- 1Public Health Institute, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 2Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 3Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 4Department of Social Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 5Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 6Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 7Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovenia

- 8Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 9Department of pharmacology and toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq

- 10Liverpool Health Economics Centre, Liverpool University, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 11Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Karolinska Institute, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden

- 12School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kota Bharu, Malaysia

Introduction: There are increasing concerns world-wide with growing rates of antibiotic resistance necessitating urgent action. There have been a number of initiatives in the Republic of Srpska in recent years to address this and improve rational antibiotic prescribing and dispensing despite limited resources to fund multiple initiatives.

Objective: Analyse antibiotic utilization patterns in the Republic of Srpska following these multiple initiatives as a basis for developing future programmes in the Republic if needed.

Methods: Observational retrospective study of total outpatient antibiotic utilization from 2010 to 2015, based on data obtained from the Public Health Institute, alongside documentation of ongoing initiatives to influence utilization. The quality of antibiotic utilization principally assessed according to ESAC, ECDC, and WHO quality indicators and DU 90% (the drug utilization 90%) profile as well as vs. neighboring countries.

Results: Following multiple initiatives, antibiotic utilization remained relatively stable in the Republic at 15.6 to 18.4 DIDs, with a decreasing trend in recent years, with rates comparable or lower than neighboring countries. Amoxicillin and the penicillins accounted for 29–40 and 50% of total utilization, respectively. Overall, limited utilization of co-amoxiclav (7–11%), cephalosporins, macrolides, and quinolones, as well as low use of third and fourth generation cephalosporins vs. first and second cephalosporins. However, increasing utilization of co-amoxiclav and azithromycin, as well as higher rates of quinolone utilization compared to some countries, was seen.

Conclusions: Multiple interventions in the Republic of Srpska in recent years have resulted in one of the lowest utilization of antibiotics when compared with similar countries, acting as an exemplar to others. However, there are some concerns with current utilization of co-amoxiclav and azithromycin which are being addressed. This will be the subject of future research activities.

Introduction

The discovery of antibiotics is one of the greatest discoveries of modern medicine. However, since their discovery, it is acknowledged that bacteria have the ability to become resistant to antibiotics if they are not used rationally (Rezal et al., 2015; Godman et al., 2017). Excessive and non-rational use of antibiotics have resulted in increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) worldwide, with ongoing initiatives to address this including addressing issues of governance (WHO, 2011, 2015; Collignon et al., 2015; Shallcross et al., 2015; Jinks et al., 2016). This is essential given the low number of new antibiotics in development; although there are activities to try and improve the situation (O'Neill, 2015; Tacconelli et al., 2018). Irrational use of antibiotics includes the prescribing and dispensing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), which are the principal infections seen in ambulatory care and are predominantly viral in origin (Llor and Bjerrum, 2014; Dyar et al., 2016; Aabenhus et al., 2017). Inappropriate prescribing, as well as dispensing without a prescription, are enhanced by patient pressure, sub-optimal knowledge about antibiotics and viral infections among key stakeholder groups and fears among physicians and pharmacists that if they do not prescribe or dispense an antibiotic patients will go elsewhere (Jorgji et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014; Hassali et al., 2015; Bai et al., 2016; Eslami et al., 2016; Kibuule et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2017).

The costs of AMR in Europe were estimated at €1.5 billion in 2007, but now rising to €9 billion per year or higher (Oxford and Kozlov, 2013; Gandra et al., 2014). The lack of new antibiotics alongside increasing AMR rates has resulted in increasing morbidity, mortality and costs to healthcare systems (Aminov, 2010; Gandra et al., 2014; O'Neill, 2015). As a result, AMR is now seen as one of the biggest public health challenges (ECDC, 2016), with deaths due to resistant strains envisaged to reach up to 444 million patients by 2050 if AMR is not addressed (Taylor et al., 2014; Fitchett and Atun, 2016). This is preventable with the spread of resistant strains directly correlated with increasing and irrational use of antibiotics (Costelloe et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2014; Llor and Bjerrum, 2014). Consequently, raising awareness and knowledge about AMR and rational antibiotic use among all key stakeholder groups should result in a reduction in AMR rates (Huttner et al., 2010; Md Rezal et al., 2015; Rezal et al., 2015; Godman et al., 2017; WHO, 2018). We are already seeing multiple activities across Europe including former Soviet Union Republics to tackle concerns with current antibiotic use and this will continue (Huttner et al., 2010; Fürst et al., 2015; Abilova et al., 2018; ECDC, 2018).

The Republic of Srpska is one of the two constituent entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with an estimated population of ~1.4 million. The Republic has implemented a range of laws and other activities over the years to regulate health care activities, which includes enhancing the appropriate use of medicines through initiatives including introducing good clinical practice guidelines (MoHSW, 1999, 2008, 2009, 2010; PABH, 2008; Petrusic and Jakovljevic, 2015). Activities have also been ongoing in other Balkan countries; however, there are concerns with the practice of evidence based medicine, the cost consciousness of physicians even after cost containment policies as well as the principles of resource allocation among physicians, although this is changing (Jakovljevic et al., 2016a,b). There are also concerns with the level of co-payments among patients in the Balkan countries especially with high cost medicines; although this has not prevented pharmaceutical markets growing among the Balkan countries as seen in Bulgaria, Croatia, the Republic of Srpska and Serbia in recent years, including medicines for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer and depression (Putrik et al., 2014; Jakovljevic et al., 2015; Petrusic and Jakovljevic, 2015; Jakovljevic and Souliotis, 2016; Kostić et al., 2017; Pejcic and Jakovljevic, 2017).

Policies and programmes to improve the health of patients with limited resources in the Republic of Srpska include improving the availability and affordability of medicines, improving antibiotic prescribing and dispensing, and raising awareness on excessive antibiotic utilization and resistance. A summary of these initiatives are contained in Boxes 1, 2. The various activities have increased prescribing efficiency as well as enhanced prescribing in accordance with standard treatment guidelines, positively impacting on for instance the rate of polypharmacy in practice (Markovic-Pekovic et al., 2012; Marković-Peković et al., 2016).

Box 1. Legal framework for regulation of health care and rational medicine use in the Republic of Srpska.

• Laws, rulebooks, programs, and policies for regulating the health care and rational use of medicines, including antibiotics, adopted by Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) of the Republic of Srpska (MoHSW, 1999, 2008, 2009, 2010; PABH, 2008).

• Antibiotics can only be dispensed on prescription by pharmacist. There are considerable fines if this is abused (MoHSW 2008; PABH, 2008).

• The Republic of Srpska Inspectorate is the responsible institution for supervising the implementation of this legislation.

• The MoHSW established the National Committee for AMR Control as a national expert body (2015) responsible for monitoring and controlling of AMR and proposing measures to improve rational antibiotic prescribing and utilization.

• On the proposal of the National Committee, the MoHSW adopted the national Program to reduce AMR resistance in the Republic of Srpska from 2016 to 2020, harmonized with the WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance (WHO, 2001) and the Council of Europe Recommendation's on prudent use of antimicrobial agents in human medicine (EC, 2002). The aim of this program is to establish and implement high-quality and effective health care for the population ensuring good control of AMR with an emphasis on rational antibiotic use. The stated objectives are to be reached through improving the intersectoral control on AMR and antibiotic use in healthcare as well as among veterinary institutions, seeking to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by multiresistant strains of bacteria, improving education among health workers and associates in the field of AMR, raising awareness on AMR and rational antibiotic use and, also, through participation of representatives from the Republic of Srpska in international networks and research in the field of AMR.

Box 2. Activities to improve rational antibiotic use in the Republic of Srpska.

Activities to enhance rational prescribing

• The set of Clinical Guidelines (CG) with diagnostic and therapeutic principles have been developed for Primary Health Care physicians. These include guidelines for upper and lower acute respiratory infections in children (acute otitis media, tonsillopharyngitis, community acquired pneumonia), urinary tract infections in children, as well as urinary tract infections in adults (2004).

• The list of antibiotics funded by the Health Insurance Fund of the Republic of Srpska (HIF) are in accordance with the CG recommendations.

• HIF adopted a positive list of medicines with reference prices comprised of List A and List B. List A is a basic list of medicines for which HIF covers 90 or 100% of the reference price of the medicine depending on the category of the insured person. List B is a supplementary list, which includes more expensive medicines, for which HIF covers 50% of the costs for all insured patients. For medicines not included in the positive list, the patient must pay 100% of the price. In addition, if the price of drug is higher than the reference price adopted by HIF, the patient has to pay the price difference.

• The antibiotics included in List A are: doxycycline, amoxicillin, phenoxymethylpenicillin, benzathine-phenoxymethylpenicillin, cefalexin, sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim, and erythromycin. Norfloxacin is included in List B.

Activities to enhance rational dispensing

• There is permanent education of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians on the appropriate management of infectious diseases to address concerns with knowledge of infectious diseases, especially viral infectious diseases, which has been a concern in other countries (Eslami et al., 2016; Saleem et al., 2016; Belkina et al., 2017; Hoxha et al., 2018).

• The Pharmaceutical Association of the Republic of Srpska launched the ‘The Guideline for counseling patients in the pharmacy’ as a tool to assist pharmacy personnel to make decisions whether they can successfully treat patients with non-pharmacological measures and/or with OTC medicines, or whether to refer them to a family practitioner, in view of concerns with self-medication with antibiotics in the Republic (Marković-Peković and Grubisa, 2012; Damjanović et al., 2013; Marković-Peković et al., 2017).

Activities of professional associations and key stakeholder groups

• Regular professional meetings, conferences and symposia in order to upgrade the knowledge, habits and attitudes of health professionals (doctors and pharmacists).

• Publishing articles on AMR and rational antibiotic use in professional journals.

• Discussions concerning current AMR surveillance in the Republic of Srpska among key stakeholder groups and agreement of specific activities to improve AMR reporting and monitoring.

• The MoHSW and the Public Health Institute (PHI) marking European Antibiotic Awareness Day and World Antibiotic Awareness Week in November each year starting from 2013 with support of European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Activities to enhance public awareness on AMR and rational antibiotic use

• Campaigns are organized to raise awareness about AMR and rational antibiotic use among the general public, patient associations and health professionals.

• Promotional materials (including flyers, infographics, fact sheets, posters, and social media), recommended by ECDC, are provided to patients and health professionals.

Consequently, the aim of this study was to analyse total antibiotic utilization in the Republic of Srpska in recent years and to assess the influence of these various initiatives to improve antibiotic prescribing and dispensing in the Republic. Subsequently, compare the findings with those of other European and neighboring countries to review potential additional measures that could be introduced in the Republic of Srpska if needed to further improve the rational use of antibiotics. As a result, seek to reduce future AMR rates.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study on outpatient antibiotic utilization in the Republic of Srpska from 2010 to 2015, based on drug utilization data obtained from the Public Health Institute (PHI). Data collection was based on quantitative and structural medicinal reports that pharmacies in the Republic send to the PHI each year for collation (Petrusic and Jakovljevic, 2015). Consequently, includes total antibiotic utilization in the Republic and not just prescribed antibiotics.

Drug utilization analysis of the PHI data was undertaken using the ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification)/DDD (Defined Daily Dose) methodology (WHO, 2017), which is the internationally accepted methodology for measuring medicine utilization within and across populations (Godman et al., 2014; Malo et al., 2014; Versporten et al., 2014; Abilova et al., 2018). DDDs are defined as the amount of drug most commonly used in adults for the most common indication. It is a suitable measure to describe and compare drug utilization patterns between different geographical areas and health facilities. Data on outpatient antibiotic utilization are expressed in DDD/1,000 inhabitants/day (DIDs) for comparative purposes (Malo et al., 2014; Versporten et al., 2014; WHO, 2017). DU 90% (drug utilization 90%) was also used as indicator for assessing the quality of antibiotic prescribing, ranking antibiotics first by volume of DIDs and then by how many antibiotics were included in DU 90% (Markovic-Pekovic et al., 2009; Malo et al., 2014).

Antibiotic utilization and associated quality indicators were used to compare the Republic of Srpska's utilization patterns with that from other European countries, as well as former Soviet Union Republics, to place this in perspective (Adriaenssens et al., 2011a,b; Versporten et al., 2014; de Bie et al., 2016; WHO EUROPE, 2017). The quality of antibiotic prescribing was assessed using the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), and World Health Organization (WHO) Europe quality indicators (Adriaenssens et al., 2011a,b; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018). These included:

• Total utilization of antibiotics expressed as DIDs,

• Utilization of penicillins (J01C) as a % of total antibiotic use,

• Penicillins combination utilization such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav) as a percentage of total antibiotic use,

• Total utilization of cephalosporins expressed as DIDs,

• Percentage utilization of third- and fourth-generation of cephalosporins vs. all cephalosporins,

• Total utilization of J01F group (macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins) expressed as DIDs

• Utilization of short-acting macrolides, intermediate and long-acting macrolides (erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin) as a percentage of total antibiotic use,

• Utilization of quinolones (J01M) expressed in DIDs as well as percentage of fluoroquinolones (J01MA) of total antibiotic use.

A number of these indicators are due to concerns with the over use of co-amoxiclav, macrolides, third and fourth generation cephalosporins as well as fluoroquinolones (Adriaenssens et al., 2011a; Malo et al., 2014; WHO EUROPE, 2017).

Since multiple initiatives and reforms were instigated over time in the Republic of Srpska with varying intensity, coupled with the nature of reported figures, it was impossible to undertake sophisticated statistical analyses such as time series analyses. As a result, more simple statistical tests, including trend analyses, were performed to assess the level of significance, with significance seen as p < 0.05. This is similar to other health authority analyses where multiple interventions are conducted over time with no opportunity for time series analyses (Godman et al., 2010, 2014; Voncina et al., 2011; Bennie et al., 2012; Abilova et al., 2018).

No specific ethical approval was sought as only aggregated anonymized data was used for analysis, with Ministry of Health personnel involved in the study. This is similar to other studies of this nature (Godman et al., 2010, 2014; Bennie et al., 2012; Abilova et al., 2018).

Results

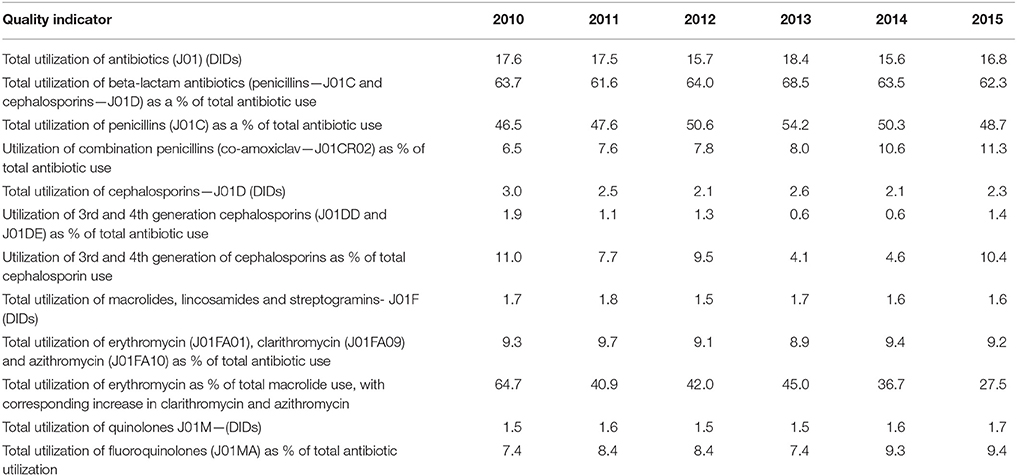

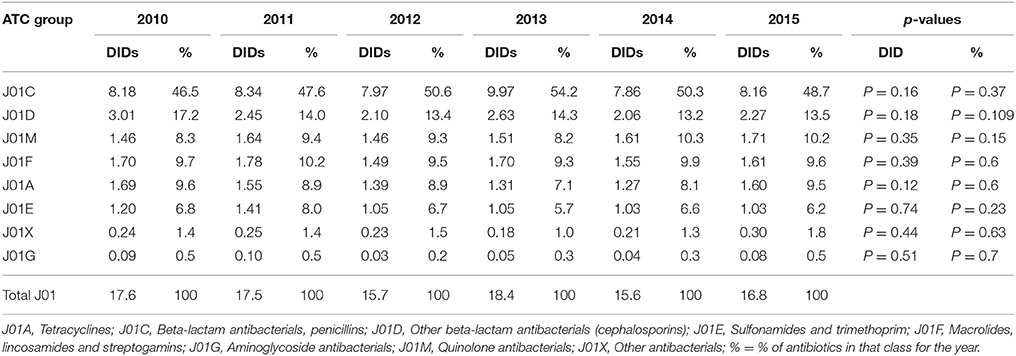

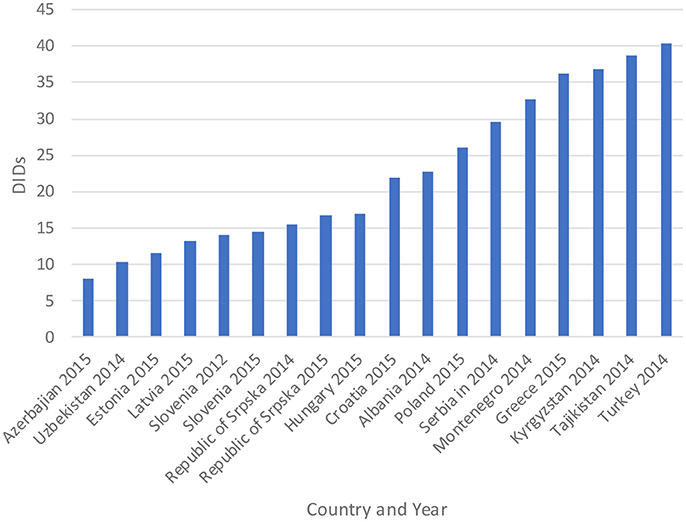

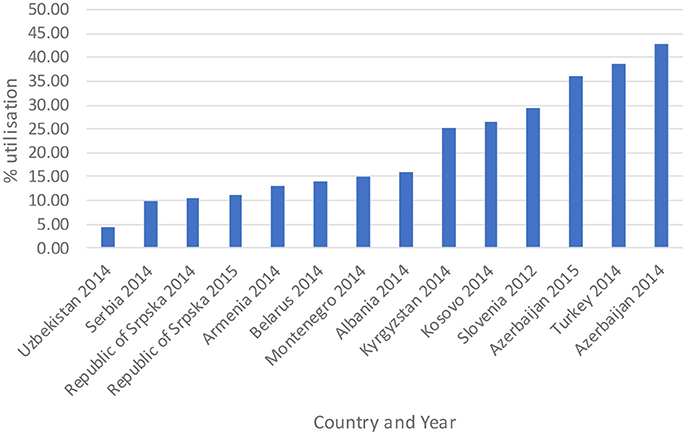

The total utilization of antibiotics for systemic use (J01 group) comprised 98% of total utilization of anti-infectives (J group). Utilization of the J01 group varied between 15.6 and 18.4 DIDs during the observed period (Tables 1, 4), lower than a number of neighboring countries (Figure 1).

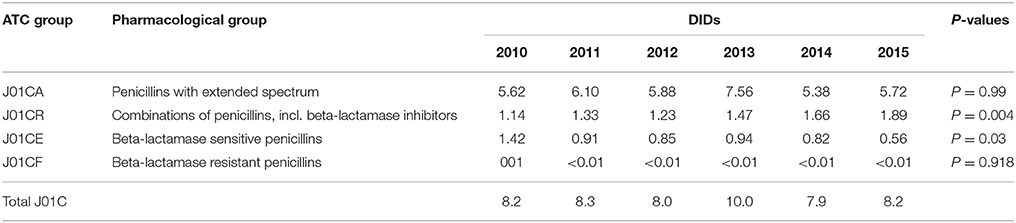

Table 1. Total utilization of antibiotics for systemic use (J01 group) expressed in DIDs and percentages from 2010 to 2015.

Figure 1. Antibiotic utilization in the Republic of Srpska in 2014 and 2015 (in DIDs) vs. neighboring countries in similar years (Taken from Fürst et al., 2015; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018).

Figure 1 compares the utilization in recent years with other neighboring countries.

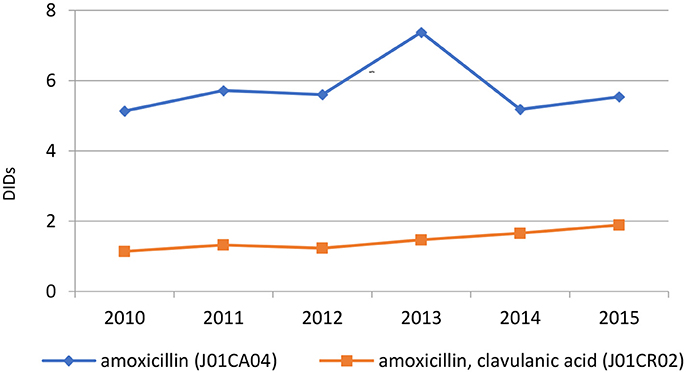

The penicillins (J01C) were the most consumed antibiotics comprising 50% of total antibiotic utilization on average, followed by other beta-lactam antibiotics (14%). The highest utilization of penicillins was observed in 2013 with 10.0 DIDs, while the lowest (7.9 DIDs) observed in 2014. The utilization of broad-spectrum penicillins (J01CA) was 6.04 DIDs on average (Table 2). Amoxicillin constituted 95% of this group (5.76 DIDs) (Figure 2), followed by ampicillin (0.28 DIDs). Co-amoxiclav (J01CR02) ranged from 1.1 to 1.9 DIDs from 2010 to 2015 (Figure 2), while beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins (J01CE) comprised 5% of total antibiotic use (Table 2), with phenoxymethylpenicillin the most prescribed antibiotic of this group.

Utilization of cephalosporins (J01D) decreased from 3.0 DIDs in 2010 to 2.3 DIDs in 2015 (Tables 1, 4). The first-generation cephalosporins (J01DB) were the most used within J01D group (67.6%), of which cefalexin was the only one used. Its utilization decreased from 2.0 DIDs in 2010 to 1.5 DIDs in 2015, which represents a reduction of 25%. Overall, utilization of the second and third generation of cephalosporins (J01DC and J01DD) also declined during this period. Regarding the second-generation cephalosporins, cefuroxime had very stable utilization ranging from 0.45 to 0.56 DIDs during the study period, while utilization of cefaclor decreased from 0.15 in 2010 to 0.05 DIDs in 2015 (67%). Overall, third generation cephalosporins constituted 7.9% of total cephalosporins, or 1.2% on average of total antibiotics (Table 4). After declining from 2010 to 2014, utilization of third generation cephalosporins subsequently increased in 2015 (Table 4). The fourth generation cephalosporins, monobactams, and carbapenems, were not used at all.

Erythromycin was the most used macrolide (0.68 DIDs) followed by azithromycin (0.57 DIDs) and clarithromycin (0.32 DIDs). Overall, macrolides constituted 9.4% of total antibiotic utilization, which is about five times lower than the penicillins. The use of the macrolides was highest in 2011 (1.78 DIDs) and then dropped thereafter to 1.55 DIDs in 2014 (Table 1).

Doxycycline was the most used tetracycline (J01A), with quinolone utilization (J01M) ranging from 1.5 DDDs in 2010 to 1.7 DIDs in 2015 (Table 1), of which 90% were fluoroquinolones. Ciprofloxacin was the most prescribed fluoroquinolone. The only sulphonamide (J01E) was a combination of sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim, which typically accounted for 7% of total antibiotic utilization (Table 1). Utilization of aminoglycoside antibiotics (J01G) and other antibiotics (J01X) was negligible (Table 1).

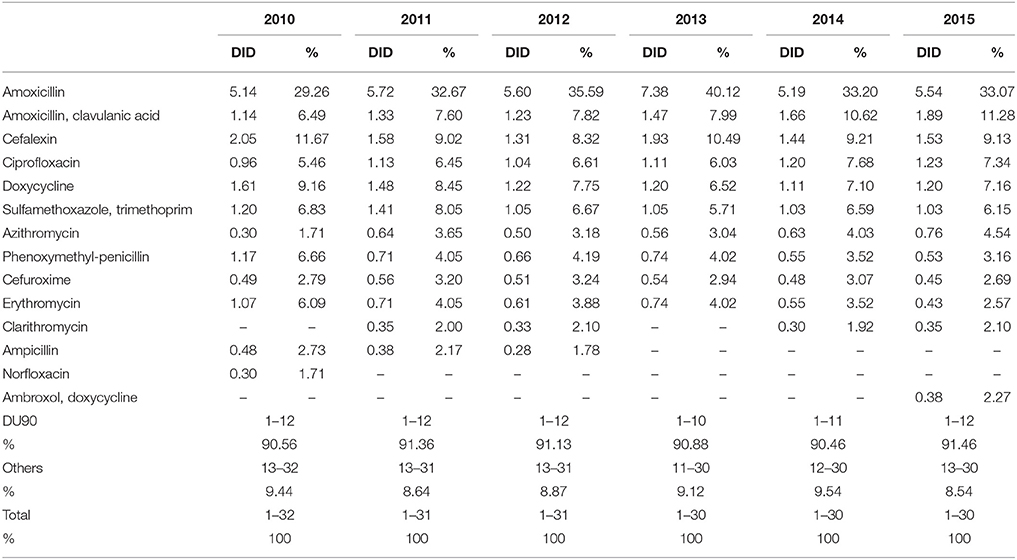

DU90% shows the number of antibiotics included in 90% of total utilization. Over the observed period, 10 antibiotics were constantly included in the DU90% profile. DU90% included 10 antibiotics in 2013, 11 in 2014, and 12 during the rest of the study years. Amoxicillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav), cephalexin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim were the most used antibiotics over the observed period (Table 3).

Table 3. Antibiotic utilization within Drug Utilization (DU90%) profile, expressed in DIDs from 2010 to 2015.

According to the quality indicators, the total utilization of beta-lactam antibiotics (penicillins and cephalosporins), macrolides and fluoroquinolones, expressed as percentage of total antibiotic use, was very stable over the observed period (Table 4). However, the use of co-amoxiclav increased from 6.5% of total antibiotic utilization in 2010 to 11.3% in 2015, which is a concern if this trend continues. At the same time, the use of erythromycin decreased for 37.2% within the macrolide group, while azithromycin rose proportionally (Tables 3, 4).

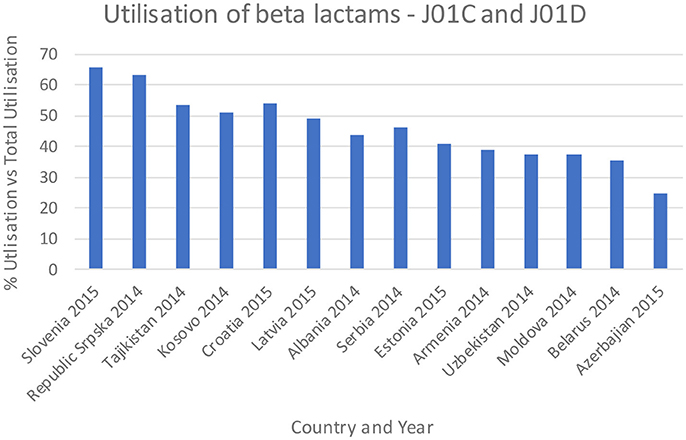

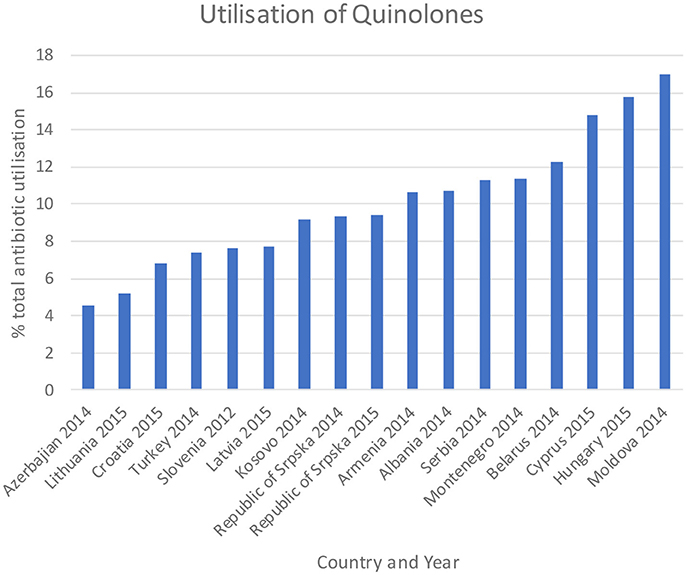

Figures 3–5 and Table 5 provide comparisons with similar and neighboring countries to the Republic of Srpska in recent years.

Figure 3. Percentage utilization of beta-lactams as a % of total antibiotic utilization across countries (taken from Fürst et al., 2015; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018).

Table 5. Utilization of third and fourth generation cephalosporins as a % of total cephalosporins (J01D) (taken from Fürst et al., 2015; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018).

Discussion

Total antibiotic utilization was relatively constant during the study period in the Republic of Srpska (Table 1), with minor fluctuations, and an overall a decline in total utilization of 5% between 2010 and 2015, with a corresponding reduction in expenditure on antibiotics (J01) in 2013 vs. 2009 (Petrusic and Jakovljevic, 2015). In addition, antibiotic utilization in the Republic was lower than a number of neighboring countries and former Soviet Union Republics in recent years (Figure 1). This is in direct contrast with total worldwide antibiotic utilization, which rose by 36% during the past decade (Laxminarayan et al., 2016). There appears to be several reasons for this in the Republic of Srpska. Firstly, health care in the Republic is well-regulated by a number of policies, strategies, guidelines, and normatives (Boxes 1,2), despite limited available resources for such initiatives. The Law on health care and the Law of health insurance enables all patients to have adequate health care access in the Republic, including medicines and other types of treatment (MoHSW, 1999, 2009). Standard treatment guidelines for the most common clinical problems in ambulatory care were developed by family physician associations and adopted by Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) in 2004 in order to improve the quality and rationality of physician prescribing. Based on these guidelines, only recommended and essential antibiotics were included in the HIF positive list of medicines to emphasize rational prescribing and reduce unnecessary expenditure to help ensure cost-efficient antibiotics are available for all citizens in the Republic. This approach is similar to the situation seen in some European countries and regions with multiple initiatives to enhance the quality and efficiency of prescribing (Gustafsson et al., 2011; Bjorkhem-Bergman et al., 2013). However, we are aware that there is variable implementation of guidelines among a number of European countries in practice (Francke et al., 2008; Sermet et al., 2010; van Dijk et al., 2011; Brusamento et al., 2012; Fitzgerald et al., 2014; Baker et al., 2015). In addition, as mentioned, there are concerns with issues of evidence based medicine among physicians in the Balkan countries (Jakovljevic et al., 2016a,b); however, this appears not to be the case in the Republic of Srpska certainly with respect to antibiotic prescribing.

Secondly, a number of initiatives and activities have been implemented in the Republic in order to improve knowledge, attitudes and practices of pharmacists to reduce antibiotic self-medication and improve appropriate management of patients with URTIs (Boxes 1, 2), especially as pharmacists are often the first health professional patients see with their URTI (Marković-Peković et al., 2017). This includes the tightening of self-medication regulations, with self-medication known to appreciably increase antibiotic utilization in URTIs and similar conditions (Kalaba et al., 2011; Kibuule et al., 2016; Marković-Peković et al., 2017). This is different to Albania where self-medication is common particularly for URTIs, and there are considerable concerns with pharmacy knowledge regarding antibiotics and viruses (Jorgji et al., 2014; Hoxha et al., 2015, 2018). There are also concerns with continuing self-medication in Serbia (Kalaba et al., 2011). Education among pharmacists also reduced the extent of self-medication with antibiotics in Kenya especially for URTIs (Mukokinya et al., 2018).

These combined initiatives also appeared to result in high use of beta-lactam antibiotics and limited use of third and fourth generation cephalosporins and fluorquinolones in the Republic in recent years in accordance with agreed quality indicators (Table 4), comparable or improved prescribing vs. neighboring countries (Figures 3, 4, and Table 5). We have also seen reduced expenditure on first and second generation cephalosporins in Serbia between 2007 and 2012, although also reduced prescribing of combinations of penicillins (J01CR) and penicillins with extended spectrums (J01CA) (Jakovljevic and Souliotis, 2016). The DU90% profile (Table 3) shows that first and second generation antibiotics were mainly used, reflecting the antibiotics reimbursed by HIF and contained in current clinical guidelines (Box 2). This is similar to the situation with other medicines when prescribing is restricted and/or where there are high co-payments to rationalize pharmacotherapy (Sakshaug et al., 2007; Martikainen et al., 2010; Wettermark et al., 2010; Kalaba et al., 2012; Markovic-Pekovic et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2014). In Slovenia, prescribing restrictions for co-amoxiclav, the cephalosporins, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones, also significantly reduced their use (Fürst et al., 2015). These findings support other published studies which suggest that multiple initiatives are typically needed to positively influence prescribing (Bero et al., 1998; Barton, 2001; Francke et al., 2008; Godman et al., 2013, 2014; Moon et al., 2014).

Figure 4. Utilization of quinolones as a % of total antibiotic utilization across countries (taken from Fürst et al., 2015; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018).

Amoxicillin, which is included in the HIF positive A list, was the most utilized penicillin in the Republic of Srpska, with utilization of co-amoxiclav approximately 4 times lower than amoxicillin. The low utilization of co-amoxiclav in the Republic compares favorably with neighboring countries (Figure 5). However, there are concerns with the rise in its utilization in recent years (Figure 2 and Tables 2, 4). This is due to concerns with increasing side-effects and resistance leading to co-amoxiclav now being recommended as a second line antibiotic after amoxicillin in a number of guidelines (Andrade and Tulkens, 2011; Desrosiers et al., 2011; NHS Scotland, 2014; GCG prescribing, 2017; ECDC, 2018). There are also concerns with currently limited prescribing of phenoxymethyl penicillin in the Republic (Table 3) as it is likely that a high proportion of infections seen in ambulatory care are likely to be URTIs (Llor and Bjerrum, 2014; Rezal et al., 2015; Dyar et al., 2016). These will be areas to address if these trends (Figure 2) continue.

Figure 5. Percentage combination penicillins (co-amoxiclav J01CR02) as a % of total antibiotic utilization (taken from Fürst et al., 2015; WHO EUROPE, 2017; ECDC, 2018).

Encouragingly, given concerns with the development and spread of resistant strains of C. difficle (Dancer, 2001; Bätzing-Feigenbaum et al., 2016), there were low rates of cephalosporin utilization, with rates remaining relatively constant over the study period (Tables 1, 4). In addition, as mentioned, the Republic of Srpska had low utilization of third and fourth generation of cephalosporins in recent years (Table 4), comparing favorably with neighboring countries (Table 5). There was also relatively low utilization of macrolides (J01F), with rates decreasing in recent years but not reaching statistical significance (Tables 1, 4). This is similar to Serbia with expenditure on macrolides falling in recent years (Jakovljevic and Souliotis, 2016). However, the prescribing of azithromycin is increasing, with a simultaneous decrease in utilization of erythromycin (Tables 3, 4), resulting in the utilization of azithromycin exceeding erythromycin in 2014 and 2015. This is causing concern with increasing resistance rates as well as side-effects with the macrolides (Albert and Schuller, 2014; ECDC, 2018).

Concerns with the recent increased utilization of co-amoxiclav and azithromycin, as well as higher use of fluoroquinolones than some neighboring countries (Table 1), has already resulted in planned activities, with their implementation and impact being monitored. These ongoing and planned activities (Box 2) should further help with enhancing appropriate antibiotic use in the Republic of Srpska. Planned activities also include programmes to improve inter-sectoral control over antibiotic utilization, including both health and veterinary sectors, as well as improved undergraduate and postgraduate education regarding antibiotics and AMR. The development of specific indicators for monitoring antibiotic utilization is also planned, building on existing quality indicators for NCDs, as well as monitoring hospital resistance patterns. These data will be used to revise and update the clinical guidelines for rational antibiotic use in the Republic. Planned activities also include improving the information technology for monitoring of AMR and antibiotic consumption. The findings will subsequently be shown to health professionals to emphasize what has been done so far and to discuss further activities. This is similar to activities in for instance in Sweden with its monitoring of prescribing in the regions together with the development of quality indicators to improve physician prescribing practices (Godman et al., 2009; Wettermark et al., 2009; Gustafsson et al., 2011; Eriksen et al., 2017).

Alongside this, pharmacists and family physicians will be encouraged to communicate more to their patients about rational antibiotic use and AMR, building on current initiatives. This will be combined with planned activities to further raise public awareness regarding the potential harmful effects of excessive, inappropriate, and unnecessary use of antibiotics. These programmes will also be the subject of future research projects.

We believe this study clearly shows that even lower income countries such as the Republic of Srpska can appreciably improve rational medicine utilization by introducing multiple interventions and initiatives, acting as an exemplar to other European countries and wider.

We are aware of a number of limitations of this study. These include no access to prescribing data to be able to assess the quality of antibiotic prescribing against standard treatment guidelines. However, we believe our methodology, including the use of total antibiotic utilization via the PHI datasets, as well as comparisons with neighboring countries, adds robustness to our findings and conclusions.

In conclusion, without looking specifically at prescribing indications, we believe there appears to be rational antibiotic utilization in the Republic of Srpska in recent years compared to neighboring countries, with favorable use of penicillins combined with moderate or low use of co-amoxiclav, cephalosporins including third and fourth generation cephalosporins, macrolides, and quinolones. This again demonstrates that multiple interventions with key stakeholder groups can favorably improve medicine utilization patterns.

Author Contributions

LB, VM-P, MÐ, RŠ, JB, and BG: developed the concept; LB, AK, VM-P, RŠ, and BG: undertook the analysis and the first write-up of the manuscript. All authors critiqued the initial and subsequent drafts before submission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

VM-P is employed by the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in the Republic of Srpska and LB, MÐ, and JB are employed by the Public Health Institute.

The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aabenhus, R., Hansen, M. P., Saust, L. T., and Bjerrum, L. (2017). Characterisation of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory tract infections in Danish general practice: a retrospective registry based cohort study. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 27:37. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0037-7

Abilova, V., Kurdi, A., and Godman, B. (2018). Ongoing initiatives in Azerbaijan to improve the use of antibiotics; findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 16, 77–84. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1417835

Adriaenssens, N., Coenen, S., Tonkin-Crine, S., Verheij, T. J., Little, P., and Goossens, H. (2011a). European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): disease-specific quality indicators for outpatient antibiotic prescribing. BMJ Qual. Saf. 20, 764–772. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.049049

Adriaenssens, N., Coenen, S., Versporten, A., Muller, A., Vankerckhoven, V., and Goossens, H. (2011b). European surveillance of antimicrobial consumption (ESAC): quality appraisal of antibiotic use in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66(Suppl. 6), vi71–v77. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr459

Albert, R. K., and Schuller, J. L. (2014). Macrolide antibiotics and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 1173–1180. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0385CI

Aminov, R. I. (2010). A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 1:134. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134

Andrade, R. J., and Tulkens, P. M. (2011). Hepatic safety of antibiotics used in primary care. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 1431–1446. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr159

Bai, Y., Wang, S., Yin, X., Bai, J., Gong, Y., and Lu, Z. (2016). Factors associated with doctors' knowledge on antibiotic use in China. Sci. Rep. 6:23429. doi: 10.1038/srep23429

Baker, A., Chen, L. C., Elliott, R. A., and Godman, B. (2015). The impact of the ‘Better Care Better Value’ prescribing policy on the utilisation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for treating hypertension in the UK primary care setting: longitudinal quasi-experimental design. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15:367. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1013-y

Bätzing-Feigenbaum, J., Schulz, M., Schulz, M., Hering, R., and Kern, W. V. (2016). Outpatient antibiotic prescription. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 113, 454–459. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0454

Belkina, T., Duvanova, N., Karbovskaja, J., Tebbens, J. D., and Vlcek, J. (2017). Antibiotic use practices of pharmacy staff: a cross-sectional study in Saint Petersburg, the Russian Federation. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 18:11. doi: 10.1186/s40360-017-0116-y

Bell, B. G., Schellevis, F., Stobberingh, E., Goossens, H., and Pringle, M. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 14:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-13

Bennie, M., Godman, B., Bishop, I., and Campbell, S. (2012). Multiple initiatives continue to enhance the prescribing efficiency for the proton pump inhibitors and statins in Scotland. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 12, 125–130. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.98

Bero, L. A., Grilli, R., Grimshaw, J. M., Harvey, E., Oxman, A. D., and Thomson, M. A. (1998). Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The cochrane effective practice and organization of care review group. BMJ 317, 465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465

Bjorkhem-Bergman, L., Andersen-Karlsson, E., Laing, R., Diogene, E., Melien, O., Jirlow, M., et al. (2013). Interface management of pharmacotherapy. Joint hospital and primary care drug recommendations. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69(Suppl. 1), 73–78. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1497-5

Brusamento, S., Legido-Quigley, H., Panteli, D., Turk, E., Knai, C., Saliba, V., et al. (2012). Assessing the effectiveness of strategies to implement clinical guidelines for the management of chronic diseases at primary care level in EU Member States: a systematic review. Health Policy 107, 168–183. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.08.005

Chang, J., Ye, D., Lv, B., Jiang, M., Zhu, S., Yan, K., et al. (2017). Sale of antibiotics without a prescription at community pharmacies in urban China: a multicentre cross-sectional survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 1235–1242. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw519

Collignon, P., Athukorala, P. C., Senanayake, S., and Khan, F. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: the major contribution of poor governance and corruption to this growing problem. PLoS ONE 10:e0116746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116746

Costelloe, C., Metcalfe, C., Lovering, A., Mant, D., and Hay, A. D. (2010). Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 340:c2096. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2096

Damjanović, A. Š. A., Bajraktarević, A., and BoŽović, T. (2013). The Guideline for Counselling Patients in the Pharmacy. Banja Luka: Pharmaceutical Association of the Republic of Srpska.

Dancer, S. J. (2001). The problem with cephalosporins. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 463–478. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.4.463

de Bie, S., Kaguelidou, F., Verhamme, K. M., De Ridder, M., Picelli, G., Straus, S. M., et al. (2016). Using prescription patterns in primary care to derive new quality indicators for childhood community antibiotic prescribing. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 35, 1317–1323. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001324

Desrosiers, M., Evans, G. A., Keith, P. K., Wright, E. D., Kaplan, A., Bouchard, J., et al. (2011). Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 40 (Suppl. 2), S99–S193. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-2

Dyar, O. J., Beovic, B., Vlahović-Palcevski, V., Verheij, T., and Pulcini, C. (2016). How can we improve antibiotic prescribing in primary care? Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 14, 403–413. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2016.1151353

EC (2002). EC Council Recommendation (EC) 2002/77 of 15 November 2001 on the Prudent Use of Antimicrobial Agents in Human Medicine 2002 OJ L34/13. Available online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=URISERV:c11569&from=EN

ECDC (2016). EARS-Net Surveillance Data. Summary of the Latest Data on Antibiotic Resistance in the European Union. Available online at: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/summary-latest-data-antibiotic-resistance-eu-2016

ECDC (2018). Quality Indicators for Antibiotic Consumption in the Community in Europe. Available online at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/antimicrobial-resistance-and-consumption/antimicrobial-consumption/esac-net-database/Pages/quality-indicators-primary-care.aspx

Eriksen, J., Gustafsson, L. L., Ateva, K., Bastholm-Rahmner, P., Ovesjö, M. L., Jirlow, M., et al. (2017). High adherence to the 'Wise List' treatment recommendations in Stockholm: a 15-year retrospective review of a multifaceted approach promoting rational use of medicines. BMJ Open 7:e014345. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014345

Eslami, N., Eshraghi, A., Vaseghi, G., Mehdizadeh, M., Masjedi, M., and Mehrpooya, M. (2016). Pharmacists' knowledge and attitudes towards upper respiratory infections (URI) in Iran: a cross sectional study. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 11, 342–345. doi: 10.2174/1574887111666160908170618

Fitchett, J. R., and Atun, R. (2016). Antimicrobial resistance: opportunity for Europe to establish global leadership. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 388–389. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00410-7

Fitzgerald, A., Lethaby,. A Cikalo, M., Glanville, J., and Wood, H. (2014). Review of Systematic Reviews Exploring the Implementation/Uptake of Guidelines. Yorh Health Economics Consortium. Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph56/evidence/evidence-review-2-431762366

Francke, A. L., Smit, M. C., de Veer, A. J., and Mistiaen, P. (2008). Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 8:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-38

Fürst, J., CiŽman, M., Mrak, J., Kos, D., Campbell, S., Coenen, S., et al. (2015). The influence of a sustained multifaceted approach to improve antibiotic prescribing in Slovenia during the past decade: findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 279–289. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.990381

Gandra, S., Barter, D. M., and Laxminarayan, R. (2014). Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 973–980. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12798

Godman, B., Bishop, I., Finlayson, A. E., Campbell, S., Kwon, H. Y., and Bennie, M. (2013). Reforms and initiatives in Scotland in recent years to encourage the prescribing of generic drugs, their influence and implications for other countries. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 13, 469–482. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.820956

Godman, B., Fadare, J., Kibuule, D., Irawati, L., Mubita, M., Ogunleye, O., et al. (2017). “Initiatives across countries to reduce antibiotic utilization and resistance patterns; impact and implications,” in Drug Resistance in Bacteria, Fungi, Malaria, and Cancer, eds G. Arora, A. Sajid, and V. C. Kalia (Cham: Springer Nature), 539–576.

Godman, B., Shrank, W., Andersen, M., Berg, C., Bishop, I., Burkhardt, T., et al. (2010). Comparing policies to enhance prescribing efficiency in Europe through increasing generic utilization: changes seen and global implications. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 10, 707–722. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.72

Godman, B., Wettermark, B., Hoffmann, M., Andersson, K., Haycox, A., and Gustafsson, L. L. (2009). Multifaceted national and regional drug reforms and initiatives in ambulatory care in Sweden: global relevance. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 9, 65–83. doi: 10.1586/14737167.9.1.65

Godman, B., Wettermark, B., van Woerkom, M., Fraeyman, J., Alvarez-Madrazo, S., Berg, C., et al. (2014). Multiple policies to enhance prescribing efficiency for established medicines in Europe with a particular focus on demand-side measures: findings and future implications. Front. Pharmacol. 5:106. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00106

GCG prescribing (2017). Greater Glasgow and Clyde Prescribing, Co-Amoxiclav. Available online at: http://www.ggcprescribing.org.uk/formulary/infections/antibacterial-drugs/

Gustafsson, L. L., Wettermark, B., Godman, B., Andersén-Karlsson, E., Bergman, U., Hasselström, J., et al. (2011). The 'wise list'- a comprehensive concept to select, communicate and achieve adherence to recommendations of essential drugs in ambulatory care in Stockholm. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 108, 224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00682.x

Hassali, M. A., Kamil, T. K., Md Yusof, F. A., Alrasheedy, A. A., Yusoff, Z. M., Saleem, F., et al. (2015). General practitioners' knowledge, attitude and prescribing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections in Selangor, Malaysia: findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 511–520. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1012497

Hoxha, I., Malaj, A., Kraja, B., Bino, S., Oluka, M., Marković-Peković, V., et al. (2018). Are pharmacists' good knowledge and awareness on antibiotics taken for granted? The situation in Albania and future implications across countries. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.01.019

Hoxha, I., Malaj, A., Tako, R., and Malaj, L. (2015). Survey on how antibiotics are dispensed in community pharmacies in Albania. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 7, 449–450.

Huttner, B., Goossens, H., Verheij, T., and Harbarth, S. (2010). Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10, 17–31. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70305-6

Jakovljevic, M. B., Djordjevic, N., Jurisevic, M., and Jankovic, S. (2015). Evolution of the Serbian pharmaceutical market alongside socioeconomic transition. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 15, 521–530. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1003044

Jakovljevic, M., Vukovic, M., Chen Ching, C., Antunovic, M., Simic Dragojevic, V., Radovanovic Velickovic, R., et al. (2016a). Do health reforms impact cost consciousness of health care professionals? Results from a nation-wide survey in the balkans. Balkan Med. J. 33, 8–17. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15869

Jakovljevic, M., Lazarevic, M., Milovanovic, O., and Kanjevac, T. (2016b). The new and old Europe: east-west split in pharmaceutical spending. Front. Pharmacol. 7:18. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00018

Jakovljevic, M., and Souliotis, K. (2016). Pharmaceutical Expenditure Changes in Serbia and Greece During the Global Economic Recession SEEJPH, 1–17. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/mail/Downloads/document.pdf

Jinks, T., Lee, N., Sharland, M., Rex, J., Gertler, N., Diver, M., et al. (2016). A time for action: antimicrobial resistance needs global response. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 558–558A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.181743

Jorgji, K., Bebeci, E., Apostoli, P., and Apostoli, A. (2014). Evaluation of use of antibiotics without prescription among young adults in Albania case study: Tirana and Fier District. Hippokratia 18, 217–220.

Kalaba, M., Bajcetic, M., Sipetic, T., Godman, B., Coenen, S., and Goossens, H. (2011). “High rate of self purchasing of oral antibiotics in Serbia: implications for future policies,” in PPRI Conference, 2011 (Vienna). Available online at: http://whocc.goeg.at/Downloads/Conference2011/PraesentationenPPRIKonferenz/general_PPRI%20conference%202011%20Abstract%20book.pdf

Kalaba, M., Godman, B., Vuksanovic, A., Bennie, M., and Malmström, R. E. (2012). Possible ways to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency: republic of Serbia as a case history? J. Comp. Eff. Res. 1, 539–549. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.62

Kibuule, D., Kagoya, H. R., and Godman, B. (2016). Antibiotic use in acute respiratory infections in under-fives in Uganda: findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 14, 863–872. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2016.1206468

Kostić, M., Djakovic, L., Šujić, R., Godman, B., and Jankovic, S. M. (2017). Inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn s disease and Ulcerative Colitis): cost of treatment in Serbia and the implications. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 15, 85–93. doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0272-z

Laxminarayan, R., Matsoso, P., Pant, S., Brower, C., Røttingen, J. A., Klugman, K., et al. (2016). Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 387, 168–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2

Llor, C., and Bjerrum, L. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 5, 229–241. doi: 10.1177/2042098614554919

Malo, S., Bjerrum, L., Feja, C., Lallana, M. J., Abad, J. M., and Rabanaque-Hernández, M. J. (2014). The quality of outpatient antimicrobial prescribing: a comparison between two areas of northern and southern Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1619-0

Marković-Peković, V., and Grubiša, N. (2012). Self-medication with antibiotics in the Republic of Srpska community pharmacies: pharmacy staff behavior. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 21, 1130–1133. doi: 10.1002/pds.3218

Marković-Peković, V., Grubiša, N., Burger, J., Bojanic, L., and Godman, B. (2017). Initiatives to reduce nonprescription sales and dispensing of antibiotics: findings and implications. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 6, 120–125. doi: 10.4103/jrpp.JRPP_17_12

Markovic-Pekovic, V., Skrbić, R., Godman, B., and Gustafsson, L. L. (2012). Ongoing initiatives in the Republic of Srpska to enhance prescribing efficiency: influence and future directions. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 12, 661–671. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.48

Marković-Peković, V., Škrbić, R., Petrović, A., Vlahović-Palcevski, V., Mrak, J., Bennie, M., et al. (2016). Polypharmacy among the elderly in the Republic of Srpska: extent and implications for the future. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 16, 609–618. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1115347

Markovic-Pekovic, V., Stoisavljevic-Satara, S., and Skrbic, R. (2009). Utilisation of cardiovascular medicines in Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 5 years study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 18, 320–326. doi: 10.1002/pds.1704

Martikainen, J. E., Saastamoinen, L. K., Korhonen, M. J., Enlund, H., and Helin-Salmivaara, A. (2010). Impact of restricted reimbursement on the use of statins in Finland: a register-based study. Med. Care 48, 761–766. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e41bcb

Md Rezal, R. S., Hassali, M. A., Alrasheedy, A. A., Saleem, F., Md Yusof, F. A., and Godman, B. (2015). Physicians' knowledge, perceptions and behaviour towards antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 665–680. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1025057

MoHSW (2008). Pharmacy Practice Law [in Serbian]. The Republic of Srpska Official Gazzette. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, 119.

MoHSW (2009). Law on Health Care [in Serbian]. The Republic of Srpska Official Gazzette. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. No 106.

MoHSW (2010). Law on Protection of Population from Infectious Diseases [in Serbian]. The Republic of Srpska Official Gazzette. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, No 14.

MoHSW (1999). Law on Health Insurance [in Serbian]. The Republic of Srpska Official Gazzette. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare 1999, No 18.

Moon, J. C., Godman, B., Petzold, M., Alvarez-Madrazo, S., Bennett, K., Bishop, I., et al. (2014). Different initiatives across Europe to enhance losartan utilization post generics: impact and implications. Front. Pharmacol. 5:219. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00219

Mukokinya, M. M., Opanga, S., Oluka, M., and Godman, B. (2018). Dispensing of antimicrobials in Kenya; a cross sectional pilot study and its implications. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. [Epub ahead of print].

O'Neill, J. (2015). Securing New Drugs for Future Generations: The Pipeline of Antibiotics. The Review of Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online at: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/SECURING%20NEW%20DRUGS%20FOR%20FUTURE%20GENERATIONS%20FINAL%20WEB_0.pdf

Oxford, J., and Kozlov, R. (2013). Antibiotic resistance–a call to arms for primary healthcare providers. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 180, 1–3. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12334

PABH (2008). Law on Medicines and Medical Devices [in Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian]. Bosnia and Herzegovina Official Gazzette. Parliamentary assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina, No 58.

Pejcic, A. V., and Jakovljevic, M. (2017). Pharmaceutical expenditure dynamics in the Balkan countries. J. Med. Econ. 20, 1013–1017. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1333514

Petrusic, T., and Jakovljevic, M. (2015). Budget impact of publicly reimbursed prescription medicines in the republic of Srpska. Front. Public Health 3:213. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00213

Putrik, P., Ramiro, S., Kvien, T. K., Sokka, T., Pavlova, M., Uhlig, T., et al. (2014). Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 198–206. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202603

Rezal, R. S., Hassali, M. A., Alrasheedy, A. A., Saleem, F., Yusof, F. A., Kamal, M., et al. (2015). Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections: a prescription-review of primary care practice in Kedah, Malaysia, and the implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 1547–1556. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1085303

Sakshaug, S., Furu, K., Karlstad Ø, O., Rønning, M., and Skurtveit, S. (2007). Switching statins in Norway after new reimbursement policy: a nationwide prescription study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 476–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02907.x

Saleem, Z., Saeed, H., Ahmad, M., Yousaf, M., Hassan, H. B., Javed, A., et al. (2016). Antibiotic self-prescribing trends, experiences and attitudes in upper respiratory tract infection among pharmacy and non-pharmacy students: a study from Lahore. PLoS ONE 11:e0149929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149929

NHS Scotland. (2014). National Therapeutic Indicators 2014/ 2015. Available online at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/DC20141201nti.pdf

Sermet, C., Andrieu, V., Godman, B., Van Ganse, E., Haycox, A., and Reynier, J. P. (2010). Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France: implications for key stakeholder groups. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 8, 7–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03256162

Shallcross, L. J., Howard, S. J., Fowler, T., and Davies, S. C. (2015). Tackling the threat of antimicrobial resistance: from policy to sustainable action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370:20140082. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0082

Tacconelli, E., Carrara, E., Savoldi, A., Harbarth, S., Mendelson, M., Monnet, D. L., et al. (2018). Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3

Taylor, J., H. M., Yerushalmi, E., Smith, R., Bellasio, J., Vardavas, R., et al. (2014). Estimating the Economic Costs of Antimicrobial Resistance: Model and Results. Available online at: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR900/RR911/RAND_RR911.pdf

van Dijk, L., de Jong, J. D., Westert, G. P., and de Bakker, D. H. (2011). Variation in formulary adherence in general practice over time (2003-2007). Fam. Pract. 28, 624–631. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr043

Versporten, A., Bolokhovets, G., Ghazaryan, L., Abilova, V., Pyshnik, G., Spasojevic, T., et al. (2014). Antibiotic use in eastern Europe: a cross-national database study in coordination with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 381–387. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70071-4

Voncina, L., Strizrep, T., Godman, B., Bennie, M., Bishop, I., Campbell, S., et al. (2011). Influence of demand-side measures to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Europe: implications for the future. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 11, 469–479. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.42

Wettermark, B., Godman, B., Neovius, M., Hedberg, N., Mellgren, T. O., and Kahan, T. (2010). Initial effects of a reimbursement restriction to improve the cost-effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment. Health Policy 94, 221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.09.014

Wettermark, B., Pehrsson, A., Juhasz-Haverinen, M., Veg, A., Edlert, M., Törnwall-Bergendahl, G., et al (2009). Financial incentives linked to self-assessment of prescribing patterns: a new approach for quality improvement of drug prescribing in primary care. Qual. Prim. Care 17, 179–189.

WHO (2001). Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. Geneva: WHO. Available online at: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/WHO_Global_Strategy_English.pdf

WHO (2011). European Strategic Action Plan on Antibiotic Resistance. Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/147734/wd14E_AntibioticResistance_111380.pdf

WHO (2015). Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online at: http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/

WHO (2017). WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index. Available online at: https://www.whocc.no/

WHO (2018). Antimicrobial Resistance. Fact Sheet. 2018. Available online at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/

WHO EUROPE (2017). Antimicrobial Medicines Consumption (AMC) Network. Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/337984/51020-WHO-AMC-report-web.pdf?ua=1

Keywords: antibiotic utilization, antibiotic resistance, cross national comparative study, initiatives, Republic of Srpska, quality indicators

Citation: Bojanić L, Marković -Peković V, Škrbić R, Stojaković N, Ðermanović M, Bojanić J, Fürst J, Kurdi AB and Godman B (2018) Recent Initiatives in the Republic of Srpska to Enhance Appropriate Use of Antibiotics in Ambulatory Care; Their Influence and Implications. Front. Pharmacol. 9:442. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00442

Received: 07 March 2018; Accepted: 16 April 2018;

Published: 29 May 2018.

Edited by:

Dominique J. Dubois, Free University of Brussels, BelgiumReviewed by:

Mihajlo Jakovljevic, University of Kragujevac, SerbiaRobert L. Lins, Independent Researcher, Belgium

Copyright © 2018 Bojanić, Marković-Peković, Škrbić, Stojaković, Ðermanović, Bojanić, Fürst, Kurdi and Godman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brian Godman, YnJpYW4uZ29kbWFuQGtpLnNl

Ljubica Bojanić

Ljubica Bojanić Vanda Marković-Peković3,4

Vanda Marković-Peković3,4 Jurij Fürst

Jurij Fürst Amanj B. Kurdi

Amanj B. Kurdi Brian Godman

Brian Godman