- 1College of Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 2Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 3Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Background: High parent education is protective against youth health risk behaviors such as tobacco use. According to the Minorities' Diminished Returns theory, however, higher parent education seems to exert less protection for the ethnic minority relative to the majority groups.

Objectives: To explore ethnic differences in the effects of parent education on the transition to cigarette smoking in a national sample of American never-smoker adolescents.

Methods: This longitudinal study used data of waves 1 and 4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH 2013–2018). This analysis included 5,021 American youth who were never smokers at baseline (2013) and were followed for 4 years. Transition to cigarette smoking was the dependent variable. Parent education was the independent variable. Youth age, youth gender, and family structure were the covariates. Ethnicity was the moderating variable.

Results: From the 5,021 American youth who were never smokers at baseline (2013), 89.4% continued as never smokers, and 10.6% became ever-smokers. Overall, 4.0% were current smokers at wave 4. Overall, a higher parent education was associated with lower odds of transitioning to ever and current cigarette smoker at the end of the 4th year. Parent education, however, showed significant interaction with Latino ethnicity on both outcomes suggesting smaller protective effects of high parent education against transitioning to tobacco use for Latino than for non-Latino youth.

Conclusions: In the U.S., ethnicity alters the magnitude of the protective effect of parent education against youth transition to tobacco use. While high parent education is protective against transitioning to become a cigarette smoking overall, non-Latinos (a socially privileged group) gain more and Latino youth (a socially marginalized group) gain least from such a resource. In addition to addressing the SES gap, policymakers should identify and address mechanisms by which ethnic minority youth remain at risk of tobacco use, even when they are from highly educated families.

Background

Tobacco is still among the leading preventable causes of disease in the US (1–3). About 480,000 Americans die from tobacco-related illnesses annually. Besides, more than 16 million Americans are impacted by diseases caused by tobacco (4). These tobacco-related illnesses cost the U.S. more than $300 billion each year. Unfortunately, there is an unequal health burden from tobacco use in the U.S (4). Despite the progress in reducing overall morbidity and mortality attributed to smoking, tobacco use has shifted from a mainstream public health issue to a concentrated public health problem predominantly impacting marginalized populations defined by socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity (5).

In line with the Minorities' Diminished Returns (MDRs), (6, 7) refer to “less than expected” health effects of family socioeconomic status, particularly parent education in ethnic minority groups compared to ethnic majority youth (8–11). These patterns are persistent across SES resources and outcomes 12. They suggest that (a) not all ethnic disparities are caused by SES gaps but also by differential health gains from social and economic resources for ethnic groups compared to Whites; (b) relatively speaking, ethnic gaps in a wide range of outcomes may increase rather than decrease as SES levels increase; and (c) we should address ethnic disparities across all SES spectrum, rather than merely focusing on disparities in the low SES ethnic minorities (6, 7). The result of this line of work redirects the attention from focusing on health disparities in low SES (12) to middle-class ethnic minorities (13–16), which is a growing section of the U.S. demography. This view is also similar to what Navarro has proposed as ethnicity “and” SES rather than ethnicity “or” SES as the primary contributor to health disparities (17–19). Finally, it emphasizes the lack of comparability of SES across ethnic groups (20).

The MDRs have been applied to explain ethnic differences in tobacco (21, 22) and alcohol (23) use in adolescents (24) adults (21, 22, 25). Among adults, a study using a national random sample of Whites and African Americans documented a larger effect of educational attainment on alcohol use among Whites than among African Americans (23). In a study using the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), educational attainment showed a smaller protective effect on smoking among African American adults than among White adults (21). In the HINTS data that are also nationally representative of adults, education showed a larger effect on reducing tobacco use of Whites than African Americans (21, 26). In another study of adults that used a representative sample of Los Angeles residents, employment had a larger protective effect against smoking for non-Latino than for Latino adults 23. In the only published study on MDRs of parent education in adolescents, using cross-sectional data of the baseline of Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH 2013) showing parent education better reduces tobacco dependence in Whites than African Americans and Latinos (24). In another cross-sectional study that used the PATH-Adults data, educational attainment better reduced hookah smoking for Whites and non-Latinos than African Americans and Latinos (27). In a PATH-Adults study, high education was associated with a larger increase in tobacco harm knowledge in Whites and non-Latinos than African Americans and Latinos (28). In the PATH-Adults study, education better reduced exposure to tobacco ads for non-Latino Whites than African Americans and Latinos (29). In another study using the PATH-Adults study, education better reduced the risk of smoking in non-Latino Whites than in Chinese Americans (30). In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) study, educational attainment showed larger protective effects against second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke in home (31) and workplace (32), for Whites than for African Americans. None of these studies, however, have used longitudinal data.

Extensive research has suggested that MDRs also apply to youth. MDRs for youth are not specific to tobacco use, as they hold for a wide range of outcomes (8–11). Parental education is associated with lower obesity (11, 33), chronic disease (24, 34–36), aggression (24), tobacco use (24), and impulsivity (9) for Whites than for African Americans. Similarly, parental education better boosts school bonding (37) and school performance (24, 38–40) of White than African American youth. Parental education generates less tangible health outcomes for African American youth than for non-Latino White youth (9–11, 24, 40–42). However, for at least two reasons, there is a need to conduct more studies on the contribution of MDRs to tobacco health disparities in Latino youth. First, most of the MDR literature is on African American rather than Latino youth (9–11, 24, 40–42). Very few studies have ever shown such patterns for Latino youth. Second, almost all of the existing literature on MDRs is using cross-sectional data, with almost no studies testing ethnic variation in the protective effects of education on future transition in tobacco use. Thus, there is a need to extend this literature to longitudinal studies that compare the protective effects of parent education for Latino and non-Latino adolescents over time.

For several reasons, ethnic minority youth, particularly Latino youth, are a high-risk group smoking in the US (43). Latino white (vs. non-Latino white) youth may perceive tobacco products as less dangerous (44). Latino white youth are more likely to experiment with tobacco products than non-Latino youth are (45–48). Latino youth may have lower perceived harm of e-cigarettes relative to non-Latino white youth, which may increase their risk of initiation, experimentation, and continuation (49). Non-Latino white youth are experiencing a faster decline in smoking rates than ethnic minorities are, including Latino youth (50, 51). Latinos have reduced access to smoking cessation treatments. Latinos are also less likely to receive advice to quit from their healthcare professionals. On top of discrimination and bias, this is in part because Latinos have less healthcare access and lower health insurance coverage. Finally, Latinos are also more likely to relapse following smoking cessation attempts relative to non-Latino whites (43). Latino youth are at a higher risk of transitioning to more stable use patterns than White youth. This is shown as a potential increased risk of transition from experimental to regular use in Latino youth. Latinos with cigarette smoking may be less likely to have successful cessation. These observations are suggestive of a telescoping effect of tobacco use in Latino youth and other ethnic minorities. As a result of such vulnerability, despite a later smoking onset, Latino youth are more likely to show undesired tobacco outcomes and tobacco-related illnesses and chronic diseases (43, 45–49).

Aim

Using the longitudinal data of PATH that followed a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents for four years from 2013 to 2018, we performed this study to explore whether adolescents' ethnicity alters the effects of parent education on change in tobacco use of non-smoker adolescents over time. We hypothesized that the protective effect of parent education against transitioning to tobacco use would be smaller for Latino than in Non-Latino White youth.

Methods

Design and Settings

This longitudinal study is a secondary analysis of waves 1 and 4 of the PATH–Adolescents. PATH is the main longitudinal study of tobacco use in the U.S. Wave 1 and wave 4 of the data were collected in 2013–2014 and 2017–2018, respectively.

Sample and Sampling

The PATH study's adolescent sample in Wave 1 was the civilian, non-institutionalized, U.S. population 12–17 years old in the U.S. The current analysis was limited to the 5,021 adolescents who were never-smokers at baseline and were followed for 4 years and had valid data on their smoking status at wave 4. The PATH study used a four-stage stratified area probability sample design to recruit participants. Using stratified sampling, at the 1st stage, 156 primary sampling units (PSUs) were selected. The PATH geographical PSUs were composed of single or a group of counties. The 2nd stage was formed from sampled smaller geographical segments in each PSU. The 3rd stage sampled residential addresses. The 4th stage was the selection of one adolescent and adult participant within households. Participants completed a questionnaire using an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview system.

Study Variables

The study variables included adolescent age, gender, ethnicity, parent education, parental marital status, all measured at wave 1, and tobacco use at wave 4.

Dependent Variables

Ever cigarette smoking

The primary outcome was transitioning to ever cigarette smoking. Ever use was measured using the following question: “Did you ever try cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs?”(1=Yes, 0=No).

Current cigarette smoking

The secondary outcome was transitioning to current smoking. Current cigarette smoking at wave four was measured by a series of items, including asking participants whether they smoked in their life, in the past 30 days, and how much they smoked. Those who said they had smoked were asked about the number of days they smoked during the past 30 days question. So, we could identify individuals who were current smokers (ever smoker + smoked over the past 30 days). Responses on this item were 0 and 1.

Independent Variable

Parent education

Parent education was measured as a categorical variable with three levels: (1) less than high school graduation, (2) high school graduation, and (3) college graduation.

Moderator Variables

Ethnicity

Adolescent ethnicity was used as moderator variable and was operationalized as dichotomous variable: African American vs. White and Latino vs. Non-Latino.

Demographic Confounders

Age, gender, and family structure were the covariates. Age was measured as a dichotomous variable: (1) 12–15 years old and (2) 16–17 years old. Gender was a dichotomous variable. Family structure was a dichotomous variable; 1= married, 0 = otherwise.

Data Analytical Plan

As we were interested in the longitudinal association between parent education and subsequent tobacco use outcomes at wave 4, our predictors were all measured at wave 1 (baseline), and the outcome was measured at wave 4. Since the PATH study uses a complex multistage sampling design and provides survey weights to makes results generalizable to the U.S. population, we applied the weights and used Taylor series linearization for variance estimation. We first explored the separate and joint distribution of our variables. We ruled out collinearity between our variables (ethnicity, educational attainment, and parental marital status). For univariate analysis, we used a frequency table. Next, we used multivariable logistic regression analysis with binary tobacco use measures as outcomes. We ran two models in the pooled samples for each outcome. Model 1 had no interaction terms. Model 2 always had two interaction terms between ethnicity and parent education. For the main effects of parental education on smoking outcomes, ORs <1.00 are protective. For race by education interaction terms, OR <1.00 is indicative of larger protection for African Americans or Latinos than Whites and non-Latinos. We used SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) to analyze the data.

Ethics

All adolescent participants provided written assent. When they became adults, they provided consent. All the parents or guardians also provided permission and consent to be interviewed. The study protocol was revived and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. We, however, used the PATH public data set, which is fully de-identified. As a result, the current analysis was non-human research and was exempt from an IRB review.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

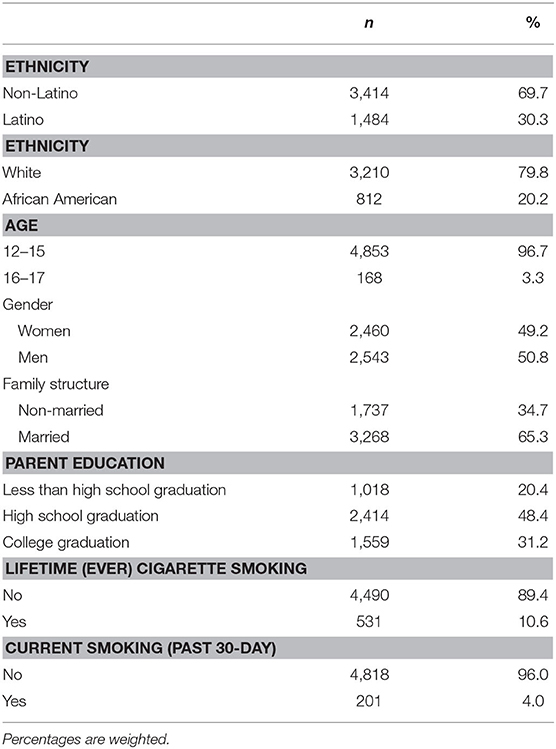

This study included 5,021 American youth who were never smokers at baseline (2013). From this number, 4490 (89.4%) continued as never smoker, and 531(10.6%) became ever-smoker. Table 1 shows the descriptive data in the total sample.

Multivariable Models

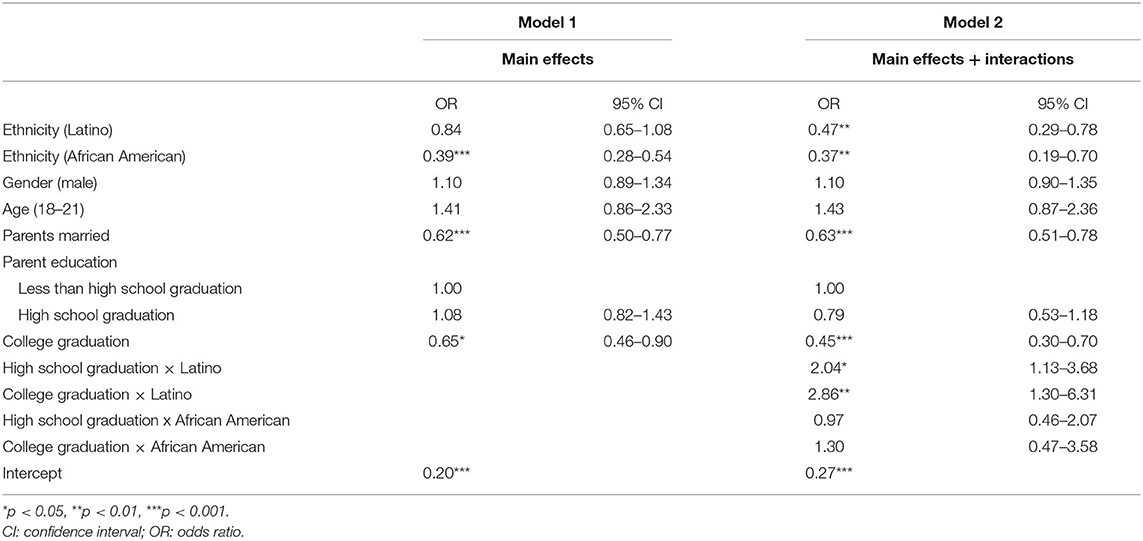

Table 2 shows the results of two nested logistic regression models with parent education as the independent variable and tobacco use outcomes as the dependent variable. Both models were estimated in the pooled sample. While Model 1 only included the main effects of parent education, ethnicity, and covariates, Model 2 also included interactions between ethnicity and parent education.

Based on Model 1, high parent education was associated with lower odds of transition to ever smoker status. Model 2 showed interactions between parent education and Latino ethnicity on the transition to ever smoker status, which suggests that a higher parent education has a smaller protective effect on the transition to ever smoker status for Latino than non-Latino youth (Table 2).

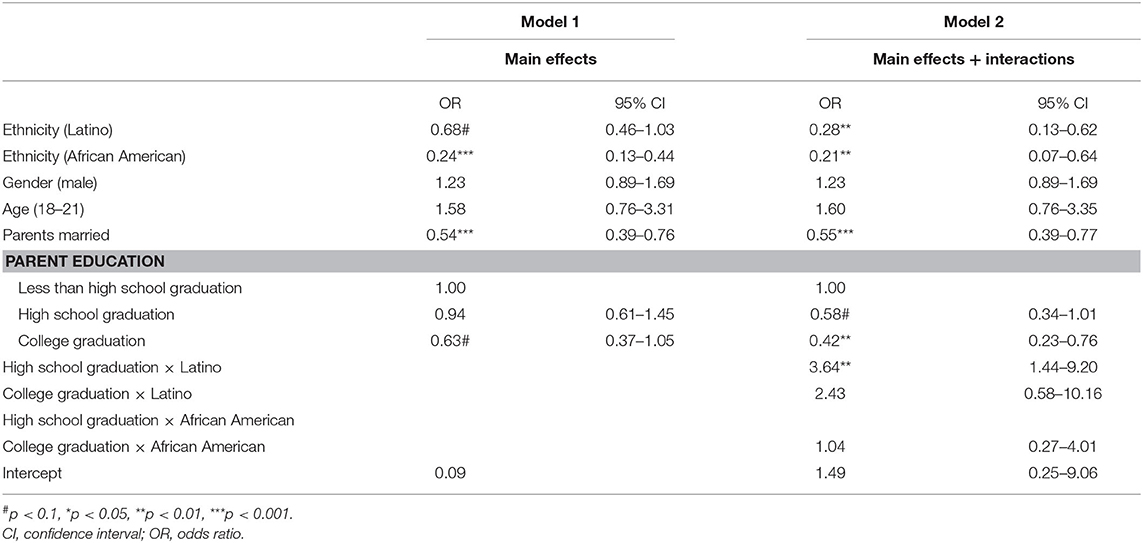

Table 3 shows the results of two nested logistic regression models with parent education as the independent variable and transition to current cigarette smoker as the dependent variables. Both models were estimated in the pooled sample. While Model 1 only included the main effects of parent education, ethnicity, and covariates, Model 2 also included four interaction terms between Latino and African American ethnicity and two levels of parent education.

Based on Model 1, high parent education was associated with lower odds of transition to a current cigarette smoker. Model 2 showed interactions between parent education and Latino ethnicity on the transition to a current cigarette smoker, which suggests a higher parent education has a smaller protective effect on youth tobacco use outcomes for Latino than non-Latino youth (Table 2).

Discussion

The current study produced two findings. First, in the overall sample, high parent education was protective against youth transition to tobacco use. Second, the protective effect of high parental education against the eventual transition to cigarette smoking was diminished for Latino than for non-Latino youth. Thus, while parent education protects youth against transitioning to tobacco use, this protection is seemingly unequal, with ethnic minorities (i.e., Latino) gaining weaker protection than the majority (non-Latino). This is another example of how ethnicity, a marginalizing social identity, reduces the health return of a socioeconomic resource for a minority group.

The overall finding on protective effects of parental education against the transition of youth to tobacco outcomes is in line with what we know about social patterning of health, social determinants of health, fundamental cause theory, and social gradient in health. Extensive research in the U.S., Europe, and other parts of the world has established a protective effect of parental education as one of the main protective resources against the risk behaviors of youth. High parental education is not only protective against tobacco use it also protects youth against depression, anxiety, alcohol use, violence, and poor educational outcomes.

Our finding in Latino youth is in line with our previous work showing that high SES (e.g., educational attainment, income, marital status, and employment) African American youth and adults at a disproportionately high risk of substance use, a level which is not expected given their family SES (21, 23, 25, 52). This finding may also explain why high educated African Americans and Latinos remain at risk of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (53). This might also be because highly educated Latinos and African Americans are exposed to a high level of tobacco advertisements, suggesting that they may be a target of predatory marketing strategies. Finally, it may be because African American and Latino youth report more peers and family members who use substances such as tobacco, and they attend schools that have a higher social-environmental risk that increases the risk of tobacco use.

These patterns are consistent with what we know about the impact of SES on other health outcomes such as substance use (25), anxiety (54), diet (55), exercise (56), depression (57), happiness (58), affect (58), suicide (59), self-rated health (60), obesity (11, 33), chronic disease (36), oral health (42), and mortality (61) are all smaller for African Americans than for non-Latino Whites. This study extends this literature to Latinos.

Besides, multiple analyses (9–11, 36, 37, 62) of 15 years of Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study (FFCWS) data have shown that high parental education and high family income at birth better protect obesity (11), grade point average (39), impulsivity (9), and ADHD (36) at age 15. The universal nature of the diminishing returns of family SES indicators on various health outcomes of non-Whites proposes that MDRs is a new, systematic, and understudied mechanism for transgenerational transmission of health inequalities in the United States. The FFCWS papers (9–11, 36, 37, 62) suggests that by the age of 15, parental education and family income have already generated unequal outcomes in youth (9–11, 36, 37, 62). Other research suggests that some of these inequalities occur before age 15 (33, 35). These findings have major implications for the elimination of health inequalities in the next generations. Interventions should happen across levels and before the age of 15.

At least some of these MDRs may be due to racial and ethnic residential segregation. Racial residential segregation will have a profound effect on the availability of cigarettes. There is a preponderance of advertising and the sale of cigarettes, especially loosies (single cigarettes) (63), in communities of color. Such sale (64) strategies allow for a more affordable cost of tobacco use in Latino and low-income communities who may not afford to purchase a pack of cigarettes (65). Greater education, however, does not mean that ethnic minorities can afford to purchase homes in neighborhoods where cigarettes and advertising are more regulated (13, 66–68).

Tobacco products are frequently advertised and promoted in the Latino communities (69, 70). Tobacco companies have historically tried to appeal to the Latino population through branding, financial contributions, targeted advertising, and other marketing strategies. For example, cigarette brands such as “Rio” and “Dorado” have been heavily advertised and marketed to the Latino community (69). As a result of these advertisements, these brands have appealed to the Latino-American community (69). The tobacco industry has also contributed to fund universities and colleges that support scholarship programs targeting Latinos (69). At the same time, the tobacco industry has funded Latino political organizations, cultural events, and the Latino art community (69).

There is a need to conduct more studies on the role of predatory marketing practices on ethnic and SES disparities in tobacco use. We argue that structural factors such as predatory marketing may generate MDRs on tobacco use of non-White youth. That is, predatory marketing and advertising may impose an additional risk of tobacco use to high SES Latino individuals through reducing the effects of SES. SES is shown to have smaller effects for Latino to bring them out of poor urban areas (68). High SES Latino youth may be exposed to a high density of tobacco retails and advertisements. Introducing more restrictive tobacco marketing regulations may be particularly beneficial to Latino populations. Example policies include banning additional point-of-sale advertisement, flavoring, coupons, and discounts in predominantly ethnic minority areas. However, all these hypotheses need additional research.

Implications

The results may have some policy and public health implications. The results help increase “understanding [of] why people become susceptible to using tobacco products” (71). The results may extend the development of public policies that can be designed and implemented to address tobacco-related disparities such as more restrictive national and local marketing and other policies (72). Fortunately, the literature shows that currently, Americans tend to positively evaluate tobacco control regulations and do not view them as against their autonomy (72).

There is a need for both national and local policies that specifically address MDR-related disparities in tobacco use and related health conditions (7, 9, 11, 21, 25, 42, 52, 54, 73, 74). We need to study the roles of discounts, coupons, flavoring, and the density of tobacco retails in shaping MDR-related disparities in tobacco use (21, 25). Similarly, we need to study the role of tobacco control policies and regulations that may minimize MDR-related tobacco disparities. It is essential to explore how these marketing strategies target low SES Latino communities (21, 23, 25, 52). To undo the ethnic disparities in tobacco use, there is a need to stop predatory tobacco marketing in low-income areas. Minimizing MDR-related inequalities should be regarded as a core element of tobacco prevention strategies in middle-class ethnic minorities.

Limitations

This study had some methodological limitations. The sample size was imbalanced across ethnic groups and tobacco use outcomes. As a result, and to avoid differential statistical power across groups, we did not conduct ethnic-specific models. Income, employment, marital status, and area-level SES factors were not included in this study. Parental smoking data could also be a confounder. Our study did not include any data on parental substance use. Geographic region and household size could also be relevant to both parental education and youth smoking. This study did not measure tobacco control policies that vary based on the geographic location of the participants. Our strengths included large sample size, random sampling, longitudinal design, and results that were generalizable to the U.S. Our longitudinal design allowed us to model the incidence of (transition to) smoking rather than the cross-sectional prevalence of tobacco use. Still, more research is needed on the mechanisms of MDRs of parent education on youth tobacco use.

Conclusion

In the United States, minority youth are at a relative disadvantage compared to White youth in gaining tobacco use prevention benefits from their parent education. While higher parent education helped adolescents have lower tobacco use, this pattern is more pronounced in the most privileged (white) youth compared to Latino youth. As a result, we should expect a higher than expected risk of tobacco use in Latino youth from high SES families. Tobacco-related health disparities by ethnicity may be generated by factors beyond SES families. Research should explore structural factors that contribute to the reduced protective effects of parent education on tobacco use of middle-class Latino youth.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

All adolescent participants provided written assent. When they became adults, they provided consent. All the parents or guardians also provided permission and consent to be interviewed. The study protocol was revived and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. We, however, used the PATH public data set which is fully de-identified. As a result, the current analysis was non-human research and was exempt from an IRB review.

Author Contributions

SA conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, prepared the first draft of the paper, and acquired the funding. MB and CC contributed to the revision and conceptualization of the study. All authors approved the final draft.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under Award Number U54CA229974. SA is also funded by the following NIH awards: 5S21MD000103, 54MD008149, R25 MD007610, 2U54MD007598, and U54 TR001627. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. McCarthy M. Smoking remains leading cause of premature death in US. BMJ. (2014) 348:g396. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g396

2. Samet JM. Tobacco smoking: the leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thorac Surg Clin. (2013) 23:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.01.009

3. Novick LF. Smoking is the leading preventable cause of death and disability in the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2000) 6:4. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200006030-00001

4. CDC. Smoking & Tobacco Use. Fast Facts. (2019). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm (accessed May 5, 2020).

5. Yang T, Jiang S, Barnett R, Oliffe JL, Wu D, Yang X, et al. Who smokes in smoke-free public places in China? findings from a 21 city survey. Health Educ Res. (2016) 31:36–47. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv054

6. Assari S. Health disparities due to diminished return among black americans: public policy solutions. Social Issues Policy Rev. (2018) 12:112–45. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12042

7. Assari S. Unequal gain of equal resources across racial groups. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2017) 7:1–9. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.90

8. Assari S, Boyce S, Bazargan M, Mincy R, Caldwell CH. Unequal protective effects of parental educational attainment on the body mass index of black and white youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193641

9. Assari S, Caldwell CH, Mincy R. Family socioeconomic status at birth and youth impulsivity at age 15; blacks' diminished return. Children. (2018) 5:1–12. doi: 10.3390/children5050058

10. Assari S, Caldwell CH, Mincy RB. Maternal educational attainment at birth promotes future self-rated health of white but not black youth: a 15-year cohort of a national sample. J Clin Med. (2018) 7:1–13. doi: 10.3390/jcm7050093

11. Assari S, Thomas A, Caldwell CH, Mincy RB. Blacks' diminished health return of family structure and socioeconomic status; 15 years of follow-up of a national urban sample of youth. J Urban Health. (2018) 95:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0217-3

12. Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Lachance L, Johnson J, Gaines C, Israel BA. Associations between socioeconomic status and allostatic load: effects of neighborhood poverty and tests of mediating pathways. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:1706–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300412

13. Hudson D, Sacks T, Irani K, Asher A. The price of the ticket: health costs of upward mobility among African Americans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041179

14. Hudson DL, Puterman E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Matthews KA, Adler NE. Race, life course socioeconomic position, racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and self-rated health. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 97:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.031

15. Hudson DL, Bullard KM, Neighbors HW, Geronimus AT, Yang J, Jackson JS. Are benefits conferred with greater socioeconomic position undermined by racial discrimination among African American men? J Mens Health. (2012) 9:127–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.006

16. Hudson DL, Neighbors HW, Geronimus AT, Jackson JS. The relationship between socioeconomic position and depression among a US nationally representative sample of African Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:373–81. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0348-x

17. Navarro V. Race or class or race and class: growing mortality differentials in the United States. Int J Health Serv. (1991) 21:229–35. doi: 10.2190/5WXM-QK9K-PTMQ-T1FG

18. Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet. (1990) 336:1238–40. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92846-A

19. Navarro V. Race or class, or race and class. Int J Health Serv. (1989) 19:311–4. doi: 10.2190/CNUH-67T0-RLBT-FMCA

20. Bell CN, Sacks TK, Thomas Tobin CS, Thorpe RJ Jr. Racial Non-equivalence of Socioeconomic Status and Self-rated Health among African Americans and Whites. SSM Popul Health. (2020) 10:100561. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100561

21. Assari S, Mistry R. Educational attainment and smoking status in a national sample of american adults; evidence for the blacks' diminished return. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040763

22. Shervin A, Ritesh M. Diminished return of employment on ever smoking among hispanic Whites in Los Angeles. Health Equity. (2019) 3:138–44. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0070

23. Assari S, Lankarani MM. Education and alcohol consumption among older Americans; black-white differences. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00067

24. Assari S BM, Caldwell CH. Association between parental educational attainment and youth outcomes and role of race/ethnicity. JAMA Network Open. (2020) 2:1–14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16018

25. Assari S, Farokhnia M, Mistry R. Education attainment and alcohol binge drinking: diminished returns of hispanics in Los Angeles. Behav Sci. (2019) 9:1–11. doi: 10.3390/bs9010009

26. Assari S, Mistry R, Bazargan M. Race, educational attainment, and e-cigarette use. J Med Res Innovation. (2020) 4:e000185. doi: 10.32892/jmri.185

27. Assari SBM, Chalian M. Social determinants of hookah smoking in the United States. J Mental Health Clin Psychol. (2020) 4:21–7. doi: 10.29245/2578-2959/2020/1.1185

28. Assari SBM, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Educational attainment and tobacco harm knowledge among American adults: diminished returns of African Americans and hispanics. Int J Epidemiol Res. (2020) 7:6–11. doi: 10.34172/ijer.2020.02

29. Assari S. Association of educational attainment and race/ethnicity with exposure to tobacco advertisement among us young adults. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e1919393. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19393

30. Assari S. Diminished returns of income against cigarette smoking among Chinese Americans. J Health Econ Develop. (2019) 1:1–8.

31. Assari S, Bazargan M. Second-hand exposure home second-hand smoke exposure at home in the United States; minorities' diminished returns. Int J Travel Med Glob Health. (2019) 7:135–41. doi: 10.15171/ijtmgh.2019.28

32. Assari S, Bazargan M. Unequal effects of educational attainment on workplace exposure to second-hand smoke by race and ethnicity; minorities' diminished returns in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). J Med Res Innov. (2019) 3:e000179. doi: 10.32892/jmri.179

33. Assari S. Family income reduces risk of obesity for white but not black children. Children. (2018) 5:1–13. doi: 10.3390/children5060073

34. Assari S, Bazargan M, Caldwell C. Parental educational attainment and chronic medical conditions among American youth; minorities' diminished returns. Children. (2019) 6:1–12. doi: 10.3390/children6090096

35. Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M. Poverty status and childhood asthma in white and black families: national survey of children's health. Healthcare. (2018) 6:62. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020062

36. Assari S, Caldwell CH. Family income at birth and risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at age 15: racial differences. Children. (2019) 6:1–11. doi: 10.3390/children6010010

37. Assari S. Family socioeconomic position at birth and school bonding at age 15; blacks' diminished returns. Behav Sci. (2019) 9:26. doi: 10.3390/bs9030026

38. Assari S. Parental educational attainment and academic performance of american college students; blacks' diminished returns. J Health Econ Develop. (2019) 1:21–31.

39. Assari S, Caldwell CH. Parental educational attainment differentially boosts school performance of american adolescents: minorities' diminished returns. J Family Reprod Health. (2019) 13:7–13. doi: 10.18502/jfrh.v13i1.1607

40. Assari S. Parental education attainment and educational upward mobility; role of race and gender. Behav Sci. (2018) 8:107. doi: 10.3390/bs8110107

41. Assari S. Parental educational attainment and mental well-being of college students; diminished returns of blacks. Brain Sci. (2018) 8:193. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8110193

42. Assari S, Hani N. Household income and children's unmet dental care need; blacks' diminished return. Dent J. (2018) 6:17. doi: 10.3390/dj6020017

43. Barrington-Trimis JL, Bello MS, Liu F, Leventhal AM, Kong G, Mayer M, et al. Ethnic differences in patterns of cigarette and e-cigarette use over time among adolescents. J Adolescent Health. (2019) 65:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.002

44. Dai H, Hao J. Flavored electronic cigarette use and smoking among youth. Pediatrics. (2016) 138:e20162513. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2513

45. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Leventhal AM, Gauderman WJ, Cruz TB, Gilreath TD, et al. E-cigarettes, cigarettes, and the prevalence of adolescent tobacco use. Pediatrics. (2016) 138:e20153983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3983

46. General USPHSOOTS, Prevention NCFCD, Smoking HPOO. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Government Printing Office. (2012). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00030927.htm (accessed May 5, 2020).

47. Health UDO Services H. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA. (2016) Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30869850/ (accessed May 5, 2020).

48. Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975-2003. Vol 1: National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Services. (2004) Available online at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/monitoring-future-2018-survey-results (accessed May 5, 2020).

49. Hammig B, Daniel-Dobbs P, Blunt-Vinti H. Electronic cigarette initiation among minority youth in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2017) 43:306–10. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1203926

50. Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2015) 64:381. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6438a2

51. Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Homa DM, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. (2016) 65:361–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1

52. Assari S, Mistry R. Educational attainment and smoking status in a national sample of American adults; evidence for the blacks' diminished return. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102084

53. Assari S, Chalian H, Bazargan M. High education level protects European Americans but not African Americans against chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Health Interview Survey. Int J Biomed Eng Clin Sci. (2019) 5:16–23. doi: 10.11648/j.ijbecs.20190502.12

54. Assari S, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Family structure and subsequent anxiety symptoms; minorities' diminished return. Brain Sci. (2018) 8:97. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8060097

55. Assari S, Lankarani MM. Educational attainment promotes fruit and vegetable intake for whites but not blacks. J. (2018) 1:29–41. doi: 10.3390/j1010005

56. Assari S. Educational attainment and exercise frequency in American women; blacks' diminished returns. Women's Health Bulletin. (2019) 6:e87413. doi: 10.5812/whb.87413

57. Assari S. High income protects whites but not african americans against risk of depression. Healthcare. (2018) 6:37. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020037

58. Assari S, Preiser B, Kelly M. Education and income predict future emotional well-being of whites but not blacks: a ten-year cohort. Brain Sci. (2018) 8:122. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8070122

59. Assari S, Schatten HT, Arias SA, Miller IW, Camargo CA, Boudreaux ED. Higher educational attainment is associated with lower risk of a future suicide attempt among non-hispanic whites but not non-hispanic blacks. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2019) 6:1001–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00601-z

60. Assari S, Lapeyrouse LM, Neighbors HW. Income and self-rated mental health: diminished returns for high income black Americans. Behav Sci. (2018) 8:50. doi: 10.3390/bs8050050

61. Assari S. Life expectancy gain due to employment status depends on race, gender, education, and their intersections. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2018) 5:375–86. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0381-x

62. Assari S, Mardani A, Maleki M, Bazargan M. Black-white differences in the association between maternal age at childbirth and income. Women's Health Bull. (2019) 6:36–42. doi: 10.30476/whb.2019.46236

63. Azagba S, Shan L, Manzione LC, Latham K, Rogers C, Qeadan F. Single cigarette purchasers among adult U.S. smokers. Prev Med Rep. (2020) 17:101055. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101055

64. Baker HM, Lee JG, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Single cigarette sales: state differences in FDA advertising and labeling violations, 2014. United States. Nicotine Tob Res. (2015) 18:221–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv053

65. Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Dorantes-Alonso A, Arillo-Santillán E, Michael CK, O'Connor R, et al. Does the availability of single cigarettes promote or inhibit cigarette consumption? perceptions, prevalence and correlates of single cigarette use among adult Mexican smokers. Tob Control. (2009) 18:431–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029132

66. Oliver M, Shapiro T. Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. New York, NY: Routledge (2013). doi: 10.4324/9780203707425

68. Assari S. Parental education better helps white than black families escape poverty: national survey of children's health. Economies. (2018) 6:30. doi: 10.3390/economies6020030

69. Kids TF. Tobacc free kids. (2015). Available online at: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/ (accessed May 5, 2020).

70. CDC. Hispanics/Latinos and Tobacco Use. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/hispanics-latinos/index.htm (accessed May 5, 2020).

71. FaDA Research Priorities,(FDA). (2019). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/research/research-priorities (accessed May 5, 2020).

72. Feliu A, Filippidis FT, Joossens L, Fong GT, Vardavas CI, Baena A, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob Control. (2019) 28:101–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054119

73. Assari S. Blacks' diminished return of education attainment on subjective health; mediating effect of income. Brain Sci. (2018) 8:176. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8090176

Keywords: education, smoking, tobacco use, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, youth

Citation: Assari S, Boyce S, Caldwell CH and Bazargan M (2020) Parent Education and Future Transition to Cigarette Smoking: Latinos' Diminished Returns. Front. Pediatr. 8:457. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00457

Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 30 June 2020;

Published: 19 August 2020.

Edited by:

Mehdi Osooli, Lund University, SwedenReviewed by:

Ryan San Diego, University of Auckland, New ZealandDarrell Lee Hudson, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Copyright © 2020 Assari, Boyce, Caldwell and Bazargan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shervin Assari, YXNzYXJpJiN4MDAwNDA7dW1pY2guZWR1

Shervin Assari

Shervin Assari Shanika Boyce

Shanika Boyce Cleopatra H. Caldwell2

Cleopatra H. Caldwell2 Mohsen Bazargan

Mohsen Bazargan