94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 04 September 2019

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01067

This article is part of the Research Topic Unifying Insights into the Desiccation Tolerance Mechanisms of Resurrection Plants and Seeds View all 9 articles

Environmental stress, especially water deficiency, seriously limits plant distribution and crop production worldwide. A small group of vascular angiosperm plants termed “resurrection plants,” possess desiccation tolerance (DT) to withstand dehydration and to recover fully upon rehydration. In recent years, with the rapid development of life science in plants different omics technologies have been widely applied in resurrection plants to study DT. Boea hygrometrica is native in East and Southeast Asia, and Haberlea rhodopensis is endemic to the Balkans in Europe. They are both resurrection pants from Gesneriaceae family. This paper reviews recent advances in transcriptome and metabolome, and discusses the differences and similarities of DT features between both species. Finally, we believe we provide novel insights into understanding the mechanisms underlying the acquisition and evolution of desiccation tolerance of the resurrection plants that could substantially contribute to develop new approaches for agriculture to overcome water deficiency in future.

Water is of crucial importance for the life on our planet. Water availability affects plants distribution in nature and crop yields in cultivated areas. Most plants encounter water stress at certain stages of their life cycles. In order to survive, plants have evolved various mechanisms and adaptation strategies. For example, plants enhance their water-holding capacity through stomatal regulation and leaf specific structure, enhance water-absorbing capacity by promoting root growth, improve osmotic regulation capacity by accumulating osmoprotectants, and reduce oxidative damages by regulation of scavenging enzymes and agents. Although these mechanisms are usually effective against moderate drought stresses, they can’t help plants to cope with severe and persistent desiccation.

Desiccation tolerance (DT) in angiosperm vegetative tissues is a rare phenomenon—only a small group of vascular plants termed “resurrection plants,” evolved uniquely to tolerate the loss of more than 90% of their water content, and to recover rapidly after rehydration (Moore et al., 2009; Dinakar et al., 2012; Gaff and Oliver, 2013). About 300 species have been reported to tolerate severe desiccation. Geographically, they are distributed predominantly in the southern hemisphere—in Africa, America, and Australia (Alpert and Oliver, 2002; Gaff and Oliver, 2013). However, DT species could be found in the northern hemisphere, too. Interestingly enough and with lack of sufficient scientifically sound explanations so far, the only resurrection angiosperm plants, found in Europe and Asia belong to one and the same family—Gesneriaceae (Shen et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2012; Mitra et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Djilianov et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). The resurrection species in Europe—Haberlea rhodopensis, Ramonda myconii, R. serbica, and R. nathaliae are phylogenetically relatively close and live in more or less similar environments (Petrova et al., 2015; Rakić et al., 2015; Fernández-Marín et al., 2018). The Asia endemic resurrection species, including Boea hygrometrica (also named Dorcoeras hygrometricum), B. clarkeana, B. crassifolia, Paraboea rufescens, and Paraisometrum mileense, are phylogenetically separated from European clade according to molecular phylogenetic analyses (Shen et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012; Mitra et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Djilianov et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016).

Recent advances in genome sequencing and various “omics” technologies have greatly facilitated the discovery of DT-related genes and improved the understanding of DT molecular mechanisms. Transcriptome and metabolome studies were also performed in B. hygrometrica (Xiao et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2018) and H. rhodopensis (Gechev et al., 2013; Moyankova et al., 2014; Mladenov et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018). B. hygrometrica is distributed in East and Southeast Asia, and H. rhodopensis is endemic to the Balkans in Europe (Mitra et al., 2013; Petrova et al., 2015). They both prefer shady slopes and limestone rocks and are subjected to frequent cycles of drying and rehydration under natural conditions, but spend dry state in different seasons. B. hygrometrica remains desiccated during winter while H. rhodopensis withstands desiccation during the dry periods of warm Mediterranean summer. Thus, it would be interesting to know if their DT mechanisms share common features and origin. Although evidences are still limited, this review will elaborate on the existing data in an attempt to better understand the common and specific mechanisms underlying DT of these Gesneriaceae resurrection plants.

Photosynthesis is the most important photo-chemical reaction in plants, and it is seriously disrupted by dehydration (Pinheiro and Chaves, 2011). Like other homoiochlorophllous DT species (including the Ramonda spp.), B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis can keep their photosynthetic apparatus intact, maintain chlorophyll pigments–protein complexes stable, retain major pigment contents, and employ conserved and novel antioxidant enzymes/metabolites to minimize the possible oxidative damage (Deng et al., 2003; Georgieva et al., 2005; Georgieva et al., 2007; Georgieva et al., 2009; Giarola et al., 2017). In parallel with the above studies, transcriptome data and protein studies showed that the expression of the major photosynthesis-related genes and proteins related to the subunits of photosystem I (PS I) and photosystem II (PS II), light-harvesting complexes II and I, cytochrome b6/f complex and electron transport were down-regulated, while many other chloroplastic genes and proteins were up-regulated to protect the system during dehydration in both B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis (Jiang et al., 2007; Sarvari et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018). For example, early light-inducible proteins (ELIPs) transcripts were up-regulated in response to dehydration (Gechev et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2015) to protect the photosynthetic machinery from photooxidative damage by preventing the accumulation of free chlorophyll, binding pigments and preserving the chlorophyll–protein complexes. Combining prompt fluorescence and adsorption spectroscopy, in H. rhodopensis we found that the cyclic electron flow (CEF) and PSII maintain significant activity till severe dehydration stage—opposite to the steep decrease of linear electron flow (LEF) (Mladenov et al., 2015). Transcriptome data showed that ferredoxin and NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit genes are up-regulated during dehydration (Liu et al., 2018). Together, these data suggest that CEF is activated to generate more ATP and balance the ATP/NAPDH ratio in dehydrated H. rhodopensis. Similarly, in B. hygrometrica CEF around PS I is maintained during moderate dehydration, however, LEF around PS II was found to be dramatically decreased (Tan et al., 2017).

Dehydration impacts cellular functions and viability, compromising the macromolecular structures—in particular, the membranes and proteins (Garrido et al., 2012). Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) and heat shock proteins (HSPs) are two major classes of protective proteins. Various roles have been attributed to LEA proteins: stabilization and protection of proteins, nucleic acids, and cell membranes, decrease of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ions, and contribution together with sugars for glassy state formation (Tunnacliffe et al., 2010). LEA genes have been reported to be induced during dehydration in many resurrection plants including B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis (Liu et al., 2009; Rodriguez et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). Furthermore, LEA genes (BhLEA1 and BhLEA2) from B. hygrometrica have been shown to contribute to protein stabilization in drought-stressed transgenic tobacco plants thus improving their tolerance (Liu et al., 2009).

HSPs are a class of molecular chaperones that bind to and prevent aggregation of unfolded proteins and also help in maintaining protein structure under denaturing conditions, such as desiccation. Transcripts that encode HSP70s, DNAJs/HSP40s, sHSPs and heat shock factors (HSFs) accumulate to high levels during dehydration in B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis (Gechev et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018). BhDNAJC2 from B. hygrometrica is the first and, so far, the only reported dehydration-inducible DNAJ/HSP40 protein in resurrection plants, and it plays a significant role in plant resistance to stresses, as shown in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Chen et al., 2015). Interestingly enough, some of H. rhodopensis LEAs and HSPs were abundant under well-watered conditions, suggesting that the transcriptome and proteome of this plant species may be primed to some extent for DT (Gechev et al., 2013).

Protein homeostasis is central for normal cellular function, but often disturbed under abiotic stress conditions. Protein quality control systems recruit specific factors and pathways to regulate protein refolding or misfolded proteins degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), cytosol, and other cell compartments (Ron and Walter, 2007). Transcriptomic data revealed that protein folding was enriched among up-regulated genes in desiccated B. hygrometrica and at the same time, marker genes of unfolded protein stress in the ER and chaperone genes in cytosolic protein quality control were induced by dehydration (Zhu et al., 2015). Furthermore, a key regulator of ER quality control, bZIP60 was activated via mRNA alternative splicing during dehydration (Wang et al., 2017). Similarly, in H. rhodopensis, two key regulators [ER lumen protein-retaining receptor 2 (ERD2) and ER oxidoreductin-1 (ERO1)] were up-regulated in late stage of dehydration, reflecting the activation of unfolded protein response to mitigate drought-induced protein-unfolding (Liu et al., 2018). These are the only two reports of protein-quality control in resurrection plants so far, but they could be a good background for elucidation of this process, to uncover their fundamental role in conferring DT in other species.

Autophagy is a major form of programmed cell death but also plays an important role in anti-cell death, facilitating precursor recycling and energy supply under stressed conditions (Patel et al., 2006). It also serves as one of the two major mechanisms of protein degradation (Yue and Calderwood, 2011). Autophagy was initially found to play a major role in desiccation tolerance in yeast and the resurrection grass Tripogon loliiformis (Ratnakumar et al., 2011; Williams, 2015). Similarly, we have confirmed that autophagy genes were also enriched among desiccation-induced transcripts in B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis (Zhu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018). These observations suggest a common role of autophagy for DT in both yeast and plants.

Transcripts related to DNA repair were found to be induced during dehydration only in H. rhodopensis (Liu et al., 2018). Especially, the genes of nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway were activated, indicating the importance of DNA repair to maintain genome integrity during severe dehydration. No NER related transcripts with significantly changed expression levels were found in B. hygromtrica transcriptomic data (Xiao et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2015). There is no report on the activation of NER under desiccation in other resurrection plants so far, thus the potential role of NER for DT needs to be further studied.

Accumulation of soluble sugars under stress is a common feature and resurrection plants make no exception. Sucrose is considered the most accumulated sugar in higher resurrection plants (Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Oliver et al., 2010), possibly acting as a water replacement molecule which contributes in membrane and protein structure stabilization or cytoplasm vitrification of desiccated tissue, and as potential energy supply during rehydration (Abdalla et al., 2010; Vicré et al., 2010; Griffiths et al., 2014). In our case, H. rhodopensis and B. hygrometrica plants increase the accumulation of sucrose during desiccation, same as Ramonda spp. and many other resurrection plants (Müller et al., 1997; Whittaker et al., 2001; Peters et al., 2007; Djilianov et al., 2011; Dinakar and Bartels, 2013; Gechev et al., 2013; Moyankova et al., 2014; Mladenov et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2018).

In addition to the significant role of sucrose, it is important to outline the role of raffinose in H. rhodopensis and B. hygrometrica, in conferring cellular protection and preventing crystallization of sucrose during drying, as in many other DT angiosperms (Müller et al., 1997; Farrant et al., 2007). In H. rhodopensis, R. nathaliae and R. myconi, the level of this compound is high at normal conditions and only slightly changed in desiccated plants, suggesting its potential role for priming the plant stress response (Müller et al., 1997; Djilianov et al., 2011; Gechev et al., 2013; Moyankova et al., 2014). On the other hand, in B. hygrometrica, raffinose family oligosaccharides accumulate significantly and genes related to their biosynthesis were induced during dehydration (Wang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012), which coincide with the need of priming for DT in this plant.

Apart from those primary metabolites, many secondary metabolites, especially antioxidants, were found to change during dehydration in many resurrection plants including B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis (Moyankova et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2018). For example, α-tocopherol, the lipid soluble antioxidant that protects plant cells against oxidative stresses, was increased at fully desiccated stage in both H. rhodopensis and B. hygrometrica as in other resurrection plants—e.g. Sporobolus stapfianus (Oliver et al., 2011). In agreement with the metabolomics data, transcripts encoding enzymes in α-tocopherol biosynthesis including homogentisate phytyltransgerase1 (HPT1) and tocopherol cyclase (VTE1) were up-regulated during dehydration both in B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis. (Zhu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018).

Several metabolites have been detected to change their abundance in response to dehydration in B. hygrometrica so far. The ascorbic acid content increased to high levels in rehydrated plants of B. hygrometrica, albeit the expression patterns of genes related to ascorbic acid metabolism and oxidation–reduction are complex (Zhu et al., 2015). Glutaric acid accumulation was also in line with desiccation tolerance in B. hygrometrica (Sun et al., 2018). The accumulation of these metabolites is positively correlated with the transcript abundance of the related genes. Furthermore, the global unbiased metabolomics combined with the microarray data analysis also suggests a role of putative regulators involved in ubiquitination and ABA signal transduction in the acquisition of rapid desiccation tolerance in B. hygrometrica (Sun et al., 2018). On the other hand, the glycoside myconoside and some phenolic acids were high under normal conditions and indicated their importance for priming of H. rhodopensis to withstand severe desiccation (Moyankova et al., 2014). Total phenols, glutathione, β-aminoisobutyric acid, β-sitosterol increased up to several times at later stages of desiccation of H. rhodopensis (Djilianov et al., 2011; Moyankova et al., 2014). These difference highlights the possibility of species-specific regulation of metabolism, although it is not clear whether all of them are involved in DT mechanism.

Studies on endogenous plant hormones in H. rhodopensis (Djilianov et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018) showed that jasmonic acid, along and even earlier than abscisic acid (ABA), provide a triggering signal to unlock the response to desiccation. High levels of salicylic acid, early stages’ accumulation of ethylene and dynamic changes of cytokinins and auxins actively participate in the dehydration response. Most of the genes, associated with the metabolism of the list and other compounds have been found to be a subject of reprograming at the late stage of desiccation that defines the DT in H. rhodopensis (Liu et al., 2018). In B. hygrometrica, KEGG pathways of biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites and biosynthesis of plant hormones and GO terms of jasmonic acid biosynthetic process, ethylene biosynthetic process and abscisic acid mediated signaling are enriched among differentially expressed genes in response to dehydration (Zhu et al., 2015), although the composition of secondary metabolites and contents of hormones has not been studied in detail.

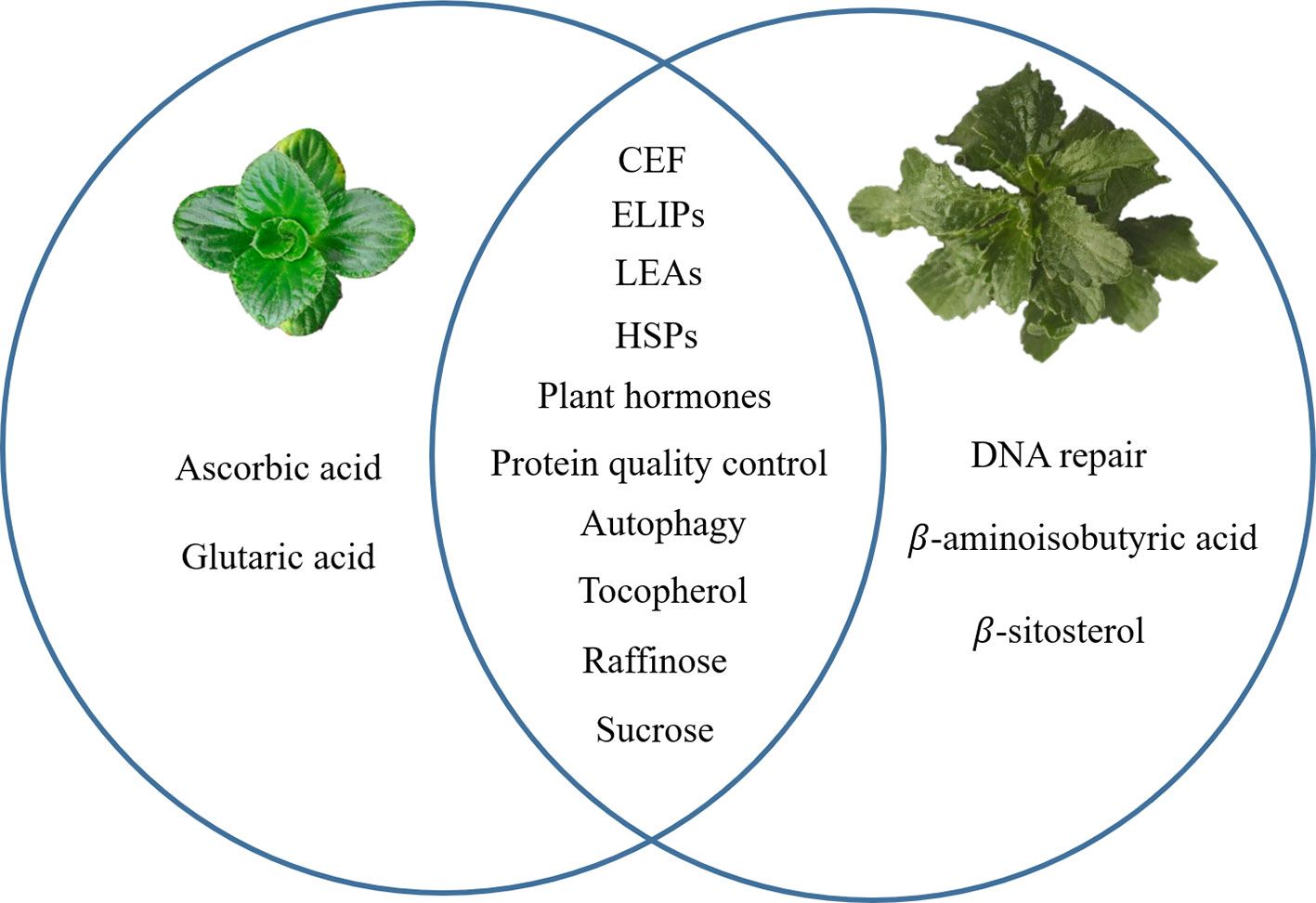

Recent progress in transcriptomes and metabolomes allowed us to compare the DT between B. hygrometrica and H. rhodopensis. When similar mechanisms were studied in both species, common responses include LEA and HSPs proteins, protein quality control, sugar metabolism, α-tocopherol accumulation, autophagy and plant hormone metabolism and signaling. Specific features such as ascorbic acid and glutaric acid accumulation at desiccation were found only in B. hygrometrica, while DNA repair and increase of β-aminoisobutyric acid and β-sitosterol—in H. rhodopensis (Figure 1). These data could infer the highly complex mechanisms that contribute to the ability of Gesneriaceae resurrection plants to withstand desiccation. Even in one botanical family, the DT has been independently evolved in these species, probably due to their diverse phylogeographic history.

Figure 1 A graphical summary for common and specific mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in Boea hygrometrica and Haberlea rhodopensis. The left circle represents the specific mechanisms of B. hygrometrica; the right circle represents the specific mechanisms of H. rhodopensis; the intersection of the two circles represents common mechanisms.

XD designed the frame of the manuscript. JL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DM wrote sections of the manuscript. DD and XD revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31600155), Scientific Research Project of Facility Horticulture Laboratory of Universities in Shandong (No. 2018YY034), China-Bulgari’s Inter-Governmental S&T Cooperation Project [14-10], and Bulgarian National Science Fund (DNTS/China/01/7).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Jayeeta Mitra for English edition of the manuscript.

Abdalla, K. O., Baker, B., Rafudeen, M. S. (2010). Proteomic analysis of nuclear proteins during dehydration of the resurrection plant Xerophyta viscosa. Plant Growth Regul. 62 (3), 279–292. doi: 10.1007/s10725-010-9497-2

Alpert, P., Oliver, M. J. (2002). Drying Without Dying, in Desiccation and survival in plants. Eds. Black, M., Pritchard, H. W. (Wallingford, UK: CABI Press), 3–45. doi: 10.1079/9780851995342.0003

Chen, S., Zhang, Z., Wang, B., Zhu, Y., Gong, Y., Sun, D., et al. (2015). Cloning, expression and functional analysis of a J-domain protein-coding gene, BhDNAJC2, from the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica. Chin. Bull. Bot. 50 (2), 180–190. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1259.2015.00180

Deng, X., Hu, Z.-A., Wang, H.-X., Wen, X.-G., Kuang, T.-Y. (2003). A comparison of photosynthetic apparatus of the detached leaves of the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica with its non-tolerant relative Chirita heterotrichia in response to dehydration and rehydration. Plant Sci. 165 (4), 851–861. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00284-X

Dinakar, C., Djilianov, D., Bartels, D. (2012). Photosynthesis in desiccation tolerant plants: energy metabolism and antioxidative stress defense. Plant Sci. 182, 29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.01.018

Dinakar, C., Bartels, D. (2013). Desiccation tolerance in resurrection plants: new insights from transcriptome, proteome and metabolome analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 482. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00482

Djilianov, D., Ivanov, S., Moyankova, D., Miteva, L., Kirova, E., Alexieva, V., et al. (2011). Sugar ratios, glutathione redox status and phenols in the resurrection species Haberlea rhodopensis and the closely related non-resurrection species Chirita eberhardtii. Plant Biol. 13 (5), 767–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00436.x

Djilianov, D. L., Dobrev, P. I., Moyankova, D. P., Vankova, R., Georgieva, D. T., Gajdošová, S., et al. (2013). Dynamics of endogenous phytohormones during desiccation and recovery of the resurrection plant species Haberlea rhodopensis. J. Plant Growth Regul. 32 (3), 564–574. doi: 10.1007/s00344-013-9323-y

Djilianov, D., Moyankova, D., Mladenov, P. (2016). The Mediterranean: a cradle of the resurrection plants in Europe. Phytologia Balcanica 22 (2), 141–147.

Farrant, J. M., Brandt, W., Lindsey, G. G. (2007). An overview of mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in selected angiosperm resurrection plants. Plant Stress 1 (1), 72–84. doi: 10.1038/nature00976

Fernández-Marín, B., Neuner, G., Kuprian, E., Laza, J. M., Garcia-Plazaola, J. I., Verhoeven, A. (2018). First evidence of freezing tolerance in a resurrection plant: insights into molecular mobility and zeaxanthin synthesis in the dark. Physiol. Plant. 163 (4), 472–489. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12694

Gaff, D. F., Oliver, M. (2013). The evolution of desiccation tolerance in angiosperm plants: a rare yet common phenomenon. Funct. Plant Biol. 40 (4), 315–328. doi: 10.1071/FP12321

Garrido, C., Paul, C., Seigneuric, R., Kampinga, H. H. (2012). The small heat shock proteins family: the long forgotten chaperones. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44 (10), 1588–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.022

Gechev, T. S., Benina, M., Obata, T., Tohge, T., Sujeeth, N., Minkov, I., et al. (2013). Molecular mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in the resurrection glacial relic Haberlea rhodopensis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 70 (4), 689–709. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1155-6

Georgieva, K., Maslenkova, L., Peeva, V., Markovska, Y., Stefanov, D., Tuba, Z. (2005). Comparative study on the changes in photosynthetic activity of the homoiochlorophyllous desiccation-tolerant Haberlea rhodopensis and desiccation-sensitive spinach leaves during desiccation and rehydration. Photosynth. Res. 85 (2), 191–203. doi: 10.1007/s11120-005-2440-0

Georgieva, K., Szigeti, Z., Sarvari, E., Gaspar, L., Maslenkova, L., Peeva, V., et al. (2007). Photosynthetic activity of homoiochlorophyllous desiccation tolerant plant Haberlea rhodopensis during dehydration and rehydration. Planta 225 (4), 955–964. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0396-8

Georgieva, K., Roding, A., Buchel, C. (2009). Changes in some thylakoid membrane proteins and pigments upon desiccation of the resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis. J. Plant Physiol. 166 (14), 1520–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.03.010

Giarola, V., Hou, Q., Bartels, D. (2017). Angiosperm plant desiccation tolerance: hints from transcriptomics and genome sequencing. Trends Plant Sci. 22 (8), 705–717. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.05.007

Griffiths, C. A., Gaff, D. F., Neale, A. D. (2014). Drying without senescence in resurrection plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5 (3), 36. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00036

Huang, W., Yang, S. J., Zhang, S. B., Zhang, J. L., Cao, K. F. (2012). Cyclic electron flow plays an important role in photoprotection for the resurrection plant Paraboea rufescens under drought stress. Planta 235 (4), 819–828. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1544-3

Ingram, J., Bartels, D. (1996). The Molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 377–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.377

Jiang, G., Wang, Z., Shang, H., Yang, W., Hu, Z., Phillips, J., et al. (2007). Proteome analysis of leaves from the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica in response to dehydration and rehydration. Planta 225 (6), 1405–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0449-z

Li, A., Wang, D., Yu, B., Yu, X., Li, W. (2014). Maintenance or collapse: responses of extraplastidic membrane lipid composition to desiccation in the resurrection plant Paraisometrum mileense. PLoS One 9 (7), e103430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103430

Liu, J., Moyankova, D., Lin, C. T., Mladenov, P., Sun, R. Z., Djilianov, D., et al. (2018). Transcriptome reprogramming during severe dehydration contributes to physiological and metabolic changes in the resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis. BMC Plant Biol. 18 (1), 351. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1566-0

Liu, X., Wang, Z., Wang, L., Wu, R., Phillips, J., Deng, X. (2009). LEA 4 group genes from the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica confer dehydration tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Sci. 176 (1), 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.09.012

Liu, X., Challabathula, D., Quan, W., Bartels, D. (2019). Transcriptional and metabolic changes in the desiccation tolerant plant Craterostigma plantagineum during recurrent exposures to dehydration. Planta 249 (4), 1017–1035. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-3058-8

Mitra, J., Xu, G., Wang, B., Li, M., Deng, X. (2013). Understanding desiccation tolerance using the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica as a model system. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 446. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00446

Mladenov, P., Finazzi, G., Bligny, R., Moyankova, D., Zasheva, D., Boisson, A. M., et al. (2015). In vivo spectroscopy and NMR metabolite fingerprinting approaches to connect the dynamics of photosynthetic and metabolic phenotypes in resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis during desiccation and recovery. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 564. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00564

Moore, J. P., Le, N. T., Brandt, W. F., Driouich, A., Farrant, J. M. (2009). Towards a systems-based understanding of plant desiccation tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 14 (2), 110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.11.007

Moyankova, D., Mladenov, P., Berkov, S., Peshev, D., Georgieva, D., Djilianov, D. (2014). Metabolic profiling of the resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis during desiccation and recovery. Physiol. Plantarum. 152 (4), 675–687. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12212

Müller, J., Sprenger, N., Bortlik, K., Boiler, T., Wiemken, A. (1997). Desiccation increases sucrose levels in Ramonda and Haberlea, two genera of resurrection plants in the Gesneriaceae. Physiol. Plantarum. 100, 153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb03466.x

Oliver, M. J., Cushman, J. C., Koster, K. L. (2010). Dehydration tolerance in plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 639, 3–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-702-0_1

Oliver, M. J., Guo, L., Alexander, D. C., Ryals, J. A., Wone, B. W., Cushman, J. C. (2011). A sister group contrast using untargeted global metabolomic analysis delineates the biochemical regulation underlying desiccation tolerance in Sporobolus stapfianus. Plant Cell. 23 (4), 1231–1248. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082800

Patel, S., Caplan, J., Dinesh-Kumar, S. P. (2006). Autophagy in the control of programmed cell death. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 (4), 391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.007

Peters, S., Mundree, S. G., Thomson, J. A., Farrant, J. M., Keller, F. (2007). Protection mechanisms in the resurrection plant Xerophyta viscosa (Baker): both sucrose and raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) accumulate in leaves in response to water deficit. J. Exp. Bot. 58 (8), 1947–1956. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm056

Petrova, G., Moyankova, D., Nishii, K., Forrest, L., Tsiripidis, I., Drouzas, A. D., et al. (2015). The European paleoendemic Haberlea rhodopensis (Gesneriaceae) has an oligocene origin and a pleistocene diversification and occurs in a long-persisting refugial area in southeastern Europe. Int. J. Plant Sci. 176 (6), 499–514. doi: 10.1086/681990

Pinheiro, C., Chaves, M. M. (2011). Photosynthesis and drought: can we make metabolic connections from available data? J. Exp. Bot. 62 (3), 869–882. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq340

Rakić, T., Gajić, G., Lazarević, M., Stevanović, B. (2015). Effects of different light intensities, CO2 concentrations, temperatures and drought stress on photosynthetic activity in two paleoendemic resurrection plant species Ramonda serbica and R. nathaliae. Environ. Exp. Bot. 109, 63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.08.003

Ratnakumar, S., Hesketh, A., Gkargkas, K., Wilson, M., Rash, B. M., Hayes, A., et al. (2011). Phenomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal that autophagy plays a major role in desiccation tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biosyst. 7 (1), 139–149. doi: 10.1039/C0MB00114G

Rodriguez, M. C., Edsgard, D., Hussain, S. S., Alquezar, D., Rasmussen, M., Gilbert, T., et al. (2010). Transcriptomes of the desiccation-tolerant resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum. Plant J. 63 (2), 212–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04243.x

Ron, D., Walter, P. (2007). Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol Cell Biol. 8 (7), 519. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199

Sarvari, E., Mihailova, G., Solti, A., Keresztes, A., Velitchkova, M., Georgieva, K. (2014). Comparison of thylakoid structure and organization in sun and shade Haberlea rhodopensis populations under desiccation and rehydration. J. Plant Physiol. 171 (17), 1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.07.015

Shen, Y., Tang, M.-J., Hu, Y.-L., Lin, Z.-P. (2004). Isolation and characterization of a dehydrin-like gene from drought-tolerant Boea crassifolia. Plant Sci. 166 (5), 1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.12.025

Sun, R.-Z., Lin, C.-T., Zhang, X.-F., Duan, L.-X., Qi, X.-Q., Gong, Y.-H., et al. (2018). Acclimation-induced metabolic reprogramming contributes to rapid desiccation tolerance acquisition in Boea hygrometrica. Environ. Exp. Bot. 148, 70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.01.008

Tan, T., Sun, Y., Luo, S., Zhang, C., Zhou, H., Lin, H. (2017). Efficient modulation of photosynthetic apparatus confers desiccation tolerance in the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica. Plant. Cell Physiol. 58 (11), 1976–1990. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx140

Tunnacliffe, A., Hincha, D. K., Leprince, O., Macherel, D. (2010). LEA proteins: versatility of form and function, in Dormancy and Resistance in Harsh Environments. Eds. Lubzens, E., Cerda, J., Clark, M. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 91–108. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-12422-8_6

Vicré, M., Farrant, J. M., Driouich, A. (2010). Insights into the cellular mechanisms of desiccation tolerance among angiosperm resurrection plant species. Plant. Cell Environ. 27 (11), 1329–1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01212.x

Wang, B., Du, H., Zhang, Z., Xu, W., Deng, X. (2017). BhbZIP60 from resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica is an mRNA splicing-activated endoplasmic reticulum stress regulator involved in drought tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 245. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00245

Wang, L., Shang, H., Liu, Y., Zheng, M., Wu, R., Phillips, J., et al. (2009). A role for a cell wall localized glycine-rich protein in dehydration and rehydration of the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica. Plant Biol. 11 (6), 837–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00187.x

Wang, Y.-Z., Liang, R.-H., Wang, B.-H., Li, J.-M., Qiu, Z.-J., Li, Z.-Y., et al. (2010). Origin and phylogenetic relationships of the old world Gesneriaceae with actinomorphic flowers inferred from ITS and trnL-trnF sequences. Taxon 59 (4), 1044–1052. doi: 10.1002/tax.594005

Wang, Z., Zhu, Y., Wang, L., Liu, X., Liu, Y., Phillips, J., et al. (2009). A WRKY transcription factor participates in dehydration tolerance in Boea hygrometrica by binding to the W-box elements of the galactinol synthase (BhGolS1) promoter. Planta 230 (6), 1155–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1014-3

Wang, Z., Liu, Y., Wei, J., Deng, X. (2012). Cloning and expression of a gene encoding a raffinose synthase in the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica. Chin. Bull. Bot. 47 (1), 44–54. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1259.2012.00044

Whittaker, A., Bochicchio, A., Vazzana, C., Lindsey, G., Farrant, J. (2001). Changes in leaf hexokinase activity and metabolite levels in response to drying in the desiccation-tolerant species Sporobolus stapfianus and Xerophyta viscosa. J. Exp. Bot. 52 (358), 961–969. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.358.961

Williams, B., Njaci, I., Moghaddam, L., Long, H., Dickman, M. B., Zhang, X., et al. (2015). Trehalose accumulation triggers autophagy during plant desiccation. PLoS Genet. 11 (12), e1005705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005705

Xiao, L., Yang, G., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Zhao, S., Ji, Z., et al. (2015). The resurrection genome of Boea hygrometrica: a blueprint for survival of dehydration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (18), 5833–5837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505811112

Yue, Z., Calderwood, S. K. (2011). Autophagy, protein aggregation and hyperthermia: a mini-review. Int. J. Hyperthermia 27 (5), 409–414. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2011.552087

Zhang, D., Zhou, S., Zhou, H., Liu, F., Yang, S., Ma, Z. (2016). Physiological response of Boea clarkeana to dehydration and rehydration. Chin. J. Ecol. 35 (1), 72–78. doi: 10.13292/j.1000-4890.201601.010

Zhang, Z., Wang, B., Sun, D., Deng, X. (2013). Molecular cloning and differential expression of sHSP gene family members from the resurrection plant Boea hygrometrica in response to abiotic stresses. Biologia 68 (4), 651–661. doi: 10.2478/s11756-013-0204-4

Keywords: Boea hygrometrica, Haberlea rhodopensis, desiccation tolerance, transcriptome, metabolome, Gesneriaceae, resurrection plant

Citation: Liu J, Moyankova D, Djilianov D and Deng X (2019) Common and Specific Mechanisms of Desiccation Tolerance in Two Gesneriaceae Resurrection Plants. Multiomics Evidences. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1067. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01067

Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 07 August 2019;

Published: 04 September 2019.

Edited by:

Jill Margaret Farrant, University of Cape Town, South AfricaReviewed by:

Jose Ignacio Garcia-Plazaola, University of the Basque Country, SpainCopyright © 2019 Liu, Moyankova, Djilianov and Deng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dimitar Djilianov, ZF9kamlsaWFub3ZAYWJpLmJn; Xin Deng, ZGVuZ0BpYmNhcy5hYy5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.