- 1Department of Plant Protection, Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Entomology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 3Department of Computer Science, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY, United States

The olfactory system serves a vital role in the evolution and survival of insects, being involved in behaviors such as host seeking, foraging, mating, and oviposition. Odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) and chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are involved in the olfactory recognition process. In this study, BtabCSP11, a CSP11 gene from the whitefly Bemisia tabaci, was cloned and characterized. The open reading frame of BtabCSP11 encodes 136 amino acids, with four highly conserved cysteine residues. The temporal and spatial expression profiles showed that BtabCSP11 was highly expressed in the abdomens of B. tabaci females. Dietary RNA interference (RNAi)-based functional analysis showed substantially reduced fecundity in parthenogenetically reproduced females, suggesting a potential role of BtabCSP11 in B. tabaci reproduction. These combined results expand the function of CSPs beyond chemosensation.

Introduction

The insect olfactory system is used extensively in a variety of contexts, such as during host seeking, foraging, mating, and oviposition behaviors. Odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) and chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are involved in the olfactory recognition process (Pelosi et al., 2014, 2018). Both OBPs and CSPs are globular water-soluble acidic proteins with low isoelectric points found at high concentrations surrounding the chemosensory neurons (Pelosi et al., 2006). However, CSPs share minimal sequence similarity with OBPs. Generally, CSPs appear to be more conserved and are usually smaller (10–15 kDa) than OBPs (15–17 kDa). All CSPs possess four conserved cysteines (Pelosi et al., 2018). Previous studies have shown that CSPs are widely distributed in chemosensory organs, excluding the antennae (Maleszka and Stange, 1997; Nagnan-Le Meillour et al., 2000; Jin et al., 2005). In addition, CSPs are broadly expressed in non-chemosensory tissue, such as the subcuticular layer and wings (Marchese et al., 2000; Ban et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2007). The ubiquitous expression of CSPs suggests that, in addition to their known role in chemosensation, CSPs are involved in other physiological functions. In the honeybee, Apis mellifera, and the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, CSPs play a role in embryonic development (Maleszka et al., 2007; Gong et al., 2010). In addition, CSPs are involved in insecticide resistance in the whitefly Bemisia. tabaci and the mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Liu et al., 2014, 2016; Ingham et al., 2019). CSP3 knockdown reduced female survival and reproduction in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Gong et al., 2012). Pheromone production, sexual behavior, mating, ovulation and oviposition are the main reproductive events. These events play roles in regulation of reproduction in insects (Raabe, 1987). Several studies have reported that insect CSPs can bind sex pheromone analogs and involved in reproduction (Dani et al., 2011; Iovinella et al., 2013).

The whitefly species Bemisia tabaci, one of the world’s most invasive agricultural pests, causes substantial crop losses worldwide by feeding on phloem and transmitting plant viruses. Bemisia Middle East-Asia Minor1 (MEAM1 or “B”) and Mediterranean (MED or “Q”) are the two most invasive biotypes, and have invaded nearly 60 countries in the past two decades (De Barro et al., 2011; Gilbertson et al., 2015; Wan and Yang, 2016). Because of its short life cycle and high fecundity, whitefly management has been extremely challenging. Whitefly control has relied predominantly on synthetic insecticides. Due to overuse, B. tabaci has developed resistance to most commercially available insecticides, particularly the neonicotinoids (Elbert and Nauen, 2000; Horowitz et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2017). Therefore, new control alternatives, such as RNA interference (RNAi), are urgently needed.

RNAi has shown potential as a viable control alternative for agricultural pests (Upadhyay et al., 2011). Baum et al. showed a significant reduction in root damage caused by the Western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera, by feeding larvae insecticidal dsRNAs in a growth chamber assay (Baum et al., 2007). In the meantime, Mao et al. (2007) demonstrated that larval growth in the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera, was arrested when fed transgenic leaves containing dsRNA corresponding to a detoxification enzyme gene. Both of these studies suggest that RNAi can be exploited to control insect pests. Similarly, studies on B. tabaci suggest that this biotechnology has potential in controlling them as well (Ghanim et al., 2007; Upadhyay et al., 2011).

Prior research has documented CSPs in the B. tabaci MEAM1 and MED biotypes (Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2019). Functional analyses, however, are limited. In this study, we explored the function of BtabCSP11 in B. tabaci. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that BtabCSP11 is associated with reproductive behavior in B. tabaci. To test this hypothesis, we carried out the following experiments: (1) we cloned and analyzed the structure of BtabCSP11, and constructed a phylogenetic tree to analyze its evolutionary relationship with other insect CSPs; (2) we measured the temporospatial distribution of BtabCSP11 throughout different developmental stages and across different tissue types; and finally (3) we investigated the function of BtabCSP11 using dietary RNAi.

Materials and Methods

Bemisia tabaci Maintenance and Sample Collection

Bemisia tabaci MED populations were maintained on cotton plants at 27 ± 1°C under a L:D 16:8 photoperiod and 70 ± 10% relative humidity (RH). The identities of these strains were monitored every three generations using a mitochondrial marker, cytochrome oxidase I (mtCO I) (Chu et al., 2010). Different developmental stages, including eggs, the four nymphal stages, and adult females and males; and adult tissue types, including head, abdomen and a mixture of thorax, legs and wings, were collected separately from three B. tabaci MED populations. A total of 500 B. tabaci were collected per replicate for the egg and four nymphal stages, while 100 individuals were collected per replicate for adult females and males. Three independent biological replicates were used for each sample. Samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for the subsequent RT-qPCR analyses.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Molecular Cloning of BtabCSP11

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, United States), and integrity was checked with 1% Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE) agarose gel electrophoresis. For gene cloning and RT-qPCR analysis, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA with the PrimeScript® RT reagent kit (TaKaRa Biotech, Kyoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The synthesized first-strand cDNA was either used immediately or stored at −20°C for later use. We obtained the full-length sequence of BtabCSP11 from the B. tabaci MED genome and transcriptome (Xie et al., 2017).

Sequence Analysis

The program SignalPV5.01 was used to predict the putative N-terminal signal peptides and cleavage sites of BtabCSP11. The occurrence of α-helices and molecular weight were predicted using ExPASy2. The CSPs of other insect species discussed in this study were retrieved from the NCBI database. ClustalW was used to align the sequences with default gap penalty parameters of gap opening = 10 and extension = 0.2. An alignment graph was generated using WebLogo.

Phylogenetic Analysis

A neighbor-joining tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0 with a p-distance model and pairwise deletion of gaps (Tamura et al., 2013). The bootstrap support of tree branches was assessed by resampling amino acid positions 1,000 times. Sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis were open reading frames (Supplementary Table S1). Phylogenetic trees were then presented in circular shape and colored taxonomically using online tools provided by Evolview (He et al., 2016).

Expression Profiles of BtabCSP11

Expression profiles of BtabCSP11 throughout different developmental stages of B. tabaci MED were obtained using transcriptome data (SRP064690). In addition, we validated transcriptomic profiles using RT-qPCR analysis (Zeng et al., 2019). Five two-fold serial dilutions of whitefly cDNA template were used to determine RT-qPCR primer amplification efficiencies through dissociation curve analysis. Only primers with 90–110% amplification efficiencies were used for subsequent analysis. Relative quantification was calculated using the 2–Δ Δ Ct method, and mRNA expression values were normalized to the recommended reference genes EF1-α, SDHA and Actin (Li et al., 2013). Three biological and four technical replicates were used for each sample. Significant differences between samples were determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test. SPSS20.0 was used to analyze correlations between RT-qPCR and RNA-seq data.

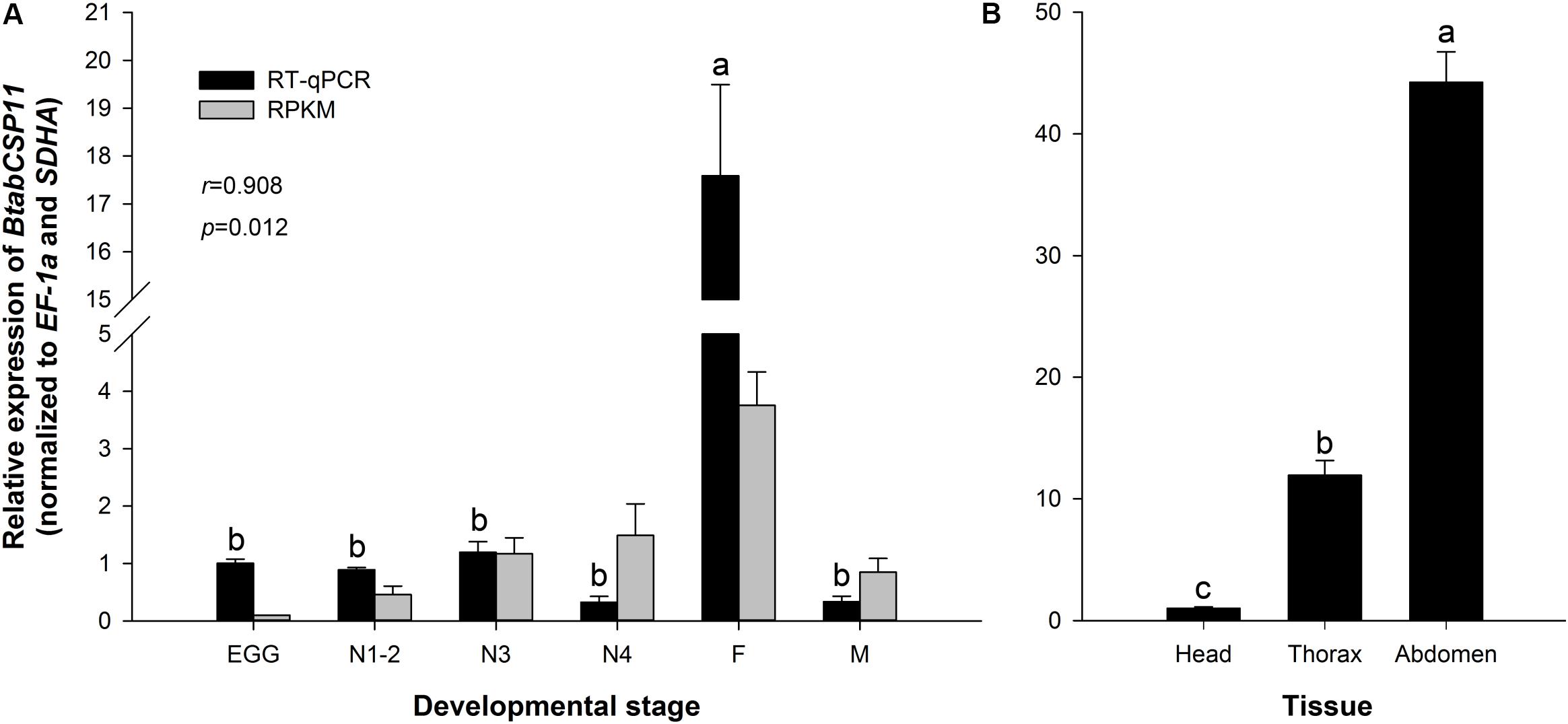

Dietary RNAi

dsRNA primers of BtabCSP11 and EGFP (GenBank: KC896843) with a T7 promoter sequence were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Table 1). dsRNAs of BtabCSP11 and EGFP were synthesized using the T7 RibomaxTM Express RNAi System (Promega, Madison, WI, United States). The quality of dsRNA was evaluated by gel electrophoresis, and dsRNA concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

Knockdown of BtabCSP11 was performed by orally feeding dsRNAs to B. tabaci MED adult females in a feeding chamber. The feeding chambers contained 200 μL of diet solution, which consisted of 30% sucrose, 5% yeast extract (weight/volume), ddH2O and 0.5 μg/μL dsBtabCSP11. Approximately 45 newly emerged (<2 days old) B. tabaci MED adult females were released into the feeding chambers, and were kept at 25°C, 80% RH, and a L:D 16:8 photoperiod. The effectiveness of RNAi was evaluated by RT-qPCR 2 days post-feeding. Each RNAi treatment was repeated six times.

Oviposition Bioassay

After feeding, fecundity (Berger et al., 2008), i.e., the number of eggs laid per adult female, was counted at day 1, 3, 7, and 10. Fresh cotton leaves were provided every day. Bemisia tabaci reproduction was recorded as the mean number of eggs per surviving whitefly laid. A total of six independent biological replicates were used for each sample. Data were analyzed with SPSS20.0. Differences among treatments were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test. Figures were generated using SigmaPlot 12.5.

Results

Identification and Sequence Analysis of BtabCSP11

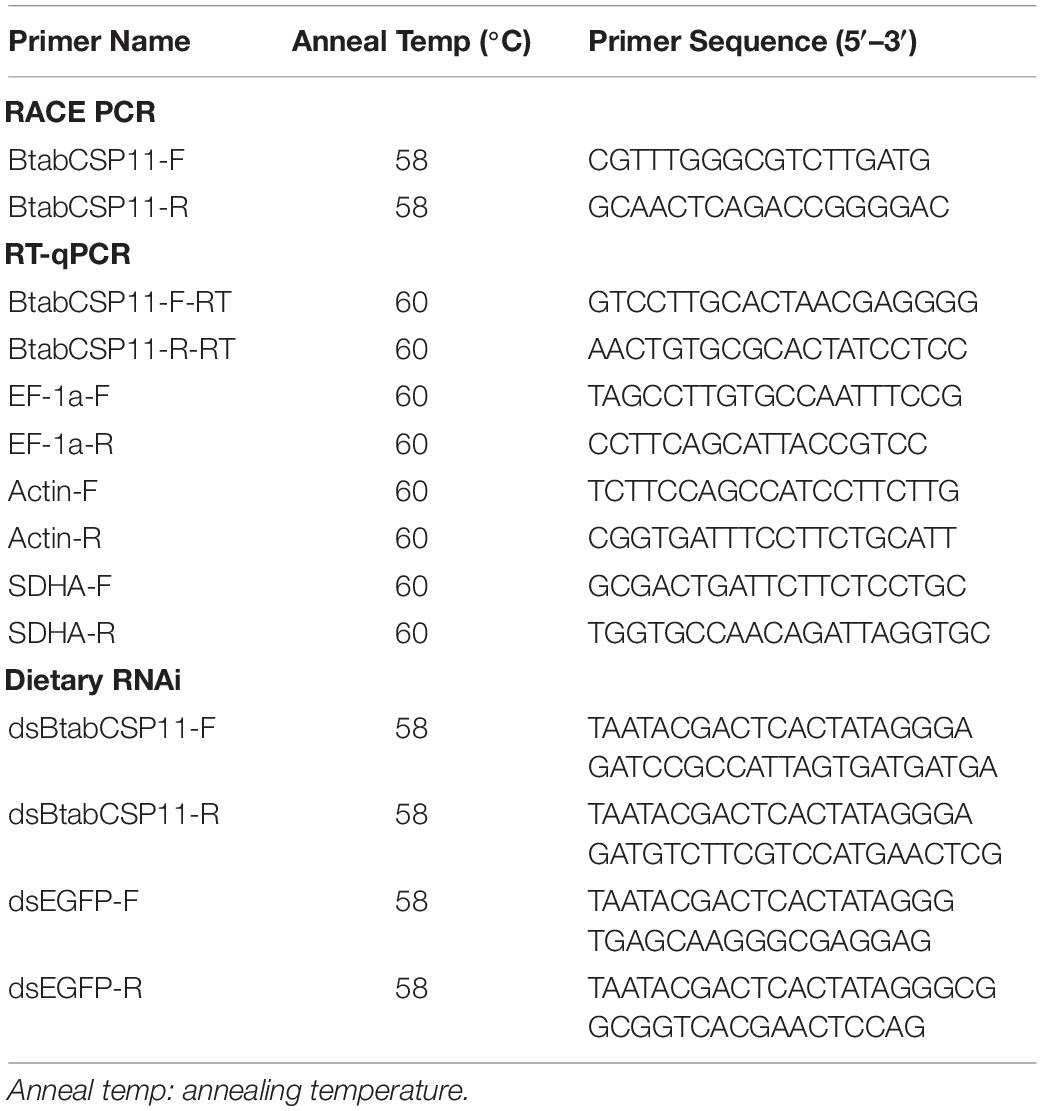

The full-length cDNA of BtabCSP11 contains a 408 bp open reading frame (ORF) encoding 136 amino acids (GenBank number: XP_018916537.1) with a 16.2 kDa molecular weight. There is a signal peptide with 18 residues at the N-terminus of BtabCSP11. Consistent with a classical model Cys-X6-8-Cys-X16-21-Cys-X2-4-Cys, BtabCSP11 has four conserved cysteine residues and six α-helices (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. WebLogo alignment of BtabCSP11 with six other hemipteran CSPs. “*”denotes highly conserved cysteines. N, N-terminus, C, C-terminus.

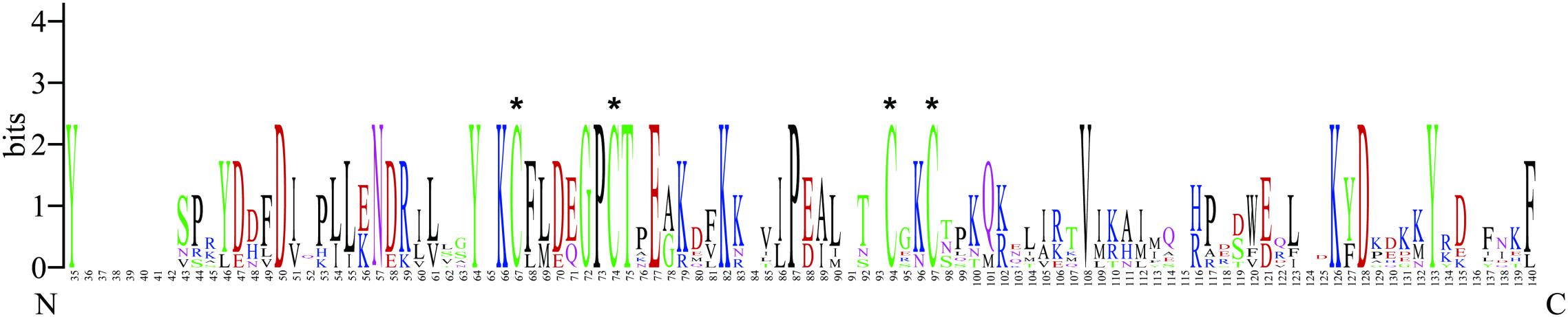

The CSP11 genes of other insect species were chosen for multiple sequence alignment with BtabCSP11 (Supplementary Table S1). A total of seven CSPs with >40% sequence similarity with BtabCSP11 (Pelosi et al., 2018), including DhouCSP, DvitCSP8, DkikCSP, CmedCSP3, PrapCSP10, and CbowCSP7, were included in the WebLogo alignment (Figure 1). The results of the alignment showed four highly conserved cysteine residues at positions 67, 74, 94, and 97; other positions such as 35 (Y), 50 (D), 57 (N), 64 (Y), 66 (K), 72 (G), 73 (P), 75 (T), 77 (E), 82 (K), 87 (P), 108 (V), 126 (K), 128 (D), and 133 (Y) were also highly conserved. The complete sequence alignment including all insect CSP11s is displayed in Supplementary Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the hemipteran CSPs formed four large branches, of which BtabCSP11, MperCSP4, DvitCSP8, and AgosCSP8 were clustered into one group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree comparing BtabCSP11 with known hemipteran CSPs. Species were grouped by different colors. Bootstrap values were calculated with 1,000 replications, and bootstraps were marked on the nodes (0–40 gray, 40–80 yellow, 80–100 red). The protein names and sequences of the 200 CSPs used in this analysis are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Alin = Adelphocoris lineolatus, Agos = Aphis gossypii, Aluc = Apolygus lucorum, Mper = Myzus persicae, Nlug = Nilaparvata lugens, Sfur = Sogatella furcifera, Ccil = Corythucha ciliata, Syan = Subpsaltria yangi, Asut = Adelphocoris suturalis, Lhes = Lygus Hesperus, Save = Sitobion avenae, Lstr = Laodelphax striatellus, Nvir = Nezara viridula, Hthe = Helopeltis theivora, Ysig = Yemma signatus, Cliv = Cyrtorhinus lividipennis, Eonu = Empoasca onukii, Tele = Tropidothorax elegans, Rped = Riptortus pedestris, Llin = Lygus lineolaris, Dvit = Daktulosphaira vitifoliae and Btab = Bemsia tabaci.

Temporospatial Expression Profiles of BtabCSP11

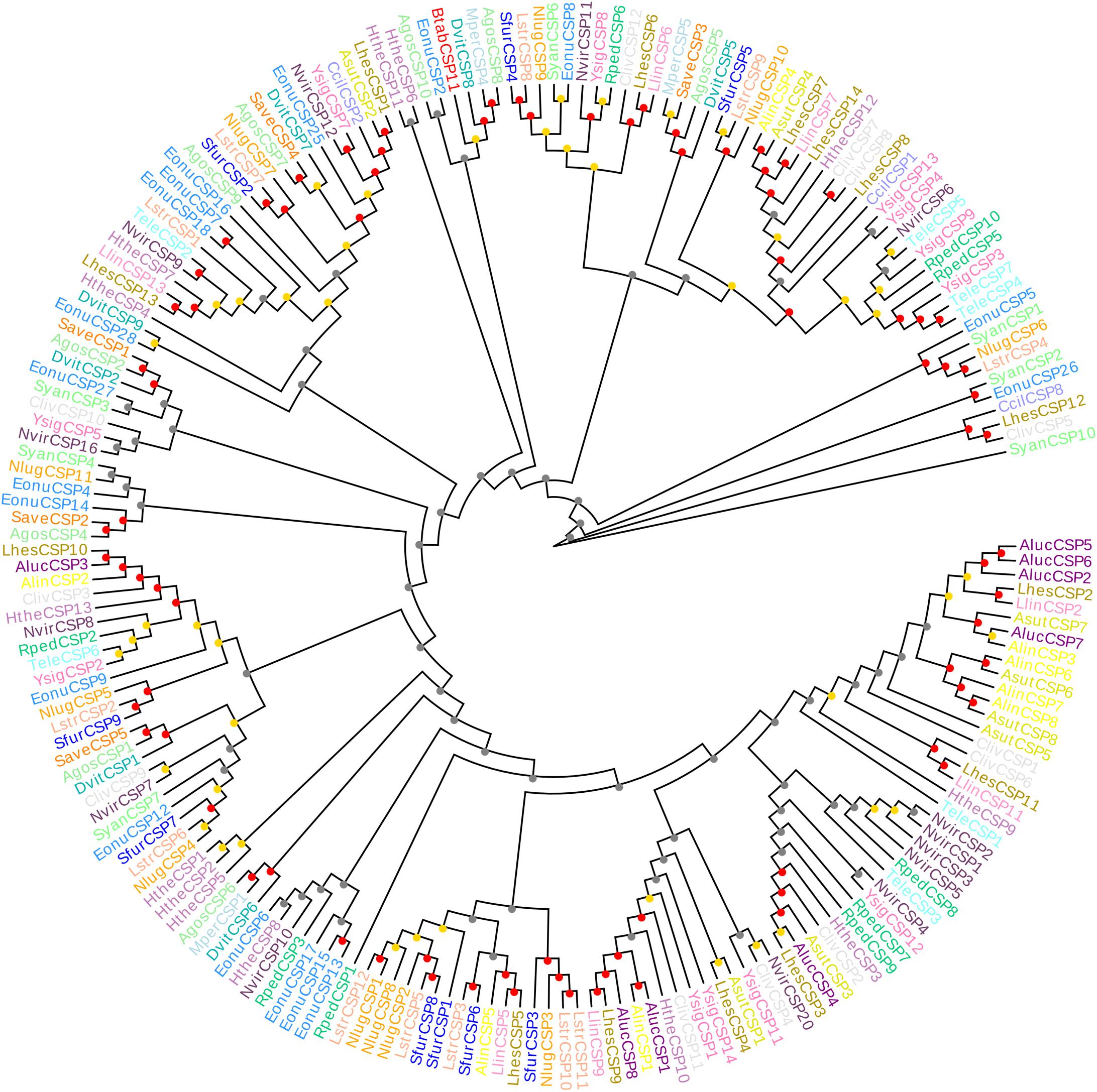

The transcriptomic profiles of BtabCSP11 were confirmed by RT-qPCR analysis (P < 0.05 r = 0.908, Figure 3A). Among different developmental stages, BtabCSP11 expression was significantly higher in adult females (F = 76.988, P < 0.0001), and there were no significant differences among the remaining developmental stages (Figure 3A). Among different tissue types, BtabCSP11 expression was significantly higher in abdomen tissue than in head and thorax tissue (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Temporospatial expression profiles of BtabCSP11. (A) Expression analysis of the BtabCSP11 gene by RT-qPCR (black bars) and RNA-seq (black lines). E = egg, N = nymph stages 1–4 as indicated, F = adult female, and M = adult male. (B) B. tabaci BtabCSP11 gene transcript levels in different tissue types. Standard error for each sample is represented by error bar and different letters (a, b, c) above each bar denote significant differences (P < 0.05).

Functional Analysis of BtabCSP11

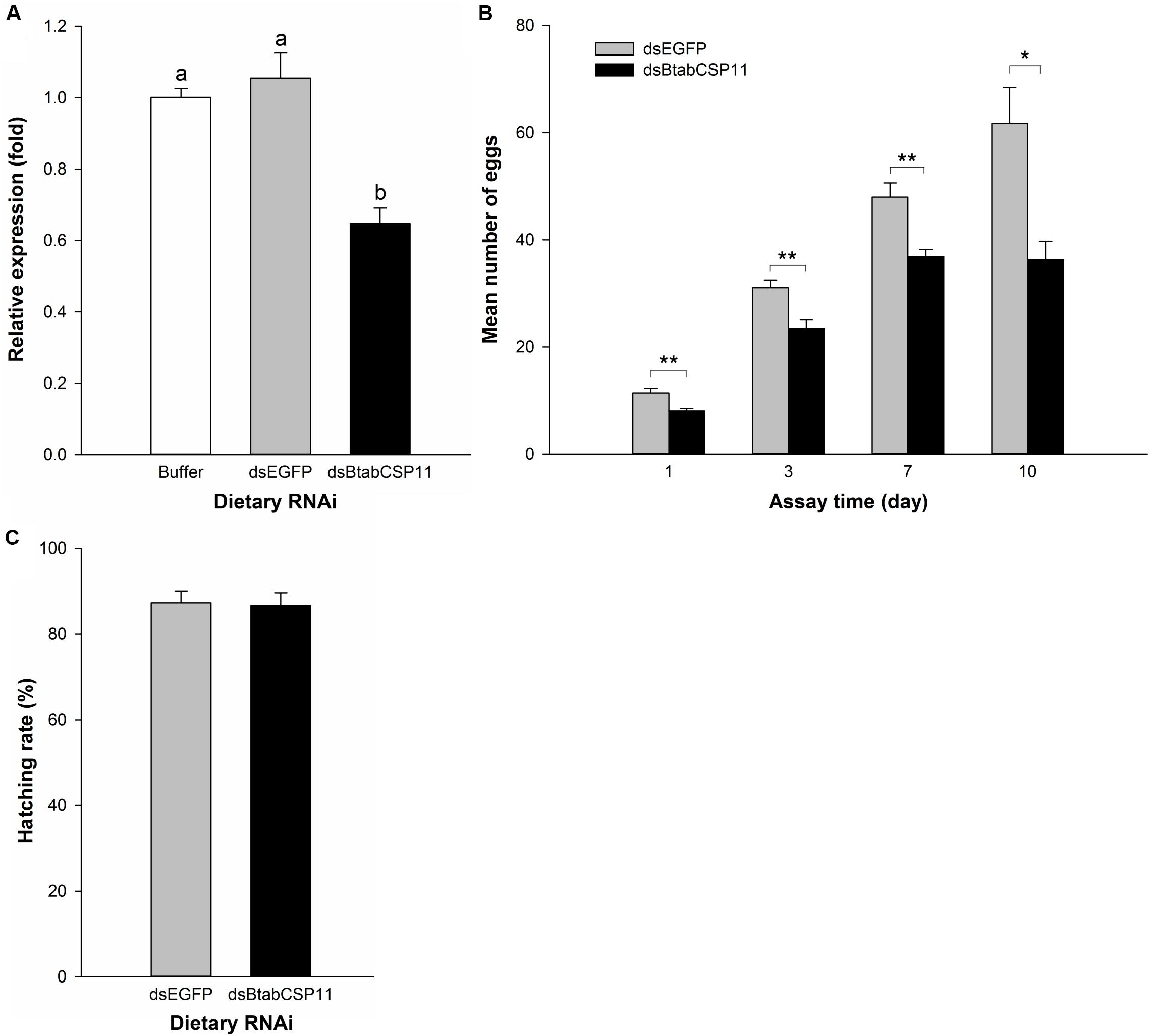

To explore the function of BtabCSP11 in B. tabaci, we silenced this gene using dietary RNAi. In comparison to control groups, BtabCSP11 expression in dsBtabCSP11-treated groups was suppressed significantly at 48 h post-feeding (Figure 4A). The total number of eggs laid by dsBtabCSP11 females at days 1, 3, 7, and 10 post-feeding was significantly lower than that in controls (P < 0.05; Figure 4B). There was no significant difference in hatching rate between the treatment (dsBtabCSP11) and control (dsEGFP) groups (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Dietary RNAi-based functional analysis of BtabCSP11 (A) Silencing of BtabCSP11 gene expression by dietary RNAi. Suppression of BtabCSP11 expression after B. tabaci MED adult females fed on dsRNA for 48 h. Expression of the BtabCSP11 gene was detected by RT-qPCR with EF1 –α and actin as the reference genes. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05; n = 3). (B) Effect of BtabCSP11 silencing on B. tabaci female reproduction. Values marked with “*” are significantly different based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test). (C) Hatching rate.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the genetic sequence of BtabCSP11 in B. tabaci and found that BtabCSP11 has four conserved cysteines and six helices connected by α-α loops (Wanner et al., 2004). BtabCSP11 displayed about 40% sequence similarity to the CSPs of phylogenetically distant species such as the cabbage beetle Colaphellus bowringi (Pelosi et al., 2005, 2018).

Kulmuni and Havukainen (2013) showed that 5-helical CSPs are the only highly conserved CSPs in Arthropoda and are likely involved in functions other than chemosensation, whereas the vastly divergent 6-helical CSPs carry out solely chemosensory functions. Evidence strongly suggests that CSPs might be involved in chemodetection, as are OBPs (Waris et al., 2018, 2020b). In the honeybee, CSP3 specifically binds some components of brood pheromone (Briand et al., 2002). In the paper wasp Polistes dominulus (Calvello et al., 2003), the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans morsitans (Liu et al., 2012), and several species of ants, some CSPs are specifically expressed in antennae (McKenzie et al., 2014) and have been proposed to be associated with host-seeking behavior. In the plant bug Adelphocoris lineolatus, three CSPs have high binding affinity with host-related chemicals (Gu et al., 2012). Similarly, SinfCSP19 plays a role in the reception of host plant volatiles by the stem borer Sesamia inferens (Zhang et al., 2014). In the planthopper Nilaparvata lugens, NlugCSP10 may detect volatiles emitted from host plants (Waris et al., 2020a). In addition to host plant volatiles, study has reported that insect CSPs can bind β-carotene (Zhu et al., 2016).

CSPs are widely expressed in the head, thorax, abdomen, legs, wings, testes and ovaries (Gong et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2007). This expression pattern indicates that CSPs may be involved in a variety of physiological processes. Previous reports show that CSPs have many functions outside of simply transporting and binding odor molecules. For example, studies have shown that CSPs are involved in the growth and development of honeybees, the molting process of ant larvae, the reproduction of the beet armyworm S. exigua, and insecticide resistance in the mosquito A. gambiae (Maleszka et al., 2007; Gong et al., 2012; Pelosi et al., 2018; Ingham et al., 2019). Inhibition of CSP9 expression by RNAi affects fatty acid biosynthesis and prevents cuticle development in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Cheng et al., 2015). In addition, some CSPs act as carriers of visual pigments, as in the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Zhu et al., 2016). CSPs have also been found to play roles in the reproductive processes of insects, such that a decrease in CSP gene expression negatively affects reproduction (Gong et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2019).

Given that phylogenetic analysis clustered BtabCSP11 with MperCSP4, DvitCSP8, and AgosCSP8, additional functional studies are warranted to resolve the evolutionary relationship within this group. This kind of evolutionary relationship also occurs among other insects (Vieira and Rozas, 2011; Eyun et al., 2017). Additional functional studies should be carried out to understand the evolutionary history of CSPs in Hemiptera.

Our temporospatial distribution study demonstrated that BtabCSP11 was highly expressed in the abdomens of adult females, suggesting a potential role in reproduction. Our dietary RNAi-based functional study confirmed that silencing of BtabCSP11 significantly reduced oviposition in B. tabaci (Figure 4). Similarly, Gong et al. (2012) reported that silencing of CSP3 in S. exigua led to a 71.4% reduction in oviposition in comparison to uninjected controls. In addition, silencing of CSP12 in the leaf beetle Ophraella communa resulted in a 28% reduction in the number of eggs laid (Ma et al., 2019). Potential causes for this change include altered reproductive behavior (e.g., mating and oviposition). In this study, however, males were not included and females were not provided a choice of oviposition site. Therefore, we hypothesize that BtabCSP11 may affect the oviposition behavior of B. tabaci.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

The research was designed by WX and YJZ. The experiments were conceived by YZ. Data was analyzed by YZ, LK, and XZ. Manuscript was drafted by YZ. Manuscript was revised and finalized by WX, XZ, AM, SW, QW, LK, and YJZ. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFD1002100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672032 and 31871970), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-24-C-02), the Beijing Key Laboratory for Pest Control and Sustainable Cultivation of Vegetables and the Science, and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.00709/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Ban, L., Scaloni, A., Brandazza, A., Angeli, S., Zhang, L., Yan, Y., et al. (2003). Chemosensory proteins of Locusta migratoria. Insect Mol. Biol. 12, 125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00394.x

Baum, J. A., Bogaert, T., Clinton, W., Heck, G. R., Feldmann, P., Ilagan, O., et al. (2007). Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1322–1326. doi: 10.1038/nbt1359

Berger, D., Walters, R., and Gotthard, K. (2008). What limits insect fecundity? Body size- and temperature-dependent egg maturation and oviposition in a butterfly. Funct. Ecol. 22, 523–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01392.x

Briand, L., Nespoulous, C., Huet, J. C., Takahashi, M., and Pernollet, J. C. (2002). Characterization of a chemosensory protein (ASP3c) from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) as a brood pheromone carrier. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 4586–4596. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03156.x

Calvello, M., Guerra, N., Brandazza, A., D’ambrosio, C., Scaloni, A., Dani, F., et al. (2003). Soluble proteins of chemical communication in the social wasp Polistes dominulus. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60, 1933–1943. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3186-5

Cheng, D., Lu, Y., Zeng, L., Liang, G., and He, X. (2015). Si-CSP9 regulates the integument and moulting process of larvae in the red imported ?re ant, Solenopsis invicta. Sci. Rep. 5:9245. doi: 10.1038/srep09245

Chu, D., Wan, F. H., Zhang, Y. J., and Brown, J. K. (2010). Change in the biotype composition of Bemisia tabaci in Shandong province of China from 2005 to 2008. Environ. Entomol. 39, 1028–1036. doi: 10.1603/En09161

Cui, H. H., Gu, S. H., Zhu, X. Q., Wei, Y., Liu, H. W., Khalid, H. D., et al. (2017). Odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins identified in the antennal transcriptome of Adelphocoris suturalis Jakovlev. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 24, 139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2016.03.001

Dani, F. R., Michelucci, E., Francese, S., Mastrobuoni, G., Cappellozza, S., La Marca, G., et al. (2011). Odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in pheromone detection and release in the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Chem. Senses 36, 335–344. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq137

De Barro, P. J., Liu, S. S., Boykin, L. M., and Dinsdale, A. B. (2011). Bemisia tabaci: a statement of species status. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085504

Elbert, A., and Nauen, R. (2000). Resistance of Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) to insecticides in southern Spain with special reference to neonicotinoids. Pest Manag. Sci. 56, 60–64. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1526-4998(200001)56:1<60::AID-PS88<3.0.CO;2-K

Eyun, S. I., Soh, H. Y., Posavi, M., Munro, J. B., Hughes, D. S. T., Murali, S. C., et al. (2017). Evolutionary history of chemosensory-related gene families across the arthropoda. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1838–1862. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx147

Ghanim, M., Kontsedalov, S., and Czosnek, H. (2007). Tissue-specific gene silencing by RNA interference in the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.04.006

Gilbertson, R. L., Batuman, O., Webster, C. G., and Adkins, S. (2015). Role of the insect supervectors Bemisia tabaci and Frankliniella occidentalis in the emergence and global spread of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2, 67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085410

Gong, D. P., Zhang, H. J., Zhao, P., Lin, Y., Xia, Q. Y., and Xiang, Z. H. (2007). Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.11.012

Gong, L., Luo, Q., Rizwan-ul-Haq, M., and Hu, M. Y. (2012). Cloning and characterization of three chemosensory proteins from Spodoptera exigua and effects of gene silencing on female survival and reproduction. Bull. Entomol. Res. 102, 600–609. doi: 10.1017/S0007485312000168

Gong, L., Zhong, G. H., Hu, M. Y., Luo, Q., and Ren, Z. Z. (2010). Molecular cloning, expression profile and 5’ regulatory region analysis of two chemosensory protein genes from the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. J. Insect Sci. 10, 1–15. doi: 10.1673/031.010.14103

Gu, S. H., Wang, S. Y., Zhang, X. Y., Ji, P., Liu, J. T., Wang, G. R., et al. (2012). Functional characterizations of chemosensory proteins of the alfalfa plant bug Adelphocoris lineolatus indicate their involvement in host recognition. PLoS One 7:e42871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042871

Gu, S. H., Wu, K. M., Guo, Y. Y., Field, L. M., Pickett, J. A., Zhang, Y. J., et al. (2013). Identification and expression profiling of odorant binding proteins and chemosensory proteins between two wingless morphs and a winged morph of the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii Glover. PLoS One 8:e73524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073524

He, Z. L., Zhang, H. K., Gao, S. H., Lercher, M. J., Chen, W. H., and Hu, S. N. (2016). Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W236–W241. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw370

Horowitz, A. R., Kontsedalov, S., and Ishaaya, I. (2004). Dynamics of resistance to the neonicotinoids acetamiprid and thiamethoxam in Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 97, 2051–2056. doi: 10.1093/jee/97.6.2051

Ingham, V. A., Anthousi, A., Douris, V., Harding, N. J., Lycett, G., Morris, M., et al. (2019). A sensory appendage protein protects malaria vectors from pyrethroids. Nature 577, 376–380. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1864-1

Iovinella, I., Bozza, F., Caputo, B., della Torre, A., and Pelosi, P. (2013). Ligand-binding study of Anopheles gambiae chemosensory proteins. Chem. Senses 38, 409–419. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt012

Jin, X., Brandazza, A., Navarrini, A., Ban, L., Zhang, S., Steinbrecht, R. A., et al. (2005). Expression and immunolocalisation of odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins in locusts. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 1156–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5014-6

Kulmuni, J., and Havukainen, H. (2013). Insights into the evolution of the CSP gene family through the integration of evolutionary analysis and comparative protein modeling. PLoS One 8:e63688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063688

Li, R., Xie, W., Wang, S., Wu, Q., Yang, N., Yang, X., et al. (2013). Reference gene selection for qRT-PCR analysis in the sweetpotato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). PLoS One 8:e53006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053006

Li, Y., Qin, Y., Gao, Z., Dang, Z., Pan, W., and Xu, G. (2012). Cloning, expression and characterisation of a novel gene encoding a chemosensory protein from Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11, 758–770. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.573

Liu, G., Ma, H., Xie, H., Xuan, N., Guo, X., Fan, Z., et al. (2016). Biotype characterization, developmental profiling, insecticide response and binding property of Bemisia tabaci chemosensory proteins: role of CSP in insect defense. PLoS One 11:e0154706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154706

Liu, G. X., Xuan, N., Chu, D., Xie, H. Y., Fan, Z. X., Bi, Y. P., et al. (2014). Biotype expression and insecticide response of Bemisia tabaci chemosensory protein-1. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 85, 137–151. doi: 10.1002/arch.21148

Liu, R., He, X., Lehane, S., Lehane, M., Hertz-Fowler, C., Berriman, M., et al. (2012). Expression of chemosensory proteins in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans morsitans is related to female host-seeking behaviour. Insect Mol. Biol. 21, 41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01114.x

Lu, D., Li, X., Liu, X., and Zhang, Q. (2007). Identification and molecular cloning of putative odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory protein from the bethylid wasp, Scleroderma guani Xiao et Wu. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 1359–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10886-007-9310-5

Ma, C., Cui, S., Tian, Z., Zhang, Y., Chen, G., Gao, X., et al. (2019). OcomCSP12, a chemosensory protein expressed specifically by ovary, mediates reproduction in Ophraella communa (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Front. Physiol. 10:1290. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01290

Maleszka, J., Foret, S., Saint, R., and Maleszka, R. (2007). RNAi-induced phenotypes suggest a novel role for a chemosensory protein CSP5 in the development of embryonic integument in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0127-y

Maleszka, R., and Stange, G. (1997). Molecular cloning, by a novel approach, of a cDNA encoding a putative olfactory protein in the labial palps of the moth Cactoblastis cactorum. Gene 202, 39–43. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00448-4

Mao, Y. B., Cai, W. J., Wang, J. W., Hong, G. J., Tao, X. Y., Wang, L. J., et al. (2007). Silencing a cotton bollworm P450 monooxygenase gene by plant-mediated RNAi impairs larval tolerance of gossypol. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt1352

Marchese, S., Angeli, S., Andolfo, A., Scaloni, A., Brandazza, A., Mazza, M., et al. (2000). Soluble proteins from chemosensory organs of Eurycantha calcarata (Insects, Phasmatodea). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30, 1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00084-9

McKenzie, S. K., Oxley, P. R., and Kronauer, D. J. (2014). Comparative genomics and transcriptomics in ants provide new insights into the evolution and function of odorant binding and chemosensory proteins. BMC Genomics 15:718. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-718

Nagnan-Le Meillour, P., Cain, A. H., Jacquin-Joly, E., Francois, M. C., Ramachandran, S., Maida, R., et al. (2000). Chemosensory proteins from the proboscis of Mamestra brassicae. Chem. Senses 25, 541–553. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.5.541

Pelosi, P., Calvello, M., and Ban, L. (2005). Diversity of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in insects. Chem. Senses 30(Suppl. 1), i291–i292. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh229

Pelosi, P., Iovinella, I., Felicioli, A., and Dani, F. R. (2014). Soluble proteins of chemical communication: an overview across arthropods. Front. Physiol. 5:320. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00320

Pelosi, P., Iovinella, I., Zhu, J., Wang, G., and Dani, F. R. (2018). Beyond chemoreception: diverse tasks of soluble olfactory proteins in insects. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 93, 184–200. doi: 10.1111/brv.12339

Pelosi, P., Zhou, J. J., Ban, L. P., and Calvello, M. (2006). Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1658–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0

Qi, M., Wei, S., and Wei, C. (2018). Identification of candidate olfactory genes in cicada Subpsaltria yangi by antennal transcriptome analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 28, 122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2018.08.001

Raabe, M. (1987). Insect reproduction: regulation of successive steps. Adv. Insect Physiol. 19, 29–154. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2806(08)60100-9

Sun, L., Zhou, J. J., Gu, S. H., Xiao, H. J., Guo, Y. Y., Liu, Z. W., et al. (2015). Chemosensillum immunolocalization and ligand specificity of chemosensory proteins in the alfalfa plant bug Adelphocoris lineolatus (Goeze). Sci. Rep. 5:8073. doi: 10.1038/srep08073

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., and Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

Upadhyay, S. K., Chandrashekar, K., Thakur, N., Verma, P. C., Borgio, J. F., Singh, P. K., et al. (2011). RNA interference for the control of whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci) by oral route. J. Biosci. 36, 153–161. doi: 10.1007/s12038-011-9009-1

Vieira, F. G., and Rozas, J. (2011). Comparative genomics of the odorant-binding and chemosensory protein gene families across the Arthropoda: origin and evolutionary history of the chemosensory system. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 476–490. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr033

Wan, F. H., and Yang, N. W. (2016). Invasion and management of agricultural alien insects in China. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 61, 77–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023916

Wang, R., Li, F., Zhang, W., Zhang, X., Qu, C., Tetreau, G., et al. (2017). Identification and expression profile analysis of odorant binding protein and chemosensory protein genes in Bemisia tabaci MED by head transcriptome. PLoS One 12:e0171739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171739

Wang, Z., Yan, H., Yang, Y., and Wu, Y. (2010). Biotype and insecticide resistance status of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci from China. Pest Manag. Sci. 66, 1360–1366. doi: 10.1002/ps.2023

Wanner, K. W., Willis, L. G., Theilmann, D. A., Isman, M. B., Feng, Q., and Plettner, E. (2004). Analysis of the insect os-d-like gene family. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 889–911. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000028457.51147.d4

Waris, M. I., Younas, A., Adeel, M. M., Duan, S. G., Quershi, S. R., Kaleem, U. R. M., et al. (2020a). The role of chemosensory protein 10 in the detection of behaviorally active compounds in brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Insect Sci. 27, 531–544. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12659

Waris, M. I., Younas, A., Ameen, A., Rasool, F., and Wang, M. Q. (2020b). Expression profiles and biochemical analysis of chemosensory protein 3 from Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 46, 363–377. doi: 10.1007/s10886-020-01166-6

Waris, M. I., Younas, A., Ul Qamar, M. T., Hao, L., Ameen, A., Ali, S., et al. (2018). Silencing of chemosensory protein gene NlugCSP8 by RNAi induces declining behavioral responses of Nilaparvata lugens. Front. Physiol. 9:379. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00379

Xie, W., Chen, C., Yang, Z., Guo, L., Yang, X., Wang, D., et al. (2017). Genome sequencing of the sweetpotato whitefly Bemisia tabaci MED/Q. GigaScience 6:1. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix018

Xu, Y. L., He, P., Zhang, L., Fang, S. Q., Dong, S. L., Zhang, Y. J., et al. (2009). Large-scale identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins from expressed sequence tags in insects. BMC Genomics 10:632. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-632

Xue, W., Fan, J., Zhang, Y., Xu, Q., Han, Z., Sun, J., et al. (2016). Identification and expression analysis of candidate odorant-binding protein and chemosensory protein genes by antennal transcriptome of Sitobion avenae. PLoS One 11:e0161839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161839

Zeng, Y., Yang, Y. T., Wu, Q. J., Wang, S. L., Xie, W., and Zhang, Y. J. (2019). Genome-wide analysis of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. Insect Sci. 26, 620–634. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12576

Zhang, Y. N., Ye, Z. F., Yang, K., and Dong, S. L. (2014). Antenna-predominant and male-biased CSP19 of Sesamia inferens is able to bind the female sex pheromones and host plant volatiles. Gene 536, 279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.011

Zheng, H. X., Xie, W., Wang, S. L., Wu, Q. J., Zhou, X. M., and Zhang, Y. J. (2017). Dynamic monitoring (B versus Q) and further resistance status of Q-type Bemisia tabaci in China. Crop Prot. 94, 115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.11.035

Keywords: chemosensory proteins, Bemisia tabaci, RNA interference, expression profiles, reproduction

Citation: Zeng Y, Merchant A, Wu Q, Wang S, Kong L, Zhou X, Xie W and Zhang Y (2020) A Chemosensory Protein BtabCSP11 Mediates Reproduction in Bemisia tabaci. Front. Physiol. 11:709. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00709

Received: 13 February 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020;

Published: 30 June 2020.

Edited by:

Bin Tang, Hangzhou Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Guohua Zhong, South China Agricultural University, ChinaSergio Angeli, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

Kai Lu, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Copyright © 2020 Zeng, Merchant, Wu, Wang, Kong, Zhou, Xie and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wen Xie, eGlld2VuQGNhYXMuY24=; Youjun Zhang, emhhbmd5b3VqdW5AY2Fhcy5jbg==

Yang Zeng1

Yang Zeng1 Qingjun Wu

Qingjun Wu Shaoli Wang

Shaoli Wang Wen Xie

Wen Xie Youjun Zhang

Youjun Zhang