- 1Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2The New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Ltd., Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand

- 3AXA Chair of Biosphere and Climate Impacts, Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment and Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment, Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot, United Kingdom

- 4Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Global climate change is expected to increase drought duration and intensity in certain regions while increasing rainfall in others. The quantitative consequences of increased drought for ecosystems are not easy to predict. Process-based models must be informed by experiments to determine the resilience of plants and ecosystems from different climates. Here, we demonstrate what and how experimentally derived quantitative information can improve the representation of stomatal and non-stomatal photosynthetic responses to drought in large-scale vegetation models. In particular, we review literature on the answers to four key questions: (1) Which photosynthetic processes are affected under short-term drought? (2) How do the stomatal and non-stomatal responses to short-term drought vary among species originating from different hydro-climates? (3) Do plants acclimate to prolonged water stress, and do mesic and xeric species differ in their degree of acclimation? (4) Does inclusion of experimentally based plant functional type specific stomatal and non-stomatal response functions to drought help Land Surface Models to reproduce key features of ecosystem responses to drought? We highlighted the need for evaluating model representations of the fundamental eco-physiological processes under drought. Taking differential drought sensitivity of different vegetation into account is necessary for Land Surface Models to accurately model drought responses, or the drought impacts on vegetation in drier environments may be over-estimated.

Introduction

Soil water deficit is the main environmental driver that limits aboveground net primary production in land vegetation (Webb et al., 1983; Zeppel et al., 2014), and induces vegetation mortality on all six vegetated continents and for most biomes across the globe (Potts, 2003; Allen et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2010; Anderegg et al., 2012; Choat et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2013). By affecting physiological (e.g., leaf gas exchange, canopy conductance), structural (e.g., leaf area, root length, mass distribution) and biogeographic (e.g., forest composition and species distribution) processes at the plant and community levels, extreme drought is expected to cause regional losses of biodiversity and biomass (Phillips et al., 2009) with impacts on ecosystem function and the terrestrial carbon sink (Pitman, 2003; Bonan, 2008; Phillips et al., 2010).

Modeling the quantitative consequences of increased drought for forest ecosystems is challenging (McDowell et al., 2011), and requires unraveling the interaction between drought and plant gas exchange at different time scales, and in different ecosystems with different degrees of adaptation to drought. Reliable model prediction of drought impacts on forest ecosystems must be based on the analysis of observations to identify key traits that promote plant resistance to drought, and process-based modeling to include realistic representation of the ecophysiological mechanisms relating plant gas exchange to water availability and transport. In addition, we need to understand how drought impacts vary among ecosystems. The drought impacts on different ecosystems depend on the drought duration, magnitude, and spatial extent, vegetation type-specific responses to drought at different time scales, and mechanisms affecting the drought resistance and resilience of different vegetation types (Pasho et al., 2011; Vicente-Serrano et al., 2013). Different terrestrial ecosystems are reported to differ in their sensitivity to drought (Knapp and Smith, 2001; Zeppel et al., 2014). For example, conifer forests were found to withstand drought impacts better than broadleaf forests in Canada (Kljun et al., 2006) and in Europe during the extremely dry year of 2003 (Granier et al., 2007). However, the present generation of ecosystem models embody a simplistic representation of drought responses of these ecophysiological properties and processes across forest ecosystems, which makes it difficult to predict the likely extent of drought-induced changes in the function of forest ecosystems.

Current state-of-the-art Earth System models (ESMs), which include dynamic global vegetation models (DGVMs) (Prentice and Cowling, 2013) coupled to physical representations of land-atmosphere exchanges of energy, water vapor and CO2 (land surface models, LSMs), make widely divergent predictions of drought effects (Prentice et al., 2015). This divergence is partly due to the lack of an established, empirically supported method for the representation of drought effects on plants (Egea et al., 2011). Process-based modeling of the drought impacts on plants and ecosystems must be informed by experiments, which can help us to understand underlying processes. Model evaluation and improvement must include the use of experimental observations, theory to explain the observations, quantitative parameterizations to describe the theory, and model simulations to test the impacts of environmental variables (Bonan et al., 2014; Prentice et al., 2015; see a model-data integration process by Walker et al., 2014). Although thousands of experiments have been done to study the drought responses of plants, relatively few provide information in the quantitative manner required to develop model representations. In particular, work is needed (1) to directly determine how different aspects of plant function respond to experimentally imposed drought and (2) to analyze experimental results in a theoretical framework, suitable for inclusion in ecosystem models.

In particular, current ecosystem models differ greatly in the ways in which they represent drought effects on photosynthesis (Medlyn et al., 2016). Many models simulate the drought effect on photosynthesis in a rough way simply by reducing the slope of the relationship between stomatal conductance (gs) and net carbon assimilation rate (An) (Egea et al., 2011), in a similar way for all plant function types (PFTs). Another specific issue is that the apparent maximum carboxylation rate (Vcmax) has usually been attributed to a PFT as a single value, or as a single-valued function of environmental drivers (Haxeltine and Prentice, 1996). It is not known whether the method is adequate to capture the drought response, but there is a strong case to expect that it is not, and it does not account for either differences among species and/or ecosystems of different climatic origins, or for mechanisms of plant acclimation to drought. Emerging modeling evidence points to the importance of representing both stomatal and non-stomatal responses to drought in models (e.g., Egea et al., 2011; De Kauwe et al., 2015b). However, the modeling approach in current LSMs lacks a functionally realistic representation of drought responses of gs and Vcmax, unless the experimentally based and PFT-specific representations of the drought responses of gs and Vcmax have been implemented.

Recently, there are increasingly more model-experiment synthesis studies to improve the representation of photosynthetic responses to environmental drivers in large-scale vegetation models (e.g., Medlyn et al., 2011; Prentice et al., 2014; De Kauwe et al., 2015a,b). In this review, we highlight recent studies which analyze the experimental data of both the short- and long-term drought responses of leaf gas exchange across species of contrasting climatic origins, and which aim at improving the representation of experimentally based and PFT based stomatal and non-stomatal response functions to soil water stress in LSMs and DGVMs.

Which Photosynthetic Processes Are Affected Under Short-Term Drought?

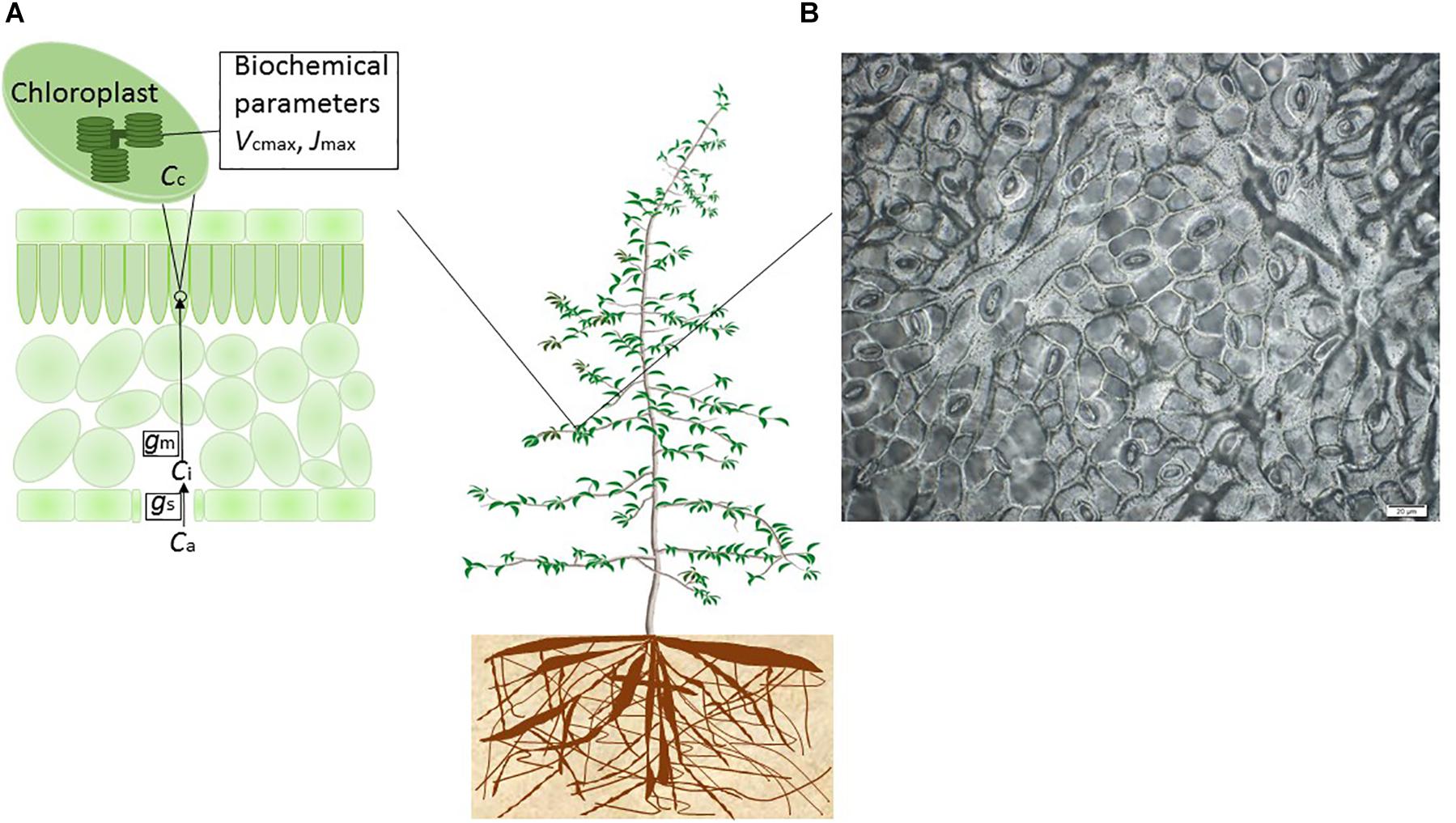

Leaf An is mainly driven by light, temperature and intercellular CO2, as represented in the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry leaf-level photosynthesis model for C3 plants (Farquhar et al., 1980). Intercellular CO2, in turn, is co-determined by gs and An. Reduction of gs is one of the foremost, short-term, leaf-scale physiological responses both to atmospheric vapor pressure deficit (the driving force of transpiration, E) and soil water deficit. CO2 and water vapor exchange are strongly coupled through stomata, because gs regulates both the CO2 uptake for photosynthesis, and the loss of water vapor by transpiration (Cowan, 1977) (Figure 1). A variant of the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry model was coupled to the empirical Ball–Berry stomatal conductance model (Ball et al., 1987; Collatz et al., 1991) in the land component of climate models already in the mid-1990s, in order to estimate gross primary production on a more mechanistic basis than before (Bonan, 1995; Cox et al., 1998). This or other similar formulations are now used widely in state-of-the-art ESMs. Research efforts have also been devoted specifically to the implementation of different modeling approaches for stomatal conductance (e.g., Bonan et al., 2014; De Kauwe et al., 2015a).

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of the model-experiment synthesis framework to quantify and model the differential sensitivities of leaf gas exchange to drought. (A) During photosynthesis, the CO2 flux from the air (ambient CO2 concentration, Ca) to intercellular air spaces (intercellular CO2 concentration, Ci) through stomata is limited by stomatal conductance (gs). The CO2 flux from the intercellular space to the chloroplast site (CO2 concentration at the chloroplast, Cc) is limited by mesophyll conductance (gm). The non-stomatal limitation on photosynthesis was attributed to drought effects on gm, the actual maximum rate of CO2 consumption by RuBP carboxylation by Rubisco (Vcmax) and the actual maximum electron transport rate (Jmax). (B) An impression of the leaf epidermis of E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis was produced using clear nail polish, which then was mounted for applications of microphotography of the leaf surface. The microscope (Olympus BX53, Olympus America Inc.) was interfaced with a digital camera at ×40 magnification. Photo: Shuang-Xi Zhou.

Although photosynthesis accounts for the largest CO2 flux from the atmosphere into ecosystems and is the driving process for terrestrial ecosystem function (Bernacchi et al., 2013), the fundamental component processes of plant gas exchange are still incompletely represented in global models, notably in the area of drought responses, and photosynthetic and morphological acclimation generally (including acclimation to drought) (Prentice and Cowling, 2013). In ecosystem models, drought stress may act either by increasing the marginal water use efficiency, which depends on the ratio of CO2 concentration inside and outside the leaf (Ci/Ca ratio); by reducing Vcmax and/or the maximum rate of electron transport – Jmax (apparent values implicitly assuming infinite gm); or both (Figure 1). Accurate model prediction of drought impacts on vegetation and global carbon and water cycles requires realistic representation of photosynthetic processes at the leaf level (Baldocchi, 1997; Egea et al., 2011; Verhoef and Egea, 2014).

Stomatal behavior is expected to be related to the marginal carbon cost of water loss (λ = ∂A/∂E) (Cowan, 1977; Cowan and Farquhar, 1977; Berninger and Hari, 1993). Cowan and Farquhar (1977) postulated that for any given amount of total water available for transpiration in a period of time, the leaf can achieve the maximum CO2 uptake if it adjusts leaf scale conductance in the way that the derivative of An with respect to the rate of transpiration per unit area of leaf (∂A/∂E) is maintained constant throughout the period (Cowan, 1977). This criterion amounts to saying that a plant with a given water availability regulates stomata to ensure maximal carbon gain per unit water loss in a finite period of time. Therefore, the constancy of ∂A/∂E is viewed as an optimality hypothesis (Cowan, 1977; Cowan and Farquhar, 1977). It has also been suggested that the rate at which water stress is imposed might influence the response of ∂A/∂E to water stress (Hall and Schulze, 1980). The theoretical analysis of Mäkelä et al. (1996) further predicted that the marginal water cost of carbon (1/λ) should decline exponentially with decreased soil moisture, and that the rate of decline should increase according to the probability of rain.

Medlyn et al. (2011) and Prentice et al. (2014) have proposed re-interpretations of widely used empirical models of stomatal conductance, in terms of optimization theory. Medlyn et al. (2011) derived a simple expression that is a good approximate solution of the Cowan-Farquhar optimization problem, and demonstrated its predictive power for a range of species. The single parameter of the Medlyn et al. (2011) optimal model for stomatal behavior – the stomatal sensitivity parameter (g1) – is inversely proportional to λ, and thus can be used directly to test the predictions by Mäkelä et al. (1996) (Héroult et al., 2013; see a conceptual modeling framework in Zhou et al., 2013). Prentice et al. (2014) introduced a different derivation of the same expression, with further empirical support, based on the alternative hypothesis that plants minimize the sum of the unit costs (carbon expended per unit assimilation) of CO2 uptake and water loss. Different expressions again have been presented by Sperry et al. (2016), Wolf et al. (2016), and Dewar et al. (2018) based on the optimization criterion that plants maximize carbon gain by minimizing carbon costs associated with hydraulic failure.

Besides the stomatal resistance on CO2 diffusion from the atmosphere to the intercellular air spaces of the leaves, there is now known to be a considerable mesophyll resistance to CO2 diffusion from the substomatal cavity to the carboxylation sites in the chloroplasts (Figure 1). In other words, there is a mesophyll conductance (gm) which is not infinite and can significantly limit the CO2 availability and thus the assimilation rate. gm has been shown to play an important role in determining photosynthetic responses to environmental drivers including temperature and CO2 (e.g., Niinemets et al., 2011; Evans and von Caemmerer, 2013). Photosynthesis is reported to be limited by decreased gm – together with gs – in the initial stages of drought (Bota et al., 2004; Flexas et al., 2004, 2007, 2008, 2012; Grassi and Magnani, 2005; Egea et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2014). There has been controversy on the magnitude of the gm effect on photosynthesis under mild to moderate drought conditions, largely due to the methodological issues on estimation of the intercellular or the chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc; Figure 1) (Pinheiro and Chaves, 2011). In addition, there is controversy on whether gm should be included in ecosystem models, and how to include gm in ecosystem models (Rogers et al., 2017). Some recent studies suggested that the decrease of gm with increasing soil water deficit could contribute as much as the decrease of gs to the reduction of An under drought (e.g., Flexas et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014). However, far less is known on the environmental regulation and interspecific differences in gm compared to gs.

As plant water status worsens, there is a further possibility that drought impedes enzyme activity and photosynthetic capacity. In other words, there can be directly drought-induced biochemical limitations on the activity of Rubisco (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) and the regeneration capacity of RuBP (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate) (Kanechi et al., 1996; Tezara et al., 1999; Castrillo et al., 2001; Parry et al., 2002; Tezara et al., 2002; Thimmanaik et al., 2002; Grassi and Magnani, 2005). Drought-induced decrease of Rubisco activity is associated with down-regulation of the activation state of the enzyme (e.g., by de-carbamylation and/or binding of inhibitory sugar phosphates). In the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry model (Farquhar et al., 1980), the Vcmax and Jmax (apparent values implicitly assuming infinite gm) are the two key metabolic parameters limiting photosynthetic capacity (Figure 1). Varying among leaves within a plant, between plants, among species and seasonally (e.g., Wilson et al., 2000; Xu and Baldocchi, 2003), Vcmax plays an important role in linking the carbon fluxes between the leaves and the atmosphere and thus in governing plant productivity and resource use efficiency (Long et al., 2006) and determining large-scale fluxes of CO2 between vegetation and the atmosphere (Bonan et al., 2011, 2012). The trigger for decreased Rubisco activity is reported to depend on the severity and/or the duration of the stress imposed (Flexas et al., 2006). Ecosystem models commonly assign fixed values of Vcmax per PFT, but there is no consistency in the values assigned among different models and, in any case, this approach neglects most of the field-observed variation in Vcmax (Kattge et al., 2009; Bonan et al., 2011, 2012; Groenendijk et al., 2011). Recent studies have suggested that it is necessary to represent the effects of climate change on Vcmax in models to predict its impact on net primary production (e.g., Bernacchi et al., 2013; Galmés et al., 2013).

It is generally thought that with the increase of drought intensity and/or duration, biochemical limitations on photosynthesis should eventually come to dominate over diffusional (stomatal and mesophyll) limitations (see a review by Lawlor and Tezara, 2009). However, there has been a good deal of debate about the relative importance of photosynthetic limitations of diffusive and biochemical origin, in the context of drought (e.g., Grassi and Magnani, 2005). Reasons for controversy include the use of different measures of drought, the imposition of drought at different rates in experiments, different applied intensities and duration of drought, different experimental designs and growth conditions, and different species with different physiological and structural sensitivities and adaptations to drought.

Interspecific Variation in the Short-Term Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Drought Responses Among Species From Different Hydro-Climates

The drought responses of different species are likely to depend not only on drought duration and intensity, but also on the species-specific degree of adaptation to the soil water conditions in their native habitat. It is well documented that plants from dry climates can operate better than plants from wet climates down to severe soil water deficits (e.g., Sperry, 2000). However, studies have highlighted that mesic and xeric forest ecosystems are equally vulnerable to drought-induced mortality, based on their functional hydraulic limits (Choat et al., 2012), implying that plants from drier or wetter environments possess some degree of adaptation to the soil conditions encountered in their native habitat. Indeed, xeric species were reported to keep stomata open and maintain photosynthesis down to lower water potential values than mesic species (e.g., Zhou et al., 2014). It is reasonable to assume that this feature of plants from dry climates is adaptive, important for their function under field conditions and shaping their potential geographic ranges (Engelbrecht et al., 2007). Differential drought adaptations among species are presumed to underpin their different levels of sensitivity, resistance, and resilience to soil water deficits (Chaves et al., 2003; McDowell et al., 2008), and differential effectiveness of physiological mechanisms of drought tolerance in the face of decreasing water potential (Engelbrecht et al., 2007). The wide variation of drought adaptations among species is likely to be fundamentally important in determining their different degrees of vulnerability to biomass loss and mortality (Ciais et al., 2005; Adams et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2010).

Under a drier and hotter climate, the intra- and inter-specific variation in plant traits may provide an important contribution to plants’ resistance to drought, with responses characteristic of plants from dry environments promoting persistence and adaptation, reducing risk of mortality and improving chance of survival (Yachi and Loreau, 1999; Clark et al., 2012). Understanding how these effects vary among species from contrasting climates is key to predicting the large-scale consequences of drought on different communities and ecosystems. Very few published experiments have systematically tested how the various components of plant drought response vary across species from contrasting hydro-climates. The response of the stomatal sensitivity parameter (g1) of the Medlyn stomatal optimality model (Medlyn et al., 2011) to soil water deficit is expected a priori to differ among plant functional types and species of different geographical origins (Medlyn et al., 2011; Héroult et al., 2013). Meanwhile, Vcmax is expected to be higher in plant species from drier climates (Prentice et al., 2014), in compensation for reduced stomatal conductance. There is also significant variability in the Rubisco specificity factor among closely related C3 higher plants, which is associated mainly with temperature and water availability (Galmés et al., 2005). Zhou et al. (2013, 2014) fitted quantitative models for species of different origin of climate and PFT membership in their differential gs and Vcmax responses to soil water potential – providing functions that potentially could represent these responses in process-based models.

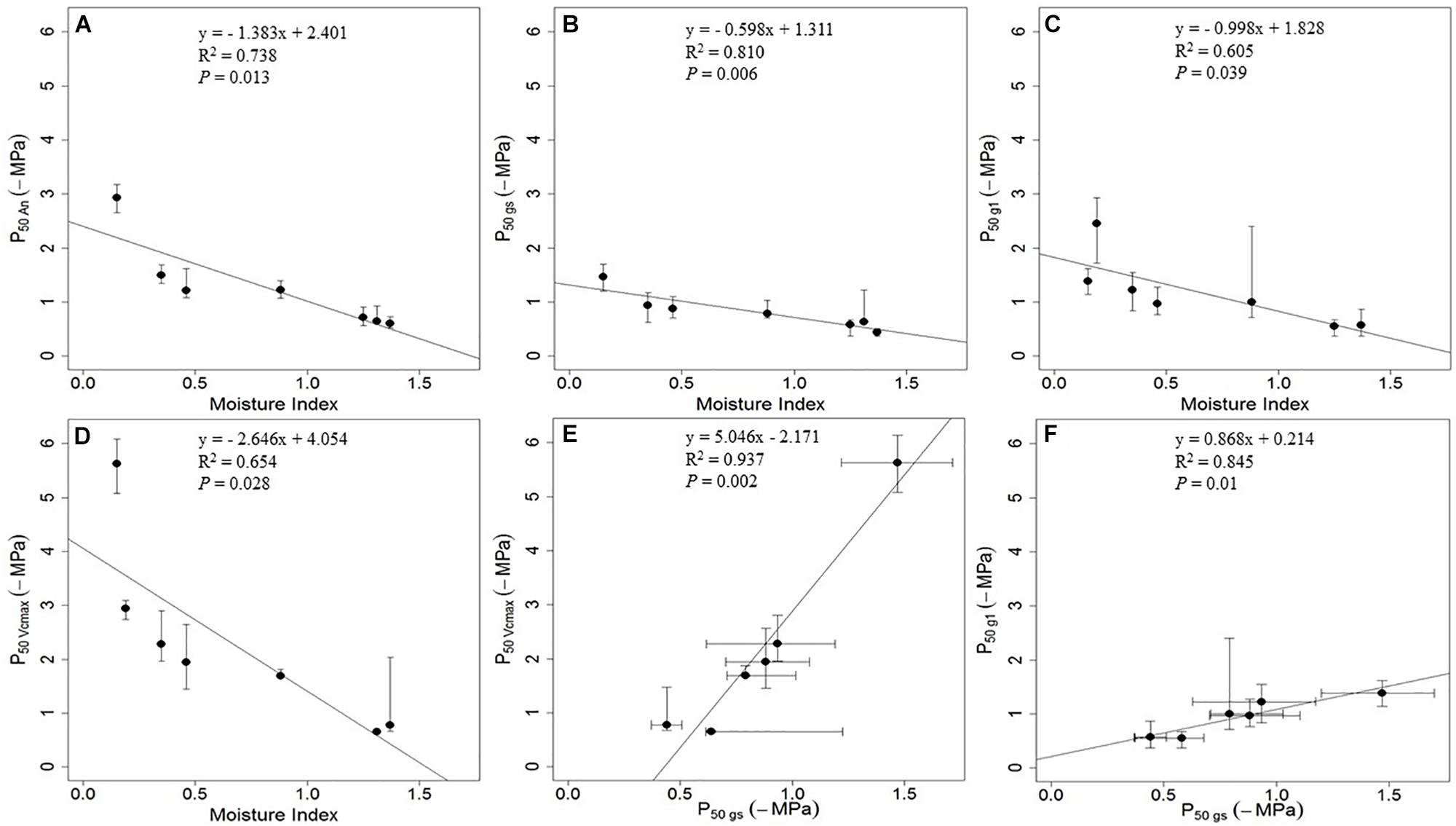

The decline rates of stomatal and hydraulic function with decreasing water potential levels were reported to be coordinated across species of different climate of origin (Choat et al., 2012; Klein, 2014; Manzoni, 2014; Martin-StPaul et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; but see Lamy et al., 2014). In this review, we calculated the pre-dawn leaf water potential at which 50% loss of full functions occurred (P50, -MPa) for the photosynthetic parameters reported in Zhou et al. (2014) – 50% loss of net carbon assimilation rate (P50An, -MPa), 50% loss of stomatal conductance (P50gs, -MPa), 50% loss of stomatal sensitivity parameter g1 (P50g1, -MPa) and 50% loss of RuBP carboxylation by Rubisco (P50Vcmax, -MPa) (Figure 2). We found P50 was more negative for An than for gs, indicating that the reduction in stomatal conductance preceded the reduction in photosynthesis (Figures 2A,B). When comparing how stomatal sensitivity parameter g1 and Vcmax contributed to the overall reduction in gs, we found P50g1 and P50Vcmax were correlated, while the P50Vcmax was consistently more negative than P50g1 – indicating the reduction in g1 preceded the reduction in Vcmax (Figures 2E,F). Moreover, compared with species from wetter climates, species from drier climates tends to show larger difference between P50Vcmax and P50gs (Figure 2). These differences are presumed to have adaptive significance for the survival of plants in dry climates.

Figure 2. Correlation between the pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% loss of photosynthetic functions and moisture index for six woody species from contrasting hydroclimates. (A) The pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% loss of net carbon assimilation rate (P50An, -MPa) and moisture index. (B) The pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% loss of stomatal conductance (P50gs, -MPa) and moisture index. (C) The pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% loss of stomatal sensitivity parameter g1 (P50g1, -MPa) and moisture index. (D) The pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% loss of RuBP carboxylation by Rubisco (P50Vcmax, -MPa) and moisture index. (E) Correlation between P50Vcmax and P50gs. (F) Correlation between P50g1 and P50gs. Moisture index is the ratio between mean annual precipitation and mean annual potential evapotranspiration, which can range from zero in the driest regions to higher values in wetter regions (Zhou et al., 2014). Values of P50An, P50gs, P50g1 and P50Vcmax (solid circle) – and the bootstrap 2.5% and bootstrap 95% values (bars) to indicate the error in each estimate – were fitted by employing data from Zhou et al. (2014) using the ‘fitplc’ package in R (Duursma and Choat, 2017).

Interspecific Variation in the Degree of Plant Photosynthetic Acclimation to Prolonged Water Stress

Plants subjected to short-term experimental drought are well documented to experience a decline in photosynthetic capacity. However, plants under prolonged drought may be able to acclimate to drought to some extent, for example through morphological adjustments such as changes in mass allocation to leaves and/or roots (Choat et al., 2018), provided the drought is imposed slowly enough for such changes to take effect. In general, therefore, it is to be expected that the mechanisms underlying plant responses to water stress vary according to time scale (Maseda and Fernández, 2006; Limousin et al., 2010a,b; Martin-StPaul et al., 2012, 2013). Maseda and Fernández (2006) proposed that plants acclimate to drought at the whole-organism level through physiological, anatomical, and morphological adjustments that are adaptive over a time scale of months.

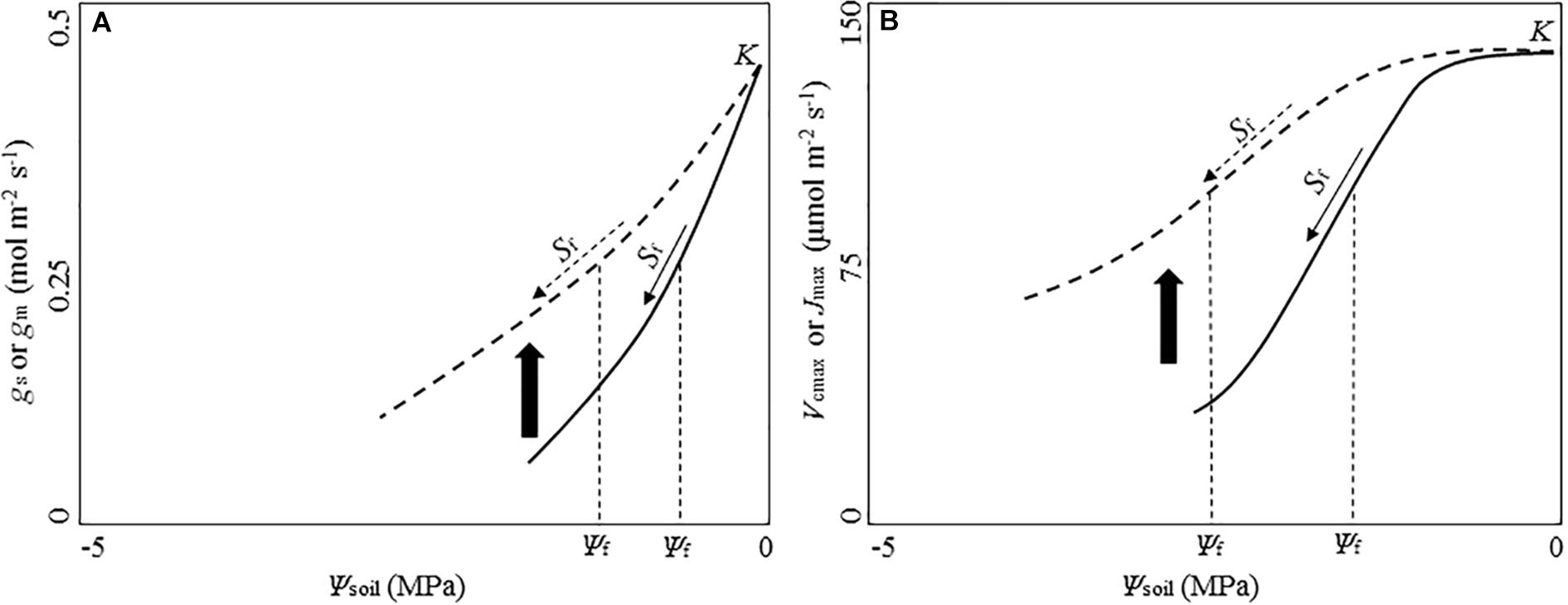

When given time to acclimate to water stress, the photosynthetic response of plants could differ from that of plants in short-term water stress (Figure 3). Some longer-term experiments reported higher leaf gas exchange rates for woody plants in the drought treatment (Cinnirella et al., 2002; Ogaya and Peñuelas, 2003; Llorens et al., 2004). Cano et al. (2014) reported xeric species showed significant higher gm than mesic species under longer-term water stress. Leaves developed during the long-term drought can acclimate by increasing partitioning to total soluble proteins, allowing higher Rubisco activity per unit leaf area (Panković et al., 1999). The Rubisco content could also increase in leaves under prolonged drought, and the increase could be significantly higher in leaves of the drought-tolerant plant taxa than other taxa, conferring the drought-tolerant taxa with better acclimation and higher drought tolerance (Panković et al., 1999).

Figure 3. Conceptual diagram of potential acclimation responses of diffusional and biochemical parameters to water stress. Solid lines show the strong short-term sensitivity of parameters to the decreasing soil water potential (Ψsoil) before plants being given time to acclimate to water stress. Dashed lines indicate reduced sensitivity to soil water potential following a period of acclimation to water stress. Upward arrow between the solid and dashed line shows potential shift upward of the drought-response curve during acclimation. (A) Exponential function of stomatal conductance (gs) and mesophyll conductance (gm) with the decreasing Ψsoil based on Zhou et al. (2013, 2014). (B) Logistic function of the maximum rate of CO2 consumption by RuBP carboxylation by Rubisco (Vcmax) and the maximum electron transport rate (Jmax) with the decreasing Ψsoil based on Zhou et al. (2013, 2014). K is the maximum value of the parameter under moist conditions. Sf indicates the sensitivity of each parameter against the decreasing Ψsoil. Ψf is soil water potential at 50% reduction of K.

Despite its importance, the photosynthetic responses of plants to long-term water stress and its variation among species of contrasting climate of origin are poorly understood (Cano et al., 2014). Moreover, long-term studies disagree on whether or not plants can modify the functional relationships between photosynthetic traits and soil water potential to acclimate to long-term water stress (Limousin et al., 2010b; Misson et al., 2010; Martin-StPaul et al., 2012). There could be systematic differences in these functional relationships related to species’ climatic origin. Zhou et al. (2016) found the xeric Eucalyptus species showed more effective drought acclimation – significantly lower Vcmax sensitivity to declined pre-dawn leaf water potential – than the riparian species under prolonged drought. Species-specific physiology may play an importance role in the comparative photosynthetic acclimation of contrasting species under prolonged water stress, leading to the varied findings among these studies (Ogaya and Peñuelas, 2003; Cano et al., 2014).

Intra- and inter- specific variation in drought tolerance and acclimation could have important implications for forest modeling in water-limited ecosystems, particularly in a long-term perspective that takes future climate change into account. Ignoring potentially important acclimation processes in the field could lead to overestimation of the long-term consequences of drought. Changes in forest composition related to drought tolerance and acclimation are already beginning to be observed. For example, the more drought-tolerant Quercus pubescens was reported to be replacing Pinus sylvestris at low altitudes in Switzerland, where climate change has brought about recurrent water deficits (Eilmann et al., 2006). Reliable prediction of drought effects on contrasting species and forest ecosystems under field conditions requires long-term experiments on the drought-induced limitations on photosynthetic and hydraulic properties, and their potential acclimation to prolonged drought (see a review by Choat et al., 2018). The number of such studies in the literature, however, is surprisingly small, with most published manipulative experiments focusing exclusively on short-term responses to drought.

Incorporating Experiment-Derived Pft-Specific Drought Response of gs and Vcmax to Improve Modeling Ecosystem Responses to Drought

Current LSMs treat plant ecophysiological properties simplistically assuming the same drought sensitivity for all vegetation (Prentice and Cowling, 2013; De Kauwe et al., 2015b), disregarding known aspects of trait correlation and trait-environment relationships (Wright et al., 2004; Maire et al., 2013; Prentice et al., 2014) and the considerable variation of drought sensitivity among plant species of different climatic origin highlighted in recent model-oriented experiments and data syntheses (Zhou et al., 2013, 2014). Insufficient attention has been paid to the evaluation of LSMs in their representations of the fundamental eco-physiological responses to drought, in part because their early history of development pre-dates the availability of many relevant measurement data sets (Prentice et al., 2015). It is critical for LSMs to realistically represent the differential drought responses of different vegetation types.

Largely due to the shortage of model-oriented experimental studies describing the separate effects of drought on stomatal and non-stomatal processes, there are large discrepancies in the ways in which current ecosystem models represent the drought effect on plant gas exchange (Powell et al., 2013; Medlyn et al., 2016). There has been a scientific debate on how to represent stomatal closure as soil moisture declines (Bonan et al., 2014). Current state-of-the-art LSMs used in coupled climate models generally treat all PFTs as experiencing similar stomatal and/or non-stomatal limitation during drought (via soil texture and assumed rooting depths). Many LSMs use an empirical soil moisture stress factor (β) – as a function of volumetric water content (𝜃) – to impose for down-regulation of stomatal response at decreasing soil moisture, which allowing an abrupt transition in β to take place within a narrow range of 𝜃 (Egea et al., 2011; Powell et al., 2013; De Kauwe et al., 2015a,b; but see Medlyn et al., 2016). Powell et al. (2013) reported unrealistic drought responses due to implementing abrupt transitions of this kind in four models [Community Land Model version 3.5 (CLM3.5), Integrated BIosphere Simulator version 2.6.4 (IBIS), Joint UK Land Environment Simulator version 2.1 (JULES), and Simple Biosphere model version 3 (SiB3)], which use different water-stress functions – loosely constrained by data – to down-regulate soil moisture effects on gs. The sharp shutdown seems to be a common challenge in LSMs whereas the observed fluxes decline much more gradually with water stress (Medlyn et al., 2016). Zhou (2015) compared the 𝜃 effect on An in the Community Atmosphere Biosphere Land Exchange (CABLE) LSM, and found a rather abrupt transition in An from near-normal function to nearly complete shutdown within a narrow range of 𝜃 – regardless of PFT or soil type. This modeled abrupt transition is very unlikely under field conditions where the transition from full vegetation function to drought conditions should occur more gradually as a consequence of spatial heterogeneity in plant and soil properties (Liang et al., 1994; Prentice et al., 2015).

Land surface models commonly include generic responses of plant carbon uptake and water loss to soil moisture content. It seems plausible that the performance of LSMs might be improved by including empirically based plant responses to drought, expressed as a function of soil water potential (the key property affecting plant water uptake) and derived from measurements on species of different PFT membership. However, the process of estimation of required model parameters (e.g., quantifying the response functions of photosynthetic and hydraulic traits against drought) for global models is not straightforward and usually not transparent (Choat et al., 2018; Dewar et al., 2018). De Kauwe et al. (2015b) tested whether using the information pertinent to the representation of gs and Vcmax responses in process-based models in Zhou et al. (2013, 2014) would improve the prediction of canopy-atmosphere fluxes during drought in the CABLE model. By estimating soil water potential from dynamically weighted soil layers, De Kauwe et al. (2015b) resolved the modeling challenge in CABLE – the steep drop-off of leaf photosynthesis with soil water content due to the rapid change in soil moisture potential (Zhou, 2015). It is found that CABLE can only accurately reproduce the drought impacts during the 2003 heat wave if the most mesic sites were attributed a high drought sensitivity and the most xeric sites were attributed a lower drought sensitivity (De Kauwe et al., 2015b). These studies demonstrated a practical and effective approach to gain information on drought responses in a form directly applicable to modeling, and highlighted that LSMs will over-estimate the drought impacts in drier climates if the different sensitivity of vegetation to drought were not taken into account (De Kauwe et al., 2015b; Zhou, 2015).

Furthermore, recent efforts to improve model simulation on vegetation dynamics also have highlighted the importance of linking plant traits – especially the correlation among hydraulic and photosynthetic traits (e.g., the water potentials at 50% loss of xylem conductivity and 50% loss of stomatal conductance, respectively) – to forest function under drought (Christoffersen et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016; see a review by Choat et al., 2018). Christoffersen et al. (2016) represented the correlations between plant hydraulic traits and the leaf and stem economic traits within a trait-driven model, and found substantial improvement of the model simulations of total ecosystem transpiration fluxes. Xu et al. (2016) updated the Ecosystem Demography model 2 with a novel hydraulics-driven phenology scheme, which incorporated PFT-specific functional traits and allowed alternative photosynthetic and phenological strategies to dominate depending on rainfall seasonality, and found it substantially improved the model simulation of spatiotemporal patterns of vegetation dynamics in seasonally dry tropical forests.

Significance of Model-Experiment Synthesis: Future Perspectives

Increasing research efforts are devoted to improving models through the use of new representations of specific processes based on new data syntheses or experimental findings (e.g., Bonan et al., 2011, 2012; Medlyn et al., 2011, 2016; Prentice et al., 2014; De Kauwe et al., 2015a,b; Christoffersen et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2017; see a model-data integration process by Walker et al., 2014). These studies have highlighted the significance of bridging experiment-tested eco-physiological processes and land ecosystem models, through translating empirical findings into improved process representations within models and tested model simulations against carbon and water flux measurements at the ecosystem scale.

Both plant physiologists and modelers should be exposed to the significance of informing process-based models with experimentally derived quantitative information when studying the drought impacts on photosynthetic and hydraulic properties, their variation across forest ecosystems and their interaction underlying short-term and prolonged drought consequences. The model-orientated experimental work would ideally be carried out to identify different drought tolerances in a quantitative modeling context – both in respect of short-term drought responses, and acclimation processes by which plants can adapt to longer-term, lower-level drought – between species from mesic and xeric habitats.

In this review, the new analysis highlights that the drought sensitivities of photosynthesis are consistently higher for species from wetter climates (showing strong diffusional and metabolic limitations earlier during the drying-down process) than species from drier climates (showing more negative pre-dawn leaf water potential at 50% reduction of diffusional and metabolic activities) (Figure 2). The positive correlations among the rates of decline of the parameters as the experimental drought progressed define a spectrum of drought adaptations, from more resistant species thriving in dry environments, to more sensitive species thriving in moist environments (Figure 2; but see Lamy et al., 2014). These findings support the existence of a co-ordinated spectrum of increasing tolerance in plants from wetter to drier environments, and provide a complementary perspective on the finding by Choat et al. (2012) based on hydraulic traits that trees in mesic habitats – which are not normally considered to be at risk from drought – are actually just as vulnerable to drought as trees in xeric habitats. Meanwhile, these studies have casted light on the general responses of leaf gas exchange to short- and long-term soil water deficits, allowing for realistic model representations of different drought sensitivities among species and PFTs from wetter or drier environments. By providing process-based analytical models of key parameters that define these responses for contrasting species with differential drought sensitivities, these model-oriented experimental studies have offered potentially robust solutions to the problem of representing adaptive differences among PFTs into LSMs.

This review suggests the following priorities to help guide future research to improve modeling on drought compacts upon a firm theoretical and empirical basis:

(1) Plants are subject to Darwinian selection and can adjust genetically or phenotypically to environment to maximize their fitness. Optimality concepts have been proposed and tested on various aspects of plant and ecosystem functions including plant water use, stomatal behavior, photosynthetic capacity, nitrogen uptake and phenology (e.g., Prentice et al., 2014). Covariation of different plant traits is expected to be an expression of optimality principles (Wright et al., 2004; Prentice et al., 2014; Reich, 2014) and should simplify the parameterizations of fundamental eco-physiological responses to environmental drivers, including drought. An explicit theoretical framework is necessary to incorporate the variation, interrelationships and environmental dependencies of plant traits into models. Such quantitative information explaining fundamental plant-level processes and quantifying variability in key plant traits under drought, if gathered on a wider range of species, could allow testing for the existence of a spectrum of drought-response traits, and ultimately a deeper understanding of drought-response strategies (Wright et al., 2004; Prentice et al., 2014; Reich, 2014) and a more comprehensive approach to both trait data analysis and vegetation modeling (Prentice et al., 2014).

(2) Model predictions of future drought impacts on ecosystems, and feedbacks to the atmosphere, should aim to represent drought responses of major plant physiological exchanges (CO2 and water vapor fluxes between leaf and the atmosphere) realistically, with simple and observationally tested process formulations. They must account for the observed differences between the responses of different PFTs to drought. The realistic model representation of stomatal and non-stomatal responses to short-term and prolonged drought – and their variation among plants of different PFT membership and/or climatic origin – will be fundamental to the prediction of drought-induced mortality at plant scale (due to hydraulic failure, carbon starvation, and/or other mechanisms), or carbon loss at the ecosystem scale. Varied vegetation sensitivity to drought are necessary for LSMs to accurately explain the large-scale patterns of drought response of carbon, water and energy fluxes observed in different environments (De Kauwe et al., 2015b).

(3) Time scale may be of the essence when determining the extent to which climate change is likely to adversely affect forests. Drought acclimation is evidently a real phenomenon in trees adapted to dry climates, and presumably allows such trees to cope with periodic, protracted (but not too severe) droughts. The inherent differences among the species from contrasting climatic origins can be shown not only in their contrasting degree of tolerance to short-term drought (e.g., Zhou et al., 2013, 2014), but also in their contrasting abilities to compensate for long-term drought (e.g., Zhou et al., 2016). Drought-induced mortality of trees, and carbon loss from forests, could be overestimated if such acclimation is not taken into account (Choat et al., 2018). Model projections of drought effects on species distributions and vegetation composition in climate change scenarios should consider the differences in both short-term drought sensitivity and longer-term acclimation potential among species adapted to different climates.

The studies in this review mainly consider short-term dynamics of stomatal behavior and marginal water use efficiency, whose temporal dynamics could differ across seasons and years (Chen et al., 2018). Incorporation of their long-term dynamic patterns – such as the potential difference between dry versus wet seasons and across forest ecosystems – into ecosystem models remains to be improved. Besides, future model-experiment inter-comparison analysis needs to improve the representation of photosynthetic responses to co-occurring environmental stresses, such as drought and heat wave – which usually occur together (Ciais et al., 2005; Granier et al., 2007). High temperature can cause severe impacts on the photosynthetic apparatus, particularly during long-lasting drought events. Meanwhile, forest ecosystems at hot and dry environments – where stomatal closure (contributing to higher leaf temperature) and low Cc are necessary for plants to conserve water and avoid hydraulic failure (see a review by Choat et al., 2018) – could show very different responses of Rubisco characteristics and photosynthetic capacity under drought and high temperature conditions (Delgado et al., 1995; Kent and Tomany, 1995; Galmés et al., 2005). The model-experiment synthesis work in this area will enhance our predictions of environmental change consequences on forestry ecosystems.

Conclusion

Investigating the general trends of trait variation with key environmental factors, and translating this variation into improved process representation in vegetation models, are important developments for the improvement of LSMs and DGVMs. The model-oriented data analysis, experiments, and modeling described in this review amount to a new synthesis of information on the responses of different plant functions to drought, and provide a general methodology for systematic study of the relationship between plant processes and drought, allowing the derivation of functions that can be used directly in modeling. They can be seen as part of a wider movement toward the observationally driven parameterization of fundamental vegetation processes. Such work can also contribute to climate-change adaptation, through facilitating more accurate predictions of how forestry systems are likely to respond to projected changes in drought intensity and duration in a rapidly changing world.

Author Contributions

S-XZ drafted the work. All authors contributed substantially to the conception of this work and critically revised the work. ICP secured the funding.

Funding

The work was financially supported by the International Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreement No: 787203 REALM).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

S-XZ was supported by an International Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship. This work is a contribution to the AXA Chair Programme in Biosphere and Climate Impacts and the Imperial College initiative Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment.

References

Adams, H. D., Guardiola-Claramonte, M., Barron-Gafford, G. A., Villegas, J. C., Breshears, D. D., Zou, C. B., et al. (2009). Temperature sensitivity of drought-induced tree mortality portends increased regional die-off under global-change-type drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7063–7066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901438106

Allen, C. D., Macalady, A. K., Chenchouni, H., Bachelet, D., McDowell, N., Vennetier, M., et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 259, 660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

Anderegg, W. R., Berry, J. A., Smith, D. D., Sperry, J. S., Anderegg, L. D., and Field, C. B. (2012). The roles of hydraulic and carbon stress in a widespread climate-induced forest die-off. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 233–237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107891109

Baldocchi, D. (1997). Measuring and modeling carbon dioxide and water vapor exchange over a temperate broad-leaved forest during the 1995 summer drought. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 1108–1122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-147.x

Ball, J. T., Woodrow, I. E., and Berry, J. A. (1987). “A model predicting stomatal conductance and its contribution to the control of photosynthesis under different environmental conditions,” in Progress in Photosynthesis Research, ed. J. Biggins (Dordrecht: Martinus-Nijhoff Publishers), 221–224.

Bernacchi, C. J., Bagley, J. E., Serbin, S. P., Ruiz-Vera, U. M., Rosenthal, D. M., and VanLoocke, A. (2013). Modelling C3 photosynthesis from the chloroplast to the ecosystem. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 1641–1657. doi: 10.1111/pce.12118

Berninger, F., and Hari, P. (1993). Optimal regulation of gas exchange: evidence from field data. Ann. Bot. 71, 135–140. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1993.1017

Bonan, G. B. (1995). Land-atmosphere CO2 exchange simulated by a land surface process model coupled to an atmospheric general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 2817–2831. doi: 10.1029/94JD02961

Bonan, G. B. (2008). Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.1155121

Bonan, G. B., Lawrence, P. J., Oleson, K. W., Levis, S., Jung, M., Reichstein, M., et al. (2011). Improving canopy processes in the community land model version 4 (CLM4) using global flux fields empirically inferred from FLUXNET data. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 116:G2. doi: 10.1029/2010JG001593

Bonan, G. B., Oleson, K. W., Fisher, R. A., Lasslop, G., and Reichstein, M. (2012). Reconciling leaf physiological traits and canopy flux data: use of the TRY and FLUXNET databases in the community land model version 4. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 117:G2. doi: 10.1029/2011JG001913

Bonan, G. B., Williams, M., Fisher, R. A., and Oleson, K. W. (2014). Modeling stomatal conductance in the earth system: linking leaf water-use efficiency and water transport along the soil–plant–atmosphere continuum. Geosci. Model Dev. 7, 2193–2222. doi: 10.5194/gmd-7-2193-2014

Bota, J., Medrano, H., and Flexas, J. (2004). Is photosynthesis limited by decreased Rubisco activity and RuBP content under progressive water stress? New Phytol. 162, 671–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01056.x

Cano, F. J., López, R., and Warren, C. R. (2014). Implications of the mesophyll conductance to CO2 for photosynthesis and water use efficiency during long-term water stress and recovery in two contrasting Eucalyptus species. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 2470–2490. doi: 10.1111/pce.12325

Castrillo, M., Fernandez, D., and Calcagno, A. (2001). Responses of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase, protein content, and stomatal conductance to water deficit in maize, tomato, and bean. Photosynthetica 39, 221–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1013731210309

Chaves, M. M., Maroco, J. P., and Pereira, J. S. (2003). Understanding plant responses to drought – from genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 30, 239–264. doi: 10.1071/FP02076

Chen, M., Wang, G., Zhou, S., Zhao J., Zhang X., He C., et al. (2018). Studies on forest ecosystem physiology: marginal water-use efficiency of a tropical, seasonal, evergreen forest in Thailand. J. For. Res. doi: 10.1007/s11676-018-0804-5

Choat, B., Brodribb, T. J., Brodersen, C. R., Duursma, R. A., López, R., and Medlyn, B. E. (2018). Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 558, 531–539. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0240-x

Choat, B., Jansen, S., Brodribb, T. J., Cochard, H., Delzon, S., Bhaskar, R., et al. (2012). Global convergence in the vulnerability of forests to drought. Nature 491, 752–755. doi: 10.1038/nature11688

Christoffersen, B. O., Gloor, M., Fauset, S., Fyllas, N. M., Galbraith, D. R., Baker, T. R., et al. (2016). Linking hydraulic traits to tropical forest function in a size-structured and trait-driven model (TFS v. 1-Hydro). Geosci. Model Dev. 9:4227. doi: 10.5194/gmd-9-4227-2016

Ciais, P., Reichstein, M., Viovy, N., Granier, A., Ogée, J., Allard, V., et al. (2005). Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature03972

Cinnirella, S., Magnani, F., Saracino, A., and Borghetti, M. (2002). Response of a mature Pinus laricio plantation to a three-year restriction of water supply: structural and functional acclimation to drought. Tree Physiol. 22, 21–30. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.1.21

Clark, J. S., Bell, D. M., Kwit, M., Stine, A., Vierra, B., and Zhu, K. (2012). Individual-scale inference to anticipate climate-change vulnerability of biodiversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 236–246. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0183

Collatz, G. J., Ball, J. T., Grivet, C., and Berry, J. A. (1991). Physiological and environmental regulation of stomatal conductance, photosynthesis and transpiration: a model that includes a laminar boundary layer. Agric. For. Meteorol. 54, 107–136. doi: 10.1016/0168-1923(91)90002-8

Cowan, I. R. (1977). Stomatal behaviour and environment. Adv. Bot. Res. 4, 117–288. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60370-5

Cowan, I. R., and Farquhar, G. D. (1977). Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 31, 471–505.

Cox, P. M., Huntingford, C., and Harding, R. J. (1998). A canopy conductance and photosynthesis model for use in a GCM land surface scheme. J. Hydrol. 21, 79–94. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00203-0

De Kauwe, M. G., Kala, J., Lin, Y. S., Pitman, A. J., Medlyn, B. E., Duursma, R. A., et al. (2015a). A test of an optimal stomatal conductance scheme within the CABLE land surface model. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 431–452. doi: 10.5194/gmd-8-431-2015

De Kauwe, M. G., Zhou, S. X., Medlyn, B. E., Pitman, A. J., Wang, Y. P., Duursma, R. A., et al. (2015b). Do land surface models need to include differential plant species responses to drought? Examining model predictions across a mesic-xeric gradient in Europe. Biogeosciences 12, 7503–7518. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-7503-2015

Delgado, E., Medrano, H., Keys, A. J., and Parry, M. A. J. (1995). Species variation in Rubisco specificity factor. J. Exp. Bot. 46, 1775–1777. doi: 10.1093/jxb/46.11.1775

Dewar, R., Mauranen, A., Mäkelä, A., Hölttä, T., Medlyn, B., and Vesala, T. (2018). New insights into the covariation of stomatal, mesophyll and hydraulic conductances from optimization models incorporating nonstomatal limitations to photosynthesis. New Phytol. 217, 571–585. doi: 10.1111/nph.14848

Duursma, R. A., and Choat, B. (2017). fitplc – An R package to fit hydraulic vulnerability curves. J. Plant Hydraul. 4:e002. doi: 10.20870/jph.2017.e002

Egea, G., Verhoef, A., and Vidale, P. L. (2011). Towards an improved and more flexible representation of water stress in coupled photosynthesis–stomatal conductance models. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 1370–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.05.019

Eilmann, B., Weber, P., Rigling, A., and Eckstein, D. (2006). Growth reactions of Pinus sylvestris L. and Quercus pubescens willd. to drought years at a xeric site in Valais, Switzerland. Dendrochronologia 23, 121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2005.10.002

Engelbrecht, B. M., Comita, L. S., Condit, R., Kursar, T. A., Tyree, M. T., Turner, B. L., et al. (2007). Drought sensitivity shapes species distribution patterns in tropical forests. Nature 447, 80–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05747

Evans, J. R., and von Caemmerer, S. (2013). Temperature response of carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance in tobacco. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 745–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02591.x

Farquhar, G. D., von Caemmerer, S., and Berry, J. A. (1980). A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149, 78–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00386231

Flexas, J., Barbour, M. M., Brendel, O., Cabrera, H. M., Carriquí, M., Díaz-espejo, A., et al. (2012). Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci. 194, 70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.05.009

Flexas, J., Bota, J., Loreto, F., Cornic, G., and Sharkey, T. D. (2004). Diffusive and metabolic limitations to photosynthesis under drought and salinity in C3 plants. Plant Biol. 6, 269–279. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820867

Flexas, J., Diaz-Espejo, A., Galmés, J., Kaldenhoff, R., Medrano, H., and Ribas-Carbo, M. (2007). Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1284–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01700.x

Flexas, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., Bota, J., Galmés, J., Henkle, M., Martínez-Cañellas, S., et al. (2006). Decreased Rubisco activity during water stress is not induced by decreased relative water content but related to conditions of low stomatal conductance and chloroplast CO2 concentration. New Phytol. 172, 73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01794.x

Flexas, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., Diaz-Espejo, A., Galmés, J., and Medrano, H. (2008). Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 602–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01757.x

Galmés, J., Aranjuelo, I., Medrano, H., and Flexas, J. (2013). Variation in Rubisco content and activity under variable climatic factors. Photosynthesis Res. 117, 73–90. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9861-y

Galmés, J., Flexas, J., Keys, A. J., Cifre, J., Mitchell, R. A., and Madgwick, P. J. (2005). Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 571–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01300.x

Granier, A., Reichstein, M., Bréda, N., Janssens, I. A., Falge, E., Ciais, P., et al. (2007). Evidence for soil water control on carbon and water dynamics in European forests during the extremely dry year: 2003. Agric. For. Meteorol. 143, 123–145. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.12.004

Grassi, G., and Magnani, F. (2005). Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 834–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01333.x

Groenendijk, M., Dolman, A. J., Van der Molen, M. K., Leuning, R., Arneth, A., Delpierre, N., et al. (2011). Assessing parameter variability in a photosynthesis model with and between plant functional types using global Fluxnet eddy covariance data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 22–38. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2010.08.013

Hall, A. E., and Schulze, E. D. (1980). Stomatal response to environment and a possible interrelation between stomatal effects on transpiration and CO2 assimilation. Plant Cell Environ. 3, 467–474. doi: 10.1111/1365-3040.ep11587040

Haxeltine, A., and Prentice, I. C. (1996). BIOME3: an equilibrium terrestrial biosphere model based on ecophysiological constraints, resource availability, and competition among plant function types. Glob. Biogeochem. 10, 693–709. doi: 10.1029/96GB02344

Héroult, A., Lin, Y.-S., Bourne, A., Medlyn, B. E., and Ellsworth, D. S. (2013). Optimal stomatal conductance in relation to photosynthesis in climatically contrasting Eucalyptus species under drought. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 262–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02570.x

Kanechi, M., Uchida, N., Yasuda, T., and Yamaguchi, T. (1996). Non-stomatal inhibition associated with inactivation of rubisco in dehydrated coffee leaves under unshaded and shaded conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 455–460. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028967

Kattge, J., Knorr, W., Raddatz, T., and Wirth, C. (2009). Quantifying photosynthetic capacity and its relationship to leaf nitrogen content for global-scale terres- trial biosphere models. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 976–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01744.x

Kent, S. S., and Tomany, M. J. (1995). The differential of the ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase specificity factor among higher plants and the potential for biomass enhancement. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 33, 71–80.

Klein, T. (2014). The variability of stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential across tree species indicates a continuum between isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Funct. Ecol. 28, 1313–1320. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12289

Kljun, N., Black, T. A., Griffis, T. J., Barr, A. G., Gaumont-Guay, D., Morgenstern, K., et al. (2006). Response of net ecosystem productivity of three boreal forest stands to drought. Ecosystems 9, 1128–1144. doi: 10.1007/s10021-005-0082-x

Knapp, A. K., and Smith, M. D. (2001). Variation among biomes in temporal dynamics of aboveground primary production. Science 291, 481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.481

Lamy, J. B., Delzon, S., Bouche, P. S., Alia, R., Vendramin, G. G., Cochard, H., et al. (2014). Limited genetic variability and phenotypic plasticity detected for cavitation resistance in a Mediterranean pine. New Phytol. 201, 874–886. doi: 10.1111/nph.12556

Lawlor, D. W., and Tezara, W. (2009). Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: a critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Ann. Bot. 103, 561–579. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn244

Li, X., Blackman, C. J., Choat, B., Duursma, R. A., Rymer, P. D., Medlyn, B. E., et al. (2018). Tree hydraulic traits are co ordinated and strongly linked to climate of origin across a rainfall gradient. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 646–660. doi: 10.1111/pce.13129

Liang, X., Lettenmaier, D. P., Wood, E. F., and Burges, S. J. (1994). A simple hydrologically based model of land surface water and energy fluxes for general circulation models. J. Geophys. Res. 99, 14415–14428. doi: 10.1029/94JD00483

Limousin, J. M., Longepierre, D., Huc, R., and Rambal, S. (2010a). Change in hydraulic traits of Mediterranean Quercus ilex subjected to long-term throughfall exclusion. Tree Physiol. 30, 1026–1036. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq062

Limousin, J. M., Misson, L., Lavoir, A. V., Martin, N. K., and Rambal, S. (2010b). Do photosynthetic limitations of evergreen Quercus ilex leaves change with long term increased drought severity? Plant Cell Environ. 33, 863–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02112.x

Llorens, L., Peñuelas, J., Beier, C., Emmet, B., Estiarte, M., and Tietema, A. (2004). Effects of an experimental increase of temperature and drought on the photosynthetic performance of two ericaceous shrub species along a northsouth European gradient. Ecosystems 7, 613–624. doi: 10.1007/s10021-004-0180-1

Long, S. P., Ainsworth, E. A., Leakey, A. B., Nosberger, J., and Ort, D. R. (2006). Food for thought: lower than expected crop yield stimulation with rising CO2 concentrations. Science 312, 1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1114722

Maire, V., Gross, N., Hill, D., Martin, R., Wirth, C., Wright, I. J., et al. (2013). Disentangling coordination among functional traits using an individual-centred model: impact on plant performance at intra- and inter-specific levels. PLoS One 8:e77372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077372

Mäkelä, A., Berninger, F., and Hari, P. (1996). Optimal control of gas exchange during drought: theoretical analysis. Ann. Bot. 77, 461–467. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1996.0056

Manzoni, S. (2014). Integrating plant hydraulics and gas exchange along the drought-response trait spectrum. Tree Physiol. 34, 1031–1034. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu088

Martin-StPaul, N., Delzon, S., and Cochard, H. (2017). Plant resistance to drought depends on timely stomatal closure. Ecol. Lett. 20, 1437–1447. doi: 10.1111/ele.12851

Martin-StPaul, N. K., Limousin, J. M., Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J., Ruffault, J., Rambal, S., Letts, M. G., et al. (2012). Photosynthetic sensitivity to drought varies among populations of Quercus ilex along a rainfall gradient. Funct. Plant Biol. 39, 25–37. doi: 10.1071/FP11090

Martin-StPaul, N. K., Limousin, J. M., Vogt-Schilb, H., Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J., Rambal, S., Longepierre, D., et al. (2013). The temporal response to drought in a Mediterranean evergreen tree: comparing a regional precipitation gradient and a throughfall exclusion experiment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 2413–2426. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12215

Maseda, P. H., and Fernández, R. J. (2006). Stay wet or else: three ways in which plants can adjust hydraulically to their environment. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 3963–3977. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl127

McDowell, N., Pockman, W. T., Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D., Cobb, N., Kolb, T., et al. (2008). Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 178, 719–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02436.x

McDowell, N. G., Beerling, D. J., Breshears, D. D., Fisher, R. A., Raffa, K. F., and Stitt, M. (2011). The interdependence of mechanisms underlying climate-driven vegetation mortality. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.06.003

Medlyn, B. E., De Kauwe, M. G., Zaehle, S., Walker, A. P., Duursma, R. A., Luus, K., et al. (2016). Using models to guide field experiments: a priori predictions for the CO2 response of a nutrient and water limited native Eucalypt woodland. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 2834–2851. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13268

Medlyn, B. E., Duursma, R. A., Eamus, D., Ellsworth, D. S., Prentice, I. C., Barton, C. V., et al. (2011). Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2134–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02375.x

Misson, L., Limousin, J. M., Rodriguez, R., and Letts, M. G. (2010). Leaf physiological responses to extreme droughts in Mediterranean Quercus ilex forest. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 1898–1910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02193.x

Niinemets, U., Penuelas, J., and Flexas, J. (2011). Evergreens favored by higher responsiveness to increased CO2. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.12.012

Ogaya, R., and Peñuelas, J. (2003). Comparative field study of Quercus ilex and Phillyrea latifolia: photosynthetic response to experimental drought conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 50, 137–148. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(03)00019-4

Panković, D., Sakač, Z., Kevrešan, S., and Plesničar, M. (1999). Acclimation to long-term water deficit in the leaves of two sunflower hybrids: photosynthesis, electron transport and carbon metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 50, 127–138. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.330.128

Parry, M. A., Andralojc, P. J., Khan, S., Lea, P. J., and Keys, A. J. (2002). Rubisco ac-tivity: effects of drought stress. Ann. Bot. 89, 833–839. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf103

Pasho, E., Camarero, J. J., de Luis, M., and Vicente-Serrano, S. M. (2011). Impacts of drought at different time scales on forest growth across a wide climatic gradient in north-eastern Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 1800–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.07.018

Phillips, O. L., Aragão, L. E., Lewis, S. L., Fisher, J. B., Lloyd, J., and López-González, G. (2009). Drought sensitivity of the Amazon rainforest. Science 323, 1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1164033

Phillips, O. L., Van Der Heijden, G., Lewis, S. L., López González, G., Aragão, L. E., Lloyd, J., et al. (2010). Drought-mortality relationships for tropical forests. New Phytol. 187, 631–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03359.x

Pinheiro, C., and Chaves, M. M. (2011). Photosynthesis and drought: can we make metabolic connections from available data? J. Exp. Bot. 62, 869–882. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq340

Pitman, A. J. (2003). The evolution of, and revolution in, land surface schemes designed for climate models. Int. J. Climatol. 23, 479–510. doi: 10.1002/joc.893

Potts, M. (2003). Drought in a Bornean everwet rain forest. J. Ecol. 91, 467–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00779.x

Powell, T. L., Galbraith, D. R., Christoffersen, B. O., Harper, A., Imbuzeiro, H., Rowland, L., et al. (2013). Confronting model predictions of carbon fluxes with measurements of Amazon forests subjected to experimental drought. New Phytol. 200, 350–365. doi: 10.1111/nph.12390

Prentice, I. C., and Cowling, S. A. (2013). “Dynamic global vegetation models,” in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 2nd Edn, ed. S. A. Levin (Cambridge: Academic Press), 607–689.

Prentice, I. C., Dong, N., Gleason, S. M., Maire, V., and Wright, I. J. (2014). Balancing the costs of carbon gain and water loss: testing a new quantitative framework for plant functional ecology. Ecol. Lett. 17, 82–91. doi: 10.1111/ele.12211

Prentice, I. C., Liang, X., Medlyn, B. E., and Wang, Y. P. (2015). Reliable, robust and realistic: the three R’s of next-generation land-surface modelling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 5987–6005. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-5987-2015

Reich, P. B. (2014). The world-wide ’fast-slow’ plant economics spectrum: a traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 102, 275–301. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12211

Rogers, A., Medlyn, B. E., Dukes, J. S., Bonan, G., Caemmerer, S., Dietze, M. C., et al. (2017). A roadmap for improving the representation of photosynthesis in Earth system models. New Phytol. 213, 22–42. doi: 10.1111/nph.14283

Sperry, J. S. (2000). Hydraulic constraints on plant gas exchange. Agric. For. Meteorol. 104, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1923(00)00144-1

Sperry, J. S., Wang, Y., Wolfe, B. T., Mackay, D. S., Anderegg, W. R., McDowell, N. G., et al. (2016). Pragmatic hydraulic theory predicts stomatal responses to climatic water deficits. New Phytol. 212, 577–589. doi: 10.1111/nph.14059

Tezara, W., Mitchell, V., Driscoll, S. P., and Lawlor, D. W. (2002). Effects of water deficit and its interaction with CO2 supply on the biochemistry and physiology of photosynthesis in sunflower. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1781–1791. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf021

Tezara, W., Mitchell, V. J., Driscoll, S. D., and Lawlor, D. W. (1999). Water stress inhibits plant photosynthesis by decreasing coupling factor and ATP. Nature 401, 914–917. doi: 10.1038/44842

Thimmanaik, S., Kumar, S. G., Kumari, G. J., Suryanarayana, N., and Sudhakar, C. (2002). Photosynthesis and the enzymes of photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle in mulberry during water stress and recovery. Photosynthetica 40, 233–236. doi: 10.1023/A:1021397708318

Verhoef, A., and Egea, G. (2014). Modeling plant transpiration under limited soil water: comparison of different plant and soil hydraulic parameterizations and preliminary implications for their use in land surface models. Agric. For. Meteorol. 191, 22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2014.02.009

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Gouveia, C., Camarero, J. J., Beguería, S., Trigo, R., López-Moreno, J. I., et al. (2013). Response of vegetation to drought time-scales across global land biomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 52–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207068110

Walker, A. P., Hanson, P. J., De Kauwe, M. G., Medlyn, B. E., Zaehle, S., Asao, S., et al. (2014). Comprehensive ecosystem model data synthesis using multiple data sets at two temperate forest free air CO2 enrichment experiments: model performance at ambient CO2 concentration. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 937–964. doi: 10.1002/2013JG002553

Webb, W. L., Lauenroth, W. K., Szarek, S. R., and Kinerson, R. S. (1983). Primary production and abiotic controls in forests, grasslands, and desert ecosystems in the United States. Ecology 64, 134–151. doi: 10.2307/1937336

Williams, A. P., Allen, C. D., Macalady, A. K., Griffin, D., Woodhouse, C. A., Meko, D. M., et al. (2013). Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 292–297. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1693

Wilson, K. B., Baldocchi, D. D., and Hanson, P. J. (2000). Quantifying stomatal and non-stomatal limitations to carbon assimilation resulting from leaf aging and drought in mature deciduous tree species. Tree Physiol. 20, 787–797. doi: 10.1093/treephys/20.12.787

Wolf, A., Anderegg, W. R., and Pacala, S. W. (2016). Optimal stomatal behavior with competition for water and risk of hydraulic impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E7222–E7230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615144113

Wright, I. J., Reich, P. B., Westoby, M., Ackerly, D. D., Baruch, Z., Bongers, F., et al. (2004). The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428, 821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403

Xu, L., and Baldocchi, D. D. (2003). Seasonal trends in photosynthetic parameters and stomatal conductance of blue oak (Quercus douglasii) under prolonged summer drought and high temperature. Tree Physiol. 23, 865–877. doi: 10.1093/treephys/23.13.865

Xu, X., Medvigy, D., Powers, J. S., Becknell, J. M., and Guan, K. (2016). Diversity in plant hydraulic traits explains seasonal and inter annual variations of vegetation dynamics in seasonally dry tropical forests. New Phytol. 212, 80–95. doi: 10.1111/nph.14009

Yachi, S., and Loreau, M. (1999). Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: the insurance hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 1463–1468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1463

Zeppel, M. B., Wilks, J. V., and Lewis, J. D. (2014). Impacts of extreme precipitation and seasonal changes in precipitation on plants. Biogeosciences 11:3083. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-3083-2014

Zhou, S. (2015). Quantifying and Modelling the Responses of Leaf Gas Exchange to Drought, PhD thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney.

Zhou, S., Duursma, R. A., Medlyn, B. E., Kelly, J. W., and Prentice, I. C. (2013). How should we model plant responses to drought? An analysis of stomatal and non-stomatal responses to water stress. Agric. For. Meteorol. 182, 204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2013.05.009

Zhou, S., Medlyn, B. E., Santiago, S., Sperlich, D., and Prentice, I. C. (2014). Short-term water stress impacts on stomatal, mesophyll, and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis differ consistently among tree species from contrasting climates. Tree Physiol. 34, 1035–1046. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu072

Keywords: photosynthesis, stomatal and non-stomatal limitation, mesophyll conductance, Vcmax, Jmax, drought acclimation, flux measurement, land surface model

Citation: Zhou S-X, Prentice IC and Medlyn BE (2019) Bridging Drought Experiment and Modeling: Representing the Differential Sensitivities of Leaf Gas Exchange to Drought. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1965. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01965

Received: 22 June 2018; Accepted: 18 December 2018;

Published: 15 January 2019.

Edited by:

Zhiyou Yuan, Northwest A&F University, ChinaReviewed by:

Fulai Liu, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkMark Andrew Adams, Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

Copyright © 2019 Zhou, Prentice and Medlyn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuang-Xi Zhou, c2h1YW5neGkuemhvdUBwbGFudGFuZGZvb2QuY28ubno=

Shuang-Xi Zhou

Shuang-Xi Zhou I. Colin Prentice1,3

I. Colin Prentice1,3 Belinda E. Medlyn

Belinda E. Medlyn