the coding of five biogeographical areas. The present-day distribution is given at the tip for each species. The light and darker vertical bars denote two climatic events: onset of East Asia monsoons and its strengthening to maximum in Miocene (OSEAM, 10–22 Mya) and the Mid Miocene Climate Optimum (MMOC, 15.5–17.2 Mya), respectively. Stars denote two dispersal events (node A, B) of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae from South America to the Old World.

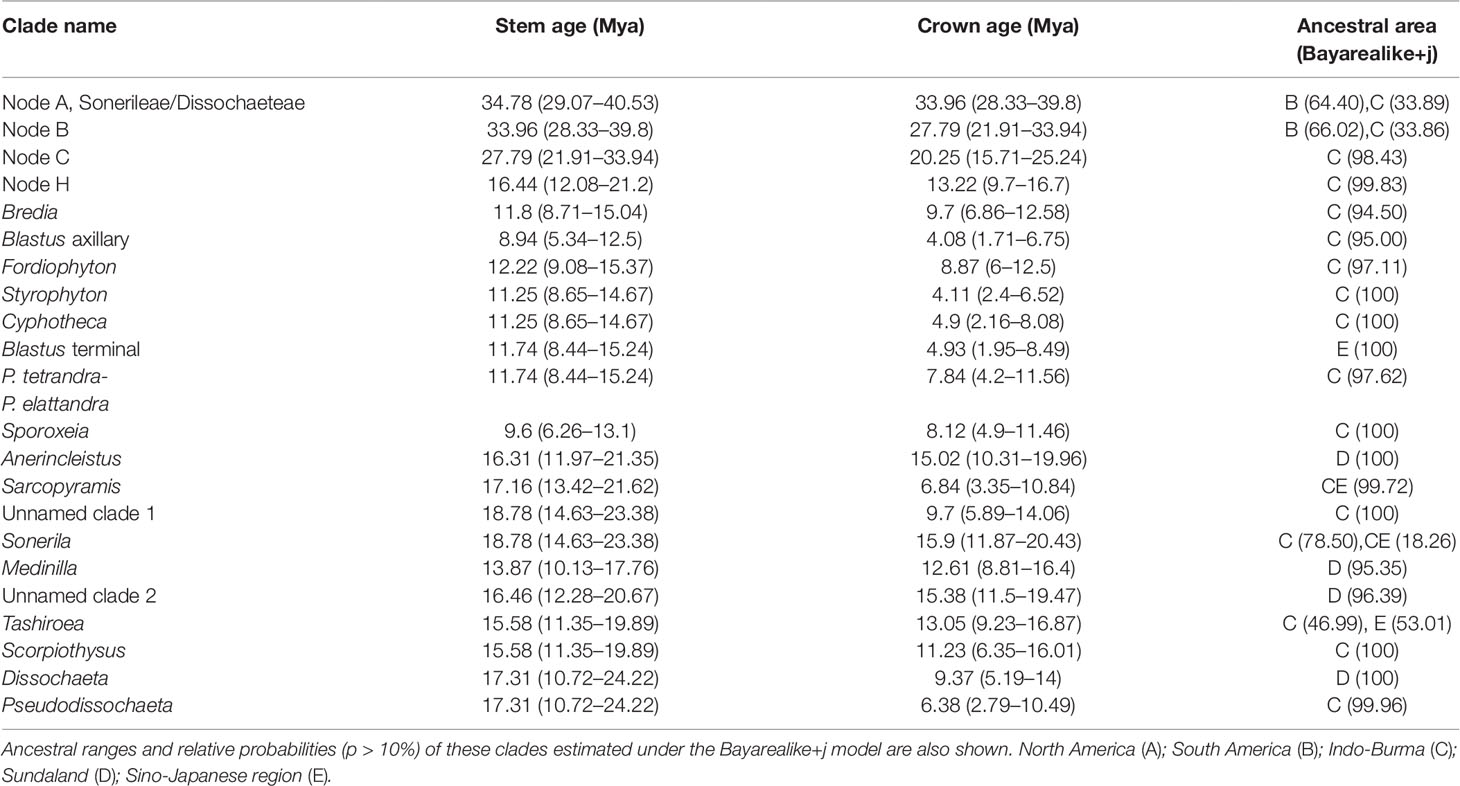

Table 3 Stem and crown median age estimates and 95% highest posterior density (HPD) for Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae and other clades of interest based on BEAST analysis.

Ancestral range reconstruction for Melastomataceae using RASP is shown in Figure 2, with the area probability inferred for each node represented by pie charts. The ancestral areas of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (node A) and the core Asian Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (node C) were estimated to be South America with moderate support (area B, p = 0.64; Figure 2, Table 3) and Indo-Burma with strong support (area C, p = 0.98; Figure 2, Table 3), respectively. Thirty-three dispersal events were detected within Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, of which two were intercontinental dispersals from South America to Asia [33.96 Mya (95% HPD: 28.33–39.8 Mya), node A; 27.79 Mya (95% HPD: 21.91–33.94 Mya), node B] and the remaining were dispersals among different regions of SEA. The most common dispersals in SEA were those from Indo-Burma to Sino-Japanese region (19 out of 31) and from Indo-Burma to Sundaland (5 out of 31). Age estimation showed ongoing dispersals from Indo-Burma to Sino-Japanese region during the past 20 Mya (19.64–0.87 Mya), whereas those from Indo-Burma to Sundaland were relatively ancient, ranging from 17.31 to 9.46 Mya. Ancestral ranges and relative probabilities of clades of interest are given in Table 3.

The phylogenetic tree generated from chloroplast genomic data is generally better resolved than the nrITS tree in terms of relationships both within and among major clades (Figures 1, S3, and S4). As shown in Figure 3, 87% of the nodes in the plastid tree received moderate to strong support comparing to 55% in the nrITS tree. The phylogenetic affiliation of several species, unresolved in the nrITS phylogeny, were recovered by plastid phylogenomic data. For example, Phyllagathis rotundifolia, the type of Phyllagathis, was recovered as the sister group of Anerincleistus clade (Figures 1 and S3). Nevertheless, plastid phylogenomic analyses failed to fully resolve the backbone phylogeny of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (Figures 1 and S3). The weakly supported short internodes following node C and node H, together with our divergence time estimations, indicate putative rapid radiation around early (20.25 Mya) and middle Miocene (13.22 Mya). Therefore, even chloroplast genomic sequences cannot satisfactorily resolve the relationships among clades of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae that evolved through rapid radiation.

Figure 3 Comparison of trees based on chloroplast genomic dataset (A) and nrITS dataset (B). Solid circles and circles denote nodes with strong and weak support (BS ≥ 70 and PP ≥ 0.99 vs. BS < 70 or PP < 0.99) respectively. Clades strongly supported in both trees are indicated with black bars (a, Bredia; c, Fordiophyton; d, Styrophyton; e, Cyphotheca; g, P. tetrandra−P. elattandra; h, Sporoxeia; i, Anerincleistus; j, Sarcopyramis; k, unnamed clade 1; l, Sonerila; m, Medinilla; o, Tashiroea; p, Scorpiothysus; q, Dissochaeta; r, Pseudodissochaeta.), whereas those supported in only one tree are marked with red bars (b, Blastus axillary; f, Blastus terminal; b & f, Blastus; n, unnamed clade 2). Also see Figures S3–S4.

Comparison of the plastid and nrITS trees revealed several strongly supported incongruences regarding the interspecific relationships within some species clusters, e.g. Anerincleistus clade, Bredia clade, Medinilla clade, and Tashiroea clade. The factors commonly invoked as the potential causes of incongruence between plastid and nrITS phylogenies include sampling error, long-branch attraction, incomplete lineage sorting, hybridization, and subsequent introgression (Rieseberg and Soltis, 1991; Soltis and Kuzoff, 1995; Soltis et al., 1996; Wendel and Doyle, 1998). Sampling error can be ruled out as the main factor based on the high PP and BS values of the incongruent topologies (PP = 1.00, BS > 80%). The possibility of long-branch attraction (LBA) is also rejected for two reasons. The data were analyzed using model-based methods that are less sensitive to LBA, besides, no long terminal branches were involved in these incongruences. Ancestral polymorphism may survive recent speciation leading to discordant gene trees at interspecific levels (Wendel and Doyle, 1998; Knowles and Carstens, 2007). Hybridization and the transfer of alleles across the species barrier is also widespread in plants, especially for closely related species. Therefore, both lineage sorting and hybridization could be the cause for interspecific level incongruence.

The plastid genome tree and nrITS tree are congruent in most major lineages of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. Of the 17 major clades recognized in the nrITS tree, 15 were also strongly supported by plastid genomic data (Figures 1, S3, and S4). Incongruences lies in two clades, viz. the Blastus clade and unnamed clade 2. Blastus Lour. is morphologically highly homogeneous and distinct from other genera. This genus, although recovered as monophyletic in the nrITS phylogeny (Figure S4), formed two separate clades in the plastid genome tree corresponding to axillary and terminal inflorescences (Figures 1 and S3). The unnamed clade 2 contains species sampled in Driessenia Korth, Phyllagathis, and Heteroblemma (Blume) Cámara-Leret, Ridd.-Num. & Veldkamp. It was well recognized in nrITS phylogeny (Figure S4) but was revealed to be paraphyletic in the plastid phylogeny (Figures 1 and S3), forming a larger lineage together with the Medinilla clade and two species of Phyllagathis from Vietnam, P. prostrata C. Hansen, and an undescribed new species. However, detection of strongly supported discordance and assessment of the potential causes such as hybridization and introgression are hampered by poor resolution of some parts of the phylogenetic trees.

Chloroplast phylogenomic data together with the even less informative nrITS sequence data failed to fully tackle the phylogenetic relationships within Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. In future analyses, plastid genomic data should be combined with sequence data from multiple nuclear genes to unravel the phylogeny of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae and the underlying evolutionary processes.

Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae exhibits a disjunct distribution between South America and the Old World, with its distribution centered in SEA. Molecular dating and biogeographical analyses indicated a South American origin for this clade during late Eocene (stem age: 34.78 Mya; 95% HPD: 29.07–40.53 Mya; Figure 2, Table 3). Our result agrees with Berger et al. (2016) and Veranso-Libalah et al. (2018) who estimated the age of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae to be 38 and 39.63 Mya respectively based on limited sampling of this clade. Two previous age estimations for this clade, 19 Mya (Renner et al., 2001) and 73 Mya (Morley and Dick, 2003), are not supported with our data.

At the base of Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, an Asian clade Dissochaeta-Pseudodissochaeta (stem age: 33.96 Mya; 95% HPD: 28.33–39.8 Mya) branched off first followed by a split at node B (27.79 Mya; 95% HPD: 21.91–33.94 Mya) between the South American clade Opisthocentra and the remaining Asian species (node C) (Figure 2). Ancestral range estimation indicated two dispersal events from South America to the Old World during late Eocene (33.96 Mya; 95% HPD: 28.33–39.8 Mya) (node A) and Mid Oligocene (27.79 Mya; 95% HPD: 21.91–33.94 Mya) (node B) respectively. Phylogenetic analyses of the cp-5 gene dataset revealed that within node B the South American Opisthocentra, Boyania Wurdack, Phainantha Gleason and the African clade comprising Gravesia Naudin, Calvoa Hook.f., Dicellandra Hook.f., and Amphiblemma Naudin diverged successively, followed by a subsequent split of the Asian clade (node C) (Figure S5). The same pattern is also observed in a most recent phylogenetic study of Bertolonieae and Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (Bacci et al., 2019). These data contradicted the previous view that Gravesia, Calvoa, and Amphiblemma arrived in Africa and Madagascar via long-distance dispersal from SEA (Clausing and Renner, 2001b; Renner et al., 2001; Renner, 2004a; Renner, 2004b), clearly indicating a second dispersal event from South America to Africa and Asia in node B. Based on the inferred age of the two dispersal events [33.96 Mya (95% HPD: 28.33–39.8 Mya) and 27.79 Mya (95% HPD, 21.91–33.94 Mya)], the “Indian Ark” hypothesis (Morley and Dick, 2003) is refuted. There are two alternatives. Direct trans-Atlantic dispersal of the lineages to the Old World is possible via oceanic steeping stones. Also, the basal lineages might have migrated from South America to North America and then entered Eurasia through the North Atlantic land bridge and spread to Africa and SEA during Eocene when the global temperature was still high. The latter hypothesis is supported by Eocene and Miocene Melastomataceae fossils discovered from North America and Europe (Hickey, 1977; Collinson and Pingen, 1992; Wehr and Hopkins, 1994). Both scenarios were proposed for Melastomateae (Veranso-Libalah et al., 2018), another tribe with transtropical disjunction in the family.

The core Asian Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae (node C) began to diversify around early Miocene (crown age: 20.25 Mya; 95% HPD: 15.71–25.24 Mya) in Indo-Burma and dispersed subsequently southward to Malesia and northward to Sino-Japanese (Figure 2). This result is congruent with the findings of previous meta-analyses, which showed that Indo-Burma’s biota (Indochina) had been predominantly characterized by in situ diversification and subsequent emigration since at least the early Miocene (De Bruyn et al., 2014). A series of short internodes with unsatisfactory resolution were observed following node C and node H, indicating the onset of rapid radiation around early (20.25 Mya, 95% HPD: 15.71–25.24 Mya) and middle Miocene (13.22 Mya, 95% HPD: 9.7–16.7 Mya) respectively (Figures 1 and 2). The early Miocene collision of Australia with the eastern margin of Sundaland (Hall, 2009), the onset of East Asia monsoons in early Miocene and its strengthening to maximum in Mid Miocene (Sun and Wang, 2005; Guo et al., 2008) and the Mid Miocene Climate Optimum (MMOC, 15.5–17.2 Mya) resulted in increased topographic complexity, wet and warm climate, and development of widespread evergreen rainforest. These factors might in turn promoted Miocene radiation of Asian Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae in Indo-Burma and their subsequent dispersal into Malesia and Sino-Japanese. The link between warmer and wetter climate and higher speciation was confirmed in a recent study (Kong et al., 2017), showing that global temperature changes and East Asian monsoons had played crucial roles in floristic diversification.

Finally, our analyses estimated a stem age of 13.87 Mya (95% HPD: 10.13–17.76 Mya) for the bird dispersed Medinilla clade (Figure 2). Analyses of the cp-5 gene dataset showed that the Madagascan species of Medinilla were nested within Asian species, branching off after M. fengii-M. petelotii (Figure S5). Therefore, we agree with Renner et al. (2001) and Renner (2004a) that Medinilla reached Madagascar by transoceanic dispersal in Miocene, possibly after 12.61 Mya (95% HPD: 8.82–16.4 Mya), the stem age of M. fengii-M. petelotii (Figure 2).

Of the 23 genera sampled from Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, only Ochthocharis fell out of this clade in the present analyses. As shown in Figure 1, it was close to Rhexieae, Marcetieae Melastomateae, and Microlicieae, conforming to the finding of Veranso-Libalah et al. (2018). Ochthocharis is a distinct genus with an African-Asian distribution, comprising nine species mostly found in the coastal lowland in wet and riverine habitats. Morphologically, it is readily distinguished by the indumentum, the structure of ovary, fruit, and seeds, showing no close resemblance to any other Asiatic genus (Hansen and Wickens, 1981). Ochthocharis should be excluded from Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae based on molecular data. However, a broader sampling of the genus and its close relatives (Rhexieae, Microlicieae, etc.) is still needed to resolve their phylogenetic relationships.

A dozen of major lineages in Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae, well recognized in both nrITS and plastid genomic phylogeny (Figures 1, S3 and S4), are uncovered in this study, which provides some important insights for taxonomy. A comparison of these lineages is shown in Table S5.

Dissochaeta Blume is a genus of woody climbers occurring in SEA. Early authors had established a number of genera closely resembled Dissochaeta, viz. Anplectrum A.Gray, Dalenia Korth., Diplectria (Blume) Rchb., Omphalopus Naudin, Backeria Bakh.f., Neodissochaeta Bakh.f., and Macrolenes Naudin (Reichenbach, 1841; Korthals, 1844; Naudin, 1851; Gray, 1854; Bakhuizen, 1943). All these genera are woody climbers with a scrambling habit. Generic delimitations are mainly based on position of inflorescence, morphology of hypanthium, calyx lobes, and especially stamens (Kartonegoro et al., 2018). Previous molecular phylogenetic study (Clausing and Renner, 2001a) showed that Macrolenes was sister to Diplectria, and Macrolenes-Diplectria to Dissochaeta. Renner et al. (2001) thus synonymized Diplectria and Macrolenes under Dissochaeta. Kartonegoro et al. (2018), emphasizing that Macrolenes differs from Dissochaeta in the axillary inflorescence, the hair cushion domatia on the abaxial surface of leaf blade, long and persistent calyx lobes, and anthers with several basal filiform appendages, preferred to retain Macrolenes as a distinct genus. According to the present study, Macrolenes pachygyna, a species with the above character combination, is nested within species of Dissochaeta. Inclusion of Macrolenes in Dissochaeta is therefore supported.

Pseudodissochaeta Nayar is a small genus of shrubs or small trees endemic to Indochina. Nayar (1969) proposed that this genus is close to Dissochaeta, but differs in the erect habit, connectives hardly produced and ventrally biauriculate, and extra-ovarial chambers descending to the middle or the base of the ovary. However, Chen (1983) considered Pseudodissochaeta as a congener of Medinilla and reduced the former. Chen (1984a) and Chen and Renner (2007) followed this treatment, while Renner et al. (2001) recognized Pseudodissochaeta as a distinct genus. Our phylogenetic analyses included three species previously treated in Pseudodissochaeta, viz. M. assamica (C. B. Clarke) C. Chen (the type of Pseudodissochaeta), M. septentrionalis (W. W. Sm.) H. L. Li, and M. lanceata (Nayar) C. Chen. Pseudodissochaeta was recovered as monophyletic and sister to Dissochaeta, while the rest species sampled in Medinilla formed a clade close to Heteroblemma, Driessenia, and some species of Phyllagathis (Figures 1, S3 and S4). The generic status of Pseudodissochaeta should be retained.

The Anerincleistus clade comprises five species of Phyllagathis and eight species of Anerincleistus, including A. macrophyllus Bakh.f., a species morphologically close to A. hirsutus Korth., the type of this genus. Species of this clade occur in Borneo, Malay Peninsula, and Sumatra. They are similar in having eight isomorphic stamens with minute connective appendages, but are quite diverse in habit, leaf morphology, inflorescence morphology, and capsule morphology (Table S5). Analyses of nrITS sequence data failed to resolve the phylogenetic affiliation of this clade (Figure S4), but chloroplast phylogenomic analyses recovered it as sister to the type of Phyllagathis with strong support (Figures 1 and S3). Based on this result, Phyllagathis should be recircumscribed to include this clade. Nevertheless, this relationship needs to be further tested using nuclear sequence data other than nrITS before formal taxonomic treatment.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses reveal that the type of Bredia is nested in a clade of 21 species, while Tashiroea, a genus previously synonymized in Bredia, falls in another distantly related clade of 10 species (Figures 1, S3, and S4). Both clades are distributed in southern mainland China, Taiwan, and the Ryukyu islands. Phylogenetically, the Tashiroea clade is sister to Scorpiothysus and the Bredia clade is nested in an internally unresolved larger branch with Blastus, Fordiophyton, etc. Morphologically, they differ in a series of characters including indumentum, texture of leaves, and capsule morphology (Table S5). Molecular and morphological evidence confirm that the Bredia and Tashiroea clades represent distantly related lineages. Bredia should be recircumscribed to include the former clade and Tashiroea should be resurrected for the latter.

The Cyphotheca clade comprises the monotypic Cyphotheca, Phyllgathis fengii C. Hansen, and P. tentaculifera C. Hansen. The Sporoxeia clade contains Sporoxeia, P. hispidissima (C. Chen) C. Chen, and P. longicalcarata C. Hansen. Both clades are nested in the internally poorly resolved node H with Bredia clade, Fordiophyton clade, Blastus and Styrophyton clade, etc. (Figures 1, S3, and S4). The two clades, Cyphotheca and Sporoxeia, are morphologically distinct from other clades within node H in the mature ovary crown enclosing an obpyramidal space and 4-horned placental column (Table S5). From each other, they differ in anther morphology (connectives thickened without dorsal appendage vs. connectives dorsally spurred). Although the phylogenetic relationships in node H needs to be further tested, both Cyphotheca and Sporoxeia may have to be expanded to include additional species currently placed in Phyllagathis.

This clade includes the highly homogeneous Scorpiothysus (Yunnan, Guangxi, Hainan), Phyllagathis cymigera C. Chen (Yunnan) (this study), and also P. hainanensis (Merr. & Chun) C. Chen (Hainan) (Zhou et al., 2019). Scorpiothysus differs from P. hainanensis and P. cymigera in the scorpioid inflorescence, but they share general resemblance in leaf, stamen, and capsule morphology (Table S5) some of which were long noticed by Hansen (1992). Phylogenetic analyses consistently placed the Scorpiothysus clade near the Tashiroea clade with strong support (Figures 1, S3 and S4). Morphologically, it differs from the latter clade in 7–9-veined leaves, often scorpioid cymose panicles and anther with 2-setose ventral appendages and is better treated as a separate genus. Scorpiothysus should be expanded to include P. hainanensis and P. cymigera.

This clade consists of ten species of Phyllagathis occurring in southernmost mainland China (6 spp), Vietnam (2 spp), and Borneo (2 spp) (Zhou et al., 2019; this study). The close relationship among some of these allopatric species in Phyllagathis, proposed by Hansen (1992), is confirmed here. Species in this clade are similar in the isomorphic stamens, dorsally spurred connectives, terminal inflorescences, umbellate or cymose (rarely terminal or axillary solitary flower), enlarged ovary crown forming an obpyramidal depression on the top, horned placental column, and thready placenta. The phylogenetic affiliation of unnamed clade 1 is poorly resolved. But this clade showed no close relationship with the type of Phyllagathis in all analyses. If these results reflect the true relationships, species in this clade should be excluded from Phyllagathis and treated as a distinct genus.

All the sequencing data generated in this study has been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers MK994778-MK994928 (complete chloroplast genome sequences) and MN031159-MN031238 (ITS sequences).

RZ and YL designed the experiments. All authors took part in the field work. QZ and JD carried out the experiment. QZ, RZ, and YL analyzed the data. QZ, RZ, and YL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770214) and the Science, Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201707010090) and Chang Hungda Science Foundation of Sun Yat-sen University.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Qiang Fan for providing the materials of Phyllagathis sessilifolia, P. suberalata, Dissochaeta gracilis, and D. vacillans. We are deeply grateful to Dr. David E. Boufford, Dr. Xianchun Zhang, Dr. Bojian Zhong and Dr. Marcelo Reginato for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01477/full#supplementary-material

Bacci, L. F., Michelangeli, F. A., Goldenberg, R. (2019). Revisiting the classification of Melastomataceae: implications for habit and fruit evolution. Bot. J. Linn. Soc 190 (1), 1–24. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/boz006

Bakhuizen van den Brink, R.C., Jr (1943). A contribution to the knowledge of the Melastomataceae occurring in the Malay Archipelago, especially in the Netherlands East Indies. PhD Thesis, Universiteit Utrecht: 1-391. (Reprinted in: Recueil des Travaux Botaniques Néerlandais 40: 1-391. 1947.)

Berger, B. A., Kriebel, R., Spalink, D., Sytsma, K. J. (2016). Divergence times, historical biogeography, and shifts in speciation rates of Myrtales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evo. 95, 116–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.001

Birky, C. W. (1995). Uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes: mechanisms and evolution. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11331–11338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11331

Bouckaert, R., Heled, J., Kühnert, D., Vaughan, T., Wu, C. H., Xie, D. (2014). BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PloS Comput. Boil. 10 (4), e1003537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M., Gabaldón, T. (2009). trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinf. 25 (15), 1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348

Cellinese, N. (1997). Notes on the systematics and biogeography of the Sonerila generic alliance (Melastomataceae) with special focus on fruit characters. Trop. Biodivers. 4, 83–93.

Cellinese, N. (2002). Revision of the genus Phyllagathis Blume (Melastomataceae: Sonerileae) I. The species of Burma, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra. Blumea 47, 463–492.

Cellinese, N. (2003). Revision of the genus Phyllagathis (Melastomataceae: Sonerileae) II. The species in Borneo and Natuna Island. Blumea 48, 69–97. doi: 10.3767/000651903X686060

Chen, C. (1979). A new genus Tigridiopalma C. Chen of Melastomataceae. Acta Bot. Yunnanica 1, 106–108.

Chen, C. (1983). On Medinilla Gaudich. of China in relation to the drift of the Indian Plate. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 21 (4), 416–422.

Chen, C. (1984a). “Melastomataceae,”; in Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae, (Beijing: Science Press), 53, 135–293.

Chen, C., Renner, S. S. (2007). “Melastomataceae,”; in Flora of China, Eds. Wu, P. H., Raven, D. Y., Hong, Z. Y. (Beijing: Science Press; St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press), 13, 360–399.

Clausing, G. (1999).Die Systematik der Dissochaeteae und ihre Stellung innerhalb der Melastomataceae. Ph.D. (Dissertation. Mainz: University of Mainz).

Clausing, G., Meyer, K., Renner, S. S. (2000). Correlations among fruit traits and evolution of different fruits within Melastomataceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc 133, 303–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2000.tb01548.x

Clausing, G., Renner, S. S. (2001a). Evolution of growth form in epiphytic Dissochaeteae (Melastomataceae). Org. Divers. Evol. 1, 45–60. doi: 10.1078/1439-6092-00004

Clausing, G., Renner, S. S. (2001b). Molecular phylogenetics of Melastomataceae and Memecylaceae: implications for character evolution. Am. J. Bot. 88, 486–498. doi: 10.5282/ubm/epub.14627

Clift, P. D., Wan, S., Blusztajn, J. (2014). Reconstructing chemical weathering, physical erosion and monsoon intensity since 25 Ma in the northern South China Sea: a review of competing proxies. Earth-Sci. Rev. 130, 86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.01.002

Cogniaux, A. (1891). "Melastomataceae," in Monographiae Phanerogamarum, vol. 7 . Eds. Candolle, C., Candolle, A. (Paris: SG Masoon), 1–1256.

Collinson, M. E., Pingen, M. (1992). "Seeds of the Melastomataceae from the Miocene of Central Europe," in Palaeovegetational development in Europe. Ed. Kovar-Eder, J. (Austria: Vienna: Museum of Natural History), 129–139.

De Bruyn, M., Stelbrink, B., Morley, R. J., Hall, R., Carvalho, G. R., Cannon, C. H. (2014). Borneo and Indochina are major evolutionary hotspots for Southeast Asian biodiversity. Systematic Biol. 63 (6), 879–901. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu047

Diels, L. (1932). Beitr€age zur Kenntnis der Melastomataceen Ostasiens. Botanische Jahrb€ucher f€ur Systematik Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie 65, 97–119.

Dierckxsens, N., Mardulyn, P., Smits, G. (2017). NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (4), e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955

Dong, W., Liu, J., Yu, J., Wang, L., Zhou, S. (2012). Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PloS One 7 (4), e35071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035071

Doyle, J. J., Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15.

Fritsch, P. W., Almeda, F., Renner, S. S., Martins, A. B., Cruz, B. C. (2004). Phylogeny and circumscription of the near-endemic Brazilian tribe Microlicieae (Melastomataceae). Am. J. Bot. 91 (7), 1105–1114. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.7.1105

Gernhard, T. (2008). The conditioned reconstructed process. J. Theor. Biol. 253 (4), 769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.005

Goldenberg, R., de Fraga, C. N., Fontana, A. P., Nicolas, A. N., Michelangeli, F. A. (2012). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Merianthera (Melastomataceae). Taxon 61 (5), 1040–1056. doi: 10.1002/tax.615010

Gray, A. (1854). "Botany phanerogamia (Part 1)," in United States exploring expedition during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Ed. Wilkes, C. (C. Sherman: Philadelphia).

Guo, Z. T., Sun, B., Zhang, Z. S., Peng, S. Z., Xiao, G. Q., Ge, J. Y. (2008). A major reorganization of Asian climate by the early Miocene. Clim. Past 4 (3), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-4-153-2008.

Hall, R. (2009). Southeast Asia’s changing palaeogeography. Blumea 54, 148–161. doi: 10.3767/000651909X475941

Hansen, C. (1982). New species and combinations in Anerincleistus, Driessenia, Oxyspora and Phyllagathis (Melastomataceae) in Sarawak. Nord. J. Bot. 2 (6), 557–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1983.tb01049.x

Hansen, C. (1985). Taxonomic revision of Driessenia (Melastomataceae). Nord. J. Bot. 5 (4), 335–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1985.tb01663.x

Hansen, C. (1990). Tylanthera (Melastomataceae), a new genus of two species endemic to Thailand. Nord. J. Bot. 9 (6), 631–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1990.tb00552.x

Hansen, C. (1992). The genus Phyllagathis (Melastomataceae): characteristics; delimitation; the species in Indo-China and China. Bull. du Mus. Natl. d’Histoire Naturelle Section B Adansonia Botanique Phytochimie 14, 355–428.

Hansen, C., Wickens, G. E. (1981). A revision of Ochthocharis (Melastomataceae), including Phaeoneuron of Africa. Kew Bull. 36 (1), 13–29.

Heath, T. A., Hedtke, S. M., Hillis, D. M. (2008). Taxon sampling and the accuracy of phylogenetic analyses. J. Syst. Evol. 46 (3), 239–257. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08016

Heckenhauer, J., Paun, O., Chase, M. W., Ashton, P. S., Kamariah, A. S., Samuel, R. (2018). Molecular phylogenomics of the tribe Shoreeae (Dipterocarpaceae) using whole plastid genomes. Ann. Bot. 20, 1–9. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy220

Hickey, J. L. (1977). Stratigraphy and paleobotany of the Golden Valley Formation (Early Tertiary) of Western North Dakota. Memoir 150, Boulder (Colorado, USA: Geological Society of America).

Huelsenbeck, J. P., Ronquist, F. (2001). MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinf. 17 (8), 754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754

Jin, X. H., Tan, Y. H., Quan, R. C. (2018). Taxonomic discoveries bridging the gap between our knowledge and biodiversity. PhytoKeys (94), 1–2. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.94.23887

Kartonegoro, A., Veldkamp, J. F. (2010). Revision of Dissochaeta (Melastomataceae) in Java, Indonesia. Reinwardtia 13 (2), 125–145. doi: 10.14203/reinwardtia.v13i2.2133

Kartonegoro, A., Veldkamp, J. F., Hovenkamp, P., van Welzen, P. (2018). A revision of Dissochaeta (Melastomataceae, Dissochaeteae). PhytoKeys (107), 1–178. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.107.26548

Katoh, K., Standley, D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 (4), 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010

Knowles, L. L., Carstens, B. C. (2007). Delimiting species without monophyletic gene trees. Systematic Biol. 56, 887–895. doi: 10.1080/10635150701701091

Kong, H., Condamine, F. L., Harris, A. J., Chen, J., Pan, B., Möller, M. (2017). Both temperature fluctuations and East Asian monsoons have driven plant diversification in the karst ecosystems from southern China. Mol. Ecol. 26 (22), 6414–6429. doi: 10.1111/mec.14367

Korthals, P. W. (1844). “Bijdrage tot de kennis der Indische Melastomaceae,”; in Verhandelingen over De natuurlijke geschiedenis der Nederlandsche overzeesche bezittingen, Botanie. Ed. Temminck, C. J. (Natuurkundige Commissie: Leiden).

Krasser, F. (1893). “Melastomataceae”. in nat€urlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Eds. Engler, A., Prantl, K. Die. (Leipzig: W Engelmann). III. 130–199.

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S. Y., Guindon, S. (2012). PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29 (6), 1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020

Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinf. 25 (16), 2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Li, H., Durbin, R. (2010). Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinf. 26 (5), 589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698

Lin, C. W., Chen, C. F., Yang, T. Y. A. (2015). Two new taxa of Melastomataceae Trib. Sonerileae: Phyllagathis rajah and Sonerila metallica from Batang Ai, Sarawak, Borneo. Phytotaxa 201, 122–130. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.201.2.2

Lin, C. W., Chen, C. F., Yang, T. Y. A. (2017). Ten new species of Phyllagathis (Trib. Sonerileae, Melastomataceae) from Sarawak, Borneo. Phytotaxa 302, 201–228. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.302.3.1

Lohse, M., Drechsel, O., Bock, R. (2007). OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet. 52 (5-6), 267–274. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0161-y

Ma, P. F., Zhang, Y. X., Zeng, C. X., Guo, Z. H., Li, D. Z. (2014). Chloroplast phylogenomic analyses resolve deep-level relationships of an intractable bamboo tribe Arundinarieae (Poaceae). Systematic Biol. 63 (6), 933–950. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu054

Mathew, J., Yohannan, R., Varghese George, K. (2016). Phyllagathis Blume (Melastomataceae: Sonerileae), a new generic record for India with a new species. Bot. Lett. 163, 175–179. doi: 10.1080/23818107.2016.1166453

Maxwell, J. F. (1989). The genus Anerincleistus Korth. (Melastomataceae). P. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila.141, 29–72.

Maxwell, J. F. (1982). Taxonomic and nomenclatural notes on Oxyspora DC., Anerincleistus Korth., Poikilogyne Baker f., and Allomorphia BL. (Melastomataceae, tribe Oxysporeae). Gard. Bull. Singapore 35 (2), 209–226.

Michelangeli, F. A., Guimaraes, P. J., Penneys, D. S., Almeda, F., Kriebel, R. (2012). Phylogenetic relationships and distribution of new world Melastomeae (Melastomataceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171 (1), 38–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01295.x

Michelangeli, F. A., Ulloa, C. U., Sosa, K. (2014). Quipuanthus, a new genus of Melastomataceae from the foothills of the Andes in Ecuador and Peru. Syst. Bot. 39, 533–540. doi: 10.1600/036364414X680924

Miller, M. A., Pfeiffer, W., Schwartz, T., Miller, M. A., Pfeiffer, W., Schwartz, T. (2010, November). Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In 2010 gateway computing environments workshop (GCE) 1–8 Ieee.

Misof, B., Misof, K. (2009). A Monte Carlo approach successfully identifies randomness in multiple sequence alignments: a more objective means of data exclusion. Systematic Biol. 58 (1), 21–34. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp006

Mittermeier, R. A., Myers, N., Mittermeier, C. G., Robles, G. (1999).Hotspots: Earth’s biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions. SA, Agrupación Sierra Madre, SC: CEMEX.

Morley, R. J., Dick, C. W. (2003). Missing fossils, molecular clocks, and the origin of the Melastomataceae. Am. J. Bot. 90 (11), 1638–1644. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.11.1638

Moyle, R. G., Andersen, M. J., Oliveros, C. H., Steinheimer, F. D., Reddy, S. (2012). Phylogeny and biogeography of the core babblers (Aves: Timaliidae). Systematic Biol. 61, 631–651. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys027

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A., Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nat. 403 (6772), 853. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Naudin, C. (1851). Melastomacearum quae in Museo parisiensi continentur monographicae descriptiones et secundum affinitates distributionis tentamen. Annales des Sciences Naturelles; Botanique, sér. 3, 15, 67–79, 277–283

Nayar, M. P. (1969). Pseudodissochaeta: A new genus of Melastomataceae. J. Bombay. Nat. Hist. Soc. 65, 557–568.

Nee, S., May, R. M., Harvey, P. H. (1994). The reconstructed evolutionary process. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 344 (1309), 305–311. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0068

Ng, W.L., Cai, Y., Wu, W., Zhou, R. (2017). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Melastoma candidum (Melastomataceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 2(1), 242–243. doi:10.1080/23802359.2017.1318680

Niu, Y. T., Jabbour, F., Barrett, R. L., Ye, J. F., Zhang, Z. Z., Lu, K. Q. (2018). Combining complete chloroplast genome sequences with target loci data and morphology to resolve species limits in Triplostegia (Caprifoliaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 129, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.07.013

Nylander, J. A. A., Ronquist, F., Huelsenbeck, J. P., Nieves-Aldrey, J. L. (2004). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of combined data. Systematic Biol. 53, 47–67. doi: 10.1080/10635150490264699

Posada, D., Buckley, T. R. (2004). Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Systematic Biol. 53 (5), 793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304

Posada, D., Crandall, K. A. (1998). Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinf. 14 (9), 817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biol. 67 (5), 901–904. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032

Reginato, M., Neubig, K. M., Majure, L. C., Michelangeli, F. A. (2016). The first complete plastid genomes of Melastomataceae are highly structurally conserved. PeerJ 4, e2715. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2715

Reichenbach, H. G. L. (1841).Der deutsche Botaniker, Erster Band: Das Herbarienbuch, Erklärung des natürlichen Pflanzensystems, systematische Aufzählung, Synonymik und Register der bis jetzt bekannten Pflanzengattungen. Dresden: Arnoldisschen Buchandlung.

Rieseberg, L. H., Soltis, D. E. (1991). Phylogenetic consequences of cytoplasmic gene flow in plants. Evol. Trends Pl. 5, 65–84.

Renner, S. S. (1993). Phylogeny and classification of the Melastomataceae and Memecylaceae. Nord. J. Bot. 13, 519–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1993.tb00096.x

Renner, S. S. (2004a). Multiple Miocene Melastomataceae dispersal between Madagascar, Africa and India. Philos. Trans. R. Soc Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359 (1450), 1485–1494. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1530

Renner, S. S. (2004b). Bayesian analysis of combined chloroplast loci, using multiple calibrations, supports the recent arrival of Melastomataceae in Africa and Madagascar. Am. J. Bot. 91 (9), 1427–1435. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.9.1427

Renner, S. S., Clausing, G., Meyer, K. (2001). Historical biogeography of Melastomataceae: The roles of Tertiary migration and longdistance dispersal. Am. J. Bot. 88, 1290–1300. doi: 10.2307/3558340

Renner, S. S., Meyer, K. (2001). Melastomeae come full circle: biogeographic reconstruction and molecular clock dating. Evol. 55 (7), 1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00654.x

Sauquet, H. (2013). A practical guide to moleculardating. C. R. Palevol 12 (6), 355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.crpv.2013.07.003

Shaw, J., Lickey, E. B., Schilling, E. E., Small, R. L. (2007). Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. Am. J. Bot. 94 (3), 275–288. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.275

Shaw, J., Shafer, H. L., Leonard, O. R., Kovach, M. J., Schorr, M., Morris, A. B. (2014). Chloroplast DNA sequence utility for the lowest phylogenetic and phylogeographic inferences in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare IV. Am. J. Bot. 101 (11), 1987–2004. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400398

Sodhi, N. S., Liow, L. H. (2000). Improving conservation biology research in Southeast Asia. Conserv. Biol. 14 (4), 1211–1212. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99416.x

Sodhi, N. S., Koh, L. P., Brook, B. W., Ng, P. K. (2004). Southeast Asian biodiversity: an impending disaster. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 (12), 654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.006

Soltis, D. E., Johnson, L. A., Looney, C. (1996). Discordance between ITS and chloroplast topologies in the Boykinia group (Saxifragaceae). Syst. Bot. 21, 169–185. doi: 10.2307/2419746

Soltis, D. E., Kuzoff, R. K. (1995). Discordance between nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies in the Heuchera group (Saxifragaceae). Evol. 49, 727–742. doi: 10.2307/2410326

Stamatakis, A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinf. 30 (9), 1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033

Stamatakis, A., Hoover, P., Rougemont, J. (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Systematic Biol. 57 (5), 758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642

Stull, G. W., Duno de Stefano, R., Soltis, D. E., Soltis, P. S. (2015). Resolving basal lamiid phylogeny and the circumscription of Icacinaceae with a plastome-scale data set. Am. J. Bot. 102 (11), 1794–1813. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500298

Sun, X., Wang, P. (2005). How old is the Asian monsoon system?—Palaeobotanical records from China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 222 (3-4), 181–222. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.03.005

Tan, G. W., Han, B. Q., Wang, Y. Q., Li, Z. H., Zhao, Y. Y., Luo, S. (2019). The complete chloroplast genome of Blastus auriculatus (Melastomataceae). Mitochondrial DNA B 4 (1), 1177–1178. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1591183

Tian, J., Pen, L., Zhou, J. C., Tian, X. H., Yi, R. Y., Liu, L., et al. (2016). Phyllagathis guidongensis (Melastomataceae), a new species from Hunan, China. Phytotaxa 263, 58–62. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.263.1.6

Turner, H., Hovenkamp, P., Van Welzen, P. C. (2001). Biogeography of Southeast Asia and the west Pacific. J. Biogeogr. 28 (2), 217–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00526.x

Van Vliet, G. J. C. M., Koek-Noorman, J., Ter Welle, B. J. H. (1981). Wood anatomy, classification and phylogeny of the Melastomataceae. Blumea 27, 463–473.

Veranso-Libalah, M. C., Stone, R. D., Fongod, A. G., Couvreur, T. L., Kadereit, G. (2017). Phylogeny and systematics of African Melastomateae (Melastomataceae). Taxon 66 (3), 584–614. doi: 10.12705/663.5

Veranso-Libalah, M. C., Kadereit, G., Stone, R. D., Couvreur, T. L. (2018). Multiple shifts to open habitats in Melastomateae (Melastomataceae) congruent with the increase of African Neogene climatic aridity. J. Biogeogr. 45 (6), 1420–1431. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13210

Vu, T. C., Rajapaksha, R., Trinh, N. B. O. N., Averyanov, L., Nguyen, T. L. T. (2017). Phyllagathis phamhoangii (Sonerileae, Melastomataceae), a new species from central Vietnam. Phytotaxa 314, 140–144. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.314.1.15

Wangwasit, K., Cellinese, N., Norsaengsri, M. (2010). Phyllagathis nanakorniana (Melastomataceae), a new species from Thailand. Blumea 55, 246–248. doi: 10.3767/000651910X543682

Wehr, W. C., Hopkins, D. Q. (1994). The Eocene orchards and gardens of Republic, Washington. Washington Geology 22 (3), 27–34.

Wen, J., Harris, A. J., Kalburgi, Y., Zhang, N., Xu, Y., Zheng, W. (2018). Chloroplast phylogenomics of the New World grape species (Vitis, Vitaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 56 (4), 297–308. doi: 10.1111/jse.12447

Wendel, J. F., Doyle, J. J. (1998). "Phylogenetic incongruence: Window into genome history and molecular evolution," in Molecular systematics of plants II: DNA sequencing. Eds. Soltis, P. S., Soltis, D. E., Doyle, J. J. (Boston, Dordrecht, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 265–296.

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., Taylor, J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics.In: Innis, M., Gelfand, D., Sninsky, J., White, T.J. (Eds.) PCR Protocols: A guide to methods and applications. (Academic Press,San Diego) pp. 315–332, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1

Woodruff, D. S. (2010). Biogeography and conservation in Southeast Asia: how 2.7 million years of repeated environmental fluctuations affect today’s patterns and the future of the remaining refugial-phase biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 19 (4), 919–941. doi: 10.1007/s10531-010-9783-3

Wyman, S. K., Jansen, R. K., Boore, J. L. (2004). Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinf. 20 (17), 3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352

Yu, Y., Harris, A. J., Blair, C., He, X. (2015). RASP (Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies): a tool for historical biogeography. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 87, 46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.03.008

Zeng, S. J., Huang, G. H., Liu, Q., Yan, X. K., Zhang, G. Q., Tang, G. D. (2016a). Fordiophyton zhuangiae (Melastomataceae), a new species from China based on morphological and molecular evidence. Phytotaxa 282 (4), 259–266. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.122.35260

Zeng, S. J., Zou, L. H., Wang, P., Hong, W. J., Zhang, G. Q., Chen, L. J., et al. (2016b). Preliminary phylogeny of Fordiophyton (Melastomataceae), with the description of two new species. Phytotaxa 247, 45–61. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.247.1.3

Zhang, N., Wen, J., Zimmer, E. A. (2016). Another look at the phylogenetic position of the grape order Vitales: chloroplast phylogenomics with an expanded sampling of key lineages. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 101, 216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.04.034

Zheng, Y., Wiens, J. J. (2015). Do missing data influence the accuracy of divergence-time estimation with BEAST?. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 85, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.02.002

Zhou, Q., Ng, W. L., Wu, W., Zhou, R., Liu, Y. (2017). Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome sequence of Tigridiopalma magnifica (Melastomataceae). Conserv. Genet. Resour. 10, 571–573. doi: 10.1007/s12686-017-0856-4

Zhou, Q. J., Lin, C. W., Dai, J. H., Zhou, R. C., Liu, Y. (2019). Exploring the generic delimitation of Phyllagathis and Bredia (Melastomataceae): A combined nuclear and chloroplast DNA analysis. J. Syst. Evol. 57 (3), 256–267. doi: 10.1111/jse.12451

Zhou, R. C., Zhou, Q. J., Liu, Y. (2018). Bredia repens, a new species from Hunan, China. Syst. Bot. 43, 544–551. doi: 10.1600/036364418X697265

Zou, P., Ng, W. L., Wu, W., Dai, S., Ning, Z., Wang, S. (2017). Similar morphologies but different origins: Hybrid status of two more semi-creeping taxa of Melastoma. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 673. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00673

Keywords: Melastomataceae, Sonerileae, phylogenomics, biogeography, Phyllagathis, plastid genome

Citation: Zhou Q, Lin C-W, Ng WL, Dai J, Denda T, Zhou R and Liu Y (2019) Analyses of Plastome Sequences Improve Phylogenetic Resolution and Provide New Insight Into the Evolutionary History of Asian Sonerileae/Dissochaeteae. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1477. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01477

Received: 19 July 2019; Accepted: 24 October 2019;

Published: 21 November 2019.

Edited by:

Yuannian Jiao, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Xianchun Zhang, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaCopyright © 2019 Zhou, Lin, Ng, Dai, Denda, Zhou and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renchao Zhou, emhyZW5jaEBtYWlsLnN5c3UuZWR1LmNu; Ying Liu, bGlsaXVtcm9zYUAxNjMuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.