95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 04 October 2019

Sec. Translational Pharmacology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01153

This article is part of the Research Topic Nanoantibiotics at the Backdrop of Emerging Antibiotic Resistance: Opportunities & Challenges View all 3 articles

Nanotechnology using nanoscale materials is increasingly being utilized for clinical applications, especially as a new paradigm for infectious diseases. Infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are emerging as causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Antibiotic options for infections caused by MDROs are often limited. These clinical challenges highlight the critical demand for alternative and effective antimicrobial strategies. Nanoparticles (NPs) can penetrate the cell membrane of pathogenic microorganisms and interfere with important molecular pathways, formulating unique antimicrobial mechanisms. In combination with optimal antibiotics, NPs have demonstrated synergy and may aid in limiting the global crisis of emerging bacterial resistance. In this review, we summarized current research on the broad classification of the NPs that have shown in vitro antimicrobial activity against MDROs, including the ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic characteristics of NPs and bacteria-resistant mechanisms to NPs were also discussed.

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are becoming a growing public health crisis and make many healthcare-associated infections difficult to treat with current antibiotics (Boucher et al., 2009; Peleg and Hooper, 2010). Globally, infections caused by MDROs are emerging causes of morbidity and mortality (Ismail et al., 2018; Kuo et al., 2018; Ting et al., 2018; Tsao et al., 2018). The development of new antibiotics requires tremendous economic and labor investment and is time-consuming (Huh and Kwon, 2011). For these MDRO infections, high doses of antibiotics will be administered and may generate intolerable toxic and adverse effects, which will prompt the development of alternative strategies.

The application of nanoparticles (NPs) provides a potential strategy to manage infections caused by MDROs (Singh et al., 2014; Natan and Banin, 2017; Baptista et al., 2018; Muzammil et al., 2018). In this respect, NPs have shown therapeutic promise owing to their unique physical and chemical attributes (Pelgrift and Friedman, 2013; Beyth et al., 2015; Hemeg, 2017). NPs exhibiting antibacterial activities can target multiple biomolecules and have the potential to reduce or eliminate the evolution of MDROs (Slavin et al., 2017). However, the translation of NPs to clinical use requires not only appropriate methods for the synthesis of NPs but also a thorough understanding of the physicochemical particularities, in vitro and in vivo effects, biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of NPs (Burdusel et al., 2018).

In this review, we will present a broad classification of the NPs that show in vitro antimicrobial activity against MDROs, and the synergistic effects of NPs with current available antibiotics, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics, and resistant mechanisms will also be discussed.

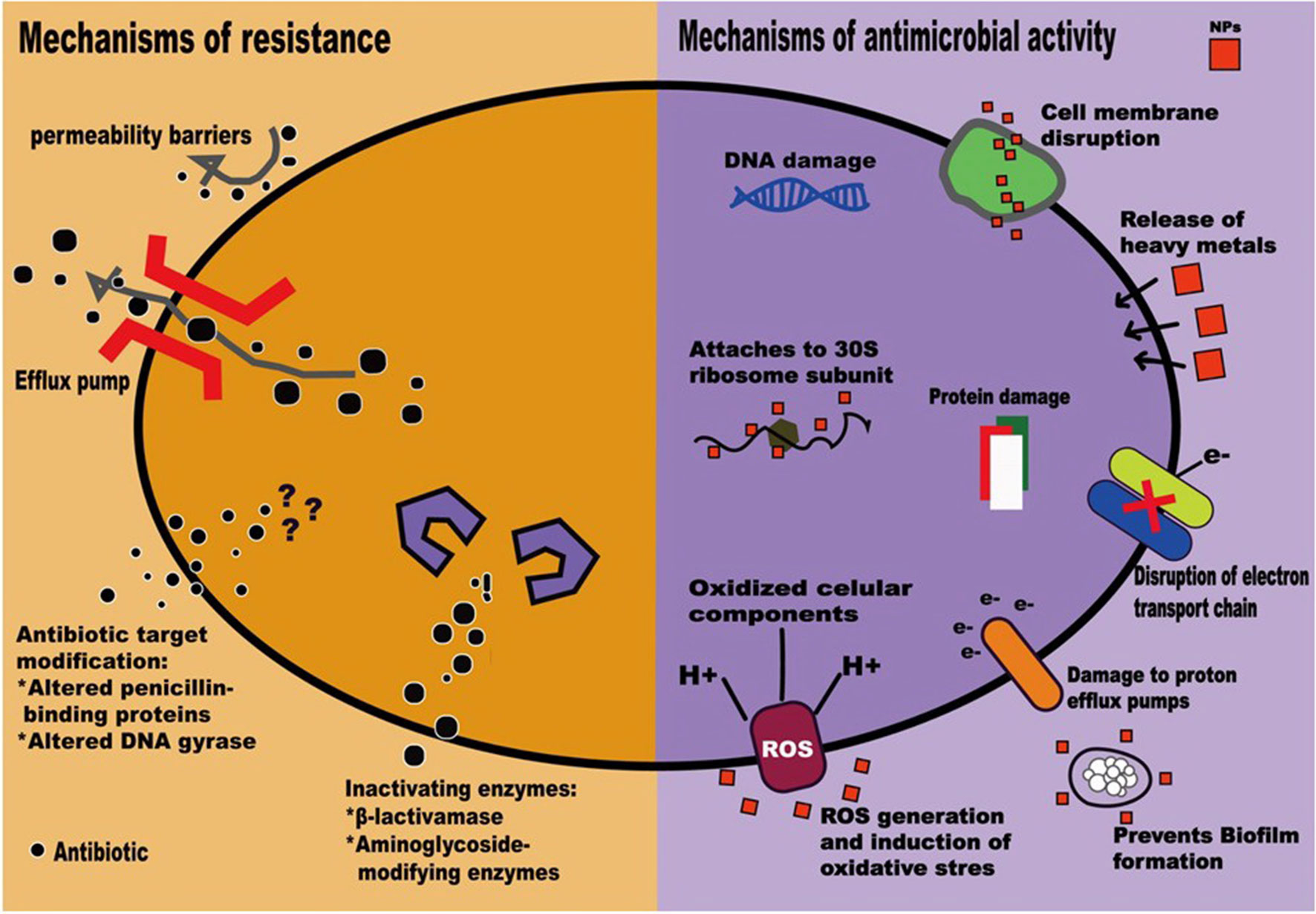

NPs possess antimicrobial activity that can overcome common resistant mechanisms, including enzyme inactivation, decreased cell permeability, modification of target sites/enzymes, and increased efflux through overexpression of efflux pumps, to escape from the antibacterial activity of antimicrobial agents (Mulvey and Simor, 2009; Baptista et al., 2018) (Figure 1). Moreover, NPs conjugated with antibiotics show synergistic effects against bacteria, prohibit biofilm formation, and have been utilized to combat MDROs (Pelgrift and Friedman, 2013; Baptista et al., 2018).

Figure 1 Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance (Mulvey and Simor, 2009) and actions of nanoparticles (Baptista et al., 2018).

Several characteristics of NPs make them alternatives to traditional antibiotics. First, the large surface-area-to-volume ratio of NPs increases the contact area with target organisms. NPs can act as nanoscale molecules interacting with bacterial cells, regulating cell membrane penetration, and interfering with molecular pathways (Rai et al., 2012; Dakal et al., 2016; Duran et al., 2016; Hemeg, 2017). Second, NPs may enhance the inhibitory effects of antibiotics. Saha et al. (2007) demonstrated that gold NPs conjugated with ampicillin, streptomycin, or kanamycin could lower the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the antibiotic counterparts against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Likewise, Gupta et al. (2017) demonstrated a synergistic effect of functionalized Au NPs and fluoroquinolone antibiotics for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli infections. However, the complexity of the physicochemical properties, including size, shape, chemical modification, solvent, and environmental factors, can affect the antibacterial properties of NPs during preparation of NPs and interact with bacteria (Beyth et al., 2015). Finally, combinations of antibiotics and NPs provide complex antimicrobial mechanisms to overcome antibiotic resistance (Huh and Kwon, 2011). Gupta et al. (2017) demonstrated a synergistic effect using functionalized Au NPs and fluoroquinolone antibiotics for the treatment of multidrug-resistant E. coli bacterial strains.

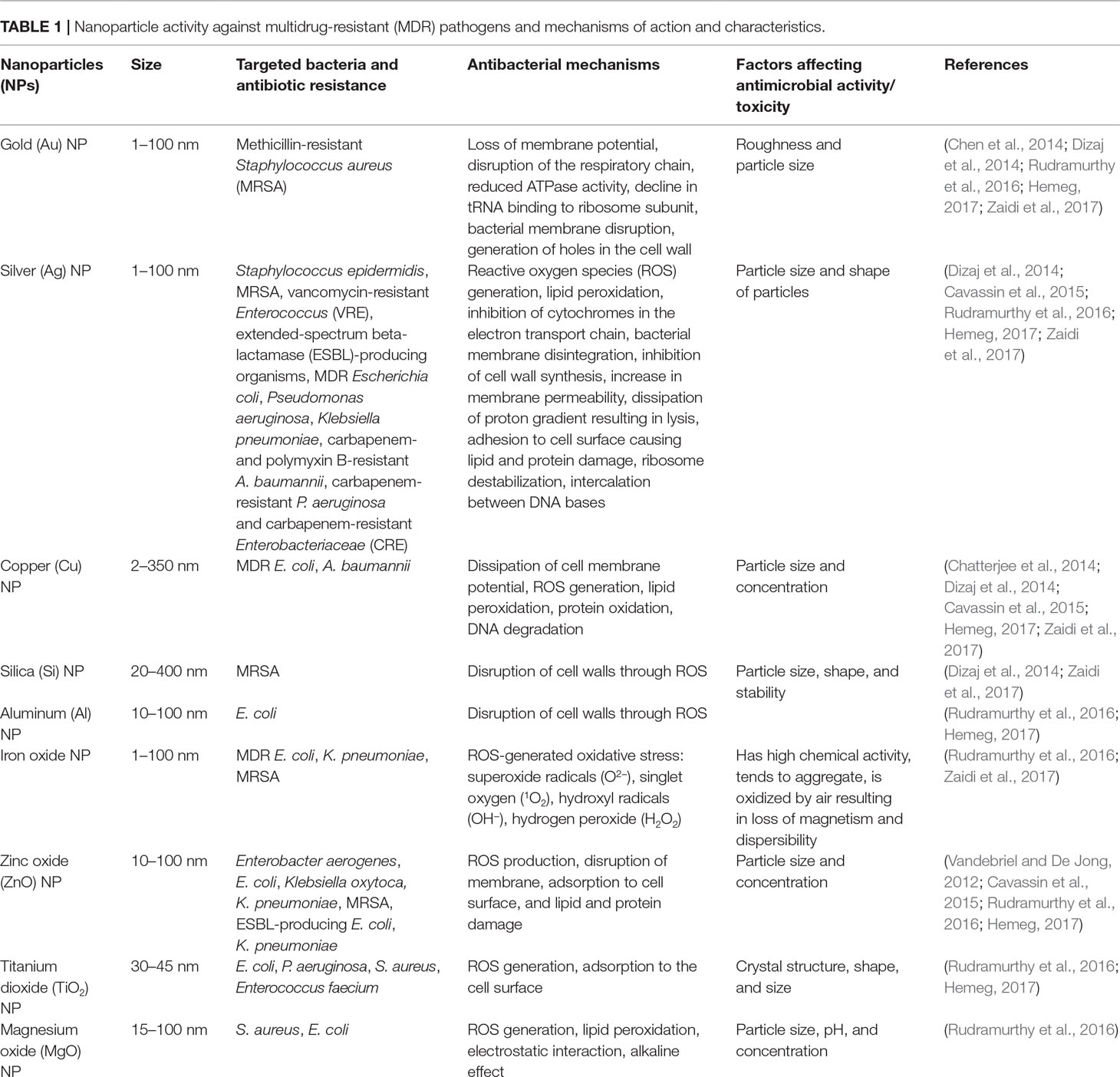

NPs are therefore regarded as next-generation antibiotics. In both in vitro and in vivo studies, NPs, mainly metallic, have been shown to exhibit activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Zazo et al., 2016). Though antimicrobial mechanisms that depend on the size, shape, ζ-potential, ligands, and material used are not well understood (Huh and Kwon, 2011; Singh et al., 2014; Zazo et al., 2016); currently accepted mechanisms include (1) direct interaction with the bacteria, leading to the disruption of membrane potential and integrity; (2) triggering of the host immune responses; (3) inhibition of biofilm formation; (4) generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); and (5) inhibition of RNA and protein synthesis through the induction of intracellular effects (Pelgrift and Friedman, 2013; Beyth et al., 2015) (Figure 1). NP coatings on implantable devices, wound dressings, bone cement, or dental materials can function as NP-based antibiotic delivery systems (Wang et al., 2017). Furthermore, NPs can be vectors to transfer drugs so that higher doses of antimicrobial agents can be delivered to infected sites (Pelgrift and Friedman, 2013). Thus, the combination of NPs and antimicrobial agents may be beneficial in fighting the ongoing crisis of antimicrobial resistance (Baptista et al., 2018). Clinical applications of NPs have recently been evaluated to highlight the in vitro antimicrobial activities of NPs and the potential adverse effects of NPs on human health (Table 1).

Table 1 Nanoparticle activity against multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and mechanisms of action and characteristics.

NPs with antimicrobial activity that combats Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species (Ansari et al., 2014; Dizaj et al., 2014; Beyth et al., 2015; Hemeg, 2017) include NPs containing Ag, Au, Zn, Cu, Ti, Mg, Ni, Ce, Se, Al, Cd, Y, Pd, or superparamagnetic Fe (Hemeg, 2017). The antimicrobial activities against MDROs, mechanisms of action, and characteristics of various NPs are shown in Table 1. Among various metallic NPs and their oxides already applied as active antimicrobial agents, silver or its ionic form is the most toxic to bacteria (Seil and Webster, 2012). This makes silver of particular interest. Silver NPs (Ag NPs) are used to a great extent since they have multiple mechanisms of antibacterial action (Cheng et al., 2016), high biocompatibility, and functionalized potential and are easy to detect (Baranwal et al., 2018). Although Ag NPs are difficult to functionalize with biomolecules and antibiotics, Ag–gold (Au) alloys provide another path, since they combine the antimicrobial effects of Ag with the effectiveness of functionalization and the stability of Au in the form of bimetallic NPs (Baptista et al., 2018). Furthermore, Ag–Au NPs functionalized with tetracycline have been shown to have a synergetic effect, which is attributed to the generation of ROS (Fakhri et al., 2017).

Ag NPs and Au NPs may exhibit decreased antibacterial activity when their surfaces are modified (Rai et al., 2012; Dakal et al., 2016; Duran et al., 2016; Hemeg, 2017), and copper (Cu) NPs with modified surfaces lose antimicrobial activity and fail to change the morphology of microbial cells (Baranwal et al., 2018). However, most metallic NPs, through the release of toxic ions, inflammatory cytokines, and the generation of ROS, may cause immunotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity in both healthy and infected cells (Schrand et al., 2010; Ding et al., 2015).

Au–Pt bimetallic NPs have antibacterial activity against multidrug‐resistant E. coli through the dissipation of bacterial membrane potential and the elevation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels (Baptista et al., 2018). Cu–Ni bimetallic NPs have been utilized as coating agents but have been used less in antimicrobial applications (Baptista et al., 2018)

With biocompatibility and magnetic properties, iron oxide (FeO) is well known in the biomedical sector. Recently, the antibacterial properties of reduced iron and FeO NPs that damage bacteria cells through the disruption of the bacterial membrane and generation of oxidative stress inside the cell have been studied (Baranwal et al., 2018). The characteristic compatibility and safety of ZnO NPs on human skin make them appropriate additives for cosmetics, fabrics, and surfaces in close proximity to human skin (Dizaj et al., 2014). Copper oxide (CuO) NPs have been shown to exhibit excellent bactericidal and fungicidal activity (Ren et al., 2009), whereas TiO2 NPs possess spectacular antimicrobial properties, mainly related to ROS formation, particularly –OH free radicals (Baranwal et al., 2018).

To overcome antibiotic resistance, NPs can be tailored and packaged with diverse antimicrobial agents. NPs act on bacteria through multiple targets and/or a unique mechanism; thus, antimicrobial resistance is unlikely to develop if NPs are combined with antibiotics since multiple simultaneous mutations are required in the same microorganism (Fischbach, 2011; Zhao and Jiang, 2013). The functionalization of NPs with antibiotics can be a promising regimen to combat bacterial resistance. Moreover, NPs can deliver antimicrobial agents to or target the infected sites and reduce the dosage and toxicity of antibiotics (Hemeg, 2017). For example, the synergistic antibacterial efficiency of Ag NPs and antibiotics against S. aureus, beta-lactamase- or carbapenemase-producing E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii strains at extremely low concentrations has been found (Naqvi et al., 2013; Panacek et al., 2015; Scandorieiro et al., 2016), whereas synergistic antibacterial effects of Ag, Au, and ZnO NPs and antibiotics have been observed against S. aureus, E. faecium, E. coli, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa through the penetration of the bacterial cell membrane and the interference with important molecular pathways, formulating unique antimicrobial mechanisms (Hemeg, 2017). The efficacy of antibiotics combined with NPs was identical in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, unlike the difficulty in killing MDROs with antibiotics alone (Hemeg, 2017). The combinations of antibiotics and functionalized Ag, Au, or ZnO NPs may promote the reversal of antimicrobial resistance and boost the antimicrobial effects of several antibiotics, including polymyxin B, ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, ampicillin, clindamycin, vancomycin, or erythromycin, against MDROs, including antibiotic-resistant A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, E. faecium; vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE); and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (Hemeg, 2017).

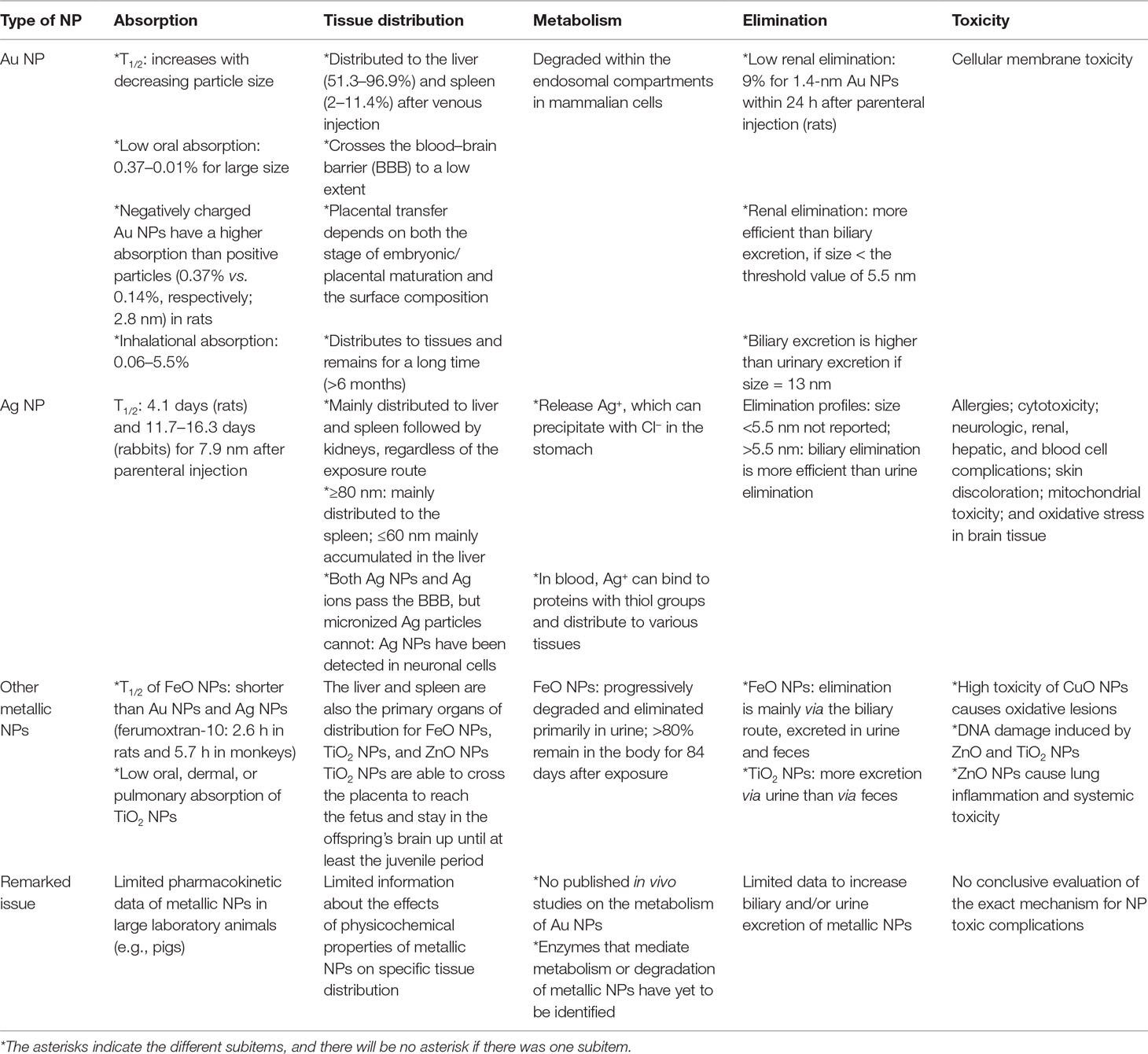

The pharmacokinetics of NPs depend on numerous aspects, such as the particle type, size, surface charge, surface coating, protein binding, exposure route, dose, and animal species. A comprehensive understanding of their pharmacokinetics is pivotal for risk assessment and biosafety in clinical practice (Lin et al., 2015). The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of NPs are summarized in Figure 2. The systemic or local activity and toxicity of NPs are dependent on the administration route and physicochemical characteristics, and chronic toxicity may be related to the complicated elimination pathway (Zazo et al., 2016). A summary of the present knowledge of the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of metallic NPs is provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Comparisons of the pharmacokinetic characteristics and toxicity of metallic nanoparticles (NPs).

The oral, dermal, or pulmonary absorption of Au NPs, Ag NPs, or TiO2 NPs is generally low (Table 2). The parenteral route is favored for targeting the liver or spleen. For muscle or skin targeting, the administrative route can be topical, intramuscular, intradermal, or subcutaneous, whereas oral or intranasal administration is used in the case of mucosal targeting (Zazo et al., 2016). For example, the absorption of Au NPs by inhalation ranges from 0.06% to 5.5%, depending on the size of the NP (Lin et al., 2015; Zazo et al., 2016). Oral absorption is approximately 0.01–5% for Au NPs, 1–4.2% for Ag NPs, and 0.01–0.05% for TiO2 NPs, depending on the size and coating (Lin et al., 2015).

Regardless of the particle type, most metallic NPs are distributed mainly in the liver and spleen, but the physicochemical properties of Au NPs could be modified to increase their distribution to specific target organs (Lin et al., 2015). However, long-term studies regarding a full interpretation of the toxicological implications of NP absorption and penetration through tissues are lacking (Lin et al., 2015).

The decision for the optimal dose is crucial for therapeutic targets and minimizing toxicity for medical translation (Khan et al., 2016; Hua et al., 2018). Thus far, the doses of nanomaterials causing cell damage in vitro are unrealistically high and are impossible to apply to humans (Khan et al., 2016). The data from animal studies may not be directly translated to human beings, and appropriate and realistic doses should be studied in the future (Khan et al., 2016; Hua et al., 2018). There have been few clinical studies on NP dosing. Munger et al. (2014) reported two oral doses (10 ppm with a size ranging from 5 to 10 nm and 32 ppm with a size ranging from 25 to 40 nm) of a commercial solution of Ag NP in healthy adult volunteers that did not prompt clinically significant changes in human metabolic and hematologic profiles, urine, physical findings, or imaging morphology based on comprehensive assays and tests. More clinical studies are warranted before the application of NPs to patients.

The elimination of metallic NPs via urinary and biliary pathways is generally low, which leads to their long-term accumulation in the liver and spleen (Lin et al., 2015). In addition, NPs do not undergo biodegradation into biologically benign components and thus exhibit prolonged tissue retention, eventually leading to amplified toxic effects (Zaidi et al., 2017). A higher accumulation of 10-nm NPs was observed in the kidneys, but this could be caused by a lessened availability of the larger NPs due to their high accumulations in the liver and spleen (Hoshyar et al., 2016).

The degree of opsonization of NPs by serum proteins is determined by the charge and size of the NPs. By opsonization, the in vivo hydrodynamic diameter (HD) or the effective size of NPs can be altered (Zaidi et al., 2017). The endothelium usually has a pore size of 5 nm, and particles with an HD smaller than 5 nm can equilibrate with the extravascular extracellular space (EES). Conversely, larger particles with slow movement across the endothelium remain in circulation for extended periods (Zaidi et al., 2017). The kidney can remove molecules from vascular compartments, but the particles in the range of 10–20 nm are excluded from renal filtration and are eliminated through the hepatobiliary system (Zaidi et al., 2017). The remaining particles that escape degradation by Kupffer cells will be retained in the body for prolonged periods (Zaidi et al., 2017). More studies are vital to explore the ways to increase biliary and/or urine elimination of NPs to reduce organ accumulation and potential toxicity (Lin et al., 2015).

The antimicrobial activity of NPs depends on several physicochemical properties, such as their size, shape, solubility, and ability to form free biocidal metal ions (Khan et al., 2016). Generally, smaller NPs show increased antibacterial activity compared to larger NPs (Lu et al., 2013). Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria differ in terms of cell membrane components and structures and have different adsorption pathways for NPs (Lesniak et al., 2013). The susceptibility of bacteria to NPs depends on their biochemical composition since different NPs target different biomolecules (Khan et al., 2016). Moreover, rapidly growing bacteria are more susceptible to NPs or antibiotics than slow-growing bacteria. This may be due to the variable expression of stress-response genes between rapidly growing and slow-growing bacteria (Stewart, 2002; Khan et al., 2016).

The antibacterial effects of NPs have been noted to be more pronounced for gram-positive bacteria than for gram-negative bacteria. Such a finding may be related to the fact that the nonporous cell walls of gram-negative bacteria serve as penetration barriers for the entry of NPs (Zaidi et al., 2017). Cell walls of gram-positive bacteria with covalent links with neighboring proteins and components are relatively porous and allow the penetration of foreign molecules (Zaidi et al., 2017).

Local and systemic toxic complications, as well as deleterious effects on beneficial bacteria in humans, are concerns for the use of NPs (Zhang et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2016). Both NPs themselves and toxic degradation products of NPs can cause hemolysis and interfere with blood coagulation pathways (Kandi and Kandi, 2015). The exact mechanism of toxic complications is unclear, but it has been observed that the larger the size of the NP is, the greater the risk of adverse health effects (Dos Santos et al., 2014). Among metal NPs, the toxicity of Ag NPs has been studied extensively, and Ag NPs were shown to be more toxic toward cell lines. However, most studies were performed in vitro (Bondarenko et al., 2013; Ivask et al., 2014). The deposition of Ag NPs in the liver, spleen, lungs, and other organs results in organ damage and dysfunction and seriously decreases their efficacy (Hemeg, 2017). Elevated Ag levels have been found in both blood and urine by the leaching of Ag from Acticoat®, a nanocrystalline Ag wound dressing, into the bloodstream (Khan et al., 2016) and were confirmed in burn patients (Vlachou et al., 2007). Al2O3 NPs that interact with cellular biomolecules and cause adverse effects of neurotoxicity could serve as broad-spectrum bactericidal agents, regardless of drug resistance mechanisms (Ansari et al., 2014). The oxidative damage of CuO NPs and DNA damage induced by ZnO NPs or TiO2 NPs limit their use (Hemeg, 2017).

Intravenously administered NPs could accumulate in the colon, lung, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and lymphatic system (Hagens et al., 2007), and inhalation might cause cytotoxicity in the lung (Leucuta, 2013). The generated free radical-mediated oxidative stress by CuO NP could interact with cell components and induce hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity (De Jong and Borm, 2008; Lei et al., 2008; Baptista et al., 2018). Though several in vivo studies have reported no apparent life-threatening toxicity related to NPs (Pfurtscheller et al., 2014; Sengupta et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2015; Zazo et al., 2016), chronic toxicity, such as nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, or pulmonary toxicity, can result from the accumulation of metallic NPs in these tissues (Duncan and Gaspar, 2011; Arvizo et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015; Zazo et al., 2016).

However, the evaluation of toxicity at the cellular and systemic levels remains important for clinical translation, and several parameters, such as the administration route for a desired therapeutic effect (Khan et al., 2016) and the nature and extent of the interactions between NPs and cells, tissues, and organs, should be considered (Sandhiya et al., 2009). Detailed in vivo and clinical studies assessing the toxicity of NPs are highly desirable before the routine application of NPs in combating difficult-to-treat infections due to MDROs.

NPs have multifunctional mechanisms to attack bacteria that are different from those of the currently available antibiotics (Figure 1), and the combination of NPs and clinically available antibiotics allows for recovery of antimicrobial efficacy (Zhao and Jiang, 2013; Zazo et al., 2016). Microbial cells need to acquire multiple mutations to develop resistance toward NPs (Singh et al., 2018). Furthermore, the synthesis of NPs that bind with proteins, polysaccharides, or small bioactive compounds would further enhance their antimicrobial activity toward MDROs (Singh et al., 2018). Resistance to NPs is always a clinical concern (Zhao and Jiang, 2013). Though rare, bacteria resistant to Ag, Au, or Cu NPs have been reported even after exposure to one dose of NPs (Zhao and Jiang, 2013; Finley et al., 2015; Zazo et al., 2016). The resistance might be related to changes in the permeability of the outer membrane and high expression of efflux pumps (Zhao and Jiang, 2013; Finley et al., 2015).

Another example of resistance to NPs is that after exposure to Cu++ and Cu-doped TiO2 NPs, reduced antimicrobial activity of TiO2 NPs to Shewanella oneidensis was noted. This effect is likely to be associated with decreased uptake and/or increased efflux of Cu++ and Cu-doped TiO2 NPs (Wu et al., 2010; Hajipour et al., 2012). Reduced toxic effects of both TiO2 and Al2O3 NPs to Cupriavidus metallidurans were possibly due to less uptake of plasma membrane or cell wall or increased efflux of NPs (Pelgrift and Friedman, 2013).

The increasing clinical application of Ag NPs still raises the concern of bacterial resistance to Ag NPs (Barros et al., 2018). Resistance to Ag NPs attributed to sil genes has been reported in clinical K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae isolates from burn cases (Finley et al., 2015). Genetic changes in bacteria may result in the rapid evolution of resistance to Ag NPs (Graves et al., 2015), and Al2O3 NPs could trigger increased expression of conjugation-promoting genes and promote the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (Hemeg, 2017). The phenotypic change in the production of flagellin in E. coli isolates resistant to Ag NPs was found to readily induce NP aggregation and attenuate the antimicrobial activity of Ag NPs (Finley et al., 2015; Panacek et al., 2018).

NPs have the potential to treat bacterial infections (Table 3), but several challenges remain for their successful translation to the clinic, including further assessment of the interactions of NPs with cells, tissues, and organs; optimal dose; recognition of appropriate administration routes; and toxicity following acute and long-term exposure (Sandhiya et al., 2009; Huh and Kwon, 2011; Baptista et al., 2018).

The unique physical structure of NPs offers distinctive advantages over conventional antibiotics in terms of antibiotic resistance (Zazo et al., 2016). The current state of NPs exhibits a strong potential to topically treat skin infections in the near future (Zazo et al., 2016). Efforts have been made to apply NPs on the contact surfaces of medical devices, fibers, and textiles (Zazo et al., 2016). However, systemic administration of NPs still requires multiple aspects to be addressed (Zazo et al., 2016; Zaidi et al., 2017).

Formulation of proper guidelines for the production and scaled-up manufacturing of these nanomaterials, the characterization of the physicochemical properties and their effect on biocompatibility, standardization of nanotoxicological assays, and protocols to compare data originating from in vitro and in vivo studies are urgent for clinical translation (Duncan and Gaspar, 2011; Beyth et al., 2015; Rai et al., 2016; Zazo et al., 2016). Further preclinical studies have to consider the therapeutic efficacy parameters in clinical trials and the safety of NP systems (Zazo et al., 2016). Finally, the economic impact of clinical translation of these NPs must be addressed with regard to their therapeutic efficacy (Duncan and Gaspar, 2011; Zazo et al., 2016).

Given their therapeutic potential, it is essential to determine the mechanisms by which NP complexes inhibit or kill bacteria. However, there is limited information about the metabolism, clearance, and toxicity of NPs; the nature of optimal targets for certain infections; and the optimum dose for therapeutic activity at the pathogen target sites. Specific combinations of NPs and antibiotics can prevent the emergence of resistance or drive resistant bacteria back toward drug sensitivity, but translation into the clinic requires an in-depth perception of the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of NPs.

NL wrote the manuscript, and WK and PH revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the grants from National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan (NCKUH-10802042) for publication fee.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ansari, M. A., Khan, H. M., Khan, A. A., Cameotra, S. S., Saquib, Q., Musarrat, J. (2014). Interaction of Al(2)O(3) nanoparticles with Escherichia coli and their cell envelope biomolecules. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 772–783. doi:10.1111/jam.12423

Arvizo, R. R., Bhattacharyya, S., Kudgus, R. A., Giri, K., Bhattacharya, R., Mukherjee, P. (2012). Intrinsic therapeutic applications of noble metal nanoparticles: past, present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2943–2970. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15355f

Baptista, P. V., Mccusker, M. P., Carvalho, A., Ferreira, D. A., Mohan, N. M., Martins, M., et al. (2018). Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria—”a battle of the titans”. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1441. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01441

Baranwal, A., Srivastava, A., Kumar, P., Bajpai, V. K., Maurya, P. K., Chandra, P. (2018). Prospects of nanostructure materials and their composites as antimicrobial agents. Front. Microbiol. 9, 422. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00422

Barros, C. H. N., Fulaz, S., Stanisic, D., Tasic, L. (2018). Biogenic nanosilver against multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDRB). Antibiotics (Basel) 7. doi:10.3390/antibiotics7030069

Beyth, N., Houri-Haddad, Y., Domb, A., Khan, W., Hazan, R. (2015). Alternative antimicrobial approach: nano-antimicrobial materials. Evid. Based. Complement Alternat. Med. 2015, 246012. doi:10.1155/2015/246012

Bondarenko, O., Juganson, K., Ivask, A., Kasemets, K., Mortimer, M., Kahru, A. (2013). Toxicity of Ag, CuO and ZnO nanoparticles to selected environmentally relevant test organisms and mammalian cells in vitro: a critical review. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 1181–1200. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1079-4

Boucher, H. W., Talbot, G. H., Bradley, J. S., Edwards, J. E., Gilbert, D., Rice, L. B., et al. (2009). Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, 1–12. doi:10.1086/595011

Burdusel, A. C., Gherasim, O., Grumezescu, A. M., Mogoanta, L., Ficai, A., Andronescu, E. (2018). Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: an up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials (Basel) 8. doi:10.3390/nano8090681

Cavassin, E. D., De Figueiredo, L. F., Otoch, J. P., Seckler, M. M., De Oliveira, R. A., Franco, F. F., et al. (2015). Comparison of methods to detect the in vitro activity of silver nanoparticles (AgNP) against multidrug resistant bacteria. J. Nanobiotechnology 13, 64. doi:10.1186/s12951-015-0120-6

Chatterjee, A. K., Chakraborty, R., Basu, T. (2014). Mechanism of antibacterial activity of copper nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 25, 135101. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/25/13/135101

Chen, C. W., Hsu, C. Y., Lai, S. M., Syu, W. J., Wang, T. Y., Lai, P. S. (2014). Metal nanobullets for multidrug resistant bacteria and biofilms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 78, 88–104. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2014.08.004

Cheng, G., Dai, M., Ahmed, S., Hao, H., Wang, X., Yuan, Z. (2016). Antimicrobial drugs in fighting against antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 7, 470. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00470

Dakal, T. C., Kumar, A., Majumdar, R. S., Yadav, V. (2016). Mechanistic basis of antimicrobial actions of silver nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1831. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01831

De Jong, W. H., Borm, P. J. (2008). Drug delivery and nanoparticles: applications and hazards. Int. J. Nanomed. 3, 133–149. doi:10.2147/IJN.S596

Ding, L., Liu, Z., Aggrey, M. O., Li, C., Chen, J., Tong, L. (2015). Nanotoxicity: the toxicity research progress of metal and metal-containing nanoparticles. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 15, 529–542. doi: 10.2174/138955751507150424104334

Dizaj, S. M., Lotfipour, F., Barzegar-Jalali, M., Zarrintan, M. H., Adibkia, K. (2014). Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 44, 278–284. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.031

Dos Santos, C. A., Seckler, M. M., Ingle, A. P., Gupta, I., Galdiero, S., Galdiero, M., et al. (2014). Silver nanoparticles: therapeutical uses, toxicity, and safety issues. J. Pharm. Sci. 103, 1931–1944. doi:10.1002/jps.24001

Duncan, R., Gaspar, R. (2011). Nanomedicine(s) under the microscope. Mol. Pharm. 8, 2101–2141. doi:10.1021/mp200394t

Duran, N., Duran, M., De Jesus, M. B., Seabra, A. B., Favaro, W. J., Nakazato, G. (2016). Silver nanoparticles: a new view on mechanistic aspects on antimicrobial activity. Nanomedicine 12, 789–799. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.016

Fakhri, A., Tahami, S., Naji, M. (2017). Synthesis and characterization of core–shell bimetallic nanoparticles for synergistic antimicrobial effect studies in combination with doxycycline on burn specific pathogens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 169, 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.02.014

Finley, P. J., Norton, R., Austin, C., Mitchell, A., Zank, S., Durham, P. (2015). Unprecedented silver resistance in clinically isolated Enterobacteriaceae: major implications for burn and wound management. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 4734–4741. doi:10.1128/AAC.00026-15

Fischbach, M. A. (2011). Combination therapies for combating antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 519–523. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.08.003

Graves, J. L., Jr., Tajkarimi, M., Cunningham, Q., Campbell, A., Nonga, H., Harrison, S. H., et al. (2015). Rapid evolution of silver nanoparticle resistance in Escherichia coli. Front. Genet. 6, 42. doi:10.3389/fgene.2015.00042

Gupta, A., Saleh, N. M., Das, R., Landis, R. F., Bigdeli, A., Motamedchaboki, K., et al. (2017). Synergistic antimicrobial therapy using nanoparticles and antibiotics for the treatment of multidrug-resistant bacterial infection. Nano. Futures 1, 015004. doi:10.1088/2399-1984/aa69fb

Hagens, W. I., Oomen, A. G., De Jong, W. H., Cassee, F. R., Sips, A. J. (2007). What do we (need to) know about the kinetic properties of nanoparticles in the body? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 49, 217–229. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.07.006

Hajipour, M. J., Fromm, K. M., Ashkarran, A. A., Jimenez De Aberasturi, D., De Larramendi, I. R., Rojo, T., et al. (2012). Antibacterial properties of nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 30, 499–511. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.06.004

Hemeg, H. A. (2017). Nanomaterials for alternative antibacterial therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 8211–8225. doi:10.2147/IJN.S132163

Hoshyar, N., Gray, S., Han, H., Bao, G. (2016). The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine (Lond) 11, 673–692. doi:10.2217/nnm.16.5

Hua, S., de Matos, M. B. C., Metselaar, J. M., Storm, G. (2018). Current trends and challenges in the clinical translation of nanoparticulate nanomedicines: pathways for translational development and commercialization. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 790. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00790

Huh, A. J., Kwon, Y. J. (2011). “Nanoantibiotics”: a new paradigm for treating infectious diseases using nanomaterials in the antibiotics resistant era. J. Control. Release 156, 128–145. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.002

Ismail, B., Shafei, M. N., Harun, A., Ali, S., Omar, M., Deris, Z. Z. (2018). Predictors of polymyxin B treatment failure in Gram-negative healthcare-associated infections among critically ill patients. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 51, 763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.03.007

Ivask, A., Juganson, K., Bondarenko, O., Mortimer, M., Aruoja, V., Kasemets, K., et al. (2014). Mechanisms of toxic action of Ag, ZnO and CuO nanoparticles to selected ecotoxicological test organisms and mammalian cells in vitro: a comparative review. Nanotoxicology 8 Suppl 1, 57–71. doi:10.3109/17435390.2013.855831

Kandi, V., Kandi, S. (2015). Antimicrobial properties of nanomolecules: potential candidates as antibiotics in the era of multi-drug resistance. Epidemiol. Health 37, e2015020. doi:10.4178/epih/e2015020

Khan, S. T., Musarrat, J., Al-Khedhairy, A. A. (2016). Countering drug resistance, infectious diseases, and sepsis using metal and metal oxides nanoparticles: current status. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 146, 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.05.046

Kuo, A. J., Shu, J. C., Liu, T. P., Lu, J. J., Lee, M. H., Wu, T. S., et al. (2018). Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium at a university hospital in Taiwan, 2002–2015: fluctuation of genetic populations and emergence of a new structure type of the Tn1546-like element. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 51, 821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.08.008

Lei, R., Wu, C., Yang, B., Ma, H., Shi, C., Wang, Q., et al. (2008). Integrated metabolomic analysis of the nano-sized copper particle-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in rats: a rapid in vivo screening method for nanotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 232, 292–301. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.06.026

Lesniak, A., Salvati, A., Santos-Martinez, M. J., Radomski, M. W., Dawson, K. A., Aberg, C. (2013). Nanoparticle adhesion to the cell membrane and its effect on nanoparticle uptake efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1438–1444. doi:10.1021/ja309812z

Leucuta, S. E. (2013). Systemic and biophase bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of nanoparticulate drug delivery systems. Curr. Drug Deliv. 10, 208–240. doi:10.2174/1567201811310020007

Lin, Z., Monteiro-Riviere, N. A., Riviere, J. E. (2015). Pharmacokinetics of metallic nanoparticles. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 7, 189–217. doi:10.1002/wnan.1304

Lu, Z., Rong, K., Li, J., Yang, H., Chen, R. (2013). Size-dependent antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles against oral anaerobic pathogenic bacteria. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 24, 1465–1471. doi:10.1007/s10856-013-4894-5

Mulvey, M. R., Simor, A. E. (2009). Antimicrobial resistance in hospitals: how concerned should we be? CMAJ 180, 408–415. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080239

Munger, M. A., Radwanski, P., Hadlock, G. C., Stoddard, G., Shaaban, A., Falconer, J., et al. (2014). In vivo human time-exposure study of orally dosed commercial silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 10, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2013.06.010

Muzammil, S., Hayat, S., Fakhar, E.a.M., Aslam, B., Siddique, M. H., Nisar, M. A., et al. (2018). Nanoantibiotics: future nanotechnologies to combat antibiotic resistance. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed) 10, 352–374. doi:10.2741/e827

Naqvi, S. Z., Kiran, U., Ali, M. I., Jamal, A., Hameed, A., Ahmed, S., et al. (2013). Combined efficacy of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles and different antibiotics against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Int. J. Nanomed. 8, 3187–3195. doi:10.2147/IJN.S49284

Natan, M., Banin, E. (2017). From nano to micro: using nanotechnology to combat microorganisms and their multidrug resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 302–322. doi:10.1093/femsre/fux003

Panacek, A., Kvitek, L., Smekalova, M., Vecerova, R., Kolar, M., Roderova, M., et al. (2018). Bacterial resistance to silver nanoparticles and how to overcome it. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 65–71. doi:10.1038/s41565-017-0013-y

Panacek, A., Smekalova, M., Kilianova, M., Prucek, R., Bogdanova, K., Vecerova, R., et al. (2015). Strong and nonspecific synergistic antibacterial efficiency of antibiotics combined with silver nanoparticles at very low concentrations showing no cytotoxic effect. Molecules 21, E26. doi:10.3390/molecules21010026

Pfurtscheller, K., Petnehazy, T., Goessler, W., Bubalo, V., Kamolz, L. P., Trop, M. (2014). Transdermal uptake and organ distribution of silver from two different wound dressings in rats after a burn trauma. Wound Repair Regen. 22, 654–659. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12209

Peleg, A. Y., Hooper, D. C. (2010). Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1804–1813. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0904124

Pelgrift, R. Y., Friedman, A. J. (2013). Nanotechnology as a therapeutic tool to combat microbial resistance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65, 1803–1815. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2013.07.011

Rai, M., Ingle, A. P., Gaikwad, S., Gupta, I., Gade, A., and Silverio Da Silva, S. (2016). Nanotechnology based anti-infectives to fight microbial intrusions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 527–542. doi:10.1111/jam.13010

Rai, M. K., Deshmukh, S. D., Ingle, A. P., Gade, A. K. (2012). Silver nanoparticles: the powerful nanoweapon against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 112, 841–852. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05253.x

Ren, G., Hu, D., Cheng, E. W., Vargas-Reus, M. A., Reip, P., Allaker, R. P. (2009). Characterisation of copper oxide nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 33, 587–590. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.12.004

Rudramurthy, G. R., Swamy, M. K., Sinniah, U. R., Ghasemzadeh, A. (2016). Nanoparticles: alternatives against drug-resistant pathogenic microbes. Molecules 21. doi:10.3390/molecules21070836

Saha, B., Bhattacharya, J., Mukherjee, A., Ghosh, A., Santra, C., Dasgupta, A. K., et al. (2007). In vitro structural and functional evaluation of gold nanoparticles conjugated antibiotics. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2, 614–622. doi:10.1007/s11671-007-9104-2

Sandhiya, S., Dkhar, S. A., Surendiran, A. (2009). Emerging trends of nanomedicine—an overview. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 23, 263–269. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00692.x

Scandorieiro, S., De Camargo, L. C., Lancheros, C. A., Yamada-Ogatta, S. F., Nakamura, C. V., De Oliveira, A. G., et al. (2016). Synergistic and additive effect of oregano essential oil and biological silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacterial strains. Front. Microbiol. 7, 760. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00760

Schrand, A. M., Rahman, M. F., Hussain, S. M., Schlager, J. J., Smith, D. A., Syed, A. F. (2010). Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2, 544–568. doi: 10.1002/wnan.103.

Seil, J. T., Webster, T. J. (2012). Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 7, 2767–2781. doi:10.2147/IJN.S24805

Sengupta, J., Ghosh, S., Datta, P., Gomes, A., Gomes, A. (2014). Physiologically important metal nanoparticles and their toxicity. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 990–1006. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9078

Singh, P., Garg, A., Pandit, S., Mokkapati, V., Mijakovic, I. (2018). Antimicrobial effects of biogenic nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel) 8. doi:10.3390/nano8121009

Singh, R., Smitha, M. S., Singh, S. P. (2014). The role of nanotechnology in combating multi-drug resistant bacteria. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 4745–4756. doi:10.1166/jnn.2014.9527

Slavin, Y. N., Asnis, J., Hafeli, U. O., Bach, H. (2017). Metal nanoparticles: understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnology 15, 65. doi:10.1186/s12951-017-0308-z

Stewart, P. S. (2002). Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292, 107–113. doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00196

Ting, S. W., Lee, C. H., Liu, J. W. (2018). Risk factors and outcomes for the acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacillus bacteremia: a retrospective propensity-matched case control study. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 51, 621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.022

Tsao, L. H., Hsin, C. Y., Liu, H. Y., Chuang, H. C., Chen, L. Y., Lee, Y. J. (2018). Risk factors for healthcare-associated infection caused by carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 51, 359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.015

Vandebriel, R. J., De Jong, W. H. (2012). A review of mammalian toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 5, 61–71. doi:10.2147/NSA.S23932

Vlachou, E., Chipp, E., Shale, E., Wilson, Y. T., Papini, R., Moiemen, N. S. (2007). The safety of nanocrystalline silver dressings on burns: a study of systemic silver absorption. Burns 33, 979–985. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2007.07.014

Wang, L., Hu, C., Shao, L. (2017). The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 1227–1249. doi:10.2147/IJN.S121956

Wei, L., Lu, J., Xu, H., Patel, A., Chen, Z. S., Chen, G. (2015). Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, properties, and therapeutic applications. Drug Discov. Today 20, 595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.11.014

Wu, B., Huang, R., Sahu, M., Feng, X., Biswas, P., Tang, Y. J. (2010). Bacterial responses to Cu-doped TiO(2) nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 1755–1758. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.11.004

Zaidi, S., Misba, L., Khan, A. U. (2017). Nano-therapeutics: a revolution in infection control in post antibiotic era. Nanomedicine 13, 2281–2301. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2017.06.015

Zazo, H., Colino, C. I., Lanao, J. M. (2016). Current applications of nanoparticles in infectious diseases. J. Control. Release 224, 86–102. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.008

Zhang, L., Pornpattananangku, D., Hu, C. M., Huang, C. M. (2010). Development of nanoparticles for antimicrobial drug delivery. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 585–594. doi:10.2174/092986710790416290

Keywords: nanoparticle, antimicrobial resistance, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, toxicity

Citation: Lee N-Y, Ko W-C and Hsueh P-R (2019) Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Organisms. Front. Pharmacol. 10:1153. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01153

Received: 01 February 2019; Accepted: 09 September 2019;

Published: 04 October 2019.

Edited by:

Sourav Bhattacharjee, University College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Amit P. Bhavsar, University of Alberta, CanadaCopyright © 2019 Lee, Ko and Hsueh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wen-Chien Ko, d2luc3RvbjM0MTVAZ21haWwuY29t; Po-Ren Hsueh, aHNwb3JlbkBudHUuZWR1LnR3

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.